Treaty of New Echota

Encyclopedia

Treaty

A treaty is an express agreement under international law entered into by actors in international law, namely sovereign states and international organizations. A treaty may also be known as an agreement, protocol, covenant, convention or exchange of letters, among other terms...

signed on December 29, 1835, in New Echota

New Echota

New Echota was the capital of the Cherokee Nation prior to their forced removal in the 1830s. New Echota is 3.68 miles north of present-day Calhoun, Georgia, and south of Resaca, Georgia. The site is a state park and an historic site....

, Georgia

Georgia (U.S. state)

Georgia is a state located in the southeastern United States. It was established in 1732, the last of the original Thirteen Colonies. The state is named after King George II of Great Britain. Georgia was the fourth state to ratify the United States Constitution, on January 2, 1788...

by officials of the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

government and representatives of a minority Cherokee

Cherokee

The Cherokee are a Native American people historically settled in the Southeastern United States . Linguistically, they are part of the Iroquoian language family...

political faction, known as the Treaty Party. The treaty was amended and ratified by the US Senate in March 1836, despite protests from the Cherokee National Council and its lacking the signature of the Principal Chief John Ross

John Ross (Cherokee chief)

John Ross , also known as Guwisguwi , was Principal Chief of the Cherokee Native American Nation from 1828–1866...

.

The treaty established terms under which the entire Cherokee Nation was expected to cede its territory in the Southeast and move west

Indian Removal

Indian removal was a nineteenth century policy of the government of the United States to relocate Native American tribes living east of the Mississippi River to lands west of the river...

to the Indian Territory

Indian Territory

The Indian Territory, also known as the Indian Territories and the Indian Country, was land set aside within the United States for the settlement of American Indians...

. Although the treaty was not approved by the Cherokee National Council, it was ratified by the U.S. Senate and became the legal basis for the forcible removal known as the Trail of Tears.

Early discussions

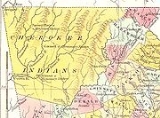

By the late 1820s, the territory of the Cherokee nation lay almost entirely in northwestern Georgia, with small parts in TennesseeTennessee

Tennessee is a U.S. state located in the Southeastern United States. It has a population of 6,346,105, making it the nation's 17th-largest state by population, and covers , making it the 36th-largest by total land area...

, Alabama

Alabama

Alabama is a state located in the southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Tennessee to the north, Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gulf of Mexico to the south, and Mississippi to the west. Alabama ranks 30th in total land area and ranks second in the size of its inland...

and North Carolina

North Carolina

North Carolina is a state located in the southeastern United States. The state borders South Carolina and Georgia to the south, Tennessee to the west and Virginia to the north. North Carolina contains 100 counties. Its capital is Raleigh, and its largest city is Charlotte...

. It extended across most of the northern border and all of the border with Tennessee. An estimated 16,000 Cherokee people lived in this territory. Others had emigrated west to present-day Texas

Texas

Texas is the second largest U.S. state by both area and population, and the largest state by area in the contiguous United States.The name, based on the Caddo word "Tejas" meaning "friends" or "allies", was applied by the Spanish to the Caddo themselves and to the region of their settlement in...

and Arkansas

Arkansas

Arkansas is a state located in the southern region of the United States. Its name is an Algonquian name of the Quapaw Indians. Arkansas shares borders with six states , and its eastern border is largely defined by the Mississippi River...

. In 1826, the Georgia legislature asked the John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams was the sixth President of the United States . He served as an American diplomat, Senator, and Congressional representative. He was a member of the Federalist, Democratic-Republican, National Republican, and later Anti-Masonic and Whig parties. Adams was the son of former...

administration to negotiate a removal treaty.

Adams, a supporter of Indian sovereignty

Sovereignty

Sovereignty is the quality of having supreme, independent authority over a geographic area, such as a territory. It can be found in a power to rule and make law that rests on a political fact for which no purely legal explanation can be provided...

