Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant

Encyclopedia

The Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant

began during the turbulent Reconstruction period following the American Civil War

. Grant was elected

the 18th President of the United States in 1868 and was re-elected

to the office in 1872, serving from March 4, 1869, to March 4, 1877. The United States was at peace with the world throughout the era, and was prosperous until the Panic of 1873

, that predominated Grant's second term in office. Grant was a Republican, and his main supporters were the Radical and Stalwart Republican factions. President Grant bolstered the Executive Branch's enforcement powers by signing into law the Department of Justice and Office of Solicitor General. President Grant supported Civil War values that included "union, freedom and equality." He was opposed by the Liberal faction of the party, many of them founding fathers of the GOP, who denounced Grant's patronage

. The Liberals insisted that Reconstruction had been successful and that Army troops should be withdrawn from the South so it could regain its normal political status. The Liberals nominated a candidate in 1872, who was supported by the Democrats, but was decisively defeated by Grant. President Grant was a loner who never developed a cadre of trustworthy political advisers; he relied heavily on former Army associates who had a thin understanding of politics and a weak sense of civilian ethics. His presidential reputation was severely damaged by repeated scandals and frauds.

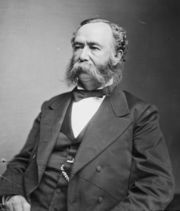

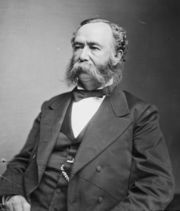

Characteristically, Grant lacked discernment and good judgment when it came to appointing honest men. His Secretary of War, his personal secretary, and high officials he named to the Treasury and Navy departments joined bribery or tax-cheating schemes. Instead of exposing the culprits, Grant defended them and attacked the accusers. Middle-class public opinion, a key element in the Republican Party base, turned hostile to Grant. At various times capable appointments were made by Grant; honest men who desired to save Grant and the nation from scandal. After a false start with weak selections, Grant named to his Cabinet

leading reformers including Hamilton Fish

, Benjamin Bristow

, Alphonso Taft

, and Amos T. Akerman

. Fish, as Secretary of State, negotiated the Treaty of Washington

and was successful at keeping the United States out of trouble with Britain and Spain. Bristow, as Secretary of Treasury, ended the corruption of the Whiskey Ring

where distillers and corrupt officials made millions from tax evasion. Taft, a brilliant jurist as Attorney General, successfully negotiated for bipartisan panel to peacefully settle the controversial Election of 1876. Grant and Attorney General Akerman enforced civil rights

legislation that protected African Americans and destroyed the Ku Klux Klan

. Grant encouraged peaceful Congressional negotiations after the controversial Election of 1876; signed the Electorial Commission Act of 1877

; while the Compromise of 1877

ended Reconstruction.

Economically, Grant favored a hard-money, gold-based, anti-inflationary policy that entailed paying off the large national debt with gold. He reduced governmental spending, decreased the federal work force, and reduced the national debt, while tax revenues increased in the Treasury Department. During his second term in office, the Panic of 1873

, caused by rampant railroad speculation, shook the nation's financial institutions; banks failed, prices fell, and unemployment surged. Before the Panic there had been eight years of tremendous industrial growth after the Civil War

that fueled lavish money making schemes, personal greed, and national corruption. President Grant's contraction of money supply worsened the panic; the ensuing major U.S. depression that followed lasted for five years causing massive economic damage to the country. The Panic wiped out both the fortunes of business and corruption. Southern Reconstruction continued that included escalated sectional violence over the status of freedmen and fractured state party alliances and elections.

With the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad

in 1869, the West was wide open to expansionism that sometimes was challenged by hostile Native Americans

. Grant implemented an innovative peace policy, though not always successful, with Native Americans. Hostilities took place with the Modoc War

, the Red River War

, and the Great Sioux War

that culminated with the famous Battle of Little Bighorn where Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer

was killed. In 1874, millions of buffalo were being slaughtered to make room for settlers and ranchers. Grant, who favored ranchers land use for domestic cattle, rejected legislation that would have limited the slaughter of the bison. After the fatal Modoc

peace commission in 1873, Grant's Native American policy incorporated the military strategies favored by William T. Sherman and Phil Sheridan. Corruption was rampant in the Department of Indian Affairs under Secretary of Interior Columbus Delano

. Grant's reputation as President by historians has traditionally ranked low, however, he has recently received higher ratings for his enforcement of African Americans civil rights in the South. Historians ranked high Grant's Secretary of State Hamilton Fish for settling the Alabama Claims

and coolly handling the Virginius Affair

.

civil rights. He leaned heavily toward the Radical camp and often sided with their Reconstruction policies, signing into law Force Acts to prosecute the Ku Klux Klan

. In foreign policy Grant won praise for the Treaty of Washington, settling the Alabama Claims

issue with Britain through arbitration. Economically he sided with Eastern bankers and signed the Public Credit Act that paid U.S. debts in gold specie, but was blamed for the severe economic depression that lasted 1873–1877. Grant, wary of powerful congressional leaders, was the first President to ask for a line item veto.

In the century after he left office most historians denounced the Reconstruction policies followed by Grant. More recently, Grant's support for and enforcement of African Americans civil rights has earned him praise from scholars. While graft and corruption existed in the Southern state governments he supported with the Army, many civil rights advances were made for African Americans. He was vigorous in his enforcement of the 14th and 15th amendments and prosecuted thousands of persons who violated African American civil rights; he used military force to put down political insurrections in Louisiana

, Mississippi

, and South Carolina

.

As President, Grant failed to establish and enforce ethical standards with his cabinet and appointees. He failed to take measures to lessen the effects of the Panic of 1873

and the economic depression that ensued. The depression of 1873, along with the increasingly unpopular Reconstruction program, weakened his reputation and his party, allowing the resurgent Democrats to gain a majority in the House of Representatives in 1875. His Presidency was inundated with many scandals caused by low standards and carelessness with his political appointees and personal associates. Often through flattery, these corrupt associates used Grant as a shield against prosecutors and reformers. Grant surrounded himself with people denounced by reformers as scoundrels, and he unwisely accepted gifts from rich friends who used their friendship for financial advantage. Nepotism

, practiced by Grant, was unrestrained with almost forty family members or relatives who financially benefited from government appointments or employment.

In 1872, Senator Charles Sumner

, the leader of civil rights forces in Congress, compared him to the despotic Julius Caesar

and labeled his presidency as "one man and his personal will" and that the office of the President was treated no more than a "play thing and perquisite". Grant and Sumner were often at odds with each other on matters of foreign policy and political patronage. Sumner followed his own foreign policy and detested Grant's practice of nepotism

in making political appointments. One historian, Mary L. Hinsdale, described the Grant Administration as "a most extraordinary array of departures from the normal course" and a "military" rule, in close connection with a select Republican Senatorial group. In an unsuccessful effort to annex the island country of Santo Domingo, Grant completely bypassed the State Department by sending his military associate Orville E. Babcock to produce the treaty. Grant blatantly disregarded the public opinion of Attorney General

Ebenezer R. Hoar

over the McGarrahan mining claim patents.

Public policies were a burden and at times perplexing to Grant, and he often delegated unprecedented authority to others. Grant's foreign policy was heavily influenced by the able Secretary of State Hamilton Fish

. Grant depended on Fish's advice on domestic issues such as money policy and Reconstruction. His Secretary of Treasury, George Boutwell, was given full charge of national economic policies. In 1874, Grant began a series of appointments that included reformers and qualified statesmen to his Administration, starting with Benjamin Bristow

who prosecuted the Whiskey Ring

. With the departure of Orville E. Babcock and William W. Belknap

from the White House in 1876, the Grant Administration took on a civilian rather than "military" style.

