.gif)

Edward Wright (mathematician)

Encyclopedia

Edward Wright was an English mathematician

and cartographer noted for his book Certaine Errors in Navigation (1599; 2nd ed., 1610), which for the first time explained the mathematical basis of the Mercator projection

, and set out a reference table giving the linear scale multiplication factor as a function of latitude

, calculated for each minute of arc

up to a latitude of 75°. This was in fact a table of values of the integral of the secant function

, and was the essential step needed to make practical both the making and the navigational use of Mercator charts.

Wright was born at Garveston

and educated at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge

, where he became a fellow from 1587 to 1596. In 1589 the College granted him leave after Elizabeth I

requested that he carry out navigation

al studies with a raiding expedition organised by the Earl of Cumberland

to the Azores

to capture Spanish galleon

s. The expedition's route was the subject of the first map to be prepared according to Wright's projection, which was published in Certaine Errors in 1599. The same year, Wright created and published the first world map produced in England and the first to use the Mercator projection since Gerardus Mercator

's original 1569 map.

Not long after 1600 Wright was appointed as surveyor

to the New River

project, which successfully directed the course of a new man-made channel to bring clean water from Ware, Hertfordshire

, to Islington

, London. Around this time, Wright also lectured mathematics to merchant seamen, and from 1608 or 1609 was mathematics tutor to the son of James I

, the heir apparent

Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales

, until the latter's very early death at the age of 18 in 1612. A skilled designer of mathematical instrument

s, Wright made models of an astrolabe

and a pantograph

, and a type of armillary sphere

for Prince Henry. In the 1610 edition of Certaine Errors he described inventions such as the "sea-ring" that enabled mariners to determine the magnetic variation

of the compass

, the sun's altitude and the time of day in any place if the latitude was known; and a device for finding latitude when one was not on the meridian

using the height of the pole star.

Apart from a number of other books and pamphlets, Wright translated John Napier

's pioneering 1614 work which introduced the idea of logarithm

s from Latin

into English. This was published after Wright's death as A Description of the Admirable Table of Logarithmes (1616). Wright's work influenced, among other persons, Dutch astronomer and mathematician Willebrord Snellius

; Adriaan Metius

, the geometer and astronomer from Holland; and the English mathematician Richard Norwood

, who calculated the length of a degree

on a great circle

of the earth using a method proposed by Wright.

in Norfolk

, East Anglia

, and was baptised

there on 8 October 1561. It is possible that he followed in the footsteps of his elder brother Thomas (died 1579) and went to school in Hardingham

. The family was of modest means, and he matriculated

at Gonville and Caius College

, University of Cambridge

, on 8 December 1576 as a sizar

. Sizars were students of limited means who were charged lower fees and obtained free food and/or lodging and other assistance during their period of study, often in exchange for performing work at their colleges.

Wright was conferred a Bachelor of Arts

(B.A.) in 1580–1581. He remained a scholar at Caius, receiving his Master of Arts (M.A.) there in 1584, and holding a fellowship between 1587 and 1596. At Cambridge, he was a close friend of Robert Devereux

, later the Second Earl of Essex

, and met him to discuss his studies even in the weeks before Devereux's rebellion against Elizabeth I

in 1600–1601. In addition, he came to know the mathematician Henry Briggs

; and the soldier and astrologer

Christopher Heydon

, who was also Devereux's friend. Heydon later made astronomical observations with instruments Wright made for him.

In 1589, two years after being appointed to his fellowship, Wright was requested by Elizabeth I to carry out navigation

In 1589, two years after being appointed to his fellowship, Wright was requested by Elizabeth I to carry out navigation

al studies with a raiding expedition organised by the Earl of Cumberland

to the Azores

to capture Spanish galleon

s. The Queen effectively ordered Caius to grant him leave of absence for this purpose, although the College expressed this more diplomatically by granting him a sabbatical "by Royal mandate". Wright participated in the confiscation of "lawful" prizes

from the French, Portuguese and Spanish – Derek Ingram, a life fellow of Caius, has called him "the only Fellow of Caius ever to be granted sabbatical leave in order to engage in piracy". Wright sailed with Cumberland in the Victory from Plymouth

on 8 June 1589; they returned to Falmouth

on 27 December of the same year. An account of the expedition is appended to Wright's work Certaine Errors of Navigation (1599), and while it refers to Wright in the third person it is believed to have been written by him.

In Wright's account of the Azores expedition, he listed as one of the expedition's members a "Captaine Edwarde Carelesse, alias Wright, who in S. Frauncis Drakes West-Indian voiage was Captaine of the Hope". In another work, The Haven-finding Art (1599) (see below), Wright stated that "the time of my first employment at sea" was "now more than tenne yeares since". The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

asserts that during the expedition Wright called himself "Captain Edward Carelesse", and that he was also the captain

of the Hope in Sir Francis Drake

's voyage of 1585–1586 to the West Indies

, which evacuated Sir Walter Raleigh

's Colony of Virginia. One of the colonists was the mathematician Thomas Harriot

, and if the Dictionary is correct it is probable that on the return journey to England Wright and Harriot became acquainted and discussed navigational mathematics. However, in a 1939 article, E.J.S. Parsons and W.F. Morris note that in Capt. Walter Bigges and Lt. Crofts' book A Summarie and True Discourse of Sir Frances Drakes West Indian Voyage (1589), Edward Careless was referred to as the commander of the Hope, but Wright was not mentioned. Further, while Wright spoke several times of his participation in the Azores expedition, he never alluded to any other voyage. Although the reference to his "first employment" in The Haven-finding Art suggests an earlier venture, there is no evidence that he went to the West Indies. Gonville and Caius College holds no records showing that Wright was granted leave before 1589. There is nothing to suggest that Wright ever went to sea again after his expedition with the Earl of Cumberland.

Wright resumed his Cambridge fellowship upon returning from the Azores in 1589, but it appears that he soon moved to London for he was there with Christopher Heydon making observations of the sun between 1594 and 1597, and on 8 August 1595 Wright married Ursula Warren (died 1625) at the parish church

of St. Michael, Cornhill

, in the City of London

. They had a son, Samuel (1596–1616), who was himself admitted as a sizar at Caius on 7 July 1612. The St. Michael parish register also contains references to other children of Wright, all of whom died before 1617. Wright resigned his fellowship in 1596.

Wright helped the mathematician and globe maker Emery Molyneux

Wright helped the mathematician and globe maker Emery Molyneux

to plot coastlines on his terrestrial globe, and translated some of the explanatory legends into Latin

. Molyneux's terrestrial and celestial globes, the first to be manufactured in England, were published in late 1592 or early 1593, and Wright explained their use in his 1599 work Certaine Errors in Navigation. He dedicated the book to Cumberland, to whom he had presented a manuscript of the work in 1592, stating in the preface it was through Cumberland that he "was first moved, and received maintenance to divert my mathematical studies, from a theorical speculation in the Universitie, to the practical demonstration of the use of Navigation".

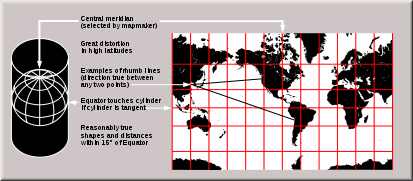

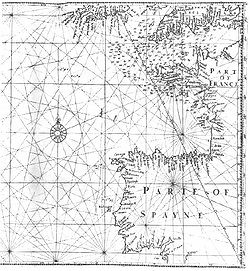

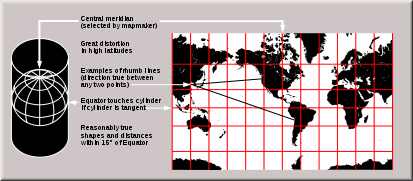

The most significant aspect of the book was Wright's method for dividing the meridian; an explanation of how he had constructed a table for the division; and the uses of this information for navigation. Essentially, the problem that occupied Wright was how to depict accurately a globe on a two-dimensional map according to the projection used by Gerardus Mercator

in his map of 1569. Mercator's projection was advantageous for nautical purposes as it represented lines of constant true bearing

or true course

, known as loxodromes or rhumb line

s, as straight lines. However, Mercator had not explained his method.

