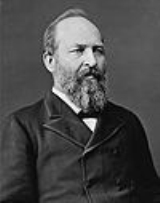

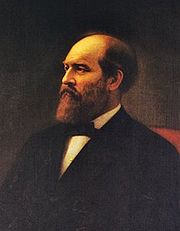

James Garfield

Encyclopedia

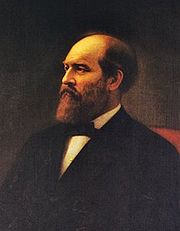

James Abram Garfield (November 19, 1831 – September 19, 1881) served as the 20th President of the United States

, after completing nine consecutive terms in the U.S. House of Representatives

. Garfield's accomplishments as President included a controversial resurgence of Presidential authority above Senatorial courtesy in executive appointments; energizing U.S. naval power; and purging corruption in the Post Office Department. Garfield made notable diplomatic and judiciary appointments, including a U.S. Supreme Court

justice. Garfield appointed several African Americans to prominent federal positions.

Garfield was a self-made man who came from a modest background, having been raised in obscurity on an Ohio farm by his widow

ed mother and brothers. To finance his education Garfield worked as a carpenter, and in 1856 he graduated from Williams College

, Massachusetts

. A year later, Garfield entered politics as a Republican

, after campaigning for the party's antislavery platform in Ohio. He married Lucretia Rudolph

in 1858, and in 1860 was admitted to practice law while serving as an Ohio State Senator

(1859–1861). Garfield opposed Confederate secession

, served as a Major General in the Union Army

during the American Civil War

, and fought in the battles of Middle Creek, Shiloh

and Chickamauga

. He was first elected to Congress in 1863 as Representative of the 19th District of Ohio.

Throughout Garfield's extended Congressional service after the Civil War, he fervently opposed the Greenback

, and gained a reputation as a skilled orator. He was Chairman of the Military Affairs Committee and the Appropriations Committee

and a member of the Ways and Means Committee. Garfield initially agreed with Radical Republican views regarding Reconstruction, then favored a moderate approach for civil rights enforcement for Freedmen

. In 1880, the Ohio legislature elected him to the U.S. Senate

; in that same year, the leading Republican presidential contenders – Ulysses S. Grant

, James G. Blaine

and John Sherman

– failed to garner the requisite support at their convention. Garfield became the party's compromise nominee for the 1880 Presidential Election

and successfully campaigned to defeat Democrat Winfield Hancock

in the election.

Garfield's presidency lasted just 200 days—from March 4, 1881, until his death on September 19, 1881, as a result of being shot by assassin Charles J. Guiteau

on July 2, 1881. Only William Henry Harrison

's presidency, of 32 days, was shorter. Garfield was the second of four United States Presidents who were assassinated. President Garfield advocated a bi-metal monetary system

, agricultural technology, an educated electorate, and civil rights for African American

s. He proposed substantial civil service reform, eventually passed in 1883 by his successor, Chester A. Arthur

, as the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act

.

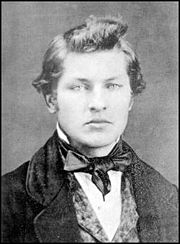

James Garfield was born the youngest of five children on November 19, 1831, in a log cabin in Orange Township, now Moreland Hills, Ohio

James Garfield was born the youngest of five children on November 19, 1831, in a log cabin in Orange Township, now Moreland Hills, Ohio

. His father, Abram Garfield, known locally as a wrestler, died when Garfield was 17 months old. Of Welsh

ancestry, he was reared and cared for by his mother, Eliza Ballou, who said, "He was the largest babe I had and looked like a red Irishman." Garfield's parents joined Disciples of Christ Church, which profoundly influenced their son. Garfield was able to receive rudimentary education at a village school in Orange, listening and discussing books read. Garfield knew he needed money to advance his learning.

At age 16, he struck out on his own, drawn seaward by dreams of being a seaman, and got a job for six weeks as a canal driver near Cleveland. Illness forced him to return home and, once recuperated, he began school at Geauga Academy, where he became keenly interested in academics, both learning and teaching. Garfield worked as a carpenter to support himself financially at the academy. Garfield later said of this early time, "I lament that I was born to poverty, and in this chaos of childhood, seventeen years passed before I caught any inspiration...a precious 17 years when a boy with a father and some wealth might have become fixed in manly ways." In 1849, he accepted an unsought position as a teacher, and thereafter developed an aversion to what he called "place seeking," which became, he said, "the law of my life." In 1850 Garfield resumed his church attendance and was baptized.

From 1851 to 1854, he attended the Western Reserve Eclectic Institute (later named Hiram College

From 1851 to 1854, he attended the Western Reserve Eclectic Institute (later named Hiram College

) in Hiram, Ohio

, where he was taught by Platt Rogers Spencer

. While at Eclectic, he was most interested in the study of Greek and Latin, and he was also engaged to teach. He developed a regular preaching circuit at neighboring churches, in some cases earning a gold dollar per service. Garfield then enrolled at Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts

, where he joined the Delta Upsilon

fraternity and graduated in 1856 as an outstanding student. Garfield was quite impressed with the college President, Mark Hopkins

, about whom he said, "The ideal college is Mark Hopkins on one end of a log with a student on the other." Garfield earned a reputation as a skilled debater and was made President of the Philogian Society and Editor of the Williams Quarterly.

After preaching briefly at Franklin Circle Christian Church (1857–58), Garfield gave up on that vocation and applied for a job as principal of a high school in Poestenkill, New York

. After another applicant had been chosen, he returned to teach at the Eclectic Institute. Garfield was an instructor in classical languages for the 1856–1857 academic year and was made Principal of the Institute from 1857 to 1860, successfully restoring it to viability after it had fallen on hard times. During this time, Garfield revealed himself to be sympathetic with the views of moderate Republicans, though he was not yet a party man. While he did not consider himself an abolitionist

, he was opposed to slavery. After Garfield finished his education, between the 1857 and 1858 elections, he began his career in politics as a "vigorous" stump speaker

in support of the Republican Party and their anti-slavery cause. In 1858, a migrant freethinker and evolutionary named Denton challenged him to a debate (Charles Darwin

's Origin of Species was published the next year). The debate, which lasted over a week, was considered as won convincingly by Garfield.

Garfield's first romantic interest was Almeda Booth in 1851, but it lasted only a year, with no formal engagement. On November 11, 1858, he married Lucretia Rudolph

Garfield's first romantic interest was Almeda Booth in 1851, but it lasted only a year, with no formal engagement. On November 11, 1858, he married Lucretia Rudolph

, known as "Crete" to friends, and a former star Greek pupil of Garfield's. They had seven children (five sons and two daughters): Eliza Arabella Garfield (1860–63); Harry Augustus Garfield

(1863–1942); James Rudolph Garfield

(1865–1950); Mary Garfield (1867–1947); Irvin M. Garfield (1870–1951); Abram Garfield (1872–1958); and Edward Garfield (1874–76). One son, James R. Garfield, followed him into politics and became Secretary of the Interior

under President Theodore Roosevelt

.

Garfield gradually became discontented with teaching and began to study law in 1859. He was admitted to the Ohio bar

in 1860. Before admission to the bar, he was invited to enter politics by local Republican Party leaders upon the death of Cyrus Prentiss, the presumed nominee for the state senate seat for the 26th District in Ohio. He was nominated by the party convention and then elected an Ohio state senator in 1859, serving until 1861. Garfield's signature effort in the state legislature was a bill providing for the state's first geological survey

to measure its mineral resources. His initial observations about the nation leading up to the Civil War

were that secession was quite inconceivable. His response was in part a renewed zeal for the July 4 celebrations in 1860.

After Abraham Lincoln

's election, Garfield was more inclined to arms than negotiations, saying, "Other states may arm to the teeth, but if Ohio so much as cleans her rusty muskets, it is said to have offended our brethren in the South. I am weary of this weakness." On February 13, 1861, the newly elected President Lincoln arrived in Cincinnati

by train to make a speech. Garfield observed that Lincoln was "distressingly homely", yet had "the tone and bearing of a fearless, firm man."

