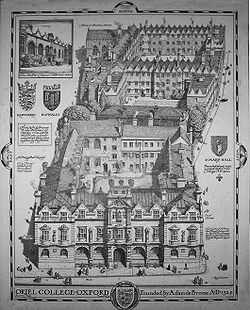

Oriel College

Encyclopedia

Oriel College is a constituent college

of the University of Oxford

in Oxford

, England

. Located in Oriel Square

, the college has the distinction of being the oldest royal foundation in Oxford (a title formerly claimed by University College

, whose claim of being founded by King Alfred

is no longer promoted). In recognition of this royal connection, the college has also been known as King's College and King's Hall.

The original medieval

foundation set up by Adam de Brome

, under the patronage of Edward II

, was called the House or Hall of the Blessed Mary at Oxford. The first design allowed for a Provost

and ten Fellows, called 'scholars', and the College remained a small body of graduate Fellows until the 16th century, when it started to admit undergraduates. During the English Civil War

, Oriel played host to high-ranking members of the King's Oxford Parliament

.

The main site of the College incorporates four medieval halls: Bedel Hall, St Mary Hall

, St Martin Hall and Tackley's Inn, the last being the earliest property acquired by the college and the oldest standing medieval hall in Oxford. The College has nearly 40 Fellows, about 300 undergraduates and some 160 graduates, the student body having roughly equal numbers of men and women. The College's MCR is rapidly growing, and in 2010, the college admitted roughly equal numbers of undergraduate and graduate students.

Oriel's notable alumni include two Nobel laureates; prominent Fellows have included John Keble

and The Blessed John Henry Newman, founders of the Oxford Movement

. Among Oriel's more notable possessions are a painting by Bernard van Orley

and three pieces of medieval silver plate. As of 2006, the college's estimated financial endowment

was £

77 million.

, Adam de Brome

, obtained a licence from Edward II

to found a "certain college of scholars studying various disciplines in honour of the Virgin" and to endow it to the value of £30 a year. De Brome bought two properties in 1324, Tackley's Hall, on the south side of the High Street

and Perilous Hall, on the north side of Broad Street

, and as an investment, he purchased the advowson

of a church in Aberford

.

De Brome's foundation was confirmed in a charter of 21 January 1326, in which the Crown, represented by the Lord Chancellor

De Brome's foundation was confirmed in a charter of 21 January 1326, in which the Crown, represented by the Lord Chancellor

, was to exercise the rights of Visitor

; a further charter drawn up in May of that year gave the rights of Visitor to Henry Burghersh

, Bishop of Lincoln

, Oxford at that time being part of the diocese of Lincoln

. Under Edward's patronage, de Brome diverted the revenue of the University Church to his college, which thereafter was responsible for appointing the vicar and providing four chaplains to celebrate the daily services in the church. The college lost no time in seeking royal favour again after Edward II's deposition, and Edward III

confirmed his father's favour in February 1327, but the amended statutes remained in force with the Bishop of Lincoln as Visitor. In 1329, the college received through royal grant a large house belonging to the crown, known as La Oriole, standing on the site of what is now First quad; it is from this property that the college acquired its common name, "Oriel", the name being in use from about 1349. The word referred to an oratoriolum, or oriel window

, forming a feature of the earlier property.

In the early 1410s several Fellows of Oriel took part in the disturbances accompanying Archbishop Arundel

's attempt to stamp out Lollardy

in the University; the Lollard belief that religious power and authority came through piety

and not through the hierarchy of the Church particularly inflamed passions in Oxford, where its proponent, John Wycliffe

, had been head of Balliol

. Disregarding the Provost's authority, Oriel Fellows fought bloody battles with other scholars, killed one of the Chancellor

's servants when they attacked his house, and were prominent among the group that obstructed the Archbishop and ridiculed his censures.

In 1442, Henry VI

sanctioned an arrangement whereby the town was to pay the college £25 a year from the fee farm in exchange for decayed property, allegedly worth £30 a year, which the college could not afford to keep in repair. The arrangement was cancelled in 1450.

In 1643 a general obligation was imposed on Oxford colleges to support the Royalist cause

In 1643 a general obligation was imposed on Oxford colleges to support the Royalist cause

in the English Civil War

, the King called for Oriel's plate and almost all of it was given, the total weighing . of gilt, and . of "white" plate. In the same year the College was assessed at £1 for the weekly sum of £40 charged on the colleges and halls for the fortification of the city. When the Oxford Parliament

was assembled during the Civil War in 1644, Oriel housed the Executive Committee of the Privy council, Parliament being held at neighbouring Christ Church

. Following the defeat of the Royalist cause, the University was scrutinised by the Parliamentarians, and five of the eighteen Oriel Fellows were removed. The Visitors, using their own authority, elected Fellows between 1648 and October 1652, when without reference to the Commissioners, John Washbourne was chosen; the autonomy of the College in this respect seems to have been restored.

In 1673 James Davenant, a Fellow since 1661, complained to William Fuller

, then Bishop of Lincoln, about Provost Say's conduct in the election of Thomas Twitty to a Fellowship. Bishop Fuller appointed a commission that included the Vice-Chancellor, Peter Mews

, the Dean of Christ Church, John Fell

, and the Principal of Brasenose

, Thomas Yates. On 1 August Fell reported to the Bishop that;

On 24 January 1674, Bishop Fuller issued a decree dealing with the recommendations of the commissioners — a majority of all the Fellows should always be insisted on, so the Provost could not push an election in a thin meeting, and Fellows should be admitted immediately after their election. On 28 January Provost Say obtained a recommendation for Twitty's election from the King, but it was withdrawn on 13 February, following the Vice-Chancellor's refusal to swear Twitty into the University and the Bishop's protests at Court.

During the early 1720s, a constitutional struggle began between the Provost and the Fellows, culminating in a lawsuit. In 1721, Henry Edmunds was elected as a Fellow by 9 votes to 3; his election was rejected by Provost George Carter, and on appeal, by the Visitor, Edmund Gibson

During the early 1720s, a constitutional struggle began between the Provost and the Fellows, culminating in a lawsuit. In 1721, Henry Edmunds was elected as a Fellow by 9 votes to 3; his election was rejected by Provost George Carter, and on appeal, by the Visitor, Edmund Gibson

, then Bishop of Lincoln. Rejections of candidates by the Provost continued, fueling discontent among the Fellows, until a writ of attachment

against the Bishop of Lincoln was heard between 1724 and 1726. The opposing Fellows, led by Edmunds, appealed to the first set of statutes, claiming the Crown as Visitor, making Gibson's decisions invalid; Provost Carter, supported by Bishop Gibson, appealed to the second set, claiming the Bishop of Lincoln as Visitor. The jury decided for the Fellows, supporting the original charter of Edward II.

In a private printing of 1899 Provost Shadwell lists thirteen Gaudies

observed by the College during the 18th century; by the end of the 19th century all but two, the Feast of the Immaculate Conception

and the Purification of the Virgin, had ceased to be celebrated.

gained Oriel the reputation of being the most brilliant college of the day and the centre of the "Oriel Noetics" — clerical liberals such as Richard Whately

and Thomas Arnold

were Fellows, and the during the 1830s, two intellectually eminent Fellows of Oriel, John Keble

and The Blessed John Henry Newman, supported by Canon Pusey

(also an Oriel fellow initially, later at Christ Church

) and others, formed a group known as the Oxford Movement

, alternatively as the Tractarians, or familiarly as the Puseyites. The group were disgusted by the indolence

prevailing in the Church, and they sought to revive the spirit of early Christianity

, this caused tension in College as Provost Edward Hawkins

was a determined opponent of the Movement.

During World War I

During World War I

, a wall was built dividing Third quad from Second quad to accommodate students of Somerville College

, while their college was being used as a military hospital. At this time Oxford separated male and female students as far as possible; Vera Brittain

, one of the Somerville students, recalled an amusing occurrence during her time there in her autobiography, Testament of Youth

;

In 1985, the college became the last all-male college in Oxford to admit women for matriculation

as undergraduates. In 1984, the Senior Common Room voted 23-4 to admit women undergraduates from 1986. The Junior Common Room president believed that "the distinctive character of the college will be undermined".

