Carpetbagger

Encyclopedia

Pejorative

Pejoratives , including name slurs, are words or grammatical forms that connote negativity and express contempt or distaste. A term can be regarded as pejorative in some social groups but not in others, e.g., hacker is a term used for computer criminals as well as quick and clever computer experts...

term Southerners gave to Northerners (also referred to as Yankee

Yankee

The term Yankee has several interrelated and often pejorative meanings, usually referring to people originating in the northeastern United States, or still more narrowly New England, where application of the term is largely restricted to descendants of the English settlers of the region.The...

s) who moved to the South during the Reconstruction era, between 1865 and 1877.

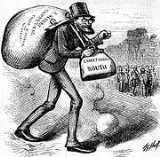

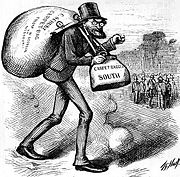

The term referred to the observation that these newcomers tended to carry "carpet bag

Carpet bag

A carpet bag is a traveling bag made of carpet, commonly from an oriental rug, ranging in size from a small purse to a large duffel bag.Such bags were popular in the United States and Europe during the 19th century...

s," a common form of luggage at the time (sturdy and made from repurposed carpet). It was used as a derogatory term, suggesting opportunism and exploitation by the outsiders. Together with Republicans they are said to have politically manipulated and controlled former Confederate states for varying periods for their own financial and power gains. In sum, carpetbaggers were seen as insidious Northern outsiders with questionable objectives meddling in local politics, buying up plantations at fire-sale prices and taking advantage of Southerners. Carpetbagger is not to be confused with copperhead

Copperheads (politics)

The Copperheads were a vocal group of Democrats in the Northern United States who opposed the American Civil War, wanting an immediate peace settlement with the Confederates. Republicans started calling anti-war Democrats "Copperheads," likening them to the venomous snake...

, which is a term given to a person from the North who sympathized with the Southern claim of right to Secession.

The term carpetbaggers was also used to describe the Republican political appointees who came South, arriving with their travel carpet bags. Southerners considered them ready to loot and plunder the defeated South.

In modern usage in the U.S., the term is sometimes used derisively to refer to a politician who runs for public office in an area where he or she does not have deep community ties, or has lived only for a short time. In the United Kingdom, the term was adopted to refer informally to those who join a mutual organization

Mutual organization

A mutual, mutual organization, or mutual society is an organization based on the principle of mutuality. Unlike a true cooperative, members usually do not contribute to the capital of the company by direct investment, but derive their right to profits and votes through their customer relationship...

, such as a building society

Building society

A building society is a financial institution owned by its members as a mutual organization. Building societies offer banking and related financial services, especially mortgage lending. These institutions are found in the United Kingdom and several other countries.The term "building society"...

, in order to force it to demutualize

Demutualization

Demutualization is the process by which a customer-owned mutual organization or co-operative changes legal form to a joint stock company. It is sometimes called stocking or privatization. As part of the demutualization process, members of a mutual usually receive a "windfall" payout, in the form...

, that is, to convert into a joint stock company

Joint stock company

A joint-stock company is a type of corporation or partnership involving two or more individuals that own shares of stock in the company...

, solely for personal financial gain.

Reforming impulse

Beginning in 1862 thousands of Northern abolitionistsAbolitionism

Abolitionism is a movement to end slavery.In western Europe and the Americas abolitionism was a movement to end the slave trade and set slaves free. At the behest of Dominican priest Bartolomé de las Casas who was shocked at the treatment of natives in the New World, Spain enacted the first...

and other reformers moved to areas in the South where secession by the Confederates states had failed. Many schoolteachers and religious missionaries arrived in the South, some sponsored by northern churches. Some were abolitionists who sought to continue the struggle for racial equality

Racial equality

Racial equality means different things in different contexts. It mostly deals with an equal regard to all races.It can refer to a belief in biological equality of all human races....

; they often became agents of the federal Freedmen's Bureau, which started operations in 1865 to assist the vast numbers of recently emancipated freedmen. The bureau established public schools in rural areas of the South where public schools had not previously existed. Other Northerners who moved to the South participated in establishing railroads where infrastructure was lacking.

