Daniel Sickles

Encyclopedia

Daniel Edgar Sickles was a colorful and controversial American politician, Union

general in the American Civil War

, and diplomat.

As an antebellum New York

politician, Sickles was involved in a number of public scandals, most notably the killing of his wife's lover, Philip Barton Key II, son of Francis Scott Key

. He was acquitted with the first use of temporary insanity as a legal defense in U.S. history. He became one of the most prominent political general

s of the Civil War. At the Battle of Gettysburg

, he insubordinately moved his III Corps to a position in which it was virtually destroyed, an action that continues to generate controversy. His combat career ended at Gettysburg when his leg was struck by cannon fire.

After the war, Sickles commanded military districts during Reconstruction, served as U.S. Minister to Spain

, and eventually returned to the U.S. Congress, where he made important legislative contributions to the preservation of the Gettysburg Battlefield

.

to Susan Marsh Sickles and George Garrett Sickles, a patent lawyer and politician. (His year of birth is sometimes given as 1825, and, in fact, Sickles himself was known to have claimed as such. Historians speculate that Sickles deliberately chose to appear younger when he married a woman half his age.) He learned the printer's trade and studied at the University of the City of New York (now New York University

). He studied law in the office of Benjamin Butler

, was admitted to the bar

in 1846, and was a member of the New York Assembly in 1843.

In 1852, he married Teresa Bagioli

against the wishes of both families—he was 33, she only 15, although she was sophisticated for her age, speaking five languages. In 1853 he became corporation counsel

of New York City, but resigned soon afterward to become secretary of the U.S. legation

in London, under James Buchanan

, by appointment of President

Franklin Pierce

. He returned to America in 1855, was a member of the Senate of New York State from 1856 to 1857, and, from 1857 to 1861, was a Democratic representative

in the United States Congress

(the 35th

and 36th United States Congress

es).

Sickles's career was replete with personal scandals. He was censured by the New York State Assembly

Sickles's career was replete with personal scandals. He was censured by the New York State Assembly

for escorting a known prostitute, Fanny White

, into its chambers. He also reportedly took her to England, leaving his pregnant wife at home, and presented White to Queen Victoria

, using as her alias the surname of a New York political opponent. In 1859, in Lafayette Square

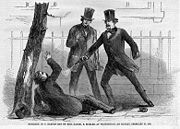

, across the street from the White House

, Sickles shot and killed the district attorney

of the District of Columbia Philip Barton Key II, son of Francis Scott Key

, whom Sickles had discovered was having an affair with his young wife.

Jeremiah Black's house, a few blocks away on Franklin Square

, and confessed to the murder

. After a visit to his home, accompanied by a constable, Sickles was taken to jail. He was able to receive visitors, and so many came that he was granted the use of the head jailer's apartment to receive them. This was one of several odd features of his confinement. He was also allowed to retain his personal weapon, unusual even for the time. The press reported heavy visitor traffic, including many representatives, senators, and other leading members of Washington society. President James Buchanan

sent Sickles a personal note.

Most painful for Sickles, according to Harper's Magazine

, were the visits of his wife's mother and her clergyman. Both told him that Teresa was distracted with grief, shame, and sorrow, and that the loss of her wedding ring (which Sickles had taken on visiting his home) was more than Teresa could bear.

Sickles was charged with murder. He secured several leading politicians as his defense attorneys, among them Edwin M. Stanton

, later to become Secretary of War

, and Chief Counsel James T. Brady, like Sickles a product of Tammany Hall

. In a historic strategy, Sickles pled insanity—the first use of a temporary insanity defense in the United States. Before the jury, Stanton argued that Sickles had been driven insane by his wife's infidelity, and thus was out of his mind when he shot Key. The papers soon trumpeted that Sickles was a hero for saving all the ladies of Washington from this rogue named Key.

The graphic confession that Sickles had obtained from Teresa on Saturday proved pivotal. It was ruled inadmissible in court, but, leaked by Sickles to the press, was printed in the newspapers in full. The defense strategy ensured that the trial was the main topic of conversations in Washington for weeks, and the extensive coverage of national papers was sympathetic to Sickles. In the courtroom, the strategy brought drama, controversy, and, ultimately, an acquittal for Sickles.

Sickles then publicly forgave Teresa, and "withdrew" briefly from public life, although he did not resign from Congress. The public was apparently more outraged by Sickles' forgiveness and reconciliation with his wife, whom he had publicly branded a harlot and adulteress, than by the murder and his unorthodox acquittal.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Sickles desired to repair his public image and was active in raising volunteers in New York. He was appointed colonel

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Sickles desired to repair his public image and was active in raising volunteers in New York. He was appointed colonel

of one of the four regiments he organized. He was promoted to brigadier general

of volunteers in September 1861, becoming one of the most famous political general

s in the Union Army

. In March 1862, he was forced to relinquish his command when the U.S. Congress refused to confirm his commission, but he worked diligently to lobby among his Washington political contacts and reclaimed both his rank and his command on May 24, 1862, in time to rejoin the Army in the Peninsula Campaign

. Because of this interruption, he missed his brigade's significant actions at the Battle of Williamsburg

. Despite his complete lack of previous military experience, he did a competent job commanding the "Excelsior Brigade

" of the Army of the Potomac

in the Battle of Seven Pines

and the Seven Days Battles

. He was absent for the Second Battle of Bull Run

, having used his political influences to obtain leave to go to New York City to recruit new troops. He also missed the Battle of Antietam

because the III Corps, to which he was assigned as a division commander, was stationed on the lower Potomac

, protecting the capital.