A second Feast Day was added in 2007 by a benefaction from Orielensis George Moody, to be celebrated on or near St George's Day

(23 April). The only remaining gaudy had been Candlemas, the new annual dinner will be known as the St. George's Day Gaudy. The dinner is black tie

and gowns, and by request of the benefactor, the main course will normally be goose. The inaugural event took place on Wednesday 25 April 2007.

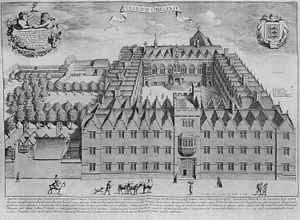

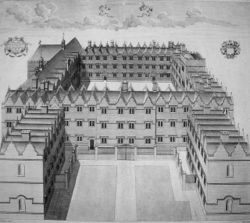

Nothing survives of the original buildings, La Oriole and the smaller St Martin's Hall in the south-east; both were demolished before the quadrangle

Nothing survives of the original buildings, La Oriole and the smaller St Martin's Hall in the south-east; both were demolished before the quadrangle

was built in the artisan mannerist style during the 17th century. The south and west ranges and the gate tower were built around 1620 to 1622; the north and east ranges and the chapel buildings date from 1637 to 1642. The façade of the east range forms a classical E shape comprising the college chapel, hall and undercroft

. The exterior and interior of the ranges are topped by an alternating pattern of decorative gable

s. The gate house has a Perp portal and canted Gothic

oriel windows, with fan vaulting in the entrance. The room above has a particularly fine plaster ceiling and chimneypiece of stucco

caryatid

s and panelling

interlaced with studded bands sprouting into large flowers.

The cartouches

over staircases one, two, three, five and six and the chapel, bar and provost's lodgings entrances bear the arms of important figures in the College's history; (1) Anthony Blencowe (Provost 1574-1618) who left money that paid for building the west side of front quad. (2) Richard Dudley (Fellow 1495-1536) who gave property for Fellowships. (3) John Carpenter (Provost 1428-1435, later Bishop Carpenter) who gave property, plate, Fellowships and Exhibitions. (Chapel) John Frank (Master of the Rolls) gave property for Fellowships around 1441. (Bar) William Lewis (Provost 1618-1621) who canvassed successfully for donations for the rebuilding of college. (5) William Smith (Bishop of Lincoln) who gave property for a Fellowship around 1508. (Provost's lodgings) John Tolson who was Provost during the building of Front Quad. (6) Edward Hawkins (Provost 1828-1882).

of the hall entrance commemorates its construction during the reign of Charles I

with the legend "REGNANTE CAROLO", Charles, being King, in pierced stonework. The portico was completely rebuilt in 1897, and above it are statues of two Kings: Edward II on the left, and probably either Charles I or James I

, although this is disputed; above those is a statue of the Blessed Virgin Mary after whom the College is officially named. The top breaks the Jacobean

tradition and has classical

pilaster

s, a shield with garlands, and a segmental pediment

.

The hall has a hammerbeam roof

; the louvre in the centre is now glazed, but was originally the only means of escape for smoke rising from a fireplace in the centre of the floor. The wooden panelling was designed by Ninian Comper

and was erected in 1911 in place of some previous 19th-century Gothic

type, though even earlier panelling, dating from 1710, is evident in the Buttery.

Behind the High Table is a portrait of Edward II; underneath is a longsword

brought to the college in 1902 after being preserved for many years on one of the college's estates at Swainswick

, near Bath. On either side are portraits of Sir Walter Raleigh

and Joseph Butler

. The other portraits around the hall include other prominent members of Oriel such as Cecil Rhodes

, Matthew Arnold

, Thomas Arnold

, James Anthony Froude

, John Keble

, John Henry Newman, Richard Whately

and John Robinson

.

The heraldic glass

in the windows display the coats of arms

of benefactors and distinguished members of the College; three of the windows were designed by Ninian Comper. The window next to the entrance on the East side contains the arms of Regius Professors of Modern History

who have been ex-officio Fellows of the College.

's visit to Oxford in that year. The present building was consecrated in 1642 and despite subsequent restorations it largely retains its original appearance.

The bronze lectern

The bronze lectern

was given to the College in 1654. The black and white marble paving dates from 1677–78. Except for the pew

s on the west, dating from 1884, the panelling, stalls and screens are all 17th-century, as are the altar and carved communion rails

. Behind the altar is Bernard van Orley

's The Carrying of the Cross

— a companion-piece to this painting is in the National Gallery of Scotland

. The organ case dates from 1716; originally designed by Christopher Schreider for St Mary Abbots

Church, Kensington, it was acquired by Oriel in 1884.

In the north-west window of the gallery there is a small piece of late medieval

glass, a figure of St Margaret of Antioch. In the south window of the gallery there is a painted window of "The Presentation of Christ in the Temple

", executed by William Peckitt

of York. It was originally set in the east window in 1767; a later version of his work can be seen in New College

Chapel. The rest of the stained glass

is Victorian

: the earliest is on the easternmost part of the south side; the rest date from after the 1884 restorations by Powell.

Above the entrance to the chapel is an oriel that, until the 1880s, was a room on the first floor that formed part of a set of rooms that were occupied by Richard Whately

, and later by John Henry Newman. Whately is said to have used the space as a larder and Newman is said to have used it for his private prayers — when the organ was installed in 1884, the space was used for the blower. The wall that once separated the room from the ante-chapel

was removed, making it accessible from the chapel. The organ was built by J. W. Walker & Sons in 1988; in 1991 the space behind the organ was rebuilt as an oratory and memorial to Newman and the Oxford Movement

. A new stained glass window designed by Vivienne Haig and realised by Douglas Hogg was completed and installed in 2001.

During the late 1980s, the chapel was extensively restored with the assistance of donations from Lady Norma Dalrymple-Champneys. During this work, the chandelier, given in 1885 by Provost Shadwell while still a Fellow, was put back in place, the organ was restored, the painting mounted behind the altar, and the chapel repainted. A list of former chaplains and organ scholars was erected in the ante-chapel. The Chaplain is Rev Dr Robert Tobin and the Senior Organ Scholar for 2010-11 is Edwin Lock.

at the suggestion of his wife, as the inscription over the door records. Its twin block, the Carter Building, was erected on the west side in 1729, as a result of a benefaction by Provost Carter. The two buildings stood for nearly a hundred years as detached blocks in the garden, and the architectural elements of the First quad are repeated on them — only here the seven gables are all alike. Between 1817 and 1819, they were joined up to the Front quad with their present, rather incongruous connecting links. In the link to the Robinson Building, two purpose-built rooms have been incorporated - the Champneys Room, designed by Weldon Champneys, the nephew of Basil Champneys

, and the Benefactors Room, a panelled room honouring benefactors of the college. A Gothic oriel window, belonging to the Provost's Lodgings, was added to the Carter Building in 1826.

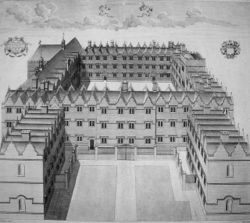

The north range houses the library and senior common rooms; designed in the Neoclassical

The north range houses the library and senior common rooms; designed in the Neoclassical

style by James Wyatt

, it was built between 1788 and 1796 to accommodate the books bequested by Edward, Baron Leigh

, formerly High Steward of the University and an Orielensis, whose gift had doubled the size of the library. The two-storey building has rusticated

arches on the ground floor and a row of Ionic

columns above, dividing the façade into seven bays — the ground floor contains the first purpose built senior common rooms in Oxford, above is the library.

On 7 March 1949, a fire spread from the library roof; over 300 printed books and the manuscripts on exhibition were completely destroyed, and over 3,000 books needed repair, though the main structure suffered little damage and restoration took less than a year.

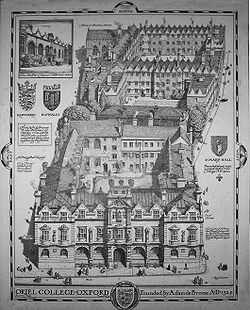

, which was incorporated into Oriel in 1902; less than a decade later, the Hall's buildings on the northern side were demolished for the construction of the Rhodes Building. Bedel Hall in the south was formally amalgamated with St Mary Hall in 1505.

