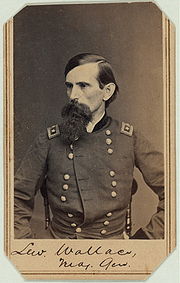

Lew Wallace

Encyclopedia

Lewis "Lew" Wallace was an American lawyer, Union

general in the American Civil War

, territorial governor and statesman, politician and author. Wallace served as Governor of the New Mexico Territory

at the time of the Lincoln County War

and worked to bring an end to the fighting.

Of his novels and biographies, he is best-known for his historical novel Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ (1880), a bestselling book since its publication, and considered "the most influential Christian book of the nineteenth century." It has been adapted four times for films.

, to David Wallace

and Esther French Test Wallace. His father was a graduate of the United States Military Academy

and served as lieutenant governor and Indiana Governor

. When Wallace's father was elected as lieutenant governor of Indiana, he moved his family to Covington, Indiana

. Wallace's autobiography contains many stories from his boyhood in Covington, including the account of the death of his mother in 1834. In 1836, at the age of nine, he joined his brother in Crawfordsville, Indiana

, where he briefly attended Wabash Preparatory School. His father remarried, to Zerelda Gray Sanders Wallace

, a prominent suffragist and temperance

advocate, who was stepmother to the boys. Lew Wallace rejoined his father in Indianapolis

.

In 1846 at the start of the Mexican-American War, Wallace was studying law. He left that to raise a company of militia and was elected a second lieutenant in the 1st Indiana Infantry regiment. He rose to the position of regimental adjutant and the rank of first lieutenant, serving in the army of Zachary Taylor

, although he personally did not participate in combat. After hostilities, he was mustered out of the volunteer service on June 15, 1847.

in 1849. In 1851 he was elected prosecuting attorney of the First Congressional District of Indiana. In 1856, he was elected to the Indiana State Senate after moving his residence to Crawfordsville.

. They had one son, Henry Lane Wallace (born February 17, 1853).

, Wallace was appointed state adjutant general

and helped raise troops in Indiana. On April 25, 1861, he was appointed Colonel

of the 11th Indiana Infantry. After brief service in western Virginia, he was promoted to brigadier general

of volunteers on September 3 and given the command of a brigade.

, Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant

sent two wooden gunboats (timberclads

) down the Tennessee River for one last reconnaissance of the fort with Wallace aboard. In his report, Wallace noted an officer in the fort who was watching the Union ships as inquisitively as they were watching him. Little did Wallace know at that time the officer was Brig. Gen. Lloyd Tilghman

, whom Wallace would replace as commander of Fort Henry in a few days. During the campaign Wallace's brigade was attached to Brig. Gen. Charles F. Smith's division and occupied Fort Heiman across the river from Fort Henry. Grant's superior, Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, was concerned about Confederate reinforcements retaking the forts, so Grant left Wallace with his brigade in command at Fort Henry while the rest of the army moved overland toward Fort Donelson

.

Displeased to have been left behind, Wallace prepared his troops ready to move out at a moment's notice. The order came on February 14, and when Wallace arrived along the Cumberland River, he was placed in charge of organizing a division

Displeased to have been left behind, Wallace prepared his troops ready to move out at a moment's notice. The order came on February 14, and when Wallace arrived along the Cumberland River, he was placed in charge of organizing a division

of reinforcements arriving on transports. He organized two full brigades and a third incomplete, and took up position in the center of Grant's lines besieging Fort Donelson. During the fierce Confederate

assault on February 15, Wallace coolly acted on his own initiative to send a brigade to reinforce the beleaguered division of Brig. Gen. John A. McClernand, despite orders from Grant to avoid a general engagement. This action was key in stabilizing the Union defensive line. After the Confederate assault had been checked, Wallace led a counter attack which retook the ground that was lost. He was promoted to major general

to rank from March 21.

, where he continued as the 3rd Division commander under Grant. Wallace's division had been left in reserve. The 3rd Brigade commanded by Col. Charles Whittlesey was at Stoney Lonesome near Adamsville, Tennessee. Col. Morgan L. Smith's 1st Brigade and Col. John M. Thayer's Second Brigade were both located at Crump's Landing, five miles north of Pittsburg Landing, to the rear of the Union line. At about 6 a.m. on April 6, 1862, when Grant's army was surprised and virtually routed by the sudden appearance of the Confederate States Army

under Albert Sidney Johnston

, Grant sent orders for Wallace to move his division up to support the division of Brig. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman

located at Shiloh Church.