On a globe, circles of latitude (also known as parallels) get smaller as they move away from the Equator

towards the North

or South Pole

. Thus, in the Mercator projection, when a globe is "unwrapped" on to a rectangular map, the parallels need to be stretched to the length of the Equator. In addition, parallels are further apart as they approach the poles

. Wright compiled a table with three columns. The first two columns contained the degrees

and minutes

of latitude

s for parallels spaced 10 minutes apart on a sphere, while the third column had the parallel's projected distance from the Equator. Any cartographer or navigator could therefore lay out a Mercator grid for himself by consulting the table. Wright explained:

While the first edition of Certaine Errors contained an abridged table six pages in length, in the second edition which appeared in 1610 Wright published a full table across 23 pages with figures for parallels at one-minute intervals. The table is remarkably accurate – American geography professor Mark Monmonier

While the first edition of Certaine Errors contained an abridged table six pages in length, in the second edition which appeared in 1610 Wright published a full table across 23 pages with figures for parallels at one-minute intervals. The table is remarkably accurate – American geography professor Mark Monmonier

wrote a computer program to replicate Wright's calculations, and determined that for a Mercator map of the world 3 foot (0.9144 m) wide, the greatest discrepancy between Wright's table and the program was only 0.00039 inch (0.009906 mm) on the map. In the second edition Wright also incorporated various improvements, including proposals for determining the magnitude of the Earth and reckoning common linear measurements as a proportion of a degree on the Earth's surface "that they might not depend on the uncertain length of a barley-corn"; a correction of errors arising from the eccentricity of the eye when making observations using the cross-staff

; amendments in tables of declination

s and the positions of the sun and the stars, which were based on observations he had made together with Christopher Heydon using a 6 feet (1.8 m) quadrant

; and a large table of the variation of the compass

as observed in different parts of the world, to show that it is not caused by any magnetic pole. He also incorporated a translation of Rodrigo Zamorano

's Compendio de la Arte de Navegar (Compendium of the Art of Navigation, Seville, 1581; 2nd ed., 1588).

Wright was prompted to publish the book after two incidents of his text, which had been prepared some years earlier, being used without attribution. He had allowed his table of meridional parts to be published by Thomas Blundeville

Wright was prompted to publish the book after two incidents of his text, which had been prepared some years earlier, being used without attribution. He had allowed his table of meridional parts to be published by Thomas Blundeville

in his Exercises (1594) and in William Barlow

's The Navigator's Supply (1597), although only Blundeville acknowledged Wright by name. However, an experienced navigator, believed to be Abraham Kendall, borrowed a draft of Wright's manuscript and, unknown to him, made a copy of it which he took on Sir Francis Drake

's 1595 expedition to the West Indies. In 1596 Kendall died at sea. The copy of Wright's work in his possession was brought back to London and wrongly believed to be by Kendall, until the Earl of Cumberland passed it to Wright and he recognised it as his work. Also around this time, the Dutch cartographer Jodocus Hondius

borrowed Wright's draft manuscript for a short time after promising not to publish its contents without his permission. However, Hondius then employed Wright's calculations without acknowledging him for several regional maps and in his world map published in Amsterdam in 1597. This map is often referred to as the "Christian Knight Map" for its engraving of a Christian knight battling sin, the flesh and the Devil. Although Hondius sent Wright a letter containing a faint apology, Wright condemned Hondius's deceit and greed in the preface to Certaine Errors. He wryly commented: "But the way how this [Mercator projection] should be done, I learned neither of Mercator, nor of any man els. And in that point I wish I had beene as wise as he in keeping it more charily to myself".

The first map to be prepared according to Wright's projection was published in his book, and showed the route of Cumberland's expedition to the Azores. A manuscript version of this map is preserved at Hatfield House

; it is believed to have been drawn about 1595. Following this, Wright created a new world map, the first map of the globe to be produced in England and the first to use the Mercator projection

since Gerardus Mercator's 1569 original. Based on Molyneux's terrestrial globe, it corrected a number of errors in the earlier work by Mercator. The map, often called the Wright–Molyneux Map, first appeared in the second volume of Richard Hakluyt

's The Principal Navigations, Voiages, Traffiques and Discoueries of the English Nation (1599). Unlike many contemporary maps and charts which contained fantastic speculations about unexplored lands, Wright's map has a minimum of detail and blank areas wherever information was lacking. The map was one of the earliest to use the name "Virginia

". Shakespeare

alluded to the map in Twelfth Night (1600–1601), when Maria says of Malvolio

: "He does smile his face into more lynes, than is in the new Mappe, with the augmentation of the Indies." Another world map, larger and with updated details, appeared in the second edition of Certaine Errors (1610).

Wright translated into English De Havenvinding (1599) by the Flemish

mathematician and engineer Simon Stevin

, which appeared in the same year as The Haven-Finding Art, or the Way to Find any Haven or Place at Sea, by the Latitude and Variation. He also wrote the preface to physician and scientist William Gilbert's great work De Magnete, Magneticisque Corporibus, et de Magno Magnete Tellure

(The Magnet, Magnetic Bodies, and the Great Magnet the Earth, 1600), in which Gilbert described his experiments which led to the conclusion that the Earth was magnetic

, and introduced the term electricus to describe the phenomenon of static electricity

produced by rubbing amber

(called ēlectrum in Classical Latin

, derived from ’ήλεκτρον (elektron) in Ancient Greek

). According to the mathematician and physician Mark Ridley

, chapter 12 of book 4 of De Magnete, which explained how astronomical observations

could be used to determine the magnetic variation

, was actually Wright's work.

Gilbert had invented a dip-compass

and compiled a table recording the dip

of the needle below the horizon. Wright believed that this device would prove to be extremely useful in determining latitude and, with the help of Blundeville and Briggs, wrote a small pamphlet called The Making, Description and Use of the Two Instruments for Sea-men to find out the Latitude ... First Invented by Dr. Gilbert. It was published in 1602 in Blundeville's book The Theoriques of the Seuen Planets. That same year he authored The Description and Use of the Sphære (not published till 1613), and in 1605 published a new edition of the widely used work The Safegarde of Saylers.

Wright also developed a reputation as a surveyor

Wright also developed a reputation as a surveyor

on land. He prepared "a plat

of part of the waye whereby a newe River may be brought from Uxbridge

to St. James

, Whitehall

, Westminster

[,] the Strand

, St Giles

, Holbourne

and London", However, according to a 1615 paper in Latin in the annals of Gonville and Caius College, he was prevented from bringing this plan to fruition "by the tricks of others". Nonetheless, early in the first decade of the 17th century, he was appointed by Sir Hugh Myddelton as surveyor to the New River

project, which successfully directed the course of a new man-made channel to bring clean water from Chadwell Spring at Ware, Hertfordshire

, to Islington

, London. Although the distance in a straight line from Ware to London is only slightly more than 20 miles (32.2 km), the project required a high degree of surveying skill on Wright's part as it was necessary for the river to take a route of over 40 miles following the 100 feet (30.5 m) contour line

on the west side of the Lea Valley

. As the technology of the time did not extend to large pumps or pipes, the water flow had to depend on gravity through canals or aqueduct

s over an average fall of 5.5 inches a mile (approximately 8.7 centimetres per kilometre).

