History of Oklahoma

Encyclopedia

Oklahoma

Oklahoma is a state located in the South Central region of the United States of America. With an estimated 3,751,351 residents as of the 2010 census and a land area of 68,667 square miles , Oklahoma is the 28th most populous and 20th-largest state...

and the land that the state now occupies. Areas of Oklahoma east of its panhandle

Oklahoma Panhandle

The Oklahoma Panhandle is the extreme western region of the state of Oklahoma, comprising Cimarron County, Texas County, and Beaver County. Its name comes from the similarity of shape to the handle of a cooking pan....

were acquired in the Louisiana Purchase

Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase was the acquisition by the United States of America of of France's claim to the territory of Louisiana in 1803. The U.S...

of 1803, while the Panhandle

Oklahoma Panhandle

The Oklahoma Panhandle is the extreme western region of the state of Oklahoma, comprising Cimarron County, Texas County, and Beaver County. Its name comes from the similarity of shape to the handle of a cooking pan....

was not acquired until the U.S. land acquisitions following the Mexican-American War.

There is some question as to whether or not Francisco Vásquez de Coronado

Francisco Vásquez de Coronado

Francisco Vásquez de Coronado y Luján was a Spanish conquistador, who visited New Mexico and other parts of what are now the southwestern United States between 1540 and 1542...

was the first European to set foot inside Oklahoma.

Before 1500 CE

Archaeologists believe that ancestors of the Wichita people occupied the eastern Great PlainsGreat Plains

The Great Plains are a broad expanse of flat land, much of it covered in prairie, steppe and grassland, which lies west of the Mississippi River and east of the Rocky Mountains in the United States and Canada. This area covers parts of the U.S...

from the Red River north to Nebraska

Nebraska

Nebraska is a state on the Great Plains of the Midwestern United States. The state's capital is Lincoln and its largest city is Omaha, on the Missouri River....

for at least 2,000 years. These early Wichita people were hunters and gatherers who slowly adopted agriculture. About 900 CE, on terraces above the Washita

Washita River

The Washita River is a river in Texas and Oklahoma, United States. The river is long and terminates into Lake Texoma in Johnston County , Oklahoma and the Red River.-Geography:...

and South Canadian Rivers

Canadian River

The Canadian River is the longest tributary of the Arkansas River. It is about long, starting in Colorado and traveling through New Mexico, the Texas Panhandle, and most of Oklahoma....

in Oklahoma, farming villages began to appear. The inhabitants of these villages grew corn, beans, squash, marsh elder, and tobacco. They hunted deer, rabbit, turkey, and, increasingly, bison, and caught fish and collected mussels in the rivers. These villagers lived in rectangular thatched houses. They became numerous, with villages of up to 20 houses spaced every two or so miles along the rivers.

By 1500, Apache groups had also begun moving into formerly Wichita areas of Oklahoma. However, it appears that the two people co-existed in the region for some time. In addition to Apache influence, the Wichita of southwestern Oklahoma appear to have had regular trade contact with Texas and New Mexico.

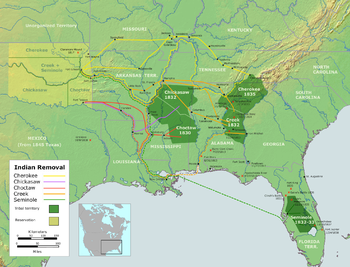

The Indian Relocation

Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma

The Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma is a semi-autonomous Native American homeland comprising twelve tribal districts. The Choctaw Nation maintains a special relationship with both the United States and Oklahoma governments...

. Later the area would be named Indian Territory

Indian Territory

The Indian Territory, also known as the Indian Territories and the Indian Country, was land set aside within the United States for the settlement of American Indians...

. The goal was to provide ample lands for the relocation of Native American

Native Americans in the United States

Native Americans in the United States are the indigenous peoples in North America within the boundaries of the present-day continental United States, parts of Alaska, and the island state of Hawaii. They are composed of numerous, distinct tribes, states, and ethnic groups, many of which survive as...

s in the eastern states who did not wish to assimilate.

The Indian Removal Act

Indian Removal Act

The Indian Removal Act was signed into law by President Andrew Jackson on May 28, 1830.The Removal Act was strongly supported in the South, where states were eager to gain access to lands inhabited by the Five Civilized Tribes. In particular, Georgia, the largest state at that time, was involved in...

of 1830 gave President Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson was the seventh President of the United States . Based in frontier Tennessee, Jackson was a politician and army general who defeated the Creek Indians at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend , and the British at the Battle of New Orleans...

the power to negotiate treaties for removal with Indian tribes living east of the Mississippi River. The treaty called for the Indians to give up their eastern land for land in the west. Those who wished to stay behind were allowed to stay, assimilate and become citizens in their state. For the tribes that agreed to Jackson's terms, the removal was peaceful; however, those who resisted were eventually forced to leave.

