First English Civil War

Encyclopedia

The First English Civil War (1642–1646) began the series of three wars known as the English Civil War

(or "Wars"). "The English Civil War" was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations that took place between Parliamentarians

and Royalist

s from 1642 until 1651, and includes the Second English Civil War

(1648–1649) and the Third English Civil War

(1649–1651).

and the Scottish Civil War, which began with the raising of King Charles I's

standard at Nottingham

on 22 August 1642, and ended on 3 September 1651 at the Battle of Worcester

. There was some continued organised Royalist resistance in Scotland, which lasted until the surrender of Dunnottar Castle

to Parliament's troops in May 1652, but this resistance is not usually included as part of the English Civil War. The English Civil War can be divided into three: the First English Civil War (1642–1646), the Second English Civil War (1648–1649), and the Third English Civil War (1649–1651).

For the most part, accounts summarize the two sides that fought the English Civil Wars as the Royalist Cavaliers of Charles I of England

versus the Parliamentarian Roundheads of Oliver Cromwell

. However, as with many civil wars, loyalties shifted for various reasons, and both sides changed significantly during the conflicts.

During most of this time, the Irish Confederate Wars

(another civil war), continued in Ireland

, starting with the Irish Rebellion of 1641

and ending with the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland

. Its incidents had little or no direct connection with those of the English Civil War, but the wars were inextricably mixed with, and formed part of, a linked series of conflicts and civil wars between 1639 and 1652 in the kingdoms of England, Scotland

, and Ireland, which at that time shared a monarch

, but were distinct countries in political organisation. These linked conflicts are also known as the Wars of the Three Kingdoms

by some recent historians, aiming to have a unified overview, rather than treating parts of the other conflicts as a background to the English Civil War.

The first and last of these motives animated the foot-soldiers of the Royal armies. These sturdy rustics who followed their squire

s to the war, saw the enemy as rebels and fanatics. The cavalry

, which was composed largely of the higher social orders, the rebels were, in addition, bourgeois, while the soldiers of fortune

from the German

wars felt all the regulars' contempt for citizen militia

.

The other side of the war saw the causes of the quarrel primarily and apparently as political, but ultimately and really felt them as religious. Thus, the elements of resistance in Parliament and the nation were at first confused, and, later, strong and direct. Democracy

, moderate republicanism

, and the simple desire for constitutional guarantees could hardly make head of themselves against the various forces of royalism, for the most moderate men of either party were sufficiently in sympathy to admit compromise. But the backbone of resistance was the Puritan element, and this waging war at first with the rest on the political issue, soon (as the Royalists anticipated) brought the religious issue to the front.

The Presbyterian system, even more rigid than that of the Archbishop of Canterbury

, William Laud

and the other bishop

s, whom no man on either side except Charles himself supported, seemed destined for replacement by the Independents and by their ideal of free conscience. But for a generation before the war broke out, the system had disciplined and trained the middle classes of the nation (who furnished the bulk of the rebel infantry

, and later, of the cavalry also) to centre their will on the attainment of their ideals. The ideals changed during the struggle, but not the capacity for striving for them, and the men capable of the effort finally came to the front, and imposed their ideals on the rest by the force of their trained wills.

Parliamentary party had the stronger material force. They controlled the navy, the nucleus of an army that was being organised for the Irish war, and nearly all the financial resources of the country. They had the sympathies of most of the large towns, where the trained bands, drilled once a month, provided cadres for new regiment

s. Also, by recognising that war was likely, they prepared for war before Royalists did.

The Earl of Warwick

, the Earl of Essex

, the Earl of Manchester

, and other nobles and gentry

of the Parliamentary party, had great wealth and territorial influence. On the other hand, Charles could raise men without authority from Parliament by using impressment

and the Lords-Lieutenant, but could not raise tax

es to support them. Thus he depended on financial support from his adherents, such as the Earl of Newcastle

and the Earl of Derby

.

", while the king claimed the old-fashioned "Commissions of Array." For example, in Cornwall

the Royalist leader Sir Ralph Hopton indicted the enemy before the grand jury

of the county for disturbing the peace, and expelled them by using the posse comitatus

. In effect, both sides assembled local forces wherever they could do so by valid written authority.

This thread of local feeling and respect for the laws runs through the early operations of both sides, almost irrespective of the main principles at stake. Many promising schemes failed because of the reluctance of militiamen to serve outside their own county. As the offensive lay with the King, his cause naturally suffered from this far more than that of Parliament.

However, the real spirit of the struggle proved very different. Anything that prolonged the struggle, or seemed like a lack of energy or an avoidance of decision, was bitterly resented by the men of both sides. They had their hearts in the quarrel, and had not yet learned by the severe lesson of Edgehill

that raw armies cannot quickly end wars. In France

and Germany, the prolongation of a war meant continued employment for soldiers, but in England:

This passage from the Memoirs of a Cavalier, ascribed to Daniel Defoe

, though not contemporary evidence, is an admirable summary of the character of the Civil War. Even when in the end a regular professional army developed, the original decision-compelling spirit permeated the whole organisation as was seen when pitched against regular professional continental troops at the Battle of the Dunes

during the Interregnum

.

From the start, most of the population of England mistrusted professional soldiers of fortune, be their advice good or bad. Nearly all those Englishmen who loved war for its own sake were too closely concerned for the welfare of their country to attempt the methods of the Thirty Years' War

in England. The formal organisation of both armies was based on the Swedish

model, which had become the pattern of Europe after the victories of Gustavus Adolphus. It gave better scope for the morale of the individual than the old-fashioned Spanish

and Dutch

formations, in which the man in the ranks was a highly finished automaton.

at Nottingham on 22 August 1642, fighting had already started on a small scale in many districts; each side endeavouring to secure, or to deny to the enemy, fortified country-houses, territory, and above all arms and money. Peace negotiations went on at the same time as these minor events until Parliament issued an aggressive ultimatum. That ultimatum fixed the war-like purpose of the still vacillating court at Nottingham, and in the country at large, to convert many thousands of waverers to active Royalism.

Soon, Charles increased his army from fewer than 1,500 men to almost equal the Parliament's army, though greatly lacking in arms and equipment. The Parliament army had about 20,000 men, plus detachments

. It was organized during July, August and September about London

, and moved to Northampton

under the command of Lord Essex.

At this moment, the Marquess of Hertford

At this moment, the Marquess of Hertford

in South Wales

, Hopton in Cornwall, and the young Earl of Derby in Lancashire

, and small parties in almost every county of the west and the Midlands, were in arms for the King. North of the Tees, Newcastle, a great territorial magnate, was raising troops and supplies for the King, while Queen Henrietta Maria was busy in Holland, arranging for the importation of war material and money. In Yorkshire

, opinion was divided, the royal cause being strongest in York

and the North Riding

, that of the Parliamentary party, in the clothing towns of the West Riding

.

The important seaport of Hull

, had a royalist civilian population, but Sir John Hotham

, the military governor, and the garrison supported Parliament. During the summer, Charles had tried to seize ammunition stored in the city but had been forcefully rebuffed

.

The Yorkshire gentry made an attempt to neutralise the county, but a local struggle soon began, and Newcastle thereupon prepared to invade Yorkshire. The whole of the south and east, as well as parts of the Midlands

and the west, and the important towns of Bristol

and Gloucester

, stood on the side of the Parliament. A small Royalist force was compelled to evacuate Oxford

on 10 September.

On 13 September, the main campaign opened. The King, in order to find recruits among his sympathisers and arms in the armouries

of the Derbyshire

and Staffordshire

, trained bands and also to keep in touch with his disciplined regiments in Ireland by way of Chester

, moved westward to Shrewsbury

. Essex followed suit by marching his army from Northampton to Worcester

. Near here, a sharp cavalry engagement, Powick Bridge

, took place on 23 September between the advanced cavalry of Essex's army, and a force under Prince Rupert, which was engaged in protecting the retreat of the Oxford detachment. The result of the fight was the immediate overthrow of the Parliamentary cavalry. This gave the Royalist troopers confidence in themselves and in their brilliant leader, which was not shaken until they met Oliver Cromwell's

Ironsides

.

