History of Louisville, Kentucky

Encyclopedia

History

History is the discovery, collection, organization, and presentation of information about past events. History can also mean the period of time after writing was invented. Scholars who write about history are called historians...

of Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville is the largest city in the U.S. state of Kentucky, and the county seat of Jefferson County. Since 2003, the city's borders have been coterminous with those of the county because of a city-county merger. The city's population at the 2010 census was 741,096...

spans hundreds of years, with thousands of years of human habitation. The area's geography

Geography of Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville is a city in Jefferson County, Kentucky. It is located at the Falls of the Ohio River.Louisville is located at . According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Louisville Metro has a total area of 1,032 km²...

and location on the Ohio River attracted people from the earliest times. The city is located at the Falls of the Ohio River

Falls of the Ohio National Wildlife Conservation Area

The Falls of the Ohio National Wildlife Conservation Area is a national, bi-state area on the Ohio River near Louisville, Kentucky in the United States, administered by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Federal status was awarded in 1981.- Overview :...

. The rapids created a barrier to river travel, and settlements grew up at this pausing point.

Louisville has been the site of many important innovations through history. Notable residents have included inventor Thomas Edison

Thomas Edison

Thomas Alva Edison was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices that greatly influenced life around the world, including the phonograph, the motion picture camera, and a long-lasting, practical electric light bulb. In addition, he created the world’s first industrial...

, U.S. Supreme Court

Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest court in the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all state and federal courts, and original jurisdiction over a small range of cases...

Justice Louis Brandeis

Louis Brandeis

Louis Dembitz Brandeis ; November 13, 1856 – October 5, 1941) was an Associate Justice on the Supreme Court of the United States from 1916 to 1939.He was born in Louisville, Kentucky, to Jewish immigrant parents who raised him in a secular mode...

, boxing

Boxing

Boxing, also called pugilism, is a combat sport in which two people fight each other using their fists. Boxing is supervised by a referee over a series of between one to three minute intervals called rounds...

legend Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali is an American former professional boxer, philanthropist and social activist...

, newscaster Diane Sawyer

Diane Sawyer

Lila Diane Sawyer is the current anchor of ABC News' flagship program, ABC World News. Previously, Sawyer had been co-anchor of ABC Newss morning news program, Good Morning America ....

, actor Tom Cruise

Tom Cruise

Thomas Cruise Mapother IV , better known as Tom Cruise, is an American film actor and producer. He has been nominated for three Academy Awards and he has won three Golden Globe Awards....

, the Speed family (including U.S. Attorney General

United States Attorney General

The United States Attorney General is the head of the United States Department of Justice concerned with legal affairs and is the chief law enforcement officer of the United States government. The attorney general is considered to be the chief lawyer of the U.S. government...

James Speed

James Speed

James Speed was an American lawyer, politician and professor. In 1864, he was appointed by Abraham Lincoln to be the United States' Attorney General. He previously served in the Kentucky Legislature, and in local political office.Speed was born in Jefferson County, Kentucky, to Judge John Speed...

and Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. He successfully led his country through a great constitutional, military and moral crisis – the American Civil War – preserving the Union, while ending slavery, and...

's close friend Joshua Fry Speed

Joshua Fry Speed

Joshua Fry Speed was a close friend of Abraham Lincoln from his days in Springfield, Illinois, where Speed was a partner in a general store...

), the Bingham family, industrialist/politician James Guthrie, U.S. Senate Minority Leader

Party leaders of the United States Senate

The Senate Majority and Minority Leaders are two United States Senators who are elected by the party conferences that hold the majority and the minority respectively. These leaders serve as the chief Senate spokespeople for their parties and manage and schedule the legislative and executive...

Mitch McConnell

Mitch McConnell

Addison Mitchell "Mitch" McConnell, Jr. is the senior United States Senator from Kentucky and the Republican Minority Leader.- Early life, education, and military service :...

and writers Hunter S. Thompson

Hunter S. Thompson

Hunter Stockton Thompson was an American journalist and author who wrote The Rum Diary , Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas and Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail '72 .He is credited as the creator of Gonzo journalism, a style of reporting where reporters involve themselves in the action to...

and Sue Grafton

Sue Grafton

Sue Taylor Grafton is a contemporary American author of detective novels. She is best known as the author of the 'alphabet series' featuring private investigator Kinsey Millhone in the fictional city of Santa Teresa, California. The daughter of detective novelist C. W...

.

Notable events occurring in the city include the largest installation to date (in 1883)

Southern Exposition

The Southern Exposition was a five-year series of World's Fairs held in the city of Louisville, Kentucky from 1883 to 1887 in what is now Louisville's Old Louisville neighborhood. The exposition, held for 100 days each year on immediately south of Central Park, which is now the St....

and first large space lighted by Edison's light bulb

Incandescent light bulb

The incandescent light bulb, incandescent lamp or incandescent light globe makes light by heating a metal filament wire to a high temperature until it glows. The hot filament is protected from air by a glass bulb that is filled with inert gas or evacuated. In a halogen lamp, a chemical process...

and the first library in the South open to African American

African American

African Americans are citizens or residents of the United States who have at least partial ancestry from any of the native populations of Sub-Saharan Africa and are the direct descendants of enslaved Africans within the boundaries of the present United States...

s. Medical advances included the first human hand transplant in the United States, the first self-contained artificial heart

Artificial heart

An artificial heart is a mechanical device that replaces the heart. Artificial hearts are typically used in order to bridge the time to heart transplantation, or to permanently replace the heart in case transplantation is impossible...

transplant, and development of the first cervical cancer vaccine

Gardasil

Gardasil , also known as Gardisil or Silgard, is a vaccine for use in the prevention of certain types of human papillomavirus , specifically HPV types 6, 11, 16 and 18. HPV types 16 and 18 cause an estimated 70% of cervical cancers, and are responsible for most HPV-induced anal, vulvar, vaginal,...

.

Pre-Anglo-American settlement history (pre-1778)

There was a continuous human presence in the area that became Louisville from at least 1,000 BCE until roughly 1650 CECommon Era

Common Era ,abbreviated as CE, is an alternative designation for the calendar era originally introduced by Dionysius Exiguus in the 6th century, traditionally identified with Anno Domini .Dates before the year 1 CE are indicated by the usage of BCE, short for Before the Common Era Common Era...

. Archeologists have identified several late and one early Archaic sites in Jefferson County's wetlands. One of the most extensive finds was at McNeeley Lake Cave; many others were found around the Louisville International Airport

Louisville International Airport

Louisville International Airport is a joint civil-military public airport centrally located in the city of Louisville in Jefferson County, Kentucky, USA. The airport covers 1,200 acres and has three runways. Its IATA airport code SDF is based on the airport's former name, Standiford Field...

area. People of the Adena culture

Adena culture

The Adena culture was a Pre-Columbian Native American culture that existed from 1000 to 200 BC, in a time known as the early Woodland Period. The Adena culture refers to what were probably a number of related Native American societies sharing a burial complex and ceremonial system...

and the Hopewell tradition that followed it lived in the area, with hunting villages along Mill Creek and a large village near what became Zorn Avenue, on bluffs overlooking the Ohio River. Archeologists have found 30 Jefferson County sites associated with the Fort Ancient

Fort Ancient

Fort Ancient is a name for a Native American culture that flourished from 1000-1750 CE among a people who predominantly inhabited land along the Ohio River in areas of modern-day Southern Ohio, Northern Kentucky, Southeastern Indiana and Western West Virginia. They were a maize based agricultural...

and Mississippian culture

Mississippian culture

The Mississippian culture was a mound-building Native American culture that flourished in what is now the Midwestern, Eastern, and Southeastern United States from approximately 800 CE to 1500 CE, varying regionally....

s, which were active from 1,000 CE until about 1650. The Louisville area was on the eastern border of the Mississippian culture, in which regional chiefdom

Chiefdom

A chiefdom is a political economy that organizes regional populations through a hierarchy of the chief.In anthropological theory, one model of human social development rooted in ideas of cultural evolution describes a chiefdom as a form of social organization more complex than a tribe or a band...

s built villages and cities with extensive earthwork mounds

Earthworks (archaeology)

In archaeology, earthwork is a general term to describe artificial changes in land level. Earthworks are often known colloquially as 'lumps and bumps'. Earthworks can themselves be archaeological features or they can show features beneath the surface...

