Pursuit of Goeben and Breslau

Encyclopedia

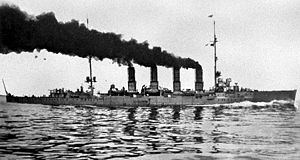

The pursuit of Goeben and Breslau was a naval action that occurred in the Mediterranean Sea

at the outbreak of the First World War

when elements of the British Mediterranean Fleet attempted to intercept the German

Mittelmeerdivision

comprising the battlecruiser

and the light cruiser

. The German ships evaded the British fleet and passed through the Dardanelles

to reach Constantinople

where their arrival was a catalyst that contributed to the Ottoman Empire

joining the Central Powers

by issuing a declaration of war

against the Triple Entente

.

Though a bloodless "battle", the failure of the British pursuit had enormous political and military ramifications—in the words of Winston Churchill

, they brought "more slaughter, more misery, and more ruin than has ever before been borne within the compass of a ship."

(Imperial Navy), comprising only the Goeben and Breslau, was under the command of Konteradmiral

Wilhelm Souchon

. In the event of war, the squadron′s role was to intercept French

transports bringing colonial troops from Algeria

to France.

When war broke out between Austria-Hungary

and Serbia

on 28 July 1914, Souchon was at Pola

in the Adriatic where Goeben was undergoing repairs to her boiler

s. Not wishing to be trapped in the Adriatic, Souchon rushed to finish as much work as possible, but then took his ships out into the Mediterranean before all repairs were completed. He reached Brindisi

on 1 August, but Italian authorities made excuses to avoid coal

ing the ship; Italy, despite being a signatory to the Triple Alliance

, was still neutral. Goeben was joined by Breslau at Taranto

and the small squadron sailed for Messina where Souchon was able to obtain 2000 ST (1,814.4 t) of coal from German merchant ships.

Meanwhile, on 30 July Winston Churchill

Meanwhile, on 30 July Winston Churchill

—the First Lord of the Admiralty—had instructed the commander of the British Mediterranean Fleet, Admiral

Sir Archibald Berkeley Milne

, to cover the French transports taking the XIX Corps from North Africa across the Mediterranean to France. The Mediterranean Fleet—based at Malta

—comprised three fast, modern battlecruisers , as well as four armoured cruisers, four light cruiser

s and a flotilla of 14 destroyer

s.

Milne′s instructions were "to aid the French in the transportation of their African Army by covering, and if possible, bringing to action individual fast German ships, particularly Goeben, who may interfere in that action. You will be notified by telegraph when you may consult with the French Admiral. Do not at this stage be brought to action against superior forces, except in combination with the French, as part of a general battle. The speed of your squadrons is sufficient to enable you to choose your moment. We shall hope to reinforce the Mediterranean, and you must husband your forces at the outset." Churchill′s orders did not explicitly state what he meant by "superior forces". He later claimed that he was referring to "the Austrian Fleet against whose battleships it was not desirable that our three battle-cruisers should be engaged without battleship support."

Milne assembled his force at Malta on 1 August. On 2 August, he received instructions to shadow Goeben with two battlecruisers while maintaining a watch on the Adriatic, ready for a sortie

by the Austrians. Indomitable, Indefatigable, five cruisers and eight destroyers commanded by Rear Admiral

Ernest Troubridge

were sent to cover the Adriatic. Goeben had already departed but was sighted that same day at Taranto by the British Consul, who informed London. Fearing the German ships might be trying to escape to the Atlantic, the Admiralty

ordered that Indomitable and Indefatigable be sent West toward Gibraltar. Milne′s other task of protecting French ships was complicated by the lack of any direct communications with the French navy, which had meanwhile postponed the sailing of the troop ships. The light cruiser was sent to search the Straits of Messina for Goeben. However, by this time, on the morning of 3 August, Souchon had departed Messina heading west.

Without specific orders, Souchon had decided to position his ships off the coast of Africa

Without specific orders, Souchon had decided to position his ships off the coast of Africa

, ready to engage when hostilities commenced. He planned to bombard the embarkation ports of Bône

and Philippeville in French Algeria

. Goeben was heading for Philippeville, while Breslau was detached to deal with Bône. At 18:00 on 3 August, while still sailing west, he received word that Germany had declared war on France. Then, early on 4 August, Souchon received orders from Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz

reading: "Alliance with government of

CUP

concluded August 3. Proceed at once to İstanbul

." So close to his targets, Souchon pushed on and his ships, flying the Russia

n flag as he approached, carried out their bombardment at dawn before breaking off and heading back to Messina for more coal.

Under a pre-war agreement with Britain, France was able to concentrate her entire fleet in the Mediterranean, leaving the Royal Navy

to ensure the security of France′s Atlantic coast. Three squadrons of the French fleet were covering the transports. However, assuming that Goeben would continue west, the French commander—Admiral de Lapeyrère

—sent no ships to make contact and so Souchon was able to slip away to the east.

In Souchon′s path were the two British battlecruisers, Indomitable and Indefatigable, which made contact at 09:30 on 4 August, passing the German ships in the opposite direction. Unlike France, Britain was not yet at war with Germany (the declaration would not be made until later that day, following the start of the German invasion of neutral Belgium

), and so the British ships commenced shadowing Goeben and Breslau. Milne reported the contact and position, but neglected to inform the Admiralty that the German ships were heading east. Churchill therefore still expected them to threaten the French transports, and he authorized Milne to engage the German ships if they attacked. However, a meeting of the British Cabinet decided that hostilities could not start before a declaration of war, and at 14:00 Churchill was obliged to cancel his authorization to attack.

The rated speed of Goeben was 27 kn (32.9 mph; 52.9 km/h), but her damaged boilers meant she could only manage 24 kn (29.2 mph; 47 km/h), and this was only achieved by working men and machinery to the limit; four stokers were killed by scalding steam

The rated speed of Goeben was 27 kn (32.9 mph; 52.9 km/h), but her damaged boilers meant she could only manage 24 kn (29.2 mph; 47 km/h), and this was only achieved by working men and machinery to the limit; four stokers were killed by scalding steam

. Fortunately for Souchon, both British battlecruisers were also suffering from problems with their boilers and were unable to keep Goeben′s pace. The light cruiser maintained contact, while Indomitable and Indefatigable fell behind. In fog and fading light, Dublin lost contact off Cape San Vito on the north coast of Sicily

at 19:37. Goeben and Breslau returned to Messina the following morning, by which time Britain and Germany were at war.

The Admiralty ordered Milne to respect Italian neutrality and stay outside a 6 mi (5.2 nmi; 9.7 km) limit from the Italian coast—which precluded entrance into the passage of the Straits of Messina. Consequently, Milne posted guards on the exits from the Straits. Still expecting Souchon to head for the transports and the Atlantic, he placed two battlecruisers—Inflexible and Indefatigable—to cover the northern exit (which gave access to the western Mediterranean), while the southern exit of the Straits was covered by a single light cruiser, . Milne sent Indomitable west to coal at Bizerte

, instead of south to Malta.

For Souchon, Messina was no haven. Italian authorities insisted he depart within 24 hours and delayed supplying coal. Provisioning his ships required ripping up the decks of German merchant steamers in harbour and manually shovelling their coal into his bunkers. By the evening of 6 August, and despite the help of 400 volunteers from the merchantmen, he had only taken on 1500 ST (1,360.8 t) which was insufficient to reach Istanbul. Further messages from Tirpitz made his predicament even more dire. He was informed that Austria would provide no naval aid in the Mediterranean and that Ottoman Empire was still neutral and therefore he should no longer make for Istanbul. Faced with the alternative of seeking refuge at Pola, and probably remaining trapped for the rest of the war, Souchon chose to head for Istanbul anyway, his purpose being "to force the Ottoman Empire, even against their will, to spread the war to the Black Sea

against their ancient enemy, Russia."

