.gif)

History of the United States (1789–1849)

Encyclopedia

With the election of George Washington

as the first president

in 1789, the new government acted quickly to rebuild the nation's financial structure. Enacting the program of Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton

, the government assumed the Revolutionary war debts of the state and the national government, and refinanced them with new federal bonds. It paid for the program through new tariffs and taxes, especially the controversial Whiskey Tax

. Congress adopted and sent to the states a Bill of Rights

as 10 amendments to the new constitution; these amendments, written by Madison, are the U.S. Bill of Rights

. President Washington set up a cabinet form of government, with departments of State, Treasury, and War, along with an Attorney General (the Justice Department was created in 1870). The Judiciary Act of 1789

established the entire federal judiciary

, including the Supreme Court

. The Court became important under the leadership of Chief Justice John Marshall

(1801–1834), Federalist and nationalist who built a strong Supreme Court and strengthened the national government.

The 1790s were highly contentious, as the First Party System

emerged in the contest between Alexander Hamilton

and his Federalist party, and Thomas Jefferson

and his Republican party. Washington and Hamilton were building a strong national government, with a broad financial base, and the support of merchants and financiers throughout the country. Jeffersonians opposed the new national Bank, the Navy, and federal taxes. The Federalists favored Britain, which was embattled in a series of wars with France. Jefferson's victory in 1800 opened the era of Jeffersonian democracy

, and doomed the upper-crust Federalists to increasingly marginal roles.

The Louisiana Purchase

, in 1803 opened vast Western

expanses of fertile land, that exactly met the needs of the rapidly expanding population of yeomen farmers

whom Jefferson championed.

The Americans declared war on Britain (the War of 1812

) to uphold American honor at sea, and to end the Indian raids in the west. Despite incompetent government management, and a series of defeats early on, Americans found new generals like Andrew Jackson

, William Henry Harrison

, and Winfield Scott

, who repulsed British invasions and broke the alliance between the British and the Indians that held up settlement of the Old Northwest. The Federalists, who had opposed the war to the point of trading with the enemy and threatening secession, were devastated by the triumphant ending of the war. The remaining Indians east of the Mississippi were kept on reservations or moved via the Trail of Tears

to reservations in what later became Oklahoma.

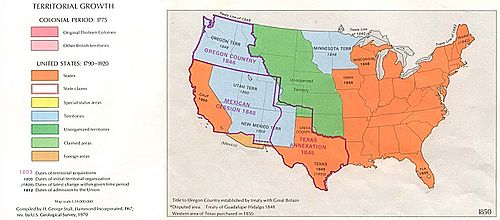

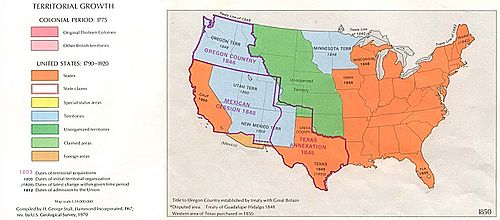

The spread of democracy opened the ballot box to nearly all white men, allowing the Jacksonian democracy

to dominate politics during the Second Party System

. Whigs, representing wealthier planters, merchants, financiers and professionals, wanted to modernize the society, using tariffs and federally funded internal improvements

; they were blocked by the Jacksonians, who closed down the national Bank in the 1830s. The Jacksonians wanted expansion—that is "Manifest Destiny

"—into new lands that would be occupied by farmers and planters. Thanks to the annexation of Texas, the defeat of Mexico in war, and a compromise with Britain, the western third of the nation rounded out the continental United States by 1848.

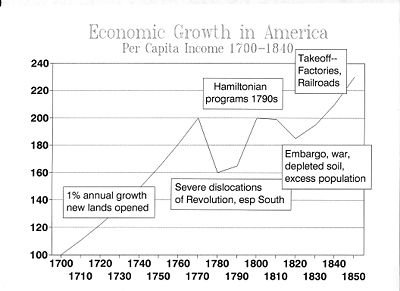

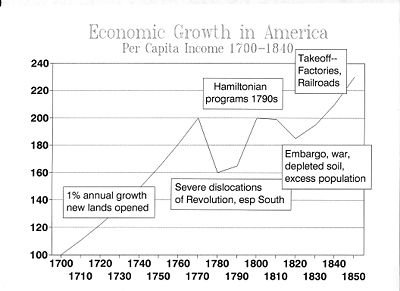

Howe (2007) argues that the transformation America underwent was not so much political democratization but rather the explosive growth of technologies and networks of infrastructure and communication—the telegraph, railroads, the post office, and an expanding print industry. They made possible the religious revivals of the Second Great Awakening

, the expansion of education and social reform. They modernized party politics, as speeded up business by enabling the fast, efficient movement of goods, money and people across an expanding nation. They transformed a loose-knit collection of parochial agricultural communities into a powerful cosmopolitan nation Economic modernization proceeded rapidly, thanks to highly profitable cotton crops in the South, new textile and machine-making industries in the Northeast, and a fast developing transportation infrastructure.

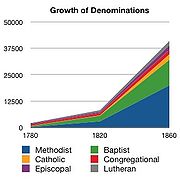

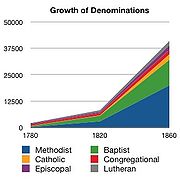

Breaking loose from European models, the Americans developed their own high culture, notably in literature and in higher education. The Second Great Awakening

brought revivals across the country, forming new denominations and greatly increasing church membership, especially among Methodists and Baptists. By the 1840s increasing numbers of immigrants were arriving from Europe, especially British, Irish, and Germans. Many settled in the cities, which were starting to emerge as a major factor in the economy and society.

The Whigs had warned that annexation of Texas would lead to a crisis over slavery, and they were proven right by the turmoil of the 1850s that led to civil war.

.jpg)

George Washington, a renowned hero of the American Revolutionary War

, commander of the Continental Army

, and president of the Constitutional Convention

, was unanimously chosen as the first President of the United States

under the new U.S. Constitution. All the leaders of the new nation were committed to republicanism

, and the doubts of the Anti-Federalists of 1788 were allayed with the passage of a Bill of Rights

as the first 10 amendments to the Constitution in 1791.

The first census, conducted by Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson

, enumerated a population of 3.9 million, with a density of 4.5 people per square mile of land area. There were only 12 cities of more than 5,000 population, as the great majority of the people were farmers.

Congress passed the Judiciary Act of 1789

, which established the entire federal judiciary

. At the time, the act provided for a Supreme Court of six justices, three circuit courts

, and 13 district courts

. It also created the offices of U.S. Marshal

, Deputy Marshal, and District Attorney

in each federal judicial district

. The Compromise of 1790

located to the national capital in the southern state of Maryland (now the District of Columbia), and enabled the federal assumption of state debts.

Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton

, with Washington's support and Jefferson's opposition, convinced Congress to pass a far-reaching financial program that funded the debts of the American Revolution, set up a national bank, and set up a system of tariffs and taxes to pay for all. His policies had the effect of linking the economic interests of the states, and of wealthy Americans, to the success of the national government, as well as enhancing the international financial standing of the new nation.

The Whiskey Rebellion

in 1794—when settlers in the Monongahela Valley of western Pennsylvania protested against the new federal tax on whiskey, which the settlers shipped across the mountains to earn money. It was the first serious test of the federal government. Washington ordered federal marshals to serve court orders requiring the tax protesters to appear in federal district court. By August 1794, the protests became dangerously close to outright rebellion, and on August 7, several thousand armed settlers gathered near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

. Washington then invoked the Militia Law of 1792 to summon the militias of several states. A force of 13,000 men was organized, and Washington personally led it to Western Pennsylvania

. The revolt immediately collapsed, and there was no violence.

