Andrew Cunningham, 1st Viscount Cunningham of Hyndhope

Encyclopedia

Admiral of the Fleet

Andrew Browne Cunningham, 1st Viscount Cunningham of Hyndhope KT

, GCB

, OM

, DSO

and two Bars

(7 January 1883 – 12 June 1963), was a British

admiral

of the Second World War

. Cunningham was widely known by his nickname, "ABC".

Cunningham was born in Rathmines

in the southside of Dublin on 7 January 1883. After starting his schooling in Dublin and Edinburgh, he enrolled at a naval academy, at the age of ten, beginning his association with the Royal Navy

. After passing out of Britannia Royal Naval College, Dartmouth

, in 1898, he progressed rapidly in rank. He commanded a destroyer during the First World War

and through most of the interwar period. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Order

and two Bar

s, for his performance during this time, specifically for his actions in the Dardanelles

and in the Baltics

.

In the Second World War, as Commander-in-Chief

, Mediterranean Fleet, Cunningham led British naval forces to victory in several critical Mediterranean naval battles

. These included the attack on Taranto

in 1940, the first completely all-aircraft naval attack in history, and the Battle of Cape Matapan

in 1941. Cunningham controlled the defence of the Mediterranean supply lines

through Alexandria, Gibraltar, and the key chokepoint of Malta

. The admiral also directed naval support for the various major allied landings in the Western Mediterranean littoral. In 1943, Cunningham was promoted to First Sea Lord

, a position he held until his retirement in 1946. He was ennobled as Baron Cunningham of Hyndhope in 1945 and made Viscount Cunningham of Hyndhope the following year. After his retirement Cunningham enjoyed several ceremonial positions including Lord High Steward

at the coronation

of Queen Elizabeth II

in 1953. He died on 12 June 1963.

, County Dublin

, on 7 January 1883, the third of five children born to Professor Daniel Cunningham and his wife Elizabeth Cumming Browne, both of Scottish ancestry. General Sir Alan Cunningham was his younger brother. His parents were described as having a "strong intellectual and clerical tradition," both grandfathers having been in the clergy. His father was a Professor of Anatomy

at Trinity College, Dublin

, whilst his mother stayed at home. Elizabeth Browne, with the aid of servants and governess

es, oversaw much of his upbringing; as a result he reportedly had a "warm and close" relationship with her. After a short introduction to schooling in Dublin he was sent to Edinburgh Academy

, where he stayed with his aunts Doodles and Connie May. At the age of ten he received a telegram from his father asking "would you like to go into the Navy?" At the time, the family had no maritime connections, and Cunningham only had a vague interest in the sea. Nevertheless he replied "Yes, I should like to be an Admiral". He was then sent to a Naval Preparatory School, Stubbington House, which specialised in sending pupils through the Dartmouth

entrance examinations. Cunningham passed the exams showing particular strength in mathematics.

Along with 64 other men Cunningham joined the Royal Navy

Along with 64 other men Cunningham joined the Royal Navy

as a cadet aboard the training ship HMS Britannia

in 1897. One of his classmates was future Admiral of the Fleet James Fownes Somerville. Cunningham was known for his lack of enthusiasm for field sports, although he did enjoy golf and spent most of his spare time "messing around in boats". He said in his memoirs that by the end of his course he was "anxious to seek adventure at sea". Although he committed numerous minor misdemeanors, he still obtained a very good for conduct. He passed out tenth in April, 1898, with first-class-marks for mathematics and seamanship

.

His first service was as a Midshipman

on HMS Doris

in 1899, serving at the Cape of Good Hope Station

when the Second Boer War

began. By February, 1900, he had transferred into the Naval Brigade

as he believed "this promised opportunities for bravery and distinction in action." Cunningham then saw action at Pretoria and Diamond Hill

as part of the Naval Brigade. He then went back to sea, as Midshipman in HMS Hannibal

in December, 1901. The following November he joined the protected cruiser

HMS Diadem

. Beginning in 1902, Cunningham took Sub-Lieutenant

courses at Portsmouth

and Greenwich; he served as Sub-Lieutenant on the battleship

HMS Implacable

, in the Mediterranean, for six months in 1903. In September 1903, he was transferred to HMS Locust

to serve as second-in-command. He was promoted to Lieutenant

in 1904, and served on several vessels during the next four years. In 1908, he was awarded his first command, HM Torpedo Boat No. 14

.

Cunningham was a highly decorated officer during the First World War, receiving the Distinguished Service Order (DSO)

Cunningham was a highly decorated officer during the First World War, receiving the Distinguished Service Order (DSO)

and two bars

. In 1911 he was given command of the destroyer

HMS Scorpion

, which he commanded throughout the war. In 1914, Scorpion was involved in the shadowing of the German

battlecruiser

and cruiser

SMS Goeben and SMS Breslau

. This operation was intended to find and destroy the Goeben and the Breslau but the German warships evaded the British fleet, and passed through the Dardanelles

to reach Constantinople

. Their arrival contributed to the Ottoman Empire

joining the Central Powers

in November 1914. Though a bloodless "battle", the failure of the British pursuit had enormous political and military ramifications—in the words of Winston Churchill

, they brought "more slaughter, more misery and more ruin than has ever before been borne within the compass of a ship."

Cunningham stayed on in the Mediterranean and in 1915 Scorpion was involved in the attack on the Dardanelles

. For his performance Cunningham was rewarded with promotion to Commander

and the award of the Distinguished Service Order. Cunningham spent much of 1916 on routine patrols. In late 1916, he was engaged in convoy protection, a duty he regarded as mundane. He had no contact with German U-boats during this time, on which he commented; "The immunity of my convoys was probably due to sheer luck". Convinced that the Mediterranean held few offensive possibilities he requested to sail for home. Scorpion paid off on 21 January 1918. In his seven years as captain of the Scorpion, Cunningham had developed a reputation for first class seamanship. He was transferred by Vice-Admiral Roger Keyes to HMS Termagent, part of Keyes' Dover Patrol

, in April 1918. and for his actions with the Dover Patrol, he was awarded a bar

to his DSO the following year.

HMS Seafire, on duty in the Baltic

. The Communists, the White Russian

s, several varieties of Latvian nationalists, Germans, and the Poles

were trying to control Latvia

; the British Government had recognised Latvia's independence after the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

. It was on this voyage that Cunningham first met Admiral

Walter Cowan

. Cunningham was impressed by Cowan's methods, specifically his navigation of the potentially dangerous seas, with thick fog and minefields

threatening the fleet. Throughout several potentially problematic encounters with German forces trying to undermine the Latvian independence movement, Cunningham exhibited "good self control and judgement". Cowan was quoted as saying "Commander Cunningham has on one occasion after another acted with unfailing promptitude and decision, and has proved himself an Officer of exceptional valour and unerring resolution."

For his actions in the Baltic

, Cunningham was awarded a second bar to his DSO, and promoted to Captain

in 1920. On his return from the Baltic in 1922, he was appointed Captain of the British 6th Destroyer Flotilla. Further commands were to follow; the British 1st Destroyer Flotilla in 1923, and the destroyer base, HMS Lochinvar, at Port Edgar

in the Firth of Forth

, from 1927–1926. Cunningham renewed his association with Vice Admiral Cowan between 1926 and 1928, when Cunningham was Flag Captain and Chief Staff Officer

to Cowan while serving on the North America and West Indies Squadron. In his memoirs Cunningham made clear the "high regard" in which he held Cowan, and the many lessons he learned from him during their two periods of service together. The late 1920s found Cunningham back in the UK participating in courses at the Army's Senior Officers' School

at Sheerness

, as well as at the Imperial Defence College

. While Cunningham was at the Imperial Defence College, in 1929, he married Nona Byatt (daughter of Horace Byatt, MA; the couple had no children). After a year at the College, Cunningham was given command of his first big ship; the battleship HMS Rodney. Eighteen months later, he was appointed Commodore

of HMS Pembroke

, the Royal Naval barracks at Chatham

.

