Virus

Encyclopedia

A virus is a small infectious agent

that can replicate only inside the living cells of organisms. Viruses infect all types of organisms, from animal

s and plant

s to bacteria

and archaea

. Since Dmitri Ivanovsky's 1892 article describing a non-bacterial pathogen infecting tobacco plants, and the discovery of the tobacco mosaic virus

by Martinus Beijerinck

in 1898, about 5,000 viruses have been described in detail, although there are millions of different types. Viruses are found in almost every ecosystem

on Earth and are the most abundant type of biological entity. The study of viruses is known as virology

, a sub-speciality of microbiology

.

Virus particles (known as virions) consist of two or three parts: the genetic material made from either DNA

or RNA

, long molecule

s that carry genetic information; a protein

coat that protects these genes; and in some cases an envelope

of lipid

s that surrounds the protein coat when they are outside a cell. The shapes of viruses range from simple helical

and icosahedral

forms to more complex structures. The average virus is about one one-hundredth the size of the average bacterium. Most viruses are too small to be seen directly with a light microscope

.

The origins of viruses in the evolutionary history of life

are unclear: some may have evolved

from plasmid

s – pieces of DNA that can move between cells – while others may have evolved from bacteria. In evolution, viruses are an important means of horizontal gene transfer

, which increases genetic diversity

.

Viruses spread in many ways; viruses in plant

s are often transmitted from plant to plant by insect

s that feed on the sap

of plants, such as aphid

s; viruses in animal

s can be carried by blood-sucking

insects. These disease-bearing organisms are known as vectors. Influenza viruses

are spread by coughing and sneezing. Norovirus and rotavirus

, common causes of viral gastroenteritis

, are transmitted by the faecal-oral route

and are passed from person to person by contact, entering the body in food or water. HIV

is one of several viruses transmitted through sexual contact

and by exposure to infected blood. The range of host cells that a virus can infect is called its "host range". This can be narrow or, as when a virus is capable of infecting many species, broad.

Viral infections in animals provoke an immune response that usually eliminates the infecting virus. Immune responses can also be produced by vaccine

s, which confer an artificially acquired immunity

to the specific viral infection. However, some viruses including those causing AIDS

and viral hepatitis

evade these immune responses and result in chronic infections. Antibiotic

s have no effect on viruses, but several antiviral drug

s have been developed.

virus referring to poison

and other noxious substances, first used in English in 1392. Virulent, from Latin virulentus (poisonous), dates to 1400. A meaning of "agent that causes infectious disease" is first recorded in 1728, before the discovery of viruses by Dmitry Ivanovsky in 1892. The plural is viruses. The adjective viral dates to 1948. The term virion is also used to refer to a single infective viral particle.

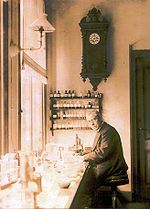

Louis Pasteur

Louis Pasteur

was unable to find a causative agent for rabies

and speculated about a pathogen too small to be detected using a microscope. In 1884, the French microbiologist

Charles Chamberland

invented a filter (known today as the Chamberland filter

or Chamberland-Pasteur filter) with pores smaller than bacteria. Thus, he could pass a solution containing bacteria through the filter and completely remove them from the solution. In 1892, the Russian biologist Dmitry Ivanovsky used this filter to study what is now known as the tobacco mosaic virus

. His experiments showed that crushed leaf extracts from infected tobacco plants remain infectious after filtration. Ivanovsky suggested the infection might be caused by a toxin

produced by bacteria, but did not pursue the idea. At the time it was thought that all infectious agents could be retained by filters and grown on a nutrient medium – this was part of the germ theory of disease. In 1898, the Dutch microbiologist Martinus Beijerinck

repeated the experiments and became convinced that the filtered solution contained a new form of infectious agent. He observed that the agent multiplied only in cells that were dividing, but as his experiments did not show that it was made of particles, he called it a contagium vivum fluidum (soluble living germ) and re-introduced the word virus. Beijerinck maintained that viruses were liquid in nature, a theory later discredited by Wendell Stanley, who proved they were particulate. In the same year Friedrich Loeffler and Frosch passed the first animal virus – agent of foot-and-mouth disease

(aphthovirus

) – through a similar filter.

In the early 20th century, the English bacteriologist Frederick Twort

discovered a group of viruses that infect bacteria, now called bacteriophages (or commonly phages), and the French-Canadian microbiologist Félix d'Herelle

described viruses that, when added to bacteria on agar

, would produce areas of dead bacteria. He accurately diluted a suspension of these viruses and discovered that the highest dilutions (lowest virus concentrations), rather than killing all the bacteria, formed discrete areas of dead organisms. Counting these areas and multiplying by the dilution factor allowed him to calculate the number of viruses in the original suspension. Phages were heralded as a potential treatment for diseases such as typhoid and cholera

, but their promise was forgotten with the development of penicillin

. The study of phages provided insights into the switching on and off of genes, and a useful mechanism for introducing foreign genes into bacteria.

By the end of the 19th century, viruses were defined in terms of their infectivity

, their ability to be filtered, and their requirement for living hosts. Viruses had been grown only in plants and animals. In 1906, Ross Granville Harrison

invented a method for growing tissue

in lymph

, and, in 1913, E. Steinhardt, C. Israeli, and R. A. Lambert used this method to grow vaccinia

virus in fragments of guinea pig corneal tissue. In 1928, H. B. Maitland and M. C. Maitland grew vaccinia virus in suspensions of minced hens' kidneys. Their method was not widely adopted until the 1950s, when poliovirus

was grown on a large scale for vaccine production.

Another breakthrough came in 1931, when the American pathologist Ernest William Goodpasture

grew influenza and several other viruses in fertilized chickens' eggs. In 1949, John F. Enders, Thomas Weller

, and Frederick Robbins grew polio virus in cultured human embryo cells, the first virus to be grown without using solid animal tissue or eggs. This work enabled Jonas Salk

to make an effective polio vaccine

.

The first images of viruses were obtained upon the invention of electron microscopy in 1931 by the German engineers Ernst Ruska

and Max Knoll

. In 1935, American biochemist and virologist Wendell Meredith Stanley

examined the tobacco mosaic virus and found it was mostly made of protein. A short time later, this virus was separated into protein and RNA parts.

The tobacco mosaic virus was the first to be crystal

lised and its structure could therefore be elucidated in detail. The first X-ray diffraction pictures of the crystallised virus were obtained by Bernal and Fankuchen in 1941. On the basis of her pictures, Rosalind Franklin

discovered the full DNA

structure of the virus in 1955. In the same year, Heinz Fraenkel-Conrat and Robley Williams showed that purified tobacco mosaic virus RNA and its coat protein can assemble by themselves to form functional viruses, suggesting that this simple mechanism was probably the means through which viruses were created within their host cells.

The second half of the 20th century was the golden age of virus discovery and most of the 2,000 recognised species of animal, plant, and bacterial viruses were discovered during these years. In 1957, equine arterivirus

and the cause of Bovine virus diarrhea

(a pestivirus

) were discovered. In 1963, the hepatitis B virus was discovered by Baruch Blumberg, and in 1965, Howard Temin described the first retrovirus

. Reverse transcriptase

, the key enzyme that retroviruses use to translate their RNA into DNA, was first described in 1970, independently by Howard Martin Temin

and David Baltimore

. In 1983 Luc Montagnier

's team at the Pasteur Institute

in France

, first isolated the retrovirus now called HIV.

have been used to compare the DNA or RNA of viruses and are a useful means of investigating how they arose. There are three main hypotheses that try to explain the origins of viruses:

Regressive hypothesis : Viruses may have once been small cells that parasitised

larger cells. Over time, genes not required by their parasitism were lost. The bacteria rickettsia

and chlamydia

are living cells that, like viruses, can reproduce only inside host cells. They lend support to this hypothesis, as their dependence on parasitism is likely to have caused the loss of genes that enabled them to survive outside a cell. This is also called the degeneracy hypothesis, or reduction hypothesis.

