Quantock Hills

Encyclopedia

The Quantock Hills is a range of hill

s west of Bridgwater

in Somerset

, England

. The Quantock Hills were England’s first Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty

being designated in 1956 and consists of large amounts of heathland, oak woodlands, ancient parklands and agricultural land.

The hills run from the Vale of Taunton Deane

in the south, for about 15 miles (24 km) to the north-west, ending at East Quantoxhead

and West Quantoxhead

on the coast of the Bristol Channel

. They form the western border of Sedgemoor

and the Somerset Levels

. From the top of the hills on a clear day, it is possible to see Glastonbury Tor

and the Mendips

to the east, Wales

as far as the Gower Peninsula

to the north, the Brendon Hills

and Exmoor

to the west, and the Blackdown Hills

to the south. The highest point on the Quantocks is Wills Neck

, at 1261 feet (384 m). Soil types and weather combine to support the hills' plants and animals. In 1970 an area of 6194.5 acres (2,506.8 ha) was designated as a Biological Site of Special Scientific Interest

.

They have been occupied since prehistoric times with Bronze Age

round barrow

s and Iron Age

hill forts. Evidence from Roman

times includes silver

coins discovered in West Bagborough

. In the later Saxon period, King Alfred

led the resistance to Viking

invasion, and Watchet

was plundered by Danes in 987 and 997. The hills were fought over during the English Civil War

and Monmouth Rebellion

but are now a peaceful area popular with walkers, mountain bikers, horse riders and tourists. They explore paths such as the Coleridge Way

used by the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge

, who lived in Nether Stowey

from 1797 to 1799, or visit places of interest such as Quantock Lodge

.

charters in around AD 880 as Cantuctun and two centuries later in the Domesday Book

as Cantoctona and Cantetone. The name means settlement by a rim or circle of hills; Cantuc is Celtic

for a rim or circle, and -ton or -tun is Old English for a settlement. An alternative meaning is ridge of the Welshman, probably referring to a Saxon tribe that fought a battle locally.

The Quantock Hills are largely formed by rocks of the Devonian

The Quantock Hills are largely formed by rocks of the Devonian

period, which consist of sediments originally laid down under a shallow sea and slowly compressed into solid rock. In the higher north-western areas older Early Devonian rocks known as Hangman Grits predominate and can be seen in the exposed rock at West Quantoxhead

quarry, which was worked for road building. Further south there are newer Middle and Late Devonian rocks, known as Ilfracombe beds and Morte Slates. These include sandstone and limestone, which have been quarried near Aisholt. At Great Holwell, south of Aisholt, is the only limestone cave in the Devonian limestone of North Devon

and West Somerset. The lower fringes around the hills are composed of younger New Red Sandstone

rocks of the Triassic

period. These rocks were laid down in a shallow sea and often contain irregular masses or veins of gypsum

, which was mined on the foreshore at Watchet

.

Several areas have outcrops of slates. Younger rocks of the Jurassic

period can be found between St Audries and Kilve

. This area falls within the Blue Anchor to Lilstock

Site of Special Scientific Interest

(SSSI) and is considered to be of international geological importance.

Kilve has the remains of a red-brick retort

built in 1924 after the shale in the cliffs was found to be rich in oil. Along this coast, the cliffs are layered with compressed strata of oil-bearing shale and blue

, yellow and brown Lias

embedded with fossil

s. The Shaline Company was founded in 1924 to exploit these strata but was unable to raise sufficient capital. The company's retort house is thought to be the first structure erected here for the conversion of shale to oil and is all that remains of the anticipated Somerset oil boom.

At Blue Anchor

the coloured alabaster

found in the cliffs gave rise to the name of the colour "Watchet Blue". The village has the only updraught brick kiln

known to have survived in Somerset. It was built around 1830 and was supplied by small vessels carrying limestone to the small landing jetty

. Now used as a garage, the kiln is thought to have operated until the 1870s, when the large-scale production of bricks in Bridgwater

rendered small brickyards uneconomic.

Cockercombe tuff

is a greenish-grey, hard sedimentary rock formed by the compression of volcanic ash and is found almost exclusively in the south-eastern end of the Quantock Hills.

, the Quantock Hills has a temperate climate that is generally wetter and milder than the rest of England

. The mean temperature is approximately 10 °C (50 °F) and shows a season

al and a diurnal

variation, but because of the modifying effect of the sea the range is less than in most other parts of the United Kingdom

(UK). January is the coldest month with mean minimum temperatures between 1 °C (33.8 °F) and 2 °C (35.6 °F). July and August are the warmest months, with mean daily maxima around 21 °C (69.8 °F). December is normally the most cloudy month and June the sunniest. High pressure over the Azores

often brings clear skies to south-west England, particularly in summer.

Cloud

often forms inland especially near hills, and acts to reduce sunshine. The average annual sunshine totals around 1,600 hours. Rainfall tends to be associated with Atlantic

depressions or with convection. In summer, convection caused by solar surface heating sometimes forms shower clouds, and a large proportion of rain falls from showers and thunderstorms at this time of year. Average rainfall is around 31 to 35 in (787.4 to 889 mm). About 8 to 15 days of snowfall is typical. From November to March, mean wind speeds are highest; winds are lightest from June to August. The predominant wind direction is from the south-west.

(SSSI). This a conservation designation

denoting a protected area

in the United Kingdom

, selected by Natural England

, for areas with particular landscape and ecological characteristics. It provides some protection from development, from other damage, and (since 2000) also from neglect, under the Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000

.

The streams and open water such as Hawkridge Reservoir

and Ashford Reservoir

on Cannington Brook

also provide habitats for a range of species.

The hilltops are covered in heathland of gorse, heather, bracken and thorn with plantations of conifer. The western side of the Quantocks are steep scarp

The hilltops are covered in heathland of gorse, heather, bracken and thorn with plantations of conifer. The western side of the Quantocks are steep scarp

slopes of pasture, woods and parkland. Deep stream-cut combes

to the north-east contain extensive oak-woods with small flower-rich bogs above them. The areas where there is limited drainage are dominated by Heather

(Calluna vulgaris), with significant populations of Cross-leaved Heath

(Erica tetralix), Purple Moor-grass (Molinia caerulea), Bilberry

(Vaccinium myrtillus) and Wavy Hair-grass

(Deschampsia flexuosa). Drier areas are covered with Bell Heather

(Erica cinerea), Western Gorse (Ulex gallii) and Bristle Bent

(Agrostis curtisii), while Bracken

(Pteridium aquilinum) is common on well-drained deeper soils. The springs and streams provide a specialist environment that supports Bog pimpernel

(Anagallis tenella). The woodland is generally Birch/Sessile Oak woodland, Valley Alder woodland and Ash/Wych Elm woodland, which support a rich lichen

flora. Alfoxton Wood is one of only three British locations where the lichen Tomasellia lectea is present.

for a rich fauna. Amphibian

s such as the Palmate Newt

(Triturus helveticus), Common Frog

(Rana

temporaris), and Common toad

(Bufo bufo) are represented in the damper environments. Reptiles

present include Adder (Vipera berus

), Grass Snake

(Natrix natrix), Slow Worm

(Angula fragilis) and Common Lizard

(Lacerta vivipara). Many bird species breed on the Quantocks, including the Grasshopper Warbler

(Locustella naevia), Nightjar

(Caprimulgus europaeus), Raven

(Corvus corax) and the European Pied Flycatcher

(Ficedula hypoleuca). The Quantocks are also an important site for Red deer

(Cervus elaphus). Invertebrates of note include the Silver-washed Fritillary

butterfly (Argynnis paphia), and three nationally rare dead-wood beetles: Thymalus limbatus, Orchesia undulata and Rhinosimus ruficollis.

flints at North Petherton

and Broomfield

and many Bronze Age

round barrow

s (marked on maps as tumulus

, plural tumuli), such as Thorncombe Barrow above Bicknoller

. Several ancient stones can be seen, such as the Triscombe Stone and the Long Stone above Holford

. Many of the tracks along ridges of the Quantocks probably originated as ancient ridgeway

s. A Bronze Age hill fort

, Norton Camp

, was built to the south at Norton Fitzwarren

, close to the centre of bronze making in Taunton

.

