Robert Lawson (architect)

Encyclopedia

New Zealand

New Zealand is an island country in the south-western Pacific Ocean comprising two main landmasses and numerous smaller islands. The country is situated some east of Australia across the Tasman Sea, and roughly south of the Pacific island nations of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Tonga...

's pre-eminent 19th century architect

Architecture

Architecture is both the process and product of planning, designing and construction. Architectural works, in the material form of buildings, are often perceived as cultural and political symbols and as works of art...

s. It has been said he did more than any other designer to shape the face of the Victorian era

Victorian era

The Victorian era of British history was the period of Queen Victoria's reign from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. It was a long period of peace, prosperity, refined sensibilities and national self-confidence...

architecture of the city of Dunedin

Dunedin

Dunedin is the second-largest city in the South Island of New Zealand, and the principal city of the Otago Region. It is considered to be one of the four main urban centres of New Zealand for historic, cultural, and geographic reasons. Dunedin was the largest city by territorial land area until...

. He is the architect of over forty churches, including First Church for which he is best remembered, but also other buildings, such as Larnach Castle

Larnach Castle

Larnach Castle , is an imposing mansion on the ridge of the Otago Peninsula within the limits of the city of Dunedin, New Zealand, close to the small settlement of Pukehiki...

, a country house, with which he is also associated.

Born at Newburgh

Newburgh, Fife

Newburgh is a royal burgh of Fife, Scotland having a population of 2040 . Newburgh has grown little since 1901 when the population was counted at 1904 persons....

, in Fife

Fife

Fife is a council area and former county of Scotland. It is situated between the Firth of Tay and the Firth of Forth, with inland boundaries to Perth and Kinross and Clackmannanshire...

, Scotland

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

, he emigrated in 1854 to Australia

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

and then in 1862 to New Zealand. He died aged 69 in Canterbury

Canterbury, New Zealand

The New Zealand region of Canterbury is mainly composed of the Canterbury Plains and the surrounding mountains. Its main city, Christchurch, hosts the main office of the Christchurch City Council, the Canterbury Regional Council - called Environment Canterbury - and the University of Canterbury.-...

, New Zealand

New Zealand

New Zealand is an island country in the south-western Pacific Ocean comprising two main landmasses and numerous smaller islands. The country is situated some east of Australia across the Tasman Sea, and roughly south of the Pacific island nations of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Tonga...

. Lawson is acclaimed for his work in both the Gothic revival and classical

Classical architecture

Classical architecture is a mode of architecture employing vocabulary derived in part from the Greek and Roman architecture of classical antiquity, enriched by classicizing architectural practice in Europe since the Renaissance...

styles of architecture. He was prolific, and while isolated buildings remain in Scotland and Australia, it is in the Dunedin area that most surviving examples can now be found.

Today he is held in high esteem in his adopted country. However, at the time of his death his reputation and architectural skills were still held in contempt by many following the partial collapse of his Seacliff Lunatic Asylum

Seacliff Lunatic Asylum

Seacliff Lunatic Asylum was a psychiatric hospital in Seacliff, New Zealand. When built in the late 19th century, it was the largest building in the country, noted for its scale and extravagant architecture...

, at the time New Zealand's largest building. In 1900, shortly before his death, he returned to New Zealand from a self-imposed, ten-year exile to re-establish his name, but his sudden demise prevented a full rehabilitation of his reputation. The great plaudits denied him in his lifetime were not to come until nearly a century after his death, when the glories of Victorian architecture began again to be recognised and appreciated.

Early life

Lawson was the fourth child of James Lawson, a carpenterCarpenter

A carpenter is a skilled craftsperson who works with timber to construct, install and maintain buildings, furniture, and other objects. The work, known as carpentry, may involve manual labor and work outdoors....

, and his wife, Margaret. The young Lawson was educated at the local parish

Parish

A parish is a territorial unit historically under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of one parish priest, who might be assisted in his pastoral duties by a curate or curates - also priests but not the parish priest - from a more or less central parish church with its associated organization...

school. He then studied architecture

Architecture

Architecture is both the process and product of planning, designing and construction. Architectural works, in the material form of buildings, are often perceived as cultural and political symbols and as works of art...

, first in Perth

Perth, Scotland

Perth is a town and former city and royal burgh in central Scotland. Located on the banks of the River Tay, it is the administrative centre of Perth and Kinross council area and the historic county town of Perthshire...

(Scotland) and later in Edinburgh

Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland, the second largest city in Scotland, and the eighth most populous in the United Kingdom. The City of Edinburgh Council governs one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas. The council area includes urban Edinburgh and a rural area...

under James Gillespie Graham

James Gillespie Graham

James Gillespie Graham was a Scottish architect, born in Dunblane. He is most notable for his work in the Scottish baronial style, as at Ayton Castle, and he worked in the Gothic Revival style, in which he was heavily influenced by the work of Augustus Pugin...

. Aged 21, he emigrated first to Melbourne

Melbourne

Melbourne is the capital and most populous city in the state of Victoria, and the second most populous city in Australia. The Melbourne City Centre is the hub of the greater metropolitan area and the Census statistical division—of which "Melbourne" is the common name. As of June 2009, the greater...

on 15 July 1854, on the ship Tongataboo. Like other new arrivals in Australia, he tried many new occupations, including gold

Gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au and an atomic number of 79. Gold is a dense, soft, shiny, malleable and ductile metal. Pure gold has a bright yellow color and luster traditionally considered attractive, which it maintains without oxidizing in air or water. Chemically, gold is a...

mining and journalism

Journalism

Journalism is the practice of investigation and reporting of events, issues and trends to a broad audience in a timely fashion. Though there are many variations of journalism, the ideal is to inform the intended audience. Along with covering organizations and institutions such as government and...