At the start of the American Civil War

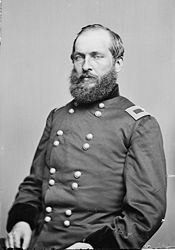

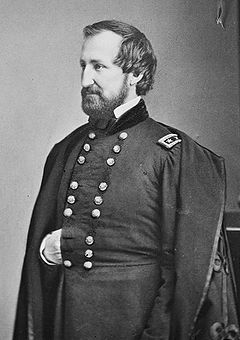

At the start of the American Civil War

, Garfield quickly grew frustrated with his vain efforts to obtain an officer's commission in the Union Army

. Ohio Governor William Dennison, Jr. charged him with a mission to travel to Illinois

to acquire musketry and to negotiate with the Governors of Illinois and Indiana

for the consolidation of troops. In the summer of 1861 he was finally commissioned a Colonel in the Union Army and given command of the 42nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry

.

General Don Carlos Buell

assigned Colonel Garfield the task of driving Confederate

forces out of eastern Kentucky

in November 1861, giving him the 18th Brigade for the campaign. In December, he departed Catlettsburg, Kentucky

, with the 40th Ohio Infantry

, the 42nd Ohio Infantry, the 14th Kentucky Infantry

, and the 22nd Kentucky Infantry

, as well as the 2nd (West) Virginia Cavalry and McLoughlin's Squadron of Cavalry. The march was uneventful until Union forces reached Paintsville, Kentucky

, on January 6, 1862, where Garfield's cavalry engaged the Confederates at Jenny's Creek. Garfield artfully positioned his troops so as to deceive Marshall into thinking that he was outnumbered, when in fact he was not. The Confederates, under Brig. Gen.

Humphrey Marshall

, withdrew to the forks of Middle Creek, two miles (3 km) from Prestonsburg, Kentucky

, on the road to Virginia

. Garfield attacked on January 9, 1862. At the end of the day's fighting the Confederates withdrew from the field, but Garfield did not pursue them, opting instead to withdraw to Prestonsburg

so he could resupply his men. His victory brought him early recognition and he was promoted to the rank of brigadier general on January 11.

Garfield later commanded the 20th Brigade of Ohio under Buell at the Battle of Shiloh

, where he led troops in an attempt, delayed by weather, to reinforce Maj Gen. Ulysses S. Grant

, after a surprise attack by Confederate General Albert S. Johnston

. He then served under Thomas J. Wood

in the Siege of Corinth

, where he assisted in the pursuit of Confederates in retreat by the overly-cautious Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, which resulted in the escape of Gen. P. G. T. Beauregard

and his troops. This engendered in the furious Garfield a lasting distrust of the training at West Point. Garfield's philosophy of war in 1862—to aggressively carry the war to Southern civilians—was not then shared by the Union leadership. The tactic was later adopted and demonstrated in the campaigns of Generals Sherman

and Sheridan

.

Garfield made the following comment in 1862 concerning slavery: "...if a man is black, be he friend or foe, he is thought best kept at a distance. It is hardly possible God will let us succeed while such enormities are practiced." That summer his health suddenly deteriorated, including jaundice and significant weight loss. (Biographer Peskin speculated this may have been infectious hepatitis.) Garfield was forced to return home, where his wife nursed him back to health and their marriage was reinvigorated. He returned to duty that autumn and served on the Court-martial of Fitz John Porter

. Garfield was then sent to Washington to receive further orders. With great frustration, he repeatedly received tentative assignments, extended and later reversed, to stations in Florida, Virginia and South Carolina. During this idleness time in Washington waiting for an assignment, Garfield had an affair with Lucia Calhoun. He later admitted the affair to his wife who forgave him.

In the spring of 1863 Garfield returned to the field as Chief of Staff for William S. Rosecrans, commander of the Army of the Cumberland

In the spring of 1863 Garfield returned to the field as Chief of Staff for William S. Rosecrans, commander of the Army of the Cumberland

; his influence in this position was greater than usual – with duties extending beyond mere communication to actual management of Rosecrans's army. Rosecrans, a highly energetic man, had a voracious appetite for conversation, which he deployed when he was unable to sleep; in Garfield he had found "the first well read person in the Army" and thus the ideal candidate for endless discussions through the night. The two became close, and covered all topics, especially religion; Rosecrans succeeded in softening Garfield's view of Catholicism. Garfield, with his enhanced influence, created an intelligence corps unsurpassed in the Union Army. He also recommended that Rosecrans should replace wing commanders Alexander McCook and Thomas Crittenden

due to their prior ineffectiveness. Rosecrans ignored these recommendations, with drastic consequences later, in the Battle of Chickamauga

. Garfield crafted a campaign designed to pursue and then trap Confederate General Braxton Bragg

in Tullahoma. The army advanced to that point with success, but Bragg retreated toward Chattanooga. Rosecrans then stalled his army's move against Bragg and made repeated requests for additional troops and supplies. Garfield argued with his superior for an immediate advance, also insisted upon by Lincoln and Rosecrans's commander, Gen. Halleck. Garfield conceived a plan to conduct a cavalry raid behind Bragg's line (similar to that Bragg was employing against Rosecrans) which Rosecrans approved; the raid, led by Abel Streight, failed, due in part to poor execution and weather. Garfield's detractors later claimed his concept was flawed. To address the continued dispute over whether to advance, Rosecrans called a war council of his generals; 10 of the 15 were opposed to the move, with Garfield voting in favor. Nevertheless Garfield, in an unusual move, drew up a report of the council's deliberations, and thus convinced Rosecrans to proceed with an advance against Bragg.

At the Battle of Chickamauga, Rosecrans issued an order which sought to fill a gap in his line, but which actually created one. As a result, his right flank was routed. Rosecrans concluded that the battle was lost and headed for Chattanooga to establish a defensive line. Garfield, however, thought that part of the army had held and, with Rosecrans's approval, headed across Missionary Ridge

to survey the Union status. Garfield's hunch was correct; his ride became legendary, while Rosecrans' error reinforced critical opinions about his leadership. While Rosecrans's army had avoided complete loss, they were left in Chattanooga surrounded by Bragg's army. Garfield sent a telegram to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton

alerting Washington to the need for reinforcements to avoid annihilation. As a result, Lincoln and Halleck succeeded in delivering 20,000 troops to Chattanooga by rail within nine days. One of Grant's early decisions upon assuming command of the Union Army was to replace Rosecrans with George H. Thomas. Garfield was issued orders to report to Washington, where he was promoted to Major General; shortly thereafter he gave an unambiguously abolitionist speech in Maryland. He was unsure of whether he should return to the field or assume the Ohio congressional seat he had won in October 1862. After a discussion with Lincoln, he decided in favor of the latter and resigned his commission. According to historian Jean Edward Smith

, Grant and Garfield had a "guarded relationship", since Grant put Thomas in charge of the Army of the Cumberland, rather than Garfield, after Rosecrans was dismissed.

Garfield communicated his frustration with Rosecrans in a confidential letter to his friend Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase

. Garfield's detractors later used this letter, which Chase never personally disclosed, to foster widespread criticism of Garfield as a betrayer, despite the fact that Halleck and Lincoln shared the same concerns over Rosecrans's reluctance to attack, and that Garfield had openly conveyed his concerns to Rosecrans. In later years, Charles Dana

of the New York Sun allegedly had sources indicating that Garfield had publicly stated that Rosecrans had fled the battlefield during the Battle of Chickamauga. According to biographer Peskin, the credibility of the information and the sources used are questionable. According to historian Bruce Catton

, Garfield's statements influenced the Lincoln administration to find a replacement for Rosecrans.