Sickles was a close ally of Major General

Joseph Hooker

, who was his original division commander and eventually commanded the Army of the Potomac. Both men had notorious reputations as political climbers and as hard-drinking ladies' men. Accounts at the time compared their army headquarters to a rowdy bar and bordello.

Sickles was promoted to major general on November 29, 1862, just before the Battle of Fredericksburg

, in which his division was in reserve. Hooker, now commanding the Army of the Potomac, gave Sickles command of the III Corps in February 1863, a controversial move in the army because he became the only corps commander without a West Point education. His energy and ability were conspicuous in the Battle of Chancellorsville

. He aggressively recommended pursuing troops he saw in his sector on May 2, 1863. Sickles thought the Confederates were retreating, but these turned out to be elements of Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's

corps, stealthily marching around the Union flank. He also vigorously opposed Hooker's orders moving him off good defensive terrain in Hazel Grove. In both of these cases, it is easy to imagine the disastrous battle turning out very differently for the Union if Hooker had heeded his advice.

marked the most famous incident, and the effective end, of Sickles' military career. On July 2, 1863, Army of the Potomac commander Major General George G. Meade ordered Sickles' corps to take up defensive positions on the southern end of Cemetery Ridge

, anchored in the north to the II Corps and to the south, the hill known as Little Round Top

. Sickles was unhappy to see a slightly higher terrain feature to his front, the "Peach Orchard". Perhaps remembering the beating his corps had taken from Confederate artillery at Hazel Grove during the Battle of Chancellorsville, he violated orders by marching his corps almost a mile in front of Cemetery Ridge. This had two effects: it greatly diluted the concentrated defensive posture of his corps by stretching it too thin, and it created a salient that could be bombarded and attacked from multiple sides. Meade rode out and confronted Sickles about his insubordination, but it was too late. The Confederate assault by Lieutenant General James Longstreet

's corps, primarily by the division of Major General Lafayette McLaws

, smashed the III Corps and rendered it useless for further combat. Gettysburg campaign historian Edwin B. Coddington assigns "much of the blame for the near disaster" in the center of the Union line to Sickles. Stephen W. Sears

wrote that "Dan Sickles, in not obeying Meade's explicit orders, risked both his Third Corps and the army's defensive plan on July 2. However, Sickles' maneuver has recently been credited by John Keegan

with blunting the whole Confederate offensive that was intended to cause the collapse of the Union line. Similarly, James M. McPherson

wrote that "Sickles's unwise move may have unwittingly foiled Lee's hopes."

During the height of the Confederate attack, Sickles fell victim to a cannonball that mangled his right leg. Carried by stretcher to an aid station, he bravely attempted to raise his soldiers' spirits by grinning and puffing on a cigar along the way. His leg was amputated that afternoon. He insisted on being transported back to Washington, D.C.

, which he reached on July 4, 1863, bringing some of the first news of the great Union victory, and starting a public relations campaign to ensure his version of the battle prevailed.

Sickles had recent knowledge of a new directive from the Army Surgeon General to collect and forward "specimens of morbid anatomy ... together with projectiles and foreign bodies removed" to the newly founded Army Medical Museum

in Washington, D.C.

He preserved the bones from his leg and donated them to the museum in a small coffin-shaped box, along with a visiting card marked, "With the compliments of Major General D.E.S." For several years thereafter, he reportedly visited the limb on the anniversary of the amputation. The museum, now known as the National Museum of Health and Medicine

, features the artifact on display still today. (Other Civil War-era specimens of note on display include the hip of General Henry Barnum, and in the collection but not on display include the vertebrae from assassin John Wilkes Booth

and President James A. Garfield.)

Sickles was not court-martial

ed for insubordination after Gettysburg because he had been wounded, and it was assumed he would stay out of trouble. Furthermore, he was a powerful, politically connected man who would not accept being disciplined without protest and retribution.

Sickles ran a vicious campaign against General Meade's character after the Civil War. Sickles felt that Meade had wronged him at Gettysburg and that credit for winning the battle belonged to him. In anonymous newspaper articles and in testimony before a congressional committee, Sickles maintained that Meade had secretly planned to retreat from Gettysburg on the first day. While his movement away from Cemetery Ridge may have violated orders, Sickles always asserted that it was the correct move because it disrupted the Confederate attack, redirecting its thrust, effectively shielding their real objectives, Cemetery Ridge and Cemetery Hill

. Sickles' redeployment did in fact take Confederate commanders by surprise, and historians have argued about the real ramifications ever since.

Sickles eventually received the Medal of Honor

for his actions, although it took him 34 years to get it. The official citation that accompanied his medal recorded that Sickles "displayed most conspicuous gallantry on the field, vigorously contesting the advance of the enemy and continuing to encourage his troops after being himself severely wounded."

would not allow him to return to a combat command. In 1867, he received appointments as brevet

brigadier general and major general in the regular army for his services at Fredericksburg and Gettysburg, respectively.

Soon after the close of the Civil War, in 1865, he was sent on a confidential mission to Colombia

(the "special mission to the South American Republics") to secure its compliance with a treaty agreement of 1846 permitting the United States to convey troops across the Isthmus of Panama

. From 1865 to 1867, he commanded the Department of South Carolina, the Department of the Carolinas, the Department of the South, and the Second Military District

. In 1866, he was appointed colonel of the 42nd U.S. Infantry (Veteran Reserve Corps

), and in 1869 he was retired with the rank of major general.

Sickles served as U.S. Minister to Spain

from 1869 to 1874, after the Senate failed to confirm Henry Shelton Sanford

to the post, and took part in the negotiations growing out of the Virginius Affair

. His inaccurate and emotional messages to Washington promoted war, until he was overruled by Secretary of State Hamilton Fish

and the war scare died out.