Iron Age

Iron Age

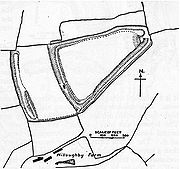

sites in the Quantocks include major hill forts at Dowsborough

and Ruborough, as well as several smaller earthwork enclosures, such as Trendle Ring

and Plainsfield Camp

. Ruborough near Broomfield

is on an easterly spur from the main Quantock ridge, with steep natural slopes to the north and south east. The fort is triangular in shape, with a single rampart and ditch (univallate), enclosing 4 acres (1.6 ha). A linear outer work about 131 yards (120 m) away, parallel to the westerly rampart, encloses another 4 acres (16,187.4 m²). The name Ruborough comes from Rugan beorh or Ruwan-beorge meaning Rough Hill. The Dowsborough fort has an oval shape, with a single rampart and ditch (univallate) following the contours of the hill top, enclosing an area of 7 acres (2.8 ha). The main entrance is to the east, towards Nether Stowey

, with a simpler opening to the north west, aligned with a ridgeway leading down to Holford. A col

to the south connects the hill to the main Stowey ridge, where a linear earthwork known as Dead Woman's Ditch cuts across the spur.

Little evidence exists of Roman

influence on the Quantock region beyond isolated finds and hints of transient forts. A Roman port was at Combwich

, and it is possible that a Roman road ran from there to the Quantocks, because the names Nether Stowey and Over Stowey

come from the Old English stan wey, meaning stone way. In October 2001 the West Bagborough Hoard

of 4th century Roman

silver

was discovered in West Bagborough

. The 681 coins included two denarii

from the early 2nd century, and eight miliarense

and 671 siliqua

dating to 337–367 AD. The majority were struck in the reigns of emperors Constantius II

and Julian

and derive from a range of mints including Arles

and Lyon

s in France

, Trier

in Germany

and Rome

. The area remained under Romano-British Celtic control until 681–685 AD, when Centwine of Wessex

pushed west from the River Parrett

, conquered the Welsh King Cadwaladr

, and occupied the rest of Somerset north to the Bristol Channel.

Saxon rule was later consolidated under King Ine

, who established a fort at Taunton in about 700 AD.

The first documentary evidence of the village of Crowcombe

is by Æthelwulf of Wessex in 854, where it was spelt 'Cerawicombe'. At that time the manor belonged to Glastonbury Abbey

. In the later Saxon period, King Alfred

led the resistance to Viking

invasion from Athelney

, south-east of the Quantocks. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

, the early port at Watchet

was plundered by Danes in 987 and 997. Alfred established a series of forts and lookout posts linked by a military road, or herepath

, so his army could cover Viking movements at sea. The herepath has a characteristic form that is familiar on the Quantocks: a regulation 66 feet (20 m) wide track between avenues of trees growing from hedge laying

embankments. The herepath ran from the ford on the River Parrett at Combwich, past Cannington hill fort to Over Stowey, where it climbed the Quantocks along the line of the current Stowey road, to Crowcombe Park Gate. Then it went south along the ridge, to Triscombe Stone. One branch may have led past Lydeard Hill and Buncombe Hill, back to Alfred's base at Athelney. The main branch descended the hills at Triscombe, then along the avenue to Red Post Cross, and west to the Brendon Hills

and Exmoor

.

After the Norman conquest of England

in 1066 William de Moyon

was given land at Dunster

, Broomfield and West Quantoxhead

, his son becoming William de Mohun of Dunster, 1st Earl of Somerset, while William Malet

received Enmore

. East Quantoxhead

was given to the Luttrells (previously spelled de Luterel), who passed the manor down through descendants into the 20th century. A Luttell also became the Earl of Carhampton

and acquired Dunster Castle

in 1376, holding it until it became a National Trust

property in 1976.

Stowey Castle

at Nether Stowey was built in the 11th century. The castle is sited on a small isolated knoll, about 390 ft (119 m) high. It consisted of a square keep

(which may have been stone, or a wooden superstructure on stone foundations) and its defences and an outer and an inner bailey

. The mount is 29 ft (9 m) above the 6 ft (2 m) wide ditch which itself is 7 ft (2 m) deep. The motte

has a flat top with two large and two small mounds, which may be sites of towers, at the edge. The blue lias

rubble walling is the only visible structural remains of the castle, which stand on a conical earthwork with a ditch approximately 820 ft (250 m) in circumference. The castle was destroyed in the 15th century, which may have been as a penalty for the local Lord Audley's

involvement in the Second Cornish Uprising of 1497

led by Perkin Warbeck

against the taxes of Henry VII

. Some of the stone was used in the building of Stowey Court in the village.

During the English Civil War

During the English Civil War

Dunster was a Royalist stronghold under the command of Colonel Wyndham. Sir Francis Dodington of Dodington was a local commander. In November 1645 Parliamentary forces started a siege that lasted until an honourable surrender of the castle in April 1646. Royalist

reinforcements for the siege of Dunster Castle were sent by sea to Watchet, but the tide was on the ebb, and a troop of Roundhead

s rode into the shallows and forced the ship to surrender. Thus a ship at sea was taken by a troop of horse. Dunster shared the fate of many other Royalist castles and had its defences demolished to prevent any further use against Parliament. Sir John Stawell

of Cothelstone

had raised a small force at this own expense to defend the King. When Taunton

fell to parliamentary troops and was held by Robert Blake

, he attacked Stawell at Bishops Lydeard

and imprisoned him. After the restoration Charles II

conferred the title of Baron Stawell

on Blake's son Ralph.

At the end of the Monmouth Rebellion

of 1685, (also known as the Pitchfork Rebellion), many participants were executed in the Quantocks. The rebellion was an attempt to overthrow the King of England, James II

, who became king when his elder brother, Charles II

, died on 6 February 1685. James II was unpopular because he was Roman Catholic, and many people were opposed to a "papist

" king. James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth

, claimed to be rightful heir to the throne and attempted to displace James II. The rebellion ended with the defeat of Monmouth's forces at the Battle of Sedgemoor

on 6 July 1685. Monmouth was executed

for treason

on 15 July, and many of his supporters were executed, including some by hanging at Nether Stowey and Cothelstone, or transported

in the Bloody Assizes

of Judge Jeffreys

.

Dodington was the site of the Buckingham Mine where copper

was extracted. The mine was established before 1725 and followed earlier exploration at Perry Hill, East Quantoxhead

. It was financed by the Marquis of Buckingham

until 1801 when it was closed, until various attempts were made to reopen it during the 19th century.

In 1724 the 14th century spire of the Church of the Holy Ghost in Crowcombe was damaged by a lightning strike. The top section of the spire was removed and is now planted in the churchyard, and stone from the spire was used in the flooring of the church. Inside the church, carved bench-ends dating from 1534 depict such pagan subjects as the Green Man

In 1724 the 14th century spire of the Church of the Holy Ghost in Crowcombe was damaged by a lightning strike. The top section of the spire was removed and is now planted in the churchyard, and stone from the spire was used in the flooring of the church. Inside the church, carved bench-ends dating from 1534 depict such pagan subjects as the Green Man

and the legend of the men of Crowcombe fighting a two-headed dragon

.

Norton Fitzwarren was the site of a boat lift on the now unused section of the Grand Western Canal

from 1839 to 1867. A 300-person prisoner of war camp built here during World War II

housed Italian

prisoners from the Western Desert Campaign

and German prisoners from the Battle of Normandy.

lived in Nether Stowey

in the Quantocks from 1797 to 1799. In his memory a footpath, The Coleridge Way

, was set up by the Exmoor

park authorities. The 36 miles (58 km) route begins in Nether Stowey and crosses the Quantocks, the Brendon Hills and Exmoor before finishing in Porlock

.

