Electoral Commission (United States)

Encyclopedia

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

presidential election of 1876. It consisted of 15 members. The election was contested by the Democratic

History of the United States Democratic Party

The history of the Democratic Party of the United States is an account of the oldest political party in the United States and arguably the oldest democratic party in the world....

ticket, Samuel J. Tilden

Samuel J. Tilden

Samuel Jones Tilden was the Democratic candidate for the U.S. presidency in the disputed election of 1876, one of the most controversial American elections of the 19th century. He was the 25th Governor of New York...

and Thomas A. Hendricks

Thomas A. Hendricks

Thomas Andrews Hendricks was an American politician who served as a Representative and a Senator from Indiana, the 16th Governor of Indiana , and the 21st Vice President of the United States...

, and the Republican ticket, Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes was the 19th President of the United States . As president, he oversaw the end of Reconstruction and the United States' entry into the Second Industrial Revolution...

and William A. Wheeler

William A. Wheeler

William Almon Wheeler was a Representative from New York and the 19th Vice President of the United States .-Early life and career:...

. Twenty electoral votes, from the states of Florida

Florida

Florida is a state in the southeastern United States, located on the nation's Atlantic and Gulf coasts. It is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the north by Alabama and Georgia and to the east by the Atlantic Ocean. With a population of 18,801,310 as measured by the 2010 census, it...

, Louisiana

Louisiana

Louisiana is a state located in the southern region of the United States of America. Its capital is Baton Rouge and largest city is New Orleans. Louisiana is the only state in the U.S. with political subdivisions termed parishes, which are local governments equivalent to counties...

, Oregon

Oregon

Oregon is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is located on the Pacific coast, with Washington to the north, California to the south, Nevada on the southeast and Idaho to the east. The Columbia and Snake rivers delineate much of Oregon's northern and eastern...

, and South Carolina

South Carolina

South Carolina is a state in the Deep South of the United States that borders Georgia to the south, North Carolina to the north, and the Atlantic Ocean to the east. Originally part of the Province of Carolina, the Province of South Carolina was one of the 13 colonies that declared independence...

, were in dispute; the resolution of these disputes would determine the outcome of the election. Facing a constitutional crisis the likes of which the nation had never seen, Congress passed a law forming the Electoral Commission to settle the result.

The Commission consisted of fifteen members: five representatives

United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is one of the two Houses of the United States Congress, the bicameral legislature which also includes the Senate.The composition and powers of the House are established in Article One of the Constitution...

, five senators

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

, and five Supreme Court justices

Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest court in the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all state and federal courts, and original jurisdiction over a small range of cases...

. Eight members were Republicans; seven were Democrats. The Commission ultimately voted along party lines to award all twenty disputed votes to Hayes, thus assuring his victory in the Electoral College by a margin of 185-184.

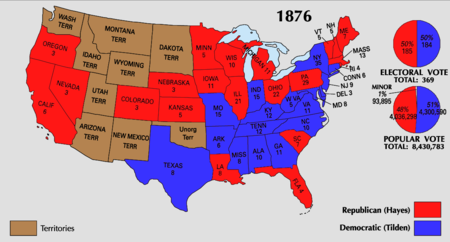

Election of 1876

The presidential election was held on November 7, 1876. Tilden carried his home state of New York and most of the South, while Hayes' strength lay in New England, the Midwest, and the West. Early returns suggested that Tilden had won the election; many major newspapers prematurely reported a Democratic victory in their morning editions. However, several other newspapers were more cautious; for example, the headline of The New York TimesThe New York Times

The New York Times is an American daily newspaper founded and continuously published in New York City since 1851. The New York Times has won 106 Pulitzer Prizes, the most of any news organization...

read: "The Results Still Uncertain." The returns in several states were tainted by allegations of electoral fraud; each side charged that ballot boxes had been stuffed, that ballots had been altered, and that voters had been intimidated.

Francis T. Nicholls

Francis Redding Tillou Nicholls was an American attorney, politician, judge, and a brigadier general in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War...