Sickles maintained his reputation as a ladies' man in the Spanish royal court and was rumored to have had an affair with the deposed Queen Isabella II

. Following the death of Teresa in 1867, in 1871, he married Senorita Carmina Creagh, the daughter of Chevalier de Creagh of Madrid, a Spanish Councillor of State. They had two children.

Sickles was president of the New York State Board of Civil Service Commissioners from 1888 to 1889, sheriff of New York

in 1890, and again a representative in the 53rd Congress from 1893 to 1895. For most of his postwar life, he was the chairman of the New York Monuments Commission

, but he was forced out when $27,000 was found to have been embezzled.

He had an important part in efforts to preserve the Gettysburg Battlefield

, sponsoring legislation to form the Gettysburg National Military Park

, buy up private lands, and erect monuments. One of his contributions was procuring the original fencing used on East Cemetery Hill to mark the park's borders. This fencing came directly from Lafayette Square

in Washington, D.C. (site of the Key shooting). Of the principal senior generals who fought at Gettysburg, virtually all, with the conspicuous exception of Sickles, have been memorialized with statues at Gettysburg. When asked why there was no memorial to him, Sickles supposedly said, "The entire battlefield is a memorial to Dan Sickles." However, there was, in fact, a memorial commissioned to include a bust of Sickles, the monument to the New York Excelsior Brigade. It was rumored that the money appropriated for the bust was stolen by Sickles himself; the monument is displayed in the Peach Orchard with a figure of an eagle instead of Sickles' likeness.

, dying on May 3, 1914. His funeral was held at St. Patrick's Cathedral in Manhattan on May 8, 1914. He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery

.

Civil War trilogy by Newt Gingrich

and William R. Forstchen

.

Citation:

Union Army

The Union Army was the land force that fought for the Union during the American Civil War. It was also known as the Federal Army, the U.S. Army, the Northern Army and the National Army...

general in the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

, and diplomat.

As an antebellum New York

New York

New York is a state in the Northeastern region of the United States. It is the nation's third most populous state. New York is bordered by New Jersey and Pennsylvania to the south, and by Connecticut, Massachusetts and Vermont to the east...

politician, Sickles was involved in a number of public scandals, most notably the killing of his wife's lover, Philip Barton Key II, son of Francis Scott Key

Francis Scott Key

Francis Scott Key was an American lawyer, author, and amateur poet, from Georgetown, who wrote the lyrics to the United States' national anthem, "The Star-Spangled Banner".-Life:...

. He was acquitted with the first use of temporary insanity as a legal defense in U.S. history. He became one of the most prominent political general

Political general

A political general is a general officer or other military leader without significant military experience who is given a high position in command for political reasons, such as his own connections or to appease certain political blocs...

s of the Civil War. At the Battle of Gettysburg

Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg , was fought July 1–3, 1863, in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. The battle with the largest number of casualties in the American Civil War, it is often described as the war's turning point. Union Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade's Army of the Potomac...

, he insubordinately moved his III Corps to a position in which it was virtually destroyed, an action that continues to generate controversy. His combat career ended at Gettysburg when his leg was struck by cannon fire.

After the war, Sickles commanded military districts during Reconstruction, served as U.S. Minister to Spain

United States Ambassador to Spain

-Ambassadors:*John Jay**Appointed: September 29, 1779**Title: Minister Plenipotentiary**Presented credentials:**Terminated mission: ~May 20, 1782*William Carmichael**Appointed: April 20, 1790**Title: Chargé d'Affaires...

, and eventually returned to the U.S. Congress, where he made important legislative contributions to the preservation of the Gettysburg Battlefield

Gettysburg Battlefield

The Gettysburg Battlefield is the area of the July 1–3, 1863, military engagements of the Battle of Gettysburg within and around the borough of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Locations of military engagements extend from the 4 acre site of the first shot & at on the west of the borough, to East...

.

Early life and politics

Sickles was born in New York CityNew York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

to Susan Marsh Sickles and George Garrett Sickles, a patent lawyer and politician. (His year of birth is sometimes given as 1825, and, in fact, Sickles himself was known to have claimed as such. Historians speculate that Sickles deliberately chose to appear younger when he married a woman half his age.) He learned the printer's trade and studied at the University of the City of New York (now New York University

New York University

New York University is a private, nonsectarian research university based in New York City. NYU's main campus is situated in the Greenwich Village section of Manhattan...

). He studied law in the office of Benjamin Butler

Benjamin Franklin Butler (lawyer)

Benjamin Franklin Butler was a lawyer, legislator and Attorney General of the United States.-Early life:...

, was admitted to the bar

Bar association

A bar association is a professional body of lawyers. Some bar associations are responsible for the regulation of the legal profession in their jurisdiction; others are professional organizations dedicated to serving their members; in many cases, they are both...

in 1846, and was a member of the New York Assembly in 1843.

In 1852, he married Teresa Bagioli

Teresa Bagioli Sickles

Teresa Bagioli Sickles was the wife of Democratic New York State Assemblyman, U.S. Representative, and later U.S. Army Major General Daniel E. Sickles. She gained notoriety in 1859, when her husband stood trial for the murder of her lover, Philip Barton Key, son of Francis Scott Key...

against the wishes of both families—he was 33, she only 15, although she was sophisticated for her age, speaking five languages. In 1853 he became corporation counsel

Corporation Counsel

The Corporation Counsel is the title given to the chief legal officer in some municipal and county jurisdictions, who handles civil claims against the city, including negotiating settlements and defending the city when it is sued. Most corporation counsels do not prosecute criminal cases, though...

of New York City, but resigned soon afterward to become secretary of the U.S. legation

Legation

A legation was the term used in diplomacy to denote a diplomatic representative office lower than an embassy. Where an embassy was headed by an Ambassador, a legation was headed by a Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary....

in London, under James Buchanan

James Buchanan

James Buchanan, Jr. was the 15th President of the United States . He is the only president from Pennsylvania, the only president who remained a lifelong bachelor and the last to be born in the 18th century....