. During this period he occasionally turned his hand to architecture. In Steiglitz

Steiglitz, Victoria

Steiglitz is a small town in Victoria, west of the state capital, Melbourne, Australia, in the Brisbane Ranges. In the early 1850s gold was found near the town, and as a consequence it grew. Following the decline of the Australian gold rushes in the late 1870s the town declined. The last gold mine...

he designed the Free Church school

School

A school is an institution designed for the teaching of students under the direction of teachers. Most countries have systems of formal education, which is commonly compulsory. In these systems, students progress through a series of schools...

and in 1858 a Catholic

Catholic

The word catholic comes from the Greek phrase , meaning "on the whole," "according to the whole" or "in general", and is a combination of the Greek words meaning "about" and meaning "whole"...

school. As Lawson came to realise the low probability of success in the gold rush and the precariousness of a career in journalism, he decided to return full time to his first chosen career and found a position as an architect in Melbourne

Melbourne

Melbourne is the capital and most populous city in the state of Victoria, and the second most populous city in Australia. The Melbourne City Centre is the hub of the greater metropolitan area and the Census statistical division—of which "Melbourne" is the common name. As of June 2009, the greater...

.

In 1861, the first Otago gold rush brought an influx of people to southern New Zealand, including a new generation. In January 1862, a competition was held to design First Church — a cathedral

Cathedral

A cathedral is a Christian church that contains the seat of a bishop...

-like place of worship

Worship

Worship is an act of religious devotion usually directed towards a deity. The word is derived from the Old English worthscipe, meaning worthiness or worth-ship — to give, at its simplest, worth to something, for example, Christian worship.Evelyn Underhill defines worship thus: "The absolute...

to serve as the principal Presbyterian church in the rapidly expanding settlement. Dunedin became New Zealand's commercial capital in the 1870s and 80s.

Pseudonym

A pseudonym is a name that a person assumes for a particular purpose and that differs from his or her original orthonym...

"Presbyter". If this pseudonym was designed to catch the eye of the Presbyterian judges, it was well chosen: his design was successful. Thus Lawson was able in 1862 to move to Dunedin and open an architectural practice. First Church was finally completed in 1874. During the period of construction Lawson was commissioned to design other churches, public buildings, and houses in the vicinity.

In his work on First Church, Lawson had met Jessie Sinclair Hepburn, whose father George Hepburn was the second session clerk of the building. The couple married in November 1864 and subsequently had three daughters and a son. Throughout his life Lawson remained a devout Presbyterian, becoming an elder and session clerk of First Church like his father-in-law. He was also closely involved in the Sunday school

Sunday school

Sunday school is the generic name for many different types of religious education pursued on Sundays by various denominations.-England:The first Sunday school may have been opened in 1751 in St. Mary's Church, Nottingham. Another early start was made by Hannah Ball, a native of High Wycombe in...

movement.

Although much of Lawson's early work has since been either demolished or heavily altered, surviving plans and photographs from the period suggest that the buildings he was working on at this time included a variety of styles. Indeed, Lawson designed principally in both the classical

Classical architecture

Classical architecture is a mode of architecture employing vocabulary derived in part from the Greek and Roman architecture of classical antiquity, enriched by classicizing architectural practice in Europe since the Renaissance...

and Gothic styles simultaneously throughout his career. His style and manner of architecture can best be explained through an examination of six of his designs, three Gothic and three in the classical style, and each an individual interpretation and use of their common designated style.

Works in the Gothic style

The British Protestant religions were at this period still heavily influenced by the Anglo-Catholic Oxford MovementOxford Movement

The Oxford Movement was a movement of High Church Anglicans, eventually developing into Anglo-Catholicism. The movement, whose members were often associated with the University of Oxford, argued for the reinstatement of lost Christian traditions of faith and their inclusion into Anglican liturgy...

, which had decreed Gothic as the only architectural style suited for Christian

Christian

A Christian is a person who adheres to Christianity, an Abrahamic, monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth as recorded in the Canonical gospels and the letters of the New Testament...

worship; Greek, Roman, and Italian renaissance architecture was viewed as "pagan" and inappropriate in the design of churches. Thus Lawson was never given opportunities such as Francis Petre

Francis Petre

Francis William "Frank" Petre was a prominent New Zealand-born architect based in Dunedin. He was an able exponent of the Gothic revival style, one of its best practitioners in New Zealand. He followed the Roman Church's initiative to build Catholic places of worship in Anglo-Saxon countries in...

enjoyed when the latter recreated great Italianate renaissance basilica

Basilica

The Latin word basilica , was originally used to describe a Roman public building, usually located in the forum of a Roman town. Public basilicas began to appear in Hellenistic cities in the 2nd century BC.The term was also applied to buildings used for religious purposes...

s such as the Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament in Christchurch

Christchurch

Christchurch is the largest city in the South Island of New Zealand, and the country's second-largest urban area after Auckland. It lies one third of the way down the South Island's east coast, just north of Banks Peninsula which itself, since 2006, lies within the formal limits of...

. Dunedin had in fact been founded, only thirteen years before Lawson's arrival, by the Free Church of Scotland

Free Church of Scotland (1843-1900)

The Free Church of Scotland is a Scottish denomination which was formed in 1843 by a large withdrawal from the established Church of Scotland in a schism known as the "Disruption of 1843"...

, a denomination not known for its love of ornament and decoration, and certainly not the architecture of the more Catholic countries.

Lawson's work in Gothic design, like that of most other architects of this period, was clearly influenced by the style and philosophy of Augustus Pugin

Augustus Pugin

Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin was an English architect, designer, and theorist of design, now best remembered for his work in the Gothic Revival style, particularly churches and the Palace of Westminster. Pugin was the father of E. W...

. However, he adapted the style for the form of congregational worship employed by the Presbyterian denomination. The lack of ritual and religious procession

Procession

A procession is an organized body of people advancing in a formal or ceremonial manner.-Procession elements:...

s rendered unnecessary a large chancel

Chancel

In church architecture, the chancel is the space around the altar in the sanctuary at the liturgical east end of a traditional Christian church building...