Foreign policy unexpectedly took center stage starting in 1793, when revolutionary France and conservative Britain went to war, opening a period of intense European conflict that lasted until 1815. The American policy was, "remain neutral", but the Jeffersonians strongly favored France, and deeply distrusted the British, who they saw as enemies of Republicanism. Hamilton and the business community favored Britain, which was by far America's largest trading partner. The tensions with Britain were resolved with the Jay Treaty of 1794, which opened up 10 years of prosperous trade, and forced the British to withdraw from their forts in the American Far West. The Jeffersonians tried to defeat the treaty, but failed when Washington threw his prestige into the conflict.

Continuing conflict between Hamilton and Jefferson, especially over foreign policy, led to the formation of the Federalist and Republican parties. Although Washington warned against political parties in his farewell address

, he generally supported Hamilton and Hamiltonian programs over those of Jefferson. After his death in 1799 he became the great symbolic hero of the Federalists.

was created by Alexander Hamilton

and was dominant to 1800. The rival Republican Party

(Democratic-Republican Party) was created by Thomas Jefferson

and James Madison

, and was dominant after 1800. Both parties originated in national politics but moved to organize supporters and voters in every state. These comprised "probably the first modern party system in the world" because they were based on voters, not factions of aristocrats at court or parliament. The Federalists appealed to the business community, the Republicans to the planters and farmers. By 1796 politics in every state was nearly monopolized by the two parties.

Jefferson wrote on Feb. 12, 1798:

The Federalists promoted the financial system of Treasury Secretary Hamilton, which emphasized federal assumption of state debts, a tariff to pay off those debts, a national bank to facilitate financing, and encouragement of banking and manufacturing. The Republicans, based in the plantation South, opposed a strong executive power, were hostile to a standing army and navy, demanded a limited reading of the Constitutional powers of the federal government, and strongly opposed the Hamilton financial program. Perhaps even more important was foreign policy, where the Federalists favored Britain because of its political stability and its close ties to American trade, while the Republicans admired the French and the French Revolution. Jefferson was especially fearful that British aristocratic influences would undermine republicanism

. Britain and France were at war 1793–1815, with one brief interruption. American policy was neutrality, with the federalists hostile to France, and the Republicans hostile to Britain. The Jay Treaty

of 1794 marked the decisive mobilization of the two parties and their supporters in every state. President Washington, while officially nonpartisan, generally supported the Federalists and that party made Washington their iconic hero.

Washington retired in 1797, firmly declining to serve for more than eight years as the nation's head. Vice President John Adams

Washington retired in 1797, firmly declining to serve for more than eight years as the nation's head. Vice President John Adams

was elected the new President, narrowly defeating Jefferson. Even before he entered the presidency, Adams had quarreled with Alexander Hamilton

—and thus was handicapped by a divided Federalist party.

These domestic difficulties were compounded by international complications: France, angered by American approval in 1795 of the Jay Treaty

with its great enemy Britain proclaimed that food and war material bound for British ports were subject to seizure by the French navy. By 1797, France had seized 300 American ships and had broken off diplomatic relations with the United States. When Adams sent three other commissioners to Paris to negotiate, agents of Foreign Minister Charles Maurice de Talleyrand (whom Adams labeled "X, Y and Z" in his report to Congress) informed the Americans that negotiations could only begin if the United States loaned France $12 million and bribed officials of the French government. American hostility to France rose to an excited pitch. Federalists used the "XYZ Affair

" to create a new American army, strengthen the fledgling United States Navy

, impose the Alien and Sedition Acts

to stop pro-French activities (which had severe repercussions for American civil liberties

), and enact new taxes to pay for it. The Naturalization Act

, which changed the residency requirement for citizenship from five to 14 years, was targeted at Irish and French immigrants suspected of supporting the Republican Party

. One of the Alien acts, still in effect in the 21st century, gave the President the power to expel or imprison aliens in time of war. The Sedition Act proscribed writing, speaking or publishing anything of "a false, scandalous and malicious" nature against the President or Congress. The few convictions won under the Sedition Act only created martyrs to the cause of civil liberties and aroused support for the Republicans. Jefferson and his allies launched a counterattack, with two states stating in the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions

that state legislatures could nullify acts of Congress. However, all the other states rejected this proposition, and nullification—or it was as it was called, the "principle of 98"—became the preserve of a faction of the Republicans

called the Quids.

In 1799, after a series of naval battles with the French (known as the Quasi-War

), full-scale war seemed inevitable. In this crisis, Adams broke with his party and sent three new commissioners to France. Napoleon, who had just come to power, received them cordially, and the danger of conflict subsided with the negotiation of the Convention of 1800, which formally released the United States from its 1778 wartime alliance with France. However, reflecting American weakness, France refused to pay $20 million in compensation for American ships seized by the French navy.

In his final hours in office, Adams appointed John Marshall

as chief justice. Serving until his death in 1835, Marshall dramatically expanded the powers of the Supreme Court and provided a Federalist interpretation of the Constitution that made for a strong national government.

Under Washington and Adams the Federalists had established a strong government, but sometimes it followed policies that alienated the citizenry. For example, in 1798, to pay for the rapidly expanding army and navy, the Federalists had enacted a new tax on houses, land and slaves, affecting every property owner in the country. In the Fries's Rebellion hundreds of farmers in Pennsylvania revolted--Federalists saw a breakdown in civil society. Some tax resisters were arrested--then pardoned by Adams. Republicans denounced this action as an example of Federalist tyranny.

Under Washington and Adams the Federalists had established a strong government, but sometimes it followed policies that alienated the citizenry. For example, in 1798, to pay for the rapidly expanding army and navy, the Federalists had enacted a new tax on houses, land and slaves, affecting every property owner in the country. In the Fries's Rebellion hundreds of farmers in Pennsylvania revolted--Federalists saw a breakdown in civil society. Some tax resisters were arrested--then pardoned by Adams. Republicans denounced this action as an example of Federalist tyranny.

Jefferson had steadily gathered behind him a great mass of small farmers, shopkeepers and other workers which asserted themselves as Democratic-Republicans in the election of 1800. Jefferson enjoyed extraordinary favor because of his appeal to American idealism. In his inaugural address, the first such speech in the new capital of Washington, DC, he promised "a wise and frugal government" to preserve order among the inhabitants but would "leave them otherwise free to regulate their own pursuits of industry, and improvement".

Jefferson encouraged agriculture and westward expansion, most notably by the Louisiana Purchase and subsequent Lewis and Clark Expedition

. Believing America to be a haven for the oppressed, he reduced the residency requirement for naturalization back to five years again.

By the end of his second term, Jefferson and Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin

had reduced the national debt to less than $560 million. This was accomplished by reducing the number of executive department employees and Army and Navy officers and enlisted men, and by otherwise curtailing government and military spending.

To protect its shipping interests overseas, the U.S. fought the First Barbary War

(1801–1805) in North Africa

. This was followed later by the Second Barbary War

(1815).

