Scots-Irish American

Encyclopedia

Scotch-Irish Americans are an estimated 250,000 Presbyterian and other Protestant dissenters from the Irish province of Ulster

who immigrated to North America

primarily during the colonial era

and their descendants. Some scholars also include the 150,000 Ulster Protestants who immigrated to America during the early 19th century, and their descendants. Most of the Scotch Irish were descended from Scottish and English families who colonized Ireland during the Plantation of Ulster

in the 17th century. While an estimated 36 million Americans (12% of the total population) reported Irish ancestry in 2006, and 6 million (2% of the population) reported Scottish ancestry, an additional 5.4 million (1.8% of the population) identified more specifically with Scotch Irish ancestry. People in Great Britain or Ireland that are of a similar ancestry usually refer to themselves as Ulster Scots, with the term Scotch-Irish used only in North America.

almost unknown in England, Ireland or Scotland. The term is somewhat unclear because some of the Scotch-Irish had little or no Scottish ancestry at all, as dissenter families had also been transplanted to Ulster from northern England, Wales and the London area, and some from Flanders

, the German Palatinate

, and France (such as the French Huguenot

ancestors of Davy Crockett

). What united these different national groups was their common Calvinist beliefs, and their separation from the established church

(Church of England

and Church of Ireland

in this case). Nevertheless, a large Scottish element in the Plantation of Ulster gave the settlements a Scottish character.

Upon arrival in America, the Scotch-Irish at first usually referred to themselves simply as Irish, without the qualifier Scotch. It was not until a century later, following the surge in Irish immigration after the Great Irish Famine of the 1840s, that the descendants of the earlier arrivals began to commonly call themselves Scotch-Irish to distinguish them from the newer, largely destitute and predominantly Catholic immigrants. The two groups had little interaction in America, as the Scotch-Irish had become settled years earlier primarily in the Appalachian

region, while the new wave of Irish American families settled primarily in northern and midwestern port cities such as Boston, New York, or Chicago. However, many Irish migrated to the interior in the 19th century to work on large-scale infrastructure projects such as canals and railroads.

The usage Scots-Irish is a relatively recent version of the term. Two early citations include: 1) "a grave, elderly man of the race known in America as " Scots-Irish" (1870); and 2) "Dr. Cochran was of stately presence, of fair and florid complexion, features which testified his Scots-Irish descent" (1884)

English author Kingsley Amis

endorsed the traditional Scotch-Irish usage implicitly in noting that "nobody talks about butterscottish or hopscots,...or Scottish pine", and that while Scots or Scottish is how people of Scots origin refer to themselves in Scotland itself, the traditional English usage Scotch continues to be appropriate in "compounds and set phrases".

In the Ulster-Scots language (or "Ullans"), the Scotch-Irish are referred to as the Scotch Airish (o' Amerikey).

Transatlantic flows were halted by the American Revolution

, but resumed after 1783, with total of 100,000 arriving in America between 1783 and 1812. By that point few were young servants and more were mature craftsmen and they settled in industrial centers, including Pittsburgh, Philadelphia and New York, where many became skilled workers, foremen and entrepreneurs as the Industrial Revolution

took off in the U.S. Another half million came to American 1815 to 1845; another 900,000 came in 1851-99. From 1900 to 1930 the average was about 5,000 to 10,000 a year. Relatively few came after 1930. At every stage a majority were Presbyterians

, and that religion decisively shaped Scotch-Irish culture.

According to the Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups, there were 400,000 U.S. residents of Irish birth or ancestry in 1790 and half of this group was descended from Ulster, and half from the other three provinces of Ireland.

A separate migration brought many to Canada

, where they are most numerous in rural Ontario

.

. Gaels

from Ireland colonised current South-West Scotland as part of the Kingdom of Dál Riata

, eventually replacing the native Pictish

culture throughout Scotland. These Gaels had previously been named Scoti

by the Romans

, and eventually the name was applied to the entire Kingdom of Scotland

.

The origins of the Scotch-Irish lie primarily in the Lowlands

of Scotland

and in northern England

, particularly in the Border Country

on either side of the Anglo-Scottish border

, a region that had seen centuries of conflict. In the near constant state of war between England and Scotland during the Middle Ages, the livelihood of the people on the borders was devastated by the contending armies. Even when the countries were not at war, tension remained high, and royal authority in one or the other kingdom was often weak. The uncertainty of existence led the people of the borders to seek security through a system of family ties, similar to the clan system

in the Scottish Highlands. Known as the Border Reivers

, these families relied on their own strength and cunning to survive, and a culture of cattle raiding and thievery developed.

Scotland and England became unified under a single monarch with the Union of the Crowns

Scotland and England became unified under a single monarch with the Union of the Crowns

in 1603, when James VI

, King of Scots, succeeded Elizabeth I as ruler of England. In addition to the unstable border region, James also inherited Elizabeth's conflicts in Ireland. Following the end of the Irish Nine Years' War

in 1603, and the Flight of the Earls

in 1607, James embarked in 1609 on a systematic plantation of English and Scottish Protestant settlers to Ireland's northern province of Ulster. The Plantation of Ulster was seen as a way to relocate the Border Reiver families to Ireland to bring peace to the Anglo-Scottish border country, and also to provide fighting men who could suppress the native Irish in Ireland.

The first major influx of Scots and English into Ulster had come in 1606 during the settlement of east Down

onto land cleared of native Irish by private landlords chartered by James. This process was accelerated with James's official plantation in 1609, and further augmented during the subsequent Irish Confederate Wars

. The first of the Stuart

Kingdoms to collapse into civil war was Ireland, where, prompted in part by the anti-Catholic rhetoric of the Covenanters, Irish Catholics launched a rebellion in October

. In reaction to the proposal by Charles I

and Thomas Wentworth to raise an army manned by Irish Catholics to put down the Covenanter movement in Scotland, the Parliament of Scotland

had threatened to invade Ireland in order to achieve "the extirpation of Popery out of Ireland" (according to the interpretation of Richard Bellings

, a leading Irish politician of the time). The fear this caused in Ireland unleashed a wave of massacres against Protestant English and Scottish settlers, mostly in Ulster, once the rebellion had broken out. All sides displayed extreme cruelty in this phase of the war. Around 4000 settlers were massacred and a further 12,000 may have died of privation after being driven from their homes. In one notorious incident, the Protestant inhabitants of Portadown

were taken captive and then massacred on the bridge in the town. The settlers responded in kind, as did the British-controlled government in Dublin, with attacks on the Irish civilian population. Massacres of native civilians occurred at Rathlin Island

and elsewhere. In early 1642, the Covenanters sent an army to Ulster

to defend the Scottish settlers there from the Irish rebels who had attacked them after the outbreak of the rebellion. The original intention of the Scottish army was to re-conquer Ireland, but due to logistical and supply problems, it was never in a position to advance far beyond its base in eastern Ulster. The Covenanter force remained in Ireland until the end of the civil wars but was confined to its garrison around Carrickfergus

after its defeat by the native Ulster Army at the Battle of Benburb

in 1646. After the war was over, many of the soldiers settled permanently in Ulster. Another major influx of Scots into Ulster occurred in the 1690s, when tens of thousands of people fled a famine in Scotland to come to Ireland.

Just a few generations after arriving in Ireland, considerable numbers of Ulster-Scots emigrated to the North American colonies of Great Britain

throughout the 18th century (between 1717 and 1770 alone, about 250,000 settled in what would become the United States

). According to Kerby Miller, Emigrants and Exiles: Ireland and the Irish Exodus to North America (1988), Protestants

were one-third the population of Ireland, but three-quarters of all emigrants leaving from 1700 to 1776; 70% of these Protestants were Presbyterians. Other factors contributing to the mass exodus of Ulster Scots to America during the 18th century were a series of drought

s and rising rents imposed by often absentee

English and/or Anglo-Irish

landlords.