Work on the New River started in 1608 – the date of a monument at Chadwell Spring – but halted near Wormley, Hertfordshire, in 1610. The stoppage has been attributed to factors such as Myddelton facing difficulties in raising funds, and landowners along the route opposing the acquisition of their lands on the ground that the river would turn their meadows into "bogs and quagmires". Although the landowners petitioned Parliament

, they did not succeed in having the legislation authorizing the project repealed prior to Parliament being dissolved in 1611; the work resumed later that year. The New River was officially opened on 29 September 1613 by the Lord Mayor of London, Sir John Swinnerton, at the Round Pond, New River Head, in Islington. It still supplies the capital with water today.

to be paid for this. At the beginning of the 17th century, Wright succeeded Thomas Hood

as a mathematics lecturer under the patronage of the wealthy merchants Sir Thomas Smyth and Sir John Wolstenholme; the lectures were held in Smyth's house in Philpot Lane. By 1612 or 1614 the East India Company had taken on sponsorship of these lectures for an annual fee of £

50 (about £6,500 as of 2007). Wright was also mathematics tutor to the son of James I

, the heir apparent

Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales

, from 1608 or 1609 until the latter's death at the age of 18 on 6 November 1612. Wright was described as "a very poor man" in the Prince's will and left the sum of £30 8s

(about £4,300 in 2007). To the Prince, who was greatly interested in the science of navigation, Wright dedicated the second edition of Certaine Errors (1610) and the world map published therein. He also drew various maps for him, including a "sea chart of the N.-W. Passage

; a paradoxall sea-chart of the World from 30° Latitude northwards; [and] a plat

of the drowned groundes about Elye

, Lincolnshire

, Cambridgeshire

, &c".

Wright was a skilled designer of mathematical instruments. According to the 1615 Caius annals, "[h]e was excellent both in contrivance and execution, nor was he inferior to the most ingenious mechanic in the making of instruments, either of brass or any other matter". For Prince Henry, he made models of an astrolabe

and a pantograph

, and created or arranged to be created out of wood a form of armillary sphere

which replicated the motions of the celestial sphere

, the circular motions of the sun and moon, and the places and possibilities of them eclipsing

each other. The sphere was designed for a motion of 17,100 years, if the machine should last that long. In 1613 Wright published The Description and Use of the Sphære, which described the use of this device. The sphere was lost during the English Civil War

, but found in 1646 in the Tower of London

by the mathematician and surveyor Sir Jonas Moore

, who was later appointed Surveyor General of the Ordnance Office

and became a patron and the principal driving force behind the establishment of the Royal Observatory at Greenwich

. Moore asked the King to let him have it, restored the instrument at his own expense and deposited it at his own house "in the Tower".

The Caius annals also report that Wright "had formed many other useful designs, but was hindered by death from bringing them to perfection". The 1610 edition of Certaine Errors contained descriptions of the "sea-ring", which consisted of a universal ring dial mounted over a magnetic compass

that enabled mariners to determine readily the magnetic variation of the compass, the sun's altitude and the time of day in any place if the latitude was known; the "sea-quadrant", for the taking of altitudes by a forward or backward observation; and a device for finding latitude when one was not on the meridian using the height of the pole star.

In 1614 Wright published a small book called A Short Treatise of Dialling: Shewing, the Making of All Sorts of Sun-dials, but he was mainly preoccupied with John Napier

In 1614 Wright published a small book called A Short Treatise of Dialling: Shewing, the Making of All Sorts of Sun-dials, but he was mainly preoccupied with John Napier

's Mirifici Logarithmorum Canonis Descriptio (Description of the Wonderful Rule of Logarithms), which introduced the idea of logarithm

s. Wright at once saw the value of logarithms as an aid to navigation, and lost no time in preparing a translation which he submitted to Napier himself. The preface to Wright's edition consists of a translation of the preface to the Descriptio, together with the addition of the following sentences written by Napier himself:

While working on the translation, Wright died in late November 1615 and was buried on 2 December 1615 at St. Dionis Backchurch

in the City of London. The Caius annals noted that although he "was rich in fame, and in the promises of the great, yet he died poor, to the scandal of an ungrateful age". Wright's translation of Napier, which incorporated tables that Wright had supplemented and further information by Henry Briggs, was completed by Wright's son Samuel and arranged to be printed by Briggs. It appeared posthumously as A Description of the Admirable Table of Logarithmes in 1616, and in it Wright was lauded in verse as "[t]hat famous, learned, Errors true Corrector, / England's great Pilot, Mariners Director".

According to Parsons and Morris, the use of Wright's publications by later mathematicians is the "greatest tribute to his life's work". Wright's work was relied on by Dutch astronomer and mathematician Willebrord Snellius

, noted for the law of refraction

now known as Snell's law

, for his navigation treatise Tiphys Batavus (Batavian Tiphys, 1624); and by Adriaan Metius

, the geometer and astronomer from Holland, for Primum Mobile

(1631). Following Wright's proposals, Richard Norwood

measured a degree on a great circle

of the earth at 367196 feet (111,921.3 m), publishing the information in 1637. Wright was praised by Charles Saltonstall in The Navigator (1642) and by John Collins

in Navigation by the Mariners Plain Scale New Plain'd (1659), Collins stating that Mercator's chart ought "more properly to be called Wright's chart". The Caius annals contained the following epitaph: "Of him it may truly be said, that he studied more to serve the public than himself".

. Another version of the work published in the same year was entitled . Later editions and reprints:

. Another version of the work published in the same year was entitled . Later editions and reprints:

}.

}.

}. Photoreprint of the 1599 edition.

. Later editions and reprints:

}.

}.

.

. Reprinted as:

. Reprinted as:

}.

.

. Later editions and reprints:

}.

}.

Mathematician

A mathematician is a person whose primary area of study is the field of mathematics. Mathematicians are concerned with quantity, structure, space, and change....

and cartographer noted for his book Certaine Errors in Navigation (1599; 2nd ed., 1610), which for the first time explained the mathematical basis of the Mercator projection

Mercator projection

The Mercator projection is a cylindrical map projection presented by the Belgian geographer and cartographer Gerardus Mercator, in 1569. It became the standard map projection for nautical purposes because of its ability to represent lines of constant course, known as rhumb lines or loxodromes, as...

, and set out a reference table giving the linear scale multiplication factor as a function of latitude

Latitude

In geography, the latitude of a location on the Earth is the angular distance of that location south or north of the Equator. The latitude is an angle, and is usually measured in degrees . The equator has a latitude of 0°, the North pole has a latitude of 90° north , and the South pole has a...

, calculated for each minute of arc

Minute of arc

A minute of arc, arcminute, or minute of angle , is a unit of angular measurement equal to one sixtieth of one degree. In turn, a second of arc or arcsecond is one sixtieth of one minute of arc....

up to a latitude of 75°. This was in fact a table of values of the integral of the secant function

Integral of the secant function

The integral of the secant function of trigonometry was the subject of one of the "outstanding open problems of the mid-seventeenth century", solved in 1668 by James Gregory. In 1599, Edward Wright evaluated the integral by numerical methods – what today we would call Riemann sums...

, and was the essential step needed to make practical both the making and the navigational use of Mercator charts.

Wright was born at Garveston

Garvestone

Garvestone is a village and civil parish in the Breckland district, in Norfolk, England. It is between the towns of Dereham and Wymondham. In the 2001 census the parish, which also includes the villages of Thuxton and Reymerston, had a population of 606.Garvestone lies on the upper reaches of...

and educated at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge

Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge

Gonville and Caius College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge in Cambridge, England. The college is often referred to simply as "Caius" , after its second founder, John Keys, who fashionably latinised the spelling of his name after studying in Italy.- Outline :Gonville and...