.

When European and English explorers and settlers began entering Kentucky in the mid-18th century, there were no permanent Native American settlements in the region. The country was used as hunting grounds by Shawnee

Shawnee

The Shawnee, Shaawanwaki, Shaawanooki and Shaawanowi lenaweeki, are an Algonquian-speaking people native to North America. Historically they inhabited the areas of Ohio, Virginia, West Virginia, Western Maryland, Kentucky, Indiana, and Pennsylvania...

s from the north and Cherokee

Cherokee

The Cherokee are a Native American people historically settled in the Southeastern United States . Linguistically, they are part of the Iroquoian language family...

s from the south.

The first European to visit the area was the French

French people

The French are a nation that share a common French culture and speak the French language as a mother tongue. Historically, the French population are descended from peoples of Celtic, Latin and Germanic origin, and are today a mixture of several ethnic groups...

explorer, René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle

René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle

René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, or Robert de LaSalle was a French explorer. He explored the Great Lakes region of the United States and Canada, the Mississippi River, and the Gulf of Mexico...

in 1669. He explored areas of the Mississippi

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the largest river system in North America. Flowing entirely in the United States, this river rises in western Minnesota and meanders slowly southwards for to the Mississippi River Delta at the Gulf of Mexico. With its many tributaries, the Mississippi's watershed drains...

and Ohio

Ohio River

The Ohio River is the largest tributary, by volume, of the Mississippi River. At the confluence, the Ohio is even bigger than the Mississippi and, thus, is hydrologically the main stream of the whole river system, including the Allegheny River further upstream...

river valleys

Valley

In geology, a valley or dale is a depression with predominant extent in one direction. A very deep river valley may be called a canyon or gorge.The terms U-shaped and V-shaped are descriptive terms of geography to characterize the form of valleys...

from the Gulf of Mexico

Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico is a partially landlocked ocean basin largely surrounded by the North American continent and the island of Cuba. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United States, on the southwest and south by Mexico, and on the southeast by Cuba. In...

up to modern-day Canada

Canada

Canada is a North American country consisting of ten provinces and three territories. Located in the northern part of the continent, it extends from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the Pacific Ocean in the west, and northward into the Arctic Ocean...

, claiming much of this land for France.

In 1751, the English

English people

The English are a nation and ethnic group native to England, who speak English. The English identity is of early mediaeval origin, when they were known in Old English as the Anglecynn. England is now a country of the United Kingdom, and the majority of English people in England are British Citizens...

colonist Christopher Gist

Christopher Gist

Christopher Gist was an accomplished American explorer, surveyor and frontiersman. He was one of the first white explorers of the Ohio Country . He is credited with providing the first detailed description of the Ohio Country to Great Britain and her colonists...

explored areas along the Ohio River. Following its defeat in the French and Indian War

French and Indian War

The French and Indian War is the common American name for the war between Great Britain and France in North America from 1754 to 1763. In 1756, the war erupted into the world-wide conflict known as the Seven Years' War and thus came to be regarded as the North American theater of that war...

(part of the Seven Years War in Europe), France relinquished control of the area of Kentucky to England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

.

In 1769, colonist Daniel Boone

Daniel Boone

Daniel Boone was an American pioneer, explorer, and frontiersman whose frontier exploits mad']'e him one of the first folk heroes of the United States. Boone is most famous for his exploration and settlement of what is now the Commonwealth of Kentucky, which was then beyond the western borders of...

created a trail from North Carolina

North Carolina

North Carolina is a state located in the southeastern United States. The state borders South Carolina and Georgia to the south, Tennessee to the west and Virginia to the north. North Carolina contains 100 counties. Its capital is Raleigh, and its largest city is Charlotte...

to Tennessee

Tennessee

Tennessee is a U.S. state located in the Southeastern United States. It has a population of 6,346,105, making it the nation's 17th-largest state by population, and covers , making it the 36th-largest by total land area...

. He spent the next two years exploring Kentucky. In 1773, Captain Thomas Bullitt

Thomas Bullitt

Thomas Bullitt was an United States soldier and pioneer from Prince William County, Virginia.Thomas was born to Benjamin and Sarah Bullitt abut 1734 in Prince William County of Virginia. He became active in the militia when young, and became interested in western exploration and development...

led the first exploring party into Jefferson County

Jefferson County, Kentucky

As of the census of 2000, there were 693,604 people, 287,012 households, and 183,113 families residing in the county. The population density was . There were 305,835 housing units at an average density of...

, surveying land on behalf of Virginians who had been awarded land grant

Land grant

A land grant is a gift of real estate – land or its privileges – made by a government or other authority as a reward for services to an individual, especially in return for military service...

s for service in the French and Indian War

French and Indian War

The French and Indian War is the common American name for the war between Great Britain and France in North America from 1754 to 1763. In 1756, the war erupted into the world-wide conflict known as the Seven Years' War and thus came to be regarded as the North American theater of that war...

. In 1774, James Harrod

James Harrod

James Harrod was a pioneer, soldier, and hunter who helped explore and settle the area west of the Allegheny Mountains. Little is known about Harrod's early life, including the exact date of his birth. He was possibly underage when he served in the French and Indian War, and later participated in...

began constructing Fort Harrod in Kentucky. However, battles with the native American tribes established in the area forced these new settlers to retreat. They returned the following year, as Daniel Boone built the Wilderness Road

Wilderness Road

The Wilderness Road was the principal route used by settlers for more than fifty years to reach Kentucky from the East. In 1775, Daniel Boone blazed a trail for the Transylvania Company from Fort Chiswell in Virginia through the Cumberland Gap into central Kentucky. It was later lengthened,...

and established Fort Boonesborough at the site near Boonesborough, Kentucky

Boonesborough, Kentucky

Boonesborough is an unincorporated community in Madison County, Kentucky, United States. It lies in the central part of the state along the Kentucky River. Boonesborough is part of the Richmond–Berea Micropolitan Statistical Area....

. The Native Americans allocated a tract of land between the Ohio River and the Cumberland River

Cumberland River

The Cumberland River is a waterway in the Southern United States. It is long. It starts in Harlan County in far southeastern Kentucky between Pine and Cumberland mountains, flows through southern Kentucky, crosses into northern Tennessee, and then curves back up into western Kentucky before...

for the Transylvania Land Company. In 1776, the colony of Virginia

Virginia

The Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there...

declared the Transylvania Land Company illegal and created the county of Kentucky in Virginia from the land involved.

