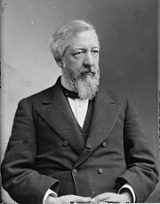

James G. Blaine

Encyclopedia

James Gillespie Blaine was a U.S. Representative

, Speaker of the United States House of Representatives

, U.S. Senator

from Maine

, two-time Secretary of State

. He was nominated for president in 1884, but lost a close race to Democrat Grover Cleveland

.

Blaine was a dominant Republican leader of the late 19th century, and champion of the "Half-Breed"

faction of the GOP. Nicknamed "The Continental Liar From the State of Maine," "Slippery Jim," and "The Magnetic Man," he was a magnetic speaker in an era that prized oratory, and a man of charisma. As a moderate Republican he supported President Abraham Lincoln

during the Civil War. As a major leader during Reconstruction he took an independent course in his advocacy of black suffrage, but opposed the coercive measures of the Radical Republicans during the administration of Ulysses S. Grant

. He opposed a general amnesty bill, secured the support of the Union veterans who mobilized as the Grand Army of the Republic

, worked for a reduction in the tariff and generally sought and obtained strong support from the western states. Railroad promotion and construction were important in this period, and as a result of his interest and support Blaine was charged with graft and corruption in the awarding of railroad charters. The proof or falsity of the charges was supposed to rest in the so-called "Mulligan letters," which Blaine refused to release to the public, but from which he read in his controversial defense in the House.

, Washington County, Pennsylvania

, near Pittsburgh

. His parents were Ephraim Lyon Blaine and his wife Maria Gillespie. The Blaines were Scots-Irish American

s. The Gillespie women, however, were ardent Irish Catholics, with a close relationship to Notre Dame University. According to Blaine's entry in the "Representative Men of Maine" (1893), "Ephraim L. was an intellectual

, an educated, and, in many respects, a brilliant man, but he was not regarded as a practical man. He was a graduate of Washington College

. He was a member of the Washington Literary Society at Washington College

. In 1820 he married Maria Gillespie, a granddaughter of Neal Gillespie, who came to America from the north of Ireland

in 1771. The husband was a Presbyterian and the wife a Roman Catholic. His paternal grandfather was named James Blaine, a local justice of the peace in Brownsville. His paternal great-grandfather Col. Ephraim Blaine (1741–1804), served in the Continental Army

during the American Revolution

, from 1778 to 1782 as commissary-general of the Northern Department.

, in 1847, where he was a member of the Delta Kappa Epsilon

fraternity

(Theta chapter). Subsequently, Blaine taught at the Western Military Institute

in Blue Lick Springs, Kentucky, and from 1852 to 1854, he taught at the Pennsylvania Institution for the Blind in Philadelphia

. During this period, also, he studied law. Blaine married Harriet Stanwood on June 30, 1850. The couple had numerous children, including sons James G. Blaine, Jr. and Walker Blaine

.

His oldest son Emmons Blaine married Anita McCormick, daughter of Cyrus McCormick

on September 26, 1889, but died less than three years later on June 18, 1892.

After settling in Augusta, Maine

, in 1854, he became editor of the Kennebec Journal

, and subsequently on the Portland Advertiser.

He soon abandoned editorial work for a more active public career. He served as a member in the Maine House of Representatives

from 1859 to 1862, serving the last two years as speaker

. He also became chairman of the Republican state committee

in 1859, and for more than 20 years personally directed every campaign of his party. Among Blaine's admirers, he was known as the "Plumed Knight."

Blaine was elected as a Republican to the 38th United States Congress

Blaine was elected as a Republican to the 38th United States Congress

and to the six succeeding U.S. Congresses and served from March 4, 1863, to July 10, 1876, when he resigned. He was Speaker of the House

for three terms—during the 41st

through 43rd United States Congress

es. He served as chairman of the Rules Committee

during the 43rd through 45th United States Congress

es, followed by over four years in the Senate

.

was substantially Blaine's proposition.

Blaine opposed the scheme of military governments for the Southern states supported by the Radical Republicans, insisting there be a clear path by which they could release themselves from military rule and resume civil government. He was the first in Congress to oppose the claim, which gained momentary and widespread favor in 1867, that the public debt, pledged in coin, should be paid in greenback

Blaine opposed the scheme of military governments for the Southern states supported by the Radical Republicans, insisting there be a clear path by which they could release themselves from military rule and resume civil government. He was the first in Congress to oppose the claim, which gained momentary and widespread favor in 1867, that the public debt, pledged in coin, should be paid in greenback

s. He took up the cause of naturalized American citizens who, on return to their native land, were subject to prosecution on charges of disloyalty. His work led to the treaty of 1870 between the United States and Britain, which placed adopted and native citizens on the same footing.

, Blaine proposed the Blaine Amendment

, a constitutional amendment that would prohibit the use of public funds by any religious school. It never passed Congress but a majority of states subsequently adopted similar laws. Catholics denounced the Blaine Amendment as anti-Catholic

Catholics denounced the Blaine Amendment as anti-Catholic

. It was strongly supported by Protestants, especially Methodists

, Baptists and Congregationalists

. Blaine, who actively sought Catholic votes when he ran for president in 1884, believed that his amendment would forestall the danger of bitter and divisive agitation on the question.