; hence in Lawson's version of the Gothic, the chancel

Chancel

In church architecture, the chancel is the space around the altar in the sanctuary at the liturgical east end of a traditional Christian church building...

and transept

Transept

For the periodical go to The Transept.A transept is a transverse section, of any building, which lies across the main body of the building. In Christian churches, a transept is an area set crosswise to the nave in a cruciform building in Romanesque and Gothic Christian church architecture...

s (the areas which traditionally in Roman and Anglo-Catholic churches contained the Lady Chapel

Lady chapel

A Lady chapel, also called Mary chapel or Marian chapel, is a traditional English term for a chapel inside a cathedral, basilica, or large church dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary...

and other minor chapel

Chapel

A chapel is a building used by Christians as a place of fellowship and worship. It may be part of a larger structure or complex, such as a church, college, hospital, palace, prison or funeral home, located on board a military or commercial ship, or it may be an entirely free-standing building,...

s) are merely hinted at in the design. Thus at First Church the tower

Tower

A tower is a tall structure, usually taller than it is wide, often by a significant margin. Towers are distinguished from masts by their lack of guy-wires....

is above the entrance to the building rather than in its traditional place in the centre of the church at the axis of nave

Nave

In Romanesque and Gothic Christian abbey, cathedral basilica and church architecture, the nave is the central approach to the high altar, the main body of the church. "Nave" was probably suggested by the keel shape of its vaulting...

, chancel and transepts. In all, Lawson designed over forty churches in the Gothic style. Like Benjamin Mountfort's, some were constructed entirely of wood; however, the majority were in stone.

First Church, Dunedin 1862

Otago

Otago is a region of New Zealand in the south of the South Island. The region covers an area of approximately making it the country's second largest region. The population of Otago is...

Provincial Council decided to reduce Bell Hill, on which it was to stand, by some 12 metres (39.4 ft): the hill had proved a major impediment to transport in the rapidly expanding city.

The church is dominated by its multi-pinnacle

Pinnacle

A pinnacle is an architectural ornament originally forming the cap or crown of a buttress or small turret, but afterwards used on parapets at the corners of towers and in many other situations. The pinnacle looks like a small spire...

d tower crowned by a spire

Spire

A spire is a tapering conical or pyramidal structure on the top of a building, particularly a church tower. Etymologically, the word is derived from the Old English word spir, meaning a sprout, shoot, or stalk of grass....

rising to 54 metres (177.2 ft). The spire is unusual as it is pierced by two-storeyed gable

Gable

A gable is the generally triangular portion of a wall between the edges of a sloping roof. The shape of the gable and how it is detailed depends on the structural system being used and aesthetic concerns. Thus the type of roof enclosing the volume dictates the shape of the gable...

d windows on all sides, which give an illusion of even greater height. Such was Lawson's perfectionism that the top of the spire had to be dismantled and rebuilt when it failed to measure up to his standards. It can be seen from much of central Dunedin, and dominates the skyline of lower Moray Place

Moray Place, Dunedin

Moray Place is an octagonal street which surrounds the city centre of Dunedin, Otago, New Zealand. The street is intersected by Stuart Street , Princes Street and George Street...

.

The expense of the building, by the time of its completion the third to house the first Presbyterian congregation, was not without criticism. Some members of the Presbyterian synod felt the metropolitan church should not have been so privileged over the country districts where congregants had no purpose designed places of worship or only modest ones. The Reverend Dr Burns's championship of the project ensured it was carried through against such objections.

Externally First Church successfully replicates the effect, if on a smaller scale, of the late Norman

Norman architecture

About|Romanesque architecture, primarily English|other buildings in Normandy|Architecture of Normandy.File:Durham Cathedral. Nave by James Valentine c.1890.jpg|thumb|200px|The nave of Durham Cathedral demonstrates the characteristic round arched style, though use of shallow pointed arches above the...

cathedrals of England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

. The cathedral-like design and size can best be appreciated from the rear. There is an apse

Apse

In architecture, the apse is a semicircular recess covered with a hemispherical vault or semi-dome...

flanked by turret

Turret

In architecture, a turret is a small tower that projects vertically from the wall of a building such as a medieval castle. Turrets were used to provide a projecting defensive position allowing covering fire to the adjacent wall in the days of military fortification...

s, which are dwarfed by the massive gable containing the great rose window

Rose window

A Rose window is often used as a generic term applied to a circular window, but is especially used for those found in churches of the Gothic architectural style and being divided into segments by stone mullions and tracery...

. It is this large circular window which after the spire becomes the focal point of the rear elevations. The whole architectural essay appears here almost European. Inside, instead of the stone vaulted ceiling of a Norman cathedral, there are hammer beams supporting a ceiling of pitched wood and a stone pointed arch

Arch

An arch is a structure that spans a space and supports a load. Arches appeared as early as the 2nd millennium BC in Mesopotamian brick architecture and their systematic use started with the Ancient Romans who were the first to apply the technique to a wide range of structures.-Technical aspects:The...

acts as a simple proscenium

Proscenium

A proscenium theatre is a theatre space whose primary feature is a large frame or arch , which is located at or near the front of the stage...

to the central pulpit

Pulpit

Pulpit is a speakers' stand in a church. In many Christian churches, there are two speakers' stands at the front of the church. Typically, the one on the left is called the pulpit...

. Above this diffused light enters through a rose window

Rose window

A Rose window is often used as a generic term applied to a circular window, but is especially used for those found in churches of the Gothic architectural style and being divided into segments by stone mullions and tracery...

of stained glass. This is flanked by further lights on the lower level, while twin organ pipes emphasise the symmetry of the pulpit.

The building is constructed of Oamaru stone

Oamaru stone

Oamaru stone is a hard, compact limestone, quarried at Weston, near Oamaru in Otago, New Zealand.The stone is used for building purposes, especially where ornate moulding is required. The finished stonework has a creamy, sandy colour...

, set on foundations of basalt breccia

Breccia

Breccia is a rock composed of broken fragments of minerals or rock cemented together by a fine-grained matrix, that can be either similar to or different from the composition of the fragments....

from Port Chalmers

Port Chalmers

Port Chalmers is a suburb and the main port of the city of Dunedin, New Zealand, with a population of 3,000. Port Chalmers lies ten kilometres inside Otago Harbour, some 15 kilometres northeast from Dunedin's city centre....

, with details carved by Louis Godfrey, who also did much of the woodcarving in the interior. The use of "cathedral glass", coloured but unfigured glass pending the donation of a pictorial window for the rose window is characteristic of Otago's 19th century churches, where donors were relatively few reflecting the generally "low church" sentiments of the place. Similar examples can be found in Lawson's churches throughout Otago

Otago

Otago is a region of New Zealand in the south of the South Island. The region covers an area of approximately making it the country's second largest region. The population of Otago is...