Milne was instructed on 5 August to continue watching the Adriatic for signs of the Austrian fleet and to prevent the German ships joining them. He chose to keep his battlecruisers in the west, dispatching Dublin to join Troubridge′s cruiser squadron in the Adriatic, which he believed would be able to intercept Goeben and Breslau. Troubridge was instructed 'not to get seriously engaged with superior forces', once again intended as a warning against engaging the Austrian fleet. When Goeben and Breslau emerged into the eastern Mediterranean on 6 August, they were met by Gloucester which, being out-gunned, began to shadow the German ships.

Troubridge′s squadron comprised the armoured cruisers , , , and eight destroyers armed with torpedoes. The cruisers had 9.2 in (233.7 mm) guns versus the 11 in (279.4 mm) guns of Goeben and had armour a maximum of 6 in (15.2 cm) thick compared to the battlecruiser′s 11 in (27.9 cm) armour belt. This meant that Troubridge′s squadron was not only out-ranged and vulnerable to Goeben′s powerful guns, but it was unlikely his cruiser′s guns could seriously damage the German ship at all—even at short range. In addition, the British ships were several knots slower than Goeben, despite her damaged boilers, meaning that she could dictate the range of the battle if she spotted the British squadron in advance. Consequently, Troubridge considered his only chance was to locate and engage Goeben in favourable light, at dawn, with Goeben east of his ships and ideally launch a torpedo attack with his destroyers, however at least five of the destroyers did not have enough coal to keep up with the cruisers steaming at full speed. By 04:00 on 7 August, Troubridge realised he would not be able to intercept the German ships before daylight and after some deliberation he signalled Milne with his intentions to break off the chase, mindful of Churchill′s ambiguous order to avoid engaging a "superior force". No reply was received until 10:00, by which time he had withdrawn to Zante to refuel.

Milne ordered Gloucester to disengage, still expecting Souchon to turn west, but it was apparent to Gloucester′s captain that Goeben was fleeing. Breslau attempted to harass Gloucester into breaking off—Souchon had a collier

Milne ordered Gloucester to disengage, still expecting Souchon to turn west, but it was apparent to Gloucester′s captain that Goeben was fleeing. Breslau attempted to harass Gloucester into breaking off—Souchon had a collier

waiting off the coast of Greece

and needed to shake his pursuer before he could rendezvous. Gloucester finally engaged Breslau, hoping this would compel Goeben to drop back and protect the light cruiser. According to Souchon, Breslau was hit, but no damage was done. The action then broke off without further hits being scored. Finally, Milne ordered Gloucester to cease pursuit at Cape Matapan

.

Shortly after midnight on 8 August, Milne took his three battlecruisers and the light cruiser east. At 14:00, he received an incorrect signal from the Admiralty stating that Britain was at war with Austria—war would not be declared until 12 August and the order was countermanded four hours later, but Milne chose to guard the Adriatic rather than seek Goeben. Finally on 9 August, Milne was given clear orders to "chase Goeben which had passed Cape Matapan on the 7th steering north-east." Milne still did not believe that Souchon was heading for the Dardanelles, and so he resolved to guard the exit from the Aegean

, unaware that Goeben did not intend to come out.

Souchon had replenished his coal off the Aegean island of Donoussa

on 9 August and the German warships resumed their voyage to Constantinople. At 17:00 on 10 August, he reached the Dardanelles and awaited permission to pass through. Germany had for some time been courting the Committee of Union and Progress

of the imperial government

, and they now used their influence to pressure the Turkish Minister of War, Enver Pasha, into granting the ship′s passage, an act that would outrage Russia which relied on the Dardanelles as its main all-season shipping route. In addition, the Germans managed to persuade Enver to order any pursuing British ships to be fired on. By the time Souchon received permission to enter the straits, his lookouts could see smoke on the horizon from approaching British ships.

Turkey was still a neutral country bound by treaty to prevent German ships passing the straits. To get around this difficulty it was agreed that the ships should become part of the Turkish navy. On 16 August, having reached Constantinople, Goeben and Breslau were transferred to the Turkish Navy in a small ceremony, becoming respectively the Yavuz Sultan Selim and the Midilli, though they retained their German crews with Souchon still in command. The initial reaction in Britain was one of satisfaction, that a threat had been removed from the Mediterranean. On 23 September, Souchon was appointed commander in chief of the Ottoman Navy.

would be enough to occupy a British naval squadron guarding the Dardanelles. However, following German reverses at the First Battle of the Marne

in September, and with Russian successes against Austria-Hungary

, Germany began to regard the Ottoman Empire as a useful ally. Tensions began to escalate when Ottoman Empire closed the Dardanelles to all shipping on 27 September, blocking Russia's exit from the Black Sea

—the Black Sea route accounted for over 90% of Russia's import and export traffic.

Germany′s gift of the two modern warships had an enormous positive impact with the Turkish population. At the outbreak of the war, Churchill had caused outrage when he "requisitioned" two almost completed Turkish battleship

s in British shipyards, the Sultan Osman I and the Reshadieh, that had been financed by public subscription at a cost of £6,000,000. Turkey was offered compensation of £1,000 per day for so long as the war might last, provided she remained neutral. (These ships were commissioned into the Royal Navy

as and respectively.) The Turks had been neutral, though the navy had been pro-British (having purchased 40 warships from British shipyards) while the army was in favour of Germany, so the two incidents helped resolve the deadlock and the Ottoman Empire would join the Central Powers

.

Continued diplomacy

from France and Russia attempted to keep the Ottoman Empire out of the war, but Germany was agitating for a commitment. In the aftermath of Souchon′s daring dash to Constantinople, on 15 August 1914 the Ottomans canceled their maritime agreement with Britain and the Royal Navy mission under Admiral Limpus left by 15 September.

Finally, on 29 October, the point of no return was reached when Admiral Souchon took Goeben, Breslau and a squadron of Turkish warships into the Black Sea and raided the Russian ports of Novorossiysk

, Odessa

and Sevastopol

. For 25 minutes, Goeben′s main and secondary guns fired on Sevastopol. In reply, two 12 in (304.8 mm) shells fired from a Russian fort at an extreme range of over 10 mi (8.7 nmi; 16.1 km) blew a pair of holes in the ship's aft smoke-stack killing 14 men. On the return journey, Goeben hit the Russian destroyer Leiteneat Pushchin with two 5.9 in (150 mm) shells and sank the Russian minelayer Prut which had 700 mines on board in order to lay a minefield across the battle-cruiser's homeward route.

The attack on Novorossiysk was also an outstanding success, with 14 steamers in the harbour sunk by Breslau′s guns while 40 oil tanks were set on fire, liberating streams of burning petroleum

that engulfed whole streets. Russia declared war on the Ottoman Empire on 2 November and France and Britain followed on 5 November. The first land battles were expected in the Caucasus

, and transport steamers started carrying Turkish troops eastwards along the Anatolian coast to Samsun

and Trebizond. The Russian Black Sea Fleet sank three of these ships so when another convoy sailed on 16 November; Breslau accompanied them as an escort while Goeben—which had located and severed the Sevastopol-Odessa submarine cable on the night 10/11 November—cruised in the middle of the Black Sea.