The Quantock Greenway

is a footpath

that opened in 2001. The route of the path follows a figure of eight centred on Triscombe. The northern loop, taking in Crowcombe

and Holford

, is 19 miles (31 km) long, and the southern loop to Broomfield

extends for 18 miles (29 km). The path travels through many types of landscape, including deciduous and coniferous woodland, private parkland, grazed pasture and cropped fields.

The Macmillan Way West

follows the Quantocks ridge for several miles.

(AONB) in 1956, the first such designation in England under the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949

. Notice of the intention to create the AONB under The Quantock Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (Designation) Order, 1956 was published in the London Gazette

on 7 February 1956. As they have the same landscape quality, AONBs may be compared to the national parks of England and Wales

. AONBs are created under the same legislation as the national park

s. Unlike AONBs, national parks have their own authorities and special legal powers to prevent unsympathetic development. By contrast, few statutory duties are imposed on local authorities within an AONB. However, further regulation and protection of AONBs was added by the Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000

.

Many of the villages on the Quantocks have their own parish councils, which have some responsibility for local issues. They also elect councillors to Somerset County Council

and district councils, such as Taunton Deane

, West Somerset

and Sedgemoor

. Each of the villages is also part of a parliamentary constituency: Taunton Deane

, or Bridgwater and West Somerset. The area is also part of the South West England (European Parliament constituency)

of the European Parliament.

Coleridge Cottage

Coleridge Cottage

is a cottage

situated in Nether Stowey

. It was constructed in the 17th century as a building containing a parlour, kitchen and service room on the ground floor and three corresponding bed chambers above. It has been designated by English Heritage

as a grade II* listed building. The poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge

lived here for three years from 1797 while he wrote The Rime of the Ancient Mariner

, part of Christabel, Frost at Midnight and Kubla Khan

. Having served for many years as Moore's Coleridge Cottage Inn, the building was acquired for the nation in 1908, and the following year it was handed over to the National Trust

. On 23 May 1998, following a £25,000 appeal by the Friends of Coleridge and the National Trust, two further rooms on the first floor were officially opened by William Coleridge, 5th Baron Coleridge.

Poet William Wordsworth

and his sister Dorothy

lived at Alfoxton House

in Holford

between July 1797 and June 1798, during the time of their friendship with Coleridge. The 2000 film Pandaemonium

, based on the lives of Wordsworth and Coleridge, was set in the hills.

Virginia

and Leonard Woolf

spent a few days of their honeymoon at The Plough Inn, Holford, before continuing to the continent in 1912. They returned about a year later to try to help Virginia recover from one of her recurring nervous breakdowns.

The opening of John le Carré

's 1974 novel Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy

is set in the Quantocks. The 1980 Doctor Who

episode "Shada

" makes a sidelong reference to this region – the Fourth Doctor

(played by Tom Baker

) claims that walking through the Time Vortex "is a little trick I learned from a space-time mystic in the Quantocks". In the 1980s and 1990s, English novelist Ruth Elwin Harris wrote her Quantock Quartet, a set of novels centred on four sisters growing up around the Quantock Hills during the early 20th century. The novels were later reprinted by Candlewick Press

. The Quantocks were also the setting for the final episode of the third series (2006) of Peep Show

.

'Checking out the Quantocks', is a line from the song Joy Division Oven Gloves by Half Man Half Biscuit

from their album Achtung Bono

, a green-grey 19th century mansion built from cockercombe tuff

. It was the family home of Henry Labouchere, 1st Baron Taunton

, until the 1960s when it was converted into a school. In 2000, it became a centre for recreation and banqueting and summer camps for youths.

Broomfield

is home to Fyne Court

. Originally the pleasure grounds of pioneer 19th century electrician, Andrew Crosse

. Since 1972 it has been owned by the National Trust

. It has been leased from the National Trust since 1974 by the Somerset Wildlife Trust

(Formally Somerset Trust for Nature Conservation) and is run as a nature reserve

and visitor centre

. The Quantock Hills AONB Service have their headquarters at Fyne Court.

The Church of St Mary in Kingston St Mary

The Church of St Mary in Kingston St Mary

dates from the 13th century, but the tower is from the early 16th century and was re-roofed in 1952, with further restoration from 1976 to 1978. It is a three-stage crenellated

tower, with crocketed pinnacles, bracketed pinnacles set at angles, decorative pierced merlon

s, and set-back buttress

es crowned with pinnacles. The decorative "hunky-punks" are perched high on the corners. These may be so named because the carvings are hunkering (squatting) and are "punch" (short and thick). They serve no function, unlike gargoyle

s that carry off water. The churchyard includes tombs of the Warre family who owned nearby Hestercombe House

, a historic country house

in Cheddon Fitzpaine

visited by about 70,000 people per year. The site includes a 0.2 acres (809.4 m²) biological Site of Special Scientific Interest

notified in 2000. The site is used for roosting by Lesser horseshoe bat

s, and has been designated as a Special Area of Conservation

(SAC). The house was used as the headquarters of the British 8th Corps during the Second World War

, and has been owned by Somerset County Council

since 1951. It is used as an administrative centre and a base for the Somerset Fire and Rescue Service

.

The Norman

Church of St Giles in Thurloxton

dates from the 14th century but is predominantly from the 15th century with 19th century restoration

, including the addition of the north aisle in 1868. It has been designated by English Heritage

as a grade II* listed building. From October 1763 to January 1764 the vicar was the diarist James Woodforde

.

The West Somerset Railway

The West Somerset Railway

(WSR) is a heritage railway

that runs along the edge of the Quantock Hills between Bishops Lydeard

and Watchet

. The line then turns inland to Washford, and returns to the coast for the run to Minehead

. At 23 miles (37 km), it is the longest privately owned passenger rail line in the UK

.

Halsway Manor

in Halsway, is now used as England's National Centre for Traditional Music, Dance and Song. It is the only residential folk

centre in the UK. The eastern end of the building dates from the 15th century and the western end was a 19th century addition. The manor, which is mentioned in the Domesday Book

, was at one time used by Cardinal Beaufort as a hunting lodge and thereafter as a family home until the mid-1960s when it became the folk music centre. It has been designated by English Heritage as a grade II* listed building.

Halswell House

in Goathurst

has Tudor origins but was purchased by the Tynte family and rebuilt in 1689. The surrounding park and 17 acres (6.9 ha) pleasure garden was developed between 1745 and 1785. The grounds contain many fish ponds, cascades, bridges and fanciful buildings, including the Temple of Harmony

, which stands in Mill Wood and has now been fully restored.

Hill

A hill is a landform that extends above the surrounding terrain. Hills often have a distinct summit, although in areas with scarp/dip topography a hill may refer to a particular section of flat terrain without a massive summit A hill is a landform that extends above the surrounding terrain. Hills...

s west of Bridgwater

Bridgwater

Bridgwater is a market town and civil parish in Somerset, England. It is the administrative centre of the Sedgemoor district, and a major industrial centre. Bridgwater is located on the major communication routes through South West England...

in Somerset

Somerset

The ceremonial and non-metropolitan county of Somerset in South West England borders Bristol and Gloucestershire to the north, Wiltshire to the east, Dorset to the south-east, and Devon to the south-west. It is partly bounded to the north and west by the Bristol Channel and the estuary of the...

, England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

. The Quantock Hills were England’s first Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty

Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty

An Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty is an area of countryside considered to have significant landscape value in England, Wales or Northern Ireland, that has been specially designated by the Countryside Agency on behalf of the United Kingdom government; the Countryside Council for Wales on...

being designated in 1956 and consists of large amounts of heathland, oak woodlands, ancient parklands and agricultural land.