Foundation and early settlement (1778–1803)

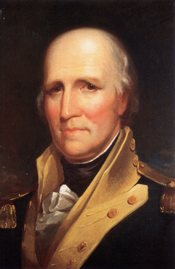

George Rogers Clark

George Rogers Clark was a soldier from Virginia and the highest ranking American military officer on the northwestern frontier during the American Revolutionary War. He served as leader of the Kentucky militia throughout much of the war...

made the first Anglo-American settlement in the vicinity of modern-day Louisville in 1778, during the American Revolutionary War

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War , the American War of Independence, or simply the Revolutionary War, began as a war between the Kingdom of Great Britain and thirteen British colonies in North America, and ended in a global war between several European great powers.The war was the result of the...

. He was conducting a campaign against the British

Kingdom of Great Britain

The former Kingdom of Great Britain, sometimes described as the 'United Kingdom of Great Britain', That the Two Kingdoms of Scotland and England, shall upon the 1st May next ensuing the date hereof, and forever after, be United into One Kingdom by the Name of GREAT BRITAIN. was a sovereign...

in areas north of the Ohio River, then called the Illinois Country

Illinois Country

The Illinois Country , also known as Upper Louisiana, was a region in what is now the Midwestern United States that was explored and settled by the French during the 17th and 18th centuries. The terms referred to the entire Upper Mississippi River watershed, though settlement was concentrated in...

. Clark organized a group of 150 soldiers, known as the Illinois Regiment, after heavy recruiting in Virginia

Virginia

The Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there...

and Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania

The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania is a U.S. state that is located in the Northeastern and Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States. The state borders Delaware and Maryland to the south, West Virginia to the southwest, Ohio to the west, New York and Ontario, Canada, to the north, and New Jersey to...

. On May 12, they set out from Redstone, today's Brownsville, Pennsylvania

Brownsville, Pennsylvania

Brownsville is a borough in Fayette County, Pennsylvania, United States, officially founded in 1785 located 35 miles south of Pittsburgh along the Monongahela River...

, taking along 80 civilians who hoped to claim fertile farmland and start a new settlement in Kentucky. They arrived at the Falls of the Ohio

Falls of the Ohio National Wildlife Conservation Area

The Falls of the Ohio National Wildlife Conservation Area is a national, bi-state area on the Ohio River near Louisville, Kentucky in the United States, administered by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Federal status was awarded in 1981.- Overview :...

on May 27. It was a location Clark thought ideal for a communication post. The settlers helped Clark conceal the true reason for his presence in the area.

The regiment helped the civilians establish a settlement on what came to be called Corn Island

Corn Island (Kentucky)

Corn Island is a now-vanished island in the Ohio River, at head of the Falls of the Ohio, just north of Louisville, Kentucky.-Geography:Estimates of the size of Corn Island vary with time as it gradually was eroded and became submerged. A 1780 survey listed its size at...

, clearing land and building cabins and a springhouse. On June 24, Clark took his soldiers and left to begin their military campaign

Military campaign

In the military sciences, the term military campaign applies to large scale, long duration, significant military strategy plan incorporating a series of inter-related military operations or battles forming a distinct part of a larger conflict often called a war...

. A year later, at the request of Clark, the settlers began crossing the river and established the first permanent settlement. By April they called it "Louisville", in honor of King Louis XVI of France

Louis XVI of France

Louis XVI was a Bourbon monarch who ruled as King of France and Navarre until 1791, and then as King of the French from 1791 to 1792, before being executed in 1793....

, whose government and soldiers aided colonists in the Revolutionary War

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War , the American War of Independence, or simply the Revolutionary War, began as a war between the Kingdom of Great Britain and thirteen British colonies in North America, and ended in a global war between several European great powers.The war was the result of the...

. Today, George Rogers Clark is recognized as the European-American founder of Louisville, and many landmarks are named after him.

During its earliest history, the colony of Louisville and the surrounding areas suffered from Indian attacks, as Native Americans tried to push out the encroaching colonists. As the Revolutionary War was still being waged, all early residents lived within forts, as suggested by the earliest government of Kentucky County, Virginia

Kentucky County, Virginia

Kentucky County was formed by the Commonwealth of Virginia by dividing Fincastle County into three new counties: Kentucky, Washington, and Montgomery, effective December 31, 1776. Four years later Kentucky County was abolished on June 30, 1780, when it was divided into Fayette, Jefferson, and...

. The initial fort, at the northern tip of today's 12th street, was called Fort-on-Shore

Fort-on-Shore

Fort-on-Shore, built in 1778 by William Linn, was the first on-shore fort on the Ohio River in the area of what is now downtown Louisville, Kentucky. George Rogers Clark had directed Linn to move the militia post to the mainland from its original off-shore location at Corn Island...

. In response to the threat of British attacks, particularly Bird's invasion of Kentucky

Bird's invasion of Kentucky

Bird's invasion of Kentucky during the American Revolutionary War was one phase of an extensive planned series of operations planned by the British in 1780, whereby the entire West, from Quebec to the Gulf of Mexico, was to be swept clear of both Spanish and colonial resistance.While Bird's...

, a larger fort called Fort Nelson

Fort Nelson (Kentucky)

Fort Nelson, built in 1781 by Richard Chenoweth, was the second on-shore fort on the Ohio River in the area of what is now downtown Louisville, Kentucky. Fort-on-Shore, the downriver and first on-shore fort, had proved to be insufficient barely three years after it was established...

was built north of today's Main Street between Seventh and Eighth streets, covering nearly an acre. The GB£

Pound sterling

The pound sterling , commonly called the pound, is the official currency of the United Kingdom, its Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands, British Antarctic Territory and Tristan da Cunha. It is subdivided into 100 pence...

15,000 contract was given to Richard Chenoweth, with construction beginning in late 1780 and completed by March 1781. The fort, thought to be capable of resisting cannon fire, was considered the strongest in the west after Fort Pitt

Fort Pitt (Pennsylvania)

Fort Pitt was a fort built at the location of Pittsburgh, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania.-French and Indian War:The fort was built from 1759 to 1761 during the French and Indian War , next to the site of former Fort Duquesne, at the confluence the Allegheny River and the Monongahela River...

. Due to decreasing need for strong forts after the Revolutionary War, it was in decline by the end of the decade.

Virginia General Assembly

The Virginia General Assembly is the legislative body of the Commonwealth of Virginia, and the oldest legislative body in the Western Hemisphere, established on July 30, 1619. The General Assembly is a bicameral body consisting of a lower house, the Virginia House of Delegates, with 100 members,...

and then-Governor

Governor of Virginia

The governor of Virginia serves as the chief executive of the Commonwealth of Virginia for a four-year term. The position is currently held by Republican Bob McDonnell, who was inaugurated on January 16, 2010, as the 71st governor of Virginia....

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson was the principal author of the United States Declaration of Independence and the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom , the third President of the United States and founder of the University of Virginia...

approved the town charter of Louisville on May 1. Clark recruited early Kentucky pioneer James John Floyd

James John Floyd

James John Floyd , better known as John Floyd, was a pioneer of the Midwestern United States around the Louisville, Kentucky area where he worked as a surveyor for land development and as a military figure. Floyd was an early settler of St. Matthews, Kentucky and helped lay out Louisville...

, who was placed on the town's board of trustees and given the authority to plan and lay out the town. Jefferson County, named after Thomas Jefferson, was formed at this time as one of three original Kentucky counties from the old Kentucky County, Virginia

Kentucky County, Virginia

Kentucky County was formed by the Commonwealth of Virginia by dividing Fincastle County into three new counties: Kentucky, Washington, and Montgomery, effective December 31, 1776. Four years later Kentucky County was abolished on June 30, 1780, when it was divided into Fayette, Jefferson, and...

