Military history of Australia during World War I

Encyclopedia

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

, the outbreak of World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

was greeted with considerable enthusiasm. Even before Britain

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

declared war on Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

on 4 August 1914, the nation pledged its support for the Empire alongside other Commonwealth nations and almost immediately began preparations to send forces overseas to participate in the conflict. The first campaign that Australians were involved in was in German New Guinea

German New Guinea

German New Guinea was the first part of the German colonial empire. It was a protectorate from 1884 until 1914 when it fell to Australia following the outbreak of the First World War. It consisted of the northeastern part of New Guinea and several nearby island groups...

after a hastily raised force known as the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force

Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force

The Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force was a small volunteer force of approximately 2,000 men, raised in Australia shortly after the outbreak of the First World War to seize and destroy German wireless stations in German New Guinea in the south-west Pacific...

was dispatched from Australia to seize German possessions in the Pacific in September 1914. At the same time another expeditionary force, initially consisting of 20,000 men and known as the First Australian Imperial Force

First Australian Imperial Force

The First Australian Imperial Force was the main expeditionary force of the Australian Army during World War I. It was formed from 15 August 1914, following Britain's declaration of war on Germany. Generally known at the time as the AIF, it is today referred to as the 1st AIF to distinguish from...

(AIF), was raised for service overseas.

The AIF departed Australia in November 1914 and, after several delays due to the presence of German naval vessels in the Indian Ocean, arrived in Egypt, where they were initially used to defend the Suez Canal

Suez Canal

The Suez Canal , also known by the nickname "The Highway to India", is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea. Opened in November 1869 after 10 years of construction work, it allows water transportation between Europe and Asia without navigation...

. In early 1915, however, it was decided to carry out an amphibious landing on the Gallipoli peninsula with the goal of opening up a second front and securing the passage of the Dardanelles

Dardanelles

The Dardanelles , formerly known as the Hellespont, is a narrow strait in northwestern Turkey connecting the Aegean Sea to the Sea of Marmara. It is one of the Turkish Straits, along with its counterpart the Bosphorus. It is located at approximately...

. The Australians and New Zealanders, grouped together as the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps

Australian and New Zealand Army Corps

The Australian and New Zealand Army Corps was a First World War army corps of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force that was formed in Egypt in 1915 and operated during the Battle of Gallipoli. General William Birdwood commanded the corps, which comprised troops from the First Australian Imperial...

(ANZAC), went ashore on 25 April 1915 and for the next eight months the Anzacs, alongside their British, French and other allies, fought a costly and ultimately unsuccessful campaign against the Turks.

The force was evacuated from the peninsula in December 1915 and returned to Egypt, where the AIF was expanded. In early 1916 it was decided that the infantry divisions would be sent to France, where they took part in many of the major battles fought on the Western Front

Western Front (World War I)

Following the outbreak of World War I in 1914, the German Army opened the Western Front by first invading Luxembourg and Belgium, then gaining military control of important industrial regions in France. The tide of the advance was dramatically turned with the Battle of the Marne...

. Most of the light horse units remained in the Middle East until the end of the war, carrying out further operations against the Turks in Egypt and Palestine

Sinai and Palestine Campaign

The Sinai and Palestine Campaigns took place in the Middle Eastern Theatre of World War I. A series of battles were fought between British Empire, German Empire and Ottoman Empire forces from 26 January 1915 to 31 October 1918, when the Armistice of Mudros was signed between the Ottoman Empire and...

. Small numbers of Australians served in other theatres of war. While the main focus of the Australian military's effort was the ground war, air and naval forces were also committed. Squadrons of the Australian Flying Corps served in the Middle East and on the Western Front, while elements of the Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy

The Royal Australian Navy is the naval branch of the Australian Defence Force. Following the Federation of Australia in 1901, the ships and resources of the separate colonial navies were integrated into a national force: the Commonwealth Naval Forces...

carried out operations in the Atlantic, North Sea

North Sea

In the southwest, beyond the Straits of Dover, the North Sea becomes the English Channel connecting to the Atlantic Ocean. In the east, it connects to the Baltic Sea via the Skagerrak and Kattegat, narrow straits that separate Denmark from Norway and Sweden respectively...

, Adriatic and Black Sea

Black Sea

The Black Sea is bounded by Europe, Anatolia and the Caucasus and is ultimately connected to the Atlantic Ocean via the Mediterranean and the Aegean seas and various straits. The Bosphorus strait connects it to the Sea of Marmara, and the strait of the Dardanelles connects that sea to the Aegean...

, as well as the Pacific and Indian Ocean

Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third largest of the world's oceanic divisions, covering approximately 20% of the water on the Earth's surface. It is bounded on the north by the Indian Subcontinent and Arabian Peninsula ; on the west by eastern Africa; on the east by Indochina, the Sunda Islands, and...

s.

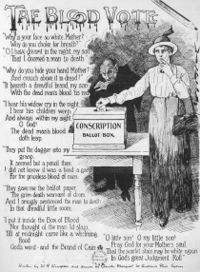

By the end of the war, Australians were far more circumspect. The nation's involvement cost over 60,000 Australians their lives and many more were left unable to work as a result of their injuries. The impact of the war was felt in many other areas also. Financially it was very costly, while the effect on the social and political landscape was considerable and threatened to cause serious divides in the nation's social fabric. Conscription

Conscription in Australia

Conscription in Australia, or mandatory military service also known as National Service, has a controversial history dating back to the first years of nationhood...

was possibly the most contentious issue and ultimately, despite having conscription for home service, Australia was one of only two combatants not to use conscripts in the fighting. Nevertheless, for many Australians the nation's involvement in World War I and the Gallipoli campaign was seen as a symbol of its emergence as an international actor, while many of the notions of the Australian character and nationhood that exist today have their origins in the war and Anzac Day

ANZAC Day

Anzac Day is a national day of remembrance in Australia and New Zealand, commemorated by both countries on 25 April every year to honour the members of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps who fought at Gallipoli in the Ottoman Empire during World War I. It now more broadly commemorates all...

is celebrated as a national holiday.

Outbreak of the war

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom. It originated with the overseas colonies and trading posts established by England in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. At its height, it was the...

became automatically involved, with Prime Minister

Prime Minister of Australia

The Prime Minister of the Commonwealth of Australia is the highest minister of the Crown, leader of the Cabinet and Head of Her Majesty's Australian Government, holding office on commission from the Governor-General of Australia. The office of Prime Minister is, in practice, the most powerful...

Joseph Cook

Joseph Cook

Sir Joseph Cook, GCMG was an Australian politician and the sixth Prime Minister of Australia. Born as Joseph Cooke and working in the coal mines of Silverdale, Staffordshire during his early life, he emigrated to Lithgow, New South Wales during the late 1880s, and became General-Secretary of the...

stating on 5 August 1914 that "...when the Empire is at war, so also is Australia." Given the predominantly British heritage of most Australians at the time, there was considerable support from all corners of the country and large numbers of young Australian men reported to recruiting centres around the country to enlist in the following months. When Prime Minister Andrew Fisher

Andrew Fisher

Andrew Fisher was an Australian politician who served as the fifth Prime Minister on three separate occasions. Fisher's 1910-13 Labor ministry completed a vast legislative programme which made him, along with Protectionist Alfred Deakin, the founder of the statutory structure of the new nation...

's Labor Party

Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party is an Australian political party. It has been the governing party of the Commonwealth of Australia since the 2007 federal election. Julia Gillard is the party's federal parliamentary leader and Prime Minister of Australia...

came to power in September 1914, he reiterated Cook's statement saying, "Should the worst happen ...", Australia would "...rally to the Mother Country ... to help and defend her to our last man and our last shilling."

Within days, plans for an Australian expeditionary force were completed by Brigadier General

Brigadier General

Brigadier general is a senior rank in the armed forces. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries, usually sitting between the ranks of colonel and major general. When appointed to a field command, a brigadier general is typically in command of a brigade consisting of around 4,000...