In September 1932, Cunningham was promoted to flag rank, and Aide-de-Camp

In September 1932, Cunningham was promoted to flag rank, and Aide-de-Camp

to the King

. He was appointed Rear Admiral

(Destroyers) in the Mediterranean in December 1933 and was made a Companion of the Bath

in 1934. Having hoisted his flag in the light cruiser

HMS Coventry, Cunningham used his time to practice fleet

handling for which he was to receive much praise in the Second World War. There were also fleet exercises in the Atlantic Ocean

in which he learnt the skills and values of night actions that he would also use to great effect in years to come.

On his promotion to Vice Admiral

in July 1936, due to the interwar naval policy

, further active employment seemed remote. However, a year later due to the illness of Sir Geoffrey Blake

, Cunningham assumed the combined appointment of commander of the British Battlecruiser Squadron

and second-in-command of the Mediterranean Fleet, with HMS Hood

as his flagship

. After his long service in small ships, Cunningham considered his accommodation aboard Hood to be almost palatial, even surpassing his previous big ship experience on Rodney.

He retained command until September 1938, when he was appointed to the Admiralty

as Deputy Chief of the Naval Staff, although he did not actually take up this post until December 1939. He accepted this shore job with reluctance since he loathed administration, but the Board of Admiralty’s high regard of him was evident. For six months during an illness of Admiral Sir Roger Backhouse

, the then First Sea Lord

, he deputised for Backhouse on the Committee of Imperial Defence

and on the Admiralty Board. In 1939 he was made a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath

(KCB), becoming known as Sir Andrew Cunningham.

on the 5 June 1939. As Commander-in-Chief, Cunningham's main concern was for the safety of convoys heading for Egypt

and Malta

. These convoys were highly significant in that they were desperately needed to keep Malta, a small British colony

and naval base, in the war. Malta was a strategic strongpoint and Cunningham fully appreciated this. Cunningham believed that the main threat to British Sea Power in the Mediterranean would come from the Italian Fleet

. As such Cunningham had his fleet at a heightened state of readiness, so that when Italy did choose to enter into hostilities, then the British Fleet would be ready.

for the demilitarisation and internment of a French squadron at Alexandria

, in June 1940, following the Fall of France

. Churchill had ordered Cunningham to prevent the French warships from leaving port, and to ensure that French warships did not pass into enemy hands. Stationed at the time at Alexandria

, Cunningham entered into delicate negotiations with Godfroy to ensure his fleet, which consisted of the battleship Lorraine

, 4 cruisers, 3 destroyers and a submarine, posed no threat. The Admiralty ordered Cunningham to complete the negotiations on 3 July. Just as an agreement seemed imminent Godfroy heard of the British action against the French at Mers el Kebir and, for a while, Cunningham feared a battle between French and British warships in the confines of Alexandria harbour

. The deadline was overrun but negotiations ended well, after Cunningham put them on a more personal level and had the British ships appeal to their French opposite numbers. Cunningham's negotiations succeeded and the French emptied their fuel bunkers and removed the firing mechanisms from their guns. Cunningham in turn promised to repatriate the ships' crews.

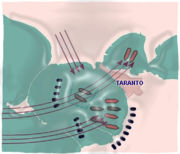

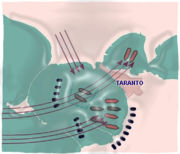

Although the threat from the French Fleet had been neutralised, Cunningham was still aware of the threat posed by the Italian Fleet to British North African operations

Although the threat from the French Fleet had been neutralised, Cunningham was still aware of the threat posed by the Italian Fleet to British North African operations

, based in Egypt

. Although the Royal Navy had won in several actions in the Mediterranean, considerably upsetting the balance of power

, the Italians who were following the theory of a fleet in being

had left their ships in harbour. This made the threat of a sortie

against the British Fleet a serious problem. At the time the harbour at Taranto contained six battleship

s (five of them battle-worthy), seven heavy cruiser

s, two light cruiser

s, and eight destroyer

s. The Admiralty, concerned with the potential for an attack, had drawn up Operation Judgement; a surprise attack on Taranto Harbour. To carry out the attack, the Admiralty sent the new aircraft carrier HMS Illustrious, commanded by Lumley Lyster

, to join HMS Eagle

in Cunningham's fleet.

The attack started at 21:00, 11 November 1940, when the first of two waves of Fairey Swordfish

torpedo bombers took off from Illustrious, followed by the second wave an hour later. The attack was a great success: the Italian fleet lost half its strength in one night. The "fleet-in-being" diminished in importance and the threat to the Royal Navy's control of the Mediterranean had been considerably reduced. Cunningham said of the victory: "Taranto, and the night of November 11–12, 1940, should be remembered for ever as having shown once and for all that in the Fleet Air Arm

the Navy has its most devastating weapon." The Royal Navy had launched the first all-aircraft naval attack in history, flying a small number of aircraft from an aircraft carrier. This, and other aspects of the raid, were important facts in the planning of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941

: the Japanese planning staff were thought to have studied it intensively.

Cunningham's official reaction at the time was memorably terse. After landing the last of the attacking aircraft, Illustrious signalled "Operation Judgement executed". After seeing aerial reconnaissance photographs the next day which showed several Italian ships sunk or out of action, Cunningham replied with the two-letter code group which signified, "Manoeuvre well executed".

At the end of March 1941, Hitler wanted the convoys supplying the British Expeditionary force in Greece

At the end of March 1941, Hitler wanted the convoys supplying the British Expeditionary force in Greece

stopped, and the Italian Navy was the only force able to attempt this. Cunningham stated in his biography: "I myself was inclined to think that the Italians would not try anything. I bet Commander Power, the Staff Officer, Operations, the sum of ten shilling

s that we would see nothing of the enemy." Under pressure from Germany, the Italian Fleet planned to launch an attack on the British Fleet on 28 March 1941.

The Italian commander, Admiral Angelo Iachino

, intended to carry out a surprise attack on the British Cruiser Squadron in the area (commanded by Vice-Admiral Sir Henry Pridham-Wippell), executing a pincer movement

with the battleship Vittorio Veneto

. Cunningham though, was aware of Italian naval activity through intercepts of Italian Enigma

messages. Although Italian intentions were unclear, Cunningham's staff believed an attack upon British troop convoys was likely and orders were issued to spoil the enemy plan and, if possible, intercept their fleet. Cunningham wished, however, to disguise his own activity and arranged for a game of golf and a fictitious evening gathering to mislead enemy agents (he was, in fact, overheard by the local Japanese Consul). After sunset, he boarded HMS Warspite and left Alexandria.

Cunningham, realising that an air attack could weaken the Italians, ordered an attack by the Formidables Albacore

torpedo-bombers. A hit on the Vittorio Veneto slowed her temporarily and Iachino, realising his fleet was vulnerable without air cover, ordered his forces to retire. Cunningham gave the order to pursue the Italian Fleet.

An air attack from the Formidable had disabled the cruiser Pola

and Iachino, unaware of Cunningham's pursuing battlefleet, ordered a squadron of cruisers and destroyers to return and protect the Pola. Cunningham, meanwhile, was joining up with Pridham-Wippell's cruiser squadron. Throughout the day several chases and sorties occurred with no overall victor. None of the Italian ships were equipped for night fighting, and when night fell, they made to return to Taranto. The British battlefleet equipped with radar

detected the Italians shortly after 22:00. In a pivotal moment in naval warfare during the Second World War, the battleships Barham

, Valiant

and Warspite opened fire on two Italian cruisers at only 3,800 yards (3.5 km), destroying them in only five minutes.