, United States presidential election, 1880

.) His chance for securing the 1876 nomination, however, was damaged by persistent charges that as a member of Congress he had been guilty of corruption in his relations with the Little Rock & Fort Smith Railway and the Northern Pacific Railway

. By the majority of Republicans, he was considered to have cleared himself completely, and he missed the nomination for President by only 28 votes at the Republican National Convention

, being finally beaten by a combination of supporters of all the other candidates going to dark horse nominee

Rutherford B. Hayes

. He was mocked by political opponents as "Blaine, Blaine, James G. Blaine, the continental liar from the State of Maine!"

in a brilliant speech that made Ingersoll famous, extolling him as the "Plumed Knight:"

The rivalries between Blaine's "Half Breeds" and Stalwarts (Grant supporters) was so strong that a compromise candidate, Rutherford B. Hayes

of Ohio, was chosen in 1876 and then elected in a highly controversial election that ended in the Compromise of 1877

and the end of Reconstruction.

inflation, now resisted depreciated silver

coinage. He championed the advancement of American shipping, and advocated generous subsidies

, insisting that the policy of protection should be applied on sea as well as on land.

Blaine was re-elected and served from July 10, 1876, to March 5, 1881, when he resigned to become Secretary of State

. While in the Senate, he held the minor chairmanships of the U.S. Senate Committee on Civil Service and Retrenchment (45th Congress) and U.S. Senate Committee on Rules (also 45th Congress). During this period he tried again for a Presidential nomination: the Republican National Convention of 1880, divided between the two nearly equal forces of Blaine and former President Ulysses Grant — John Sherman

of Ohio

also having a considerable following — struggled through 36 ballots, when the friends of Blaine, combining with those of Sherman, succeeded in nominating James A. Garfield.

; later, when he took the same job in President Benjamin Harrison

's Cabinet, he became the second and last person to hold this position in two non-consecutive terms. After Garfield's death on September 19, 1881, Arthur asked all of the cabinet members to postpone their resignations until Congress recessed that December. Blaine initially agreed but changed his mind in mid-October and left office December 19. During his two months under Arthur, Blaine dedicated his time to forging his own achievements in an attempt to improve his chances in the 1884 presidential election. In June 1884, he was nominated to run for president by his party on the fourth ballot at the 1884 Republican National Convention

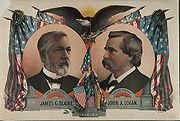

.

He was the unsuccessful Republican nominee for President in 1884; he was the only nonincumbent Republican nominee to lose a presidential race between 1860 and 1912, and only the second Republican Presidential nominee to lose at all. Republican reformers, called "Mugwumps", supported Cleveland because of Blaine's reputation for corruption. After heated canvassing, he lost by a narrow margin in New York

. Many, including Blaine himself, attributed his defeat to the effect of a phrase, "Rum, Romanism and Rebellion

", used by a Protestant clergyman, the Rev. Samuel D. Burchard, on October 29, 1884, in Blaine's presence, to characterize what, in his opinion, the Democrats

stood for. "Rum" meant the liquor interest; "Romanism" meant Catholics; "Rebellion" meant Confederates

in 1861.

The phrase was not Blaine's, but his opponents made use of it to characterize his hostility toward Catholics, some of whom probably did switch their vote. Blaine's mother was a Roman Catholic of Irish

descent and his sister was a nun

, and speculation was that he might gain votes from a heavily Democratic group. However, Catholics were already suspicious of Blaine over his support of the Blaine Amendments.

become the GOP nominee in 1888; in 1889 President Harrison appointed Blaine his Secretary of State.

He upheld American rights in Samoa

He upheld American rights in Samoa

, pursued a vigorous diplomacy with Italy over the lynching of 11 Italians accused of being Mafiosi who murdered the police chief in New Orleans in 1891, held a firm attitude during the strained relations between the United States and Chile

over a deadly barroom brawl involving sailors from the USS Baltimore

; and carried on with Britain a controversy over the seal fisheries of Bering Sea

—a difference afterward settled by arbitration

. Blaine sought to secure a modification of the Clayton–Bulwer Treaty, and in an extended correspondence with the British government strongly asserted the policy of an exclusive American control of any isthmian canal which might be built to connect the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

In foreign policy Blaine was a transitional figure, marking the end of one era in foreign policy and foreshadowing the next. He brought energy, imagination and verve to the office in sharp contrast with his somnolent rivals, inspiring his activist twentieth-century successors. He was a pioneer in arbitration treaties, tariff reciprocity, and American administration of Latin American customs houses to avert civil wars over the revenue stream. Blaine wanted the U.S. to be the protector and leader of the Western Hemisphere, even if the Latin America countries disagreed. He insisted on keeping the Americas away from European control while favoring peaceful arbitration and negotiations rather than war. Blaine forcefully argued for the national interests of his country. He kept the big picture firmly in mind, seeking long-term programs and not simply short-term fixes for the matter at hand.

Blaine played a role in founding Bates College

in Lewiston, Maine

, and he served as a longtime trustee (1863–1893) of the college; he was given an honorary degree from Bates in 1869.

In late 1892 Blaine's health failed rapidly and he died four days shy of his 63rd birthday in Washington, D.C. at the age of 62 of a heart attack. He was interred in Oak Hill Cemetery. Reinterment took place in the Blaine Memorial Park, Augusta, Maine

, in June 1920.

}

}}

United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is one of the two Houses of the United States Congress, the bicameral legislature which also includes the Senate.The composition and powers of the House are established in Article One of the Constitution...

, Speaker of the United States House of Representatives

Speaker of the United States House of Representatives

The Speaker of the United States House of Representatives, or Speaker of the House, is the presiding officer of the United States House of Representatives...

, U.S. Senator

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

from Maine

Maine

Maine is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States, bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the east and south, New Hampshire to the west, and the Canadian provinces of Quebec to the northwest and New Brunswick to the northeast. Maine is both the northernmost and easternmost...

