History of the British Labour Party

Encyclopedia

This is about the history of the British Labour Party

. For information about the wider history of British socialism see History of socialism in Great Britain

.

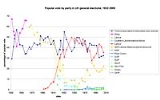

The Labour Party grew out of the trade union

The Labour Party grew out of the trade union

movement and socialist political parties of the 19th century, and surpassed the Liberal Party

as the main opposition to the Conservatives

in the early 1920s. It has had several spells in government, first as minority governments under Ramsay MacDonald

in 1924 and 1929–31, then as a junior partner in the wartime coalition from 1940–1945, and then as a majority government, under Clement Attlee

in 1945–51 and under Harold Wilson

in 1964–70. Labour was in government again in 1974–79, under Wilson and then James Callaghan

, though with a precarious and declining majority.

The previous national Labour government won a landslide 179 seat majority

in the 1997 general election

under the leadership of Tony Blair

, its first general election victory since October 1974

and the first general election since 1970

in which it had exceeded 40% of the popular vote. The party's large majority in the House of Commons was slightly reduced to 167 in the 2001 general election

and more substantially reduced to 66 in 2005

.

The Labour Party's origins lie in the late 19th century numeric increase of the urban proletariat and the extension of the franchise

The Labour Party's origins lie in the late 19th century numeric increase of the urban proletariat and the extension of the franchise

to working-class males, when it became apparent that there was a need for a political party to represent the interests and needs of those groups. Some members of the trade union movement became interested in moving into the political field, and after the extensions of the franchise in 1867 and 1885, the Liberal Party

endorsed some trade-union sponsored candidates. In addition, several small socialist groups had formed around this time with the intention of linking the movement to political policies. Among these were the Independent Labour Party

, the intellectual and largely middle-class Fabian Society

, the Social Democratic Federation

and the Scottish Labour Party.

In the 1895 General Election

the Independent Labour Party put up 28 candidates but won only 44,325 votes. Keir Hardie

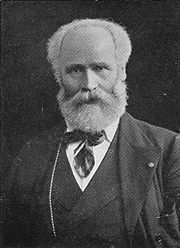

, the leader of the party believed that to obtain success in parliamentary elections, it would be necessary to join with other left-wing groups.

In 1899 a Doncaster

In 1899 a Doncaster

member of the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants

, Thomas R. Steels, proposed in his union branch that the Trade Union Congress call a special conference to bring together all the left-wing organisations and form them into a single body which would sponsor Parliamentary candidates. The motion was passed at all stages by the TUC, and this special conference was held at the Memorial Hall, Farringdon Street, London

on February 26–27, 1900. The meeting was attended by a broad spectrum of working-class and left-wing organisations; trade unions representing about one third of the membership of the TUC delegates.

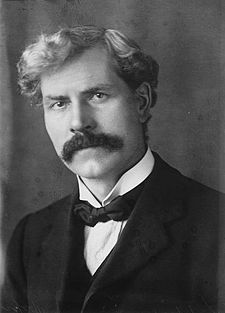

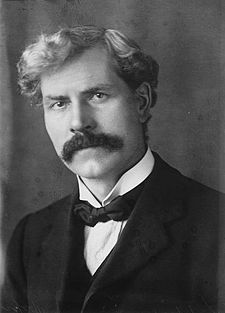

After a debate the 129 delegates passed Hardie's motion to establish "a distinct Labour group in Parliament, who shall have their own whips, and agree upon their policy, which must embrace a readiness to cooperate with any party which for the time being may be engaged in promoting legislation in the direct interests of labour." This created an association called the Labour Representation Committee (LRC), meant to coordinate attempts to support MPs, MPs sponsored by trade unions and representing the working-class population. It had no single leader. In the absence of one, the Independent Labour Party nominee Ramsay MacDonald

was elected as Secretary. He had the difficult task of keeping the various strands of opinions in the LRC united. The October 1900 "Khaki election" came too soon for the new party to effectively campaign. Only 15 candidatures were sponsored, but two were successful: Keir Hardie

in Merthyr Tydfil

and Richard Bell

in Derby

.

Support for the LRC was boosted by the 1901 Taff Vale Case

, a dispute between strikers and a railway company that ended with the union ordered to pay £23,000 damages for a strike

. The judgement effectively made strikes illegal since employers could recoup the cost of lost business from the unions. The apparent acquiescence of the Conservative government of Arthur Balfour

to industrial and business interests (traditionally the allies of the Liberal Party

in opposition to the Conservative's landed interests) intensified support for the LRC against a government that appeared to have little concern for the industrial proletariat and its problems. The LRC won two by-elections in 1902–1903.

In the 1906 election

In the 1906 election

, the LRC won 29 seats — helped by the secret 1903 pact between Ramsay Macdonald

and Liberal

Chief Whip Herbert Gladstone, which aimed at avoiding Labour/Liberal contests in the interest of removing the Conservatives from office.

In their first meeting after the election, the group's Members of Parliament decided to adopt the name "The Labour Party" (February 15, 1906). Keir Hardie, who had taken a leading role in getting the party established, was elected as Chairman of the Parliamentary Labour Party (in effect, the Leader), although only by one vote over David Shackleton

after several ballots. In the party's early years, the Independent Labour Party

(ILP) provided much of its activist base as the party did not have an individual membership until 1918 and operated as a conglomerate of affiliated bodies until that date. The Fabian Society

provided much of the intellectual stimulus for the party. One of the first acts of the new Liberal government was to reverse the Taff Vale judgement.

the Labour Party split between supporters and opponents of the conflict and opposition within the party to the war grew as time went on. Ramsay MacDonald

, a notable anti-war campaigner, resigned as leader of the Parliamentary Labour Party and Arthur Henderson

became the main figure of authority within the Party and was soon accepted into H. H. Asquith

's War Cabinet.

Despite mainstream Labour Party's support for the Coalition, the Independent Labour Party

was instrumental in opposing mobilisation through organisations such as the Non-Conscription Fellowship and a Labour Party affiliate, the British Socialist Party

organised a number of unofficial strikes

.

Arthur Henderson

resigned from the Cabinet in 1917 amidst calls for Party unity, being replaced by George Barnes

. The growth in Labour's local activist base and organisation was reflected in the elections following the War, with the co-operative movement now providing its own resources to the Co-operative Party

after the armistice. The Co-operative Party later reached an electoral agreement with the Labour Party.

The Liberal Party splitting between supporters of leader David Lloyd George and former leader H. H. Asquith

allowed the Labour Party to co-opt some of the Liberals' support, and by the 1922 general election

Labour had supplanted the Liberal Party

as the second party in the United Kingdom and as the official opposition to the Conservatives

. After the election, the now rehabilitated Ramsay MacDonald was voted the first official leader of the Labour Party.

Labour's electoral base resided in the industrial areas of Northern England

, the Midlands

, central Scotland

and Wales

. In these areas Labour Clubs were founded to provide recreation for working men, with many of these clubs becoming affiliated to The Working Men's Club and Institute Union. Because of the concentrated geographical nature of Labour's support, industrial downturns tended to hit Labour voters directly. Anecdotal evidence suggests that party membership was often working-class but also included many middle-class radicals, former liberals and socialists. Accordingly, the more middle-class branches in London and the South of England tended to be more left-wing and radical than those in the primary industrial areas.

was fought on the Conservatives' protectionist proposals; although they got the most votes and remained the largest party, they lost their majority in parliament, requiring a government supporting free trade

to be formed. So with the acquiescence of Asquith's Liberals, Ramsay MacDonald

became Prime Minister in January 1924 and formed the first ever Labour government, despite Labour only having 191 MPs (less than a third of the House of Commons).