, where he became a fellow from 1587 to 1596. In 1589 the College granted him leave after Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I was queen regnant of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death. Sometimes called The Virgin Queen, Gloriana, or Good Queen Bess, Elizabeth was the fifth and last monarch of the Tudor dynasty...

requested that he carry out navigation

Navigation

Navigation is the process of monitoring and controlling the movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another. It is also the term of art used for the specialized knowledge used by navigators to perform navigation tasks...

al studies with a raiding expedition organised by the Earl of Cumberland

George Clifford, 3rd Earl of Cumberland

Sir George Clifford, 3rd Earl of Cumberland, KG was an English peer, as well as a naval commander and courtier in the court of Queen Elizabeth I.-Background:...

to the Azores

Azores

The Archipelago of the Azores is composed of nine volcanic islands situated in the middle of the North Atlantic Ocean, and is located about west from Lisbon and about east from the east coast of North America. The islands, and their economic exclusion zone, form the Autonomous Region of the...

to capture Spanish galleon

Galleon

A galleon was a large, multi-decked sailing ship used primarily by European states from the 16th to 18th centuries. Whether used for war or commerce, they were generally armed with the demi-culverin type of cannon.-Etymology:...

s. The expedition's route was the subject of the first map to be prepared according to Wright's projection, which was published in Certaine Errors in 1599. The same year, Wright created and published the first world map produced in England and the first to use the Mercator projection since Gerardus Mercator

Gerardus Mercator

thumb|right|200px|Gerardus MercatorGerardus Mercator was a cartographer, born in Rupelmonde in the Hapsburg County of Flanders, part of the Holy Roman Empire. He is remembered for the Mercator projection world map, which is named after him...

's original 1569 map.

Not long after 1600 Wright was appointed as surveyor

Surveying

See Also: Public Land Survey SystemSurveying or land surveying is the technique, profession, and science of accurately determining the terrestrial or three-dimensional position of points and the distances and angles between them...

to the New River

New River (England)

The New River is an artificial waterway in England, opened in 1613 to supply London with fresh drinking water taken from the River Lea and from Amwell Springs , and other springs and wells along its course....

project, which successfully directed the course of a new man-made channel to bring clean water from Ware, Hertfordshire

Hertfordshire

Hertfordshire is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in the East region of England. The county town is Hertford.The county is one of the Home Counties and lies inland, bordered by Greater London , Buckinghamshire , Bedfordshire , Cambridgeshire and...

, to Islington

Islington

Islington is a neighbourhood in Greater London, England and forms the central district of the London Borough of Islington. It is a district of Inner London, spanning from Islington High Street to Highbury Fields, encompassing the area around the busy Upper Street...

, London. Around this time, Wright also lectured mathematics to merchant seamen, and from 1608 or 1609 was mathematics tutor to the son of James I

James I of England

James VI and I was King of Scots as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the English and Scottish crowns on 24 March 1603...

, the heir apparent

Heir apparent

An heir apparent or heiress apparent is a person who is first in line of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting, except by a change in the rules of succession....

Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales

Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales

Henry Frederick Stuart, Prince of Wales was the elder son of King James I & VI and Anne of Denmark. His name derives from his grandfathers: Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley and Frederick II of Denmark. Prince Henry was widely seen as a bright and promising heir to his father's throne...

, until the latter's very early death at the age of 18 in 1612. A skilled designer of mathematical instrument

Mathematical instrument

A mathematical instrument is a tool or device used in the study or practice of mathematics.Most instruments are used within the field of geometry, including the ruler, dividers, protractor, set square, compass, ellipsograph and opisometer...

s, Wright made models of an astrolabe

Astrolabe

An astrolabe is an elaborate inclinometer, historically used by astronomers, navigators, and astrologers. Its many uses include locating and predicting the positions of the Sun, Moon, planets, and stars, determining local time given local latitude and longitude, surveying, triangulation, and to...

and a pantograph

Pantograph

A pantograph is a mechanical linkage connected in a special manner based on parallelograms so that the movement of one pen, in tracing an image, produces identical movements in a second pen...

, and a type of armillary sphere

Armillary sphere

An armillary sphere is a model of objects in the sky , consisting of a spherical framework of rings, centred on Earth, that represent lines of celestial longitude and latitude and other astronomically important features such as the ecliptic...

for Prince Henry. In the 1610 edition of Certaine Errors he described inventions such as the "sea-ring" that enabled mariners to determine the magnetic variation

Magnetic declination

Magnetic declination is the angle between magnetic north and true north. The declination is positive when the magnetic north is east of true north. The term magnetic variation is a synonym, and is more often used in navigation...

of the compass

Compass

A compass is a navigational instrument that shows directions in a frame of reference that is stationary relative to the surface of the earth. The frame of reference defines the four cardinal directions – north, south, east, and west. Intermediate directions are also defined...

, the sun's altitude and the time of day in any place if the latitude was known; and a device for finding latitude when one was not on the meridian

Meridian (geography)

A meridian is an imaginary line on the Earth's surface from the North Pole to the South Pole that connects all locations along it with a given longitude. The position of a point along the meridian is given by its latitude. Each meridian is perpendicular to all circles of latitude...

using the height of the pole star.

Apart from a number of other books and pamphlets, Wright translated John Napier

John Napier

John Napier of Merchiston – also signed as Neper, Nepair – named Marvellous Merchiston, was a Scottish mathematician, physicist, astronomer & astrologer, and also the 8th Laird of Merchistoun. He was the son of Sir Archibald Napier of Merchiston. John Napier is most renowned as the discoverer...

's pioneering 1614 work which introduced the idea of logarithm

Logarithm

The logarithm of a number is the exponent by which another fixed value, the base, has to be raised to produce that number. For example, the logarithm of 1000 to base 10 is 3, because 1000 is 10 to the power 3: More generally, if x = by, then y is the logarithm of x to base b, and is written...

s from Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

into English. This was published after Wright's death as A Description of the Admirable Table of Logarithmes (1616). Wright's work influenced, among other persons, Dutch astronomer and mathematician Willebrord Snellius

Willebrord Snellius

Willebrord Snellius was a Dutch astronomer and mathematician. In the west, especially the English speaking countries, his name has been attached to the law of refraction of light for several centuries, but it is now known that this law was first discovered by Ibn Sahl in 984...

; Adriaan Metius

Metius

Adriaan Adriaanszoon, called Metius, , was a Dutch geometer and astronomer. He was born in Alkmaar. The name Metius comes from the Dutch word meten , and therefore means something like "measurer" or "surveyor."-Father and brother:Metius was born at Alkmaar, North Holland...

, the geometer and astronomer from Holland; and the English mathematician Richard Norwood

Richard Norwood

Richard Norwood was an English mathematician, diver, and surveyor, connected with Isaac Newton. He has also been called "Bermuda’s outstanding genius of the seventeenth century"...

, who calculated the length of a degree

Degree (angle)

A degree , usually denoted by ° , is a measurement of plane angle, representing 1⁄360 of a full rotation; one degree is equivalent to π/180 radians...

on a great circle

Great circle

A great circle, also known as a Riemannian circle, of a sphere is the intersection of the sphere and a plane which passes through the center point of the sphere, as opposed to a general circle of a sphere where the plane is not required to pass through the center...

of the earth using a method proposed by Wright.

Family and education

The younger son of Henry and Margaret Wright, Edward Wright was born in the village of GarvestonGarvestone

Garvestone is a village and civil parish in the Breckland district, in Norfolk, England. It is between the towns of Dereham and Wymondham. In the 2001 census the parish, which also includes the villages of Thuxton and Reymerston, had a population of 606.Garvestone lies on the upper reaches of...

in Norfolk

Norfolk

Norfolk is a low-lying county in the East of England. It has borders with Lincolnshire to the west, Cambridgeshire to the west and southwest and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the North Sea coast and to the north-west the county is bordered by The Wash. The county...

, East Anglia

East Anglia

East Anglia is a traditional name for a region of eastern England, named after an ancient Anglo-Saxon kingdom, the Kingdom of the East Angles. The Angles took their name from their homeland Angeln, in northern Germany. East Anglia initially consisted of Norfolk and Suffolk, but upon the marriage of...