, initially refused, but when Georgia threatened to nullify

Nullification (U.S. Constitution)

Nullification is a legal theory that a State has the right to nullify, or invalidate, any federal law which that state has deemed unconstitutional...

the current treaty, he approached the Cherokee to negotiate. A year passed without any progress toward removal. Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson was the seventh President of the United States . Based in frontier Tennessee, Jackson was a politician and army general who defeated the Creek Indians at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend , and the British at the Battle of New Orleans...

, a Democrat

Democratic Party (United States)

The Democratic Party is one of two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Republican Party. The party's socially liberal and progressive platform is largely considered center-left in the U.S. political spectrum. The party has the lengthiest record of continuous...

and supporter of Indian removal, was elected president in 1828

United States presidential election, 1828

The United States presidential election of 1828 featured a rematch between John Quincy Adams, now incumbent President, and Andrew Jackson, the runner-up in the 1824 election. With no other major candidates, Jackson and his chief ally Martin Van Buren consolidated their bases in the South and New...

.

Georgia laws over Cherokee territory

Shortly after the 1828 election, Georgia acted on its nullification threat. The legislature passed a series of laws abolishing the independent government of the Cherokee and extending state law over their territory. Cherokee officials were forbidden to meet for legislative purposes. White people (including missionaries and those married to Cherokee) were forbidden to live in Cherokee country without a state permit, and Cherokee were forbidden to testify in court cases involving European Americans.Soon after his inauguration, Jackson wrote an open letter

Open letter

An open letter is a letter that is intended to be read by a wide audience, or a letter intended for an individual, but that is nonetheless widely distributed intentionally....

to the Southeastern Indian nations urging them to move west. After gold

Gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au and an atomic number of 79. Gold is a dense, soft, shiny, malleable and ductile metal. Pure gold has a bright yellow color and luster traditionally considered attractive, which it maintains without oxidizing in air or water. Chemically, gold is a...

was discovered in Georgia in late 1829, the ensuing gold rush

Gold rush

A gold rush is a period of feverish migration of workers to an area that has had a dramatic discovery of gold. Major gold rushes took place in the 19th century in Australia, Brazil, Canada, South Africa, and the United States, while smaller gold rushes took place elsewhere.In the 19th and early...

increased European-American residents' determination to see the Cherokee removed. The Cherokee were forbidden to dig for gold, and Georgia authorized a survey of their lands to prepare for a lottery to distribute the land to European Americans. The state held the lottery in 1832.

In the following session, the state legislature stripped the Cherokee of all land other than their residences and adjoining improvements. By 1834 this exception was also removed. When state judges intervened on behalf of Cherokee residents, they were harassed and denied jurisdiction

Jurisdiction

Jurisdiction is the practical authority granted to a formally constituted legal body or to a political leader to deal with and make pronouncements on legal matters and, by implication, to administer justice within a defined area of responsibility...

over such cases.

Cherokee reaction

The new laws targeted the Cherokee leadership in particular. While many were of mixed ancestry, the chiefs were born into the important clans of the matrilineal culture. They gained their status from their Cherokee mothers and their clans. The Principal Chief John RossJohn Ross (Cherokee chief)

John Ross , also known as Guwisguwi , was Principal Chief of the Cherokee Native American Nation from 1828–1866...

was of mixed race, and had tried to use his heritage to benefit the Cherokee in relations with whites. Since the Georgia laws made it illegal for the Cherokee to conduct national business, the National Council (the legislative body of the Cherokee Nation) cancelled the 1832 elections. It declared that current officials would retain their offices until elections could be held, and established an emergency government based in Tennessee.

The Council tried to force Jackson's hand against Georgia by suing the state in federal courts and lobbying

Lobbying

Lobbying is the act of attempting to influence decisions made by officials in the government, most often legislators or members of regulatory agencies. Lobbying is done by various people or groups, from private-sector individuals or corporations, fellow legislators or government officials, or...

members of Congress to support Cherokee sovereignty. The United States Supreme Court struck down Georgia's laws as unconstitutional in its 1832 rulings in Worcester v. Georgia

Worcester v. Georgia

Worcester v. Georgia, 31 U.S. 515 , was a case in which the United States Supreme Court vacated the conviction of Samuel Worcester and held that the Georgia criminal statute that prohibited non-Indians from being present on Indian lands without a license from the state was unconstitutional.The...