In the south range, parts of the medieval buildings survive and are incorporated into staircase ten — the straight, steep flight of stairs and timber framed partitions date from a mid-15th century rebuilding of St Mary Hall. The former Chapel, Hall and Buttery

of St Mary Hall, built in 1640, form part of the Junior Library and Junior Common Room. Viewed from the third quad, the Chapel, with its Gothic windows, can be seen to have been built neatly on top of the Hall, a unique example in Oxford of such a plan.

On the east side of the quad is a simple rustic style timber-frame building; known as "the Dolls House", it was erected by Principal King in 1743.

In 1826 an ornate range was erected in the Gothic Revival

style, incorporating the old gate of St Mary Hall, on the west side of the quad. Designed by Daniel Robertson

, it contains two quite ornate oriels placed asymmetrically, one is of six lights, the other four. They are the best example of the pre-archaeological Gothic in Oxford. The large oriel on the first floor at the north end was once the drawing room of the Principal of Hall. Parts of the street wall incorporated into this range show traces of blocked windows dating from the same period of rebuilding in the 15th century as staircase ten.

The Rhodes Building, pictured right, was built in 1911 using £100,000 left to the College for that purpose by former student Cecil Rhodes

The Rhodes Building, pictured right, was built in 1911 using £100,000 left to the College for that purpose by former student Cecil Rhodes

. It was designed by Basil Champneys

and stands on the site of the Principal's house, on the High Street. Champney's first proposal for the building included an open arcade

to the High Street, a dome

d central feature and balustraded

parapet

. The left hand block and much of the centre was to be given up to a new Provost's Lodging, and the five windows on the first floor above the arcade were to light a gallery belonging to the Lodging. The college eventually decided to retain the existing Provost's Lodging and demanded detailing "more in accordance with the style which has become traditional in Oxford". It became the last building of the Jacobean revival style

in Oxford.

On the side facing the High Street, there is a statue of Rhodes over the main entrance, with Edward VII

and George V

beneath. The inscription reads: "e Larga MUnIfICentIa CaeCILII rhoDes", which, as well as acknowledging Rhodes' munificence, is a chronogram

giving the date of construction, MDCCCLLVIIIIII.

The staircases of the interior façade are decorated with cartouches similar to those found in First Quad, and likewise bear the arms of important figures in the College's history; (13) Sir Walter Raleigh who was an undergraduate from 1572 to 1574, (14) John Keble who was a Fellow between 1811 and 1835), (archway) Edward Hawkins who was Provost from 1828 until 1882 and (15) Gilbert White who was an undergraduate from 1739 until 1743 and a Fellow from 1744 until 1793.

The building was not entirely well received; William Sherwood, Mayor of Oxford and Master of Magdalen College School

, wrote:

, and the meeting of Oriel Street

and King Edward Street

in Oriel Square

. The site took six hundred years to acquire and although it contains teaching rooms and the Harris Lecture Theatre, it is largely given over to accommodation.

On the High Street

, No. 106 and 107 stand on the site of Tackley's Inn; built around 1295, it was the first piece of property that Adam de Brome acquired when he began to found the college in 1324. It comprised a hall and chambers leased to scholars, behind a frontage of five shops, with the scholars above and a cellar of five bays below. The hall, which was open to the roof, was 33 feet (10 m) long, 20 feet (6 m) wide, and about 22 feet (7 m) high; at the east end was a large chamber with another chamber above it. The south wall of the building, which survives, was partly of stone and contains a large two-light early 14th-century window. The cellar below is of the same date and is the best preserved medieval cellar in Oxford; originally entered by stone steps from the street, it has a stone vault

divided into four sections by two diagonal ribs, with carved corbel

s.

The Oriel Street

site was acquired between 1329 and 1392. No. 12, now staircases 19 and 20, is the oldest tenement acquired by the college; known as Kylyngworth's, it was granted to the college in 1392 by Thomas de Lentwardyn, Fellow and later Provost, having previously been let to William de Daventre, Oriel's fourth Provost, in 1367. A back wing to the property was added around 1600 and further work to the front was conducted in 1724–38. In 1985, funded by a gift from Edgar O'Brien and £10,000 from the Pilgrim Trust

, Kylyngworth's was refurbished along with Nos. 10, 9 and 7.

King Edward Street

King Edward Street

was created by the college between 1872 and 1873 when 109 and 110 High Street were demolished. The old shops on each side of the road were pulled down and rebuilt, and to preserve the continuity, the new shops were numbered 108 and 109–112. Named after the college's founder, the road was opened in 1873. On the wall of the first floor of No. 6, there is a large metal plaque with a portrait of Cecil Rhodes; underneath is the inscription:

In the centre of the quad is the Harris Building, formerly Oriel court

, a real tennis

court where Charles I

played tennis with his nephew Prince Rupert

in December 1642 and King Edward VII

had his first tennis lesson in 1859. The building was in use as a lecture hall by 1923, and after modernisation between 1991 and 1994, funded by Sir Philip and Lady Harris, contains accommodation, a seminar room and the college's main lecture theatre. The bronze plaque in the lobby commemorates Sir Philip's father, Captain Charles William Harris, after whom the building is named. The building was opened by John Major

, then Prime Minister

, on 10 August 1993.

Whereas the staircases on the first three quadrangles are marked with Arabic numerals

, the Island site is marked with Roman numerals

. Both sites have the numbering running anticlockwise around each quadrangle and there are two staircase eighteens − Mary Quad's staircase numbering finishes at 18 and O'Brien Quad's staircase numbering begins with XVIII.

Bordered by the Cowley Road

Bordered by the Cowley Road

, this site was formerly Nazareth House, a residential care home convent

— Goldie Wing (shown left) and Larmenier House are its surviving buildings. Nazareth House itself was demolished to make room for two purpose-built halls of residence, James Mellon Hall (shown right) and David Paterson House. The two new halls were opened by Queen Elizabeth II

on 8 November 2000.

As it is about ten minutes walk from College and more peaceful than the middle of the city, it has become the principal choice of accommodation for Oriel's graduates and finalists. The site has its own common rooms, squash

court, gym

nasium and support staff.

; it includes the sports grounds for Oriel, Jesus

and Lincoln

Colleges, along with landscaping for wildlife and small scale urban development.

In 1326 Provost Adam de Brome was appointed warden of St Bartholomew's; a leper hospital in Cowley Marsh

, the hospital was later granted to the college by Edward III

, along with the payments it had been receiving from the fee farm. It was increasingly used as a rest house for sick members of the college needing a change of air. In 1649 the college rebuilt the main hospital range north of the chapel, destroyed in the Civil War, as a row of four almshouse

s, called Bartlemas House. Bartlemas Chapel and two farm cottages are the other extant buildings.

In heraldic

In heraldic

terminology: Gules, three lions passant guardant Or within a bordure engrailed Argent.

The arms of the College are based on those of the founder Edward II

, the three gold lions of England on a red background. However, as no one may bear another's arms unaltered, an engrailed silver border was added "for difference".

The three feathers

, often adopted by members of the College, can be found in decorations around college and is the motif on the college crested tie. It probably represents Edward, the Black Prince, although it may represent King Charles I

, who was Prince of Wales

when the building of First quad began in the 17th century.

College colours

, used on the college scarf, sports clothing, oar blades

and the like, are two white stripes on navy.

A badge for the use of Oriel College Boat Club, the Tortoise Club and the Oriel Society was granted by Letters Patent dated 20 April 2009 of Garter

, Clarenceux

and Norroy and Ulster King of Arms

. The Badge is blazoned A Tortoise displayed the shell circular Azure charged with two concentric annulets Argent.

, the following Latin grace

is recited by one of the student bible clerks. The translation is reputedly by Erasmus

in his Convivium Religiosum of a grace recorded by St John Chrysostom

:

After the meal, the Provost, or a Fellow, usually recites a short Latin prayer [Benedicto benedicatur, per Jesum Christum, Let praise be given to/by the Blessed One] instead of the full post cibum grace:

Students are admitted to Oriel in line with the common framework the Oxford University Colleges adhere to, which lays down the principles and procedures for admission to Oxford University, which they all observe.