William Throsby Bridges

William Throsby Bridges

Major General Sir William Throsby Bridges KCB, CMG served with Australian forces during World War I, and was the first Australian to reach general officer rank...

and his staff officer, Major Cyril Brudenell Bingham White

Brudenell White

General Sir Cyril Brudenell Bingham White KCB, KCMG, KCVO, DSO was a senior officer in the Australian Army, who served as Chief of the General Staff from 1920 to 1923 and again from March to August 1940, when he was killed in the Canberra air disaster.-Early Life and career:White was born in St...

. White proposed a force of 18,000 men (12,000 Australians and 6,000 New Zealand

New Zealand

New Zealand is an island country in the south-western Pacific Ocean comprising two main landmasses and numerous smaller islands. The country is situated some east of Australia across the Tasman Sea, and roughly south of the Pacific island nations of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Tonga...

ers). This proposal was approved by Prime Minister Cook but he increased the offer to the British to 20,000 men to serve in any destination desired by the Home Government. On 6 August 1914, London cabled its acceptance of the force and asked that it be sent as soon as possible. Recruiting offices opened on 10 August 1914 and by the end of 1914, 52,561 volunteers had been accepted, although strict physical fitness guidelines were put in place.

German New Guinea

In 1884, Germany had colonised the north eastern part of New Guinea

New Guinea

New Guinea is the world's second largest island, after Greenland, covering a land area of 786,000 km2. Located in the southwest Pacific Ocean, it lies geographically to the east of the Malay Archipelago, with which it is sometimes included as part of a greater Indo-Australian Archipelago...

and several nearby island groups. By the outbreak of the war, the Germans had been using the colony as a wireless radio base, and supporting the German East Asia Squadron

German East Asia Squadron

The German East Asia Squadron was a German Navy cruiser squadron which operated mainly in the Pacific Ocean between the 1870s and 1914...

which threatened merchant shipping in the region. As a consequence, Britain required the wireless installations to be destroyed. Shortly after the outbreak of war—following a request by the British government on 6 August 1914—the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force (AN&MEF) began forming. The objectives of the force were the German stations at Yap

Yap

Yap, also known as Wa'ab by locals, is an island in the Caroline Islands of the western Pacific Ocean. It is a state of the Federated States of Micronesia. Yap's indigenous cultures and traditions are still strong compared to other neighboring islands. The island of Yap actually consists of four...

in the Caroline Islands

Caroline Islands

The Caroline Islands are a widely scattered archipelago of tiny islands in the western Pacific Ocean, to the north of New Guinea. Politically they are divided between the Federated States of Micronesia in the eastern part of the group, and Palau at the extreme western end...

, Nauru

Nauru

Nauru , officially the Republic of Nauru and formerly known as Pleasant Island, is an island country in Micronesia in the South Pacific. Its nearest neighbour is Banaba Island in Kiribati, to the east. Nauru is the world's smallest republic, covering just...

and at Rabaul

Rabaul

Rabaul is a township in East New Britain province, Papua New Guinea. The town was the provincial capital and most important settlement in the province until it was destroyed in 1994 by falling ash of a volcanic eruption. During the eruption, ash was sent thousands of metres into the air and the...

, New Britain

New Britain

New Britain, or Niu Briten, is the largest island in the Bismarck Archipelago of Papua New Guinea. It is separated from the island of New Guinea by the Dampier and Vitiaz Straits and from New Ireland by St. George's Channel...

. The AN&MEF comprised one battalion of infantry (1,023 men) enlisted in Sydney, 500 naval reservists and ex-sailors organised into six companies who would serve as infantry and a further 500 men from the Kennedy Regiment, a Queensland militia battalion that had volunteered for overseas service and had been sent to garrison Thursday Island. Together, these forces were placed under the command of Colonel William Holmes, an officer in the militia who was at the time commander of the 6th Brigade

6th Brigade (Australia)

The 6th Brigade is an Australian Army brigade. First formed during the First World War as an infantry unit of the Australian Imperial Force, the brigade served at Gallipoli and in France and Belgium on the Western Front...

and secretary of the Sydney Water and Sewerage Board

Sydney Water

Sydney Water is a New South Wales government owned corporation that provides drinking water, wastewater and some stormwater services to Sydney, Illawarra and the Blue Mountains, in Australia...

.

The task force sailed from Sydney on 19 August 1914, and hove to off Port Moresby where they waited for their escorts to arrive. While they were at Port Moresby, Holmes decided to disembark the Queensland militia soldiers due to concerns about their preparedness for action. Escorted by the cruisers Sydney and Australia, the task force reached Rabaul

Rabaul

Rabaul is a township in East New Britain province, Papua New Guinea. The town was the provincial capital and most important settlement in the province until it was destroyed in 1994 by falling ash of a volcanic eruption. During the eruption, ash was sent thousands of metres into the air and the...

on 11 September 1914 and found that the port was free of German forces. Sydney and the destroyer landed small parties of naval reservists at the settlements of Kabakaul and the German gubernatorial capital Herbertshöhe on Neu-Pommern, south-east of Rabaul. These parties were reinforced first by sailors from and and later by infantry from the transport .

Battle of Bita Paka

The Battle of Bita Paka was fought south of Kabakaul, on the island of New Britain, and was a part of the invasion and subsequent occupation of German New Guinea by the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force shortly after the outbreak of the First World War...

six Australians were killed and five wounded, while the defenders lost one German non-commissioned officer

Non-commissioned officer

A non-commissioned officer , called a sub-officer in some countries, is a military officer who has not been given a commission...

(NCO) and about 30 Melanesians killed, and one German and ten Melanesians wounded. Later it was alleged that the heavy losses among the Melanesian troops was the result of the Australians bayoneting all those they had captured during the fighting. As a result of this engagement, Able Seaman

Able Seaman (rank)

In the British Royal Navy in the middle of the 18th century, the term able seaman referred to a seaman with at least two years' experience at sea...

W.G.V. Williams became the first Australian fatality of the war. The first Army fatality was a medical officer, Captain B. C. A. Pockley, who died the same day.

At nightfall on 12 September, the Berrima landed the AN&MEF infantry battalion at Rabaul. The following afternoon, although the governor had not yet surrendered the territory, a ceremony was carried out to signal the British occupation of New Britain. The German administration had withdrawn inland to Toma and at dawn on 14 September, and subsequently bombarded a ridge near the town, while half a battalion advanced towards the town supported by a field gun

Field gun

A field gun is an artillery piece. Originally the term referred to smaller guns that could accompany a field army on the march and when in combat could be moved about the battlefield in response to changing circumstances, as to opposed guns installed in a fort, or to siege cannon or mortars which...

. The show of fire power was sufficient to start negotiations, ending the Siege of Toma

Siege of Toma

The Siege of Toma was a bloodless action during the First World War on the island of New Britain between 14–17 September 1914 as part of the occupation of German New Guinea by the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force...

following the surrender of the remaining garrison of 40 Germans and 110 native police. The German territory surrendered on 17 September 1914.

Although successful the operation was arguably not well managed, and the Australians had been effectively delayed by a half-trained native force. Regardless the Australians had prevailed not least of all because of their unexpected ability to fight in close terrain, while the outflanking of the German positions had unnerved their opponents. The losses of the AN&MEF were light in the context of later operations but were sufficiently heavy given the relatively modest gain. These losses were further compounded by the unexplained disappearance of the Australian submarine during a patrol off Rabaul on 14 September, with 35 men aboard.

Following the capture of German possessions in the region, the AN&MEF provided occupation forces for the duration of the war. On 9 January 1915, Holmes handed over command of the AN&MEF to Brigadier General Sir Samuel Pethebridge, the former Secretary of the Department of Defence

Department of Defence (Australia)

The Australian Department of Defence is a Federal Government Department. It forms part of the Australian Defence Organisation along with the Australian Defence Force . The Defence mission is to defend Australia and its national interests...

