History of the United States (1945–1964)

Encyclopedia

For the United States

, 1945 to 1964 was an era of economic growth and prosperity which saw the victorious powers of World War II confronting each other in the Cold War

and the triumph of the Civil Rights Movement

that ended Jim Crow segregation in the South.

The period saw an active foreign policy designed to rescue Europe and Asia from the devastation of World War II

and to contain the expansion of Communism

, represented by the Soviet Union

and China. A race began to overawe the other side with more powerful nuclear weapons. The Soviets formed the Warsaw Pact

of communist states to oppose the American-led North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) alliance. The U.S. fought a bloody, inconclusive war in Korea

and was escalating the war in Vietnam

as the period ended.

On the domestic front, after a short transition, the economy grew rapidly, with widespread prosperity, rising wages, and the movement of most of the remaining farmers to the towns and cities. Politically, the era was dominated by presidents, Democrats Harry Truman (1945–53), John F. Kennedy

(1961–63) and Lyndon Johnson (1963–69), and Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower

(1953–61). For most of the period, the Democrats controlled Congress; however, they were usually unable to pass as much liberal legislation as they had hoped because of the power of the Conservative Coalition

. The Liberal coalition

came to power after Kennedy's assassination in 1963, and launched the Great Society

.

. Aside from a few minor adjustments, this would be the "Iron Curtain

" of the Cold War. With the onset of the Cold War in Europe in 1947, the East-West lines stabilized (except that Yugoslavia broke with the Soviets and gained American support). In Asia, however, there was much more movement as the Communists took over China

in 1949 and attempted to take over all of Korea (1950) and Vietnam (1954). Communist hegemony covered one third of the world's land while the United States emerged as the world's more influential superpower, and formed a worldwide network of military alliances.

There were fundamental contrasts between the visions of the United States and the Soviet Union, between capitalism with liberal democracy and totalitarian communism. The United States envisioned the new United Nations

as a Wilsonian

tool to resolve future troubles, but it failed in that purpose. The U.S. rejected totalitarianism and colonialism, in line with the principles laid down by the Atlantic Charter

of 1941: self-determination, equal economic access, and a rebuilt capitalist, democratic Europe that could again serve as a hub in world affairs.

The only major industrial power in the world whose economy emerged intact—and even greatly strengthened—was the United States. Although President Franklin D. Roosevelt

thought his personal relationship with Joseph Stalin

could dissolve future difficulties, President Truman was much more skeptical.

The Soviets, too, saw their vital interests in the containment or roll-back of capitalism near their borders. Joseph Stalin

was determined to absorb the Baltics, neutralize Finland and Austria, and set up pro-Moscow regimes in Poland, Romania, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, East Germany, and Bulgaria. He at first collaborated with Josip Broz Tito

in Yugoslavia, but then they became enemies., Stalin ignored his promises at Yalta (Feb. 1945) when he had promised that "free elections" would go ahead in Eastern Europe. Former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill

in 1946 condemned Stalin for cordoning off a new Russian empire with an "iron curtain

". Indeed the British government, under the Labour Party, was at first more anti-Communist than the U.S. Its economy was in bad shape, however, and it could no longer afford anti-Communist activity in Greece. It asked the U.S. to intervene there; Truman agreed with the Truman Doctrine

in 1947. After making large ad-hoc loans and gifts to the Europeans in 1945-47, the U.S. reorganized its foreign aid program in the Marshall Plan

, 1948–51, which gave $12 billion in gifts (and some loans) to help rebuild and modernize the West European economies. The Cold War

had begun and Stalin refused to allow his satellites to accept American aid. Both sides mobilized military alliances, with NATO in the west and the Warsaw Pact

in the east in operation by 1949.

of New York, and general Dwight D. Eisenhower

), but was opposed by the isolationists led by Senator Robert A. Taft of Ohio.

won control of mainland China in a civil war, proclaimed the People's Republic of China

, then traveled to Moscow where he negotiated the Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship. China had thus moved from a close ally of the U.S. to a bitter enemy, and the two fought each other starting in late 1950 in Korea. The Truman administration responded with a secret 1950 plan, NSC-68

, designed to confront the Communists with large-scale defense spending. The Russians had built an atomic bomb by 1950—much sooner than expected; Truman ordered the development of the Hydrogen bomb. Two of the spies

who gave atomic secrets to Russia were tried and executed.

France was hard-pressed by Communist insurgents in the First Indochina War

. The U.S. in 1950 started to fund the French effort on the proviso that the Vietnamese be given more autonomy.

n plan to invade U.S.-supported South Korea

in June 1950. President Truman immediately and unexpectedly implemented the containment policy by a full-scale commitment of American and UN forces to Korea. He did not consult or gain approval of Congress but did gain the approval of the United Nations

(UN) to drive back the North Koreans and re-unite that country in terms of a rollback

strategy

After a few weeks of retreat, General Douglas MacArthur

's success at the Battle of Inchon

turned the war around; UN forces invaded North Korea. This advantage was lost when hundreds of thousands of Chinese entered an undeclared war against the United States and pushed the US/UN/Korean forces back to the original starting line, the 38th parallel. The war became a stalemate, with over 33,000 American dead and 100,000 wounded but nothing to show for it except a resolve to continue the containment policy. Truman fired MacArthur but was unable to end the war. Dwight D. Eisenhower

in 1952 campaigned against Truman's failures of "Korea, Communism and Corruption," promising to go to Korea himself and end the war. By threatening to use nuclear weapons in 1953, Eisenhower ended the war with a truce that is still in effect.

in Congress passed the Taft Hartley Act, designed to balance the rights of management and unions, and delegitimizing Communist union leaders. The challenge of rooting out Communists from labor unions and the Democratic party was successfully undertaken by liberals, such as Walter Reuther

of the autoworkers union and Ronald Reagan

of the Screen Actors Guild (Reagan was a liberal Democrat at the time). Many of the purged leftists joined the presidential campaign in 1948 of FDR's Vice President Henry A. Wallace

.

The House Un-American Activities Committee

The House Un-American Activities Committee

, with young Congressman Richard M. Nixon playing a central role, accused Alger Hiss

, a top Roosevelt aide, of being a Communist spy, using testimony and documents provided by Whittaker Chambers

. Hiss was convicted and sent to prison, with the anti-Communists gaining a powerful political weapon. It launched Nixon's meteoric rise to the Senate (1950) and the vice presidenncy (1952).

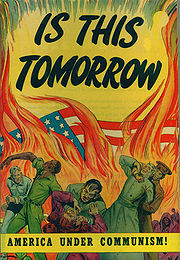

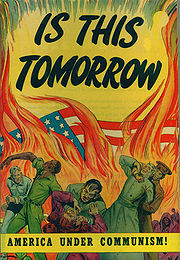

With anxiety over Communism in Korea and China reaching fever pitched in 1950, a previously obscure Senator, Joe McCarthy of Wisconsin, launched Congressional investigations into the cover-up of spies in the government. McCarthy dominated the media, and used reckless allegations and tactics that allowed his opponents to effectively counterattack. Irish Catholics (including conservative wunderkind William F. Buckley, Jr.

and the Kennedy Family

) were intensely anti-Communist and defended McCarthy (a fellow Irish Catholic). Paterfamilias Joseph Kennedy (1888–1969), a very active conservative Democrat, was McCarthy's most ardent supporter and got his son Robert F. Kennedy

a job with McCarthy. McCarthy had talked of "twenty years of treason" (i.e. since Roosevelt's election in 1932). When he in 1953 he started talking of "21 years of treason and launched a major attack on the Army for promoting a Communist dentist in the medical corps, his recklessness was too much for Eisenhower, who encouraged Republicans to censure McCarthy formally in 1954. The Senator's power collapsed overnight. Senator John F. Kennedy

did not vote for censure. Buckley went on to found the National Review

in 1955 as a weekly magazine that helped define the conservative position on public issues.