Because the government had to rely on the support of the Liberals, it was unable to get any socialist legislation passed by the House of Commons. The only significant measure was the Wheatley Housing Act which began a building programme of 500,000 homes for rent to working-class families.

The government collapsed after only nine months when the Liberals voted for a Select Committee inquiry into the Campbell Case, a vote which MacDonald had declared to be a vote of confidence. The ensuing general election

saw the publication, four days before polling day, of the notorious Zinoviev letter

, which implicated Labour in a plot for a Communist revolution in Britain, and the Conservatives were returned to power, although Labour increased its vote from 30.7% of the popular vote to a third of the popular vote - most of the Conservative gains were at the expense of the Liberals. The Zinoviev letter is now generally believed to have been a forgery.

faced a number of labour problems most notably the General Strike of 1926

. Ramsay MacDonald continued with his policy of opposing strike action

, including the General Strike

, arguing that the best way to achieve social reforms was through the ballot box, although Labour claimed that the BBC was biased in its reporting against the party over the issue.

left the Labour Party for the first time as the largest grouping in the House of Commons with 287 seats, and 37.1% of the popular vote (actually slightly less than the Conservatives). However, MacDonald was still reliant on Liberal support to form a minority government. MacDonald's government included the first ever woman cabinet minister Margaret Bondfield

who was appointed Minister of Labour

.

MacDonald's second government was in a stronger parliamentary position than his first, and in 1930 he was able to pass a revised Old Age Pensions Act, a more generous Unemployment Insurance Act, and an act to improve wages and conditions in the coal industry (i.e. the issues behind the General Strike).

and eventual Great Depression

occurred soon after the government came to power, and the crisis hit Britain hard. By the end of 1930 the unemployment rate had doubled to over two and a half million.

The Labour government struggled to cope with the crisis and found itself attempting to reconcile two contradictory aims; achieving a balanced budget in order to maintain the pound

on the Gold Standard

, whilst also trying to maintain assistance to the poor and unemployed. All of this whilst tax revenues were falling. The Chancellor of the Exchequer

, Philip Snowden refused to permit deficit spending

.

One junior minister, Oswald Mosley

, put forward a memorandum in January 1930, calling for the public control of imports and banking as well as an increase in pensions to boost spending power. When this was repeatedly turned down, Mosley resigned from the government in February 1931 and went on to form the New Party, and later the British Union of Fascists

after he converted to Fascism

.

By 1931 the situation had deteriorated further. Under pressure from its Liberal allies as well as the Conservative opposition who feared that the budget was unbalanced, the Labour government appointed a committee headed by Sir George May

to review the state of public finances. The May Report

of July 1931 urged public-sector wage cuts and large cuts in public spending (notably in payments to the unemployed) in order to avoid a budget deficit.

This proposal proved deeply unpopular within the Labour Party grass roots and the trade union

s, which along with several government ministers, refused to support any such measures. Several senior ministers such as Arthur Henderson

and J. R. Clynes threatened to resign rather than agree to the cuts. MacDonald, and Philip Snowden however, insisted that the Report's recommendations must be adopted to avoid incurring a budget deficit.

The dispute over spending and wage cuts split the Labour government; as it turned out, fatally. The cabinet repeatedly failed to agree to make cuts to spending or introduce tariffs. The resulting political deadlock caused investors to take fright, and a flight of capital and gold further de-stabilised the economy. In response, MacDonald, on the urging of King George V

, agreed to form a National Government, with the Conservatives

and the Liberals.

On August 24, 1931 MacDonald submitted the resignation of his ministers and led a small number of his senior colleagues, most notably Snowden and Dominions Secretary J. H. Thomas

, in forming the National Government with the other parties. MacDonald and his supporters were then expelled from the Labour Party and formed National Labour. The remaining Labour Party, now led by Arthur Henderson

, and a few Liberals went into opposition.

Soon after this, a General Election

was called. The 1931 election

resulted in a landslide victory for the National Government, and was a disaster for the Labour Party which won only 52 seats, 225 fewer than in 1929.

MacDonald continued as Prime Minister of the Conservative dominated National Government until 1935. MacDonald's actions in ditching the Labour government to form a coalition with the Conservatives, led to him being denounced by the Labour Party as a "traitor" and a "rat" for what they saw as his betrayal.

, who had been elected in 1931 as Labour leader to succeed MacDonald, lost his seat in the 1931 General Election. The only former Labour cabinet member who survived the landslide was the pacifist George Lansbury

, who accordingly became party leader.

The party experienced a further split in 1932 when the Independent Labour Party

, which for some years had been increasingly at odds with the Labour leadership, opted to disaffiliate from the Labour Party. The ILP embarked on a long drawn out decline. The role of the ILP within the Labour Party was taken up for a time by the Socialist League

led by Stafford Cripps

, until it was wound up in 1937.

The Labour Party moved to the left

during the early 1930s. The party's programme "For Socialism and Peace" adopted in 1934, committed the party to nationalisation of land, banking, coal, iron and steel, transport, power and water supply, as well as the setting up of a National Investment Board to plan industrial development.

Public disagreements between Lansbury and many Labour Party members over foreign policy, notably in relation to Lansbury's opposition to applying sanctions against Italy

for its aggression against Abyssinia

, caused Lansbury to resign during the 1935 Labour Party Conference. He was succeeded by his deputy Clement Attlee

, who achieved a revival in Labour's fortunes in the 1935 General Election

, winning a similar number of votes to those attained in 1929 and actually, at 38% of the popular vote, the highest percentage that Labour had ever achieved, securing 154 seats. Attlee was initially regarded as a caretaker leader, however he turned out to be the longest serving party leader to date, and one of its most successful.

With the rising threat from Nazi Germany

in the 1930s, the Labour Party gradually abandoned its earlier pacifist

stance, and came out in favour of rearmament. This shift largely came about due to the efforts of Ernest Bevin

and Hugh Dalton

who by 1937 also persuaded the party to oppose Neville Chamberlain

's policy of appeasement

.

Labour achieved a number of by-election upsets in the later part of the 1930s despite the world depression having come to an end and unemployment falling.

resigned as Prime Minister after the defeat in Norway in spring 1940, incoming Prime Minister Winston Churchill

decided that it was important to bring the other main parties into the government and have a Wartime Coalition similar to that in the First World War. Labour took two of the five seats in the War Cabinet. Clement Attlee became Lord Privy Seal

and was effectively (and eventually formally) Deputy Prime Minister

for the remainder of the duration of the War in Europe. Labour deputy leader Arthur Greenwood

took the other War Cabinet seat as Minister without Portfolio, given special responsibility for planning post-war reconstruction.

A number of other senior Labour figure took up senior positions: the trade union leader Ernest Bevin

as Minister of Labour

directed Britain's wartime economy and allocation of manpower; the veteran Labour statesman Herbert Morrison

became Home Secretary

; Hugh Dalton

was Minister of Economic Warfare

and later President of the Board of Trade; and A. V. Alexander

resumed the role of First Lord of the Admiralty he had held in the previous Labour government. The party generally performed well in government, and its experience there may have been partly responsible for its post-war success.

(July 5) in opposition to Churchill's Conservatives. Surprising many observers, Labour won a landslide victory, winning just under 50% of the vote with a majority of 145 seats.

Although the exact reasons for the victory are still debated. During the war, public opinion surveys showed public opinion moving to the left and in favour of radical social reform. There was little public appetite for a return to the poverty and mass unemployment of the interwar years which had become associated with the Conservatives.

