History of navigation

Encyclopedia

Human migration

Human migration is physical movement by humans from one area to another, sometimes over long distances or in large groups. Historically this movement was nomadic, often causing significant conflict with the indigenous population and their displacement or cultural assimilation. Only a few nomadic...

and discovery of new lands by navigating the oceans, a few peoples have excelled as sea-faring explorers. Prominent examples are the Phoenicia

Phoenicia

Phoenicia , was an ancient civilization in Canaan which covered most of the western, coastal part of the Fertile Crescent. Several major Phoenician cities were built on the coastline of the Mediterranean. It was an enterprising maritime trading culture that spread across the Mediterranean from 1550...

ns, the ancient Greeks, the Persians

Persian people

The Persian people are part of the Iranian peoples who speak the modern Persian language and closely akin Iranian dialects and languages. The origin of the ethnic Iranian/Persian peoples are traced to the Ancient Iranian peoples, who were part of the ancient Indo-Iranians and themselves part of...

, the Arabians, the Norse

Norsemen

Norsemen is used to refer to the group of people as a whole who spoke what is now called the Old Norse language belonging to the North Germanic branch of Indo-European languages, especially Norwegian, Icelandic, Faroese, Swedish and Danish in their earlier forms.The meaning of Norseman was "people...

, the Austronesian people

Austronesian people

The Austronesian-speaking peoples are various populations in Oceania and Southeast Asia that speak languages of the Austronesian family. They include Taiwanese aborigines; the majority ethnic groups of East Timor, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Brunei, Madagascar, Micronesia, and Polynesia,...

s including the Malays, and the Polynesia

Polynesia

Polynesia is a subregion of Oceania, made up of over 1,000 islands scattered over the central and southern Pacific Ocean. The indigenous people who inhabit the islands of Polynesia are termed Polynesians and they share many similar traits including language, culture and beliefs...

ns and the Micronesia

Micronesia

Micronesia is a subregion of Oceania, comprising thousands of small islands in the western Pacific Ocean. It is distinct from Melanesia to the south, and Polynesia to the east. The Philippines lie to the west, and Indonesia to the southwest....

ns of the Pacific Ocean.

Mediterranean

Navigation in the Mediterranean made use of several techniques that sailors used to determine their location including, staying in sight of land, and understanding of the winds and their tendencies, knowledge of the sea’s currentsOcean current

An ocean current is a continuous, directed movement of ocean water generated by the forces acting upon this mean flow, such as breaking waves, wind, Coriolis effect, cabbeling, temperature and salinity differences and tides caused by the gravitational pull of the Moon and the Sun...

, and observation of the positions of the sun and stars. Sailing by hugging the coast would have been ill advised in the Mediterranean and the Aegean Sea

Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea[p] is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea located between the southern Balkan and Anatolian peninsulas, i.e., between the mainlands of Greece and Turkey. In the north, it is connected to the Marmara Sea and Black Sea by the Dardanelles and Bosporus...

due to the rocky and dangerous coastlines and because of the sudden storms that plague the area that could easily cause a ship to crash.

Greece

The Minoans of CreteCrete

Crete is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, and one of the thirteen administrative regions of Greece. It forms a significant part of the economy and cultural heritage of Greece while retaining its own local cultural traits...

are an example of an early Western civilization that used celestial navigation. Their palaces and mountaintop sanctuaries exhibit architectural features that align with the rising sun on the equinoxes, as well as the rising and setting of particular stars. The Minoans made sea voyages to the island of Thera

Santorini

Santorini , officially Thira , is an island located in the southern Aegean Sea, about southeast from Greece's mainland. It is the largest island of a small, circular archipelago which bears the same name and is the remnant of a volcanic caldera...

and to Egypt

Egypt

Egypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

. Both of these trips would have taken more than a day’s sail for the Minoans and would have left them traveling by night across open water. Here the sailors would use the locations of particular stars, especially that of the constellation Ursa Major

Ursa Major

Ursa Major , also known as the Great Bear, is a constellation visible throughout the year in most of the northern hemisphere. It can best be seen in April...

, to orient the ship in the correct direction.

Written records of navigation using stars, or celestial navigation

Celestial navigation

Celestial navigation, also known as astronavigation, is a position fixing technique that has evolved over several thousand years to help sailors cross oceans without having to rely on estimated calculations, or dead reckoning, to know their position...

, go back to Homer

Homer

In the Western classical tradition Homer , is the author of the Iliad and the Odyssey, and is revered as the greatest ancient Greek epic poet. These epics lie at the beginning of the Western canon of literature, and have had an enormous influence on the history of literature.When he lived is...

’s Odyssey

Odyssey

The Odyssey is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is, in part, a sequel to the Iliad, the other work ascribed to Homer. The poem is fundamental to the modern Western canon, and is the second—the Iliad being the first—extant work of Western literature...

where Calypso

Calypso (mythology)

Calypso was a nymph in Greek mythology, who lived on the island of Ogygia, where she detained Odysseus for a number of years. She is generally said to be the daughter of the Titan Atlas....

tells Odysseus

Odysseus

Odysseus or Ulysses was a legendary Greek king of Ithaca and the hero of Homer's epic poem the Odyssey. Odysseus also plays a key role in Homer's Iliad and other works in the Epic Cycle....

to keep the Bear on his left hand side as he sailed away from her island. The Greek

Greeks

The Greeks, also known as the Hellenes , are a nation and ethnic group native to Greece, Cyprus and neighboring regions. They also form a significant diaspora, with Greek communities established around the world....

poet Aratus

Aratus

Aratus was a Greek didactic poet. He is best known today for being quoted in the New Testament. His major extant work is his hexameter poem Phaenomena , the first half of which is a verse setting of a lost work of the same name by Eudoxus of Cnidus. It describes the constellations and other...

wrote in his Phainomena in the third century BCE detailed positions of the constellations as written by Eudoxos

Eudoxus of Cnidus

Eudoxus of Cnidus was a Greek astronomer, mathematician, scholar and student of Plato. Since all his own works are lost, our knowledge of him is obtained from secondary sources, such as Aratus's poem on astronomy...