, ruling that only the federal government had the right to deal with the Native American tribes, and the states had no right to pass legislation regulating their activities. The state ignored the ruling and continued to enforce the laws.

Jackson's initial proposal

Shortly after the Supreme Court's ruling, Jackson met with John RidgeJohn Ridge

John Ridge, born Skah-tle-loh-skee , was from a prominent family of the Cherokee Nation, then located in present-day Georgia. He married Sarah Bird Northup, of a New England family, whom he had met while studying at the Foreign Mission School in Cornwall, Connecticut...

, clerk of the Cherokee National Council, who headed a Cherokee delegation that went to Washington, DC to meet with him. When asked whether he would use federal force against Georgia, Jackson said he would not and urged Ridge to persuade the Cherokee to accept removal. Ridge, until then a supporter of the National Council's position, left the White House in despair. John McLean

John McLean

John McLean was an American jurist and politician who served in the United States Congress, as U.S. Postmaster General, and as a justice on the Ohio and U.S...

, a Jackson appointee to the Supreme Court, likewise urged the Cherokee representatives in Washington to negotiate.

Jackson quickly dispatched the Secretary of War

United States Secretary of War

The Secretary of War was a member of the United States President's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War," was appointed to serve the Congress of the Confederation under the Articles of Confederation...

Lewis Cass

Lewis Cass

Lewis Cass was an American military officer and politician. During his long political career, Cass served as a governor of the Michigan Territory, an American ambassador, a U.S. Senator representing Michigan, and co-founder as well as first Masonic Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Michigan...

to present his terms, which included western land titles, self-government, relocation assistance, and several other long-term benefits—all conditioned on a total Cherokee removal. He would allow a small number of Cherokee to stay if they accepted state authority over them.

In the following months, Ridge found supporters for the removal option, including his father Major Ridge

Major Ridge

Major Ridge, The Ridge was a Cherokee Indian member of the tribal council, a lawmaker, and a leader. He was a veteran of the Chickamauga Wars, the Creek War, and the First Seminole War.Along with Charles R...

and the major's nephews Elias Boudinot

Elias Boudinot (Cherokee)

Elias Boudinot , was a member of an important Cherokee family in present-day Georgia. They believed that rapid acculturation was critical to Cherokee survival. In 1828 Boudinot became the editor of the Cherokee Phoenix, which was published in Cherokee and English...

and Stand Watie

Stand Watie

Stand Watie , also known as Standhope Uwatie, Degataga , meaning “stand firm”), and Isaac S. Watie, was a leader of the Cherokee Nation and a brigadier general of the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War...

. In October 1832, he urged the National Council to consider Cass's proposal, but the Council was unmoved.

Divisions among the Cherokee

While Ross's delegation continued to lobby Congress for relief, the worsening situation in Georgia drove members of the Treaty Party to Washington to press for a removal treaty. Boudinot and the Ridges had come to believe that removal was inevitable, and hoped to secure Cherokee rights by agreeing to a treaty. In December 1833, several Cherokee supporting removal formed a band, with the former principal chief William HicksWilliam Hicks (Cherokee chief)

William Abraham Hicks became Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation in 1827 after being elected to succeed his older brother, Charles R. Hicks, the longtime Second Principal Chief who died on 20 January 1827, just two weeks after assuming office as Principal Chief...

as their chief and John McIntosh as his assistant. They sent a delegation led by Andrew Ross, brother of John Ross, the Principal Chief, to negotiate. The administration refused to deal with them, but invited them to return with leaders more involved in the Cherokee Nation's affairs. They returned with Boudinot and Major Ridge, and entered negotiations with Cass.

When Cass urged John Ross to join the negotiations, he denounced his brother's delegation. Andrew Ross and other members signed a harsh treaty in June 1834 without the Ridge family's support,

The progress of separate negotiations finally moved John Ross to discuss terms. He made offers to cede all land except the borders of Georgia, and then to cede all land, on the condition that the Cherokee could remain in the east subject to state laws. Cass refused, saying that he would discuss only removal. Andrew Ross's treaty was submitted to the Senate

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

, where it was rejected as not having the support of the full Nation. In the October General Council (comprising all citizens of the Nation able to attend) meeting, a federal representative presented this treaty for consideration. John Ross condemned the treaty. The Ridges and the Waties left the Council, and they and other treaty advocates began holding their own council meetings.