Cellular origin hypothesis : Some viruses may have evolved from bits of DNA or RNA that "escaped" from the genes of a larger organism. The escaped DNA could have come from plasmid

s (pieces of naked DNA that can move between cells) or transposons (molecules of DNA that replicate and move around to different positions within the genes of the cell). Once called "jumping genes", transposons are examples of mobile genetic elements

and could be the origin of some viruses. They were discovered in maize by Barbara McClintock

in 1950. This is sometimes called the vagrancy hypothesis, or the escape hypothesis.

Coevolution hypothesis : This is also called the virus-first hypothesis and proposes that viruses may have evolved from complex molecules of protein and nucleic acid

at the same time as cells first appeared on earth and would have been dependent on cellular life for billions of years. Viroids are molecules of RNA that are not classified as viruses because they lack a protein coat. However, they have characteristics that are common to several viruses and are often called subviral agents. Viroids are important pathogens of plants. They do not code for proteins but interact with the host cell and use the host machinery for their replication. The hepatitis delta virus of humans has an RNA genome similar to viroids but has a protein coat derived from hepatitis B virus and cannot produce one of its own. It is, therefore, a defective virus and cannot replicate without the help of hepatitis B virus. In similar manner, the virophage 'sputnik' is dependent on mimivirus

, which infects the protozoan Acanthamoeba castellanii. These viruses that are dependent on the presence of other virus species in the host cell are called satellites

and may represent evolutionary intermediates of viroids and viruses.

In the past, there were problems with all of these hypotheses: the regressive hypothesis did not explain why even the smallest of cellular parasites do not resemble viruses in any way. The escape hypothesis did not explain the complex capsids and other structures on virus particles. The virus-first hypothesis contravened the definition of viruses in that they require host cells. Viruses are now recognised as ancient and to have origins that pre-date the divergence of life into the three domains

. This discovery has led modern virologists to reconsider and re-evaluate these three classical hypotheses.

The evidence for an ancestral world of RNA cells and computer analysis of viral and host DNA sequences are giving a better understanding of the evolutionary relationships between different viruses and may help identify the ancestors of modern viruses. To date, such analyses have not proved which of these hypotheses is correct. However, it seems unlikely that all currently known viruses have a common ancestor, and viruses have probably arisen numerous times in the past by one or more mechanisms.

Prions are infectious protein molecules that do not contain DNA or RNA. They cause an infection in sheep called scrapie

and cattle bovine spongiform encephalopathy

("mad cow" disease). In humans they cause kuru

and Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. They are able to replicate because some proteins can exist in two different shapes and the prion changes the normal shape of a host protein into the prion shape. This starts a chain reaction where each prion protein converts many host proteins into more prions, and these new prions then go on to convert even more protein into prions. Although they are fundamentally different from viruses and viroids, their discovery gives credence to the idea that viruses could have evolved from self-replicating molecules.

, or organic structures that interact with living organisms. They have been described as "organisms at the edge of life", since they resemble organisms in that they possess genes and evolve by natural selection, and reproduce by creating multiple copies of themselves through self-assembly. Although they have genes, they do not have a cellular structure, which is often seen as the basic unit of life. Viruses do not have their own metabolism

, and require a host cell to make new products. They therefore cannot naturally reproduce outside a host cell – although bacterial species such as rickettsia

and chlamydia

are considered living organisms despite the same limitation. Accepted forms of life use cell division

to reproduce, whereas viruses spontaneously assemble within cells. They differ from autonomous growth of crystals

as they inherit genetic mutations while being subject to natural selection. Virus self-assembly within host cells has implications for the study of the origin of life, as it lends further credence to the hypothesis that life could have started as self-assembling organic molecules.

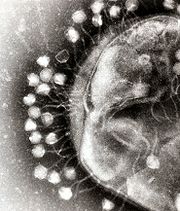

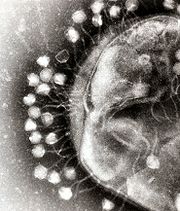

Viruses display a wide diversity of shapes and sizes, called morphologies

Viruses display a wide diversity of shapes and sizes, called morphologies

. Generally viruses are much smaller than bacteria. Most viruses that have been studied have a diameter between 20 and 300 nanometres. Some filoviruses have a total length of up to 1400 nm; their diameters are only about 80 nm. Most viruses cannot be seen with a light microscope so scanning and transmission electron microscope

s are used to visualise virions. To increase the contrast between viruses and the background, electron-dense "stains" are used. These are solutions of salts of heavy metals, such as tungsten

, that scatter the electrons from regions covered with the stain. When virions are coated with stain (positive staining), fine detail is obscured. Negative staining overcomes this problem by staining the background only.

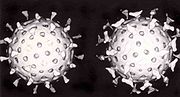

A complete virus particle, known as a virion, consists of nucleic acid surrounded by a protective coat of protein called a capsid

. These are formed from identical protein subunits called capsomeres

. Viruses can have a lipid

"envelope" derived from the host cell membrane

. The capsid is made from proteins encoded by the viral genome

and its shape serves as the basis for morphological distinction. Virally coded protein subunits will self-assemble to form a capsid, generally requiring the presence of the virus genome. Complex viruses code for proteins that assist in the construction of their capsid. Proteins associated with nucleic acid are known as nucleoprotein

s, and the association of viral capsid proteins with viral nucleic acid is called a nucleocapsid. The capsid and entire virus structure can be mechanically (physically) probed through atomic force microscopy. In general, there are four main morphological virus types:

Helical: These viruses are composed of a single type of capsomer stacked around a central axis to form a helical structure, which may have a central cavity, or hollow tube. This arrangement results in rod-shaped or filamentous virions: These can be short and highly rigid, or long and very flexible. The genetic material, in general, single-stranded RNA, but ssDNA in some cases, is bound into the protein helix by interactions between the negatively charged nucleic acid and positive charges on the protein. Overall, the length of a helical capsid is related to the length of the nucleic acid contained within it and the diameter is dependent on the size and arrangement of capsomers. The well-studied tobacco mosaic virus is an example of a helical virus.

Icosahedral: Most animal viruses are icosahedral or near-spherical with icosahedral symmetry. A regular icosahedron

is the optimum way of forming a closed shell from identical sub-units. The minimum number of identical capsomers required is twelve, each composed of five identical sub-units. Many viruses, such as rotavirus, have more than twelve capsomers and appear spherical but they retain this symmetry. Capsomers at the apices are surrounded by five other capsomers and are called pentons. Capsomers on the triangular faces are surrounded by six others and are called hexons. Hexons are essentially flat and pentons, which form the 12 vertices, are curved. The same protein may act as the subunit of both the pentamers and hexamers or they may be composed of different proteins.

Prolate: This is an isosahedron elongated along the fivefold axis and is a common arrangement of the heads of bacteriophages. Such a structure is composed of a cylinder with a cap at either end. The cylinder is composed of 10 triangles. The Q number, which can be can be any positive integer, specifies the number of triangles, composed of asymmetric subunits, that make up the 10 triangles of the cylinder. The caps are classified by the T number.

Envelope

: Some species of virus envelop themselves in a modified form of one of the cell membranes, either the outer membrane surrounding an infected host cell or internal membranes such as nuclear membrane or endoplasmic reticulum

, thus gaining an outer lipid bilayer known as a viral envelope. This membrane is studded with proteins coded for by the viral genome and host genome; the lipid membrane itself and any carbohydrates present originate entirely from the host. The influenza virus and HIV use this strategy. Most enveloped viruses are dependent on the envelope for their infectivity.