On 18 November, in a dense bank of fog, Breslau joined her consort and the two German ships were almost on top of the Russian Fleet, a chance gust of wind momentarily stirred the fog, and suddenly the antagonists were in each other′s view at less than 4000 yd (3,657.6 m) range. Instantly, the guns of both sides opened fire. Goeben—with Breslau sheltering behind her—found herself sailing past the entire line of the Black Sea Fleet. A 12 in (304.8 mm) shell from a Russian battleship tore through the armour of Goeben′s 5.9 in (150 mm) casement, killing the six-man gun crew and detonating the ammunition. Only swift flooding of a magazine prevented a bigger explosion, but the Russian flagship Evstafi was hit four times by Goeben, killing 33 men and the Russian battleship Rostislav were badly damaged. The Black Sea Fleet quickly hid itself again in the mist and continued to threaten the Turkish Black Sea coast for the rest of the war.

In November and December, Breslau and the light cruiser Hamidie undertook frequent troopship escorts to the Caucasus, but the Goeben consumed too much coal for this kind of work, although on 10 December she fired fifteen 11 in (279.4 mm) shells at the Russian shore defenses of Batumi

. Intense Russian wireless activity

on 23 December made it evident that the Black Sea Fleet had left the harbour. Goeben and Breslau were sent out to provide escort for some transports and as night fell over a rough, wind-lashed sea the German light cruiser was detached to reconnoitre to the NE. The Russian radios were silent now, and the whereabouts of the Black Sea Fleet was problematical. At 04:00, Breslau encountered the Russian fleet. Her searchlight illuminated a transport, which was sunk with a single salvo, and then the forbidding silhouette of a Russian battleship was caught in its beam. A second salvo from Breslau straddled the massive vessel before the light cruiser sought refuge in the darkness.

While returning from another troop transport on 26 December, Goeben was mined off the Bosphorus. The first mine exploded to the starboard beneath the conning tower, which immediately caused a 30º list to port. Two minutes later, the ship hit a second mine, this time off the port wing barbette

, where 600 ST (544.3 t) of water disabled No. 3 turret and flooded the ship. The stricken battlecruiser was barely able to reach Stenia Creek. The damage was serious and kept Goeben in port for three months, apart from two brief sorties intended to deter Russian battleships that were apparently approaching İstanbul

.

On 3 April, Goeben left the Bosphorus in company with Breslau to cover the withdrawal of the Turkish cruisers Hamidie and Medjidie, which had been sent to bombard Nikolayev. Medjidie struck a mine and sank, so this attack had to be abandoned, but the two German ships appeared off Sevastopol and tempted out the Black Sea Fleet. Although six Russian battleships—supported by two cruisers and five destroyers—were bearing down upon them, Goeben and Breslau sank two cargo steamers and then deliberately loitered about to draw on their pursuers. Hamidie had to be given time to return to the Bosphorus with survivors from the Medjidie.

When the range had closed to about 15000 yd (13,716 m), Breslau slipped between her sister and the Russian squadron and laid a dense smoke screen. Under its cover, the German ships turned away, but kept their speed down so as not to discourage pursuit. Eagerly, the Russians chased after them, the ponderous battleships at their maximum 25 kn (30.4 mph; 49 km/h). At one point, Breslau fell back far enough to draw fire from the Russian line, but she spurted out of range again before any hits were sustained. As darkness fell, Goeben and Breslau began to pull away from their pursuers, for Hamidie had radioed that she was almost home, but in the darkness Russian destroyers closed on Goeben, stalking her in her smoke. But their wireless chatter betrayed them and Goeben′s four 60 in (1,524 mm) stern searchlights stabbed back down her wake, illuminating the sinister shapes of five destroyers only 200 yd (182.9 m) astern.

Breslau′s guns crashed out, and the first destroyer burst into flames, mortally hit. The second in line suffered a similar fate, the remainder turned tail and fled. None of their torpedo

es had found a mark, and at noon the following day Goeben and Breslau were once more off the Bosphorus.

With the Ottoman Empire at war, a new theatre was opened, the Middle Eastern theatre

, with main fronts of Gallipoli

, the Sinai and Palestine

, Mesopotamia

, and in Caucasus

. The course of the war in the Balkans

was also influenced by the entry of the Ottoman Empire on the side of the Central Powers

.

s, Troubridge was court-martial

led in November on the charge that "he did forbear to chase His Imperial German Majesty′s ship Goeben, being an enemy then flying." The charge was not proved on the grounds that he was under orders not to engage a "superior force". He commanded the naval forces off the Dardanelles before being given command of a force on the Danube

in 1915 against the Austro-Hungarians.

General Ludendorff stated in his memoirs that he believed the entry of the Turks into the war allowed the outnumbered Central powers to fight on for two years longer than they would have been able on their own. The war was extended to the Middle East

with main fronts of Gallipoli

, the Sinai and Palestine

, Mesopotamia

, and in Caucasus

. The course of the war in the Balkans

was also influenced by the entry of the Ottoman Empire on the side of the Central Powers

. Had the war ended in 1916, that would have meant that some of the bloodiest engagements, such as the Battle of the Somme, would have been avoided. The United States

might not have been drawn from its policy of isolation to intervene in a foreign war.

In allying with the Central Powers, the Turks also shared their fate in ultimate defeat. This gave the victorious allies the opportunity to carve up the collapsed Ottoman Empire to suit their political whims. Many new nations were created including Palestine, Syria, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia and Iraq, and the idea of a Jewish state in Israel was considered for the first time.

Also, the closure of Russia′s only ice-free trade route through the Dardanelles effectively strangled the Russian economy. Unable to export grain nor import munitions, the Russian army was isolated from her allies and slowly began to collapse. Combined with the German decision to release Vladimir Lenin

in 1917, the sealing off of the Black Sea was one of the critical contributors to the "revolutionary situation" in Russia which would explode into the October Revolution

.

, imagines Admiral Christopher Cradock

in place of Admiral Troubridge as commander of the cruiser and destroyer force to the east of the Straits of Messina; in the story, Cradock ignores Admiral Milne′s instructions to guard the Adriatic Sea

and instead intercepts the Goeben and Breslau north of Crete

. In the ensuing battle, his fleet loses two of the four armoured cruisers and six of his eight destroyers, but manages to destroy both German ships before they reach their goal of Istanbul. In reality, Cradock was not present in the Mediterranean, but died a few weeks later at the Battle of Coronel

after challenging a larger German force, a decision made in part because he wanted to avoid Troubridge's ignominy in allowing Goeben and Breslau to escape.

Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean surrounded by the Mediterranean region and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Anatolia and Europe, on the south by North Africa, and on the east by the Levant...

at the outbreak of the First World War

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

when elements of the British Mediterranean Fleet attempted to intercept the German

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

Mittelmeerdivision

Mediterranean Division

The Mediterranean Division was a division consisting of one battlecruiser , one light cruiser , and a yacht of the Kaiserliche Marine. It saw service in the First Balkan War, Second Balkan War, and First World War...

comprising the battlecruiser

Battlecruiser

Battlecruisers were large capital ships built in the first half of the 20th century. They were developed in the first decade of the century as the successor to the armoured cruiser, but their evolution was more closely linked to that of the dreadnought battleship...

and the light cruiser

Light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small- or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck...

. The German ships evaded the British fleet and passed through the Dardanelles

Dardanelles

The Dardanelles , formerly known as the Hellespont, is a narrow strait in northwestern Turkey connecting the Aegean Sea to the Sea of Marmara. It is one of the Turkish Straits, along with its counterpart the Bosphorus. It is located at approximately...

to reach Constantinople

Constantinople

Constantinople was the capital of the Roman, Eastern Roman, Byzantine, Latin, and Ottoman Empires. Throughout most of the Middle Ages, Constantinople was Europe's largest and wealthiest city.-Names:...

where their arrival was a catalyst that contributed to the Ottoman Empire

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

joining the Central Powers

Central Powers

The Central Powers were one of the two warring factions in World War I , composed of the German Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulgaria...

by issuing a declaration of war

Declaration of war

A declaration of war is a formal act by which one nation goes to war against another. The declaration is a performative speech act by an authorized party of a national government in order to create a state of war between two or more states.The legality of who is competent to declare war varies...

against the Triple Entente

Triple Entente

The Triple Entente was the name given to the alliance among Britain, France and Russia after the signing of the Anglo-Russian Entente in 1907....