McCarthy and McCarthyism was always of far more importance to liberals than conservatives. He became a liberal target, and made liberals look like the innocent victims. "McCarthyism" was expanded to include attacks on supposed Communist influence in Hollywood, which resulted in a black-list whereby artists who refused to testify about possible Communist connections could not get work. Some famous celebrities (such as Charlie Chaplin

) left the U.S.; other worked under pseudonyms (such as Dalton Trumbo

). McCarthyism included investigations into academics and teachers as well.

In 1953, Stalin died, and after new 1952 presidential election, President

In 1953, Stalin died, and after new 1952 presidential election, President

Dwight D. Eisenhower used the opportunity to end the Korean War, while continuing Cold War policies. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles

was the dominant figure in the nation's foreign policy in the 1950s. Dulles denounced the "containment" of the Truman administration and espoused an active program of "liberation", which would lead to a "rollback

" of communism. The most prominent of those doctrines was the policy of "massive retaliation

", which Dulles announced early in 1954, eschewing the costly, conventional ground forces characteristic of the Truman administration in favor of wielding the vast superiority of the U.S. nuclear arsenal and covert intelligence

. Dulles defined this approach as "brinkmanship

".

A dramatic and unexpected shock to Americans' self-confidence and its technological superiority came in 1957, when the Soviets beat the United States into outer space by launching Sputnik, the first earth satellite. The space race began, and by the early 1960s the United States had forged ahead, with President Kennedy promising to land a man on the moon by the end of the 1960s—the landing indeed took place on July 20, 1969.

Trouble close to home appeared when the Soviets formed an alliance with Cuba

after Fidel Castro

's successful revolution in 1959

.

East Germany was the weak point in the Soviet empire, with refugees leaving for the West by the thousands every week. The Soviet solution came in 1961, with the Berlin Wall

to stop East Germans from fleeing communism. This was a major propaganda setback for the USSR, but it did allow them to keep control of East Berlin.

The Communist world split in half, as China turned against the Soviet Union

; Mao denounced Khrushchev for going soft on capitalism. However, the US failed to take advantage of this split until President Richard Nixon

saw the opportunity in 1969. In 1958, the U.S. sent troops into Lebanon

for nine months to stabilize a country on the verge of civil war. Between 1954 and 1961, Eisenhower dispatched large sums of economic and military aid and 695 military advisers to South Vietnam

to stabilize the pro-western government under attack by insurgents. Eisenhower supported CIA efforts to undermine anti-American governments, which proved most successful in Iran and Guatemala.

The first major strain among the NATO alliance occurred in 1956 when Eisenhower forced Britain and France to retreat from their invasion of Egypt

(with Israel

) which was intended to get back their ownership of the Suez Canal

. Instead of supporting the claims of its NATO partners, the Eisenhower administration stated that it opposed French and British imperial adventurism in the region by sheer prudence, fearing that Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser

's standoff with the region's old colonial powers would bolster Soviet power in the region.

The Cold War reached its most dangerous point during the Kennedy administration in the Cuban Missile Crisis

, a tense confrontation between the Soviet Union and the United States over the Soviet deployment of nuclear missiles in Cuba. The crisis began on October 16, 1962, and lasted for thirteen days. It was the moment when the Cold War was closest to exploding into a devastating nuclear exchange between the two superpower nations. Kennedy decided not to invade or bomb Cuba but to institute a naval blockade of the island. The crisis ended in a compromise, with the Soviets removing their missiles publicly, and the United States secretly removing its nuclear missiles in Turkey. In Moscow, Communist leaders removed Nikita Khrushchev

because of his reckless behavior.

The American economy grew dramatically in the post-war period, expanding at a rate of 3.5% per annum between 1945 and 1970. During this period of prosperity, many incomes doubled in a generation, described by economist Frank Levy

as “upward mobility on a rocket ship.” The substantial increase in average family income within a generation resulted in millions of office and factory workers being lifted into a growing middle class, enabling them to sustain a standard of living once considered to be reserved for the wealthy. As noted by Deone Zell, assembly line work paid well, while unionized factory jobs served as “stepping-stones to the middle class.” By 1960, blue-collar workers had become the biggest buyers of amny luxury goods and services. In addition, by the early Seventies, post-World War II American consumers enjoyed higher levels of disposable income than those in any other country.

The great majority of American workers who had stable jobs were well off financially, while even non-union jobs were associated with rising paychecks, benefits, and obtained many of the advantages that characterized union work. An upscale working class came into being, as American blue-collar workers came to enjoy the benefits of home ownership, while high wages provided blue-collar workers with the ability to pay for new cars, household appliances, and regular vacations. By the 1960s, a blue-collar worker earned more than a manager did in the Forties, despite the fact that his relative position within the income distribution had not changed.

As noted by the historian Nancy Wierek:

"In the postwar period, the majority of Americans were affluent in the sense that they were in a position to spend money on many things they wanted, desired, or chose to have, rather than on necessities alone.”

As argued by the historians Ronald Edsforth

and Larry Bennett:

"By the mid-1960’s, the majority of America’s organized working class who were not victims of the second Red Scare embraced, or at least tolerated, anti-communism because it was an integral part of the New American Dream to which they had committed their lives. Theirs was not an unobtainable dream; nor were their lives empty because of it. Indeed, for at least a quarter of century, the material promises of consumer-oriented Americanism were fulfilled in improvements in everyday life that made them the most affluent working class in American history.”

Between 1946 and 1960, the United States witnessed a significant expansion in the consumption of goods and services. GNP rose by 36% and personal consumption expenditures by 42%, cumulative gains which were reflected in the incomes of families and unrelated individuals. While the number of these units rose sharply from 43.3 million to 56.1 million in 1960, a rise of almost 23%, their average incomes grew even faster, from $3940 in 1946 to $6900 in 1960, an increase of 43%. After taking inflation into account, the real advance was 16%. The dramatic rise in the average American standard of living was such that, according to sociologist George Katona

:

More than 21 million housing units were constructed between 1946 and 1960, and in the latter year 52% of consumer units in the metropolitan areas owned their own homes. In 1957, out of all the wired homes throughout the country, 96% had a refrigerator, 87% an electric washer, 81% a television, 67% a vacuum cleaner, 18% a freezer, 12% an electric or gas dryer, and 8% air conditioning. Car ownership also soared, with 72% of consumer units owning an automobile by 1960.