Rupert soon withdrew to Shrewsbury, where he found many Royalist officers eager to attack Essex's new position at Worcester. But the road to London now lay open and the commanders decided to take it. The intention was not to avoid a battle, because the Royalist generals wanted to fight Essex before he grew too strong. In the Earl of Clarendon's

words: "it was considered more counsellable to march towards London, it being morally sure that Essex would put himself in their way." Accordingly, the army left Shrewsbury on 12 October, gaining two days' start on the enemy, and moved southeast via Bridgnorth

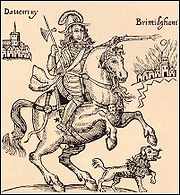

, Birmingham

and Kenilworth

. This had the desired effect.

Parliament, alarmed for its own safety, sent repeated orders to Essex to find the King and bring him to battle. Alarm gave place to determination after the discovery that Charles was enlisting papist

s and seeking foreign aid. The militia of the home counties was called out. A second army under Warwick was formed around the nucleus of the London trained bands; Essex, straining to regain touch with the enemy, reached Kineton

, where he was only 7 miles (11 kilometres) from the King's headquarters at Edgecote, on 22 October.

, the nominal Royalist Commander-in-Chief

. Both sides had marched, widely dispersed in order to forage for supplies, and the rapidity with which the Royalists drew their force back together helped considerably to neutralise Essex's superior numbers.

During the morning of 23 October 1642 the Royalists formed in battle order on the brow of Edge Hill

, facing towards Kineton. Parliamentarian commander Essex found Charles in a strong position with an equal force to his own 14,000, and some of his regiments were still some miles distant. However, when he advanced beyond Kineton, and the Royalists left their strong position and came down to the foot of the hill; Essex had to fight, or risk the starvation of his army in the midst of hostile garrison

s.

After a bloody but inconclusive battle at Edgehill, neither side could claim an outright victory. Furthermore, the prospect of ending the war at a blow, disappeared from view. So far from settling the issue the Battle of Edgehill

After a bloody but inconclusive battle at Edgehill, neither side could claim an outright victory. Furthermore, the prospect of ending the war at a blow, disappeared from view. So far from settling the issue the Battle of Edgehill

was to be the first of a series of pitched battles.

On 24 October Essex retired, leaving Charles to claim victory and to reap its results. The Royalists reoccupied Banbury

and Oxford, and by 28 October Charles was marching down the Thames valley on London. Negotiations were reopened, and a peace party rapidly formed itself in London and Westminster

. Yet, field fortifications sprang up around London, and when Rupert stormed Brentford

and sacked it on 12 November, the trained bands moved out at once and took up a position at Turnham Green

, barring the King's advance.

John Hampden

, with something of the fire and energy of his cousin, Cromwell, urged Essex to turn both flanks of the Royal army via Acton

and Kingston

; experienced professional soldiers, however, urged him not to trust the London men to hold their ground, while the rest manoeuvred. In the opinion of the author of Great Rebellion in the 1911 Britannica Encyclopaedia, Hampden's advice was undoubtedly premature because the manoeuvers that Parliamentary soldiers executed during the Battle of Worcester was not within the power of the Parliamentarians of 1642, and in Napoleon's words: "one only manoeuvres around a fixed point", and the city levies at that time were certainly not, vis-à-vis Rupert's cavalry, a fixed point.

In fact, after a slight cannonade at the Battle of Turnham Green on 13 November, Essex's two-to-one numerical superiority of itself compelled the King to retire to Reading

. The King never again attempted an assault on London.

The field fortifications that were hastily thrown up during the summer of 1642, were supplemented with the Lines of Communication

(the name given for new ring of fortifications around the City of London and the outer boroughs) that were commissioned by Parliament in 1642 and completed in 1643.

, Charles by degrees consolidated his position in the region of Oxford. The city was fortified as a redoubt

for the whole area, and Reading, Wallingford, Abingdon

, Brill

, Banbury and Marlborough constituted a complete defensive ring by creating smaller posts from time to time.

In the North and West, winter campaigns were actively carried on: "It is summer in Yorkshire, summer in Devon

, and cold winter at Windsor", said one of Essex's critics. At the beginning of December 1642, Newcastle crossed the River Tees

, defeated Sir John Hotham

, the Parliamentary commander in the North Riding. He then joined hands with the hard-pressed Royalists at York, establishing himself between that city and Pontefract Castle

. Lord Fairfax of Cameron

and his son Sir Thomas Fairfax

, who commanded for the Parliament in Yorkshire, had to retire to the district between Hull

and Selby

, and Newcastle was now free to turn his attention to the Puritan "clothing towns" of the West Riding

, Leeds

, Halifax

and Bradford

. The townsmen, however, showed a determined front. Sir Thomas Fairfax with a picked body of cavalry rode through Newcastle's lines into the West Riding to help them, and about the end of January 1643, Newcastle gave up the attempt to reduce the towns.

Newcastle continued his march southward, however, and gained ground for the King as far as Newark-on-Trent

, so as to be in touch with the Royalists of Nottinghamshire

, Derbyshire

and Leicestershire

(who, especially about Newark and Ashby-de-la-Zouch

, were strong enough to neutralise the local forces of Parliament), and to prepare the way for the further advance of the army of the north, when the Queen's convoy

should arrive from overseas.

In the west, Hopton and his friends, having obtained a true bill from the grand jury against the Parliamentary disturbers of the peace, placed themselves at the head of the county militia. They drove the rebels from Cornwall, after which they raised a small force for general service and invaded Devonshire in November 1642. Subsequently, a Parliamentary army under the Earl of Stamford

In the west, Hopton and his friends, having obtained a true bill from the grand jury against the Parliamentary disturbers of the peace, placed themselves at the head of the county militia. They drove the rebels from Cornwall, after which they raised a small force for general service and invaded Devonshire in November 1642. Subsequently, a Parliamentary army under the Earl of Stamford

was withdrawn from South Wales to engage Hopton, who had to retire into Cornwall. There, however, the Royalist general was free to employ the militia again, and thus reinforced, he won a victory over a part of Stamford's forces at the Battle of Bradock Down near Liskeard

on 19 January 1643 and resumed the offensive.

About the same time, Hertford, no longer opposed by Stamford, brought over the South Wales Royalists to Oxford. The fortified area around that place was widened by the capture of Cirencester

on 2 February. Gloucester

and Bristol

were now the only important garrisons of the Roundhead

s in the west. In the Midlands, in spite of a Parliamentary victory won by Sir William Brereton at the Battle of Nantwich

on 28 January, the Royalists of Shropshire

, Staffordshire

, and Leicestershire soon extended their influence through Ashby-de-la-Zouch into Nottinghamshire and joined hands with their friends at Newark.

Around Chester, a new Royalist army was being formed under the Lord Byron

, and all the efforts of Sir John Brereton and of Sir John Gell, 1st Baronet

, the leading supporter of Parliament in Derbyshire, were required to hold their own, even before Newcastle's army was added to the list of their enemies. The Lord Brooke

, who commanded for Parliament in Warwickshire

and Staffordshire and was looked on by many as Essex's eventual successor, was killed in besieging Lichfield Cathedral

on 2 March, and, though the cathedral soon capitulated, Gell and Brereton were severely handled in the indecisive Battle of Hopton Heath

near Stafford

on 19 March, and Prince Rupert, after an abortive raid on Bristol

(7 March), marched rapidly northward, storming Birmingham

en route, and recaptured Lichfield Cathedral. He was, however, soon recalled to Oxford to take part in the main campaign.

The position of affairs for Parliament was perhaps at its worst in January. The Royalist successes of November and December, the ever-present dread of foreign intervention, and the burden of new taxation—which Parliament now felt compelled to impose—disheartened its supporters. Disorder broke out in London, and, while the more determined of the rebels began to think of calling in the military assistance of the Scots, the majority were for peace on any conditions.