.

Though a bloodless "battle", the failure of the British pursuit had enormous political and military ramifications—in the words of Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

, they brought "more slaughter, more misery, and more ruin than has ever before been borne within the compass of a ship."

Prelude

Dispatched in 1912, the Mittelmeerdivision of the Kaiserliche MarineKaiserliche Marine

The Imperial German Navy was the German Navy created at the time of the formation of the German Empire. It existed between 1871 and 1919, growing out of the small Prussian Navy and Norddeutsche Bundesmarine, which primarily had the mission of coastal defense. Kaiser Wilhelm II greatly expanded...

(Imperial Navy), comprising only the Goeben and Breslau, was under the command of Konteradmiral

Counter Admiral

Counter admiral is a rank found in many navies of the world, but no longer used in English-speaking countries, where the equivalent rank is rear admiral...

Wilhelm Souchon

Wilhelm Souchon

Wilhelm Anton Souchon was a German and Ottoman admiral in World War I who commanded the Kaiserliche Marine's Mediterranean squadron in the early days of the war...

. In the event of war, the squadron′s role was to intercept French

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

transports bringing colonial troops from Algeria

Algeria

Algeria , officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria , also formally referred to as the Democratic and Popular Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of Northwest Africa with Algiers as its capital.In terms of land area, it is the largest country in Africa and the Arab...

to France.

When war broke out between Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary , more formally known as the Kingdoms and Lands Represented in the Imperial Council and the Lands of the Holy Hungarian Crown of Saint Stephen, was a constitutional monarchic union between the crowns of the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary in...

and Serbia

Serbia

Serbia , officially the Republic of Serbia , is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central and Southeast Europe, covering the southern part of the Carpathian basin and the central part of the Balkans...

on 28 July 1914, Souchon was at Pola

Pula

Pula is the largest city in Istria County, Croatia, situated at the southern tip of the Istria peninsula, with a population of 62,080 .Like the rest of the region, it is known for its mild climate, smooth sea, and unspoiled nature. The city has a long tradition of winemaking, fishing,...

in the Adriatic where Goeben was undergoing repairs to her boiler

Boiler

A boiler is a closed vessel in which water or other fluid is heated. The heated or vaporized fluid exits the boiler for use in various processes or heating applications.-Materials:...

s. Not wishing to be trapped in the Adriatic, Souchon rushed to finish as much work as possible, but then took his ships out into the Mediterranean before all repairs were completed. He reached Brindisi

Brindisi

Brindisi is a city in the Apulia region of Italy, the capital of the province of Brindisi, off the coast of the Adriatic Sea.Historically, the city has played an important role in commerce and culture, due to its position on the Italian Peninsula and its natural port on the Adriatic Sea. The city...

on 1 August, but Italian authorities made excuses to avoid coal

Coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock usually occurring in rock strata in layers or veins called coal beds or coal seams. The harder forms, such as anthracite coal, can be regarded as metamorphic rock because of later exposure to elevated temperature and pressure...

ing the ship; Italy, despite being a signatory to the Triple Alliance

Triple Alliance (1882)

The Triple Alliance was the military alliance between Germany, Austria–Hungary, and Italy, , that lasted from 1882 until the start of World War I in 1914...

, was still neutral. Goeben was joined by Breslau at Taranto

Taranto

Taranto is a coastal city in Apulia, Southern Italy. It is the capital of the Province of Taranto and is an important commercial port as well as the main Italian naval base....

and the small squadron sailed for Messina where Souchon was able to obtain 2000 ST (1,814.4 t) of coal from German merchant ships.

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

—the First Lord of the Admiralty—had instructed the commander of the British Mediterranean Fleet, Admiral

Admiral

Admiral is the rank, or part of the name of the ranks, of the highest naval officers. It is usually considered a full admiral and above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet . It is usually abbreviated to "Adm" or "ADM"...

Sir Archibald Berkeley Milne

Archibald Berkeley Milne

Admiral Sir Berkeley Milne, 2nd Baronet GCVO KCB was a senior Royal Navy officer who commanded the Mediterranean Fleet at the outbreak of the First World War.- Naval career :...

, to cover the French transports taking the XIX Corps from North Africa across the Mediterranean to France. The Mediterranean Fleet—based at Malta

Malta

Malta , officially known as the Republic of Malta , is a Southern European country consisting of an archipelago situated in the centre of the Mediterranean, south of Sicily, east of Tunisia and north of Libya, with Gibraltar to the west and Alexandria to the east.Malta covers just over in...

—comprised three fast, modern battlecruisers , as well as four armoured cruisers, four light cruiser

Light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small- or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck...

s and a flotilla of 14 destroyer

Destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast and maneuverable yet long-endurance warship intended to escort larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against smaller, powerful, short-range attackers. Destroyers, originally called torpedo-boat destroyers in 1892, evolved from...

s.

Milne′s instructions were "to aid the French in the transportation of their African Army by covering, and if possible, bringing to action individual fast German ships, particularly Goeben, who may interfere in that action. You will be notified by telegraph when you may consult with the French Admiral. Do not at this stage be brought to action against superior forces, except in combination with the French, as part of a general battle. The speed of your squadrons is sufficient to enable you to choose your moment. We shall hope to reinforce the Mediterranean, and you must husband your forces at the outset." Churchill′s orders did not explicitly state what he meant by "superior forces". He later claimed that he was referring to "the Austrian Fleet against whose battleships it was not desirable that our three battle-cruisers should be engaged without battleship support."

Milne assembled his force at Malta on 1 August. On 2 August, he received instructions to shadow Goeben with two battlecruisers while maintaining a watch on the Adriatic, ready for a sortie

Sortie

Sortie is a term for deployment or dispatch of one military unit, be it an aircraft, ship, or troops from a strongpoint. The sortie, whether by one or more aircraft or vessels, usually has a specific mission....

by the Austrians. Indomitable, Indefatigable, five cruisers and eight destroyers commanded by Rear Admiral

Rear Admiral

Rear admiral is a naval commissioned officer rank above that of a commodore and captain, and below that of a vice admiral. It is generally regarded as the lowest of the "admiral" ranks, which are also sometimes referred to as "flag officers" or "flag ranks"...

Ernest Troubridge

Ernest Troubridge

Admiral Sir Ernest Charles Thomas Troubridge KCMG, MVO was an officer of the Royal Navy who served during the First World War, later rising to the rank of admiral....

were sent to cover the Adriatic. Goeben had already departed but was sighted that same day at Taranto by the British Consul, who informed London. Fearing the German ships might be trying to escape to the Atlantic, the Admiralty

Admiralty

The Admiralty was formerly the authority in the Kingdom of England, and later in the United Kingdom, responsible for the command of the Royal Navy...

ordered that Indomitable and Indefatigable be sent West toward Gibraltar. Milne′s other task of protecting French ships was complicated by the lack of any direct communications with the French navy, which had meanwhile postponed the sailing of the troop ships. The light cruiser was sent to search the Straits of Messina for Goeben. However, by this time, on the morning of 3 August, Souchon had departed Messina heading west.

First contact

Africa

Africa is the world's second largest and second most populous continent, after Asia. At about 30.2 million km² including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of the Earth's total surface area and 20.4% of the total land area...