. Louisville was the county seat

County seat

A county seat is an administrative center, or seat of government, for a county or civil parish. The term is primarily used in the United States....

.

Daniel Brodhead IV

Daniel Brodhead IV was an American military and political leader during the American Revolutionary War and early days of the United States.-Early life:...

opened Louisville's first general store

General store

A general store, general merchandise store, or village shop is a rural or small town store that carries a general line of merchandise. It carries a broad selection of merchandise, sometimes in a small space, where people from the town and surrounding rural areas come to purchase all their general...

in 1783. He became the first to move out of Louisville's early forts. James John Floyd became the first Judge in 1783 but was killed later that year. The first courthouse was completed in 1784 as a 16 by 20 feet (6.1 m) log cabin

Log cabin

A log cabin is a house built from logs. It is a fairly simple type of log house. A distinction should be drawn between the traditional meanings of "log cabin" and "log house." Historically most "Log cabins" were a simple one- or 1½-story structures, somewhat impermanent, and less finished or less...

. By this time, Louisville contained 63 clapboard finished houses, 37 partly finished, 22 uncovered houses, and over 100 log cabins. Shippingport

Shippingport, Kentucky

Shippingport, Kentucky is an industrial site and former settlement near Louisville, Kentucky on a peninsula near the Falls of the Ohio. It was incorporated without a name on October 10, 1785, then became Campbell Town after Revolutionary War soldier John Campbell, who had been granted the land for...

, incorporated in 1785, was a vital part of early Louisville, allowing goods to be transported through the Falls of the Ohio. The first church was built in 1790, the first hotel in 1793, and the first post office in 1795. During the 1780s and early 1790s, the town was not growing as fast as Lexington in central Kentucky. Factors were the threat of Indian attacks (ended in 1794 by the Battle of Fallen Timbers

Battle of Fallen Timbers

The Battle of Fallen Timbers was the final battle of the Northwest Indian War, a struggle between American Indian tribes affiliated with the Western Confederacy and the United States for control of the Northwest Territory...

), a complicated dispute over land ownership between John Campbell and the town's trustees (resolved in 1785), and Spanish policies restricting trade down the Mississippi

Mississippi

Mississippi is a U.S. state located in the Southern United States. Jackson is the state capital and largest city. The name of the state derives from the Mississippi River, which flows along its western boundary, whose name comes from the Ojibwe word misi-ziibi...

to New Orleans. By 1800, the population of Louisville was 359 compared to Lexington's 1,759.

From 1784 through 1792, a series of conventions were held to discuss the separation of Kentucky from Virginia. On June 1, 1792, Kentucky became the fifteenth state in the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

and Isaac Shelby

Isaac Shelby

Isaac Shelby was the first and fifth Governor of the U.S. state of Kentucky and served in the state legislatures of Virginia and North Carolina. He was also a soldier in Lord Dunmore's War, the Revolutionary War, and the War of 1812...

was named the first Governor.

Meriwether Lewis

Meriwether Lewis was an American explorer, soldier, and public administrator, best known for his role as the leader of the Lewis and Clark Expedition also known as the Corps of Discovery, with William Clark...

and William Clark organized their expedition across North America at the Falls of the Ohio and Louisville. The Lewis and Clark Expedition

Lewis and Clark Expedition

The Lewis and Clark Expedition, or ″Corps of Discovery Expedition" was the first transcontinental expedition to the Pacific Coast by the United States. Commissioned by President Thomas Jefferson and led by two Virginia-born veterans of Indian wars in the Ohio Valley, Meriwether Lewis and William...

would take the explorers across the western U.S., surveying the Louisiana Purchase

Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase was the acquisition by the United States of America of of France's claim to the territory of Louisiana in 1803. The U.S...

, and eventually to the Pacific Ocean

Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest of the Earth's oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic in the north to the Southern Ocean in the south, bounded by Asia and Australia in the west, and the Americas in the east.At 165.2 million square kilometres in area, this largest division of the World...

.

Antebellum

Since settlement, all people and cargo had arrived by flatboatFlatboat

Fil1800flatboat.jpgA flatboat is a rectangular flat-bottomed boat with Fil1800flatboat.jpgA flatboat is a rectangular flat-bottomed boat with Fil1800flatboat.jpgA flatboat is a rectangular flat-bottomed boat with (mostlyNOTE: "(parenthesized)" wordings in the quote below are notes added to...

s and later keelboat

Keelboat

Keelboat has two distinct meanings related to two different types of boats: one a riverine cargo-capable working boat, and the other a classification for small- to mid-sized recreational sailing yachts.-Historical keel-boats:...

s, both of which were non-motorized vessels, meaning that it was prohibitively costly to send goods upstream (towards Pittsburgh and other developed areas). This technical limitation, combined with the Spanish decision in 1784 to close the Mississippi River

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the largest river system in North America. Flowing entirely in the United States, this river rises in western Minnesota and meanders slowly southwards for to the Mississippi River Delta at the Gulf of Mexico. With its many tributaries, the Mississippi's watershed drains...

below Vicksburg, Mississippi

Vicksburg, Mississippi

Vicksburg is a city in Warren County, Mississippi, United States. It is the only city in Warren County. It is located northwest of New Orleans on the Mississippi and Yazoo rivers, and due west of Jackson, the state capital. In 1900, 14,834 people lived in Vicksburg; in 1910, 20,814; in 1920,...

to American ships, meant there was very little outside market for goods produced early on in Louisville. This improved somewhat with Pinckney's Treaty

Pinckney's Treaty

Pinckney's Treaty, also known as the Treaty of San Lorenzo or the Treaty of Madrid, was signed in San Lorenzo de El Escorial on October 27, 1795 and established intentions of friendship between the United States and Spain. It also defined the boundaries of the United States with the Spanish...

, which opened the river and made New Orleans a Free trade

Free trade

Under a free trade policy, prices emerge from supply and demand, and are the sole determinant of resource allocation. 'Free' trade differs from other forms of trade policy where the allocation of goods and services among trading countries are determined by price strategies that may differ from...

zone by 1798.

However, most cargo was still being sent downstream in the early 19th century, averaging 60,000 tons downstream to 6,500 tons upstream. Boats passing through still had to unload all of their cargo before navigating the falls, a boon to local businesses. The frontier days quickly fading, log houses and forts began to disappear, and Louisville saw its first newspaper, the Louisville Gazette in 1807 and its first theatre in 1808, and the first dedicated church building in 1809. All of this reflected the 400% growth in population reported by the 1810 Census.

The economics of shipping were about to change, however, with the arrival of steamboat

Steamboat

A steamboat or steamship, sometimes called a steamer, is a ship in which the primary method of propulsion is steam power, typically driving propellers or paddlewheels...

s. The first, the New Orleans

New Orleans (steamboat)

The New Orleans was the first steamboat on the western waters of the United States. Its 1811-1812 voyage from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania to New Orleans, Louisiana on the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers ushered in the era of commercial steamboat navigation on the western rivers.-Background:The New...

arrived in 1811, traveling downstream from Pittsburgh. Although it made the trip in record time

World record

A world record is usually the best global performance ever recorded and verified in a specific skill or sport. The book Guinness World Records collates and publishes notable records of all types, from first and best to worst human achievements, to extremes in the natural world and beyond...