. The positions described do not match the locations of the stars during Aratus’ or Eudoxos’ time for the Greek mainland, but some argue that they match the sky from Crete

Crete

Crete is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, and one of the thirteen administrative regions of Greece. It forms a significant part of the economy and cultural heritage of Greece while retaining its own local cultural traits...

during the Bronze Age

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a period characterized by the use of copper and its alloy bronze as the chief hard materials in the manufacture of some implements and weapons. Chronologically, it stands between the Stone Age and Iron Age...

. This change in the position of the stars is due to the wobble of the Earth

Polar motion

Polar motion of the earth is the movement of Earth's rotational axis across its surface. This is measured with respect to a reference frame in which the solid Earth is fixed...

on its axis which affects primarily the pole stars. Around 1000 BCE the constellation Draco

Draco (constellation)

Draco is a constellation in the far northern sky. Its name is Latin for dragon. Draco is circumpolar for many observers in the northern hemisphere...

would have been closer to the North Pole

North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is, subject to the caveats explained below, defined as the point in the northern hemisphere where the Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface...

than Polaris

Polaris

Polaris |Alpha]] Ursae Minoris, commonly North Star or Pole Star, also Lodestar) is the brightest star in the constellation Ursa Minor. It is very close to the north celestial pole, making it the current northern pole star....

. The pole stars were used to navigate because they did not disappear below the horizon and could be seen consistently throughout the night.

By the third century BCE the Greeks had begun to use the Little Bear, Ursa Minor

Ursa Minor

Ursa Minor , also known as the Little Bear, is a constellation in the northern sky. Like the Great Bear, the tail of the Little Bear may also be seen as the handle of a ladle, whence the name Little Dipper...

, to navigate. In the mid first century CE Lucan

Marcus Annaeus Lucanus

Marcus Annaeus Lucanus , better known in English as Lucan, was a Roman poet, born in Corduba , in the Hispania Baetica. Despite his short life, he is regarded as one of the outstanding figures of the Imperial Latin period...

writes of Pompey

Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, also known as Pompey or Pompey the Great , was a military and political leader of the late Roman Republic...

who questions a sailor about the use of stars in navigation. The sailor replies with his description of the use of circumpolar stars to navigate by. To navigate along a degree of latitude a sailor would have needed to find a circumpolar star above that degree in the sky. For example, Apollonius

Apollonius of Perga

Apollonius of Perga [Pergaeus] was a Greek geometer and astronomer noted for his writings on conic sections. His innovative methodology and terminology, especially in the field of conics, influenced many later scholars including Ptolemy, Francesco Maurolico, Isaac Newton, and René Descartes...

would have used β Draconis to navigate as he traveled west from the mouth of the Alpheus River to Syracuse.

The voyage of the Greek

Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece is a civilization belonging to a period of Greek history that lasted from the Archaic period of the 8th to 6th centuries BC to the end of antiquity. Immediately following this period was the beginning of the Early Middle Ages and the Byzantine era. Included in Ancient Greece is the...

navigator Pytheas of Massalia

Pytheas

Pytheas of Massalia or Massilia , was a Greek geographer and explorer from the Greek colony, Massalia . He made a voyage of exploration to northwestern Europe at about 325 BC. He travelled around and visited a considerable part of Great Britain...

is a particularly notable example of a very long, early voyage. A competent astronomer and geographer, Pytheas ventured from Greece through the strait of Gibraltar to Western Europe and the British Isles. Pytheas is the first known person to describe the Midnight Sun

Midnight sun

The midnight sun is a natural phenomenon occurring in summer months at latitudes north and nearby to the south of the Arctic Circle, and south and nearby to the north of the Antarctic Circle where the sun remains visible at the local midnight. Given fair weather, the sun is visible for a continuous...

, polar ice, Germanic tribes

Germanic peoples

The Germanic peoples are an Indo-European ethno-linguistic group of Northern European origin, identified by their use of the Indo-European Germanic languages which diversified out of Proto-Germanic during the Pre-Roman Iron Age.Originating about 1800 BCE from the Corded Ware Culture on the North...

and possibly Stonehenge. Pytheas also introduced the idea of distant "Thule

Thule

Thule Greek: Θούλη, Thoulē), also spelled Thula, Thila, or Thyïlea, is, in classical European literature and maps, a region in the far north. Though often considered to be an island in antiquity, modern interpretations of what was meant by Thule often identify it as Norway. Other interpretations...

" to the geographic imagination and his account is the earliest to state that the moon is the cause of the tides.

Nearchos’s celebrated voyage from India

India

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

to Susa

Susa

Susa was an ancient city of the Elamite, Persian and Parthian empires of Iran. It is located in the lower Zagros Mountains about east of the Tigris River, between the Karkheh and Dez Rivers....

after Alexander's expedition in India is preserved in Arrian

Arrian

Lucius Flavius Arrianus 'Xenophon , known in English as Arrian , and Arrian of Nicomedia, was a Roman historian, public servant, a military commander and a philosopher of the 2nd-century Roman period...

's account, the Indica

Indica (Arrian)

Indica is the name of an ancient book about India written by Arrian, one of the main ancient historians of Alexander the Great. The book mainly tells the story of Alexander's officer Nearchus’ voyage from India to the Persian Gulf after Alexander the Great’s conquest of the Indus Valley...

. Greek navigator Eudoxus of Cyzicus

Eudoxus of Cyzicus

Eudoxus of Cyzicus was a Greek navigator who explored the Arabian Sea for Ptolemy VIII, king of the Hellenistic Ptolemaic dynasty in Egypt.-Voyages to India:...

explored the Arabian Sea for Ptolemy VIII

Ptolemy VIII Physcon

Ptolemy VIII Euergetes II , nicknamed , Phúskōn, Physcon for his obesity, was a king of the Ptolemaic dynasty in Egypt. His complicated career started in 170 BC, when Antiochus IV Epiphanes invaded Egypt, captured his brother Ptolemy VI Philometor and let him continue as a puppet monarch...

, king of the Hellenistic

Hellenistic civilization

Hellenistic civilization represents the zenith of Greek influence in the ancient world from 323 BCE to about 146 BCE...