During the course of the 17th century, the number of settlers belonging to Calvinist dissenting sects, including Scottish

and Northumbria

n Presbyterians

, English Baptists, French and Flemish Huguenot

s, and German Palatines

, became the majority among the Protestant settlers in the province of Ulster. However, the Presbyterians and other dissenters, along with Catholics, were not members of the established church and were consequently legally disadvantaged by the Penal Laws

, which gave full rights only to members of the Church of England

/Church of Ireland

. Those members of the state church

were often absentee landlord

s and the descendants of English title-holding

settlers. For this reason, up until the 19th century, and despite their common fear of the dispossessed Catholic native Irish, there was considerable disharmony between the Presbyterians

and the Protestant Ascendancy

in Ulster. As a result of this many Ulster-Scots, along with Catholic native Irish, ignored religious differences to join the United Irishmen and participate in the Irish Rebellion of 1798

, in support of Age of Enlightenment

-inspired egalitarian

and republican

goals.

has often been applied to their descendants in the mountains, carrying connotations of poverty, backwardness and violence; this word having its origins in Scotland and Ireland.

The first trickle of Scotch-Irish settlers arrived in New England. Valued for their fighting prowess as well as for their Protestant dogma, they were invited by Cotton Mather

and other leaders to come over to help settle and secure the frontier. In this capacity, many of the first permanent settlements in Maine

and New Hampshire

, especially after 1718, were Scotch-Irish and many place names as well as the character of Northern New Englanders reflect this fact. The Scotch-Irish brought the potato with them from Ireland (although the potato originated in South America, it was not known in North America until brought over from Europe). In Maine it became a staple crop as well as an economic base.

From 1717 to the next thirty or so years, the primary points of entry for the Ulster immigrants were Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and New Castle, Delaware. The Scotch-Irish radiated westward across the Alleghenies

, as well as into Virginia

, North Carolina

, South Carolina

, Georgia

, Kentucky

, and Tennessee

. The typical migration involved small networks of related families who settled together, worshipped together, and intermarried, avoiding outsiders.

described as "the cutting-edge of the frontier."

The Scotch-Irish moved up the Delaware River to Bucks County, and then up the Susquehanna and Cumberland valleys, finding flat lands along the rivers and creeks to set up their log cabins, their grist mills, and their Presbyterian churches. Chester, Lancaster, and Dauphin counties became their strongholds, and they built towns such as Chambersburg, Gettysburg, Carlisle, and York; the next generation moved into western Pennsylvania. With large numbers of children who needed their own inexpensive farms, the Scotch-Irish avoided areas already settled by Germans and Quakers and moved south, down the Shenandoah Valley

, and through the Blue Ridge Mountains into Virginia. These migrants followed the Great Wagon Road

from Lancaster, through Gettysburg, and down through Staunton, Virginia, to Big Lick (now Roanoke), Virginia. Here the pathway split, with the Wilderness Road

taking settlers west into Tennessee and Kentucky, while the main road continued south into the Carolinas.

and Pontiac’s Rebellion that followed. The Scotch-Irish were frequently in conflict with the Indian tribes who lived on the other side of the frontier; indeed, they did most of the Indian fighting on the American frontier from New Hampshire to the Carolinas. The Irish and Scots also became the middlemen who handled trade and negotiations between the Indian tribes and the colonial governments.

Especially in Pennsylvania, whose pacifist Quaker leaders had made no provision for a militia, Scotch-Irish settlements were frequently destroyed and the settlers killed, captured or forced to flee after attacks by Native Americans from tribes of the Delaware (Lenape

), Shawnee, Seneca, and others of western Pennsylvania and the Ohio country. Indian attacks were taking place within 60 miles of Philadelphia, and in July 1763, the Pennsylvania Assembly authorized a 700-strong militia to be raised, to be used only for defensive actions. Formed into two units of rangers, the Cumberland Boys and the Paxton Boys

, the militia soon exceeded their defensive mandate and began offensive forays against Lenape villages in western Pennsylvania. After attacking Delaware villages in the upper Susquehanna

valley, the militia leaders received information, which they believed credible, that “hostile” tribes were receiving weapons and ammunition from the “friendly” tribe of Conestogas settled in Lancaster County, who were under the protection of the Pennsylvania Assembly. On 14 December 1763, about fifty Paxton Boys rode to Conestogatown, near Millersville, PA, and murdered six Conestogas. Governor John Penn

placed the remaining fourteen Conestogas in protective custody in the Lancaster

workhouse, but the Paxton Boys broke in, killing and mutilating all fourteen on 27 December 1763. Following this, about 400 backcountry settlers, primarily Scotch-Irish, marched on Philadelphia demanding better military protection for their settlements, and pardons for the Paxton Boys. Benjamin Franklin

led the politicians who negotiated a settlement with the Paxton leaders, after which they returned home.

contained fifty-six delegate signatures. Of the signers, eight were of Irish descent. Three signers, Matthew Thornton

, George Taylor

and James Smith were born in Ulster, the remaining five Irish Americans were the sons or grandsons of Irish immigrants: George Read

, Thomas McKean

, Thomas Lynch, Jr.

, Edward Rutledge

and Charles Carroll

, and at least McKean had Ulster heritage.

The Scotch-Irish were generally ardent supporters of American Independence from Britain in the 1770s. In Pennsylvania, Virginia, and most of the Carolinas, support for the revolution was "practically unanimous." One Hessian officer said, "Call this war by whatever name you may, only call it not an American rebellion; it is nothing more or less than a Scotch Irish Presbyterian rebellion." A British major general testified to the House of Commons that "half the rebel Continental Army were from Ireland". Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, with its large Scotch-Irish population, was to make the first declaration for independence from Britain in the Mecklenburg Declaration of 1775.

The Scotch-Irish "Overmountain Men

" of Virginia and North Carolina formed a militia which won the Battle of Kings Mountain

in 1780, resulting in the British abandonment of a southern campaign, and for some historians "marked the turning point of the American Revolution".

Just prior to the Revolution, a second stream of immigrants came directly from Ireland via Charleston. This group was forced to move into an underdeveloped area because they could not afford expensive land. Most of this group remained loyal to the crown or neutral when the war began. Prior to Charles Cornwallis's march into the backcountry in 1780, two-thirds of the men among the Waxhaw settlement had declined to serve in the army. British victory at the Battle of the Waxhaws resulted in anti-British sentiment in a bitterly divided region. While many individuals chose to take up arms against the British, the British themselves forced the people to choose sides.

, and the Congress placed a tax on whiskey (among other things) to help repay those debts. Large producers were assessed a tax of six cents a gallon. Smaller producers, many of whom were Scottish (often Ulster-Scots) descent and located in the more remote areas, were taxed at a higher rate of nine cents a gallon. These rural settlers were short of cash to begin with, and lacked any practical means to get their grain to market, other than fermenting and distilling it into relatively portable spirits. From Pennsylvania

to Georgia

, the western counties engaged in a campaign of harassment of the federal tax collectors. "Whiskey Boys" also conducted violent protests in Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina and South Carolina, and Georgia. This civil disobedience eventually culminated in armed conflict in the Whiskey Rebellion

. President George Washington

marched at the head of 13,000 soldiers to suppress the insurrection.

puts forth a thesis in his book Born Fighting to suggest that the character traits he ascribes to the Scotch-Irish such as loyalty to kin

, extreme mistrust of governmental authority and legal strictures, and a propensity to bear arms and to use them, helped shape the American identity. In the same year that Webb's book was released, Barry Vann published his second book entitled Rediscovering the South's Celtic Heritage. Like his earlier book, From Whence They Came (1998), Vann argues that these traits have left their imprint on the Upland South. In 2008, Vann followed up his earlier work with a book entitled In Search of Ulster Scots Land: The Birth and Geotheological Imagings of a Transatlantic People which professes how these traits may manifest themselves in conservative voting patterns and religious affiliation that characterizes the Bible Belt.