Although the Vittorio Veneto escaped from the battle by returning to Taranto, there were many accolades given to Cunningham for continuing the pursuit at night, against the advice of his staff. After the previous defeat at Taranto, the defeat at Cape Matapan dealt another strategic blow to the Italian Navy. Five ships - three heavy cruisers and two destroyers - were sunk, and around 2,400 Italian sailors were killed, missing or captured. The British lost only three aircrew when one torpedo bomber was shot down. Cunningham had lost his bet with Commander Power but he had won a strategic victory in the war in the Mediterranean. The defeats at Taranto and Cape Matapan meant that the Italian Navy did not intervene in the heavily contested evacuations of Greece and Crete, later in 1941. It also ensured that, for the remainder of the war, the Regia Marina

conceded the Eastern Mediterranean to the Allied Fleet, and did not leave port for the remainder of the war.

On the morning of 20 May 1941, Nazi Germany

On the morning of 20 May 1941, Nazi Germany

launched an airborne invasion

of Crete, under the code-name Unternehmen Merkur (Operation Mercury). Despite initial heavy casualties, Maleme

airfield in western Crete fell to the Germans and enabled the Germans to fly in heavy reinforcements and overwhelm the Allied forces.

After a week of heavy fighting, British commanders decided that the situation was hopeless and ordered a withdrawal from Sfakia

. During the next four nights, 16,000 troops were evacuated to Egypt by ships (including HMS Ajax

of Battle of the River Plate

fame). A smaller number of ships were to withdraw troops on a separate mission from Heraklion

, but these ships were attacked en route by Luftwaffe

dive bomber

s. Without air cover, Cunningham's ships suffered serious losses. Cunningham was determined, though, that the "navy must not let the army down", and when army generals feared he would lose too many ships, Cunningham famously said,

The "never say die" attitude of Cunningham and the men under his command meant that of 22,000 men on Crete, 16,500 were rescued but at the loss of three cruisers and six destroyers. Fifteen other major warships were damaged.

Cunningham became a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath (GCB), "in recognition of the recent successful combined operations in the Middle East", in March 1941 and was created a Baronet, of Bishop's Waltham in the County of Southampton, in July 1942. From late 1942 to early 1943, he served under General Eisenhower

Cunningham became a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath (GCB), "in recognition of the recent successful combined operations in the Middle East", in March 1941 and was created a Baronet, of Bishop's Waltham in the County of Southampton, in July 1942. From late 1942 to early 1943, he served under General Eisenhower

, who made him the Supreme Commander, Allied Expeditionary Force. In this role that Cunningham commanded the large fleet that covered the Anglo-American landings in North Africa (Operation Torch

). General Eisenhower said of him in his diary:

On 21 January 1943, Cunningham was promoted to Admiral of the Fleet. February 1943 saw him return to his post as Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean Fleet. Three months later, when Axis forces in North Africa were on the verge of surrender, he ordered that none should be allowed to escape. Entirely in keeping with his fiery character he signalled the fleet "Sink, burn and destroy: Let nothing pass". He oversaw the naval forces used in the joint Anglo-American amphibious invasions of Sicily, during Operation Husky, Operation Baytown

and Operation Avalanche. On the morning of 11 September 1943, Cunningham was present at Malta when the Italian Fleet surrendered. Cunningham informed the Admiralty with a telegram; "Please to inform your Lordships that the Italian battle fleet now lies at anchor under the guns of the fortress of Malta."

In October 1943, Cunningham became First Sea Lord

of the Admiralty and Chief of the Naval Staff, after the death of Dudley Pound

. This promotion meant that he had to relinquish his coveted post of Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean, recommending his namesake Admiral John H. D. Cunningham as his successor. In the position of First Sea Lord, and as a member of the Chiefs of Staff committee, Cunningham was responsible for the overall strategic direction of the navy for the remainder of the war. He attended the major conferences at Cairo

, Tehran

, Yalta

and Potsdam

, at which the Allies discussed future strategy, including the invasion of Normandy and the deployment of a British fleet

to the Pacific Ocean

.

and raised to the peerage as Baron Cunningham of Hyndhope, of Kirkhope in the County of Selkirk. He was entitled to retire at the end of the war in 1945 but he resolved to pilot the Navy through the transition to peace before retiring. With the election of Clement Attlee

as British Prime Minister

in 1945, and the implementation of his Post-war consensus

, there was a large reduction in the Defence Budget. The extensive reorganisation was a challenge for Cunningham. "We very soon came to realise how much easier it was to make war than to reorganise for peace." Due to pressures on the budget from all three services, the Navy embarked on a reduction programme that was larger than Cunningham had envisaged.

He was made Viscount Cunningham of Hyndhope, of Kirkhope in the County of Selkirk, in January 1946, and appointed to the Order of Merit

in June of that year. At the end of May 1946, after overseeing the transition through to peacetime, Cunningham retired from his post as First Sea Lord. Cunningham retreated to the "little house in the country", 'Palace House', at Bishop's Waltham

in Hampshire, which he and Lady Cunningham had acquired before the war. They both had a busy retirement. He attended the House of Lords irregularly and occasionally lent his name to press statements about the Royal Navy, particularly those relating to Admiral Dudley North

, who had been relieved of his command of Gibraltar

in 1940. Cunningham, and several of the surviving Admirals of the Fleet, set about securing justice for North, and they succeeded with a partial vindication in 1957. He also busied himself with various appointments; he was Lord High Commissioner to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland

in 1950 and 1952, and in 1953 he acted as Lord High Steward

- the most recent one to date - at the coronation

of Queen Elizabeth II

. Throughout this time Cunningham and his wife entertained family and friends, including his own great nephew, Jock Slater, in their extensive gardens. Cunningham died in London on 12 June 1963, and was buried at sea off Portsmouth. There were no children from his marriage and his titles consequently became extinct on his death.

A bust of Cunningham by Franta Belsky

was unveiled in Trafalgar Square

in London

on 2 April 1967 by Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh

. The April 2010 UK naval operation to ship British military personnel and air passengers stranded in continental Europe by the air travel disruption after the 2010 Eyjafjallajökull eruption

back to the UK was named Operation Cunningham

after him.

Below is a list of Awards and titles awarded to Andrew Browne Cunningham during his lifetime.

Below is a list of Awards and titles awarded to Andrew Browne Cunningham during his lifetime.

|-

|-

|-

|-

|-

|-

Admiral of the Fleet (Royal Navy)

Admiral of the fleet is the highest rank of the British Royal Navy and other navies, which equates to the NATO rank code OF-10. The rank still exists in the Royal Navy but routine appointments ceased in 1996....

Andrew Browne Cunningham, 1st Viscount Cunningham of Hyndhope KT

Order of the Thistle

The Most Ancient and Most Noble Order of the Thistle is an order of chivalry associated with Scotland. The current version of the Order was founded in 1687 by King James VII of Scotland who asserted that he was reviving an earlier Order...

, GCB

Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate mediæval ceremony for creating a knight, which involved bathing as one of its elements. The knights so created were known as Knights of the Bath...

, OM

Order of Merit

The Order of Merit is a British dynastic order recognising distinguished service in the armed forces, science, art, literature, or for the promotion of culture...

, DSO

Distinguished Service Order

The Distinguished Service Order is a military decoration of the United Kingdom, and formerly of other parts of the British Commonwealth and Empire, awarded for meritorious or distinguished service by officers of the armed forces during wartime, typically in actual combat.Instituted on 6 September...

and two Bars

Medal bar

A medal bar or medal clasp is a thin metal bar attached to the ribbon of a military decoration, civil decoration, or other medal. It is most commonly used to indicate the campaign or operation the recipient received the award for, and multiple bars on the same medal are used to indicate that the...

(7 January 1883 – 12 June 1963), was a British

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

admiral

Admiral

Admiral is the rank, or part of the name of the ranks, of the highest naval officers. It is usually considered a full admiral and above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet . It is usually abbreviated to "Adm" or "ADM"...

of the Second World War

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

. Cunningham was widely known by his nickname, "ABC".