Ptolemaic dynasty

Ptolemaic dynasty

The Ptolemaic dynasty, was a Macedonian Greek royal family which ruled the Ptolemaic Empire in Egypt during the Hellenistic period. Their rule lasted for 275 years, from 305 BC to 30 BC...

in Egypt

Egypt

Egypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

. According to Poseidonius, later reported in Strabo

Strabo

Strabo, also written Strabon was a Greek historian, geographer and philosopher.-Life:Strabo was born to an affluent family from Amaseia in Pontus , a city which he said was situated the approximate equivalent of 75 km from the Black Sea...

's Geography

Geographica (Strabo)

The Geographica , or Geography, is a 17-volume encyclopedia of geographical knowledge written in Greek by Strabo, an educated citizen of the Roman empire of Greek descent. Work can have begun on it no earlier than 20 BC...

, the monsoon wind system

Monsoon

Monsoon is traditionally defined as a seasonal reversing wind accompanied by corresponding changes in precipitation, but is now used to describe seasonal changes in atmospheric circulation and precipitation associated with the asymmetric heating of land and sea...

of the Indian Ocean was first sailed by Eudoxus of Cyzicus in 118 or 116 BC.

Nautical chart

Nautical chart

A nautical chart is a graphic representation of a maritime area and adjacent coastal regions. Depending on the scale of the chart, it may show depths of water and heights of land , natural features of the seabed, details of the coastline, navigational hazards, locations of natural and man-made aids...

s and textual descriptions known as sailing directions have been in use in one form or another since the sixth century BC. Nautical charts using stereographic and orthographic projections date back to the second century BC.

Phoenicia and Carthage

The PhoeniciaPhoenicia

Phoenicia , was an ancient civilization in Canaan which covered most of the western, coastal part of the Fertile Crescent. Several major Phoenician cities were built on the coastline of the Mediterranean. It was an enterprising maritime trading culture that spread across the Mediterranean from 1550...

ns and their successors, the Carthaginians

Carthage

Carthage , implying it was a 'new Tyre') is a major urban centre that has existed for nearly 3,000 years on the Gulf of Tunis, developing from a Phoenician colony of the 1st millennium BC...

, were particularly adept sailors and learned to voyage further and further away from the coast in order to reach destinations faster. One tool that helped them was the sounding weight

Sounding line

A sounding line or lead line is a length of thin rope with a plummet, generally of lead, at its end. Regardless of the actual composition of the plummet, it is still called a "lead."...

. This tool was bell shaped, made from stone or lead, with tallow

Tallow

Tallow is a rendered form of beef or mutton fat, processed from suet. It is solid at room temperature. Unlike suet, tallow can be stored for extended periods without the need for refrigeration to prevent decomposition, provided it is kept in an airtight container to prevent oxidation.In industry,...

inside attached to a very long rope. When out to sea, sailors could lower the sounding weight in order to determine how deep the waters were, and therefore estimate how far they were from land. Also, the tallow picked up sediments from the bottom which expert sailors could examine to determine exactly where they were. The Carthaginian Hanno the Navigator

Hanno the Navigator

Hanno the Navigator was a Carthaginian explorer c. 500 BC, best known for his naval exploration of the African coast...

is known to have sailed through the Strait of Gibraltar

Strait of Gibraltar

The Strait of Gibraltar is a narrow strait that connects the Atlantic Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea and separates Spain in Europe from Morocco in Africa. The name comes from Gibraltar, which in turn originates from the Arabic Jebel Tariq , albeit the Arab name for the Strait is Bab el-Zakat or...

c. 500 BC and explored the Atlantic coast of Africa. There is general consensus that the expedition

Exploration

Exploration is the act of searching or traveling around a terrain for the purpose of discovery of resources or information. Exploration occurs in all non-sessile animal species, including humans...

reached at least as far as Senegal

Senegal

Senegal , officially the Republic of Senegal , is a country in western Africa. It owes its name to the Sénégal River that borders it to the east and north...

. There is a lack of agreement whether the furthest limit of Hanno's explorations was Mount Cameroon

Mount Cameroon

Mount Cameroon is an active volcano in Cameroon near the Gulf of Guinea. Mount Cameroon is also known as Cameroon Mountain or Fako or by its native name Mongo ma Ndemi ....

, or Guinea's 890-metre (2910-foot) Mount Kakulima.

Asia

In the South China SeaSouth China Sea

The South China Sea is a marginal sea that is part of the Pacific Ocean, encompassing an area from the Singapore and Malacca Straits to the Strait of Taiwan of around...

and Indian Ocean, a navigator could take advantage of the fairly constant monsoon winds to judge direction. This made long one-way voyages possible twice a year.

The earliest known reference to an organization devoted to ships in ancient India is to the Mauryan Empire from the 4th century BCE. The Arthashastra

Arthashastra

The Arthashastra is an ancient Indian treatise on statecraft, economic policy and military strategy which identifies its author by the names Kautilya and , who are traditionally identified with The Arthashastra (IAST: Arthaśāstra) is an ancient Indian treatise on statecraft, economic policy and...

of Emperor Chandragupta Maurya

Chandragupta Maurya

Chandragupta Maurya , was the founder of the Maurya Empire. Chandragupta succeeded in conquering most of the Indian subcontinent. Chandragupta is considered the first unifier of India and its first genuine emperor...

's prime minister, Kautilya, devotes a full chapter on the state department of waterways under a navadhyaksha (Sanskrit for "superintendent of ships"). The term, nava dvipantaragamanam (Sanskrit for sailing to other lands by ships) appears in this book in addition to appearing in the Buddhist text Baudhayana Dharmasastra.

Medieval Age of Navigation

The Arab EmpireCaliphate

The term caliphate, "dominion of a caliph " , refers to the first system of government established in Islam and represented the political unity of the Muslim Ummah...

significantly contributed to navigation

Navigation

Navigation is the process of monitoring and controlling the movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another. It is also the term of art used for the specialized knowledge used by navigators to perform navigation tasks...