. Holmes returned to Australia and re-enlisted in the AIF, as did most of his men. They were replaced by the 3rd Battalion, known as the "Tropical Force" because it had been specially enlisted for service in the tropics. Pethebridge established the administrative structures that remain through the period of military occupation. Although required by International law

International law

Public international law concerns the structure and conduct of sovereign states; analogous entities, such as the Holy See; and intergovernmental organizations. To a lesser degree, international law also may affect multinational corporations and individuals, an impact increasingly evolving beyond...

to follow the German forms of government, the territory gradually acquired the appearance of a British colony.

First Australian Imperial Force

At the start of the war, Australia's military forces were focused upon the militia and what Regular forces existed were mostly serving in the artillery or engineers and were assigned in most part to the task of coastal defence. Due to the provisions of the Defence Act 1903, which precluded sending conscripts overseas, upon the outbreak of war it was realised that a totally separate, all volunteer force would need to be raised. This force was known as the Australian Imperial Force (AIF).The AIF raised for World War I service has subsequently been called the First AIF in order to distinguish it from the Second AIF which was raised during World War II.

The AIF began forming shortly after the outbreak of war and was the brain child of William Throsby Bridges

William Throsby Bridges

Major General Sir William Throsby Bridges KCB, CMG served with Australian forces during World War I, and was the first Australian to reach general officer rank...

and Cyril Brudenell Bingham White

Brudenell White

General Sir Cyril Brudenell Bingham White KCB, KCMG, KCVO, DSO was a senior officer in the Australian Army, who served as Chief of the General Staff from 1920 to 1923 and again from March to August 1940, when he was killed in the Canberra air disaster.-Early Life and career:White was born in St...

. Upon formation, the AIF consisted of only one infantry division, the 1st Australian Division, and the 1st Light Horse Brigade

1st Light Horse Brigade

The 1st Light Horse Brigade was a mounted infantry brigade of the First Australian Imperial Force which served in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I. The brigade first saw action during the Dardanelles Campaign in the Battle of Gallipoli. After being withdrawn to Egypt in February 1916 they...

. The 1st Division was made up of the 1st Infantry Brigade

Australian 1st Brigade

1st Brigade is a formation of the Australian Army intended as its primary mechanised formation. Raised for service initially in 1914 for service during World War I, the brigade fought at Gallipoli and on the Western Front before being disbanded in mid-1919. In 1921, the 1st Brigade was re-raised as...

under Colonel Henry MacLaurin; the 2nd

2nd Brigade (Australia)

The 2nd Brigade was a brigade-sized infantry unit of the Australian Army.Formed in 1903 as militia formation based in Victoria, the brigade later served during the First World War as part of the Australian Imperial Force, allocated to the 1st Division...

, under Colonel James Whiteside McCay

James Whiteside McCay

Lieutenant General Sir James Whiteside McCay KCMG, KBE, CB, VD was an Australian general and politician. A graduate of the University of Melbourne, where he earned Master of Arts and Master of Laws degrees, he established a successful legal practice, McCay & Thwaites...

, an Australian politician and former Minister for Defence

Minister for Defence (Australia)

The Minister for Defence of Australia administers his portfolio through the Australian Defence Organisation, which comprises the Department of Defence and the Australian Defence Force. Stephen Smith is the current Minister.-Ministers for Defence:...

; and the 3rd

Australian 3rd Brigade

The 3rd Brigade is a combined arms brigade of the Australian Army, based around the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the Royal Australian Regiment . It was originally formed in 1914 for service during World War I, taking part in the fighting at Gallipoli and on the Western Front in Europe...

, under Colonel Ewen Sinclair MacLagan, a British regular officer seconded to the Australian Army before the war. The 1st Light Horse Brigade was commanded by Colonel Henry George Chauvel

Henry George Chauvel

General Sir Harry Chauvel GCMG, KCB was a senior officer of the Australian Imperial Force who fought at Gallipoli and in the Middle Eastern theatre during the First World War. He was the first Australian to attain the rank of lieutenant general and later general, and the first to lead a corps...

, an Australian regular, while the divisional artillery was commanded by Colonel Talbot Hobbs

Talbot Hobbs

Lieutenant General Sir Joseph John Talbot Hobbs KCB, KCMG, VD was an Australian architect and First World War general.-Early life:...

.

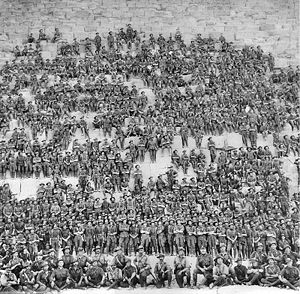

In the early stages of mobilisation the men of the AIF were selected under some of the toughest criterion of any army in World War I and it is believed that roughly 30% of men that applied were rejected on medical grounds. In order to enlist, men had to be aged between 18 and 35 years of age (although it is believed that men as old as 70 and as young as 14 managed to enlist), and they had to be at least five foot six inches tall (168 centimetres), with a chest measurement of at least 34 inches (86 centimetres). Many of these strict requirements were lifted later in the war, however, as the need for replacements grew. Indeed, casualties among the initial volunteers were so high, that of the 32,000 original soldiers of the AIF only 7,000 would survive to the end of the war.

The initial response was so good that in September 1914 the decision was made to raise the 4th Infantry Brigade and 2nd and 3rd Light Horse Brigades. The 4th Infantry Brigade was commanded by Colonel John Monash

John Monash

General Sir John Monash GCMG, KCB, VD was a civil engineer who became the Australian military commander in the First World War. He commanded the 13th Infantry Brigade before the War and then became commander of the 4th Brigade in Egypt shortly after the outbreak of the War with whom he took part...

, a prominent Melbourne

Melbourne

Melbourne is the capital and most populous city in the state of Victoria, and the second most populous city in Australia. The Melbourne City Centre is the hub of the greater metropolitan area and the Census statistical division—of which "Melbourne" is the common name. As of June 2009, the greater...

civil engineer

Civil engineer

A civil engineer is a person who practices civil engineering; the application of planning, designing, constructing, maintaining, and operating infrastructures while protecting the public and environmental health, as well as improving existing infrastructures that have been neglected.Originally, a...

and businessman. The AIF continued to grow through the war, eventually numbering five infantry division

Division (military)

A division is a large military unit or formation usually consisting of between 10,000 and 20,000 soldiers. In most armies, a division is composed of several regiments or brigades, and in turn several divisions typically make up a corps...

s, two mounted divisions and a mixture of other units. A sixth infantry division, the Australian 6th Division, was partially formed in the United Kingdom February 1917. Casualties from the First Battle of Bullecourt and the Battle of Messines

Battle of Messines

The Battle of Messines was a battle of the Western front of the First World War. It began on 7 June 1917 when the British Second Army under the command of General Herbert Plumer launched an offensive near the village of Mesen in West Flanders, Belgium...

caused the disbandment of the partially formed unit to allow the other five divisions to be brought back up to strength.

Background

Albany, Western Australia

Albany is a port city in the Great Southern region of Western Australia, some 418 km SE of Perth, the state capital. As of 2009, Albany's population was estimated at 33,600, making it the 6th-largest city in the state....

on 1 November 1914 in convoy of 10 transports escorted by several British, Australian and Japanese warships. Initially bound for British-controlled Egypt

Egypt

Egypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

, with a stopover in Ceylon, the convoy had been delayed several times due to fears of interception by German warships in the area. These fears later proved valid when the German cruiser Emden

Emden

Emden is a city and seaport in the northwest of Germany, on the river Ems. It is the main city of the region of East Frisia; in 2006, the city had a total population of 51,692.-History:...

was sighted off Cocos Island

Cocos Island

Cocos Island is an uninhabited island located off the shore of Costa Rica . It constitutes the 11th district of Puntarenas Canton of the province of Puntarenas. It is one of the National Parks of Costa Rica...