, was vulnerable. Garfield was conflicted – he was sure that he could better serve in Congress than in camp, but he was determined that his military position not be used as a stepping stone to political advancement. He therefore resorted to his long-held objection to "place-seeking", expressed a willingness to serve if elected, and otherwise left the matter to others. Garfield was nominated at the Republican convention on the 75th roll call vote. In October 1862 he defeated D.B. Woods by a two-to-one margin in the general election for the District's House seat in the 38th Congress

.

After the election, Garfield was anxious to determine his next military assignment and went to Washington for this purpose. While there, he developed a close alliance with Salmon P. Chase, Lincoln's Treasury Secretary. Garfield became a member of the Radical Republicans, led by Chase, in contrast with the moderate wing of the party, led by Lincoln and Montgomery Blair

. Garfield was as frustrated with Lincoln's lack of aggressiveness in pursuing the rebel enemy as Lincoln had been with Gen. McClellan. Chase and Garfield shared a disdain for West Point and the President, though Garfield praised the Emancipation Proclamation

. Garfield also shared a negative view of General McClellan, whom he considered the epitome of the Democratic

, pro-slavery, poorly-trained West Point generals.

Garfield became enthralled by the economic and financial policy discussions in Chase's office, and these subjects became his lifelong passion and expertise. Like Chase, Garfield became a staunch proponent of "honest money" or "specie payment" backed by a gold standard

, and was therefore a strong opponent of the "greenback

"; he regretted very much, but understood, the necessity for suspension of specie payment

during the emergency presented by the Civil War.

Although his desire was to continue his Army service, Garfield reluctantly took his seat in Congress upon resigning his military commission in December 1863. His first-born three-year-old child Eliza suddenly died that same month. Although he initially took a room by himself, his grief over the death of Eliza compelled him to find a roommate, which he did—Robert C. Schenck

. After Garfield's term ended, Lucretia moved to Washington to be with her husband, and the two, thereafter, never lived apart.

Garfield immediately showed an ability to command the attention of the unruly House. According to a reporter, "...when he takes the floor, Garfield's voice is heard above all others. Every ear attends...his eloquent words move the heart, convince the reason, and tell the weak and wavering which way to go." He was one of the more hawkish Republicans in the House, and served on Schenck's Military Affairs Committee

, which brought him prominence in the midst of the predominant war issues. Garfield aggressively promoted the need for a military draft, an issue almost all others shunned.

Early in his tenure, he differed from his party on several issues; his was the solitary Republican vote to terminate the use of bounties in recruiting. Some financially-able recruits had used the bounty system to buy their way out of service (called commutation), which he considered reprehensible. After many false starts, Garfield, with the support of Lincoln, procured the passage of an aggressive conscription bill which excluded commutation. In 1864 Congress passed a bill to revive the rank of Lieutenant General

. Garfield, who shared the opinion of Thaddeus Stevens

, was not in favor of this action, because the rank was intended for Grant, who had dismissed Rosecrans. Also, the recipient would thereby be given an advantage in possibly opposing Lincoln in the next election. Garfield was nevertheless very tentative in his support for the President's re-election.

Garfield, aligned with the Radical Republicans on some issues, not only favored abolition, but early in his career believed that the leaders of the rebellion had forfeited their constitutional rights. He supported the confiscation of southern plantations and even exile or execution of rebellion leaders as a means to ensure the permanent destruction of slavery. He felt Congress was obliged "to determine what legislation is necessary to secure equal justice to all loyal persons, without regard to color." With respect to the Presidential election of 1864, Garfield did not consider Lincoln particularly worthy of re-election, but no other viable alternative was available. "I have no candidate for President. I am a sad and sorrowful spectator of events." He attended the party convention and promoted Rosecrans for the V.P. nomination; this was greeted by Rosecrans's characteristic indecision, so the nomination went to Andrew Johnson

. Garfield voted with the Radical Republicans in passing the Wade–Davis Bill, designed to give Congress more authority over Reconstruction, but the bill was defeated by Lincoln's pocket veto

.

Garfield partnered with Ralph Plumb

in land speculation hoping to become wealthy, but this met with limited success. He joined with the Philadelphia-based Phillips brothers in an oil exploration investment which was moderately profitable. Garfield resumed the practice of law in 1865 as a means to improve his personal finances. His investment efforts took him to Wall Street where, the day after Lincoln's assassination, a riotous crowd led him into an impromptu speech, in part as follows: "Fellow citizens! Clouds and darkness are round about Him! His pavilion is dark waters and thick clouds of the skies! Justice and judgment are the establishment of His throne! Mercy and truth shall go before His face! Fellow citizens! God reigns, and the Government at Washington still lives!" According to witnesses the effect was tremendous and the crowd was immediately calmed. This became one of the most well-known incidents of his career.

Garfield's radicalism moderated after the civil war and Lincoln's assassination, and he assumed a temporary role as peacemaker between Congress and Andrew Johnson. At this time he commented on the readmission of the confederate states: "The burden of proof rests on each of them to show whether it is fit again to enter the federal circle in full communion of privilege. They must give us proof, strong as holy writ, that they have washed their hands and are worthy again to be trusted." When Johnson's veto terminated the Freedman's Bureau, the President had effectively entrenched himself against Congress, and Garfield rejoined the Radical camp.

With a reduced agenda on the Military Affairs Committee, Garfield was placed on the House Ways and Means Committee

, a long-awaited opportunity to focus exclusively on financial and economic issues. He immediately reprised his opposition to the greenback, saying, "any party which commits itself to paper money will go down amid the general disaster, covered with the curses of a ruined people." He called greenbacks "the printed lies of the government" and became obsessed with the morality, as well as the legality, of specie payment, and enforcement of the gold standard. This policy was against his personal interests; his investment profits were dependent upon inflation, the by-product of the greenback. His demand for "hard money" was distinctly deflationary in nature, and was opposed by most businessmen and politicians. For a time, Garfield appeared to be the only Ohio politician to hold this position.

As a proponent of laissez-faire on the economic front, he declared, "the chief duty of the government is to keep the peace and stand out of the sunshine of the people." This view was in stark contrast to his view of the role of government in reconstruction efforts. Another inconsistency in Garfield's laissez-faire philosophy was his position on free trade – he favored the tariff

, out of political necessity – when it served to protect his district's products.

Garfield was one of three attorneys who argued for the petitioners in the famous Supreme Court case Ex parte Milligan

in 1866. This was, despite many years of practicing law, Garfield's first court appearance. Jeremiah Black had taken him in as a junior partner a year before, and assigned the case to him in light of his highly reputed oratory skills. The petitioners were pro-Confederate northern men who had been found guilty and sentenced to death by a military court for treasonous activities. The case turned on whether the defendants should instead have been tried by a civilian court; Garfield was victorious, and instantly achieved a reputation as a preeminent appellate lawyer.

Despite the allure of a newly lucrative law practice, there was little hesitancy on Garfield's part in deciding to stand for re-election in 1866, due primarily to the urgency presented by Reconstruction. The competition was stiffer, since Garfield now had taken positions on issues which bore defending, such as the draft legislation he supported, tariffs, and his involvement in the Milligan case. As much as anyone, Harmon Austin, a local man of influence, was indispensable to Garfield's success, keeping a finger on the political pulse of the district. The party convention went smoothly in his favor and Garfield won the election with a 5-to-2 margin. At the same time, the Republicans took two-thirds of the national Congressional seats.

Despite the allure of a newly lucrative law practice, there was little hesitancy on Garfield's part in deciding to stand for re-election in 1866, due primarily to the urgency presented by Reconstruction. The competition was stiffer, since Garfield now had taken positions on issues which bore defending, such as the draft legislation he supported, tariffs, and his involvement in the Milligan case. As much as anyone, Harmon Austin, a local man of influence, was indispensable to Garfield's success, keeping a finger on the political pulse of the district. The party convention went smoothly in his favor and Garfield won the election with a 5-to-2 margin. At the same time, the Republicans took two-thirds of the national Congressional seats.