Indeed new immigrants after 1800 made Pittsburgh a major Scotch Irish stronghold. For example, Thomas Mellon

(b. Ulster 1813-1908) left Ireland in 1823 and became the founder of the famous Mellon clan, which played a central role in banking and industries such as aluminum and oil. As Barnhisel (2005) finds, industrialists such as James H. Laughlin

(b. Ulster 1806-1882) of Jones and Laughlin Steel Company

constituted the "Scots-Irish Presbyterian ruling stratum of Pittsburgh society."

.

The border origin of the Scotch-Irish is supported by study of the traditional music and folklore of the Appalachian Mountains

, settled primarily by the Scotch-Irish in the 18th century. Musicologist Cecil Sharp

collected hundreds of folk songs in the region, and observed that the musical tradition of the people "seems to point to the North of England, or to the Lowlands, rather than the Highlands, of Scotland, as the country from which they originally migrated. For the Appalachian tunes...have far more affinity with the normal English folk-tune than with that of the Gaelic-speaking Highlander." Similarly, elements of mountain folklore trace back to events in the Lowlands of Scotland. As an example, it was recorded in the early 20th century that Appalachian children were frequently warned, "You must be good or Clavers will get you." To the mountain residents, "Clavers" was simply a bogeyman

used to keep children in line, yet unknown to them the phrase derives from the 17th century Scotsman John Graham of Claverhouse

, called "Bloody Clavers" by the Presbyterian Scottish Lowlanders whose religion he tried to suppress.

in 1763, Protestant Irish, both Irish Anglicans and Ulster-Scottish Presbyterians, migrated over the decades to Upper Canada

, some as United Empire Loyalists

or directly from Ulster

.

The first significant number of Canadian settlers to arrive from Ireland were Protestants from predominantly Ulster

and largely of Scottish

descent who settled in the mainly central Nova Scotia in the 1760s. Many came through the efforts of colonizer Alexander McNutt. Some came directly from Ulster whilst others arrived after via New England.

Ulster-Scottish migration to Western Canada

has two distinct components, those who came via eastern Canada or the US, and those who came directly from Ireland. Many who came West were fairly well assimilated, in that they spoke English and understood British customs and law, and tended to be regarded as just a part of English Canada

. However, this picture was complicated by the religious division. Many of the original "English" Canadian settlers in the Red River Colony

were fervent Irish loyalist

Protestants, and members of the Orange Order

.

In 1806, The Benevolent Irish Society

(BIS) was founded as a philanthropic organization in St. John's, Newfoundland. Membership was open to adult residents of Newfoundland who were of Irish birth or ancestry, regardless of religious persuasion. The BIS was founded as a charitable, fraternal, middle-class social organization, on the principles of "benevolence and philanthropy", and had as its original objective to provide the necessary skills which would enable the poor to better themselves. Today the society is still active in Newfoundland and is the oldest philanthropic organization in North America

.

In 1877, a breakthrough in Irish Canadian Protestant-Catholic relations occurred in London, Ontario

. This was the founding of the Irish Benevolent Society, a brotherhood of Irishmen and women of both Catholic and Protestant faiths. The society promoted Irish Canadian culture, but it was forbidden for members to speak of Irish politics when meeting. This companionship of Irish people of all faiths quickly tore down the walls of sectarianism in Ontario. Today, the Society is still operating.

For years, Prince Edward Island

had been divided between Catholics and Protestants. In the latter half of the 20th century, this sectarianism diminished and was ultimately destroyed recently after two events occurred. Firstly, the Catholic and Protestant school boards were merged into one secular institution, and secondly, the practice of electing two MLAs for each provincial riding (one Catholic and one Protestant) was ended.

An affidavit of William Patent, dated March 15, 1689, in a case against a Mr. Matthew Scarbrough in Somerset County, Maryland, quotes Mr. Patent as saying he was told by Scarbrough that "...it was no more sin to kill me then to kill a dogg, or any Scotch Irish dogg..."

Leyburn cites several early American uses of the term.

The Oxford English Dictionary says the first use of the term Scotch-Irish came in Pennsylvania in 1744. Its citations are:

In Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways in America (America: a cultural history), historian David Hackett Fischer

asserts:

Fischer prefers to speak of "borderers" (referring to the historically war-torn England-Scotland border) as the population ancestral to the "backcountry" "cultural stream" (one of the four major and persistent cultural streams he identifies in American history) and notes the borderers were not purely Celtic but also had substantial Anglo-Saxon

and Viking

or Scandinavia

n roots, and were quite different from Celtic-speaking groups like the Scottish Highlanders or Irish (that is, Gaelic-speaking and Roman Catholic).

An example of the use of the term is found in A History of Ulster: "Ulster Presbyterians – known as the 'Scotch Irish' – were already accustomed to being on the move, and clearing and defending their land."

Other terms used to describe the Scotch-Irish include Northern Irish or Irish Presbyterians.

While Scotch-Irish is the term most used in scholarship to describe these people, the use of the term can draw ire from both Scots and Irish. To the Scots, the term Scotch is derogatory when referring to a person or people, and should be applied only to whisky

. Many Irish have claimed that such a distinction should not be used, and that those called Scotch-Irish are simply Irish. However, as one scholar observed, "...in this country [USA], where they have been called Scotch-Irish for over two hundred years, it would be absurd to give them a name by which they are not known here... Here their name is Scotch-Irish; let us call them by it."

A false myth claims that Queen Elizabeth used the term. Another myth is that Shakespeare used the spelling 'Scotch' as a proper noun, but his only use of the word in any of his writings is as a verb, as in scotching a snake, being scotched, etc.

It was also used to differentiate from either the Anglo-Irish

, Irish Catholics, or immigrants who came directly from Scotland.

The word "Scotch" was the favoured adjective as a designation — it literally means "... of Scotland". People in Scotland

refer to themselves as Scots

, or adjectivally/collectively as Scots or as being Scottish

, rather than Scotch.

regions and the Ohio

Valley. Others settled in northern New England

, The Carolinas

, Georgia

and north-central Nova Scotia

.

In the United States Census, 2000

, 4.3 million Americans (1.5% of the U.S. population) claimed Scotch-Irish ancestry.

Interestingly, the areas where the most Americans reported themselves in the 2000 Census only as "American" with no further qualification (e.g. Kentucky

Interestingly, the areas where the most Americans reported themselves in the 2000 Census only as "American" with no further qualification (e.g. Kentucky

, north-central Texas

, and many other areas in the Southern US; overall 7% of Americans reported "American") are largely the areas where many Scotch-Irish settled, and are in complementary distribution with the areas which most heavily report Scotch-Irish ancestry, though still at a lower rate than "American" (e.g. western North Carolina

and eastern Tennessee

, western Pennsylvania

, northern New England

, south-central and far northern Texas, westernmost Florida Panhandle

, many rural areas in the Northwest); see Maps of American ancestries

.

. Many of the settlers in the Plantation of Ulster had been from dissenting/non-conformist religious groups which professed a strident Calvinism

. These included mainly Lowland Scot Presbyterians, but also English Puritan

s and Quakers, French Huguenot

s and German Palatines

. These Calvinist groups mingled freely in church matters, and religious belief was more important than nationality, as these groups aligned themselves against both their Catholic

Irish and Anglican English neighbors.