. As the convoy steered to avoid the threat, the Australian cruiser, HMAS Sydney

HMAS Sydney (1912)

HMAS Sydney was a Chatham class light cruiser of the Royal Australian Navy . Laid down in 1911 and launched in 1912, the cruiser was commissioned into the RAN in 1913....

, engaged the Emden with her heavier guns and after an engagement that lasted only twenty-five minutes, the Sydney emerged victorious.

The threat of the German Squadron neutralised, the convoy was able to continue its voyage unmolested. Upon their arrival in Egypt in November, the 1st Division moved to Camp Mena, near Cairo

Cairo

Cairo , is the capital of Egypt and the largest city in the Arab world and Africa, and the 16th largest metropolitan area in the world. Nicknamed "The City of a Thousand Minarets" for its preponderance of Islamic architecture, Cairo has long been a centre of the region's political and cultural life...

, where they were used to defend the Suez Canal

Suez Canal

The Suez Canal , also known by the nickname "The Highway to India", is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea. Opened in November 1869 after 10 years of construction work, it allows water transportation between Europe and Asia without navigation...

against Turkey who had declared war on 29 October. During this time, the Australians commenced a period of training to prepare them for combat on the Western Front

Western Front (World War I)

Following the outbreak of World War I in 1914, the German Army opened the Western Front by first invading Luxembourg and Belgium, then gaining military control of important industrial regions in France. The tide of the advance was dramatically turned with the Battle of the Marne...

as it was still expected that they would be sent to England for deployment in the European theatre. As they waited, however, the Australian and New Zealand forces in Egypt at the time were formed into the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps

Australian and New Zealand Army Corps

The Australian and New Zealand Army Corps was a First World War army corps of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force that was formed in Egypt in 1915 and operated during the Battle of Gallipoli. General William Birdwood commanded the corps, which comprised troops from the First Australian Imperial...

(ANZAC) under the command of Lieutenant General William Birdwood, and consisting of the Australian 1st Division and the composite New Zealand and Australian Division

New Zealand and Australian Division

The New Zealand and Australian Division was formed at the start of the Battle of Gallipoli as a composite division under the command of New Zealand general Alexander Godley. At the start of World War I New Zealand had mustered insufficient infantry battalions to form their own division while...

(NZ&A).

Overcrowding and shortages of equipment in England meant that it was decided to keep the Anzacs in Egypt during the European winter, during which time they would undertake further training in order to prepare them for their eventual use in the trenches in France. Despite this, however, the training that the Australians and New Zealanders received in this time could only be considered very rudimentary in nature, and despite popular opinion at the time, it did little to prepare them for what was to come.

In the background, though, moves were being made to commit the Australians and New Zealanders elsewhere. Later in November, Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

, in his capacity as First Lord of the Admiralty, put forward his first plans for a naval attack on the Dardanelles

Dardanelles

The Dardanelles , formerly known as the Hellespont, is a narrow strait in northwestern Turkey connecting the Aegean Sea to the Sea of Marmara. It is one of the Turkish Straits, along with its counterpart the Bosphorus. It is located at approximately...

. A plan for an attack and invasion of the Gallipoli

Gallipoli

The Gallipoli peninsula is located in Turkish Thrace , the European part of Turkey, with the Aegean Sea to the west and the Dardanelles straits to the east. Gallipoli derives its name from the Greek "Καλλίπολις" , meaning "Beautiful City"...

peninsula was eventually approved by the British cabinet in January 1915. It was decided that the Australian and New Zealand troops would take part in the operation, although they were outnumbered by the British, Indian and French contingents, a fact which is often overlooked today by many Australians and New Zealanders. The objective of the invasion was to open up another front against the Central Powers

Central Powers

The Central Powers were one of the two warring factions in World War I , composed of the German Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulgaria...

and to open the Black Sea

Black Sea

The Black Sea is bounded by Europe, Anatolia and the Caucasus and is ultimately connected to the Atlantic Ocean via the Mediterranean and the Aegean seas and various straits. The Bosphorus strait connects it to the Sea of Marmara, and the strait of the Dardanelles connects that sea to the Aegean...

's only entrance to the Mediterranean, via the Dardanelles

Dardanelles

The Dardanelles , formerly known as the Hellespont, is a narrow strait in northwestern Turkey connecting the Aegean Sea to the Sea of Marmara. It is one of the Turkish Straits, along with its counterpart the Bosphorus. It is located at approximately...

and Bosphorus, to allow shipping to Russia all year round.

After the failure of naval attacks, it was decided that ground forces were necessary to eliminate the Turkish mobile artillery and allow minesweepers to clear the waters for larger vessels. The British Secretary of State for War

Secretary of State for War

The position of Secretary of State for War, commonly called War Secretary, was a British cabinet-level position, first held by Henry Dundas . In 1801 the post became that of Secretary of State for War and the Colonies. The position was re-instated in 1854...

, Field Marshal Lord Kitchener, appointed General

General (United Kingdom)

General is currently the highest peace-time rank in the British Army and Royal Marines. It is subordinate to the Army rank of Field Marshal, has a NATO-code of OF-9, and is a four-star rank....

Sir Ian Hamilton to command the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force

Mediterranean Expeditionary Force

The Mediterranean Expeditionary Force was part of the British Army during World War I, that commanded all Allied forces at Gallipoli and Salonika. This included the initial naval operation to force the straits of the Dardanelles. Its headquarters was formed in March 1915...

(MEF) that was to carry out the mission. The MEF consisted of Birdwood's ANZAC, British 29th Division

British 29th Division

The British 29th Division, known as the Incomparable Division, was a First World War regular army infantry division formed in early 1915 by combining various units that had been acting as garrisons about the British Empire. Under the command of Major General Aylmer Hunter-Weston, the division...

, British Royal Naval Division and the French Corps expéditionnaire d'Orient. Some 40,000 Russian troops would participate in the capture or occupation of Constantinople

Istanbul

Istanbul , historically known as Byzantium and Constantinople , is the largest city of Turkey. Istanbul metropolitan province had 13.26 million people living in it as of December, 2010, which is 18% of Turkey's population and the 3rd largest metropolitan area in Europe after London and...

.

Landing at Anzac Cove

The invasion plan was for the 29th DivisionBritish 29th Division

The British 29th Division, known as the Incomparable Division, was a First World War regular army infantry division formed in early 1915 by combining various units that had been acting as garrisons about the British Empire. Under the command of Major General Aylmer Hunter-Weston, the division...

to land at Cape Helles

Cape Helles

Cape Helles is the rocky headland at the south-westernmost tip of the Gallipoli peninsula, Turkey. It was the scene of heavy fighting between Turkish and British troops during the landing at Cape Helles at the beginning of the Gallipoli Campaign in 1915....

on the tip of the peninsula and then advance upon the forts at Kilitbahir. The Anzacs were to land north of Gaba Tepe on the Aegean coast from where they could advance across the peninsula and prevent retreat from or reinforcement of Kilitbahir.

The Anzac assault force, the 3rd Brigade

Australian 3rd Brigade

The 3rd Brigade is a combined arms brigade of the Australian Army, based around the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the Royal Australian Regiment . It was originally formed in 1914 for service during World War I, taking part in the fighting at Gallipoli and on the Western Front in Europe...

of the Australian 1st Division, began to go ashore shortly before dawn at 4:30 am on 25 April 1915. The intended landing zone was a broad front centred about a mile north of Gaba Tepe, however, possibly due to navigational error or an unexpected current, the landing went awry and the boats concentrated about a mile and a half further north than intended in a shallow, nameless cove between Ari Burnu to the north and Hell Spit to the south. Since 1985, the cove has been officially known as Anzac Koyu (Anzac Cove)

Anzac Cove

Anzac Cove is a small cove on the Gallipoli peninsula in Turkey. It became famous as the site of World War I landing of the ANZAC on April 25, 1915. The cove is a mere long, bounded by the headlands of Ari Burnu to the north and Little Ari Burnu, known as Hell Spit, to the south...

