Orange Institution

Encyclopedia

The Orange Institution (more commonly known as the Orange Order or Orange Lodge) is a Protestant fraternal organisation

based mainly in Northern Ireland

and Scotland

, though it has lodges throughout the Commonwealth

and United States

. The Institution was founded in 1796 near the village of Loughgall

in County Armagh

, Ireland. Its name is a tribute to Dutch

-born Protestant William of Orange

, who defeated the army of Catholic

James II

at the Battle of the Boyne

(1690).

Politically, the Orange Institution is strongly linked to unionism

. Critics have accused the Institution of being sectarian

, triumphalist

and supremacist

. Catholics, and those whose close relatives are Catholic, are banned from becoming members. Non-creedal and non-trinitarian

denominations (such as members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons

), Unitarians

and some branches of Quakers) are also ineligible for membership, although these denominations do not have large congregations where most Orange lodges are found.

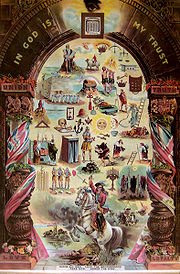

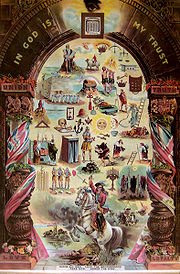

The Orange Institution commemorates William of Orange

The Orange Institution commemorates William of Orange

, the Dutch prince who became King of England, Scotland, and Ireland

in the Glorious Revolution

of 1688. In particular, the Institution remembers the victories of William III and his forces in Ireland in the early 1690s, especially the Battle of the Boyne.

(mostly Irish Catholic

s, but also some liberal Anglicans) and on the other were the so-called "Protestant Ascendancy

" and its supporters. In October 1791 the nationalist Society of United Irishmen was founded by liberal Protestants in Belfast

. Its leaders were mainly Presbyterians

. They called for a reform of the Irish Parliament

that would extend the vote to all Irish men (regardless of religion) and give Ireland greater independence from Britain.

Although the United Irishmen were trying to unite Catholics and Protestants behind their goal, northern County Armagh

was undergoing fierce sectarian

conflict. Catholics and Protestants set up rural "vigilante

" groups – on the Catholic side was the "Defenders

" and on the Protestant side was the "Peep-o'-Day Boys". In July 1795 a Reverend Devine had held a sermon at Drumcree Church

to commemorate the "Battle of the Boyne". In his History of Ireland Vol I (published in 1809), the historian Francis Plowden described the events that followed this sermon:

The Orange Order was founded after an incident known as the "Battle of the Diamond

", which happened two months after the Drumcree sermon. It took place on 21 September 1795 near Loughgall

, a few miles from Drumcree. It was a clash between Defenders and Peep-o'-Day Boys in which four to thirty (mostly un-armed) Defenders were killed. The Governor of Armagh, Lord Gosford, gave his opinion of the violence in County Armagh that followed the "battle" at a meeting of magistrates on 28 December 1795. He said:

and Robert Hugh Wallace

, have questioned this statement, saying whoever the Governor believed were the “lawless banditti” they could not have been Orangemen as there were no lodges in existence at the time of his speech. According to historian Jim Smyth:

The Order's three main founders were James Wilson

(founder of the Orange Boys), Daniel Winter and James Sloan

. The first Orange lodge established in nearby Dyan, County Tyrone

. Its first grand master was James Sloan of Loughgall, in whose inn the victory by the Peep-o'-Day Boys was celebrated. Like the Peep-o'-Day Boys, one of its goals was to hinder the efforts of Irish nationalist groups and uphold the "Protestant Ascendancy". The Orange Order's first ever marches were to celebrate the "Battle of the Boyne" and they took place on 12 July 1796 in Portadown

, Lurgan

and Waringstown

.

By the time the Orange Order formed, the United Irishmen (still led mainly by Protestants) had become a republican

group and sought an independent Irish republic that would "Unite Catholic, Protestant and Dissenter". United Irishmen activity was on the rise, and the government hoped to thwart it by backing the Orange Order from 1796 onward. Nationalist historians Thomas A. Jackson

and John Mitchel

argued that the government's goal was to hinder the United Irishmen by fomenting sectarianism

— it would create disunity and disorder under pretence of "passion for the Protestant religion". Mitchel wrote that the government invented and spread "fearful rumours of intended massacres of all the Protestant people by the Catholics". Historian Richard R Madden wrote that "efforts were made to infuse into the mind of the Protestant feelings of distrust to his Catholic fellow-countrymen". Thomas Knox

, British military commander in Ulster, wrote in August 1796 that "As for the Orangemen, we have rather a difficult card to play...we must to a certain degree uphold them, for with all their licentiousness, on them we must rely for the preservation of our lives and properties should critical times occur".

When the United Irishmen rebellion

broke out in 1798, Orangemen and ex-Peep-o'-Day Boys helped government forces in suppressing it. According to Ruth Dudley Edwards and two former grand masters, Orangemen were among the first to contribute to repair funds for Catholic property damaged in the violence surrounding the rebellion.

on 25 May 1816. According to the article, "A number of Orangemen with arms rushed into the church and fired upon the congregation". On 19 July 1823 the Unlawful Oaths Bill was passed, banning all oath-bound societies in Ireland. This included the Orange Order, which had to be dissolved and reconstituted. In 1825 a bill banning unlawful associations – largely directed at Daniel O'Connell

and his Catholic Association

, compelled the Orangemen once more to dissolve their association. When Westminster

granted Catholic Emancipation

in 1829, Irish Catholics were free at last to take seats as MPs and play a part in framing the laws of the land. The likelihood of Catholic members holding the balance of power in the Westminster Parliament further increased the alarm of Orangemen in Ireland, as to them it meant the possible revival of a Catholic-dominated Parliament controlled from Rome

, and an end to the Protestant Ascendancy. From this moment on, the Orange Order re-emerged in a new and even more militant form.

In 1845 the ban was lifted, but the famous Battle of Dolly's Brae between Orangemen and Ribbonmen in 1849 led to a ban on Orange marches which remained in place for several decades. This was eventually lifted after a campaign of disobedience led by William Johnston of Ballykilbeg.

's first Irish Home Rule Bill 1886, and was instrumental in the formation of the Ulster Unionist Party

(UUP). The strength of Protestant opposition to Irish self-government under possible Roman Catholic influence, especially in the Protestant-dominated province of Ulster

, eventually led to six Ulster counties remaining within the United Kingdom, as Northern Ireland

.

In the first decade of the twentieth century, the Order suffered a split when Thomas Sloane left the organisation to set up the Independent Orange Order

. Sloane had been suspended after running against a Unionist candidate on a pro-labour platform in an election in 1902.

and unionists in general, were inflexible in opposing the Bill. The Order helped to organise the 1912 Ulster Covenant

– a pledge to oppose Home Rule that was signed by up to 500,000 people. In 1911 some Orangemen began to arm themselves and train as a militia called the Ulster Volunteers. In 1913 the Ulster Unionist Council decided to bring these groups under central control, creating the Ulster Volunteer Force

, a militia dedicated to resisting Home Rule. There was a strong overlap between Orange Lodges and UVF units. A large shipment of rifles was imported from Germany to arm them in April 1914, in what became known as the Larne gun-running.

However, the crisis was interrupted by the outbreak of the World War I

in August 1914. This caused the Home Rule Bill to be suspended for the duration of the war. Many Orangemen served in the war with the 36th (Ulster) Division suffering heavy losses and commemorations of their sacrifice are still an important element of Orange ceremonies.

The Fourth Home Rule Act was passed as the Government of Ireland Act 1920

; the six north eastern counties of Ulster became Northern Ireland and the other twenty-six counties became Southern Ireland

. This self governing entity within the United Kingdom was confirmed in its status under the terms of the Anglo-Irish Treaty

of 1921, and in its borders by the Boundary Commission

agreement of 1925. Southern Ireland became first the Irish Free State

in 1922 and then in 1949 a republic under the name of "Ireland

".