, and had trade network

Trade route

A trade route is a logistical network identified as a series of pathways and stoppages used for the commercial transport of cargo. Allowing goods to reach distant markets, a single trade route contains long distance arteries which may further be connected to several smaller networks of commercial...

s extending from the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea

Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean surrounded by the Mediterranean region and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Anatolia and Europe, on the south by North Africa, and on the east by the Levant...

in the west to the Indian Ocean and China Sea in the east, Apart from the Nile

Nile

The Nile is a major north-flowing river in North Africa, generally regarded as the longest river in the world. It is long. It runs through the ten countries of Sudan, South Sudan, Burundi, Rwanda, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Tanzania, Kenya, Ethiopia, Uganda and Egypt.The Nile has two major...

, Tigris

Tigris

The Tigris River is the eastern member of the two great rivers that define Mesopotamia, the other being the Euphrates. The river flows south from the mountains of southeastern Turkey through Iraq.-Geography:...

and Euphrates

Euphrates

The Euphrates is the longest and one of the most historically important rivers of Western Asia. Together with the Tigris, it is one of the two defining rivers of Mesopotamia...

, navigable rivers in the Islamic regions were uncommon, so transport by sea was very important. Islamic geography

Islamic geography

Geography and cartography in medieval Islam refers to the advancement of geography, cartography and the earth sciences in the medieval Islamic civilization....

and navigational sciences made use of a magnetic compass

Compass

A compass is a navigational instrument that shows directions in a frame of reference that is stationary relative to the surface of the earth. The frame of reference defines the four cardinal directions – north, south, east, and west. Intermediate directions are also defined...

and a rudimentary instrument known as a kamal, used for celestial navigation

Celestial navigation

Celestial navigation, also known as astronavigation, is a position fixing technique that has evolved over several thousand years to help sailors cross oceans without having to rely on estimated calculations, or dead reckoning, to know their position...

and for measuring the altitude

Altitude

Altitude or height is defined based on the context in which it is used . As a general definition, altitude is a distance measurement, usually in the vertical or "up" direction, between a reference datum and a point or object. The reference datum also often varies according to the context...

s and latitude

Latitude

In geography, the latitude of a location on the Earth is the angular distance of that location south or north of the Equator. The latitude is an angle, and is usually measured in degrees . The equator has a latitude of 0°, the North pole has a latitude of 90° north , and the South pole has a...

s of the star

Star

A star is a massive, luminous sphere of plasma held together by gravity. At the end of its lifetime, a star can also contain a proportion of degenerate matter. The nearest star to Earth is the Sun, which is the source of most of the energy on Earth...

s. The kamal itself was rudimentary and simple to construct. It was simply a rectangular piece of either bone or wood which had a string with 9 consecutive knots attached to it. Another instrument available, developed by the Arabs as well, was the quadrant. Also a celestial navigation device, it was originally developed for astronomy and later transitioned to navigation. When combined with detailed maps of the period, sailors were able to sail across oceans rather than skirt along the coast. According to the political scientist Hobson, the origins of the caravel

Caravel

A caravel is a small, highly maneuverable sailing ship developed in the 15th century by the Portuguese to explore along the West African coast and into the Atlantic Ocean. The lateen sails gave her speed and the capacity for sailing to windward...

ship, used for long-distance travel by the Spanish and Portuguese since the 15th century, date back to the qarib used by Andalusian

Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus was the Arabic name given to a nation and territorial region also commonly referred to as Moorish Iberia. The name describes parts of the Iberian Peninsula and Septimania governed by Muslims , at various times in the period between 711 and 1492, although the territorial boundaries...

explorers by the 13th century.

History of India

The history of India begins with evidence of human activity of Homo sapiens as long as 75,000 years ago, or with earlier hominids including Homo erectus from about 500,000 years ago. The Indus Valley Civilization, which spread and flourished in the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent from...

and neighboring lands were the usual form of trade for many centuries, and are responsible for the widespread influence of Indian culture to the societies of Southeast Asia. Powerful navies included those of the Maurya, Satavahana

Satavahana

The Sātavāhana Empire or Andhra Empire, was a royal Indian dynasty based from Dharanikota and Amaravati in Andhra Pradesh as well as Junnar and Prathisthan in Maharashtra. The territory of the empire covered much of India from 230 BCE onward...

, Chola, Vijayanagara

Vijayanagara

Vijayanagara is in Bellary District, northern Karnataka. It is the name of the now-ruined capital city "which was regarded as the second Rome" that surrounds modern-day Hampi, of the historic Vijayanagara empire which extended over the southern part of India....

, Kalinga

Kalinga

Kalinga is a landlocked province of the Philippines in the Cordillera Administrative Region in Luzon. Its capital is Tabuk and borders Mountain Province to the south, Abra to the west, Isabela to the east, Cagayan to the northeast, and Apayao to the north...

, Maratha

Maratha

The Maratha are an Indian caste, predominantly in the state of Maharashtra. The term Marāthā has three related usages: within the Marathi speaking region it describes the dominant Maratha caste; outside Maharashtra it can refer to the entire regional population of Marathi-speaking people;...

and Mughal Empire

Mughal Empire

The Mughal Empire , or Mogul Empire in traditional English usage, was an imperial power from the Indian Subcontinent. The Mughal emperors were descendants of the Timurids...

.

In China between 1040 and 1117, the magnetic compass was being developed and applied to navigation. This let masters continue sailing a course when the weather limited visibility of the sky. The true mariner's compass using a pivoting needle in a dry box was invented in Europe no later than 1300.

Nautical charts called portolan charts began to appear in Italy

Italy

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

at the end of the 13th century. However, their use did not seem to spread quickly: there are no reports of the use of a nautical chart on an English vessel until 1489.

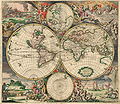

Age of Exploration

Portuguese Empire

The Portuguese Empire , also known as the Portuguese Overseas Empire or the Portuguese Colonial Empire , was the first global empire in history...

in the early 15th century marked an epoch of distinct progress in practical navigation. These trade expeditions sent out by Henry the Navigator led first to the discovery of the Porto Santo (near Madeira) in 1418, rediscovery of the Azores

Azores

The Archipelago of the Azores is composed of nine volcanic islands situated in the middle of the North Atlantic Ocean, and is located about west from Lisbon and about east from the east coast of North America. The islands, and their economic exclusion zone, form the Autonomous Region of the...

in 1427, the discovery of the Cape Verde

Cape Verde

The Republic of Cape Verde is an island country, spanning an archipelago of 10 islands located in the central Atlantic Ocean, 570 kilometres off the coast of Western Africa...