, by appointment of President

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

Franklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce was the 14th President of the United States and is the only President from New Hampshire. Pierce was a Democrat and a "doughface" who served in the U.S. House of Representatives and the Senate. Pierce took part in the Mexican-American War and became a brigadier general in the Army...

. He returned to America in 1855, was a member of the Senate of New York State from 1856 to 1857, and, from 1857 to 1861, was a Democratic representative

United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is one of the two Houses of the United States Congress, the bicameral legislature which also includes the Senate.The composition and powers of the House are established in Article One of the Constitution...

in the United States Congress

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the bicameral legislature of the federal government of the United States, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Congress meets in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C....

(the 35th

35th United States Congress

The 35th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1857 to March 3, 1859, during the first two years of James...

and 36th United States Congress

36th United States Congress

The Thirty-sixth United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1859 to March 4, 1861, during the third and fourth...

es).

Murder of Key

New York State Assembly

The New York State Assembly is the lower house of the New York State Legislature. The Assembly is composed of 150 members representing an equal number of districts, with each district having an average population of 128,652...

for escorting a known prostitute, Fanny White

Fanny White

Fanny White, a.k.a. Jane Augusta Blankman was one of the most successful courtesans of ante-bellum New York City. Known for her beauty, wit, and business acumen, Fanny White accumulated a significant fortune over the course of her career, married a middle-class lawyer in her thirties, and died...

, into its chambers. He also reportedly took her to England, leaving his pregnant wife at home, and presented White to Queen Victoria

Victoria of the United Kingdom

Victoria was the monarch of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death. From 1 May 1876, she used the additional title of Empress of India....

, using as her alias the surname of a New York political opponent. In 1859, in Lafayette Square

Lafayette Square

Lafayette Square may refer to a place in the United States:*Lafayette Square, Los Angeles, California, a neighborhood in the mid-city section of L.A.*Lafayette Square, New Orleans, Louisiana, in the Central Business District*Lafayette Square, St...

, across the street from the White House

White House

The White House is the official residence and principal workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., the house was designed by Irish-born James Hoban, and built between 1792 and 1800 of white-painted Aquia sandstone in the Neoclassical...

, Sickles shot and killed the district attorney

District attorney

In many jurisdictions in the United States, a District Attorney is an elected or appointed government official who represents the government in the prosecution of criminal offenses. The district attorney is the highest officeholder in the jurisdiction's legal department and supervises a staff of...

of the District of Columbia Philip Barton Key II, son of Francis Scott Key

Francis Scott Key

Francis Scott Key was an American lawyer, author, and amateur poet, from Georgetown, who wrote the lyrics to the United States' national anthem, "The Star-Spangled Banner".-Life:...

, whom Sickles had discovered was having an affair with his young wife.

Trial

Sickles surrendered at Attorney GeneralAttorney General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general, or attorney-general, is the main legal advisor to the government, and in some jurisdictions he or she may also have executive responsibility for law enforcement or responsibility for public prosecutions.The term is used to refer to any person...

Jeremiah Black's house, a few blocks away on Franklin Square

Franklin Square (Washington, D.C.)

Franklin Square is a square in downtown Washington, D.C.. Named after Benjamin Franklin, it is bounded by K Street Northwest to the north, 13th Street NW on the east, I Street NW on the south, and 14th Street NW on the west. It is served by the McPherson Square station of the Washington Metro,...

, and confessed to the murder

Murder

Murder is the unlawful killing, with malice aforethought, of another human being, and generally this state of mind distinguishes murder from other forms of unlawful homicide...

. After a visit to his home, accompanied by a constable, Sickles was taken to jail. He was able to receive visitors, and so many came that he was granted the use of the head jailer's apartment to receive them. This was one of several odd features of his confinement. He was also allowed to retain his personal weapon, unusual even for the time. The press reported heavy visitor traffic, including many representatives, senators, and other leading members of Washington society. President James Buchanan

James Buchanan

James Buchanan, Jr. was the 15th President of the United States . He is the only president from Pennsylvania, the only president who remained a lifelong bachelor and the last to be born in the 18th century....

sent Sickles a personal note.

Most painful for Sickles, according to Harper's Magazine

Harper's Magazine

Harper's Magazine is a monthly magazine of literature, politics, culture, finance, and the arts, with a generally left-wing perspective. It is the second-oldest continuously published monthly magazine in the U.S. . The current editor is Ellen Rosenbush, who replaced Roger Hodge in January 2010...

, were the visits of his wife's mother and her clergyman. Both told him that Teresa was distracted with grief, shame, and sorrow, and that the loss of her wedding ring (which Sickles had taken on visiting his home) was more than Teresa could bear.

Sickles was charged with murder. He secured several leading politicians as his defense attorneys, among them Edwin M. Stanton

Edwin M. Stanton

Edwin McMasters Stanton was an American lawyer and politician who served as Secretary of War under the Lincoln Administration during the American Civil War from 1862–1865...

, later to become Secretary of War

United States Secretary of War

The Secretary of War was a member of the United States President's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War," was appointed to serve the Congress of the Confederation under the Articles of Confederation...

, and Chief Counsel James T. Brady, like Sickles a product of Tammany Hall

Tammany Hall

Tammany Hall, also known as the Society of St. Tammany, the Sons of St. Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was a New York political organization founded in 1786 and incorporated on May 12, 1789 as the Tammany Society...