After their arrival in the New World, the predominantly Presbyterian Scotch-Irish began to move further into the mountainous back-country of Virginia and the Carolinas. The establishment of many settlements in the remote back-country put a strain on the ability of the Presbyterian Church to meet the new demand for qualified, college-educated clergy. Religious groups such as the Baptists and Methodists had no higher education requirement for their clergy to be ordained, and these groups readily provided ministers to meet the demand of the growing Scotch-Irish settlements. By about 1810, Baptist and Methodist churches were in the majority, and the descendants of the Scotch-Irish today remain predominantly Baptist or Methodist. Vann (2007) shows the Scotch-Irish played a major role in defining the Bible Belt

in the Upper South in the 18th century. He emphasizes the high educational standards they sought, their 'geotheological thought worlds' brought from the old country, and their political independence that was transferred to frontier religion.

. The mission was training New Light Presbyterian ministers. The College became educational as well as religious capital of Scotch-Irish America. By 1808 loss of confidence in the College within the Presbyterian Church led to the establishment of the separate Princeton Theological Seminary

, but for many decades Presbyterian control over the college continued. Meanwhile Princeton Seminary, under the leadership of Charles Hodge

, originated a conservative theology that in large part shaped Fundamentalist Protestantism in the 20th century.

in 1858. It became the Associate Reformed Synod of the West and remain centered in the Midwest. It withdrew from the parent body in 1820 because of the drift of the eastern churches toward assimilation into the larger Presbyterian Church with its Yankee traits. The Associate Reformed Synod of the West maintained the characteristics of an immigrant church with Scotch-Irish roots, emphasized the Westminster standards, used only the psalms in public worship, was Sabbatarian, and was strongly abolitionist and anti-Catholic. In the 1850s it exhibited many evidences of assimilation. It showed greater ecumenical interest, greater interest in evangelization of the West and of the cities, and a declining interest in maintaining the unique characteristics of its Scotch-Irish past.

, including three whose parents were born in Ulster. The Irish Protestant vote in the U.S. has not been studied nearly as much as have the Catholic Irish. (On the Catholic vote see Irish Americans). In the 1820s and 1830s, supporters of Andrew Jackson

emphasized his Irish background, as did James Knox Polk, but since the 1840s it has been uncommon for a Protestant politician in America to be identified as Irish, but rather as 'Scotch-Irish'. In Canada, by contrast, Irish Protestants remained a cohesive political force well into the 20th century, identified with the then Conservative Party of Canada

and especially with the Orange Institution

, although this is less evident in today's politics.

More than one-third of all U.S. Presidents had substantial ancestral origins in the northern province of Ireland (Ulster). President Bill Clinton spoke proudly of that fact, and his own ancestral links with the province, during his two visits to Ulster. Like most US citizens, most US presidents are the result of a "melting pot

" of ancestral origins.

Clinton is one of at least seventeen Chief Executives descended from emigrants to the United States from the north of Ireland. While many of the Presidents have typically Ulster-Scots surnames – Jackson, Johnson, McKinley, Wilson – others, such as Roosevelt and Cleveland, have links which are less obvious.

Andrew Jackson

James Knox Polk

James Buchanan

Andrew Johnson

Ulysses S. Grant

Chester A. Arthur

Grover Cleveland

Benjamin Harrison

William McKinley

Theodore Roosevelt

Woodrow Wilson

Richard Nixon

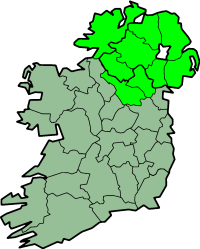

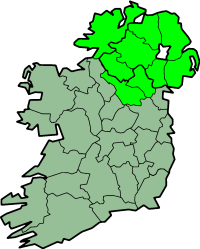

Ulster

Ulster is one of the four provinces of Ireland, located in the north of the island. In ancient Ireland, it was one of the fifths ruled by a "king of over-kings" . Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the ancient kingdoms were shired into a number of counties for administrative and judicial...

who immigrated to North America

North America

North America is a continent wholly within the Northern Hemisphere and almost wholly within the Western Hemisphere. It is also considered a northern subcontinent of the Americas...

primarily during the colonial era

Colonial America

The colonial history of the United States covers the history from the start of European settlement and especially the history of the thirteen colonies of Britain until they declared independence in 1776. In the late 16th century, England, France, Spain and the Netherlands launched major...

and their descendants. Some scholars also include the 150,000 Ulster Protestants who immigrated to America during the early 19th century, and their descendants. Most of the Scotch Irish were descended from Scottish and English families who colonized Ireland during the Plantation of Ulster

Plantation of Ulster

The Plantation of Ulster was the organised colonisation of Ulster—a province of Ireland—by people from Great Britain. Private plantation by wealthy landowners began in 1606, while official plantation controlled by King James I of England and VI of Scotland began in 1609...

in the 17th century. While an estimated 36 million Americans (12% of the total population) reported Irish ancestry in 2006, and 6 million (2% of the population) reported Scottish ancestry, an additional 5.4 million (1.8% of the population) identified more specifically with Scotch Irish ancestry. People in Great Britain or Ireland that are of a similar ancestry usually refer to themselves as Ulster Scots, with the term Scotch-Irish used only in North America.

Terminology

Scotch-Irish is an AmericanismAmerican English

American English is a set of dialects of the English language used mostly in the United States. Approximately two-thirds of the world's native speakers of English live in the United States....

almost unknown in England, Ireland or Scotland. The term is somewhat unclear because some of the Scotch-Irish had little or no Scottish ancestry at all, as dissenter families had also been transplanted to Ulster from northern England, Wales and the London area, and some from Flanders

Flanders

Flanders is the community of the Flemings but also one of the institutions in Belgium, and a geographical region located in parts of present-day Belgium, France and the Netherlands. "Flanders" can also refer to the northern part of Belgium that contains Brussels, Bruges, Ghent and Antwerp...

, the German Palatinate

German Palatines

The German Palatines were natives of the Electoral Palatinate region of Germany, although a few had come to Germany from Switzerland, the Alsace, and probably other parts of Europe. Towards the end of the 17th century and into the 18th, the wealthy region was repeatedly invaded by French troops,...

, and France (such as the French Huguenot

Huguenot

The Huguenots were members of the Protestant Reformed Church of France during the 16th and 17th centuries. Since the 17th century, people who formerly would have been called Huguenots have instead simply been called French Protestants, a title suggested by their German co-religionists, the...

ancestors of Davy Crockett

Davy Crockett

David "Davy" Crockett was a celebrated 19th century American folk hero, frontiersman, soldier and politician. He is commonly referred to in popular culture by the epithet "King of the Wild Frontier". He represented Tennessee in the U.S...

). What united these different national groups was their common Calvinist beliefs, and their separation from the established church

State church

State churches are organizational bodies within a Christian denomination which are given official status or operated by a state.State churches are not necessarily national churches in the ethnic sense of the term, but the two concepts may overlap in the case of a nation state where the state...

(Church of England

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

and Church of Ireland

Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland is an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. The church operates in all parts of Ireland and is the second largest religious body on the island after the Roman Catholic Church...

in this case). Nevertheless, a large Scottish element in the Plantation of Ulster gave the settlements a Scottish character.

Upon arrival in America, the Scotch-Irish at first usually referred to themselves simply as Irish, without the qualifier Scotch. It was not until a century later, following the surge in Irish immigration after the Great Irish Famine of the 1840s, that the descendants of the earlier arrivals began to commonly call themselves Scotch-Irish to distinguish them from the newer, largely destitute and predominantly Catholic immigrants. The two groups had little interaction in America, as the Scotch-Irish had become settled years earlier primarily in the Appalachian

Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains #Whether the stressed vowel is or ,#Whether the "ch" is pronounced as a fricative or an affricate , and#Whether the final vowel is the monophthong or the diphthong .), often called the Appalachians, are a system of mountains in eastern North America. The Appalachians...

region, while the new wave of Irish American families settled primarily in northern and midwestern port cities such as Boston, New York, or Chicago. However, many Irish migrated to the interior in the 19th century to work on large-scale infrastructure projects such as canals and railroads.