Garfield returned to Washington very glum in spite of his success, taking the campaign criticism quite hard. He was disgusted as well at what he thought was insane talk of impeaching President Johnson. With respect to Reconstruction, he thought Congress had been magnanimous in its offers to the South. When the rebels responded to this as a sign of weakness to be exploited by further demands, he was quite prepared to renew his view of them as enemies of the Union. This attitude was popular back home, and initiated talk of a Garfield-for-Governor campaign. Garfield promptly quashed it.

The Congressman expected his new term would bring an appointment as Chairman of the Ways and Means Committee, but this was not to be, due largely to his emphatic position in favor of hard money, which did not reflect the House consensus. He was appointed as chairman of the Military Affairs Committee, the primary agenda item there being the reorganization and reduction of the armed forces to put them on a peacetime footing. Garfield at this time endorsed the view that the Senate, via the Tenure of Office Act, had final say on Presidential appointments, a position he would radically change when President himself.

In another reassessment, Garfield supported articles of impeachment against President Andrew Johnson over charges that he violated the Tenure of Office Act by removing Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton. Garfield was absent for the actual vote due to legal work. Support for impeachment was very high, but the result was in doubt due to forebodings about the value of President pro tempore

, U.S. Senator Benjamin Wade

, a Radical Republican, as successor to President Johnson. He felt the senators were more interested in making speeches than conducting a proper trial. In the end, Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase

, who presided over the trial, was thought to have brought about Johnson's acquittal by the Senate with his statements from the bench. Thus, Garfield's very close friend distinctly became a political adversary, though he persevered with the economic and financial views he had earlier learned from Chase. In 1868 Garfield gave his noted two-hour "Currency" speech in the House, which was widely applauded as his best oratory yet; in it he advocated a gradual resumption of specie payment.

While Garfield had by then established himself as a superb orator while managing legislation on the floor of the House, he demonstrated little feel for the mood of the members or ability to control debate on items he brought forward. He continued in this new term to expect the Chairmanship of the Ways and Means Committee, but again this was misplaced, due in large part to his shortcomings as a parliamentarian; he was given the chair of the Banking and Currency Committee

, but regretted having lost the Military Affairs Chairmanship. One legislative priority of his fourth term was a bill to establish a Department of Education, which succeeded, only to be brought down by poor administration on the part of the first Commissioner of Education, Henry Barnard.

Another pet project of Garfield's this term was a bill to transfer Indian Affairs from the Interior Department to the War Department

. His estimate was that the Indians' culture could be more effectively "civilized" with the help of the more structured and disciplined military. The proposal was thought to be ill-conceived from the outset, but Garfield failed to perceive popular opinion. On a positive note in this term, Garfield was appointed chairman of a Subcommittee on the Census; as with other things mathematical, he threw himself into this head and shoulders. The two accomplishments of his work here were to revamp the counting process and to implement a major change in the questionnaire. Garfield showed improvement in handling this on the House floor and it was passed there, although it was stopped in the Senate; ten years later, a similar bill became law, with most of his groundwork in place.

In September 1870 Garfield was chairman of a Congressional committee investigating the Black Friday

Gold Panic scandal. The committee investigation into corruption was thorough, but found no indictable offenses. Garfield refused, as irrelevant, a request to subpoena the President's sister, whose husband was allegedly involved in the scandal. Garfield took full advantage of the opportunity to blame the fluctuating greenback for sowing the seeds of greed and speculation that led to the scandal. Garfield also pursued his anti-inflationist campaign against the greenback through his work on the bill for a national bank system. He successfully used the bill as a means to reduce the volume of greenbacks in circulation. Garfield's committee investigated President Grant's wife Julia's financial record. Tension remained between President Grant and Rep. Garfield.

As in the past, Garfield expected the leadership of the Ways and Means Committee to be his, but again it escaped him, due to opposition from the influential Horace Greeley

. He was appointed Chairman of the Appropriations Committee

, a position he initially spurned. In time the post commanded his interest and improved his skills as a floor manager. Garfield's outlook for the Republican Party, and the Democrats as well, was very negative at this point. He stated that "the death of both parties is all but certain; the Democrats, because every idea they have brought forward in the past 12 years is dead; and the Republicans, because its ideas have been realized." Nevertheless, when casting his votes, he remained a party regular.

Garfield thought the land grants given to expanding railroads to be an unjust practice; as well, he opposed some monopolistic practices by corporations, as well as the power sought by the workers' unions. By this time Garfield's Reconstruction philosophy had moderated. He hailed the passage of the 15th Amendment

as a triumph, and he favored the re-admission of Georgia to the Union as a matter of right, not politics. In 1871, however, Garfield could not support the Ku Klux Klan Act, passed by Congress in 1871, saying "I have never been more perplexed by a piece of legislation". He was torn between his indignation of "these terrorists" and his concern for the freedoms endangered by the power the bill gave to the President to enforce the Act through suspension of habeas corpus

.

Garfield supported the proposed establishment of the United States civil service

as a means of alleviating the burden of aggressive office seekers upon elected officials. He especially wished to eliminate the common practice whereby government workers, in exchange for their positions, were forced to kick back a percentage of their wages as political contributions.

During this term, discontented with public service, Garfield pursued opportunities in law practice, but declined a partnership offer after being advised his prospective partner was of "intemperate and licentious" reputation. Family life had also increased in importance to Garfield, who said to his wife in 1871, "When you are ill, I am like the inhabitants of a country visited by earthquakes. Like they, I lose all faith in the eternal order and fixedness of things."

In 1872 he was one of a number of Congressmen involved in the alleged Crédit Mobilier of America scandal

. As part of their expansion efforts, the principals of the Union Pacific Railroad

formed Crédit Mobilier of America and issued stock. Congressman Oakes Ames testified Garfield had purchased 10 shares of Crédit Mobiler stock for $1000, received accrued stock interest and $329 (33 per cent) in dividends sometime between December 1867 and June 1868. Ames's credibility suffered greatly due to substantive changes he made in his story under oath, along with very inconsistent and inaccurate records he provided. Garfield biographer Peskin concludes, "From a strictly legal point of view, Ames's testimony was worthless. He repeatedly contradicted himself on important points." According to the New York Times, Garfield had been in debt at the time, having taken out a mortgage on his property. Though Garfield was properly questioned for buying the stock, he had returned it to the seller. The scandal did not imperil his political career severely, though he denied the charges against him rather ineffectively, since the details were convoluted and were never clearly articulated or convincingly proven.

In 1873 Garfield appealed to President Grant to appoint Justice Noah H. Swayne as Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court. The previous Chief Justice, Salmon P. Chase

, had died in office May 7, 1873. Pres. Grant, however, appointed Morrison R. Waite.

Later in this term, Garfield found himself in the position of having to vote for his Appropriation Committee's bill, which included a provision to increase Congressional and Presidential salaries, something he opposed. This controversial act, known as the "Salary Grab

", was signed into law in March 1873. In June congressional supporters of the law received vitriolic response from the press and the voting public. This vote was the source of an increased degree of criticism of Garfield, though he was reappointed Chairman of the Appropriations Committee and placed on the Rules Committee. The vote did, however, give rise to stiffer competition in the next election. He returned his own salary increase to the U.S. Treasury.

The Democrats assumed control of Congress in the 1874 election for the first time in 20 years. In the lame duck

session, with Garfield's support but mixed reaction, Congress passed a compromise measure providing for specie payment, to take effect in 1879. In the new session Garfield was appointed to the Ways and Means Committee and the Pacific Railroad Committee. Also in this session, Garfield and John Coburn

uncovered corruption in the Post Tradership Office at Fort Sill

—control of supplies had been monopolized, with overpricing occurring. The abuses were corrected as a result of the investigation, but Garfield and others were suspected of allowing Secretary of War William Belknap to avoid exposure. Belknap later resigned to evade impeachment when details of his involvement were revealed.