. This rival administration, in turn, certified that Tilden had won.

A nearly identical scenario played out in South Carolina, where initial returns suggested that Hayes had won the presidential election, while the Democratic Party had triumphed in the gubernatorial contest. Here, too, the Republican-controlled returning board discounted several votes, ensuring the election of a Republican Governor and Legislature. As in Louisiana, the Democratic Party organized a rival state government, under the leadership of Wade Hampton III

Wade Hampton III

Wade Hampton III was a Confederate cavalry leader during the American Civil War and afterward a politician from South Carolina, serving as its 77th Governor and as a U.S...

. Hampton's government declared Tilden the victor in the presidential election.

Similar problems arose in Florida. The initial count showed Hayes ahead by 43 votes, but after a correction was made, Tilden took a lead of 94 votes. Subsequently, the returning board disallowed numerous ballots, delivering the election to Hayes by nearly a thousand votes. The board also declared that the Republican candidate had won the gubernatorial election; however, the Florida Supreme Court overruled them, instead awarding the victory to Democrat George Franklin Drew

George Franklin Drew

George Franklin Drew was the 12th Governor of the U.S. state of Florida.Born in Alton, New Hampshire, he moved to the south, opening a machine shop in Columbus, Georgia in 1847. In 1865, he opened the largest sawmill in Florida in Ellaville...

. Drew then announced that Tilden, not Hayes, had carried Florida.

Further complications arose in Oregon. Although both sides acknowledged that Hayes had won the state, Tilden's supporters questioned the constitutional eligibility of John W. Watts, one of the Hayes electors. The Constitution provides that "no…person holding an office of trust or profit under the United States shall be appointed an elector." Watts was a United States postmaster

Postmaster

A postmaster is the head of an individual post office. Postmistress is not used anymore in the United States, as the "master" component of the word refers to a person of authority and has no gender quality...

; however, he resigned from his office a week after the election, long before the scheduled meeting of the Electoral College. Nevertheless, the state's Democratic Governor, LaFayette Grover, removed Watts as an elector, replacing him with C. A. Cronin (a Tilden supporter).

On December 6, 1876, the electors met in the state capitals to cast their ballots. In Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina, both the Democratic and the Republican slates of electors assembled, and cast conflicting votes. In Oregon, likewise, both Watts and Cronin cast ballots. Thus, from each of these four states, two sets of returns were transmitted to Washington.

Tilden had won the popular vote by almost a quarter of a million votes, but he did not have a clear Electoral College majority. He received 184 uncontested electoral votes, while Hayes received 165, with both sides claiming the remaining twenty (4 from Florida, 8 from Louisiana, 7 from South Carolina, and 1 from Oregon). A total of 185 votes constituted an Electoral College majority; hence, Tilden needed only one of the disputed votes, while Hayes needed all twenty.

Electoral Commission Act

The election dispute gave rise to a constitutional crisisConstitutional crisis

A constitutional crisis is a situation that the legal system's constitution or other basic principles of operation appear unable to resolve; it often results in a breakdown in the orderly operation of government...

. Many Democrats who believed that they had been cheated threatened: "Tilden or War!" Congressman Henry Watterson

Henry Watterson

Henry Watterson was a United States journalist who founded the Louisville Courier-Journal.He also served part of one term in the United States House of Representatives as a Democrat....

of Kentucky declared that an army of 100,000 men was prepared to march on Washington if Tilden was denied the presidency. Since the Constitution did not explicitly indicate how Electoral College disputes were to be resolved, Congress was forced to consider other methods to settle the crisis. Many Democrats argued that Congress as a whole should determine which certificates to count. However, the chances that this method would result in a harmonious settlement were slim, as the Democrats controlled the House, while the Republicans controlled the Senate. Several Hayes supporters, on the other hand, argued that the President pro tempore of the Senate had the authority to determine which certificates to count, because he was responsible for chairing the congressional session at which the electoral votes were to be tallied. Since the office of President pro tempore was occupied by a Republican, Senator Thomas W. Ferry

Thomas W. Ferry

Thomas White Ferry was a U.S. Representative and U.S. Senator from the state of Michigan.Ferry was born in the old Mission House on Mackinac Island. The community on Mackinac at that time included the military garrison, the main depot of John Jacob Astor's American Fur Company, and the mission....

of Michigan, this method would have favored Hayes. Still others proposed that the matter should be settled by the Supreme Court.