Complex: These viruses possess a capsid that is neither purely helical nor purely icosahedral, and that may possess extra structures such as protein tails or a complex outer wall. Some bacteriophages, such as Enterobacteria phage T4

, have a complex structure consisting of an icosahedral head bound to a helical tail, which may have a hexagonal base plate with protruding protein tail fibres. This tail structure acts like a molecular syringe, attaching to the bacterial host and then injecting the viral genome into the cell.

The poxviruses are large, complex viruses that have an unusual morphology. The viral genome is associated with proteins within a central disk structure known as a nucleoid. The nucleoid is surrounded by a membrane and two lateral bodies of unknown function. The virus has an outer envelope with a thick layer of protein studded over its surface. The whole virion is slightly pleiomorphic, ranging from ovoid to brick shape. Mimivirus is the largest characterised virus, with a capsid diameter of 400 nm. Protein filaments measuring 100 nm project from the surface. The capsid appears hexagonal under an electron microscope, therefore the capsid is probably icosahedral. In 2011, researchers discovered a larger virus on ocean floor of the coast of Las Cruces

, Chile

. Provisionally named Megavirus chilensis, it can be seen with a basic light microscope.

Some viruses that infect Archaea

have complex structures that are unrelated to any other form of virus, with a wide variety of unusual shapes, ranging from spindle-shaped structures, to viruses that resemble hooked rods, teardrops or even bottles. Other archaeal viruses resemble the tailed bacteriophages, and can have multiple tail structures.

An enormous variety of genomic structures can be seen among viral species; as a group they contain more structural genomic diversity than plants, animals, archaea, or bacteria. There are millions of different types of viruses, although only about 5,000 of them have been described in detail.

A virus has either DNA or RNA genes and is called a DNA virus or a RNA virus respectively. The vast majority of viruses have RNA genomes. Plant viruses tend to have single-stranded RNA genomes and bacteriophages tend to have double-stranded DNA genomes.

Viral genomes are circular, as in the polyomavirus

es, or linear, as in the adenoviruses

. The type of nucleic acid is irrelevant to the shape of the genome. Among RNA viruses and certain DNA viruses, the genome is often divided up into separate parts, in which case it is called segmented. For RNA viruses, each segment often codes for only one protein and they are usually found together in one capsid. However, all segments are not required to be in the same virion for the virus to be infectious, as demonstrated by brome mosaic virus

and several other plant viruses.

A viral genome, irrespective of nucleic acid type, is almost always either single-stranded or double-stranded. Single-stranded genomes consist of an unpaired nucleic acid, analogous to one-half of a ladder split down the middle. Double-stranded genomes consist of two complementary paired nucleic acids, analogous to a ladder. The virus particles of some virus families, such as those belonging to the Hepadnaviridae

, contain a genome that is partially double-stranded and partially single-stranded.

For most viruses with RNA genomes and some with single-stranded DNA genomes, the single strands are said to be either positive-sense (called the plus-strand) or negative-sense (called the minus-strand), depending on whether or not they are complementary to the viral messenger RNA

(mRNA). Positive-sense viral RNA is in the same sense as viral mRNA and thus at least a part of it can be immediately translated

by the host cell. Negative-sense viral RNA is complementary to mRNA and thus must be converted to positive-sense RNA by an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase

before translation. DNA nomenclature for viruses with single-sense genomic ssDNA is similar to RNA nomenclature, in that the coding strand for the viral mRNA is complementary to it (−), and the non-coding strand is a copy of it (+). However, several types of ssDNA and ssRNA viruses have genomes that are ambisense in that transcription can occur off both strands in a double-stranded replicative intermediate. Examples include geminivirus

es, which are ssDNA plant viruses and arenavirus

es, which are ssRNA viruses of animals.

Genome size varies greatly between species. The smallest viral genomes – the ssDNA circoviruses, family Circoviridae

– code for only two proteins and have a genome size of only 2 kilobases; the largest – mimivirus

es – have genome sizes of over 1.2 megabases and code for over one thousand proteins. RNA viruses generally have smaller genome sizes than DNA viruses because of a higher error-rate when replicating, and have a maximum upper size limit. Beyond this limit, errors in the genome when replicating render the virus useless or uncompetitive. To compensate for this, RNA viruses often have segmented genomes – the genome is split into smaller molecules – thus reducing the chance that an error in a single-component genome will incapacitate the entire genome. In contrast, DNA viruses generally have larger genomes because of the high fidelity of their replication enzymes. Single-strand DNA viruses are an exception to this rule, however, as mutation rates for these genomes can approach the extreme of the ssRNA virus case.

Viruses undergo genetic change by several mechanisms. These include a process called genetic drift

Viruses undergo genetic change by several mechanisms. These include a process called genetic drift

where individual bases in the DNA or RNA mutate to other bases. Most of these point mutations are "silent" – they do not change the protein that the gene encodes – but others can confer evolutionary advantages such as resistance to antiviral drugs. Antigenic shift

occurs when there is a major change in the genome

of the virus. This can be a result of recombination

or reassortment

. When this happens with influenza viruses, pandemics might result. RNA viruses often exist as quasispecies or swarms of viruses of the same species but with slightly different genome nucleoside sequences. Such quasispecies are a prime target for natural selection.

Segmented genomes confer evolutionary advantages; different strains of a virus with a segmented genome can shuffle and combine genes and produce progeny viruses or (offspring) that have unique characteristics. This is called reassortment or viral sex.

Genetic recombination

is the process by which a strand of DNA is broken and then joined to the end of a different DNA molecule. This can occur when viruses infect cells simultaneously and studies of viral evolution have shown that recombination has been rampant in the species studied. Recombination is common to both RNA and DNA viruses.

The life cycle of viruses

differs greatly between species but there are six basic stages in the life cycle of viruses:

The genetic material within virus particles, and the method by which the material is replicated, varies considerably between different types of viruses.

DNA viruses : The genome replication of most DNA viruses takes place in the cell's nucleus

. If the cell has the appropriate receptor on its surface, these viruses enter the cell sometimes by direct fusion with the cell membrane (e.g. herpesviruses) or – more usually – by receptor-mediated endocytosis. Most DNA viruses are entirely dependent on the host cell's DNA and RNA synthesising machinery, and RNA processing machinery; however, viruses with larger genomes may encode much of this machinery themselves. In eukaryotes the viral genome must cross the cell's nuclear membrane to access this machinery, while in bacteria it need only enter the cell.

RNA viruses: Replication usually takes place in the cytoplasm

. RNA viruses can be placed into four different groups depending on their modes of replication. The polarity

(whether or not it can be used directly by ribosomes to make proteins) of single-stranded RNA viruses largely determines the replicative mechanism; the other major criterion is whether the genetic material is single-stranded or double-stranded. All RNA viruses use their own RNA replicase enzymes to create copies of their genomes.

Reverse transcribing viruses: These have ssRNA (Retroviridae, Metaviridae

, Pseudoviridae

) or dsDNA (Caulimoviridae

, and Hepadnaviridae

) in their particles. Reverse transcribing viruses with RNA genomes (retroviruses), use a DNA intermediate to replicate, whereas those with DNA genomes (pararetroviruses) use an RNA intermediate during genome replication. Both types use a reverse transcriptase

, or RNA-dependent DNA polymerase enzyme, to carry out the nucleic acid conversion. Retrovirus

es integrate the DNA produced by reverse transcription into the host genome as a provirus as a part of the replication process; pararetroviruses do not, although integrated genome copies of especially plant pararetroviruses can give rise to infectious virus. They are susceptible to antiviral drug

s that inhibit the reverse transcriptase enzyme, e.g. zidovudine

and lamivudine

. An example of the first type is HIV, which is a retrovirus. Examples of the second type are the Hepadnaviridae

, which includes Hepatitis B virus.

s. Most virus infections eventually result in the death of the host cell. The causes of death include cell lysis, alterations to the cell's surface membrane and apoptosis

. Often cell death is caused by cessation of its normal activities because of suppression by virus-specific proteins, not all of which are components of the virus particle.