The hills run from the Vale of Taunton Deane

Taunton Deane

Taunton Deane is a local government district with borough status in Somerset, England. Its council is based in Taunton.The district was formed on 1 April 1974, under the Local Government Act 1972, by a merger of the Municipal Borough of Taunton, Wellington Urban District, Taunton Rural District,...

in the south, for about 15 miles (24 km) to the north-west, ending at East Quantoxhead

East Quantoxhead

East Quantoxhead is a village in West Somerset, from West Quantoxhead, east of Williton, and west of Bridgwater, within the Quantock Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty in Somerset, England.-History:...

and West Quantoxhead

West Quantoxhead

West Quantoxhead is a small village and civil parish in the West Somerset district of Somerset, England. It lies on the route of the Coleridge Way and on the A39 road at the foot of the Quantock Hills, from East Quantoxhead, from Williton and equidistant from Bridgwater and Taunton...

on the coast of the Bristol Channel

Bristol Channel

The Bristol Channel is a major inlet in the island of Great Britain, separating South Wales from Devon and Somerset in South West England. It extends from the lower estuary of the River Severn to the North Atlantic Ocean...

. They form the western border of Sedgemoor

Sedgemoor

Sedgemoor is a low lying area of land in Somerset, England. It lies close to sea level south of the Polden Hills, historically largely marsh . The eastern part is known as King's Sedgemoor, and the western part West Sedgemoor. Sedgemoor is part of the area now known as the Somerset Levels...

and the Somerset Levels

Somerset Levels

The Somerset Levels, or the Somerset Levels and Moors as they are less commonly but more correctly known, is a sparsely populated coastal plain and wetland area of central Somerset, South West England, between the Quantock and Mendip Hills...

. From the top of the hills on a clear day, it is possible to see Glastonbury Tor

Glastonbury Tor

Glastonbury Tor is a hill at Glastonbury, Somerset, England, which features the roofless St. Michael's Tower. The site is managed by the National Trust. It has been designated as a Scheduled Ancient Monument ....

and the Mendips

Mendip Hills

The Mendip Hills is a range of limestone hills to the south of Bristol and Bath in Somerset, England. Running east to west between Weston-super-Mare and Frome, the hills overlook the Somerset Levels to the south and the Avon Valley to the north...

to the east, Wales

Wales

Wales is a country that is part of the United Kingdom and the island of Great Britain, bordered by England to its east and the Atlantic Ocean and Irish Sea to its west. It has a population of three million, and a total area of 20,779 km²...

as far as the Gower Peninsula

Gower Peninsula

Gower or the Gower Peninsula is a peninsula in south Wales, jutting from the coast into the Bristol Channel, and administratively part of the City and County of Swansea. Locally it is known as "Gower"...

to the north, the Brendon Hills

Brendon Hills

The Brendon Hills are composed of a lofty ridge of hills in the East Lyn Valley area of western Somerset, England. The terrain is broken by a series of deeply incised streams and rivers running roughly southwards to meet the River Haddeo, a tributary of the River Exe.The hills are quite heavily...

and Exmoor

Exmoor

Exmoor is an area of hilly open moorland in west Somerset and north Devon in South West England, named after the main river that flows out of the district, the River Exe. The moor has given its name to a National Park, which includes the Brendon Hills, the East Lyn Valley, the Vale of Porlock and ...

to the west, and the Blackdown Hills

Blackdown Hills

The Blackdown Hills are a range of hills along the Somerset-Devon border in south-western England, which were designated an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty in 1991....

to the south. The highest point on the Quantocks is Wills Neck

Wills Neck

Wills Neck is the highest summit on the Quantock Hills and one of the highest points in Somerset, England. Although only 1261 ft high, it qualifies as one of England's Marilyns...

, at 1261 feet (384 m). Soil types and weather combine to support the hills' plants and animals. In 1970 an area of 6194.5 acres (2,506.8 ha) was designated as a Biological Site of Special Scientific Interest

Site of Special Scientific Interest

A Site of Special Scientific Interest is a conservation designation denoting a protected area in the United Kingdom. SSSIs are the basic building block of site-based nature conservation legislation and most other legal nature/geological conservation designations in Great Britain are based upon...

.

They have been occupied since prehistoric times with Bronze Age

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a period characterized by the use of copper and its alloy bronze as the chief hard materials in the manufacture of some implements and weapons. Chronologically, it stands between the Stone Age and Iron Age...

round barrow

Round barrow

Round barrows are one of the most common types of archaeological monuments. Although concentrated in Europe they are found in many parts of the world because of their simple construction and universal purpose....

s and Iron Age

Iron Age

The Iron Age is the archaeological period generally occurring after the Bronze Age, marked by the prevalent use of iron. The early period of the age is characterized by the widespread use of iron or steel. The adoption of such material coincided with other changes in society, including differing...

hill forts. Evidence from Roman

Ancient Rome

Ancient Rome was a thriving civilization that grew on the Italian Peninsula as early as the 8th century BC. Located along the Mediterranean Sea and centered on the city of Rome, it expanded to one of the largest empires in the ancient world....

times includes silver

Silver

Silver is a metallic chemical element with the chemical symbol Ag and atomic number 47. A soft, white, lustrous transition metal, it has the highest electrical conductivity of any element and the highest thermal conductivity of any metal...

coins discovered in West Bagborough

West Bagborough

West Bagborough is a village and civil parish in Somerset, England, situated north of Taunton in the Taunton Deane district. The village has a population of 394....

. In the later Saxon period, King Alfred

Alfred the Great

Alfred the Great was King of Wessex from 871 to 899.Alfred is noted for his defence of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of southern England against the Vikings, becoming the only English monarch still to be accorded the epithet "the Great". Alfred was the first King of the West Saxons to style himself...

led the resistance to Viking

Viking

The term Viking is customarily used to refer to the Norse explorers, warriors, merchants, and pirates who raided, traded, explored and settled in wide areas of Europe, Asia and the North Atlantic islands from the late 8th to the mid-11th century.These Norsemen used their famed longships to...

invasion, and Watchet

Watchet

Watchet is a harbour town and civil parish in the English county of Somerset, with an approximate population of 4,400. It is situated west of Bridgwater, north-west of Taunton, and east of Minehead. The parish includes the hamlet of Beggearn Huish...

was plundered by Danes in 987 and 997. The hills were fought over during the English Civil War

English Civil War

The English Civil War was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between Parliamentarians and Royalists...

and Monmouth Rebellion

Monmouth Rebellion

The Monmouth Rebellion,The Revolt of the West or The West Country rebellion of 1685, was an attempt to overthrow James II, who had become King of England, King of Scots and King of Ireland at the death of his elder brother Charles II on 6 February 1685. James II was a Roman Catholic, and some...

but are now a peaceful area popular with walkers, mountain bikers, horse riders and tourists. They explore paths such as the Coleridge Way

Coleridge Way

The Coleridge Way is a footpath in Somerset, England.It was opened in April 2005, and follows the walks taken by poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, to Porlock, starting from Coleridge Cottage at Nether Stowey, where he once lived.The footpath is waymarked...

used by the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Samuel Taylor Coleridge was an English poet, Romantic, literary critic and philosopher who, with his friend William Wordsworth, was a founder of the Romantic Movement in England and a member of the Lake Poets. He is probably best known for his poems The Rime of the Ancient Mariner and Kubla...

, who lived in Nether Stowey

Nether Stowey

Nether Stowey is a large village in the Sedgemoor district of Somerset, South West England. It sits in the foothills of the Quantock Hills , just below Over Stowey...

from 1797 to 1799, or visit places of interest such as Quantock Lodge

Quantock Lodge

] Quantock Lodge is a green-grey nineteenth-century mansion built by Henry Clutton from Cockercombe tuff and is located near the hamlet of Aley, near the village of Over Stowey in the English county of Somerset. It was the family home of Henry Labouchere, 1st Baron Taunton, and in the 1960s was...

.