, ready to engage when hostilities commenced. He planned to bombard the embarkation ports of Bône

Bone

Bones are rigid organs that constitute part of the endoskeleton of vertebrates. They support, and protect the various organs of the body, produce red and white blood cells and store minerals. Bone tissue is a type of dense connective tissue...

and Philippeville in French Algeria

French Algeria

French Algeria lasted from 1830 to 1962, under a variety of governmental systems. From 1848 until independence, the whole Mediterranean region of Algeria was administered as an integral part of France, much like Corsica and Réunion are to this day. The vast arid interior of Algeria, like the rest...

. Goeben was heading for Philippeville, while Breslau was detached to deal with Bône. At 18:00 on 3 August, while still sailing west, he received word that Germany had declared war on France. Then, early on 4 August, Souchon received orders from Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz

Alfred von Tirpitz

Alfred von Tirpitz was a German Admiral, Secretary of State of the German Imperial Naval Office, the powerful administrative branch of the German Imperial Navy from 1897 until 1916. Prussia never had a major navy, nor did the other German states before the German Empire was formed in 1871...

reading: "Alliance with government of

Imperial Government of the Ottoman Empire

The Imperial Government of the Ottoman Empire was the government structure added to the Ottoman governing structure during the Second Constitutional Era. The Committee of Union and Progress was in power between 1908 and 1918...

CUP

Committee of Union and Progress

The Committee of Union and Progress began as a secret society established as the "Committee of Ottoman Union" in 1889 by the medical students İbrahim Temo, Abdullah Cevdet, İshak Sükuti and Ali Hüseyinzade...

concluded August 3. Proceed at once to İstanbul

Istanbul

Istanbul , historically known as Byzantium and Constantinople , is the largest city of Turkey. Istanbul metropolitan province had 13.26 million people living in it as of December, 2010, which is 18% of Turkey's population and the 3rd largest metropolitan area in Europe after London and...

." So close to his targets, Souchon pushed on and his ships, flying the Russia

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

n flag as he approached, carried out their bombardment at dawn before breaking off and heading back to Messina for more coal.

Under a pre-war agreement with Britain, France was able to concentrate her entire fleet in the Mediterranean, leaving the Royal Navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

to ensure the security of France′s Atlantic coast. Three squadrons of the French fleet were covering the transports. However, assuming that Goeben would continue west, the French commander—Admiral de Lapeyrère

Augustin Boué de Lapeyrère

Augustin Manuel Hubert Gaston Boué de Lapeyrère was a French admiral during World War I. He was a strong proponent of naval reform, and is comparable to Admiral Jackie Fisher of the British Royal Navy.-Biography:...

—sent no ships to make contact and so Souchon was able to slip away to the east.

In Souchon′s path were the two British battlecruisers, Indomitable and Indefatigable, which made contact at 09:30 on 4 August, passing the German ships in the opposite direction. Unlike France, Britain was not yet at war with Germany (the declaration would not be made until later that day, following the start of the German invasion of neutral Belgium

Belgium

Belgium , officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a federal state in Western Europe. It is a founding member of the European Union and hosts the EU's headquarters, and those of several other major international organisations such as NATO.Belgium is also a member of, or affiliated to, many...

), and so the British ships commenced shadowing Goeben and Breslau. Milne reported the contact and position, but neglected to inform the Admiralty that the German ships were heading east. Churchill therefore still expected them to threaten the French transports, and he authorized Milne to engage the German ships if they attacked. However, a meeting of the British Cabinet decided that hostilities could not start before a declaration of war, and at 14:00 Churchill was obliged to cancel his authorization to attack.

Pursuit

Steam

Steam is the technical term for water vapor, the gaseous phase of water, which is formed when water boils. In common language it is often used to refer to the visible mist of water droplets formed as this water vapor condenses in the presence of cooler air...

. Fortunately for Souchon, both British battlecruisers were also suffering from problems with their boilers and were unable to keep Goeben′s pace. The light cruiser maintained contact, while Indomitable and Indefatigable fell behind. In fog and fading light, Dublin lost contact off Cape San Vito on the north coast of Sicily

Sicily

Sicily is a region of Italy, and is the largest island in the Mediterranean Sea. Along with the surrounding minor islands, it constitutes an autonomous region of Italy, the Regione Autonoma Siciliana Sicily has a rich and unique culture, especially with regard to the arts, music, literature,...

at 19:37. Goeben and Breslau returned to Messina the following morning, by which time Britain and Germany were at war.

The Admiralty ordered Milne to respect Italian neutrality and stay outside a 6 mi (5.2 nmi; 9.7 km) limit from the Italian coast—which precluded entrance into the passage of the Straits of Messina. Consequently, Milne posted guards on the exits from the Straits. Still expecting Souchon to head for the transports and the Atlantic, he placed two battlecruisers—Inflexible and Indefatigable—to cover the northern exit (which gave access to the western Mediterranean), while the southern exit of the Straits was covered by a single light cruiser, . Milne sent Indomitable west to coal at Bizerte

Bizerte

Bizerte or Benzert , is the capital city of Bizerte Governorate in Tunisia and the northernmost city in Africa. It has a population of 230,879 .-History:...

, instead of south to Malta.

For Souchon, Messina was no haven. Italian authorities insisted he depart within 24 hours and delayed supplying coal. Provisioning his ships required ripping up the decks of German merchant steamers in harbour and manually shovelling their coal into his bunkers. By the evening of 6 August, and despite the help of 400 volunteers from the merchantmen, he had only taken on 1500 ST (1,360.8 t) which was insufficient to reach Istanbul. Further messages from Tirpitz made his predicament even more dire. He was informed that Austria would provide no naval aid in the Mediterranean and that Ottoman Empire was still neutral and therefore he should no longer make for Istanbul. Faced with the alternative of seeking refuge at Pola, and probably remaining trapped for the rest of the war, Souchon chose to head for Istanbul anyway, his purpose being "to force the Ottoman Empire, even against their will, to spread the war to the Black Sea

Black Sea

The Black Sea is bounded by Europe, Anatolia and the Caucasus and is ultimately connected to the Atlantic Ocean via the Mediterranean and the Aegean seas and various straits. The Bosphorus strait connects it to the Sea of Marmara, and the strait of the Dardanelles connects that sea to the Aegean...

against their ancient enemy, Russia."

Milne was instructed on 5 August to continue watching the Adriatic for signs of the Austrian fleet and to prevent the German ships joining them. He chose to keep his battlecruisers in the west, dispatching Dublin to join Troubridge′s cruiser squadron in the Adriatic, which he believed would be able to intercept Goeben and Breslau. Troubridge was instructed 'not to get seriously engaged with superior forces', once again intended as a warning against engaging the Austrian fleet. When Goeben and Breslau emerged into the eastern Mediterranean on 6 August, they were met by Gloucester which, being out-gunned, began to shadow the German ships.

Troubridge′s squadron comprised the armoured cruisers , , , and eight destroyers armed with torpedoes. The cruisers had 9.2 in (233.7 mm) guns versus the 11 in (279.4 mm) guns of Goeben and had armour a maximum of 6 in (15.2 cm) thick compared to the battlecruiser′s 11 in (27.9 cm) armour belt. This meant that Troubridge′s squadron was not only out-ranged and vulnerable to Goeben′s powerful guns, but it was unlikely his cruiser′s guns could seriously damage the German ship at all—even at short range. In addition, the British ships were several knots slower than Goeben, despite her damaged boilers, meaning that she could dictate the range of the battle if she spotted the British squadron in advance. Consequently, Troubridge considered his only chance was to locate and engage Goeben in favourable light, at dawn, with Goeben east of his ships and ideally launch a torpedo attack with his destroyers, however at least five of the destroyers did not have enough coal to keep up with the cruisers steaming at full speed. By 04:00 on 7 August, Troubridge realised he would not be able to intercept the German ships before daylight and after some deliberation he signalled Milne with his intentions to break off the chase, mindful of Churchill′s ambiguous order to avoid engaging a "superior force". No reply was received until 10:00, by which time he had withdrawn to Zante to refuel.