. Notable among these are the former Wesleyan

Methodism

Methodism is a movement of Protestant Christianity represented by a number of denominations and organizations, claiming a total of approximately seventy million adherents worldwide. The movement traces its roots to John Wesley's evangelistic revival movement within Anglicanism. His younger brother...

Church in Stuart Street, Dunedin (now used as a home for the Fortune Theatre

Fortune Theatre (New Zealand)

New Zealand's Fortune Theatre is located on the corner of Moray Place and Upper Stuart Street, in the heart of the southern city of Dunedin. The theatre lays claim to being the world's southernmost professional theatre company and is the sole professional theatre group in Dunedin...

), the spired Knox Church

Knox Church, Dunedin

Knox Church is a notable building in Dunedin, New Zealand. It houses the city's second Presbyterian congregation and is the city's largest church of any denomination. Situated close to the university at the northern end of the CBD on George Street it is visible from much of the central city.It was...

in the north of the city, and the Tokomairiro Presbyterian Church in Milton

Milton, New Zealand

Milton is a town of 2,000 people, located on State Highway 1, 50 kilometres to the south of Dunedin in Otago, New Zealand. It lies on the floodplain of the Tokomairiro River, one branch of which loops past the north and south ends of the town...

, said at the time of its construction to have been the southernmost building of its height.

Lawson also designed Knox Church

Knox Church, Dunedin

Knox Church is a notable building in Dunedin, New Zealand. It houses the city's second Presbyterian congregation and is the city's largest church of any denomination. Situated close to the university at the northern end of the CBD on George Street it is visible from much of the central city.It was...

, which has a similar tower, also in Dunedin. This building, less well known than First Church, also designed in the 13th century Gothic style, but in bluestone, is considered by some to be his finest achievement.

Larnach Castle 1871

Larnach Castle

Larnach Castle , is an imposing mansion on the ridge of the Otago Peninsula within the limits of the city of Dunedin, New Zealand, close to the small settlement of Pukehiki...

. It was built in 1871 for William Larnach

William Larnach

William James Mudie Larnach was a New Zealand businessman and politician. He is known for building Larnach Castle and for his suicide.- Early career :Larnach was born in the Hunter Valley, north of Sydney, Australia...

, a local businessman and politician recalled for his bravura personal style. It has been hailed as one of New Zealand's finest mansions, described on its completion as: "doubtless the most princely, as it is the most substantial and elegant residence in New Zealand". There is a tradition that Larnach designed his house after Castle Forbes, his father's house at Baroona in Australia. The plans, however, are unquestionably from Lawson's office. The origin of the myth is simply that Larnach Castle has verandahs, doubtless insisted on by Larnach, an obviously colonial addition to its otherwise conventional revivalist design. However these do lend it distinction.

Although some have questioned it Larnach Castle is an essay in the revived Scottish baronial manner. The main facade resembles a small, castellated tower house, with the characteristic rubble masonry, turrets and battlements, present at Abbotsford, an exemplar of the style. It has been accurately described as a "castellated villa wrapped in a two storey verandah". The principal facade is dominated by a central tower complete with a stair turret which gives the house its castle-like appearance.

The interior of the building is ornate, with imported marbles and Venetian glass used in the Italianate decoration. As with First Church, there are also numerous carvings by Louis Godfrey. It took 200 men three years to complete the shell and a further twelve years for the interior to be finished. In 1887 the building was further extended by the addition of a 3000 square feet (278.7 m²) ballroom. In 1880, following the death of his first wife, Larnach had Lawson design in Dunedin's Northern Cemetery a miniaturised version of First Church as a family mausoleum

Mausoleum

A mausoleum is an external free-standing building constructed as a monument enclosing the interment space or burial chamber of a deceased person or persons. A monument without the interment is a cenotaph. A mausoleum may be considered a type of tomb or the tomb may be considered to be within the...

. Larnach was interred in the mauoleum himself. While serving as New Zealand's Minister of Finance and of Mines in 1898, he committed suicide in a committee room of the parliamentary building in Wellington, not because of the financial stresses of the Colonial Bank, as previously thought but because of circulating rumours about an affair between his eldest son and his third wife.

Otago Boys' High School 1885

Otago Boys' High School

Otago Boys' High School is one of New Zealand's oldest boys' secondary schools, located in Dunedin, Otago, New Zealand. It was founded on 3 August 1863 and moved to its present site in 1885. The main building was designed by Robert Lawson and is regarded as one of the finest Gothic revival...

, Arthur Street, Dunedin, was completed in 1885. Often referred to as Gothic, in fact it is a hybrid of several orders of architecture with obvious renaissance

Renaissance

The Renaissance was a cultural movement that spanned roughly the 14th to the 17th century, beginning in Italy in the Late Middle Ages and later spreading to the rest of Europe. The term is also used more loosely to refer to the historical era, but since the changes of the Renaissance were not...

/Tudor style

Tudor style architecture

The Tudor architectural style is the final development of medieval architecture during the Tudor period and even beyond, for conservative college patrons...

, and Gothic influences: the nearest style into which it can be categorised is probably Jacobethan

Jacobethan

Jacobethan is the style designation coined in 1933 by John Betjeman to describe the mixed national Renaissance revival style that was made popular in England from the late 1820s, which derived most of its inspiration and its repertory from the English Renaissance , with elements of Elizabethan and...

(a peculiarly English form of the Neo-Renaissance

Neo-Renaissance

Renaissance Revival is an all-encompassing designation that covers many 19th century architectural revival styles which were neither Grecian nor Gothic but which instead drew inspiration from a wide range of classicizing Italian modes...

. The building has long been regarded as one of the finest examples of architecture in Dunedin, built of stone with many window embrasure

Embrasure

In military architecture, an embrasure is the opening in a crenellation or battlement between the two raised solid portions or merlons, sometimes called a crenel or crenelle...

s and corners of lighter quoin

Quoin (architecture)

Quoins are the cornerstones of brick or stone walls. Quoins may be either structural or decorative. Architects and builders use quoins to give the impression of strength and firmness to the outline of a building...

s. The school's many turrets and towers led to the architect Nathaniel Wales describing it in 1890 as "a semi-ecclesiastical building" in the "Domestic Tudor style of medieval architecture".