, two-time Secretary of State

United States Secretary of State

The United States Secretary of State is the head of the United States Department of State, concerned with foreign affairs. The Secretary is a member of the Cabinet and the highest-ranking cabinet secretary both in line of succession and order of precedence...

. He was nominated for president in 1884, but lost a close race to Democrat Grover Cleveland

Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland was the 22nd and 24th president of the United States. Cleveland is the only president to serve two non-consecutive terms and therefore is the only individual to be counted twice in the numbering of the presidents...

.

Blaine was a dominant Republican leader of the late 19th century, and champion of the "Half-Breed"

Half-Breed (politics)

The "Half-Breeds" were a political faction of the United States Republican Party that existed in the late 19th century. The Half-Breeds were a moderate-wing group, and they were the opponents of the Stalwarts, the other main faction of the Republican Party. The main issue that separated the...

faction of the GOP. Nicknamed "The Continental Liar From the State of Maine," "Slippery Jim," and "The Magnetic Man," he was a magnetic speaker in an era that prized oratory, and a man of charisma. As a moderate Republican he supported President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. He successfully led his country through a great constitutional, military and moral crisis – the American Civil War – preserving the Union, while ending slavery, and...

during the Civil War. As a major leader during Reconstruction he took an independent course in his advocacy of black suffrage, but opposed the coercive measures of the Radical Republicans during the administration of Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant was the 18th President of the United States as well as military commander during the Civil War and post-war Reconstruction periods. Under Grant's command, the Union Army defeated the Confederate military and ended the Confederate States of America...

. He opposed a general amnesty bill, secured the support of the Union veterans who mobilized as the Grand Army of the Republic

Grand Army of the Republic

The Grand Army of the Republic was a fraternal organization composed of veterans of the Union Army, US Navy, US Marines and US Revenue Cutter Service who served in the American Civil War. Founded in 1866 in Decatur, Illinois, it was dissolved in 1956 when its last member died...

, worked for a reduction in the tariff and generally sought and obtained strong support from the western states. Railroad promotion and construction were important in this period, and as a result of his interest and support Blaine was charged with graft and corruption in the awarding of railroad charters. The proof or falsity of the charges was supposed to rest in the so-called "Mulligan letters," which Blaine refused to release to the public, but from which he read in his controversial defense in the House.

Family

Blaine was born in West BrownsvilleWest Brownsville, Pennsylvania

West Brownsville is a borough in Washington County, Pennsylvania, United States. The population was 1,075 at the 2000 census.-Geography:West Brownsville is located at ....

, Washington County, Pennsylvania

Washington County, Pennsylvania

-Government and politics:As of November 2008, there are 152,534 registered voters in Washington County .* Democratic: 89,027 * Republican: 49,025 * Other Parties: 14,482...

, near Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Pittsburgh is the second-largest city in the US Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and the county seat of Allegheny County. Regionally, it anchors the largest urban area of Appalachia and the Ohio River Valley, and nationally, it is the 22nd-largest urban area in the United States...

. His parents were Ephraim Lyon Blaine and his wife Maria Gillespie. The Blaines were Scots-Irish American

Scots-Irish American

Scotch-Irish Americans are an estimated 250,000 Presbyterian and other Protestant dissenters from the Irish province of Ulster who immigrated to North America primarily during the colonial era and their descendants. Some scholars also include the 150,000 Ulster Protestants who immigrated to...

s. The Gillespie women, however, were ardent Irish Catholics, with a close relationship to Notre Dame University. According to Blaine's entry in the "Representative Men of Maine" (1893), "Ephraim L. was an intellectual

Intellectual

An intellectual is a person who uses intelligence and critical or analytical reasoning in either a professional or a personal capacity.- Terminology and endeavours :"Intellectual" can denote four types of persons:...

, an educated, and, in many respects, a brilliant man, but he was not regarded as a practical man. He was a graduate of Washington College

Washington & Jefferson College

Washington & Jefferson College, also known as W & J College or W&J, is a private liberal arts college in Washington, Pennsylvania, in the United States, which is south of Pittsburgh...

. He was a member of the Washington Literary Society at Washington College

Washington & Jefferson College

Washington & Jefferson College, also known as W & J College or W&J, is a private liberal arts college in Washington, Pennsylvania, in the United States, which is south of Pittsburgh...

. In 1820 he married Maria Gillespie, a granddaughter of Neal Gillespie, who came to America from the north of Ireland

Ireland

Ireland is an island to the northwest of continental Europe. It is the third-largest island in Europe and the twentieth-largest island on Earth...

in 1771. The husband was a Presbyterian and the wife a Roman Catholic. His paternal grandfather was named James Blaine, a local justice of the peace in Brownsville. His paternal great-grandfather Col. Ephraim Blaine (1741–1804), served in the Continental Army

Continental Army

The Continental Army was formed after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War by the colonies that became the United States of America. Established by a resolution of the Continental Congress on June 14, 1775, it was created to coordinate the military efforts of the Thirteen Colonies in...

during the American Revolution

American Revolution

The American Revolution was the political upheaval during the last half of the 18th century in which thirteen colonies in North America joined together to break free from the British Empire, combining to become the United States of America...

, from 1778 to 1782 as commissary-general of the Northern Department.

Early career

With many early evidences of literary capacity and political aptitude, Blaine graduated at Washington College (now Washington and Jefferson College) in nearby Washington, PennsylvaniaWashington, Pennsylvania

Washington is a city in and the county seat of Washington County, Pennsylvania, United States, within the Pittsburgh Metro Area in the southwestern part of the state...