Here, the controversy begins. Wallace claimed that Grant's orders were unsigned, hastily written, and overly vague. There were two main routes by which Wallace could move his unit to the front, and Grant (according to Wallace) did not specify which one he should take. Wallace chose to take the "upper" path, which was much less used and considered in better condition, and which would lead him to reinforce the "right" side of Sherman's last known (initial) position at Shiloh Church. Grant later claimed that he had specified that Wallace take the "lower" path (River Road), although circumstantial evidence suggests that Grant had forgotten that more than one path existed.

Wallace arrived almost at the end of his march only to find that Sherman had been forced back, and was no longer where he expected to find him. Sherman had been pushed back so far that Wallace was to the rear of the advancing Southern troops. A messenger from Grant arrived at 11:30 a.m. with word that Grant was wondering where Wallace was, and why he had not arrived near Pittsburg Landing, where the Union was making its stand. Wallace was confused. He believed he could launch a viable attack from where he was and hit the Confederates in the rear, but decided to countermarch his troops back along the same route and via a circuitous path direct to the bridge crossing Snake and Owl Creeks. Rather than realigning his troops so that the rear guard would be in the front, Wallace chose to countermarch his column; he argued that his artillery would have been greatly out of position to support the infantry when it would arrive on the field.

Wallace marched back to the mid-point on the "upper" road. He proceeded to march over a new third path that would intersect with the lower road to join the army on the field, but the road had been left in terrible conditions by recent rainstorms and previous Union marches. Progress was extremely slow, marching and countermarching a total of 15 miles in six and a half hours. Wallace finally arrived at Grant's position at about 7 p.m., at a time when the fighting was practically over. Grant was not pleased. The Union won the battle the following day. Wallace's division held the extreme right of the Union line and was the first to attack on April 7.

At first, there was little fallout from this. Wallace was the youngest general of his rank in the army and was something of a "golden boy." Soon, however, civilians in the North

At first, there was little fallout from this. Wallace was the youngest general of his rank in the army and was something of a "golden boy." Soon, however, civilians in the North

began to hear the news of the horrible casualties at Shiloh, and the Army needed explanations. Both Grant and his superior, Halleck, placed the blame squarely on Wallace, saying that his incompetence in moving up the reserves had nearly cost them the battle. Sherman, for his part, remained silent on the issue. Wallace was removed from his command in June and reassigned to command the defense of Cincinnati

in the Department of the Ohio

during Braxton Bragg

's incursion into Kentucky

.

in Maryland, part of the Valley Campaigns of 1864

. Although the some 5,800-man force under his command (mostly hundred-days' men amalgamated from the VIII Corps) and the division of James B. Ricketts

from VI Corps was defeated by Confederate General Jubal A. Early, who had some 15,000 troops, Wallace was able to delay Early's advance toward Washington, D.C.

for an entire day. This gave the city defenses time to organize and repel Early, who arrived at Fort Stevens in Washington at around noon on July 11, two days after defeating Wallace at Monocacy, the northernmost Confederate victory of the war.

General Grant relieved Wallace of his command after learning of the defeat of Monocacy, but re-instated him two weeks later. Grant's memoirs praised Wallace's delaying tactics at Monocacy:

Wallace suffered greatly by the loss of his reputation as a result of Shiloh. He worked all his life to change public opinion about his role in the battle, going so far as to beg Grant to "set things right" in his memoir. Grant, like many of the others Wallace importuned, refused to change his opinion.

Later in the war, Wallace directed the U.S. government's secret efforts to aid Mexico in expelling the French occupation forces which had seized control of their country in 1864. He participated in the military commission trial of the Lincoln assassination conspirators

, as well as the court-martial

of Henry Wirz

, the commandant in charge of the South's Andersonville prison camp.

Wallace held a number of important political posts during the 1870s and 1880s. He was appointed as governor of New Mexico Territory

from 1878 to 1881, during a time of violence and political corruption. He was appointed as U.S. Minister

to the Ottoman Empire

from 1881 to 1885.