Students are admitted to Oriel in line with the common framework the Oxford University Colleges adhere to, which lays down the principles and procedures for admission to Oxford University, which they all observe.

Accommodation is provided for all undergraduates, and for some graduates, though some accommodation is off-site. Members are generally expected to dine in hall, where there are two sittings every evening, one informal

and one formal

, except on Saturdays, where there is only an informal sitting. The Bar, situated underneath the Hall, serves food from mid-morning and drinks in the evening; its LCD TV was installed prior to the 2006 football World Cup

. There is both a Junior Common Room (JCR), between Second and Third quad, and a Middle Common Room (MCR), on the Island Site.

The college lending library supplements the university libraries; with over 100,000 volumes, it is one of the largest college libraries in the university and will purchase books needed for the course. Most undergraduate tutorials are carried out in the college, though for other specialist papers, undergraduates may be sent to tutors in other colleges.

Between 2001-2010, Oriel College students chose not to be affiliated to the University-wide Students' union

, OUSU

, although this did not stop some students from getting involved with OUSU and running for elected office. In a 2010 student referendum the JCR decided to reaffiliate.

Oriel College has its own drama society, the Oriel Lions, which funds college and Oxford University shows.

Oriel has a reputation for its success in rowing

Oriel has a reputation for its success in rowing

, in particular the two intercollegiate bumps race

s, Torpids

and Eights Week

. In 2005 they remained "Head of the River

" in Torpids and rowed over second in Eights Week. Having been awarded spoons in Summer Eights 2006 after being bumped every day of racing, the Men's 1st VIII bumped twice in 2007 and twice again in 2008 to return to 2nd on the River, behind Balliol College. The women's 1st VIII has also had success in Summer Eights in recent years, winning blades in 2007 after bumping on all four days and finishing 2008 in Division I for the first time since 1994. In 2006 Oriel claimed the first ever double headship in Torpids, rowing over as Head of the River in both the men's and women's first divisions. Both Men's and Women's 1st VIIIs ceded the headship of Torpids in 2008 by being bumped; the positions remained unchanged in 2007 as Torpids were cancelled.

On the afternoons of the Thursday, Friday and Saturday of 7th week in Trinity Term

, the boat club hosts the annual Oriel Regatta; events in this competition include side-by-side racing for eights, coxed fours, pairs and single sculls. The course runs upstream from the Longbridges Boathouse to past the end of boathouses on Christ Church Island and are conducted in knock-out format.

Croquet

may be played in St Mary quad in the summer, as can bowls

on the south lawn of First quad. The sports ground is mainly used for cricket

, tennis

, rugby union

and football

. Rowing is carried out from the boat-house across Christ Church Meadow

.

to cricket

ers to industrialists; their most famous undergraduate is the 16th-century explorer

, Sir Walter Raleigh

. The College has produced many churchmen, bishops, cardinals, governors, and two Nobel Prize

recipients: Alexander Todd

(Chemistry) and James Meade

(Economics).

The Professorial Fellowships the College holds are: the Regius Professor of Modern History

, held by Robert Evans

and formerly by Sir John Elliott

and Thomas Arnold

, the Oriel Professor of the Interpretation of Holy Scripture

, held by John Barton

, the Nolloth Professor of the Philosophy of the Christian Religion, held by Brian Leftow

, and the Nuffield Professor of Obstetrics and Gynaecology.

. The first is a French beaker and cover in silver gilt; past estimates on its dating from 1460–70 are thought mistaken, and circa 1350, with later decoration, was later expounded. It was bought in 1493 for £4.18s.1d., under the mistaken belief that it had belonged to Edward II

. In a college inventory of plate dated 21 December 1596, it is named as the Founder's Cup.

The second notable piece of plate is a mazer

of maplewood with silver gilt mounts, dating from 1470–85. On the edge of the rim is a row of grouped beads; below is an inscription in black letters:

This type of shallow drinking vessel was quite common in the Middle Ages, but the only other mazers in Oxford are three dating from the 15th century, and one standing mazer from 1529–30, all belonging to All Souls

. Thirdly is a coconut cup, one of six in Oxford; the Oriel cup has silver gilt mounts and dates from the first quarter of the 16th century.

Among the later plate are two flagons, two pattens and a chalice

which date from 1640–41. The larger pieces of Buttery Plate include the Sanford and Heywood grace cups

, dated 1654–55 and 1669–70, a rosewater ewer gifted in 1669, a punchbowl dating from 1735–36, and the great Wenman tankard presented in 1679, which holds a gallon and is the largest in Oxford. Many of the 17th- and 18th-century tankards were given by commensales and commoners as a form of admission fee.

's first film, Privileged

(1982), as well as Oxford Blues

(1984), True Blue

(1991) and The Dinosaur Hunter (2000).

The television crime series Inspector Morse

used the College in the episodes "Ghost in the Machine", under the name of 'Courtenay College', "The Silent World of Nicholas Quinn", "The Infernal Serpent", "Deadly Slumber", "Twilight of the Gods" and "Death is now My Neighbour", and in the one off follow on, Lewis, the Middle Common Room and Oriel Square

were used.

In the first series of Chancer

, broadcast in 1990, Oriel College was featured under its genuine name as the home of Lynsey Baxter

's character, Victoria Douglas. Filming was done on Staircase 14 in the Rhodes Building, and also featured prominent shots of the first and third quadrangles and of Oriel Square.

The quads and interiors were used in a 2006 documentary on Gilbert White

by Michael Wood, both being former students of the college.

In Tom Brown at Oxford

by Thomas Hughes

, Oriel's win in the 1842 Head of the River Race

, with Oriel bumping Trinity, was re-written as Tom's college, "St Ambrose" taking first place and "Oriel" in second place.

In The Covenant

, by James A. Michener

, the English characters all went to Oriel.

Colleges of the University of Oxford

The University of Oxford comprises 38 Colleges and 6 Permanent Private Halls of religious foundation. Colleges and PPHs are autonomous self-governing corporations within the university, and all teaching staff and students studying for a degree of the university must belong to one of the colleges...

of the University of Oxford

University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a university located in Oxford, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest surviving university in the world and the oldest in the English-speaking world. Although its exact date of foundation is unclear, there is evidence of teaching as far back as 1096...

in Oxford

Oxford

The city of Oxford is the county town of Oxfordshire, England. The city, made prominent by its medieval university, has a population of just under 165,000, with 153,900 living within the district boundary. It lies about 50 miles north-west of London. The rivers Cherwell and Thames run through...

, England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

. Located in Oriel Square

Oriel Square

Oriel Square, formerly known as Canterbury Square is a square in central Oxford, England, located south of the High Street. The name was changed after the Second World War at the request of Oriel College which maintained that the square had originally been known as Oriel Square.To the east at the...

, the college has the distinction of being the oldest royal foundation in Oxford (a title formerly claimed by University College

University College, Oxford

.University College , is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. As of 2009 the college had an estimated financial endowment of £110m...

, whose claim of being founded by King Alfred

Alfred the Great

Alfred the Great was King of Wessex from 871 to 899.Alfred is noted for his defence of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of southern England against the Vikings, becoming the only English monarch still to be accorded the epithet "the Great". Alfred was the first King of the West Saxons to style himself...

is no longer promoted). In recognition of this royal connection, the college has also been known as King's College and King's Hall.

The original medieval

Middle Ages

The Middle Ages is a periodization of European history from the 5th century to the 15th century. The Middle Ages follows the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 and precedes the Early Modern Era. It is the middle period of a three-period division of Western history: Classic, Medieval and Modern...

foundation set up by Adam de Brome

Adam de Brome

Adam de Brome was an almoner to King Edward II and founder of Oriel College in Oxford, England.De Brome was probably the son of Thomas de Brome, taking his name from Brome near Eye in Suffolk; an inquisition held after the death of Edmund, 2nd Earl of Cornwall, in 1300, noted de Brome holding an...