. In a historic strategy, Sickles pled insanity—the first use of a temporary insanity defense in the United States. Before the jury, Stanton argued that Sickles had been driven insane by his wife's infidelity, and thus was out of his mind when he shot Key. The papers soon trumpeted that Sickles was a hero for saving all the ladies of Washington from this rogue named Key.

The graphic confession that Sickles had obtained from Teresa on Saturday proved pivotal. It was ruled inadmissible in court, but, leaked by Sickles to the press, was printed in the newspapers in full. The defense strategy ensured that the trial was the main topic of conversations in Washington for weeks, and the extensive coverage of national papers was sympathetic to Sickles. In the courtroom, the strategy brought drama, controversy, and, ultimately, an acquittal for Sickles.

Sickles then publicly forgave Teresa, and "withdrew" briefly from public life, although he did not resign from Congress. The public was apparently more outraged by Sickles' forgiveness and reconciliation with his wife, whom he had publicly branded a harlot and adulteress, than by the murder and his unorthodox acquittal.

Civil War

Colonel (United States)

In the United States Army, Air Force, and Marine Corps, colonel is a senior field grade military officer rank just above the rank of lieutenant colonel and just below the rank of brigadier general...

of one of the four regiments he organized. He was promoted to brigadier general

Brigadier general (United States)

A brigadier general in the United States Army, Air Force, and Marine Corps, is a one-star general officer, with the pay grade of O-7. Brigadier general ranks above a colonel and below major general. Brigadier general is equivalent to the rank of rear admiral in the other uniformed...

of volunteers in September 1861, becoming one of the most famous political general

Political general

A political general is a general officer or other military leader without significant military experience who is given a high position in command for political reasons, such as his own connections or to appease certain political blocs...

s in the Union Army

Union Army

The Union Army was the land force that fought for the Union during the American Civil War. It was also known as the Federal Army, the U.S. Army, the Northern Army and the National Army...

. In March 1862, he was forced to relinquish his command when the U.S. Congress refused to confirm his commission, but he worked diligently to lobby among his Washington political contacts and reclaimed both his rank and his command on May 24, 1862, in time to rejoin the Army in the Peninsula Campaign

Peninsula Campaign

The Peninsula Campaign of the American Civil War was a major Union operation launched in southeastern Virginia from March through July 1862, the first large-scale offensive in the Eastern Theater. The operation, commanded by Maj. Gen. George B...

. Because of this interruption, he missed his brigade's significant actions at the Battle of Williamsburg

Battle of Williamsburg

The Battle of Williamsburg, also known as the Battle of Fort Magruder, took place on May 5, 1862, in York County, James City County, and Williamsburg, Virginia, as part of the Peninsula Campaign of the American Civil War...

. Despite his complete lack of previous military experience, he did a competent job commanding the "Excelsior Brigade

Excelsior Brigade

The Excelsior Brigade was a military unit in the Union Army during the American Civil War. Comprising primarily infantry regiments raised in the state of New York primarily by former U.S...

" of the Army of the Potomac

Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the major Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War.-History:The Army of the Potomac was created in 1861, but was then only the size of a corps . Its nucleus was called the Army of Northeastern Virginia, under Brig. Gen...

in the Battle of Seven Pines

Battle of Seven Pines

The Battle of Seven Pines, also known as the Battle of Fair Oaks or Fair Oaks Station, took place on May 31 and June 1, 1862, in Henrico County, Virginia, as part of the Peninsula Campaign of the American Civil War. It was the culmination of an offensive up the Virginia Peninsula by Union Maj. Gen....

and the Seven Days Battles

Seven Days Battles

The Seven Days Battles was a series of six major battles over the seven days from June 25 to July 1, 1862, near Richmond, Virginia during the American Civil War. Confederate General Robert E. Lee drove the invading Union Army of the Potomac, commanded by Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, away from...

. He was absent for the Second Battle of Bull Run

Second Battle of Bull Run

The Second Battle of Bull Run or Second Manassas was fought August 28–30, 1862, as part of the American Civil War. It was the culmination of an offensive campaign waged by Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia against Union Maj. Gen...

, having used his political influences to obtain leave to go to New York City to recruit new troops. He also missed the Battle of Antietam

Battle of Antietam

The Battle of Antietam , fought on September 17, 1862, near Sharpsburg, Maryland, and Antietam Creek, as part of the Maryland Campaign, was the first major battle in the American Civil War to take place on Northern soil. It was the bloodiest single-day battle in American history, with about 23,000...

because the III Corps, to which he was assigned as a division commander, was stationed on the lower Potomac

Potomac River

The Potomac River flows into the Chesapeake Bay, located along the mid-Atlantic coast of the United States. The river is approximately long, with a drainage area of about 14,700 square miles...

, protecting the capital.

Sickles was a close ally of Major General

Major general (United States)

In the United States Army, United States Marine Corps, and United States Air Force, major general is a two-star general-officer rank, with the pay grade of O-8. Major general ranks above brigadier general and below lieutenant general...

Joseph Hooker

Joseph Hooker

Joseph Hooker was a career United States Army officer, achieving the rank of major general in the Union Army during the American Civil War. Although he served throughout the war, usually with distinction, Hooker is best remembered for his stunning defeat by Confederate General Robert E...

, who was his original division commander and eventually commanded the Army of the Potomac. Both men had notorious reputations as political climbers and as hard-drinking ladies' men. Accounts at the time compared their army headquarters to a rowdy bar and bordello.

Sickles was promoted to major general on November 29, 1862, just before the Battle of Fredericksburg

Battle of Fredericksburg

The Battle of Fredericksburg was fought December 11–15, 1862, in and around Fredericksburg, Virginia, between General Robert E. Lee's Confederate Army of Northern Virginia and the Union Army of the Potomac, commanded by Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside...