Cunningham was born in Rathmines

Rathmines

Rathmines is a suburb on the southside of Dublin, about 3 kilometres south of the city centre. It effectively begins at the south side of the Grand Canal and stretches along the Rathmines Road as far as Rathgar to the south, Ranelagh to the east and Harold's Cross to the west.Rathmines has...

in the southside of Dublin on 7 January 1883. After starting his schooling in Dublin and Edinburgh, he enrolled at a naval academy, at the age of ten, beginning his association with the Royal Navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

. After passing out of Britannia Royal Naval College, Dartmouth

Britannia Royal Naval College

Britannia Royal Naval College is the initial officer training establishment of the Royal Navy, located on a hill overlooking Dartmouth, Devon, England. While Royal Naval officer training has taken place in the town since 1863, the buildings which are seen today were only finished in 1905, and...

, in 1898, he progressed rapidly in rank. He commanded a destroyer during the First World War

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

and through most of the interwar period. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Order

Distinguished Service Order

The Distinguished Service Order is a military decoration of the United Kingdom, and formerly of other parts of the British Commonwealth and Empire, awarded for meritorious or distinguished service by officers of the armed forces during wartime, typically in actual combat.Instituted on 6 September...

and two Bar

Medal bar

A medal bar or medal clasp is a thin metal bar attached to the ribbon of a military decoration, civil decoration, or other medal. It is most commonly used to indicate the campaign or operation the recipient received the award for, and multiple bars on the same medal are used to indicate that the...

s, for his performance during this time, specifically for his actions in the Dardanelles

Naval operations in the Dardanelles Campaign

The naval operations in the Dardanelles Campaign of the First World War were mainly carried out by the Royal Navy with substantial support from the French and minor contributions from Russia and Australia. The Dardanelles Campaign began as a purely naval operation...

and in the Baltics

Baltic states

The term Baltic states refers to the Baltic territories which gained independence from the Russian Empire in the wake of World War I: primarily the contiguous trio of Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania ; Finland also fell within the scope of the term after initially gaining independence in the 1920s.The...

.

In the Second World War, as Commander-in-Chief

Commander-in-Chief

A commander-in-chief is the commander of a nation's military forces or significant element of those forces. In the latter case, the force element may be defined as those forces within a particular region or those forces which are associated by function. As a practical term it refers to the military...

, Mediterranean Fleet, Cunningham led British naval forces to victory in several critical Mediterranean naval battles

Battle of the Mediterranean

The Battle of the Mediterranean was the name given to the naval campaign fought in the Mediterranean Sea during World War II, from 10 June 1940-2 May 1945....

. These included the attack on Taranto

Battle of Taranto

The naval Battle of Taranto took place on the night of 11–12 November 1940 during the Second World War. The Royal Navy launched the first all-aircraft ship-to-ship naval attack in history, flying a small number of obsolescent biplane torpedo bombers from an aircraft carrier in the Mediterranean Sea...

in 1940, the first completely all-aircraft naval attack in history, and the Battle of Cape Matapan

Battle of Cape Matapan

The Battle of Cape Matapan was a Second World War naval battle fought from 27–29 March 1941. The cape is on the southwest coast of Greece's Peloponnesian peninsula...

in 1941. Cunningham controlled the defence of the Mediterranean supply lines

Malta Convoys

The Malta Convoys were a series of Allied supply convoys that sustained the besieged island of Malta during the Mediterranean Theatre of the Second World War...

through Alexandria, Gibraltar, and the key chokepoint of Malta

Malta Convoys

The Malta Convoys were a series of Allied supply convoys that sustained the besieged island of Malta during the Mediterranean Theatre of the Second World War...

. The admiral also directed naval support for the various major allied landings in the Western Mediterranean littoral. In 1943, Cunningham was promoted to First Sea Lord

First Sea Lord

The First Sea Lord is the professional head of the Royal Navy and the whole Naval Service; it was formerly known as First Naval Lord. He also holds the title of Chief of Naval Staff, and is known by the abbreviations 1SL/CNS...

, a position he held until his retirement in 1946. He was ennobled as Baron Cunningham of Hyndhope in 1945 and made Viscount Cunningham of Hyndhope the following year. After his retirement Cunningham enjoyed several ceremonial positions including Lord High Steward

Lord High Steward

The position of Lord High Steward of England is the first of the Great Officers of State. The office has generally remained vacant since 1421, except at coronations and during the trials of peers in the House of Lords, when the Lord High Steward presides. In general, but not invariably, the Lord...

at the coronation

Coronation of the British monarch

The coronation of the British monarch is a ceremony in which the monarch of the United Kingdom is formally crowned and invested with regalia...

of Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom

Elizabeth II is the constitutional monarch of 16 sovereign states known as the Commonwealth realms: the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Jamaica, Barbados, the Bahamas, Grenada, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, Tuvalu, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Belize,...

in 1953. He died on 12 June 1963.

Childhood

Cunningham was born at RathminesRathmines

Rathmines is a suburb on the southside of Dublin, about 3 kilometres south of the city centre. It effectively begins at the south side of the Grand Canal and stretches along the Rathmines Road as far as Rathgar to the south, Ranelagh to the east and Harold's Cross to the west.Rathmines has...

, County Dublin

County Dublin

County Dublin is a county in Ireland. It is part of the Dublin Region and is also located in the province of Leinster. It is named after the city of Dublin which is the capital of Ireland. County Dublin was one of the first of the parts of Ireland to be shired by King John of England following the...

, on 7 January 1883, the third of five children born to Professor Daniel Cunningham and his wife Elizabeth Cumming Browne, both of Scottish ancestry. General Sir Alan Cunningham was his younger brother. His parents were described as having a "strong intellectual and clerical tradition," both grandfathers having been in the clergy. His father was a Professor of Anatomy

Anatomy

Anatomy is a branch of biology and medicine that is the consideration of the structure of living things. It is a general term that includes human anatomy, animal anatomy , and plant anatomy...

at Trinity College, Dublin

Trinity College, Dublin

Trinity College, Dublin , formally known as the College of the Holy and Undivided Trinity of Queen Elizabeth near Dublin, was founded in 1592 by letters patent from Queen Elizabeth I as the "mother of a university", Extracts from Letters Patent of Elizabeth I, 1592: "...we...found and...

, whilst his mother stayed at home. Elizabeth Browne, with the aid of servants and governess

Governess

A governess is a girl or woman employed to teach and train children in a private household. In contrast to a nanny or a babysitter, she concentrates on teaching children, not on meeting their physical needs...

es, oversaw much of his upbringing; as a result he reportedly had a "warm and close" relationship with her. After a short introduction to schooling in Dublin he was sent to Edinburgh Academy

Edinburgh Academy

The Edinburgh Academy is an independent school which was opened in 1824. The original building, in Henderson Row on the northern fringe of the New Town of Edinburgh, Scotland, is now part of the Senior School...

, where he stayed with his aunts Doodles and Connie May. At the age of ten he received a telegram from his father asking "would you like to go into the Navy?" At the time, the family had no maritime connections, and Cunningham only had a vague interest in the sea. Nevertheless he replied "Yes, I should like to be an Admiral". He was then sent to a Naval Preparatory School, Stubbington House, which specialised in sending pupils through the Dartmouth

Britannia Royal Naval College

Britannia Royal Naval College is the initial officer training establishment of the Royal Navy, located on a hill overlooking Dartmouth, Devon, England. While Royal Naval officer training has taken place in the town since 1863, the buildings which are seen today were only finished in 1905, and...

entrance examinations. Cunningham passed the exams showing particular strength in mathematics.