Clement Attlee's government proved to be one of the most radical British governments of the 20th century. It presided over a policy of selective nationalisation of major industries and utilities, including the Bank of England

Clement Attlee's government proved to be one of the most radical British governments of the 20th century. It presided over a policy of selective nationalisation of major industries and utilities, including the Bank of England

, coal mining

, the steel industry

, electricity, gas, telephones, and inland transport (including the railways, road haulage and canals). It developed the "cradle to grave" welfare state

conceived by the Liberal economist William Beveridge

. To this day, the party still considers the creation in 1948 of Britain's publicly funded

National Health Service

under health minister Aneurin Bevan

its proudest achievement.

Attlee's government also began the process of dismantling the British Empire

when it granted independence to India

in 1947. This was followed by Burma (Myanmar

) and Ceylon (Sri Lanka

) the following year.

With the onset of the Cold War

, at a secret meeting in January 1947, Attlee, and six cabinet ministers including foreign minister Ernest Bevin

, secretly decided to proceed with the development of Britain's nuclear deterrent, in opposition to the pacifist and anti-nuclear stances of a large element inside the Labour Party.

Labour won the 1950 general election

but with a much reduced majority of five seats. Soon after the 1950 election, things started to go badly wrong for the Labour government. Defence became one of the divisive issues for Labour itself, especially defence spending (which reached 14% of GDP in 1951 during the Korean War

). These costs put enormous strain on public finances, forcing savings to be found elsewhere. The Chancellor of the Exchequer

, Hugh Gaitskell

introduced prescription charges for NHS prescriptions

, causing Bevan, along with Harold Wilson

(President of the Board of Trade) to resign over the dilution of the principle of free treatment.

Soon after this, another election was called. Labour narrowly lost the October 1951 election

to the Conservatives, despite their receiving a larger share of the popular vote and, in fact, their highest vote ever numerically.

Most of the changes introduced by the 1945-51 Labour government however were accepted by the Conservatives and became part of the "post war consensus", which lasted until the 1970s.

" right of the party led by Hugh Gaitskell

and associated with thinkers such as Anthony Crosland

wanted the party to adopt a moderate social democratic

position. Whereas the "Bevanite

" left, led by Aneurin Bevan

wanted the party to adopt a more radical socialist position. This split, and the fact that the 1950s saw economic recovery and general public contentment with the Conservative governments of the time, helped keep the party out of power for thirteen years

After being defeated at the 1955 general election, Attlee resigned as leader and was replaced by Gaitskell. The trade union block vote, which generally voted with the leadership, ensured that the bevanites were eventually defeated.

The three key divisive issues that were to split the Labour party in successive decades emerged first during this period; nuclear disarmament

, the famous Clause IV

of the party's constitution, which called for the ultimate nationalisation of all means of production in the British economy, and Britain's entry into the European Economic Community

(EEC). Tensions between the two opposing sides were exacerbated after Attlee resigned as leader in 1955 and Gaitskell defeated Bevan in the leadership election that followed. The party was briefly revived and unified during the Suez Crisis

of 1956. The Conservative party was badly damaged by the incident while Labour was rejuvenated by its opposition to the policy of prime minister Anthony Eden

. But Eden was replaced by Harold Macmillan

, while the economy continued to improve.

In the 1959 election the Conservatives fought under the slogan "Life is better with the Conservatives, don't let Labour ruin it" and the result saw the government majority increase. Following the election bitter internecine disputes resumed. Gaitskell blamed the Left for the defeat and attempted unsuccessfully to amend Clause IV. At a hostile party conference in 1960 he failed to prevent a vote adopting unilateral nuclear disarmament as a party policy, declaring in response that he would "fight, fight and fight again to save the party I love". The decision was reversed the following year, but it remained a divisive issue, and many in the left continued to call for a change of leadership.

When the Conservative government attempted to take Britain into the EEC in 1962, Gaitskell alienated some of his supporters by his opposition to British membership. In a speech to the party conference in October 1962 Gaitskell claimed that EEC membership would mean "the end of Britain as an independent European state. I make no apology for repeating it. It means the end of a thousand years of history".

Gaitskell died suddenly in January 1963 from a rare disease. His death made way for Harold Wilson

to lead the party. The term "thirteen wasted years" was coined by Wilson as a slogan for the 1964 general election, in reference to what he claimed were thirteen wasted years of Conservative government.

A downturn in the economy, along with a series of scandals in the early 1960s (the most notorious being the Profumo affair

A downturn in the economy, along with a series of scandals in the early 1960s (the most notorious being the Profumo affair

), engulfed the Conservative government by 1963. The Labour party returned to government with a wafer-thin 4 seat majority under Wilson in the 1964 election

, and increased their majority to 96 in 1966 election

remaining in power until the 1970 election

which, contrary to expectations during the campaign, they lost.

put faith in economic planning

as a way to solve Britain's economic problems. Wilson famously referred to the "white heat of technology", referring to the modernisation of British industry. This was to be achieved through the swift adoption of new technology, aided by government-funded infrastructure improvements and the creation of large high-tech public sector corporations guided by a Ministry of Technology. Economic planning through the new Department of Economic Affairs

was to improve the trade balance, whilst Labour carefully targeted taxation aimed at "luxury" goods and services.

In practice however, Labour had difficulty managing the economy under the "Keynesian consensus" and the international markets instinctively mistrusted the party. Events derailed much of the initial optimism. Upon coming to power, the government was informed that the trade deficit was far worse than expected. This soon led to a currency crisis

; despite enormous efforts to shore up the value of sterling, in November 1967 the government was forced into devaluation

of the pound from $2.80 to $2.40, which damaged the government's credibility.

For much of the remaining Parliament the government followed stricter controls in public spending and the necessary austerity measures caused consternation amongst the Party membership and the trade unions, unions which by this time were gaining ever greater political power.

In the event, the devaluation, and austerity measures successfully restored the balance of payments into a surplus by 1969. However, they unexpectedly turned into a small deficit again in 1970. The bad figures were announced just before polling in the 1970 general election, and are often cited as one of the reasons for Labour's defeat.

As a gesture towards Labour's left wing supporters. Wilson's government renationalised the steel industry in 1967 (which had been denationalised by the Conservatives in the 1950s) creating British Steel

.

social reforms introduced or supported by Home Secretary

Roy Jenkins

. Notable amongst these was the legalisation of male homosexuality

and abortion

, reform of divorce

laws, the abolition of theatre censorship

and capital punishment

(except for a small number of offences - notably high treason

) and various legislation addressing race relations and racial discrimination.

In Wilson's defence, his supporters also emphasise the easing of means testing for non-contributory welfare benefits, the linking of pensions to earnings, and the provision of industrial-injury benefits. Wilson's government also made significant reforms to education

, most notably the expansion of comprehensive education and the creation of the Open University

.

In spite of the economic difficulties faced by Wilson's government, it was thereforeable to achieve important advances in a number of domestic policy areas. As reflected by Harold Wilson in 1971,

"It was a government which faced disappointment after disappointment and none greater than the economic restraints in our ability to carry through the social revolution to which we were committed at the speed we would have wished. Yet, despite those restraints and the need to transfer resources from domestic expenditure, private and public, to the needs of our export markets, we carried through an expansion in the social services, health, welfare and housing, unparallelled in our history".

entitled "In Place of Strife

", which proposed to give trade unions statutory rights, but also to limit their power. The White Paper was championed by Wilson and Barbara Castle

. The proposals however faced stiff opposition from the Trades Union Congress

, and some key cabinet ministers such as James Callaghan

.