, most believed its use was limited, as they did not believe a steamboat could make it back upriver against the current. However, in 1815, the Enterprise

Enterprise (1814)

The Enterprise, or Enterprize, demonstrated for the first time by her epic 2,200-mile voyage from New Orleans to Pittsburgh that steamboat commerce was practical on America's western rivers.-Early days:...

, captained by Henry Miller Shreve

Henry Miller Shreve

Henry Miller Shreve was the American inventor and steamboat captain who opened the Mississippi, Ohio and Red rivers to steamboat navigation. Shreveport, Louisiana, is named in his honor....

, became the first steamboat to travel from New Orleans to Louisville, showing the commercial potential of the steamboat in making upriver travel and shipping practical.

Industry and manufacturing reached Louisville and surrounding areas, especially Shippingport

Shippingport, Kentucky

Shippingport, Kentucky is an industrial site and former settlement near Louisville, Kentucky on a peninsula near the Falls of the Ohio. It was incorporated without a name on October 10, 1785, then became Campbell Town after Revolutionary War soldier John Campbell, who had been granted the land for...

, at this time. Some steamboats were built in Louisville and many early mills and factories opened. Other towns were developing at the falls: New Albany, Indiana

New Albany, Indiana

New Albany is a city in Floyd County, Indiana, United States, situated along the Ohio River opposite Louisville, Kentucky. In 1900, 20,628 people lived in New Albany; in 1910, 20,629; in 1920, 22,992; and in 1940, 25,414. The population was 36,372 at the 2010 census. The city is the county seat of...

in 1813 and Portland

Portland, Louisville

Portland is a neighborhood and former independent town two miles northwest of downtown Louisville, Kentucky. In its early days it was the largest of the six major settlements at the Falls of the Ohio River, the others being Shippingport and Louisville in Kentucky and New Albany, Clarksville, and...

in 1814, each competing with Louisville to become the dominant settlement in the area. Still, Louisville's population grew rapidly, tripling from 1810 to 1820. By 1830, it would surpass Lexington to become the state's largest city, and would eventually annex Portland and Shippingport.

In 1816 the Louisville Library Company, the city's first library, opened its doors with a subscription-based service. Also, in a series of events ranging from 1798 to 1846, the University of Louisville

University of Louisville

The University of Louisville is a public university in Louisville, Kentucky. When founded in 1798, it was the first city-owned public university in the United States and one of the first universities chartered west of the Allegheny Mountains. The university is mandated by the Kentucky General...

was founded from the Jefferson Seminary

Jefferson Seminary

The Jefferson Seminary was one of Kentucky's first schools and is considered to be the direct ancestor of the University of Louisville.The school was chartered by the Kentucky General Assembly in 1798, with the sale of 6,000 acres of land in rural southern Kentucky used to pay for initial...

, Louisville Medical Institute

Louisville Medical Institute

The Louisville Medical Institute was a medical school founded in 1837 in Louisville, Kentucky. It would be merged with two other colleges into the University of Louisville in 1846 and is considered the ancestor of the university's present day medical school....

and Louisville Collegiate Institute.

In response to great demand, the Louisville and Portland Canal

Louisville and Portland Canal

The Louisville and Portland Canal was a canal bypassing the Falls of the Ohio in the Ohio River near Louisville, Kentucky. It opened in 1830, and was operated by the Louisville and Portland Canal Company until 1874, and became the McAlpine Locks and Dam in 1962 after heavy modernization.Although...

was completed in 1830. This allowed boats to circumvent the Falls of the Ohio and travel through from Pittsburgh to New Orleans. In response to several epidemics and the increasing need to treat ill or injured river workers, Louisville Marine Hospital was completed in 1825 on Chestnut Street, an area that is today home to Louisville's Medical Center.

In 1828, the population surpassed 7,000 and Louisville became Kentucky's first city. John Bucklin

John Bucklin

John Carpenter Bucklin was the first mayor of the city of Louisville. His father, a merchant and sailor, was a captain in the Navy during the Revolutionary War. John Bucklin served in the Rhode Island militia, owned several ships, and married Sarah Smith in 1803...

was elected the first Mayor. The nearby towns of Shippingport and Portland remained independent of Louisville for the time being. City status gave Louisville some judicial authority and the ability to collect more taxes, which allowed for the establishment of the state's first public school in 1829.

In 1831, Catherine Spalding

Catherine Spalding

Catherine Spalding , in 1813, aged nineteen, when no education for girls, no private health care, and no organized social services existed on the Kentucky frontier, was elected leader of six women forming a new religious community, the Sisters of Charity of Nazareth...

moved from Bardstown

Bardstown, Kentucky

As of the census of 2010, there were 11,700 people, 4,712 households, and 2,949 families residing in the city. The population density was . There were 5,113 housing units at an average density of...

to Louisville and established Presentation Academy

Presentation Academy

Presentation Academy, a college-preparatory high school for young women, is located just south of Downtown Louisville, Kentucky in the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Louisville...

, a Catholic

Catholic

The word catholic comes from the Greek phrase , meaning "on the whole," "according to the whole" or "in general", and is a combination of the Greek words meaning "about" and meaning "whole"...

school for girls. She also established the St. Vincent Orphanage, which was later renamed as St. Joseph Orphanage.

Louisville's famous Galt House

Galt House

The Galt House is a 25-story, 1300-room hotel in Louisville, Kentucky. The original hotel was erected in 1837. The current Galt House is presently the city's only hotel on the Ohio River. Many noted people have stayed at the Galt House, including Jefferson Davis, Charles Dickens, Abraham Lincoln...

hotel—the first of three downtown buildings to have that moniker—was erected in 1834. In 1839, a precursor to the modern Kentucky Derby

Kentucky Derby

The Kentucky Derby is a Grade I stakes race for three-year-old Thoroughbred horses, held annually in Louisville, Kentucky, United States on the first Saturday in May, capping the two-week-long Kentucky Derby Festival. The race is one and a quarter mile at Churchill Downs. Colts and geldings carry...

was held at Old Louisville's Oakland Race Course

Race track

A race track is a purpose-built facility for racing of animals , automobiles, motorcycles or athletes. A race track may also feature grandstands or concourses. Some motorsport tracks are called speedways.A racetrack is a permanent facility or building...

. Over 10,000 spectators attended the two-horse race, in which Grey Eagle lost to Wagner. This race occurred 36 years before the first Kentucky Derby. It was a popular competition to test the quality of horses. Louisville became a center for sales of horses and other livestock from the Bluegrass Region

Bluegrass region

The Bluegrass Region is a geographic region in the state of Kentucky, United States. It occupies the northern part of the state and since European settlement has contained a majority of the state's population and its largest cities....

of central Kentucky, where horse breeding became a major part of the economy and traditions.

The Kentucky School for the Blind

Kentucky School for the Blind

The Kentucky School for the Blind is an educational facility for blind and visually impaired students from Kentucky up to age 21.Bryce McLellan Patten founded the Kentucky Institution for the Education of the Blind in 1839 in Louisville, Kentucky...

was founded in 1839, the third-oldest school for the blind in the country.

In 1848, Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor was the 12th President of the United States and an American military leader. Initially uninterested in politics, Taylor nonetheless ran as a Whig in the 1848 presidential election, defeating Lewis Cass...

, resident of Jefferson County from childhood through early adulthood and a hero of the Mexican–American War

Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known as the First American Intervention, the Mexican War, or the U.S.–Mexican War, was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848 in the wake of the 1845 U.S...