But soon the position improved somewhat; the Earl of Stamford

in the west and Brereton and Gell in the Midlands, though hard pressed, were at any rate in arms and undefeated, Newcastle had failed to conquer West Riding, and Sir William Waller

, who had cleared Hampshire and Wiltshire

of "malignants," entered Gloucestershire early in March, destroyed a small Royalist force at Highnam

on 24 March, and secured Bristol and Gloucester for Parliament.

Finally, some of Charles's own intrigues opportunely came to light. The waverers, seeing the impossibility of plain dealing with the court, rallied again to the party of resistance. The series of negotiations called by the name of the "Treaty of Oxford

" closed in April, with no more result than those that preceded Edgehill and Turnham Green.

About this time too, following and improving upon the example of Newcastle in the north, Parliament ordered the formation of the celebrated "associations" or groups of counties, banded together by mutual consent for defence. The most powerful and best organised of these was that of the eastern counties (headquartered in Cambridge

), where the danger of attack from the north was near enough to induce great energy in the preparations for meeting it, and at the same time, too distant effectively to interfere with these preparations. Above all, the Eastern Association

was from the first, guided and inspired by Colonel Cromwell.

It was on the rock of local feeling that the King's plan came to grief. Even after the arrival of the Queen and her convoy, Newcastle had to allow her to proceed with a small force, and to remain behind with the main body. This was because of Lancashire and the West Riding, and above all because the port of Hull, in the hands of the Fairfaxes, constituted a menace that the Royalists of the East Riding of Yorkshire

It was on the rock of local feeling that the King's plan came to grief. Even after the arrival of the Queen and her convoy, Newcastle had to allow her to proceed with a small force, and to remain behind with the main body. This was because of Lancashire and the West Riding, and above all because the port of Hull, in the hands of the Fairfaxes, constituted a menace that the Royalists of the East Riding of Yorkshire

refused to ignore.

Hopton's advance too, undertaken without the Cornish levies, was checked in the Battle of Sourton Down

(Dartmoor

) on 25 April. On the same day, Waller captured Hereford

. Essex had already left Windsor to undertake the siege of Reading

. Reading was the most important point in the circle of fortresses round Oxford, which after a vain attempt at relief, surrendered to him on 26 April. Thus the opening operations were unfavourable, not indeed so far as to require the scheme to be abandoned, but at least, delaying the development until the campaigning season was far advanced.

on 13 May 1643. Stamford's army, which had again entered Cornwall, was attacked in its selected position at Stratton

, and practically annihilated by Hopton on 16 May. This brilliant victory was due, above all, to Sir Bevil Grenville

and the lithe Cornishmen. Though they were but 2,400 against 5,400, and destitute of artillery, they stormed "Stamford Hill

", killed 300 of the enemy and captured 1,700 more with all their guns, colours and baggage. Devon was at once overrun by the victors.

Essex's army, for want of material resources, had had to be content with the capture of Reading. A Royalist force under Hertford

and Prince Maurice von Simmern

(Rupert's brother) moved out as far as Salisbury

to hold out a hand to their friends in Devonshire. Waller, the only Parliamentary commander, left in the field in the west, had to abandon his conquests in the Severn valley to oppose the further progress of his intimate friend and present enemy, Hopton.

Early in June, Hertford and Hopton united at Chard

and rapidly moved, with some cavalry skirmishing, towards Bath, where Waller's army lay. Avoiding the barrier of the Mendips

, they moved round via Frome

to the Avon

. But Waller, thus cut off from London and threatened with investment, acted with great skill. Some days of manoeuvres and skirmishing followed, after which Hertford and Hopton found themselves on the north side of Bath, facing Waller's entrenched position on the top of Lansdown Hill. This position, the Royalists stormed on 5 July. The battle of Lansdown was a second Stratton for the Cornishmen, but this time the enemy was of different quality and far differently led. And they had to mourn the loss of Sir Bevil Grenville and the greater part of their whole force.

At dusk, both sides stood on the flat summit of the hill, still firing into one another with such energy as was not yet expended. In the night, Waller drew off his men into Bath. "We were glad they were gone", wrote a Royalist officer, "for if they had not, I know who had within the hour." Next day, Hopton was severely injured by the explosion of a wagon containing the reserve ammunition. The Royalists, finding their victory profitless, moved eastward to Devizes

At dusk, both sides stood on the flat summit of the hill, still firing into one another with such energy as was not yet expended. In the night, Waller drew off his men into Bath. "We were glad they were gone", wrote a Royalist officer, "for if they had not, I know who had within the hour." Next day, Hopton was severely injured by the explosion of a wagon containing the reserve ammunition. The Royalists, finding their victory profitless, moved eastward to Devizes

, closely followed by the enemy.

On 10 July, Sir William Waller

took post on Roundway Down, overlooking Devizes, and captured a Royalist ammunition column from Oxford. On 11 July he came down and invested Hopton's foot in Devizes itself. The Royalist cavalry, Hertford and Maurice with them, rode away towards Salisbury. But although the siege of Devizes was pressed with such vigour that an assault was fixed for the evening of 13 July, the Cornishmen, Hopton directing the defence from his bed, held out stubbornly. On the afternoon of 13 July, Prince Maurice's horsemen appeared on Roundway Down, having ridden to Oxford, picked up reinforcements there, and returned at full speed to save their comrades.

Waller's army tried its best, but some of its elements were of doubtful quality and the ground was all in Maurice's favour. The Battle of Roundway Down

did not last long. The combined attack of the Oxford force from Roundway and of Hopton's men from the town practically annihilated Waller's army. Very soon afterwards, Rupert came up with fresh Royalist forces, and the combined armies moved westward. Bristol, the second port of the kingdom, was their objective. On 26 July, four days from the opening of the siege, it was in their hands. Waller, with the beaten remnant of his army at Bath, was powerless to intervene. The effect of this blow was felt even in Dorset

. Within three weeks of the surrender, Maurice, with a body of fast-moving cavalry, overran that county almost unopposed.

and the Eastern Association. But local interests prevailed again, in spite of Cromwell's presence. After assembling at Nottingham, the Midland rebels quietly dispersed to their several counties on 2 June.

The Fairfaxes were left to their fate. At about the same time, Hull itself narrowly escaped capture by the Queen's forces through the treachery of Sir John Hotham

, the governor, and his son, the commander of the Lincolnshire Parliamentarians. The latter had been placed under arrest at the instance of Cromwell and of Colonel John Hutchinson

, the governor of Nottingham Castle

; he escaped to Hull, but both father and son were seized by the citizens and afterwards executed. More serious than an isolated act of treachery was the far-reaching Royalist plot, that had been detected in Parliament itself for complicity, in which Lord Conway

, Edmund Waller

the poet, and several members of both Houses were arrested.

The safety of Hull was of no avail for the West Riding towns, and the Fairfaxes underwent a decisive defeat at Adwalton Battle of Adwalton (Atherton) Moor

near Bradford on 30 June. After this, by way of Lincolnshire, they escaped to Hull and reorganised the defence of that place. The West Riding perforce submitted.

The Queen herself, with a second convoy and a small army under Lord Henry Jermyn

, soon moved via Newark, Ashby-de-la-Zouch, Lichfield and other Royalist garrisons to Oxford, where she joined her husband on 14 July. But Newcastle (now the Marquess of Newcastle) was not yet ready for his part in the programme. The Yorkshire troops would not march on London while the enemy was master of Hull. By this time, there was a solid barrier between the royal army of the north and the capital. Roundway Down and Adwalton Moor were not, after all, destined to be fatal, though peace riots in London, dissensions in the Houses, and quarrels amongst the generals were their immediate consequences. A new factor had arisen in the war — the Eastern Association

.

had already intervened to help in the siege of Reading

and had sent troops to the abortive gathering at Nottingham, besides clearing its own ground of "malignants." From the first, Cromwell was the dominant influence.