The Orange Order had a central place in the new state of Northern Ireland. From 1921 to 1969, every Prime Minister of Northern Ireland

The Orange Order had a central place in the new state of Northern Ireland. From 1921 to 1969, every Prime Minister of Northern Ireland

was an Orangeman and member of the Ulster Unionist Party

(UUP); all but three Cabinet Ministers

were Orangemen; all but one unionist Senators

were Orangemen; and 87 of the 95 MPs who did not become Cabinet Ministers were Orangemen. James Craig

, the first Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, maintained always that Ulster was in effect Protestant and the symbol of its ruling forces was the Orange Order. In 1932, Prime Minister Craig maintained that "ours is a Protestant government and I am an Orangeman". Two years later he stated: "I have always said that I am an Orangeman first and a politician and a member of this parliament

afterwards…All I boast is that we have a Protestant Parliament and a Protestant State

".

At its peak in 1965, the Order's membership was around 70,000, which meant that roughly 1 in 5 adult Protestant males were members. Since 1965, it has lost a third of its membership, notably in Belfast and Derry. The Order's political influence suffered greatly when the Unionist-dominated Northern Ireland Parliament was prorogued in 1972.

After the outbreak of "The Troubles

" in 1969, the Grand Orange Lodge of Ireland encouraged Orangemen to join the Northern Ireland security forces—namely the Royal Ulster Constabulary

(RUC) and the British Army

's Ulster Defence Regiment

(UDR). The response from Orangemen was strong. Over 300 Orangemen were killed during the conflict, the vast majority of them members of the security forces. Some Orangemen also joined loyalist

paramilitaries

. During the conflict, the Order had a fractious relationship with loyalist paramilitaries, the Democratic Unionist Party

(DUP), the Independent Orange Order

and the Free Presbyterian Church

. The Order urged its members not to join these organisations, and it is only recently that some of these intra-Unionist breaches have been healed.

, when it marches to-and-from Drumcree Church

. It has marched this route since 1807, when the area was sparsely populated. However, today most of this route falls within the town's mainly-Catholic and nationalist quarter, which is densely populated. The residents have sought to re-route the parade away from this area, seeing it as "triumphalist

" and "supremacist

".

There have been intermittent violent clashes during the yearly parade since at least 1873. The dispute was intensified by "The Troubles". Before the 1990s, the most contentious part of the parade was the outward leg along Obins Street. When the parade was banned from Obins Street in 1986, the focus shifted to the parade's return leg along Garvaghy Road.

In 1995, the dispute drew worldwide media attention as it led to widespread protest

s and riot

ing throughout Northern Ireland. This wave of violence began when Catholic and nationalist protestors prevented the march from continuing along Garvaghy Road. This pattern was repeated every July for the next five years. During that time the dispute led to the deaths of at least five civilians and prompted massive police

and army

operations. Since 1998 the parade has been banned from most of the nationalist area, and the violence has subsided. However, regular moves to get the two sides into face-to-face talks have failed.

" and the principles of the Reformation

. As such the Order only accepts those who confess a belief in a Protestant religion.

The Order considers the Fourth Commandment

to forbid Christians to work, or engage in non-religious activity generally, on Sundays, to be important. When the Twelfth of July falls on a Sunday the parades traditionally held on that date are held on the Monday instead. In March 2002 the Order threatened "to take every action necessary, regardless of the consequences" to prevent the Ballymena

Show being held on a Sunday. The County Antrim

Agricultural Association complied with the Order's wishes.

Some evangelical groups have claimed that the Orange Order is still influenced by freemasonry

. Many Masonic traditions survive, such as the organisation of the Order into lodges. The Order has a system of degrees through which new members advance. These degrees are interactive plays with references to the Bible

. There is particular concern over the ritualism of higher degrees such as the Royal Arch Purple

and the Royal Black Institutions.

, especially in Northern Ireland

and in Scotland. This is a political ideology that supports the continued unity of the United Kingdom

. Unionism is thus opposed to, for example, the re-unification of Ireland

and Scottish independence

.

The Order, from its very inception, was an overtly political organisation. In 1905, when the Ulster Unionist Council (UUC) was formed, the Orange Order was entitled to send delegates to its meetings. The UUC was the decision-making body of the Ulster Unionist Party

(UUP). Between 1922 and 1972, the UUP was consistently the largest party in the Northern Ireland Parliament

. Due to its close links with the UUP, the Orange Order was able to exert great influence. The Order was the force behind the UUP no-confidence votes in reformist Prime Ministers

O'Neill (1969), Chichester-Clark (1969–71) and Faulkner (1972–74). At the outbreak of The Troubles

in 1969, the Order encouraged its members to join the Northern Ireland security forces, which were opposed by all Irish nationalist and republican parties. The Democratic Unionist Party

(DUP) attracted the most seats in an election for the first time in 2003. DUP leader Ian Paisley

, who was not a member of the Orange Order, maintained a bitter campaign of conflict with the Order since 1951, when the Order banned members of Paisley's Free Presbyterian Church

from acting as Orange chaplains and openly endorsed the UUP against the DUP. Recently, however, Orangemen have begun voting for the DUP in large numbers due to their opposition to the Good Friday Agreement. Relations between the DUP and Order have healed greatly since 2001, and there are now a number of high profile Orangemen who are DUP MPs and strategists.

In December 2009, the Orange Order held secret talks with Northern Ireland's two main unionist parties – the DUP and UUP. The main goal of these talks was to foster greater unity between the two parties, in the run-up to the May 2010 general election. Sinn Féin's Alex Maskey

said that the talks exposed the Order as a "very political organisation". Shortly after the election, Grand Master Robert Saulters called for a "single unionist party" to maintain the union. He said that the Order has members "who represent all the many shades of unionism" and warned, "we will continue to dilute the union if we fight and bicker among ourselves".

In the October 2010 issue of The Orange Standard, Grand Master Robert Saulters accused 'dissident' Irish republican

paramilitaries of being "fancy names" for the "Roman Catholic IRA". SDLP

MLA John Dallat

asked Justice Minister

David Ford

to find if Saulters had broken the hate speech

laws. He said: "Linking the Catholic community or indeed any community to terror groups is inciting weak-minded people to hatred, and surely history tells us what that has led to in the past".

In 2011 survey of 1,500 Orangemen throughout Northern Ireland, over 60% believed that "most Catholics are IRA sympathizers".

form a large part of Orange culture. Most Orange lodges hold an annual parade from their Orange hall to a local church. The denomination of the church is quite often rotated, depending on local demographics.

The highlights of the Orange year are the parades leading up to the celebrations on the Twelfth of July. The Twelfth, however, remains in places a deeply divisive issue, not least because of the triumphalism, anti-Catholicism and anti-nationalism of the Orange Order. In recent years, most Orange parades have passed peacefully.

As of 2007, Grand Lodge of Ireland policy remained non-recognition of the Parades Commission

, which it sees as explicitly founded to target Protestant parades since Protestants parade at ten times the rate of Catholics. Grand Lodge is, however, divided on the issue of working with the Parades Commission. 40% of Grand Lodge delegates oppose official policy while 60% are in favour. Most of those opposed to Grand Lodge policy are from areas facing parade restrictions like Portadown District, Bellaghy, Derry City and Lower Ormeau.

In a 2011 survey of Orangemen throughout Northern Ireland, 58% said they should be allowed to march through nationalist areas with no restrictions; 20% said they should negotiate with residents first.

Monthly meetings are held in Orange halls. Orange halls on both sides of the Irish border often function as community halls for Protestants and sometimes those of other faiths, though this was more common in the past. The halls quite often host community groups such as credit union

Monthly meetings are held in Orange halls. Orange halls on both sides of the Irish border often function as community halls for Protestants and sometimes those of other faiths, though this was more common in the past. The halls quite often host community groups such as credit union

s, local marching bands, Ulster-Scots

and other cultural groups as well as religious missions and Unionist political parties.