There were two main divisive issues in 1868. The first was the continued Reconstruction of the South. The Democrats advocated allowing former Confederate soldiers to hold elective offices, and the Republicans endorsed the Fifteenth Amendment

There were two main divisive issues in 1868. The first was the continued Reconstruction of the South. The Democrats advocated allowing former Confederate soldiers to hold elective offices, and the Republicans endorsed the Fifteenth Amendment

to the Constitution which allowed African Americans to vote. The other controversial issue concerned the redemption of war bonds either in gold or paper money known as greenback

s. The Democrats wanted to redeem the bonds with $100,000,000 in greenbacks and the rest with gold. The greenbacks were known as "cheap money" and would be inflationary. The Republicans wanted to pay the redemption of war bonds only with gold, a position attractive to investors and bankers.

Finding a popular hero who endorsed their Reconstruction policies, the Republicans nominated Grant and Speaker of the House Schuyler Colfax

. The Democrats, ignoring politically damaged President Andrew Johnson

(who was a political independent), nominated Horatio Seymour

– former governor of New York – and Francis P. Blair

from Missouri. Seymour was a wealthy conservative who came under GOP attack for weakness during the war and favoring the anti-war Copperheads

. The campaigning was nasty, as the Republicans waved the "bloody shirt" of treason against the Democrats-as-Copperheads. Grant himself never campaigned, except for his slogan "Let us have peace" and his apology to Jewish voters for his 1862 General Order No. 11 that banned Jewish merchants from his zone during the Civil War because of alleged profiteering. Grant won with 52.7% of the popular vote and won by a landslide in the Electoral College with 214 votes to Seymour's 80 votes. Grant was helped by the fact that six southern states were controlled by Radical Republicans who kept many ex-Confederates from voting.

, the nation was in a mood for reform. Rather than choosing his cabinet by consulting with key Senators such as Charles Sumner

, Grant chose his cabinet independently. Except for John A. J. Creswell, not one of Grant's choices would have been chosen by the Senate. Although the Senate was shocked by his appointments they were all unanimously ratified; the public rejoiced claiming that Grant had "cut himself loose from a set of party hacks". Senator Charles Sumner, Chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and leading Radical in the Senate, however, was no party hack and was insulted at not being offered a cabinet position or being consulted. When it was found out that A.T. Stewart, a wealthy New York businessman, would be Secretary of Treasury, Sumner blocked an exception to a Senate rule that stated a nominee could not own a business and be head of the Treasury. This example of Sumner's power in the Senate was only a first of clashes with President Grant. George S. Boutwell

, a Radical, was nominated by Grant and confirmed by the Senate as Secretary of Treasury. Some of Grant's cabinet members did not even know their names were offered to the Senate for confirmation. Grant's independent secretive manner in choosing his muddled cabinet, however, created animosity with many in Congress.

in making government office appointments. The controversial law had been invoked during the impeachment trial of Johnson in 1868. On March 5, 1869, a bill was brought before Congress to repeal the act, but Senator Charles Sumner

was opposed, unwilling to give Grant a free hand in making appointments. Grant, to bolster the repeal effort, declined to make any new appointments except for vacancies, until the law was overturned, thus, agitating political office seekers to pressure Congress to repeal the law. Under national pressure for governmental reform, a compromise was reached and a new bill was passed that allowed the President to have complete control over removing his own cabinet, however, government appointees needed the approval of Congress within a thirty day period. Grant, who did not desire a party split over the matter, signed the bill; afterwards, he received criticism for not getting a full repeal of the law. The unpopular measure was completely repealed in 1887. Grant was criticized for appointing many family members considered unqualified to highly sought government posts, a practice known as nepotism

.

and Henry Adams

became critical and discouraged over Grant's Presidency in the aftermath of the Black Friday

scandal. By 1870, Horace Greeley

lost enthusiasm for the Administration with the resignations of Attorney General Ebenezer R. Hoar

and Ambassador to Britain John L. Motley

. Prominent journalists Samuel Bowles

, Horace White, E. L. Godkin, and William C. Bryant

became concerned over alleged incompetence and lack of national direction from Grant. Personal animosity remained between Charles Sumner

and Grant over the Senate

rejection of the Santo Domingo Treaty. The common citizen, however, revered Grant for his gallant service in the Civil War

.

During Reconstruction, Freedmen (freed slaves), were given the vote by Congress and became active in state politics; fourteen were elected to Congress. In state government they were never governor but did become lieutenant governors or secretaries of state. They formed the voting base of the Republican party along with some local whites (called "Scalawags") and new arrivals from the North (called "Carpetbaggers".) Most Southern whites opposed the Republicans; they called themselves "Conservatives" or "Redeemers

During Reconstruction, Freedmen (freed slaves), were given the vote by Congress and became active in state politics; fourteen were elected to Congress. In state government they were never governor but did become lieutenant governors or secretaries of state. They formed the voting base of the Republican party along with some local whites (called "Scalawags") and new arrivals from the North (called "Carpetbaggers".) Most Southern whites opposed the Republicans; they called themselves "Conservatives" or "Redeemers

". Grant repeatedly took a role in state affairs; for example on December 24, 1869, he established federal military rule in Georgia and restored black legislators who had been expelled from the state legislature.

, Grant and many in the north believed the American Civil War

extended democracy to the African American

freedmen. Grant used political pressure to ensure the states ratified the Fifteenth Amendment

, guaranteeing that "no citizen can be denied the right to vote based upon race, color, or previous condition of servitude". When it passed he hailed it as "a measure of grander importance than any other one act of the kind from the foundation of our free government to the present day". Many in the south, however, were determined that the African American males' right to vote would be unenforcable.

and to aid the Attorney General, the Office of Solicitor General

. Grant appointed Amos T. Akerman

as Attorney General and Benjamin H. Bristow as America's first Solicitor General. Both Akerman and Bristow used the Department of Justice to vigorously prosecute Ku Klux Klan

members in the early 1870s. In the first few years of Grant's first term in office there were 1000 indictments against Klan members with over 550 convictions from the Department of Justice. By 1871, there were 3000 indictments and 600 convictions with most only serving brief sentences while the ringleaders were imprisoned for up to five years in the federal penitentiary in Albany, New York

. The result was a dramatic decrease in violence in the South. Akerman gave credit to Grant and told a friend that no one was "better" or "stronger" then Grant when it came to prosecuting terrorists.

that allowed persons of African descent to become citizens of the United States. This revised an earlier law, the Naturalization Act of 1790

that only allowed white persons of good moral character to become U.S. citizens. The law also prosecuted persons who used fictitious names, misrepresentations, or identities of deceased individuals when applying for citizenship.

from attacking or threatening African Americans. This act placed severe penalties on persons who used intimidation, bribery, or physical assault to prevent citizens from voting and placed elections under Federal jurisdiction.

On January 13, 1871 President Grant submitted to Congress a report on violent acts committed by the Ku Klux Klan

in the South. On March 20, President Grant personally took the lead and told a reluctant Congress the situation in the South was dire and federal legislation was needed that would effectively "secure life, liberty, and property, and the enforcement of law, in all parts of the United States." President Grant stated that the U.S. mail and the collection of revenue was in jeopardy. Congress investigated the Klan's activities and eventually passed the Force Act of 1871 to allow prosecution of the Klan. This Act, also known as the "Ku Klux Klan Act" and written by Representative Benjamin Butler

, was passed by Congress to specifically go after local units of the Ku Klux Klan. Grant was initially reluctant to sign the bill, being wary of charges that his administration was a military dictatorship. Grant signed the bill into law on April 20, 1871 after being convinced by Secretary of Treasury, George Boutwell, that federal protection was warranted, having cited documented atrocities against the Freedmen. This law allowed the President to suspend habeas corpus

on "armed combinations" and conspiracies by the Klan. The Act also empowered the president "to arrest and break up disguised night marauders". The actions of the Klan were defined as high crimes and acts of rebellion against the United States.