During the time African-American families had been enslaved, they were prohibited from education and learning literacy. Southern states had no public school systems, and the planter elite sent their children to private schools. After the war, thousands of Northern white women moved South; many to teach newly freed African-American children.

While many Northerners went South with reformist impulses, not all Northerners who went South were reformers.

Economic motives

Many carpetbaggers were businessmen who purchased or leased plantations and became wealthy landowners, hiring freedmen to do the labor. Most were former UnionUnion Army

The Union Army was the land force that fought for the Union during the American Civil War. It was also known as the Federal Army, the U.S. Army, the Northern Army and the National Army...

soldiers eager to invest their savings in this promising new frontier, and civilians lured south by press reports of "the fabulous sums of money to be made in the South in raising cotton." Foner notes that "joined with the quest for profit, however, was a reforming spirit, a vision of themselves as agents of sectional reconciliation and the South's "economic regeneration." Accustomed to viewing Southerners—black and white—as devoid of economic initiative and self-discipline, they believed that only "Northern capital and energy" could bring "the blessings of a free labor system to the region."

Carpetbaggers tended to be well educated and middle class in origin. Some had been lawyers, businessmen, newspaper editors, Union Army members and other pillars of Northern communities. The majority (including 52 of the 60 who served in Congress during Reconstruction) were veterans of the Union Army.

Leading "black carpetbaggers" believed the interests of capital and labor identical, and the freedmen entitled to little more than an "honest chance in the race of life."

Many Northern and Southern Republicans shared a modernizing vision of upgrading the Southern economy and society, one that would replace the inefficient Southern plantation regime with railroads, factories and more efficient farming. They actively promoted public schooling and created numerous colleges and universities. The Northerners were especially successful in taking control of Southern railroads, abetted by state legislatures. In 1870 Northerners controlled 21% of the South's railroads (by mileage); 19% of the directors were from the North. By 1890 they controlled 88% of the mileage; 47% of the directors were from the North.

Mississippi

Union Gen. Adelbert AmesAdelbert Ames

Adelbert Ames was an American sailor, soldier, and politician. He served with distinction as a Union Army general during the American Civil War. As a Radical Republican and a Carpetbagger, he was military governor, Senator and civilian governor in Reconstruction-era Mississippi...

, a native of Massachusetts

Massachusetts

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States of America. It is bordered by Rhode Island and Connecticut to the south, New York to the west, and Vermont and New Hampshire to the north; at its east lies the Atlantic Ocean. As of the 2010...

, was appointed military governor and later was elected as Republican governor of Mississippi

Mississippi

Mississippi is a U.S. state located in the Southern United States. Jackson is the state capital and largest city. The name of the state derives from the Mississippi River, which flows along its western boundary, whose name comes from the Ojibwe word misi-ziibi...

during the Reconstruction era. Ames tried unsuccessfully to ensure equal rights for black Mississippians. His political battles with the Southerners and African Americans ripped apart his party.

The "Black and Tan" (biracial) constitutional convention in Mississippi in 1868 included 29 southerners, 17 freedmen and 24 nonsoutherners, nearly all of whom were veterans of the Union Army. They included four men who had lived in the South before the war, two of whom had served in the Confederate States Army

Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army was the army of the Confederate States of America while the Confederacy existed during the American Civil War. On February 8, 1861, delegates from the seven Deep South states which had already declared their secession from the United States of America adopted the...

. Among the more prominent were Gen. Beroth B. Eggleston, a native of New York; Col. A. T. Morgan, of the Second Wisconsin

Wisconsin

Wisconsin is a U.S. state located in the north-central United States and is part of the Midwest. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake Michigan to the east, Michigan to the northeast, and Lake Superior to the north. Wisconsin's capital is...

Volunteers; Gen. W. S. Barry, former commander of a Colored regiment raised in Kentucky

Kentucky

The Commonwealth of Kentucky is a state located in the East Central United States of America. As classified by the United States Census Bureau, Kentucky is a Southern state, more specifically in the East South Central region. Kentucky is one of four U.S. states constituted as a commonwealth...