With the upcoming expiration of the 20-year ban on Congressional action on the subject, Jefferson, a lifelong enemy of the slave trade, calls on Congress to criminalize the international slave trade, calling it "violations of human rights which have been so long continued on the unoffending inhabitants of Africa, and which the morality, the reputation, and the best interests of our country have long been eager to proscribe."

s and to profit from transporting goods between their home markets and Caribbean

colonies. Both sides permitted this trade when it benefited them but opposed it when it did not. Following the 1805 destruction of the French navy at the Battle of Trafalgar

, Britain sought to impose a stranglehold over French overseas trade ties. Thus, in retaliation against U.S. trade practices, Britain imposed a loose blockade

of the American coast. Believing that Britain could not rely on other sources of food than the United States, Congress and President Jefferson suspended all U.S. trade with foreign nations in the Embargo Act of 1807

, hoping to get the British to end their blockade of the American coast. The Embargo Act, however, devastated American agricultural exports and weakened American ports while Britain found other sources of food.

James Madison

won the U.S. presidential election of 1808, largely on the strength of his abilities in foreign affairs at a time when Britain and France were both on the brink of war with the United States. He was quick to repeal the Embargo Act, refreshing American seaports.

In response to continued British interference with American shipping (including the practice of impressment

In response to continued British interference with American shipping (including the practice of impressment

of American sailors into the British Navy), and to British aid to American Indians in the Old Northwest, the Twelfth Congress—led by Southern and Western Jeffersonians—declared war on Britain in 1812. Westerners and Southerners were the most ardent supporters of the war, given their concerns about defending national honor and expanding western settlements, and having access to world markets for their agricultural exports. New England

was making a fine profit and its Federalists opposed the war, almost to the point of secession. The Federalist reputation collapsed in the triumphalism of 1815 and the party no longer played a national role.

The United States and Britain came to a draw in the war after bitter fighting that lasted even after the Burning of Washington

in August 1814 and Andrew Jackson

's smashing defeat of the British invasion army at the Battle of New Orleans

in January 1815. The Treaty of Ghent

, officially ending the war, returned to the status quo ante bellum

, but Britain's alliance with the Native Americans ended, and the Indians were the major losers of the war. News of the victory at New Orleans over the best British combat troops came at the same time as news of the peace, giving Americans a psychological triumph and opening the Era of Good Feelings

. The war destroyed the Federalist Party, and opened roles as national candidates to generals Andrew Jackson

and William Henry Harrison

among others, as well as civilian leaders James Monroe, John Quincy Adams, and Henry Clay.

, America began to assert a newfound sense of nationalism. America began to rally around national heroes such as Andrew Jackson

and patriotic feelings emerged in such works as Francis Scott Key

's poem The Star Spangled Banner. Under the direction of Chief Justice John Marshall

, the Supreme Court issued a series of opinions reinforcing the role of the national government. These decisions included McCulloch v Maryland and Gibbons v Ogden; both of which reaffirmed the supremacy of the national government over the states. The signing of the Adams-Onis Treaty

helped to settle the western border of the country through popular and peaceable means.

increased across the country, its effects were limited by a renewed sense of sectionalism

. The New England

states that had opposed the War of 1812 felt an increasing decline in political power with the demise of the Federalist Party. This loss was tempered with the arrival of a new industrial movement and increased demands for northern banking. The industrial revolution

in the United States was advanced by the immigration of Samuel Slater

from Great Britain and arrival of textile mills beginning in Lowell, Massachusetts

. In the south, the invention of the cotton gin

by Eli Whitney

radically increased the value of slave labour. The export of southern cotton

was now the predominant export of the U.S. The western states continued to thrive under the "frontier spirit." Individualism was prized as exemplified by Davey Crockett and James Fenimore Cooper

's folk hero Natty Bumpo from The Leatherstocking Tales. Following the death of Tecumseh

in 1813, Native Americans lacked the unity to stop white settlement.

(1817–1825) was hailed at the time and since as the "Era of Good Feelings" because of the decline of partisan politics and heated rhetoric after the war. The Federalist Party collapsed, but without an opponent the Republican party decayed as sectional interests came to the fore.

The Monroe Doctrine

was drafted by Secretary of State John Quincy Adams

in collaboration with the British, and proclaimed by Monroe in late 1823. He asserted the Americas should be free from additional European colonization and free from European interference in sovereign countries' affairs. It further stated the United States' intention to stay neutral in wars between European powers and their colonies but to consider any new colonies or interference with independent countries in the Americas as hostile acts towards the United States. No new colonies were ever formed.

. From Kentucky came Speaker of the House

Henry Clay

, while Massachusetts produced Secretary of State Adams; a rump congressional caucus put forward Treasury Secretary

William H. Crawford

. Personality and sectional allegiance played important roles in determining the outcome of the election. Adams won the electoral votes from New England and most of New York; Clay won his western base of Kentucky, Ohio and Missouri; Jackson won his base in the Southeast, and plus Illinois, Indiana, North Carolina, South Carolina, Pennsylvania, Maryland and New Jersey; and Crawford won his base in the South, Virginia, Georgia and Delaware. No candidate gained a majority in the Electoral College, so the president was selected by the House of Representatives, where Clay was the most influential figure. In return for Clay's support, which won him the presidency, John Quincy Adams

appointed Clay as secretary of state in what Jacksonians denounced as The Corrupt Bargain

.

During Adams' administration, new party alignments appeared. Adams' followers took the name of "National Republicans

", to reflect the mainstream of Jeffersonian Republicanism. Though he governed honestly and efficiently, Adams was not a popular president, and his administration was marked with frustrations. Adams failed in his effort to institute a national system of roads and canals as part of the American System

economic plan. His coldly intellectual temperament did not win friends.

rallied his followers in the newly emerging Democratic Party. In the election of 1828, Jackson defeated Adams by an overwhelming electoral majority. The election saw the coming to power of Jacksonian Democracy

, thus marking the transition from the First Party System

(which reflected Jeffersonian Democracy

) to the Second Party System

. Historians debate the significance of the election, with many arguing that it marked the beginning of modern American politics, with the decisive establishment of democracy and the formation of the two party system.

nation built on finance and manufacturing. The entrepreneurs, for whom Henry Clay

and Daniel Webster

were heroes, fought back and formed the Whig party.

Political machines appeared early in the history of the United States, and for all the exhortations of Jacksonian Democracy, it was they and not the average voter that nominated candidates. In addition, the system supported establishment politicians and party loyalists, and much legislation was designed to reward rich men and businesses who supported a particular party or candidate. Also during this period, a series of reforms resulted in changes to the electoral system which rewarded winners or plurality getters in smaller districts instead of the old method of dividing state offices among the biggest vote getters. As a consequence, the chance of single issue and ideology-based candidates being elected to major office dwindled and so those parties who were successful were pragmatist ones with no fixed beliefs.

Examples of single issue parties included the Anti-Masons, who emerged as a group set to outlaw Freemasonry

in the United States after a man who threatened to expose the Masons' secrets was kidnapped and murdered. They ran a candidate for president (William Wirt

) in 1832, but succeeded in only winning the state of Vermont and then quietly disappeared. Others included abolitionist parties, socialists like the Workingmen's Party, the Locofocos

(who opposed monopoly capitalism), and assorted nativist parties whose chief object was opposition to the Roman Catholic Church in the US. As pointed out above, none of these parties were capable of mounting a broad enough appeal to voters or winning major elections.