The Choctaw was the first of the "Five Civilized Tribes

Five Civilized Tribes

The Five Civilized Tribes were the five Native American nations—the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole—that were considered civilized by Anglo-European settlers during the colonial and early federal period because they adopted many of the colonists' customs and had generally good...

" to be removed from the southeastern United States. The phrase "Trail of Tears" originated from a description of the removal of the Choctaw

Choctaw

The Choctaw are a Native American people originally from the Southeastern United States...

Nation in 1831, although the term is usually used for the Cherokee removal. In September 1830, Choctaws in Mississippi agreed to terms of the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek

Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek

The Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek was a treaty signed on September 27, 1830 between the Choctaw and the United States Government. This was the first removal treaty carried into effect under the Indian Removal Act...

and prepared to move west.

The Creek

Creek people

The Muscogee , also known as the Creek or Creeks, are a Native American people traditionally from the southeastern United States. Mvskoke is their name in traditional spelling. The modern Muscogee live primarily in Oklahoma, Alabama, Georgia, and Florida...

also refused to relocate and signed a treaty in March 1832 to open up a large portion of their land in exchange for protection of ownership of their remaining lands. The United States failed to protect the Creeks, and in 1837, they were militarily removed without ever signing a treaty.

The Chickasaw

Chickasaw

The Chickasaw are Native American people originally from the region that would become the Southeastern United States...

saw the relocation as inevitable and signed a treaty in 1832 which included protection until their move. The Chickasaws were forced to move early as a result of white settlers and the War Department's refusal to protect the Indian's lands.

In 1833, a small group of Seminoles signed a relocation treaty. However, the treaty was declared illegitimate by a majority of the tribe. The result was the Second

Second Seminole War

The Second Seminole War, also known as the Florida War, was a conflict from 1835 to 1842 in Florida between various groups of Native Americans collectively known as Seminoles and the United States, part of a series of conflicts called the Seminole Wars...

and Third Seminole Wars. Those that survived the wars eventually were paid to move west.

The Treaty of New Echota

Treaty of New Echota

The Treaty of New Echota was a treaty signed on December 29, 1835, in New Echota, Georgia by officials of the United States government and representatives of a minority Cherokee political faction, known as the Treaty Party...

of 1833 gave the Cherokees in the state of Georgia

Georgia (U.S. state)

Georgia is a state located in the southeastern United States. It was established in 1732, the last of the original Thirteen Colonies. The state is named after King George II of Great Britain. Georgia was the fourth state to ratify the United States Constitution, on January 2, 1788...

two years to move west, or they would be forced to move. At the end of the two years only 2,000 Cherokees had migrated westward and 16,000 remained on their lands. The U.S. sent 7,000 soldiers to force the Cherokee to move without the time to gather their belongings. This march westward is known as the Trail of Tears

Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears is a name given to the forced relocation and movement of Native American nations from southeastern parts of the United States following the Indian Removal Act of 1830...

, in which 4,000 Cherokee died.

Civil War

In 1860, the Indian Territory had a population of 55,000 Indians, 8,400 black slaves owned by Indians, and 3000 whites. In 1861, as the American Civil WarAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

began, Texas forces moved north and the United States withdrew its military forces from the territory. Confederate Commissioner Albert Pike

Albert Pike

Albert Pike was an attorney, Confederate officer, writer, and Freemason. Pike is the only Confederate military officer or figure to be honored with an outdoor statue in Washington, D.C...

signed formal treaties of alliance with all the major tribes, and the territories sent a delegate to the Confederate Congress in Richmond. However, there were minority factions who opposed the Confederacy, with the result that a small-scale Civil War raged inside the territory. By summer 1863, Union forces controlled neighboring Arkansas, and Confederate hopes for retaining control of the territory collapsed. A force of Union troops and loyal Indians invaded Indian Territory and won a strategic victory at Honey Springs on July 17, 1863. Many pro-Confederate Cherokee, Creek, and Seminole Indians fled south, becoming refugees among the Chickasaw and Choctaws. However, Confederate Brigadier General Stand Watie

Stand Watie

Stand Watie , also known as Standhope Uwatie, Degataga , meaning “stand firm”), and Isaac S. Watie, was a leader of the Cherokee Nation and a brigadier general of the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War...

, a Cherokee, captured Union supplies, and kept the insurgency active. Watie was the last Confederate general to give up; he surrendered on 23 June 1865.

Post-Civil War Period

In 1866 the federal government forced the tribes into new treaties. Most of the land in central and western Indian Territory was ceded to the government. Some of the land was given to other tribes, but the central part, the so-called Unassigned Lands, remained with the government. Another concession allowed railroadRail transport

Rail transport is a means of conveyance of passengers and goods by way of wheeled vehicles running on rail tracks. In contrast to road transport, where vehicles merely run on a prepared surface, rail vehicles are also directionally guided by the tracks they run on...

s to cross Indian lands. Furthermore the practice of slavery was outlawed. Some nations were integrated racially and otherwise with their slaves, but other nations were extremely hostile to the former slaves and wanted them exiled from their territory.