; an Illinois

Illinois

Illinois is the fifth-most populous state of the United States of America, and is often noted for being a microcosm of the entire country. With Chicago in the northeast, small industrial cities and great agricultural productivity in central and northern Illinois, and natural resources like coal,...

general and lawyer who graduated from Knox College; Maj. W. H. Gibbs, of the Fifteenth Illinois infantry; Judge W. B. Cunningham, of Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania

The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania is a U.S. state that is located in the Northeastern and Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States. The state borders Delaware and Maryland to the south, West Virginia to the southwest, Ohio to the west, New York and Ontario, Canada, to the north, and New Jersey to...

; and Cap. E. J. Castello, of the Seventh Missouri

Missouri

Missouri is a US state located in the Midwestern United States, bordered by Iowa, Illinois, Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Kansas and Nebraska. With a 2010 population of 5,988,927, Missouri is the 18th most populous state in the nation and the fifth most populous in the Midwest. It...

infantry. They were among the founders of the Republican party in Mississippi.

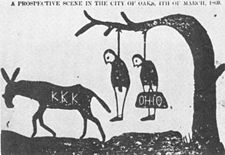

They were prominent in the politics of the state until 1875, but nearly all left Mississippi in 1875 to 1876 under pressure from the Red Shirts and White Liners. These white paramilitary organizations, described as "the military arm of the Democratic Party", worked openly to violently overthrow Republican rule, using intimidation

Intimidation

Intimidation is intentional behavior "which would cause a person of ordinary sensibilities" fear of injury or harm. It's not necessary to prove that the behavior was so violent as to cause terror or that the victim was actually frightened.Criminal threatening is the crime of intentionally or...

and assassination to turn Republicans out of office and suppress freedmen's voting.

Albert T. Morgan, the Republican sheriff

Sheriff

A sheriff is in principle a legal official with responsibility for a county. In practice, the specific combination of legal, political, and ceremonial duties of a sheriff varies greatly from country to country....

of Yazoo, Mississippi, received a brief flurry of national attention when insurgent white Democrats took over the county government and forced him to flee. He later wrote Yazoo; Or, on the Picket Line of Freedom in the South (1884).

On November 6, 1875, Hiram Revels, a Mississippi Republican and the first African-American U.S. Senator

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

, wrote a letter to President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant was the 18th President of the United States as well as military commander during the Civil War and post-war Reconstruction periods. Under Grant's command, the Union Army defeated the Confederate military and ended the Confederate States of America...

that was widely reprinted. Revels denounced Ames and Northerners for manipulating the Black vote for personal benefit, and for keeping alive wartime hatreds:

- Since reconstruction, the masses of my people have been, as it were, enslaved in mind by unprincipled adventurers, who, caring nothing for country, were willing to stoop to anything no matter how infamous, to secure power to themselves, and perpetuate it..... My people have been told by these schemers, when men have been placed on the ticket who were notoriously corrupt and dishonest, that they must vote for them; that the salvation of the party depended upon it; that the man who scratched a ticket was not a Republican. This is only one of the many means these unprincipled demagogues have devised to perpetuate the intellectual bondage of my people.... The bitterness and hate created by the late civil strife has, in my opinion, been obliterated in this state, except perhaps in some localities, and would have long since been entirely obliterated, were it not for some unprincipled men who would keep alive the bitterness of the past, and inculcate a hatred between the races, in order that they may aggrandize themselves by office, and its emoluments, to control my people, the effect of which is to degrade them.

North Carolina

Corruption was a charge made by Democrats in North CarolinaNorth Carolina

North Carolina is a state located in the southeastern United States. The state borders South Carolina and Georgia to the south, Tennessee to the west and Virginia to the north. North Carolina contains 100 counties. Its capital is Raleigh, and its largest city is Charlotte...

against the Republicans, notes the historian Paul Escott, "because its truth was apparent." The historians Eric Foner and W.E.B. Du Bois have noted that Democrats as well as Republicans received bribes and participated in decisions about the railroad. Gen. Milton S. Littlefield, was dubbed the "Prince of Carpetbaggers," and bought votes in the legislature "to support grandiose and fraudulent railroad schemes." Escott concludes that some Democrats were involved, but Republicans "bore the main responsibility for the issue of $28 million in state bonds for railroads and the accompanying corruption. This sum, enormous for the time, aroused great concern." Foner says Littlefield disbursed $200,000 (bribes) to win support in the legislature for state money for his railroads, and Democrats as well as Republicans were guilty of taking the bribes and making the decisions on the railroad. North Carolina Democrats condemned the legislature's "depraved villains, who take bribes every day;" one local Republican officeholder complained, "I deeply regret the course of some of our friends in the Legislature as well as out of it in regard to financial matters, it is very embarrassing indeed."