The opponents won the day and the proposals were shelved. This episode proved politically damaging for Wilson, whose approval ratings fell to 26%; the lowest for any Prime Minister since polling began.

In hindsight, many have argued that the failure of the unions to adopt the proposals of In Place of Strife, led to the far more drastic curbs on trade union power under Margaret Thatcher

in the 1980s.

, Edward Heath

's Conservatives narrowly defeated Harold Wilson's government reflecting some disillusionment amongst many who had voted Labour in 1966. The Conservatives quickly ran into difficulties, alienating Ulster Unionists

and many Unionists in their own party after signing the Sunningdale Agreement

in Ulster. Heath's government also faced the 1973 miners strike which forced the government to adopt a "Three-Day Week

". The 1970s proved to be a very difficult time for the Heath, Wilson and Callaghan administrations. Faced with a mishandled oil crisis, a consequent worldwide economic downturn, and a badly suffering British economy.

The 1970s saw tensions re-emerge between Labour's left and right wings, which eventually caused a catastrophic split in the party in the 1980s and the formation of the Social Democratic Party

. Following the perceived disappointments of the 1960s Labour government and the failiures of the 'revisionist' right. The left of the party under Tony Benn

and Michael Foot

became increasingly influential during the early 1970s

The left drew up a radical programme; Labour's Programme 1973, which pledged to bring about a "fundamental and irreversible shift in the balance of power and wealth in favour of working people and their families". This programme referred to a "far reaching Social Contract

between workers and the Government" and called for a major extension of public ownership and state planning. The programme was accepted by that year's party conference. Wilson publicly accepted many of the policies of the Programme with some reservations, but the condition of the economy allowed little room for manoeuvre. In practice many of the proposals of the programme were heavily watered down when Labour returned to government.

, forming a minority government with Ulster Unionist support. The Conservatives were unable to form a government as they had fewer seats, even though they had received more votes. It was the first General Election since 1924 in which both main parties received less than 40% of the popular vote, and was the first of six successive General Elections in which Labour failed to reach 40% of the popular vote. In a bid for Labour to gain a majority, a second election was soon called for October 1974

in which Labour, still with Harold Wilson as leader, scraped a majority of three, gaining just 18 seats and taking their total to 319.

(EEC) in 1973 while Edward Heath

was Prime Minister. Although Harold Wilson and the Labour party had opposed this, in government Wilson switched to backing membership, but was defeated in a special one day Labour conference on the issue leading to a national referendum on which the yes and no campaigns were both cross-party - the referendum voted in 1975 to continue Britain's membership by two thirds to one third. This issue later caused catastrophic splits in the Labour Party in the 1980s, leading to the formation of the Social Democratic Party

.

In the initial legislation during the Heath Government, the Bill affirming Britain's entry was only passed because of a rebellion of 72 Labour MPs led by Roy Jenkins

and including future leader John Smith

, who voted against the Labour whip and along with Liberal MPs more than countered the effects of Conservative rebels who had voted against the Conservative Whip.

. He feared following his mother's path: she had been a towering, impressive personality but did not accept her failing abilities and carried on for too long spoiling her reputation. He was replaced by James Callaghan

who immediately removed a number of left-wingers (such as Barbara Castle

) from the cabinet.

In the same year as Callaghan became leader, the party in Scotland

suffered the breakaway of two MPs into the Scottish Labour Party (SLP). Whilst ultimately the SLP proved no real threat to the Labour Party's strong Scottish electoral base it did show that the issue of Scottish devolution

was becoming increasingly contentious, especially after the discovery of North Sea Oil

.

. Many of Britain's traditional manufacturing industries were collapsing in the face of foreign competition. Unemployment, and industrial unrest were rising.

In the autumn of 1976 the Labour Government under Chancellor Denis Healey

was forced to ask the International Monetary Fund

(IMF) for a loan to ease the economy through its financial troubles. The conditions attached to the loan included harsh austerity

measures such as sharp cuts in public spending, which were highly unpopular with party supporters. This forced the government to abandon much of the radical program which it had adopted in the early 1970s, much to the anger of left wingers such as Tony Benn

. It later turned out however that the loan had not been necessary. The error had been caused by incorrect financial estimates by the Treasury

which overestimated public borrowing requirements. The government only drew on half of the loan and was able to pay it back in full by 1979.

The 1970s Labour government adopted an interventionist

approach to the economy, setting up the National Enterprise Board

to channel public investment into industry, and giving state support to ailing industries. Several large nationalisations were carried out during this era: The struggling motor manufacturer British Leyland was partly nationalised in 1975. In 1977 British Aerospace

as well as what remained of the shipbuilding industry

were nationalised, as well as the British National Oil Corporation. The Government also succeeded in replacing the Family Allowance with the more generous child benefit

.

The Wilson and Callaghan governments were hampered by their lack of a workable majority in the commons. At the October 1974 election, Labour won a majority of only three seats. Several by-election losses meant that by 1977, Callaghan was heading a minority government, and was forced to do deals with other parties to survive. An arrangement was negotiated in 1977 with the Liberals known as the Lib-Lab pact

, but this ended after one year. After this, deals were made with the Scottish National Party

and the Welsh

nationalist Plaid Cymru

, which prolonged the life of the government slightly longer.

The nationalist parties demanded devolution

to their respective countries in return for their support for the government. When referendum

s for Scottish and Welsh devolution were held in March 1979, the Welsh referendum was rejected outright, and the Scottish referendum had a narrow majority in favour but did not reach the threshold of 40% support, invalidating the result. This led to the SNP withdrawing support for the government, which finally brought it down.

had caused a legacy of high inflation

in the British economy which peaked at 26.9% in 1975. The Wilson and Callaghan governments attempted to combat this by entering into a social contract

with the trade unions, which introduced wage restraint and limited pay rises to limits set by the government. This policy was initially fairly successful at controlling inflation, which had been reduced to 7.4% by 1978.

Callaghan had been widely expected to call a general election in the autumn of 1978, when most opinion polls showed Labour to have a narrow lead. However instead, he decided to extend the wage restraint policy for another year in the hope that the economy would be in a better shape in time for a 1979 election. This proved to be a big mistake. The extension of wage restraint was unpopular with the trade unions, and the government's attempt to impose a "5% limit" on pay rises caused resentment amongst workers and trade unions, with whom relations broke down.

During the winter of 1978-79 there were widespread strikes

in favour of higher pay rises which caused significant disruption to everyday life. The strikes affected lorry drivers, railway workers, car workers and local government and hospital workers. These came to be dubbed as the "Winter of Discontent

".

The perceived relaxed attitude of Callaghan to the crisis reflected badly upon public opinion of the government's ability to run the country. After the withdrawal of SNP support for the government, the Conservatives put down a vote of no confidence, which was held and passed by one vote on 28 March 1979, forcing a general election.

In the 1979 general election

, Labour suffered electoral defeat to the Conservatives

led by Margaret Thatcher

. The numbers voting Labour hardly changed between February 1974 and 1979, but in 1979 the Conservative Party achieved big increases in support in the Midlands and South of England, mainly from the ailing Liberals, and benefited from a surge in turnout.

The actions of the trade unions during the Winter of Discontent were used by Margaret Thatcher's government to justify anti-trade union legislation during the 1980s.

and Tony Benn

(whose supporters dominated the party organisation at the grassroots level), and the right under Denis Healey

. It was widely considered that Healey would win the 1980 leadership election

, but he was narrowly defeated by Foot.