In the 1870s, a movement began by whites and blacks wanting to settle the government lands in the Indian Territory under the Homestead Act

Homestead Act

A homestead act is one of three United States federal laws that gave an applicant freehold title to an area called a "homestead" – typically 160 acres of undeveloped federal land west of the Mississippi River....

of 1862. They referred to the Unassigned Lands as Oklahoma and to themselves as Boomers. In the 1880s, early settlers of the state's very sparsely populated Panhandle region

Oklahoma Panhandle

The Oklahoma Panhandle is the extreme western region of the state of Oklahoma, comprising Cimarron County, Texas County, and Beaver County. Its name comes from the similarity of shape to the handle of a cooking pan....

tried to form the Cimarron Territory but lost a lawsuit against the federal government. This prompted a judge in Paris, Texas

Paris, Texas

Paris, Texas is a city located northeast of the Dallas–Fort Worth Metroplex in Lamar County, Texas, in the United States. It is situated in Northeast Texas at the western edge of the Piney Woods. Physiographically, these regions are part of the West Gulf Coastal Plain. In 1900, 9,358 people lived...

, to unintentionally create a moniker for the area. "That is land that can be owned by no man," the judge said, and after that the panhandle was referred to as No Man's Land until statehood arrived decades later.

In 1884, in United States v. Payne, the United States District Court in Topeka, Kansas

Topeka, Kansas

Topeka |Kansa]]: Tó Pee Kuh) is the capital city of the U.S. state of Kansas and the county seat of Shawnee County. It is situated along the Kansas River in the central part of Shawnee County, located in northeast Kansas, in the Central United States. As of the 2010 census, the city population was...

, ruled that settling on the lands ceded to the government by the Indians under the 1866 treaties was not a crime. The government at first resisted, but Congress

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the bicameral legislature of the federal government of the United States, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Congress meets in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C....

soon enacted laws authorizing settlement.

Congress passed the Dawes Act

Dawes Act

The Dawes Act, adopted by Congress in 1887, authorized the President of the United States to survey Indian tribal land and divide the land into allotments for individual Indians. The Act was named for its sponsor, Senator Henry L. Dawes of Massachusetts. The Dawes Act was amended in 1891 and again...

, or General Allotment Act, in 1887 requiring the government to negotiate agreements with the tribes to divide Indian lands into individual holdings. Under the allotment system, tribal lands left over would be surveyed for settlement by non-Indians. Following settlement, many whites accused Republican officials of giving preferential treatment to ex-slaves in land disputes.

Land runs

Unassigned Lands

Unassigned Lands, or Oklahoma, were in the center of the lands ceded to the United States by the Creek and Seminole Indians following the Civil War and on which no other tribes had been settled...

or Oklahoma Country in the 1880s due to it remaining uninhabited for over a decade.

In 1879, part-Cherokee Elias C. Boudinot argued that these Unassigned Lands be open for settlement because the title to these lands belonged to the United States and "whatever may have been the desire or intention of the United States Government in 1866 to locate Indians and negroes upon these lands, it is certain that no such desire or intention exists in 1879. The Negro since that date, has become a citizen of the United States, and Congress has recently enacted laws which practically forbid the removal of any more Indians into the Territory".

On March 23, 1889, President Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison was the 23rd President of the United States . Harrison, a grandson of President William Henry Harrison, was born in North Bend, Ohio, and moved to Indianapolis, Indiana at age 21, eventually becoming a prominent politician there...

signed legislation which opened up the two million acres (8,000 km²) of the Unassigned Lands

Unassigned Lands

Unassigned Lands, or Oklahoma, were in the center of the lands ceded to the United States by the Creek and Seminole Indians following the Civil War and on which no other tribes had been settled...

for settlement on April 22, 1889. It was to be the first of many land run

Land run

Land run usually refers to an historical event in which previously restricted land of the United States was opened for homesteading on a first arrival basis. Some newly opened lands were sold first-come, sold by bid, or won by lottery, or by means other than a run...

s, but later land openings were conducted by means of a lottery because of widespread cheating—some of the settlers were called Sooners because they had already staked their land claims before the land was officially opened for settlement.

The Organic Act

Organic Act

An Organic Act, in United States law, is an Act of the United States Congress that establishes a territory of the United States or an agency to manage certain federal lands. The first such act was the Northwest Ordinance, enacted by the Congress of the Confederation in 1787 in order to create the...

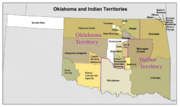

of 1890 created the Oklahoma Territory

Oklahoma Territory

The Territory of Oklahoma was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 2, 1890, until November 16, 1907, when it was joined with the Indian Territory under a new constitution and admitted to the Union as the State of Oklahoma.-Organization:Oklahoma Territory's...

out of the Unassigned Lands and the area known as No Man's Land.