, under the patronage of Edward II

Edward II of England

Edward II , called Edward of Caernarfon, was King of England from 1307 until he was deposed by his wife Isabella in January 1327. He was the sixth Plantagenet king, in a line that began with the reign of Henry II...

, was called the House or Hall of the Blessed Mary at Oxford. The first design allowed for a Provost

Provost (education)

A provost is the senior academic administrator at many institutions of higher education in the United States, Canada and Australia, the equivalent of a pro-vice-chancellor at some institutions in the United Kingdom and Ireland....

and ten Fellows, called 'scholars', and the College remained a small body of graduate Fellows until the 16th century, when it started to admit undergraduates. During the English Civil War

English Civil War

The English Civil War was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between Parliamentarians and Royalists...

, Oriel played host to high-ranking members of the King's Oxford Parliament

Oxford Parliament (1644)

The Oxford Parliament was the Parliament assembled by King Charles I for the first time 22 January 1644 and adjourned for the last time on 10 March 1645, with the purpose of instrumenting the Royalist war campaign.Charles was advised by Edward Hyde and others not to dissolve the Long Parliament as...

.

The main site of the College incorporates four medieval halls: Bedel Hall, St Mary Hall

St Mary Hall, Oxford

St Mary Hall was an academic hall of the University of Oxford associated with Oriel College since 1326, but which functioned independently from 1545 to 1902.- History :...

, St Martin Hall and Tackley's Inn, the last being the earliest property acquired by the college and the oldest standing medieval hall in Oxford. The College has nearly 40 Fellows, about 300 undergraduates and some 160 graduates, the student body having roughly equal numbers of men and women. The College's MCR is rapidly growing, and in 2010, the college admitted roughly equal numbers of undergraduate and graduate students.

Oriel's notable alumni include two Nobel laureates; prominent Fellows have included John Keble

John Keble

John Keble was an English churchman and poet, one of the leaders of the Oxford Movement, and gave his name to Keble College, Oxford.-Early life:...

and The Blessed John Henry Newman, founders of the Oxford Movement

Oxford Movement

The Oxford Movement was a movement of High Church Anglicans, eventually developing into Anglo-Catholicism. The movement, whose members were often associated with the University of Oxford, argued for the reinstatement of lost Christian traditions of faith and their inclusion into Anglican liturgy...

. Among Oriel's more notable possessions are a painting by Bernard van Orley

Bernard van Orley

Bernard van Orley , also called Barend or Barent van Orley, Bernaert van Orley or Barend van Brussel, was a Flemish Northern Renaissance painter and draughtsman, and also a leading designer of tapestries and stained glass...

and three pieces of medieval silver plate. As of 2006, the college's estimated financial endowment

Financial endowment

A financial endowment is a transfer of money or property donated to an institution. The total value of an institution's investments is often referred to as the institution's endowment and is typically organized as a public charity, private foundation, or trust....

was £

Pound sterling

The pound sterling , commonly called the pound, is the official currency of the United Kingdom, its Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands, British Antarctic Territory and Tristan da Cunha. It is subdivided into 100 pence...

77 million.

Middle Ages

On 24 April 1324, the Rector of the University ChurchUniversity Church of St Mary the Virgin

The University Church of St Mary the Virgin is the largest of Oxford's parish churches and the centre from which the University of Oxford grew...

, Adam de Brome

Adam de Brome

Adam de Brome was an almoner to King Edward II and founder of Oriel College in Oxford, England.De Brome was probably the son of Thomas de Brome, taking his name from Brome near Eye in Suffolk; an inquisition held after the death of Edmund, 2nd Earl of Cornwall, in 1300, noted de Brome holding an...

, obtained a licence from Edward II

Edward II of England

Edward II , called Edward of Caernarfon, was King of England from 1307 until he was deposed by his wife Isabella in January 1327. He was the sixth Plantagenet king, in a line that began with the reign of Henry II...

to found a "certain college of scholars studying various disciplines in honour of the Virgin" and to endow it to the value of £30 a year. De Brome bought two properties in 1324, Tackley's Hall, on the south side of the High Street

High Street, Oxford

The High Street in Oxford, England runs between Carfax, generally recognized as the centre of the city, and Magdalen Bridge to the east. Locally the street is often known as The High. It forms a gentle curve and is the subject of many prints, paintings, photographs, etc...

and Perilous Hall, on the north side of Broad Street

Broad Street, Oxford

Broad Street is a wide street in central Oxford, England, located just north of the old city wall.The street is known for its bookshops, including the original Blackwell's bookshop at number 50, located here due to the University...

, and as an investment, he purchased the advowson

Advowson

Advowson is the right in English law of a patron to present or appoint a nominee to a vacant ecclesiastical benefice or church living, a process known as presentation. In effect this means the right to nominate a person to hold a church office in a parish...

of a church in Aberford

Aberford

Aberford is a large village and civil parish on the eastern outskirts of the City of Leeds metropolitan borough in West Yorkshire, England. It has a population of 1,059 according to the 2001 census...

.

Lord Chancellor

The Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, or Lord Chancellor, is a senior and important functionary in the government of the United Kingdom. He is the second highest ranking of the Great Officers of State, ranking only after the Lord High Steward. The Lord Chancellor is appointed by the Sovereign...

, was to exercise the rights of Visitor

Visitor

A Visitor, in United Kingdom law and history, is an overseer of an autonomous ecclesiastical or eleemosynary institution , who can intervene in the internal affairs of that institution...

; a further charter drawn up in May of that year gave the rights of Visitor to Henry Burghersh

Henry Burghersh

Henry Burghersh , English bishop and chancellor, was a younger son of Robert de Burghersh, 1st Baron Burghersh , and a nephew of Bartholomew, Lord Badlesmere, and was educated in France....

, Bishop of Lincoln

Bishop of Lincoln

The Bishop of Lincoln is the Ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Lincoln in the Province of Canterbury.The present diocese covers the county of Lincolnshire and the unitary authority areas of North Lincolnshire and North East Lincolnshire. The Bishop's seat is located in the Cathedral...

, Oxford at that time being part of the diocese of Lincoln

Diocese of Lincoln

The Diocese of Lincoln forms part of the Province of Canterbury in England. The present diocese covers the ceremonial county of Lincolnshire.- History :...

. Under Edward's patronage, de Brome diverted the revenue of the University Church to his college, which thereafter was responsible for appointing the vicar and providing four chaplains to celebrate the daily services in the church. The college lost no time in seeking royal favour again after Edward II's deposition, and Edward III

Edward III of England

Edward III was King of England from 1327 until his death and is noted for his military success. Restoring royal authority after the disastrous reign of his father, Edward II, Edward III went on to transform the Kingdom of England into one of the most formidable military powers in Europe...

confirmed his father's favour in February 1327, but the amended statutes remained in force with the Bishop of Lincoln as Visitor. In 1329, the college received through royal grant a large house belonging to the crown, known as La Oriole, standing on the site of what is now First quad; it is from this property that the college acquired its common name, "Oriel", the name being in use from about 1349. The word referred to an oratoriolum, or oriel window

Oriel window

Oriel windows are a form of bay window commonly found in Gothic architecture, which project from the main wall of the building but do not reach to the ground. Corbels or brackets are often used to support this kind of window. They are seen in combination with the Tudor arch. This type of window was...

, forming a feature of the earlier property.

In the early 1410s several Fellows of Oriel took part in the disturbances accompanying Archbishop Arundel

Thomas Arundel

Thomas Arundel was Archbishop of Canterbury in 1397 and from 1399 until his death, an outspoken opponent of the Lollards.-Family background:...

's attempt to stamp out Lollardy

Lollardy

Lollardy was a political and religious movement that existed from the mid-14th century to the English Reformation. The term "Lollard" refers to the followers of John Wycliffe, a prominent theologian who was dismissed from the University of Oxford in 1381 for criticism of the Church, especially his...

in the University; the Lollard belief that religious power and authority came through piety

Piety

In spiritual terminology, piety is a virtue that can mean religious devotion, spirituality, or a combination of both. A common element in most conceptions of piety is humility.- Etymology :...

and not through the hierarchy of the Church particularly inflamed passions in Oxford, where its proponent, John Wycliffe

John Wycliffe

John Wycliffe was an English Scholastic philosopher, theologian, lay preacher, translator, reformer and university teacher who was known as an early dissident in the Roman Catholic Church during the 14th century. His followers were known as Lollards, a somewhat rebellious movement, which preached...