Islands in 1447 and Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone , officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country in West Africa. It is bordered by Guinea to the north and east, Liberia to the southeast, and the Atlantic Ocean to the west and southwest. Sierra Leone covers a total area of and has an estimated population between 5.4 and 6.4...

in 1462. Henry worked to systemize the practice of navigation. In order to develop more accurate tables on the sun's declination

Declination

In astronomy, declination is one of the two coordinates of the equatorial coordinate system, the other being either right ascension or hour angle. Declination in astronomy is comparable to geographic latitude, but projected onto the celestial sphere. Declination is measured in degrees north and...

, he established an observatory at Sagres. Combined with the empirical observations gathered in oceanic seafaring, mapping winds and currents, Portuguese explorers took the lead in the long distance oceanic navigation.

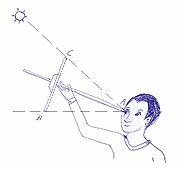

Henry's successor, John II

John II of Portugal

John II , the Perfect Prince , was the thirteenth king of Portugal and the Algarves...

continued this research, forming a committee on navigation. This group computed tables of the sun's declination and improved the mariner's astrolabe

Mariner's astrolabe

The mariner's astrolabe, also called sea astrolabe, was an inclinometer used to determine the latitude of a ship at sea by measuring the sun's noon altitude or the meridian altitude of a star of known declination. Not an astrolabe proper, the mariner's astrolabe was rather a graduated circle with...

, believing it a good replacement for the cross-staff. These resources improved the ability of a navigator at sea to judge his latitude

Latitude

In geography, the latitude of a location on the Earth is the angular distance of that location south or north of the Equator. The latitude is an angle, and is usually measured in degrees . The equator has a latitude of 0°, the North pole has a latitude of 90° north , and the South pole has a...

.

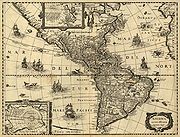

In the 15th and 16th centuries, Spain

Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire comprised territories and colonies administered directly by Spain in Europe, in America, Africa, Asia and Oceania. It originated during the Age of Exploration and was therefore one of the first global empires. At the time of Habsburgs, Spain reached the peak of its world power....

was in the vanguard of European global exploration and colonial expansion. Spain opened trade routes across the oceans, specially the transatlantic expedition of Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus was an explorer, colonizer, and navigator, born in the Republic of Genoa, in northwestern Italy. Under the auspices of the Catholic Monarchs of Spain, he completed four voyages across the Atlantic Ocean that led to general European awareness of the American continents in the...

in 1492. The Crown of Spain also financed the first expedition of world circumnavigation

Circumnavigation

Circumnavigation – literally, "navigation of a circumference" – refers to travelling all the way around an island, a continent, or the entire planet Earth.- Global circumnavigation :...

in 1521. The enterprise was led by Portuguese navigator Ferdinand Magellan

Ferdinand Magellan

Ferdinand Magellan was a Portuguese explorer. He was born in Sabrosa, in northern Portugal, and served King Charles I of Spain in search of a westward route to the "Spice Islands" ....

and completed by Spaniard Juan Sebastian Elcano

Juan Sebastián Elcano

Juan Sebastián Elcano was a Basque Spanish explorer who completed the first circumnavigation of the world. As Ferdinand Magellan's second in command, Elcano took over after Magellan's death in the Philippines.-Early life:Elcano was born to Domingo Sebastián Elcano I and Catalina del Puerto...

. The trips of exploration led to trade flourishing across the Atlantic Ocean between Spain and America

Americas

The Americas, or America , are lands in the Western hemisphere, also known as the New World. In English, the plural form the Americas is often used to refer to the landmasses of North America and South America with their associated islands and regions, while the singular form America is primarily...

and across the Pacific Ocean between Asia-Pacific and Mexico

Mexico

The United Mexican States , commonly known as Mexico , is a federal constitutional republic in North America. It is bordered on the north by the United States; on the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; on the southeast by Guatemala, Belize, and the Caribbean Sea; and on the east by the Gulf of...

via the Philippines

Philippines

The Philippines , officially known as the Republic of the Philippines , is a country in Southeast Asia in the western Pacific Ocean. To its north across the Luzon Strait lies Taiwan. West across the South China Sea sits Vietnam...

.

The compass, a cross-staff or astrolabe, a method to correct for the altitude of Polaris

Polaris

Polaris |Alpha]] Ursae Minoris, commonly North Star or Pole Star, also Lodestar) is the brightest star in the constellation Ursa Minor. It is very close to the north celestial pole, making it the current northern pole star....

and rudimentary nautical charts were all the tools available to a navigator at the time of Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus was an explorer, colonizer, and navigator, born in the Republic of Genoa, in northwestern Italy. Under the auspices of the Catholic Monarchs of Spain, he completed four voyages across the Atlantic Ocean that led to general European awareness of the American continents in the...

. In his notes on Ptolemy's geography, Johannes Werner

Johannes Werner

Johann Werner was a German parish priest in Nuremberg and a mathematician...

of Nurenberg wrote in 1514 that the cross-staff was a very ancient instrument, but was only beginning to be used on ships.

Rabbi Abraham Zacuto perfected the astrolabe, which only then became an instrument of precision, and he was the author of the highly accurate Almanach Perpetuum that were used by ship captains to determine the position of their Portuguese caravels in high seas, through calculations on data acquired with an astrolabe. His contributions were undoubtedly valuable in saving the lives of Portuguese seamen, and allowing them to reach Brazil and India.