Fresh from Edgehill, he had told Hampden: "You must get men of a spirit that is likely to go as far as gentlemen will go", not "old decayed serving-men, tapsters and such kind of fellows to encounter gentlemen that have honour and courage and resolution in them". In January 1643, he had gone to his own county to "raise such men as had the fear of God before them, and made some conscience of what they did". These men, once found, were willing, for the cause, to submit to a rigorous training and an iron discipline such as other troops, fighting for honour only or for profit only, could not be brought to endure. The result was soon apparent.

As early as 13 May, Cromwell's regiment of horse, recruited from the horse-loving yeomen of the eastern counties, demonstrated its superiority in the field, in a skirmish near Grantham

. In the irregular fighting in Lincolnshire, during June and July (which was on the whole unfavourable to the Parliament), as previously in pacifying the Eastern Association itself, these Puritan troopers distinguished themselves by long and rapid marches that may bear comparison with almost any in the history of the mounted arm. When Cromwell's second opportunity came at Gainsborough

on 28 July, the "Lincolneer" horse who were under his orders were fired by the example of Cromwell's own regiment. Cromwell, directing the whole with skill, and above all with energy, utterly routed the Royalist horse and killed their general, Charles Cavendish

.

In the meantime the army of Essex had been inactive. After the fall of Reading, a serious epidemic of sickness had reduced it to impotence. On 18 June, the Parliamentary cavalry was routed, and John Hampden mortally wounded at Chalgrove Field

near Chiselhampton

. When at last Essex, having obtained the desired reinforcements, moved against Oxford from the Aylesbury

side, he found his men demoralised by inaction.

Before the menace of Rupert's cavalry, to which he had nothing to oppose, Essex withdrew to Bedfordshire

in July. He made no attempt to intercept the march of the Queen's convoys, permitting the Oxford army, which he should have held fast, to intervene effectually in the Midlands, the west, and the south-west. Waller might well complain that Essex, who still held Reading and the Chilterns, had given him neither active nor passive support in the critical days, preceding Roundway Down. Still, only a few voices were raised to demand his removal, and he was shortly to have an opportunity of proving his skill and devotion in a great campaign and a great battle.

The centre and the right of the three Royalist armies had for a moment (Roundway to Bristol) united to crush Waller, but their concentration was short-lived. Plymouth

was to Hopton's men, what Hull was to Newcastle's. They would not march on London until the menace to their homes was removed. Further, there were dissensions among the generals, which Charles was too weak to crush. Consequently, the original plan reappeared: The main Royalist army was to operate in the centre, Hopton's (now Maurice's) on the right, Newcastle on the left towards London. While waiting for the fall of Hull and Plymouth, Charles naturally decided to make the best use of his time by reducing Gloucester, the one great fortress of Parliament in the west.

On 26 August 1643, all being ready, Essex started. Through Aylesbury and round the north side of Oxford to Stow-on-the-Wold

, the army moved resolutely, not deterred by want of food and rest, or by the attacks of Rupert's and Wilmot's horse on its flank. On 5 September, just as Gloucester was at the end of its resources, the siege of Gloucester

was suddenly raised. The Royalists drew off to Painswick

, for Essex had reached Cheltenham

and the danger was over; the field armies, being again face to face, and free to move. There followed a series of skilful manoeuvres in the Severn and Avon

valleys. At the end, the Parliamentary army gained a long start on its homeward road via Cricklade

, Hungerford

and Reading.

But the Royalist cavalry under Rupert, followed rapidly by Charles and the main body from Evesham, strained every nerve to head off Essex at Newbury

. After a sharp skirmish on Aldbourne Chase on 18 September, they succeeded. On 19 September, the whole Royal army was drawn up, facing west, with its right on Newbury, and its left on Enborne Heath. Essex's men knew that evening that they would have to break through by force, there being no suggestion of surrender.

On the left wing, in spite of the Royalist counter-strokes, the attack had the best of it, capturing field after field, and thus gradually gaining ground to the front. Here, Viscount Falkland was killed. On the Reading road itself Essex did not succeed in deploying on to the open ground on Newbury Wash, but victoriously repelled the royal horse when it charged up to the lanes and hedges held by his foot. On the extreme right of the Parliamentary army, which stood in the open ground of Enborne Heath, took place a famous incident. Here, two of the London regiments, fresh to war as they were, were exposed to a trial as severe as that which broke down the veteran Spanish

infantry at Rocroi

in this same year. Rupert and the Royalist horse, again and again, charged up to the squares of pikes. Between each charge, his guns tried to disorder the Londoners, but it was not until the advance of the royal infantry that the trained bands retired, slowly and in magnificent order, to the edge of the heath. The result was that Essex's army had fought its hardest, and failed to break the opposing line. But the Royalists had suffered so heavily, and above all, the valour displayed by the Parliamentarians had so profoundly impressed them, that they were glad to give up the disputed road, and withdraw into Newbury. Essex thereupon pursued his march. Reading was reached on 22 September 1643 after a small rearguard skirmish at Aldermaston

, and so ended the First Battle of Newbury

, one of the most dramatic episodes of English history.

had commenced. The Eastern Association forces under Manchester

promptly moved up into Lincolnshire, the foot besieging Lynn (which surrendered on 16 September 1643) while the horse rode into the northern part of the county to give a hand to the Fairfaxes. Fortunately the sea communications of Hull were open.

On 18 September, part of the cavalry in Hull was ferried over to Barton

, and the rest under Sir Thomas Fairfax

went by sea to Saltfleet

a few days later, the whole joining Cromwell near Spilsby

. In return, the old Lord Fairfax, who remained in Hull, received infantry reinforcements and a quantity of ammunition and stores from the Eastern Association.

On 11 October, Cromwell and Fairfax together won a brilliant cavalry action at the Battle of Winceby

, driving the Royalist horse in confusion before them to Newark. On the same day, Newcastle's army around Hull, which had suffered terribly from the hardships of continuous siege work, was attacked by the garrison. They were so severely handled that the siege was given up the next day. Later, Manchester retook Lincoln and Gainsborough. Thus Lincolnshire, which had been almost entirely in Newcastle's hands before he was compelled to undertake the siege of Hull, was added, in fact as well as in name, to the Eastern Association.

Elsewhere, in the reaction after the crisis of Newbury, the war languished. The city regiments went home, leaving Essex too weak to hold Reading. The Royalists reoccupied it on 3 October. At this, the Londoners offered to serve again. They actually took part in a minor campaign around Newport Pagnell

, where Rupert was attempting to fortify, as a menace to the Eastern Association and its communications with London.

Essex was successful in preventing this, but his London regiments again went home. Sir William Waller's new army in Hampshire

failed lamentably in an attempt on Basing House on 7 November, the London-trained bands, deserting en bloc. Shortly afterwards, on 9 December, Arundel

surrendered to a force under Sir Ralph, now Lord Hopton.

, his greatest and most faithful Scottish lieutenant, who wished to give the Scots employment for their army at home. Only ten days after the "Irish Cessation," Parliament at Westminster swore to the Solemn League and Covenant

, and the die was cast.

It is true that even a semblance of Presbyterian theocracy

put the "Independents" on their guard, and definitely raised the question of freedom of conscience. Secret negotiations were opened between the Independents and Charles on that basis. However, they soon discovered that the King was merely using them as instruments to bring about the betrayal of Aylesbury and other small rebel posts. All parties found it convenient to interpret the Covenant liberally for the present. At the beginning of 1644, the Parliamentary party showed so united a front that even Pym's death, on 8 December 1643, hardly affected its resolution to continue the struggle.

The troops from Ireland, thus obtained at the cost of an enormous political blunder, proved to be untrustworthy after all. Those serving in Hopton's army were "mutinous and shrewdly infected with the rebellious humour of England". When Waller's Londoners surprised and routed a Royalist detachment at Alton

on 13 December 1643, half the prisoners took the Covenant

.