, and was baptised

Baptism

In Christianity, baptism is for the majority the rite of admission , almost invariably with the use of water, into the Christian Church generally and also membership of a particular church tradition...

there on 8 October 1561. It is possible that he followed in the footsteps of his elder brother Thomas (died 1579) and went to school in Hardingham

Hardingham

Hardingham is a civil parish in the English county of Norfolk.It covers an area of and had a population of 274 in 110 households as of the 2001 census. For the purposes of local government, it falls within the district of Breckland....

. The family was of modest means, and he matriculated

Matriculation

Matriculation, in the broadest sense, means to be registered or added to a list, from the Latin matricula – little list. In Scottish heraldry, for instance, a matriculation is a registration of armorial bearings...

at Gonville and Caius College

Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge

Gonville and Caius College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge in Cambridge, England. The college is often referred to simply as "Caius" , after its second founder, John Keys, who fashionably latinised the spelling of his name after studying in Italy.- Outline :Gonville and...

, University of Cambridge

University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a public research university located in Cambridge, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest university in both the United Kingdom and the English-speaking world , and the seventh-oldest globally...

, on 8 December 1576 as a sizar

Sizar

At Trinity College, Dublin and the University of Cambridge, a sizar is a student who receives some form of assistance such as meals, lower fees or lodging during his or her period of study, in some cases in return for doing a defined job....

. Sizars were students of limited means who were charged lower fees and obtained free food and/or lodging and other assistance during their period of study, often in exchange for performing work at their colleges.

Wright was conferred a Bachelor of Arts

Bachelor of Arts

A Bachelor of Arts , from the Latin artium baccalaureus, is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate course or program in either the liberal arts, the sciences, or both...

(B.A.) in 1580–1581. He remained a scholar at Caius, receiving his Master of Arts (M.A.) there in 1584, and holding a fellowship between 1587 and 1596. At Cambridge, he was a close friend of Robert Devereux

Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex

Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, KG was an English nobleman and a favourite of Elizabeth I. Politically ambitious, and a committed general, he was placed under house arrest following a poor campaign in Ireland during the Nine Years' War in 1599...

, later the Second Earl of Essex

Earl of Essex

Earl of Essex is a title that has been held by several families and individuals. The earldom was first created in the 12th century for Geoffrey II de Mandeville . Upon the death of the third earl in 1189, the title became dormant or extinct...

, and met him to discuss his studies even in the weeks before Devereux's rebellion against Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I was queen regnant of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death. Sometimes called The Virgin Queen, Gloriana, or Good Queen Bess, Elizabeth was the fifth and last monarch of the Tudor dynasty...

in 1600–1601. In addition, he came to know the mathematician Henry Briggs

Henry Briggs (mathematician)

Henry Briggs was an English mathematician notable for changing the original logarithms invented by John Napier into common logarithms, which are sometimes known as Briggsian logarithms in his honour....

; and the soldier and astrologer

Astrologer

An astrologer practices one or more forms of astrology. Typically an astrologer draws a horoscope for the time of an event, such as a person's birth, and interprets celestial points and their placements at the time of the event to better understand someone, determine the auspiciousness of an...

Christopher Heydon

Christopher Heydon

Sir Christopher Heydon was an English soldier, Member of Parliament, and writer on astrology.-Background:Born in Surrey, Heydon was the eldest son of Sir William Heydon of Baconsthorpe, Norfolk, and his wife Anne, daughter of Sir William Woodhouse of Hickling, Norfolk...

, who was also Devereux's friend. Heydon later made astronomical observations with instruments Wright made for him.

Foreign expedition

Navigation

Navigation is the process of monitoring and controlling the movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another. It is also the term of art used for the specialized knowledge used by navigators to perform navigation tasks...

al studies with a raiding expedition organised by the Earl of Cumberland

George Clifford, 3rd Earl of Cumberland

Sir George Clifford, 3rd Earl of Cumberland, KG was an English peer, as well as a naval commander and courtier in the court of Queen Elizabeth I.-Background:...

to the Azores

Azores

The Archipelago of the Azores is composed of nine volcanic islands situated in the middle of the North Atlantic Ocean, and is located about west from Lisbon and about east from the east coast of North America. The islands, and their economic exclusion zone, form the Autonomous Region of the...

to capture Spanish galleon

Galleon

A galleon was a large, multi-decked sailing ship used primarily by European states from the 16th to 18th centuries. Whether used for war or commerce, they were generally armed with the demi-culverin type of cannon.-Etymology:...

s. The Queen effectively ordered Caius to grant him leave of absence for this purpose, although the College expressed this more diplomatically by granting him a sabbatical "by Royal mandate". Wright participated in the confiscation of "lawful" prizes

Prize (law)

Prize is a term used in admiralty law to refer to equipment, vehicles, vessels, and cargo captured during armed conflict. The most common use of prize in this sense is the capture of an enemy ship and its cargo as a prize of war. In the past, it was common that the capturing force would be allotted...

from the French, Portuguese and Spanish – Derek Ingram, a life fellow of Caius, has called him "the only Fellow of Caius ever to be granted sabbatical leave in order to engage in piracy". Wright sailed with Cumberland in the Victory from Plymouth

Plymouth

Plymouth is a city and unitary authority area on the coast of Devon, England, about south-west of London. It is built between the mouths of the rivers Plym to the east and Tamar to the west, where they join Plymouth Sound...

on 8 June 1589; they returned to Falmouth

Falmouth, Cornwall

Falmouth is a town, civil parish and port on the River Fal on the south coast of Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It has a total resident population of 21,635.Falmouth is the terminus of the A39, which begins some 200 miles away in Bath, Somerset....

on 27 December of the same year. An account of the expedition is appended to Wright's work Certaine Errors of Navigation (1599), and while it refers to Wright in the third person it is believed to have been written by him.

In Wright's account of the Azores expedition, he listed as one of the expedition's members a "Captaine Edwarde Carelesse, alias Wright, who in S. Frauncis Drakes West-Indian voiage was Captaine of the Hope". In another work, The Haven-finding Art (1599) (see below), Wright stated that "the time of my first employment at sea" was "now more than tenne yeares since". The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Dictionary of National Biography

The Dictionary of National Biography is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published from 1885...

asserts that during the expedition Wright called himself "Captain Edward Carelesse", and that he was also the captain

Captain (nautical)

A sea captain is a licensed mariner in ultimate command of the vessel. The captain is responsible for its safe and efficient operation, including cargo operations, navigation, crew management and ensuring that the vessel complies with local and international laws, as well as company and flag...

of the Hope in Sir Francis Drake

Francis Drake

Sir Francis Drake, Vice Admiral was an English sea captain, privateer, navigator, slaver, and politician of the Elizabethan era. Elizabeth I of England awarded Drake a knighthood in 1581. He was second-in-command of the English fleet against the Spanish Armada in 1588. He also carried out the...

's voyage of 1585–1586 to the West Indies

Caribbean

The Caribbean is a crescent-shaped group of islands more than 2,000 miles long separating the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea, to the west and south, from the Atlantic Ocean, to the east and north...

, which evacuated Sir Walter Raleigh

Walter Raleigh

Sir Walter Raleigh was an English aristocrat, writer, poet, soldier, courtier, spy, and explorer. He is also well known for popularising tobacco in England....

's Colony of Virginia. One of the colonists was the mathematician Thomas Harriot

Thomas Harriot

Thomas Harriot was an English astronomer, mathematician, ethnographer, and translator. Some sources give his surname as Harriott or Hariot or Heriot. He is sometimes credited with the introduction of the potato to Great Britain and Ireland...

, and if the Dictionary is correct it is probable that on the return journey to England Wright and Harriot became acquainted and discussed navigational mathematics. However, in a 1939 article, E.J.S. Parsons and W.F. Morris note that in Capt. Walter Bigges and Lt. Crofts' book A Summarie and True Discourse of Sir Frances Drakes West Indian Voyage (1589), Edward Careless was referred to as the commander of the Hope, but Wright was not mentioned. Further, while Wright spoke several times of his participation in the Azores expedition, he never alluded to any other voyage. Although the reference to his "first employment" in The Haven-finding Art suggests an earlier venture, there is no evidence that he went to the West Indies. Gonville and Caius College holds no records showing that Wright was granted leave before 1589. There is nothing to suggest that Wright ever went to sea again after his expedition with the Earl of Cumberland.