While in Spain he wrote an exceptional treatise on astronomy/astrology in Hebrew, with the title Ha-jibbur Ha-gadol. He published in the printing press of Leiria in 1496, property of Abraão de Ortas the book Biur Luhoth, or in Latin Almanach Perpetuum, which was soon translated into Latin and Spanish. In this book were the astronomical tables (ephemerides) for the years 1497 to 1500, which were instrumental, together with the new astrolabe made of metal and not wood as before, to Vasco da Gama

Vasco da Gama

Vasco da Gama, 1st Count of Vidigueira was a Portuguese explorer, one of the most successful in the Age of Discovery and the commander of the first ships to sail directly from Europe to India...

and Pedro Álvares Cabral

Pedro Álvares Cabral

Pedro Álvares Cabral was a Portuguese noble, military commander, navigator and explorer regarded as the discoverer of Brazil. Cabral conducted the first substantial exploration of the northeast coast of South America and claimed it for Portugal. While details of Cabral's early life are sketchy, it...

in their voyages to India and Brazil respectively.

Prior to 1577, no method of judging the ship's speed was mentioned that was more advanced than observing the size of the vessel's bow wave

Bow wave

A bow wave is the wave that forms at the bow of a ship when it moves through the water. As the bow wave spreads out, it defines the outer limits of a ship's wake. A large bow wave slows the ship down, poses a risk to smaller boats, and in a harbor can cause damage to shore facilities and moored ships...

or the passage of sea foam or various floating objects. In 1577, a more advanced technique was mentioned: the chip log

Chip log

A chip log, also called common log, ship log or just log, is a navigation tool used by mariners to estimate the speed of a vessel through water.-Construction:...

. In 1578, a patent was registered for a device that would judge the ship's speed by counting the revolutions of a wheel mounted below the ship's waterline.

Accurate time-keeping is necessary for the determination of longitude. As early as 1530, precursors to modern techniques were being explored. However, the most accurate clocks available to these early navigators were water clocks and sand clocks, such as hourglass

Hourglass

An hourglass measures the passage of a few minutes or an hour of time. It has two connected vertical glass bulbs allowing a regulated trickle of material from the top to the bottom. Once the top bulb is empty, it can be inverted to begin timing again. The name hourglass comes from historically...

. Hourglasses were still in use by the Royal Navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

of Britain until 1839 for the timing of watches

Watchstanding

Watchstanding, or watchkeeping, in nautical terms concerns the division of qualified personnel to operate a ship continuously around the clock. On a typical sea going vessel, be it naval or merchant, personnel keep watch on the bridge and over the running machinery...

.

Continuous accumulation of navigational data, along with increased exploration and trade, led to increased production of volumes through the Middle Ages. "Routiers" were produced in France about 1500; the English referred to them as "rutters." In 1584 Lucas Waghenaer published the Spieghel der Zeevaerdt (The Mariner’s Mirror), which became the model for such publications for several generations of navigators. They were known as "Waggoners" by most sailors.

In 1537, the Portuguese cosmographer Pedro Nunes

Pedro Nunes

Pedro Nunes , was a Portuguese mathematician, cosmographer, and professor, from a New Christian family. Nunes, considered to be one of the greatest mathematicians of his time , is best known for his contributions in the technical field of navigation, which was crucial to the Portuguese period of...

published his Tratado da Sphera. In this book he included two original treatises about questions of navigation. For the first time the subject was approached using mathematical tools. This publication gave rise to a new scientific discipline: "theoretical or scientific navigation".

In 1545, Pedro de Medina published the influential Arte de navegar. The book was translated into French, Italian, Dutch and English.

In the late 16th century, Gerardus Mercator

Gerardus Mercator

thumb|right|200px|Gerardus MercatorGerardus Mercator was a cartographer, born in Rupelmonde in the Hapsburg County of Flanders, part of the Holy Roman Empire. He is remembered for the Mercator projection world map, which is named after him...

made vast improvements to nautical charts.

In 1594, John Davis

John Davis (English explorer)

John Davis , was one of the chief English navigators and explorers under Elizabeth I, especially in Polar regions and in the Far East.-Early life:...

published an 80-page pamphlet called The Seaman's Secrets which, among other things describes great circle sailing

Great circle

A great circle, also known as a Riemannian circle, of a sphere is the intersection of the sphere and a plane which passes through the center point of the sphere, as opposed to a general circle of a sphere where the plane is not required to pass through the center...

. It's said that the explorer Sebastian Cabot

Sebastian Cabot (explorer)

Sebastian Cabot was an explorer, born in the Venetian Republic.-Origins:...

had used great circle methods in a crossing of the North Atlantic in 1495. Davis also gave the world a version of the backstaff

Backstaff

The backstaff or back-quadrant is a navigational instrument that was used to measure the altitude of a celestial body, in particular the sun or moon...

, the Davis quadrant, which became one of the dominant instruments from the 17th century until the adoption of the sextant

Sextant

A sextant is an instrument used to measure the angle between any two visible objects. Its primary use is to determine the angle between a celestial object and the horizon which is known as the altitude. Making this measurement is known as sighting the object, shooting the object, or taking a sight...

in the 19th century.

In 1599, Edward Wright

Edward Wright (mathematician)

Edward Wright was an English mathematician and cartographer noted for his book Certaine Errors in Navigation , which for the first time explained the mathematical basis of the Mercator projection, and set out a reference table giving the linear scale multiplication factor as a function of...

published Certaine Errors in Navigation, which for the first time explained the mathematical basis of the Mercator projection

Mercator projection

The Mercator projection is a cylindrical map projection presented by the Belgian geographer and cartographer Gerardus Mercator, in 1569. It became the standard map projection for nautical purposes because of its ability to represent lines of constant course, known as rhumb lines or loxodromes, as...

, with calculated mathematical tables which made it possible to use in practice. The book made clear why only with this projection would a constant bearing correspond to a straight line on a chart. It also analysed other sources of error, including the risk of parallax errors with some instruments; and faulty estimates of latitude and longitude on contemporary charts.

In 1631, Pierre Vernier

Pierre Vernier

Pierre Vernier was a French mathematician and instrument inventor. He was inventor and eponym of the vernier scale used in measuring devices....

described his newly invented quadrant

Quadrant (instrument)

A quadrant is an instrument that is used to measure angles up to 90°. It was originally proposed by Ptolemy as a better kind of astrolabe. Several different variations of the instrument were later produced by medieval Muslim astronomers.-Types of quadrants:...

that was accurate to one minute of arc. In theory, this level of accuracy could give a line of position within a nautical mile of the navigator's actual position.