, in which his division was in reserve. Hooker, now commanding the Army of the Potomac, gave Sickles command of the III Corps in February 1863, a controversial move in the army because he became the only corps commander without a West Point education. His energy and ability were conspicuous in the Battle of Chancellorsville

Battle of Chancellorsville

The Battle of Chancellorsville was a major battle of the American Civil War, and the principal engagement of the Chancellorsville Campaign. It was fought from April 30 to May 6, 1863, in Spotsylvania County, Virginia, near the village of Chancellorsville. Two related battles were fought nearby on...

. He aggressively recommended pursuing troops he saw in his sector on May 2, 1863. Sickles thought the Confederates were retreating, but these turned out to be elements of Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's

Stonewall Jackson

ຄຽשת״ׇׂׂׂׂ֣|birth_place= Clarksburg, Virginia |death_place=Guinea Station, Virginia|placeofburial=Stonewall Jackson Memorial CemeteryLexington, Virginia|placeofburial_label= Place of burial|image=...

corps, stealthily marching around the Union flank. He also vigorously opposed Hooker's orders moving him off good defensive terrain in Hazel Grove. In both of these cases, it is easy to imagine the disastrous battle turning out very differently for the Union if Hooker had heeded his advice.

Gettysburg

The Battle of GettysburgBattle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg , was fought July 1–3, 1863, in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. The battle with the largest number of casualties in the American Civil War, it is often described as the war's turning point. Union Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade's Army of the Potomac...

marked the most famous incident, and the effective end, of Sickles' military career. On July 2, 1863, Army of the Potomac commander Major General George G. Meade ordered Sickles' corps to take up defensive positions on the southern end of Cemetery Ridge

Cemetery Ridge

Cemetery Ridge is a geographic feature in Gettysburg National Military Park south of the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, that figured prominently in the Battle of Gettysburg, July 1 to July 3, 1863. It formed a primary defensive position for the Union Army during the battle, roughly the center of...

, anchored in the north to the II Corps and to the south, the hill known as Little Round Top

Little Round Top

Little Round Top is the smaller of two rocky hills south of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. It was the site of an unsuccessful assault by Confederate troops against the Union left flank on July 2, 1863, the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg....

. Sickles was unhappy to see a slightly higher terrain feature to his front, the "Peach Orchard". Perhaps remembering the beating his corps had taken from Confederate artillery at Hazel Grove during the Battle of Chancellorsville, he violated orders by marching his corps almost a mile in front of Cemetery Ridge. This had two effects: it greatly diluted the concentrated defensive posture of his corps by stretching it too thin, and it created a salient that could be bombarded and attacked from multiple sides. Meade rode out and confronted Sickles about his insubordination, but it was too late. The Confederate assault by Lieutenant General James Longstreet

James Longstreet

James Longstreet was one of the foremost Confederate generals of the American Civil War and the principal subordinate to General Robert E. Lee, who called him his "Old War Horse." He served under Lee as a corps commander for many of the famous battles fought by the Army of Northern Virginia in the...

's corps, primarily by the division of Major General Lafayette McLaws

Lafayette McLaws

Lafayette McLaws was a United States Army officer and a Confederate general in the American Civil War.-Early life:...

, smashed the III Corps and rendered it useless for further combat. Gettysburg campaign historian Edwin B. Coddington assigns "much of the blame for the near disaster" in the center of the Union line to Sickles. Stephen W. Sears

Stephen W. Sears

Stephen Ward Sears is an American historian specializing in the American Civil War.A graduate of Lakewood High School and Oberlin College, Sears attended a journalism seminar at...

wrote that "Dan Sickles, in not obeying Meade's explicit orders, risked both his Third Corps and the army's defensive plan on July 2. However, Sickles' maneuver has recently been credited by John Keegan

John Keegan

Sir John Keegan OBE FRSL is a British military historian, lecturer, writer and journalist. He has published many works on the nature of combat between the 14th and 21st centuries concerning land, air, maritime, and intelligence warfare, as well as the psychology of battle.-Life and career:John...

with blunting the whole Confederate offensive that was intended to cause the collapse of the Union line. Similarly, James M. McPherson

James M. McPherson

James M. McPherson is an American Civil War historian, and is the George Henry Davis '86 Professor Emeritus of United States History at Princeton University. He received the 1989 Pulitzer Prize for Battle Cry of Freedom, his most famous book...

wrote that "Sickles's unwise move may have unwittingly foiled Lee's hopes."

During the height of the Confederate attack, Sickles fell victim to a cannonball that mangled his right leg. Carried by stretcher to an aid station, he bravely attempted to raise his soldiers' spirits by grinning and puffing on a cigar along the way. His leg was amputated that afternoon. He insisted on being transported back to Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

, which he reached on July 4, 1863, bringing some of the first news of the great Union victory, and starting a public relations campaign to ensure his version of the battle prevailed.

Sickles had recent knowledge of a new directive from the Army Surgeon General to collect and forward "specimens of morbid anatomy ... together with projectiles and foreign bodies removed" to the newly founded Army Medical Museum

National Museum of Health and Medicine

The National Museum of Health and Medicine is a museum in Silver Spring, Maryland, near Washington, D.C., USA. An element of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, the NMHM is a member of the National Health Sciences Consortium....

in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

He preserved the bones from his leg and donated them to the museum in a small coffin-shaped box, along with a visiting card marked, "With the compliments of Major General D.E.S." For several years thereafter, he reportedly visited the limb on the anniversary of the amputation. The museum, now known as the National Museum of Health and Medicine

National Museum of Health and Medicine

The National Museum of Health and Medicine is a museum in Silver Spring, Maryland, near Washington, D.C., USA. An element of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, the NMHM is a member of the National Health Sciences Consortium....