The usage Scots-Irish is a relatively recent version of the term. Two early citations include: 1) "a grave, elderly man of the race known in America as " Scots-Irish" (1870); and 2) "Dr. Cochran was of stately presence, of fair and florid complexion, features which testified his Scots-Irish descent" (1884)

English author Kingsley Amis

Kingsley Amis

Sir Kingsley William Amis, CBE was an English novelist, poet, critic, and teacher. He wrote more than 20 novels, six volumes of poetry, a memoir, various short stories, radio and television scripts, along with works of social and literary criticism...

endorsed the traditional Scotch-Irish usage implicitly in noting that "nobody talks about butterscottish or hopscots,...or Scottish pine", and that while Scots or Scottish is how people of Scots origin refer to themselves in Scotland itself, the traditional English usage Scotch continues to be appropriate in "compounds and set phrases".

In the Ulster-Scots language (or "Ullans"), the Scotch-Irish are referred to as the Scotch Airish (o' Amerikey).

Migration

From 1710 to 1775, over 200,000 people emigrated from Ulster to the 13 Colonies, from Maine to Georgia. The largest numbers went to Pennsylvania. From that base some went south into Virginia, the Carolinas and across the South, with a large concentration in the Appalachian region; others headed west to western Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, and the Midwest.Transatlantic flows were halted by the American Revolution

American Revolution

The American Revolution was the political upheaval during the last half of the 18th century in which thirteen colonies in North America joined together to break free from the British Empire, combining to become the United States of America...

, but resumed after 1783, with total of 100,000 arriving in America between 1783 and 1812. By that point few were young servants and more were mature craftsmen and they settled in industrial centers, including Pittsburgh, Philadelphia and New York, where many became skilled workers, foremen and entrepreneurs as the Industrial Revolution

Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was a period from the 18th to the 19th century where major changes in agriculture, manufacturing, mining, transportation, and technology had a profound effect on the social, economic and cultural conditions of the times...

took off in the U.S. Another half million came to American 1815 to 1845; another 900,000 came in 1851-99. From 1900 to 1930 the average was about 5,000 to 10,000 a year. Relatively few came after 1930. At every stage a majority were Presbyterians

Presbyterianism

Presbyterianism refers to a number of Christian churches adhering to the Calvinist theological tradition within Protestantism, which are organized according to a characteristic Presbyterian polity. Presbyterian theology typically emphasizes the sovereignty of God, the authority of the Scriptures,...

, and that religion decisively shaped Scotch-Irish culture.

According to the Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups, there were 400,000 U.S. residents of Irish birth or ancestry in 1790 and half of this group was descended from Ulster, and half from the other three provinces of Ireland.

A separate migration brought many to Canada

Irish Canadian

Irish Canadian are immigrants and descendants of immigrants who originated in Ireland. 1.2 million Irish immigrants arrived, 1825 to 1970, at least half of those in the period from 1831-1850. By 1867, they were the second largest ethnic group , and comprised 24% of Canada's population...

, where they are most numerous in rural Ontario

Ontario

Ontario is a province of Canada, located in east-central Canada. It is Canada's most populous province and second largest in total area. It is home to the nation's most populous city, Toronto, and the nation's capital, Ottawa....

.

Origins

Because of the close proximity of the islands of Britain and Ireland, migrations in both directions had been occurring since Ireland was first settled after the retreat of the ice sheetsIce age

An ice age or, more precisely, glacial age, is a generic geological period of long-term reduction in the temperature of the Earth's surface and atmosphere, resulting in the presence or expansion of continental ice sheets, polar ice sheets and alpine glaciers...

. Gaels

Gaels

The Gaels or Goidels are speakers of one of the Goidelic Celtic languages: Irish, Scottish Gaelic, and Manx. Goidelic speech originated in Ireland and subsequently spread to western and northern Scotland and the Isle of Man....

from Ireland colonised current South-West Scotland as part of the Kingdom of Dál Riata

Dál Riata

Dál Riata was a Gaelic overkingdom on the western coast of Scotland with some territory on the northeast coast of Ireland...

, eventually replacing the native Pictish

Picts

The Picts were a group of Late Iron Age and Early Mediaeval people living in what is now eastern and northern Scotland. There is an association with the distribution of brochs, place names beginning 'Pit-', for instance Pitlochry, and Pictish stones. They are recorded from before the Roman conquest...

culture throughout Scotland. These Gaels had previously been named Scoti

Scoti

Scoti or Scotti was the generic name used by the Romans to describe those who sailed from Ireland to conduct raids on Roman Britain. It was thus synonymous with the modern term Gaels...

by the Romans

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

, and eventually the name was applied to the entire Kingdom of Scotland

Kingdom of Scotland

The Kingdom of Scotland was a Sovereign state in North-West Europe that existed from 843 until 1707. It occupied the northern third of the island of Great Britain and shared a land border to the south with the Kingdom of England...

.

The origins of the Scotch-Irish lie primarily in the Lowlands

Scottish Lowlands

The Scottish Lowlands is a name given to the Southern half of Scotland.The area is called a' Ghalldachd in Scottish Gaelic, and the Lawlands ....

of Scotland

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

and in northern England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

, particularly in the Border Country

Border Country

Border Country is a novel by Raymond Williams. The book was re-published in December 2005 as one of the first group of titles in the Library of Wales series, having been out of print for several years. Written in English, the novel was first published in 1960.It is set in rural South Wales, close...

on either side of the Anglo-Scottish border

Anglo-Scottish border

The Anglo-Scottish border is the official border and mark of entry between Scotland and England. It runs for 154 km between the River Tweed on the east coast and the Solway Firth in the west. It is Scotland's only land border...

, a region that had seen centuries of conflict. In the near constant state of war between England and Scotland during the Middle Ages, the livelihood of the people on the borders was devastated by the contending armies. Even when the countries were not at war, tension remained high, and royal authority in one or the other kingdom was often weak. The uncertainty of existence led the people of the borders to seek security through a system of family ties, similar to the clan system

Scottish clan

Scottish clans , give a sense of identity and shared descent to people in Scotland and to their relations throughout the world, with a formal structure of Clan Chiefs recognised by the court of the Lord Lyon, King of Arms which acts as an authority concerning matters of heraldry and Coat of Arms...

in the Scottish Highlands. Known as the Border Reivers

Border Reivers

Border Reivers were raiders along the Anglo–Scottish border from the late 13th century to the beginning of the 17th century. Their ranks consisted of both Scottish and English families, and they raided the entire border country without regard to their victims' nationality...

, these families relied on their own strength and cunning to survive, and a culture of cattle raiding and thievery developed.

Union of the Crowns

The Union of the Crowns was the accession of James VI, King of Scots, to the throne of England, and the consequential unification of Scotland and England under one monarch. The Union of Crowns followed the death of James' unmarried and childless first cousin twice removed, Queen Elizabeth I of...

in 1603, when James VI

James I of England

James VI and I was King of Scots as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the English and Scottish crowns on 24 March 1603...