In Lancashire, as in Cheshire

, Staffordshire, Nottinghamshire, and Lincolnshire, the cause of Parliament was in the ascendant. Resistance revived in the West Riding towns, Lord Fairfax was again in the field in the East Riding of Yorkshire

, and even Newark was closely besieged by Sir John Meldrum

. More important news came in from the north. The advanced guard of the Scottish army had passed the Tweed

on 19 January, and Newcastle, with the remnant of his army, would soon be attacked in front and rear at once.

border, and gathering up garrisons and recruits snowball-wise as he marched, he went first to Cheshire to give a hand to Byron

, and then, with the utmost speed, he made for Newark. On 20 March 1644, he bivouacked at Bingham

, and on the 21st, he not only relieved Newark

but routed the besiegers' cavalry. On the 22nd, Meldrum's position was so hopeless that he capitulated on terms. But, brilliant soldier as he was, the prince was unable to do more than raid a few Parliamentary posts around Lincoln. After that, he had to return his borrowed forces to their various garrisons, and go back to Walesladen, indeed with captured pikes and muskets, to raise a permanent field army.

But Rupert could not be in all places at once. Newcastle was clamorous for aid. In Lancashire, only the countess of Derby, in Lathom House, held out

for the King. Her husband pressed Rupert to go to her relief. Once, too, the prince was ordered back to Oxford to furnish a travelling escort for the queen, who shortly after this, gave birth to her youngest child and returned to France

. The order was countermanded within a few hours, it is true, but Charles had good reason for avoiding detachments from his own army.

On 29 March, Hopton had undergone a severe defeat at Cheriton

, near New Alresford

. In the preliminary manoeuvres, and in the opening stages of the battle, the advantage lay with the Royalists. The Patrick, Earl of Forth

, who was present, was satisfied with what had been achieved, and tried to break off the action. But Royalist indiscipline ruined everything. A young cavalry colonel, charged in defiance of orders. A fresh engagement opened, and at the last moment, Waller snatched a victory out of defeat. Worse than this was the news from Yorkshire and Scotland. Charles had at last assented to Montrose's plan and promised him a marquessate. The first attempt to raise the Royalist standard in Scotland, however, gave no omen of its later triumphs.

In Yorkshire, Sir Thomas Fairfax, advancing from Lancashire through the West Riding, joined his father. Selby was stormed on 11 April and thereupon, Newcastle, who had been manoeuvring against the Scots in Durham

, hastily drew back. He sent his cavalry away, and shut himself up with his foot in York. Two days later, the Scottish general, Alexander Leslie, Lord Leven

, joined the Fairfaxes and prepared to invest that city.

," which directed the military and civil policy of the allies after the fashion of a modern cabinet, was to combine Essex's and Manchester's armies in an attack upon the King's army. Aylesbury was appointed as the place of concentration. Waller's troops were to continue to drive back Hopton and to reconquer the west, Fairfax and the Scots, to invest Newcastle's army.

In the Midlands, Brereton and the Lincolnshire rebels could be counted upon to neutralise the one Byron, and the others, the Newark Royalists. But Waller, once more deserted by his trained bands, was unable to profit by his victory of Cheriton, and retired to Farnham

. Manchester, too, was delayed because the Eastern Association was still suffering from the effects of Rupert's Newark exploit. Lincoln

, abandoned by the rebels on that occasion, was not reoccupied till 6 May. Moreover, Essex found himself compelled to defend his conduct and motives to the "Committee of Both Kingdoms," and as usual, was straitened for men and money.

But though there were grave elements of weakness on the other side, the Royalists considered their own position to be hopeless. Prince Maurice was engaged in the fruitless siege of Lyme Regis

. Gloucester was again a centre of activity and counterbalanced Newark, and the situation in the north was practically desperate. Rupert himself came to Oxford on 25 April 1644 to urge that his new army should be kept free to march to aid Newcastle. This was because Newscastle's army was now threatened, owing to the abandonment of the enemy's original plan by Manchester, as well as Fairfax and Leven.

There was no further talk of the concentric advance of three armies on London. The fiery prince and the methodical Earl of Forth (now honoured with the Earldom of Brentford

) were at one, at least, in recommending that the Oxford area, with its own garrison and a mobile force, should be the pivot of the field armies' operations. Rupert, needing above all, adequate time for the development of the northern offensive, was not in favour of abandoning any of the barriers to Essex's advance. Brentford, on the other hand, thought it advisable to contract the lines of defence, and Charles, as usual undecided, agreed to Rupert's scheme and executed Brentford's. Reading, therefore, was dismantled early in May, and Abingdon given up shortly afterwards.

was no sooner evacuated than on 26 May 1644, Waller's and Essex's armies united there – still, unfortunately for their cause, under separate commanders. Edmund Ludlow

joined Waller at Abingdon to place Oxford under siege. From Abingdon, Essex moved direct on Oxford. Waller moved towards Wantage

, where he could give a hand to Edward Massey, the energetic governor of Gloucester.

Affairs seemed so bad in the west (Maurice, with a whole army was still vainly besieging the single line of low breastwork

s that constituted the fortress of Lyme Regis

) that the King dispatched Hopton to take charge of Bristol. Nor were things much better at Oxford. The barriers of time and space, and the supply area had been deliberately given up to the enemy. Charles was practically forced to undertake extensive field operations, with no hope of success, save in consequence of the enemy's mistakes.

The enemy, as it happened, did not disappoint him. The King, probably advised by Brentford, conducted a skilful war of manoeuvre in the area defined by Stourbridge

, Gloucester, Abingdon and Northampton. At the end, Essex marched off into the west with most of the general service troops to repeat at Lyme Regis, his Gloucester exploit of 1643, leaving Waller to the secondary work of keeping the King away from Oxford and reducing that fortress.

At one moment, indeed, Charles (then in Bewdley

) rose to the idea of marching north to join Rupert and Newcastle, but he soon made up his mind to return to Oxford. From Bewdley, therefore, he moved to Buckingham

, the distant threat on London, producing another evanescent citizen army drawn from six counties under Major-General Browne. Waller followed him closely. When the King turned upon Browne's motley host, Waller appeared in time to avert disaster, and the two armies worked away to the upper Cherwell

.

Brentford and Waller were excellent strategists of the 17th century type, and neither would fight a pitched battle without every chance in his favour. Eventually on 29 June, the Royalists were successful in a series of minor fights about Cropredy Bridge. The result was, in accordance with continental custom, admitted to be an important victory, though Waller's main army drew off unharmed. In the meantime, on 15 June, Essex had relieved Lyme Regis and occupied Weymouth, and was preparing to go farther. The two rebel armies were now indeed separate. Waller had been left to do as best he could, and a worse fate was soon to overtake the cautious earl.

was plundered on the 25th, and the besiegers of Lathom House, utterly defeated at Bolton

on 28 May. Soon afterwards, he received a large reinforcement under General George Goring

, which included 5,000 of Newcastle's cavalry.

The capture of the almost defenceless town of Liverpool

, undertaken as usual to allay local fears, did not delay Rupert more than three or four days. He then turned towards the Yorkshire border with greatly augmented forces. On 14 June, he received a despatch from the King, the gist of which was that there was a time-limit imposed on the northern enterprise. If York were lost or did not need his help, Rupert was to make all haste southward via Worcester. "If York be relieved and you beat the rebels' armies of both kingdoms, then, but otherways not, I may possibly make a shift upon the defensive to spin out time until you come to assist me."

Charles did manage to spin out time. But it was of capital importance that Rupert had to do his work upon York and the allied army in the shortest possible time. According to the despatch, there were only two ways of saving the royal cause, "having relieved York by beating the Scots", or marching with all speed to Worcester. Rupert's duty, interpreted through the medium of his temperament, was clear enough. Newcastle still held out, his men having been encouraged by a small success on 17 June, and Rupert reached Knaresborough

on the 30th.

At once, Leven, Fairfax and Manchester broke up the siege of York and moved out to meet him. But the prince, moving still at high speed, rode round their right flank via Boroughbridge

and Thornton Bridge, and entered York on the north side. Newcastle tried to dissuade Rupert from fighting, but his record as a general was scarcely convincing as to the value of his advice. Rupert curtly replied that he had orders to fight, and the Royalists moved out towards Marston Moor on the morning of 2 July 1644.