Some viruses cause no apparent changes to the infected cell. Cells in which the virus is latent

and inactive show few signs of infection and often function normally. This causes persistent infections and the virus is often dormant for many months or years. This is often the case with herpes viruses

. Some viruses, such as Epstein-Barr virus

, can cause cells to proliferate without causing malignancy, while others, such as papillomavirus

es, are established causes of cancer.

and fungi

. However, different types of viruses can infect only a limited range of hosts and many are species-specific. Some, such as smallpox virus for example, can infect only one species – in this case humans, and are said to have a narrow host range. Other viruses, such as rabies virus, can infect different species of mammals and are said to have a broad range. The viruses that infect plants are harmless to animals, and most viruses that infect other animals are harmless to humans. The host range of some bacteriophages is limited to a single strain

of bacteria and they can be used to trace the source of outbreaks of infections by a method called phage typing

.

were the first to develop a means of virus classification, based on the Linnaean

hierarchical system. This system bases classification on phylum

, class

, order

, family

, genus

, and species

. Viruses were grouped according to their shared properties (not those of their hosts) and the type of nucleic acid forming their genomes. Later the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses

was formed. However, viruses are not classified on the basis of phylum or class, as their small genome size and high rate of mutation makes it difficult to determine their ancestry beyond Order. As such, the Baltimore Classification is used to supplement the more traditional hierarchy.

(ICTV) developed the current classification system and wrote guidelines that put a greater weight on certain virus properties to maintain family uniformity. A unified taxonomy (a universal system for classifying viruses) has been established. The 7th lCTV Report formalised for the first time the concept of the virus species as the lowest taxon (group) in a branching hierarchy of viral taxa. However, at present only a small part of the total diversity of viruses has been studied, with analyses of samples from humans finding that about 20% of the virus sequences recovered have not been seen before, and samples from the environment, such as from seawater and ocean sediments, finding that the large majority of sequences are completely novel.

The general taxonomic structure is as follows:

In the current (2010) ICTV taxonomy, six orders have been established, the Caudovirales, Herpesvirales, Mononegavirales, Nidovirales, Picornavirales and Tymovirales. A seventh order Ligamenvirales has also been proposed. The committee does not formally distinguish between subspecies

, strains

, and isolates

. In total there are 6 orders, 87 families, 19 subfamilies, 348 genera, 2,885 species and about 3,000 types yet unclassified.

The Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prize

-winning biologist David Baltimore

devised the Baltimore classification system. The ICTV classification system is used in conjunction with the Baltimore classification system in modern virus classification.

The Baltimore classification of viruses is based on the mechanism of mRNA production. Viruses must generate mRNAs from their genomes to produce proteins and replicate themselves, but different mechanisms are used to achieve this in each virus family. Viral genomes may be single-stranded (ss) or double-stranded (ds), RNA or DNA, and may or may not use reverse transcriptase

(RT). Additionally, ssRNA viruses may be either sense

(+) or antisense (−). This classification places viruses into seven groups:

As an example of viral classification, the chicken pox virus, varicella zoster (VZV), belongs to the order Herpesvirales, family Herpesviridae

, subfamily Alphaherpesvirinae

, and genus Varicellovirus

. VZV is in Group I of the Baltimore Classification because it is a dsDNA virus that does not use reverse transcriptase.

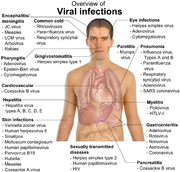

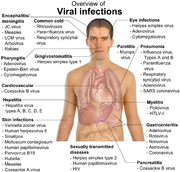

Examples of common human diseases caused by viruses include the common cold

Examples of common human diseases caused by viruses include the common cold

, influenza, chickenpox

and cold sores. Many serious diseases such as ebola

, AIDS

, avian influenza and SARS are caused by viruses. The relative ability of viruses to cause disease is described in terms of virulence

. Other diseases are under investigation as to whether they too have a virus as the causative agent, such as the possible connection between human herpes virus six

(HHV6) and neurological diseases such as multiple sclerosis

and chronic fatigue syndrome

. There is controversy over whether the borna virus, previously thought to cause neurological

diseases in horses, could be responsible for psychiatric

illnesses in humans.

Viruses have different mechanisms by which they produce disease in an organism, which largely depends on the viral species. Mechanisms at the cellular level primarily include cell lysis, the breaking open and subsequent death of the cell. In multicellular organism

s, if enough cells die, the whole organism will start to suffer the effects. Although viruses cause disruption of healthy homeostasis

, resulting in disease, they may exist relatively harmlessly within an organism. An example would include the ability of the herpes simplex virus

, which causes cold sores, to remain in a dormant state within the human body. This is called latency and is a characteristic of the herpes viruses including Epstein-Barr virus, which causes glandular fever, and varicella zoster virus, which causes chickenpox and shingles. Most people have been infected with at least one of these types of herpes virus. However, these latent viruses might sometimes be beneficial, as the presence of the virus can increase immunity against bacterial pathogens, such as Yersinia pestis

.

Some viruses can cause life-long or chronic infections, where the viruses continue to replicate in the body despite the host's defence mechanisms. This is common in hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections. People chronically infected are known as carriers, as they serve as reservoirs of infectious virus. In populations with a high proportion of carriers, the disease is said to be endemic

.

is the branch of medical science that deals with the transmission and control of virus infections in humans. Transmission of viruses can be vertical, that is from mother to child, or horizontal, which means from person to person. Examples of vertical transmission

include hepatitis B virus and HIV where the baby is born already infected with the virus. Another, more rare, example is the varicella zoster virus, which, although causing relatively mild infections in humans, can be fatal to the foetus and new-born baby.

Horizontal transmission

is the most common mechanism of spread of viruses in populations. Transmission can occur when: body fluids are exchanged during sexual activity, e.g., HIV; blood is exchanged by contaminated transfusion or needle sharing, e.g., hepatitis C; a child is born to an infected mother, e.g., hepatitis B; exchange of saliva by mouth, e.g., Epstein-Barr virus; contaminated food or water is ingested, e.g., norovirus; aerosol

s containing virions are inhaled, e.g., influenza virus; and insect vectors such as mosquitoes penetrate the skin of a host, e.g., dengue.

The rate or speed of transmission of viral infections depends on factors that include population density

, the number of susceptible individuals, (i.e., those not immune), the quality of healthcare and the weather.

Epidemiology is used to break the chain of infection in populations during outbreaks of viral diseases. Control measures are used that are based on knowledge of how the virus is transmitted. It is important to find the source, or sources, of the outbreak and to identify the virus. Once the virus has been identified, the chain of transmission can sometimes be broken by vaccines. When vaccines are not available sanitation and disinfection can be effective. Often infected people are isolated from the rest of the community and those that have been exposed to the virus placed in quarantine

. To control the outbreak of foot and mouth disease in cattle in Britain in 2001, thousands of cattle were slaughtered. Most viral infections of humans and other animals have incubation period

s during which the infection causes no signs or symptoms. Incubation periods for viral diseases range from a few days to weeks but are known for most infections. Somewhat overlapping, but mainly following the incubation period, there is a period of communicability; a time when an infected individual or animal is contagious and can infect another person or animal. This too is known for many viral infections and knowledge the length of both periods is important in the control of outbreaks. When outbreaks cause an unusually high proportion of cases in a population, community or region they are called epidemic

s. If outbreaks spread worldwide they are called pandemic

s.

Native American

Native American

populations were devastated by contagious diseases, in particular, smallpox

, brought to the Americas by European colonists. It is unclear how many Native Americans were killed by foreign diseases after the arrival of Columbus in the Americas, but the numbers have been estimated to be close to 70% of the indigenous population. The damage done by this disease significantly aided European attempts to displace and conquer the native population.