In 1893, the government purchased the rights to settle the Cherokee Outlet

Cherokee Outlet

The Cherokee Outlet, often mistakenly referred to as the Cherokee Strip, was located in what is now the state of Oklahoma, in the United States. It was a sixty-mile wide strip of land south of the Oklahoma-Kansas border between the 96th and 100th meridians. It was about 225 miles long and in 1891...

, or Cherokee Strip, from the Cherokee Nation. The Cherokee Outlet was part of the lands ceded to the government in the 1866 treaty, but the Cherokees retained access to the area and had leased it to several Chicago meat-packing plants for huge cattle ranches. The Cherokee Strip was opened to settlement by land run in 1894. Also, in 1893, Congress set up the Dawes Commission

Dawes Commission

The American Dawes Commission, named for its first chairman Henry L. Dawes, was authorized under a rider to an Indian Office appropriation bill, March 3, 1893...

to negotiate agreements with each of the Five Civilized Tribes for the allotment of tribal lands to individual Indians. Finally, the Curtis Act of 1898

Curtis Act of 1898

The Curtis Act of 1898 was an amendment to the United States Dawes Act that brought about the allotment process of lands of the Five Civilized Tribes of Indian Territory: the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Muscogee, Cherokee, and Seminole...

abolished tribal jurisdiction over all of Indian Territory

Indian Territory

The Indian Territory, also known as the Indian Territories and the Indian Country, was land set aside within the United States for the settlement of American Indians...

.

Angie Debo

Angie Debo

Angie Elbertha Debo was an American historian who wrote 13 books and hundreds of articles about Native American and Oklahoma history...

's landmark work, And Still the Waters Run: The Betrayal of the Five Civilized Tribes (1940), detailed how the allotment policy of the Dawes Commission and the Curtis Act of 1898 was systematically manipulated to deprive the Native Americans of their lands and resources. In the words of historian Ellen Fitzpatrick, Debo's book "advanced a crushing analysis of the corruption, moral depravity, and criminal activity that underlay white administration and execution of the allotment policy."

Statehood

In 1902, the leaders of Indian Territory sought to become their own state, to be named Sequoyah. They held a convention in EufaulaEufaula, Oklahoma

Eufaula is a city in McIntosh County, Oklahoma, United States. The population was 2,639 at the 2000 census. It is the county seat of McIntosh County.-Geography:Eufaula is located at ....

, consisting of representatives from the Cherokee

Cherokee

The Cherokee are a Native American people historically settled in the Southeastern United States . Linguistically, they are part of the Iroquoian language family...

, Choctaw

Choctaw

The Choctaw are a Native American people originally from the Southeastern United States...

, Chickasaw

Chickasaw

The Chickasaw are Native American people originally from the region that would become the Southeastern United States...

, Muscogee (Creek), and Seminole

Seminole

The Seminole are a Native American people originally of Florida, who now reside primarily in that state and Oklahoma. The Seminole nation emerged in a process of ethnogenesis out of groups of Native Americans, most significantly Creeks from what is now Georgia and Alabama, who settled in Florida in...

tribes, known as the Five Civilized Tribes

Five Civilized Tribes

The Five Civilized Tribes were the five Native American nations—the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole—that were considered civilized by Anglo-European settlers during the colonial and early federal period because they adopted many of the colonists' customs and had generally good...

. They met again next year to establish a constitutional convention.

The Sequoyah Constitutional Convention and statehood attempt

The Sequoyah Constitutional Convention met in Muskogee, on August 21, 1905. General Pleasant Porter, Principal Chief of the Muscogee Creek Nation, was selected as president of the convention. The elected delegates decided that the executive officers of the Five Civilized Tribes would also be appointed as vice-presidents: William Charles RogersWilliam Charles Rogers

William Charles Rogers was born near Claremore, Oklahoma on the 13th of December 1847. A successful farmer, he entered local politics in 1881.A member of the Downing Party, he was elected Principal Chief in 1903, defeating E. L. Cookson of the National Party...

, Principal Chief of the Cherokees; William H. Murray

William H. Murray

William Henry Davis "Alfalfa Bill" Murray was an American teacher, lawyer, and politician who became active in Oklahoma before statehood as legal adviser to Governor Douglas H. Johnston of the Chickasaw Nation...

, appointed by Chickasaw Governor Douglas H. Johnston

Douglas H. Johnston

Douglas Hancock Cooper Johnston , also known as “Douglas Henry Johnston”, was Governor of the Chickasaw Nation from 1898 to 1902 and from 1904 to 1939.- Background :...

to represent the Chickasaws; Chief Green McCurtain

Green McCurtain

Greenwood "Green" McCurtain was Principal Chief of the Choctaw Nation and , serving four two-year terms. He was the third of his brothers to be elected as chief, and after 1906 and the dissolution of tribal governments under the Dawes Act, he was appointed as chief by the United States government...

of the Choctaws; Chief John Brown

John Brown (Seminole Chief)

John Frippo Brown, a Seminole of the Tiger Clan, was a Confederate States Army officer during the American Civil War. He was elected by the tribal council as the last principal chief of the Seminole Nation before Oklahoma statehood.-Early life and education:...

of the Seminoles; and Charles N. Haskell

Charles N. Haskell

Charles Nathaniel Haskell was an American lawyer, oilman, and statesman who served as the first Governor of Oklahoma. Haskell played a crucial role in drafting the Oklahoma Constitution as well as Oklahoma's statehood and admission into the United States as the 46th state in 1907...