.

The Anzacs were confronted by a treacherous, confusing tangle of ravines and spurs that descended from the heights of the Sarı Baır range to the sea. The landing was only lightly opposed by scattered Turkish units until Mustafa Kemal

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk was an Ottoman and Turkish army officer, revolutionary statesman, writer, and the first President of Turkey. He is credited with being the founder of the Republic of Turkey....

, commanding the 19th Division and perceiving the threat posed by the landings, rushed reinforcements to the area in what became a race for the high ground. The contest for the heights was decided on the second ridge line where the Anzacs and Turks

Turkey

Turkey , known officially as the Republic of Turkey , is a Eurasian country located in Western Asia and in East Thrace in Southeastern Europe...

fought over a knoll called Baby 700. The position changed hands a number of times on the first day before the Turks, having the advantage of the higher ground on Battleship Hill, took final possession of it. Once the Anzac advance was checked, the Turks counter-attacked, trying to force the invaders back to the shore, but failed to dislodge them from the foothold they had gained. A trench perimeter quickly developed and a bloody stalemate ensued until August.

Krithia

In May 1915, Hamilton decided to concentrate his resources in the Helles sector. Birdwood withdrew Colonel McCay's 2nd Infantry Brigade and the New Zealand Infantry Brigade and they moved by sea to Cape Helles on 6 May. During the subsequent Second Battle of Krithia the two brigades suffered 1,827 casualties, including McCay, in an ill-advised daylight advance over open ground that could have been occupied after dark without loss.During May Turkish snipers were particularly active in Monash Valley. On 15 May, one shot and fatally wounded Major General Bridges. His body was returned to Australia and buried on the hill overlooking Royal Military College, Duntroon

Royal Military College, Duntroon

The Royal Military College, Duntroon is the Australian Army's officer training establishment. It was founded at Duntroon, in the Australian Capital Territory, in 1911 and is situated on picturesque grounds at the foot of Mount Pleasant near Lake Burley Griffin, close to the Department of Defence...

in Canberra

Canberra

Canberra is the capital city of Australia. With a population of over 345,000, it is Australia's largest inland city and the eighth-largest city overall. The city is located at the northern end of the Australian Capital Territory , south-west of Sydney, and north-east of Melbourne...

. The Australian government sent Major General James Gordon Legge

James Gordon Legge

Lieutenant General James Gordon Legge CB, CMG was an Australian Army Lieutenant General who served in World War I. His son Stanley Ferguson Legge reached the rank of Major General.-Early life and career:...

from Australia to replace him.

Turkish counter-attack

On 19 May 1915, the Turkish launched an assault against the Anzac perimeter. Forewarned by naval reconnaissance aircraft, the troops were on alert and the position was reinforced by the return of the 2nd and New Zealand Infantry Brigades from Cape Helles and the arrival of the 1st Light Horse Brigade and New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade from Egypt. Along most of the line, the attack met with immediate disaster, with the Turkish attackers swept away by the rifle and machine gun fire of the Anzac defenders. At Courtney's Post, one of the most exposed parts of the perimeter, the Turks managed to enter the trenches but there they encountered Lance Corporal Albert JackaAlbert Jacka

Albert Jacka VC, MC & Bar was an Australian recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest decoration for gallantry "in the face of the enemy" that can be awarded to members of the British and Commonwealth armed forces...

and others, who drove them out again. For his action, Jacka became the first Australian to win the Victoria Cross

Victoria Cross

The Victoria Cross is the highest military decoration awarded for valour "in the face of the enemy" to members of the armed forces of various Commonwealth countries, and previous British Empire territories....

in the war.

August offensive

Suvla

Suvla is a bay on the Aegean coast of the Gallipoli peninsula in European Turkey, south of the Gulf of Saros.On 6 August 1915 it was the site for the Landing at Suvla Bay by the British IX Corps as part of the August Offensive during the Battle of Gallipoli...

, 5 miles (8 km) north of Anzac. Meanwhile at Anzac a strong assault would be made on the Sari Bair range by breaking out through thinly defended sector at the north of the Anzac perimeter. The offensive was preceded on the evening of 6 August by diversionary assaults at Helles and Anzac. At Helles, the diversion at Krithia Vineyard

Battle of Krithia Vineyard

The Battle of Krithia Vineyard was intended as a minor British action at Helles on the Gallipoli peninsula to divert attention from the imminent launch of the August Offensive. Instead, the British commander, Brigadier General H.E...

became another futile battle with no gains and heavy casualties for both sides. At Anzac, an attack on the Turkish trenches at Lone Pine by the infantry brigades of the Australian 1st Division was a rare victory for the ANZACs. At a cost of over 2,000 men, the Australians inflicted 7,000 casualties on the Turks. Because it was an effective attack on a vital position, it was the most effective diversionary attack carried out by the Australians of the war, drawing in the Turkish reserves.

However, the main assault aimed at the peaks of Chunuk Bair and Hill 971 was less successful. The force striking for the nearer peak of Chunuk Bair comprised the New Zealand Infantry Brigade. It came within 500 metres (1,640.4 ft) of the peak by dawn on 7 August but was not able to seize the summit until the following morning. This delay had fatal consequences for another supporting attack on the morning of 7 August, that of the Australian 3rd Light Horse Brigade at the Nek

Battle of the Nek

The Battle of the Nek was a small World War I battle fought as part of the Gallipoli campaign. "The Nek" was a narrow stretch of ridge in the Anzac battlefield on the Gallipoli peninsula. The name derives from the Afrikaans word for a "mountain pass" but the terrain itself was a perfect bottleneck...

which was to coincide with the New Zealanders attacking back down from Chunuk Bair against the rear of the Turkish defences. The New Zealanders held out on Chunuk Bair for two days before relief was provided by two New Army

Kitchener's Army

The New Army, often referred to as Kitchener's Army or, disparagingly, Kitchener's Mob, was an all-volunteer army formed in the United Kingdom following the outbreak of hostilities in the First World War...

battalions from the Wiltshire

Wiltshire Regiment

The Wiltshire Regiment was an infantry regiment of the line in the British Army, formed in 1881 by the amalgamation of the 62nd Regiment of Foot and the 99th Duke of Edinburgh's Regiment of Foot....

and Loyal North Lancashire

Loyal Regiment (North Lancashire)

The Loyal Regiment was an infantry regiment of the line in the British Army from 1881 to 1970...

Regiments. A massive Turkish counter-attack

Counter-Attack

Counter-Attack is a 1945 war film starring Paul Muni and Marguerite Chapman as two Russians trapped in a collapsed building with seven enemy German soldiers during World War II...

, led in person by Mustafa Kemal, swept these two battalions from the heights. Meanwhile, the landing at Suvla Bay

Landing at Suvla Bay

The landing at Suvla Bay was an amphibious landing made at Suvla on the Aegean coast of Gallipoli peninsula in the Ottoman Empire as part of the August Offensive, the final British attempt to break the deadlock of the Battle of Gallipoli...

was only lightly opposed but the British commander, Lieutenant-General Sir Frederick Stopford

Frederick Stopford

Lieutenant General Sir Frederick William Stopford, KCB, KCMG, KCVO was a British Army officer.-Military career:...

, had so diluted his early objectives that little more than the beach was seized. Again the Turks were able to win the race for the high ground of the Anafarta Hills thereby rendering the Suvla front another case of static trench warfare

Trench warfare

Trench warfare is a form of occupied fighting lines, consisting largely of trenches, in which troops are largely immune to the enemy's small arms fire and are substantially sheltered from artillery...

.