The Ku Klux Klan consisted of local secret organizations formed to violently oppose Republican rule during Reconstruction; there was no organization above the local level. Wearing white hoods to hide their identity the Klan would violently attack and threaten Republicans. The Klan was strong in South Carolina between 1868 and 1870; South Carolina Governor Robert K. Scott, who was mired in corruption charges, allowed the Klan to rise to power. Grant, who was fed up with their violent tactics, ordered the Ku Klux Klan to disperse from South Carolina and lay down their arms under the authority of the Enforcement Acts on October 12, 1871. There was no response, and so on October 17, 1871, Grant issued a suspension of habeas corpus in all the 9 counties in South Carolina. Grant ordered federal troops in the state who then captured and vigorously prosecuted the Klan. With the Klan destroyed other white supremacist groups would emerge, including the White League

and the Red Shirts.

was readmitted into the Union on March, 30, 1870, Mississippi

was readmitted February 23, 1870, and Virginia

on January 26, 1870. Georgia

became the last Confederate state to be readmitted into the Union on July 15, 1870. All members for the House of Representatives and Senate were seated from the 10 Confederate states who seceded. Technically, the United States was again a united country.

To ease tensions, Grant signed the Amnesty Act of 1872 on May 23, 1872 that gave amnesty to former Confederates. This act allowed most former Confederates, who before the war had taken an oath to uphold the Constitution of the United States, to hold elected public office. Only 500 former Confederates remained unpardoned and therefore forbidden to hold elected public office.

Grant's 1868 campaign slogan, "Let us have peace," defined his policy toward reconstructing the South and opening a new era in relations with the western Indian tribes. The goal of his "peace policy" was to minimize military conflict with the Indians, looking forward to "any course toward them which tends to their civilization and ultimate citizenship". It was a sharp reversal of federal policy toward Native Americans

Grant's 1868 campaign slogan, "Let us have peace," defined his policy toward reconstructing the South and opening a new era in relations with the western Indian tribes. The goal of his "peace policy" was to minimize military conflict with the Indians, looking forward to "any course toward them which tends to their civilization and ultimate citizenship". It was a sharp reversal of federal policy toward Native Americans

. "Wars of extermination ... are demoralizing and wicked.", he told Congress four years later in his second Inaugural Address on March 4, 1873. The president lobbied, though not always successfully, to preserve Native American lands from encroachment by the westward advance of pioneers. The economic forces of western expansionism led to conflicts between Native Americans, settlers, and the U.S. military. Native Americans were increasingly forced to live on reservations

. Statistical data of the number of Indian wars per year between 1850 and 1890, revealed that battles decreased during Grant's two terms in office from 101 in 1869 to 43 in 1877. In 1875 there were only 15 Indian battles, the lowest rate since 1853 at 13 battles.

In 1869, Grant appointed his aide General Ely S. Parker

(Seneca) as the first Native American Commissioner of Indian Affairs. During Parker's first year in office, the number of Indian Wars per year dropped by 43 from 101 to 58. Chief of the Oglala Sioux Red Cloud

wanted to meet President Grant, after learning that Parker was appointed Indian Commissioner. Red Cloud, along with chief of the Brulé Sioux Spotted Tail

, came to Washington, D.C. by train and met with Parker and President Grant in 1870. Grant held no personal animosity towards Native Americans and personally treated them with dignity. When Red Cloud

and Spotted Tail

first met Grant at the White House on May 7, 1870, they were given a bountiful dinner and entertainment equal to what was shown to a young Prince Arthur

at a White House visit from Britain in 1869. At their second meeting on May 8, Red Cloud informed Grant that Whites were trespassing on Native American lands and that his people needed food and clothing. Out of concern for Native Americans, Grant ordered all Generals in the West to "keep intruders off by military force if necessary". To prevent Native American

hostilities and wars, Grant lobbied for and signed the Indians Appropriations Act of 1870–1871. This act ended the governmental policy of treating tribes as independent sovereign nations. Native Americans would be treated as individuals or wards of the state and Indian policies would be legislated by Congressional statues.

The historian David Sim (2008) examined the peace policy, emphasizing incoherence in its formulation and implementation. Historians have debated issues of "paternalism" and "colonialism" but have glossed over the significance of contingencies, inconsistencies, and political competition involved in forging a substantive federal policy. While the Grant administration focused on well-meaning but limited goals of placing "good men" in positions of influence and convincing native peoples of their fundamental dependency on the US government, attempts to create a new departure in federal-native relations were characterized by conflict and disagreement. The muddled creation of what has become known as the peace policy thus tells much about the varied and divergent attitudes Americans had toward the consolidation of their empire in the West following the Civil War.

The innovation in Grant's Native American

peace policy was in appointing Quaker or Christians as US Indian agents to various posts throughout the nation. This destroyed the power of patronage, as Congress would be reluctant to go after church appointments. On April 10, 1869, Congress created the Board of Indian Commissioners. Grant appointed volunteer members who were "eminent for their intelligence and philanthropy"; a previous commission had been set up under the Andrew Johnson Administration in 1868. The Grant Board was given extensive power to supervise the Bureau of Indian Affairs

and "civilize" Native Americans. After the Piegan

Massacre on January 23, 1870, when Major Edward M. Baker killed 173 tribal members, mostly women and children, Grant was determined to divide Native American post appointments "up among the religious churches"; by 1872, 73 Indian agencies were divided among religious denominations. Quaker or other clergy officials predominately controlled most of the central and southern Plains Indian territories

, while all other surrounding territories were under the control of appointed military officers.

The historian Robert M. Utley

The historian Robert M. Utley

(1984) contended that Grant, as a pragmatist, saw no inconsistencies with dividing up Native American posts among religious leaders and military officers. He added that Grant's "Quaker Policy", despite having good intentions, failed to solve the real dilemma of the misunderstandings between "the motivations, purposes, and ways of thinking" between both White and Native American cultures. These inconsistencies were evident in the breakdown of peace negotiations between the U.S. military and the Modoc tribal leaders during the Modoc War

from 1872 to 1873.

In 1871, President Grant's Indian peace policy, enforced and coordinated by Brig. Gen. George Stoneman

in Arizona, required the Apache

to be put on reservations where they would receive supplies and agriculture education. The Apache slipped out and occasionally raided white settlers. In one raid, believed to be done by Apache warriors, settlers and mail runners were murdered near Tuscan, Arizona. The townspeople traced this raid to Apache reservation from Camp Grant. 500 Apache lived at the Camp Grant near Dudleyville. Angered over the murders, the Tuscan townspeople hired 92 Papago

Indians, 42 Mexicans, and 6 whites to take revenge on the Apache. When the war party reached Camp Grant on April 30, they murdered 144 Apaches, mostly women and children. Twenty-seven captured Apache children were sold into Mexican slavery. In May, an attempt was made by a small federal military party to capture Apache leader Cochise

; during the chase they killed 13 Apache. Grant immediately removed Stoneman of his command in Arizona.

Most detrimental to Grant's Peace Policy was corruption in the Department of Interior and the Department of War

. Columbus Delano

, whose tenure as Secretary of Interior from 1870 to 1875 was a debacle; allowed fraud to rampantly spread into the Department of Indian Affairs. Corruption was the rule rather than the exception. Money intended to supply Native American tribes with food and clothing was skimmed off by corrupt Indian agents and clerks, often allied with traders. After newspapers exposed Delano's delinquency, Grant defended him rather than investigate the matter. The previous Grant appointment, Secretary Jacob D. Cox, had run the department with efficiency and merit. Cox had been considered to be one of the best secretaries of Interior in the nation's history. When Cox resigned in 1870, Grant appointed Delano out of patronage considerations to appease Stalwart party bosses. Grant's Secretary of War, William W. Belknap

, took extortion money from a Fort Sill

Indian trading post.

was not perfect. While he advocated that African Americans enter the West Point Academy, he failed in 1870 and 1871 to protect the first African American West Point Academy cadet, James Albert Smith, from racist hazing by other cadets. This lack of protection was influenced by Grant's son, then West Point cadet Frederick Dent Grant

, who participated in the hazing against Smith.

President Lincoln signed into law the Morrill bill

that outlawed polygamy

in all U.S. Territories. Mormons who practiced polygamy in Utah for the most part resisted the Morrill law and the territorial governor. During the 1868 election, Grant had mentioned he would enforce the law against polygamy. Tensions began as early as 1870, when Mormons in Ogden, Utah began to arm themselves and practice military drilling. By the Fourth of July, 1871 Mormon militia in Salt Lake City, Utah were on the verge of fighting territorial troops, however, leveler heads prevailed and violence was averted.