Escape

Collier (ship type)

Collier is a historical term used to describe a bulk cargo ship designed to carry coal, especially for naval use by coal-fired warships. In the late 18th century a number of wooden-hulled sailing colliers gained fame after being adapted for use in voyages of exploration in the South Pacific, for...

waiting off the coast of Greece

Greece

Greece , officially the Hellenic Republic , and historically Hellas or the Republic of Greece in English, is a country in southeastern Europe....

and needed to shake his pursuer before he could rendezvous. Gloucester finally engaged Breslau, hoping this would compel Goeben to drop back and protect the light cruiser. According to Souchon, Breslau was hit, but no damage was done. The action then broke off without further hits being scored. Finally, Milne ordered Gloucester to cease pursuit at Cape Matapan

Cape Matapan

Cape Tainaron , also known as Cape Matapan , is situated at the end of the Mani, Laconia, Greece. Cape Matapan is the southernmost point of mainland Greece. It separates the Messenian Gulf in the west from the Laconian Gulf in the east.-History:...

.

Shortly after midnight on 8 August, Milne took his three battlecruisers and the light cruiser east. At 14:00, he received an incorrect signal from the Admiralty stating that Britain was at war with Austria—war would not be declared until 12 August and the order was countermanded four hours later, but Milne chose to guard the Adriatic rather than seek Goeben. Finally on 9 August, Milne was given clear orders to "chase Goeben which had passed Cape Matapan on the 7th steering north-east." Milne still did not believe that Souchon was heading for the Dardanelles, and so he resolved to guard the exit from the Aegean

Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea[p] is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea located between the southern Balkan and Anatolian peninsulas, i.e., between the mainlands of Greece and Turkey. In the north, it is connected to the Marmara Sea and Black Sea by the Dardanelles and Bosporus...

, unaware that Goeben did not intend to come out.

Souchon had replenished his coal off the Aegean island of Donoussa

Donoussa

Donousa is an island and a former community in the Cyclades, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Naxos and Lesser Cyclades, of which it is a municipal unit...

on 9 August and the German warships resumed their voyage to Constantinople. At 17:00 on 10 August, he reached the Dardanelles and awaited permission to pass through. Germany had for some time been courting the Committee of Union and Progress

Committee of Union and Progress

The Committee of Union and Progress began as a secret society established as the "Committee of Ottoman Union" in 1889 by the medical students İbrahim Temo, Abdullah Cevdet, İshak Sükuti and Ali Hüseyinzade...

of the imperial government

Second Constitutional Era (Ottoman Empire)

The Second Constitutional Era of the Ottoman Empire began shortly after Sultan Abdülhamid II restored the constitutional monarchy after the 1908 Young Turk Revolution. The period established many political groups...

, and they now used their influence to pressure the Turkish Minister of War, Enver Pasha, into granting the ship′s passage, an act that would outrage Russia which relied on the Dardanelles as its main all-season shipping route. In addition, the Germans managed to persuade Enver to order any pursuing British ships to be fired on. By the time Souchon received permission to enter the straits, his lookouts could see smoke on the horizon from approaching British ships.

Turkey was still a neutral country bound by treaty to prevent German ships passing the straits. To get around this difficulty it was agreed that the ships should become part of the Turkish navy. On 16 August, having reached Constantinople, Goeben and Breslau were transferred to the Turkish Navy in a small ceremony, becoming respectively the Yavuz Sultan Selim and the Midilli, though they retained their German crews with Souchon still in command. The initial reaction in Britain was one of satisfaction, that a threat had been removed from the Mediterranean. On 23 September, Souchon was appointed commander in chief of the Ottoman Navy.

Consequences

In August, Germany—still expecting a swift victory—was content for the Ottoman Empire to remain neutral. The mere presence of a powerful warship like Goeben in the Sea of MarmaraSea of Marmara

The Sea of Marmara , also known as the Sea of Marmora or the Marmara Sea, and in the context of classical antiquity as the Propontis , is the inland sea that connects the Black Sea to the Aegean Sea, thus separating Turkey's Asian and European parts. The Bosphorus strait connects it to the Black...

would be enough to occupy a British naval squadron guarding the Dardanelles. However, following German reverses at the First Battle of the Marne

First Battle of the Marne

The Battle of the Marne was a First World War battle fought between 5 and 12 September 1914. It resulted in an Allied victory against the German Army under Chief of Staff Helmuth von Moltke the Younger. The battle effectively ended the month long German offensive that opened the war and had...

in September, and with Russian successes against Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary , more formally known as the Kingdoms and Lands Represented in the Imperial Council and the Lands of the Holy Hungarian Crown of Saint Stephen, was a constitutional monarchic union between the crowns of the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary in...

, Germany began to regard the Ottoman Empire as a useful ally. Tensions began to escalate when Ottoman Empire closed the Dardanelles to all shipping on 27 September, blocking Russia's exit from the Black Sea

Black Sea

The Black Sea is bounded by Europe, Anatolia and the Caucasus and is ultimately connected to the Atlantic Ocean via the Mediterranean and the Aegean seas and various straits. The Bosphorus strait connects it to the Sea of Marmara, and the strait of the Dardanelles connects that sea to the Aegean...

—the Black Sea route accounted for over 90% of Russia's import and export traffic.

Germany′s gift of the two modern warships had an enormous positive impact with the Turkish population. At the outbreak of the war, Churchill had caused outrage when he "requisitioned" two almost completed Turkish battleship

Battleship

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of heavy caliber guns. Battleships were larger, better armed and armored than cruisers and destroyers. As the largest armed ships in a fleet, battleships were used to attain command of the sea and represented the apex of a...

s in British shipyards, the Sultan Osman I and the Reshadieh, that had been financed by public subscription at a cost of £6,000,000. Turkey was offered compensation of £1,000 per day for so long as the war might last, provided she remained neutral. (These ships were commissioned into the Royal Navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

as and respectively.) The Turks had been neutral, though the navy had been pro-British (having purchased 40 warships from British shipyards) while the army was in favour of Germany, so the two incidents helped resolve the deadlock and the Ottoman Empire would join the Central Powers

Central Powers

The Central Powers were one of the two warring factions in World War I , composed of the German Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulgaria...

.

Sevastopol

Continued diplomacy

Diplomacy

Diplomacy is the art and practice of conducting negotiations between representatives of groups or states...

from France and Russia attempted to keep the Ottoman Empire out of the war, but Germany was agitating for a commitment. In the aftermath of Souchon′s daring dash to Constantinople, on 15 August 1914 the Ottomans canceled their maritime agreement with Britain and the Royal Navy mission under Admiral Limpus left by 15 September.

Finally, on 29 October, the point of no return was reached when Admiral Souchon took Goeben, Breslau and a squadron of Turkish warships into the Black Sea and raided the Russian ports of Novorossiysk

Novorossiysk

Novorossiysk is a city in Krasnodar Krai, Russia. It is the country's main port on the Black Sea and the leading Russian port for importing grain. It is one of the few cities honored with the title of the Hero City. Population: -History:...