The period from 1946 to 1960 also witnessed a significant increase in the paid leisure time of working people. The forty-hour workweek established by the Fair Labor Standards Act in covered industries became the actual schedule in most workplaces by 1960, while uncovered workers such as farmworkers and the self-employed worked less hours than they had done previously, although they still worked much longer hours than most other workers. Paid vacations also became to be enjoyed by the vast majority of workers, with 91% of blue-collar workers covered by major collective bargaining agreements receiving paid vacations by 1957 (usually to a maximum of three weeks), while by the early Sixties virtually all industries paid for holidays and most did so for seven days a year. Industries catering to leisure activities blossomed as a result of most Americans enjoying significant paid leisure time by 1960, while average blue-collar and white-collar workers had come to expect to hold on to their jobs for life. Educational outlays were also greater than in other countries while a higher proportion of young people were graduating from high schools and universities than elsewhere in the world, as hundreds of new colleges and universities opened every year. Tuition was kept low--it was free at California state universities.At the advanced level American science, engineering and medicine was world famous. By the mid-Sixties, the majority of American workers enjoyed the highest wage levels in the world, and by the late Sixties, the great majority of Americans were richer than people in other countries, except Sweden, Switzerland, and Canada. Educational outlays were also greater than in other countries while a higher proportion of young people was at school and college than elsewhere in the world. As noted by the historian John Vaizey:

“To strike a balance with the Soviet Union, it would be easy to say that all but the very poorest Americans were better off than the Russians, that education was better but the health service worse, but that above all the Americans had freedom of expression and democratic institutions.”

In regards to social welfare, the postwar era saw a considerable improvement in insurance for workers and their dependents against the risks of illness, as private insurance programs like Blue Cross and Blue Shield expanded. With the exception of farm and domestic workers, virtually all members of the labor force were covered by Social Security. In 1959 that about two-thirds of the factory workers and three-fourths of the office workers were provided with supplemental private pension plans. In addition 86% of factory workers and 83% of office had jobs that covered for hospital insurance while 59% and 61% had additional insurance for doctors.

At the center of middle-class culture in the 1950s was a growing demand for consumer goods; a result of the postwar prosperity, the increase in variety and availability of consumer products, and television advertising. America generated a steadily growing demand for better automobiles, clothing, appliances, family vacations and higher education.

began a national trend with his use of mass-production techniques to construct a large "Levittown

" housing development on Long Island

. Meanwhile, the suburban population swelled because of the baby boom. Suburbs provided larger homes for larger families, security from urban living, privacy, and space for consumer goods.

The new prosperity did not extend to everyone. Many Americans continued to live in poverty throughout the 1950s especially older people and blacks. As Socialist leader Michael Harrington

emphasized, there was still The Other America

. Poverty declined sharply in the Sixties, as the New Frontier

and Great Society

especially helped older people. The proportion below the poverty line fell almost in half from 22% in 1960 to 12% in 1970 and then leveled off.

1896 accepted segregation as constitutional. Voting rights discrimination remained widespread in the South

through the 1950s. Fewer than 10% voted in the Deep South, although a larger proportion voted in the border states, and the blacks were being organized into Democratic machines in the northern cities. Although both parties pledged progress in 1948, the only major development before 1954 was the integration military.

decisions in Brown v. Board of Education

of Topeka (1954); Powell v. Alabama

(1932); Smith v. Allwright

(1944); Shelley v. Kraemer

(1948); Sweatt v. Painter

(1950); and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents

(1950) led to a shift in tactics, and from 1955 to 1965, "direct action" was the strategy—primarily bus boycotts, sit-ins, freedom rides, and social movements.

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka was a landmark case of the United States Supreme Court which explicitly outlawed segregated public education facilities for blacks and whites, ruling so on the grounds that the doctrine of "separate but equal

" public education could never truly provide black Americans with facilities of the same standards available to white Americans. One hundred and one members of the United States House of Representatives

and 19 Senators

signed "The Southern Manifesto" condemning the Supreme Court decision as unconstitutional.

Governor Orval Eugene Faubus

of Arkansas

used the Arkansas National Guard to prevent school integration at Little Rock Central High School in 1957. President Eisenhower nationalized state forces and sent in the US Army to enforce federal court orders. Governors Ross Barnett

of Mississippi

and George Wallace

of Alabama

physically blocked school doorways at their respective states' universities. Birmingham's

public safety commissioner Eugene T. "Bull" Connor advocated violence against freedom riders and ordered fire hoses and police dogs turned on demonstrators. Sheriff Jim Clark

of Dallas County, Alabama

, loosed his deputies on "Bloody Sunday" marchers and personally menaced other protesters. Police all across the South arrested civil rights activists on trumped-up charges.

Although they had white supporters and sympathizers, the modern civil rights movement was designed, led, organized, and manned by African Americans, who placed themselves and their families on the front lines in the struggle for freedom. Their heroism was brought home to every American through newspaper, and later, television reports as their peaceful marches and demonstrations were violently attacked by law enforcement. Officers used batons, bullwhips, fire hoses, police dogs, and mass arrests to intimidate the protesters. The second characteristic of the movement is that it was not monolithic, led by one or two men. Rather it was a dispersed, grass-roots campaign that attacked segregation in many different places using many different tactics. While some groups and individuals within the civil rights movement—such as Malcolm X

Although they had white supporters and sympathizers, the modern civil rights movement was designed, led, organized, and manned by African Americans, who placed themselves and their families on the front lines in the struggle for freedom. Their heroism was brought home to every American through newspaper, and later, television reports as their peaceful marches and demonstrations were violently attacked by law enforcement. Officers used batons, bullwhips, fire hoses, police dogs, and mass arrests to intimidate the protesters. The second characteristic of the movement is that it was not monolithic, led by one or two men. Rather it was a dispersed, grass-roots campaign that attacked segregation in many different places using many different tactics. While some groups and individuals within the civil rights movement—such as Malcolm X

—advocated Black Power

, black separatism, or even armed resistance, the majority of participants remained committed to the principles of nonviolence, a deliberate decision by an oppressed minority to abstain from violence for political gain. Using nonviolent strategies, civil rights activists took advantage of emerging national network-news reporting, especially television, to capture national attention.

The leadership role of black churches in the movement was a natural extension of their structure and function. They offered members an opportunity to exercise roles denied them in society. Throughout history, the black church served as a place of worship and also as a base for powerful ministers, such as Congressman Adam Clayton Powell in New York City. The most prominent clergyman in the civil rights movement was Martin Luther King, Jr.

Time magazine's 1963 "Man of the Year" showed tireless personal commitment to black freedom and his strong leadership won him worldwide acclaim and the Nobel Peace Prize

.

Students and seminarians in both the South and the North

played key roles in every phase of the civil rights movement. Church and student-led movements developed their own organizational and sustaining structures. The Southern Christian Leadership Conference

(SCLC), founded in 1957, coordinated and raised funds, mostly from northern sources, for local protests and for the training of black leaders. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee

, or SNCC, founded in 1957, developed the "jail-no-bail" strategy. SNCC's role was to develop and link sit-in campaigns and to help organize freedom rides, voter registration drives, and other protest activities. These three new groups often joined forces with existing organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

(NAACP), founded in 1909, the Congress of Racial Equality

(CORE), founded in 1942, and the National Urban League

. The NAACP and its Director, Roy Wilkins

, provided legal counsel for jailed demonstrators, helped raise bail, and continued to test segregation and discrimination in the courts as it had been doing for half a century. CORE initiated the 1961 Freedom Rides which involved many SNCC members, and CORE's leader James Farmer

later became executive secretary of SNCC.

The administration of President John F. Kennedy

supported enforcement of desegregation in schools and public facilities. Attorney General Robert Kennedy brought more than 50 lawsuits in four states to secure black Americans' right to vote. However, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover

, concerned about possible communist influence in the civil rights movement and personally antagonistic to King, used the FBI to discredit King and other civil rights leaders.