As governor, Wallace offered amnesty to many men involved in the Lincoln County War

. In the process he met with the outlawed Billy the Kid

. On March 17, 1879, the pair arranged that the Kid would act as an informant and testify against others involved in the Lincoln County War, and, it has been claimed, that in return the Kid would be "scot free with a pardon in [his] pocket for all [his] misdeeds." . According to this account, Wallace, facing the political forces then ruling New Mexico, was unable to come through on his end of the bargain. The Kid went back to his outlaw ways, and killed additional men.

In the 21st century, supporters of McCarty made a request for a posthumous pardon, based on the claim of a pardon promised and not delivered by Wallace, to then-Governor of New Mexico, Bill Richardson. On December 31, 2010, on the eve of leaving office, Richardson turned down the pardon request, citing a "lack of conclusiveness and the historical ambiguity" over Wallace's actions. Descendants of Wallace and Garrett were among those who opposed the pardon.

Taking up writing again after the war, Wallace published his first novel in 1873. While serving as governor, Wallace completed his second novel, which made him famous: Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ (1880). It became the best-selling American novel of the 19th century, surpassing Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin

and is considered "the most influential Christian book of the ... century." The book has never been out of print and has been adapted for film four times. The historian Victor Davis Hanson

has argued that the novel drew from Wallace's life, particularly his experiences at Shiloh, and the damage it did to his reputation. The book's main character, Judah Ben-Hur, accidentally causes injury to a high-ranking commander, for which he and his family suffer tribulations and calumny. He first seeks revenge, and then redemption.

Wallace went on to publish several novels and biographies, plus his memoir; but Ben-Hur was his most important book. He designed a writing study, built 1895-1898, near his residence in Crawfordsville, Indiana

. Now called the General Lew Wallace Study

, it has been designated a National Historic Landmark

and is operated as a house museum, open to the public.

Wallace died, likely from cancer

, in Crawfordsville and is buried there in Oak Hill Cemetery.

Union Army

The Union Army was the land force that fought for the Union during the American Civil War. It was also known as the Federal Army, the U.S. Army, the Northern Army and the National Army...

general in the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

, territorial governor and statesman, politician and author. Wallace served as Governor of the New Mexico Territory

New Mexico Territory

thumb|right|240px|Proposed boundaries for State of New Mexico, 1850The Territory of New Mexico was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from September 9, 1850, until January 6, 1912, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of...

at the time of the Lincoln County War

Lincoln County War

The Lincoln County War was a 19th-century range war between two factions during the Old West period. Numerous notable figures of the American West were involved, including Billy the Kid, aka William Henry McCarty; sheriffs William Brady and Pat Garrett; cattle rancher John Chisum, lawyer and...

and worked to bring an end to the fighting.

Of his novels and biographies, he is best-known for his historical novel Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ (1880), a bestselling book since its publication, and considered "the most influential Christian book of the nineteenth century." It has been adapted four times for films.

Early life and career

Wallace was born in Brookville, IndianaBrookville, Indiana

Brookville is a town in Brookville Township, Franklin County, Indiana, United States. The population was 2,625 at the 2000 census. The town is the county seat of Franklin County.-Geography:...

, to David Wallace

David Wallace (governor)

David Wallace was the sixth Governor of the US state of Indiana. The Panic of 1837 occurred just before his election and the previous administration, which he had been part of, had taken on a large public debt. During his term the state entered a severe financial crisis that crippled the state's...

and Esther French Test Wallace. His father was a graduate of the United States Military Academy

United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy at West Point is a four-year coeducational federal service academy located at West Point, New York. The academy sits on scenic high ground overlooking the Hudson River, north of New York City...

and served as lieutenant governor and Indiana Governor

Governor of Indiana

The Governor of Indiana is the chief executive of the state of Indiana. The governor is elected to a four-year term, and responsible for overseeing the day-to-day management of the functions of many agencies of the Indiana state government. The governor also shares power with other statewide...

. When Wallace's father was elected as lieutenant governor of Indiana, he moved his family to Covington, Indiana

Covington, Indiana

Covington is a city located on the western edge of Fountain County, Indiana. The population was 2,645 at the 2010 census. The city is the county seat of Fountain County.-Geography:Covington is located at ....

. Wallace's autobiography contains many stories from his boyhood in Covington, including the account of the death of his mother in 1834. In 1836, at the age of nine, he joined his brother in Crawfordsville, Indiana

Crawfordsville, Indiana

Crawfordsville is a city in Union Township, Montgomery County, Indiana, United States. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 15,915. The city is the county seat of Montgomery County...