The election of 1828 was a significant benchmark marking the climax of the trend toward broader voter eligibility and participation. Vermont

had universal male suffrage since its entry into the Union, and Tennessee permitted suffrage for the vast majority of taxpayers. New Jersey, Maryland and South Carolina all abolished property and tax-paying requirements between 1807 and 1810. States entering the Union after 1815 either had universal white male suffrage or a low taxpaying requirement. From 1815 to 1821, Connecticut

, Massachusetts and New York abolished all property requirements. In 1824, members of the Electoral College were still selected by six state legislatures. By 1828, presidential electors were chosen by popular vote in every state but Delaware and South Carolina. Nothing dramatized this democratic sentiment more than the election of Andrew Jackson.

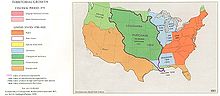

, which authorized the President to negotiate treaties that exchanged Indian tribal lands in the eastern states for lands west of the Mississippi River. In 1834, a special Indian territory

was established in what is now the eastern part of Oklahoma

. In all, Native American tribes signed 94 treaties during Jackson's two terms, ceding thousands of square miles to the Federal government.

The Cherokee

s insisted on their independence from state government authority and faced expulsion from their lands when a faction of Cherokees signed the Treaty of New Echota

in 1835, obtaining money in exchange for their land. Despite protests from the elected Cherokee government and many white supporters, the Cherokees were forced to trek to the Indian Territory in 1838. Many died of disease and privation in what became known as the "Trail of Tears".

. The protective tariff passed by Congress and signed into law by Jackson in 1832 was milder than that of 1828, but it further embittered many in the state. In response, several South Carolina citizens endorsed the "states rights" principle of "nullification", which was enunciated by John C. Calhoun

, Jackson's Vice President until 1832, in his South Carolina Exposition and Protest

(1828). South Carolina dealt with the tariff by adopting the Ordinance of Nullification, which declared both the Tariff of 1828

and the Tariff of 1832

null and void within state borders.

Nullification was only the most recent in a series of state challenges to the authority of the federal government. In response to South Carolina's threat, Jackson sent seven small naval vessels and a man-of-war to Charleston

in November 1832. On December 10, he issued a resounding proclamation against the nullifiers. South Carolina, the President declared, stood on "the brink of insurrection and treason", and he appealed to the people of the state to reassert their allegiance to that Union for which their ancestors had fought.

Senator Henry Clay, though an advocate of protection and a political rival of Jackson, piloted a compromise measure through Congress. Clay's 1833 compromise tariff specified that all duties more than 20% of the value of the goods imported were to be reduced by easy stages, so that by 1842, the duties on all articles would reach the level of the moderate tariff of 1816.

The rest of the South declared South Carolina's course unwise and unconstitutional. Eventually, South Carolina rescinded its action. Jackson had committed the federal government to the principle of Union

supremacy. South Carolina, however, had obtained many of the demands it sought and had demonstrated that a single state could force its will on Congress.

. The First Bank of the United States

had been established in 1791, under Alexander Hamilton's guidance and had been chartered for a 20-year period. After the Revolutionary War, the United States had a large war debt to France and others, and the banking system of the fledgling nation was in disarray, as state banks printed their own currency, and the plethora of different bank notes made commerce difficult. Hamilton's national bank had been chartered to solve the debt problem and to unify the nation under one currency. While it stabilized the currency and stimulated trade, it was resented by Westerners and workers who believed that it was granting special favors to a few powerful men. When its charter expired in 1811, it was not renewed.

For the next few years, the banking business was in the hands of State-Chartered banks, which issued currency in excessive amounts, creating great confusion and fueling inflation and concerns that state banks could not provide the country with a uniform currency. the absence of a national bank during the War of 1812 greatly hindered financial operations of the government; therefore a second Bank of the United States was created in 1816.

From its inception, the Second Bank was unpopular in the newer states and territories and with less prosperous people everywhere. Opponents claimed the bank possessed a virtual monopoly over the country's credit and currency, and reiterated that it represented the interests of the wealthy elite. Jackson, elected as a popular champion against it, vetoed a bill to recharter the bank. He also personally detested banks due to a brush with bankruptcy in his youth. In his message to Congress, he denounced monopoly and special privilege, saying that "our rich men have not been content with equal protection and equal benefits, but have besought us to make them richer by act of Congress".

In the election campaign that followed, the bank question caused a fundamental division between the merchant, manufacturing and financial interests (generally creditors who favored tight money and high interest rates), and the laboring and agrarian sectors, who were often in debt to banks and therefore favored an increased money supply

and lower interest rates. The outcome was an enthusiastic endorsement of "Jacksonism". Jackson saw his reelection in 1832 as a popular mandate to crush the bank irrevocably; he found a ready-made weapon in a provision of the bank's charter authorizing removal of public funds.

In September 1833 Jackson ordered that no more government money be deposited in the bank and that the money already in its custody be gradually withdrawn in the ordinary course of meeting the expenses of government. Carefully-selected state banks, stringently restricted, were provided as a substitute. For the next generation, the US would get by on a relatively-unregulated state banking system. This banking system helped fuel westward expansion through easy credit, but kept the nation vulnerable to periodic panics. It was not until the Civil War

that the Federal government again chartered a national bank.

Jackson groomed Martin van Buren

as his successor, and he was easily elected president in 1836. However, a few months into his administration, the country fell into a deep economic slump known as the Panic of 1837

, caused in large part by excessive speculation. Banks failed and unemployment soared. Although the depression had its roots in Jackson's economic policies, van Buren was blamed for the disaster. In the 1840 presidential election, he was defeated by the Whig candidate William Henry Harrison. However, his presidency would prove a non-starter when he fell ill with pneumonia and died after only a month in office. John Tyler, his vice president, succeeded him. Tyler was not popular since he had not been elected to the presidency, and was widely referred to as "His Accidency". The Whigs expelled him, and he became a president without a party.

, Americans entered a period of rapid social change and experimentation. New social movements arose, as well as many new alternatives to traditional religious thought. This period of American history was marked by the destruction of some traditional roles of society and the erection of new social standards. One of the unique aspects of the Age of Reform was that it was heavily grounded in religion, in contrast to the anti-clericalism that characterized contemporary European reformers.

was a Protestant religious revival movement that flourished in 1800–1840 in every region. It expressed Arminian theology

by which every person could be saved through a direct personal confrontation with Jesus Christ during an intensely emotional revival meeting. Millions join the churches, often new denominations. Many converts believed that the Awakening heralded a new millennial age

, so that the Second Great Awakening stimulated the establishment of many reform movements designed to remedy the evils of society before the Second Coming of Jesus Christ. For example, the charismatic Charles Grandison Finney

, in upstate New York

and the Old Northwest was highly effective. At the Rochester

Revival of 1830, prominent citizens concerned with the city's poverty and absenteeism had invited Finney to the city. The wave of religious revival contributed to tremendous growth of the Methodist, Baptists, Disciples, and other evangelical denominations.

challenged the traditional beliefs of the Calvinist faith, the movement inspired other groups to call into question their views on religion and society. Many of these utopianist groups also believed in millennialism

which prophesied the return of Christ and the beginning of a new age. The Harmony Society

made three attempts to effect a millennial society with the most notable example at New Harmony, Indiana

. Later, Scottish industrialist Robert Owen

bought New Harmony and attempted to form a secular Utopian community there. Frenchman Charles Fourier

began a similar secular experiment with his "phalanxes" that were spread across the Midwestern United States. However, none of these utopian communities lasted very long except for the Shakers.