The Parliamentary commanders, fearing a fresh manoeuvre, had already begun to retire towards Tadcaster

, but as soon as it became evident that a battle was impending, they turned back. The battle of Marston Moor began at about four in the afternoon. It was the first real trial of strength between the best elements on either side, and it ended before night with the complete victory of the Parliamentary armies. The Royalist cause in the north collapsed once and for all. Newcastle fled to the continent, and only Rupert, resolute as ever, extricated 6,000 cavalry from the debacle, and rode away whence he had come, still the dominant figure of the war.

The Yorkshire troops proceeded to conquer the isolated Royalist posts in their county. The Scots marched off to besiege Newcastle-on-Tyne and to hold in check a nascent Royalist army in Westmorland

. Rupert, in Lancashire, they neglected entirely. Manchester and Cromwell, already estranged, marched away into the Eastern Association. There, for want of an enemy to fight, their army was forced to be idle. Cromwell, and the ever-growing Independent element, quickly came to suspect their commander of lukewarmness in the cause. Waller's army, too, was spiritless and immobile.

On 2 July 1644, despairing of the existing military system, Cromwell made to the "Committee of Both Kingdoms," the first suggestion of the New Model Army

. "My lords," he wrote, "till you have an army merely your own, that you may command, it is... impossible to do anything of importance." Browne's trained band army was perhaps the most ill-behaved of all. Once, the soldiers attempted to murder their own general. Parliament, in alarm, set about the formation of a new general service force on 12 July. Meanwhile, both Waller's and Browne's armies, at Abingdon and Reading respectively, ignominiously collapsed by mutiny and desertion.

It was evident that the people at large, with their respect for the law and their anxiety for their own homes, were tired of the war. Only those men, such as Cromwell, who has set their hearts on fighting out the quarrel of conscience, kept steadfastly to their purpose. Cromwell himself had already decided that the King himself must be deprived of his authority, and his supporters were equally convinced. But they were relatively few. Even the Eastern Association trained bands had joined in the disaffection in Waller's army. The unfortunate general's suggestion of a professional army, with all its dangers, indicated the only means of enforcing a peace, such as Cromwell and his friends desired.

There was this important difference, however, between Waller's idea and Cromwell's achievement that the professional soldiers of the New Model were disciplined, led, and in all things, inspired by "godly" officers. Godliness, devotion to the cause, and efficiency were indeed the only criteria Cromwell applied in choosing officers. Long before this, he had warned the Scottish major-general, Lawrence Crawford, that the precise colour of a man's religious opinions mattered nothing, compared with his devotion to them. He had told the committee of Suffolk

:

If "men of honour and birth" possessed the essentials of godliness, devotion, and capacity, Cromwell preferred them. As a matter of fact, only seven out of 37 of the superior officers of the original New Model were not of gentle birth.

Their state reflected the general languishing of the war spirit on both sides, not on one only, as Charles discovered when he learned that Lord Wilmot, the lieutenant-general of his horse, was in correspondence with Essex. Wilmot was of course placed under arrest, and was replaced by the dissolute General Goring. But it was unpleasantly evident that even gay cavaliers of the type of Wilmot had lost the ideals for which they fought. Wilmot had come to believe that the realm would never be at peace while Charles was King.

Henceforward, it will be found that the Royalist foot, now a thoroughly professional force, is superior in quality to the once superb cavalry, and not merely because its opportunities for plunder, etc. are more limited. Materially, however, the immediate victory was undeniably with the Royalists. After a brief period of manoeuvre, the Parliamentary army, now far from Plymouth, found itself surrounded and starving at Lostwithiel

, on the Fowey river, without hope of assistance.

The horse cut its way out through the investing circle of posts. Essex himself escaped by sea, but Major-General Philip Skippon

, his second in command, had to surrender with the whole of the foot on 2 September 1644. The officers and men were allowed to go free to Portsmouth

, but their arms, guns and munitions were the spoil of the victors.

There was now no trustworthy field force in arms for Parliament south of the Humber

. Even the Eastern Association army was distracted by its religious differences, which had now at last come definitely to the front and absorbed the political dispute in a wider issue. Cromwell already proposed to abolish the peerage, the members of which were inclined to make a hollow peace. He had ceased to pay the least respect to his general, Manchester, whose scheme for the solution of the quarrel was an impossible combination of Charles and Presbyterianism. Manchester, for his part, sank into a state of mere obstinacy. He refused to move against Rupert, or even to besiege Newark, and actually threatened to hang Colonel Lilburne for capturing a Royalist castle without orders.

(near Basingstoke

) were in danger of capture. Waller, who had organised a small force of reliable troops, had already sent cavalry into Dorsetshire with the idea of assisting Essex. He now came himself with reinforcements to prevent, so far as lay in his power, the King's return to the Thames valley.

Charles was accompanied, of course, only by his permanent forces and by parts of Prince Maurice's and Hopton's armies. The Cornish levies had, as usual, scattered as soon as the war receded from their borders. Manchester slowly advanced to Reading, while Essex gradually reorganised his broken army at Portsmouth. Waller, far out to the west at Shaftesbury

, endeavored to gain the necessary time and space for a general concentration in Wiltshire

, where Charles would be far from Oxford and Basing and, in addition, outnumbered by two to one.

But the work of rearming Essex's troops proceeded slowly for want of money. Manchester peevishly refused to be hurried, either by his more vigorous subordinates or by the "Committee of Both Kingdoms", saying that the army of the Eastern Association was for the guard of its own employers, and not for general service. He pleaded the renewed activity of the Newark Royalists as his excuse, forgetting that Newark would have been in his hands ere this, had he chosen to move thither, instead of lying idle for two months.

As to the higher command, when the three armies at last united, a council of war, consisting of three army commanders, several senior officers, and two civilian delegates from the Committee, was constituted. When the vote of the majority had determined what was to be done, Essex, as lord general of the Parliament's first army, was to issue the necessary orders for the whole. Under such conditions, it was unlikely that Waller's hopes of a great battle at Shaftesbury would be realised.

On 8 October 1644, Waller fell back, the royal army following him step by step and finally reaching Whitchurch

on 10 October. Manchester arrived at Basingstoke on the 17th, Waller on the 19th, and Essex on the 21st. Charles had found that he could not relieve Basing (a mile or two from Basingstoke), without risking a battle with the enemy between himself and Oxford. As his intent was to "spin out time" until Rupert returned from the north, he therefore took the Newbury road and relieved Donnington Castle

, near Newbury, on the 22nd.

Three days later, Banbury too was relieved by a force that could now be spared from the Oxford garrison. But for once, the council of war on the other side was for fighting a battle. The Parliamentary armies, their spirits revived by the prospect of action, and by the news of the fall of Newcastle-on-Tyne and the defeat of a sally from Newark, marched briskly. On 26 October, they appeared north of Newbury on the Oxford road. Like Essex in 1643, Charles found himself headed off from the shelter of friendly fortresses. Beyond this fact there is little similarity between the two battles of Newbury, for the Royalists, in the first case, merely drew a barrier across Essex's path. On the present occasion, the eager Parliamentarians made no attempt to force the King to attack them. They were well content to attack him in his chosen position themselves, especially as he was better off for supplies and quarters than they.

, fought on 27 October 1644, was the first great manoeuvre-battle, distinct from the "pitched" battle, of the civil war. A preliminary reconnaissance

by the Parliamentary leaders (Essex was not present, owing to illness) established the fact that the King's infantry held a strong line of defence behind the Lambourn

brook, from Shaw

(inclusive) to Donnington (exclusive). Shaw House

and adjacent buildings were being held as an advanced post. In rear of the centre, in open ground just north of Newbury, lay the bulk of the royal cavalry. In the left rear of the main line, and separated from it by more than a thousand yards, lay Prince Maurice's corps at Speen

, and advanced troops on the high ground, west of that village. Donnington Castle, under its energetic governor, Sir John Boys, however, formed a strong post covering this gap with artillery fire.