The Thatcher government was determined not to be deflected from its agenda as the Heath government had been. A deflationary budget in 1980 led to substantial cuts in welfare spending and an initial short-term sharp rise in unemployment. The Conservatives reduced or eliminated state assistance for struggling private industries, leading to large redundancies in many regions of the country, notably in Labour's heartlands. However, Conservative legislation extending the right for residents to buy council houses from the state proved very attractive to many Labour voters. (Labour had previously suggested this idea in their 1970 election manifesto, but had never acted on it.)

The election of Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament

(CND) veteran Michael Foot to the leadership disturbed many Atlanticists in the Party. Other changes increased their concern; the constituencies were given the ability to easily deselect sitting MPs, and a new voting system in leadership elections was introduced that gave party activists and affiliated trade unions a vote in different parts of an electoral college.

The party's move to the left in the early 80s led to the decision by a number of centrist party members led by the Gang of Four

of former cabinet ministers (Shirley Williams, William Rodgers, Roy Jenkins

, and David Owen

. ) to issue the "Limehouse Declaration

" on January 26, 1981, and to form the breakaway Social Democratic Party

. The departure of even more members from the centre and right further swung the party to the left, but not quite enough to allow Tony Benn to be elected as Deputy Leader when he challenged for the job at the September 1981 party conference.

Under Foot's leadership, the party's agenda became increasingly dominated by the politics of the hard left

. Accordingly, the party went into the 1983 general election

with the most left wing manifesto that Labour ever stood upon. The manifesto contained pledges for abolition of the House of Lords

, unilateral nuclear disarmament, withdrawal from the European Community, withdrawal from NATO and a radical and extensive extension of state control over the economy.

This alienated many of the party's more right-wing supporters. The Bennites were in the ascendency and there was very little that the right could do to resist or water down the manifesto, many also hoped that a landslide defeat would discredit Michael Foot and the hard left of the party moving Labour away from explicit Socialism and towards weaker social-democracy. Labour MP and former minister Gerald Kaufman

famously described the 1983 election manifesto as "the longest suicide note in history". Michael Foot has countered, with typical wit, that it is telling about Gerald Kaufman that it is likely that his one oft quoted remark will be all that he is remembered for.

Much of the press attacked both the Labour party's manifesto and its style of campaigning, which tended to rely upon public meetings and canvassing rather than media. By contrast, the Conservatives ran a professional campaign which played on the voters' fears of a repeat of the Winter of Discontent. To add to this, the Thatcher government's popularity rose sharply on a wave of patriotic feeling following victory in the Falklands War

Much of the press attacked both the Labour party's manifesto and its style of campaigning, which tended to rely upon public meetings and canvassing rather than media. By contrast, the Conservatives ran a professional campaign which played on the voters' fears of a repeat of the Winter of Discontent. To add to this, the Thatcher government's popularity rose sharply on a wave of patriotic feeling following victory in the Falklands War

, allowing it to recover from it initial unpopularity over unemployment and economic difficulty.

At the 1983 election, Labour suffered a landslide defeat, winning only 27.6% of the vote, their lowest share since 1918

. Labour won only half a million votes more than the SDP-Liberal Alliance

which had attracted the votes of many moderate Labour supporters.

, initially considered a firebrand left-winger, he proved to be more pragmatic than Foot and progressively moved the party towards the centre; banning left-wing groups such as the Militant tendency

and reversing party policy on EEC membership and withdrawal from NATO, bringing in Peter Mandelson

as Director of Communications to modernise the party's image, and embarking on a policy review which reported back in 1985.

At the 1987 general election

, the party was again defeated in a landslide, but had at least re-established itself as the clear challengers to the Conservatives and gained 20 seats reducing the Conservative majority to 102 from 143 in 1983, despite a sharp rise in turnout. Challenged for the leadership by Tony Benn

in 1988, Neil Kinnock easily retained the leadership claiming a mandate for his reforms of the party. Re-organisation resulted in the dissolution of the Labour Party Young Socialists

, which was thought to be harbouring entryist Militant

groups. It also resulted in a more centralised communication structure, enabling a greater degree of flexibility for the leadership to determine policy, react to events, and direct resources.

During this time the Labour Party emphasised the abandonment of its links to high taxation and old-style nationalisation, which aimed to show that the party was moving away from the left of the political spectrum and towards the centre. It also became actively pro-European, supporting further moves to European integration

.

from Conservative MP and former cabinet minister Michael Heseltine

, eventually leaving Labour facing a new Conservative Prime Minister in John Major

.

By the time of the 1992 general election campaign

, the party had reformed to such an extent that it was perceived as a credible government-in-waiting. Most opinion polls showed the party to have a slight lead over the Conservatives, although rarely sufficient for a majority. However, the party ended up 8% behind the Conservatives in the popular vote in one of the biggest surprises in British electoral history. Although Labour's support was comparable to the February and October 1974 and May 1979 General Elections, the overall turnout was much larger.

In the party's post mortem on why it had lost, it was considered that the "Shadow Budget" announced by John Smith

had opened the way for Conservatives to attack the party for wanting to raise taxes. In addition, a triumphalist party rally held in Sheffield

eight days before the election, was generally considered to have backfired. The party had also suffered from a powerfully co-ordinated campaign from the right-wing press, particularly Rupert Murdoch

's The Sun

. Kinnock resigned after the defeat, blaming the Conservative-supporting newspapers for Labour's failure and John Smith

, despite his involvement with the Shadow Budget, was elected to succeed him.

system called OMOV — but only barely, after a barnstorming speech by John Prescott

which required Smith to compromise on other individual negotiations.

However, they benefitted from an increasingly unpopular and divided Conservative government which ran into trouble, when on 'Black Wednesday

' it was forced to leave the European Exchange Rate Mechanism

. After this, Labour moved ahead in the opinion polls as the Conservatives became increasingly unpopular.

John Smith died suddenly in May 1994 from a heart attack, prompting a leadership election for his successor, likely to be the next Prime Minister. With 57% of the vote, Tony Blair

won a resounding victory in a three-way contest with John Prescott and Margaret Beckett

. Prescott became deputy leader, coming second in the poll whose results were announced on 21 July 1994.

published by the party in 1996, called New Labour, New Life For Britain

and presented by Labour as being the brand of the new reformed party that had in 1995 altered Clause IV

and reduced the Trade Union vote in the electoral college used to elect the leader and deputy leader to have equal weighting with individual other parts of the electoral college.

Peter Mandelson

was a senior figure in this process, and exercised a great deal of authority in the party following the death of John Smith

and the subsequent election of Tony Blair

as party leader.

The name is primarily used by the party itself in its literature but is also sometimes used by political commentators and the wider media

; it was also the basis of a Conservative Party

poster campaign of 1997, headlined "New Labour, New Danger". The rise of the name coincided with a rightwards shift of the British political spectrum; for Labour, this was a continuation of the trend that had begun under the leadership of Neil Kinnock

. "Old Labour" is sometimes used by commentators to describe the older, more left-wing members of the party, or those with strong Trade Union connections.

Tony Blair

, Gordon Brown

, Peter Mandelson

, Anthony Giddens

and Alastair Campbell

are most commonly cited as the creators and architects of "New Labour". They were among the most prominent advocates of the shift in European social democracy

during the 1990s, known as the "Third Way

". Although this policy was advantageous to the Labour Party in the eyes of the British electorate, it alienated many grass roots members by distancing itself from the ideals of socialism in favour of free market policy decisions.