In late December, each House created a special committee charged with developing a mechanism to resolve the issue. The committees ultimately settled upon creating an Electoral Commission. Many Republicans objected to the idea, insisting that the President pro tempore should resolve the disputes himself. Rutherford Hayes charged that the bill was unconstitutional. However, a sufficient number of Republicans joined the Democrats to ensure the legislation's passage. On January 25, 1877, the Senate voted in favor of the Electoral Commission Bill 47-17; the House followed suit the next day, 191-86. On January 29, President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant was the 18th President of the United States as well as military commander during the Civil War and post-war Reconstruction periods. Under Grant's command, the Union Army defeated the Confederate military and ended the Confederate States of America...

signed the bill into law.

Under the new legislation, the Electoral Commission was to consist of fifteen members: five representatives selected by the House, five senators selected by the Senate, four Supreme Court justices named in the law, and a fifth Supreme Court justice selected by the other four. The most senior justice was to serve as President of the Commission. Whenever two different electoral vote certificates arrived from any state, the Commission was empowered to determine which return was correct. The Commission's decisions could be only overturned by both houses of Congress.

Membership of the Commission

Originally, it was planned that the Commission would consist of seven Democrats, seven Republicans, and one independent. Justice David Davis, who was widely regarded as a political independent, was supposed to be the fifth justice on the Commission. According to one historian, "[n]o one, perhaps not even Davis himself, knew which presidential candidate he preferred." Just as the Electoral Commission Bill was passing Congress, the Legislature of IllinoisIllinois

Illinois is the fifth-most populous state of the United States of America, and is often noted for being a microcosm of the entire country. With Chicago in the northeast, small industrial cities and great agricultural productivity in central and northern Illinois, and natural resources like coal,...

elected Davis to the Senate. Democrats in the Illinois Legislature believed that they had purchased Davis' support by voting for him. However, they had made a miscalculation; instead of staying on the Supreme Court so that he could serve on the Commission, he promptly resigned as a Justice in order to take his Senate seat.

With no independents left on the Supreme Court, the final seat on the Electoral Commission was given instead to Justice Joseph Philo Bradley

Joseph Philo Bradley

Joseph Philo Bradley was an American jurist best known for his service on the United States Supreme Court, and on the Electoral Commission that decided the disputed 1876 presidential election.-Early life:...

, a Republican. As a result, the GOP held a one-seat majority on the body. Bradley would, in every case, vote with his fellow Republicans to give the disputed electoral votes to Hayes.

The membership of the Commission was as follows:

| Member | |Party | |

|---|---|---|

| Thomas F. Bayard Thomas F. Bayard Thomas Francis Bayard was an American lawyer and politician from Wilmington, Delaware. He was a member of the Democratic Party, who served three terms as U.S. Senator from Delaware, and as U.S. Secretary of State, and U.S. Ambassador to the United Kingdom.-Early life and family:Bayard was born in... (Delaware Delaware Delaware is a U.S. state located on the Atlantic Coast in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It is bordered to the south and west by Maryland, and to the north by Pennsylvania... ) |

Senate | Democrat |

| Allen G. Thurman Allen G. Thurman Allen Granberry Thurman was a Democratic Representative and Senator from Ohio, as well as the nominee of the Democratic Party for Vice President of the United States in 1888.-Biography:... (Ohio Ohio Ohio is a Midwestern state in the United States. The 34th largest state by area in the U.S.,it is the 7th‑most populous with over 11.5 million residents, containing several major American cities and seven metropolitan areas with populations of 500,000 or more.The state's capital is Columbus... ) |