. Blaine's chances for nomination diminished with his sudden physical collapse and subsequent recuperation; when the party nominated Rutherford B. Hayes

, Garfield immediately endorsed his party's standard bearer. In terms of his own re-election, Garfield had very much desired to re-enter private life, but since the outlook for his party was dire, he felt duty-bound to join the fray. His campaign manager Austin again relied on Garfield's appointees to man their stations in the district, resulting in a unanimous party nomination, and an election victory with 60% of the vote. Any celebration was short lived, as Garfield's youngest child, Neddie, suddenly fell ill with whooping cough and died.

When Hayes appeared to have narrowly lost the election, the Republicans launched recount efforts. Grant asked Garfield to serve as a "neutral observer" in the recount in Louisiana. His role quickly morphed into that of investigator into the "rifle clubs" which the Republicans alleged were formed by the Democrats to intimidate the black voters. Garfield's report, along with others, created enough doubt to change the election results in that state, as well as in Florida, South Carolina, and Oregon; these states then were saddled with two conflicting slates of electoral votes, which under the Constitution made Congress the final arbiter of the election. The Congress then passed a bill establishing the Electoral Commission

When Hayes appeared to have narrowly lost the election, the Republicans launched recount efforts. Grant asked Garfield to serve as a "neutral observer" in the recount in Louisiana. His role quickly morphed into that of investigator into the "rifle clubs" which the Republicans alleged were formed by the Democrats to intimidate the black voters. Garfield's report, along with others, created enough doubt to change the election results in that state, as well as in Florida, South Carolina, and Oregon; these states then were saddled with two conflicting slates of electoral votes, which under the Constitution made Congress the final arbiter of the election. The Congress then passed a bill establishing the Electoral Commission

, which would determine the winner once and for all. Although Garfield opposed the Commission, he found himself appointed to it. Hayes emerged the victor by a Commission vote of 8 to 7, and the decision held after a Democratic attempt to filibuster

the final result. Since James G. Blaine moved from the House to the United States Senate

, Garfield became the minority Republican floor leader

of the House.

The election of 1878 brought no significant opposition to Garfield's seat in the House, though two potential obstacles existed: the Greenback Party put up a candidate, Judge Tuttle; and the district had been re-shuffled by the Democrats in an attempt to weaken the Republicans' hold. Garfield still marched to victory with a 3-to-2 margin.

Garfield at this time purchased the property in Mentor

that reporters later dubbed Lawnfield, and from which he would conduct the first successful front porch campaign

for the Presidency. The home is now maintained by the National Park Service

as the James A. Garfield National Historic Site

.

Garfield's last Congressional session was devoted primarily to ensuring that Hayes' vetoes of Democratic appropriations were sustained; presumably Garfield succeeded, as he named his new dog "Veto".

When the Ohio off-year campaign of 1879 approached, Garfield turned his attention to securing the U. S. Senate seat for Ohio, vacated by John Sherman. The first step was to bring about a Republican victory in the Ohio legislature, which would choose the Senator. Once the Republicans captured the legislature, Garfield's victory was never in doubt; he was elected to the Senate by acclamation.

delegates in his speech against Sen. Conkling's convention rule that stated all state delegates must vote unanimously for only one candidate. After over thirty ballots, the vote totals for the leading contenders were within five votes of where they had been on the first ballot. With the 34th ballot, Wisconsin began the break to Garfield that would end with his nomination as the party's Presidential candidate. Garfield's capture of the 1880 nomination for the Presidency over the prominent contenders was considered historic. Garfield defeated the front runner Ulysses S. Grant's controversial third term bid for the nomination.

Thomas Nichol, Wharton Barker, and Benjamin Harrison

were widely considered to be the primary architects of Garfield's ascendancy during the convention, but no one could have controlled this unpredictable outcome for such a dark horse—one who had personally objected at every step. To obtain Republican Stalwart support for the ticket, former New York customs collector Chester A. Arthur

was chosen as the vice-presidential nominee and Garfield's running mate.

In the wake of such a fractured convention, the outlook for Garfield's campaign was less than optimal. In an effort to heal residual wounds from the convention, Garfield traveled to New York to bring the party's warring factions together in what was called the "New York Conference", and what was considered a personal triumph. This was the only trip of consequence which Garfield made away from home during the campaign. Powerful railroad interests were courted by the party in the wake of Supreme Court decisions that had been adverse to their interests. After assuring them that they would have the President's ear in such matters, Garfield gained their support.

Another issue in the Election of 1880 was Chinese immigration; those in the West, particularly California

, were opposed to Chinese immigration, considered antithetical to normal economic growth in that region. Easterners, such as Senator George F. Hoar

, took a more philosophical and religious stand in favor of Chinese immigration. On the eve of the election the Democrats widely published a letter—allegedly over Garfield's signature—which favored Chinese immigration, in an attempt to affect the outcome of the election. The timing of the letter's publication, some obvious inconsistencies in the letter's wording, and even the handwriting itself, led many to believe it to be a forgery.

In the general election, Garfield defeated the Democratic candidate Winfield Scott Hancock

, another distinguished former Union Army general, by 214 electoral votes to 155. The popular vote had a plurality of just over 7,000 votes out of more than 8.89 million cast. He became the only man ever to be elected to the Presidency directly from the House of Representatives and was for a short period a sitting Representative, Senator-elect, and President-elect.

, a deranged political office seeker, on July 2, 1881. Garfield lived for 80 days after he was shot, but was unable to govern. During his limited time in office, Garfield managed to initiate reform of the Post Office Department's notorious "star route

" rings and reassert the superiority of the office of the President over the U.S. Senate on the issue of executive appointments. Garfield made four federal court appointments and filled one vacancy on the U.S. Supreme Court

. His inaugural address set the agenda for his Presidency, but he did not live long enough to implement most of these policies. Garfield's persistent call for civil service reform, however, was fulfilled with the passage of the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act

, enacted by Congress and signed by President Chester A. Arthur

in 1883. Indeed, Garfield's assassination was the primary motivation for the reform bill's passage. Garfield's single executive order was to provide government workers the day off on May 30, 1881, in order to decorate the graves of those who died in the Civil War. At the time of Garfield's residence in the office, the President's annual salary was $50,000, which would be largely consumed for the operation of the White House. And, despite rumors of ill-gotten wealth, Garfield could afford no horse and buggy to park in the White House stable, but accepted Hayes' offer of his own quite used-up rig.

Between his election and his inauguration, Garfield was occupied with assembling a cabinet that would establish peace between the warring factions of the Republican Party, led by U.S. Sen. Roscoe Conkling

Between his election and his inauguration, Garfield was occupied with assembling a cabinet that would establish peace between the warring factions of the Republican Party, led by U.S. Sen. Roscoe Conkling

and James G. Blaine. Blaine was appointed Secretary of State; Blaine was not only the President's closest advisor, he was obsessed with knowing all that took place in the White House, and even was said to have spies posted there in his absence. Garfield nominated William Windom

of Minnesota as Secretary of the Treasury, William H. Hunt

of Louisiana as Secretary of the Navy, Robert Todd Lincoln

as Secretary of War, Samuel J. Kirkwood

of Iowa as Secretary of the Interior. New York was represented by Thomas Lemuel James

as Postmaster General. He appointed Pennsylvania's Wayne MacVeagh

, an adversary of Blaine's, as Attorney General

. Blaine tried to sabotage the appointment by convincing Garfield to name a nemesis of MacVeagh, William E. Chandler

, as Solicitor General

under MacVeagh. Only Chandler's rejection by the Senate forestalled MacVeagh's resignation over the nomination.

Snow covered much of the Capitol grounds during Garfield's inauguration, which had a low turnout of about 7,000 people. He was sworn into office by Chief Justice Morrison Waite

on March 4, 1881.