, in 1847, where he was a member of the Delta Kappa Epsilon

Delta Kappa Epsilon

Delta Kappa Epsilon is a fraternity founded at Yale College in 1844 by 15 men of the sophomore class who had not been invited to join the two existing societies...

fraternity

Fraternities and sororities

Fraternities and sororities are fraternal social organizations for undergraduate students. In Latin, the term refers mainly to such organizations at colleges and universities in the United States, although it is also applied to analogous European groups also known as corporations...

(Theta chapter). Subsequently, Blaine taught at the Western Military Institute

Western Military Institute

The Western Military Institute was a preparatory school and college located first in Kentucky, then in Tennessee. It was founded by Thornton Fitzhugh Johnson in 1847, and initially located in Georgetown, Kentucky....

in Blue Lick Springs, Kentucky, and from 1852 to 1854, he taught at the Pennsylvania Institution for the Blind in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Philadelphia is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and the county seat of Philadelphia County, with which it is coterminous. The city is located in the Northeastern United States along the Delaware and Schuylkill rivers. It is the fifth-most-populous city in the United States,...

. During this period, also, he studied law. Blaine married Harriet Stanwood on June 30, 1850. The couple had numerous children, including sons James G. Blaine, Jr. and Walker Blaine

Walker Blaine

-Biography:Walker Blaine was born in Augusta, Maine on May 8, 1855, the son of James G. Blaine and Harriet Blaine. In 1876, he graduated from Yale College, where he was a member of Skull and Bones....

.

His oldest son Emmons Blaine married Anita McCormick, daughter of Cyrus McCormick

Cyrus McCormick

Cyrus Hall McCormick, Sr. was an American inventor and founder of the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company, which became part of International Harvester Company in 1902.He and many members of the McCormick family became prominent Chicagoans....

on September 26, 1889, but died less than three years later on June 18, 1892.

After settling in Augusta, Maine

Augusta, Maine

Augusta is the capital of the US state of Maine, county seat of Kennebec County, and center of population for Maine. The city's population was 19,136 at the 2010 census, making it the third-smallest state capital after Montpelier, Vermont and Pierre, South Dakota...

, in 1854, he became editor of the Kennebec Journal

Kennebec Journal

The Kennebec Journal is a seven-day morning daily newspaper published in Augusta, Maine. From 1998 to 2009, it was owned by Blethen Maine Newspapers, a subsidiary of The Seattle Times Company. It was then sold to MaineToday Media. The newspaper covers the capital area and southern Kennebec...

, and subsequently on the Portland Advertiser.

He soon abandoned editorial work for a more active public career. He served as a member in the Maine House of Representatives

Maine House of Representatives

The Maine House of Representatives is the lower house of the Maine Legislature. The House consists of 151 members representing an equal amount of districts across the state. Each voting member of the House represents around 8,450 citizens of the state...

from 1859 to 1862, serving the last two years as speaker

Speaker (politics)

The term speaker is a title often given to the presiding officer of a deliberative assembly, especially a legislative body. The speaker's official role is to moderate debate, make rulings on procedure, announce the results of votes, and the like. The speaker decides who may speak and has the...

. He also became chairman of the Republican state committee

Maine Republican Party

The Maine Republican Party is the affiliate of the United States Republican Party in Maine. It was founded in Strong, Maine on August 7, 1854. The state Chairman is Charles M. Webster....

in 1859, and for more than 20 years personally directed every campaign of his party. Among Blaine's admirers, he was known as the "Plumed Knight."

Congressional career

38th United States Congress

-House of Representatives:Before this Congress, the 1860 United States Census and resulting reapportionment changed the size of the House to 241 members...

and to the six succeeding U.S. Congresses and served from March 4, 1863, to July 10, 1876, when he resigned. He was Speaker of the House

Speaker of the United States House of Representatives

The Speaker of the United States House of Representatives, or Speaker of the House, is the presiding officer of the United States House of Representatives...

for three terms—during the 41st

41st United States Congress

-House of Representatives:- Senate :* President : Schuyler Colfax* President pro tempore: Henry B. Anthony - House of Representatives :* Speaker: James G. Blaine -Members:This list is arranged by chamber, then by state...

through 43rd United States Congress

43rd United States Congress

The Forty-third United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1873 to March 4, 1875, during the fifth and sixth...

es. He served as chairman of the Rules Committee

United States House Committee on Rules

The Committee on Rules, or Rules Committee, is a committee of the United States House of Representatives. Rather than being responsible for a specific area of policy, as most other committees are, it is in charge of determining under what rule other bills will come to the floor...

during the 43rd through 45th United States Congress

45th United States Congress

-House of Representatives:-Leadership:-Senate:*President: William A. Wheeler *President pro tempore: Thomas W. Ferry -House of Representatives:*Speaker: Samuel J. Randall -Members:This list is arranged by chamber, then by state...

es, followed by over four years in the Senate

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

.

Reconstruction

The Reconstruction of the South was the main issue and Blaine took a moderate position, usually opposing the Radical Republicans. Blaine contended that representation in the South should be based on total population instead of voters—so that blacks were counted even when they could not vote. This view prevailed, and the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States ConstitutionFourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was adopted on July 9, 1868, as one of the Reconstruction Amendments.Its Citizenship Clause provides a broad definition of citizenship that overruled the Dred Scott v...

was substantially Blaine's proposition.