The Suvla landing was reinforced by the arrival of the British 53rd and 54th Divisions along with the British 10th Division

British 10th (Irish) Division

The 10th Division, was one of the first of Kitchener's New Army K1 Army Group divisions , authorized on 21 August 1914, after the outbreak of the Great War. It included battalions from the various provinces of Ireland...

from Kitchener's New Army

Kitchener's Army

The New Army, often referred to as Kitchener's Army or, disparagingly, Kitchener's Mob, was an all-volunteer army formed in the United Kingdom following the outbreak of hostilities in the First World War...

Divisions plus the dismounted yeomanry

Yeomanry

Yeomanry is a designation used by a number of units or sub-units of the British Territorial Army, descended from volunteer cavalry regiments. Today, Yeomanry units may serve in a variety of different military roles.-History:...

of the 2nd Mounted Division

British 2nd Mounted Division

The 2nd Mounted Division, was a yeomanry division that served in the First World War. At the outbreak of war it was assigned to defence of the Norfolk coast. In March 1915 it formed a second-line duplicate of itself, the 2/2nd Mounted Division...

. The unfortunate 29th Division was also shifted from Helles to Suvla for one more push. The final British attempt to resuscitate the offensive came on 21 August with attacks at Scimitar Hill and Hill 60

Battle of Hill 60 (Gallipoli)

The Battle of Hill 60 was the last major assault of the Battle of Gallipoli. It was launched on 21 August 1915 to coincide with the attack on Scimitar Hill made from the Suvla front by General Stopford's British IX Corps. Hill 60 was a low knoll at the northern end of the Sari Bair range which...

. Control of these hills would have united the Anzac and Suvla fronts but neither battle achieved success. When fighting at Hill 60 ceased on 29 August, the battle for the Sari Bair heights, and indeed the battle for the peninsula, was effectively over.

Evacuation

Gallipoli

The Gallipoli peninsula is located in Turkish Thrace , the European part of Turkey, with the Aegean Sea to the west and the Dardanelles straits to the east. Gallipoli derives its name from the Greek "Καλλίπολις" , meaning "Beautiful City"...

peninsula. Troop numbers were progressively reduced from 7 December and cunning ruses were performed to fool the Turks and to prevent them from discovering the Allies that were departing. At Anzac, the troops would maintain utter silence for an hour or more until the curious Turks would venture out to inspect the trenches, whereupon the Anzacs would open fire. As the numbers in the trenches were thinned, rifles were rigged to fire by water dripped into a pan attached to the trigger. In what was ironically the best planned operation of the campaign, the evacuation was completed by dawn on 20 December 1915, without a single casualty.

Ultimately the Gallipoli campaign was a disastrous failure. It did not achieve any of the objectives that had been given as a justification for it, and due to the inexperience of high commanders and mismanagement there were an unacceptably high number of casualties amongst the participating troops, not only from as a result of combat, but also due to widespread disease that resulted from poor sanitation and hygiene in the front lines and a breakdown in the casualty clearance and resupply and logistics systems. It has been estimated that over the course of the campaign there were 26,111 Australian casualties with 8,141 killed. Other Allied casualties—killed and wounded—included: 7,571 New Zealanders, 120,000 British and 27,000 French.

After the war, the bad conditions and high casualties amongst the Anzac troops resulted in a reasonably prevalent view in Australia that these had been due to the incompetence of British officers commanding the Australian troops and their disregard for the casualties that resulted from poorly planned or ill-conceived attacks. Whether these claims are valid or not, there can be little doubt that the entire campaign was poorly conducted, and as a result there were many military lessons learnt that were to be applied in later campaigns. Despite this, for Australians and New Zealanders the Gallipoli campaign has come to symbolise an important milestone in the emergence of both nations as independent actors on the world stage and the development of a sense of national identity. Today, the date of the initial landings, 25 April, is a public holiday known as Anzac Day

ANZAC Day

Anzac Day is a national day of remembrance in Australia and New Zealand, commemorated by both countries on 25 April every year to honour the members of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps who fought at Gallipoli in the Ottoman Empire during World War I. It now more broadly commemorates all...

in Australia and New Zealand and every year thousands of people gather at memorials in both nations, and indeed in Turkey, to honour the bravery and sacrifice of the original Anzacs, and of all those who have subsequently lost their lives in war.

Egypt and Palestine

After the Gallipoli Campaign, Australian troops returned to Egypt

Egypt

Egypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

and the AIF underwent a major expansion, which involved the raising of another three infantry divisions—the 3rd, 4th and 5th—and the establishment of the Anzac Mounted Division. In March 1916 the infantry began to move to France while the cavalry units stayed in the area and fought Turkish troops and the Senussi Arab tribes that were threatening British control of Egypt. Mounted troops were particularly important in the defence of Egypt and Australian troops of the Anzac Mounted Division

Anzac Mounted Division

The ANZAC Mounted Division was a mounted infantry and mounted rifles division formed in March 1916 in Egypt during World War I following the Battle of Gallipoli when the Australian and New Zealand regiments returned from fighting dismounted as infantry...

saw action in all the major battles of the campaign, first seeing combat in the Battle of Romani

Battle of Romani

The Battle of Romani was fought east of the Suez Canal, near the Egyptian town of Romani and the site of ancient Pelusium on the Sinai Peninsula during the First World War...

. Apart from the horsemen, the mounted troops included the 1st Imperial Camel Corps

Imperial Camel Corps

The Imperial Camel Corps was a brigade-sized military formation which fought for the Allies in the Sinai and Palestine Campaign in World War I. Its personnel were infantry mounted on camels for movement across desert....

Brigade. This was organised as a mounted infantry brigade. Of its four battalions, the 1st and 3rd were composed of Australians, the 2nd was British, and the 4th was half Australian and half New Zealand. The cameliers participated in most of the fighting in Egypt and Palestine until the brigade was disbanded in July 1918. The Australian and New Zealand components then traded their camels for horses and became the 5th Light Horse Brigade.

Fighting the Senussi Arabs

In response to the growing threat from a pro-Turkish Islamic Arab sect known as the SenussiSenussi

The Senussi or Sanussi refers to a Muslim political-religious order in Libya and the Sudan region founded in Mecca in 1837 by the Grand Senussi, Sayyid Muhammad ibn Ali as-Senussi. Senussi was concerned with both the decline of Islamic thought and spirituality and the weakening of Muslim political...

, a composite British force—the "Western Frontier Force"—under the command of the British Indian Army

British Indian Army

The British Indian Army, officially simply the Indian Army, was the principal army of the British Raj in India before the partition of India in 1947...

officer Major General Alexander Wallace, was sent into the Libyan Desert

Libyan Desert

The Libyan Desert covers an area of approximately 1,100,000 km2, it extends approximately 1100 km from east to west, and 1,000 km from north to south, in about the shape of a rectangle...

to Mersa Matruh in late-November 1915. This force included a composite regiment of Australian light horse and the horse transport of the 1st Division. A series of sharp battles against the Arabs ensued at Um Rakhum, Gebel Medwa and Halazin during December and January. British casualties were comparatively light, although many were killed or wounded, including Australians. Arab losses were much higher however, with hundreds killed during the fighting. Meanwhile a number of the Australian Light Horse units returning from Gallipoli were sent further south to guard the edge of the Nile Valley against the Senussi. The 1st Armoured Car Section was also involved in guarding the Western Desert until it was sent to Palestine as the 1st Light Car Patrol at the end of 1916.

Battle of Romani

The Battle of Romani took place near the Egyptian town of Romani which lies 23 miles (37 km) east of the Suez CanalSuez Canal

The Suez Canal , also known by the nickname "The Highway to India", is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea. Opened in November 1869 after 10 years of construction work, it allows water transportation between Europe and Asia without navigation...

from 3–5 August 1916. The goal of Turkish army was to control or destroy the Suez Canal, thereby denying the use of the waterway to the Allies

Allies

In everyday English usage, allies are people, groups, or nations that have joined together in an association for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out between them...

and in doing so aiding the Central Powers

Central Powers

The Central Powers were one of the two warring factions in World War I , composed of the German Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulgaria...