In Garfield's Inaugural Address he emphasized the civil rights of African Americans. He believed that blacks deserved the "full rights of citizenship." Garfield warned of the dangers of blacks' rights being taken away and their becoming "a permanent disfranchised peasantry." He stated, "Freedom can never yield its fullness of blessings so long as the law or its administration places the smallest obstacle in the pathway of any virtuous citizen." Garfield stated that those who had the right to vote needed to be literate and stressed the need for federal "universal education." In terms of finance, Garfield stated that bimetallism

"arrangements can be made between the leading commercial nations which will secure the general use of both metals." The President advocated agriculture as an important part of the American economy that created affordable "homes and employment for more than one-half of our people, and furnishes much the largest part of all our exports." Garfield stated that agricultural science needed to be supported by the federal government. President Garfield stated that polygamy

offended "the moral sense of manhood" and that the LDS Church, which advocated the practice, prevented the "administration of justice through ordinary instrumentalities of law."

Garfield's enduring political legacy came when he spoke on civil service reform in making federal appointments:

John Philip Sousa

led the Marine Corps band at the inaugural parade and ball. The ball was held in the National Museum

, now the Arts and Industries Building

, of the Smithsonian Institution

in Washington, D.C.

Garfield's appointment of Thomas Lemuel James to U.S. Postmaster infuriated Garfield's party rival, Stalwart Roscoe Conkling

Garfield's appointment of Thomas Lemuel James to U.S. Postmaster infuriated Garfield's party rival, Stalwart Roscoe Conkling

, who demanded a commensurate appointment for his faction and his state, such as the position of Secretary of Treasury. The resulting squabble was ponderous in the brief Garfield presidency. The feud with Conkling reached a climax when the President, at Blaine's instigation, nominated Conkling's enemy, Judge William H. Robertson

, to be Collector of the Port of New York. Conkling raised the time-honored principle of senatorial courtesy

in an attempt to defeat the nomination, but to no avail. Garfield, who believed the practice to be corrupt, would not back down and threatened to withdraw all nominations unless Robertson was included. Garfield stated this would "settle the question whether the President is registering clerk of the Senate or the Executive of the United States." Ultimately, Sen. Conkling and his junior colleague, Sen. Thomas C. Platt

, resigned their Senate seats to seek vindication, but they found only further humiliation when the New York legislature elected others in their places. Robertson was appointed and Garfield's victory on behalf of the Executive over the Senate on this issue was clear. He had routed his antagonists, weakened the principle of senatorial courtesy, and revitalized the executive branch. To Blaine's chagrin, the victorious Garfield returned to his goal of balancing the interests of party factions, and re-nominated a number of Conkling's Stalwart friends to their positions.

Former President Ulysses S. Grant, an ally of Sen. Conkling, notified President Garfield by letter that he disapproved of Blaine's nomination and staunchly opposed Garfield's appointment of Robertson as the port of New York's customs collector. President Garfield wrote Grant a stern letter in reply that stated he would not be bound by party patronage and would appoint "men who represented any valuable element in the Republican party."

By July 1, 1881, minor party dissension over the Conkling affair remained while President Garfield continued his policy of forbidding Vice President Chester A. Arthur, a Conkling ally, from attending presidential cabinet meetings. Sec. Blaine, however, encouraged and supported President Garfield. Presidential historian Justice D. Doenecke stated that Garfield lacked judgment in his appointment of Robertson that proved to be problematic. Doenecke stated that the fight over Robertson was not important enough to disturb party unity over Presidential authority since the previous customs collector, Edwin A. Merrit, appointed by President Rutherford B. Hayes in 1878, was a reformer. According to Doenecke, rather than follow his initial instinct for Republican conciliation, Garfield sided with Sec. Blaine. President Hayes had initiated the break down of Senatorial courtesy and under President Garfield the process had reached a climax.

Garfield spearheaded a notable economic achievement when he arranged for the refunding of $200 million in maturing government bonds without calling a special session of Congress. The previous interest rate of 6% on the bonds was superseded by a future rate of 3.5%, which further bolstered the government's balance sheet. This action by President Garfield, a talented economist, saved the country millions of dollars in national debt.

was damaging to the Presidency while more urgent national concerns needed to be addressed. Garfield's predecessors, Grant and Hayes, had both advocated civil service reform. By 1881, civil service reform associations had organized with renewed energy across the nation, including New York. Some reformers were disappointed that President Garfield had advocated limited tenure only to minor office seekers and had given appointments to his old friends. Many prominent reformers remained loyal and supported Garfield. Garfield advocated dismissal of incompetent incumbent

appointees.

Previously in April, 1880 there had been a Congressional investigation into corruption in the Post Office Department, where profiteering rings allegedly stole millions of dollars, employing bogus mail contracts called "star routes

". This postal corruption by the rings had stealthily succeeded for many years during both the Grant and Hayes administrations. After obtaining contracts by a low bidding procedure, known as "straw-bids", costs to run the mail routes would be escalated and profits would be divided among ring members. In 1880, Garfield's predecessor, President Hayes, stopped the implementation of any new "star route" contracts in a reform effort. In April, 1881 President Garfield was given information from Attorney General Wayne MacVeagh and Postmaster Thomas L. James of postal corruption by an alleged "star route" ringleader, Second Assistant Postmaster-General, Thomas J. Brady

. Garfield immediately demanded Brady's resignation and started prosecutions led by Postmaster James that would end in the famous "star route" indictments and trials for conspiracy. When told that his party, including his own campaign manager, Stephen W. Dorsey, was involved, Garfield directed MacVeagh and James to root out the corruption in the Post Office Department "to the bone", regardless of where it might lead. According to the New York Times, many "questionable" members allegedly involved in post office corruption were fired or resigned. Brady resigned immediately on President Garfield's demand, and was eventually indicted for conspiracy. After two "star route" ring trials in 1882 and 1883, the jury found Brady not guilty. Garfield appointed Richard A. Elmer as Brady's replacement.

had gained citizenship and suffrage that enabled them to participate in state and federal offices. Garfield believed that their rights were being eroded by southern white resistance and illiteracy, and was vitally concerned that blacks would become America's permanent "peasantry". The President's answer was to have a "universal" education system funded by the federal government. Garfield's concern over education was not exaggerated; there was a 70% illiteracy rate among southern blacks. Congress and the northern white public, however, had lost interest in African American rights. Federal funding for universal education did not pass Congress during the 1880s.

President Garfield appointed several African Americans to prominent positions: Frederick Douglas, recorder of deeds in Washington; Robert Elliot, special agent to the U.S. Treasury; John M. Langston, Haiti

an minister; and Blanche K. Bruce, register to the U.S. Treasury. Garfield began to reverse the southern Democratic conciliation

policy implemented by his predecessor, Rutherford B. Hayes. In an effort to bolster southern Republican unity Garfield appointed William H. Hunt

, a carpetbag

Republican from Louisiana during Reconstruction, as Secretary of the Navy. Garfield believed that Southern support for the Republican party could be gained by "commercial and industrial" interests rather than race issues. To break hold of the resurgent Democratic Party in the Solid South

, Garfield cautiously gave senatorial patronage privilege to Virginia Senator William Mahone

of the biracial independent Readjuster Party

. Garfield was the first Republican president to initiate an election policy to obtain support from southern independents.

general, Lew Wallace

, as U.S. minister to Turkey

. Garfield appointed Wallace to Turkey believing that the Muslim

country would serve as a good background for a second popular novel. From June 27 to July 1, 1881, President Garfield appointed 25 foreign ministers and consuls. He also appointed Sec. Blaine's son third assistant to the Secretary of State.

Garfield's Secretary of State James G. Blaine had to contend with Chinese immigration, fishing disputes with Britain, and obtaining U.S. recognition from Korea. Blaine's primary task was settling a complex international war between Chile

, Bolivia

, and Peru

that started on April 5, 1879, known as the War of the Pacific

. In January 1881, Chile's naval forces had captured the Peruvian capital city Lima. Rather than remain neutral, Blaine chose to side with Perurvian leader Fracisco G. Calderón

, who had been appointed by the Chilean government. Having concern over potential British military involvement in the war, on June 15, 1881, Blaine stressed that the conflict be resolved by consent of the Latin American countries involved and that the Peruvian government pay Chile an indemnity rather than cede the contested land. In November 1881, Blaine extended invitations to Latin American countries for a conference to meet in Washington the following November. Nine countries had accepted; however, these invitations were withdrawn in April 1882 when Congress and President Arthur, Garfield's successor, cancelled the conference. Conflicting U.S. diplomatic negotiation attempts had failed to resolve the war. In October 1883, the War of the Pacific was settled by the Treaty of Ancón

. Garfield had urged that the nation's ties to its southern neighbors be strengthened; as early as 1876, he said, "I would rather blot out five or six European missions than these South American ones...They are our neighbors and friends." Garfield continued to stress the importance of these ties in succeeding years and advocated that the Panama Canal

be constructed by the U.S. and solely under U.S. jurisdiction

.