Greenback (money)

The term greenback refers to paper currency that was issued by the United States during the American Civil War.There are at least two types of notes that were called greenback:*United States Note*Demand Note...

s. He took up the cause of naturalized American citizens who, on return to their native land, were subject to prosecution on charges of disloyalty. His work led to the treaty of 1870 between the United States and Britain, which placed adopted and native citizens on the same footing.

Blaine Amendment

In 1875, to promote the separation of church and stateSeparation of church and state

The concept of the separation of church and state refers to the distance in the relationship between organized religion and the nation state....

, Blaine proposed the Blaine Amendment

Blaine Amendment

The term Blaine Amendment refers to either a failed federal constitutional amendment or actual constitutional provisions that exist in 38 of the 50 state constitutions in the United States both of which forbid direct government aid to educational institutions that have any religious affiliation...

, a constitutional amendment that would prohibit the use of public funds by any religious school. It never passed Congress but a majority of states subsequently adopted similar laws.

Anti-Catholicism in the United States

Strong political and theological positions hostile to the Catholic Church and its followers was prominent among Protestants in Britain and Germany from the Protestant Reformation onwards. Immigrants brought them to the American colonies. Two types of anti-Catholic rhetoric existed in colonial society...

. It was strongly supported by Protestants, especially Methodists

Methodism

Methodism is a movement of Protestant Christianity represented by a number of denominations and organizations, claiming a total of approximately seventy million adherents worldwide. The movement traces its roots to John Wesley's evangelistic revival movement within Anglicanism. His younger brother...

, Baptists and Congregationalists

Congregational church

Congregational churches are Protestant Christian churches practicing Congregationalist church governance, in which each congregation independently and autonomously runs its own affairs....

. Blaine, who actively sought Catholic votes when he ran for president in 1884, believed that his amendment would forestall the danger of bitter and divisive agitation on the question.

Scandals

Blaine was an unsuccessful candidate for nomination for president on the Republican ticket in 1876. (See United States presidential election, 1876United States presidential election, 1876

The United States presidential election of 1876 was one of the most disputed and controversial presidential elections in American history. Samuel J. Tilden of New York outpolled Ohio's Rutherford B. Hayes in the popular vote, and had 184 electoral votes to Hayes's 165, with 20 votes uncounted...

, United States presidential election, 1880

United States presidential election, 1880

The United States presidential election of 1880 was largely seen as a referendum on the end of Reconstruction in Southern states carried out by the Republicans. There were no pressing issues of the day save tariffs, with the Republicans supporting higher tariffs and the Democrats supporting lower...

.) His chance for securing the 1876 nomination, however, was damaged by persistent charges that as a member of Congress he had been guilty of corruption in his relations with the Little Rock & Fort Smith Railway and the Northern Pacific Railway

Northern Pacific Railway

The Northern Pacific Railway was a railway that operated in the west along the Canadian border of the United States. Construction began in 1870 and the main line opened all the way from the Great Lakes to the Pacific when former president Ulysses S. Grant drove in the final "golden spike" in...

. By the majority of Republicans, he was considered to have cleared himself completely, and he missed the nomination for President by only 28 votes at the Republican National Convention

Republican National Convention

The Republican National Convention is the presidential nominating convention of the Republican Party of the United States. Convened by the Republican National Committee, the stated purpose of the convocation is to nominate an official candidate in an upcoming U.S...

, being finally beaten by a combination of supporters of all the other candidates going to dark horse nominee

Dark horse

Dark horse is a term used to describe a little-known person or thing that emerges to prominence, especially in a competition of some sort.-Origin:The term began as horse racing parlance...

Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes was the 19th President of the United States . As president, he oversaw the end of Reconstruction and the United States' entry into the Second Industrial Revolution...

. He was mocked by political opponents as "Blaine, Blaine, James G. Blaine, the continental liar from the State of Maine!"

Plumed Knight

Blaine was a leading candidate going into the 1876 Republican National Convention; he was nominated by Robert G. IngersollRobert G. Ingersoll

Robert Green "Bob" Ingersoll was a Civil War veteran, American political leader, and orator during the Golden Age of Freethought, noted for his broad range of culture and his defense of agnosticism. He was nicknamed "The Great Agnostic."-Life and career:Robert Ingersoll was born in Dresden, New York...

in a brilliant speech that made Ingersoll famous, extolling him as the "Plumed Knight:"

- The people demand a man whose political reputation is spotless as a star; but they do not demand that their candidate shall have a certificate of moral character signed by a Confederate congress. . . . This is a grand year--a year filled with recollections of the Revolution. . . a year in which the people call for the man who has torn from the throat of treason the tongue of slander--for the man who has snatched the mask of Democracy from the hideous face of rebellion; for the man who, like an intellectual athlete, has stood in the arena of debate and challenged all comers, and who is still a total stranger to defeat.... James G. Blaine marched down the halls of the American Congress and threw his shining lance full and fair against the brazen foreheads of the defamers of his country and the maligners of his honor.

The rivalries between Blaine's "Half Breeds" and Stalwarts (Grant supporters) was so strong that a compromise candidate, Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes was the 19th President of the United States . As president, he oversaw the end of Reconstruction and the United States' entry into the Second Industrial Revolution...

of Ohio, was chosen in 1876 and then elected in a highly controversial election that ended in the Compromise of 1877

Compromise of 1877

The Compromise of 1877, also known as the Corrupt Bargain, refers to a purported informal, unwritten deal that settled the disputed 1876 U.S. Presidential election and ended Congressional Reconstruction. Through it, Republican Rutherford B. Hayes was awarded the White House over Democrat Samuel J...

and the end of Reconstruction.