Senate | Democrat |

| George F. Edmunds George F. Edmunds George Franklin Edmunds was a Republican U.S. Senator from Vermont from 1866 to 1891.Born in Richmond, Vermont, Edmunds attended common schools and was privately tutored as a child. After being admitted to the bar in 1849, he started a law practice in Burlington, Vermont... (Vermont Vermont Vermont is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States of America. The state ranks 43rd in land area, , and 45th in total area. Its population according to the 2010 census, 630,337, is the second smallest in the country, larger only than Wyoming. It is the only New England... ) |

Senate | Republican |

| Frederick T. Frelinghuysen Frederick T. Frelinghuysen Frederick Theodore Frelinghuysen was a member of the United States Senate representing New Jersey and a United States Secretary of State.-Early life and education:... (New Jersey New Jersey New Jersey is a state in the Northeastern and Middle Atlantic regions of the United States. , its population was 8,791,894. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York, on the southeast and south by the Atlantic Ocean, on the west by Pennsylvania and on the southwest by Delaware... ) |

Senate | Republican |

| Oliver Hazard Perry Morton Oliver Hazard Perry Morton Oliver Hazard Perry Throck Morton , commonly known as Oliver P. Morton, was a U.S. Republican Party politician from Indiana. He served as the 14th Governor of Indiana during the American Civil War, and was a stalwart ally of President Abraham Lincoln. During the war, Morton suppressed the... (Indiana Indiana Indiana is a US state, admitted to the United States as the 19th on December 11, 1816. It is located in the Midwestern United States and Great Lakes Region. With 6,483,802 residents, the state is ranked 15th in population and 16th in population density. Indiana is ranked 38th in land area and is... ) |

Senate | Republican |

| Josiah Gardner Abbott Josiah Gardner Abbott Josiah Gardner Abbott was an American politician who served in the Massachusetts General Court and as a member of the United States House of Representatives from Massachusetts.... (Massachusetts Massachusetts The Commonwealth of Massachusetts is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States of America. It is bordered by Rhode Island and Connecticut to the south, New York to the west, and Vermont and New Hampshire to the north; at its east lies the Atlantic Ocean. As of the 2010... ) |

House | Democrat |

| Eppa Hunton Eppa Hunton Eppa Hunton II was a U.S. Representative and Senator from Virginia and a brigadier general in the Confederate Army during the American Civil War.-Early years:... (Virginia Virginia The Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there... ) |

House | Democrat |

| Henry B. Payne Henry B. Payne Henry B. Payne was a Democratic politician from Ohio. He served in both houses of the United States Congress.... (Ohio Ohio Ohio is a Midwestern state in the United States. The 34th largest state by area in the U.S.,it is the 7th‑most populous with over 11.5 million residents, containing several major American cities and seven metropolitan areas with populations of 500,000 or more.The state's capital is Columbus... ) |

House | Democrat |

| James A. Garfield (Ohio Ohio Ohio is a Midwestern state in the United States. The 34th largest state by area in the U.S.,it is the 7th‑most populous with over 11.5 million residents, containing several major American cities and seven metropolitan areas with populations of 500,000 or more.The state's capital is Columbus... ) |

House | Republican |

| George Frisbie Hoar George Frisbie Hoar George Frisbie Hoar was a prominent United States politician and United States Senator from Massachusetts. Hoar was born in Concord, Massachusetts... (Massachusetts Massachusetts The Commonwealth of Massachusetts is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States of America. It is bordered by Rhode Island and Connecticut to the south, New York to the west, and Vermont and New Hampshire to the north; at its east lies the Atlantic Ocean. As of the 2010... ) |