, Odessa

Odessa

Odessa or Odesa is the administrative center of the Odessa Oblast located in southern Ukraine. The city is a major seaport located on the northwest shore of the Black Sea and the fourth largest city in Ukraine with a population of 1,029,000 .The predecessor of Odessa, a small Tatar settlement,...

and Sevastopol

Sevastopol

Sevastopol is a city on rights of administrative division of Ukraine, located on the Black Sea coast of the Crimea peninsula. It has a population of 342,451 . Sevastopol is the second largest port in Ukraine, after the Port of Odessa....

. For 25 minutes, Goeben′s main and secondary guns fired on Sevastopol. In reply, two 12 in (304.8 mm) shells fired from a Russian fort at an extreme range of over 10 mi (8.7 nmi; 16.1 km) blew a pair of holes in the ship's aft smoke-stack killing 14 men. On the return journey, Goeben hit the Russian destroyer Leiteneat Pushchin with two 5.9 in (150 mm) shells and sank the Russian minelayer Prut which had 700 mines on board in order to lay a minefield across the battle-cruiser's homeward route.

The attack on Novorossiysk was also an outstanding success, with 14 steamers in the harbour sunk by Breslau′s guns while 40 oil tanks were set on fire, liberating streams of burning petroleum

Petroleum

Petroleum or crude oil is a naturally occurring, flammable liquid consisting of a complex mixture of hydrocarbons of various molecular weights and other liquid organic compounds, that are found in geologic formations beneath the Earth's surface. Petroleum is recovered mostly through oil drilling...

that engulfed whole streets. Russia declared war on the Ottoman Empire on 2 November and France and Britain followed on 5 November. The first land battles were expected in the Caucasus

Caucasus

The Caucasus, also Caucas or Caucasia , is a geopolitical region at the border of Europe and Asia, and situated between the Black and the Caspian sea...

, and transport steamers started carrying Turkish troops eastwards along the Anatolian coast to Samsun

Samsun

Samsun is a city of about half a million people on the north coast of Turkey. It is the provincial capital of Samsun Province and a major Black Sea port.-Name:...

and Trebizond. The Russian Black Sea Fleet sank three of these ships so when another convoy sailed on 16 November; Breslau accompanied them as an escort while Goeben—which had located and severed the Sevastopol-Odessa submarine cable on the night 10/11 November—cruised in the middle of the Black Sea.

Crimean Encounter

On 18 November, in a dense bank of fog, Breslau joined her consort and the two German ships were almost on top of the Russian Fleet, a chance gust of wind momentarily stirred the fog, and suddenly the antagonists were in each other′s view at less than 4000 yd (3,657.6 m) range. Instantly, the guns of both sides opened fire. Goeben—with Breslau sheltering behind her—found herself sailing past the entire line of the Black Sea Fleet. A 12 in (304.8 mm) shell from a Russian battleship tore through the armour of Goeben′s 5.9 in (150 mm) casement, killing the six-man gun crew and detonating the ammunition. Only swift flooding of a magazine prevented a bigger explosion, but the Russian flagship Evstafi was hit four times by Goeben, killing 33 men and the Russian battleship Rostislav were badly damaged. The Black Sea Fleet quickly hid itself again in the mist and continued to threaten the Turkish Black Sea coast for the rest of the war.

Troop transports

In November and December, Breslau and the light cruiser Hamidie undertook frequent troopship escorts to the Caucasus, but the Goeben consumed too much coal for this kind of work, although on 10 December she fired fifteen 11 in (279.4 mm) shells at the Russian shore defenses of Batumi

Batumi

Batumi is a seaside city on the Black Sea coast and capital of Adjara, an autonomous republic in southwest Georgia. Sometimes considered Georgia's second capital, with a population of 121,806 , Batumi serves as an important port and a commercial center. It is situated in a subtropical zone, rich in...

. Intense Russian wireless activity

Traffic analysis

Traffic analysis is the process of intercepting and examining messages in order to deduce information from patterns in communication. It can be performed even when the messages are encrypted and cannot be decrypted. In general, the greater the number of messages observed, or even intercepted and...

on 23 December made it evident that the Black Sea Fleet had left the harbour. Goeben and Breslau were sent out to provide escort for some transports and as night fell over a rough, wind-lashed sea the German light cruiser was detached to reconnoitre to the NE. The Russian radios were silent now, and the whereabouts of the Black Sea Fleet was problematical. At 04:00, Breslau encountered the Russian fleet. Her searchlight illuminated a transport, which was sunk with a single salvo, and then the forbidding silhouette of a Russian battleship was caught in its beam. A second salvo from Breslau straddled the massive vessel before the light cruiser sought refuge in the darkness.

While returning from another troop transport on 26 December, Goeben was mined off the Bosphorus. The first mine exploded to the starboard beneath the conning tower, which immediately caused a 30º list to port. Two minutes later, the ship hit a second mine, this time off the port wing barbette

Barbette

A barbette is a protective circular armour feature around a cannon or heavy artillery gun. The name comes from the French phrase en barbette referring to the practice of firing a field gun over a parapet rather than through an opening . The former gives better angles of fire but less protection...

, where 600 ST (544.3 t) of water disabled No. 3 turret and flooded the ship. The stricken battlecruiser was barely able to reach Stenia Creek. The damage was serious and kept Goeben in port for three months, apart from two brief sorties intended to deter Russian battleships that were apparently approaching İstanbul

Istanbul

Istanbul , historically known as Byzantium and Constantinople , is the largest city of Turkey. Istanbul metropolitan province had 13.26 million people living in it as of December, 2010, which is 18% of Turkey's population and the 3rd largest metropolitan area in Europe after London and...

.

Second Encounter

On 3 April, Goeben left the Bosphorus in company with Breslau to cover the withdrawal of the Turkish cruisers Hamidie and Medjidie, which had been sent to bombard Nikolayev. Medjidie struck a mine and sank, so this attack had to be abandoned, but the two German ships appeared off Sevastopol and tempted out the Black Sea Fleet. Although six Russian battleships—supported by two cruisers and five destroyers—were bearing down upon them, Goeben and Breslau sank two cargo steamers and then deliberately loitered about to draw on their pursuers. Hamidie had to be given time to return to the Bosphorus with survivors from the Medjidie.

When the range had closed to about 15000 yd (13,716 m), Breslau slipped between her sister and the Russian squadron and laid a dense smoke screen. Under its cover, the German ships turned away, but kept their speed down so as not to discourage pursuit. Eagerly, the Russians chased after them, the ponderous battleships at their maximum 25 kn (30.4 mph; 49 km/h). At one point, Breslau fell back far enough to draw fire from the Russian line, but she spurted out of range again before any hits were sustained. As darkness fell, Goeben and Breslau began to pull away from their pursuers, for Hamidie had radioed that she was almost home, but in the darkness Russian destroyers closed on Goeben, stalking her in her smoke. But their wireless chatter betrayed them and Goeben′s four 60 in (1,524 mm) stern searchlights stabbed back down her wake, illuminating the sinister shapes of five destroyers only 200 yd (182.9 m) astern.

Breslau′s guns crashed out, and the first destroyer burst into flames, mortally hit. The second in line suffered a similar fate, the remainder turned tail and fled. None of their torpedo

Torpedo

The modern torpedo is a self-propelled missile weapon with an explosive warhead, launched above or below the water surface, propelled underwater towards a target, and designed to detonate either on contact with it or in proximity to it.The term torpedo was originally employed for...

es had found a mark, and at noon the following day Goeben and Breslau were once more off the Bosphorus.

With the Ottoman Empire at war, a new theatre was opened, the Middle Eastern theatre

Middle Eastern theatre of World War I

The Middle Eastern theatre of World War I was the scene of action between 29 October 1914, and 30 October 1918. The combatants were the Ottoman Empire, with some assistance from the other Central Powers, and primarily the British and the Russians among the Allies of World War I...