Senator

Blaine was appointed and subsequently elected as a Republican to the Senate. He served for four years, and his political activity was unabated — currency laws were especially prominent in his legislative portfolio. Blaine, who had previously opposed greenbackGreenback (money)

The term greenback refers to paper currency that was issued by the United States during the American Civil War.There are at least two types of notes that were called greenback:*United States Note*Demand Note...

inflation, now resisted depreciated silver

Bimetallism

In economics, bimetallism is a monetary standard in which the value of the monetary unit is defined as equivalent both to a certain quantity of gold and to a certain quantity of silver; such a system establishes a fixed rate of exchange between the two metals...

coinage. He championed the advancement of American shipping, and advocated generous subsidies

Subsidy

A subsidy is an assistance paid to a business or economic sector. Most subsidies are made by the government to producers or distributors in an industry to prevent the decline of that industry or an increase in the prices of its products or simply to encourage it to hire more labor A subsidy (also...

, insisting that the policy of protection should be applied on sea as well as on land.

Blaine was re-elected and served from July 10, 1876, to March 5, 1881, when he resigned to become Secretary of State

United States Secretary of State

The United States Secretary of State is the head of the United States Department of State, concerned with foreign affairs. The Secretary is a member of the Cabinet and the highest-ranking cabinet secretary both in line of succession and order of precedence...

. While in the Senate, he held the minor chairmanships of the U.S. Senate Committee on Civil Service and Retrenchment (45th Congress) and U.S. Senate Committee on Rules (also 45th Congress). During this period he tried again for a Presidential nomination: the Republican National Convention of 1880, divided between the two nearly equal forces of Blaine and former President Ulysses Grant — John Sherman

John Sherman (politician)

John Sherman, nicknamed "The Ohio Icicle" , was a U.S. Representative and U.S. Senator from Ohio during the Civil War and into the late nineteenth century. He served as both Secretary of the Treasury and Secretary of State and was the principal author of the Sherman Antitrust Act...

of Ohio

Ohio

Ohio is a Midwestern state in the United States. The 34th largest state by area in the U.S.,it is the 7th‑most populous with over 11.5 million residents, containing several major American cities and seven metropolitan areas with populations of 500,000 or more.The state's capital is Columbus...

also having a considerable following — struggled through 36 ballots, when the friends of Blaine, combining with those of Sherman, succeeded in nominating James A. Garfield.

Secretary of State and 1884 run for the presidency

Blaine was Secretary of State in the cabinets of James A. Garfield and Chester A. ArthurChester A. Arthur

Chester Alan Arthur was the 21st President of the United States . Becoming President after the assassination of President James A. Garfield, Arthur struggled to overcome suspicions of his beginnings as a politician from the New York City Republican machine, succeeding at that task by embracing...

; later, when he took the same job in President Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison was the 23rd President of the United States . Harrison, a grandson of President William Henry Harrison, was born in North Bend, Ohio, and moved to Indianapolis, Indiana at age 21, eventually becoming a prominent politician there...

's Cabinet, he became the second and last person to hold this position in two non-consecutive terms. After Garfield's death on September 19, 1881, Arthur asked all of the cabinet members to postpone their resignations until Congress recessed that December. Blaine initially agreed but changed his mind in mid-October and left office December 19. During his two months under Arthur, Blaine dedicated his time to forging his own achievements in an attempt to improve his chances in the 1884 presidential election. In June 1884, he was nominated to run for president by his party on the fourth ballot at the 1884 Republican National Convention

1884 Republican National Convention

The 1884 Republican National Convention was a presidential nominating convention held at the Exposition Hall in Chicago, Illinois, on June 3–6, 1884. It resulted in the nomination of James G. Blaine and John A. Logan for President and Vice President of the United States. The ticket lost in the...

.

He was the unsuccessful Republican nominee for President in 1884; he was the only nonincumbent Republican nominee to lose a presidential race between 1860 and 1912, and only the second Republican Presidential nominee to lose at all. Republican reformers, called "Mugwumps", supported Cleveland because of Blaine's reputation for corruption. After heated canvassing, he lost by a narrow margin in New York

New York

New York is a state in the Northeastern region of the United States. It is the nation's third most populous state. New York is bordered by New Jersey and Pennsylvania to the south, and by Connecticut, Massachusetts and Vermont to the east...

. Many, including Blaine himself, attributed his defeat to the effect of a phrase, "Rum, Romanism and Rebellion

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

", used by a Protestant clergyman, the Rev. Samuel D. Burchard, on October 29, 1884, in Blaine's presence, to characterize what, in his opinion, the Democrats

History of the United States Democratic Party

The history of the Democratic Party of the United States is an account of the oldest political party in the United States and arguably the oldest democratic party in the world....

stood for. "Rum" meant the liquor interest; "Romanism" meant Catholics; "Rebellion" meant Confederates

Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America was a government set up from 1861 to 1865 by 11 Southern slave states of the United States of America that had declared their secession from the U.S...

in 1861.

The phrase was not Blaine's, but his opponents made use of it to characterize his hostility toward Catholics, some of whom probably did switch their vote. Blaine's mother was a Roman Catholic of Irish

Irish people

The Irish people are an ethnic group who originate in Ireland, an island in northwestern Europe. Ireland has been populated for around 9,000 years , with the Irish people's earliest ancestors recorded having legends of being descended from groups such as the Nemedians, Fomorians, Fir Bolg, Tuatha...

descent and his sister was a nun

Nun

A nun is a woman who has taken vows committing her to live a spiritual life. She may be an ascetic who voluntarily chooses to leave mainstream society and live her life in prayer and contemplation in a monastery or convent...