A pandemic

is a worldwide epidemic. The 1918 flu pandemic, commonly referred to as the Spanish flu, was a category 5

influenza pandemic caused by an unusually severe and deadly influenza A virus. The victims were often healthy young adults, in contrast to most influenza outbreaks, which predominantly affect juvenile, elderly, or otherwise-weakened patients.

The Spanish flu pandemic lasted from 1918 to 1919. Older estimates say it killed 40–50 million people, while more recent research suggests that it may have killed as many as 100 million people, or 5% of the world's population in 1918.

Most researchers believe that HIV originated in sub-Saharan Africa

during the 20th century; it is now a pandemic

, with an estimated 38.6 million people now living with the disease worldwide. The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS

(UNAIDS) and the World Health Organization

(WHO) estimate that AIDS has killed more than 25 million people since it was first recognised on June 5, 1981, making it one of the most destructive epidemic

s in recorded history. In 2007 there were 2.7 million new HIV infections and 2 million HIV-related deaths.

Several highly lethal viral pathogens are members of the Filoviridae

Several highly lethal viral pathogens are members of the Filoviridae

. Filoviruses are filament-like viruses that cause viral hemorrhagic fever

, and include the ebola

and marburg virus

es. The Marburg virus attracted widespread press attention in April 2005 for an outbreak in Angola

. Beginning in October 2004 and continuing into 2005, the outbreak was the world's worst epidemic of any kind of viral hemorrhagic fever.

in humans and other species. Viral cancers occur only in a minority of infected persons (or animals). Cancer viruses come from a range of virus families, including both RNA and DNA viruses, and so there is no single type of "oncovirus

" (an obsolete term originally used for acutely transforming retroviruses). The development of cancer is determined by a variety of factors such as host immunity and mutations in the host. Viruses accepted to cause human cancers include some genotypes of human papillomavirus

, hepatitis B virus

, hepatitis C virus

, Epstein-Barr virus

, Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus

and human T-lymphotropic virus

. The most recently discovered human cancer virus is a polyomavirus (Merkel cell polyomavirus

) that causes most cases of a rare form of skin cancer called Merkel cell carcinoma

.

Hepatitis viruses can develop into a chronic viral infection that leads to liver cancer

. Infection by human T-lymphotropic virus can lead to tropical spastic paraparesis

and adult T-cell leukemia

. Human papillomaviruses are an established cause of cancers of cervix

, skin, anus

, and penis

. Within the Herpesviridae

, Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus

causes Kaposi's sarcoma

and body cavity lymphoma, and Epstein–Barr virus causes Burkitt's lymphoma

, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, B

lymphoproliferative disorder

, and nasopharyngeal carcinoma

. Merkel cell polyomavirus closely related to SV40

and mouse polyomaviruses that have been used as animal models for cancer viruses for over 50 years.

. This comprises cells and other mechanisms that defend the host from infection in a non-specific manner. This means that the cells of the innate system recognise, and respond to, pathogens in a generic way, but, unlike the adaptive immune system

, it does not confer long-lasting or protective immunity to the host.

RNA interference

is an important innate defence against viruses. Many viruses have a replication strategy that involves double-stranded RNA (dsRNA). When such a virus infects a cell, it releases its RNA molecule or molecules, which immediately bind to a protein complex called dicer

that cuts the RNA into smaller pieces. A biochemical pathway called the RISC complex is activated, which degrades the viral mRNA and the cell survives the infection. Rotaviruses avoid this mechanism by not uncoating fully inside the cell and by releasing newly produced mRNA through pores in the particle's inner capsid. The genomic dsRNA remains protected inside the core of the virion.

When the adaptive immune system

of a vertebrate

encounters a virus, it produces specific antibodies that bind to the virus and render it non-infectious. This is called humoral immunity

. Two types of antibodies are important. The first, called IgM, is highly effective at neutralizing viruses but is produced by the cells of the immune system only for a few weeks. The second, called IgG, is produced indefinitely. The presence of IgM in the blood of the host is used to test for acute infection, whereas IgG indicates an infection sometime in the past. IgG antibody is measured when tests for immunity

are carried out.

A second defence of vertebrates against viruses is called cell-mediated immunity

A second defence of vertebrates against viruses is called cell-mediated immunity

and involves immune cells known as T cells. The body's cells constantly display short fragments of their proteins on the cell's surface, and, if a T cell recognises a suspicious viral fragment there, the host cell is destroyed by killer T cells and the virus-specific T-cells proliferate. Cells such as the macrophage

are specialists at this antigen presentation

. The production of interferon

is an important host defence mechanism. This is a hormone produced by the body when viruses are present. Its role in immunity is complex; it eventually stops the viruses from reproducing by killing the infected cell and its close neighbours.

Not all virus infections produce a protective immune response in this way. HIV

evades the immune system by constantly changing the amino acid sequence of the proteins on the surface of the virion. These persistent viruses evade immune control by sequestration, blockade of antigen presentation

, cytokine

resistance, evasion of natural killer cell

activities, escape from apoptosis

, and antigenic shift. Other viruses, called neurotropic virus

es, are disseminated by neural spread where the immune system may be unable to reach them.

s to provide immunity to infection, and antiviral drugs that selectively interfere with viral replication.

is a cheap and effective way of preventing infections by viruses. Vaccines were used to prevent viral infections long before the discovery of the actual viruses. Their use has resulted in a dramatic decline in morbidity (illness) and mortality (death) associated with viral infections such as polio, measles

, mumps

and rubella

. Smallpox infections have been eradicated. Vaccines are available to prevent over thirteen viral infections of humans, and more are used to prevent viral infections of animals. Vaccines can consist of live-attenuated or killed viruses, or viral proteins (antigens). Live vaccines contain weakened forms of the virus, which do not cause the disease but, nonetheless, confer immunity. Such viruses are called attenuated. Live vaccines can be dangerous when given to people with a weak immunity, (who are described as immunocompromised), because in these people, the weakened virus can cause the original disease. Biotechnology and genetic engineering techniques are used to produce subunit vaccines. These vaccines use only the capsid proteins of the virus. Hepatitis B vaccine is an example of this type of vaccine. Subunit vaccines are safe for immunocompromised patients because they cannot cause the disease.

The yellow fever virus vaccine, a live-attenuated strain called 17D, is probably the safest and most effective vaccine ever generated.

, (fake DNA building-blocks), which viruses mistakenly incorporate into their genomes during replication. The life-cycle of the virus is then halted because the newly synthesised DNA is inactive. This is because these analogues lack the hydroxyl groups, which, along with phosphorus

atoms, link together to form the strong "backbone" of the DNA molecule. This is called DNA chain termination

. Examples of nucleoside analogues are aciclovir

for Herpes simplex virus infections and lamivudine

for HIV and Hepatitis B virus infections. Aciclovir

is one of the oldest and most frequently prescribed antiviral drugs.

Other antiviral drugs in use target different stages of the viral life cycle. HIV is dependent on a proteolytic enzyme called the HIV-1 protease

for it to become fully infectious. There is a large class of drugs called protease inhibitors that inactivate this enzyme.

Hepatitis C is caused by an RNA virus. In 80% of people infected, the disease is chronic, and without treatment, they are infected

for the remainder of their lives. However, there is now an effective treatment that uses the nucleoside analogue drug ribavirin

combined with interferon

. The treatment of chronic carriers

of the hepatitis B virus by using a similar strategy using lamivudine has been developed.

, can only replicate within cells that have already been infected by another virus. Viruses are important pathogens of livestock. Diseases such as Foot and Mouth Disease and bluetongue are caused by viruses. Companion animals such as cats, dogs, and horses, if not vaccinated, are susceptible to serious viral infections. Canine parvovirus

is caused by a small DNA virus and infections are often fatal in pups. Like all invertebrates, the honey bee is susceptible to many viral infections. Fortunately, most viruses co-exist harmlessly in their host and cause no signs or symptoms of disease.