One of the earliest movements was that of the Shakers

in which members of a community held all of their possessions in "common

" and lived in a prosperous, inventive, self-supporting society, with no sexual activity. The Shakers, founded by an English immigrant to the United States Mother Ann Lee

, peaked at around 6,000 in 1850 in communities from Maine to Kentucky. The Shakers condemned sexuality

and demanded absolute celibacy

. New members could only come from conversions, and from children brought to the Shaker villages. The Shakers persisted into the 20th century, but lost most of their originality by the middle of the 19th century. They are famed for their artistic craftsmanship, especially their furniture and handicrafts.

The Perfectionist movement, led by John Humphrey Noyes

, founded the utopian Oneida Community

in 1848 with fifty-one devotees, in Oneida, New York

. Noyes believed that the act of final conversion led to absolute and complete release from sin. Though their sexual practices were unorthodox, the community prospered because Noyes opted for modern manufacturing. Eventually abandoning religion to become a joint-stock company, Oneida thrived for many years and continues today as a silverware

company.

Joseph Smith

also experienced a religious conversion in this era; under his guidance Mormon

history began. Because of their unusual beliefs, which included recognition of the Book of Mormon

as a supplement to the Bible, Mormons were rejected by mainstream Christians and forced to flee en masse from upstate New York to Ohio, to Missouri and then to Nauvoo, Illinois

, where Smith was killed and they were again forced to flee. They Settled around the Great Salt Lake

, then part of Mexico. In 1848, the region came under American control and later formed the Utah

Territory. National policy was to suppress polygamy, and Utah was only admitted as a state in 1896 after the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints backtracked from Smith's demand that all the leaders practice polygamy.

For Americans wishing to bridge the gap between the earthly and spiritual worlds, spiritualism

provided a means of communing with the dead. Spiritualists used mediums to communicate between the living and the dead through a variety of different means. The most famous mediums, the Fox sisters

claimed a direct link to the spirit world. Spiritualism would gain a much larger following after the heavy number of casualties during the Civil War; First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln

was a believer.

Other groups seeking spiritual awaking gained popularity in the mid-19th century. Philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson

began the American transcendentalist

movement in New England, to promote self-reliance and better understanding of the universe through contemplation of the over-soul

. Transcendentalism was in essence an American offshoot of the Romantic movement in Europe. Among transcendentalists' core beliefs was an ideal spiritual state that "transcends" the physical, and is only realized through intuition

rather than doctrine. Like many of the movements, the transcendentalists split over the idea of self-reliance. While Emerson and Henry David Thoreau

promoted the idea of independent living, George Ripley brought transcendentalists together in a phalanx at Brook Farm

to live cooperatively. Other authors such as Nathaniel Hawthorne

and Edgar Allan Poe

rejected transcendentalist beliefs.

So many of these new religious and spiritual groups began or concentrated within miles of each other in upstate New York that this area was nicknamed "the burned-over district

" because there were so few people left who had not experienced a conversion.

was common, although it was often class-based with the working class receiving little benefits. Instruction and curriculum were all locally determined and teachers were expected to meet rigorous demands of strict moral behaviour. Schools taught religious values and applied Calvinist philosophies of discipline which included corporal punishment

and public humiliation. In the South, there was very little organization of a public education system. Public schools were very rare and most education took place in the home with the family acting as instructors. The wealthier planter families were able to bring in tutors for instruction in the classics

but many yeoman farming families had little access to education outside of the family unit.

The reform movement in education began in Massachusetts

when Horace Mann

started the common school movement. Mann advocated a statewide curriculum and instituted financing of school through local property taxes. Mann also fought protracted battles against the Calvinist influence in discipline, preferring positive reinforcement to physical punishment. Most children learned to read and write and spell from Noah Webster

's Blue Backed Speller and later the McGuffey Readers

. The readings inculcated moral values as well as literacy. Most states tried to emulate Massachusetts, but New England retained its leadership position for another century. German immigrants brought in kindergartens and gymnasiums, while Yankee orators sponsored the Lyceum

movement that provided popular education for hundreds of towns and small cities.

, a Massachusetts woman who made an intensive study of the conditions that the mentally ill were kept in. Dix's report to the Massachusetts state legislature along with the development of the Kirkbride Plan

helped to alleviate the miserable conditions for many of the mentally ill. Although these facilities often fell short of their intended purpose, reformers continued to follow Dix's advocacy and call for increased study and treatment of mental illness.

During the building of the new republic, American women were able to gain a limited political voice in what is known as republican motherhood

. Under this philosophy, as promoted by leaders such as Abigail Adams

, women were seen as the protectors of liberty and republicanism. Mothers were charged with passing down these ideals to their children through instruction of patriotic thoughts and feelings. During the 1830s and 1840s, many of the changes in the status of women that occurred in the post-Revolutionary period—such as the belief in love between spouses and the role of women in the home—continued at an accelerated pace. This was an age of reform movements, in which Americans sought to improve the moral fiber of themselves and of their nation in unprecedented numbers. The wife's role in this process was important because she was seen as the cultivator of morality in her husband and children. Besides domesticity, women were also expected to be pious, pure, and submissive to men. These four components were considered by many at the time to be "the natural state" of womanhood, echoes of this ideology still existing today. The view that the wife should find fulfillment in these values is called the Cult of True Womanhood or the Cult of Domesticity

.

In the South, tradition still abounded with society women on the pedestal and dedicated to entertaining and hosting others. This phenomenon is reflected in the 1965 book, The Inevitable Guest, based on a collection of letters by friends and relatives in North

and South Carolina

to Miss Jemima Darby, a distant relative of the author.

Under the doctrine of two spheres, women were to exist in the “domestic sphere” at home while their husbands operated in the “public sphere” of politics and business. Women took on the new role of “softening” their husbands and instructing their children in piety and not republican values, while men handled the business and financial affairs of the family. Some doctors of this period even went so far as to suggest that women should not get an education, lest they divert blood away from the uterus to the brain and produce weak children. The coverture

laws ensured that men would hold political power over their wives.

, which was active in both North and South, tried to implement these ideas and established the colony of Liberia

in Africa as a means to repatriate slaves out of white society. Prominent leaders included Henry Clay

and President James Monroe

—who gave his name to Monrovia, the capital of Liberia. However after 1840 the abolitionists rejected the idea of repatriation to Africa.

The slavery abolitionist

movement among white Protestants was based on evangelical principles of the Second Great Awakening

. Evangelist Theodore Weld led abolitionist revivals that called for immediate emancipation

of slaves. William Lloyd Garrison

founded The Liberator, an anti-slavery newspaper, and the American Anti-Slavery Society

to call for abolition. A controversial figure, Garrison often was the focus of public anger. His advocacy of women's rights and inclusion of women in the leadership of the Society caused a rift within the movement. Rejecting Garrison's idea that abolition and women's rights were connected Lewis Tappan

broke with the Society and formed the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society

. Most abolitionists were not as extreme as Garrison, who vowed that "The Liberator" would not cease publication until slavery was abolished.

White abolitionists did not always face agreeable communities in the North. Garrison was almost lynched in Boston while newspaper publisher Elijah Lovejoy was killed in Alton, Illinois

. The anger over abolition even spilled over into Congress where a gag rule

was instituted to prevent any discussion of slavery on the floor of either chamber. Most whites viewed African-Americans as an inferior race and had little taste for abolitionists, often assuming that all were like Garrison. African-Americans had little freedom even in states where slavery was not permitted, being shunned by whites, subjected to discriminatory laws, and often forced to compete with Irish immigrants for menial, low-wage jobs. In the South meanwhile, planters argued that slavery was necessary to operate their plantations profitably and that emancipated slaves would attempt to Africanize the country as they had done in Haiti.