House | Republican |

| Nathan Clifford Nathan Clifford Nathan Clifford was an American statesman, diplomat and jurist.Clifford was born of old Yankee stock in Rumney, New Hampshire, to farmers, the only son of seven children He attended the public schools of that town, then the Haverhill Academy in New... * (Maine Maine Maine is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States, bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the east and south, New Hampshire to the west, and the Canadian provinces of Quebec to the northwest and New Brunswick to the northeast. Maine is both the northernmost and easternmost... ) |

Supreme Court | Democrat |

| Stephen Johnson Field Stephen Johnson Field Stephen Johnson Field was an American jurist. He was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court of the United States Supreme Court from May 20, 1863, to December 1, 1897... (California California California is a state located on the West Coast of the United States. It is by far the most populous U.S. state, and the third-largest by land area... ) |

Supreme Court | Democrat |

| Joseph Philo Bradley Joseph Philo Bradley Joseph Philo Bradley was an American jurist best known for his service on the United States Supreme Court, and on the Electoral Commission that decided the disputed 1876 presidential election.-Early life:... (New Jersey New Jersey New Jersey is a state in the Northeastern and Middle Atlantic regions of the United States. , its population was 8,791,894. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York, on the southeast and south by the Atlantic Ocean, on the west by Pennsylvania and on the southwest by Delaware... ) |

Supreme Court | Republican |

| Samuel Freeman Miller Samuel Freeman Miller Samuel Freeman Miller was an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court from 1862–1890. He was a physician and lawyer.-Early life and education:... (Iowa Iowa Iowa is a state located in the Midwestern United States, an area often referred to as the "American Heartland". It derives its name from the Ioway people, one of the many American Indian tribes that occupied the state at the time of European exploration. Iowa was a part of the French colony of New... ) |

Supreme Court | Republican |

| William Strong William Strong (judge) William Strong was an American jurist and politician. He was a justice on the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania and an Associate Justice on the Supreme Court of the United States.-Early life:... (Pennsylvania Pennsylvania The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania is a U.S. state that is located in the Northeastern and Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States. The state borders Delaware and Maryland to the south, West Virginia to the southwest, Ohio to the west, New York and Ontario, Canada, to the north, and New Jersey to... ) |

Supreme Court | Republican |

| * President of the Electoral Commission | ||

Proceedings of the Commission

The Electoral Commission held its meetings in the Supreme Court chamber. It sat in the same manner as a court, hearing arguments from both Democratic and Republican lawyers. Tilden was represented by Jeremiah S. BlackJeremiah S. Black

Jeremiah Sullivan Black was an American statesman and lawyer. He was the son of Representative Henry Black, and the father of writer and Lieutenant Governor of Pennsylvania Chauncey Forward Black....

, Montgomery Blair

Montgomery Blair

Montgomery Blair , the son of Francis Preston Blair, elder brother of Francis Preston Blair, Jr. and cousin of B. Gratz Brown, was a politician and lawyer from Maryland...

, John Archibald Campbell

John Archibald Campbell

John Archibald Campbell was an American jurist.Campbell was born near Washington, Georgia, to Col. Duncan Greene Campbell...

, Matthew H. Carpenter

Matthew H. Carpenter

Matthew Hale Carpenter , was a member of the Republican Party who served in the United States Senate for the state of Wisconsin from 1869–1875 and again from 1879 - 1881....

, Ashbel Green

Ashbel Green

Ashbel Green, D.D. was an American Presbyterian minister and academic.Born in Hanover Township, New Jersey, Green served as a sergeant of the New Jersey militia during the American Revolutionary War, and went on to study with Dr. John Witherspoon and graduate as valedictorian from Princeton...

, George Hoadley, Richard T. Merrick

Richard T. Merrick

Richard Thomas Merrick was a lawyer and Democratic political figure.Born in Charles County, Maryland, Merrick was the son of William D. Merrick, a member of the Maryland legislature and the United States Senate. His brother, William M. Merrick, was a federal judge and congressman from Maryland...

, Charles O'Conor

Charles O'Conor

Charles O'Conor was an American lawyer who ran in the U.S. presidential election, 1872.-Biography:...