, selected to represent the Creeks (as General Porter had been elected President).

The convention drafted the constitution, established an organizational plan for a government, outlined proposed county designations in the new state, and elected delegates to go to the United States Congress

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the bicameral legislature of the federal government of the United States, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Congress meets in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C....

to petition for statehood. If this had happened, the State of Sequoyah

State of Sequoyah

The State of Sequoyah was the proposed name for a state to be established in the eastern part of present-day Oklahoma. In 1905, faced by proposals to end their tribal governments, Native Americans of the Five Civilized Tribes in Indian Territory proposed such a state as a means to retain some...

would have been the first state to have a Native American majority population.

The convention's proposals were overwhelmingly endorsed by the residents of Indian Territory in a referendum election in 1905. The U.S. government, however, reacted coolly to the idea of Indian Territory and Oklahoma Territory becoming separate states; they preferred to have them share a singular state.

Murray's Proposal

Murray, known for his eccentricities and political astuteness, foresaw this possibility prior to the constitutional convention. When Johnston asked Murray to represent the Chickasaw Nation during Sequoyah's attempt at statehood, Murray predicted the plan would not succeed in Washington, D.C.Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

. He suggested that if the attempt failed, the Indian Territory would work with the Oklahoma Territory to become one state. President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore "Teddy" Roosevelt was the 26th President of the United States . He is noted for his exuberant personality, range of interests and achievements, and his leadership of the Progressive Movement, as well as his "cowboy" persona and robust masculinity...

and Congress turned down the Indian Territory proposal.

Seeing an opportunity for statehood, Murray and Haskell proposed another convention for the combined territories to be named Oklahoma. Using the constitution from the Sequoyah convention as a basis (and the majority) of the new state constitution, Haskell and Murray returned to Washington with the proposal for statehood. On November 16, 1907 President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore "Teddy" Roosevelt was the 26th President of the United States . He is noted for his exuberant personality, range of interests and achievements, and his leadership of the Progressive Movement, as well as his "cowboy" persona and robust masculinity...

signed the proclamation establishing Oklahoma as the nation's 46th state.

Oil

Petroleum

Petroleum or crude oil is a naturally occurring, flammable liquid consisting of a complex mixture of hydrocarbons of various molecular weights and other liquid organic compounds, that are found in geologic formations beneath the Earth's surface. Petroleum is recovered mostly through oil drilling...

business really began to get underway. Huge pools of underground oil were discovered in places like Glenpool

Glenpool, Oklahoma

Glenpool is a city in Tulsa County, Oklahoma, United States. It is part of the Tulsa Metropolitan Statistical Area . As of 2010, the population was 10,808. This was an increase of 33.1 % since the 2000 census, which reported total population as 8,123....

near Tulsa. Many whites flooded into the state to make money. Many of the "old money" elite families of Oklahoma can date their rise to this time.

Throughout the 1920s, new oil fields were continually discovered and Oklahoma produced over 1.8 billion barrels of petroleum, valued at over 3.5 million dollars for the decade. In 1920 the spectacular Osage County oil field was opened, followed in 1926 by the Greater Seminole Oil Field. When the Great Depression

Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe worldwide economic depression in the decade preceding World War II. The timing of the Great Depression varied across nations, but in most countries it started in about 1929 and lasted until the late 1930s or early 1940s...

Oklahoma and Texas oil was flooding the market and prices fell to pennies a gallon. In 1931 Governor William H. Murray, acting with characteristic decisiveness, used the National Guard to shut down all of Oklahoma's oil wells in an effort to stabilize prices. National policy became using the Texas Railroad Commission to set allotments in Texas, which raised prices as well for Oklahoma crude.

Prosperous 1920s

The prosperity of the 1920s can be seen in the surviving architecture from the period, such as the Tulsa mansion which was converted into the Philbrook Museum of ArtPhilbrook Museum of Art

The Philbrook Museum of Art in Tulsa, Oklahoma is an art museum and former home of Oklahoma oil pioneer Waite Phillips and his wife Genevieve Phillips. , the museum has a staff of 60 and an operating budget of nearly $6 million....

or the art deco

Art Deco

Art deco , or deco, is an eclectic artistic and design style that began in Paris in the 1920s and flourished internationally throughout the 1930s, into the World War II era. The style influenced all areas of design, including architecture and interior design, industrial design, fashion and...

architecture of downtown Tulsa.