, helped by his famous Whistle Stop Tour

of small town America. He used executive orders to end racial discrimination in the armed forces and created loyalty checks that dismissed thousands of communist fellow travelers from office. Truman's presidency was also eventful in foreign affairs

, with the defeat of Nazi Germany and his decision to use nuclear weapons against Japan

, the founding of the United Nations

, the Marshall Plan

to rebuild Europe, the Truman Doctrine

to contain communism, the beginning of the Cold War

, the Berlin Airlift, and the creation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). The defat of America's wartime ally in the Chinese Civil War

brought a hostile Communist regime to East Asia, and the US became bogged down fighting China in the Korean War

, 1950-53. Corruption in Truman's administration, which was linked to cabinet level appointees and senior White House staff, was a central issue in the 1952 presidential campaign

. Truman was forced to end his third term hopes by a poor showing in the 1952 primaries. drop out of his reelection. Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower

, the famous wartime general, won a landslide in the 1952 presidential election

by crusading against Truman's failures in terms of "Communism, Korea and Corruption."

rather than trying to roll it back

.

While frugal in budget matters he expanded Social Security and did not try to repeal the remaining New Deal

programs. He launched the interstate highway system (using a tax on gasoline) that dramatically improved the nation's transportation infrastructure. The economy was generally healthy, apart from a sharp economic recession in 1958. Ike remained popular and largely avoided partisan politics; he was easily reelected by a landslide in 1956.

In both foreign and domestic policy Eisenhower remained on friendly terms with the Democrats, who regained Congress in 1954 and made large gains in 1958. His farewell address to the nation warned of the dangers of a growing "military industrial complex."

against the Democrat John F. Kennedy

. Historians have explained Kennedy's victory in terms of an economic recession, the numerical dominance of 17 million more registered Democrats than Republicans, the votes that Kennedy gained among Catholics practically matched the votes Nixon gained among Protestants, Kennedy's better organization, and Kennedy's superior campaigning skills. Nixon's emphasis on his experience carried little weight, and he wasted energy by campaigning in all 50 states instead of concentrating on the swing states. Kennedy used his large, well-funded campaign organization to win the nomination, secure endorsements, and with the aid of the last of the big-city bosses to get out the vote in the big cities. He relied on Johnson to hold the South and used television effectively. Kennedy was the first Catholic to run for president since Al Smith

's ill-fated campaign in 1928. Voters were polarized on religious grounds, but Kennedy's election was a transforming event for Catholics, who finally realized they were accepted in a America, and it marked the virtual end of anti-Catholicism as a political force.

The Kennedy Family had long been leaders of the Irish Catholic wing of the Democratic Party; JFK was middle-of-the-road or liberal on domestic issues and conservative on foreign policy, sending military forces into Cuba and Vietnam. The Kennedy style called for youth, dynamism, vigor and an intellectual approach to aggressive new policies in foreign affairs. The downside was his inexperience in foreign affairs, standing in stark contrast to the vast experience of the president he replaced. He is best known for his call to civic virtue

: "And so, my fellow Americans: ask not what your country can do for you - ask what you can do for your country." In Congress the Conservative Coalition

blocked nearly all of Kennedy's domestic programs, so there were few changes in domestic policy, even as the civil rights movement gained momentum.

President Kennedy was assassinated

in Dallas, Texas, on November 22, 1963 by Lee Harvey Oswald

. The event proved to be one of the greatest psychological shocks to the American people in the 20th century and lead to Kennedy being revered as a martyr and hero.

Johnson used the full powers of the presidency to ensure passage the Civil Rights Act of 1964

. These actions helped Johnson to win a historic landslide in the 1964 presidential election over conservative champion Senator Barry Goldwater

. Johnson's big victory brought an overwhelming liberal majority in Congress.

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

, 1945 to 1964 was an era of economic growth and prosperity which saw the victorious powers of World War II confronting each other in the Cold War

Cold War

The Cold War was the continuing state from roughly 1946 to 1991 of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition between the Communist World—primarily the Soviet Union and its satellite states and allies—and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States...

and the triumph of the Civil Rights Movement

African-American Civil Rights Movement (1955-1968)

The African-American Civil Rights Movement refers to the movements in the United States aimed at outlawing racial discrimination against African Americans and restoring voting rights to them. This article covers the phase of the movement between 1955 and 1968, particularly in the South...

that ended Jim Crow segregation in the South.

The period saw an active foreign policy designed to rescue Europe and Asia from the devastation of World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

and to contain the expansion of Communism

Communism

Communism is a social, political and economic ideology that aims at the establishment of a classless, moneyless, revolutionary and stateless socialist society structured upon common ownership of the means of production...

, represented by the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

and China. A race began to overawe the other side with more powerful nuclear weapons. The Soviets formed the Warsaw Pact

Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Treaty Organization of Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance , or more commonly referred to as the Warsaw Pact, was a mutual defense treaty subscribed to by eight communist states in Eastern Europe...

of communist states to oppose the American-led North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) alliance. The U.S. fought a bloody, inconclusive war in Korea

Korean War

The Korean War was a conventional war between South Korea, supported by the United Nations, and North Korea, supported by the People's Republic of China , with military material aid from the Soviet Union...

and was escalating the war in Vietnam

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War was a Cold War-era military conflict that occurred in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. This war followed the First Indochina War and was fought between North Vietnam, supported by its communist allies, and the government of...

as the period ended.

On the domestic front, after a short transition, the economy grew rapidly, with widespread prosperity, rising wages, and the movement of most of the remaining farmers to the towns and cities. Politically, the era was dominated by presidents, Democrats Harry Truman (1945–53), John F. Kennedy

John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald "Jack" Kennedy , often referred to by his initials JFK, was the 35th President of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963....

(1961–63) and Lyndon Johnson (1963–69), and Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower was the 34th President of the United States, from 1953 until 1961. He was a five-star general in the United States Army...

(1953–61). For most of the period, the Democrats controlled Congress; however, they were usually unable to pass as much liberal legislation as they had hoped because of the power of the Conservative Coalition

Conservative coalition

In the United States, the conservative coalition was an unofficial Congressional coalition bringing together the conservative majority of the Republican Party and the conservative, mostly Southern, wing of the Democratic Party...

. The Liberal coalition

Liberal coalition

The Liberal coalition was a political grouping in the United States from the 1940s to the 1970s which promoted Modern liberalism in the United States.-Leaders:Important leaders included:*President Harry S. Truman...

came to power after Kennedy's assassination in 1963, and launched the Great Society

Great Society

The Great Society was a set of domestic programs in the United States promoted by President Lyndon B. Johnson and fellow Democrats in Congress in the 1960s. Two main goals of the Great Society social reforms were the elimination of poverty and racial injustice...

.

Origins

When the war ended in Europe on May 8, 1945, Soviet and Western (U.S., British, and French) troops were located along a line through the center of GermanyGermany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

. Aside from a few minor adjustments, this would be the "Iron Curtain

Iron Curtain

The concept of the Iron Curtain symbolized the ideological fighting and physical boundary dividing Europe into two separate areas from the end of World War II in 1945 until the end of the Cold War in 1989...

" of the Cold War. With the onset of the Cold War in Europe in 1947, the East-West lines stabilized (except that Yugoslavia broke with the Soviets and gained American support). In Asia, however, there was much more movement as the Communists took over China

History of China

Chinese civilization originated in various regional centers along both the Yellow River and the Yangtze River valleys in the Neolithic era, but the Yellow River is said to be the Cradle of Chinese Civilization. With thousands of years of continuous history, China is one of the world's oldest...

in 1949 and attempted to take over all of Korea (1950) and Vietnam (1954). Communist hegemony covered one third of the world's land while the United States emerged as the world's more influential superpower, and formed a worldwide network of military alliances.