, where he briefly attended Wabash Preparatory School. His father remarried, to Zerelda Gray Sanders Wallace

Zerelda G. Wallace

Zerelda Gray Sanders Wallace was an early temperance and women's suffrage leader, a charter member of Central Christian Church of Indianapolis, and stepmother of General Lew Wallace, author of Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ.-Early life and family:Born Zerelda Gray Sanders, August 7, 1817 in...

, a prominent suffragist and temperance

Temperance movement

A temperance movement is a social movement urging reduced use of alcoholic beverages. Temperance movements may criticize excessive alcohol use, promote complete abstinence , or pressure the government to enact anti-alcohol legislation or complete prohibition of alcohol.-Temperance movement by...

advocate, who was stepmother to the boys. Lew Wallace rejoined his father in Indianapolis

Indianapolis

Indianapolis is the capital of the U.S. state of Indiana, and the county seat of Marion County, Indiana. As of the 2010 United States Census, the city's population is 839,489. It is by far Indiana's largest city and, as of the 2010 U.S...

.

In 1846 at the start of the Mexican-American War, Wallace was studying law. He left that to raise a company of militia and was elected a second lieutenant in the 1st Indiana Infantry regiment. He rose to the position of regimental adjutant and the rank of first lieutenant, serving in the army of Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor was the 12th President of the United States and an American military leader. Initially uninterested in politics, Taylor nonetheless ran as a Whig in the 1848 presidential election, defeating Lewis Cass...

, although he personally did not participate in combat. After hostilities, he was mustered out of the volunteer service on June 15, 1847.

Career

Wallace was admitted to the barBar association

A bar association is a professional body of lawyers. Some bar associations are responsible for the regulation of the legal profession in their jurisdiction; others are professional organizations dedicated to serving their members; in many cases, they are both...

in 1849. In 1851 he was elected prosecuting attorney of the First Congressional District of Indiana. In 1856, he was elected to the Indiana State Senate after moving his residence to Crawfordsville.

Marriage and family

On May 6, 1852, Wallace married Susan Arnold ElstonSusan Wallace

Susan Arnold Elston Wallace was an American author and poet.-Biography:Susan Wallace was born in Crawfordsville, Indiana to wealthy and influential parents, Isaac Compton and Maria Eveline Elston on December 25, 1830. She was educated in Crawfordsville and Poughkeepsie, New York...

. They had one son, Henry Lane Wallace (born February 17, 1853).

Civil War

At the start of the American Civil WarAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

, Wallace was appointed state adjutant general

Adjutant general

An Adjutant General is a military chief administrative officer.-Imperial Russia:In Imperial Russia, the General-Adjutant was a Court officer, who was usually an army general. He served as a personal aide to the Tsar and hence was a member of the H. I. M. Retinue...

and helped raise troops in Indiana. On April 25, 1861, he was appointed Colonel

Colonel (United States)

In the United States Army, Air Force, and Marine Corps, colonel is a senior field grade military officer rank just above the rank of lieutenant colonel and just below the rank of brigadier general...

of the 11th Indiana Infantry. After brief service in western Virginia, he was promoted to brigadier general

Brigadier general (United States)

A brigadier general in the United States Army, Air Force, and Marine Corps, is a one-star general officer, with the pay grade of O-7. Brigadier general ranks above a colonel and below major general. Brigadier general is equivalent to the rank of rear admiral in the other uniformed...

of volunteers on September 3 and given the command of a brigade.

Forts Henry & Donelson

In February 1862, while preparing for an advance against Fort HenryFort Henry

Fort Henry is the name of:*Fort Henry , a 1646 fort near present-day Petersburg, Virginia*Fort Henry , a 1774 fort near present–day Wheeling, West Virginia...

, Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant was the 18th President of the United States as well as military commander during the Civil War and post-war Reconstruction periods. Under Grant's command, the Union Army defeated the Confederate military and ended the Confederate States of America...

sent two wooden gunboats (timberclads

Timberclad warship

A timberclad warship is a kind of mid 19th century river gunboat.They were based upon a similar design as ironclad warships however had timber armour in place of iron.-See also:*Cottonclad warship*Battle of Fort Henry*USS Essex...