On May 13, 1881, the Garfield Administration under Sec. Blaine negotiated a reciprocal trade treaty with queen Ranavalona II, head of the Hova tribe in Madagascar

. In return, the United States acknowledged that the Hova government had complete control over all of Madagascar.

suddenly contracted malaria and possibly spinal meningitis

. She was thought to be near death; her temperature at one time reached 104 degrees. At the end of the month, her temperature subsided and her doctor recommended she recuperate in salty air. The President loyally dedicated time at her bedside until her recovery. On June 18 the Garfields left Washington and traveled to Elberon

, New Jersey

a popular beach resort.

Unknown to Garfield, in June 1881, a rejected office seeker and Stalwart Republican supporter, Charles J. Guiteau

, had plotted to murder the President. After purchasing a .44 revolver, Guiteau obsessively stalked President Garfield at Lafayette Square Park and at Garfield's Disciples of Christ Church

in Washington. Finding out that Garfield was to leave for Elberon on June 18, Guiteau decided to assassinate the President at the Washington train depot. While at the depot Guiteau lost his will to shoot the President when he saw the poor condition of Garfield's wife.

While his wife convalesced in the cool ocean air, President Garfield brought his cabinet to Elberon for consultation and ran the government by telegraph. While staying at the Elberon Hotel, President Garfield reviewed the Seventh Regiment and then spoke with pressmen at the Ocean Hotel. Garfield was to attend a formal banquet that night in honor of the Seventh Regiment veterans at the West End Hotel. Instead he retired early, after hearing news that his 80-year-old uncle, Thomas Garfield, had been killed in a locomotive accident in Cleveland, Ohio

. Windom spoke on the President's behalf at the banquet. Former President Ulysses S. Grant, who had traveled from New York with his family, was also at Elberon. On June 25, Garfield and Grant informally greeted each other in the Elberon Hotel lobby. After attending church services, Garfield returned to Washington the following day (June 27, 1881).

and four other federal judges.

On the morning of July 2, 1881, President Garfield was on his way to his alma mater, Williams College

On the morning of July 2, 1881, President Garfield was on his way to his alma mater, Williams College

, where he was scheduled to deliver a speech. Garfield was accompanied by James G. Blaine, Robert Todd Lincoln, and his two sons, James and Harry. As the President was walking through the Sixth Street Station of the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad in Washington at 9:30 am, he was shot twice by an assassin, Charles J. Guiteau

, a disgruntled federal office-seeker armed with a .44 caliber pistol. As Guiteau was being arrested after the shooting, he repeatedly said, "I am a Stalwart of the Stalwarts! I did it and I want to be arrested! Arthur

is President now!" This very briefly led to unfounded suspicions that Arthur or his supporters had put Guiteau up to the crime.

Guiteau was upset over the rejection of his repeated attempts to be appointed as the United States consul in Paris

– a position for which he had no qualifications. He suffered from many delusions, including one that he had produced a speech which he was convinced was pivotal to Garfield's election, and another, that he was destined to be President himself.

Garfield exclaimed immediately after he was shot, "My God, what is this?" One bullet grazed Garfield's arm; the second bullet was thought later to have possibly lodged near his liver but could not be found; and upon autopsy was located behind the pancreas. Alexander Graham Bell

specifically devised a metal detector

to find the bullet, but the device's signal was distorted by the metal bed springs. Garfield became increasingly ill over a period of several weeks due to infection, which caused his heart to weaken. He remained bedridden in the White House with fever and extreme pain.

As the heat of summer became more oppressive for the stricken President, a Navy engineer, with the help of Simon Newcomb, installed in Garfield's room what may have been the world's first air conditioner. An air blower was installed over a chest containing 6 tons of ice, with the air then dried by conduction through a long iron box filled with cotton screens, and connected to the room's heat vent. This device was at times capable of reducing the air temperature to 20°F (11°C) below the outside temperature.

Sympathies for President Garfield poured out across the nation and the world. Condolences came from the King of Italy

and the Rothschilds

. Democratic Kentucky governor Luke P. Blackburn

ordered a day of "public fasting and prayer".

On September 6 the ailing President was moved to the Jersey Shore

in the vain hope that the fresh air and quiet there might aid his recovery. In a matter of hours, local residents put down a special rail spur

for Garfield's train; some of the ties are now part of the Garfield Tea House

. The beach cottage Garfield was taken to has been demolished.

On Monday, September 19, 1881, at 10:20 p.m. President Garfield suffered and died from a massive heart attack

On Monday, September 19, 1881, at 10:20 p.m. President Garfield suffered and died from a massive heart attack

and a ruptured splenic artery

aneurysm

, following blood poisoning and bronchial pneumonia

. Garfield's chief doctor, Dr. Doctor Willard Bliss

(who was a Doctor of Medicine

but whose given name

was also "Doctor"), had unsuccessfully attempted to revive the fading President with restorative medication. Mrs. Garfield, having leaned over Garfield, kissed his brow and exclaimed, "Oh! Why am I made to suffer this cruel wrong?" Garfield was pronounced dead at by Dr. Bliss in the Elberon

section of Long Branch, New Jersey

. Mrs. Garfield remained with her dead husband for over an hour until prompted to leave the room. The wounded President died exactly two months before his 50th birthday. During the 80 days between his shooting and death, his only official act was to sign an extradition

paper. His final words: "My work is done."

According to some historians and medical experts Garfield might have survived his wounds had the doctors attending him had at their disposal today's medical research, techniques, and equipment. Standard medical practice at the time dictated that priority be given to locating the path of the bullet. Several of his doctors inserted their unsterilized

fingers into the wound to probe for the bullet, a common practice in the 1880s. American doctors had not fully accepted the sterilization technique implemented by Joseph Lister

during the 1860s. Historians agree that massive infection was a significant factor in President Garfield's demise. Biographer Peskin stated that medical malpractice did not contribute to Garfield's death; the inevitable infection and blood poisoning that would ensue from a deep bullet wound resulted in multiple organ damage and spinal bone fragmentation.

Guiteau was formally indicted on October 14, 1881, for the murder of the President. Although Guiteau's counsel argued the insanity defense, due to his odd character, the jury found him guilty on January 5, 1882, and he was sentenced to death. Guiteau may have had syphilis

, a disease that causes physiological mental impairment. Guiteau was executed on June 30, 1882. He was also heard to claim that important men in Europe put him up to the task, and had promised to protect him if he were caught.

President Garfield's casket and face were viewed by 1,500 people in Long Branch before being loaded on the funeral car. As Garfield's funeral train set out, first to the Capitol and then continuing on a final leg to Cleveland for the burial, the tracks were blanketed with flowers and houses were adorned with flags. More than 70,000 citizens, some waiting over three hours, passed by his coffin as his body lay in state in Washington; later, on September 25, 1881, in Cleveland, more than 150,000—a number equal to the entire population of that city—likewise paid their respects. Garfield's body was viewed in a specially made pavilion powered by electric lighting. A wreath sent by Queen Victoria adorned Garfield's coffin. His body was temporarily interred in a vault in Cleveland's Lake View Cemetery until his permanent memorial was made.