There were fundamental contrasts between the visions of the United States and the Soviet Union, between capitalism with liberal democracy and totalitarian communism. The United States envisioned the new United Nations

United Nations

The United Nations is an international organization whose stated aims are facilitating cooperation in international law, international security, economic development, social progress, human rights, and achievement of world peace...

as a Wilsonian

Wilsonian

Wilsonianism or Wilsonian are words used to describe a certain type of ideological perspectives on foreign policy. The term comes from the ideology of United States President Woodrow Wilson and his famous Fourteen Points that he believed would help create world peace if implemented.Common...

tool to resolve future troubles, but it failed in that purpose. The U.S. rejected totalitarianism and colonialism, in line with the principles laid down by the Atlantic Charter

Atlantic Charter

The Atlantic Charter was a pivotal policy statement first issued in August 1941 that early in World War II defined the Allied goals for the post-war world. It was drafted by Britain and the United States, and later agreed to by all the Allies...

of 1941: self-determination, equal economic access, and a rebuilt capitalist, democratic Europe that could again serve as a hub in world affairs.

The only major industrial power in the world whose economy emerged intact—and even greatly strengthened—was the United States. Although President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt , also known by his initials, FDR, was the 32nd President of the United States and a central figure in world events during the mid-20th century, leading the United States during a time of worldwide economic crisis and world war...

thought his personal relationship with Joseph Stalin

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

could dissolve future difficulties, President Truman was much more skeptical.

The Soviets, too, saw their vital interests in the containment or roll-back of capitalism near their borders. Joseph Stalin

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

was determined to absorb the Baltics, neutralize Finland and Austria, and set up pro-Moscow regimes in Poland, Romania, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, East Germany, and Bulgaria. He at first collaborated with Josip Broz Tito

Josip Broz Tito

Marshal Josip Broz Tito – 4 May 1980) was a Yugoslav revolutionary and statesman. While his presidency has been criticized as authoritarian, Tito was a popular public figure both in Yugoslavia and abroad, viewed as a unifying symbol for the nations of the Yugoslav federation...

in Yugoslavia, but then they became enemies., Stalin ignored his promises at Yalta (Feb. 1945) when he had promised that "free elections" would go ahead in Eastern Europe. Former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

in 1946 condemned Stalin for cordoning off a new Russian empire with an "iron curtain

Iron Curtain

The concept of the Iron Curtain symbolized the ideological fighting and physical boundary dividing Europe into two separate areas from the end of World War II in 1945 until the end of the Cold War in 1989...

". Indeed the British government, under the Labour Party, was at first more anti-Communist than the U.S. Its economy was in bad shape, however, and it could no longer afford anti-Communist activity in Greece. It asked the U.S. to intervene there; Truman agreed with the Truman Doctrine

Truman Doctrine

The Truman Doctrine was a policy set forth by U.S. President Harry S Truman in a speech on March 12, 1947 stating that the U.S. would support Greece and Turkey with economic and military aid to prevent their falling into the Soviet sphere...

in 1947. After making large ad-hoc loans and gifts to the Europeans in 1945-47, the U.S. reorganized its foreign aid program in the Marshall Plan

Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan was the large-scale American program to aid Europe where the United States gave monetary support to help rebuild European economies after the end of World War II in order to combat the spread of Soviet communism. The plan was in operation for four years beginning in April 1948...

, 1948–51, which gave $12 billion in gifts (and some loans) to help rebuild and modernize the West European economies. The Cold War

Cold War

The Cold War was the continuing state from roughly 1946 to 1991 of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition between the Communist World—primarily the Soviet Union and its satellite states and allies—and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States...

had begun and Stalin refused to allow his satellites to accept American aid. Both sides mobilized military alliances, with NATO in the west and the Warsaw Pact

Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Treaty Organization of Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance , or more commonly referred to as the Warsaw Pact, was a mutual defense treaty subscribed to by eight communist states in Eastern Europe...

in the east in operation by 1949.

Containment

For NATO, containment of the expansion of Soviet influence became foreign policy doctrine; the expectation was that eventually the inefficient Soviet system would collapse of internal weakness, and no "hot" war (that is, one with large-scale combat) would be necessary. Containment was supported by Democrats and internationalist Republicans (led by Senator Arthur Vandenberg of Michigan, Governor Thomas DeweyThomas Dewey

Thomas Edmund Dewey was the 47th Governor of New York . In 1944 and 1948, he was the Republican candidate for President, but lost both times. He led the liberal faction of the Republican Party, in which he fought conservative Ohio Senator Robert A. Taft...

of New York, and general Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower was the 34th President of the United States, from 1953 until 1961. He was a five-star general in the United States Army...

), but was opposed by the isolationists led by Senator Robert A. Taft of Ohio.

1949-53

In 1949, the communist leader Mao ZedongMao Zedong

Mao Zedong, also transliterated as Mao Tse-tung , and commonly referred to as Chairman Mao , was a Chinese Communist revolutionary, guerrilla warfare strategist, Marxist political philosopher, and leader of the Chinese Revolution...

won control of mainland China in a civil war, proclaimed the People's Republic of China

People's Republic of China

China , officially the People's Republic of China , is the most populous country in the world, with over 1.3 billion citizens. Located in East Asia, the country covers approximately 9.6 million square kilometres...

, then traveled to Moscow where he negotiated the Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship. China had thus moved from a close ally of the U.S. to a bitter enemy, and the two fought each other starting in late 1950 in Korea. The Truman administration responded with a secret 1950 plan, NSC-68

NSC-68

National Security Council Report 68 was a 58-page formerly-classified report issued by the United States National Security Council on April 14, 1950, during the presidency of Harry S. Truman. Written during the formative stage of the Cold War, it was top secret until the 1970s when it was made...

, designed to confront the Communists with large-scale defense spending. The Russians had built an atomic bomb by 1950—much sooner than expected; Truman ordered the development of the Hydrogen bomb. Two of the spies

Julius and Ethel Rosenberg

Ethel Greenglass Rosenberg and Julius Rosenberg were American communists who were convicted and executed in 1953 for conspiracy to commit espionage during a time of war. The charges related to their passing information about the atomic bomb to the Soviet Union...

who gave atomic secrets to Russia were tried and executed.

France was hard-pressed by Communist insurgents in the First Indochina War

First Indochina War

The First Indochina War was fought in French Indochina from December 19, 1946, until August 1, 1954, between the French Union's French Far East...

. The U.S. in 1950 started to fund the French effort on the proviso that the Vietnamese be given more autonomy.

Korean War

Stalin approved a North KoreaNorth Korea

The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea , , is a country in East Asia, occupying the northern half of the Korean Peninsula. Its capital and largest city is Pyongyang. The Korean Demilitarized Zone serves as the buffer zone between North Korea and South Korea...

n plan to invade U.S.-supported South Korea

South Korea

The Republic of Korea , , is a sovereign state in East Asia, located on the southern portion of the Korean Peninsula. It is neighbored by the People's Republic of China to the west, Japan to the east, North Korea to the north, and the East China Sea and Republic of China to the south...

in June 1950. President Truman immediately and unexpectedly implemented the containment policy by a full-scale commitment of American and UN forces to Korea. He did not consult or gain approval of Congress but did gain the approval of the United Nations

United Nations

The United Nations is an international organization whose stated aims are facilitating cooperation in international law, international security, economic development, social progress, human rights, and achievement of world peace...