) down the Tennessee River for one last reconnaissance of the fort with Wallace aboard. In his report, Wallace noted an officer in the fort who was watching the Union ships as inquisitively as they were watching him. Little did Wallace know at that time the officer was Brig. Gen. Lloyd Tilghman

Lloyd Tilghman

Lloyd Tilghman was a railroad construction engineer and a Confederate general in the American Civil War, killed at the Battle of Champion Hill...

, whom Wallace would replace as commander of Fort Henry in a few days. During the campaign Wallace's brigade was attached to Brig. Gen. Charles F. Smith's division and occupied Fort Heiman across the river from Fort Henry. Grant's superior, Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, was concerned about Confederate reinforcements retaking the forts, so Grant left Wallace with his brigade in command at Fort Henry while the rest of the army moved overland toward Fort Donelson

Fort Donelson

Fort Donelson was a fortress built by the Confederacy during the American Civil War to control the Cumberland River leading to the heart of Tennessee, and the heart of the Confederacy.-History:...

.

Division (military)

A division is a large military unit or formation usually consisting of between 10,000 and 20,000 soldiers. In most armies, a division is composed of several regiments or brigades, and in turn several divisions typically make up a corps...

of reinforcements arriving on transports. He organized two full brigades and a third incomplete, and took up position in the center of Grant's lines besieging Fort Donelson. During the fierce Confederate

Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army was the army of the Confederate States of America while the Confederacy existed during the American Civil War. On February 8, 1861, delegates from the seven Deep South states which had already declared their secession from the United States of America adopted the...

assault on February 15, Wallace coolly acted on his own initiative to send a brigade to reinforce the beleaguered division of Brig. Gen. John A. McClernand, despite orders from Grant to avoid a general engagement. This action was key in stabilizing the Union defensive line. After the Confederate assault had been checked, Wallace led a counter attack which retook the ground that was lost. He was promoted to major general

Major general (United States)

In the United States Army, United States Marine Corps, and United States Air Force, major general is a two-star general-officer rank, with the pay grade of O-8. Major general ranks above brigadier general and below lieutenant general...

to rank from March 21.

Shiloh

Wallace's most controversial command came at the Battle of ShilohBattle of Shiloh

The Battle of Shiloh, also known as the Battle of Pittsburg Landing, was a major battle in the Western Theater of the American Civil War, fought April 6–7, 1862, in southwestern Tennessee. A Union army under Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant had moved via the Tennessee River deep into Tennessee and...

, where he continued as the 3rd Division commander under Grant. Wallace's division had been left in reserve. The 3rd Brigade commanded by Col. Charles Whittlesey was at Stoney Lonesome near Adamsville, Tennessee. Col. Morgan L. Smith's 1st Brigade and Col. John M. Thayer's Second Brigade were both located at Crump's Landing, five miles north of Pittsburg Landing, to the rear of the Union line. At about 6 a.m. on April 6, 1862, when Grant's army was surprised and virtually routed by the sudden appearance of the Confederate States Army

Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army was the army of the Confederate States of America while the Confederacy existed during the American Civil War. On February 8, 1861, delegates from the seven Deep South states which had already declared their secession from the United States of America adopted the...

under Albert Sidney Johnston

Albert Sidney Johnston

Albert Sidney Johnston served as a general in three different armies: the Texas Army, the United States Army, and the Confederate States Army...

, Grant sent orders for Wallace to move his division up to support the division of Brig. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman was an American soldier, businessman, educator and author. He served as a General in the Union Army during the American Civil War , for which he received recognition for his outstanding command of military strategy as well as criticism for the harshness of the "scorched...

located at Shiloh Church.

Here, the controversy begins. Wallace claimed that Grant's orders were unsigned, hastily written, and overly vague. There were two main routes by which Wallace could move his unit to the front, and Grant (according to Wallace) did not specify which one he should take. Wallace chose to take the "upper" path, which was much less used and considered in better condition, and which would lead him to reinforce the "right" side of Sherman's last known (initial) position at Shiloh Church. Grant later claimed that he had specified that Wallace take the "lower" path (River Road), although circumstantial evidence suggests that Grant had forgotten that more than one path existed.