The "modernisation" of Labour party policy and the unpopularity of John Major

's Conservative government, along with a well co-ordinated use of PR, greatly increased Labour's appeal to "middle England

". The party was concerned not to put off potential voters who had previously supported the Conservatives, and pledged to keep to the spending plans of the previous government, and not to increase the basic rate of income tax. The party won the 1997 election

with a landslide majority of 179. Following a second and third election victory in the 2001 election

and the 2005 election

, the name has diminished in significance. "New Labour" as a name has no official status but remains in common use to distinguish modernisers from those holding to more traditional positions who normally are referred to as "Old Labour".

Many of the traditional grassroots working-class members of the Labour Party who have become upset and disillusioned with "New" Labour, have left the Party and gone on to join political parties such as the Socialist Party (England and Wales)

, the Socialist Labour Party

and even the Communist Party of Great Britain

- all parties claiming to never neglect the "ordinary British people". David Osler, the journalist and author of "Labour Party plc" seems to hint in his book that Labour's supposed steady shift from Socialism and its neglect of support for the working-class people of Britain began to show during the Party's years under Harold Wilson. In the book, Osler claims that the Party is now only a socialist party and indeed a "Labour" party in name only and is a full-capitalist embracing Party which differs little from the Tory Party. Other historians have also argued that Old Labour’s record in putting its social democratic ideals into practice was less successful than comparable northern European sister parties.

With the unpopularity of John Major's government. Labour party won the 1997 election

With the unpopularity of John Major's government. Labour party won the 1997 election

with a landslide majority of 179.

Among the early acts of Tony Blair's government were the establishment of the National minimum wage. And devolution of power to Scotland

, Wales

and Northern Ireland

and re-created a city wide government body for London

; the Greater London Authority

.

Labour went on to win the 2001 election

with a similar majority to 1997. Tony Blair controversially allied himself with President George W Bush in supporting the Iraq War, which lost his government much support. At the 2005 election

, Labour was returned to power with a much reduced majority.

In 2007 Tony Blair stood down as prime minister and was replaced by Gordon Brown

.

Labour Party (UK)

The Labour Party is a centre-left democratic socialist party in the United Kingdom. It surpassed the Liberal Party in general elections during the early 1920s, forming minority governments under Ramsay MacDonald in 1924 and 1929-1931. The party was in a wartime coalition from 1940 to 1945, after...

. For information about the wider history of British socialism see History of socialism in Great Britain

History of socialism in Great Britain

The History of socialism in the United Kingdom is generally thought to stretch back to the 19th century. Starting to arise in the aftermath of the English Civil War notions of socialism in Great Britain and Northern Ireland have taken many different forms from the utopian philanthropism of Robert...

.

Trade union

A trade union, trades union or labor union is an organization of workers that have banded together to achieve common goals such as better working conditions. The trade union, through its leadership, bargains with the employer on behalf of union members and negotiates labour contracts with...

movement and socialist political parties of the 19th century, and surpassed the Liberal Party

Liberal Party (UK)

The Liberal Party was one of the two major political parties of the United Kingdom during the 19th and early 20th centuries. It was a third party of negligible importance throughout the latter half of the 20th Century, before merging with the Social Democratic Party in 1988 to form the present day...

as the main opposition to the Conservatives

Conservative Party (UK)

The Conservative Party, formally the Conservative and Unionist Party, is a centre-right political party in the United Kingdom that adheres to the philosophies of conservatism and British unionism. It is the largest political party in the UK, and is currently the largest single party in the House...

in the early 1920s. It has had several spells in government, first as minority governments under Ramsay MacDonald

Ramsay MacDonald

James Ramsay MacDonald, PC, FRS was a British politician who was the first ever Labour Prime Minister, leading a minority government for two terms....

in 1924 and 1929–31, then as a junior partner in the wartime coalition from 1940–1945, and then as a majority government, under Clement Attlee

Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee, KG, OM, CH, PC, FRS was a British Labour politician who served as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951, and as the Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955...

in 1945–51 and under Harold Wilson

Harold Wilson

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx, KG, OBE, FRS, FSS, PC was a British Labour Member of Parliament, Leader of the Labour Party. He was twice Prime Minister of the United Kingdom during the 1960s and 1970s, winning four general elections, including a minority government after the...

in 1964–70. Labour was in government again in 1974–79, under Wilson and then James Callaghan

James Callaghan

Leonard James Callaghan, Baron Callaghan of Cardiff, KG, PC , was a British Labour politician, who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1976 to 1979 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1976 to 1980...

, though with a precarious and declining majority.

The previous national Labour government won a landslide 179 seat majority

Landslide victory

In politics, a landslide victory is the victory of a candidate or political party by an overwhelming margin in an election...

in the 1997 general election

United Kingdom general election, 1997

The United Kingdom general election, 1997 was held on 1 May 1997, more than five years after the previous election on 9 April 1992, to elect 659 members to the British House of Commons. The Labour Party ended its 18 years in opposition under the leadership of Tony Blair, and won the general...

under the leadership of Tony Blair

Tony Blair

Anthony Charles Lynton Blair is a former British Labour Party politician who served as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 2 May 1997 to 27 June 2007. He was the Member of Parliament for Sedgefield from 1983 to 2007 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1994 to 2007...

, its first general election victory since October 1974

United Kingdom general election, October 1974

The United Kingdom general election of October 1974 took place on 10 October 1974 to elect 635 members to the British House of Commons. It was the second general election of that year and resulted in the Labour Party led by Harold Wilson, winning by a tiny majority of 3 seats.The election of...

and the first general election since 1970

United Kingdom general election, 1970

The United Kingdom general election of 1970 was held on 18 June 1970, and resulted in a surprise victory for the Conservative Party under leader Edward Heath, who defeated the Labour Party under Harold Wilson. The election also saw the Liberal Party and its new leader Jeremy Thorpe lose half their...

in which it had exceeded 40% of the popular vote. The party's large majority in the House of Commons was slightly reduced to 167 in the 2001 general election

United Kingdom general election, 2001

The United Kingdom general election, 2001 was held on Thursday 7 June 2001 to elect 659 members to the British House of Commons. It was dubbed "the quiet landslide" by the media, as the Labour Party was re-elected with another landslide result and only suffered a net loss of 6 seats...

and more substantially reduced to 66 in 2005

United Kingdom general election, 2005

The United Kingdom general election of 2005 was held on Thursday, 5 May 2005 to elect 646 members to the British House of Commons. The Labour Party under Tony Blair won its third consecutive victory, but with a majority of 66, reduced from 160....

.

Founding of the party

Suffrage

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply the franchise, distinct from mere voting rights, is the civil right to vote gained through the democratic process...

to working-class males, when it became apparent that there was a need for a political party to represent the interests and needs of those groups. Some members of the trade union movement became interested in moving into the political field, and after the extensions of the franchise in 1867 and 1885, the Liberal Party

Liberal Party (UK)

The Liberal Party was one of the two major political parties of the United Kingdom during the 19th and early 20th centuries. It was a third party of negligible importance throughout the latter half of the 20th Century, before merging with the Social Democratic Party in 1988 to form the present day...

endorsed some trade-union sponsored candidates. In addition, several small socialist groups had formed around this time with the intention of linking the movement to political policies. Among these were the Independent Labour Party

Independent Labour Party

The Independent Labour Party was a socialist political party in Britain established in 1893. The ILP was affiliated to the Labour Party from 1906 to 1932, when it voted to leave...

, the intellectual and largely middle-class Fabian Society

Fabian Society

The Fabian Society is a British socialist movement, whose purpose is to advance the principles of democratic socialism via gradualist and reformist, rather than revolutionary, means. It is best known for its initial ground-breaking work beginning late in the 19th century and continuing up to World...