(UN) to drive back the North Koreans and re-unite that country in terms of a rollback

Rollback

In political science, rollback is the strategy of forcing change in the major policies of a state, usually by replacing its ruling regime. It contrasts with containment, which means preventing the expansion of that state; and with détente, which means a working relationship with that state...

strategy

After a few weeks of retreat, General Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur

General of the Army Douglas MacArthur was an American general and field marshal of the Philippine Army. He was a Chief of Staff of the United States Army during the 1930s and played a prominent role in the Pacific theater during World War II. He received the Medal of Honor for his service in the...

's success at the Battle of Inchon

Battle of Inchon

The Battle of Inchon was an amphibious invasion and battle of the Korean War that resulted in a decisive victory and strategic reversal in favor of the United Nations . The operation involved some 75,000 troops and 261 naval vessels, and led to the recapture of the South Korean capital Seoul two...

turned the war around; UN forces invaded North Korea. This advantage was lost when hundreds of thousands of Chinese entered an undeclared war against the United States and pushed the US/UN/Korean forces back to the original starting line, the 38th parallel. The war became a stalemate, with over 33,000 American dead and 100,000 wounded but nothing to show for it except a resolve to continue the containment policy. Truman fired MacArthur but was unable to end the war. Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower was the 34th President of the United States, from 1953 until 1961. He was a five-star general in the United States Army...

in 1952 campaigned against Truman's failures of "Korea, Communism and Corruption," promising to go to Korea himself and end the war. By threatening to use nuclear weapons in 1953, Eisenhower ended the war with a truce that is still in effect.

Anti-Communism and McCarthyism: 1947-54

In 1947, well before McCarthy became active, the Conservative CoalitionConservative coalition

In the United States, the conservative coalition was an unofficial Congressional coalition bringing together the conservative majority of the Republican Party and the conservative, mostly Southern, wing of the Democratic Party...

in Congress passed the Taft Hartley Act, designed to balance the rights of management and unions, and delegitimizing Communist union leaders. The challenge of rooting out Communists from labor unions and the Democratic party was successfully undertaken by liberals, such as Walter Reuther

Walter Reuther

Walter Philip Reuther was an American labor union leader, who made the United Automobile Workers a major force not only in the auto industry but also in the Democratic Party in the mid 20th century...

of the autoworkers union and Ronald Reagan

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan was the 40th President of the United States , the 33rd Governor of California and, prior to that, a radio, film and television actor....

of the Screen Actors Guild (Reagan was a liberal Democrat at the time). Many of the purged leftists joined the presidential campaign in 1948 of FDR's Vice President Henry A. Wallace

Henry A. Wallace

Henry Agard Wallace was the 33rd Vice President of the United States , the Secretary of Agriculture , and the Secretary of Commerce . In the 1948 presidential election, Wallace was the nominee of the Progressive Party.-Early life:Henry A...

.

House Un-American Activities Committee

The House Committee on Un-American Activities or House Un-American Activities Committee was an investigative committee of the United States House of Representatives. In 1969, the House changed the committee's name to "House Committee on Internal Security"...

, with young Congressman Richard M. Nixon playing a central role, accused Alger Hiss

Alger Hiss

Alger Hiss was an American lawyer, government official, author, and lecturer. He was involved in the establishment of the United Nations both as a U.S. State Department and U.N. official...

, a top Roosevelt aide, of being a Communist spy, using testimony and documents provided by Whittaker Chambers

Whittaker Chambers

Whittaker Chambers was born Jay Vivian Chambers and also known as David Whittaker Chambers , was an American writer and editor. After being a Communist Party USA member and Soviet spy, he later renounced communism and became an outspoken opponent later testifying in the perjury and espionage trial...

. Hiss was convicted and sent to prison, with the anti-Communists gaining a powerful political weapon. It launched Nixon's meteoric rise to the Senate (1950) and the vice presidenncy (1952).

With anxiety over Communism in Korea and China reaching fever pitched in 1950, a previously obscure Senator, Joe McCarthy of Wisconsin, launched Congressional investigations into the cover-up of spies in the government. McCarthy dominated the media, and used reckless allegations and tactics that allowed his opponents to effectively counterattack. Irish Catholics (including conservative wunderkind William F. Buckley, Jr.

William F. Buckley, Jr.

William Frank Buckley, Jr. was an American conservative author and commentator. He founded the political magazine National Review in 1955, hosted 1,429 episodes of the television show Firing Line from 1966 until 1999, and was a nationally syndicated newspaper columnist. His writing was noted for...

and the Kennedy Family

Kennedy family

In the United States, the phrase Kennedy family commonly refers to the family descending from the marriage of the Irish-Americans Joseph P. Kennedy, Sr. and Rose Elizabeth Fitzgerald that was prominent in American politics and government. Their political involvement has revolved around the...

) were intensely anti-Communist and defended McCarthy (a fellow Irish Catholic). Paterfamilias Joseph Kennedy (1888–1969), a very active conservative Democrat, was McCarthy's most ardent supporter and got his son Robert F. Kennedy

Robert F. Kennedy

Robert Francis "Bobby" Kennedy , also referred to by his initials RFK, was an American politician, a Democratic senator from New York, and a noted civil rights activist. An icon of modern American liberalism and member of the Kennedy family, he was a younger brother of President John F...

a job with McCarthy. McCarthy had talked of "twenty years of treason" (i.e. since Roosevelt's election in 1932). When he in 1953 he started talking of "21 years of treason and launched a major attack on the Army for promoting a Communist dentist in the medical corps, his recklessness was too much for Eisenhower, who encouraged Republicans to censure McCarthy formally in 1954. The Senator's power collapsed overnight. Senator John F. Kennedy

John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald "Jack" Kennedy , often referred to by his initials JFK, was the 35th President of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963....

did not vote for censure. Buckley went on to found the National Review

National Review

National Review is a biweekly magazine founded by the late author William F. Buckley, Jr., in 1955 and based in New York City. It describes itself as "America's most widely read and influential magazine and web site for conservative news, commentary, and opinion."Although the print version of the...

in 1955 as a weekly magazine that helped define the conservative position on public issues.

McCarthy and McCarthyism was always of far more importance to liberals than conservatives. He became a liberal target, and made liberals look like the innocent victims. "McCarthyism" was expanded to include attacks on supposed Communist influence in Hollywood, which resulted in a black-list whereby artists who refused to testify about possible Communist connections could not get work. Some famous celebrities (such as Charlie Chaplin

Charlie Chaplin

Sir Charles Spencer "Charlie" Chaplin, KBE was an English comic actor, film director and composer best known for his work during the silent film era. He became the most famous film star in the world before the end of World War I...

) left the U.S.; other worked under pseudonyms (such as Dalton Trumbo

Dalton Trumbo

James Dalton Trumbo was an American screenwriter and novelist, and one of the Hollywood Ten, a group of film professionals who refused to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1947 during the committee's investigation of Communist influences in the motion picture industry...

). McCarthyism included investigations into academics and teachers as well.

Eisenhower and Kennedy administrations

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

Dwight D. Eisenhower used the opportunity to end the Korean War, while continuing Cold War policies. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles

John Foster Dulles

John Foster Dulles served as U.S. Secretary of State under President Dwight D. Eisenhower from 1953 to 1959. He was a significant figure in the early Cold War era, advocating an aggressive stance against communism throughout the world...

was the dominant figure in the nation's foreign policy in the 1950s. Dulles denounced the "containment" of the Truman administration and espoused an active program of "liberation", which would lead to a "rollback

Rollback

In political science, rollback is the strategy of forcing change in the major policies of a state, usually by replacing its ruling regime. It contrasts with containment, which means preventing the expansion of that state; and with détente, which means a working relationship with that state...