Etymology

The name first appears in SaxonAnglo-Saxons

Anglo-Saxon is a term used by historians to designate the Germanic tribes who invaded and settled the south and east of Great Britain beginning in the early 5th century AD, and the period from their creation of the English nation to the Norman conquest. The Anglo-Saxon Era denotes the period of...

charters in around AD 880 as Cantuctun and two centuries later in the Domesday Book

Domesday Book

Domesday Book , now held at The National Archives, Kew, Richmond upon Thames in South West London, is the record of the great survey of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086...

as Cantoctona and Cantetone. The name means settlement by a rim or circle of hills; Cantuc is Celtic

Celtic languages

The Celtic languages are descended from Proto-Celtic, or "Common Celtic"; a branch of the greater Indo-European language family...

for a rim or circle, and -ton or -tun is Old English for a settlement. An alternative meaning is ridge of the Welshman, probably referring to a Saxon tribe that fought a battle locally.

Geology

Devonian

The Devonian is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic Era spanning from the end of the Silurian Period, about 416.0 ± 2.8 Mya , to the beginning of the Carboniferous Period, about 359.2 ± 2.5 Mya...

period, which consist of sediments originally laid down under a shallow sea and slowly compressed into solid rock. In the higher north-western areas older Early Devonian rocks known as Hangman Grits predominate and can be seen in the exposed rock at West Quantoxhead

West Quantoxhead

West Quantoxhead is a small village and civil parish in the West Somerset district of Somerset, England. It lies on the route of the Coleridge Way and on the A39 road at the foot of the Quantock Hills, from East Quantoxhead, from Williton and equidistant from Bridgwater and Taunton...

quarry, which was worked for road building. Further south there are newer Middle and Late Devonian rocks, known as Ilfracombe beds and Morte Slates. These include sandstone and limestone, which have been quarried near Aisholt. At Great Holwell, south of Aisholt, is the only limestone cave in the Devonian limestone of North Devon

Devon

Devon is a large county in southwestern England. The county is sometimes referred to as Devonshire, although the term is rarely used inside the county itself as the county has never been officially "shired", it often indicates a traditional or historical context.The county shares borders with...

and West Somerset. The lower fringes around the hills are composed of younger New Red Sandstone

New Red Sandstone

The New Red Sandstone is a chiefly British geological term for the beds of red sandstone and associated rocks laid down throughout the Permian to the beginning of the Triassic that underlie the Jurassic Lias; the term distinguishes it from the Old Red Sandstone which is largely Devonian in...

rocks of the Triassic

Triassic

The Triassic is a geologic period and system that extends from about 250 to 200 Mya . As the first period of the Mesozoic Era, the Triassic follows the Permian and is followed by the Jurassic. Both the start and end of the Triassic are marked by major extinction events...

period. These rocks were laid down in a shallow sea and often contain irregular masses or veins of gypsum

Gypsum

Gypsum is a very soft sulfate mineral composed of calcium sulfate dihydrate, with the chemical formula CaSO4·2H2O. It is found in alabaster, a decorative stone used in Ancient Egypt. It is the second softest mineral on the Mohs Hardness Scale...

, which was mined on the foreshore at Watchet

Watchet

Watchet is a harbour town and civil parish in the English county of Somerset, with an approximate population of 4,400. It is situated west of Bridgwater, north-west of Taunton, and east of Minehead. The parish includes the hamlet of Beggearn Huish...

.

Several areas have outcrops of slates. Younger rocks of the Jurassic

Jurassic

The Jurassic is a geologic period and system that extends from about Mya to Mya, that is, from the end of the Triassic to the beginning of the Cretaceous. The Jurassic constitutes the middle period of the Mesozoic era, also known as the age of reptiles. The start of the period is marked by...

period can be found between St Audries and Kilve

Kilve

Kilve is a village in West Somerset, England, within the Quantock Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, the first AONB to be established, in 1957....

. This area falls within the Blue Anchor to Lilstock

Blue Anchor to Lilstock Coast SSSI

Blue Anchor to Lilstock Coast SSSI is a 742.8 hectare geological Site of Special Scientific Interest between Blue Anchor and Lilstock in Somerset, notified in 1971....

Site of Special Scientific Interest

Site of Special Scientific Interest

A Site of Special Scientific Interest is a conservation designation denoting a protected area in the United Kingdom. SSSIs are the basic building block of site-based nature conservation legislation and most other legal nature/geological conservation designations in Great Britain are based upon...

(SSSI) and is considered to be of international geological importance.

Kilve has the remains of a red-brick retort

Retort

In a chemistry laboratory, a retort is a glassware device used for distillation or dry distillation of substances. It consists of a spherical vessel with a long downward-pointing neck. The liquid to be distilled is placed in the vessel and heated...

built in 1924 after the shale in the cliffs was found to be rich in oil. Along this coast, the cliffs are layered with compressed strata of oil-bearing shale and blue

Blue Lias

The Blue Lias is a geologic formation in southern, eastern and western England and parts of South Wales, part of the Lias Group. The Blue Lias consists of a sequence of limestone and shale layers, laid down in latest Triassic and early Jurassic times, between 195 and 200 million years ago...

, yellow and brown Lias

Early Jurassic

The Early Jurassic epoch is the earliest of three epochs of the Jurassic period...

embedded with fossil

Fossil

Fossils are the preserved remains or traces of animals , plants, and other organisms from the remote past...

s. The Shaline Company was founded in 1924 to exploit these strata but was unable to raise sufficient capital. The company's retort house is thought to be the first structure erected here for the conversion of shale to oil and is all that remains of the anticipated Somerset oil boom.

At Blue Anchor

Blue Anchor

Blue Anchor is a seaside village, in the parish of Old Cleeve, close to Carhampton in the West Somerset district of Somerset, England. The village takes its name from a 17th century inn....

the coloured alabaster

Alabaster

Alabaster is a name applied to varieties of two distinct minerals, when used as a material: gypsum and calcite . The former is the alabaster of the present day; generally, the latter is the alabaster of the ancients...

found in the cliffs gave rise to the name of the colour "Watchet Blue". The village has the only updraught brick kiln

Kiln

A kiln is a thermally insulated chamber, or oven, in which a controlled temperature regime is produced. Uses include the hardening, burning or drying of materials...

known to have survived in Somerset. It was built around 1830 and was supplied by small vessels carrying limestone to the small landing jetty

Jetty

A jetty is any of a variety of structures used in river, dock, and maritime works that are generally carried out in pairs from river banks, or in continuation of river channels at their outlets into deep water; or out into docks, and outside their entrances; or for forming basins along the...

. Now used as a garage, the kiln is thought to have operated until the 1870s, when the large-scale production of bricks in Bridgwater

Bridgwater

Bridgwater is a market town and civil parish in Somerset, England. It is the administrative centre of the Sedgemoor district, and a major industrial centre. Bridgwater is located on the major communication routes through South West England...

rendered small brickyards uneconomic.

Cockercombe tuff

Cockercombe tuff

Cockercombe Tuff is a greenish-grey, hard pyroclastic rock, formed by the compression of volcanic ash containing high quantities of chlorite, which gives it its distinctive colour...

is a greenish-grey, hard sedimentary rock formed by the compression of volcanic ash and is found almost exclusively in the south-eastern end of the Quantock Hills.

Climate

Along with the rest of South West EnglandSouth West England

South West England is one of the regions of England defined by the Government of the United Kingdom for statistical and other purposes. It is the largest such region in area, covering and comprising Bristol, Gloucestershire, Somerset, Dorset, Wiltshire, Devon, Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly. ...

, the Quantock Hills has a temperate climate that is generally wetter and milder than the rest of England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

. The mean temperature is approximately 10 °C (50 °F) and shows a season

Season

A season is a division of the year, marked by changes in weather, ecology, and hours of daylight.Seasons result from the yearly revolution of the Earth around the Sun and the tilt of the Earth's axis relative to the plane of revolution...

al and a diurnal

Diurnal motion

Diurnal motion is an astronomical term referring to the apparent daily motion of stars around the Earth, or more precisely around the two celestial poles. It is caused by the Earth's rotation on its axis, so every star apparently moves on a circle, that is called the diurnal circle. The time for...

variation, but because of the modifying effect of the sea the range is less than in most other parts of the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

(UK). January is the coldest month with mean minimum temperatures between 1 °C (33.8 °F) and 2 °C (35.6 °F). July and August are the warmest months, with mean daily maxima around 21 °C (69.8 °F). December is normally the most cloudy month and June the sunniest. High pressure over the Azores

Azores

The Archipelago of the Azores is composed of nine volcanic islands situated in the middle of the North Atlantic Ocean, and is located about west from Lisbon and about east from the east coast of North America. The islands, and their economic exclusion zone, form the Autonomous Region of the...

often brings clear skies to south-west England, particularly in summer.