, with main fronts of Gallipoli

Battle of Gallipoli

The Gallipoli Campaign, also known as the Dardanelles Campaign or the Battle of Gallipoli, took place at the peninsula of Gallipoli in the Ottoman Empire between 25 April 1915 and 9 January 1916, during the First World War...

, the Sinai and Palestine

Sinai and Palestine Campaign

The Sinai and Palestine Campaigns took place in the Middle Eastern Theatre of World War I. A series of battles were fought between British Empire, German Empire and Ottoman Empire forces from 26 January 1915 to 31 October 1918, when the Armistice of Mudros was signed between the Ottoman Empire and...

, Mesopotamia

Mesopotamian Campaign

The Mesopotamian campaign was a campaign in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I fought between the Allies represented by the British Empire, mostly troops from the Indian Empire, and the Central Powers, mostly of the Ottoman Empire.- Background :...

, and in Caucasus

Caucasus Campaign

The Caucasus Campaign comprised armed conflicts between the Ottoman Empire and the Russian Empire, later including Azerbaijan, Armenia, Central Caspian Dictatorship and the UK as part of the Middle Eastern theatre or alternatively named as part of the Caucasus Campaign during World War I...

. The course of the war in the Balkans

Balkans

The Balkans is a geopolitical and cultural region of southeastern Europe...

was also influenced by the entry of the Ottoman Empire on the side of the Central Powers

Central Powers

The Central Powers were one of the two warring factions in World War I , composed of the German Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulgaria...

.

Royal Navy

While the consequences of the Royal Navy′s failure to intercept Goeben and Breslau had not been immediately apparent, the humiliation of the "defeat" resulted in Admirals de Lapeyrère, Milne and Troubridge being censured. Milne was recalled from the Mediterranean and did not hold another command until retirement at his own request in 1919, his planned assumption of the Nore command having been cancelled in 1916 due to "other exigencies". The Admiralty repeatedly stated that Milne had been exonerated of all blame. For his failure to engage Goeben with his cruiserCruiser

A cruiser is a type of warship. The term has been in use for several hundreds of years, and has had different meanings throughout this period...

s, Troubridge was court-martial

Court-martial

A court-martial is a military court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of members of the armed forces subject to military law, and, if the defendant is found guilty, to decide upon punishment.Most militaries maintain a court-martial system to try cases in which a breach of...

led in November on the charge that "he did forbear to chase His Imperial German Majesty′s ship Goeben, being an enemy then flying." The charge was not proved on the grounds that he was under orders not to engage a "superior force". He commanded the naval forces off the Dardanelles before being given command of a force on the Danube

Danube

The Danube is a river in the Central Europe and the Europe's second longest river after the Volga. It is classified as an international waterway....

in 1915 against the Austro-Hungarians.

Long-term consequences

Although not a widely known historical event now, the escape of Goeben to Constantinople ultimately precipitated some of the most dramatic events of the 20th century.General Ludendorff stated in his memoirs that he believed the entry of the Turks into the war allowed the outnumbered Central powers to fight on for two years longer than they would have been able on their own. The war was extended to the Middle East

Middle Eastern theatre of World War I

The Middle Eastern theatre of World War I was the scene of action between 29 October 1914, and 30 October 1918. The combatants were the Ottoman Empire, with some assistance from the other Central Powers, and primarily the British and the Russians among the Allies of World War I...

with main fronts of Gallipoli

Battle of Gallipoli

The Gallipoli Campaign, also known as the Dardanelles Campaign or the Battle of Gallipoli, took place at the peninsula of Gallipoli in the Ottoman Empire between 25 April 1915 and 9 January 1916, during the First World War...

, the Sinai and Palestine

Sinai and Palestine Campaign

The Sinai and Palestine Campaigns took place in the Middle Eastern Theatre of World War I. A series of battles were fought between British Empire, German Empire and Ottoman Empire forces from 26 January 1915 to 31 October 1918, when the Armistice of Mudros was signed between the Ottoman Empire and...

, Mesopotamia

Mesopotamian Campaign

The Mesopotamian campaign was a campaign in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I fought between the Allies represented by the British Empire, mostly troops from the Indian Empire, and the Central Powers, mostly of the Ottoman Empire.- Background :...

, and in Caucasus

Caucasus Campaign

The Caucasus Campaign comprised armed conflicts between the Ottoman Empire and the Russian Empire, later including Azerbaijan, Armenia, Central Caspian Dictatorship and the UK as part of the Middle Eastern theatre or alternatively named as part of the Caucasus Campaign during World War I...

. The course of the war in the Balkans

Balkans

The Balkans is a geopolitical and cultural region of southeastern Europe...

was also influenced by the entry of the Ottoman Empire on the side of the Central Powers

Central Powers

The Central Powers were one of the two warring factions in World War I , composed of the German Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulgaria...

. Had the war ended in 1916, that would have meant that some of the bloodiest engagements, such as the Battle of the Somme, would have been avoided. The United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

might not have been drawn from its policy of isolation to intervene in a foreign war.

In allying with the Central Powers, the Turks also shared their fate in ultimate defeat. This gave the victorious allies the opportunity to carve up the collapsed Ottoman Empire to suit their political whims. Many new nations were created including Palestine, Syria, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia and Iraq, and the idea of a Jewish state in Israel was considered for the first time.

Also, the closure of Russia′s only ice-free trade route through the Dardanelles effectively strangled the Russian economy. Unable to export grain nor import munitions, the Russian army was isolated from her allies and slowly began to collapse. Combined with the German decision to release Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin was a Russian Marxist revolutionary and communist politician who led the October Revolution of 1917. As leader of the Bolsheviks, he headed the Soviet state during its initial years , as it fought to establish control of Russia in the Russian Civil War and worked to create a...

in 1917, the sealing off of the Black Sea was one of the critical contributors to the "revolutionary situation" in Russia which would explode into the October Revolution

October Revolution

The October Revolution , also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution , Red October, the October Uprising or the Bolshevik Revolution, was a political revolution and a part of the Russian Revolution of 1917...

.

In fiction

The alternate history short story "Tradition", written by Elizabeth MoonElizabeth Moon

Elizabeth Moon is an American science fiction and fantasy author. Her novel The Speed of Dark won the 2003 Nebula Award.-Biography:...

, imagines Admiral Christopher Cradock

Christopher Cradock

Rear-Admiral Sir Christopher "Kit" George Francis Maurice Cradock KCVO CB was a British officer of the Royal Navy. He was born at Hartforth, Richmond, North Yorkshire...

in place of Admiral Troubridge as commander of the cruiser and destroyer force to the east of the Straits of Messina; in the story, Cradock ignores Admiral Milne′s instructions to guard the Adriatic Sea

Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkan peninsula, and the system of the Apennine Mountains from that of the Dinaric Alps and adjacent ranges...

and instead intercepts the Goeben and Breslau north of Crete

Crete

Crete is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, and one of the thirteen administrative regions of Greece. It forms a significant part of the economy and cultural heritage of Greece while retaining its own local cultural traits...

. In the ensuing battle, his fleet loses two of the four armoured cruisers and six of his eight destroyers, but manages to destroy both German ships before they reach their goal of Istanbul. In reality, Cradock was not present in the Mediterranean, but died a few weeks later at the Battle of Coronel

Battle of Coronel

The First World War naval Battle of Coronel took place on 1 November 1914 off the coast of central Chile near the city of Coronel. German Kaiserliche Marine forces led by Vice-Admiral Graf Maximilian von Spee met and defeated a Royal Navy squadron commanded by Rear-Admiral Sir Christopher...

after challenging a larger German force, a decision made in part because he wanted to avoid Troubridge's ignominy in allowing Goeben and Breslau to escape.