" of communism. The most prominent of those doctrines was the policy of "massive retaliation

Massive retaliation

Massive retaliation, also known as a massive response or massive deterrence, is a military doctrine and nuclear strategy in which a state commits itself to retaliate in much greater force in the event of an attack.-Strategy:...

", which Dulles announced early in 1954, eschewing the costly, conventional ground forces characteristic of the Truman administration in favor of wielding the vast superiority of the U.S. nuclear arsenal and covert intelligence

Intelligence (information gathering)

Intelligence assessment is the development of forecasts of behaviour or recommended courses of action to the leadership of an organization, based on a wide range of available information sources both overt and covert. Assessments are developed in response to requirements declared by the leadership...

. Dulles defined this approach as "brinkmanship

Brinkmanship

Brinkmanship is the practice of pushing dangerous events to the verge of disaster in order to achieve the most advantageous outcome...

".

A dramatic and unexpected shock to Americans' self-confidence and its technological superiority came in 1957, when the Soviets beat the United States into outer space by launching Sputnik, the first earth satellite. The space race began, and by the early 1960s the United States had forged ahead, with President Kennedy promising to land a man on the moon by the end of the 1960s—the landing indeed took place on July 20, 1969.

Trouble close to home appeared when the Soviets formed an alliance with Cuba

Cuba

The Republic of Cuba is an island nation in the Caribbean. The nation of Cuba consists of the main island of Cuba, the Isla de la Juventud, and several archipelagos. Havana is the largest city in Cuba and the country's capital. Santiago de Cuba is the second largest city...

after Fidel Castro

Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz is a Cuban revolutionary and politician, having held the position of Prime Minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976, and then President from 1976 to 2008. He also served as the First Secretary of the Communist Party of Cuba from the party's foundation in 1961 until 2011...

's successful revolution in 1959

Cuban Revolution

The Cuban Revolution was an armed revolt by Fidel Castro's 26th of July Movement against the regime of Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista between 1953 and 1959. Batista was finally ousted on 1 January 1959, and was replaced by a revolutionary government led by Castro...

.

East Germany was the weak point in the Soviet empire, with refugees leaving for the West by the thousands every week. The Soviet solution came in 1961, with the Berlin Wall

Berlin Wall

The Berlin Wall was a barrier constructed by the German Democratic Republic starting on 13 August 1961, that completely cut off West Berlin from surrounding East Germany and from East Berlin...

to stop East Germans from fleeing communism. This was a major propaganda setback for the USSR, but it did allow them to keep control of East Berlin.

The Communist world split in half, as China turned against the Soviet Union

Sino-Soviet split

In political science, the term Sino–Soviet split denotes the worsening of political and ideologic relations between the People's Republic of China and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics during the Cold War...

; Mao denounced Khrushchev for going soft on capitalism. However, the US failed to take advantage of this split until President Richard Nixon

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon was the 37th President of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. The only president to resign the office, Nixon had previously served as a US representative and senator from California and as the 36th Vice President of the United States from 1953 to 1961 under...

saw the opportunity in 1969. In 1958, the U.S. sent troops into Lebanon

Lebanon

Lebanon , officially the Republic of LebanonRepublic of Lebanon is the most common term used by Lebanese government agencies. The term Lebanese Republic, a literal translation of the official Arabic and French names that is not used in today's world. Arabic is the most common language spoken among...

for nine months to stabilize a country on the verge of civil war. Between 1954 and 1961, Eisenhower dispatched large sums of economic and military aid and 695 military advisers to South Vietnam

South Vietnam

South Vietnam was a state which governed southern Vietnam until 1975. It received international recognition in 1950 as the "State of Vietnam" and later as the "Republic of Vietnam" . Its capital was Saigon...

to stabilize the pro-western government under attack by insurgents. Eisenhower supported CIA efforts to undermine anti-American governments, which proved most successful in Iran and Guatemala.

The first major strain among the NATO alliance occurred in 1956 when Eisenhower forced Britain and France to retreat from their invasion of Egypt

Suez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, also referred to as the Tripartite Aggression, Suez War was an offensive war fought by France, the United Kingdom, and Israel against Egypt beginning on 29 October 1956. Less than a day after Israel invaded Egypt, Britain and France issued a joint ultimatum to Egypt and Israel,...

(with Israel

Israel

The State of Israel is a parliamentary republic located in the Middle East, along the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea...

) which was intended to get back their ownership of the Suez Canal

Suez Canal

The Suez Canal , also known by the nickname "The Highway to India", is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea. Opened in November 1869 after 10 years of construction work, it allows water transportation between Europe and Asia without navigation...

. Instead of supporting the claims of its NATO partners, the Eisenhower administration stated that it opposed French and British imperial adventurism in the region by sheer prudence, fearing that Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein was the second President of Egypt from 1956 until his death. A colonel in the Egyptian army, Nasser led the Egyptian Revolution of 1952 along with Muhammad Naguib, the first president, which overthrew the monarchy of Egypt and Sudan, and heralded a new period of...

's standoff with the region's old colonial powers would bolster Soviet power in the region.

The Cold War reached its most dangerous point during the Kennedy administration in the Cuban Missile Crisis

Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis was a confrontation among the Soviet Union, Cuba and the United States in October 1962, during the Cold War...

, a tense confrontation between the Soviet Union and the United States over the Soviet deployment of nuclear missiles in Cuba. The crisis began on October 16, 1962, and lasted for thirteen days. It was the moment when the Cold War was closest to exploding into a devastating nuclear exchange between the two superpower nations. Kennedy decided not to invade or bomb Cuba but to institute a naval blockade of the island. The crisis ended in a compromise, with the Soviets removing their missiles publicly, and the United States secretly removing its nuclear missiles in Turkey. In Moscow, Communist leaders removed Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev led the Soviet Union during part of the Cold War. He served as First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964, and as Chairman of the Council of Ministers, or Premier, from 1958 to 1964...

because of his reckless behavior.

The Affluent Society

The immediate years unfolding after World War II were generally ones of stability and prosperity for Americans. The nation reconverted its war machine back into a consumer culture almost overnight and found jobs for 12 million returning veterans. Increasing numbers enjoyed high wages, larger houses, better schools, more cars and home comforts like vacuum cleaners, washing machines—which were all made for labor-saving and to make housework easier. Inventions familiar in the early 21st century made their first appearance during this era. The live-in maid and cook, common features of middle-class homes at the beginning of the century, were virtually unheard of in the 1950s; only the very rich had servants. Householders enjoyed centrally heated homes with running hot water. New style furniture was bright, cheap, and light, and easy to move around.The American economy grew dramatically in the post-war period, expanding at a rate of 3.5% per annum between 1945 and 1970. During this period of prosperity, many incomes doubled in a generation, described by economist Frank Levy

Frank Lévy

-Education:At fifteen he entered the Geneva Conservatory, where he holds bachelor, master, and doctoral degrees studying with Louis Hiltbrand and Maria Tipo. He continued his studies with Leon Fleisher at the Peabody Conservatory, where he received the prestigious Artist Diploma. Levy then went to...

as “upward mobility on a rocket ship.” The substantial increase in average family income within a generation resulted in millions of office and factory workers being lifted into a growing middle class, enabling them to sustain a standard of living once considered to be reserved for the wealthy. As noted by Deone Zell, assembly line work paid well, while unionized factory jobs served as “stepping-stones to the middle class.” By 1960, blue-collar workers had become the biggest buyers of amny luxury goods and services. In addition, by the early Seventies, post-World War II American consumers enjoyed higher levels of disposable income than those in any other country.