The building, though castle-like, is not truly castellated although some of the windows are surmounted by crennelated ornament. Its highest point, the dominating tower, is decorated by stone balustrading. The tower has turrets at each corner — an overall composition more redolent of the early 17th century English Renaissance than an earlier true castle. While the school's entrance arch was obviously designed to impart an ecclesiastical or collegiate air, the school has the overall appearance of a prosperous Victorian

Victorian architecture

The term Victorian architecture refers collectively to several architectural styles employed predominantly during the middle and late 19th century. The period that it indicates may slightly overlap the actual reign, 20 June 1837 – 22 January 1901, of Queen Victoria. This represents the British and...

country house

English country house

The English country house is a large house or mansion in the English countryside. Such houses were often owned by individuals who also owned a London house. This allowed to them to spend time in the country and in the city—hence, for these people, the term distinguished between town and country...

Works in the classical style

Oamaru

Oamaru , the largest town in North Otago, in the South Island of New Zealand, is the main town in the Waitaki District. It is 80 kilometres south of Timaru and 120 kilometres north of Dunedin, on the Pacific coast, and State Highway 1 and the railway Main South Line connects it to both...

, 120 kilometres (75 mi) north of Dunedin. Here, as in Dunedin itself, Lawson built in the local Oamaru stone

Oamaru stone

Oamaru stone is a hard, compact limestone, quarried at Weston, near Oamaru in Otago, New Zealand.The stone is used for building purposes, especially where ornate moulding is required. The finished stonework has a creamy, sandy colour...

, a hard limestone that is ideal for building purposes, especially where ornate moulding is required. The finished stonework has a creamy, sandy colour. Unfortunately, it is not strongly resistant to today's pollution, and can be prone to surface crumbling.

National Bank, Oamaru 1871

This building, completed in 1871, is one of Lawson's successful exercises into classical architecture, designed in a near Palladian style. A perfectly proportioned porticoPortico

A portico is a porch leading to the entrance of a building, or extended as a colonnade, with a roof structure over a walkway, supported by columns or enclosed by walls...

prostyle

Prostyle

Prostyle is an architectural term defining free standing columns across the front of a building, as often in a portico. The term is often used as an adjective when referring to the portico of a classical building which projects from the main structure...

, its pediment

Pediment

A pediment is a classical architectural element consisting of the triangular section found above the horizontal structure , typically supported by columns. The gable end of the pediment is surrounded by the cornice moulding...

supported by four Corinthian columns, projects from a square building of five bay

Bay (architecture)

A bay is a unit of form in architecture. This unit is defined as the zone between the outer edges of an engaged column, pilaster, or post; or within a window frame, doorframe, or vertical 'bas relief' wall form.-Defining elements:...

s, the three central bays being behind the portico. The temple

Temple

A temple is a structure reserved for religious or spiritual activities, such as prayer and sacrifice, or analogous rites. A templum constituted a sacred precinct as defined by a priest, or augur. It has the same root as the word "template," a plan in preparation of the building that was marked out...

-like portico gives the impression of entering a pantheon rather than a bank

Bank

A bank is a financial institution that serves as a financial intermediary. The term "bank" may refer to one of several related types of entities:...

. The proportions of the main facade of this building display a Palladian symmetry, almost worthy of Palladio himself; however, unlike a true Palladian design, the two floors of the bank are of equal value, only differentiated by the windows of the ground floor being round-topped, while those above are the same size but have flat tops. Of all Lawson's classical designs, the National Bank is perhaps the most conventional in terms of adherence to classical rules of architecture as defined in Palladio's I Quattro Libri dell'Architettura

I Quattro Libri dell'Architettura

I quattro libri dell'architettura is an Italian treatise on architecture by the architect Andrea Palladio . It was first published in four volumes in 1570 in Venice, illustrated with woodcuts after the author's own drawings. It has been reprinted and translated many times...

. As his career progressed he became more adventurous in his classical designs, not always with the harmony and success he achieved at the National Bank.

While working on the elegantly simple National Bank, Lawson was also simultaneously employed on the architecturally vastly different Larnach Castle, which suggests that unlike the many notable architects who graduate through their careers from one style to another, Lawson could produce whatever his client required at any stage in his career.

Bank of New South Wales 1883

This Oamaru public building was designed in 1883. Neoclassical in design, its limestone facade is dominated by a great six-columned, unpedimented porticoPortico

A portico is a porch leading to the entrance of a building, or extended as a colonnade, with a roof structure over a walkway, supported by columns or enclosed by walls...

. The columns in the Corinthian order support a divided entablature

Entablature

An entablature refers to the superstructure of moldings and bands which lie horizontally above columns, resting on their capitals. Entablatures are major elements of classical architecture, and are commonly divided into the architrave , the frieze ,...

; the lower section or architrave

Architrave

An architrave is the lintel or beam that rests on the capitals of the columns. It is an architectural element in Classical architecture.-Classical architecture:...

bears the inscription "Bank of New South Wales", while above the frieze

Frieze

thumb|267px|Frieze of the [[Tower of the Winds]], AthensIn architecture the frieze is the wide central section part of an entablature and may be plain in the Ionic or Doric order, or decorated with bas-reliefs. Even when neither columns nor pilasters are expressed, on an astylar wall it lies upon...

remains undecorated. The building, while not jarring, has less architectural merit than the National Bank building, even though it was originally intended to be more classical and impressive than its neighbour. The imposing effect the architect sought is lessened at ground level where the portico's columns are linked by a balustrade. This extinguishes the clean-lined effect one would expect in a classical building of this stature and order and reduces the building's appearance to that of a doll's house. This effect is exacerbated by the windows within the portico (flat topped on the lower floor and round topped on the upper floor); these are disproportionately large and destroy the "temple" effect which the great portico was intended to create. Today, this externally unaltered building is used as an art gallery

Art gallery

An art gallery or art museum is a building or space for the exhibition of art, usually visual art.Museums can be public or private, but what distinguishes a museum is the ownership of a collection...

.