Of the approximately 700 Orange halls in Ireland

, 282 have been targeted by arsonists since the beginning of the Troubles

in 1968. Paul Butler

, a prominent member of Sinn Féin

, has claimed the arson is a "campaign against properties belonging to the Orange Order and other loyal institutions" by nationalists. On one occasion a member of Sinn Féin's youth wing (Ógra Shinn Féin

) was hospitalised after falling off the roof of an Orange hall. In a number of cases halls have been severely damaged or completely destroyed by arson, while others have been damaged by paint bombings, graffiti and other vandalism. The Order claims that there is considerable evidence of an organised campaign of sectarian vandalism by republicans. Grand Secretary Drew Nelson

claims that a statistical analysis shows that this campaign emerged in the last years of the 1980s and continues to the present.

with those of the Northern Ireland Office

. In addition, historical articles are often published in the Order's newspaper the Orange Standard and the Twelfth souvenir booklet. While William is the most frequent subject, other topics have included the Battle of the Somme (particularly the 36th (Ulster) Division's role in it), Saint Patrick

(who the Order argues was not Roman Catholic), and the Protestant Reformation

.

There are at least two Orange Lodges in Northern Ireland which represent the heritage and religious ethos of St Patrick. The best known of which is the Cross of Saint Patrick LOL (Loyal Orange lodge) 688, instituted in 1968 for the purpose of (re)claiming the heritage of St Patrick. The lodge has had several well known members, including Rev Robert Bradford MP who was the lodge chaplain who himself was killed by the Provisional IRA, the late Ernest Baird. Today Nelson McCausland MLA and Gordon Lucy, Director of the Ulster Society are the more prominent members within the lodge membership. In the 1970s there was also a Belfast lodge called Oidhreacht Éireann (Ireland's Heritage) LOL 1303, which argued that the Irish language

and Gaelic culture were not the exclusive property of Catholics or republicans.

The Order has been prominent in commemorating Ulster's war dead, particularly Orangemen and particularly those who died in the Battle of the Somme. There are numerous parades on and around 1 July in commemoration of the Somme, although the war memorial aspect is more obvious in some parades than others. There are several memorial lodges, and a number of banners which depict the Battle of the Somme, war memorials, or other commemorative images. In the grounds of the Ulster Tower Thiepval

The Order has been prominent in commemorating Ulster's war dead, particularly Orangemen and particularly those who died in the Battle of the Somme. There are numerous parades on and around 1 July in commemoration of the Somme, although the war memorial aspect is more obvious in some parades than others. There are several memorial lodges, and a number of banners which depict the Battle of the Somme, war memorials, or other commemorative images. In the grounds of the Ulster Tower Thiepval

, which commemorates the men of the Ulster Division who died in the Battle of the Somme, a smaller monument pays homage to the Orangemen who died in the war.

The Orange Order's view of history is usually not inaccurate, but could be criticised as outdated. It is reminiscent of the nineteenth century English historian Thomas Babington Macaulay, who argued that the Glorious Revolution

which brought William into power was a major turning point in British and world history. Macaulay's interpretation was very influential but has come under sustained criticism in recent decades.

Orange historiography tends also to be strongly biased in favour of William and against James, painting the former as an ideal ruler and the latter as a bigoted tyrant. It should be noted that few professional historians have a positive opinion of James, although most are also critical of William.

William was supported by the Pope in his campaigns against James' backer Louis XIV of France

, and this fact is sometimes left out of Orange histories. However it appears in others.

Occasionally the Order and the more fundamentalist Independent Order publishes historical arguments based more on religion than on history. British Israelism

, which claims that the British people are descended from the Israelites and that Queen Elizabeth II is a direct descendant of the Biblical King David, has from time to time been advanced in Orange publications.

, either by carrying paramilitary flags or having paramilitary names and emblems on their banners.

The banner of Old Boyne Island Heroes Orange lodge bears the names of John Bingham

and Shankill Butcher Robert Bates

, who were both members. Another Shankill Butcher, Eddie McIlwaine, was pictured taking part in an Orange parade in 2003 with a bannerette of dead UVF volunteer Brian Robinson

(who himself was an Orangeman).

Other prominent loyalist terrorists who were also members of the Orange Order included Gusty Spence

, Robert Bates

, John Bingham

, Richard Jameson

, Billy McCaughey

, Robert McConnell

and William Marchant

.

On 12 July 1972, at least fifty members of the Ulster Defence Association

(UDA) escorted an Orange march into the Catholic area of Portadown. The UDA members were dressed in paramilitary uniforms and saluted the Orangemen as they passed. That year, Orangemen formed a paramilitary group called the Orange Volunteers. This group "bombed a pub in Belfast in 1973 but otherwise did little illegal other than collect the considerable bodies of arms found in Belfast Orange Halls".

In the early years of The Troubles, the Order's Grand Secretary in Scotland trawled Orange lodges for volunteers to "go to Ulster to fight". Thousands are alleged to have "answered the call", although the UVF said it "did not yet need them". In 1976, senior Orangemen in Scotland tried to expel leading UDA member Roddy MacDonald after he said on television that he "would be happy to buy arms and ship them to Ulster". However, his expulsion was blocked by 300 delegates at a special disciplinary hearing.

Portadown Orangemen allowed known militants such as George Seawright

to take part in a 6 July 1986 march, contrary to a prior agreement. Seawright was a unionist politician and UVF member who had publicly proposed burning Catholics in ovens. As the march entered the town's Catholic district, the RUC seized Seawright and other known militants. The Orangemen attacked the officers with stones and other missiles.

During November 1999, in a raid on Stoneyford

Orange Hall, which the Irish Times has reported as a focal point for the Orange Volunteers

, police found military documents with the personal details of over 300 Irish republicans. This led to two Orangemen being convicted for possession of "documents likely to be of use to terrorists", possession of an automatic rifle, and membership in the outlawed Orange Volunteers

. Their Orange lodge refused to expel them.

In 2004, police found a weapons stash at the home of an Orangeman in Liverpool

. He and two other Orangemen were later jailed for possession of weapons and UVF membership. In 2006, a local Labour Party

Member of Parliament

, Louise Ellman

, called for the members to be expelled from the Order.

The Laws and Constitutions of the Loyal Orange Institution of Scotland of 1986 state, "No ex-Roman Catholic will be admitted into the Institution unless he is a Communicant in a Protestant Church for a reasonable period." Likewise, the "Constitution, Laws and Ordinances of the Loyal Orange Institution of Ireland" (1967) state, "No person who at any time has been a Roman Catholic … shall be admitted into the Institution, except after permission given by a vote of seventy five per cent of the members present founded on testimonials of good character …" In the 19th century, Rev. Mortimer O'Sullivan

, a converted Roman Catholic, was a Grand Chaplain of the Orange Order in Ireland.

In the 1950s, Scotland also had a former Catholic as a Grand Chaplain, the Rev. William McDermott.

The Grand Lodge of Ireland has 373 members. As a result, much of the real power in the Order resides in the Central Committee of the Grand Lodge, which is made up of three members from each of the six counties of Northern Ireland (Down, Antrim, Armagh, Londonderry, Tyrone and Fermanagh) as well as the two other County Lodges in Northern Ireland, the City of Belfast Grand Lodge and the City of Derry Grand Orange Lodge, two each from the remaining Ulster counties (Cavan, Donegal and Monaghan), one from Leitrim, and 19 others. There are other committees of the Grand Lodge, including rules revision, finance, and education.

Despite this hierarchy, private lodges are basically autonomous as long as they generally obey the rules of the Institution. Breaking these can lead to suspension of the lodge's warrant – essentially the dissolution of the lodge – by the Grand Lodge, but this rarely occurs. Private lodges may disobey policies laid down by senior lodges without consequence. For example, several lodges have failed to expel members convicted of murder despite a rule stating that anyone convicted of a serious crime should be expelled, and Portadown

lodges have negotiated with the Parades Commission

in defiance of Grand Lodge policy that the Commission should not be acknowledged.

Private lodges wishing to change Orange Order rules or policy can submit a resolution to their district lodge, which may submit it upwards until it eventually reaches the Grand Lodge.

. The women's order is parallel to the male order, and participates in its parades as much as the males apart from 'all male' parades and 'all ladies' parades respectively. The contribution of women to the Orange Order is recognised in the song "Ladies Orange Lodges O!".

began regularly speaking at Independent meetings, although he is not and has never been a member. As a result the Independent Institution has become associated with Paisley and his Free Presbyterian Church of Ulster

and Democratic Unionist Party

. Recently the relationship between the two Orange Institutions has improved, with joint church services being held. Some people believe that this will ultimately result in a healing of the split which led to the Independent Orange Institution breaking away from the mainstream Order. Like the main Order, the Independent Institution parades and holds meetings on the Twelfth of July. It is based mainly in County Antrim

.

and further abroad. It is headed by the Imperial Grand Orange Council. It has the power to arbitrate in disputes between Grand Lodges, and in internal disputes when invited. The Council represents the autonomous Grand Lodges of Ireland

, Scotland

, England

, Canada

, Australia

, New Zealand

, the United States

, Ghana

, Togo

, and Wales

.

Famous Orangemen have included Dr Thomas Barnardo, who joined the Order in Dublin, William Massey

, who was Prime Minister of New Zealand, Harry Ferguson

, inventor of the Ferguson tractor, and Earl Alexander, the Second World War general.

, where it was established in 1830. Most early members were from Ireland, but later many English, Scots, Italians and other Protestant Europeans joined the Order, as well as Mohawk Native Americans. Toronto was the epicentre of Canadian Orangeism: most mayors were Orange until the 1950s, and Toronto Orangemen battled against Ottawa-driven initiatives like bilingualism and Catholic immigration. A third of the Ontario legislature was Orange in 1920, but in Newfoundland, the proportion has been as high as 50% at times. Indeed, between 1920 and 1960, 35% of adult male Protestant Newfoundlanders were Orangemen, as compared with just 20% in Northern Ireland and 5%–10% in Ontario in the same period.

In addition to Newfoundland and Ontario, the Orange Order played an important role in the frontier regions of Quebec, including the Gatineau- Pontiac region. The region’s earliest Protestant settlement occurred when fifteen families from County Tipperary settled in the valley in Carleton County after 1818. These families spread across the valley, settling towns near Shawville, Quebec. Despite these early Protestant migrants, it was only during the early 1820s that a larger wave of Irish migrants, many of them Protestants, came to the Ottawa valley region. Orangism developed throughout the region’s Protestant communities, including Bristol, Lachute- Brownsburg, Shawville and Quyon. After further Protestant settlement throughout the 1830s and 40s, the Pontiac region's Orange Lodges developed into the largest rural contingent of Orangism in the Province. The Orange Lodges were seen as community cultural centres, as they hosted numerous dances, events, parades, and even the teaching of step dancing. Orange Parades still occur in the Pontiac-Gatineau- Ottawa Valley area; however, every community no longer hosts a parade. Now one larger parade is hosted by a different town every year.

The Toronto Twelfth is North America's oldest consecutive annual parade.

The Orange Order reached England in 1807, spread by soldiers returning to the Manchester

The Orange Order reached England in 1807, spread by soldiers returning to the Manchester

area from service in Ireland. Since then, the English branch of the Order has generally been allied with the Conservative and Unionist Party

. From 1909 to 1974, however, it was also associated with the Liverpool Protestant Party

.

The Orange Order in England is strongest in Liverpool

including Toxteth

and Garston. Its presence in Liverpool dates to at least 1819, when the first parade was held to mark the anniversary of the Battle of the Boyne, on 12 July.

The Orange Order in Liverpool holds its annual Twelfth parade in Southport

, a seaside town north of Liverpool. The Institution also holds a Juniors parade there on Whit Monday

. The Black Institution holds its Southport parade on the first Saturday in August.

The parades in Southport have attracted controversy in recent times, with some Southport locals criticising the marches due to the disruption that they cause. Events that are staged in the town mean closure of the main street in the town centre, Lord Street

. Some businesses choose to stay shut on Lodge days after some trouble caused in the 1980s, however many pubs and the restaurant trade welcome the day and the revenue it brings – particularly on an otherwise quiet weekday.

Other parades are held in Liverpool on the Sunday prior to the Twelfth and on the Sunday after. These parades along with St Georges day; Reformation Sunday and Remembrance Sunday go to and from church. Other parades are held by individual Districts of the Province – in all approximately 30 parades a year.

New Zealand's first Orange lodge was founded in Auckland

New Zealand's first Orange lodge was founded in Auckland

in 1842, only two years after the country became part of the British Empire, by James Carlton Hill of County Wicklow

. The lodge initially had problems finding a place to meet, as several landlords were threatened by Irish Catholic immigrants for hosting it. The arrival of large numbers of British troops to fight the New Zealand land wars

of the 1860s provided a boost for New Zealand Orangeism, and in 1867 a North Island

Grand Lodge was formed. A decade later a South Island

Grand Lodge was formed, and the two merged in 1908.

From the 1870s the Order was involved in local and general elections, although Rory Sweetman argues that 'the longed-for Protestant block vote ultimately proved unobtainable'. Processions seem to have been unusual before the late 1870s: the Auckland lodges did not march until 1877 and in most places Orangemen celebrated the Twelfth

and November 5 with dinners and concerts. The emergence of Orange parades in New Zealand was probably due to a Catholic revival movement which took place around this time. Although some parades resulted in rioting, Sweetman argues that the Order and its right to march were broadly supported by most New Zealanders, although many felt uneasy about the emergence of sectarianism in the colony. From 1912 to 1925 New Zealand's most famous Orangeman, William Massey

, was Prime Minister. During World War I

Massey co-led a coalition government with Irish Catholic Joseph Ward

. Historian Geoffrey W. Rice maintains that Bill Massey’s Orange sympathies were assumed rather than demonstrated.

Te Ara: The Encyclopaedia of New Zealand argues that New Zealand Orangeism, along with other Protestant and anti-Catholic organisations, faded from the 1920s. The Order has certainly declined in visibility since that decade, although in 1994 it was still strong enough to host the Imperial Orange Council for its biennial meeting. However parades have ceased, and most New Zealanders are probably unaware of the Order's existence in their country. The New Zealand Order is unusual in having mixed-gender lodges, and at one point had a female Grand Master.

Before the partition of Ireland

the Order's headquarters were in Dublin, which at one stage had more than 300 private lodges. After partition the Order declined rapidly in the Republic of Ireland. The last 12 July parade in Dublin took place in 1937. The last Orange parade in the Republic of Ireland is at Rossnowlagh

, County Donegal

, an event which has been largely free from trouble and controversy. It is held on the Saturday before the Twelfth as the day is not a holiday in the Republic of Ireland. There are still Orange lodges in nine counties of the Republic of Ireland – counties Cavan

, Cork

, Donegal

, Dublin, Laois

, Leitrim

, Louth

, Monaghan

and Wicklow

, but most either do not parade or travel to other areas to do so.

In 2005, controversy was generated when the organisers of Cork's

St Patrick's Day parade invited representatives of the Orange Order to parade in the celebrations, part of the year-long celebration of Cork's position of European Capital of Culture

. The Order accepted the invitation and was to parade with their wives and children alongside Chinese

, Filipino

and Africa

n community groups in an event designed to recognise and celebrate cultural diversity. Subsequently, after consultation with An Garda Síochána, the Order's grand secretary, Drew Nelson

, said both his organisation and the parade organisers were disappointed that the Order would not be attending the festivities. He added that he welcomed the invitation and hoped the Order would be able to participate in the event next year. A Church of Ireland

clergyman, Rev. David Armstrong, spoke out against the invitation.

In February 2008 it was announced that the Orange Order was to be granted nearly €250,000 from the Department of Community, Rural and Gaeltacht Affairs

. The grant is intended to provide support for members in border areas and fund the repair of Orange halls, many of which have been subjected to vandalism.

The Grand Orange Lodge of Scotland is the largest Orange Lodge outside Northern Ireland. Most lodges are concentrated in west central Scotland around Glasgow

The Grand Orange Lodge of Scotland is the largest Orange Lodge outside Northern Ireland. Most lodges are concentrated in west central Scotland around Glasgow

, Motherwell

, and parts of Renfrew

and Ayr

. However, the Order is also very strong in West Lothian

, and, to a lesser extent East Lothian

. Lodges are also based in the North East of Scotland, the most northerly lodges are located in Aberdeen

, Alford

, Peterhead

and Inverness

. The orders presence in the North of Scotland can be located to the fishing industry

and importation of workers from Belfast

and Glasgow

to the north and north east and migration of fishermen in the opposite direction.

In 1881, fully three quarters of Orange lodge masters were born in Ireland and, when compared to Canada, Scottish Orangeism has been both smaller (no more than two percent of adult male Protestants in west central Scotland have ever been members) and more of an Ulster ethnic association which has been less attractive to the native Protestant population. The strongest predictor of Orange strength in a Scottish county for the period 1860–2001 is the proportion of Irish-Protestant descent in the county.

Scottish Orangeism's political influence crested between the wars, but was effectively nil thereafter as the Tory party at all levels began to move away from Protestant politics toward a more neo-liberal economic agenda.

In 2004 former Scottish Orange Order member Adam Ingram

sued MP George Galloway

for saying in his autobiography that Ingram had "played the flute in a sectarian, anti-Catholic, Protestant-supremacist Orange Order band". Judge Lord Kingarth

ruled that the phrase was 'fair comment

' on the Orange Order and that Ingram had been a member, although he had not played the flute.

The Grand Orange Lodge of Scotland has spoken out against Scottish independence

, and on 24 March 2007, a parade of 12,000 Orangemen and women marched through Edinburgh

's Royal Mile

to celebrate the Act of Union

.

By 1870, when there were about 930 Orange lodges in the Canadian province of Ontario, there were only 43 in the entire eastern United States. These few American lodges were founded by newly arriving Protestant Irish immigrants in coastal cities such as Philadelphia and New York. These ventures were short-lived and of limited political and social impact, although there were specific instances of violence involving Orangemen between Catholic and Protestant Irish immigrants, such as the Orange Riots in New York City in 1824, 1870 and 1871.

The first "Orange riot" on record was in 1824, in Abingdon, NY, resulting from a 12 July march. Several Orangemen were arrested and found guilty of inciting the riot. According to the State prosecutor in the court record, "the Orange celebration was until then unknown in the country". The immigrants involved were admonished: "In the United States the oppressed of all nations find an asylum, and all that is asked in return is that they become law-abiding citizens. Orangemen, Ribbonmen, and United Irishmen are alike unknown. They are all entitled to protection by the laws of the country."

The later Orange riots

of 1870 and 1871 killed nearly 70 people, and were fought out between Irish Protestant and Catholic immigrants. After this the activities of the Orange Order were banned for a time, the Order dissolved, and most members joined Masonic Orders. After 1871, there were no more riots between Irish Catholics and Protestants.

America offered a new beginning, and "...most descendents of the Ulster Presbyterians of the eighteenth century and even many new Protestant Irish immigrants turned their backs on all associations with Ireland and melted into the American Protestant mainstream."

There are currently two Orange Lodges in New York, one in Manhattan and the other in the Bronx.

has stated that in America, Orangeism also manifested itself in movements such as the Know Nothings and the Ku Klux Klan

and that it also proved useful to employers as a device for keeping Protestant and Catholic workers from uniting for better wages and conditions. In the Orders petition to the Northern Ireland Parades Commission in June 2002, on the Orders right to march, they cited American case law which had upheld the right to public demonstrations by both the Klan and the American Nazi Party.

The Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association

, identifying with the American civil rights movement, described them as 'Britain's Ku Klux Klan' who wrote Fionnbarra O Dochartaigh

Brian Dooley says it would be 'grossly inaccurate' to suggest that the Orange Order 'mirrored' the KKK, he notes that they did share obvious similarities, not least their hostility to Catholicism. Leaders of the Klan going by titles such as Grand Goblin or Imperial Wizard and the Order having less exotic titles as Worshipful Master. Dooley, citing Wyn Craig's history of the Klan notes that during the 1920s the Klan targeted Catholic Churches to fill an 'emotional need for a concrete, foreign-based enemy...the Pope', with these attacks providing a unifying force in support for the Klan among Protestant Churches.

US Congressman Donald M. Payne

, who according to John McGarry

is one of the most influential black politicians in Congress said in an article in the Sunday Times that 'there are many parallels between Catholics in and the situation the black community faced in the United States.' Payne would be present in July 2000, to observe the Orange Orders attempts to march through a nationalist area.

Initially unveiled with a competition for children to name their new mascot in November 2007 (it was nicknamed 'Sash Gordon

' by several parts of the British media); at the official unveiling of the character's name in February 2008, Orange Order education officer David Scott said Diamond Dan was meant to represent the true values of the Order: "...the kind of person who offers his seat on a crowded bus to an elderly lady. He won't drop litter and he will be keen on recycling". There were plans for a range of Diamond Dan merchandise designed to appeal to children.

There was however uproar when it was revealed in the middle of the 'Marching Season' that Diamond Dan was a repaint of illustrator Dan Bailey's well-known "Super Guy" character (often used by British computer magazines), and taken without his permission., leading to the LOL's character being lampooned as "Bootleg Billy".

Canada and United States:

•Pierre-Luc Bégin (2008). « Loyalisme et fanatisme », Petite histoire du mouvement orangiste canadien, Les Éditions du Québécois, 2008, 200 p. (ISBN 2923365224).

•Luc Bouvier, (2002). « Les sacrifiés de la bonne entente »

Histoire des francophones du Pontiac, Éditions de l’Action nationale.

Fraternity

A fraternity is a brotherhood, though the term usually connotes a distinct or formal organization. An organization referred to as a fraternity may be a:*Secret society*Chivalric order*Benefit society*Friendly society*Social club*Trade union...

based mainly in Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland is one of the four countries of the United Kingdom. Situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, it shares a border with the Republic of Ireland to the south and west...

and Scotland

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

, though it has lodges throughout the Commonwealth

Commonwealth of Nations

The Commonwealth of Nations, normally referred to as the Commonwealth and formerly known as the British Commonwealth, is an intergovernmental organisation of fifty-four independent member states...

and United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

. The Institution was founded in 1796 near the village of Loughgall

Loughgall

Loughgall is a small village and townland in County Armagh, Northern Ireland. In the 2001 Census it had a population of 285 people.Loughgall was named after a small nearby loch. The village is at the heart of the apple-growing industry and is surrounded by orchards. Along the village's main street...

in County Armagh

County Armagh

-History:Ancient Armagh was the territory of the Ulaid before the fourth century AD. It was ruled by the Red Branch, whose capital was Emain Macha near Armagh. The site, and subsequently the city, were named after the goddess Macha...

, Ireland. Its name is a tribute to Dutch

Netherlands

The Netherlands is a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, located mainly in North-West Europe and with several islands in the Caribbean. Mainland Netherlands borders the North Sea to the north and west, Belgium to the south, and Germany to the east, and shares maritime borders...

-born Protestant William of Orange

William III of England

William III & II was a sovereign Prince of Orange of the House of Orange-Nassau by birth. From 1672 he governed as Stadtholder William III of Orange over Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders, and Overijssel of the Dutch Republic. From 1689 he reigned as William III over England and Ireland...

, who defeated the army of Catholic

Catholic

The word catholic comes from the Greek phrase , meaning "on the whole," "according to the whole" or "in general", and is a combination of the Greek words meaning "about" and meaning "whole"...

James II

James II of England

James II & VII was King of England and King of Ireland as James II and King of Scotland as James VII, from 6 February 1685. He was the last Catholic monarch to reign over the Kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland...

at the Battle of the Boyne

Battle of the Boyne

The Battle of the Boyne was fought in 1690 between two rival claimants of the English, Scottish and Irish thronesthe Catholic King James and the Protestant King William across the River Boyne near Drogheda on the east coast of Ireland...

(1690).

Politically, the Orange Institution is strongly linked to unionism

Unionism in Ireland

Unionism in Ireland is an ideology that favours the continuation of some form of political union between the islands of Ireland and Great Britain...

. Critics have accused the Institution of being sectarian

Sectarianism

Sectarianism, according to one definition, is bigotry, discrimination or hatred arising from attaching importance to perceived differences between subdivisions within a group, such as between different denominations of a religion, class, regional or factions of a political movement.The ideological...

, triumphalist

Triumphalism

Triumphalism is the attitude or belief that a particular doctrine, religion, culture, or social system is superior to and should triumph over all others...

and supremacist

Supremacism

Supremacism is the belief that a particular race, species, ethnic group, religion, gender, sexual orientation, belief system or culture is superior to others and entitles those who identify with it to dominate, control or rule those who do not.- Sexual :...

. Catholics, and those whose close relatives are Catholic, are banned from becoming members. Non-creedal and non-trinitarian

Nontrinitarianism

Nontrinitarianism includes all Christian belief systems that disagree with the doctrine of the Trinity, namely, the teaching that God is three distinct hypostases and yet co-eternal, co-equal, and indivisibly united in one essence or ousia...

denominations (such as members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons

Mormons

The Mormons are a religious and cultural group related to Mormonism, a religion started by Joseph Smith during the American Second Great Awakening. A vast majority of Mormons are members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints while a minority are members of other independent churches....

), Unitarians

Unitarianism

Unitarianism is a Christian theological movement, named for its understanding of God as one person, in direct contrast to Trinitarianism which defines God as three persons coexisting consubstantially as one in being....

and some branches of Quakers) are also ineligible for membership, although these denominations do not have large congregations where most Orange lodges are found.

History

William III of England

William III & II was a sovereign Prince of Orange of the House of Orange-Nassau by birth. From 1672 he governed as Stadtholder William III of Orange over Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders, and Overijssel of the Dutch Republic. From 1689 he reigned as William III over England and Ireland...

, the Dutch prince who became King of England, Scotland, and Ireland

King of Ireland

A monarchical polity has existed in Ireland during three periods of its history, finally ending in 1801. The designation King of Ireland and Queen of Ireland was used during these periods...

in the Glorious Revolution

Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution, also called the Revolution of 1688, is the overthrow of King James II of England by a union of English Parliamentarians with the Dutch stadtholder William III of Orange-Nassau...

of 1688. In particular, the Institution remembers the victories of William III and his forces in Ireland in the early 1690s, especially the Battle of the Boyne.

Formation and early years

The 1790s were a time of political and religious conflict in Ireland. On one side were the Irish nationalistsIrish nationalism

Irish nationalism manifests itself in political and social movements and in sentiment inspired by a love for Irish culture, language and history, and as a sense of pride in Ireland and in the Irish people...

(mostly Irish Catholic

Irish Catholic

Irish Catholic is a term used to describe people who are both Roman Catholic and Irish .Note: the term is not used to describe a variant of Catholicism. More particularly, it is not a separate creed or sect in the sense that "Anglo-Catholic", "Old Catholic", "Eastern Orthodox Catholic" might be...

s, but also some liberal Anglicans) and on the other were the so-called "Protestant Ascendancy

Protestant Ascendancy

The Protestant Ascendancy, usually known in Ireland simply as the Ascendancy, is a phrase used when referring to the political, economic, and social domination of Ireland by a minority of great landowners, Protestant clergy, and professionals, all members of the Established Church during the 17th...

" and its supporters. In October 1791 the nationalist Society of United Irishmen was founded by liberal Protestants in Belfast

Belfast

Belfast is the capital of and largest city in Northern Ireland. By population, it is the 14th biggest city in the United Kingdom and second biggest on the island of Ireland . It is the seat of the devolved government and legislative Northern Ireland Assembly...

. Its leaders were mainly Presbyterians

Presbyterianism

Presbyterianism refers to a number of Christian churches adhering to the Calvinist theological tradition within Protestantism, which are organized according to a characteristic Presbyterian polity. Presbyterian theology typically emphasizes the sovereignty of God, the authority of the Scriptures,...

. They called for a reform of the Irish Parliament

Parliament of Ireland

The Parliament of Ireland was a legislature that existed in Dublin from 1297 until 1800. In its early mediaeval period during the Lordship of Ireland it consisted of either two or three chambers: the House of Commons, elected by a very restricted suffrage, the House of Lords in which the lords...

that would extend the vote to all Irish men (regardless of religion) and give Ireland greater independence from Britain.

Although the United Irishmen were trying to unite Catholics and Protestants behind their goal, northern County Armagh

County Armagh

-History:Ancient Armagh was the territory of the Ulaid before the fourth century AD. It was ruled by the Red Branch, whose capital was Emain Macha near Armagh. The site, and subsequently the city, were named after the goddess Macha...

was undergoing fierce sectarian

Sectarianism

Sectarianism, according to one definition, is bigotry, discrimination or hatred arising from attaching importance to perceived differences between subdivisions within a group, such as between different denominations of a religion, class, regional or factions of a political movement.The ideological...

conflict. Catholics and Protestants set up rural "vigilante

Vigilante

A vigilante is a private individual who legally or illegally punishes an alleged lawbreaker, or participates in a group which metes out extralegal punishment to an alleged lawbreaker....

" groups – on the Catholic side was the "Defenders

Defenders (Ireland)

The Defenders were a militant, vigilante agrarian secret society in 18th century Ireland, mainly Roman Catholic and from Ulster, who allied with the United Irishmen but did little during the rebellion of 1798.-Origin:...

" and on the Protestant side was the "Peep-o'-Day Boys". In July 1795 a Reverend Devine had held a sermon at Drumcree Church

Drumcree Church

Drumcree Parish Church, officially The Church of the Ascension, is the parish church of Drumcree Church of Ireland parish. The church is within the townland of Drumcree, roughly 1.5 miles to the northeast of Portadown, County Armagh....

to commemorate the "Battle of the Boyne". In his History of Ireland Vol I (published in 1809), the historian Francis Plowden described the events that followed this sermon:

Reverend Devine so worked up the minds of his audience, that upon retiring from service, on the different roads leading to their respective homes, they gave full scope to the anti-papisticalAnti-CatholicismAnti-Catholicism is a generic term for discrimination, hostility or prejudice directed against Catholicism, and especially against the Catholic Church, its clergy or its adherents...

zeal, with which he had inspired them... falling upon every Catholic they met, beating and bruising them without provocation or distinction, breaking the doors and windows of their houses, and actually murdering two unoffending Catholics in a bog. This unprovoked atrocity of the Protestants revived and redoubled religious rancour. The flame spread and threatened a contest of extermination...

The Orange Order was founded after an incident known as the "Battle of the Diamond

Battle of the Diamond

The Battle of the Diamond was a violent confrontation between the Catholic Defenders and a Protestant faction including Peep o' Day Boys, Orange Boys and local tenant farmers that took place on 21 September 1795 near Loughgall, County Armagh, Ireland. The Protestants were the victors, killing...

", which happened two months after the Drumcree sermon. It took place on 21 September 1795 near Loughgall

Loughgall

Loughgall is a small village and townland in County Armagh, Northern Ireland. In the 2001 Census it had a population of 285 people.Loughgall was named after a small nearby loch. The village is at the heart of the apple-growing industry and is surrounded by orchards. Along the village's main street...

, a few miles from Drumcree. It was a clash between Defenders and Peep-o'-Day Boys in which four to thirty (mostly un-armed) Defenders were killed. The Governor of Armagh, Lord Gosford, gave his opinion of the violence in County Armagh that followed the "battle" at a meeting of magistrates on 28 December 1795. He said:

It is no secret that a persecution is now raging in this country… the only crime is… profession of the Roman Catholic faith. Lawless banditti have constituted themselves judges….However, two former grand masters of the Order, William Blacker

William Blacker

Lieutenant-Colonel William Blacker was an Irish British Army officer and Member of the Royal Irish Academy.-Life and career:...

and Robert Hugh Wallace

Robert Hugh Wallace

Colonel Robert Hugh Wallace CB CBE PC was a British soldier and a lawyer and politician in Northern Ireland....

, have questioned this statement, saying whoever the Governor believed were the “lawless banditti” they could not have been Orangemen as there were no lodges in existence at the time of his speech. According to historian Jim Smyth:

Later apologistsApologeticsApologetics is the discipline of defending a position through the systematic use of reason. Early Christian writers Apologetics (from Greek ἀπολογία, "speaking in defense") is the discipline of defending a position (often religious) through the systematic use of reason. Early Christian writers...

rather implausibly deny any connection between the Peep-o'-Day Boys and the first Orangemen or, even less plausibly, between the Orangemen and the mass wrecking of Catholic cottages in Armagh in the months following 'the Diamond' — all of them, however, acknowledge the movement's lower class origins.

The Order's three main founders were James Wilson

James Wilson (Orangeman)

James Wilson was the founder of the Orange Institution, also known as the Orange Order.After a disturbance in Benburb on 24 June 1794, in which Protestant homes were attacked, Wilson appealed to the Freemasons, of which he was a member, to organise themselves in defence of the Protestant...

(founder of the Orange Boys), Daniel Winter and James Sloan

James Sloan

James Sloan may refer to:* James Sloan, co-founder of the Orange Institution in 1795* James F. Sloan, head of US Coast Guard Intelligence* James Sloan , United States Congressman from New Jersey...

. The first Orange lodge established in nearby Dyan, County Tyrone

County Tyrone

Historically Tyrone stretched as far north as Lough Foyle, and comprised part of modern day County Londonderry east of the River Foyle. The majority of County Londonderry was carved out of Tyrone between 1610-1620 when that land went to the Guilds of London to set up profit making schemes based on...

. Its first grand master was James Sloan of Loughgall, in whose inn the victory by the Peep-o'-Day Boys was celebrated. Like the Peep-o'-Day Boys, one of its goals was to hinder the efforts of Irish nationalist groups and uphold the "Protestant Ascendancy". The Orange Order's first ever marches were to celebrate the "Battle of the Boyne" and they took place on 12 July 1796 in Portadown

Portadown

Portadown is a town in County Armagh, Northern Ireland. The town sits on the River Bann in the north of the county, about 23 miles south-west of Belfast...

, Lurgan

Lurgan

Lurgan is a town in County Armagh, Northern Ireland. The town is near the southern shore of Lough Neagh and in the north-eastern corner of the county. Part of the Craigavon Borough Council area, Lurgan is about 18 miles south-west of Belfast and is linked to the city by both the M1 motorway...

and Waringstown

Waringstown

Waringstown is a village in County Down, Northern Ireland, two miles south-east of Lurgan. It lies within the parish of Donaghcloney, and in the barony of Iveagh Lower, Lower Half. In the 2001 Census it had a population of 2,523 people. It was built during the Plantation of Ulster and is typical of...

.

By the time the Orange Order formed, the United Irishmen (still led mainly by Protestants) had become a republican

Irish Republicanism

Irish republicanism is an ideology based on the belief that all of Ireland should be an independent republic.In 1801, under the Act of Union, the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland merged to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland...

group and sought an independent Irish republic that would "Unite Catholic, Protestant and Dissenter". United Irishmen activity was on the rise, and the government hoped to thwart it by backing the Orange Order from 1796 onward. Nationalist historians Thomas A. Jackson

Thomas A. Jackson

Thomas A. "Tommy" Jackson was a founding member of the Socialist Party of Great Britain and later the Communist Party of Great Britain. He was a leading communist activist and newspaper editor and worked variously as a party functionary and a freelance lecturer.-Early years:Thomas A. Jackson, best...

and John Mitchel

John Mitchel

John Mitchel was an Irish nationalist activist, solicitor and political journalist. Born in Camnish, near Dungiven, County Londonderry, Ireland he became a leading member of both Young Ireland and the Irish Confederation...

argued that the government's goal was to hinder the United Irishmen by fomenting sectarianism

Sectarianism

Sectarianism, according to one definition, is bigotry, discrimination or hatred arising from attaching importance to perceived differences between subdivisions within a group, such as between different denominations of a religion, class, regional or factions of a political movement.The ideological...

— it would create disunity and disorder under pretence of "passion for the Protestant religion". Mitchel wrote that the government invented and spread "fearful rumours of intended massacres of all the Protestant people by the Catholics". Historian Richard R Madden wrote that "efforts were made to infuse into the mind of the Protestant feelings of distrust to his Catholic fellow-countrymen". Thomas Knox

Thomas Knox

Thomas Knox was a Scottish prelate from the 17th century. The son of Andrew Knox, Bishop of the Isles, he received crown provision to the Deanery of the Isles on 4 August 1617...

, British military commander in Ulster, wrote in August 1796 that "As for the Orangemen, we have rather a difficult card to play...we must to a certain degree uphold them, for with all their licentiousness, on them we must rely for the preservation of our lives and properties should critical times occur".

When the United Irishmen rebellion

Irish Rebellion of 1798

The Irish Rebellion of 1798 , also known as the United Irishmen Rebellion , was an uprising in 1798, lasting several months, against British rule in Ireland...

broke out in 1798, Orangemen and ex-Peep-o'-Day Boys helped government forces in suppressing it. According to Ruth Dudley Edwards and two former grand masters, Orangemen were among the first to contribute to repair funds for Catholic property damaged in the violence surrounding the rebellion.

Suppression

In the early nineteenth century, Orangemen were heavily involved in violent conflict with an Irish Catholic and nationalist secret society called the Ribbonmen. One instance, published in a 7 October 1816 edition of the Boston Commercial Gazette, included the murder of a Catholic priest and several members of the congregation of Dumreilly parish in County CavanCounty Cavan

County Cavan is a county in Ireland. It is part of the Border Region and is also located in the province of Ulster. It is named after the town of Cavan. Cavan County Council is the local authority for the county...

on 25 May 1816. According to the article, "A number of Orangemen with arms rushed into the church and fired upon the congregation". On 19 July 1823 the Unlawful Oaths Bill was passed, banning all oath-bound societies in Ireland. This included the Orange Order, which had to be dissolved and reconstituted. In 1825 a bill banning unlawful associations – largely directed at Daniel O'Connell

Daniel O'Connell

Daniel O'Connell Daniel O'Connell Daniel O'Connell (6 August 1775 – 15 May 1847; often referred to as The Liberator, or The Emancipator, was an Irish political leader in the first half of the 19th century...

and his Catholic Association

Catholic Association

The Catholic Association was an Irish Roman Catholic political organisation set up by Daniel O'Connell in the early nineteenth century to campaign for Catholic emancipation within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was one of the first mass-membership political movements in...

, compelled the Orangemen once more to dissolve their association. When Westminster

Palace of Westminster

The Palace of Westminster, also known as the Houses of Parliament or Westminster Palace, is the meeting place of the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom—the House of Lords and the House of Commons...

granted Catholic Emancipation

Catholic Emancipation

Catholic emancipation or Catholic relief was a process in Great Britain and Ireland in the late 18th century and early 19th century which involved reducing and removing many of the restrictions on Roman Catholics which had been introduced by the Act of Uniformity, the Test Acts and the penal laws...

in 1829, Irish Catholics were free at last to take seats as MPs and play a part in framing the laws of the land. The likelihood of Catholic members holding the balance of power in the Westminster Parliament further increased the alarm of Orangemen in Ireland, as to them it meant the possible revival of a Catholic-dominated Parliament controlled from Rome

Rome Rule

"Rome Rule" was a term used by Irish unionists and socialists to describe the belief that the Roman Catholic Church would gain political control over their interests with the passage of a Home Rule Bill...

, and an end to the Protestant Ascendancy. From this moment on, the Orange Order re-emerged in a new and even more militant form.