Wallace arrived almost at the end of his march only to find that Sherman had been forced back, and was no longer where he expected to find him. Sherman had been pushed back so far that Wallace was to the rear of the advancing Southern troops. A messenger from Grant arrived at 11:30 a.m. with word that Grant was wondering where Wallace was, and why he had not arrived near Pittsburg Landing, where the Union was making its stand. Wallace was confused. He believed he could launch a viable attack from where he was and hit the Confederates in the rear, but decided to countermarch his troops back along the same route and via a circuitous path direct to the bridge crossing Snake and Owl Creeks. Rather than realigning his troops so that the rear guard would be in the front, Wallace chose to countermarch his column; he argued that his artillery would have been greatly out of position to support the infantry when it would arrive on the field.

Wallace marched back to the mid-point on the "upper" road. He proceeded to march over a new third path that would intersect with the lower road to join the army on the field, but the road had been left in terrible conditions by recent rainstorms and previous Union marches. Progress was extremely slow, marching and countermarching a total of 15 miles in six and a half hours. Wallace finally arrived at Grant's position at about 7 p.m., at a time when the fighting was practically over. Grant was not pleased. The Union won the battle the following day. Wallace's division held the extreme right of the Union line and was the first to attack on April 7.

Northern United States

Northern United States, also sometimes the North, may refer to:* A particular grouping of states or regions of the United States of America. The United States Census Bureau divides some of the northernmost United States into the Midwest Region and the Northeast Region...

began to hear the news of the horrible casualties at Shiloh, and the Army needed explanations. Both Grant and his superior, Halleck, placed the blame squarely on Wallace, saying that his incompetence in moving up the reserves had nearly cost them the battle. Sherman, for his part, remained silent on the issue. Wallace was removed from his command in June and reassigned to command the defense of Cincinnati

Defense of Cincinnati

The Defense of Cincinnati occurred during what is now referred to as the Confederate Heartland Offensive of American Civil War from September 1 through September 13, 1862, when Cincinnati, Ohio, was threatened by Confederate forces....

in the Department of the Ohio

Department of the Ohio

The Department of the Ohio was an administrative military district created by the United States War Department early in the American Civil War to administer the troops in the Northern states near the Ohio River.General Orders No...

during Braxton Bragg

Braxton Bragg

Braxton Bragg was a career United States Army officer, and then a general in the Confederate States Army—a principal commander in the Western Theater of the American Civil War and later the military adviser to Confederate President Jefferson Davis.Bragg, a native of North Carolina, was...

's incursion into Kentucky

Kentucky

The Commonwealth of Kentucky is a state located in the East Central United States of America. As classified by the United States Census Bureau, Kentucky is a Southern state, more specifically in the East South Central region. Kentucky is one of four U.S. states constituted as a commonwealth...

.

Later service

Wallace's most notable service came in July 1864 at the Battle of MonocacyBattle of Monocacy

The Battle of Monocacy was fought on July 9, 1864, just outside Frederick, Maryland, as part of the Valley Campaigns of 1864, in the American Civil War. Confederate forces under Lt. Gen. Jubal A. Early defeated Union forces under Maj. Gen. Lew Wallace...

in Maryland, part of the Valley Campaigns of 1864

Valley Campaigns of 1864

The Valley Campaigns of 1864 were American Civil War operations and battles that took place in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia from May to October 1864. Military historians divide this period into three separate campaigns, but it is useful to consider the three together and how they...

. Although the some 5,800-man force under his command (mostly hundred-days' men amalgamated from the VIII Corps) and the division of James B. Ricketts

James B. Ricketts

James Brewerton Ricketts was a career officer in the United States Army, serving as a Union Army general in the Eastern Theater during the American Civil War.-Early life and career:...

from VI Corps was defeated by Confederate General Jubal A. Early, who had some 15,000 troops, Wallace was able to delay Early's advance toward Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

for an entire day. This gave the city defenses time to organize and repel Early, who arrived at Fort Stevens in Washington at around noon on July 11, two days after defeating Wallace at Monocacy, the northernmost Confederate victory of the war.

General Grant relieved Wallace of his command after learning of the defeat of Monocacy, but re-instated him two weeks later. Grant's memoirs praised Wallace's delaying tactics at Monocacy:

"If Early had been but one day earlier, he might have entered the capital before the arrival of the reinforcements I had sent. ... General Wallace contributed on this occasion by the defeat of the troops under him, a greater benefit to the cause than often falls to the lot of a commander of an equal force to render by means of a victory."