Blacks

For Oklahoma, the early quarter of the 20th century was politically turbulent. Many different groups had flooded into the state; "black towns", or towns made of groups of African AmericanAfrican American

African Americans are citizens or residents of the United States who have at least partial ancestry from any of the native populations of Sub-Saharan Africa and are the direct descendants of enslaved Africans within the boundaries of the present United States...

s choosing to live separately from whites, sprouted all over the state, while most of the state abided by the Jim Crow laws

Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws in the United States enacted between 1876 and 1965. They mandated de jure racial segregation in all public facilities, with a supposedly "separate but equal" status for black Americans...

within each individual city, racially separating people with a bias against any non-White race. Greenwood

Greenwood, Tulsa, Oklahoma

Greenwood was a district in Tulsa, Oklahoma. As one of the most successful and wealthiest African American communities in the United States during the early 20th Century, it was popularly known as America's "Black Wall Street" until the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921...

, a neighborhood in Northern Tulsa, was known as Black Wall Street

Greenwood, Tulsa, Oklahoma

Greenwood was a district in Tulsa, Oklahoma. As one of the most successful and wealthiest African American communities in the United States during the early 20th Century, it was popularly known as America's "Black Wall Street" until the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921...

because of the vibrant business, cultural, and religious community there. The area was the site of the 1921 Tulsa Race War

Tulsa Race Riot

The Tulsa race riot was a large-scale racially motivated conflict, May 31 - June 1st 1921, between the white and black communities of Tulsa, Oklahoma, in which the wealthiest African-American community in the United States, the Greenwood District also known as 'The Negro Wall St' was burned to the...

, one of the United States' deadliest race riots.

Socialists

The Oklahoma Socialist PartySocialist Party of America

The Socialist Party of America was a multi-tendency democratic-socialist political party in the United States, formed in 1901 by a merger between the three-year-old Social Democratic Party of America and disaffected elements of the Socialist Labor Party which had split from the main organization...

achieved a large degree of success in this era (the small party had its highest per-capita membership in Oklahoma at this time with 12,000 dues-paying members in 1914), including the publication of dozens of party newspapers and the election of several hundred local elected officials. Much of their success came from their willingness to reach out to Black and American Indian voters (they were the only party to continue to resist Jim Crow laws), and their willingness to alter traditional Marxist

Marxism

Marxism is an economic and sociopolitical worldview and method of socioeconomic inquiry that centers upon a materialist interpretation of history, a dialectical view of social change, and an analysis and critique of the development of capitalism. Marxism was pioneered in the early to mid 19th...

ideology when it made sense to do so (the biggest changes were the party's support of widespread small-scale land ownership, and their willingness to use religion positively to preach the "Socialist gospel"). The state party also delivered presidential candidate Eugene Debs some of his highest vote counts in the nation.

The party was later crushed into virtual non-existence during the "white terror" that followed the ultra-repressive environment following the Green Corn Rebellion

Green Corn Rebellion

The Green Corn Rebellion was an armed uprising which took place in rural Oklahoma on August 2 and 3, 1917. The uprising was a reaction by radicalized European-American, tenant farmers, Seminoles, Muscogee Creeks and African-Americans to an attempt to enforce the Selective Draft Act of 1917 and was...

and the World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

era paranoia against anyone who spoke against the war or capitalism.

The Industrial Workers of the World

Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World is an international union. At its peak in 1923, the organization claimed some 100,000 members in good standing, and could marshal the support of perhaps 300,000 workers. Its membership declined dramatically after a 1924 split brought on by internal conflict...

tried to gain headway during this period but achieved little success.

Walton

Disgruntled Oklahoma farmers and laborers handed left-wing Democrat Jack C. Walton an easy election victory in 1922 as governor. One scandal followed another—Walton's questionable administrative practices included payroll padding, jailhouse pardons, removal of college administrators, and an enormous increase in the governor's salary. The conservative elements successfully petitioned for a special legislative recall session. To regain the initiative, Walton retaliated by attacking Oklahoma's Ku Klux KlanKu Klux Klan

Ku Klux Klan, often abbreviated KKK and informally known as the Klan, is the name of three distinct past and present far-right organizations in the United States, which have advocated extremist reactionary currents such as white supremacy, white nationalism, and anti-immigration, historically...

with a ban on parades, declaration of martial law, and employment of outsiders to 'keep the peace.' He declared martial law in the entire state and tried to call out the National Guard to block the legislature from holding the special session. That failed, and legislators charged Walton with corruption, impeached him, and removed him from office in 1923.

Dust Bowl Era

During the height of the Great DepressionGreat Depression

The Great Depression was a severe worldwide economic depression in the decade preceding World War II. The timing of the Great Depression varied across nations, but in most countries it started in about 1929 and lasted until the late 1930s or early 1940s...

, drought and poor agricultural practices led to the Dust Bowl

Dust Bowl

The Dust Bowl, or the Dirty Thirties, was a period of severe dust storms causing major ecological and agricultural damage to American and Canadian prairie lands from 1930 to 1936...