Early naval career

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

as a cadet aboard the training ship HMS Britannia

HMS Prince of Wales (1860)

HMS Prince of Wales was one of six 121-gun screw-propelled first-rate three-decker line-of-battle ships of the Royal Navy. She was launched on 25 January 1860...

in 1897. One of his classmates was future Admiral of the Fleet James Fownes Somerville. Cunningham was known for his lack of enthusiasm for field sports, although he did enjoy golf and spent most of his spare time "messing around in boats". He said in his memoirs that by the end of his course he was "anxious to seek adventure at sea". Although he committed numerous minor misdemeanors, he still obtained a very good for conduct. He passed out tenth in April, 1898, with first-class-marks for mathematics and seamanship

Seamanship

Seamanship is the art of operating a ship or boat.It involves a knowledge of a variety of topics and development of specialised skills including: navigation and international maritime law; weather, meteorology and forecasting; watchstanding; ship-handling and small boat handling; operation of deck...

.

His first service was as a Midshipman

Midshipman

A midshipman is an officer cadet, or a commissioned officer of the lowest rank, in the Royal Navy, United States Navy, and many Commonwealth navies. Commonwealth countries which use the rank include Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, India, Pakistan, Singapore, Sri Lanka and Kenya...

on HMS Doris

HMS Doris (1896)

HMS Doris was an Eclipse-class masted cruiser of the Royal Navy. She was built at Barrow by Naval Construction and Armaments Company and laid down on 29 August 1894, being launched 3 March 1896, and completed for service 18 November 1897....

in 1899, serving at the Cape of Good Hope Station

Cape of Good Hope Station

The Cape of Good Hope Station was one of the geographical divisions into which the British Royal Navy divided its worldwide responsibilities. It was formally the units and establishments responsible to the Commander-in-Chief, Cape of Good Hope....

when the Second Boer War

Second Boer War

The Second Boer War was fought from 11 October 1899 until 31 May 1902 between the British Empire and the Afrikaans-speaking Dutch settlers of two independent Boer republics, the South African Republic and the Orange Free State...

began. By February, 1900, he had transferred into the Naval Brigade

Naval Brigade

A Naval Brigade is a body of sailors serving in a ground combat role to augment land forces.-Royal Navy:Within the Royal Navy, a Naval Brigade is a large temporary detachment of Royal Marines and of seamen from the Royal Navy formed to undertake operations on shore, particularly during the mid- to...

as he believed "this promised opportunities for bravery and distinction in action." Cunningham then saw action at Pretoria and Diamond Hill

Battle of Diamond Hill

The Battle of Diamond Hill took place on 11 and 12 June 1900 during the Second Boer War. Fourteen thousand British soldiers squared up against four thousand Boers and forced them from their positions on the hill....

as part of the Naval Brigade. He then went back to sea, as Midshipman in HMS Hannibal

HMS Hannibal (1896)

HMS Hannibal was a Majestic class pre-dreadnought battleship and the sixth ship to bear the name HMS Hannibal.-Technical characteristics:...

in December, 1901. The following November he joined the protected cruiser

Protected cruiser

The protected cruiser is a type of naval cruiser of the late 19th century, so known because its armoured deck offered protection for vital machine spaces from shrapnel caused by exploding shells above...

HMS Diadem

HMS Diadem (1896)

HMS Diadem was the lead ship of the Diadem-class of protected cruiser in the Royal Navy. She was built at Fairfield Shipbuilding & Engineering Co Ltd, Govan and launched on 21 October 1896. She served in the First World War with her sisters. In 1914 she was a stokers' training ship, and was...

. Beginning in 1902, Cunningham took Sub-Lieutenant

Sub-Lieutenant

Sub-lieutenant is a military rank. It is normally a junior officer rank.In many navies, a sub-lieutenant is a naval commissioned or subordinate officer, ranking below a lieutenant. In the Royal Navy the rank of sub-lieutenant is equivalent to the rank of lieutenant in the British Army and of...

courses at Portsmouth

HMNB Portsmouth

Her Majesty's Naval Base Portsmouth is one of three operating bases in the United Kingdom for the British Royal Navy...

and Greenwich; he served as Sub-Lieutenant on the battleship

Battleship

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of heavy caliber guns. Battleships were larger, better armed and armored than cruisers and destroyers. As the largest armed ships in a fleet, battleships were used to attain command of the sea and represented the apex of a...

HMS Implacable

HMS Implacable (1899)

HMS Implacable was a Formidable-class battleship of the British Royal Navy, the second ship of the name.-Technical Description:HMS Implacable was laid down at Devonport Dockyard on 13 July 1898 and launched on 11 March 1899 in a very incomplete state to clear the building way for construction of...

, in the Mediterranean, for six months in 1903. In September 1903, he was transferred to HMS Locust

HMS Locust (1896)

HMS Locust was a B-class torpedo boat destroyer of the British Royal Navy. She was launched by Laird, Son & Company, Birkenhead, on 5 December 1896....

to serve as second-in-command. He was promoted to Lieutenant

Lieutenant

A lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer in many nations' armed forces. Typically, the rank of lieutenant in naval usage, while still a junior officer rank, is senior to the army rank...

in 1904, and served on several vessels during the next four years. In 1908, he was awarded his first command, HM Torpedo Boat No. 14

Torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval vessel designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs rammed enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes, and later designs launched self-propelled Whitehead torpedoes. They were created to counter battleships and other large, slow and...

.

First World War

Distinguished Service Order

The Distinguished Service Order is a military decoration of the United Kingdom, and formerly of other parts of the British Commonwealth and Empire, awarded for meritorious or distinguished service by officers of the armed forces during wartime, typically in actual combat.Instituted on 6 September...

and two bars

Medal bar

A medal bar or medal clasp is a thin metal bar attached to the ribbon of a military decoration, civil decoration, or other medal. It is most commonly used to indicate the campaign or operation the recipient received the award for, and multiple bars on the same medal are used to indicate that the...

. In 1911 he was given command of the destroyer

Destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast and maneuverable yet long-endurance warship intended to escort larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against smaller, powerful, short-range attackers. Destroyers, originally called torpedo-boat destroyers in 1892, evolved from...

HMS Scorpion

HMS Scorpion (1910)

HMS Scorpion was one of sixteen s in service with the Royal Navy in the First World War. She was built by Fairfields Govan shipyards on the Clyde and was commissioned on 30 August 1910...

, which he commanded throughout the war. In 1914, Scorpion was involved in the shadowing of the German

German Navy

The German Navy is the navy of Germany and is part of the unified Bundeswehr .The German Navy traces its roots back to the Imperial Fleet of the revolutionary era of 1848 – 52 and more directly to the Prussian Navy, which later evolved into the Northern German Federal Navy...

battlecruiser

Battlecruiser

Battlecruisers were large capital ships built in the first half of the 20th century. They were developed in the first decade of the century as the successor to the armoured cruiser, but their evolution was more closely linked to that of the dreadnought battleship...

and cruiser

Cruiser

A cruiser is a type of warship. The term has been in use for several hundreds of years, and has had different meanings throughout this period...

SMS Goeben and SMS Breslau

Pursuit of Goeben and Breslau

The pursuit of Goeben and Breslau was a naval action that occurred in the Mediterranean Sea at the outbreak of the First World War when elements of the British Mediterranean Fleet attempted to intercept the German Mittelmeerdivision comprising the battlecruiser and the light cruiser...

. This operation was intended to find and destroy the Goeben and the Breslau but the German warships evaded the British fleet, and passed through the Dardanelles

Dardanelles

The Dardanelles , formerly known as the Hellespont, is a narrow strait in northwestern Turkey connecting the Aegean Sea to the Sea of Marmara. It is one of the Turkish Straits, along with its counterpart the Bosphorus. It is located at approximately...

to reach Constantinople

Constantinople

Constantinople was the capital of the Roman, Eastern Roman, Byzantine, Latin, and Ottoman Empires. Throughout most of the Middle Ages, Constantinople was Europe's largest and wealthiest city.-Names:...