There are many types of plant virus

There are many types of plant virus

, but often they cause only a loss of yield

, and it is not economically viable to try to control them. Plant viruses are often spread from plant to plant by organism

s, known as vectors. These are normally insects, but some fungi, nematode worms

, and single-celled organisms

have been shown to be vectors. When control of plant virus infections is considered economical, for perennial fruits, for example, efforts are concentrated on killing the vectors and removing alternate hosts such as weeds. Plant viruses are harmless to humans and other animals because they can reproduce only in living plant cells.

Plants have elaborate and effective defence mechanisms against viruses. One of the most effective is the presence of so-called resistance (R) genes. Each R gene confers resistance to a particular virus by triggering localised areas of cell death around the infected cell, which can often be seen with the unaided eye as large spots. This stops the infection from spreading. RNA interference is also an effective defence in plants. When they are infected, plants often produce natural disinfectants that kill viruses, such as salicylic acid

, nitric oxide

, and reactive oxygen molecules

.

Plant virus particles or virus-like particles (VLPs) have applications in both biotechnology

and nanotechnology

. The capsids of most plant viruses are simple and robust structures and can be produced in large quantities either by the infection of plants or by expression in a variety of heterologous systems. Plant virus particles can be modified genetically and chemically to encapsulate foreign material and can be incorporated into supramolecular structures for use in biotechnology.

Bacteriophage

Bacteriophage

s are a common and diverse group of viruses and are the most abundant form of biological entity in aquatic environments – there are up to ten times more of these viruses in the oceans than there are bacteria, reaching levels of 250,000,000 bacteriophages per millilitre of seawater. These viruses infect specific bacteria by binding to surface receptor molecules

and then entering the cell. Within a short amount of time, in some cases just minutes, bacterial polymerase

starts translating viral mRNA into protein. These proteins go on to become either new virions within the cell, helper proteins, which help assembly of new virions, or proteins involved in cell lysis. Viral enzymes aid in the breakdown of the cell membrane, and, in the case of the T4 phage, in just over twenty minutes after injection over three hundred phages could be released.

The major way bacteria defend themselves from bacteriophages is by producing enzymes that destroy foreign DNA. These enzymes, called restriction endonucleases, cut up the viral DNA that bacteriophages inject into bacterial cells. Bacteria also contain a system that uses CRISPR

sequences to retain fragments of the genomes of viruses that the bacteria have come into contact with in the past, which allows them to block the virus's replication through a form of RNA interference

. This genetic system provides bacteria with acquired immunity

to infection.

: these are double-stranded DNA viruses with unusual and sometimes unique shapes. These viruses have been studied in most detail in the thermophilic archaea, particularly the orders Sulfolobales

and Thermoproteales

. Defences against these viruses may involve RNA interference

from repetitive DNA sequences within archaean genomes that are related to the genes of the viruses.

in the marine environment. The organic molecules released from the bacterial cells by the viruses stimulates fresh bacterial and algal growth.

Microorganisms constitute more than 90% of the biomass in the sea. It is estimated that viruses kill approximately 20% of this biomass each day and that there are 15 times as many viruses in the oceans as there are bacteria and archaea

. Viruses are the main agents responsible for the rapid destruction of harmful algal bloom

s, which often kill other marine life.

The number of viruses in the oceans decreases further offshore and deeper into the water, where there are fewer host organisms.

The effects of marine viruses are far-reaching; by increasing the amount of photosynthesis

in the oceans, viruses are indirectly responsible for reducing the amount of carbon dioxide

in the atmosphere by approximately 3 gigatonnes of carbon per year.

Like any organism, marine mammal

s are susceptible to viral infections. In 1988 and 2002, thousands of harbour seals were killed in Europe by phocine distemper virus

. Many other viruses, including caliciviruses, herpesviruses, adenoviruses and parvovirus

es, circulate in marine mammal populations.

and drives evolution. It is thought that viruses played a central role in the early evolution, before the diversification of bacteria, archaea and eukaryotes and at the time of the last universal common ancestor

of life on Earth. Viruses are still one of the largest reservoirs of unexplored genetic diversity

on Earth.

Viruses are important to the study of molecular

Viruses are important to the study of molecular

and cellular biology as they provide simple systems that can be used to manipulate and investigate the functions of cells. The study and use of viruses have provided valuable information about aspects of cell biology. For example, viruses have been useful in the study of genetics

and helped our understanding of the basic mechanisms of molecular genetics

, such as DNA replication

, transcription

, RNA processing, translation

, protein

transport, and immunology

.

Geneticists

often use viruses as vectors

to introduce genes into cells that they are studying. This is useful for making the cell produce a foreign substance, or to study the effect of introducing a new gene into the genome. In similar fashion, virotherapy

uses viruses as vectors to treat various diseases, as they can specifically target cells and DNA. It shows promising use in the treatment of cancer and in gene therapy

. Eastern European scientists have used phage therapy

as an alternative to antibiotics for some time, and interest in this approach is increasing, because of the high level of antibiotic resistance

now found in some pathogenic bacteria.

Expression of heterologous protein

s by viruses is the basis of several manufacturing processes that are currently being used for the production of various proteins such as vaccine antigen

s and antibodies. Industrial processes have been recently developed using viral vectors and a number of pharmaceutical proteins are currently in pre-clinical and clinical trials.

Their surface carries specific tools designed to cross the barriers of their host cells. The size and shape of viruses, and the number and nature of the functional groups on their surface, is precisely defined. As such, viruses are commonly used in materials science as scaffolds for covalently linked surface modifications. A particular quality of viruses is that they can be tailored by directed evolution. The powerful techniques developed by life sciences are becoming the basis of engineering approaches towards nanomaterials, opening a wide range of applications far beyond biology and medicine.

Because of their size, shape, and well-defined chemical structures, viruses have been used as templates for organizing materials on the nanoscale. Recent examples include work at the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington, DC, using Cowpea Mosaic Virus (CPMV) particles to amplify signals in DNA microarray

based sensors. In this application, the virus particles separate the fluorescent

dye

s used for signalling to prevent the formation of non-fluorescent dimers that act as quenchers

. Another example is the use of CPMV as a nanoscale breadboard for molecular electronics.

cells are available. Currently, the full-length genome sequences of 2408 different viruses (including smallpox) are publicly available at an online database, maintained by the National Institute of Health.

s in human societies has led to the concern that viruses could be weaponised for biological warfare

. Further concern was raised by the successful recreation of the infamous 1918 influenza virus in a laboratory. The smallpox

virus devastated numerous societies throughout history before its eradication. There are officially only two centers in the world that keep stocks of smallpox virus – the Russian Vector laboratory, and the United States Centers for Disease Control. But fears that it may be used as a weapon are not totally unfounded; the vaccine for smallpox has sometimes severe side-effects – during the last years before the eradication of smallpox disease more people became seriously ill as a result of vaccination than did people from smallpox – and smallpox vaccination is no longer universally practiced. Thus, much of the modern human population has almost no established resistance to smallpox.

Pathogen

A pathogen gignomai "I give birth to") or infectious agent — colloquially, a germ — is a microbe or microorganism such as a virus, bacterium, prion, or fungus that causes disease in its animal or plant host...

that can replicate only inside the living cells of organisms. Viruses infect all types of organisms, from animal

Animal

Animals are a major group of multicellular, eukaryotic organisms of the kingdom Animalia or Metazoa. Their body plan eventually becomes fixed as they develop, although some undergo a process of metamorphosis later on in their life. Most animals are motile, meaning they can move spontaneously and...

s and plant

Plant

Plants are living organisms belonging to the kingdom Plantae. Precise definitions of the kingdom vary, but as the term is used here, plants include familiar organisms such as trees, flowers, herbs, bushes, grasses, vines, ferns, mosses, and green algae. The group is also called green plants or...

s to bacteria

Bacteria

Bacteria are a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria have a wide range of shapes, ranging from spheres to rods and spirals...

and archaea

Archaea

The Archaea are a group of single-celled microorganisms. A single individual or species from this domain is called an archaeon...