, had been head of Balliol

Balliol College, Oxford

Balliol College , founded in 1263, is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England but founded by a family with strong Scottish connections....

. Disregarding the Provost's authority, Oriel Fellows fought bloody battles with other scholars, killed one of the Chancellor

Chancellor (education)

A chancellor or vice-chancellor is the chief executive of a university. Other titles are sometimes used, such as president or rector....

's servants when they attacked his house, and were prominent among the group that obstructed the Archbishop and ridiculed his censures.

In 1442, Henry VI

Henry VI of England

Henry VI was King of England from 1422 to 1461 and again from 1470 to 1471, and disputed King of France from 1422 to 1453. Until 1437, his realm was governed by regents. Contemporaneous accounts described him as peaceful and pious, not suited for the violent dynastic civil wars, known as the Wars...

sanctioned an arrangement whereby the town was to pay the college £25 a year from the fee farm in exchange for decayed property, allegedly worth £30 a year, which the college could not afford to keep in repair. The arrangement was cancelled in 1450.

Early Modern

Cavalier

Cavalier was the name used by Parliamentarians for a Royalist supporter of King Charles I and son Charles II during the English Civil War, the Interregnum, and the Restoration...

in the English Civil War

First English Civil War

The First English Civil War began the series of three wars known as the English Civil War . "The English Civil War" was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations that took place between Parliamentarians and Royalists from 1642 until 1651, and includes the Second English Civil War and...

, the King called for Oriel's plate and almost all of it was given, the total weighing . of gilt, and . of "white" plate. In the same year the College was assessed at £1 for the weekly sum of £40 charged on the colleges and halls for the fortification of the city. When the Oxford Parliament

Oxford Parliament (1644)

The Oxford Parliament was the Parliament assembled by King Charles I for the first time 22 January 1644 and adjourned for the last time on 10 March 1645, with the purpose of instrumenting the Royalist war campaign.Charles was advised by Edward Hyde and others not to dissolve the Long Parliament as...

was assembled during the Civil War in 1644, Oriel housed the Executive Committee of the Privy council, Parliament being held at neighbouring Christ Church

Christ Church, Oxford

Christ Church or house of Christ, and thus sometimes known as The House), is one of the largest constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England...

. Following the defeat of the Royalist cause, the University was scrutinised by the Parliamentarians, and five of the eighteen Oriel Fellows were removed. The Visitors, using their own authority, elected Fellows between 1648 and October 1652, when without reference to the Commissioners, John Washbourne was chosen; the autonomy of the College in this respect seems to have been restored.

In 1673 James Davenant, a Fellow since 1661, complained to William Fuller

William Fuller (bishop)

William Fuller was an English churchman.He was dean of St Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin , bishop of Limerick , and bishop of Lincoln . He was also the friend of Samuel Pepys and John Evelyn.-Life:...

, then Bishop of Lincoln, about Provost Say's conduct in the election of Thomas Twitty to a Fellowship. Bishop Fuller appointed a commission that included the Vice-Chancellor, Peter Mews

Peter Mews

Peter Mews was an English Royalist theologian and bishop.-Life:Mews was born at Caundle Purse in Dorset, and was educated at the Merchant Taylors' School, London, and at St John's College, Oxford, of which he was scholar and fellow.When the Civil War broke out in 1642, Mews joined the Royalist...

, the Dean of Christ Church, John Fell

John Fell (clergyman)

John Fell was an English churchman and influential academic. He served as Dean of Christ Church, Oxford, and later concomitantly as Bishop of Oxford.-Education:...

, and the Principal of Brasenose

Brasenose College, Oxford

Brasenose College, originally Brazen Nose College , is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. As of 2006, it has an estimated financial endowment of £98m...

, Thomas Yates. On 1 August Fell reported to the Bishop that;

When this Devil of buying and selling is once cast out, your Lordship will, I hope, take care that he return not again, lest he bring seven worse than himself into the house after 'tis swept and garnisht.

On 24 January 1674, Bishop Fuller issued a decree dealing with the recommendations of the commissioners — a majority of all the Fellows should always be insisted on, so the Provost could not push an election in a thin meeting, and Fellows should be admitted immediately after their election. On 28 January Provost Say obtained a recommendation for Twitty's election from the King, but it was withdrawn on 13 February, following the Vice-Chancellor's refusal to swear Twitty into the University and the Bishop's protests at Court.

Edmund Gibson

Edmund Gibson was a British divine and jurist.-Early life and career:He was born in Bampton, Westmorland. In 1686 he was entered a scholar at Queen's College, Oxford...

, then Bishop of Lincoln. Rejections of candidates by the Provost continued, fueling discontent among the Fellows, until a writ of attachment

Writ of attachment

A writ of attachment is a court order to "attach" or seize an asset. It is issued by a court to a law enforcement officer or sheriff. The writ of attachment is issued in order to satisfy a judgment issued by the court. A prejudgment writ of attachment may be used to freeze assets of a defendant...

against the Bishop of Lincoln was heard between 1724 and 1726. The opposing Fellows, led by Edmunds, appealed to the first set of statutes, claiming the Crown as Visitor, making Gibson's decisions invalid; Provost Carter, supported by Bishop Gibson, appealed to the second set, claiming the Bishop of Lincoln as Visitor. The jury decided for the Fellows, supporting the original charter of Edward II.

In a private printing of 1899 Provost Shadwell lists thirteen Gaudies

Gaudy

Gaudy or gaudie is a term used to reflect student life in a number of the ancient universities in the United Kingdom...

observed by the College during the 18th century; by the end of the 19th century all but two, the Feast of the Immaculate Conception

Feast of the Immaculate Conception

The Feast of the Immaculate Conception celebrates belief in the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary. It is celebrated on 8 December, nine months before the Nativity of Mary, which is celebrated on 8 September. It is the patronal feast day of the United States and the Republic of the...

and the Purification of the Virgin, had ceased to be celebrated.

Modern

In the early 19th century, the reforming zeal of Provosts John Eveleigh and Edward CoplestonEdward Copleston

Edward Copleston was an English churchman and academic, Provost of Oriel College, Oxford from 1814 and bishop of Llandaff from 1827.-Life:He was born at Offwell in Devon, and educated at Oxford University....

gained Oriel the reputation of being the most brilliant college of the day and the centre of the "Oriel Noetics" — clerical liberals such as Richard Whately

Richard Whately

Richard Whately was an English rhetorician, logician, economist, and theologian who also served as the Church of Ireland Archbishop of Dublin.-Life and times:...

and Thomas Arnold

Thomas Arnold

Dr Thomas Arnold was a British educator and historian. Arnold was an early supporter of the Broad Church Anglican movement...

were Fellows, and the during the 1830s, two intellectually eminent Fellows of Oriel, John Keble

John Keble

John Keble was an English churchman and poet, one of the leaders of the Oxford Movement, and gave his name to Keble College, Oxford.-Early life:...

and The Blessed John Henry Newman, supported by Canon Pusey

Edward Bouverie Pusey

Edward Bouverie Pusey was an English churchman and Regius Professor of Hebrew at Christ Church, Oxford. He was one of the leaders of the Oxford Movement.-Early years:...

(also an Oriel fellow initially, later at Christ Church

Christ Church, Oxford

Christ Church or house of Christ, and thus sometimes known as The House), is one of the largest constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England...

) and others, formed a group known as the Oxford Movement

Oxford Movement

The Oxford Movement was a movement of High Church Anglicans, eventually developing into Anglo-Catholicism. The movement, whose members were often associated with the University of Oxford, argued for the reinstatement of lost Christian traditions of faith and their inclusion into Anglican liturgy...