Extravagance and corruption increased taxes and the costs of government in a state that had always favored low expenditure, Escott pointed out. The context was that a planter elite kept taxes low because it benefited them. They used their money toward private ends rather than public investment. None of the states had established public school systems before the Reconstruction state legislatures created them, and they had systematically underinvested in infrastructure such as roads and railroads. Planters whose properties occupied prime riverfront locations relied on river transportation, but smaller farmers in the backcountry suffered.

Escott claimed, "Some money went to very worthy causes— the 1869 legislature, for example, passed a school law that began the rebuilding and expansion of the state's public schools. But far too much was wrongly or unwisely spent" to aid the Republican Party leadership. A Republican county commissioner in Alamance eloquently denounced the situation: "Men are placed in power who instead of carrying out their duties . . . form a kind of school for to graduate Rascals. Yes if you will give them a few Dollars they will liern you for an accomplished Rascal. This is in reference to the taxes that are rung from the labouring class of people. Without a speedy reformation I will have to resign my post."

Albion W. Tourgée

Albion W. Tourgée

Albion Winegar Tourgée was an American soldier, Radical Republican, lawyer, judge, novelist, and diplomat. A pioneer civil rights activist, he founded the National Citizens' Rights Association and litigated for the plaintiff Homer Plessy in the famous segregation case Plessy v. Ferguson...

, formerly of Ohio and a friend of President James A. Garfield, moved to North Carolina, where he practiced as a lawyer and was appointed a judge. He once opined that "Jesus Christ was a carpetbagger." Tourgée later wrote A Fool's Errand, a largely autobiographical novel about an idealistic carpetbagger persecuted by the Ku Klux Klan

Ku Klux Klan

Ku Klux Klan, often abbreviated KKK and informally known as the Klan, is the name of three distinct past and present far-right organizations in the United States, which have advocated extremist reactionary currents such as white supremacy, white nationalism, and anti-immigration, historically...

in North Carolina.

South Carolina

A politician in South CarolinaSouth Carolina

South Carolina is a state in the Deep South of the United States that borders Georgia to the south, North Carolina to the north, and the Atlantic Ocean to the east. Originally part of the Province of Carolina, the Province of South Carolina was one of the 13 colonies that declared independence...

who was called a carpetbagger was Daniel Henry Chamberlain

Daniel Henry Chamberlain

Daniel Henry Chamberlain was a planter, lawyer, author and the 76th Governor of South Carolina from 1874 until 1877....

, a New England

New England

New England is a region in the northeastern corner of the United States consisting of the six states of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut...

er who had served as an officer of a predominantly black regiment of the United States Colored Troops

United States Colored Troops

The United States Colored Troops were regiments of the United States Army during the American Civil War that were composed of African American soldiers. First recruited in 1863, by the end of the Civil War, the men of the 175 regiments of the USCT constituted approximately one-tenth of the Union...

. He was appointed South Carolina's attorney general from 1868 to 1872 and was elected Republican governor from 1874 to 1877. As a result of the national Compromise of 1877

Compromise of 1877

The Compromise of 1877, also known as the Corrupt Bargain, refers to a purported informal, unwritten deal that settled the disputed 1876 U.S. Presidential election and ended Congressional Reconstruction. Through it, Republican Rutherford B. Hayes was awarded the White House over Democrat Samuel J...

, Chamberlain lost his office. He was narrowly re-elected in a campaign marked by egregious voter fraud and violence against freedmen by Democratic Red Shirts, who succeeded in suppressing the black vote in some majority-black counties. While serving in South Carolina, Chamberlain was a strong supporter of Negro rights.