President Grant, however, who believed Utah was in a state of rebellion was determined to arrest those who practiced polygamy outlawed under the Morrill Act. In October, 1871 hundreds of Mormons were rounded up by U.S. marshals, put in a prison camp, arrested, and put on trial for polygamy. One convicted polygamist received a $500 fine and 3 years in prison under hard labor. On November 20, 1871 Mormon leader Brigham Young

, in ill health, had been charged with polygamy. Young's attorney stated that Young had no intention to flee the court. Other persons during the polygamy shut down were charged with murder or intent to kill. The Morrill Act, however, proved hard to enforce since proof of marriage was required for conviction. On December 4, 1871 President Grant stated that polygamists in Utah were "a remnant of barbarism, repugnant to civilization, to decency, and to the laws of the United States."

's Anthony Comstock

, easily secured passage of the Comstock Act which made it a federal crime to mail articles "for any indecent or immoral use". Grant signed the bill after he was assured that Comstock would personally enforce it. Comstock went on to become a special agent of the Post Office appointed by Secretary James Cresswell

. Comstock prosecuted pornographers, imprisoned abortionists, banned nude art, stopped the mailing of information about contraception, and tried to ban what he considered bad books.

who was appointed by Grant as New York Custom Collector stated that the examinations excluded and deterred unfit persons from getting employment positions. However, Congress, in no mood to reform itself, denied any long-term reform by refusing to enact the necessary legislation to make the changes permanent. Historians have traditionally been divided whether patronage, meaning appointments made without a merit system, should be labelled corruption.

The movement for Civil Service reform reflected two distinct objectives: to eliminate the corruption and inefficiencies in a non-professional bureaucracy, and to check the power of President Johnson. Although many reformers after the Election of 1868 looked to Grant to ram Civil Service legislation through Congress, he refused, saying: "Civil Service Reform rests entirely with Congress. If members will give up claiming patronage, that will be a step gained. But there is an immense amount of human nature in the members of Congress, and it is human nature to seek power and use it to help friends. You cannot call it corruption – it is a condition of our representative form of Government." Grant used patronage to build his party and help his friends. He instinctively protected those whom he thought were the victims of injustice or attacks by his enemies, even if they were guilty. Grant believed in loyalty with his friends, as one writer called it the "Chivalry of Friendship".

On May 19, 1869, Grant protected the wages of those working for the U.S. Government. In 1868, a law was passed that reduced the government working day to 8 hours; however, much of the law was later repealed that allowed day wages to also be reduced. To protect workers Grant signed an executive order that "no reduction shall be made in the wages" regardless of the reduction in hours for the government day workers.

Treasury Secretary George S. Boutwell

reorganized and reformed the United States Treasury by discharging unnecessary employees, started sweeping changes in Bureau of Printing and Engraving to protect the currency from counterfeiters

, and revitalized tax collections to hasten the collection of revenue. These changes soon led the Treasury to have a monthly surplus. By May 1869, Boutwell reduced the national debt by $12 million. By September the national debt was reduced by $50 million, which was achieved by selling the growing gold surplus at weekly auctions for greenbacks

and buying back wartime bonds with the currency. The New York Tribune

wanted the government to buy more bonds and greenbacks and the New York Times praised the Grant administration's debt policy.

The first two years of the Grant administration with George Boutwell at the Treasury helm expenditures had been reduced to $292 million in 1871 – down from $322 million in 1869. The cost of collecting taxes fell to 3.11% in 1871. Grant reduced the number of employees working in the government by 2,248 persons from 6,052 on March 1, 1869 to 3,804 on December 1, 1871. He had increased tax revenues by $108 million from 1869 to 1872. During his first administration the national debt fell from $2.5 billion to $2.2 billion.

In a rare case of preemptive reform during the Grant Administration, Brevet Major General Alfred Pleasonton

was dismissed for being unqualified to hold the position of Commissioner of Internal Revenue

. In 1870, Pleasonton, a Grant appointment, approved an unauthorized $60,000 tax refund and was associated with an alleged unscrupulous Connecticut firm. Treasury Secretary George Boutwell promptly stopped the refund and personally informed Grant that Pleasonton was incompetent to hold office. Refusing to resign on Boutwell's request, Pleasonton protested openly before Congress. President Grant removed Pleasonton before any potential scandal broke out.

had attempted to annex the Dominican Republic

and Santo Domingo, but the House of Representatives defeated two resolutions for the protection of the Dominican Republic and Santo Domingo and for the annexation of the Dominican Republic. In July, 1869 Grant sent Orville E. Babcock

and Rufus Ingalls

who negotiated a draft treaty with Dominican Republic President Buenaventura Báez

for the annexation of Santo Domingo to the United States and the sale of Samaná Bay

for $2 million. To keep the island nation and Báez secure in power, Grant ordered naval ships, unauthorized by Congress, to secure the island from invasion and internal insurrection. Báez signed an annexation treaty on November 19, 1869 offered by Babcock under federal State department authorization. Secretary Fish drew up a final draft of the proposal and offered $1.5 million to the Dominican national debt, the annexation of Santo Domingo

as an American state, the United States' acquisition of the rights for Samaná Bay

for 50 years with an annual $150,000 rental, and guaranteed protection from foreign intervention. On January 10, 1870 the Santo Domingo treaty was submitted to the Senate for ratification. Despite his support of the annexation, Grant made the mistakes of not informing Congress of the treaty or encouraging national acceptance and enthusiasm.

Not only did Grant believe that the island would be of use to the Navy tactically, particularly Samaná Bay

, but also he sought to use it as a bargaining chip. By providing a safe haven for the freedmen, he believed that the exodus of black labor would force Southern whites to realize the necessity of such a significant workforce and accept their civil rights. Grant believed the island country would increase exports and lower the trade deficit. He hoped that U.S. ownership of the island would urge Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Brazil to abandon slavery. On March 15, 1870, the Foreign Relations Committee, headed by Sen. Charles Sumner

, recommended against treaty passage. Sumner, the leading spokesman for African American civil rights, believed that annexation would be enormously expensive and involve the U.S. in an ongoing civil war, and would threaten the independence of Haiti and the West Indies, thereby blocking black political progress. On May 31, 1870 Grant went before Congress and urged passage of the Dominican annexation treaty. Strongly opposed to ratification, Sumner successfully led the opposition in the Senate. On June 30, 1870 the Santo Domingo annexation treaty failed to pass the Senate; 28 votes in favor of the treaty and 28 votes against. Grant's own cabinet was divided over the Santo Domingo annexation attempt, and Bancroft Davis

, assistant to Sec. Hamilton Fish, was secretly giving information to Sen. Sumner on state department negotiations.

Relying on his military instinct, President Grant fought back hard. Unable constitutionally to go directly after Sen. Sumner, Grant immediately removed Sumner's close and respected friend Ambassador, John Lothrop Motley

. With Grant's prodding in the Senate, Sumner was finally deposed from the Foreign Relations Committee. Grant reshaped his coalition, known as "New Radicals", working with enemies of Sumner such as Ben Butler

of Massachusetts, Roscoe Conkling

of New York, and Oliver P. Morton of Indiana, giving in to Fish's demands that Cuba rebels be rejected, and moving his Southern patronage from the radical blacks and carpetbaggers who were allied with Sumner to more moderate Republicans. This set the stage of the Liberal Republican revolt of 1872, when Sumner and his allies publicly denounced Grant and supported Horace Greeley

and the Liberal Republicans

. Biographer William McFeely stated that Grant's annexation of Santo Domingo plan was not unrealistic, since African Americans faced difficult racial oppression in the South.