, was elected as the 12th President of the United States

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

. He served only sixteen months in office before dying in 1850 from acute gastroenteritis

Gastroenteritis

Gastroenteritis is marked by severe inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract involving both the stomach and small intestine resulting in acute diarrhea and vomiting. It can be transferred by contact with contaminated food and water...

. He was buried in the east end of Louisville at Zachary Taylor National Cemetery

Zachary Taylor National Cemetery

Zachary Taylor National Cemetery, located at 4701 Brownsboro Road , in northeast Louisville, Kentucky is a national cemetery where former President of the United States Zachary Taylor and his first lady Margaret Taylor are buried. Zachary Taylor National Cemetery was listed in the National...

.

Following the 1850 Census

United States Census

The United States Census is a decennial census mandated by the United States Constitution. The population is enumerated every 10 years and the results are used to allocate Congressional seats , electoral votes, and government program funding. The United States Census Bureau The United States Census...

, Louisville was reported as the nation's tenth largest city, while Kentucky

Kentucky

The Commonwealth of Kentucky is a state located in the East Central United States of America. As classified by the United States Census Bureau, Kentucky is a Southern state, more specifically in the East South Central region. Kentucky is one of four U.S. states constituted as a commonwealth...

was reported as the eighth most populous state.

The Louisville and Nashville Railroad

Louisville and Nashville Railroad

The Louisville and Nashville Railroad was a Class I railroad that operated freight and passenger services in the southeast United States.Chartered by the state of Kentucky in 1850, the L&N, as it was generally known, grew into one of the great success stories of American business...

(L&N) Company was founded in 1850 by James Guthrie, who also was involved in the founding of the University of Louisville. When the railroad was completed in 1859, Louisville's strategic location at the Falls of the Ohio became central to the city's development and importance in the rail and water freight transportation business.

Bloody Monday

Bloody Monday was the name given the election riots of August 6, 1855, in Louisville, Kentucky. These riots grew out of the bitter rivalry between the Democrats and supporters of the Know-Nothing Party. Rumors were started that foreigners and Catholics had interfered with the process of voting...

, election

Election

An election is a formal decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual to hold public office. Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy operates since the 17th century. Elections may fill offices in the legislature, sometimes in the...

riots stemming from the bitter rivalry between the Democrats

Democratic Party (United States)

The Democratic Party is one of two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Republican Party. The party's socially liberal and progressive platform is largely considered center-left in the U.S. political spectrum. The party has the lengthiest record of continuous...

and supporters of the Know-Nothing Party

Know Nothing

The Know Nothing was a movement by the nativist American political faction of the 1840s and 1850s. It was empowered by popular fears that the country was being overwhelmed by German and Irish Catholic immigrants, who were often regarded as hostile to Anglo-Saxon Protestant values and controlled by...

broke out. Know-Nothing mobs rioted in Irish

History of the Irish in Louisville

The history of the Irish in Louisville is a long one as involvement of Irish in Louisville, Kentucky dates to the founding of the city. The two major waves of Irish influence on Louisville were first the Scots-Irish in the late 18th century, and those who escaped from the Irish Potato Famine of...

and German

History of the Germans in Louisville

The history of the Germans in Louisville began in 1787. In that year, a man named Kaye built the first brick house in Louisville, Kentucky. The Blankenbaker, Bruner, and Funk families came to the Louisville region following the American Revolutionary War, and in 1797 they founded the town...

parts of the city, destroying property by fires and killing numerous people.

Founded in 1858, the American Printing House for the Blind is the oldest organization of its kind in the United States. Since 1879 it has been the official supplier of educational materials for blind students in the U.S. It is located on Frankfort Avenue in the Clifton neighborhood

Clifton, Louisville

Clifton, a neighborhood east of downtown Louisville, Kentucky USA. Clifton was named because of its hilly location on the Ohio River valley escarpment....

, adjacent to the campus where the Kentucky School for the Blind moved in 1855.

"Sold down the river"

Louisville had one of the largest slave trades in the United States before the Civil WarAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

, and much of the city's initial growth is attributed to that trade. Shifting agricultural needs produced an excess of slaves in Kentucky, and many were sold from here and other parts of the Upper South to the Deep South

Deep South

The Deep South is a descriptive category of the cultural and geographic subregions in the American South. Historically, it is differentiated from the "Upper South" as being the states which were most dependent on plantation type agriculture during the pre-Civil War period...

. In 1820, the slave population was at its height at nearly 26% of the Kentucky population, but by 1860, that proportion had dropped to 7.8%, even though this percentage still represented over 10,000 people. Through the 1850s, slave traders sold 2500-4000 slaves annually from Kentucky down river.

The expression "sold down the river" originated as a lament of eastern slaves being split apart from their families in sales to Louisville. Slave traders collected slaves there until they had enough to ship in a group via the Ohio and Mississippi rivers down to the slave market in New Orleans. There slaves were sold again to owners of cotton and sugar cane plantations.

Louisville was the turning point for many enslaved black

African American

African Americans are citizens or residents of the United States who have at least partial ancestry from any of the native populations of Sub-Saharan Africa and are the direct descendants of enslaved Africans within the boundaries of the present United States...

s. If they could get from there across the Ohio River, called the "River Jordan" by escaping slaves, they had a chance for freedom in Ohio and other northern states. They had to evade capture by bounty-seeking slave catchers, but many were aided by the Underground Railroad

Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was an informal network of secret routes and safe houses used by 19th-century black slaves in the United States to escape to free states and Canada with the aid of abolitionists and allies who were sympathetic to their cause. The term is also applied to the abolitionists,...

to get further north for freedom.

Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

, Louisville was a major stronghold of Union forces

Union Army

The Union Army was the land force that fought for the Union during the American Civil War. It was also known as the Federal Army, the U.S. Army, the Northern Army and the National Army...

, which kept Kentucky

Kentucky

The Commonwealth of Kentucky is a state located in the East Central United States of America. As classified by the United States Census Bureau, Kentucky is a Southern state, more specifically in the East South Central region. Kentucky is one of four U.S. states constituted as a commonwealth...

firmly in the Union. It was the center of planning, supplies, recruiting and transportation for numerous campaigns, especially in the Western Theater

Western Theater of the American Civil War

This article presents an overview of major military and naval operations in the Western Theater of the American Civil War.-Theater of operations:...

. While the state of Kentucky officially declared its neutrality

Neutral country

A neutral power in a particular war is a sovereign state which declares itself to be neutral towards the belligerents. A non-belligerent state does not need to be neutral. The rights and duties of a neutral power are defined in Sections 5 and 13 of the Hague Convention of 1907...

early in the war, prominent Louisville attorney James Speed

James Speed

James Speed was an American lawyer, politician and professor. In 1864, he was appointed by Abraham Lincoln to be the United States' Attorney General. He previously served in the Kentucky Legislature, and in local political office.Speed was born in Jefferson County, Kentucky, to Judge John Speed...

, brother of President

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. He successfully led his country through a great constitutional, military and moral crisis – the American Civil War – preserving the Union, while ending slavery, and...

's close friend Joshua Fry Speed

Joshua Fry Speed

Joshua Fry Speed was a close friend of Abraham Lincoln from his days in Springfield, Illinois, where Speed was a partner in a general store...