, King of Scots, succeeded Elizabeth I as ruler of England. In addition to the unstable border region, James also inherited Elizabeth's conflicts in Ireland. Following the end of the Irish Nine Years' War

Nine Years' War (Ireland)

The Nine Years' War or Tyrone's Rebellion took place in Ireland from 1594 to 1603. It was fought between the forces of Gaelic Irish chieftains Hugh O'Neill of Tír Eoghain, Hugh Roe O'Donnell of Tír Chonaill and their allies, against English rule in Ireland. The war was fought in all parts of the...

in 1603, and the Flight of the Earls

Flight of the Earls

The Flight of the Earls took place on 14 September 1607, when Hugh Ó Neill of Tír Eóghain, Rory Ó Donnell of Tír Chonaill and about ninety followers left Ireland for mainland Europe.-Background to the exile:...

in 1607, James embarked in 1609 on a systematic plantation of English and Scottish Protestant settlers to Ireland's northern province of Ulster. The Plantation of Ulster was seen as a way to relocate the Border Reiver families to Ireland to bring peace to the Anglo-Scottish border country, and also to provide fighting men who could suppress the native Irish in Ireland.

The first major influx of Scots and English into Ulster had come in 1606 during the settlement of east Down

County Down

-Cities:*Belfast *Newry -Large towns:*Dundonald*Newtownards*Bangor-Medium towns:...

onto land cleared of native Irish by private landlords chartered by James. This process was accelerated with James's official plantation in 1609, and further augmented during the subsequent Irish Confederate Wars

Irish Confederate Wars

This article is concerned with the military history of Ireland from 1641-53. For the political context of this conflict, see Confederate Ireland....

. The first of the Stuart

House of Stuart

The House of Stuart is a European royal house. Founded by Robert II of Scotland, the Stewarts first became monarchs of the Kingdom of Scotland during the late 14th century, and subsequently held the position of the Kings of Great Britain and Ireland...

Kingdoms to collapse into civil war was Ireland, where, prompted in part by the anti-Catholic rhetoric of the Covenanters, Irish Catholics launched a rebellion in October

Irish Rebellion of 1641

The Irish Rebellion of 1641 began as an attempted coup d'état by Irish Catholic gentry, who tried to seize control of the English administration in Ireland to force concessions for the Catholics living under English rule...

. In reaction to the proposal by Charles I

Charles I of England

Charles I was King of England, King of Scotland, and King of Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. Charles engaged in a struggle for power with the Parliament of England, attempting to obtain royal revenue whilst Parliament sought to curb his Royal prerogative which Charles...

and Thomas Wentworth to raise an army manned by Irish Catholics to put down the Covenanter movement in Scotland, the Parliament of Scotland

Parliament of Scotland

The Parliament of Scotland, officially the Estates of Parliament, was the legislature of the Kingdom of Scotland. The unicameral parliament of Scotland is first found on record during the early 13th century, with the first meeting for which a primary source survives at...

had threatened to invade Ireland in order to achieve "the extirpation of Popery out of Ireland" (according to the interpretation of Richard Bellings

Richard Bellings

Richard Bellings was a lawyer and political figure in 17th century Ireland and in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. He is best known for his participation in Confederate Ireland, a short-lived independent Irish state, in which he served on the governing body called the Supreme Council...

, a leading Irish politician of the time). The fear this caused in Ireland unleashed a wave of massacres against Protestant English and Scottish settlers, mostly in Ulster, once the rebellion had broken out. All sides displayed extreme cruelty in this phase of the war. Around 4000 settlers were massacred and a further 12,000 may have died of privation after being driven from their homes. In one notorious incident, the Protestant inhabitants of Portadown

Portadown Massacre

The Portadown Massacre took place in November 1641 at what is now Portadown, County Armagh. Up to 100 mostly English Protestants were killed in the River Bann by a group of armed Irishmen...

were taken captive and then massacred on the bridge in the town. The settlers responded in kind, as did the British-controlled government in Dublin, with attacks on the Irish civilian population. Massacres of native civilians occurred at Rathlin Island

Rathlin Island

Rathlin Island is an island off the coast of County Antrim, and is the northernmost point of Northern Ireland. Rathlin is the only inhabited offshore island in Northern Ireland, with a rising population of now just over 100 people, and is the most northerly inhabited island off the Irish coast...

and elsewhere. In early 1642, the Covenanters sent an army to Ulster

Ulster

Ulster is one of the four provinces of Ireland, located in the north of the island. In ancient Ireland, it was one of the fifths ruled by a "king of over-kings" . Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the ancient kingdoms were shired into a number of counties for administrative and judicial...

to defend the Scottish settlers there from the Irish rebels who had attacked them after the outbreak of the rebellion. The original intention of the Scottish army was to re-conquer Ireland, but due to logistical and supply problems, it was never in a position to advance far beyond its base in eastern Ulster. The Covenanter force remained in Ireland until the end of the civil wars but was confined to its garrison around Carrickfergus

Carrickfergus

Carrickfergus , known locally and colloquially as "Carrick", is a large town in County Antrim, Northern Ireland. It is located on the north shore of Belfast Lough, from Belfast. The town had a population of 27,201 at the 2001 Census and takes its name from Fergus Mór mac Eirc, the 6th century king...

after its defeat by the native Ulster Army at the Battle of Benburb

Battle of Benburb

The Battle of Benburb took place in 1646 during the Irish Confederate Wars, the Irish theatre of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. It was fought between the forces of Confederate Ireland under Owen Roe O'Neill and a Scottish Covenanter and Anglo-Irish army under Robert Monro...

in 1646. After the war was over, many of the soldiers settled permanently in Ulster. Another major influx of Scots into Ulster occurred in the 1690s, when tens of thousands of people fled a famine in Scotland to come to Ireland.

Just a few generations after arriving in Ireland, considerable numbers of Ulster-Scots emigrated to the North American colonies of Great Britain

British America

For American people of British descent, see British American.British America is the anachronistic term used to refer to the territories under the control of the Crown or Parliament in present day North America , Central America, the Caribbean, and Guyana...

throughout the 18th century (between 1717 and 1770 alone, about 250,000 settled in what would become the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

). According to Kerby Miller, Emigrants and Exiles: Ireland and the Irish Exodus to North America (1988), Protestants

Protestantism

Protestantism is one of the three major groupings within Christianity. It is a movement that began in Germany in the early 16th century as a reaction against medieval Roman Catholic doctrines and practices, especially in regards to salvation, justification, and ecclesiology.The doctrines of the...

were one-third the population of Ireland, but three-quarters of all emigrants leaving from 1700 to 1776; 70% of these Protestants were Presbyterians. Other factors contributing to the mass exodus of Ulster Scots to America during the 18th century were a series of drought

Drought

A drought is an extended period of months or years when a region notes a deficiency in its water supply. Generally, this occurs when a region receives consistently below average precipitation. It can have a substantial impact on the ecosystem and agriculture of the affected region...

s and rising rents imposed by often absentee

Absentee landlord

Absentee landlord is an economic term for a person who owns and rents out a profit-earning property, but does not live within the property's local economic region. This practice is problematic for that region because absentee landlords drain local wealth into their home country, particularly that...

English and/or Anglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish was a term used primarily in the 19th and early 20th centuries to identify a privileged social class in Ireland, whose members were the descendants and successors of the Protestant Ascendancy, mostly belonging to the Church of Ireland, which was the established church of Ireland until...

landlords.

During the course of the 17th century, the number of settlers belonging to Calvinist dissenting sects, including Scottish

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

and Northumbria

Northumbria

Northumbria was a medieval kingdom of the Angles, in what is now Northern England and South-East Scotland, becoming subsequently an earldom in a united Anglo-Saxon kingdom of England. The name reflects the approximate southern limit to the kingdom's territory, the Humber Estuary.Northumbria was...

n Presbyterians

Presbyterianism

Presbyterianism refers to a number of Christian churches adhering to the Calvinist theological tradition within Protestantism, which are organized according to a characteristic Presbyterian polity. Presbyterian theology typically emphasizes the sovereignty of God, the authority of the Scriptures,...