A Congressional investigation in June, 1870 led by Senator Carl Schurz

revealed that Babcock and Ingalls both had land interests in the Bay of Samaná

that would increase in value if the Santo Domingo

treaty were ratified. U.S. Navy ships, with President Grant's authorization, had been sent to protect Báez from an invasion by a Dominican

rebel, Gregorio Luperón

, while the treaty negotiations were taking place. The investigation had initially been called to settle a dispute between an American businessman Davis Hatch against the United States government. Báez had imprisoned Hatch without trial for his opposition to the Báez government. Hatch had claimed that the United States had failed to protect him from imprisonment. The majority Congressional report dismissed Hatch's claim and exonerated both Babcock and Ingalls. The Hatch incident, however, kept certain Senators from being enthusiastic about ratifying the treaty.

negotiating. Grant and Fish wanted Cuban independence and to end slavery without U.S. military intervention or occupation. Fish, diligently and against popular pressure, was able to keep Grant from officially recognizing Cuban independence because it would have endangered negotiations with Britain over the Alabama Claims

. The Sickle's peace negotiations failed in Madrid, but Grant and Fish did not succumb to popular pressure for U.S. military involvement in the Cuban rebellion. Grant and Fish sent a message to Congress, written by Fish and signed by Grant. The message urged strict neutrality not to officially recognize the Cuban revolt, calming national fears.

to allow outside experts to settle disputes. Grant's able Secretary of State Hamilton Fish

had orchestrated many of the events leading up to the treaty. Previously, Secretary of State William H. Seward

during the Johnson administration first proposed an initial treaty concerning damages done to American merchants by three Confederate warships, CSS Florida

, CSS Alabama

, and CSS Shenandoah

built in Britain. These damages were collectively known as the Alabama Claims

. These ships had inflicted tremendous damage to U.S. merchant ships during the Civil War and Washington wanted the British to pay heavy damages, perhaps including turning over Canada.

On April 1869, the U.S. Senate overwhelmingly rejected a proposed treaty which paid too little and contained no admission of British guilt for prolonging the war. Senator Charles Sumner

On April 1869, the U.S. Senate overwhelmingly rejected a proposed treaty which paid too little and contained no admission of British guilt for prolonging the war. Senator Charles Sumner

spoke up before congress; publicly denounced Queen Victoria; demanded a huge reparation; and opened the possibility of Canada ceded to the United States as payment. The speech angered the British government, and talks had to be put off until matters cooled down. Negotiations for a new treaty began in January 1871 when Britain sent Sir John Rose to America to meet with Fish. A joint high commission was created on February 9, 1871 in Washington, consisting of representatives from both Britain and the United States. The commission created a treaty where an international Tribunal would settle the damage amounts; the British admitted regret, not fault, over the destructive actions of the Confederate war cruisers. Grant approved and signed the treaty on May 8, 1871; the Senate ratified the Treaty of Washington

on May 24, 1871.

The Tribunal met in Geneva, Switzerland. The U.S. was represented by Charles Francis Adams

, one of five international arbitrators, and was counseled by William M. Evarts

, Caleb Cushing

, and Morrison R. Waite. On August 25, 1872, the Tribunal awarded United States $15.5 million in gold; $1.9 million was awarded to Great Britain. Historian Amos Elwood Corning noted that the Treaty of Washington and arbitration "bequeathed to the world a priceless legacy". In addition to the $15.5 million arbitration award, the treaty resolved some disputes over borders and fishing rights. On October 21, 1872 William I, Emperor of Germany, settled a boundary dispute in favor of the United States.

A primary role of the United States Navy in the 19th century was to protect American commercial interests and open trade to Eastern markets, including Japan and China. Korea had excluded all foreign trade and, the U.S. sought a treaty dealing with shipwrecked sailors after the crew of a stranded American commercial ship was killed. The long-term goal for the Grant Administration was to open Korea to Western markets in the same way Commodore Matthew Perry had opened Japan in 1854 by a Naval display of military force. On May 30, 1871 Rear Admiral John Rodgers with a fleet of five ships, part of the Asiatic Squadron

A primary role of the United States Navy in the 19th century was to protect American commercial interests and open trade to Eastern markets, including Japan and China. Korea had excluded all foreign trade and, the U.S. sought a treaty dealing with shipwrecked sailors after the crew of a stranded American commercial ship was killed. The long-term goal for the Grant Administration was to open Korea to Western markets in the same way Commodore Matthew Perry had opened Japan in 1854 by a Naval display of military force. On May 30, 1871 Rear Admiral John Rodgers with a fleet of five ships, part of the Asiatic Squadron

, arrived at the mouth of the Salee River below Seoul

. The fleet included the , one of the largest ships in the Navy with 47 guns, 47 officers, and a 571-man crew. While waiting for senior Korean officials to negotiate, Rogers sent ships out to make soundings of the Salee River for navigational purposes.

The American fleet was fired upon by a Korean fort, but there was little damage. Rogers gave the Korean government ten days to apologize or begin talks, but the Royal Court kept silent. After ten days passed, on June 10, Rogers began a series of amphibious

assaults that destroyed 5 Korean forts. These military engagements were known as the Battle of Ganghwa

. Several hundred Korean soldiers and three Americans were killed. Korea still refused to negotiate, and the American fleet sailed away. The Koreans refer to this 1871 U.S. military action as Shinmiyangyo. President Grant defended Rogers in his third annual message to Congress in December, 1871. After a change in regimes in Seoul, in 1881, the U.S. negotiated a treaty – the first treaty between Korea and a Western nation.

in 1869 and the Whiskey Ring

in 1875. The Crédit Mobilier

is not a Grant scandal; its origins having been in 1864 during the Abraham Lincoln

Administration which carried over into the Andrew Johnson

Administration. The actual Crédit Mobilier scandal was exposed during the Grant Administration in 1872 as the result of political infighting between Congressman Oakes Ames and Congressman Henry S. McComb. Stocks owned by Ambassador to Britain Robert C. Schenck

in the fraudulent Emma Silver Mine is considered a Grant Administration embarrassment rather than a scandal.

Although Grant had many successes during the first term as President in the economy, civil rights, and foreign policy, scandals associated with the Administration were beginning to emerge publicly. Grant's inability to establish personal accountability among his subordinates and Cabinet members created an environment rife for scandals. Although Grant himself was not directly responsible for and did not profit from the corruption among subordinates, he was reluctant to believe friends could commit criminal activities. As a result, he failed to take any direct action and rarely reacted strongly after their guilt was established. Grant protected close friends with Presidential power and pardoned persons who were convicted in the Whiskey Ring scandal after serving only a few months in prison.

Grant's single-minded temperament would often lead to vigorous counterattacks when critics complained, as he was very protective and defensive of his subordinates. Grant was weak in his selection of subordinates, many times favoring military associates from the war over talented and experienced politicians. He alienated party leaders by giving many posts to his friends and political contributors rather than supporting the party's needs. His failure to establish working political alliances in Congress allowed the scandals to spin out of control. When his second term ended, Grant wrote to Congress that "Failures have been errors of judgment, not of intent". Nepotism was rampant; around 40 family relatives financially prospered while Grant was President.

and Jim Fisk

set up an elaborate scam to corner the gold market through buying up all the gold at the same time to drive up the price. The plan was to keep the Government from selling gold, thus driving its price. President Grant and Secretary of Treasury George S. Boutwell

found out about the gold market speculation and ordered the sale of $4 million in gold on (Black) Friday, September 23. Gould and Fisk were thwarted, and the price of gold dropped. The effects of releasing the gold by Boutwell were disastrous. Stock prices plunged and food prices dropped, devastating farmers for years.

and Southern regions of the United States. These were known as Star Routes

because an asterisk was given on official Post Office

documents. These remote routes were hundreds of miles long and went to the most rural parts of the United States by horse and buggy. In obtaining these highly prized postal contracts, an intricate ring of bribery and straw bidding was set up in the Postal Contract office; the ring consisted of contractors, postal clerks, and various intermediary brokers. Straw bidding was at its highest practice while John Creswell, Grant's 1869 appointment, was Postmaster-General

. An 1872 federal investigation into the matter exonerated Creswell, but he was censured

by the minority House report. A $40,000 bribe to the 42nd Congress

by one postal contractor had tainted the results of the investigation. In 1876, another congressional investigation under a Democratic House shut down the postal ring for a few years.

and Thomas Murphy. Private warehouses were taking imported goods from the docks and charging shippers storage fees. Grant's friend, George K. Leet, was allegedly involved with exorbitant pricing for storing goods and splitting the profits. Grant's third collector appointment, Chester A. Arthur

, implemented Secretary of Treasury George S. Boutwell

's reform to keep the goods protected on the docks rather than private storage.