, when massive dust storms blew away the soil from large tracts of arable land

Arable land

In geography and agriculture, arable land is land that can be used for growing crops. It includes all land under temporary crops , temporary meadows for mowing or pasture, land under market and kitchen gardens and land temporarily fallow...

and deposited it on nearby farms and ranches, distant states, the Atlantic Ocean, and even occasionally Great Britain. The resulting crop failures forced many small farmers to flee the state altogether. Although the most persistent dust storms primarily affected the Panhandle, much of the state experienced occasional dusters, intermittent severe drought, and occasional searing heat. Towns such as Alva

Alva, Oklahoma

Alva is a city in Woods County, Oklahoma, along the Salt Fork Arkansas River. The population was 4,945 at the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Woods County....

, Altus

Altus, Oklahoma

Altus is a city in Jackson County, Oklahoma, United States. The population was 19,813 at the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Jackson County....

, and Poteau

Poteau, Oklahoma

Poteau is a city in Le Flore County, Oklahoma, United States. It is part of the Fort Smith, Arkansas-Oklahoma Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 8,520 at the 2010 census, ranking fifth in the Greater Fort Smith Area. It is the county seat of Le Flore County...

each recorded temperatures of 120 °F (49 °C) during the epic summer of 1936.

Advances in agro-mechanical technology simultaneously enabled less labor-intensive crop production. Many large landowners and planters had more labor than they needed with the new technology, and the federal Agricultural Adjustment Act

Agricultural Adjustment Act

The Agricultural Adjustment Act was a United States federal law of the New Deal era which restricted agricultural production by paying farmers subsidies not to plant part of their land and to kill off excess livestock...

paid them to reduce production. Plantation owners throughout the American South and much of eastern and southern Oklahoma released their sharecroppers of their debts and evicted them. With few or no local opportunities available for them, many emancipated, but destitute blacks and whites fled to the relative prosperity of California

California

California is a state located on the West Coast of the United States. It is by far the most populous U.S. state, and the third-largest by land area...

to work as migrant farm workers and, after the onset of World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, in factories.

The Grapes of Wrath

The Grapes of Wrath

The Grapes of Wrath is a novel published in 1939 and written by John Steinbeck, who was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1940 and the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1962....

by John Steinbeck

John Steinbeck

John Ernst Steinbeck, Jr. was an American writer. He is widely known for the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Grapes of Wrath and East of Eden and the novella Of Mice and Men...

, photographs by Dorothea Lange

Dorothea Lange

Dorothea Lange was an influential American documentary photographer and photojournalist, best known for her Depression-era work for the Farm Security Administration...

, and songs of Woody Guthrie

Woody Guthrie

Woodrow Wilson "Woody" Guthrie is best known as an American singer-songwriter and folk musician, whose musical legacy includes hundreds of political, traditional and children's songs, ballads and improvised works. He frequently performed with the slogan This Machine Kills Fascists displayed on his...

tales of woe from the era. The negative images of the "Okie

Okie

Okie is a term dating from as early as 1907, originally denoting a resident or native of Oklahoma. It is derived from the name of the state, similar to Texan or Tex for someone from Texas, or Arkie or Arkansawyer for a native of Arkansas....

" as a sort of rootless migrant laborer living in a near-animal state of scrounging for food greatly offended many Oklahomans. These works often mix the experiences of former sharecroppers of the western American South with those of the exodusters fleeing the fierce dust storms of the High Plains. Although they primarily feature the extremely destitute, the vast majority of the people, both staying in and fleeing from Oklahoma, suffered great poverty in the Depression years. Some Oklahoma politicians denounced The Grapes of Wrath (often without reading it) as an attempt to impugn the morals and character of Oklahomans.

After World War II

The term "Okie" in recent years has taken on a new meaning in the past few decades, with many Oklahomans (both former and present) wearing the label as a badge of honor (as a symbol of the Okie survivor attitude). Others (mostly alive during the Dust Bowl era) still see the term negatively because they see the "Okie" migrants as quitters and transplants to the West Coast.Major trends in Oklahoma history after the Depression era included the rise again of tribal sovereignty (including the issuance of tribal automobile license plates, and the opening of tribal smoke shops, casinos, grocery stores, and other commercial enterprises), the building of Tinker Air Force Base

Tinker Air Force Base

Tinker Air Force Base is a major U.S. Air Force base, with tenant U.S. Navy and other Department of Defense missions, located in the southeast Oklahoma City, Oklahoma area, directly south of the suburb of Midwest City, Oklahoma.-Overview:...

, the rapid growth of suburban Oklahoma City and Tulsa, the drop in population in Western Oklahoma, the oil boom of the 1980s and the oil bust of the 1990s.

In recent years, major efforts have been made by state and local leaders to revive Oklahoma's small towns and population centers, which had seen major decline following the oil bust. But Oklahoma City and Tulsa remain economically active in their effort to diversify as the state focuses more into finance and manufacturing.