Cloud

Cumulus cloud

Cumulus clouds are a type of cloud with noticeable vertical development and clearly defined edges. Cumulus means "heap" or "pile" in Latin. They are often described as "puffy" or "cotton-like" in appearance. Cumulus clouds may appear alone, in lines, or in clusters...

often forms inland especially near hills, and acts to reduce sunshine. The average annual sunshine totals around 1,600 hours. Rainfall tends to be associated with Atlantic

Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's oceanic divisions. With a total area of about , it covers approximately 20% of the Earth's surface and about 26% of its water surface area...

depressions or with convection. In summer, convection caused by solar surface heating sometimes forms shower clouds, and a large proportion of rain falls from showers and thunderstorms at this time of year. Average rainfall is around 31 to 35 in (787.4 to 889 mm). About 8 to 15 days of snowfall is typical. From November to March, mean wind speeds are highest; winds are lightest from June to August. The predominant wind direction is from the south-west.

Ecology

In 1970 an area of 6194.5 acres (2,506.8 ha) in the Quantocks was designated as a Biological Site of Special Scientific InterestSite of Special Scientific Interest

A Site of Special Scientific Interest is a conservation designation denoting a protected area in the United Kingdom. SSSIs are the basic building block of site-based nature conservation legislation and most other legal nature/geological conservation designations in Great Britain are based upon...

(SSSI). This a conservation designation

Conservation designation

A conservation designation is a name and/or acronym which explains the status of an area of land in terms of conservation or protection.-United Kingdom:*Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty *Environmentally Sensitive Area*Local Nature Reserve...

denoting a protected area

Protected area

Protected areas are locations which receive protection because of their recognised natural, ecological and/or cultural values. There are several kinds of protected areas, which vary by level of protection depending on the enabling laws of each country or the regulations of the international...

in the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

, selected by Natural England

Natural England

Natural England is the non-departmental public body of the UK government responsible for ensuring that England's natural environment, including its land, flora and fauna, freshwater and marine environments, geology and soils, are protected and improved...

, for areas with particular landscape and ecological characteristics. It provides some protection from development, from other damage, and (since 2000) also from neglect, under the Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000

Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000

The Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000 is a UK Act of Parliament which came into force on 30 November 2000.As of September 2007, not all sections of the Countryside and Rights of Way Act have yet come into force...

.

The streams and open water such as Hawkridge Reservoir

Hawkridge Reservoir

Hawkridge Reservoir is a reservoir near Spaxton, Somerset, England. The inflow is from several streams in the Quantock Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty including Peart Water and water flows out into Cannington Brook, which is dammed further downstream to make the Ashford Reservoir which was...

and Ashford Reservoir

Ashford Reservoir

Ashford Reservoir is a small reservoir on the eastern side of the Quantock Hills near the villages of Charlynch and Spaxton in Somerset, England. It was constructed 1934 as a water supply reservoir for Bridgwater...

on Cannington Brook

Cannington Brook

Cannington brook is a stream in Somerset, England that originates in the Quantock Hills, which is designated a Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty....

also provide habitats for a range of species.

Flora

Escarpment

An escarpment is a steep slope or long cliff that occurs from erosion or faulting and separates two relatively level areas of differing elevations.-Description and variants:...

slopes of pasture, woods and parkland. Deep stream-cut combes

Valley

In geology, a valley or dale is a depression with predominant extent in one direction. A very deep river valley may be called a canyon or gorge.The terms U-shaped and V-shaped are descriptive terms of geography to characterize the form of valleys...

to the north-east contain extensive oak-woods with small flower-rich bogs above them. The areas where there is limited drainage are dominated by Heather

Calluna

Calluna vulgaris is the sole species in the genus Calluna in the family Ericaceae. It is a low-growing perennial shrub growing to tall, or rarely to and taller, and is found widely in Europe and Asia Minor on acidic soils in open sunny situations and in moderate shade...

(Calluna vulgaris), with significant populations of Cross-leaved Heath

Erica tetralix

Erica tetralix is a species of heather found in Atlantic areas of Europe, from southern Portugal to central Norway, as well as a number of boggy regions further from the coast in Central Europe. In bogs, wet heaths and damp coniferous woodland, Erica tetralix can become a dominant part of the flora...

(Erica tetralix), Purple Moor-grass (Molinia caerulea), Bilberry

Bilberry

Bilberry is any of several species of low-growing shrubs in the genus Vaccinium , bearing edible berries. The species most often referred to is Vaccinium myrtillus L., but there are several other closely related species....

(Vaccinium myrtillus) and Wavy Hair-grass

Deschampsia

Deschampsia is a genus of grasses in the family Poaceae, commonly known as hair grass or tussock grass. There are 30 to 40 species....

(Deschampsia flexuosa). Drier areas are covered with Bell Heather

Erica cinerea

Erica cinerea is a species of heather, native to western and central Europe. It is a low shrub growing to tall, with fine needle-like leaves long arranged in whorls of three...

(Erica cinerea), Western Gorse (Ulex gallii) and Bristle Bent

Agrostis

Agrostis is a genus of over 100 species belonging to the grass family Poaceae, commonly referred to as the bent grasses...

(Agrostis curtisii), while Bracken

Bracken

Bracken are several species of large, coarse ferns of the genus Pteridium. Ferns are vascular plants that have alternating generations, large plants that produce spores and small plants that produce sex cells . Brackens are in the family Dennstaedtiaceae, which are noted for their large, highly...

(Pteridium aquilinum) is common on well-drained deeper soils. The springs and streams provide a specialist environment that supports Bog pimpernel

Anagallis tenella

Anagallis tenella known in Britain as the Bog Pimpernel, is a low growing, perennial plant found in a variety of damp habitats from calcareous dune slacks to boggy and peaty heaths in Eurasia but absent from North America...

(Anagallis tenella). The woodland is generally Birch/Sessile Oak woodland, Valley Alder woodland and Ash/Wych Elm woodland, which support a rich lichen

Lichen

Lichens are composite organisms consisting of a symbiotic organism composed of a fungus with a photosynthetic partner , usually either a green alga or cyanobacterium...

flora. Alfoxton Wood is one of only three British locations where the lichen Tomasellia lectea is present.

Fauna

The various habitats, together with the wide range of slopes and aspects, provide ideal conditionsfor a rich fauna. Amphibian

Amphibian

Amphibians , are a class of vertebrate animals including animals such as toads, frogs, caecilians, and salamanders. They are characterized as non-amniote ectothermic tetrapods...

s such as the Palmate Newt

Palmate Newt

The Palmate Newt is a species of newt found in most of Western Europe, including Great Britain. It is protected by law in all countries where it occurs, and is thought to be extremely rare to endangered in the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg and vulnerable in Spain and Poland but common...

(Triturus helveticus), Common Frog

Common Frog

The Common Frog, Rana temporaria also known as the European Common Frog or European Common Brown Frog is found throughout much of Europe as far north as well north of the Arctic Circle in Scandinavia and as far east as the Urals, except for most of Iberia, southern Italy, and the southern Balkans...

(Rana

temporaris), and Common toad

Common Toad

The common toad or European toad is an amphibian widespread throughout Europe, with the exception of Iceland, Ireland and some Mediterranean islands...

(Bufo bufo) are represented in the damper environments. Reptiles

present include Adder (Vipera berus

Vipera berus

Vipera berus, the common European adder or common European viper, is a venomous viper species that is extremely widespread and can be found throughout most of Western Europe and all the way to Far East Asia. Known by a host of common names including Common adder and Common viper, adders have been...