Grant remained popular throughout the nation despite the scandals evident during his first term in office. Grant had supported a patronage system that allowed Republicans to infiltrate and control state governments. In response to President Grant's federal patronage, in 1870, Senator Carl Schurz

Grant remained popular throughout the nation despite the scandals evident during his first term in office. Grant had supported a patronage system that allowed Republicans to infiltrate and control state governments. In response to President Grant's federal patronage, in 1870, Senator Carl Schurz

from Missouri, a German immigrant and Civil War hero, started a second party known as the Liberal Republicans; they advocated civil service reform, a low tariff, and amnesty to former Confederate soldiers. The Liberal Republicans successfully ran B.G. Brown

for the governorship of Missouri and won with Democrat support. Then in 1872, the party completely split from the Republican party and nominated New York Tribune

editor Horace Greeley

as candidate for the Presidency. The Democrats, who at this time had no strong candidate choice of their own, reluctantly adopted Greeley as their candidate with Governor B.G. Brown as his running mate. Frederick Douglass

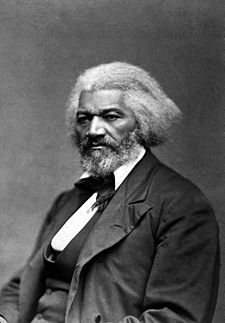

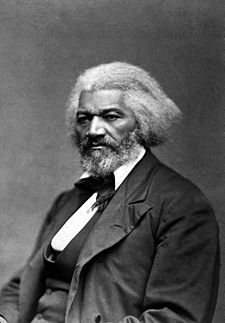

supported Grant and reminded black voters that Grant had destroyed the violent Ku Klux Klan

.

The Republicans, who were content with their Reconstruction program for the South, renominated Grant and Representative Henry Wilson

in 1872. Grant had remained a popular Civil War hero, and the Republicans continued to wave the "bloody shirt" as a patriotic symbol representing the North. The Republicans favored high tariffs and a continuation of Radical Reconstruction policies that supported five military districts in the Southern states. Grant also favored amnesty to former Confederate soldiers like the Liberal Republicans. Because of political infighting between Liberal Republicans and Democrats, the physically ailing Greeley was no match for the "Hero of Appomattox" and lost dismally in the popular vote. Grant swept 286 Electoral College votes while other minor candidates received only 63 votes. Grant won 55.8 percent of the popular vote between Greeley and the other minor candidates. Heartbroken after a hard fought political campaign, Greeley died a few weeks after the election and was able to receive only 3 electoral votes. Out of respect for Greeley, Grant attended his funeral.

operated openly and were better organized than the Ku Klux Klan. Their goals were to oust the Republicans, return Conservative whites to power, and use whatever illegal methods needed to achieve them. Being loyal to his veterans, Grant remained determined that African Americans would receive protection.

was a split state. In a controversial election two candidates were claiming victory as governor. Violence was used to intimidate black Republicans. The fusionist party of Liberal Republicans and Democrats claimed John McEnery as the victor, while the Republicans claimed U.S. Senator William P. Kellogg

. Two months later each candidate was sworn in as governor on January 13, 1863. A federal judge ordered that Kellogg was the rightful winner of the election and ordered him and the Republican based majority to be seated. The White League supported McHenry and prepared to use military force to remove Kellogg from office. Grant ordered troops to enforce the court order and protect Kellogg. On March 4, Federal troops under a flag of truce and Kellogg's state militia defeated McHenry's fusionist party's insurrection.

A dispute arose over who would be installed as judge and sheriff at the Colfax

A dispute arose over who would be installed as judge and sheriff at the Colfax

courthouse in Grant Parish, Louisiana

Kellogg's two appointments had seized control of the Court House on March 25 with aid and protection of Black state militia troops. Then on April 13, White League forces attacked the courthouse and massacred 50 black militiamen who had been captured. A total of 105 blacks were killed trying to defend the Colfax courthouse for Governor Kellogg. On April 21, Grant sent in the U.S. 19th Infantry Regiment

to restore order. On May 22, Grant issued a new proclamation to restore order in Louisiana. On May 31, McHenry finally told his followers to obey "peremptory orders" of the President. The orders brought a brief peace to New Orleans and most of Louisiana, ironically, except Grant Parish.

and Joseph Brooks

. Massive fraud characterized the election, but Baxter was declared the winner and took office. Brooks never gave up, and finally in 1874 a local judge ruled Brooks was entitled to the office and swore him in. Both sides mobilized militia units, and rioting and fighting bloodied the streets. There was anticipation who President Grant would side with – either Baxter or Brooks. Grant delayed, requesting a joint session of the Arkansas government to figure out peacefully who would be the Governor, but Baxter refused to participate. Then, on May 15, 1874, President Grant issued a Proclamation that Baxter was the legitimate Governor of Arkansas, and the hostilities ceased. In fall of 1874 the people of Arkansas voted out Baxter, and all the Republicans and the Redeemers

came to power. A few months later in early 1875, Grant astonished the nation by reversing himself and announcing that Brooks had been legitimately elected back in 1872. Grant did not send in troops, and Brooks never regained office; instead Grant gave him the high-paying patronage job of postmaster in Little Rock. Brooks died in 1877. The episode brought further discredit to Grant.

city government elected a White reform party consisting of Republicans and Democrats. This was done initially to lower city spending and taxes. Despite their early intentions, the reform movement turned racist when the new White city officials went after the county government comprised with a majority of African Americans. Rather than using legal means, the White League threatened the life of and expelled Crosby, the black county sheriff and tax collector. Crosby then went to Governor Adelbert Ames

to seek help to regain his position as sheriff. Governor Ames told him to take other African Americans and use force to retain his lawful position as Sheriff of Warren County

. At that time Vicksburg had a population of 12,443, over half of whom were African American.

On December 7, 1874, Crosby and an African American militia approached the city. He had declared that the Whites were, "ruffians, barbarians, and political banditti". A series of battles occurred that resulted in 29 African Americans and 2 Whites killed. The White militia retained control of the Court House and jail. On December 21, Grant gave a Presidential Proclamation for the people in Vicksburg to stop fighting. Philip Sheridan

in Louisiana dispatched troops who reinstated Crosby as sheriff and restored the peace. When questioned about the matter, Governor Ames denied he had told Crosby to use African American militia. On June 7, 1875, Crosby was shot to death by a White deputy while drinking in a bar. The origins for the shooting remained a mystery.

and Democratic militia took control of the state house at New Orleans, and the Republican Governor William P. Kellogg

was forced to flee. Former Confederate General James A. Longstreet

, with 3,000 African American

militia and 400 Metropolitan police, made a counter attack on the 8,000 White League troops. Consisting of former Confederate soldiers, the experienced White League troops routed Longstreet's army. On September 17, Grant sent in Federal troops, and they restored the government back to Kellogg. During the following controversial election in November, passions rose high, and violence mixed with fraud were rampant; the state of affairs in New Orleans was becoming out of control. The results were that 53 Republicans and 53 Democrats were elected with 5 remaining seats to be decided by the legislature.

Grant had been careful to watch the elections and secretly sent Phil Sheridan in to keep law and order in the state. Sheridan had arrived in New Orleans a few days before the January 4, 1875 legislature opening meeting. At the convention the Democrats again with military force took control of the state building out of Republican hands. Initially, the Democrats were protected by federal troops under Colonel Philip Régis de Trobriand, and the escaped Republicans were removed from the hallways of the state building. However, Governor Kellogg then requested that Trobriand reseat the Republicans. Trobriand returned to the State house and used bayonets to force the Democrats out of the building. The Republicans then organized their own house with their own speakers all being protected by the Federal Army. Sheridan, who had annexed the Department of the Gulf to his command at 9:00 P.M., claimed that the federal troops were being neutral since they had also protected the Democrats earlier.