, strongly advocated keeping the state in the Union. Seeing Louisville's strategic importance in the freight industry, General William Tecumseh Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman was an American soldier, businessman, educator and author. He served as a General in the Union Army during the American Civil War , for which he received recognition for his outstanding command of military strategy as well as criticism for the harshness of the "scorched...

formed an army base

Military base

A military base is a facility directly owned and operated by or for the military or one of its branches that shelters military equipment and personnel, and facilitates training and operations. In general, a military base provides accommodations for one or more units, but it may also be used as a...

in the city in the event that the Confederacy

Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America was a government set up from 1861 to 1865 by 11 Southern slave states of the United States of America that had declared their secession from the U.S...

advanced.

In September 1862, Confederate

Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army was the army of the Confederate States of America while the Confederacy existed during the American Civil War. On February 8, 1861, delegates from the seven Deep South states which had already declared their secession from the United States of America adopted the...

General Braxton Bragg

Braxton Bragg

Braxton Bragg was a career United States Army officer, and then a general in the Confederate States Army—a principal commander in the Western Theater of the American Civil War and later the military adviser to Confederate President Jefferson Davis.Bragg, a native of North Carolina, was...

decided to take Louisville, but changed his mind. There was lack of backup from General Edmund Kirby Smith

Edmund Kirby Smith

Edmund Kirby Smith was a career United States Army officer and educator. He served as a general in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War, notable for his command of the Trans-Mississippi Department of the Confederacy after the fall of Vicksburg.After the conflict ended Smith...

's forces. In addition, the decision to install Confederate Governor Richard Hawes

Richard Hawes

Richard Hawes was a United States Representative from Kentucky and the second Confederate Governor of Kentucky. He was part of an influential political family, with a brother, uncle, and cousin who also served as U.S. Representatives. He began his political career as an ardent Whig and was a close...

in the alternative government in Frankfort

Frankfort, Kentucky

Frankfort is a city in Kentucky that serves as the state capital and the county seat of Franklin County. The population was 27,741 at the 2000 census; by population it is the 5th smallest state capital in the United States...

made people think the state might change. In the summer of 1863, Confederate cavalry under John Hunt Morgan

John Hunt Morgan

John Hunt Morgan was a Confederate general and cavalry officer in the American Civil War.Morgan is best known for Morgan's Raid when, in 1863, he and his men rode over 1,000 miles covering a region from Tennessee, up through Kentucky, into Indiana and on to southern Ohio...

invaded Kentucky from Tennessee

Tennessee

Tennessee is a U.S. state located in the Southeastern United States. It has a population of 6,346,105, making it the nation's 17th-largest state by population, and covers , making it the 36th-largest by total land area...

and briefly threatened Louisville, before swinging around the city into Indiana

Indiana

Indiana is a US state, admitted to the United States as the 19th on December 11, 1816. It is located in the Midwestern United States and Great Lakes Region. With 6,483,802 residents, the state is ranked 15th in population and 16th in population density. Indiana is ranked 38th in land area and is...

during Morgan's Raid

Morgan's Raid

Morgan's Raid was a highly publicized incursion by Confederate cavalry into the Northern states of Indiana and Ohio during the American Civil War. The raid took place from June 11–July 26, 1863, and is named for the commander of the Confederates, Brig. Gen...

. In March 1864, Generals Sherman and Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant was the 18th President of the United States as well as military commander during the Civil War and post-war Reconstruction periods. Under Grant's command, the Union Army defeated the Confederate military and ended the Confederate States of America...

met at the Galt House

Galt House

The Galt House is a 25-story, 1300-room hotel in Louisville, Kentucky. The original hotel was erected in 1837. The current Galt House is presently the city's only hotel on the Ohio River. Many noted people have stayed at the Galt House, including Jefferson Davis, Charles Dickens, Abraham Lincoln...

to plan the spring campaign, which included the capture of Atlanta, Georgia

Atlanta Campaign

The Atlanta Campaign was a series of battles fought in the Western Theater of the American Civil War throughout northwest Georgia and the area around Atlanta during the summer of 1864. Union Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman invaded Georgia from the vicinity of Chattanooga, Tennessee, beginning in May...

.

By the end of the war, Louisville itself had not been attacked once, although it was surrounded by skirmishes and battles, including the Battle of Perryville

Battle of Perryville

The Battle of Perryville, also known as the Battle of Chaplin Hills, was fought on October 8, 1862, in the Chaplin Hills west of Perryville, Kentucky, as the culmination of the Confederate Heartland Offensive during the American Civil War. Confederate Gen. Braxton Bragg's Army of Mississippi won a...

and the Battle of Corydon

Battle of Corydon

The Battle of Corydon was a minor engagement that took place July 9, 1863, just south of Corydon, which had been the original capital of Indiana until 1825, and was the county seat of Harrison County. The attack occurred during Morgan's Raid in the American Civil War as a force of 2,500 cavalry...

. The Unionists—most whose leaders owned slaves—felt betrayed by the abolitionist

Abolitionism

Abolitionism is a movement to end slavery.In western Europe and the Americas abolitionism was a movement to end the slave trade and set slaves free. At the behest of Dominican priest Bartolomé de las Casas who was shocked at the treatment of natives in the New World, Spain enacted the first...

position of the Republican Party

Republican Party (United States)

The Republican Party is one of the two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Democratic Party. Founded by anti-slavery expansion activists in 1854, it is often called the GOP . The party's platform generally reflects American conservatism in the U.S...

. After 1865 returning Confederate

Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army was the army of the Confederate States of America while the Confederacy existed during the American Civil War. On February 8, 1861, delegates from the seven Deep South states which had already declared their secession from the United States of America adopted the...

veterans largely took political control of the city, leading to the jibe that it joined the Confederacy after the war was over.

During the postwar years, Confederate women organized in associations to ensure the dead were buried in cemeteries, to identify missing men, and to build memorials to the war and their losses. By the 1890s, the memorial movement came under the control of the United Daughters of the Confederacy

United Daughters of the Confederacy

The United Daughters of the Confederacy is a women's heritage association dedicated to honoring the memory of those who served in the military and died in service to the Confederate States of America . UDC began as the National Association of the Daughters of the Confederacy, organized in 1894 by...

(UDC) and United Confederate Veterans

United Confederate Veterans

The United Confederate Veterans, also known as the UCV, was a veteran's organization for former Confederate soldiers of the American Civil War, and was equivalent to the Grand Army of the Republic which was the organization for Union veterans....

(UCV), who promoted the "Lost Cause". Making meaning after the war was another way of writing its history. In 1895, in one of their successes, a Confederate monument was erected near the University of Louisville

University of Louisville

The University of Louisville is a public university in Louisville, Kentucky. When founded in 1798, it was the first city-owned public university in the United States and one of the first universities chartered west of the Allegheny Mountains. The university is mandated by the Kentucky General...

campus.

Post-Reconstruction

Kentucky Derby

The Kentucky Derby is a Grade I stakes race for three-year-old Thoroughbred horses, held annually in Louisville, Kentucky, United States on the first Saturday in May, capping the two-week-long Kentucky Derby Festival. The race is one and a quarter mile at Churchill Downs. Colts and geldings carry...

was held on May 17, 1875, at the Louisville Jockey Club track (later renamed to Churchill Downs

Churchill Downs

Churchill Downs, located in Central Avenue in south Louisville, Kentucky, United States, is a Thoroughbred racetrack most famous for hosting the Kentucky Derby annually. It officially opened in 1875, and held the first Kentucky Derby and the first Kentucky Oaks in the same year. Churchill Downs...