), Grass Snake

Grass Snake

The grass snake , sometimes called the ringed snake or water snake is a European non-venomous snake. It is often found near water and feeds almost exclusively on amphibians.-Etymology:...

(Natrix natrix), Slow Worm

Anguis fragilis

Anguis fragilis, or slow worm, slow-worm or slowworm, is a limbless reptile native to Eurasia. It is also sometimes referred to as the blindworm or blind worm, though the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds considers this to be incorrect.Slow worms are semi-fossorial lizards spending much...

(Angula fragilis) and Common Lizard

Viviparous lizard

The viviparous lizard or common lizard is a Eurasian lizard. It lives farther north than any other reptile species, and most populations are viviparous , rather than laying eggs as most other lizards do.-Identification:The length of the body is less than...

(Lacerta vivipara). Many bird species breed on the Quantocks, including the Grasshopper Warbler

Grasshopper Warbler

The Grasshopper Warbler, Locustella naevia, is an Old World warbler in the grass warbler genus Locustella. It breeds across much of temperate Europe and Asia. It is migratory, wintering from northwest Africa to India....

(Locustella naevia), Nightjar

Nightjar

Nightjars are medium-sized nocturnal or crepuscular birds with long wings, short legs and very short bills. They are sometimes referred to as goatsuckers from the mistaken belief that they suck milk from goats . Some New World species are named as nighthawks...

(Caprimulgus europaeus), Raven

Raven

Raven is the common name given to several larger-bodied members of the genus Corvus—but in Europe and North America the Common Raven is normally implied...

(Corvus corax) and the European Pied Flycatcher

European Pied Flycatcher

The Pied Flycatcher, Ficedula hypoleuca, is a small passerine bird in the Old World flycatcher family, one of the four species of Western Palearctic black-and-white flycatchers. It breeds in most of Europe and western Asia. It is migratory, wintering mainly in western Africa. It hybridizes with...

(Ficedula hypoleuca). The Quantocks are also an important site for Red deer

Red Deer

The red deer is one of the largest deer species. Depending on taxonomy, the red deer inhabits most of Europe, the Caucasus Mountains region, Asia Minor, parts of western Asia, and central Asia. It also inhabits the Atlas Mountains region between Morocco and Tunisia in northwestern Africa, being...

(Cervus elaphus). Invertebrates of note include the Silver-washed Fritillary

Silver-washed Fritillary

Argynnis paphia is a common and variable butterfly found over much of the Palaearctic ecozone – Algeria, Europe, temperate Asia and Japan.-Subspecies:*A. p. butleri Krulikovsky, 1909 Northern Europe, Central Europe...

butterfly (Argynnis paphia), and three nationally rare dead-wood beetles: Thymalus limbatus, Orchesia undulata and Rhinosimus ruficollis.

History

Evidence of activity in the Quantocks from prehistoric times includes finds of MesolithicMesolithic

The Mesolithic is an archaeological concept used to refer to certain groups of archaeological cultures defined as falling between the Paleolithic and the Neolithic....

flints at North Petherton

North Petherton

North Petherton is a small town and civil parish in Somerset, England, situated on the edge of the eastern foothills of the Quantocks, and close to the edge of the Somerset Levels.The town has a population of 5,189...

and Broomfield

Broomfield, Somerset

Broomfield is a village and civil parish in the Sedgemoor district of Somerset, England, situated about five miles north of Taunton. According to the 2001 census it had a population of 224....

and many Bronze Age

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a period characterized by the use of copper and its alloy bronze as the chief hard materials in the manufacture of some implements and weapons. Chronologically, it stands between the Stone Age and Iron Age...

round barrow

Round barrow

Round barrows are one of the most common types of archaeological monuments. Although concentrated in Europe they are found in many parts of the world because of their simple construction and universal purpose....

s (marked on maps as tumulus

Tumulus

A tumulus is a mound of earth and stones raised over a grave or graves. Tumuli are also known as barrows, burial mounds, Hügelgrab or kurgans, and can be found throughout much of the world. A tumulus composed largely or entirely of stones is usually referred to as a cairn...

, plural tumuli), such as Thorncombe Barrow above Bicknoller

Bicknoller

Bicknoller is a village and civil parish on the western slopes of the Quantock Hills in the English county of Somerset.Administratively, the civil parish falls within the West Somerset local government district within the Somerset shire county, with administrative tasks shared between county,...

. Several ancient stones can be seen, such as the Triscombe Stone and the Long Stone above Holford

Holford

Holford is a village and civil parish in West Somerset within the Quantock Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, and about west of Bridgwater and east of Williton. The village has a population of about 200. The village is on the Quantock Greenway and Coleridge Way footpaths...

. Many of the tracks along ridges of the Quantocks probably originated as ancient ridgeway

Ridgeway (track)

Ridgeways are a particular type of ancient road that exploits the hard surface of hilltop ridges for use as unpaved, zero-maintenance roads, though they often have the disadvantage of steeper gradients along their courses, and sometimes quite narrow widths. Before the advent of turnpikes or toll...

s. A Bronze Age hill fort

Hill fort

A hill fort is a type of earthworks used as a fortified refuge or defended settlement, located to exploit a rise in elevation for defensive advantage. They are typically European and of the Bronze and Iron Ages. Some were used in the post-Roman period...

, Norton Camp

Norton Camp

Norton Camp is a Bronze Age hill fort at Norton Fitzwarren near Taunton in Somerset, England.-Background:Hill forts developed in the Late Bronze and Early Iron Age, roughly the start of the first millennium BC. The reason for their emergence in Britain, and their purpose, has been a subject of...

, was built to the south at Norton Fitzwarren

Norton Fitzwarren

Norton Fitzwarren is a village and civil parish in Somerset, England, situated north west of Taunton in the Taunton Deane district. The village has a population of 2,325.-History:...

, close to the centre of bronze making in Taunton

Taunton

Taunton is the county town of Somerset, England. The town, including its suburbs, had an estimated population of 61,400 in 2001. It is the largest town in the shire county of Somerset....

.

Iron Age

The Iron Age is the archaeological period generally occurring after the Bronze Age, marked by the prevalent use of iron. The early period of the age is characterized by the widespread use of iron or steel. The adoption of such material coincided with other changes in society, including differing...

sites in the Quantocks include major hill forts at Dowsborough

Dowsborough

Dowsborough Camp is an Iron Age hill fort on the Quantock Hills near Nether Stowey in Somerset, England. It has been designated as a Scheduled Ancient Monument .-Background:...

and Ruborough, as well as several smaller earthwork enclosures, such as Trendle Ring

Trendle Ring

Trendle Ring is an Iron Age earthwork on the Quantock Hills near Bicknoller in Somerset, England. It is a Scheduled Ancient Monument .The word trendle means circle, so it is a tautological place name....

and Plainsfield Camp

Plainsfield Camp

Plainsfield Camp is a possible Iron Age earthwork on the Quantock Hills near Aisholt in Somerset, England.The so-called hill fort has several features that make it more likely to be an animal enclosure, than a defended settlement:...

. Ruborough near Broomfield

Broomfield, Somerset

Broomfield is a village and civil parish in the Sedgemoor district of Somerset, England, situated about five miles north of Taunton. According to the 2001 census it had a population of 224....

is on an easterly spur from the main Quantock ridge, with steep natural slopes to the north and south east. The fort is triangular in shape, with a single rampart and ditch (univallate), enclosing 4 acres (1.6 ha). A linear outer work about 131 yards (120 m) away, parallel to the westerly rampart, encloses another 4 acres (16,187.4 m²). The name Ruborough comes from Rugan beorh or Ruwan-beorge meaning Rough Hill. The Dowsborough fort has an oval shape, with a single rampart and ditch (univallate) following the contours of the hill top, enclosing an area of 7 acres (2.8 ha). The main entrance is to the east, towards Nether Stowey

Nether Stowey

Nether Stowey is a large village in the Sedgemoor district of Somerset, South West England. It sits in the foothills of the Quantock Hills , just below Over Stowey...