During the election year of 1876, South Carolina was in a state of rebellion against Republican governor Daniel H. Chamberlain

During the election year of 1876, South Carolina was in a state of rebellion against Republican governor Daniel H. Chamberlain

. Conservatives were determined to win the election for ex-confederate Wade Hampton

through violence and intimidation. The Republicans went on to nominate Chamberlain for a second term. Hampton supporters, donning red shirts, disrupted Republican meetings with gun shootings and yelling. Tensions became violent on July 8, 1876 when five African Americans were murdered at Hamburg. The rifle clubs, wearing their Red Shirts, were better armed then the blacks. South Carolina was ruled by "mobocracy and bloodshed" than by Chamberlain's government.

Black militia did fight back in Charleston

on September 6, 1876 in what was known as the "King Street riot". The white militia assumed defensive positions out of concern over possible federal troop intervention. Then, on September 19, the Red Shirts took offensive action by openly killing 30 to 50 African Americans outside Ellenton

. During the massacre, state representative Simon Coker was killed. On October 7, Governor Chamberlain declared martial law and told all the "rifle club" members to put down their weapons. In the meantime, Wade Hampton never ceased to remind Chamberlain that he did not rule South Carolina. Out of desperation, Chamberlain wrote to President Grant and asked for federal intervention. The "Cainhoy riot" took place on October 15 when Republicans held a rally at "Brick Church" outside Cainhoy. Blacks and whites both opened fire; six whites and one black were killed. Grant, upset over the Ellenton and Cainhoy riots, finally declared a Presidential Proclamation on October 17, 1876 and ordered all persons, within 3 days, to cease their lawless activities and disperse to their homes. A total of 1,144 federal infantry were sent into South Carolina, and the violence stopped; election day was quiet. Both Hampton and Chamberlain claimed victory, and for a while both acted as governor; then Hampton took the office after President Rutherford B. Hayes

in 1877 withdrew federal troops and after Chamberlain left the state.

and the completion of the Northern Pacific Railway

, threatened to unravel Grant's peace policy, as white settlers encroached upon native land to mine for gold. Indian wars per year jumped up to 32 in 1876 and remained at 43 in 1877. One of the highest casualty Indian battles that took place in American history was at the Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876. Indian war casualties in Montana went from 5 in 1875, to 613 in 1876 and 436 in 1877.

, but Captain Jack killed him. Reverend Eleazar Thomas, a Methodist minister, was also killed. Alfred B. Meacham

, an Indian Agent, was severely wounded. The murders shocked the nation, and Sherman wired to have the Modocs exterminated. Grant overruled Sherman; Captain Jack was executed, and the remaining 155 Modocs were relocated to the Quapaw Agency in the Indian Territory

. This episode and the Great Sioux War undermined public confidence in Grant's peace policy, according to historian Robert M. Utley

.

, leader of the Comanche

, led 700 tribal warriors and attacked the buffalo hunter supply base on the Canadian River, at Adobe Walls, Texas

. The Army under General Phil Sheridan launched a military campaign, and, with few casualties on either side, forced the Indians back to their reservations by destroying their horses and winter food supplies. Grant, who agreed to the Army plan advocated by Generals William T. Sherman and Phil Sheridan, imprisoned 74 insurgents in Florida.

In 1872, around two thousand white buffalo hunters between Arkansas

and Witchita were killing buffalo

for their hides by the many thousands. Acres of land were dedicated solely for drying the hides of the slaughtered buffalo. Native Americans protested at the "wanton destruction" of their food supply. By 1874, 3,700,000 bison had been destroyed on the western and southern Plains of the United States. Concern for the destruction of the buffalo mounted, and a bill in Congress was passed, HR 921, that would have made buffalo hunting illegal for whites. Grant pocket veto

ed the bill. Ranchers favored the buffalo slaughter to open pasture land for their cattle herds. With the buffalo food supply lowered Native Americans were forced to stay on reservations.

under Secretary of the Interior Columbus Delano

. This proved to be the most serious detriment to Grant's Indian peace policy. Many agents that worked for the department made unscrupulous fortunes and retired with more money than their pay would allow. Secretary Delano had allowed "Indian Attorneys" who were paid by Native American tribes $8.00 a day plus food and traveling expenses for sham representation in Washington. Other corruptions charges were brought up against Secretary Delano and he was forced to resign; he had left the Bureau of Indian Affairs in complete corruption. In 1875, Grant appointed Zachariah Chandler

to Secretary of the Interior. Chandler vigorously uncovered and cleaned up the fraud in the department by firing all the clerks and banned the phony "Indian Attorneys" access to Washington. Grant's "Quaker" or church appointments partially made up the lack of food staples and housing from the government.

in the Dakota Territory

. White speculators and settlers rushed in droves seeking riches mining gold on land reserved for the Sioux

tribe by the Treaty of Fort Laramie

of 1868. In 1875, to avoid conflict President Grant met with Red Cloud

, chief of the Sioux, at Washington, D.C., and offered $25,000 from the government to purchase the land. The offer was declined. On November 3, 1875 at a White House meeting, Phil Sheridan claimed to the President that the Army was overstretched and could not defend the Sioux tribe from the settlers; Grant capitulated; ordered Sheridan to round up the Sioux and put them on the reservation. Sheridan used a strategy of convergence, using Army columns to force the Sioux onto the reservation. On June 25, 1876, one of these columns, led by Colonel George A. Custer met the Sioux at the Battle of Little Big Horn and was slaughtered. Approximately 253 federal soldiers and civilians were killed compared to 40 American Indians. Custer's death and the Battle of Little Big Horn shocked the nation. Sheridan avenged Custer, pacified the northern Plains, and put the defeated Sioux on the reservation. On August 15, 1876 President Grant signed a proviso giving the Sioux nation $1,000,000 in rations, while the Sioux relinquished all rights to the Black Hills, except for a 40 mile land tract west of the 103 meridian. On August 28, a seven man committee, appointed by Grant, gave additional harsh stipulations for the Sioux in order to receive government assistance. Halfbreeds and "squaw men" were banished from the Sioux reservation. To receive the government rations, the Indians had to work the land. Reluctantly, on September 20, the Indian leaders, whose people were starving, agreed to the committee's demands and signed the agreement.

that allowed citizens access to public eating establishments, hotels, and places of entertainment. This was done particularly to protect African Americans who were discriminated across United States. The bill was also passed in honor of Senator Charles Sumner

who had previously attempted to pass a civil rights bill in 1872.

, that he had been deceived concerning the Mormons. However, on December 7, 1875 after his return to Washington, Grant wrote to Congress in his seventh annual state of the Union address that as "an institution polygamy should be banished from the land…"

Grant believed that polygamy negatively affected children and women. Grant advocated that a second stronger law then the Morrill Act be passed to "punish so flagrant a crime against decency

and morality

."

Grant also denounced the immigration of Chinese women into the United States whose only purpose was prostitution

.

in public schools. Grant inexplicably in an 1875 speech advocated "security of free thought, free speech, and free press, pure morals, unfettered religious sentiments, and of equal rights and privileges to all men, irrespective of nationality, color, or religion." In regard to public education, Grant endorsed that every child should receive "the opportunity of a good common school education, unmixed with sectarian, pagan, or atheist tenets. Leave the matter of religion to the family altar, the church, and the private schools.... Keep the church and the state forever separate."

that started when the stock market in Vienna, Austria crashed in June that year. Unsettling markets soon spread to Berlin and throughout Europe. The panic eventually reached New York when two banks went broke – the New York Warehouse & Security Company on September 18 and the major railroad financier Jay Cooke & Company

on September 19. The ensuing depression lasted 5 years, ruined thousands of businesses, depressed daily wages by 25% from 1873 to 1876, and brought the unemployment rate up to 14%.