. Both the Anzac Mounted Division, under Major General Chauvel, and the 52nd (Lowland) Division saw action against the Turkish division.

Since first making contact with the Turks on 20 July they had been harassed alternately by the Australian 1st and 2nd Light Horse Brigades but on the night of 3–4 August both brigades were involved. By about midday on 4 August, the Turkish division had pushed the two Australian brigades back to a point where the 52nd Infantry Division, in their trenches, were able to attack the Turkish right flank, and the New Zealand Mounted Rifle and 5th Mounted Brigades arrived to extend the Australians' line on the left flank. The Turkish advance was stopped by the fire brought to bear on them by these combined British infantry and Australian, British and New Zealand mounted forces and the deep sand, the midday summer heat, and thirst.

In these extremely tough conditions, the British infantry were unable to move effectively against the enemy the next day, and the Anzac Mounted Division was unable to stop the Turks making an orderly retreat to Katia and eventually back to their base at Bir el Abd. This base was abandoned on 12 August 1916 ending any threat to the Suez Canal for the remainder of the war. The battle cost the Allies 1,202 casualties of which 222 were killed, 71 died of wounds and 909 were wounded; half of these were Australians.

Battle of Magdhaba

Following the victory at Romani the Anzac Mounted DivisionAnzac Mounted Division

The ANZAC Mounted Division was a mounted infantry and mounted rifles division formed in March 1916 in Egypt during World War I following the Battle of Gallipoli when the Australian and New Zealand regiments returned from fighting dismounted as infantry...

pushed the Ottoman Army back across the Sinai Peninsula. The Turkish forces had been put on the defensive and retreated from Bir el Abd on 12 August 1916 towards the Egyptian–Ottoman Empire frontier; fighting a successful rearguard action at Bir el Mazar before retiring to El Arish in September, and in the Maghara Hills

Sinai and Palestine Campaign

The Sinai and Palestine Campaigns took place in the Middle Eastern Theatre of World War I. A series of battles were fought between British Empire, German Empire and Ottoman Empire forces from 26 January 1915 to 31 October 1918, when the Armistice of Mudros was signed between the Ottoman Empire and...

in October 1916 when a strongly defended position was attacked by an Allied force based on the Suez Canal. Both places were subsequently abandoned. During November, an aerial bombing raid by 5 B.E.'s and a Martinsyde, the largest air attack yet organised in the East was carried out on Beersheba

Beersheba

Beersheba is the largest city in the Negev desert of southern Israel. Often referred to as the "Capital of the Negev", it is the seventh-largest city in Israel with a population of 194,300....

. By the beginning of December the railway had reached El Mazar along with lines of communication garrisons, support and services and it became possible to plan for an advance to El Arish.

On 21 December after a night march of 30 miles the Anzac Mounted Division

Anzac Mounted Division

The ANZAC Mounted Division was a mounted infantry and mounted rifles division formed in March 1916 in Egypt during World War I following the Battle of Gallipoli when the Australian and New Zealand regiments returned from fighting dismounted as infantry...

commanded by Major General Chauvel entered El Arish, which had been abandoned by the Turks, who had retreated to Madghaba where the mounted force won a fierce daylong engagement against strong well constructed defences manned by determined defenders.

Major General Chauvel with the agreement of General Chetwode

Philip Chetwode, 1st Baron Chetwode

Field Marshal Philip Walhouse Chetwode, 1st Baron Chetwode, 7th Baronet of Oakley, GCB, OM, GCSI, KCMG, DSO was a British cavalry officer who became Commander in Chief in India.-Early life and education:...

commanding Desert Column who had arrived that day, set out to attack the Turkish forces at Magdhaba with the Anzac Mounted Division

Anzac Mounted Division

The ANZAC Mounted Division was a mounted infantry and mounted rifles division formed in March 1916 in Egypt during World War I following the Battle of Gallipoli when the Australian and New Zealand regiments returned from fighting dismounted as infantry...

. Leaving at about midnight on 22 December, the Anzac Mounted Division was in a position by 0350 on 23 December, to see enemy fires still some miles away at Magdhaba.

With the 1st Light Horse Brigade

1st Light Horse Brigade

The 1st Light Horse Brigade was a mounted infantry brigade of the First Australian Imperial Force which served in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I. The brigade first saw action during the Dardanelles Campaign in the Battle of Gallipoli. After being withdrawn to Egypt in February 1916 they...

in reserve, Major General Chauvel sent the New Zealand Mounted Rifles

New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade

The New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade, consisting usually of four units of mounted infantry, fought in World War I and World War II. Initially a milita, under the instruction of Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Henry Banks they formed the core of the New Zealand Army following successful service in the...

and the 3rd Light Horse Brigade

3rd Light Horse Brigade

The 3rd Light Horse Brigade was a mounted infantry brigade of the First Australian Imperial Force which served in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I....

s to move on Magdhaba by the north and north–east to cut off the possibility of retreat while the Imperial Camel Corps

Imperial Camel Corps

The Imperial Camel Corps was a brigade-sized military formation which fought for the Allies in the Sinai and Palestine Campaign in World War I. Its personnel were infantry mounted on camels for movement across desert....

Brigade followed the telegraph line straight on Magdhaba. The 1st Light Horse Brigade reinforced the Imperial Camel Corps Brigade in an attack on the redoubt but fierce shrapnel fire forced them to advance up the wadi bed. By midday all three brigades and the Camel Brigade, with Vickers and Lewis Gun sections and HAC artillery were hotly engaged. Aerial reconnaissance to scout out the Turkish positions greatly assisted the attack, although enemy positions were well camouflaged.

When the fighting began the going was tough and by one o'clock in the afternoon, after hearing that the enemy still had possession of most of the water in the area, its claimed Major General Chauvel decided to call off the attack. In any case, after a telephone call between Major General Chauvel and Lieutenant General Chetwode pressure was continued to be pressed and an attack by all units took place by which time there was no doubt that the enemy was losing the fight. Both the 1st Light Horse and the New Zealand Mounted Rifle Brigades made progress capturing about 100 prisoners and by 3.30 pm the Turks were beginning to surrender. By 4:30 pm, the Turkish garrison surrendered, having suffered heavy casualties, and the town was captured. The victory had cost 22 dead and 121 wounded.

Battle of Rafa

Two and a half weeks later, on the evening of 8 January 1917 the mounted units of Desert Column commanded by Lieutenant General ChetwodePhilip Chetwode, 1st Baron Chetwode

Field Marshal Philip Walhouse Chetwode, 1st Baron Chetwode, 7th Baronet of Oakley, GCB, OM, GCSI, KCMG, DSO was a British cavalry officer who became Commander in Chief in India.-Early life and education:...

rode out of El Arish towards Rafa where a 2,000-strong Turkish garrison was based. The attacking force comprised the Australian 1st Light Horse Brigade

1st Light Horse Brigade

The 1st Light Horse Brigade was a mounted infantry brigade of the First Australian Imperial Force which served in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I. The brigade first saw action during the Dardanelles Campaign in the Battle of Gallipoli. After being withdrawn to Egypt in February 1916 they...

, 3rd Light Horse Brigade

3rd Light Horse Brigade

The 3rd Light Horse Brigade was a mounted infantry brigade of the First Australian Imperial Force which served in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I....

and the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade of the Anzac Mounted Division

Anzac Mounted Division

The ANZAC Mounted Division was a mounted infantry and mounted rifles division formed in March 1916 in Egypt during World War I following the Battle of Gallipoli when the Australian and New Zealand regiments returned from fighting dismounted as infantry...

under the command of Major General Chauvel, the British 5th Mounted (Yeomanry) Brigade and three battalions of the Imperial Camel Corps Brigade.