Division of the Cherokee Nation East

A division developed between Ross supporters (the "National Party") advocating resistance, and the Ridge supporters (the "Treaty Party"), who advocated negotiation to secure the best terms possible for the removal and protection of Cherokee rights after removal. They considered it inevitable. The Treaty Party included John Ridge, Major Ridge, Elias Boudinot, David Watie, Stand Watie, Willam Coody (Ross' nephew), William Hicks (Ross' cousin), Andrew Ross (John's younger brother), John Walker Jr., John Fields, John Gunter, David VannDavid Vann (Cherokee leader)

David Vann was a sub-Chief who was elected Treasurer of the Cherokee Nation in 1839, 1843, 1847 and 1851....

, Charles Vann, Alexander McCoy, W.A. Davis, James A. Bell, Samuel Bell, John West, Ezekiel West, Archilla Smith, and James Starr.

Eventually tensions grew to the point that several Treaty advocates, most notably John Walker Jr., were assassinated. In July 1835, hundreds of Cherokee, not from just the Treaty Party but also from the National Party (including John Ross), converged on John Ridge’s plantation named Running Waters (near Calhoun, Georgia

Calhoun, Georgia

Calhoun is a city in Gordon County, Georgia, United States. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 15,650. The city is the county seat of Gordon County.-Geography:Calhoun is located at , along the Oostanaula River....

) to meet with John F. Schermerhorn (President Jackson's envoy on the matter of a removal treaty with the Cherokee Nation East), Return J. Meigs, Jr. (Commissioner for Indian Affairs), and other officials representing the United States government.

The General Council in October 1835 rejected the proposed treaty but appointed a committee to go to Washington City to negotiate a removal treaty, a committee including not only John Ross but treaty advocates John Ridge, Charles Vann, and Elias Boudinot (who was later replaced by Stand Watie), to represent the Cherokee Nation East for a removal treaty with the stipulation that it has to be for more than five million dollars. Schermerhorn, who was present at the meeting, pushed a meeting which he wanted held at New Echota. The National Council approved a delegation to meet there. Both delegations were specifically charged with negotiating a treaty for removal.

New Echota meeting and final treaty

Over 400 men converged on the Cherokee capital in December 1835, almost exclusively from the Upper and Lower Towns (heavy snow in the western North Carolina mountains made it nearly impossible for those from the Hill and Valley Towns to travel). After a week of negotiations, Schermerhorn agreed for the United States to pay the Cherokee people $5 million dollars to be disbursed on a per capita basis, an additional $500,000 dollars is given for educational funds, title in perpetuity to an equal amount of land in Indian TerritoryIndian Territory

The Indian Territory, also known as the Indian Territories and the Indian Country, was land set aside within the United States for the settlement of American Indians...

to that given up, and full compensation for all property left in exchange for all Cherokee land east of the Mississippi River

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the largest river system in North America. Flowing entirely in the United States, this river rises in western Minnesota and meanders slowly southwards for to the Mississippi River Delta at the Gulf of Mexico. With its many tributaries, the Mississippi's watershed drains...

.(By contrast, the entire Louisiana Territory

Louisiana Territory

The Territory of Louisiana or Louisiana Territory was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 4, 1805 until June 4, 1812, when it was renamed to Missouri Territory...

was purchased from Napoleon I of France

Napoleon I of France

Napoleon Bonaparte was a French military and political leader during the latter stages of the French Revolution.As Napoleon I, he was Emperor of the French from 1804 to 1815...

for just over $23,000,000.) The treaty included a clause to allow all Cherokee who so desired to remain and become citizens of the states in which they resided, on individual allotments of 160 acre (0.6474976 km²) of land, but that was stricken out by President Jackson.