The Star and Garter Hotel

Hotel

A hotel is an establishment that provides paid lodging on a short-term basis. The provision of basic accommodation, in times past, consisting only of a room with a bed, a cupboard, a small table and a washstand has largely been replaced by rooms with modern facilities, including en-suite bathrooms...

is one of Lawson's more adventurous forays into classical architecture. Forsaking Palladian-influenced temple-like columns and porticos, he initially took as his inspiration the mannerist palazzi

Palazzo

Palazzo, an Italian word meaning a large building , may refer to:-Buildings:*Palazzo, an Italian type of building**Palazzo style architecture, imitative of Italian palazzi...

, which were a reaction to the more ornate high renaissance

Renaissance

The Renaissance was a cultural movement that spanned roughly the 14th to the 17th century, beginning in Italy in the Late Middle Ages and later spreading to the rest of Europe. The term is also used more loosely to refer to the historical era, but since the changes of the Renaissance were not...

style of architecture popular in early 16th century Italy. There are even some minor similarities between this building and the Palazzo del Te

Palazzo del Te

Palazzo del Te or Palazzo Te is a palace in the suburbs of Mantua, Italy. It is a fine example of the mannerist style of architecture, the acknowledged masterpiece of Giulio Romano...

. Just as at street level the palazzi often have a ground floor of rusticated

Rustication (architecture)

thumb|upright|Two different styles of rustication in the [[Palazzo Medici-Riccardi]] in [[Florence]].In classical architecture rustication is an architectural feature that contrasts in texture with the smoothly finished, squared block masonry surfaces called ashlar...

stone, so did this hotel. Massive blocks of ashlar

Ashlar

Ashlar is prepared stone work of any type of stone. Masonry using such stones laid in parallel courses is known as ashlar masonry, whereas masonry using irregularly shaped stones is known as rubble masonry. Ashlar blocks are rectangular cuboid blocks that are masonry sculpted to have square edges...

were used to create an impression of strength, supporting the more delicately designed floor above; this feeling of strength was further enhanced by double pilasters serving merely to imply a need to support the great weight above.

Above this solid and severe facade that Lawson chose instead of the customary two or three floors, the massive blocks of stone support just one floor. This upper floor is not an obvious piano nobile

Piano nobile

The piano nobile is the principal floor of a large house, usually built in one of the styles of classical renaissance architecture...

, but appears, though of more delicate and simple design, to be of equal value to the floor below. The rusticated pilasters of the lower floor are continued above, but become smooth dressed stone to match the upper facade. The pilasters' capitals are Corinthian, and as at the Bank of New South Wales they support an undecorated entablature. The centre and focal point of the building is marked by a pediment, which again gives the air of a palazzo.

However, what Lawson created was not a mannerist or indeed Palladian town palazzo at all but a hybrid, while similar, at first glance, to the neo-palladian villas and country houses of the late 18th century found in Italy and England, examples being Villa di Poggio Imperiale

Villa di Poggio Imperiale

Villa del Poggio Imperiale is a predominantly neoclassical former grand ducal villa in Arcetri, just to the south of Florence in Tuscany, central Italy...

and Woburn Abbey

Woburn Abbey

Woburn Abbey , near Woburn, Bedfordshire, England, is a country house, the seat of the Duke of Bedford and the location of the Woburn Safari Park.- Pre-20th century :...

. The Star and Garter, though, through Lawson's "pick, mix and match" approach to different forms of classical architecture is in its own way quite unique.

Since the Star and Garter's completion, many of its windows have either been blocked or enlarged, changes that have been detrimental to the architectural effect Lawson created. The building is now used mainly by a theatre company, although a restaurant at the eastern end of the building retains the hotel's original name.

Disgrace

The 1882 exhibition in Christchurch provided a stepping stone in Lawson's career. Following the death of Benjamin Mountfort, who had monopolised the new city's architecture, Lawson was commissioned to design the exhibition halls which led to the important and prestigious commission of designing the Opera House. This period was to be the pinnacle of Lawson's success and prestige in his lifetime. The commission that was the accolade of his success, the design of New Zealand's largest single structure and Lawson's most flamboyant design, was simultaneously to become the cause of his downfall and loss of reputation.

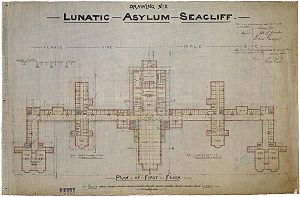

Seacliff Lunatic Asylum

Seacliff Lunatic Asylum was a psychiatric hospital in Seacliff, New Zealand. When built in the late 19th century, it was the largest building in the country, noted for its scale and extravagant architecture...

, designed to house five-hundred patients and fifty staff. On its completion it was New Zealand's largest building. Old photographs show a huge, grandiose building loosely in the Gothic style, but with an almost Neuschwanstein quality. It was later said of the design that "the Victorians might not have wanted their lunatics living with them, but they liked to house them grandly". Architecturally this was Lawson at his most exuberant, extravagant and adventurous: Otago Boys High School seems almost severe and restrained in comparison. Turrets on corbel

Corbel

In architecture a corbel is a piece of stone jutting out of a wall to carry any superincumbent weight. A piece of timber projecting in the same way was called a "tassel" or a "bragger". The technique of corbelling, where rows of corbels deeply keyed inside a wall support a projecting wall or...

s project from nearly every corner; the gabled roof line is dominated by a mammoth tower complete with further turrets and a spire. The vast edifice contained four and a half million bricks made of local clay on site, and was 225 metres long by 67 metres (740 by 220 feet) wide. The great tower, actually designed so that the inmates could be observed should they attempt to escape, was almost 50 metres (164 ft) tall.

Structural problems within the building began to manifest themselves even before completion. Finally in 1887 a major landslip occurred which rendered the north wing unsafe; the problems with the design could no longer be ignored.

In 1888 an enquiry into the collapse was set up. In February, realising that he may be in legal trouble, Lawson applied to the enquiry to be allowed counsel to defend him. During the enquiry all involved in the construction — including the contractor, the head of the Public Works Department, the projects clerk of works and Lawson himself — were forced to give evidence to support their competence; however, it was the architect on whom the ultimate responsibility fell, and who incurred the disgrace when the enquiry publicised their findings. Lawson was found both "negligent and incompetent". New Zealand was at this time suffering an economic recession and Lawson found himself virtually unemployable. After a short period assisting the Wellington architect William Turnbull in 1890, he returned to Melbourne.