, features the artifact on display still today. (Other Civil War-era specimens of note on display include the hip of General Henry Barnum, and in the collection but not on display include the vertebrae from assassin John Wilkes Booth

John Wilkes Booth

John Wilkes Booth was an American stage actor who assassinated President Abraham Lincoln at Ford's Theatre, in Washington, D.C., on April 14, 1865. Booth was a member of the prominent 19th century Booth theatrical family from Maryland and, by the 1860s, was a well-known actor...

and President James A. Garfield.)

Sickles was not court-martial

Court-martial

A court-martial is a military court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of members of the armed forces subject to military law, and, if the defendant is found guilty, to decide upon punishment.Most militaries maintain a court-martial system to try cases in which a breach of...

ed for insubordination after Gettysburg because he had been wounded, and it was assumed he would stay out of trouble. Furthermore, he was a powerful, politically connected man who would not accept being disciplined without protest and retribution.

Sickles ran a vicious campaign against General Meade's character after the Civil War. Sickles felt that Meade had wronged him at Gettysburg and that credit for winning the battle belonged to him. In anonymous newspaper articles and in testimony before a congressional committee, Sickles maintained that Meade had secretly planned to retreat from Gettysburg on the first day. While his movement away from Cemetery Ridge may have violated orders, Sickles always asserted that it was the correct move because it disrupted the Confederate attack, redirecting its thrust, effectively shielding their real objectives, Cemetery Ridge and Cemetery Hill

Cemetery Hill

Cemetery Hill is a Gettysburg Battlefield landform which had 1863 military engagements each day of the July 1–3 Battle of Gettysburg. The northernmost part of the Army of the Potomac defensive "fish-hook" line, the hill is gently sloped and provided a site for American Civil War artillery...

. Sickles' redeployment did in fact take Confederate commanders by surprise, and historians have argued about the real ramifications ever since.

Sickles eventually received the Medal of Honor

Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor is the highest military decoration awarded by the United States government. It is bestowed by the President, in the name of Congress, upon members of the United States Armed Forces who distinguish themselves through "conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his or her...

for his actions, although it took him 34 years to get it. The official citation that accompanied his medal recorded that Sickles "displayed most conspicuous gallantry on the field, vigorously contesting the advance of the enemy and continuing to encourage his troops after being himself severely wounded."

Postbellum career

Despite his one-legged disability, Sickles remained in the army until the end of the war and was disgusted that Lieutenant General Ulysses S. GrantUlysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant was the 18th President of the United States as well as military commander during the Civil War and post-war Reconstruction periods. Under Grant's command, the Union Army defeated the Confederate military and ended the Confederate States of America...

would not allow him to return to a combat command. In 1867, he received appointments as brevet

Brevet (military)

In many of the world's military establishments, brevet referred to a warrant authorizing a commissioned officer to hold a higher rank temporarily, but usually without receiving the pay of that higher rank except when actually serving in that role. An officer so promoted may be referred to as being...

brigadier general and major general in the regular army for his services at Fredericksburg and Gettysburg, respectively.

Soon after the close of the Civil War, in 1865, he was sent on a confidential mission to Colombia

Colombia

Colombia, officially the Republic of Colombia , is a unitary constitutional republic comprising thirty-two departments. The country is located in northwestern South America, bordered to the east by Venezuela and Brazil; to the south by Ecuador and Peru; to the north by the Caribbean Sea; to the...

(the "special mission to the South American Republics") to secure its compliance with a treaty agreement of 1846 permitting the United States to convey troops across the Isthmus of Panama

Isthmus of Panama

The Isthmus of Panama, also historically known as the Isthmus of Darien, is the narrow strip of land that lies between the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, linking North and South America. It contains the country of Panama and the Panama Canal...

. From 1865 to 1867, he commanded the Department of South Carolina, the Department of the Carolinas, the Department of the South, and the Second Military District

Second Military District

The Second Military District existed in the American South during the Reconstruction era that followed the American Civil War included North and South Carolina. Originally commanded by General Daniel E. Sickles, after his removal by President Andrew Johnson on August 26, 1867, General Edward Canby...

. In 1866, he was appointed colonel of the 42nd U.S. Infantry (Veteran Reserve Corps

Veteran Reserve Corps

The Veteran Reserve Corps was a military reserve organization created within the Union Army during the American Civil War to allow partially disabled or otherwised infirmed soldiers to perform light duty, freeing able-bodied soldiers to serve on the front lines.-The Invalid Corps:The corps was...

), and in 1869 he was retired with the rank of major general.

Sickles served as U.S. Minister to Spain

United States Ambassador to Spain

-Ambassadors:*John Jay**Appointed: September 29, 1779**Title: Minister Plenipotentiary**Presented credentials:**Terminated mission: ~May 20, 1782*William Carmichael**Appointed: April 20, 1790**Title: Chargé d'Affaires...

from 1869 to 1874, after the Senate failed to confirm Henry Shelton Sanford

Henry Shelton Sanford

Henry Shelton Sanford was an American diplomat and businessman who founded the city of Sanford, Florida.-Early life:Sanford was born in Woodbury, Connecticut into a family with deep New England roots...

to the post, and took part in the negotiations growing out of the Virginius Affair

Virginius Affair

The Virginius Affair was a diplomatic dispute that occurred in the 1870s between the United States, the United Kingdom and Spain, then in control of Cuba, during the Ten Years' War....