, with a simpler opening to the north west, aligned with a ridgeway leading down to Holford. A col

Mountain pass

A mountain pass is a route through a mountain range or over a ridge. If following the lowest possible route, a pass is locally the highest point on that route...

to the south connects the hill to the main Stowey ridge, where a linear earthwork known as Dead Woman's Ditch cuts across the spur.

Little evidence exists of Roman

Ancient Rome

Ancient Rome was a thriving civilization that grew on the Italian Peninsula as early as the 8th century BC. Located along the Mediterranean Sea and centered on the city of Rome, it expanded to one of the largest empires in the ancient world....

influence on the Quantock region beyond isolated finds and hints of transient forts. A Roman port was at Combwich

Combwich

Combwich is a village in the parish of Otterhampton within the Sedgemoor district of Somerset, between Bridgwater and the Steart Peninsula.The village lies on Combwich Reach as the River Parrett flows to the sea and was the site of an ancient ferry crossing. In the Domesday book it was known as...

, and it is possible that a Roman road ran from there to the Quantocks, because the names Nether Stowey and Over Stowey

Over Stowey

Over Stowey is a small village and civil parish in the Sedgemoor district of Somerset, South West England. It sits in the foothills of the Quantock Hills, just below Nether Stowey and north-west of Bridgwater...

come from the Old English stan wey, meaning stone way. In October 2001 the West Bagborough Hoard

West Bagborough Hoard

The West Bagborough Hoard is a hoard of 670 Roman coins and 72 pieces of hacksilver found in October 2001 by metal detectorist James Hawkesworth near West Bagborough in Somerset, England.-Discovery, excavation and valuation:...

of 4th century Roman

Ancient Rome

Ancient Rome was a thriving civilization that grew on the Italian Peninsula as early as the 8th century BC. Located along the Mediterranean Sea and centered on the city of Rome, it expanded to one of the largest empires in the ancient world....

silver

Silver

Silver is a metallic chemical element with the chemical symbol Ag and atomic number 47. A soft, white, lustrous transition metal, it has the highest electrical conductivity of any element and the highest thermal conductivity of any metal...

was discovered in West Bagborough

West Bagborough

West Bagborough is a village and civil parish in Somerset, England, situated north of Taunton in the Taunton Deane district. The village has a population of 394....

. The 681 coins included two denarii

Denarius

In the Roman currency system, the denarius was a small silver coin first minted in 211 BC. It was the most common coin produced for circulation but was slowly debased until its replacement by the antoninianus...

from the early 2nd century, and eight miliarense

Miliarense

A miliarense was the only fairly regularly minted silver coin issued by the late Roman and Byzantine Empires. It was struck with variable fineness, generally with a weight between 3.8 and 6.0 grams. The miliarense was struck from the beginning of the 4th century under Constantine I with a...

and 671 siliqua

Siliqua

The siliqua is the modern name given to small, thin, Roman silver coins produced from 4th century and later. When the coins were in circulation, the Latin word siliqua was a unit of weight defined as one-twentyfourth of the weight of a Roman solidus .The term siliqua comes from the siliqua graeca,...

dating to 337–367 AD. The majority were struck in the reigns of emperors Constantius II

Constantius II

Constantius II , was Roman Emperor from 337 to 361. The second son of Constantine I and Fausta, he ascended to the throne with his brothers Constantine II and Constans upon their father's death....

and Julian

Didius Julianus

Didius Julianus , was Roman Emperor for three months during the year 193. He ascended the throne after buying it from the Praetorian Guard, who had assassinated his predecessor Pertinax. This led to the Roman Civil War of 193–197...

and derive from a range of mints including Arles

Arles

Arles is a city and commune in the south of France, in the Bouches-du-Rhône department, of which it is a subprefecture, in the former province of Provence....

and Lyon

Lyon

Lyon , is a city in east-central France in the Rhône-Alpes region, situated between Paris and Marseille. Lyon is located at from Paris, from Marseille, from Geneva, from Turin, and from Barcelona. The residents of the city are called Lyonnais....

s in France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

, Trier

Trier

Trier, historically called in English Treves is a city in Germany on the banks of the Moselle. It is the oldest city in Germany, founded in or before 16 BC....

in Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

and Rome

Rome

Rome is the capital of Italy and the country's largest and most populated city and comune, with over 2.7 million residents in . The city is located in the central-western portion of the Italian Peninsula, on the Tiber River within the Lazio region of Italy.Rome's history spans two and a half...

. The area remained under Romano-British Celtic control until 681–685 AD, when Centwine of Wessex

Centwine of Wessex

Centwine was King of Wessex from circa 676 to 685 or 686, although he was perhaps not the only king of the West Saxons at the time.The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reports that Centwine became king circa 676, succeeding Æscwine...

pushed west from the River Parrett

River Parrett

The River Parrett flows through the counties of Dorset and Somerset in South West England, from its source in the Thorney Mills springs in the hills around Chedington in Dorset...

, conquered the Welsh King Cadwaladr

Cadwaladr

Cadwaladr ap Cadwallon was King of Gwynedd . Two devastating plagues happened during his reign, one in 664 and the other in 682, with himself a victim of the second one. Little else is known of his reign...

, and occupied the rest of Somerset north to the Bristol Channel.

Saxon rule was later consolidated under King Ine

Ine of Wessex

Ine was King of Wessex from 688 to 726. He was unable to retain the territorial gains of his predecessor, Cædwalla, who had brought much of southern England under his control and expanded West Saxon territory substantially...

, who established a fort at Taunton in about 700 AD.

The first documentary evidence of the village of Crowcombe

Crowcombe

Crowcombe is a village and civil parish under the Quantock Hills in Somerset, England, south east of Watchet, and from Taunton in the Taunton Deane district...

is by Æthelwulf of Wessex in 854, where it was spelt 'Cerawicombe'. At that time the manor belonged to Glastonbury Abbey

Glastonbury Abbey

Glastonbury Abbey was a monastery in Glastonbury, Somerset, England. The ruins are now a grade I listed building, and a Scheduled Ancient Monument and are open as a visitor attraction....

. In the later Saxon period, King Alfred

Alfred the Great

Alfred the Great was King of Wessex from 871 to 899.Alfred is noted for his defence of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of southern England against the Vikings, becoming the only English monarch still to be accorded the epithet "the Great". Alfred was the first King of the West Saxons to style himself...

led the resistance to Viking

Viking

The term Viking is customarily used to refer to the Norse explorers, warriors, merchants, and pirates who raided, traded, explored and settled in wide areas of Europe, Asia and the North Atlantic islands from the late 8th to the mid-11th century.These Norsemen used their famed longships to...

invasion from Athelney

Athelney

Athelney is located between the villages of Burrowbridge and East Lyng in the Sedgemoor district of Somerset, England. The area is known as the Isle of Athelney, because it was once a very low isolated island in the 'very great swampy and impassable marshes' of the Somerset Levels. Much of the...

, south-east of the Quantocks. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is a collection of annals in Old English chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The original manuscript of the Chronicle was created late in the 9th century, probably in Wessex, during the reign of Alfred the Great...

, the early port at Watchet

Watchet

Watchet is a harbour town and civil parish in the English county of Somerset, with an approximate population of 4,400. It is situated west of Bridgwater, north-west of Taunton, and east of Minehead. The parish includes the hamlet of Beggearn Huish...

was plundered by Danes in 987 and 997. Alfred established a series of forts and lookout posts linked by a military road, or herepath

Herepath

A Herepath or Herewag is a military road in England, typically dating from the ninth century CE.This was a time of war between the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of southern England and Viking invaders from Denmark...

, so his army could cover Viking movements at sea. The herepath has a characteristic form that is familiar on the Quantocks: a regulation 66 feet (20 m) wide track between avenues of trees growing from hedge laying

Hedge laying

Hedge laying is a country skill, typically found in the United Kingdom and Ireland, which, through the creation and maintenance of hedges, achieves the following:* the formation of livestock-proof barriers;...