, English Baptists, French and Flemish Huguenot

Huguenot

The Huguenots were members of the Protestant Reformed Church of France during the 16th and 17th centuries. Since the 17th century, people who formerly would have been called Huguenots have instead simply been called French Protestants, a title suggested by their German co-religionists, the...

s, and German Palatines

German Palatines

The German Palatines were natives of the Electoral Palatinate region of Germany, although a few had come to Germany from Switzerland, the Alsace, and probably other parts of Europe. Towards the end of the 17th century and into the 18th, the wealthy region was repeatedly invaded by French troops,...

, became the majority among the Protestant settlers in the province of Ulster. However, the Presbyterians and other dissenters, along with Catholics, were not members of the established church and were consequently legally disadvantaged by the Penal Laws

Penal Laws (Ireland)

The term Penal Laws in Ireland were a series of laws imposed under English and later British rule that sought to discriminate against Roman Catholics and Protestant dissenters in favour of members of the established Church of Ireland....

, which gave full rights only to members of the Church of England

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

/Church of Ireland

Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland is an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. The church operates in all parts of Ireland and is the second largest religious body on the island after the Roman Catholic Church...

. Those members of the state church

State church

State churches are organizational bodies within a Christian denomination which are given official status or operated by a state.State churches are not necessarily national churches in the ethnic sense of the term, but the two concepts may overlap in the case of a nation state where the state...

were often absentee landlord

Absentee landlord

Absentee landlord is an economic term for a person who owns and rents out a profit-earning property, but does not live within the property's local economic region. This practice is problematic for that region because absentee landlords drain local wealth into their home country, particularly that...

s and the descendants of English title-holding

Peerage

The Peerage is a legal system of largely hereditary titles in the United Kingdom, which constitute the ranks of British nobility and is part of the British honours system...

settlers. For this reason, up until the 19th century, and despite their common fear of the dispossessed Catholic native Irish, there was considerable disharmony between the Presbyterians

Presbyterianism

Presbyterianism refers to a number of Christian churches adhering to the Calvinist theological tradition within Protestantism, which are organized according to a characteristic Presbyterian polity. Presbyterian theology typically emphasizes the sovereignty of God, the authority of the Scriptures,...

and the Protestant Ascendancy

Protestant Ascendancy

The Protestant Ascendancy, usually known in Ireland simply as the Ascendancy, is a phrase used when referring to the political, economic, and social domination of Ireland by a minority of great landowners, Protestant clergy, and professionals, all members of the Established Church during the 17th...

in Ulster. As a result of this many Ulster-Scots, along with Catholic native Irish, ignored religious differences to join the United Irishmen and participate in the Irish Rebellion of 1798

Irish Rebellion of 1798

The Irish Rebellion of 1798 , also known as the United Irishmen Rebellion , was an uprising in 1798, lasting several months, against British rule in Ireland...

, in support of Age of Enlightenment

Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment was an elite cultural movement of intellectuals in 18th century Europe that sought to mobilize the power of reason in order to reform society and advance knowledge. It promoted intellectual interchange and opposed intolerance and abuses in church and state...

-inspired egalitarian

Egalitarianism

Egalitarianism is a trend of thought that favors equality of some sort among moral agents, whether persons or animals. Emphasis is placed upon the fact that equality contains the idea of equity of quality...

and republican

Republicanism

Republicanism is the ideology of governing a nation as a republic, where the head of state is appointed by means other than heredity, often elections. The exact meaning of republicanism varies depending on the cultural and historical context...

goals.

American settlement

Scholarly estimate is that over 200,000 Scotch-Irish migrated to the Americas between 1717 and 1775. As a late arriving group, they found that land in the coastal areas of the British colonies was either already owned or too expensive, so they quickly left for the hill country where land could be had cheaply. Here they lived on the frontiers of America. Early frontier life was extremely challenging, but poverty and hardship were familiar to them. The term hillbillyHillbilly

Hillbilly is a term referring to certain people who dwell in rural, mountainous areas of the United States, primarily Appalachia but also the Ozarks. Owing to its strongly stereotypical connotations, the term is frequently considered derogatory, and so is usually offensive to those Americans of...

has often been applied to their descendants in the mountains, carrying connotations of poverty, backwardness and violence; this word having its origins in Scotland and Ireland.

The first trickle of Scotch-Irish settlers arrived in New England. Valued for their fighting prowess as well as for their Protestant dogma, they were invited by Cotton Mather

Cotton Mather

Cotton Mather, FRS was a socially and politically influential New England Puritan minister, prolific author and pamphleteer; he is often remembered for his role in the Salem witch trials...

and other leaders to come over to help settle and secure the frontier. In this capacity, many of the first permanent settlements in Maine

Maine

Maine is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States, bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the east and south, New Hampshire to the west, and the Canadian provinces of Quebec to the northwest and New Brunswick to the northeast. Maine is both the northernmost and easternmost...

and New Hampshire

New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States of America. The state was named after the southern English county of Hampshire. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Atlantic Ocean to the east, and the Canadian...

, especially after 1718, were Scotch-Irish and many place names as well as the character of Northern New Englanders reflect this fact. The Scotch-Irish brought the potato with them from Ireland (although the potato originated in South America, it was not known in North America until brought over from Europe). In Maine it became a staple crop as well as an economic base.

From 1717 to the next thirty or so years, the primary points of entry for the Ulster immigrants were Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and New Castle, Delaware. The Scotch-Irish radiated westward across the Alleghenies

Allegheny Mountains

The Allegheny Mountain Range , also spelled Alleghany, Allegany and, informally, the Alleghenies, is part of the vast Appalachian Mountain Range of the eastern United States and Canada...

, as well as into Virginia

Virginia

The Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there...

, North Carolina

North Carolina

North Carolina is a state located in the southeastern United States. The state borders South Carolina and Georgia to the south, Tennessee to the west and Virginia to the north. North Carolina contains 100 counties. Its capital is Raleigh, and its largest city is Charlotte...

, South Carolina

South Carolina

South Carolina is a state in the Deep South of the United States that borders Georgia to the south, North Carolina to the north, and the Atlantic Ocean to the east. Originally part of the Province of Carolina, the Province of South Carolina was one of the 13 colonies that declared independence...

, Georgia

Georgia (U.S. state)

Georgia is a state located in the southeastern United States. It was established in 1732, the last of the original Thirteen Colonies. The state is named after King George II of Great Britain. Georgia was the fourth state to ratify the United States Constitution, on January 2, 1788...

, Kentucky

Kentucky

The Commonwealth of Kentucky is a state located in the East Central United States of America. As classified by the United States Census Bureau, Kentucky is a Southern state, more specifically in the East South Central region. Kentucky is one of four U.S. states constituted as a commonwealth...

, and Tennessee

Tennessee

Tennessee is a U.S. state located in the Southeastern United States. It has a population of 6,346,105, making it the nation's 17th-largest state by population, and covers , making it the 36th-largest by total land area...

. The typical migration involved small networks of related families who settled together, worshipped together, and intermarried, avoiding outsiders.

Pennsylvania and Virginia

Most Scotch-Irish headed for Pennsylvania, with its good lands, moderate climate, and liberal laws. By 1750, the Scotch-Irish were about a fourth of the population, rising to about a third by the 1770s. Without much cash, they moved to free lands on the frontier, becoming the typical western "squatters", the frontier guard of the colony, and what the historian Frederick Jackson TurnerFrederick Jackson Turner

Frederick Jackson Turner was an American historian in the early 20th century. He is best known for his essay "The Significance of the Frontier in American History", whose ideas are referred to as the Frontier Thesis. He is also known for his theories of geographical sectionalism...

described as "the cutting-edge of the frontier."