. His inaccurate and emotional messages to Washington promoted war, until he was overruled by Secretary of State Hamilton Fish

Hamilton Fish

Hamilton Fish was an American statesman and politician who served as the 16th Governor of New York, United States Senator and United States Secretary of State. Fish has been considered one of the best Secretary of States in the United States history; known for his judiciousness and reform efforts...

and the war scare died out.

Sickles maintained his reputation as a ladies' man in the Spanish royal court and was rumored to have had an affair with the deposed Queen Isabella II

Isabella II of Spain

Isabella II was the only female monarch of Spain in modern times. She came to the throne as an infant, but her succession was disputed by the Carlists, who refused to recognise a female sovereign, leading to the Carlist Wars. After a troubled reign, she was deposed in the Glorious Revolution of...

. Following the death of Teresa in 1867, in 1871, he married Senorita Carmina Creagh, the daughter of Chevalier de Creagh of Madrid, a Spanish Councillor of State. They had two children.

Sickles was president of the New York State Board of Civil Service Commissioners from 1888 to 1889, sheriff of New York

New York City Sheriff's Office

The New York City Sheriff's Office is the civil law enforcement division of the New York City Department of Finance. The Sheriff's office is headed by a sheriff, who is appointed to the position by the mayor, unlike most sheriffs in New York State who are elected officials...

in 1890, and again a representative in the 53rd Congress from 1893 to 1895. For most of his postwar life, he was the chairman of the New York Monuments Commission

New York Monuments Commission

The New York Monuments Commission for the Battlefields of Gettysburg, Chattanooga and Antietam was a commission set up by New York State to honor the dead from Battle of Gettysburg, Battle of Chattanooga and Battle of Antietam. General Daniel Edgar Sickles served as chairman until forced out over...

, but he was forced out when $27,000 was found to have been embezzled.

He had an important part in efforts to preserve the Gettysburg Battlefield

Gettysburg Battlefield

The Gettysburg Battlefield is the area of the July 1–3, 1863, military engagements of the Battle of Gettysburg within and around the borough of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Locations of military engagements extend from the 4 acre site of the first shot & at on the west of the borough, to East...

, sponsoring legislation to form the Gettysburg National Military Park

Gettysburg National Military Park

The Gettysburg National Military Park is an administrative unit of the National Park Service's northeast region and a subunit of federal properties of Adams County, Pennsylvania, with the same name, including the Gettysburg National Cemetery...

, buy up private lands, and erect monuments. One of his contributions was procuring the original fencing used on East Cemetery Hill to mark the park's borders. This fencing came directly from Lafayette Square

Lafayette Square

Lafayette Square may refer to a place in the United States:*Lafayette Square, Los Angeles, California, a neighborhood in the mid-city section of L.A.*Lafayette Square, New Orleans, Louisiana, in the Central Business District*Lafayette Square, St...

in Washington, D.C. (site of the Key shooting). Of the principal senior generals who fought at Gettysburg, virtually all, with the conspicuous exception of Sickles, have been memorialized with statues at Gettysburg. When asked why there was no memorial to him, Sickles supposedly said, "The entire battlefield is a memorial to Dan Sickles." However, there was, in fact, a memorial commissioned to include a bust of Sickles, the monument to the New York Excelsior Brigade. It was rumored that the money appropriated for the bust was stolen by Sickles himself; the monument is displayed in the Peach Orchard with a figure of an eagle instead of Sickles' likeness.

Death

Sickles lived out the remainder of his life in New York CityNew York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

, dying on May 3, 1914. His funeral was held at St. Patrick's Cathedral in Manhattan on May 8, 1914. He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington County, Virginia, is a military cemetery in the United States of America, established during the American Civil War on the grounds of Arlington House, formerly the estate of the family of Confederate general Robert E. Lee's wife Mary Anna Lee, a great...

.

In popular media

Sickles appears prominently in the books Gettysburg and Grant Comes East, the first two books of the alternate historyAlternate history (fiction)

Alternate history or alternative history is a genre of fiction consisting of stories that are set in worlds in which history has diverged from the actual history of the world. It can be variously seen as a sub-genre of literary fiction, science fiction, and historical fiction; different alternate...

Civil War trilogy by Newt Gingrich

Newt Gingrich

Newton Leroy "Newt" Gingrich is a U.S. Republican Party politician who served as the House Minority Whip from 1989 to 1995 and as the 58th Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives from 1995 to 1999....

and William R. Forstchen

William R. Forstchen

William R. Forstchen is an American author who began publishing in 1983 with the novel Ice Prophet. He is a Professor of History and Faculty Fellow at Montreat College, in Montreat, North Carolina...

.

Medal of Honor citation

- Rank and organization: Major General, U.S. Volunteers

- Place and Date: At Gettysburg, Pa., July 2, 1863.

- Entered Service At: New York, N.Y.

- Birth: New York, N.Y.

- Date of Issue: October 30, 1897.

Citation:

- Displayed most conspicuous gallantry on the field vigorously contesting the advance of the enemy and continuing to encourage his troops after being himself severely wounded.

See also

- List of American Civil War generals

- List of American Civil War Medal of Honor recipients: Q–S

- List of U.S. political appointments that crossed party lines

Further reading

- Bradford, Richard H. The Virginius Affair. Boulder: Colorado Associated University Press, 1980. ISBN 0-87081-080-4.

- Brandt, Nat. The Congressman Who Got Away With Murder. Syracuse, NY: University of Syracuse Press, 1991. ISBN 0-8156-0251-0.

- Hessler, James A. Sickles at Gettysburg: The Controversial Civil War General Who Committed Murder, Abandoned Little Round Top, and Declared Himself the Hero of Gettysburg. New York: Savas Beatie, 2009. ISBN 978-1-932714-64-7.