Some historians of the early 1930s, who belonged to the Dunning School

Dunning School

The Dunning School refers to a group of historians who shared a historiographical school of thought regarding the Reconstruction period of American history .-About:...

that believed that the Reconstruction era was fatally flawed claimed that Chamberlain was later influenced by Social Darwinism

Social Darwinism

Social Darwinism is a term commonly used for theories of society that emerged in England and the United States in the 1870s, seeking to apply the principles of Darwinian evolution to sociology and politics...

to become a white supremacist. They also wrote that he supported states' rights

States' rights

States' rights in U.S. politics refers to political powers reserved for the U.S. state governments rather than the federal government. It is often considered a loaded term because of its use in opposition to federally mandated racial desegregation...

and laissez-faire in the economy. They portrayed "liberty" in 1896 as the right to rise above the rising tide of equality. Chamberlain was said to justify white supremacy by arguing that, in evolutionary terms, the Negro obviously belonged to an inferior social order.

Charles Stearns, also from Massachusetts, wrote an account of his experience in South Carolina: The Black Man of the South, and the Rebels: Or, the Characteristics of the Former and the Recent Outrages of the Latter (1873).

Francis Lewis Cardozo

Francis Lewis Cardozo

Francis Lewis Cardozo was a clergyman, politician, and educator. He was the first African American to hold a statewide office in the United States...

, a black minister from New Haven, Connecticut

New Haven, Connecticut

New Haven is the second-largest city in Connecticut and the sixth-largest in New England. According to the 2010 Census, New Haven's population increased by 5.0% between 2000 and 2010, a rate higher than that of the State of Connecticut, and higher than that of the state's five largest cities, and...

, served as a delegate to South Carolina's Constitutional Convention (1868). He made eloquent speeches advocating that the plantations be broken up and distributed among the freedmen. They wanted their own land to farm and believed they had already paid for land by their years of uncompensated labor and the trials of slavery.

Louisiana

Henry C. WarmothHenry C. Warmoth

Henry Clay Warmoth was the 23rd Governor of Louisiana from 1868 until his impeachment and removal from office in December, 1872.-Early life and military career:...

was the Republican governor of Louisiana from 1868 to 1874. As governor, Warmoth was plagued by accusations of corruption, which continued to be a matter of controversy long after his death. He was accused of using his position as governor to trade in state bonds for his personal benefit. In addition, the newspaper company which he owned received a contract from the state government. Warmoth supported the franchise

Suffrage

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply the franchise, distinct from mere voting rights, is the civil right to vote gained through the democratic process...

for freedmen.

He struggled to lead the state during the years when the White League

White League

The White League was a white paramilitary group started in 1874 that operated to turn Republicans out of office and intimidate freedmen from voting and political organizing. Its first chapter in Grant Parish, Louisiana was made up of many of the Confederate veterans who had participated in the...

, a white Democratic paramilitary

Paramilitary

A paramilitary is a force whose function and organization are similar to those of a professional military, but which is not considered part of a state's formal armed forces....

organization, conducted an open campaign of violence and intimidation against Republicans, including freedmen, with the goals of regaining Democratic power and white supremacy. They ran Republicans out of office, were responsible for the Coushatta Massacre

Coushatta massacre

The Coushatta Massacre was the result of an attack by the White League, a paramilitary organization composed of white Southern Democrats, on Republican officeholders and freedmen in Coushatta, the parish seat of Red River Parish, Louisiana...

, disrupted Republican organizing, and preceded elections with such intimidation and violence that black voting was sharply reduced. Warmoth stayed in Louisiana after Reconstruction and following the white Democrats' regaining political power in the state. He died in 1931 at age 89.

Algernon Sidney Badger

Algernon Sidney Badger was a colonel in the Union Army who became an important Republican carpetbagger government official in New Orleans, Louisiana, during and after Reconstruction.- Early years :...

, a Boston, Massachusetts

Massachusetts

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States of America. It is bordered by Rhode Island and Connecticut to the south, New York to the west, and Vermont and New Hampshire to the north; at its east lies the Atlantic Ocean. As of the 2010...

, native, held various appointed federal positions in New Orleans

New Orleans, Louisiana

New Orleans is a major United States port and the largest city and metropolitan area in the state of Louisiana. The New Orleans metropolitan area has a population of 1,235,650 as of 2009, the 46th largest in the USA. The New Orleans – Metairie – Bogalusa combined statistical area has a population...

only under Republican national administrations during and after Reconstruction. He first came to New Orleans with the Union Army

Union Army

The Union Army was the land force that fought for the Union during the American Civil War. It was also known as the Federal Army, the U.S. Army, the Northern Army and the National Army...

in 1863 and never left the area. He is interred at Metairie Cemetery

Metairie Cemetery

Metairie Cemetery is a cemetery in New Orleans, Louisiana, United States. The name has caused some people to mistakenly presume that the cemetery is located in Metairie, Louisiana, but it is located within the New Orleans city limits, on Metairie Road .-History:This site was previously a horse...

there.