. Their arrival contributed to the Ottoman Empire

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

joining the Central Powers

Central Powers

The Central Powers were one of the two warring factions in World War I , composed of the German Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulgaria...

in November 1914. Though a bloodless "battle", the failure of the British pursuit had enormous political and military ramifications—in the words of Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

, they brought "more slaughter, more misery and more ruin than has ever before been borne within the compass of a ship."

Cunningham stayed on in the Mediterranean and in 1915 Scorpion was involved in the attack on the Dardanelles

Naval operations in the Dardanelles Campaign

The naval operations in the Dardanelles Campaign of the First World War were mainly carried out by the Royal Navy with substantial support from the French and minor contributions from Russia and Australia. The Dardanelles Campaign began as a purely naval operation...

. For his performance Cunningham was rewarded with promotion to Commander

Commander

Commander is a naval rank which is also sometimes used as a military title depending on the individual customs of a given military service. Commander is also used as a rank or title in some organizations outside of the armed forces, particularly in police and law enforcement.-Commander as a naval...

and the award of the Distinguished Service Order. Cunningham spent much of 1916 on routine patrols. In late 1916, he was engaged in convoy protection, a duty he regarded as mundane. He had no contact with German U-boats during this time, on which he commented; "The immunity of my convoys was probably due to sheer luck". Convinced that the Mediterranean held few offensive possibilities he requested to sail for home. Scorpion paid off on 21 January 1918. In his seven years as captain of the Scorpion, Cunningham had developed a reputation for first class seamanship. He was transferred by Vice-Admiral Roger Keyes to HMS Termagent, part of Keyes' Dover Patrol

Dover Patrol

The Dover Patrol was a Royal Navy command of the First World War, notable for its involvement in the Zeebrugge Raid on 22 April 1918. The Dover Patrol formed a discrete unit of the Royal Navy based at Dover and Dunkirk for the duration of the First World War...

, in April 1918. and for his actions with the Dover Patrol, he was awarded a bar

Medal bar

A medal bar or medal clasp is a thin metal bar attached to the ribbon of a military decoration, civil decoration, or other medal. It is most commonly used to indicate the campaign or operation the recipient received the award for, and multiple bars on the same medal are used to indicate that the...

to his DSO the following year.

Association with Cowan

Cunningham saw much action in the interwar years. In 1919, he commanded the S class destroyerS class destroyer (1916)

The S class were a class of 67 destroyers built from 1917 for the Royal Navy. The design was based on the Admiralty modified R class and all ships had names beginning with S or T....

HMS Seafire, on duty in the Baltic

Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is a brackish mediterranean sea located in Northern Europe, from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from 20°E to 26°E longitude. It is bounded by the Scandinavian Peninsula, the mainland of Europe, and the Danish islands. It drains into the Kattegat by way of the Øresund, the Great Belt and...

. The Communists, the White Russian

White movement

The White movement and its military arm the White Army - known as the White Guard or the Whites - was a loose confederation of Anti-Communist forces.The movement comprised one of the politico-military Russian forces who fought...

s, several varieties of Latvian nationalists, Germans, and the Poles

Poles

thumb|right|180px|The state flag of [[Poland]] as used by Polish government and diplomatic authoritiesThe Polish people, or Poles , are a nation indigenous to Poland. They are united by the Polish language, which belongs to the historical Lechitic subgroup of West Slavic languages of Central Europe...

were trying to control Latvia

Latvia

Latvia , officially the Republic of Latvia , is a country in the Baltic region of Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by Estonia , to the south by Lithuania , to the east by the Russian Federation , to the southeast by Belarus and shares maritime borders to the west with Sweden...

; the British Government had recognised Latvia's independence after the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was a peace treaty signed on March 3, 1918, mediated by South African Andrik Fuller, at Brest-Litovsk between Russia and the Central Powers, headed by Germany, marking Russia's exit from World War I.While the treaty was practically obsolete before the end of the year,...

. It was on this voyage that Cunningham first met Admiral

Admiral (United Kingdom)

Admiral is a senior rank of the Royal Navy of the United Kingdom, which equates to the NATO rank code OF-9, outranked only by the rank Admiral of the Fleet...

Walter Cowan

Walter Cowan

Admiral Sir Walter Henry Cowan, 1st Baronet, KCB, MVO, DSO & & Bar , known as Tich Cowan, was a British Royal Navy admiral who saw service in both World War I and World War II; in the latter he was one of the oldest British servicemen on active duty.-Early days:Cowan was born in Crickhowell,...

. Cunningham was impressed by Cowan's methods, specifically his navigation of the potentially dangerous seas, with thick fog and minefields

Naval mine

A naval mine is a self-contained explosive device placed in water to destroy surface ships or submarines. Unlike depth charges, mines are deposited and left to wait until they are triggered by the approach of, or contact with, an enemy vessel...

threatening the fleet. Throughout several potentially problematic encounters with German forces trying to undermine the Latvian independence movement, Cunningham exhibited "good self control and judgement". Cowan was quoted as saying "Commander Cunningham has on one occasion after another acted with unfailing promptitude and decision, and has proved himself an Officer of exceptional valour and unerring resolution."

For his actions in the Baltic

Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is a brackish mediterranean sea located in Northern Europe, from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from 20°E to 26°E longitude. It is bounded by the Scandinavian Peninsula, the mainland of Europe, and the Danish islands. It drains into the Kattegat by way of the Øresund, the Great Belt and...

, Cunningham was awarded a second bar to his DSO, and promoted to Captain

Captain (Royal Navy)

Captain is a senior officer rank of the Royal Navy. It ranks above Commander and below Commodore and has a NATO ranking code of OF-5. The rank is equivalent to a Colonel in the British Army or Royal Marines and to a Group Captain in the Royal Air Force. The rank of Group Captain is based on the...

in 1920. On his return from the Baltic in 1922, he was appointed Captain of the British 6th Destroyer Flotilla. Further commands were to follow; the British 1st Destroyer Flotilla in 1923, and the destroyer base, HMS Lochinvar, at Port Edgar

Port Edgar

Port Edgar is a marina situated on the south shore of the Firth of Forth immediately to the west of the southern end of the Forth Road Bridge in the town of South Queensferry, Scotland. In previous years it had been the site of HMS Lochinvar. In the inter war period Port Edgar was the a destroyer...

in the Firth of Forth

Firth of Forth

The Firth of Forth is the estuary or firth of Scotland's River Forth, where it flows into the North Sea, between Fife to the north, and West Lothian, the City of Edinburgh and East Lothian to the south...

, from 1927–1926. Cunningham renewed his association with Vice Admiral Cowan between 1926 and 1928, when Cunningham was Flag Captain and Chief Staff Officer

Captain of the fleet

In the Royal Navy of the 18th and 19th centuries a Captain of the Fleet could be appointed to assist an admiral when the admiral had ten or more ships to command....

to Cowan while serving on the North America and West Indies Squadron. In his memoirs Cunningham made clear the "high regard" in which he held Cowan, and the many lessons he learned from him during their two periods of service together. The late 1920s found Cunningham back in the UK participating in courses at the Army's Senior Officers' School

Senior Officers' School

The Senior Officers' School is a British military establishment established in 1920 for the training of Commonwealth senior officers of all services in inter-service cooperation...

at Sheerness

Sheerness

Sheerness is a town located beside the mouth of the River Medway on the northwest corner of the Isle of Sheppey in north Kent, England. With a population of 12,000 it is the largest town on the island....

, as well as at the Imperial Defence College

Royal College of Defence Studies

The Royal College of Defence Studies is an internationally-renowned institution and component of the Defence Academy of the United Kingdom...