Both free-born African American

citizens and former slaves took on leading roles in abolitionism as well. By far the most prominent spokesperson for abolition in the African American community was Frederick Douglass

, an escaped slave whose eloquent condemnations of slavery drew both crowds of supporters as well as threats against his life. Douglass was a keen user of the printed word both through his newspaper The North Star and three best-selling autobiographies.

At one extreme David Walker

published An Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World calling for African American revolt against white tyranny. The Underground Railroad

helped some slaves out of the South through a series of trails and safe houses known as “stations.” Known as “conductors”, escaped slaves volunteered to return to the South to lead others to safety; former slaves, such as Harriet Tubman

, risked their lives on these journeys.

were southerners who moved North to advocate against slavery. The American Anti-Slavery Society welcomed women. Garrison along with Elizabeth Cady Stanton

and Lucretia Mott

were so appalled that women were not allowed to participate at the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London that they called for a women's rights convention in Seneca Falls, New York

. It was at this convention that Sojourner Truth

became recognized as a leading spokesperson for both abolition and women's rights. Women abolitionists increasingly began to compare women's situation with the plight of slaves. This new polemic squarely blamed men for all the restrictions of women's role, and argued that the relationship between the sexes was one-sided, controlling and oppressive. There were strong religious roots; most feminists emerged from the Quaker and Congregationalist churches in the Northeast.

condemned liquor as being a scourge on society and urged temperance among their followers. The state of Maine attempted in 1851 to ban alcohol sales and production entirely, but it met resistance and was abandoned. The prohibition movement was forgotten during the Civil War, but would return in the 1870s.

and railroads to ship goods more quickly. The government helped protect American manufacturers by passing a protective tariff.

".

The steady expansion and rapid population growth of the United States after 1815 contrasted sharply with static European societies, as visitors described the rough, sometimes violent, but on the whole hugely optimistic and forward-looking attitude of most Americans. While land ownership was something most Europeans could only dream of, contemporary accounts show that the average American farmer owned his land, fed his family afar more than European peasants, and could make provisions for land for his children. Europeans commonly talked of the egalitarianism of American society, which had no landed nobility and which theoretically allowed anyone regardless of birth to become successful. For example in Germany, the universities, the bureaucracy and the army officers required high family status; in Britain rich families purchased commissions in the army for their sons for tens of thousands of pounds. Rich merchants and factory owners did emerge in Europe, but they seldom had social prestige of political power. By contrast the US had more millionaires than any country in Europe by 1850. Most rich Americans had well-to-do fathers, but their grandfathers were of average wealth. Poor boys of the 1850s like Andrew Carnegie

and John D. Rockefeller

were two of the richest men in the world by 1900. Historians have emphasized that upward social mobility came in small steps over time, and over generations, with the Carnegie-like rags-to-riches scenario a rare one. Some ethnic groups (like Yankees, Irish and Jews) prized upward mobility, and emphasized education as the fastest route; other groups (such as Germans, Poles and Italians) emphasized family stability and home ownership more. Stagnant cities offered less mobility opportunities, leading the more ambitious young men to head to growth centers, often out west.

Westward expansion was mostly undertaken by groups of young families. Daniel Boone

was one frontiersman who pioneered the settlement of Kentucky. This pattern was followed throughout the West as American hunters and trappers traded with the Indians and explored the land. As skilled fighters and hunters, these Mountain Men trapped beaver in small groups throughout the Rocky Mountains

. After the demise of the fur trade

, they established trading posts throughout the west, continued trade with the Indians and served as guides and hunters for the western migration of settlers to Utah

, Oregon

and California

.

Americans asserted a right to colonize vast expanses of North America beyond their country's borders, especially into Oregon, California, and Texas

. By the mid-1840s, U.S. expansionism was articulated in the ideology of "Manifest Destiny

". The Oregon Territory had been jointly administered by the US and Great Britain since 1819, but the two nations fell into disputes over the territory. President Polk (Democrat) negotiated a compromise that gave half the area to the US, along the line of the current border with Canada.

American annexation of the Republic of Texas

in 1845 was unacceptable to Mexico and led to war. In May 1846, Congress declared war on Mexico after a border incident. Troops under the command of General Zachary Taylor

defeated Santa Anna's army in northern Mexico while other American troops took possession of New Mexico and California. Mexico continued to resist despite a chaotic political situation, and so Polk launched an invasion of the country's heartland. An army led by Winfield Scott

occupied the port of Veracruz, and pressed inland amid bloody fighting. Santa Anna offered to cede Texas and California north of Monterrey Bay, but negotiations broke down and the fighting resumed. In September 1847, Scott's army captured Mexico City. Santa Anna was forced to flee and a provisional government began the task of negotiating peace. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

was signed on February 2, 1848. It recognized the Rio Grande

as the southern boundary of Texas

and ceded what is now the states of California, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico to the United States, while also paying Mexico $15,000,000 for the territory. The war was opposed by Whigs in the US (including Congressman Abraham Lincoln

) who considered it a European-style war of conquest and imperialism. In the presidential election of 1848, Zachary Taylor ran as a Whig and won easily when the Democrats became split, even though he was an apolitical military man who never voted in his life.

With Texas and Florida having been admitted to the union as slave states in 1845, California was made a free state in 1850.

Major events in the western movement of the U.S. population were the Homestead Act

, a law by which, for a nominal price, a settler was given title to 160 acres (65 ha) of land to farm; the opening of the Oregon Territory

to settlement; the Texas Revolution

; the opening of the Oregon Trail

; the Mormon Emigration to Utah

in 1846–47; the California Gold Rush

of 1849; the Colorado Gold Rush

of 1859; and the completion of the nation's First Transcontinental Railroad

on May 10, 1869.

George Washington

George Washington was the dominant military and political leader of the new United States of America from 1775 to 1799. He led the American victory over Great Britain in the American Revolutionary War as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army from 1775 to 1783, and presided over the writing of...

as the first president

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

in 1789, the new government acted quickly to rebuild the nation's financial structure. Enacting the program of Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton was a Founding Father, soldier, economist, political philosopher, one of America's first constitutional lawyers and the first United States Secretary of the Treasury...

, the government assumed the Revolutionary war debts of the state and the national government, and refinanced them with new federal bonds. It paid for the program through new tariffs and taxes, especially the controversial Whiskey Tax

Whiskey Rebellion

The Whiskey Rebellion, or Whiskey Insurrection, was a tax protest in the United States in the 1790s, during the presidency of George Washington. Farmers who sold their corn in the form of whiskey had to pay a new tax which they strongly resented...

. Congress adopted and sent to the states a Bill of Rights

Bill of rights

A bill of rights is a list of the most important rights of the citizens of a country. The purpose of these bills is to protect those rights against infringement. The term "bill of rights" originates from England, where it referred to the Bill of Rights 1689. Bills of rights may be entrenched or...

as 10 amendments to the new constitution; these amendments, written by Madison, are the U.S. Bill of Rights

United States Bill of Rights

The Bill of Rights is the collective name for the first ten amendments to the United States Constitution. These limitations serve to protect the natural rights of liberty and property. They guarantee a number of personal freedoms, limit the government's power in judicial and other proceedings, and...