Alabama

George E. SpencerGeorge E. Spencer

George Eliphaz Spencer was a U.S. senator from the state of Alabama.Born in Champion, New York, he was educated at Montreal College in Canada. After relocating to Iowa he engaged in the study of law. During the Civil War, he enlisted as a captain on October 16, 1862. While serving on the staff of...

was a prominent Republican

Alabama Republican Party

The Alabama Republican Party is the state affiliate of the national Republican Party in Alabama. It is the dominant political party in Alabama. The state party is governed by the Alabama Republican Executive Committee. Most of the committee's more than 200 members are elected in district...

U.S. Senator. His 1872 reelection campaign in Alabama

Alabama

Alabama is a state located in the southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Tennessee to the north, Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gulf of Mexico to the south, and Mississippi to the west. Alabama ranks 30th in total land area and ranks second in the size of its inland...

opened him to allegations of "political betrayal of colleagues; manipulation of Federal patronage; embezzlement of public funds; purchase of votes; and intimidation of voters by the presence of Federal troops." He was a major speculator in a distressed financial paper.

Georgia

Tunis CampbellTunis Campbell

Tunis Campbell was a prominent African American politician of the 19th century, and a major figure in Reconstruction Georgia....

, a black New York businessman, was hired in 1863 by Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton

Edwin M. Stanton

Edwin McMasters Stanton was an American lawyer and politician who served as Secretary of War under the Lincoln Administration during the American Civil War from 1862–1865...

to help former slaves in Port Royal, South Carolina

Port Royal, South Carolina

Port Royal is a town in Beaufort County, South Carolina, United States. Largely because of annexation of surrounding areas , the population of Port Royal rose from 3,950 in 2000 to 10,678 in 2010, a 170% increase. As defined by the U.S...

. When the Civil War ended, Campbell was assigned to the Sea Islands

Sea Islands

The Sea Islands are a chain of tidal and barrier islands on the Atlantic Ocean coast of the United States. They number over 100, and are located between the mouths of the Santee and St. Johns Rivers along the coast of the U.S...

of Georgia, where he engaged in an apparently successful land reform program for the benefit of the freedmen. He eventually became vice-chair of the Georgia Republican Party, a state senator and the head of an African-American militia which he hoped to use against the Ku Klux Klan

Ku Klux Klan

Ku Klux Klan, often abbreviated KKK and informally known as the Klan, is the name of three distinct past and present far-right organizations in the United States, which have advocated extremist reactionary currents such as white supremacy, white nationalism, and anti-immigration, historically...

.

Arkansas

William Hines Furbush, born a slave in Kentucky in 1839, received an education in Ohio, and migrated to Helena, ArkansasHelena, Arkansas

Helena is the eastern portion of Helena-West Helena, Arkansas, a city in Phillips County, Arkansas. As of the 2000 census, this portion of the city population was 6,323. Helena was the county seat of Phillips County until January 1, 2006, when it merged its government and city limits with...

in 1862. Back in Ohio in February 1865, he joined the Forty-second Colored Infantry at Columbus

Columbus, Ohio

Columbus is the capital of and the largest city in the U.S. state of Ohio. The broader metropolitan area encompasses several counties and is the third largest in Ohio behind those of Cleveland and Cincinnati. Columbus is the third largest city in the American Midwest, and the fifteenth largest city...

. After the war Furbush migrated to Liberia

Liberia

Liberia , officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country in West Africa. It is bordered by Sierra Leone on the west, Guinea on the north and Côte d'Ivoire on the east. Liberia's coastline is composed of mostly mangrove forests while the more sparsely populated inland consists of forests that open...

through the American Colonization Society. He returned to Ohio after 18 months and moved back to Arkansas by 1870.[Wintory 2004] Furbush was elected to two terms in the Arkansas House of Representatives, 1873–74 (Phillips County) and 1879–80 (Lee County).