). The Derby was originally shepherded by Meriwether Lewis Clark, Jr., the grandson of William Clark of the Lewis and Clark Expedition

Lewis and Clark Expedition

The Lewis and Clark Expedition, or ″Corps of Discovery Expedition" was the first transcontinental expedition to the Pacific Coast by the United States. Commissioned by President Thomas Jefferson and led by two Virginia-born veterans of Indian wars in the Ohio Valley, Meriwether Lewis and William...

. Ten thousand spectators were present at the first Derby to watch Aristides win the race.

Professional baseball

Baseball is a team sport which is played by several professional leagues throughout the world. In these leagues, and associated farm teams, players are selected for their talents and are paid to play for a specific team or club system....

launched the National League

National League

The National League of Professional Baseball Clubs, known simply as the National League , is the older of two leagues constituting Major League Baseball, and the world's oldest extant professional team sports league. Founded on February 2, 1876, to replace the National Association of Professional...

, and the Louisville Grays

Louisville Grays

The Louisville Grays were a 19th century U.S. baseball team and charter member of the National League, based in Louisville, Kentucky. They played two seasons, 1876 and 1877, and compiled a record of 65–61. Their home games were at the Louisville Baseball Park. The Grays were owned by...

were a charter member. While the Grays were a relatively short-lived team, playing for only two years, they began a much longer lasting relationship between the city and baseball. In 1883, John "Bud" Hillerich made his first baseball bat

Baseball bat

A baseball bat is a smooth wooden or metal club used in the game of baseball to hit the ball after the ball is thrown by the pitcher. It is no more than 2.75 inches in diameter at the thickest part and no more than 42 inches in length. It typically weighs no more than 33 ounces , but it...

from white ash

White Ash

For another species referred to as white ash, see Eucalyptus fraxinoides.Fraxinus americana is a species of Fraxinus native to eastern North America found in mesophytic hardwood forests from Nova Scotia west to Minnesota, south to northern Florida, and southwest to eastern...

in his father's wood shop. The first bat was produced for Pete "The Gladiator" Browning

Pete Browning

Louis Rogers "Pete" Browning was an American center and left fielder in Major League Baseball from 1882 to 1894 who played primarily for the Louisville Eclipse/Colonels, becoming one of the sport's most accomplished batters of the 1880s...

of the Louisville Eclipse (minor league team). The bats eventually become known by the popular name, Louisville Slugger, and the local company Hillerich & Bradsby

Hillerich & Bradsby

Hillerich & Bradsby Company is a company located in Louisville, Kentucky that produces the famous Louisville Slugger baseball bat. The Louisville Slugger Museum & Factory in downtown Louisville features a retrospective of the product and its use throughout baseball history...

rapidly became one of the largest manufacturers of baseball bats and other sporting equipment in the world. Today, Hillerich & Bradsby manufactures over one million wooden bats per year, accounting for about two of three wooden bats sold worldwide.

In 1877 the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary

Southern Baptist Theological Seminary

The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary , located in Louisville, Kentucky, is the oldest of the six seminaries affiliated with the Southern Baptist Convention . The seminary was founded in 1859, at Greenville, South Carolina. After being closed during the Civil War, it moved in 1877 to Louisville...

relocated to Louisville from Greenville, South Carolina

Greenville, South Carolina

-Law and government:The city of Greenville adopted the Council-Manager form of municipal government in 1976.-History:The area was part of the Cherokee Nation's protected grounds after the Treaty of 1763, which ended the French and Indian War. No White man was allowed to enter, though some families...

, where it had been founded in 1859. Its new campus, at Fourth and Broadway downtown, was underwritten by a group of Louisville business leaders, including the Norton family, eager to add the promising graduate-professional school to the city's resources. It grew quickly, attracting students from all parts of the nation, and by the early 20th century it was the second largest accredited seminary in the United States. It relocated to its present 100 acre (0.404686 km²) campus on Lexington Road in 1926.

On August 1, 1883, U.S. President

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

Chester A. Arthur

Chester A. Arthur

Chester Alan Arthur was the 21st President of the United States . Becoming President after the assassination of President James A. Garfield, Arthur struggled to overcome suspicions of his beginnings as a politician from the New York City Republican machine, succeeding at that task by embracing...

opened the first annual Southern Exposition

Southern Exposition

The Southern Exposition was a five-year series of World's Fairs held in the city of Louisville, Kentucky from 1883 to 1887 in what is now Louisville's Old Louisville neighborhood. The exposition, held for 100 days each year on immediately south of Central Park, which is now the St....

, a series of World's Fair

World's Fair

World's fair, World fair, Universal Exposition, and World Expo are various large public exhibitions held in different parts of the world. The first Expo was held in The Crystal Palace in Hyde Park, London, United Kingdom, in 1851, under the title "Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All...

s that would run for five consecutive years adjacent to Central Park

Central Park, Louisville

Central Park is a municipal park maintained by the city of Louisville, Kentucky. Located in the Old Louisville neighborhood, it was first developed for public use in the 1870s and referred to as "DuPont Square" since it was at that time part of the Du Pont family estate.During the Southern...

in what is now Old Louisville

Old Louisville

Old Louisville is a historic district and neighborhood in central Louisville, Kentucky, USA. It is the third largest such district in the United States, and the largest preservation district featuring almost entirely Victorian architecture...

. Highlighted at the show was the largest to-date installation of incandescent light bulb

Incandescent light bulb

The incandescent light bulb, incandescent lamp or incandescent light globe makes light by heating a metal filament wire to a high temperature until it glows. The hot filament is protected from air by a glass bulb that is filled with inert gas or evacuated. In a halogen lamp, a chemical process...

s, having been recently invented by Thomas Edison

Thomas Edison

Thomas Alva Edison was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices that greatly influenced life around the world, including the phonograph, the motion picture camera, and a long-lasting, practical electric light bulb. In addition, he created the world’s first industrial...

, a former resident.

Landscape architect

A landscape architect is a person involved in the planning, design and sometimes direction of a landscape, garden, or distinct space. The professional practice is known as landscape architecture....

Frederick Law Olmsted

Frederick Law Olmsted

Frederick Law Olmsted was an American journalist, social critic, public administrator, and landscape designer. He is popularly considered to be the father of American landscape architecture, although many scholars have bestowed that title upon Andrew Jackson Downing...

was commissioned to design Louisville's system of parks (most notably, Cherokee

Cherokee Park

Cherokee Park is a municipal park located in Louisville, Kentucky, United States. It was designed, like 18 of Louisville's 123 public parks, by Frederick Law Olmsted, the father of landscape architecture...

, Iroquois

Iroquois Park

Iroquois Park is a 739 acre municipal park in Louisville, Kentucky, United States. It was designed by Frederick Law Olmsted, who also designed Louisville's Cherokee Park and Shawnee Park, at what were then the edges of the city. Located south of downtown, Iroquois Park was promoted as...

and Shawnee

Shawnee Park

Shawnee Park is a municipal park in Louisville, Kentucky. It was designed by Frederick Law Olmsted, who designed 18 of the city's 123 public parks...

Parks) connected by tree-lined parkways. Passenger train service arrived in the city on September 7, 1891 with the completion of the Union Station

Union Station (Louisville)

The Union Station of Louisville, Kentucky is a historic railroad station that serves as offices for the Transit Authority of River City, as it has since mid-April 1980 after receiving a year-long restoration costing approximately $2 million. It was one of three union stations in Kentucky, the other...

train hub. The first train arrived at 7:30 am. Louisville's Union Station was then recognized as the largest train station

Train station