, the Social Democratic Federation

Social Democratic Federation

The Social Democratic Federation was established as Britain's first organised socialist political party by H. M. Hyndman, and had its first meeting on June 7, 1881. Those joining the SDF included William Morris, George Lansbury and Eleanor Marx. However, Friedrich Engels, Karl Marx's long-term...

and the Scottish Labour Party.

In the 1895 General Election

United Kingdom general election, 1895

The United Kingdom general election of 1895 was held from 13 July - 7 August 1895. It was won by the Conservatives led by Lord Salisbury who formed an alliance with the Liberal Unionist Party and had a large majority over the Liberals, led by Lord Rosebery...

the Independent Labour Party put up 28 candidates but won only 44,325 votes. Keir Hardie

Keir Hardie

James Keir Hardie, Sr. , was a Scottish socialist and labour leader, and was the first Independent Labour Member of Parliament elected to the Parliament of the United Kingdom...

, the leader of the party believed that to obtain success in parliamentary elections, it would be necessary to join with other left-wing groups.

Labour Representation Committee

Doncaster

Doncaster is a town in South Yorkshire, England, and the principal settlement of the Metropolitan Borough of Doncaster. The town is about from Sheffield and is popularly referred to as "Donny"...

member of the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants

Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants

The Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants was a trade union of railway workers in the United Kingdom from 1872 until 1913.The ASRS was an industrial union founded in 1871 with the support of the Liberal MP Michael Bass. Its early years were difficult...

, Thomas R. Steels, proposed in his union branch that the Trade Union Congress call a special conference to bring together all the left-wing organisations and form them into a single body which would sponsor Parliamentary candidates. The motion was passed at all stages by the TUC, and this special conference was held at the Memorial Hall, Farringdon Street, London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

on February 26–27, 1900. The meeting was attended by a broad spectrum of working-class and left-wing organisations; trade unions representing about one third of the membership of the TUC delegates.

After a debate the 129 delegates passed Hardie's motion to establish "a distinct Labour group in Parliament, who shall have their own whips, and agree upon their policy, which must embrace a readiness to cooperate with any party which for the time being may be engaged in promoting legislation in the direct interests of labour." This created an association called the Labour Representation Committee (LRC), meant to coordinate attempts to support MPs, MPs sponsored by trade unions and representing the working-class population. It had no single leader. In the absence of one, the Independent Labour Party nominee Ramsay MacDonald

Ramsay MacDonald

James Ramsay MacDonald, PC, FRS was a British politician who was the first ever Labour Prime Minister, leading a minority government for two terms....

was elected as Secretary. He had the difficult task of keeping the various strands of opinions in the LRC united. The October 1900 "Khaki election" came too soon for the new party to effectively campaign. Only 15 candidatures were sponsored, but two were successful: Keir Hardie

Keir Hardie

James Keir Hardie, Sr. , was a Scottish socialist and labour leader, and was the first Independent Labour Member of Parliament elected to the Parliament of the United Kingdom...

in Merthyr Tydfil

Merthyr Tydfil (UK Parliament constituency)

Merthyr Tydfil was a parliamentary constituency centred on the town of Merthyr Tydfil in Glamorgan. From 1832 to 1868 it returned one Member of Parliament to the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, and in 1868 this was increased to two members...

and Richard Bell

Richard Bell (politician)

Richard Bell was one of the first two British Labour Members of Parliament, and the first English one, elected after the formation of the Labour Representation Committee in 1900....

in Derby

Derby (UK Parliament constituency)

Derby is a former United Kingdom Parliamentary constituency. It was a constituency of the House of Commons of the Parliament of England then of the Parliament of Great Britain from 1707 to 1800 and of the Parliament of the United Kingdom from 1801 to 1950. It was represented by two Members of...

.

Support for the LRC was boosted by the 1901 Taff Vale Case

Taff Vale Case

Taff Vale Railway Co v Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants [1901] , commonly known as the Taff Vale case is a formative case in UK labour law...

, a dispute between strikers and a railway company that ended with the union ordered to pay £23,000 damages for a strike

Strike action

Strike action, also called labour strike, on strike, greve , or simply strike, is a work stoppage caused by the mass refusal of employees to work. A strike usually takes place in response to employee grievances. Strikes became important during the industrial revolution, when mass labour became...

. The judgement effectively made strikes illegal since employers could recoup the cost of lost business from the unions. The apparent acquiescence of the Conservative government of Arthur Balfour

Arthur Balfour

Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour, KG, OM, PC, DL was a British Conservative politician and statesman...

to industrial and business interests (traditionally the allies of the Liberal Party

Liberal Party (UK)

The Liberal Party was one of the two major political parties of the United Kingdom during the 19th and early 20th centuries. It was a third party of negligible importance throughout the latter half of the 20th Century, before merging with the Social Democratic Party in 1988 to form the present day...

in opposition to the Conservative's landed interests) intensified support for the LRC against a government that appeared to have little concern for the industrial proletariat and its problems. The LRC won two by-elections in 1902–1903.

United Kingdom general election, 1906

-Seats summary:-See also:*MPs elected in the United Kingdom general election, 1906*The Parliamentary Franchise in the United Kingdom 1885-1918-External links:***-References:*F. W. S. Craig, British Electoral Facts: 1832-1987**...

, the LRC won 29 seats — helped by the secret 1903 pact between Ramsay Macdonald

Ramsay MacDonald

James Ramsay MacDonald, PC, FRS was a British politician who was the first ever Labour Prime Minister, leading a minority government for two terms....

and Liberal

Liberal Party (UK)

The Liberal Party was one of the two major political parties of the United Kingdom during the 19th and early 20th centuries. It was a third party of negligible importance throughout the latter half of the 20th Century, before merging with the Social Democratic Party in 1988 to form the present day...

Chief Whip Herbert Gladstone, which aimed at avoiding Labour/Liberal contests in the interest of removing the Conservatives from office.

In their first meeting after the election, the group's Members of Parliament decided to adopt the name "The Labour Party" (February 15, 1906). Keir Hardie, who had taken a leading role in getting the party established, was elected as Chairman of the Parliamentary Labour Party (in effect, the Leader), although only by one vote over David Shackleton

David Shackleton

Sir David James Shackleton was a cotton worker and trade unionist who became the third Labour Member of Parliament in the United Kingdom, following the formation of the Labour Representation Committee. He later became a senior civil servant....

after several ballots. In the party's early years, the Independent Labour Party

Independent Labour Party

The Independent Labour Party was a socialist political party in Britain established in 1893. The ILP was affiliated to the Labour Party from 1906 to 1932, when it voted to leave...

(ILP) provided much of its activist base as the party did not have an individual membership until 1918 and operated as a conglomerate of affiliated bodies until that date. The Fabian Society

Fabian Society

The Fabian Society is a British socialist movement, whose purpose is to advance the principles of democratic socialism via gradualist and reformist, rather than revolutionary, means. It is best known for its initial ground-breaking work beginning late in the 19th century and continuing up to World...

provided much of the intellectual stimulus for the party. One of the first acts of the new Liberal government was to reverse the Taff Vale judgement.

World War I and the lead up to the first Labour government (1914-1923)

During the First World WarWorld War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

the Labour Party split between supporters and opponents of the conflict and opposition within the party to the war grew as time went on. Ramsay MacDonald

Ramsay MacDonald

James Ramsay MacDonald, PC, FRS was a British politician who was the first ever Labour Prime Minister, leading a minority government for two terms....