In 1635, Henry Gellibrand

Henry Gellibrand

Henry Gellibrand was an English mathematician. He is known for his work on the Earth's magnetic field. He discovered that magnetic declination – the angle of dip of a compass needle – is not constant but changes over time...

published an account of yearly change in magnetic variation.

In 1637, using a specially built astronomical sextant

Sextant (astronomical)

Sextants for astronomical observations were used primarily for measuring the positions of stars. They are little used today, having been replaced over time by transit telescopes, astrometry techniques, and satellites such as Hipparcos....

with a 5-foot radius, Richard Norwood measured the length of a nautical mile with chains. His definition of 2,040 yards is fairly close to the modern International System of Units

International System of Units

The International System of Units is the modern form of the metric system and is generally a system of units of measurement devised around seven base units and the convenience of the number ten. The older metric system included several groups of units...

(SI) definition of 2,025.372 yards. Norwood is also credited with the discovery of magnetic dip

Magnetic dip

Magnetic dip or magnetic inclination is the angle made by a compass needle with the horizontal at any point on the Earth's surface. Positive values of inclination indicate that the field is pointing downward, into the Earth, at the point of measurement...

59 years earlier, in 1576.

Modern Times

Board of Longitude

The Board of Longitude was the popular name for the Commissioners for the Discovery of the Longitude at Sea. It was a British Government body formed in 1714 to administer a scheme of prizes intended to encourage innovators to solve the problem of finding longitude at sea.-Origins:Navigators and...

came into prominence. This group, which existed until 1828, offered grants and rewards for the solution of various navigational problems. Between 1737 and 1828, the commissioners disbursed some £101,000. The government of the United Kingdom also offered significant rewards for navigational accomplishments in this era, such as £20,000 for the discovery of the Northwest passage

Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage is a sea route through the Arctic Ocean, along the northern coast of North America via waterways amidst the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans...

and £5,000 for the navigator that could sail within a degree of latitude of the North pole

North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is, subject to the caveats explained below, defined as the point in the northern hemisphere where the Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface...

. A widespread manual in the 18th century was Navigatio Britannica by John Barrow

John Barrow (historian)

John Barrow was an English mathematician, naval historian and lexicographer.Nothing is known of Barrow's family. He was initially a teacher of mathematics and navigation aboard ships of the Royal Navy. He retired before 1750 and devoted himself to writing and compiling dictionaries and other works...

, published in 1750 by March & Page and still being advertised in 1787.

In 1731 the octant

Octant (instrument)

The octant, also called reflecting quadrant, is a measuring instrument used primarily in navigation. It is a type of reflecting instrument.-Etymology:...

was invented, eventually replacing earlier cross-staffs and Davis quadrants. This had the immediate effect of making latitude calculations much more accurate. Four years later, the first marine chronometer

Marine chronometer

A marine chronometer is a clock that is precise and accurate enough to be used as a portable time standard; it can therefore be used to determine longitude by means of celestial navigation...

was invented. The sextant

Sextant

A sextant is an instrument used to measure the angle between any two visible objects. Its primary use is to determine the angle between a celestial object and the horizon which is known as the altitude. Making this measurement is known as sighting the object, shooting the object, or taking a sight...

was derived from the octant in 1757 in order to provide for the lunar distance method. With the lunar distance method, mariners could determine their longitude accurately. Once chronometer production was established in the late 18th century, the use of the chronometer for accurate determination of longitude was a viable alternative. Chronometers replaced lunars in wide usage by the late 19th century.

In 1891, radios, in the form of wireless telegraphs, began to appear on ships at sea.

In 1899, the R.F. Matthews was the first ship to use wireless communication to request assistance at sea. The idea of using radio for determining direction was investigated by "Sir Oliver Lodge, of England; Andre Blondel, of France; De Forest

Lee De Forest

Lee De Forest was an American inventor with over 180 patents to his credit. De Forest invented the Audion, a vacuum tube that takes relatively weak electrical signals and amplifies them. De Forest is one of the fathers of the "electronic age", as the Audion helped to usher in the widespread use...

, Pickard; and Stone

John Stone Stone

John Stone Stone was an American mathematician, physicist and inventor. He labored as an early telephone engineer, was influential in developing wireless communication technology, and holds dozens of key patents in the field of "space telegraphy".-Early years:Stone was born in Dover, now Manakin...

, of the United States; and Bellini and Tosi, of Italy." The Stone Radio & Telegraph Company installed an early prototype radio direction finder

Radio direction finder

A radio direction finder is a device for finding the direction to a radio source. Due to low frequency propagation characteristic to travel very long distances and "over the horizon", it makes a particularly good navigation system for ships, small boats, and aircraft that might be some distance...

on the naval collier Lebanon in 1906.

By 1904, time signals were being sent to ships to allow navigators to routinely check their chronometers for error. The U.S. Navy Hydrographic Office was sending navigational warnings to ships at sea by 1907.

Later developments included the placing of lighthouse

Lighthouse

A lighthouse is a tower, building, or other type of structure designed to emit light from a system of lamps and lenses or, in older times, from a fire, and used as an aid to navigation for maritime pilots at sea or on inland waterways....

s and buoy

Buoy

A buoy is a floating device that can have many different purposes. It can be anchored or allowed to drift. The word, of Old French or Middle Dutch origin, is now most commonly in UK English, although some orthoepists have traditionally prescribed the pronunciation...

s close to shore to act as marine signposts identifying ambiguous features, highlighting hazards and pointing to safe channels for ships approaching some part of a coast after a long sea voyage. In 1912 Nils Gustaf Dalén was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics

Nobel Prize in Physics

The Nobel Prize in Physics is awarded once a year by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. It is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Alfred Nobel in 1895 and awarded since 1901; the others are the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, Nobel Prize in Literature, Nobel Peace Prize, and...

for his invention of automatic valves designed to be used in combination with gas accumulators in lighthouses

1921 saw the installation of the first radiobeacon.