, alternatively as the Tractarians, or familiarly as the Puseyites. The group were disgusted by the indolence

Laziness

Laziness is a disinclination to activity or exertion despite having the ability to do so. It is often used as a pejorative; related terms for a person seen to be lazy include couch potato, slacker, and bludger....

prevailing in the Church, and they sought to revive the spirit of early Christianity

Early Christianity

Early Christianity is generally considered as Christianity before 325. The New Testament's Book of Acts and Epistle to the Galatians records that the first Christian community was centered in Jerusalem and its leaders included James, Peter and John....

, this caused tension in College as Provost Edward Hawkins

Edward Hawkins

Edward Hawkins was an English churchman and academic, a long-serving Provost of Oriel College, Oxford known as a committed opponent of the Oxford Movement from its beginnings in his college.-Life:...

was a determined opponent of the Movement.

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, a wall was built dividing Third quad from Second quad to accommodate students of Somerville College

Somerville College, Oxford

Somerville College is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England, and was one of the first women's colleges to be founded there...

, while their college was being used as a military hospital. At this time Oxford separated male and female students as far as possible; Vera Brittain

Vera Brittain

Vera Mary Brittain was a British writer, feminist and pacifist, best remembered as the author of the best-selling 1933 memoir Testament of Youth, recounting her experiences during World War I and the beginning of her journey towards pacifism.-Life:Born in Newcastle-under-Lyme, Brittain was the...

, one of the Somerville students, recalled an amusing occurrence during her time there in her autobiography, Testament of Youth

Testament of Youth

Testament of Youth is the first installment, covering 1900–1925, in the memoir of Vera Brittain . It was published in 1933. Brittain's memoir continues with Testament of Experience, published in 1957, and encompassing the years 1925–1950...

;

[...] the few remaining undergraduates in the still masculine section of Oriel not unnaturally concluded that it would be a first-rate "rag" to break down the wall which divided them from the carefully guarded young females in St. Mary Hall. Great perturbation filled the souls of the Somerville dons when they came down to breakfast one morning to find that a large gap had suddenly appeared in the protecting masonry, through which had been thrust a hilarious placard:

"'OO MADE THIS 'ERE 'OLE?"

"MICE!!!"

Throughout that day and the following night the Senior Common Room, from the Principal downwards, took it in turns to sit on guard beside the hole, for fear any unruly spirit should escape through it to the forbidden adventurous males on the other side.

In 1985, the college became the last all-male college in Oxford to admit women for matriculation

Matriculation

Matriculation, in the broadest sense, means to be registered or added to a list, from the Latin matricula – little list. In Scottish heraldry, for instance, a matriculation is a registration of armorial bearings...

as undergraduates. In 1984, the Senior Common Room voted 23-4 to admit women undergraduates from 1986. The Junior Common Room president believed that "the distinctive character of the college will be undermined".

A second Feast Day was added in 2007 by a benefaction from Orielensis George Moody, to be celebrated on or near St George's Day

St George's Day

St George's Day is celebrated by the several nations, kingdoms, countries, and cities of which Saint George is the patron saint. St George's Day is celebrated on 23 April, the traditionally accepted date of Saint George's death in AD 303...

(23 April). The only remaining gaudy had been Candlemas, the new annual dinner will be known as the St. George's Day Gaudy. The dinner is black tie

Black tie

Black tie is a dress code for evening events and social functions. For a man, the main component is a usually black jacket, known as a dinner jacket or tuxedo...

and gowns, and by request of the benefactor, the main course will normally be goose. The inaugural event took place on Wednesday 25 April 2007.

Front Quad (First quadrangle)

Quadrangle (architecture)

In architecture, a quadrangle is a space or courtyard, usually rectangular in plan, the sides of which are entirely or mainly occupied by parts of a large building. The word is probably most closely associated with college or university campus architecture, but quadrangles may be found in other...

was built in the artisan mannerist style during the 17th century. The south and west ranges and the gate tower were built around 1620 to 1622; the north and east ranges and the chapel buildings date from 1637 to 1642. The façade of the east range forms a classical E shape comprising the college chapel, hall and undercroft

Undercroft

An undercroft is traditionally a cellar or storage room, often brick-lined and vaulted, and used for storage in buildings since medieval times. In modern usage, an undercroft is generally a ground area which is relatively open to the sides, but covered by the building above.- History :While some...

. The exterior and interior of the ranges are topped by an alternating pattern of decorative gable

Gable

A gable is the generally triangular portion of a wall between the edges of a sloping roof. The shape of the gable and how it is detailed depends on the structural system being used and aesthetic concerns. Thus the type of roof enclosing the volume dictates the shape of the gable...

s. The gate house has a Perp portal and canted Gothic

Gothic architecture

Gothic architecture is a style of architecture that flourished during the high and late medieval period. It evolved from Romanesque architecture and was succeeded by Renaissance architecture....

oriel windows, with fan vaulting in the entrance. The room above has a particularly fine plaster ceiling and chimneypiece of stucco

Stucco

Stucco or render is a material made of an aggregate, a binder, and water. Stucco is applied wet and hardens to a very dense solid. It is used as decorative coating for walls and ceilings and as a sculptural and artistic material in architecture...

caryatid

Caryatid

A caryatid is a sculpted female figure serving as an architectural support taking the place of a column or a pillar supporting an entablature on her head. The Greek term karyatides literally means "maidens of Karyai", an ancient town of Peloponnese...

s and panelling

Panelling

Panelling is a wall covering constructed from rigid or semi-rigid components. These are traditionally interlocking wood, but could be plastic or other materials....

interlaced with studded bands sprouting into large flowers.

The cartouches

Cartouche (design)

A cartouche is an oval or oblong design with a slightly convex surface, typically edged with ornamental scrollwork. It is used to hold a painted or low relief design....

over staircases one, two, three, five and six and the chapel, bar and provost's lodgings entrances bear the arms of important figures in the College's history; (1) Anthony Blencowe (Provost 1574-1618) who left money that paid for building the west side of front quad. (2) Richard Dudley (Fellow 1495-1536) who gave property for Fellowships. (3) John Carpenter (Provost 1428-1435, later Bishop Carpenter) who gave property, plate, Fellowships and Exhibitions. (Chapel) John Frank (Master of the Rolls) gave property for Fellowships around 1441. (Bar) William Lewis (Provost 1618-1621) who canvassed successfully for donations for the rebuilding of college. (5) William Smith (Bishop of Lincoln) who gave property for a Fellowship around 1508. (Provost's lodgings) John Tolson who was Provost during the building of Front Quad. (6) Edward Hawkins (Provost 1828-1882).

Hall

In the centre of the East range, the porticoPortico

A portico is a porch leading to the entrance of a building, or extended as a colonnade, with a roof structure over a walkway, supported by columns or enclosed by walls...

of the hall entrance commemorates its construction during the reign of Charles I

Charles I of England

Charles I was King of England, King of Scotland, and King of Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. Charles engaged in a struggle for power with the Parliament of England, attempting to obtain royal revenue whilst Parliament sought to curb his Royal prerogative which Charles...

with the legend "REGNANTE CAROLO", Charles, being King, in pierced stonework. The portico was completely rebuilt in 1897, and above it are statues of two Kings: Edward II on the left, and probably either Charles I or James I

James I of England

James VI and I was King of Scots as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the English and Scottish crowns on 24 March 1603...

, although this is disputed; above those is a statue of the Blessed Virgin Mary after whom the College is officially named. The top breaks the Jacobean

Jacobean architecture

The Jacobean style is the second phase of Renaissance architecture in England, following the Elizabethan style. It is named after King James I of England, with whose reign it is associated.-Characteristics:...

tradition and has classical

Classical order

A classical order is one of the ancient styles of classical architecture, each distinguished by its proportions and characteristic profiles and details, and most readily recognizable by the type of column employed. Three ancient orders of architecture—the Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian—originated in...

pilaster

Pilaster

A pilaster is a slightly-projecting column built into or applied to the face of a wall. Most commonly flattened or rectangular in form, pilasters can also take a half-round form or the shape of any type of column, including tortile....

s, a shield with garlands, and a segmental pediment

Pediment

A pediment is a classical architectural element consisting of the triangular section found above the horizontal structure , typically supported by columns. The gable end of the pediment is surrounded by the cornice moulding...