, Lyman Trumbull

Lyman Trumbull

Lyman Trumbull was a United States Senator from Illinois during the American Civil War, and co-author of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.-Education and early career:...

, and William C. Whitney

William C. Whitney

William Collins Whitney was an American political leader and financier and founder of the prominent Whitney family. He served as Secretary of the Navy in the first Cleveland administration from 1885 through 1889. A conservative reformer, he was considered a Bourbon Democrat.-Early life:William...

. Hayes was represented by William M. Evarts

William M. Evarts

William Maxwell Evarts was an American lawyer and statesman who served as U.S. Secretary of State, U.S. Attorney General and U.S. Senator from New York...

, Stanley Matthews, Samuel Shellabarger, and E. W. Stoughton.

The tribunal began hearing arguments on February 1, 1877. Tilden's lawyers argued that the Commission should investigate the actions of the state returning boards, and reverse those actions if necessary. Hayes' counsel, on the other hand, suggested that the Commission should merely accept the official returns certified by the state Governor without inquiring into their validity. To do otherwise, it was argued, would have violated the sovereignty of the states. The Commission voted 8-7, along party lines, in favor of the Republican position.

Subsequently, in a series of party-line votes, the Commission awarded all twenty disputed electoral votes to Hayes. Under the Electoral Commission Act, the Commission's findings were final unless overruled by both houses of Congress. Although the Democrat-controlled House of Representatives repeatedly voted to reject the Commission's decisions, the Republican-controlled Senate voted to uphold them. Thus, Hayes' victory was assured.

Democratic National Committee

The Democratic National Committee is the principal organization governing the United States Democratic Party on a day to day basis. While it is responsible for overseeing the process of writing a platform every four years, the DNC's central focus is on campaign and political activity in support...

, made a spurious challenge to the electoral votes from Vermont

Vermont

Vermont is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States of America. The state ranks 43rd in land area, , and 45th in total area. Its population according to the 2010 census, 630,337, is the second smallest in the country, larger only than Wyoming. It is the only New England...

, even though Hayes had clearly carried the state. The two houses then separated to consider the objection. The Senate quickly voted to overrule the objection, but the Democrats conducted a filibuster in the House of Representatives. In a stormy session that began on March 1, 1877, the House debated the objection for about twelve hours before overruling it. Immediately, another spurious objection was raised, this time to the electoral votes from Wisconsin

Wisconsin

Wisconsin is a U.S. state located in the north-central United States and is part of the Midwest. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake Michigan to the east, Michigan to the northeast, and Lake Superior to the north. Wisconsin's capital is...

. Again, the Senate voted to overrule the objection, while a filibuster was conducted in the House. However, the Speaker of the House, Democrat Samuel J. Randall

Samuel J. Randall

Samuel Jackson Randall was a Pennsylvania politician, attorney, soldier, and a prominent Democratic member of the United States House of Representatives during the late 19th century. He served as the 33rd Speaker of the House and a contender for his party's nomination for the President of the...

, refused to entertain dilatory motions. Eventually, the filibusterers gave up, allowing the House to reject the objection in the early hours of March 2. The House and Senate then reassembled to complete the count of the electoral votes. At 4:10 AM on March 2, Senator Ferry announced that Hayes and Wheeler had been elected to the presidency and vice presidency, by an electoral margin of 185-184.

Some historians have argued that Democrats and Republicans reached an unwritten agreement (known as the Compromise of 1877

Compromise of 1877

The Compromise of 1877, also known as the Corrupt Bargain, refers to a purported informal, unwritten deal that settled the disputed 1876 U.S. Presidential election and ended Congressional Reconstruction. Through it, Republican Rutherford B. Hayes was awarded the White House over Democrat Samuel J...

) under which the filibuster would be dropped in return for a promise to end Reconstruction. This thesis was most notably advanced by C. Vann Woodward in his 1951 book, Reunion and Reaction. Other historians, however, have argued that no such compromise existed.