Final years

Frederick Grey

Admiral Sir Frederick William Grey GCB was a senior naval officer and First Naval Lord.-Naval career:Born the son of Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey, the former Prime Minister, Grey joined the Royal Navy in 1819. He was given command of HMS Actaeon in 1830, HMS Jupiter in 1835, HMS Endymion in 1840...

. Together they designed Earlsbrae Hall, a large neoclassical house at Essendon

Essendon, Victoria

Essendon is a suburb in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, 10 km north-west from Melbourne's central business district. Its Local Government Area is the City of Moonee Valley...

, Victoria

Victoria (Australia)

Victoria is the second most populous state in Australia. Geographically the smallest mainland state, Victoria is bordered by New South Wales, South Australia, and Tasmania on Boundary Islet to the north, west and south respectively....

. This is now considered by some experts to be one of his greatest works. Often said to resemble a Grecian temple, this mansion is actually more closely related in style to the neo-Palladian architecture that evolved in the southern plantation houses of North America

North America

North America is a continent wholly within the Northern Hemisphere and almost wholly within the Western Hemisphere. It is also considered a northern subcontinent of the Americas...

in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. While Lawson was undoubtedly involved in the design, it is impossible to distinguish his input from that of Grey. As the mansion's foundation stone was laid in 1890, the same year as Lawson's return to Melbourne, it seems likely that Grey had begun to work on the plans before Lawson joined him, especially as the land had been purchased in order to build the mansion two years earlier. There are several touches in the design which are almost certainly Lawson's — the Corinthian portico is similar to that designed by him for the National Bank at Oamaru, but here it is extended and flanked by the two-storeyed verandahs that Lawson used at Larnach Castle. Unlike this earlier construction at Earlsbrea, they are elegantly represented in stone and unglazed. The cost of construction to the owner Collier McCracken was £35,000; it later sold in 1911 for just £6000. Commercial buildings which survive from Lawson's Melbourne years include the Moran and Cato warehouse in Fitzroy

Fitzroy, Victoria

Fitzroy is an inner city suburb of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, 2 km north-east from Melbourne's central business district. Its Local Government Area is the City of Yarra. Its borders are Alexandra Parade , Victoria Parade , Smith Street and Nicholson Street. Fitzroy is Melbourne's...

and the College Church in Parkville

Parkville, Victoria

Parkville is an inner city suburb in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, 3 km north from Melbourne's central business district. Its Local Government Area is the City of Melbourne. At the 2006 Census, the population was 4,980....

, which were completed in 1897.

In 1900, at the age of 67, Lawson came out of his ten-year-long self-imposed exile from New Zealand and returned to Dunedin. Here he entered into practice with his former pupil J.Louis Salmond. A number of commercial and residential buildings were erected under their joint names, including the brick house known as "Threave" built for Watson Shennan at 367 High Street. This is one of Lawson's last works. Threave has particularly ornate carved verandahs in the Gothic style, but is today better known for its gardens than architecture.

The Lawson–Salmond partnership would not last long. In 1902 Lawson died suddenly at Pleasant Point

Pleasant Point, New Zealand

Pleasant Point is a small country town in southern Canterbury, New Zealand, some 19 km inland from Timaru. A service town for the surrounding farming district, it has a population of 1,222 and one of its main attractions is the heritage railway, the Pleasant Point Museum and Railway, which...

, Canterbury, on 3 December. By the time of his death he had begun to re-establish his reputation, having been elected vice-president of the Otago Institute of Architects.

Appraisal and legacy

Lancet window

A lancet window is a tall narrow window with a pointed arch at its top. It acquired the "lancet" name from its resemblance to a lance. Instances of this architectural motif are most often found in Gothic and ecclesiastical structures, where they are often placed singly or in pairs.The motif first...

s were often avoided and replaced by large bay windows, allowing the rooms to be flooded with light rather than creating the darker interiors of true Gothic buildings. Larnach Castle has often been criticised as being clumsy and incongruous, but this derives from the persistent misinterpretation of Lawson's work as Scottish baronial. It is true that in a Scottish glen

Valley

In geology, a valley or dale is a depression with predominant extent in one direction. A very deep river valley may be called a canyon or gorge.The terms U-shaped and V-shaped are descriptive terms of geography to characterize the form of valleys...

, much of his work would be incongruous, but Lawson realised that he was designing not for the glens and mountains of his homeland, but rather for a new country, with new ideals and vast vista

View

A view is what can be seen in a range of vision. View may also be used as a synonym of point of view in the first sense. View may also be used figuratively or with special significance—for example, to imply a scenic outlook or significant vantage point:...

s. Thus, set upon its two-storeyed verandahs, and looking out over the Otago Peninsula

Otago Peninsula

The Otago Peninsula is a long, hilly indented finger of land that forms the easternmost part of Dunedin, New Zealand. Volcanic in origin, it forms one wall of the eroded valley that now forms Otago Harbour. The peninsula lies south-east of Otago Harbour and runs parallel to the mainland for...

and Otago Harbour

Otago Harbour

Otago Harbour is the natural harbour of Dunedin, New Zealand, consisting of a long, much-indented stretch of generally navigable water separating the Otago Peninsula from the mainland. They join at its southwest end, from the harbour mouth...

from 240 metres (787.4 ft) above sea level, the mansion seems perfectly positioned.

At the time of Lawson's work the rival schools of Classical and Gothic architecture were both equally fashionable. In his ecclesiastical commissions, Lawson worked exclusively for the Protestant denominations and thus never received the opportunity to build a great church in the classical style. His major works therefore have to be appraised through his use of the Gothic. First Church thus has to be regarded as his masterpiece. His classical works, though often competently and skillfully executed, were mostly confined to smaller public buildings. He never had the opportunity to refine and hone his classical ideas, and therefore these never had the opportunity to make the same impact as his Gothic works.

Much of Lawson's work is either demolished or much altered. Two of his timber Gothic churches survive at Kakanui

Kakanui

The small town of Kakanui lies on the coast of Otago, in New Zealand, fourteen kilometres to the south of Oamaru. The Kakanui River and its estuary divide the township in two. The part of the settlement south of the river, also known as Kakanui South, formerly "Campbells Bay", was developed as a...