. Since Dmitri Ivanovsky's 1892 article describing a non-bacterial pathogen infecting tobacco plants, and the discovery of the tobacco mosaic virus

Tobacco mosaic virus

Tobacco mosaic virus is a positive-sense single stranded RNA virus that infects plants, especially tobacco and other members of the family Solanaceae. The infection causes characteristic patterns on the leaves . TMV was the first virus to be discovered...

by Martinus Beijerinck

Martinus Beijerinck

Martinus Willem Beijerinck was a Dutch microbiologist and botanist. Born in Amsterdam, Beijerinck studied at the Technical School of Delft, where he was awarded the degree of Chemical Engineer in 1872. He obtained his Doctor of Science degree from the University of Leiden in 1877...

in 1898, about 5,000 viruses have been described in detail, although there are millions of different types. Viruses are found in almost every ecosystem

Ecosystem

An ecosystem is a biological environment consisting of all the organisms living in a particular area, as well as all the nonliving , physical components of the environment with which the organisms interact, such as air, soil, water and sunlight....

on Earth and are the most abundant type of biological entity. The study of viruses is known as virology

Virology

Virology is the study of viruses and virus-like agents: their structure, classification and evolution, their ways to infect and exploit cells for virus reproduction, the diseases they cause, the techniques to isolate and culture them, and their use in research and therapy...

, a sub-speciality of microbiology

Microbiology

Microbiology is the study of microorganisms, which are defined as any microscopic organism that comprises either a single cell , cell clusters or no cell at all . This includes eukaryotes, such as fungi and protists, and prokaryotes...

.

Virus particles (known as virions) consist of two or three parts: the genetic material made from either DNA

DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid is a nucleic acid that contains the genetic instructions used in the development and functioning of all known living organisms . The DNA segments that carry this genetic information are called genes, but other DNA sequences have structural purposes, or are involved in...

or RNA

RNA

Ribonucleic acid , or RNA, is one of the three major macromolecules that are essential for all known forms of life....

, long molecule

Molecule

A molecule is an electrically neutral group of at least two atoms held together by covalent chemical bonds. Molecules are distinguished from ions by their electrical charge...

s that carry genetic information; a protein

Protein

Proteins are biochemical compounds consisting of one or more polypeptides typically folded into a globular or fibrous form, facilitating a biological function. A polypeptide is a single linear polymer chain of amino acids bonded together by peptide bonds between the carboxyl and amino groups of...

coat that protects these genes; and in some cases an envelope

Viral envelope

Many viruses have viral envelopes covering their protein capsids. The envelopes typically are derived from portions of the host cell membranes , but include some viral glycoproteins. Functionally, viral envelopes are used to help viruses enter host cells...

of lipid

Lipid

Lipids constitute a broad group of naturally occurring molecules that include fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins , monoglycerides, diglycerides, triglycerides, phospholipids, and others...

s that surrounds the protein coat when they are outside a cell. The shapes of viruses range from simple helical

Helix

A helix is a type of smooth space curve, i.e. a curve in three-dimensional space. It has the property that the tangent line at any point makes a constant angle with a fixed line called the axis. Examples of helixes are coil springs and the handrails of spiral staircases. A "filled-in" helix – for...

and icosahedral

Icosahedron

In geometry, an icosahedron is a regular polyhedron with 20 identical equilateral triangular faces, 30 edges and 12 vertices. It is one of the five Platonic solids....

forms to more complex structures. The average virus is about one one-hundredth the size of the average bacterium. Most viruses are too small to be seen directly with a light microscope

Optical microscope

The optical microscope, often referred to as the "light microscope", is a type of microscope which uses visible light and a system of lenses to magnify images of small samples. Optical microscopes are the oldest design of microscope and were possibly designed in their present compound form in the...

.

The origins of viruses in the evolutionary history of life

Evolutionary history of life

The evolutionary history of life on Earth traces the processes by which living and fossil organisms have evolved since life on Earth first originated until the present day. Earth formed about 4.5 Ga and life appeared on its surface within one billion years...

are unclear: some may have evolved

Evolution

Evolution is any change across successive generations in the heritable characteristics of biological populations. Evolutionary processes give rise to diversity at every level of biological organisation, including species, individual organisms and molecules such as DNA and proteins.Life on Earth...

from plasmid

Plasmid

In microbiology and genetics, a plasmid is a DNA molecule that is separate from, and can replicate independently of, the chromosomal DNA. They are double-stranded and, in many cases, circular...

s – pieces of DNA that can move between cells – while others may have evolved from bacteria. In evolution, viruses are an important means of horizontal gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer , also lateral gene transfer , is any process in which an organism incorporates genetic material from another organism without being the offspring of that organism...

, which increases genetic diversity

Genetic diversity

Genetic diversity, the level of biodiversity, refers to the total number of genetic characteristics in the genetic makeup of a species. It is distinguished from genetic variability, which describes the tendency of genetic characteristics to vary....

.

Viruses spread in many ways; viruses in plant

Plant

Plants are living organisms belonging to the kingdom Plantae. Precise definitions of the kingdom vary, but as the term is used here, plants include familiar organisms such as trees, flowers, herbs, bushes, grasses, vines, ferns, mosses, and green algae. The group is also called green plants or...

s are often transmitted from plant to plant by insect

Insect

Insects are a class of living creatures within the arthropods that have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body , three pairs of jointed legs, compound eyes, and two antennae...

s that feed on the sap

Sap

Sap may refer to:* Plant sap, the fluid transported in xylem cells or phloem sieve tube elements of a plant* Sap , a village in the Dunajská Streda District of Slovakia...

of plants, such as aphid

Aphid

Aphids, also known as plant lice and in Britain and the Commonwealth as greenflies, blackflies or whiteflies, are small sap sucking insects, and members of the superfamily Aphidoidea. Aphids are among the most destructive insect pests on cultivated plants in temperate regions...

s; viruses in animal

Animal

Animals are a major group of multicellular, eukaryotic organisms of the kingdom Animalia or Metazoa. Their body plan eventually becomes fixed as they develop, although some undergo a process of metamorphosis later on in their life. Most animals are motile, meaning they can move spontaneously and...

s can be carried by blood-sucking

Hematophagy

Hematophagy is the practice of certain animals of feeding on blood...

insects. These disease-bearing organisms are known as vectors. Influenza viruses

Influenza

Influenza, commonly referred to as the flu, is an infectious disease caused by RNA viruses of the family Orthomyxoviridae , that affects birds and mammals...

are spread by coughing and sneezing. Norovirus and rotavirus

Rotavirus

Rotavirus is the most common cause of severe diarrhoea among infants and young children, and is one of several viruses that cause infections often called stomach flu, despite having no relation to influenza. It is a genus of double-stranded RNA virus in the family Reoviridae. By the age of five,...

, common causes of viral gastroenteritis

Gastroenteritis

Gastroenteritis is marked by severe inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract involving both the stomach and small intestine resulting in acute diarrhea and vomiting. It can be transferred by contact with contaminated food and water...