. While Cunningham was at the Imperial Defence College, in 1929, he married Nona Byatt (daughter of Horace Byatt, MA; the couple had no children). After a year at the College, Cunningham was given command of his first big ship; the battleship HMS Rodney. Eighteen months later, he was appointed Commodore

Commodore (Royal Navy)

Commodore is a rank of the Royal Navy above Captain and below Rear Admiral. It has a NATO ranking code of OF-6. The rank is equivalent to Brigadier in the British Army and Royal Marines and to Air Commodore in the Royal Air Force.-Insignia:...

of HMS Pembroke

HMS Pembroke

Nine ships and a number of shore establishments of the Royal Navy have been named HMS Pembroke.-Ships: was a 28-gun ship launched in 1655 and lost in a collision off Portland in 1667. was a 32-gun fifth rate launched in 1690, captured by the French in 1694 and subsequently wrecked. was a 60-gun...

, the Royal Naval barracks at Chatham

Chatham Dockyard

Chatham Dockyard, located on the River Medway and of which two-thirds is in Gillingham and one third in Chatham, Kent, England, came into existence at the time when, following the Reformation, relations with the Catholic countries of Europe had worsened, leading to a requirement for additional...

.

Promoted to Flag Rank

Aide-de-camp

An aide-de-camp is a personal assistant, secretary, or adjutant to a person of high rank, usually a senior military officer or a head of state...

to the King

George V of the United Kingdom

George V was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 through the First World War until his death in 1936....

. He was appointed Rear Admiral

Rear Admiral

Rear admiral is a naval commissioned officer rank above that of a commodore and captain, and below that of a vice admiral. It is generally regarded as the lowest of the "admiral" ranks, which are also sometimes referred to as "flag officers" or "flag ranks"...

(Destroyers) in the Mediterranean in December 1933 and was made a Companion of the Bath

Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate mediæval ceremony for creating a knight, which involved bathing as one of its elements. The knights so created were known as Knights of the Bath...

in 1934. Having hoisted his flag in the light cruiser

Cruiser

A cruiser is a type of warship. The term has been in use for several hundreds of years, and has had different meanings throughout this period...

HMS Coventry, Cunningham used his time to practice fleet

Naval fleet

A fleet, or naval fleet, is a large formation of warships, and the largest formation in any navy. A fleet at sea is the direct equivalent of an army on land....

handling for which he was to receive much praise in the Second World War. There were also fleet exercises in the Atlantic Ocean

Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's oceanic divisions. With a total area of about , it covers approximately 20% of the Earth's surface and about 26% of its water surface area...

in which he learnt the skills and values of night actions that he would also use to great effect in years to come.

On his promotion to Vice Admiral

Vice admiral (United States)

In the United States Navy, the United States Coast Guard, the United States Public Health Service Commissioned Corps, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Commissioned Corps, and the United States Maritime Service, vice admiral is a three-star flag officer, with the pay grade of...

in July 1936, due to the interwar naval policy

London Naval Treaty

The London Naval Treaty was an agreement between the United Kingdom, the Empire of Japan, France, Italy and the United States, signed on April 22, 1930, which regulated submarine warfare and limited naval shipbuilding. Ratifications were exchanged in London on October 27, 1930, and the treaty went...

, further active employment seemed remote. However, a year later due to the illness of Sir Geoffrey Blake

Geoffrey Blake (Royal Navy officer)

Vice Admiral Sir Geoffrey Blake, KCB, DSO was an officer in the Royal Navy who went on to be Fourth Sea Lord.-Naval career:...

, Cunningham assumed the combined appointment of commander of the British Battlecruiser Squadron

Battlecruiser Squadron (United Kingdom)

The Battlecruiser Squadron was a Royal Navy squadron of battlecruisers that saw service from 1919 to the early part of the Second World War.- Formation :...

and second-in-command of the Mediterranean Fleet, with HMS Hood

HMS Hood (51)

HMS Hood was the last battlecruiser built for the Royal Navy. One of four s ordered in mid-1916, her design—although drastically revised after the Battle of Jutland and improved while she was under construction—still had serious limitations. For this reason she was the only ship of her class to be...

as his flagship

Flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, reflecting the custom of its commander, characteristically a flag officer, flying a distinguishing flag...

. After his long service in small ships, Cunningham considered his accommodation aboard Hood to be almost palatial, even surpassing his previous big ship experience on Rodney.

He retained command until September 1938, when he was appointed to the Admiralty

Admiralty

The Admiralty was formerly the authority in the Kingdom of England, and later in the United Kingdom, responsible for the command of the Royal Navy...

as Deputy Chief of the Naval Staff, although he did not actually take up this post until December 1939. He accepted this shore job with reluctance since he loathed administration, but the Board of Admiralty’s high regard of him was evident. For six months during an illness of Admiral Sir Roger Backhouse

Roger Backhouse

Admiral of the Fleet Sir Roger Roland Charles Backhouse GCB GCVO CMG was an Admiral of the Fleet in the Royal Navy and First Sea Lord of the British Admiralty from 1938 to 1939.-Family:...

, the then First Sea Lord

First Sea Lord

The First Sea Lord is the professional head of the Royal Navy and the whole Naval Service; it was formerly known as First Naval Lord. He also holds the title of Chief of Naval Staff, and is known by the abbreviations 1SL/CNS...

, he deputised for Backhouse on the Committee of Imperial Defence

Committee of Imperial Defence

The Committee of Imperial Defence was an important ad hoc part of the government of the United Kingdom and the British Empire from just after the Second Boer War until the start of World War II...

and on the Admiralty Board. In 1939 he was made a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath

Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate mediæval ceremony for creating a knight, which involved bathing as one of its elements. The knights so created were known as Knights of the Bath...

(KCB), becoming known as Sir Andrew Cunningham.

Second World War

Cunningham described the command of the Mediterranean Fleet as "The finest command the Royal Navy has to offer" and he remarked in his memoirs that "I probably knew the Mediterranean as well as any Naval Officer of my generation". Cunningham was made Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean, hoisting his flag in HMS Warspite on 6 June 1939, one day after arriving in AlexandriaAlexandria

Alexandria is the second-largest city of Egypt, with a population of 4.1 million, extending about along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea in the north central part of the country; it is also the largest city lying directly on the Mediterranean coast. It is Egypt's largest seaport, serving...

on the 5 June 1939. As Commander-in-Chief, Cunningham's main concern was for the safety of convoys heading for Egypt

Egypt

Egypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

and Malta

Malta Convoys

The Malta Convoys were a series of Allied supply convoys that sustained the besieged island of Malta during the Mediterranean Theatre of the Second World War...

. These convoys were highly significant in that they were desperately needed to keep Malta, a small British colony

British overseas territories

The British Overseas Territories are fourteen territories of the United Kingdom which, although they do not form part of the United Kingdom itself, fall under its jurisdiction. They are remnants of the British Empire that have not acquired independence or have voted to remain British territories...

and naval base, in the war. Malta was a strategic strongpoint and Cunningham fully appreciated this. Cunningham believed that the main threat to British Sea Power in the Mediterranean would come from the Italian Fleet

Regia Marina

The Regia Marina dates from the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy in 1861 after Italian unification...

. As such Cunningham had his fleet at a heightened state of readiness, so that when Italy did choose to enter into hostilities, then the British Fleet would be ready.

French Surrender (June 1940)

In his role as Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean, Cunningham had to negotiate with the French Admiral Rene-Emile GodfroyRené-Emile Godfroy

René-Emile Godfroy was a French admiral.Godfroy was born at Paris. In June 1940, he commanded French naval forces at Alexandria, where he negotiated, with British Admiral Andrew Cunningham, the peaceful internment of his ships.The French squadron consisted of the battleship Lorraine, 4 cruisers, 3...

for the demilitarisation and internment of a French squadron at Alexandria

Alexandria

Alexandria is the second-largest city of Egypt, with a population of 4.1 million, extending about along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea in the north central part of the country; it is also the largest city lying directly on the Mediterranean coast. It is Egypt's largest seaport, serving...