The Parliamentary leaders had no intention of flinging their men away in a frontal attack on the line of the Lambourn. A flank attack from the east side could hardly succeed, owing to the obstacle presented by the confluence of the Lambourn and the Kennet

. Hence, they decided on a wide turning movement via Chieveley

, Winterbourne

and Wickham Heath

, against Prince Maurice's position. The decision, daring and energetic as it was, led only to a moderate success, for reasons that will appear. The flank march, out of range of the castle, was conducted with punctuality and precision.

The troops composing it were drawn from all three armies, and led by the best fighting generals, Waller, Cromwell, and Essex's subordinates, Balfour and Skippon. Manchester, at Clay Hill, was to stand fast until the turning movement had developed, and to make a vigorous holding attack on Shaw House, as soon as Waller's guns were heard at Speen. But there was no commander-in-chief to co-ordinate the movements of the two widely separated corps, and consequently no co-operation.

Waller's attack was not unexpected, and Prince Maurice had made ready to meet him. Yet, the first rush of the rebels carried the entrenchments of Speen Hill. Speen itself, though stoutly defended, fell into their hands within an hour, Essex's infantry recapturing here some of the guns they had had to surrender at Lostwithiel. But meantime, Manchester, in spite of the entreaties of his staff, had not stirred from Clay Hill. He had already made one false attack early in the morning, and been severely handled, he was aware of his own deficiencies as a general.

A year before this, Manchester would have asked for and acted upon the advice of a capable soldier, such as Cromwell or Crawford. Now, however, his mind was warped by a desire for peace on any terms, and he sought only to avoid defeat, pending a happy solution of the quarrel. Those who sought to gain peace through victory were, meanwhile, driving Maurice back from hedge to hedge towards the open ground at Newbury. But every attempt to emerge from the lanes and fields was repulsed by the royal cavalry, and indeed, by every available man and horse. Charles's officers had gauged Manchester's intentions, and almost stripped the front of its defenders to stop Waller's advance. Nightfall put an end to the struggle around Newbury, and then too late, Manchester ordered the attack on Shaw House. It failed completely, in spite of the gallantry of his men, and darkness being then complete, it was not renewed.

In its general course, the battle closely resembled that of the battle of Freiburg

, fought the same year on the Rhine. But, if Waller's part in the battle corresponded in a measure to Turenne's, Manchester was unequal to playing the part of Conde. Consequently, the results, in the case of the French, who won by three days of hard fighting, and even then comparatively small, were in the case of the English, practically nil. During the night, the royal army quietly marched away through the gap between Waller's and Manchester's troops. The heavy artillery and stores were left in Donnington Castle. Charles himself with a small escort rode off to the north-west to meet Rupert, and the main body gained Wallingford unmolested.

An attempt at pursuit was made by Waller and Cromwell, with all the cavalry they could lay hands on. It was, however, unsupported, for the council of war had decided to content itself with besieging Donnington Castle. A little later, after a brief and half-hearted attempt to move towards Oxford, it referred to the Committee for further instructions. Within the month, Charles, having joined Rupert at Oxford and made him general of the Royalist forces vice Brentford, reappeared in the neighbourhood of Newbury.

Donnington Castle was again relieved on 9 November, under the eyes of the Parliamentary army, which was in such a miserable condition that even Cromwell was against fighting. Some manoeuvres followed, in the course of which, Charles relieved Basing House. The Parliamentary armies fell back, not in the best order, to Reading. The season for field warfare was now far spent, and the royal army retired to enjoy good quarters and plentiful supplies around Oxford.

The first "self-denying ordinance

" was moved on 9 December 1644, and provided that "no member of either house shall have or execute any office or command...", etc. This was not accepted by the Lords. In the end, a second "self-denying ordinance" was agreed to on 3 April 1645, whereby all the persons concerned were to resign, but without prejudice to their reappointment. Simultaneously with this, the formation of the New Model was at last definitely taken into consideration. The last exploit of Sir William Waller, who was not re-employed after the passing of the ordinance, was the relief of Taunton

, then besieged by General Goring's army. Cromwell served as his lieutenant-general on this occasion. We have Waller's own testimony that he was, in all things, a wise, capable and respectful subordinate. Under a leader of the stamp of Waller, Cromwell was well satisfied to obey, knowing the cause to be in good hands.

The new plan, suggested probably by Rupert, had already been tried with strategic success in the summer campaign of 1644. It consisted essentially in using Oxford as the centre of a circle and striking out radially at any favourable target — "manoeuvring about a fixed point," as Napoleon called it.

It was significant of the decline of the Royalist cause that the "fixed point" had been, in 1643, the King's field army, based indeed on its great entrenched camp, Banbury–Cirencester–Reading–Oxford, but free to move and to hold the enemy, wherever met. But now, it was the entrenched camp itself, weakened by the loss or abandonment of its outer posts, and without the power of binding the enemy, if they chose to ignore its existence, that conditioned the scope and duration of the single remaining field army's enterprises.

opened on 29 January 1645 at Uxbridge

(by the name of which place, they are known to history) and occupied the attention of the Scots and their Presbyterian friends. The rise of Independency, and of Cromwell, was a further distraction. The Lords and Commons were seriously at variance over the new army, and the Self-denying Ordinance.

In February, a fresh mutiny

in Waller's command struck alarm into the hearts of the disputants. The "treaty" of Uxbridge came to the same end as the treaty of Oxford in 1643, and a settlement as to army reform was achieved on 15 February. Though it was only on 25 March that the second and modified form of the ordinance was agreed to by both Houses, Sir Thomas Fairfax and Philip Skippon (who were not members of parliament) had been approved as lord general and major-general (of the infantry) respectively of the new army as early as 21 January. The post of lieutenant-general and cavalry commander was for the moment left vacant, but there was little doubt as to who would eventually occupy it.

Early in April 1645, Essex, Manchester, and Waller resigned their commissions in anticipation of the passing by Parliament of the self-denying ordinance. Those in the forces who were not embodied in the new army, were sent to do local duties, for minor armies were still maintained — General Sydnam Poyntz's

in the north Midlands; General Edward Massey's in the Severn valley; a large force in the Eastern Association; General Browne's in Buckinghamshire

, etc., — besides the Scots in the north.

The New Model originally consisted of 14,400 foot and 7,700 horse and dragoon

s. Of the infantry, only 6,000 came from the combined armies, the rest being new recruits furnished by the 'press'—The Puritans had by now almost entirely disappeared from the ranks of the infantry, but the officers and sergeants and the troopers of the horse were the sternest Puritans of all (the survivors of three years of disheartening war). Thus, there was considerable trouble during the first months of Fairfax's command, and discipline had to be enforced with unusual sternness. As for the enemy, Oxford was openly contemptuous of "the rebels' new brutish general" and his men, who seemed hardly likely to succeed, where Essex and Waller had failed. But the effect of Parliament having "an army all its own" was soon to be apparent.

, the young prince of Wales

was sent with Hyde

(later, Earl of Clarendon

), Hopton, and others as his advisers. General (Lord) Goring

, however, now in command of the Royalist field forces in this quarter, was truculent, insubordinate and dissolute. On the rare occasions when he did his duty, however, he did display a certain degree of skill and leadership, and the influence of the prince's counsellors was but small.

As usual, operations began with the sieges, necessary to conciliate local feeling. Plymouth and Lyme Regis were blocked up, and Taunton again invested. The reinforcement thrown into the last place by Waller and Cromwell was dismissed by Blake (then a colonel in command of the fortress (afterwards, the great admiral

of the Commonwealth

). After many adventures, Blake rejoined Waller and Cromwell. The latter generals, who had not yet laid down their commissions, then engaged Goring for some weeks. Neither side had infantry or artillery, and both found subsistence difficult in February and March. In a country that had been fought over for the two years past, no results were to be expected. Taunton still remained unrelieved, and Goring's horse still rode all over Dorsetshire, when the New Model at last took the field.

and Lancashire, the Royalist horse, as ill-behaved even as Goring's men, were directly responsible for the ignominious failure with which the King's main army began its year's work. Prince Maurice was joined at Ludlow

by Rupert and part of his Oxford army, early in March 1645. The brothers drove off Brereton from the siege of Beeston Castle

, and relieved the pressure on Lord Byron in Cheshire. So great was the danger of Rupert's again invading Lancashire and Yorkshire that all available forces in the north, English and Scots, were ordered to march against him. But at this moment the prince was called back to clear his line of retreat on Oxford.