, are transmitted by the faecal-oral route

Fecal-oral route

The fecal-oral route, or alternatively, the oral-fecal route or orofecal route is a route of transmission of diseases, in which they are passed when pathogens in fecal particles from one host are introduced into the oral cavity of another potential host.There are usually intermediate steps,...

and are passed from person to person by contact, entering the body in food or water. HIV

HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus is a lentivirus that causes acquired immunodeficiency syndrome , a condition in humans in which progressive failure of the immune system allows life-threatening opportunistic infections and cancers to thrive...

is one of several viruses transmitted through sexual contact

Sexual intercourse

Sexual intercourse, also known as copulation or coitus, commonly refers to the act in which a male's penis enters a female's vagina for the purposes of sexual pleasure or reproduction. The entities may be of opposite sexes, or they may be hermaphroditic, as is the case with snails...

and by exposure to infected blood. The range of host cells that a virus can infect is called its "host range". This can be narrow or, as when a virus is capable of infecting many species, broad.

Viral infections in animals provoke an immune response that usually eliminates the infecting virus. Immune responses can also be produced by vaccine

Vaccine

A vaccine is a biological preparation that improves immunity to a particular disease. A vaccine typically contains an agent that resembles a disease-causing microorganism, and is often made from weakened or killed forms of the microbe or its toxins...

s, which confer an artificially acquired immunity

Immunity (medical)

Immunity is a biological term that describes a state of having sufficient biological defenses to avoid infection, disease, or other unwanted biological invasion. Immunity involves both specific and non-specific components. The non-specific components act either as barriers or as eliminators of wide...

to the specific viral infection. However, some viruses including those causing AIDS

AIDS

Acquired immune deficiency syndrome or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome is a disease of the human immune system caused by the human immunodeficiency virus...

and viral hepatitis

Viral hepatitis

Viral hepatitis is liver inflammation due to a viral infection. It may present in acute or chronic forms. The most common causes of viral hepatitis are the five unrelated hepatotropic viruses Hepatitis A, Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C, Hepatitis D, and Hepatitis E...

evade these immune responses and result in chronic infections. Antibiotic

Antibiotic

An antibacterial is a compound or substance that kills or slows down the growth of bacteria.The term is often used synonymously with the term antibiotic; today, however, with increased knowledge of the causative agents of various infectious diseases, antibiotic has come to denote a broader range of...

s have no effect on viruses, but several antiviral drug

Antiviral drug

Antiviral drugs are a class of medication used specifically for treating viral infections. Like antibiotics for bacteria, specific antivirals are used for specific viruses...

s have been developed.

Etymology

The word is from the LatinLatin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

virus referring to poison

Poison

In the context of biology, poisons are substances that can cause disturbances to organisms, usually by chemical reaction or other activity on the molecular scale, when a sufficient quantity is absorbed by an organism....

and other noxious substances, first used in English in 1392. Virulent, from Latin virulentus (poisonous), dates to 1400. A meaning of "agent that causes infectious disease" is first recorded in 1728, before the discovery of viruses by Dmitry Ivanovsky in 1892. The plural is viruses. The adjective viral dates to 1948. The term virion is also used to refer to a single infective viral particle.

History

Louis Pasteur

Louis Pasteur was a French chemist and microbiologist born in Dole. He is remembered for his remarkable breakthroughs in the causes and preventions of diseases. His discoveries reduced mortality from puerperal fever, and he created the first vaccine for rabies and anthrax. His experiments...

was unable to find a causative agent for rabies

Rabies

Rabies is a viral disease that causes acute encephalitis in warm-blooded animals. It is zoonotic , most commonly by a bite from an infected animal. For a human, rabies is almost invariably fatal if post-exposure prophylaxis is not administered prior to the onset of severe symptoms...

and speculated about a pathogen too small to be detected using a microscope. In 1884, the French microbiologist

Microbiologist

A microbiologist is a scientist who works in the field of microbiology. Microbiologists study organisms called microbes. Microbes can take the form of bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protists...

Charles Chamberland

Charles Chamberland

Charles Chamberland was a French microbiologist from Chilly-le-Vignoble in the department of Jura who worked with Louis Pasteur....

invented a filter (known today as the Chamberland filter

Chamberland filter

A Chamberland filter, also known as a Pasteur-Chamberland filter, is a porcelain water filter invented by Charles Chamberland in 1884. It is similar to the Berkefeld filter in principle.-Design:...

or Chamberland-Pasteur filter) with pores smaller than bacteria. Thus, he could pass a solution containing bacteria through the filter and completely remove them from the solution. In 1892, the Russian biologist Dmitry Ivanovsky used this filter to study what is now known as the tobacco mosaic virus

Tobacco mosaic virus

Tobacco mosaic virus is a positive-sense single stranded RNA virus that infects plants, especially tobacco and other members of the family Solanaceae. The infection causes characteristic patterns on the leaves . TMV was the first virus to be discovered...

. His experiments showed that crushed leaf extracts from infected tobacco plants remain infectious after filtration. Ivanovsky suggested the infection might be caused by a toxin

Toxin

A toxin is a poisonous substance produced within living cells or organisms; man-made substances created by artificial processes are thus excluded...

produced by bacteria, but did not pursue the idea. At the time it was thought that all infectious agents could be retained by filters and grown on a nutrient medium – this was part of the germ theory of disease. In 1898, the Dutch microbiologist Martinus Beijerinck

Martinus Beijerinck

Martinus Willem Beijerinck was a Dutch microbiologist and botanist. Born in Amsterdam, Beijerinck studied at the Technical School of Delft, where he was awarded the degree of Chemical Engineer in 1872. He obtained his Doctor of Science degree from the University of Leiden in 1877...

repeated the experiments and became convinced that the filtered solution contained a new form of infectious agent. He observed that the agent multiplied only in cells that were dividing, but as his experiments did not show that it was made of particles, he called it a contagium vivum fluidum (soluble living germ) and re-introduced the word virus. Beijerinck maintained that viruses were liquid in nature, a theory later discredited by Wendell Stanley, who proved they were particulate. In the same year Friedrich Loeffler and Frosch passed the first animal virus – agent of foot-and-mouth disease

Foot-and-mouth disease

Foot-and-mouth disease or hoof-and-mouth disease is an infectious and sometimes fatal viral disease that affects cloven-hoofed animals, including domestic and wild bovids...

(aphthovirus

Aphthovirus

Aphthovirus is a viral genus of the family Picornaviridae. Aphthoviruses infect vertebrates, and include the causative agent of foot-and-mouth disease. Foot-and-mouth disease virus is the prototypic member of the genus Aphthovirus...

) – through a similar filter.

In the early 20th century, the English bacteriologist Frederick Twort

Frederick Twort

Frederick William Twort was an English bacteriologist and was the original discoverer in 1915 of bacteriophages . He studied medicine at St Thomas's Hospital, London, was superintendent of the Brown Institute for Animals , and he was also professor of bacteriology at the University of London...

discovered a group of viruses that infect bacteria, now called bacteriophages (or commonly phages), and the French-Canadian microbiologist Félix d'Herelle

Félix d'Herelle

Félix d'Herelle was a French-Canadian microbiologist, the co-discoverer of bacteriophages and experimented with the possibility of phage therapy.-Early years:...

described viruses that, when added to bacteria on agar

Agar

Agar or agar-agar is a gelatinous substance derived from a polysaccharide that accumulates in the cell walls of agarophyte red algae. Throughout history into modern times, agar has been chiefly used as an ingredient in desserts throughout Asia and also as a solid substrate to contain culture medium...

, would produce areas of dead bacteria. He accurately diluted a suspension of these viruses and discovered that the highest dilutions (lowest virus concentrations), rather than killing all the bacteria, formed discrete areas of dead organisms. Counting these areas and multiplying by the dilution factor allowed him to calculate the number of viruses in the original suspension. Phages were heralded as a potential treatment for diseases such as typhoid and cholera

Cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine that is caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. The main symptoms are profuse watery diarrhea and vomiting. Transmission occurs primarily by drinking or eating water or food that has been contaminated by the diarrhea of an infected person or the feces...

, but their promise was forgotten with the development of penicillin

Penicillin