, and speculation was that he might gain votes from a heavily Democratic group. However, Catholics were already suspicious of Blaine over his support of the Blaine Amendments.

Election of 1888

Still the party leader, Blaine resumed his writing and speaking, and visited Europe. He helped Benjamin HarrisonBenjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison was the 23rd President of the United States . Harrison, a grandson of President William Henry Harrison, was born in North Bend, Ohio, and moved to Indianapolis, Indiana at age 21, eventually becoming a prominent politician there...

become the GOP nominee in 1888; in 1889 President Harrison appointed Blaine his Secretary of State.

Secretary of State

Blaine's second term as Secretary were probably the most constructive part of his career, with major attention focused on Latin-American and Britain. He pushed for a canal across Panama, built, operated, and controlled by the United States; he secured Congressional legislation resulting in the Pan-American Conference which met in Washington in October, 1889. Blaine's set up the Bureau of American Republics in Washington. As an early environmentalist he used diplomacy to protect the seal herds in the Pribilof Islands of Alaska. He tried to annex Hawaii (which almost succeeded in early 1893, but was postponed to 1898). Indeed, the permanent influence of Blaine on American life was through his foreign policy. Although Blaine concluded tariff reciprocity agreements with eight Latin American nations, reciprocity negotiations with Canada stalled in 1891-92. Harrison and Blaine feared a political backlash from American farmers and lumbermen if concessions were made to Canada. Blaine's Anglophobia also influenced the outcome of the negotiations, and Canada's negotiators to the end resisted the inclusion of reciprocity on manufactured articles in any treaty. The two most important reciprocity agreements were signed with Brazil and with Spain for Cuba and Puerto Rico.

Samoa

Samoa , officially the Independent State of Samoa, formerly known as Western Samoa is a country encompassing the western part of the Samoan Islands in the South Pacific Ocean. It became independent from New Zealand in 1962. The two main islands of Samoa are Upolu and one of the biggest islands in...

, pursued a vigorous diplomacy with Italy over the lynching of 11 Italians accused of being Mafiosi who murdered the police chief in New Orleans in 1891, held a firm attitude during the strained relations between the United States and Chile

Chile

Chile ,officially the Republic of Chile , is a country in South America occupying a long, narrow coastal strip between the Andes mountains to the east and the Pacific Ocean to the west. It borders Peru to the north, Bolivia to the northeast, Argentina to the east, and the Drake Passage in the far...

over a deadly barroom brawl involving sailors from the USS Baltimore

USS Baltimore (C-3)

The fourth USS Baltimore was a United States Navy cruiser, the second protected cruiser to be built by an American yard. Like the previous one, , the design was commissioned from the British company of W...

; and carried on with Britain a controversy over the seal fisheries of Bering Sea

Bering Sea

The Bering Sea is a marginal sea of the Pacific Ocean. It comprises a deep water basin, which then rises through a narrow slope into the shallower water above the continental shelves....

—a difference afterward settled by arbitration

Arbitration

Arbitration, a form of alternative dispute resolution , is a legal technique for the resolution of disputes outside the courts, where the parties to a dispute refer it to one or more persons , by whose decision they agree to be bound...

. Blaine sought to secure a modification of the Clayton–Bulwer Treaty, and in an extended correspondence with the British government strongly asserted the policy of an exclusive American control of any isthmian canal which might be built to connect the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

In foreign policy Blaine was a transitional figure, marking the end of one era in foreign policy and foreshadowing the next. He brought energy, imagination and verve to the office in sharp contrast with his somnolent rivals, inspiring his activist twentieth-century successors. He was a pioneer in arbitration treaties, tariff reciprocity, and American administration of Latin American customs houses to avert civil wars over the revenue stream. Blaine wanted the U.S. to be the protector and leader of the Western Hemisphere, even if the Latin America countries disagreed. He insisted on keeping the Americas away from European control while favoring peaceful arbitration and negotiations rather than war. Blaine forcefully argued for the national interests of his country. He kept the big picture firmly in mind, seeking long-term programs and not simply short-term fixes for the matter at hand.

Death

Though not a candidate in 1892, Blaine received nearly 200 votes on the first ballot. In his later years, he wrote Twenty Years of Congress (1884–1886). which historians have mined for its rich details.Blaine played a role in founding Bates College

Bates College

Bates College is a highly selective, private liberal arts college located in Lewiston, Maine, in the United States. and was most recently ranked 21st in the nation in the 2011 US News Best Liberal Arts Colleges rankings. The college was founded in 1855 by abolitionists...

in Lewiston, Maine

Lewiston, Maine

Lewiston is a city in Androscoggin County in Maine, and the second-largest city in the state. The population was 41,592 at the 2010 census. It is one of two principal cities of and included within the Lewiston-Auburn, Maine metropolitan New England city and town area and the Lewiston-Auburn, Maine...

, and he served as a longtime trustee (1863–1893) of the college; he was given an honorary degree from Bates in 1869.

In late 1892 Blaine's health failed rapidly and he died four days shy of his 63rd birthday in Washington, D.C. at the age of 62 of a heart attack. He was interred in Oak Hill Cemetery. Reinterment took place in the Blaine Memorial Park, Augusta, Maine

Augusta, Maine

Augusta is the capital of the US state of Maine, county seat of Kennebec County, and center of population for Maine. The city's population was 19,136 at the 2010 census, making it the third-smallest state capital after Montpelier, Vermont and Pierre, South Dakota...

, in June 1920.

Monuments and memorials

- Counties named in his honor include Blaine County, IdahoBlaine County, IdahoBlaine County is a county located in the U.S. state of Idaho. As of the 2010 Census the county had a population of 21,376. The county seat and largest city is Hailey. The county is home to the Sun Valley ski resort....

; Blaine County, MontanaBlaine County, Montana-National protected areas:* Black Coulee National Wildlife Refuge* Nez Perce National Historical Park * Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument -Economy:The main industry in Blaine County is Agriculture...

; Blaine County, OklahomaBlaine County, OklahomaBlaine County is a county located in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. As of 2000, the population is 11,976. Its county seat is Watonga. Blaine County is the birthplace of voice actor Clarence Nash, the voice of Donald Duck....

; and Blaine County, NebraskaBlaine County, Nebraska-History:Blaine County was formed in 1885. It was named after presidential candidate James G. Blaine.-Demographics:As of the census of 2000, there were 583 people, 238 households, and 168 families residing in the county. The population density was 1 people per square mile . There were 333 housing...

. - The cities of Blaine, WashingtonBlaine, WashingtonBlaine is a city in Whatcom County, Washington, United States. The city's northern boundary is the Canadian border. Blaine is the shared home of the Peace Arch international monument...

, and Blaine, MinnesotaBlaine, MinnesotaAs of the census of 2000, there were 44,942 people, 15,898 households, and 12,177 families residing in the city. The population density is 1,330 people per square mile . There are 16,169 housing units at an average density of 477.6 per square mile...

, and the towns of Blaine, MaineBlaine, MaineBlaine is a town in Aroostook County, Maine, United States. The population was 806 as of the 2000 census. It was known as Alva prior to incorporation in 1874, when it was renamed in honor of James G. Blaine, then Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives...

, Blainesburg, and Blain, PennsylvaniaBlain, PennsylvaniaBlain is a borough in Perry County, Pennsylvania, United States. The population was 252 at the 2000 census. It is part of the Harrisburg–Carlisle Metropolitan Statistical Area.- History :...

are named after him. - There is a James G. Blaine school in ChicagoChicagoChicago is the largest city in the US state of Illinois. With nearly 2.7 million residents, it is the most populous city in the Midwestern United States and the third most populous in the US, after New York City and Los Angeles...

and in Philadelphia. - His home in Augusta, MaineAugusta, MaineAugusta is the capital of the US state of Maine, county seat of Kennebec County, and center of population for Maine. The city's population was 19,136 at the 2010 census, making it the third-smallest state capital after Montpelier, Vermont and Pierre, South Dakota...

, the Blaine House, is now the official residence of the Governor of MaineGovernor of MaineThe governor of Maine is the chief executive of the State of Maine. Before Maine was admitted to the Union in 1820, Maine was part of Massachusetts and the governor of Massachusetts was chief executive....

. - His home in Washington, D.C.Washington, D.C.Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

, Blaine Mansion, is a contributing propertyContributing propertyIn the law regulating historic districts in the United States, a contributing resource or contributing property is any building, structure, or object which adds to the historical integrity or architectural qualities that make the historic district, listed locally or federally, significant...

to the Dupont Circle Historic District and Massachusetts Avenue Historic DistrictMassachusetts Avenue (Washington, D.C.)Massachusetts Avenue is a major diagonal transverse road in Washington, D.C., and the Massachusetts Avenue Historic District is a historic district that includes part of it....

. - The railroad depot in what became the town of Cornelia, GeorgiaCornelia, GeorgiaCornelia is a city in Habersham County, Georgia, United States. The population was 3,834 at the 2010 census. It is home to one of the world's largest apple sculptures, which is displayed on top of an obelisk shaped monument...

(October 22, 1887) was named Blaine in his honor.

In fiction

- Blaine is featured as the President of the United StatesPresident of the United StatesThe President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

in Harry TurtledoveHarry TurtledoveHarry Norman Turtledove is an American novelist, who has produced works in several genres including alternate history, historical fiction, fantasy and science fiction.- Life :...

's Southern Victory Series novel How Few RemainHow Few RemainHow Few Remain is a 1997 alternate history novel by Harry Turtledove. It is the first part of the Southern Victory Series saga, which depicts a world in which the Confederacy won the American Civil War. The book received the Sidewise Award for Alternate History in 1997, and was also nominated for...

, in which he leads the United States to defeat against the Confederate States of AmericaConfederate States of AmericaThe Confederate States of America was a government set up from 1861 to 1865 by 11 Southern slave states of the United States of America that had declared their secession from the U.S...

in the Second Mexican War.

- He also is a character in Gore VidalGore VidalGore Vidal is an American author, playwright, essayist, screenwriter, and political activist. His third novel, The City and the Pillar , outraged mainstream critics as one of the first major American novels to feature unambiguous homosexuality...

's 18761876 (novel)Gore Vidal's 1876 is the third historical novel in his Narratives of Empire series. It was published in 1976 and details the events of a year described by Vidal himself as "probably the low point in our republic's history."...

, about the election of 1876United States presidential election, 1876The United States presidential election of 1876 was one of the most disputed and controversial presidential elections in American history. Samuel J. Tilden of New York outpolled Ohio's Rutherford B. Hayes in the popular vote, and had 184 electoral votes to Hayes's 165, with 20 votes uncounted...

.

Further reading

Short survey. online edition and 8. pp. 109–184. online edition online edition the standard biography Popular online edition Old fashioned but generally accurate. online editionExternal links

}}

}}