Wallace suffered greatly by the loss of his reputation as a result of Shiloh. He worked all his life to change public opinion about his role in the battle, going so far as to beg Grant to "set things right" in his memoir. Grant, like many of the others Wallace importuned, refused to change his opinion.

Later in the war, Wallace directed the U.S. government's secret efforts to aid Mexico in expelling the French occupation forces which had seized control of their country in 1864. He participated in the military commission trial of the Lincoln assassination conspirators

Abraham Lincoln assassination

The assassination of United States President Abraham Lincoln took place on Good Friday, April 14, 1865, as the American Civil War was drawing to a close. The assassination occurred five days after the commanding General of the Army of Northern Virginia, Robert E. Lee, and his battered Army of...

, as well as the court-martial

Court-martial

A court-martial is a military court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of members of the armed forces subject to military law, and, if the defendant is found guilty, to decide upon punishment.Most militaries maintain a court-martial system to try cases in which a breach of...

of Henry Wirz

Henry Wirz

Heinrich Hartmann Wirz better known as Henry Wirz was a Confederate officer in the American Civil War...

, the commandant in charge of the South's Andersonville prison camp.

Post-war career

Wallace resigned from the army on November 30, 1865. After war's end, he continued to try to help the Mexican army expel the French, and was offered a major general's commission in the Mexican army. Multiple promises by the Mexicans were never delivered upon, forcing Wallace into deep financial debt.Wallace held a number of important political posts during the 1870s and 1880s. He was appointed as governor of New Mexico Territory

New Mexico Territory

thumb|right|240px|Proposed boundaries for State of New Mexico, 1850The Territory of New Mexico was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from September 9, 1850, until January 6, 1912, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of...

from 1878 to 1881, during a time of violence and political corruption. He was appointed as U.S. Minister

United States Ambassador to Turkey

The United States of America has maintained many high level contacts with Turkey since the nineteenth century.-Chargé d'Affaires:*George W. Erving *David Porter -Minister Resident:*David Porter *Dabney Smith Carr...

to the Ottoman Empire

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

from 1881 to 1885.

As governor, Wallace offered amnesty to many men involved in the Lincoln County War

Lincoln County War

The Lincoln County War was a 19th-century range war between two factions during the Old West period. Numerous notable figures of the American West were involved, including Billy the Kid, aka William Henry McCarty; sheriffs William Brady and Pat Garrett; cattle rancher John Chisum, lawyer and...

. In the process he met with the outlawed Billy the Kid

Billy the Kid

William H. Bonney William H. Bonney William H. Bonney (born William Henry McCarty, Jr. est. November 23, 1859 – c. July 14, 1881, better known as Billy the Kid but also known as Henry Antrim, was a 19th-century American gunman who participated in the Lincoln County War and became a frontier...

. On March 17, 1879, the pair arranged that the Kid would act as an informant and testify against others involved in the Lincoln County War, and, it has been claimed, that in return the Kid would be "scot free with a pardon in [his] pocket for all [his] misdeeds." . According to this account, Wallace, facing the political forces then ruling New Mexico, was unable to come through on his end of the bargain. The Kid went back to his outlaw ways, and killed additional men.

In the 21st century, supporters of McCarty made a request for a posthumous pardon, based on the claim of a pardon promised and not delivered by Wallace, to then-Governor of New Mexico, Bill Richardson. On December 31, 2010, on the eve of leaving office, Richardson turned down the pardon request, citing a "lack of conclusiveness and the historical ambiguity" over Wallace's actions. Descendants of Wallace and Garrett were among those who opposed the pardon.

Taking up writing again after the war, Wallace published his first novel in 1873. While serving as governor, Wallace completed his second novel, which made him famous: Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ (1880). It became the best-selling American novel of the 19th century, surpassing Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin

Uncle Tom's Cabin

Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly is an anti-slavery novel by American author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Published in 1852, the novel "helped lay the groundwork for the Civil War", according to Will Kaufman....

and is considered "the most influential Christian book of the ... century." The book has never been out of print and has been adapted for film four times. The historian Victor Davis Hanson

Victor Davis Hanson

Victor Davis Hanson is an American military historian, columnist, political essayist and former classics professor, notable as a scholar of ancient warfare. He has been a commentator on modern warfare and contemporary politics for National Review and other media outlets...

has argued that the novel drew from Wallace's life, particularly his experiences at Shiloh, and the damage it did to his reputation. The book's main character, Judah Ben-Hur, accidentally causes injury to a high-ranking commander, for which he and his family suffer tribulations and calumny. He first seeks revenge, and then redemption.