Aftermath

Many of Tilden's supporters believed that he had been cheated out of victory. Hayes was variously dubbed "Rutherfraud," "His Fraudulency," and "His Accidency." On March 3, the House of Representatives went so far as to pass a resolution declaring its opinion that Tilden had been "duly elected President of the United States." Nevertheless, Hayes was peacefully sworn in as President on March 5. Many historians have complained that, after entering office, Hayes rewarded those who helped him win the election dispute with federal offices. Most notably, one of the lawyers who argued Hayes' case before the Electoral Commission, William M. Evarts, was appointed Secretary of StateUnited States Secretary of State

The United States Secretary of State is the head of the United States Department of State, concerned with foreign affairs. The Secretary is a member of the Cabinet and the highest-ranking cabinet secretary both in line of succession and order of precedence...

. Another, Stanley Matthews

Thomas Stanley Matthews

Thomas Stanley Matthews , known as Stanley Matthews, was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court, serving from May 1881 to his death in 1889. Matthews was the Court's 46th justice...

, was nominated to the Supreme Court.

In May 1878, the House of Representatives created a special committee charged with investigating the allegations of fraud in the 1876 election. The eleven-member committee was chaired by Clarkson Nott Potter

Clarkson Nott Potter

Clarkson Nott Potter was an American civil engineer, then a practising lawyer in New York City, and in 1869-1875 and in 1877-1881 a Democratic member of the United States House of Representatives. He was President of the American Bar Association from 1881 to 1882.-Family:Potter was the son of...

, a Democratic congressman from New York. The committee, however, could not uncover any evidence of wrongdoing by the President. At approximately the same time, the New York Tribune published a series of coded telegrams that Democratic Party operatives had sent during the weeks following the 1876 election. These telegrams revealed attempts to bribe election officials in states with disputed results. Despite attempts to implicate him in the scandal, Samuel Tilden was declared innocent by the Potter Committee.

To prevent a repetition of the 1876 debacle, Congress passed the Electoral Count Act in 1887. Under this law, 3 U.S.C. § 5, a state's determination of electoral disputes is conclusive in most circumstances. The President of the Senate opens the electoral certificates in the presence of both houses, and hand them to the tellers, two from each house, who are to read them aloud and record the votes. If the same state sends multiple returns to Congress, then whichever return has been certified by the executive of the state is counted, unless both houses of Congress decide otherwise. The interpretation of this act was the subject of controversy in Bush v. Gore

Bush v. Gore

Bush v. Gore, , is the landmark United States Supreme Court decision on December 12, 2000, that effectively resolved the 2000 presidential election in favor of George W. Bush. Only eight days earlier, the United States Supreme Court had unanimously decided the closely related case of Bush v...

, a case relating to the disputed presidential election of 2000.

Additional reading

- Oldaker, Nikki with John Bigelow, (2006). "Samuel Tilden the Real 19th President" Elected by the Peoples' Votes.

- Ewing, Elbert W. R. (1910). History and Law of the Hayes-Tilden Contest Before the Electoral Commission: The Florida Case, 1876-1877. Washington: Cobden Pub. Co.

- Haworth, Paul Leland. (1906). The Hayes-Tilden Disputed Election of 1876. Cleveland: Burrow Bros.

- Robinson, Lloyd. (1968). The Stolen Election: Hayes Versus Tilden 1876. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Co.

- Polakoff, Keith Ian. (1973). The Politics of Inertia: The Election of 1876 and the End of Reconstruction. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

- Woodward, C. Vann. (1951). Reunion and Reaction: The Compromise of 1877 and the End of Reconstruction. Boston: Little, Brown, and Co.

- U.S. Electoral Commission. (1877). Electoral Count of 1877. Proceedings of the Electoral Commission and of the Two Houses of Congress in Joint Meeting Relative to the Count of Electoral Votes Cast December 6, 1876, for the Presidential Term Commencing March 4, 1877. 44th Cong. 2d Sess. Washington: GPO.