The Herefordshire

and Worcestershire

peasantry, weary of military exactions, were in arms. Though they would not join Parliament, and for the most part dispersed after stating their grievances, the main enterprise was wrecked. This was but one of many ill-armed crowds, the "Clubmen

" as they were called, that assembled to enforce peace on both parties. A few regular soldiers were sufficient to disperse them in all cases, but their attempt to establish a third party in England was morally as significant as it was materially futile.

The Royalists were now fighting with the courage of despair. Those who still fought against Charles did so with the full determination to ensure the triumph of their cause, and with the conviction that the only possible way was the annihilation of the enemy's armed forces. The majority, however, were so weary of the war that the Earl of Manchester's Presbyterian royalism, which contributed so materially to the prolongation of the struggle, would probably have been accepted by four-fifths of all England as the basis of a peace. It was, in fact, in the face of almost universal opposition, that Fairfax and Cromwell and their friends at Westminster guided the cause of their weaker comrades to complete victory.

, the Scottish army in England had been called upon to detach a large force to deal with Montrose. But this time there was no Royalist army in the north to provide infantry and guns for a pitched battle. Rupert had perforce to wait near Hereford till the main body, and in particular the artillery train, could come from Oxford and join him.

It was on the march of the artillery train to Hereford that the first operations of the New Model centred. The infantry was not yet ready to move, in spite of all Fairfax's and Skippon's efforts. It became necessary to send the cavalry, by itself, to prevent Rupert from gaining a start. Cromwell, then under Waller's command, had come to Windsor to resign his commission, as required by the Self-denying Ordinance. Instead, he was placed at the head of a brigade of his own old soldiers, with orders to stop the march of the artillery train.

On 23 April 1645, Cromwell started from Watlington

, north-westward. At dawn on the 24th, he routed a detachment of Royalist horse at Islip

. On the same day, though he had no guns and only a few firearms in the whole force, he terrified the governor of Bletchingdon

House into surrender. Riding thence to Witney

, Cromwell won another cavalry fight at Bampton-in-the-Bush on the 27th, and attacked Faringdon House, though without success, on 29 April. From there, he marched at leisure to Newbury. He had done his work thoroughly. He had demoralised the Royalist cavalry, and, above all, had carried off every horse on the countryside. To all Rupert's entreaties, Charles could only reply that the guns could not be moved till the 7 May, and he even summoned Goring's cavalry from the west to make good his losses.

on the one side, and Charles, Rupert, and Goring, on the other, held different views. On 1 May 1645, Fairfax, having been ordered to relieve Taunton, set out from Windsor for the long march to that place. Meeting Cromwell at Newbury on 2 May, he directed the lieutenant-general to watch the movements of the King's army. He himself marched on to Blandford, which he reached on 7 May. Thus, Fairfax and the main army of Parliament were marching away in the west, while Cromwell's detachment was left, as Waller had been left the previous year, to hold the King, as best he could.

On the very evening that Cromwell's raid ended, the leading troops of Goring's command destroyed part of Cromwell's own regiment near Faringdon

. On 3 May Rupert and Maurice appeared with a force of all arms at Burford

. Yet the "Committee of Both Kingdoms", though aware on 29 May of Goring's move, only made up its mind to stop Fairfax on the 3rd, and did not send off orders till the 5th. These orders were to the effect that a detachment was to be sent to the relief of Taunton, and that the main army was to return. Fairfax gladly obeyed, even though a siege of Oxford

, and not the enemy's field army, was the objective assigned him. But long before he came up to the Thames valley, the situation was again changed.

Rupert, now in possession of the guns and their teams, urged upon his uncle, the resumption of the northern enterprise, calculating that with Fairfax in Somerset

shire, Oxford was safe. Charles accordingly marched out of Oxford on the 7th towards Stow-on-the-Wold, on the very day as it chanced, that Fairfax began his return march from Blandford. But Goring and most of the other generals were for a march into the west, in the hope of dealing with Fairfax as they had dealt with Essex in 1644. The armies therefore parted, as Essex and Waller had parted at the same place in 1644. Rupert and the King were to march northward, while Goring was to return to his independent command in the west.

Rupert, not unnaturally, wishing to keep his influence with the King and his authority as general of the King's army, unimpaired by Goring's notorious indiscipline, made no attempt to prevent the separation, which in the event proved wholly unprofitable. The flying column from Blandford relieved Taunton long before Goring's return to the west. Colonel Weldon and Colonel Graves, its commanders, set him at defiance even in the open country. As for Fairfax, he was out of Goring's reach, preparing for the siege of Oxford.

In reality, the Committee seems to have been misled by false information to the effect that Goring and the governor of Oxford were about to declare for Parliament. Had they not dispatched Fairfax to the relief of Taunton in the first instance, the necessity for such intrigues would not have arisen. However, Fairfax obeyed orders, invested Oxford, and so far as he was able, without a proper siege train, besieged it for two weeks, while Charles and Rupert ranged the Midlands unopposed.

At the end of that time came news, so alarming that the Committee hastily abdicated their control over military operations, and gave Fairfax a free hand. "Black Tom" gladly and instantly abandoned the siege and marched northward to give battle to the King. Meanwhile, Charles and Rupert were moving northward. On 11 May, they reached Droitwich, from where after two days' rest they marched against Brereton. The latter hurriedly raised the sieges he had on hand, and called upon Yorkshire and the Scottish army there for aid. But only the old Lord Fairfax and the Yorkshiremen responded. Leven had just heard of new victories, won by Montrose. He could do no more than draw his army and his guns over the Pennine chain into Westmorland, in the hope of being in time to bar the King's march on Scotland via Carlisle.

Goring's return to the west had already been countermanded and he had been directed to march to Harborough, while the South Wales Royalists were also called in towards Leicester. Later orders on 26 May directed him to Newbury, whence he was to feel the strength of the enemy's positions around Oxford. It is hardly necessary to say that Goring found good military reasons for continuing his independent operations, and marched off towards Taunton regardless of the order. He redressed the balance there for the moment by overawing Massey's weak force, and his purse profited considerably by fresh opportunities for extortion, but he and his men were not at Naseby. Meanwhile the King, at the geographical centre of England, found an important and wealthy town at his mercy. Rupert, always for action, took the opportunity, and Leicester was stormed and thoroughly pillaged on the night of the 30 May–31 May.

Goring's return to the west had already been countermanded and he had been directed to march to Harborough, while the South Wales Royalists were also called in towards Leicester. Later orders on 26 May directed him to Newbury, whence he was to feel the strength of the enemy's positions around Oxford. It is hardly necessary to say that Goring found good military reasons for continuing his independent operations, and marched off towards Taunton regardless of the order. He redressed the balance there for the moment by overawing Massey's weak force, and his purse profited considerably by fresh opportunities for extortion, but he and his men were not at Naseby. Meanwhile the King, at the geographical centre of England, found an important and wealthy town at his mercy. Rupert, always for action, took the opportunity, and Leicester was stormed and thoroughly pillaged on the night of the 30 May–31 May.

There was the usual panic at Westminster, but, unfortunately for Charles, it resulted in Fairfax being directed to abandon the siege of Oxford and given carte blanche to bring the Royal army to battle wherever it was met. On his side the King had, after the capture of Leicester, accepted the advice of those who feared for the safety of Oxford. Rupert, though commander-in-chief, was unable to insist on the northern enterprise and had marched to Daventry, where he halted to throw supplies into Oxford.