Wallace went on to publish several novels and biographies, plus his memoir; but Ben-Hur was his most important book. He designed a writing study, built 1895-1898, near his residence in Crawfordsville, Indiana

Crawfordsville, Indiana

Crawfordsville is a city in Union Township, Montgomery County, Indiana, United States. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 15,915. The city is the county seat of Montgomery County...

. Now called the General Lew Wallace Study

General Lew Wallace Study

The General Lew Wallace Study & Museum, formerly known as the Ben-Hur Museum, is located in Crawfordsville, Indiana. It was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1976, and in 2008 was awarded a National Medal from the federal Institute of Museum and Library Services. The museum is associated...

, it has been designated a National Historic Landmark

National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark is a building, site, structure, object, or district, that is officially recognized by the United States government for its historical significance...

and is operated as a house museum, open to the public.

Wallace died, likely from cancer

Cancer

Cancer , known medically as a malignant neoplasm, is a large group of different diseases, all involving unregulated cell growth. In cancer, cells divide and grow uncontrollably, forming malignant tumors, and invade nearby parts of the body. The cancer may also spread to more distant parts of the...

, in Crawfordsville and is buried there in Oak Hill Cemetery.

Legacy and honors

- The state of Indiana commissioned a marble statue of Wallace dressed in a military uniform, which was made by the sculptor Andrew O'Connor. It was placed in the National Statuary Hall CollectionNational Statuary Hall CollectionThe National Statuary Hall Collection in the United States Capitol comprises statues donated by individual states to honor persons notable in their history...

in 1910. He is the only novelist honored in the hall.

Works

- The Fair God; or, The Last of the 'Tzins: A Tale of the Conquest of Mexico (Boston: James R. Osgood and Company), 1873.

- Commodus: An Historical Play ([Crawfordsville, IN?]: privately published by the author), 1876. (revised and reissued in the same year)

- Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ (New York: Harper & Brothers), 1880.

- The Boyhood of Christ (New York: Harper & Brothers), 1888.

- Life of Gen. Ben HarrisonBenjamin HarrisonBenjamin Harrison was the 23rd President of the United States . Harrison, a grandson of President William Henry Harrison, was born in North Bend, Ohio, and moved to Indianapolis, Indiana at age 21, eventually becoming a prominent politician there...

(bound with Life of Hon. Levi P. MortonLevi P. MortonLevi Parsons Morton was a Representative from New York and the 22nd Vice President of the United States . He also later served as the 31st Governor of New York.-Biography:...

, by George Alfred TownsendGeorge Alfred TownsendGeorge Alfred Townsend , was a noted war correspondent during the American Civil War, and a later novelist. Townsend wrote under the pen name "Gath", which was derived by adding an "H" to his initials, and inspired by the biblical passage II Samuel 1:20, "Tell it not in Gath, publish it not in the...

), (Cleveland: N. G. Hamilton & Co., Publishers), 1888. - Life of Gen. Ben Harrison (Philadelphia: Hubbard Brothers, Publishers), 1888.

- Life and Public Services of Hon. Benjamin Harrison, President of the U.S. With a Concise Biographical Sketch of Hon. Whitelaw Reid, Ex-Minister to France [by Murat Halstad] (Philadelphia: Edgewood Publishing Co.), 1892.

- The Prince of India; or, Why Constantinople Fell (New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers), 1893. 2 volumes

- The Wooing of Malkatoon [and] Commodus (New York: Harper and Brothers Publishers), 1898.

- Lew Wallace: An Autobiography (New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers), 1906. 2 volumes

See also

- List of American Civil War generals

- José María Jesús CarbajalJosé María Jesús CarbajalJosé María Jesús Carbajal was a Mexican freedom fighter, who opposed the Centralist government installed by Antonio López de Santa Anna. Carbajal was a direct descendant of Canary Islands settlers who emigrated to San Antonio, Texas in the 18th Century. As a teenager in San Antonio, he was...