The committee reported the results to the full council gathered at New Echota, which approved the treaty unanimously. In a lengthy preamble, the Ridge party laid out its claims to legitimacy, based on its willingness to negotiate in good faith the sort of removal terms for which Ross had expressed support. The treaty was signed by Major Ridge, Elias Boudinot, James Foster, Testaesky, Charles Moore, George Chambers, Tahyeske, Archilla Smith, Andrew Ross, William Lassley, Caetehee, Tegaheske, Robert Rogers, John Gunter, John A. Bell, Charles Foreman, William Rogers, George W. Adair, James Starr

Tom Starr

Thomas Starr was a Cherokee in the American West, who was declared an outlaw by his tribe in an internal conflict over treaties with the United States government. He was also involved in running whiskey into Indian Territory and rustling stock...

, and Jesse Halfbreed. After Shermerhorn returned to Washington with the signed treaty, John Ridge and Stand Watie added their names.

Ratification

After news of the treaty became public, the officials of the Cherokee Nation from the National Party objected that they had not approved it and that the document was invalid. John RossJohn Ross (Cherokee chief)

John Ross , also known as Guwisguwi , was Principal Chief of the Cherokee Native American Nation from 1828–1866...

and the Cherokee National Council begged the Senate not to ratify the treaty (failure to ratify would thereby invalidate it). The Senate passed the measure in May 1836 by a single vote. Ross drew up a petition asking Congress to void the treaty—a petition which he personally delivered to Congress in the spring of 1838 with almost 16,000 signatures attached. This was nearly as many persons as the Cherokee Nation East had within its territory, according to the 1835 Henderson Roll, including women and children, who had no vote.

Enforcement

Ross's petition was ignored by President Martin Van BurenMartin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren was the eighth President of the United States . Before his presidency, he was the eighth Vice President and the tenth Secretary of State, under Andrew Jackson ....

, who soon directed General Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott was a United States Army general, and unsuccessful presidential candidate of the Whig Party in 1852....

to forcibly move all those Cherokee who had not yet complied with the treaty and moved west. The Cherokee people were almost entirely removed west of the Mississippi (except for the Oconaluftee Cherokee in North Carolina, the Nantahala Cherokee who joined them, and two or three hundred married to whites).

That summer (1839) a council to effect a union between the Old Settlers and the Late Immigrants convened at Double Springs in Indian Territory. It broke up sixteen days later without having reached an agreement when John Brown, Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation West, became frustrated with Ross's intransigence. The latter insisted that the Old Settlers accept him as Principal Chief over the united Nation without an election and recognize his absolute authority.

Ross’ partisans blamed Brown’s actions on the members of the Treaty Party, particularly those, such as the Ridge and Watie families, who had emigrated prior to the forced removal. They had settled with the Old Settlers. A group of these men targeted members of the Ridge faction for assassination, to enforce the Cherokee law (written by Major Ridge) making it a capital crime for any Cherokee to cede national land for private profit. There is no evidence that John Ross supported or knew of their plans.

The list of targets included Major Ridge, John Ridge, Elias Boudinot, Stand Watie, John A. Bell, James Starr, George Adair, and others (notably absent from the list were Treaty Party leaders David Vann, Charles Vann, John Gunter, Charles Foreman, William Hicks, and Andrew Ross). On 22 June 1839, teams ranging up to twenty-five in number converged on the houses of John Ridge, Major Ridge, and Elias Boudinot, and murdered them; their attempt on Stand Watie was unsuccessful. They did not attack any others, but the assassinations marked the beginning of the Cherokee Civil War; it continued until after the American Civil War. James Starr was also killed during this period. The Ross partisans forced the Old Settlers to give up their established political system and accept John Ross' authority structure.

See also

- Cherokee removalCherokee removalCherokee removal, part of the Trail of Tears, refers to the forced relocation between 1836 to 1839 of the Cherokee Nation from their lands in Georgia, Texas, Tennessee, Alabama, and North Carolina to the Indian Territory in the Western United States, which resulted in the deaths of approximately...

(Trail of Tears) - Timeline of Cherokee removalTimeline of Cherokee removalThis is a timeline of events leading up to and extending away from the Treaty of New Echota from the time of first contact to the treaty of reunion after the American Civil War.-1540–1775:...