Wright resumed his Cambridge fellowship upon returning from the Azores in 1589, but it appears that he soon moved to London for he was there with Christopher Heydon making observations of the sun between 1594 and 1597, and on 8 August 1595 Wright married Ursula Warren (died 1625) at the parish church

Parish church

A parish church , in Christianity, is the church which acts as the religious centre of a parish, the basic administrative unit of episcopal churches....

of St. Michael, Cornhill

St Michael, Cornhill

St Michael, Cornhill is a medieval parish church in the City of London with pre-Norman Conquest parochial foundation. The medieval structure was lost in the Great Fire of London and the current church was designed by Sir Christopher Wren between 1670-1677....

, in the City of London

City of London

The City of London is a small area within Greater London, England. It is the historic core of London around which the modern conurbation grew and has held city status since time immemorial. The City’s boundaries have remained almost unchanged since the Middle Ages, and it is now only a tiny part of...

. They had a son, Samuel (1596–1616), who was himself admitted as a sizar at Caius on 7 July 1612. The St. Michael parish register also contains references to other children of Wright, all of whom died before 1617. Wright resigned his fellowship in 1596.

Certaine Errors in Navigation

Emery Molyneux

Emery Molyneux was an English Elizabethan maker of globes, mathematical instruments and ordnance. His terrestrial and celestial globes, first published in 1592, were the first to be made in England and the first to be made by an Englishman....

to plot coastlines on his terrestrial globe, and translated some of the explanatory legends into Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

. Molyneux's terrestrial and celestial globes, the first to be manufactured in England, were published in late 1592 or early 1593, and Wright explained their use in his 1599 work Certaine Errors in Navigation. He dedicated the book to Cumberland, to whom he had presented a manuscript of the work in 1592, stating in the preface it was through Cumberland that he "was first moved, and received maintenance to divert my mathematical studies, from a theorical speculation in the Universitie, to the practical demonstration of the use of Navigation".

The most significant aspect of the book was Wright's method for dividing the meridian; an explanation of how he had constructed a table for the division; and the uses of this information for navigation. Essentially, the problem that occupied Wright was how to depict accurately a globe on a two-dimensional map according to the projection used by Gerardus Mercator

Gerardus Mercator

thumb|right|200px|Gerardus MercatorGerardus Mercator was a cartographer, born in Rupelmonde in the Hapsburg County of Flanders, part of the Holy Roman Empire. He is remembered for the Mercator projection world map, which is named after him...

in his map of 1569. Mercator's projection was advantageous for nautical purposes as it represented lines of constant true bearing

Bearing (navigation)

In marine navigation, a bearing is the direction one object is from another object, usually, the direction of an object from one's own vessel. In aircraft navigation, a bearing is the actual compass direction of the forward course of the aircraft...

or true course

Course (navigation)

In navigation, a vehicle's course is the angle that the intended path of the vehicle makes with a fixed reference object . Typically course is measured in degrees from 0° clockwise to 360° in compass convention . Course is customarily expressed in three digits, using preliminary zeros if needed,...

, known as loxodromes or rhumb line

Rhumb line

In navigation, a rhumb line is a line crossing all meridians of longitude at the same angle, i.e. a path derived from a defined initial bearing...

s, as straight lines. However, Mercator had not explained his method.

On a globe, circles of latitude (also known as parallels) get smaller as they move away from the Equator

Equator

An equator is the intersection of a sphere's surface with the plane perpendicular to the sphere's axis of rotation and containing the sphere's center of mass....

towards the North

North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is, subject to the caveats explained below, defined as the point in the northern hemisphere where the Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface...

or South Pole

South Pole

The South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole or Terrestrial South Pole, is one of the two points where the Earth's axis of rotation intersects its surface. It is the southernmost point on the surface of the Earth and lies on the opposite side of the Earth from the North Pole...

. Thus, in the Mercator projection, when a globe is "unwrapped" on to a rectangular map, the parallels need to be stretched to the length of the Equator. In addition, parallels are further apart as they approach the poles

Geographical pole

A geographical pole is either of the two points—the north pole and the south pole—on the surface of a rotating planet where the axis of rotation meets the surface of the body...

. Wright compiled a table with three columns. The first two columns contained the degrees

Degree (angle)

A degree , usually denoted by ° , is a measurement of plane angle, representing 1⁄360 of a full rotation; one degree is equivalent to π/180 radians...

and minutes

Minute of arc

A minute of arc, arcminute, or minute of angle , is a unit of angular measurement equal to one sixtieth of one degree. In turn, a second of arc or arcsecond is one sixtieth of one minute of arc....

of latitude

Latitude

In geography, the latitude of a location on the Earth is the angular distance of that location south or north of the Equator. The latitude is an angle, and is usually measured in degrees . The equator has a latitude of 0°, the North pole has a latitude of 90° north , and the South pole has a...

s for parallels spaced 10 minutes apart on a sphere, while the third column had the parallel's projected distance from the Equator. Any cartographer or navigator could therefore lay out a Mercator grid for himself by consulting the table. Wright explained:

Mark Monmonier

Mark Stephen Monmonier is a Distinguished Professor of Geography at the Maxwell School of Syracuse University. He specializes in toponymy, geography, and geographic information systems. His popular written works show a combination of serious study and a sense of humor. Most of his work is...

wrote a computer program to replicate Wright's calculations, and determined that for a Mercator map of the world 3 foot (0.9144 m) wide, the greatest discrepancy between Wright's table and the program was only 0.00039 inch (0.009906 mm) on the map. In the second edition Wright also incorporated various improvements, including proposals for determining the magnitude of the Earth and reckoning common linear measurements as a proportion of a degree on the Earth's surface "that they might not depend on the uncertain length of a barley-corn"; a correction of errors arising from the eccentricity of the eye when making observations using the cross-staff

Jacob's staff

The Jacob's staff, also called a cross-staff, a ballastella, a fore-staff, or a balestilha is used to refer to several things. This can lead to considerable confusion unless one clarifies the purpose for the object so named...

; amendments in tables of declination

Declination

In astronomy, declination is one of the two coordinates of the equatorial coordinate system, the other being either right ascension or hour angle. Declination in astronomy is comparable to geographic latitude, but projected onto the celestial sphere. Declination is measured in degrees north and...

s and the positions of the sun and the stars, which were based on observations he had made together with Christopher Heydon using a 6 feet (1.8 m) quadrant

Quadrant (instrument)

A quadrant is an instrument that is used to measure angles up to 90°. It was originally proposed by Ptolemy as a better kind of astrolabe. Several different variations of the instrument were later produced by medieval Muslim astronomers.-Types of quadrants:...

; and a large table of the variation of the compass

Magnetic declination

Magnetic declination is the angle between magnetic north and true north. The declination is positive when the magnetic north is east of true north. The term magnetic variation is a synonym, and is more often used in navigation...

as observed in different parts of the world, to show that it is not caused by any magnetic pole. He also incorporated a translation of Rodrigo Zamorano

Rodrigo Zamorano

Rodrigo Zamorano was a cosmographer of the royal house of Philip II of Spain. He was author of several books on navigation, astronomy, calendars and mathematics...

's Compendio de la Arte de Navegar (Compendium of the Art of Navigation, Seville, 1581; 2nd ed., 1588).

Thomas Blundeville

Thomas Blundeville was an English humanist writer and mathematician. He is known for work on logic, astronomy, education and horsemanship, as well as for translations from the Italian. His interests were both wide-ranging and directed towards practical ends, and he adapted freely a number of the...

in his Exercises (1594) and in William Barlow

William Barlow (archdeacon)

-Life:Son of William Barlow and Agatha Wellesbourne, he was born at St David's when his father was bishop of that diocese, and was educated at Balliol College, Oxford. He graduated B. A. in 1564...