The first prototype shipborne radar system was installed on the USS Leary in April 1937.

On November 18, 1940 Mr. Alfred L. Loomis made the initial suggestion for an electronic air navigation system which was later developed into LORAN

LORAN

LORAN is a terrestrial radio navigation system using low frequency radio transmitters in multiple deployment to determine the location and speed of the receiver....

(long range navigation system) by the Radiation Laboratory of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology is a private research university located in Cambridge, Massachusetts. MIT has five schools and one college, containing a total of 32 academic departments, with a strong emphasis on scientific and technological education and research.Founded in 1861 in...

, and on November 1, 1942 the first LORAN System was placed in operation with four stations between the Chesapeake Capes

Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay is the largest estuary in the United States. It lies off the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by Maryland and Virginia. The Chesapeake Bay's drainage basin covers in the District of Columbia and parts of six states: New York, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, and West...

and Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is one of Canada's three Maritime provinces and is the most populous province in Atlantic Canada. The name of the province is Latin for "New Scotland," but "Nova Scotia" is the recognized, English-language name of the province. The provincial capital is Halifax. Nova Scotia is the...

.

3.png)

Applied Physics Laboratory

The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory , located in Howard County, Maryland near Laurel and Columbia, is a not-for-profit, university-affiliated research center employing 4,500 people. APL is primarily a defense contractor. It serves as a technical resource for the Department of...

took a series of measurements of Sputniks doppler shift yielding the satellite's position and velocity. This team continued to monitor Sputnik and the next satellites into space, Sputnik II and Explorer I. In March 1958 the idea of working backwards, using known satellite orbits to determine an unknown position on the Earth's surface began to be explored. This led to the TRANSIT satellite navigation system. The first TRANSIT satellite was placed in polar orbit in 1960. The system, consisting of 7 satellites, was made operational in 1962. A navigator using readings from three satellites could expect accuracy of about 80 feet.

On July 14, 1974 the first prototype Navstar GPS satellite was put into orbit, but its clocks failed shortly after launch. The Navigational Technology Satellite 2, redesigned with caesium clocks, started to go into orbit on June 23, 1977. By 1985, the first 11-satellite GPS Block I constellation was in orbit.

Satellites of the similar Russian GLONASS

GLONASS

GLONASS , acronym for Globalnaya navigatsionnaya sputnikovaya sistema or Global Navigation Satellite System, is a radio-based satellite navigation system operated for the Russian government by the Russian Space Forces...

system began to be put into orbit in 1982, and the system is expected to have a complete 24-satellite constellation in place by 2010. The European Space Agency

European Space Agency

The European Space Agency , established in 1975, is an intergovernmental organisation dedicated to the exploration of space, currently with 18 member states...

expects to have its Galileo

Galileo positioning system

Galileo is a global navigation satellite system currently being built by the European Union and European Space Agency . The €20 billion project is named after the famous Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei...

with 30 satellites in place by 2011/12 as well.

Integrated bridge systems

Electronic integrated bridge concepts are driving future navigation system planning. Integrated systems take inputs from various ship sensors, electronically display positioning information, and provide control signals required to maintain a vessel on a preset course. The navigator becomes a system manager, choosing system presets, interpreting system output, and monitoring vessel response.See also

- Air navigationAir navigationThe basic principles of air navigation are identical to general navigation, which includes the process of planning, recording, and controlling the movement of a craft from one place to another....

- Austronesian navigationAustronesian navigationThe Austronesians were some of the early people that crossed vast open seas and settled farflung islands in search of new land to settle. The Austronesian expansion around 2500 BC and onwards is widely considered by some contemporary scholars to be one of the great movements of population in history....

- Celestial navigationCelestial navigationCelestial navigation, also known as astronavigation, is a position fixing technique that has evolved over several thousand years to help sailors cross oceans without having to rely on estimated calculations, or dead reckoning, to know their position...

- Galileo positioning systemGalileo positioning systemGalileo is a global navigation satellite system currently being built by the European Union and European Space Agency . The €20 billion project is named after the famous Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei...

- Geodetic systemGeodetic systemGeodetic systems or geodetic data are used in geodesy, navigation, surveying by cartographers and satellite navigation systems to translate positions indicated on their products to their real position on earth....

- Great-circle distanceGreat-circle distanceThe great-circle distance or orthodromic distance is the shortest distance between any two points on the surface of a sphere measured along a path on the surface of the sphere . Because spherical geometry is rather different from ordinary Euclidean geometry, the equations for distance take on a...

explains how to find that quantity if one knows the two latitudes and longitude - History of longitudeHistory of longitudeThe history of longitude is a record of the effort, by navigators and scientists over several centuries, to discover a means of determining longitude....

- Ma JunMa JunMa Jun , style name Deheng , was a Chinese mechanical engineer and government official during the Three Kingdoms era of China...

- Shen KuoShen KuoShen Kuo or Shen Gua , style name Cunzhong and pseudonym Mengqi Weng , was a polymathic Chinese scientist and statesman of the Song Dynasty...

- List of explorers

- Maritime history of the United States

- Marshall Islands stick chartMarshall Islands stick chartStick charts were made and used by the Marshallese to navigate the Pacific Ocean by canoe off the coast of the Marshall Islands. The charts represented major ocean swell patterns and the ways the islands disrupted those patterns, typically determined by sensing disruptions in ocean swells by...

- NavigationNavigationNavigation is the process of monitoring and controlling the movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another. It is also the term of art used for the specialized knowledge used by navigators to perform navigation tasks...

- Polynesian navigationPolynesian navigationPolynesian navigation is a system of navigation used by Polynesians to make long voyages across thousands of miles of open ocean. Navigators travel to small inhabited islands using only their own senses and knowledge passed by oral tradition from navigator to apprentice, often in the form of song...

- South Pointing ChariotSouth Pointing ChariotThe south-pointing chariot was an ancient Chinese two-wheeled vehicle that carried a movable pointer to indicate the south, no matter how the chariot turned. Usually, the pointer took the form of a doll or figure with an outstretched arm...

- Franz Xaver, Baron Von Zach, a scientific editor and astronomer, first located many places geographically