The Scotch-Irish moved up the Delaware River to Bucks County, and then up the Susquehanna and Cumberland valleys, finding flat lands along the rivers and creeks to set up their log cabins, their grist mills, and their Presbyterian churches. Chester, Lancaster, and Dauphin counties became their strongholds, and they built towns such as Chambersburg, Gettysburg, Carlisle, and York; the next generation moved into western Pennsylvania. With large numbers of children who needed their own inexpensive farms, the Scotch-Irish avoided areas already settled by Germans and Quakers and moved south, down the Shenandoah Valley

Shenandoah Valley

The Shenandoah Valley is both a geographic valley and cultural region of western Virginia and West Virginia in the United States. The valley is bounded to the east by the Blue Ridge Mountains, to the west by the eastern front of the Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians , to the north by the Potomac River...

, and through the Blue Ridge Mountains into Virginia. These migrants followed the Great Wagon Road

Great Wagon Road

The Great Wagon Road was a colonial American improved trail transiting the Great Appalachian Valley from Pennsylvania to North Carolina, and from there to Georgia....

from Lancaster, through Gettysburg, and down through Staunton, Virginia, to Big Lick (now Roanoke), Virginia. Here the pathway split, with the Wilderness Road

Wilderness Road

The Wilderness Road was the principal route used by settlers for more than fifty years to reach Kentucky from the East. In 1775, Daniel Boone blazed a trail for the Transylvania Company from Fort Chiswell in Virginia through the Cumberland Gap into central Kentucky. It was later lengthened,...

taking settlers west into Tennessee and Kentucky, while the main road continued south into the Carolinas.

Conflict with Native Americans

Because the Scotch-Irish settled the frontier of Pennsylvania and Virginia, they were in the midst of the French and Indian WarFrench and Indian War

The French and Indian War is the common American name for the war between Great Britain and France in North America from 1754 to 1763. In 1756, the war erupted into the world-wide conflict known as the Seven Years' War and thus came to be regarded as the North American theater of that war...

and Pontiac’s Rebellion that followed. The Scotch-Irish were frequently in conflict with the Indian tribes who lived on the other side of the frontier; indeed, they did most of the Indian fighting on the American frontier from New Hampshire to the Carolinas. The Irish and Scots also became the middlemen who handled trade and negotiations between the Indian tribes and the colonial governments.

Especially in Pennsylvania, whose pacifist Quaker leaders had made no provision for a militia, Scotch-Irish settlements were frequently destroyed and the settlers killed, captured or forced to flee after attacks by Native Americans from tribes of the Delaware (Lenape

Lenape

The Lenape are an Algonquian group of Native Americans of the Northeastern Woodlands. They are also called Delaware Indians. As a result of the American Revolutionary War and later Indian removals from the eastern United States, today the main groups live in Canada, where they are enrolled in the...

), Shawnee, Seneca, and others of western Pennsylvania and the Ohio country. Indian attacks were taking place within 60 miles of Philadelphia, and in July 1763, the Pennsylvania Assembly authorized a 700-strong militia to be raised, to be used only for defensive actions. Formed into two units of rangers, the Cumberland Boys and the Paxton Boys

Paxton Boys

The Paxton Boys were a vigilante group who murdered 20 Susquehannock in events collectively called the Conestoga Massacre. Scots-Irish frontiersmen from central Pennsylvania along the Susquehanna River formed a vigilante group to retaliate against local American Indians in the aftermath of the...

, the militia soon exceeded their defensive mandate and began offensive forays against Lenape villages in western Pennsylvania. After attacking Delaware villages in the upper Susquehanna

Susquehanna River

The Susquehanna River is a river located in the northeastern United States. At long, it is the longest river on the American east coast that drains into the Atlantic Ocean, and with its watershed it is the 16th largest river in the United States, and the longest river in the continental United...

valley, the militia leaders received information, which they believed credible, that “hostile” tribes were receiving weapons and ammunition from the “friendly” tribe of Conestogas settled in Lancaster County, who were under the protection of the Pennsylvania Assembly. On 14 December 1763, about fifty Paxton Boys rode to Conestogatown, near Millersville, PA, and murdered six Conestogas. Governor John Penn

John Penn (governor)

John Penn was the last governor of colonial Pennsylvania, serving in that office from 1763 to 1771 and from 1773 to 1776...

placed the remaining fourteen Conestogas in protective custody in the Lancaster

Lancaster, Pennsylvania

Lancaster is a city in the south-central part of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. It is the county seat of Lancaster County and one of the older inland cities in the United States, . With a population of 59,322, it ranks eighth in population among Pennsylvania's cities...

workhouse, but the Paxton Boys broke in, killing and mutilating all fourteen on 27 December 1763. Following this, about 400 backcountry settlers, primarily Scotch-Irish, marched on Philadelphia demanding better military protection for their settlements, and pardons for the Paxton Boys. Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin

Dr. Benjamin Franklin was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. A noted polymath, Franklin was a leading author, printer, political theorist, politician, postmaster, scientist, musician, inventor, satirist, civic activist, statesman, and diplomat...

led the politicians who negotiated a settlement with the Paxton leaders, after which they returned home.

American Revolution

The United States Declaration of IndependenceUnited States Declaration of Independence

The Declaration of Independence was a statement adopted by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, which announced that the thirteen American colonies then at war with Great Britain regarded themselves as independent states, and no longer a part of the British Empire. John Adams put forth a...

contained fifty-six delegate signatures. Of the signers, eight were of Irish descent. Three signers, Matthew Thornton

Matthew Thornton

Matthew Thornton , was a signer of the United States Declaration of Independence as a representative of New Hampshire.- Background and Early Life :He was born in Ireland, the son of James Thornton and Elizabeth Malone...

, George Taylor

George Taylor

George Taylor may refer to:*George Taylor , soldier in Texas army, died in the Battle of the Alamo*George Taylor , see List of Sydney Swans players...

and James Smith were born in Ulster, the remaining five Irish Americans were the sons or grandsons of Irish immigrants: George Read

George Read

George Read is the name of:* George Read , lawyer, signer of Declaration of Independence and U.S. Senator from Delaware* George Read , politician and former leader of the Alberta Green Party...

, Thomas McKean

Thomas McKean

Thomas McKean was an American lawyer and politician from New Castle, in New Castle County, Delaware and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. During the American Revolution he was a delegate to the Continental Congress where he signed the United States Declaration of Independence and the Articles of...

, Thomas Lynch, Jr.

Thomas Lynch, Jr.

Thomas Lynch, Jr. was a signer of the United States Declaration of Independence as a representative of South Carolina; his father was unable to sign the Declaration of Independence because of illness.-Biography:...

, Edward Rutledge

Edward Rutledge

Edward Rutledge was an American politician and youngest signer of the United States Declaration of Independence. He later served as the 39th Governor of South Carolina.-Early years and career:...

and Charles Carroll

Charles Carroll of Carrollton

Charles Carroll of Carrollton was a wealthy Maryland planter and an early advocate of independence from Great Britain. He served as a delegate to the Continental Congress and later as United States Senator for Maryland...

, and at least McKean had Ulster heritage.

The Scotch-Irish were generally ardent supporters of American Independence from Britain in the 1770s. In Pennsylvania, Virginia, and most of the Carolinas, support for the revolution was "practically unanimous." One Hessian officer said, "Call this war by whatever name you may, only call it not an American rebellion; it is nothing more or less than a Scotch Irish Presbyterian rebellion." A British major general testified to the House of Commons that "half the rebel Continental Army were from Ireland". Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, with its large Scotch-Irish population, was to make the first declaration for independence from Britain in the Mecklenburg Declaration of 1775.

The Scotch-Irish "Overmountain Men

Overmountain Men

The Overmountain Men were American frontiersmen from west of the Appalachian Mountains who took part in the American Revolutionary War. While they were present at multiple engagements in the war's southern campaign, they are best known for their role in the American victory at the Battle of Kings...