's The Navigator's Supply (1597), although only Blundeville acknowledged Wright by name. However, an experienced navigator, believed to be Abraham Kendall, borrowed a draft of Wright's manuscript and, unknown to him, made a copy of it which he took on Sir Francis Drake

Francis Drake

Sir Francis Drake, Vice Admiral was an English sea captain, privateer, navigator, slaver, and politician of the Elizabethan era. Elizabeth I of England awarded Drake a knighthood in 1581. He was second-in-command of the English fleet against the Spanish Armada in 1588. He also carried out the...

's 1595 expedition to the West Indies. In 1596 Kendall died at sea. The copy of Wright's work in his possession was brought back to London and wrongly believed to be by Kendall, until the Earl of Cumberland passed it to Wright and he recognised it as his work. Also around this time, the Dutch cartographer Jodocus Hondius

Jodocus Hondius

Jodocus Hondius , sometimes called Jodocus Hondius the Elder to distinguish him from his son Henricus Hondius II, was a Flemish artist, engraver, and cartographer...

borrowed Wright's draft manuscript for a short time after promising not to publish its contents without his permission. However, Hondius then employed Wright's calculations without acknowledging him for several regional maps and in his world map published in Amsterdam in 1597. This map is often referred to as the "Christian Knight Map" for its engraving of a Christian knight battling sin, the flesh and the Devil. Although Hondius sent Wright a letter containing a faint apology, Wright condemned Hondius's deceit and greed in the preface to Certaine Errors. He wryly commented: "But the way how this [Mercator projection] should be done, I learned neither of Mercator, nor of any man els. And in that point I wish I had beene as wise as he in keeping it more charily to myself".

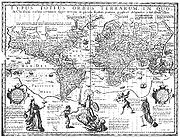

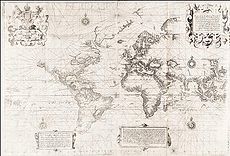

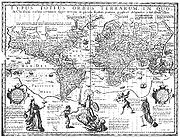

The first map to be prepared according to Wright's projection was published in his book, and showed the route of Cumberland's expedition to the Azores. A manuscript version of this map is preserved at Hatfield House

Hatfield House

Hatfield House is a country house set in a large park, the Great Park, on the eastern side of the town of Hatfield, Hertfordshire, England. The present Jacobean house was built in 1611 by Robert Cecil, First Earl of Salisbury and Chief Minister to King James I and has been the home of the Cecil...

; it is believed to have been drawn about 1595. Following this, Wright created a new world map, the first map of the globe to be produced in England and the first to use the Mercator projection

Mercator projection

The Mercator projection is a cylindrical map projection presented by the Belgian geographer and cartographer Gerardus Mercator, in 1569. It became the standard map projection for nautical purposes because of its ability to represent lines of constant course, known as rhumb lines or loxodromes, as...

since Gerardus Mercator's 1569 original. Based on Molyneux's terrestrial globe, it corrected a number of errors in the earlier work by Mercator. The map, often called the Wright–Molyneux Map, first appeared in the second volume of Richard Hakluyt

Richard Hakluyt

Richard Hakluyt was an English writer. He is principally remembered for his efforts in promoting and supporting the settlement of North America by the English through his works, notably Divers Voyages Touching the Discoverie of America and The Principal Navigations, Voiages, Traffiques and...

's The Principal Navigations, Voiages, Traffiques and Discoueries of the English Nation (1599). Unlike many contemporary maps and charts which contained fantastic speculations about unexplored lands, Wright's map has a minimum of detail and blank areas wherever information was lacking. The map was one of the earliest to use the name "Virginia

Virginia

The Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there...

". Shakespeare

William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare was an English poet and playwright, widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's national poet and the "Bard of Avon"...

alluded to the map in Twelfth Night (1600–1601), when Maria says of Malvolio

Malvolio

Malvolio is the steward of Olivia's household in William Shakespeare's comedy, Twelfth Night, or What You Will.-Style:Malvolio's ethical values are commonly used to define his appearance.In the play, Malvolio is defined as a "kind of" Puritan...

: "He does smile his face into more lynes, than is in the new Mappe, with the augmentation of the Indies." Another world map, larger and with updated details, appeared in the second edition of Certaine Errors (1610).

Wright translated into English De Havenvinding (1599) by the Flemish

Flanders

Flanders is the community of the Flemings but also one of the institutions in Belgium, and a geographical region located in parts of present-day Belgium, France and the Netherlands. "Flanders" can also refer to the northern part of Belgium that contains Brussels, Bruges, Ghent and Antwerp...

mathematician and engineer Simon Stevin

Simon Stevin

Simon Stevin was a Flemish mathematician and military engineer. He was active in a great many areas of science and engineering, both theoretical and practical...

, which appeared in the same year as The Haven-Finding Art, or the Way to Find any Haven or Place at Sea, by the Latitude and Variation. He also wrote the preface to physician and scientist William Gilbert's great work De Magnete, Magneticisque Corporibus, et de Magno Magnete Tellure

De Magnete

De Magnete, Magneticisque Corporibus, et de Magno Magnete Tellure is a scientific work published in 1600 by the English physician and scientist William Gilbert and his partner Aaron Dowling...

(The Magnet, Magnetic Bodies, and the Great Magnet the Earth, 1600), in which Gilbert described his experiments which led to the conclusion that the Earth was magnetic

Earth's magnetic field

Earth's magnetic field is the magnetic field that extends from the Earth's inner core to where it meets the solar wind, a stream of energetic particles emanating from the Sun...

, and introduced the term electricus to describe the phenomenon of static electricity

Static electricity

Static electricity refers to the build-up of electric charge on the surface of objects. The static charges remain on an object until they either bleed off to ground or are quickly neutralized by a discharge. Static electricity can be contrasted with current electricity, which can be delivered...

produced by rubbing amber

Amber

Amber is fossilized tree resin , which has been appreciated for its color and natural beauty since Neolithic times. Amber is used as an ingredient in perfumes, as a healing agent in folk medicine, and as jewelry. There are five classes of amber, defined on the basis of their chemical constituents...

(called ēlectrum in Classical Latin

Classical Latin

Classical Latin in simplest terms is the socio-linguistic register of the Latin language regarded by the enfranchised and empowered populations of the late Roman republic and the Roman empire as good Latin. Most writers during this time made use of it...

, derived from ’ήλεκτρον (elektron) in Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek is the stage of the Greek language in the periods spanning the times c. 9th–6th centuries BC, , c. 5th–4th centuries BC , and the c. 3rd century BC – 6th century AD of ancient Greece and the ancient world; being predated in the 2nd millennium BC by Mycenaean Greek...

). According to the mathematician and physician Mark Ridley

Mark Ridley (physician)

Dr. Mark Ridley was an English physician, born in Stretham, Cambridgeshire, to Lancelot Ridley. He became physician to the English merchant in Russia, and then personal physician to the Tsar of Russia. While there, ca. 1594-1599, he compiled a Russian-English, English-Russian dictionary, which is...

, chapter 12 of book 4 of De Magnete, which explained how astronomical observations

Observational astronomy

Observational astronomy is a division of the astronomical science that is concerned with getting data, in contrast with theoretical astrophysics which is mainly concerned with finding out the measurable implications of physical models...

could be used to determine the magnetic variation

Magnetic declination

Magnetic declination is the angle between magnetic north and true north. The declination is positive when the magnetic north is east of true north. The term magnetic variation is a synonym, and is more often used in navigation...

, was actually Wright's work.