In 1845 the ban was lifted, but the famous Battle of Dolly's Brae between Orangemen and Ribbonmen in 1849 led to a ban on Orange marches which remained in place for several decades. This was eventually lifted after a campaign of disobedience led by William Johnston of Ballykilbeg.

Revival

By the late 19th century, the Order was in decline. However, its fortunes were revived by the spread of Protestant opposition to Irish nationalist mobilisation in the Irish Land League and then around the question of Home Rule. The Order was heavily involved in opposition to GladstoneWilliam Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone FRS FSS was a British Liberal statesman. In a career lasting over sixty years, he served as Prime Minister four separate times , more than any other person. Gladstone was also Britain's oldest Prime Minister, 84 years old when he resigned for the last time...

's first Irish Home Rule Bill 1886, and was instrumental in the formation of the Ulster Unionist Party

Ulster Unionist Party

The Ulster Unionist Party – sometimes referred to as the Official Unionist Party or, in a historic sense, simply the Unionist Party – is the more moderate of the two main unionist political parties in Northern Ireland...

(UUP). The strength of Protestant opposition to Irish self-government under possible Roman Catholic influence, especially in the Protestant-dominated province of Ulster

Ulster

Ulster is one of the four provinces of Ireland, located in the north of the island. In ancient Ireland, it was one of the fifths ruled by a "king of over-kings" . Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the ancient kingdoms were shired into a number of counties for administrative and judicial...

, eventually led to six Ulster counties remaining within the United Kingdom, as Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland is one of the four countries of the United Kingdom. Situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, it shares a border with the Republic of Ireland to the south and west...

.

In the first decade of the twentieth century, the Order suffered a split when Thomas Sloane left the organisation to set up the Independent Orange Order

Independent Orange Order

The Independent Loyal Orange Institution is an off-shoot of the Orange Institution, a Protestant fraternal organisation based in Northern Ireland.-Foundation:...

. Sloane had been suspended after running against a Unionist candidate on a pro-labour platform in an election in 1902.

Role in the partition of Ireland

In 1912 the Third Home Rule Bill was introduced in the British House of Commons. However, its introduction would be delayed until 1914. The Orange Order, along with the British Conservative PartyConservative Party (UK)

The Conservative Party, formally the Conservative and Unionist Party, is a centre-right political party in the United Kingdom that adheres to the philosophies of conservatism and British unionism. It is the largest political party in the UK, and is currently the largest single party in the House...

and unionists in general, were inflexible in opposing the Bill. The Order helped to organise the 1912 Ulster Covenant

Ulster Covenant

The Ulster Covenant was signed by just under half a million of men and women from Ulster, on and before September 28, 1912, in protest against the Third Home Rule Bill, introduced by the Government in that same year...

– a pledge to oppose Home Rule that was signed by up to 500,000 people. In 1911 some Orangemen began to arm themselves and train as a militia called the Ulster Volunteers. In 1913 the Ulster Unionist Council decided to bring these groups under central control, creating the Ulster Volunteer Force

Ulster Volunteer Force (1912)

The Ulster Volunteers were a unionist militia founded in 1912 to block Home Rule for Ireland. In 1913 they were organised into the Ulster Volunteer Force, with many of its members enlisting with the 36th Division at the outbreak of World War I...

, a militia dedicated to resisting Home Rule. There was a strong overlap between Orange Lodges and UVF units. A large shipment of rifles was imported from Germany to arm them in April 1914, in what became known as the Larne gun-running.

However, the crisis was interrupted by the outbreak of the World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

in August 1914. This caused the Home Rule Bill to be suspended for the duration of the war. Many Orangemen served in the war with the 36th (Ulster) Division suffering heavy losses and commemorations of their sacrifice are still an important element of Orange ceremonies.

The Fourth Home Rule Act was passed as the Government of Ireland Act 1920

Government of Ireland Act 1920

The Government of Ireland Act 1920 was the Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which partitioned Ireland. The Act's long title was "An Act to provide for the better government of Ireland"; it is also known as the Fourth Home Rule Bill or as the Fourth Home Rule Act.The Act was intended...

; the six north eastern counties of Ulster became Northern Ireland and the other twenty-six counties became Southern Ireland

Southern Ireland

Southern Ireland was a short-lived autonomous region of the United Kingdom established on 3 May 1921 and dissolved on 6 December 1922.Southern Ireland was established under the Government of Ireland Act 1920 together with its sister region, Northern Ireland...

. This self governing entity within the United Kingdom was confirmed in its status under the terms of the Anglo-Irish Treaty

Anglo-Irish Treaty

The Anglo-Irish Treaty , officially called the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was a treaty between the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and representatives of the secessionist Irish Republic that concluded the Irish War of...

of 1921, and in its borders by the Boundary Commission

Boundary Commission (Ireland)

The Irish Boundary Commission was a commission which met in 1924–25 to decide on the precise delineation of the border between the Irish Free State and Northern Ireland...

agreement of 1925. Southern Ireland became first the Irish Free State

Irish Free State

The Irish Free State was the state established as a Dominion on 6 December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty, signed by the British government and Irish representatives exactly twelve months beforehand...

in 1922 and then in 1949 a republic under the name of "Ireland

Republic of Ireland

Ireland , described as the Republic of Ireland , is a sovereign state in Europe occupying approximately five-sixths of the island of the same name. Its capital is Dublin. Ireland, which had a population of 4.58 million in 2011, is a constitutional republic governed as a parliamentary democracy,...

".

Since 1921

Prime Minister of Northern Ireland

The Prime Minister of Northern Ireland was the de facto head of the Government of Northern Ireland. No such office was provided for in the Government of Ireland Act 1920. However the Lord Lieutenant, as with Governors-General in other Westminster Systems such as in Canada, chose to appoint someone...

was an Orangeman and member of the Ulster Unionist Party

Ulster Unionist Party

The Ulster Unionist Party – sometimes referred to as the Official Unionist Party or, in a historic sense, simply the Unionist Party – is the more moderate of the two main unionist political parties in Northern Ireland...

(UUP); all but three Cabinet Ministers

Executive Committee of the Privy Council of Northern Ireland

The Executive Committee or the Executive Committee of the Privy Council of Northern Ireland was the government of Northern Ireland created under the Government of Ireland Act 1920. Generally known as either the Cabinet or the Government, the Executive Committee existed from 1922 to 1972...

were Orangemen; all but one unionist Senators

Senate of Northern Ireland

The Senate of Northern Ireland was the upper house of the Parliament of Northern Ireland created by the Government of Ireland Act 1920. It was abolished with the passing of the Northern Ireland Constitution Act 1973.-Powers:...

were Orangemen; and 87 of the 95 MPs who did not become Cabinet Ministers were Orangemen. James Craig

James Craig, 1st Viscount Craigavon

James Craig, 1st Viscount Craigavon, PC, PC , was a prominent Irish unionist politician, leader of the Ulster Unionist Party and the first Prime Minister of Northern Ireland...

, the first Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, maintained always that Ulster was in effect Protestant and the symbol of its ruling forces was the Orange Order. In 1932, Prime Minister Craig maintained that "ours is a Protestant government and I am an Orangeman". Two years later he stated: "I have always said that I am an Orangeman first and a politician and a member of this parliament

Parliament of Northern Ireland

The Parliament of Northern Ireland was the home rule legislature of Northern Ireland, created under the Government of Ireland Act 1920, which sat from 7 June 1921 to 30 March 1972, when it was suspended...

afterwards…All I boast is that we have a Protestant Parliament and a Protestant State

A Protestant Parliament for a Protestant People

A Protestant parliament for a Protestant people is a term that has been applied to the political institutions in Northern Ireland between 1921 and 1972. The term has been documented as early as February 1939, when Bishop Daniel Mageean, in his Lenten pastoral, stated that prime minister, Lord...

".

At its peak in 1965, the Order's membership was around 70,000, which meant that roughly 1 in 5 adult Protestant males were members. Since 1965, it has lost a third of its membership, notably in Belfast and Derry. The Order's political influence suffered greatly when the Unionist-dominated Northern Ireland Parliament was prorogued in 1972.

After the outbreak of "The Troubles

The Troubles