. President Washington set up a cabinet form of government, with departments of State, Treasury, and War, along with an Attorney General (the Justice Department was created in 1870). The Judiciary Act of 1789

Judiciary Act of 1789

The United States Judiciary Act of 1789 was a landmark statute adopted on September 24, 1789 in the first session of the First United States Congress establishing the U.S. federal judiciary...

established the entire federal judiciary

United States federal courts

The United States federal courts make up the judiciary branch of federal government of the United States organized under the United States Constitution and laws of the federal government.-Categories:...

, including the Supreme Court

Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest court in the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all state and federal courts, and original jurisdiction over a small range of cases...

. The Court became important under the leadership of Chief Justice John Marshall

John Marshall

John Marshall was the Chief Justice of the United States whose court opinions helped lay the basis for American constitutional law and made the Supreme Court of the United States a coequal branch of government along with the legislative and executive branches...

(1801–1834), Federalist and nationalist who built a strong Supreme Court and strengthened the national government.

The 1790s were highly contentious, as the First Party System

First Party System

The First Party System is a model of American politics used by political scientists and historians to periodize the political party system existing in the United States between roughly 1792 and 1824. It featured two national parties competing for control of the presidency, Congress, and the states:...

emerged in the contest between Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton was a Founding Father, soldier, economist, political philosopher, one of America's first constitutional lawyers and the first United States Secretary of the Treasury...

and his Federalist party, and Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson was the principal author of the United States Declaration of Independence and the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom , the third President of the United States and founder of the University of Virginia...

and his Republican party. Washington and Hamilton were building a strong national government, with a broad financial base, and the support of merchants and financiers throughout the country. Jeffersonians opposed the new national Bank, the Navy, and federal taxes. The Federalists favored Britain, which was embattled in a series of wars with France. Jefferson's victory in 1800 opened the era of Jeffersonian democracy

Jeffersonian democracy

Jeffersonian Democracy, so named after its leading advocate Thomas Jefferson, is a term used to describe one of two dominant political outlooks and movements in the United States from the 1790s to the 1820s. The term was commonly used to refer to the Democratic-Republican Party which Jefferson...

, and doomed the upper-crust Federalists to increasingly marginal roles.

The Louisiana Purchase

Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase was the acquisition by the United States of America of of France's claim to the territory of Louisiana in 1803. The U.S...

, in 1803 opened vast Western

Western United States

.The Western United States, commonly referred to as the American West or simply "the West," traditionally refers to the region comprising the westernmost states of the United States. Because the U.S. expanded westward after its founding, the meaning of the West has evolved over time...

expanses of fertile land, that exactly met the needs of the rapidly expanding population of yeomen farmers

Plain Folk of the Old South

The Plain Folk of the Old South refers to the middling class of white farmers in the Southern United States before the Civil War, located between the rich planters and the poor whites. At the time they were often called "yeomen". They owned land and had no slaves or only a few. Most of them were...

whom Jefferson championed.

The Americans declared war on Britain (the War of 1812

War of 1812

The War of 1812 was a military conflict fought between the forces of the United States of America and those of the British Empire. The Americans declared war in 1812 for several reasons, including trade restrictions because of Britain's ongoing war with France, impressment of American merchant...

) to uphold American honor at sea, and to end the Indian raids in the west. Despite incompetent government management, and a series of defeats early on, Americans found new generals like Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson was the seventh President of the United States . Based in frontier Tennessee, Jackson was a politician and army general who defeated the Creek Indians at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend , and the British at the Battle of New Orleans...

, William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison was the ninth President of the United States , an American military officer and politician, and the first president to die in office. He was 68 years, 23 days old when elected, the oldest president elected until Ronald Reagan in 1980, and last President to be born before the...

, and Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott was a United States Army general, and unsuccessful presidential candidate of the Whig Party in 1852....

, who repulsed British invasions and broke the alliance between the British and the Indians that held up settlement of the Old Northwest. The Federalists, who had opposed the war to the point of trading with the enemy and threatening secession, were devastated by the triumphant ending of the war. The remaining Indians east of the Mississippi were kept on reservations or moved via the Trail of Tears

Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears is a name given to the forced relocation and movement of Native American nations from southeastern parts of the United States following the Indian Removal Act of 1830...

to reservations in what later became Oklahoma.

The spread of democracy opened the ballot box to nearly all white men, allowing the Jacksonian democracy

Jacksonian democracy

Jacksonian democracy is the political movement toward greater democracy for the common man typified by American politician Andrew Jackson and his supporters. Jackson's policies followed the era of Jeffersonian democracy which dominated the previous political era. The Democratic-Republican Party of...

to dominate politics during the Second Party System

Second Party System

The Second Party System is a term of periodization used by historians and political scientists to name the political party system existing in the United States from about 1828 to 1854...

. Whigs, representing wealthier planters, merchants, financiers and professionals, wanted to modernize the society, using tariffs and federally funded internal improvements

Internal improvements

Internal improvements is the term used historically in the United States for public works from the end of the American Revolution through much of the 19th century, mainly for the creation of a transportation infrastructure: roads, turnpikes, canals, harbors and navigation improvements...

; they were blocked by the Jacksonians, who closed down the national Bank in the 1830s. The Jacksonians wanted expansion—that is "Manifest Destiny

Manifest Destiny

Manifest Destiny was the 19th century American belief that the United States was destined to expand across the continent. It was used by Democrat-Republicans in the 1840s to justify the war with Mexico; the concept was denounced by Whigs, and fell into disuse after the mid-19th century.Advocates of...

"—into new lands that would be occupied by farmers and planters. Thanks to the annexation of Texas, the defeat of Mexico in war, and a compromise with Britain, the western third of the nation rounded out the continental United States by 1848.

Howe (2007) argues that the transformation America underwent was not so much political democratization but rather the explosive growth of technologies and networks of infrastructure and communication—the telegraph, railroads, the post office, and an expanding print industry. They made possible the religious revivals of the Second Great Awakening

Second Great Awakening

The Second Great Awakening was a Christian revival movement during the early 19th century in the United States. The movement began around 1800, had begun to gain momentum by 1820, and was in decline by 1870. The Second Great Awakening expressed Arminian theology, by which every person could be...

, the expansion of education and social reform. They modernized party politics, as speeded up business by enabling the fast, efficient movement of goods, money and people across an expanding nation. They transformed a loose-knit collection of parochial agricultural communities into a powerful cosmopolitan nation Economic modernization proceeded rapidly, thanks to highly profitable cotton crops in the South, new textile and machine-making industries in the Northeast, and a fast developing transportation infrastructure.

Breaking loose from European models, the Americans developed their own high culture, notably in literature and in higher education. The Second Great Awakening

Second Great Awakening

The Second Great Awakening was a Christian revival movement during the early 19th century in the United States. The movement began around 1800, had begun to gain momentum by 1820, and was in decline by 1870. The Second Great Awakening expressed Arminian theology, by which every person could be...

brought revivals across the country, forming new denominations and greatly increasing church membership, especially among Methodists and Baptists. By the 1840s increasing numbers of immigrants were arriving from Europe, especially British, Irish, and Germans. Many settled in the cities, which were starting to emerge as a major factor in the economy and society.

The Whigs had warned that annexation of Texas would lead to a crisis over slavery, and they were proven right by the turmoil of the 1850s that led to civil war.

Washington Administration: 1789–1797

.jpg)

George Washington, a renowned hero of the American Revolutionary War

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War , the American War of Independence, or simply the Revolutionary War, began as a war between the Kingdom of Great Britain and thirteen British colonies in North America, and ended in a global war between several European great powers.The war was the result of the...