In 1873 the state passed a civil rights law. Furbush and three other black leaders, including the bill's primary sponsor state Sen. Richard A. Dawson, sued a Little Rock

Little Rock, Arkansas

Little Rock is the capital and the largest city of the U.S. state of Arkansas. The Metropolitan Statistical Area had a population of 699,757 people in the 2010 census...

barkeeper for refusing to serve the group service. The suit resulted in the only successful Reconstruction prosecution under the state's civil rights law. In the legislature Furbush worked to create a new county, Lee, from portions of Phillips, Crittenden, Monroe

Monroe County, Arkansas

Monroe County is a county located in the U.S. state of Arkansas. As of 2010, the population is 8,149. The county seat is Clarendon, while its largest city is Brinkley...

and St. Francis counties.

Following the end of his 1873 legislative term, Furbush was appointed sheriff by Republican Governor Elisha Baxter. Furbush won reelection as sheriff twice and served from 1873 to 1878. During his term, he adopted a policy of "fusion," a post-Reconstruction power-sharing compromise between Democrats and Republicans. Furbush was originally elected as a Republican, but he switched to the Democratic Party at the end of his time as sheriff. In 1878, Furbush was again elected to the Arkansas House. His election is noteworthy because he was elected as a black Democrat in an election season notorious for white intimidation of black and Republican voters in black-majority eastern Arkansas. Furbush is the first known black Democrat elected to the Arkansas General Assembly.

In March 1879 Furbush left Arkansas for Colorado

Colorado

Colorado is a U.S. state that encompasses much of the Rocky Mountains as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the western edge of the Great Plains...

, where he worked as an assayer and barber. In Bonanza, Colorado

Bonanza, Colorado

The town of Bonanza is a Statutory Town located in Saguache County, Colorado, United States. Bonanza is a largely abandoned former silver mining town. Bonanza is a Spanish language word meaning a rich mineral deposit. The town population was 16 at the U.S. Census 2010, making Bonanza the second...

he avoided a lynch mob after shooting and killing a town constable. At the trial he was acquitted of murder. He returned to Little Rock, Arkansas, by 1888, following another stay in Ohio.

In 1889, he and E. A. Fulton, a fellow black Democrat, announced plans for the National Democrat, a party weekly intended to attract black voters to the Democratic Party. After failing to attract black voters and following white Democrats' passage of the Arkansas 1891 Election Law that disfranchised most black voters, Furbush left the state. He traveled to South Carolina and Georgia, but they soon disfranchised black voters, too.

The last stop of Furbush was in October 1901 at Marion, Indiana

Marion, Indiana

Marion is a city in Grant County, Indiana, United States. The population was 29,948 as of the 2010 census. The city is the county seat of Grant County...

's National Home for Disabled Veterans. He died there on September 3, 1902. He was interred at the Marion National Cemetery.

Texas

Carpetbaggers were least visible in Texas. Republicans were in power from 1867 to January 1874. Only one state official and one justice of the state supreme court were Northerners. About 13% to 21% of district court judges were Northerners, along with about 10% of the delegates who wrote the Reconstruction constitution of 1869. Of the 142 men who served in the 12th Legislature, only 12 to 29 were Northerners. At the county level, they included about 10% of the commissioners, county judges and sheriffs.New Yorker George T. Ruby was sent as an agent by the Freedmen's Bureau to Galveston, Texas

Galveston, Texas

Galveston is a coastal city located on Galveston Island in the U.S. state of Texas. , the city had a total population of 47,743 within an area of...

, where he settled. Later elected a Texas state senator, Ruby was instrumental in various economic development schemes and in efforts to organize African-American dockworkers into the Labor Union of Colored Men. When Reconstruction ended Ruby became a leader of the Exoduster movement, which encouraged Southern blacks to homestead in Kansas

Kansas

Kansas is a US state located in the Midwestern United States. It is named after the Kansas River which flows through it, which in turn was named after the Kansa Native American tribe, which inhabited the area. The tribe's name is often said to mean "people of the wind" or "people of the south...

to escape white supremacist violence and the oppression of segregation.