, in June 1940, following the Fall of France

Armistice with France (Second Compiègne)

The Second Armistice at Compiègne was signed at 18:50 on 22 June 1940 near Compiègne, in the department of Oise, between Nazi Germany and France...

. Churchill had ordered Cunningham to prevent the French warships from leaving port, and to ensure that French warships did not pass into enemy hands. Stationed at the time at Alexandria

Alexandria

Alexandria is the second-largest city of Egypt, with a population of 4.1 million, extending about along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea in the north central part of the country; it is also the largest city lying directly on the Mediterranean coast. It is Egypt's largest seaport, serving...

, Cunningham entered into delicate negotiations with Godfroy to ensure his fleet, which consisted of the battleship Lorraine

French battleship Lorraine

The Lorraine was a French Navy battleship of the Bretagne class named in honour of the region of Lorraine in France.- Construction :...

, 4 cruisers, 3 destroyers and a submarine, posed no threat. The Admiralty ordered Cunningham to complete the negotiations on 3 July. Just as an agreement seemed imminent Godfroy heard of the British action against the French at Mers el Kebir and, for a while, Cunningham feared a battle between French and British warships in the confines of Alexandria harbour

Alexandria Port

The Port of Alexandria is on the West Verge of the Nile Delta between the Mediterranean Sea and Mariut Lake in Alexandria, Egypt. Considered the second most important city and the main port in Egypt, it handles over three quarters of Egypt’s foreign trade. Alexandria port consists of two harbours ...

. The deadline was overrun but negotiations ended well, after Cunningham put them on a more personal level and had the British ships appeal to their French opposite numbers. Cunningham's negotiations succeeded and the French emptied their fuel bunkers and removed the firing mechanisms from their guns. Cunningham in turn promised to repatriate the ships' crews.

Battle of Taranto (November 1940)

North African campaign

During the Second World War, the North African Campaign took place in North Africa from 10 June 1940 to 13 May 1943. It included campaigns fought in the Libyan and Egyptian deserts and in Morocco and Algeria and Tunisia .The campaign was fought between the Allies and Axis powers, many of whom had...

, based in Egypt

Egypt

Egypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

. Although the Royal Navy had won in several actions in the Mediterranean, considerably upsetting the balance of power

Balance of power in international relations

In international relations, a balance of power exists when there is parity or stability between competing forces. The concept describes a state of affairs in the international system and explains the behavior of states in that system...

, the Italians who were following the theory of a fleet in being

Fleet in being

In naval warfare, a fleet in being is a naval force that extends a controlling influence without ever leaving port. Were the fleet to leave port and face the enemy, it might lose in battle and no longer influence the enemy's actions, but while it remains safely in port the enemy is forced to...

had left their ships in harbour. This made the threat of a sortie

Sortie

Sortie is a term for deployment or dispatch of one military unit, be it an aircraft, ship, or troops from a strongpoint. The sortie, whether by one or more aircraft or vessels, usually has a specific mission....

against the British Fleet a serious problem. At the time the harbour at Taranto contained six battleship

Battleship

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of heavy caliber guns. Battleships were larger, better armed and armored than cruisers and destroyers. As the largest armed ships in a fleet, battleships were used to attain command of the sea and represented the apex of a...

s (five of them battle-worthy), seven heavy cruiser

Heavy cruiser

The heavy cruiser was a type of cruiser, a naval warship designed for long range, high speed and an armament of naval guns roughly 203mm calibre . The heavy cruiser can be seen as a lineage of ship design from 1915 until 1945, although the term 'heavy cruiser' only came into formal use in 1930...

s, two light cruiser

Light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small- or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck...

s, and eight destroyer

Destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast and maneuverable yet long-endurance warship intended to escort larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against smaller, powerful, short-range attackers. Destroyers, originally called torpedo-boat destroyers in 1892, evolved from...

s. The Admiralty, concerned with the potential for an attack, had drawn up Operation Judgement; a surprise attack on Taranto Harbour. To carry out the attack, the Admiralty sent the new aircraft carrier HMS Illustrious, commanded by Lumley Lyster

Lumley Lyster

Vice Admiral Sir Arthur Lumley St George Lyster, KCB, CVO, CBE, DSO was a Royal Navy officer during the Second World War.-Naval career:...

, to join HMS Eagle

HMS Eagle (1918)

HMS Eagle was an early aircraft carrier of the Royal Navy. Ordered by Chile as the Almirante Cochrane, she was laid down before World War I. In early 1918 she was purchased by Britain for conversion to an aircraft carrier; this work was finished in 1924...

in Cunningham's fleet.

The attack started at 21:00, 11 November 1940, when the first of two waves of Fairey Swordfish

Fairey Swordfish

The Fairey Swordfish was a torpedo bomber built by the Fairey Aviation Company and used by the Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Navy during the Second World War...

torpedo bombers took off from Illustrious, followed by the second wave an hour later. The attack was a great success: the Italian fleet lost half its strength in one night. The "fleet-in-being" diminished in importance and the threat to the Royal Navy's control of the Mediterranean had been considerably reduced. Cunningham said of the victory: "Taranto, and the night of November 11–12, 1940, should be remembered for ever as having shown once and for all that in the Fleet Air Arm

Fleet Air Arm

The Fleet Air Arm is the branch of the British Royal Navy responsible for the operation of naval aircraft. The Fleet Air Arm currently operates the AgustaWestland Merlin, Westland Sea King and Westland Lynx helicopters...

the Navy has its most devastating weapon." The Royal Navy had launched the first all-aircraft naval attack in history, flying a small number of aircraft from an aircraft carrier. This, and other aspects of the raid, were important facts in the planning of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941

Attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike conducted by the Imperial Japanese Navy against the United States naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on the morning of December 7, 1941...

: the Japanese planning staff were thought to have studied it intensively.

Cunningham's official reaction at the time was memorably terse. After landing the last of the attacking aircraft, Illustrious signalled "Operation Judgement executed". After seeing aerial reconnaissance photographs the next day which showed several Italian ships sunk or out of action, Cunningham replied with the two-letter code group which signified, "Manoeuvre well executed".

Battle of Cape Matapan (March 1941)

Operation Lustre

Operation Lustre was an action during World War II, involving the dispatch of British, Australian, New Zealand and Polish troops from Egypt to Greece in March and April 1941, in response to the failed Italian invasion and the looming threat of German intervention, revealed through Ultra.It was seen...

stopped, and the Italian Navy was the only force able to attempt this. Cunningham stated in his biography: "I myself was inclined to think that the Italians would not try anything. I bet Commander Power, the Staff Officer, Operations, the sum of ten shilling

Shilling

The shilling is a unit of currency used in some current and former British Commonwealth countries. The word shilling comes from scilling, an accounting term that dates back to Anglo-Saxon times where it was deemed to be the value of a cow in Kent or a sheep elsewhere. The word is thought to derive...

s that we would see nothing of the enemy." Under pressure from Germany, the Italian Fleet planned to launch an attack on the British Fleet on 28 March 1941.

The Italian commander, Admiral Angelo Iachino

Angelo Iachino

Angelo Iachino was an Italian admiral during World War II.-Early life and career:Born at Sanremo, Liguria, Iachino entered the Italian Naval Academy at Livorno in 1904, and graduated in 1907....

, intended to carry out a surprise attack on the British Cruiser Squadron in the area (commanded by Vice-Admiral Sir Henry Pridham-Wippell), executing a pincer movement

Pincer movement

The pincer movement or double envelopment is a military maneuver. The flanks of the opponent are attacked simultaneously in a pinching motion after the opponent has advanced towards the center of an army which is responding by moving its outside forces to the enemy's flanks, in order to surround it...

with the battleship Vittorio Veneto

Italian battleship Vittorio Veneto