, commander of the Continental Army

Continental Army

The Continental Army was formed after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War by the colonies that became the United States of America. Established by a resolution of the Continental Congress on June 14, 1775, it was created to coordinate the military efforts of the Thirteen Colonies in...

, and president of the Constitutional Convention

Philadelphia Convention

The Constitutional Convention took place from May 14 to September 17, 1787, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to address problems in governing the United States of America, which had been operating under the Articles of Confederation following independence from...

, was unanimously chosen as the first President of the United States

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

under the new U.S. Constitution. All the leaders of the new nation were committed to republicanism

Republicanism in the United States

Republicanism is the political value system that has been a major part of American civic thought since the American Revolution. It stresses liberty and inalienable rights as central values, makes the people as a whole sovereign, supports activist government to promote the common good, rejects...

, and the doubts of the Anti-Federalists of 1788 were allayed with the passage of a Bill of Rights

United States Bill of Rights

The Bill of Rights is the collective name for the first ten amendments to the United States Constitution. These limitations serve to protect the natural rights of liberty and property. They guarantee a number of personal freedoms, limit the government's power in judicial and other proceedings, and...

as the first 10 amendments to the Constitution in 1791.

The first census, conducted by Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson was the principal author of the United States Declaration of Independence and the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom , the third President of the United States and founder of the University of Virginia...

, enumerated a population of 3.9 million, with a density of 4.5 people per square mile of land area. There were only 12 cities of more than 5,000 population, as the great majority of the people were farmers.

Congress passed the Judiciary Act of 1789

Judiciary Act of 1789

The United States Judiciary Act of 1789 was a landmark statute adopted on September 24, 1789 in the first session of the First United States Congress establishing the U.S. federal judiciary...

, which established the entire federal judiciary

United States federal courts

The United States federal courts make up the judiciary branch of federal government of the United States organized under the United States Constitution and laws of the federal government.-Categories:...

. At the time, the act provided for a Supreme Court of six justices, three circuit courts

United States circuit court

The United States circuit courts were the original intermediate level courts of the United States federal court system. They were established by the Judiciary Act of 1789. They had trial court jurisdiction over civil suits of diversity jurisdiction and major federal crimes. They also had appellate...

, and 13 district courts

United States district court

The United States district courts are the general trial courts of the United States federal court system. Both civil and criminal cases are filed in the district court, which is a court of law, equity, and admiralty. There is a United States bankruptcy court associated with each United States...

. It also created the offices of U.S. Marshal

United States Marshals Service

The United States Marshals Service is a United States federal law enforcement agency within the United States Department of Justice . The office of U.S. Marshal is the oldest federal law enforcement office in the United States; it was created by the Judiciary Act of 1789...

, Deputy Marshal, and District Attorney

United States Attorney

United States Attorneys represent the United States federal government in United States district court and United States court of appeals. There are 93 U.S. Attorneys stationed throughout the United States, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands...

in each federal judicial district

United States federal judicial district

For purposes of the federal judicial system, Congress has divided the United States into judicial districts. There are 94 federal judicial districts, including at least one district in each state, the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico...

. The Compromise of 1790

Compromise of 1790

The Compromise of 1790 was the first of three great political compromises made in the United States by the Northern and Southern states, occurring every thirty years, in an attempt to keep the Union together and prevent civil war...

located to the national capital in the southern state of Maryland (now the District of Columbia), and enabled the federal assumption of state debts.

Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton was a Founding Father, soldier, economist, political philosopher, one of America's first constitutional lawyers and the first United States Secretary of the Treasury...

, with Washington's support and Jefferson's opposition, convinced Congress to pass a far-reaching financial program that funded the debts of the American Revolution, set up a national bank, and set up a system of tariffs and taxes to pay for all. His policies had the effect of linking the economic interests of the states, and of wealthy Americans, to the success of the national government, as well as enhancing the international financial standing of the new nation.

The Whiskey Rebellion

Whiskey Rebellion

The Whiskey Rebellion, or Whiskey Insurrection, was a tax protest in the United States in the 1790s, during the presidency of George Washington. Farmers who sold their corn in the form of whiskey had to pay a new tax which they strongly resented...

in 1794—when settlers in the Monongahela Valley of western Pennsylvania protested against the new federal tax on whiskey, which the settlers shipped across the mountains to earn money. It was the first serious test of the federal government. Washington ordered federal marshals to serve court orders requiring the tax protesters to appear in federal district court. By August 1794, the protests became dangerously close to outright rebellion, and on August 7, several thousand armed settlers gathered near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Pittsburgh is the second-largest city in the US Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and the county seat of Allegheny County. Regionally, it anchors the largest urban area of Appalachia and the Ohio River Valley, and nationally, it is the 22nd-largest urban area in the United States...

. Washington then invoked the Militia Law of 1792 to summon the militias of several states. A force of 13,000 men was organized, and Washington personally led it to Western Pennsylvania

Western Pennsylvania

Western Pennsylvania consists of the western third of the state of Pennsylvania in the United States. Pittsburgh is the largest city in the region, with a metropolitan area population of about 2.4 million people, and serves as its economic and cultural center. Erie, Altoona, and Johnstown are its...

. The revolt immediately collapsed, and there was no violence.

Foreign policy unexpectedly took center stage starting in 1793, when revolutionary France and conservative Britain went to war, opening a period of intense European conflict that lasted until 1815. The American policy was, "remain neutral", but the Jeffersonians strongly favored France, and deeply distrusted the British, who they saw as enemies of Republicanism. Hamilton and the business community favored Britain, which was by far America's largest trading partner. The tensions with Britain were resolved with the Jay Treaty of 1794, which opened up 10 years of prosperous trade, and forced the British to withdraw from their forts in the American Far West. The Jeffersonians tried to defeat the treaty, but failed when Washington threw his prestige into the conflict.

Continuing conflict between Hamilton and Jefferson, especially over foreign policy, led to the formation of the Federalist and Republican parties. Although Washington warned against political parties in his farewell address

George Washington's Farewell Address

George Washington's Farewell Address was written to "The People of the United States" near the end of his second term as President of the United States and before his retirement to his home at Mount Vernon....

, he generally supported Hamilton and Hamiltonian programs over those of Jefferson. After his death in 1799 he became the great symbolic hero of the Federalists.

Emergence of political parties

The First Party System between 1792 and 1824 featured two national parties competing for control of the presidency, Congress, and the states: the Federalist PartyFederalist Party (United States)

The Federalist Party was the first American political party, from the early 1790s to 1816, the era of the First Party System, with remnants lasting into the 1820s. The Federalists controlled the federal government until 1801...

was created by Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton was a Founding Father, soldier, economist, political philosopher, one of America's first constitutional lawyers and the first United States Secretary of the Treasury...

and was dominant to 1800. The rival Republican Party

Democratic-Republican Party (United States)

The Democratic-Republican Party or Republican Party was an American political party founded in the early 1790s by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. Political scientists use the former name, while historians prefer the latter one; contemporaries generally called the party the "Republicans", along...

(Democratic-Republican Party) was created by Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson was the principal author of the United States Declaration of Independence and the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom , the third President of the United States and founder of the University of Virginia...

and James Madison

James Madison

James Madison, Jr. was an American statesman and political theorist. He was the fourth President of the United States and is hailed as the “Father of the Constitution” for being the primary author of the United States Constitution and at first an opponent of, and then a key author of the United...