, a notable anti-war campaigner, resigned as leader of the Parliamentary Labour Party and Arthur Henderson

Arthur Henderson

Arthur Henderson was a British iron moulder and Labour politician. He was the 1934 Nobel Peace Prize Laureate and he served three short terms as the Leader of the Labour Party from 1908–1910, 1914–1917 and 1931-1932....

became the main figure of authority within the Party and was soon accepted into H. H. Asquith

H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, KG, PC, KC served as the Liberal Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1908 to 1916...

's War Cabinet.

Despite mainstream Labour Party's support for the Coalition, the Independent Labour Party

Independent Labour Party

The Independent Labour Party was a socialist political party in Britain established in 1893. The ILP was affiliated to the Labour Party from 1906 to 1932, when it voted to leave...

was instrumental in opposing mobilisation through organisations such as the Non-Conscription Fellowship and a Labour Party affiliate, the British Socialist Party

British Socialist Party

The British Socialist Party was a Marxist political organisation established in Great Britain in 1911. Following a protracted period of factional struggle, in 1916 the party's anti-war forces gained decisive control of the party and saw the defection of its pro-war Right Wing...

organised a number of unofficial strikes

Strike action

Strike action, also called labour strike, on strike, greve , or simply strike, is a work stoppage caused by the mass refusal of employees to work. A strike usually takes place in response to employee grievances. Strikes became important during the industrial revolution, when mass labour became...

.

Arthur Henderson

Arthur Henderson

Arthur Henderson was a British iron moulder and Labour politician. He was the 1934 Nobel Peace Prize Laureate and he served three short terms as the Leader of the Labour Party from 1908–1910, 1914–1917 and 1931-1932....

resigned from the Cabinet in 1917 amidst calls for Party unity, being replaced by George Barnes

George Nicoll Barnes

George Nicoll Barnes CH PC was a Scottish politician and a leader of the Labour Party.Barnes was born in Lochee, Dundee, the second of five sons of James Barnes, a skilled engineer and mill manager from Yorkshire, and his wife, Catherine Adam Langlands...

. The growth in Labour's local activist base and organisation was reflected in the elections following the War, with the co-operative movement now providing its own resources to the Co-operative Party

Co-operative Party

The Co-operative Party is a centre-left political party in the United Kingdom committed to supporting and representing co-operative principles. The party does not put up separate candidates for any UK election itself. Instead, Co-operative candidates stand jointly with the Labour Party as "Labour...

after the armistice. The Co-operative Party later reached an electoral agreement with the Labour Party.

The Liberal Party splitting between supporters of leader David Lloyd George and former leader H. H. Asquith

H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, KG, PC, KC served as the Liberal Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1908 to 1916...

allowed the Labour Party to co-opt some of the Liberals' support, and by the 1922 general election

United Kingdom general election, 1922

The United Kingdom general election of 1922 was held on 15 November 1922. It was the first election held after most of the Irish counties left the United Kingdom to form the Irish Free State, and was won by Andrew Bonar Law's Conservatives, who gained an overall majority over Labour, led by John...

Labour had supplanted the Liberal Party

Liberal Party (UK)

The Liberal Party was one of the two major political parties of the United Kingdom during the 19th and early 20th centuries. It was a third party of negligible importance throughout the latter half of the 20th Century, before merging with the Social Democratic Party in 1988 to form the present day...

as the second party in the United Kingdom and as the official opposition to the Conservatives

Conservative Party (UK)

The Conservative Party, formally the Conservative and Unionist Party, is a centre-right political party in the United Kingdom that adheres to the philosophies of conservatism and British unionism. It is the largest political party in the UK, and is currently the largest single party in the House...

. After the election, the now rehabilitated Ramsay MacDonald was voted the first official leader of the Labour Party.

Labour's electoral base resided in the industrial areas of Northern England

Northern England

Northern England, also known as the North of England, the North or the North Country, is a cultural region of England. It is not an official government region, but rather an informal amalgamation of counties. The southern extent of the region is roughly the River Trent, while the North is bordered...

, the Midlands

English Midlands

The Midlands, or the English Midlands, is the traditional name for the area comprising central England that broadly corresponds to the early medieval Kingdom of Mercia. It borders Southern England, Northern England, East Anglia and Wales. Its largest city is Birmingham, and it was an important...

, central Scotland

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

and Wales

Wales

Wales is a country that is part of the United Kingdom and the island of Great Britain, bordered by England to its east and the Atlantic Ocean and Irish Sea to its west. It has a population of three million, and a total area of 20,779 km²...

. In these areas Labour Clubs were founded to provide recreation for working men, with many of these clubs becoming affiliated to The Working Men's Club and Institute Union. Because of the concentrated geographical nature of Labour's support, industrial downturns tended to hit Labour voters directly. Anecdotal evidence suggests that party membership was often working-class but also included many middle-class radicals, former liberals and socialists. Accordingly, the more middle-class branches in London and the South of England tended to be more left-wing and radical than those in the primary industrial areas.

First Labour governments under Ramsay MacDonald

The first Labour government (1924)

The 1923 general electionUnited Kingdom general election, 1923

-Seats summary:-References:*F. W. S. Craig, British Electoral Facts: 1832-1987*-External links:***...

was fought on the Conservatives' protectionist proposals; although they got the most votes and remained the largest party, they lost their majority in parliament, requiring a government supporting free trade

Free trade

Under a free trade policy, prices emerge from supply and demand, and are the sole determinant of resource allocation. 'Free' trade differs from other forms of trade policy where the allocation of goods and services among trading countries are determined by price strategies that may differ from...

to be formed. So with the acquiescence of Asquith's Liberals, Ramsay MacDonald

Ramsay MacDonald

James Ramsay MacDonald, PC, FRS was a British politician who was the first ever Labour Prime Minister, leading a minority government for two terms....

became Prime Minister in January 1924 and formed the first ever Labour government, despite Labour only having 191 MPs (less than a third of the House of Commons).

Because the government had to rely on the support of the Liberals, it was unable to get any socialist legislation passed by the House of Commons. The only significant measure was the Wheatley Housing Act which began a building programme of 500,000 homes for rent to working-class families.

The government collapsed after only nine months when the Liberals voted for a Select Committee inquiry into the Campbell Case, a vote which MacDonald had declared to be a vote of confidence. The ensuing general election

United Kingdom general election, 1924

- Seats summary :- References :* F. W. S. Craig, British Electoral Facts: 1832-1987* - External links :* * *...

saw the publication, four days before polling day, of the notorious Zinoviev letter

Zinoviev Letter

The "Zinoviev Letter" refers to a controversial document published by the British press in 1924, allegedly sent from the Communist International in Moscow to the Communist Party of Great Britain...

, which implicated Labour in a plot for a Communist revolution in Britain, and the Conservatives were returned to power, although Labour increased its vote from 30.7% of the popular vote to a third of the popular vote - most of the Conservative gains were at the expense of the Liberals. The Zinoviev letter is now generally believed to have been a forgery.

The General Strike (1926)

The new Conservative government led by Stanley BaldwinStanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley, KG, PC was a British Conservative politician, who dominated the government in his country between the two world wars...

faced a number of labour problems most notably the General Strike of 1926

UK General Strike of 1926

The 1926 general strike in the United Kingdom was a general strike that lasted nine days, from 4 May 1926 to 13 May 1926. It was called by the general council of the Trades Union Congress in an unsuccessful attempt to force the British government to act to prevent wage reduction and worsening...

. Ramsay MacDonald continued with his policy of opposing strike action

Strike action

Strike action, also called labour strike, on strike, greve , or simply strike, is a work stoppage caused by the mass refusal of employees to work. A strike usually takes place in response to employee grievances. Strikes became important during the industrial revolution, when mass labour became...

, including the General Strike

General strike