Oklahoma City Bombing

In 1995 Oklahoma became the scene of one of the worst acts of terrorism ever committed in U.S. History. On April 19, 1995, in the Oklahoma City bombingOklahoma City bombing

The Oklahoma City bombing was a terrorist bomb attack on the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in downtown Oklahoma City on April 19, 1995. It was the most destructive act of terrorism on American soil until the September 11, 2001 attacks. The Oklahoma blast claimed 168 lives, including 19...

, Gulf War

Gulf War

The Persian Gulf War , commonly referred to as simply the Gulf War, was a war waged by a U.N.-authorized coalition force from 34 nations led by the United States, against Iraq in response to Iraq's invasion and annexation of Kuwait.The war is also known under other names, such as the First Gulf...

veteran Timothy McVeigh

Timothy McVeigh

Timothy James McVeigh was a United States Army veteran and security guard who detonated a truck bomb in front of the Alfred P. Murrah Building in Oklahoma City on April 19, 1995...

bombed the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building

Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building

The Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building was a United States Federal Government complex located at 200 N.W. 5th Street in downtown Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, United States. The building was the target of the Oklahoma City bombing on April 19, 1995, which killed 168 people, including 19 children...

, killing 168 people, including 19 children. Timothy McVeigh

Timothy McVeigh

Timothy James McVeigh was a United States Army veteran and security guard who detonated a truck bomb in front of the Alfred P. Murrah Building in Oklahoma City on April 19, 1995...

and Terry Nichols

Terry Nichols

Terry Lynn Nichols is a convicted bomber's accomplice. Prior to his incarceration, he held a variety of short-term jobs, working as a farmer, grain elevator manager, real estate salesman, ranch hand, and house husband. He met his future co-conspirator, Timothy McVeigh, during a brief stint in the...

were the convicted perpetrators of the attack, although many believe others were involved. Timothy McVeigh

Timothy McVeigh

Timothy James McVeigh was a United States Army veteran and security guard who detonated a truck bomb in front of the Alfred P. Murrah Building in Oklahoma City on April 19, 1995...

was later sentenced to death by lethal injection, while his partner, Terry Nichols

Terry Nichols

Terry Lynn Nichols is a convicted bomber's accomplice. Prior to his incarceration, he held a variety of short-term jobs, working as a farmer, grain elevator manager, real estate salesman, ranch hand, and house husband. He met his future co-conspirator, Timothy McVeigh, during a brief stint in the...

, who was convicted of 161 counts of first degree murder received life in prison without the possibility of parole

Parole

Parole may have different meanings depending on the field and judiciary system. All of the meanings originated from the French parole . Following its use in late-resurrected Anglo-French chivalric practice, the term became associated with the release of prisoners based on prisoners giving their...

. It is said that McVeigh stayed at the El Siesta motel

Motel

A motor hotel, or motel for short, is a hotel designed for motorists, and usually has a parking area for motor vehicles...

, a small town motel on US 64 in Vian, Oklahoma

Vian, Oklahoma

Vian is a town in Sequoyah County, Oklahoma, United States. It is part of the Fort Smith, Arkansas-Oklahoma Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 1,362 at the 2000 census. It has three highways running through it: SH 82, or Thornton Street; U.S. 64, or Schley Street; and I-40. It is...

.

See also

- History of the South Central United States

- Oklahoma in the American Civil War

Further reading

- Baird, W. David, and Danney Goble. The Story of Oklahoma (2nd ed. 1994), 511 pages, survey by leading scholars

- Baird, W. David, and Danney Goble. Oklahoma: A History (2008( 342 pp. ISBN 978-0-8061-3910-4, survey by leading scholars

- Castro, J. Justin, “Amazing Grace: The Influence of Christianity in Nineteenth-Century Oklahoma Ozark Music and Society,” Chronicles of Oklahoma, 86 (Winter 2008–2009), 446–68.

- Dale, Edward Everett, and Morris L. Wardell. History of Oklahoma (1948), 574 pp; standard scholarly history online edition from Questia

- Gibson, Arrell Morgan. Oklahoma: A History of Five Centuries (1981) excerpt and text search

- Goble, Danny. Progressive Oklahoma: The Making of a New Kind of State (1979)

- Goins, Charles Robert et al. Historical Atlas of Oklahoma (2006) excerpt and text search

- Gregory, James N. American Exodus: The Dust Bowl Migration and Okie Culture (1991) excerpt and text search

- Reese, Linda Williams. Women of Oklahoma, 1890-1920, (1997) excerpt and text search

- Smith, Michael M., “Latinos in Oklahoma: A History of Four and a Half Centuries,” Chronicles of Oklahoma, 87 (Summer 2009), 186–223.

- Wickett, Murray R. Contested Territory: Whites, Native Americans, and African Americans in Oklahoma 1865-1907 (2000) excerpt and text search