.

The hall has a hammerbeam roof

Hammerbeam roof

Hammerbeam roof, in architecture, is the name given to an open timber roof, typical of English Gothic architecture, using short beams projecting from the wall.- Design :...

; the louvre in the centre is now glazed, but was originally the only means of escape for smoke rising from a fireplace in the centre of the floor. The wooden panelling was designed by Ninian Comper

Ninian Comper

Sir John Ninian Comper was a Scottish-born architect. He was one of the last of the great Gothic Revival architects, noted for his churches and their furnishings...

and was erected in 1911 in place of some previous 19th-century Gothic

Gothic Revival architecture

The Gothic Revival is an architectural movement that began in the 1740s in England...

type, though even earlier panelling, dating from 1710, is evident in the Buttery.

Behind the High Table is a portrait of Edward II; underneath is a longsword

Longsword

The longsword is a type of European sword designed for two-handed use, current during the late medieval and Renaissance periods, approximately 1350 to 1550 .Longswords have long cruciform hilts with grips over 10 to 15 cm length The longsword (of which stems the variation called the bastard...

brought to the college in 1902 after being preserved for many years on one of the college's estates at Swainswick

Swainswick

Swainswick is a small village and civil parish, north east of Bath, on the A46 in the Bath and North East Somerset unitary authority, Somerset, England. The parish has a population of 284...

, near Bath. On either side are portraits of Sir Walter Raleigh

Walter Raleigh

Sir Walter Raleigh was an English aristocrat, writer, poet, soldier, courtier, spy, and explorer. He is also well known for popularising tobacco in England....

and Joseph Butler

Joseph Butler

Joseph Butler was an English bishop, theologian, apologist, and philosopher. He was born in Wantage in the English county of Berkshire . He is known, among other things, for his critique of Thomas Hobbes's egoism and John Locke's theory of personal identity...

. The other portraits around the hall include other prominent members of Oriel such as Cecil Rhodes

Cecil John Rhodes

Cecil John Rhodes PC, DCL was an English-born South African businessman, mining magnate, and politician. He was the founder of the diamond company De Beers, which today markets 40% of the world's rough diamonds and at one time marketed 90%...

, Matthew Arnold

Matthew Arnold

Matthew Arnold was a British poet and cultural critic who worked as an inspector of schools. He was the son of Thomas Arnold, the famed headmaster of Rugby School, and brother to both Tom Arnold, literary professor, and William Delafield Arnold, novelist and colonial administrator...

, Thomas Arnold

Thomas Arnold

Dr Thomas Arnold was a British educator and historian. Arnold was an early supporter of the Broad Church Anglican movement...

, James Anthony Froude

James Anthony Froude

James Anthony Froude , 23 April 1818–20 October 1894, was an English historian, novelist, biographer, and editor of Fraser's Magazine. From his upbringing amidst the Anglo-Catholic Oxford Movement, Froude intended to become a clergyman, but doubts about the doctrines of the Anglican church,...

, John Keble

John Keble

John Keble was an English churchman and poet, one of the leaders of the Oxford Movement, and gave his name to Keble College, Oxford.-Early life:...

, John Henry Newman, Richard Whately

Richard Whately

Richard Whately was an English rhetorician, logician, economist, and theologian who also served as the Church of Ireland Archbishop of Dublin.-Life and times:...

and John Robinson

John Robinson (1650-1723)

John Robinson was an English diplomat and prelate.-Early life:Robinson was born at Cleasby, North Yorkshire, near Darlington, a son of John Robinson . Educated at Brasenose College, Oxford, he became a fellow of Oriel College, and about 1680 chaplain to the British embassy to Stockholm, and...

.

The heraldic glass

Stained glass

The term stained glass can refer to coloured glass as a material or to works produced from it. Throughout its thousand-year history, the term has been applied almost exclusively to the windows of churches and other significant buildings...

in the windows display the coats of arms

Coat of arms

A coat of arms is a unique heraldic design on a shield or escutcheon or on a surcoat or tabard used to cover and protect armour and to identify the wearer. Thus the term is often stated as "coat-armour", because it was anciently displayed on the front of a coat of cloth...

of benefactors and distinguished members of the College; three of the windows were designed by Ninian Comper. The window next to the entrance on the East side contains the arms of Regius Professors of Modern History

Regius Professor of Modern History (Oxford)

The Regius Professor of Modern History at the University of Oxford is an old-established professorial position. The first appointment was made in 1724...

who have been ex-officio Fellows of the College.

Chapel

The current chapel is Oriel's third, the first being built around 1373 on the north side of the front quadrangle. By 1566, the chapel was located on the south side of the quadrangle, as shown in a drawing made for Elizabeth IElizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I was queen regnant of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death. Sometimes called The Virgin Queen, Gloriana, or Good Queen Bess, Elizabeth was the fifth and last monarch of the Tudor dynasty...

's visit to Oxford in that year. The present building was consecrated in 1642 and despite subsequent restorations it largely retains its original appearance.

Lectern

A lectern is a reading desk with a slanted top, usually placed on a stand or affixed to some other form of support, on which documents or books are placed as support for reading aloud, as in a scripture reading, lecture, or sermon...

was given to the College in 1654. The black and white marble paving dates from 1677–78. Except for the pew

Pew

A pew is a long bench seat or enclosed box used for seating members of a congregation or choir in a church, or sometimes in a courtroom.-Overview:Churches were not commonly furnished with permanent pews before the Protestant Reformation...

s on the west, dating from 1884, the panelling, stalls and screens are all 17th-century, as are the altar and carved communion rails

Altar rails

Altar rails are a set of railings, sometimes ornate and frequently of marble or wood, delimiting the chancel in a church, the part of the sanctuary that contains the altar. A gate at the centre divides the line into two parts. The sanctuary is a figure of heaven, into which entry is not guaranteed...

. Behind the altar is Bernard van Orley

Bernard van Orley

Bernard van Orley , also called Barend or Barent van Orley, Bernaert van Orley or Barend van Brussel, was a Flemish Northern Renaissance painter and draughtsman, and also a leading designer of tapestries and stained glass...

's The Carrying of the Cross

Stations of the Cross

Stations of the Cross refers to the depiction of the final hours of Jesus, and the devotion commemorating the Passion. The tradition as chapel devotion began with St...

— a companion-piece to this painting is in the National Gallery of Scotland

National Gallery of Scotland

The National Gallery of Scotland, in Edinburgh, is the national art gallery of Scotland. An elaborate neoclassical edifice, it stands on The Mound, between the two sections of Edinburgh's Princes Street Gardens...

. The organ case dates from 1716; originally designed by Christopher Schreider for St Mary Abbots

St Mary Abbots

St Mary Abbots is an historic church located on Kensington High Street , London at a prominent intersection with Kensington Church Street. The present church was built in 1872 by the architect Sir George Gilbert Scott in neo-Gothic Early English style. It was the latest in a succession of churches...

Church, Kensington, it was acquired by Oriel in 1884.

In the north-west window of the gallery there is a small piece of late medieval

Late Middle Ages

The Late Middle Ages was the period of European history generally comprising the 14th to the 16th century . The Late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern era ....

glass, a figure of St Margaret of Antioch. In the south window of the gallery there is a painted window of "The Presentation of Christ in the Temple

Presentation of Jesus at the Temple

The Presentation of Jesus at the Temple, which falls on 2 February, celebrates an early episode in the life of Jesus. In the Eastern Orthodox Church and some Eastern Catholic Churches, it is one of the twelve Great Feasts, and is sometimes called Hypapante...

", executed by William Peckitt

William Peckitt

William Peckitt was an English glass-painter and stained glass maker. He was based in York throughout his working life, was one of the leading Georgian glass craftsmen in England and helped “keep the art of glass painting alive during the eighteenth century"...

of York. It was originally set in the east window in 1767; a later version of his work can be seen in New College

New College, Oxford

New College is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom.- Overview :The College's official name, College of St Mary, is the same as that of the older Oriel College; hence, it has been referred to as the "New College of St Mary", and is now almost always...

Chapel. The rest of the stained glass

Stained glass