The great majority of American workers who had stable jobs were well off financially, while even non-union jobs were associated with rising paychecks, benefits, and obtained many of the advantages that characterized union work. An upscale working class came into being, as American blue-collar workers came to enjoy the benefits of home ownership, while high wages provided blue-collar workers with the ability to pay for new cars, household appliances, and regular vacations. By the 1960s, a blue-collar worker earned more than a manager did in the Forties, despite the fact that his relative position within the income distribution had not changed.

As noted by the historian Nancy Wierek:

"In the postwar period, the majority of Americans were affluent in the sense that they were in a position to spend money on many things they wanted, desired, or chose to have, rather than on necessities alone.”

As argued by the historians Ronald Edsforth

Ronald Edsforth

Ronald Edsforth a Visiting Professor of History, and Chair of Globalization Studies in the MALS Department at Dartmouth College.Edsforth has published several books, most recently The New Deal: America's Response to the Great Depression...

and Larry Bennett:

"By the mid-1960’s, the majority of America’s organized working class who were not victims of the second Red Scare embraced, or at least tolerated, anti-communism because it was an integral part of the New American Dream to which they had committed their lives. Theirs was not an unobtainable dream; nor were their lives empty because of it. Indeed, for at least a quarter of century, the material promises of consumer-oriented Americanism were fulfilled in improvements in everyday life that made them the most affluent working class in American history.”

Between 1946 and 1960, the United States witnessed a significant expansion in the consumption of goods and services. GNP rose by 36% and personal consumption expenditures by 42%, cumulative gains which were reflected in the incomes of families and unrelated individuals. While the number of these units rose sharply from 43.3 million to 56.1 million in 1960, a rise of almost 23%, their average incomes grew even faster, from $3940 in 1946 to $6900 in 1960, an increase of 43%. After taking inflation into account, the real advance was 16%. The dramatic rise in the average American standard of living was such that, according to sociologist George Katona

George Katona

George Katona was a Hungarian-born American psychologist who was one of the first to advocate a rapprochement between economics and psychologists. Originally trained as a Gestalt psychologist working on problems of learning and memory, during the Second World War he became involved in American...

:

- “Today in this country minimum standards of nutrition, housing and clothing are assured, not for all, but for the majority. Beyond these minimum needs, such former luxuries as homeownership, durable goods, travel, recreation, and entertainment are no longer restricted to a few. The broad masses participate in enjoying all these things and generate most of the demand for them.”

More than 21 million housing units were constructed between 1946 and 1960, and in the latter year 52% of consumer units in the metropolitan areas owned their own homes. In 1957, out of all the wired homes throughout the country, 96% had a refrigerator, 87% an electric washer, 81% a television, 67% a vacuum cleaner, 18% a freezer, 12% an electric or gas dryer, and 8% air conditioning. Car ownership also soared, with 72% of consumer units owning an automobile by 1960.

The period from 1946 to 1960 also witnessed a significant increase in the paid leisure time of working people. The forty-hour workweek established by the Fair Labor Standards Act in covered industries became the actual schedule in most workplaces by 1960, while uncovered workers such as farmworkers and the self-employed worked less hours than they had done previously, although they still worked much longer hours than most other workers. Paid vacations also became to be enjoyed by the vast majority of workers, with 91% of blue-collar workers covered by major collective bargaining agreements receiving paid vacations by 1957 (usually to a maximum of three weeks), while by the early Sixties virtually all industries paid for holidays and most did so for seven days a year. Industries catering to leisure activities blossomed as a result of most Americans enjoying significant paid leisure time by 1960, while average blue-collar and white-collar workers had come to expect to hold on to their jobs for life. Educational outlays were also greater than in other countries while a higher proportion of young people were graduating from high schools and universities than elsewhere in the world, as hundreds of new colleges and universities opened every year. Tuition was kept low--it was free at California state universities.At the advanced level American science, engineering and medicine was world famous. By the mid-Sixties, the majority of American workers enjoyed the highest wage levels in the world, and by the late Sixties, the great majority of Americans were richer than people in other countries, except Sweden, Switzerland, and Canada. Educational outlays were also greater than in other countries while a higher proportion of young people was at school and college than elsewhere in the world. As noted by the historian John Vaizey:

“To strike a balance with the Soviet Union, it would be easy to say that all but the very poorest Americans were better off than the Russians, that education was better but the health service worse, but that above all the Americans had freedom of expression and democratic institutions.”

In regards to social welfare, the postwar era saw a considerable improvement in insurance for workers and their dependents against the risks of illness, as private insurance programs like Blue Cross and Blue Shield expanded. With the exception of farm and domestic workers, virtually all members of the labor force were covered by Social Security. In 1959 that about two-thirds of the factory workers and three-fourths of the office workers were provided with supplemental private pension plans. In addition 86% of factory workers and 83% of office had jobs that covered for hospital insurance while 59% and 61% had additional insurance for doctors.

At the center of middle-class culture in the 1950s was a growing demand for consumer goods; a result of the postwar prosperity, the increase in variety and availability of consumer products, and television advertising. America generated a steadily growing demand for better automobiles, clothing, appliances, family vacations and higher education.

Suburbia

With Detroit turning out automobiles as fast as possible, city dwellers gave up cramped apartments for a suburban life style centered around children and housewives, with the male breadwinner commuting to work. Suburbia encompassed a third of the nation's population by 1960. The growth of suburbs was not only a result of postwar prosperity, but innovations of the single-family housing market with low interest rates on 20 and 30 year mortgages, and low down payments, especially for veterans. William LevittWilliam Levitt

William Jaird Levitt was an American real-estate developer widely credited as the father of modern American suburbia. He came to symbolize the new suburban growth with his use of mass-production techniques to construct large developments of houses selling for under $10,000...

began a national trend with his use of mass-production techniques to construct a large "Levittown

Levittown, New York

Levittown is a hamlet in the Town of Hempstead located on Long Island in Nassau County, New York. Levittown is midway between the villages of Hempstead and Farmingdale. As of the 2010 census, the CDP had a total population of 51,881....

" housing development on Long Island

Long Island

Long Island is an island located in the southeast part of the U.S. state of New York, just east of Manhattan. Stretching northeast into the Atlantic Ocean, Long Island contains four counties, two of which are boroughs of New York City , and two of which are mainly suburban...

. Meanwhile, the suburban population swelled because of the baby boom. Suburbs provided larger homes for larger families, security from urban living, privacy, and space for consumer goods.

The new prosperity did not extend to everyone. Many Americans continued to live in poverty throughout the 1950s especially older people and blacks. As Socialist leader Michael Harrington

Michael Harrington

Edward Michael "Mike" Harrington was an American democratic socialist, writer, political activist, professor of political science, radio commentator and founder of the Democratic Socialists of America.-Personal life:...

emphasized, there was still The Other America

The Other America

Michael Harrington’s book The Other America was an influential study of poverty in the United States, published in 1962 by Macmillan. A widely read review, "Our Invisible Poor," in The New Yorker by Dwight Macdonald brought the book to the attention of President John F. Kennedy.The Other America...