President Garfield's casket and face were viewed by 1,500 people in Long Branch before being loaded on the funeral car. As Garfield's funeral train set out, first to the Capitol and then continuing on a final leg to Cleveland for the burial, the tracks were blanketed with flowers and houses were adorned with flags. More than 70,000 citizens, some waiting over three hours, passed by his coffin as his body lay in state in Washington; later, on September 25, 1881, in Cleveland, more than 150,000—a number equal to the entire population of that city—likewise paid their respects. Garfield's body was viewed in a specially made pavilion powered by electric lighting. A wreath sent by Queen Victoria adorned Garfield's coffin. His body was temporarily interred in a vault in Cleveland's Lake View Cemetery until his permanent memorial was made.

In 1884, a monument to President Garfield was completed by sculptor Frank Happersberger and was placed on the grounds of the San Francisco Conservatory of Flowers

. On the base of the Garfield statue is a figure holding a broken sword symbolizing Garfield's assassinantion.

On May 18, 1887, the James A. Garfield Monument

was dedicated in Washington. The monument is a 9 foot bronze statue of Garfield mounted on a 16 foot Baroque style base, located on the U.S. Capitol grounds. Three male figures, each 5 foot in height, are on the base representing Garfield's life stages as a scholar, soldier, and statesman.

In 1889, members of the California gold mining town Bodie

, commemorated Garfield's life and death by inscribing his name on a cenotaph

located in Miners Union Cemetery in Bodie. The monument had initially been made to honor W. S. Bodey, founder of the town, however, the community decided to commemorate the memorial to Garfield.

On May 19, 1890, Garfield's body was permanently interred, with great solemnity and fanfare, in a mausoleum

On May 19, 1890, Garfield's body was permanently interred, with great solemnity and fanfare, in a mausoleum

in Lake View Cemetery

in Cleveland . Attending the "impressive" dedication ceremonies were former President Rutherford B. Hayes, then current President Benjamin Harrison, and future President William McKinley. Garfield's former Sec. Windom also attended the ceremony. President Harrison stated that Garfield was always a "student and instructor" and that his life works and death would "continue to be instructive and inspiring incidents in American history". Five panels on the monument display Garfield as a teacher, Union Major General, an orator, taking the Presidential oath, and his body laying in state at the Capitol rotunda in Washington D.C from September 21, 1881 – September 23, 1881.

The U.S. has twice had three presidents in the same year. The first such year was 1841. Martin Van Buren

ended his single term, William Henry Harrison

was inaugurated and died a month later, then Vice President John Tyler

stepped into the vacant office. The second occurrence was in 1881. Rutherford B. Hayes

relinquished the office to James A. Garfield. Upon Garfield's death, Chester A. Arthur

became president.

President Garfield's murder by a deranged federal office seeker awakened public awareness and prompted Congress to pass civil service reform legislation. Senator George H. Pendleton

, a Democrat from Ohio, launched a reform effort that resulted in President Chester A. Arthur signing into law the Pendleton Act in January 1883. This act reversed the "spoils system" where office seekers paid or gave political service in order to obtain or keep federally appointed positions. Under the Pendleton Act, office appointments were awarded on merit and competitive examination. The law made illegal the long-time practice of giving money or service to obtain a federal appointment. To ensure the reform was implemented, Congress and President Arthur established and funded the Civil Service Commission

. The Pendleton Act, however, only covered 10% of federal government workers. President Arthur, who was previously known for having been a "veteran spoilsman", became an avid civil service reformer after President Garfield's assassination.

Garfield's stress on the importance of education for African Americans served as a catalyst for their advancement. As a scholar president, pre-dating Woodrow Wilson

, Garfield was an avid reader having a 3,000-book library that included Horace, Shakespeare, Goethe, Tennyson, and Froude's history of England.

In 1876, Garfield displayed his mathematical talent when he developed a trapezoid proof of the Pythagorean theorem

. His finding was placed in the New England Journal of Education. Math historian William Dunham stated that Garfield's trapezoid work was "really a very clever proof."

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

, after completing nine consecutive terms in the U.S. House of Representatives

United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is one of the two Houses of the United States Congress, the bicameral legislature which also includes the Senate.The composition and powers of the House are established in Article One of the Constitution...

. Garfield's accomplishments as President included a controversial resurgence of Presidential authority above Senatorial courtesy in executive appointments; energizing U.S. naval power; and purging corruption in the Post Office Department. Garfield made notable diplomatic and judiciary appointments, including a U.S. Supreme Court

Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest court in the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all state and federal courts, and original jurisdiction over a small range of cases...

justice. Garfield appointed several African Americans to prominent federal positions.

Garfield was a self-made man who came from a modest background, having been raised in obscurity on an Ohio farm by his widow

Widow

A widow is a woman whose spouse has died, while a widower is a man whose spouse has died. The state of having lost one's spouse to death is termed widowhood or occasionally viduity. The adjective form is widowed...

ed mother and brothers. To finance his education Garfield worked as a carpenter, and in 1856 he graduated from Williams College

Williams College

Williams College is a private liberal arts college located in Williamstown, Massachusetts, United States. It was established in 1793 with funds from the estate of Ephraim Williams. Originally a men's college, Williams became co-educational in 1970. Fraternities were also phased out during this...

, Massachusetts

Massachusetts

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States of America. It is bordered by Rhode Island and Connecticut to the south, New York to the west, and Vermont and New Hampshire to the north; at its east lies the Atlantic Ocean. As of the 2010...

. A year later, Garfield entered politics as a Republican

Republican Party (United States)

The Republican Party is one of the two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Democratic Party. Founded by anti-slavery expansion activists in 1854, it is often called the GOP . The party's platform generally reflects American conservatism in the U.S...

, after campaigning for the party's antislavery platform in Ohio. He married Lucretia Rudolph

Lucretia Garfield

Lucretia Rudolph Garfield , wife of James A. Garfield, was First Lady of the United States in 1881.-Early life:...

in 1858, and in 1860 was admitted to practice law while serving as an Ohio State Senator

Ohio Senate

The Ohio State Senate is the upper house of the Ohio General Assembly, the legislative body for the U.S. state of Ohio. There are 33 State Senators. The state legislature meets in the state capital, Columbus. The President of the Senate presides over the body when in session, and is currently Tom...

(1859–1861). Garfield opposed Confederate secession

Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America was a government set up from 1861 to 1865 by 11 Southern slave states of the United States of America that had declared their secession from the U.S...

, served as a Major General in the Union Army

Union Army

The Union Army was the land force that fought for the Union during the American Civil War. It was also known as the Federal Army, the U.S. Army, the Northern Army and the National Army...

during the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

, and fought in the battles of Middle Creek, Shiloh

Battle of Shiloh

The Battle of Shiloh, also known as the Battle of Pittsburg Landing, was a major battle in the Western Theater of the American Civil War, fought April 6–7, 1862, in southwestern Tennessee. A Union army under Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant had moved via the Tennessee River deep into Tennessee and...

and Chickamauga

Battle of Chickamauga

The Battle of Chickamauga, fought September 19–20, 1863, marked the end of a Union offensive in southeastern Tennessee and northwestern Georgia called the Chickamauga Campaign...

. He was first elected to Congress in 1863 as Representative of the 19th District of Ohio.

Throughout Garfield's extended Congressional service after the Civil War, he fervently opposed the Greenback

United States Note

A United States Note, also known as a Legal Tender Note, is a type of paper money that was issued from 1862 to 1971 in the U.S. Having been current for over 100 years, they were issued for longer than any other form of U.S. paper money. They were known popularly as "greenbacks" in their heyday, a...

, and gained a reputation as a skilled orator. He was Chairman of the Military Affairs Committee and the Appropriations Committee

United States House Committee on Appropriations

The Committee on Appropriations is a committee of the United States House of Representatives. It is in charge of setting the specific expenditures of money by the government of the United States...

and a member of the Ways and Means Committee. Garfield initially agreed with Radical Republican views regarding Reconstruction, then favored a moderate approach for civil rights enforcement for Freedmen

Freedman

A freedman is a former slave who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, slaves became freedmen either by manumission or emancipation ....

. In 1880, the Ohio legislature elected him to the U.S. Senate

United States Senate