(1870) and East Gore

Gore, New Zealand

Gore is a town, surrounding borough, and district in the Southland region of the South Island of New Zealand.-Geography:The Gore District has a land area of 1,251.62 km² and a resident population of...

(1881). The designs still standing (which include all of the works described in detail above) have ensured that Lawson's reputation has fully recovered from the condemnation he received following the Seacliff enquiry.

Today, Lawson is lauded as the architect of some of New Zealand's finest historic buildings. The Otago Branch of the New Zealand Historic Places Trust has inaugurated a memorial lecture programme, the RA Lawson Lecture, which is presented in Dunedin annually by an eminent local or overseas speaker. NZHPT Otago Branch Archives, Dunedin.

Buildings by Lawson

An incomplete list of works authoritatively attributed to Lawson includes:- Park's School, DunedinDunedinDunedin is the second-largest city in the South Island of New Zealand, and the principal city of the Otago Region. It is considered to be one of the four main urban centres of New Zealand for historic, cultural, and geographic reasons. Dunedin was the largest city by territorial land area until...

(1864). Also known as South District School, now a family house in William Street, Dunedin. - First Church, which has been described by the Institute of Architects as a “Magnificent example of Gothic Architecture” (1867–1873).

- Wesleyan Church, Dunedin (1869). Now the Fortune Theatre.

- Peter Engels' house, corner of Scotland and London Streets, Dunedin (1869).

- East Taieri Presbyterian church, East Taieri. Gothic, lighter quoins, spire, substantial buttresses. (1870).

- National Bank, OamaruOamaruOamaru , the largest town in North Otago, in the South Island of New Zealand, is the main town in the Waitaki District. It is 80 kilometres south of Timaru and 120 kilometres north of Dunedin, on the Pacific coast, and State Highway 1 and the railway Main South Line connects it to both...

Palladian.(1871). - Arthur Briscoe & Co. Warehouse, Dunedin (1872).

- Larnach Castle (1872–75).

- Trustees Executors Office, originally the National Mortgage and Agency building, Bond, Water and Crawford Streets, Dunedin, (1873).

- Wilson's Bond, north west corner of Bond and Jetty Streets, Dunedin, (1873).

- Knox Church, DunedinKnox Church, DunedinKnox Church is a notable building in Dunedin, New Zealand. It houses the city's second Presbyterian congregation and is the city's largest church of any denomination. Situated close to the university at the northern end of the CBD on George Street it is visible from much of the central city.It was...

. (1874–1876). - Union Bank of Australasia (later ANZ Bank), Princes StreetPrinces Street, DunedinPrinces Street is a major street in Dunedin, the second largest city in the South Island of New Zealand. It runs south-southwest for two kilometres from The Octagon in the city centre to the Oval sports ground, close to the city's Southern Cemetery...

, Dunedin (1874). Palladian, similar to the National Bank in Oamaru. Currently used as a nightclub. - Dunedin Municipal Chambers. (1878–1880) Dunedin Town HallDunedin Town HallThe Dunedin Town Hall is a municipal building in the city of Dunedin in New Zealand. It is located in the heart of the city extending from The Octagon, the central plaza, to Moray Place through a whole city block. It is the seat of the Dunedin City Council, providing its formal meeting chamber, as...

- SeacliffSeacliff, New ZealandSeacliff is a small village located north of Dunedin in the Otago region of New Zealand's South Island. The village lies roughly half way between the estuary of Blueskin Bay and the mouth of the Waikouaiti River at Karitane, on the eastern slopes of Kilmog hill...

Asylum. Gothic. (1879–1884). - Brown, Ewing Company building, Dunedin (1880s).

- Bing Harris Company building, High Street, Dunedin. (1868–1880).

- East Gore Presbyterian Church (1881).

- Martin & Watson's building, corner of the Octagon and lower Stuart Street, Dunedin (now the Bacchus building) (1882).

- Bank of New South Wales, Oamaru (now Forrester Gallery). Palladian. (1883).

- Otago Boys' High School. (1885).

- Malloch's Store, Cumberland Street, Dunedin, (1885).

- Tokomairiro Presbyterian Church, MiltonMilton, New ZealandMilton is a town of 2,000 people, located on State Highway 1, 50 kilometres to the south of Dunedin in Otago, New Zealand. It lies on the floodplain of the Tokomairiro River, one branch of which loops past the north and south ends of the town...

. (1889). - Earlsbrae Hall, Essendon, VictoriaEssendon, VictoriaEssendon is a suburb in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, 10 km north-west from Melbourne's central business district. Its Local Government Area is the City of Moonee Valley...

. (1890). Today known as Lowther Hall, it forms part of an Anglican Grammar School.Photo at Subdivision and Consolidation of Land. Heritage Council Victoria. Retrieved on 2008-02-08 from 2004-12-17 internet archive. - "Threave" (private house), 367 High Street, Dunedin. (1900).

- "Wychwood" (private house), Dunedin (very likely Lawson's work, although certainty not completely established).

- Presbyterian church, HampdenHampden, New ZealandHampden is a rural settlement defined as a "populated area less than a town" in North Otago, New Zealand. It is located close to the North Otago coast, some 30 kilometres south of Oamaru, and 50 minutes north of Otago's largest city, Dunedin. It was named after the English politician John Hampden...

. - The Manse, PalmerstonPalmerston, New ZealandThe town of Palmerston, in New Zealand's South Island lies 50 kilometres to the north of the city of Dunedin. It is the largest town in the Waihemo Ward of the Waitaki District with a population of 890 residents...

. - The Larnach family crypt in the Northern Cemetery, Dunedin. (1881)

- The old Fire Station, Harrop Street, Dunedin (1878).

- ChristchurchChristchurchChristchurch is the largest city in the South Island of New Zealand, and the country's second-largest urban area after Auckland. It lies one third of the way down the South Island's east coast, just north of Banks Peninsula which itself, since 2006, lies within the formal limits of...

Opera House. - The Star and Garter Hotel, Oamaru. See text.

- Post Office, LawrenceLawrence, New ZealandLawrence is a small town of 474 inhabitants in Otago, in New Zealand's South Island. It is located on State Highway 8, the main route from Dunedin to the inland towns of Queenstown and Alexandra...

. - St Andrew's Presbyterian Church (later Word of Life Church).