After a long night march, the Allied force attacked the strongly entrenched position at El Magruntein. A fierce day-long battle resulted in the mounted troops (fighting dismounted) capturing the town around nightfall with the loss of 71 killed and 415 wounded. The Turkish garrison suffered heavily, with 200 killed and another 1,600 taken prisoner.

Fighting around Gaza, 1917

In early 1917, the Imperial Mounted Division was formed from the 3rd and 4th Light Horse Brigade4th Light Horse Brigade

The 4th Light Horse Brigade was a mounted infantry brigade of the First Australian Imperial Force serving in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I. The brigade was formed in March 1915 and shipped to Egypt without their horses and was broken up in Egypt in August 1915...

s and two British mounted brigades. The division first saw service during the First Battle of Gaza

First Battle of Gaza

The First Battle of Gaza was fought in and around the town of Gaza on the Mediterranean coast in the southern region of Ottoman Palestine on 26 March 1917, during World War I...

, which occurred in southern Gaza

Gaza

Gaza , also referred to as Gaza City, is a Palestinian city in the Gaza Strip, with a population of about 450,000, making it the largest city in the Palestinian territories.Inhabited since at least the 15th century BC,...

on 26 March 1917. At around noon two mounted brigades of the Anzac Mounted Division attacked Gaza from the north and east. At 6.00 pm the Turkish position had become perilous with the ring closing tightly around Gaza. However, in a decision that dismayed most of their soldiers the British commanders decided to call off the attack and retreat, delivering victory to the Turks. A second attempt was made to capture Gaza on 19 April by which time the Turkish defences were even more formidable and the task confronting the British even more difficult. This battle became known as the Second Battle of Gaza

Second Battle of Gaza

The Second Battle of Gaza, fought in southern Palestine during the First World War, was another attempt mounted by British Empire forces to break Ottoman defences along the Gaza-Beersheba line...

. The Anzac Mounted Division played only a minor role in this battle suffering only 105 casualties out of the 5,917 suffered. The second battle of Gaza was a disastrous defeat for the Allied forces.

Australian Mounted Division

The Australian Mounted Division was a mounted infantry division formed in Egypt during World War I. When the British forces in the Middle East expanded in late 1916, a second mounted division was created called the Imperial Mounted Division...

. In August 1917 Chauvel was placed in command of the Desert Mounted Corps

Desert Mounted Corps

The Desert Mounted Corps was a World War I Allied army corps that operated in the Middle East during 1917 and 1918.Originally formed on 15 March 1916 as the Australian and New Zealand Mounted Division under the command of Major General Harry Chauvel The Desert Mounted Corps was a World War I...

, which included the two Australian mounted divisions, as well as the British Yeomanry Division and the Imperial Camel Corps Brigade. Chauvel became the first Australian to command a corps, as well as the first to achieve the rank of lieutenant-general.

With the failure of the Second Battle of Gaza a third assault

Third Battle of Gaza

The Third Battle of Gaza was fought in 1917 in southern Palestine during the First World War. The British Empire forces under the command of General Edmund Allenby successfully broke the Ottoman defensive Gaza-Beersheba line...

was launched on Gaza between 31 October and 7 November 1917. Units from the Anzac Mounted Division and the Australian Mounted Division took part in the battle. The battle was a complete success for the Allies. The Gaza–Beersheba line was completely overrun and 12,000 Turkish soldiers were captured or surrendered. The critical moment of the battle was the capture of the town of Beersheba on the first day by Australian light horsemen. The Australian 4th Light Horse Brigade, under Brigadier General William Grant

William Grant (General)

Brigadier General William Grant CMG, DSO and Bar, MBE was an Australian Army colonel and temporary Brigadier General in World War I.-Early life and career:...

, charged more than 4 miles (6.4 km) at the Turkish trenches, overran them and captured the wells at Beersheba. In the capture of Beersheba, the Australians lost 31 men killed. A further 32 were wounded, while 80 horses were lost. On the Turkish side, more than 500 men were killed and 1,500 captured as well as nine artillery pieces and a number of machine guns and other pieces of equipment.

Fighting advance

From 1 to 7 November, strong Ottoman rearguards at Tel el Khuweilfe in the southern Judean Hills, at Hareira and Sheria on the maritime plain and at Sausage RidgeSecond Battle of Gaza

The Second Battle of Gaza, fought in southern Palestine during the First World War, was another attempt mounted by British Empire forces to break Ottoman defences along the Gaza-Beersheba line...

and Gaza

Gaza

Gaza , also referred to as Gaza City, is a Palestinian city in the Gaza Strip, with a population of about 450,000, making it the largest city in the Palestinian territories.Inhabited since at least the 15th century BC,...

close to the Mediterranean

Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean surrounded by the Mediterranean region and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Anatolia and Europe, on the south by North Africa, and on the east by the Levant...

coast, held the Egyptian Expeditionary Force

Egyptian Expeditionary Force

The Egyptian Expeditionary Force was formed in March 1916 to command the British and British Empire military forces in Egypt during World War I. Originally known as the 'Force in Egypt' it had been commanded by General Maxwell who was recalled to England...

in heavy fighting. During this time the Ottoman Army was able to withdraw in good order. The rearguard garrisons themselves were also able to retire under cover of darkness, during the night of 6/7 or 7/8 November.

On 7 and 8 November the surviving units of the 7th

Seventh Army (Ottoman Empire)

The Ottoman Seventh Army was a large military formation of Ottoman Empire in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Although designated as an army, at least by 1918, it was only of corps strength....

and 8th

Eighth Army (Ottoman Empire)

The Eighth Army of the Ottoman Empire was one of the field armies of the Ottoman Army. It was formed during the World War I.- Order of Battle, January 1918 :In January 1918, the army was structured as follows:...

Ottoman armies further delayed the advance of Desert Mounted Corps

Desert Mounted Corps

The Desert Mounted Corps was a World War I Allied army corps that operated in the Middle East during 1917 and 1918.Originally formed on 15 March 1916 as the Australian and New Zealand Mounted Division under the command of Major General Harry Chauvel The Desert Mounted Corps was a World War I...

commanded by Lieutenant General

Lieutenant General (Australia)

Lieutenant general is the second-highest active rank of the Australian Army and was created as a direct equivalent of the British military rank of lieutenant general. It is also considered a three-star rank....

Henry George Chauvel and the XXI Corps

XXI Corps (United Kingdom)

The XXI Corps was a Army Corps of the British Army during World War I.-First World War:The Corps was formed in Egypt in June 1917 under the command of Lieutenant General Edward Bulfin...

's 52nd (Lowland) Infantry Division commanded by Major General

Major General

Major general or major-general is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. A major general is a high-ranking officer, normally subordinate to the rank of lieutenant general and senior to the ranks of brigadier and brigadier general...

Edmund Hakewill-Smith

Edmund Hakewill-Smith

Major-General Sir Edmund Hakewill-Smith KCVO, CB, CBE, MC was a South African-born British General.-Early life:Hakewill-Smith was born in Kimberley, Northern Cape, South Africa, on the 17 March 1896, he was educated at the Diocesan College in Rondebosch, Cape Town, South Africa and at the RMC...

and the 75th Yeomanry Infantry Division

75th Division (United Kingdom)

The 75th Division was a war formed division of the British Army during World War I. They served in the Middle East during the Sinai and Palestine Campaign being involved in the Battle of Megiddo .-Formation 1918:Commander Major General P C Palin...

commanded by Major General P. C. Palin.

All other units of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force

Egyptian Expeditionary Force

The Egyptian Expeditionary Force was formed in March 1916 to command the British and British Empire military forces in Egypt during World War I. Originally known as the 'Force in Egypt' it had been commanded by General Maxwell who was recalled to England...

had come to the end of their lines of communication

Line of communication

A line of communication is the route that connects an operating military unit with its supply base. Supplies and reinforcements are transported along the line of communication. Therefore, a secure and open line of communication is vital for any military force to continue to operate effectively...