The causes of the panic in the United States included the destruction of credit from over-speculation in the stock markets and railroad industry. Eight years of unprecedented growth after the Civil War had brought thousands of miles of railroad construction, thousands of industrial factories, and a strong stock market; the South experienced a boom in agriculture. However, all this growth was done on borrowed money by many banks in the United States that have over-speculated in the Railroad industry by as much as $20 million. A stringent monetary policy under Secretary of Treasury George S. Boutwell

, during the height of the railroad speculations, contributed to unsettled markets. Boutwell created monetary stringency by selling more gold then he bought bonds. The Coinage Act of 1873 made gold the de facto

currency metal over silver.

On September 20, 1873 the Grant Administration finally responded. Grant's Secretary of Treasury William Adams Richardson

, Boutwell's replacement, bought $2.5 million of five-twenty bonds with gold. On Monday, September 22, Richardson bought $3 million of bonds with legal tender notes or greenbacks

and purchased $5.5 million in legal tender certificates. From September 24 to September 25 the Treasury department bought $24 million in bonds and certificates with greenbacks. On September 29 the Secretary prepaid the interest on $12 million bonds bought from security banks. From October, 1873 to January 4, 1874 Richardson kept liquidating bonds until $26 million greenback reserves were issued to make up for lost revenue in the Treasury. These actions did help curb the effects of the general panic by allowing more currency into the commercial banks and hence allowing more money to be lent and spent. Historians have blamed the Grant administration for not responding to the crisis promptly and for not taking adequate measures to reduce the negative effects of the general panic. The monetary policies of both Secretary Boutwell and Richardson were inconsistent from 1872 to 1873. The government's ultimate failure was in not reestablishing confidence in the businesses that had been the source of distrust. The Panic of 1873 eventually ran its course despite all the limited efforts from the government.

Grant's "cronyism", as Smith (2001) calls it, was apparent when he overruled Army experts to help a wartime friend, engineer, James B. Eads. Eads was building a major railroad bridge across the Mississippi at St. Louis that had been authorized by Congress in 1866, and was nearing completion in 1873. However, the Army Corps of Engineers chief of engineers, agreeing with steam boat interests, ordered Eads to build a canal around the bridge because the bridge would be "a serious obstacle to navigation." After talking with Eads at the White House, Grant reversed the order and the 6,442 feet (1,964 m) long steel arched bridge went on to completion in 1874 without a canal.

The rapidly accelerated industrial growth in post-Civil War America and throughout the world crashed with the Panic of 1873

. Many banks overextended their loans and went bankrupt as a result, causing a general panic throughout the nation. In an attempt put capital into a stringent monetary economy, Secretary of Treasury William A. Richardson released $26 million in greenbacks. Many argued that Richardson's monetary policies were not enough and some argued were illegal. In 1874, Congress debated the inflationary policy to stimulate the economy and passed the Inflation Bill of 1874 that would release an additional $18 million in greenbacks

up to the original $400,000,000 amount. Eastern bankers vigorously lobbied Grant to veto the bill because of their reliance on bonds and foreign investors who did business in gold. Grant's cabinet was bitterly divided over this issue while conservative Secretary of State Hamilton Fish

threatened to resign if Grant signed the bill. On April 22, 1874, after evaluating his own reasons for wanting to sign the bill, Grant unexpectedly vetoed the bill against the popular election strategy of the Republican Party

because he believed it would destroy the nation's credit.

. This act provided that paper money in circulation would be exchanged for gold specie and silver coins and would be effective January 1, 1879. The act also implemented that gradual steps would be taken to reduce the amount of greenbacks in circulation. At that time there were "paper coin" currency worth less than $1.00, and these would be exchanged for silver coins. Its effect was to stabilize the currency and make the consumers money as "good as gold". In an age without a Federal Reserve system to control inflation, this act stabilized the economy. Grant considered it the hallmark of his administration.

On October 31, 1873, a steamer Virginius, flying the American flag carrying war materials and men to aid the Cuban insurrection (in violation of American and Spanish law) was intercepted and taken to Cuba. After a hasty trial, the local Spanish officials executed 53 would-be insurgents, eight of whom were United States citizens; orders from Madrid to delay the executions arrived too late. War scares erupted in both the U.S. and Spain, heightened by the bellicose dispatches from the American minister in Madrid, retired general Daniel Sickles

On October 31, 1873, a steamer Virginius, flying the American flag carrying war materials and men to aid the Cuban insurrection (in violation of American and Spanish law) was intercepted and taken to Cuba. After a hasty trial, the local Spanish officials executed 53 would-be insurgents, eight of whom were United States citizens; orders from Madrid to delay the executions arrived too late. War scares erupted in both the U.S. and Spain, heightened by the bellicose dispatches from the American minister in Madrid, retired general Daniel Sickles

. Secretary of State Fish kept a cool demeanor in the crisis, and through investigation discovered there was a question over whether the Virginius ship had the right to bear the United States flag. The Spanish Rupublic's President Emilio Castelar expressed profound regret for the tragedy and was willing to make reparations through arbitration. Fish negotiated reparations with the Spanish minister Senor Poly y Bernabe. With Grant's approval, Spain was to surrender Virginius, pay an indemnity to the surviving families of the Americans executed, and salute the American flag; the episode ended quietly.

treaty with Hawaii

. The main product from Hawaii, sugar

, was made duty free while American manufactured goods, including clothing, were allowed to be sold in the island kingdom.

. Liberia was in practice an American colony. US envoy James Milton Turner, the first African American ambassador, requested a warship to protect American property in Liberia. After the USS Alaska he negotiated the incorporation of Grebo people into Liberian society and the ousting of foreign traders from Liberia.

where the investigation went up to Grant himself. The Emma Silver mine was a minor embarrassment associated with American Ambassador to Britain, Robert C. Schenck

, using his name to promote a worked out silver mine. The Crédit Mobilier scandal's origins were during the presidential Administrations of Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson, however, political congressional infighting during the Grant Administration exposed the scandal.

gave private contracts to one John D. Sanborn who in turn collected illegally withheld taxes for fees at inflated commissions. The profits from the commissions were allegedly split with Richardson and Senator Benjamin Butler

, while Sanborn claimed these payments were "expenses". Senator Butler had written a loophole in the law that allowed Sanborn to collect the commissions, but Sanborn would not reveal whom he split the profits with.

allegedly received a bribe through a $30,000 gift to his wife from a Merchant house company, Pratt & Boyd, to drop the case for fraudulent customhouse entries. Williams was forced to resign by Grant in 1875.

In 1875, the U.S. Department of Interior was in serious disrepair with corruption and incompetence. The Secretary of Interior Columbus Delano

In 1875, the U.S. Department of Interior was in serious disrepair with corruption and incompetence. The Secretary of Interior Columbus Delano

, discovered to have taken bribes to secure fraudulent land grants, resigned from office on October 15, 1875. Delano had also given bogus lucrative cartographical contracts to his son John Delano and Ulysses S. Grant's own brother, Orvil Grant. Neither John Delano nor Orvil Grant performed any work or were skillfully qualified to hold such surveying positions. The Department of Indian Affairs was being controlled by corrupt clerks and bogus agents who made enormous profits from the exploitation of Native American tribes. Massive fraud was also found in the Patent Office with corrupt clerks who embezzled from the government payroll. Delano who refused to make any reforms resigned under public pressure rather than Grant asking for a resignation. It was another missed opportunity for Grant to support ethics in government. However, on October 19, 1875, Grant made another reforming cabinet choice when he appointed Zachariah Chandler

as Secretary of the Interior. Chandler cleaned up the Patent Office and the Department of Indian Affairs by firing all the corrupt clerks and banned bogus agents.

was indicted and later acquitted in trial. The Whiskey Ring was organized throughout the United States, and by 1875 it was a fully operating criminal association. The investigation and closure of the Whiskey Ring resulted in 230 indictments, 110 convictions, and $3,000,000 in tax revenues that were returned to the Treasury Department. During the prosecution of the Whiskey Ring leaders, Grant testified on behalf of his friend Babcock. As a result, Babcock was acquitted, however, the deposition by Grant was a great embarrassment to his reputation. The Babcock trial turned into an impeachment trial against the President by Grant's political opponents.

was taking extortion money in exchange for allowing an Indian trading post agent to remain in position at Fort Sill