Historiography

The Dunning schoolDunning School

The Dunning School refers to a group of historians who shared a historiographical school of thought regarding the Reconstruction period of American history .-About:...

of American historians (1900–1950) viewed carpetbaggers unfavorably, arguing that they degraded the political and business culture. The revisionist school in the 1930s called them stooges of Northern business interests. After 1960 the neoabolitionist

Neoabolitionist

Neoabolitionist is a term used by some historians to refer to the heightened activity of the civil rights movement in the late 1950s and early 1960s...

school emphasized their moral courage.

United Kingdom

Carpetbagging was used as a term in Great BritainGreat Britain

Great Britain or Britain is an island situated to the northwest of Continental Europe. It is the ninth largest island in the world, and the largest European island, as well as the largest of the British Isles...

in the late 1990s during the wave of demutualization

Demutualization

Demutualization is the process by which a customer-owned mutual organization or co-operative changes legal form to a joint stock company. It is sometimes called stocking or privatization. As part of the demutualization process, members of a mutual usually receive a "windfall" payout, in the form...

s of building societies. It indicated members of the public who joined mutual societies with the hope of making a quick profit from the conversion.

Contemporarily speaking, the term carpetbagger refers to roving financial opportunists, often of modest means, who spot investment opportunities and aim to benefit from a set of circumstances to which they are not ordinarily entitled. In recent years the best opportunities for carpetbaggers have come from opening membership accounts at building societies for as little as £1, to qualify for windfalls running into thousands of pounds from the process of conversion and takeover. The influx of such transitory ‘token’ members as carpetbaggers, took advantage of these nugatory deposit criteria, often to instigate or accelerate the trend towards wholesale demutualisation.

Investors in these mutuals would receive shares in the new public companies, usually distributed at a flat rate, thus equally benefiting small and large investors, and providing a broad incentive for members to vote for conversion-advocating leadership candidates. The word was first used in this context in early 1997 by the chief executive of the Woolwich Building Society

The Woolwich

The Woolwich is a trademark of the British bank Barclays. Originally the 'Woolwich' was the Woolwich Building Society before it demutualised and became a public limited company in 1997...

, who announced the society's conversion with rules removing the most recent new savers' entitlement to potential windfalls and stated in a media interview, "I have no qualms about disenfranchising carpetbaggers."

Between 1997 and 2002, a group of pro-demutualization supporters “Members for Conversion” operated a website, carpetbagger.com, which highlighted the best ways of opening share accounts with UK building societies, and organized demutualization resolutions.

This led many building societies to implement anti-carpetbagging policies, such as not accepting new deposits from customers who lived outside the normal operating area of the society.

World War II

During World War II, the U.S. Office of Strategic ServicesOffice of Strategic Services

The Office of Strategic Services was a United States intelligence agency formed during World War II. It was the wartime intelligence agency, and it was a predecessor of the Central Intelligence Agency...

surreptitiously supplied necessary tools and material to anti-Nazi resistance groups in Europe. The OSS called this effort Operation Carpetbagger

Operation Carpetbagger

During World War II, Operation Carpetbagger was a general term used for the aerial resupply of weapons and other matériel to resistance fighters in France, Italy and the Low Countries by the U.S...

, and the modified B-24 aircraft used for the night-time missions were referred to as "carpetbaggers." (Among other special features, they were painted a glossy black to make them less visible to searchlights.) Between January and September 1944, Operation Carpetbagger ran 1,860 sorties between RAF Harrington

RAF Harrington

RAF Harrington is a former World War II airfield in England. The field is located west of Kettering in Northamptonshire south of the village of Harrington across the B576 road, now the A14.-USAAF use:...

, England, and various points in occupied Europe.

Australia

In Australia, the term "carpetbagger" refers to unscrupulous dealers and business managers in Indigenous Australian art.The term "carpetbagger" was also used by John Fahey

John Fahey (politician)

John Joseph Fahey, AC is a former Premier of New South Wales and Federal Minister for Finance in Australia. John Fahey is currently the President of the World Anti-Doping Agency. He was a member of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly from 1984 to 1996 and the federal House of Representatives...

, a former Premier of New South Wales and federal Liberal finance minister, in the context of shoddy "tradespeople" who travelled to Queensland to take advantage of victims following the 2011 Queensland floods.