Gilbert had invented a dip-compass

Dip circle

Dip circles are used to measure the angle between the horizon and the Earth's magnetic field . They were used in surveying, mining and prospecting as well as for the demonstration and study of magnetism....

and compiled a table recording the dip

Magnetic dip

Magnetic dip or magnetic inclination is the angle made by a compass needle with the horizontal at any point on the Earth's surface. Positive values of inclination indicate that the field is pointing downward, into the Earth, at the point of measurement...

of the needle below the horizon. Wright believed that this device would prove to be extremely useful in determining latitude and, with the help of Blundeville and Briggs, wrote a small pamphlet called The Making, Description and Use of the Two Instruments for Sea-men to find out the Latitude ... First Invented by Dr. Gilbert. It was published in 1602 in Blundeville's book The Theoriques of the Seuen Planets. That same year he authored The Description and Use of the Sphære (not published till 1613), and in 1605 published a new edition of the widely used work The Safegarde of Saylers.

Surveying

Surveying

See Also: Public Land Survey SystemSurveying or land surveying is the technique, profession, and science of accurately determining the terrestrial or three-dimensional position of points and the distances and angles between them...

on land. He prepared "a plat

Plat

A plat in the U.S. is a map, drawn to scale, showing the divisions of a piece of land. Other English-speaking countries generally call such documents a cadastral map or plan....

of part of the waye whereby a newe River may be brought from Uxbridge

Uxbridge

Uxbridge is a large town located in north west London, England and is the administrative headquarters of the London Borough of Hillingdon. It forms part of the ceremonial county of Greater London. It is located west-northwest of Charing Cross and is one of the major metropolitan centres...

to St. James

St. James's

St James's is an area of central London in the City of Westminster. It is bounded to the north by Piccadilly, to the west by Green Park, to the south by The Mall and St. James's Park and to the east by The Haymarket.-History:...

, Whitehall

Whitehall

Whitehall is a road in Westminster, in London, England. It is the main artery running north from Parliament Square, towards Charing Cross at the southern end of Trafalgar Square...

, Westminster

Westminster

Westminster is an area of central London, within the City of Westminster, England. It lies on the north bank of the River Thames, southwest of the City of London and southwest of Charing Cross...

[,] the Strand

Strand, London

Strand is a street in the City of Westminster, London, England. The street is just over three-quarters of a mile long. It currently starts at Trafalgar Square and runs east to join Fleet Street at Temple Bar, which marks the boundary of the City of London at this point, though its historical length...

, St Giles

St Giles, London

St Giles is a district of London, England. It is the location of the church of St Giles in the Fields, the Phoenix Garden and St Giles Circus. It is located at the southern tip of the London Borough of Camden and is part of the Midtown business improvement district.The combined parishes of St...

, Holbourne

Holborn

Holborn is an area of Central London. Holborn is also the name of the area's principal east-west street, running as High Holborn from St Giles's High Street to Gray's Inn Road and then on to Holborn Viaduct...

and London", However, according to a 1615 paper in Latin in the annals of Gonville and Caius College, he was prevented from bringing this plan to fruition "by the tricks of others". Nonetheless, early in the first decade of the 17th century, he was appointed by Sir Hugh Myddelton as surveyor to the New River

New River (England)

The New River is an artificial waterway in England, opened in 1613 to supply London with fresh drinking water taken from the River Lea and from Amwell Springs , and other springs and wells along its course....

project, which successfully directed the course of a new man-made channel to bring clean water from Chadwell Spring at Ware, Hertfordshire

Hertfordshire

Hertfordshire is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in the East region of England. The county town is Hertford.The county is one of the Home Counties and lies inland, bordered by Greater London , Buckinghamshire , Bedfordshire , Cambridgeshire and...

, to Islington

Islington

Islington is a neighbourhood in Greater London, England and forms the central district of the London Borough of Islington. It is a district of Inner London, spanning from Islington High Street to Highbury Fields, encompassing the area around the busy Upper Street...

, London. Although the distance in a straight line from Ware to London is only slightly more than 20 miles (32.2 km), the project required a high degree of surveying skill on Wright's part as it was necessary for the river to take a route of over 40 miles following the 100 feet (30.5 m) contour line

Contour line

A contour line of a function of two variables is a curve along which the function has a constant value. In cartography, a contour line joins points of equal elevation above a given level, such as mean sea level...

on the west side of the Lea Valley

Lea Valley

The Lea Valley, the valley of the River Lea, has been used as a transport corridor, a source of sand and gravel, an industrial area, a water supply for London, and a recreational area...

. As the technology of the time did not extend to large pumps or pipes, the water flow had to depend on gravity through canals or aqueduct

Aqueduct

An aqueduct is a water supply or navigable channel constructed to convey water. In modern engineering, the term is used for any system of pipes, ditches, canals, tunnels, and other structures used for this purpose....

s over an average fall of 5.5 inches a mile (approximately 8.7 centimetres per kilometre).

Work on the New River started in 1608 – the date of a monument at Chadwell Spring – but halted near Wormley, Hertfordshire, in 1610. The stoppage has been attributed to factors such as Myddelton facing difficulties in raising funds, and landowners along the route opposing the acquisition of their lands on the ground that the river would turn their meadows into "bogs and quagmires". Although the landowners petitioned Parliament

Parliament of England

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England. In 1066, William of Normandy introduced a feudal system, by which he sought the advice of a council of tenants-in-chief and ecclesiastics before making laws...

, they did not succeed in having the legislation authorizing the project repealed prior to Parliament being dissolved in 1611; the work resumed later that year. The New River was officially opened on 29 September 1613 by the Lord Mayor of London, Sir John Swinnerton, at the Round Pond, New River Head, in Islington. It still supplies the capital with water today.

Other mathematical work

For some time Wright had urged that a navigation lectureship be instituted for merchant seamen, and he persuaded Admiral Sir William Monson, who had been on Cumberland's Azores expedition of 1589, to encourage a stipendStipend

A stipend is a form of salary, such as for an internship or apprenticeship. It is often distinct from a wage or a salary because it does not necessarily represent payment for work performed, instead it represents a payment that enables somebody to be exempt partly or wholly from waged or salaried...

to be paid for this. At the beginning of the 17th century, Wright succeeded Thomas Hood

Thomas Hood (mathematician)

Thomas Hood was an English mathematician and physician, the first lecturer in mathematics appointed in England, a few years before the founding of Gresham College. He publicized the Copernican theory, and discussed the nova SN 1572....

as a mathematics lecturer under the patronage of the wealthy merchants Sir Thomas Smyth and Sir John Wolstenholme; the lectures were held in Smyth's house in Philpot Lane. By 1612 or 1614 the East India Company had taken on sponsorship of these lectures for an annual fee of £

Pound sterling

The pound sterling , commonly called the pound, is the official currency of the United Kingdom, its Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands, British Antarctic Territory and Tristan da Cunha. It is subdivided into 100 pence...

50 (about £6,500 as of 2007). Wright was also mathematics tutor to the son of James I

James I of England

James VI and I was King of Scots as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the English and Scottish crowns on 24 March 1603...

, the heir apparent

Heir apparent

An heir apparent or heiress apparent is a person who is first in line of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting, except by a change in the rules of succession....

Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales

Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales

Henry Frederick Stuart, Prince of Wales was the elder son of King James I & VI and Anne of Denmark. His name derives from his grandfathers: Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley and Frederick II of Denmark. Prince Henry was widely seen as a bright and promising heir to his father's throne...

, from 1608 or 1609 until the latter's death at the age of 18 on 6 November 1612. Wright was described as "a very poor man" in the Prince's will and left the sum of £30 8s

Shilling (United Kingdom)

The British shilling is an historic British coin from the eras of the Kingdom of Great Britain and the later United Kingdom; also adopted as a Scot denomination upon the 1707 Treaty of Union....

(about £4,300 in 2007). To the Prince, who was greatly interested in the science of navigation, Wright dedicated the second edition of Certaine Errors (1610) and the world map published therein. He also drew various maps for him, including a "sea chart of the N.-W. Passage

Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage is a sea route through the Arctic Ocean, along the northern coast of North America via waterways amidst the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans...