Origins of the Cold War

Encyclopedia

The Origins of the Cold War are widely regarded to lie most directly in the relations between the Soviet Union

and its allies

the United States

, Britain

and France

in the years 1945–1947. Those events led to the Cold War

that endured for just under half a century.

Events preceding the Second World War, and even the Russian Revolution of 1917

, underlay pre–World War II tensions between the Soviet Union, western Europe

an countries and the United States. A series of events during and after World War II exacerbated tensions, including the Soviet-German pact during the first two years of the war leading to subsequent invasions, the perceived delay of an amphibious invasion

of German-occupied Europe, the western allies' support of the Atlantic Charter

, disagreement in wartime conferences over the fate of Eastern Europe

, the Soviets' creation of an Eastern Bloc

of Soviet satellite state

s, western allies scrapping the Morgenthau Plan

to support the rebuilding of German industry, and the Marshall Plan

.

and the West predated the Russian Revolution of 1917. From the neo-Marxist

World Systems perspective, Russia differed from the West as a result of its late integration into the capitalist

world economy in the 19th century. Struggling to catch up with the industrialized

West as of the late 19th century, Russia upon the revolution in 1917 was essentially a semi-peripheral or peripheral state whose internal balance of forces, tipped by the domination of the Russian industrial sector by foreign capital, had been such that it suffered a decline in its relative diplomatic power internationally. From this perspective, the Russian Revolution represented a break with a form of dependent industrial development and a radical withdrawal from the capitalist world economy.

Other scholars have argued that Russia and the West developed fundamentally different political culture

s shaped by Eastern Orthodoxy and rule of the tsar

. Others have linked the Cold War to the legacy of different heritages of empire-building

between the Russians and Americans. From this view, the United States, like the British Empire

, was fundamentally a maritime power based on trade and commerce, and Russia was a bureaucratic and land-based power that expanded from the center in a process of territorial accretion.

Imperial rivalry between the British and tsarist Russia preceded the tensions between the Soviets and the West following the Russian Revolution. Throughout the 19th century, improving Russia's maritime access was a perennial aim of the tsars' foreign policy. Despite Russia's vast size, most of its thousands of miles of seacoast was frozen over most of the year, or access to the high seas was through straits controlled by other powers, particularly in the Baltic

and Black

Seas. The British, however, had been determined since the Crimean War

in the 1850s to slow Russian expansion at the expense of Ottoman Turkey

, the "sick man of Europe

." With the completion of the Suez Canal

in 1869, the prospect of Russia seizing a portion of the Ottoman seacoast on the Mediterranean

, potentially threatening the strategic waterway, was of great concern to the British. British policymakers were also apprehensive about the close proximity of the Tsar's territorially expanding empire in Central Asia to India

, triggering a series of conflicts between the two powers in Afghanistan

, dubbed The Great Game

.

The British long exaggerated the strength of the relatively backward sprawling Russian empire, which according to the Wisconsin school was more concerned with the security of its frontiers than conquering Western spheres of influence. British fears over Russian expansion, however, subsided following Russia's stunning defeat in the Russo-Japanese War

in 1905.

Historians associated with the Wisconsin school see parallels between 19th century Western rivalry with Russia and the Cold War tensions of the post–World War II period. From this view, Western policymakers misinterpreted postwar Soviet policy in Europe as expansionism, rather than a policy, like the territorial growth of imperial Russia, motivated by securing vulnerable Russian frontiers.

, the US, Britain, and Russia had been allies for a few months from April 1917 until the Bolshevik

s seized power in Russia in November. In 1918, the Bolsheviks negotiated a separate peace with the Central Powers

at Brest-Litovsk

. This separate peace contributed to American mistrust of the Soviets, since it left the Western Allies

to fight the Central Powers

alone.

As a result of the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution in Russia followed by its withdrawal from World War I

, Soviet Russia found itself isolated in international diplomacy. Leader Vladimir Lenin

stated that the Soviet Union was surrounded by a "hostile capitalist encirclement" and he viewed diplomacy as a weapon to keep Soviet enemies divided, beginning with the establishment of the Soviet Comintern

, which called for revolutionary upheavals abroad. Tensions between Russia (including its allies) and the West turned intensely ideological. The landing of U.S. troops in Russia in 1918, which became involved in assisting

the anti-Bolshevik Whites in the Russian Civil War

helped solidify lasting suspicions among Soviet leadership of the capitalist world. This was the first event which made Russian-American relations a matter of major, long-term concern to the leaders in each country.

), the Bolsheviks proclaimed a worldwide challenge to capitalism

. Subsequent Soviet leader Joseph Stalin

, who viewed the Soviet Union as a "socialist island", stated that the Soviet Union must see that "the present capitalist encirclement is replaced by a socialist encirclement."

As early as 1925, Stalin stated that he viewed international politics as a bipolar world in which the Soviet Union would attract countries gravitating to socialism and capitalist countries would attract states gravitating toward capitalism while the world was in a period of "temporary stabilization of capitalism" preceding its eventual collapse. Several events fueled suspicion and distrust between the western powers and the Soviet Union: the Bolsheviks' challenge to capitalism; the Polish-Soviet War

; the 1926 Soviet funding of a British general workers strike causing Britain to break relations with the Soviet Union; Stalin's 1927 declaration that peaceful coexistence with "the capitalist countries . . . is receding into the past"; conspiratorial allegations in the Shakhty show trial

of a planned French and British-led coup d'etat

; the Great Purge

involving a series of campaigns of political repression and persecution in which over half a million Soviets were executed; the Moscow show trials

including allegations of British, French, Japanese and German espionage; the controversial death of 6–8 million people in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic in the 1932–3 Ukrainian famine

; western support of the White Army

in the Russian Civil War

; the US refusal to recognize the Soviet Union until 1933; and the Soviet entry into the Treaty of Rapallo

. This outcome rendered Russian–American relations a matter of major long-term concern for leaders in both countries.

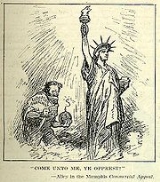

Differences existed in the political and economic systems of western

democracies

and the Soviet Union— socialism

versus capitalism, economic autarky

versus free trade

, state planning

versus private enterprise—became simplified and refined in national ideologies to represent two ways of life. Following the postwar Red Scare

, many in the U.S. saw the Soviet system as a threat. The atheistic

nature of Soviet communism

also concerned many Americans. The American ideals of free determination and President Woodrow Wilson

's Fourteen Points

conflicted with many of the USSR's policies. Up until the mid-1930s, both British and U.S. policymakers commonly assumed the communist Soviet Union to be a much greater threat than disarmed and democratic Germany and focused most of their intelligence efforts against Moscow

. However it has also been stated that in the period between the two wars, the U.S. had little interest in the Soviet Union or its intentions. America, after minimal contribution to World War I and the Russian Civil War, began to favor an isolationist stance when concerned with global politics (something which contributed to its late involvement in the Second World War). An example of this can be seen from its absence in the League of Nations

, an international political forum, much like the United Nations

; President Woodrow Wilson was one of the main advocates for the League of Nations; the United States Senate

, however, voted against joining. America was enjoying unprecedented economic growth throughout the 1910s and early 20s. However, the world soon plunged into the Great Depression

and the U.S. was therefore even less inclined to make contributions to the international community while it suffered from serious financial and social problems at home.

The Soviets further resented Western appeasement

of Adolf Hitler

after the signing of the Munich Pact in 1938.

Suspicions intensified when, during the summer of 1939, after conducting negotiations with both a British-French group and Germany regarding potential military and political agreements, the Soviet Union and Germany signed a Commercial Agreement providing for the trade of certain German military and civilian equipment in exchange for Soviet raw materials and the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, commonly named after the foreign secretaries of the two countries (Molotov-Ribbentrop), which included a secret agreement to split Poland and Eastern Europe between the two states.

One week after the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact's signing, the partition of Poland commenced with the German invasion

of western Poland. Relations between the Soviet Union and the West further deteriorated when, two weeks after the German invasion, the Soviet Union invaded eastern Poland

while coordinating with German forces. The Soviet Union then invaded Finland

, which was also ceded to it under the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact's secret protocol, resulting in stiff losses and the entry of an interim peace treaty granting it parts of eastern Finland. In June, the Soviets issued an ultimatum demanding Bessarabia

, Bukovina

and the Hertza region

from Romania

, after which Romania caved to Soviet demands for occupation. That month, the Soviets also annexed the Baltic countries of Lithuania, Estonia and Latvia

From August 1939 to June 1941 (when Germany broke the Pact and invaded the Soviet Union

), relations between the West and the Soviets deteriorated further when the Soviet Union and Germany engaged in an extensive economic relationship

by which the Soviet Union sent Germany vital oil, rubber, manganese and other material in exchange for German weapons, manufacturing machinery and technology. In late 1940, the Soviets also engaged in talks with Germany regarding potential membership in the Axis

, culminating in the countries trading written proposals, though no agreement for Soviet Axis entry was ever reached.

Throughout World War II, the Soviet NKVD

Throughout World War II, the Soviet NKVD

's mole Kim Philby

had access to high-importance British MI6 intelligence, and passed it to the Soviets.

On June 22, 1941, Germany broke the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact with Operation Barbarossa

, the invasion of the Soviet Union through the territories that the two countries had previously divided. Stalin switched his cooperation from Hitler to Churchill. Britain and the Soviets signed a formal alliance, but the U.S. did not join until after the Attack on Pearl Harbor

on December 7, 1941. Immediately, there was disagreement between Britain's ally Poland and the Soviet Union. The British and Poles strongly suspected that when Stalin was cooperating with Hitler

he ordered the execution of about 22,000 Polish officer POWs, at what was later to become known as the Katyn massacre

. Still, the Soviets and the Western Allies were forced to cooperate, despite their tensions. The U.S. shipped vast quantities of Lend-Lease

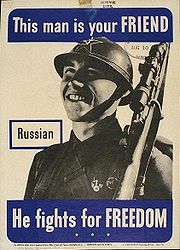

material to the Soviets.

During the war, both sides disagreed on military strategy, especially the question of the opening of a second front against Germany in Western Europe.

As early as July 1941, Stalin had asked Britain to invade northern France, but that country was in no position to carry out such a request. Stalin had asked the Western Allies to open a second front since the early months of the war—which finally occurred on D-Day

, June 6, 1944.

In early 1944 MI6 re-established Section IX, its prewar anti-Soviet section, and Philby took a position there. He was able to alert the NKVD

about all British intelligence on the Soviets–including what the American OSS

had shared with the British about the Soviets.

The Soviets believed at the time, and charged throughout the Cold War, that the British and Americans intentionally delayed the opening of a second front against Germany in order to intervene only at the last minute so as to influence the peace settlement and dominate Europe. Historians such as John Lewis Gaddis

dispute this claim, citing other military and strategic calculations for the timing of the Normandy invasion. In the meantime, the Russians suffered heavy casualties, with as many as twenty million dead. Nevertheless, Soviet perceptions (or misconceptions) of the West and vice versa left a strong undercurrent of tension and hostility between the Allied powers.

In turn, in 1944, the Soviets appeared to the Allies to have deliberately delayed the relief of the Polish underground

's Warsaw Uprising

against the Nazis. The Soviets did not supply the Uprising from the air, and for a significant time also refused to allow British and American air drops. On at least one occasion, a Soviet fighter shot down an RAF plane supplying the Polish insurgents in Warsaw. George Orwell

was moved to make a public warning about Soviet postwar intentions. A 'secret war' also took place between the British SOE

-backed AK

and Soviet NKVD

-backed partisans

. British-trained Polish special forces agent Maciej Kalenkiewicz

was killed by the Soviets at this time. The British and Soviets also sponsored competing factions of resistance fighters in Yugoslavia and Greece.

Both sides, moreover, held very dissimilar ideas regarding the establishment and maintenance of post-war security. The Americans tended to understand security in situational terms, assuming that, if US-style governments and markets were established as widely as possible, countries could resolve their differences peacefully, through international organization

s. The key to the US vision of security was a post-war world shaped according to the principles laid out in the 1941 Atlantic Charter

—in other words, a liberal international system based on free trade and open markets. This vision would require a rebuilt capitalist Europe, with a healthy Germany at its center, to serve once more as a hub in global affairs.

This would also require US economic and political leadership of the postwar world. Europe needed the USA's assistance if it was to rebuild its domestic production and finance its international trade. The USA was the only world power not economically devastated by the fighting. By the end of the war, it was producing around fifty percent of the world's industrial goods.

Soviet leaders, however, tended to understand security in terms of space. This reasoning was conditioned by Russia's historical experiences, given the frequency with which the country had been invaded over the last 150 years. The Second World War experience was particularly dramatic for the Russians: the Soviet Union suffered unprecedented devastation as a result of the Nazi onslaught, and over 20 million Soviet citizens died during the war; tens of thousands of Soviet cities, towns, and villages were leveled; and 30,100 Soviet factories were destroyed. In order to prevent a similar assault in the future, Stalin was determined to use the Red Army

to gain control of Poland

, to dominate the Balkans and to destroy utterly Germany's capacity to engage in another war. The problem was that Stalin's strategy risked confrontation with the equally powerful United States, who viewed Stalin's actions as a flagrant violation of the Yalta agreement.

At the end of the war in Europe, in May 1945, the Soviets insisted on occupying the Danish island of Bornholm

, due to its strategic position at the entrance to the Baltic. When the local German commander insisted on surrendering to the Western Allies, as did German forces in the rest of Denmark, the Soviets bombed the island, causing heavy casualties and damage among a civilian population which was only lightly touched throughout the war, and then invaded the island and occupied it until mid-1946 - all of which can be considered as initial moves in the Cold War.

Even before the war came to an end, it seemed highly likely that cooperation between the Western powers and the USSR would give way to intense rivalry or conflict. This was due primarily to the starkly contrasting economic ideologies of the two superpowers, now quite easily the strongest in the world. Whereas the USA was a liberal, multi-party democracy with an advanced capitalist economy, based on free enterprise and profit-making, the USSR was a one-party Communist dictatorship with a state-controlled economy where private wealth was all but outlawed.

of 16 Polish resistance leaders

who had spent the War fighting against the Nazis with British and American help. Within six years, 14 of them were dead.

At the Nuremburg Trials, the chief Soviet prosecutor submitted false documentation in an attempt to indict German defendants for the murder of around 22,000 Polish officers in the Katyn

forest near Smolensk. However, suspecting Soviet culpability, the other Allied prosecutors refused to support the indictment and German lawyers promised to mount an embarrassing defense. No one was charged or found guilty at Nuremberg for the Katyn Forest massacre

. In 1990, the Soviet government acknowledged that the Katyn massacre was carried out, not by the Germans, but by the Soviet secret police.

From September 1945, Polish resistance fighter and Righteous

Witold Pilecki

was sent by General Anders to spy against the communists in Poland. In 1948, he was executed on charges of spying and 'serving the interests of foreign imperialism'.

Several postwar disagreements between western and Soviet leaders were related to their differing interpretations of wartime and immediate post-war conferences.

Several postwar disagreements between western and Soviet leaders were related to their differing interpretations of wartime and immediate post-war conferences.

The Tehran Conference

in late 1943 was the first Allied conference in which Stalin was present. At the conference the Soviets expressed frustration that the Western Allies had not yet opened a second front against Germany in Western Europe. In Tehran, the Allies also considered the political status of Iran. At the time, the British had occupied southern Iran, while the Soviets had occupied an area of northern Iran bordering the Soviet republic of Azerbaijan. Nevertheless, at the end of the war, tensions emerged over the timing of the pull out of both sides from the oil-rich region.

At the February 1945 Yalta Conference

, the Allies attempted to define the framework for a postwar settlement in Europe. The Allies could not reach firm agreements on the crucial questions: the occupation of Germany, postwar reparations from Germany, and loans. No final consensus was reached on Germany, other than to agree to a Soviet request for reparations totaling $10 billion "as a basis for negotiations." Debates over the composition of Poland's postwar government were also acrimonious.

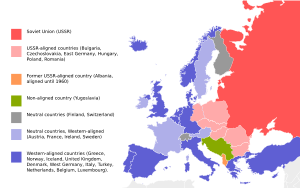

Following the Allied victory in May, the Soviets effectively occupied Eastern Europe, while the US had much of Western Europe. In occupied Germany, the US and the Soviet Union established zones of occupation and a loose framework for four-power control with the ailing French and British.

At the Potsdam Conference

At the Potsdam Conference

starting in late July 1945, the Allies met to decide how to administer the defeated Nazi Germany, which had agreed to unconditional surrender nine weeks earlier on May 7 and May 8, 1945, VE day. Serious differences emerged over the future development of Germany and Eastern Europe. At Potsdam, the US was represented by a new president, Harry S. Truman

, who on April 12 succeeded to the office upon Roosevelt's death. Truman was unaware of Roosevelt's plans for post-war engagement with the Soviet Union, and more generally uninformed about foreign policy and military matters. The new president, therefore, was initially reliant on a set of advisers (including Ambassador to the Soviet Union Averell Harriman, Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson

and Truman's own choice for secretary of state, James F. Byrnes

). This group tended to take a harder line towards Moscow than Roosevelt had done. Administration officials favoring cooperation with the Soviet Union and the incorporation of socialist economies into a world trade system were marginalized. The UK was represented by a new prime minister, Clement Attlee

, who had replaced Churchill after the Labour Party's defeat of the Conservatives in the 1945 general election.

One week after the Potsdam Conference ended, the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

added to Soviet distrust of the United States, when shortly after the attacks, Stalin protested to U.S. officials when Truman offered the Soviets little real influence in occupied Japan

.

The immediate end of Lend-Lease

from America to the USSR after the surrender of Germany also upset some politicians in Moscow, who believed this showed the U.S. had no intentions to support the USSR any more than they had to.

, and Soviet leader Joseph Stalin

, were key in shaping Europe's balance of power in the early postwar period.

However, toward the end of the war, the prospects of an Anglo-American front against the Soviet Union seemed slim from Stalin's standpoint. At the end of the war, Stalin assumed that the capitalist camp would resume its internal rivalry over colonies and trade, giving opportunity for renewed expansion at a later date, rather than pose a threat to the USSR. Stalin expected the United States to bow to domestic popular pressure for postwar demilitarization. Soviet economic advisors such as Eugen Varga

predicted that the U.S. would cut military expenditures, and therefore suffer a crisis of overproduction, culminating in another great depression. Based on Varga's analysis, Stalin assumed that the Americans would offer the Soviets aid in postwar reconstruction, needing to find any outlet for massive capital investments in order to sustain the wartime industrial production that had brought the U.S. out of the Great Depression

. However, to the surprise of Soviet leaders, the U.S. did not suffer a severe postwar crisis of overproduction

. As Stalin had not anticipated, capital investments in industry were sustained by maintaining roughly the same levels of government spending.

In the United States, a conversion to the prewar economy nevertheless proved difficult. Though the United States military was cut to a small fraction of its wartime size, America's military-industrial complex

that was created during the Second World War was not eliminated. Pressures to "get back to normal" were intense. Congress wanted a return to low, balanced budgets, and families clamored to see the soldiers sent back home. The Truman administration worried first about a postwar slump, then about the inflationary consequences of pent-up consumer demand. The G.I. Bill, adopted in 1944, was one answer: subsidizing veterans to complete their education rather than flood the job market and probably boost the unemployment figures. In the end, the postwar U.S. government strongly resembled the wartime government, with the military establishment—along with military-security industries—heavily funded. The postwar capitalist slump predicted by Stalin was averted by domestic government management, combined with the U.S. success in promoting

international trade and monetary relations.

and communism

. Those contrasts had been simplified and refined in national ideologies to represent two ways of life, each vindicated in 1945 by previous disasters. Conflicting models of autarky

versus exports, of state planning against private enterprise, were to vie for the allegiance of the developing and developed world in the postwar years.

U.S. leaders, following the principles of the Atlantic Charter

, hoped to shape the postwar world by opening up the world's markets to trade and markets. Administration analysts eventually reached the conclusion that rebuilding a capitalist Western Europe that could again serve as a hub in world affairs was essential to sustaining U.S. prosperity.

World War II resulted in enormous destruction of infrastructure and populations throughout Eurasia with almost no country left unscathed. The only major industrial power in the world to emerge intact—and even greatly strengthened from an economic perspective—was the United States. As the world's greatest industrial power, and as one of the few countries physically unscathed by the war, the United States stood to gain enormously from opening the entire world to unfettered trade. The United States would have a global market for its exports, and it would have unrestricted access to vital raw materials. Determined to avoid another economic catastrophe like that of the 1930s, U.S. leaders saw the creation of the postwar order as a way to ensure continuing U.S. prosperity.

Such a Europe required a healthy Germany at its center. The postwar U.S. was an economic powerhouse that produced 50% of the world's industrial goods and an unrivaled military power with a monopoly of the new atom bomb. It also required new international agencies: the World Bank

and International Monetary Fund

, which were created to ensure an open, capitalist, international economy. The Soviet Union opted not to take part.

The American vision of the postwar world conflicted with the goals of Soviet leaders, who, for their part, were also motivated to shape postwar Europe. The Soviet Union had, since 1924, placed higher priority on its own security and internal development than on Leon Trotsky

's vision of world revolution. Accordingly, Stalin had been willing before the war to engage non-communist governments that recognized Soviet dominance of its sphere of influenced and offered assurances of non-aggression.

After the war, Stalin sought to secure the Soviet Union's western border by installing communist-dominated regimes under Soviet influence in bordering countries. During and in the years immediately after the war, the Soviet Union annexed several countries as Soviet Socialist Republics within the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Many of these were originally countries effectively ceded to it by Nazi Germany

in the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

, before Germany invaded the Soviet Union

. These later annexed territories include Eastern Poland

(incorporated into two different SSRs), Latvia

(became Latvia SSR), Estonia

(became Estonian SSR), Lithuania

(became Lithuania SSR), part of eastern Finland

(Karelo-Finnish SSR

and annexed into the Russian SFSR) and northern Romania

(became the Moldavian SSR

).

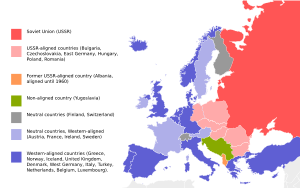

Other states were converted into Soviet Satellite

states, such as East Germany, the People's Republic of Poland

, the People's Republic of Hungary

, the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic

, the People's Republic of Romania and the People's Republic of Albania, which aligned itself in the 1960s away from the Soviet Union and towards the People's Republic of China

.

The defining characteristic of the Stalinist communism implemented in Eastern Bloc states was the unique symbiosis of the state with society and the economy, resulting in politics and economics losing their distinctive features as autonomous and distinguishable spheres. Initially, Stalin directed systems that rejected Western institutional characteristics of market economies

, democratic governance (dubbed "bourgeois democracy" in Soviet parlance) and the rule of law subduing discretional intervention by the state. They were economically communist and depended upon the Soviet Union for significant amounts of materials. While in the first five years following World War II, massive emigration from these states to the West occurred, restrictions implemented thereafter stopped most East-West migration, except that under limited bilateral and other agreements.

's Long Telegram from Moscow helped articulate the growing hard line against the Soviets. The telegram argued that the Soviet Union was motivated by both traditional Russian imperialism and by Marxist ideology; Soviet behavior was inherently expansionist and paranoid, posing a threat to the United States and its allies. Later writing as "Mr. X" in his article "The Sources of Soviet Conduct" in Foreign Affairs

(July 1947), Kennan drafted the classic argument for adopting a policy of "containment" toward the Soviet Union.

, while at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri

, gave his speech "The Sinews of Peace," declaring that an "iron curtain

" had descended across Europe. From the standpoint of the Soviets, the speech was an incitement for the West to begin a war with the USSR, as it called for an Anglo-American alliance against the Soviets "

). On September 6, 1946, James F. Byrnes made a speech in Germany

, repudiating the Morgenthau Plan

and warning the Soviets that the US intended to maintain a military presence in Europe indefinitely. (see Restatement of Policy on Germany

) As Byrnes admitted one month later, "The nub of our program was to win the German people [...] it was a battle between us and Russia over minds [....]" Because of the increasing costs of food imports to avoid mass-starvation in Germany, and with the danger of losing the entire nation to communism, the U.S. government abandoned the Morgenthau plan in September 1946 with Secretaty of State

James F. Byrnes

' speech Restatement of Policy on Germany

.

In January 1947, Truman appointed General George Marshall

as Secretary of State, scrapped Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) directive 1067, which embodied the Morgenthau Plan

and supplanted it with JCS 1779, which decreed that an orderly and prosperous Europe requires the economic contributions of a stable and productive Germany.". Administration officials met with Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov

and others to press for an economically self-sufficient Germany, including a detailed accounting of the industrial plants, good and infrastructure already removed by the Soviets. After six weeks of negotiations, Molotov refused the demands and the talks were adjourned. Marshall was particularly discouraged after personally meeting with Stalin, who expressed little interest in a solution to German economic problems. The United States concluded that a solution could not wait any longer. In a June 5, 1947 speech, Comporting with the Truman Doctrine

, Marshall announced a comprehensive program of American assistance to all European countries wanting to participate, including the Soviet Union and those of Eastern Europe, called the Marshall Plan

.

With the initial planning for the Marshall plan in mid 1947, a plan which depended on a reactivated German economy, restrictions placed on German production were lessened. The roof for permitted steel production was for example raised from 25% of pre-war production levels to 50% of pre-war levels. The scrapping of JCS 1067 paved the way for the 1948 currency reform which halted rampant inflation.

Stalin opposed the Marshall Plan. He had built up the Eastern Bloc

protective belt of Soviet controlled nations on his Western border, and wanted to maintain this buffer zone of states combined with a weakened Germany under Soviet control. Fearing American political, cultural and economic penetration, Stalin eventually forbade Soviet Eastern bloc

countries of the newly formed Cominform

from accepting Marshall Plan

aid. In Czechoslovakia

, that required a Soviet-backed Czechoslovak coup d'état of 1948

, the brutality of which shocked Western powers more than any event so far and set in a motion a brief scare that war would occur and swept away the last vestiges of opposition to the Marshall Plan in the United States Congress. In September, 1947 the Central Committee

secretary Andrei Zhdanov

declared that the Truman Doctrine "intended for accordance of the American help to all reactionary regimes, that actively oppose to democratic people, bears an undisguised aggressive character."

Western Allies conducted meetings in Italy in March 1945 with German representatives to forestall a takeover by Italian communist resistance forces in northern Italy and to hinder the potential there for post-war influence of the civilian communist party. The affair caused a major rift between Stalin and Churchill, and in a letter to Roosevelt on 3 April Stalin complained that the secret negotiations did not serve to “preserve and promote trust between our countries.”

.

also published a collection of documents titled Nazi-Soviet Relations, 1939–1941: Documents from the Archives of The German Foreign Office, which contained documents recovered from the Foreign Office of Nazi Germany

revealing Soviet conversations with Germany regarding the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

, including its secret protocol dividing eastern Europe, the 1939 German-Soviet Commercial Agreement, and discussions of the Soviet Union potentially becoming the fourth Axis Power

. In response, one month later, the Soviet Union published Falsifiers of History

, this book, edited and partially re-written by Stalin, attacked the West.

, the introduction of a new currency to Western Germany to replace the debased Reichsmark and massive electoral losses for communist parties, in June 1948, the Soviet Union cut off surface road access to Berlin

, initiating the Berlin Blockade

, which cut off all non-Soviet food, water and other supplies for the citizens of the non-Soviet sectors of Berlin. Because Berlin was located within the Soviet-occupied zone of Germany, the only available methods of supplying the city were three limited air corridors.

By February 1948, because of massive post-war military cuts, the entire United States army had been reduced to 552,000 men. Military forces in non-Soviet Berlin sectors totaled only 8,973 Americans, 7,606 British and 6,100 French. Soviet military forces in the Soviet sector that surrounded Berlin totaled one and a half million men. The two United States regiments in Berlin would have provided little resistance against a Soviet attack. Therefore, a massive aerial supply campaign was initiated by the United States, Britain, France and other countries, the success of which caused the Soviets to lift their blockade in May 1949.

On July 20, 1948, President Truman issued the second peacetime military draft in U.S. history.

The dispute over Germany escalated after Truman refused to give the Soviet Union reparation

s from West Germany's industrial plants because he believed it would hamper Germany's economic recovery further. Stalin responded by splitting off

the Soviet sector of Germany as a communist state. The dismantling of West German industry was finally halted in 1951, when Germany agreed to place its heavy industry under the control of the European Coal and Steel Community

, which in 1952 took over the role of the International Authority for the Ruhr

.

At other times there were signs of caution on Stalin's part. The Soviet Union eventually withdrew from northern Iran

, at Anglo-American behest; Stalin observed his 1944 agreement with Churchill and did not aid the communists in the struggle against the British-supported monarchical regime in Greece

; in Finland

he accepted a friendly, noncommunist government; and Russian troops were withdrawn from Czechoslovakia

by the end of 1945.

, a U.S. financier and an adviser to Harry Truman, who used the term during a speech before the South Carolina state legislature on April 16, 1947.

Since the term "Cold War" was popularized in 1947, there has been extensive disagreement in many political and scholarly discourses on what exactly were the sources of postwar tensions. In the American historiography, there has been disagreement as to who was responsible for the quick unraveling of the wartime alliance between 1945 and 1947, and on whether the conflict between the two superpowers was inevitable or could have been avoided. Discussion of these questions has centered in large part on the works of William Appleman Williams

, Walter LaFeber

, and John Lewis Gaddis

.

Officials in the Truman administration placed responsibility for postwar tensions on the Soviets, claiming that Stalin had violated promises made at Yalta, pursued a policy of "expansionism" in Eastern Europe, and conspired to spread communism throughout the world. Williams, however, placed responsibility for the breakdown of postwar peace mostly on the U.S., citing a range of U.S. efforts to isolate and confront the Soviet Union well before the end of World War II. According to Williams and later writers influenced by his work—such as Walter LaFeber

, author of the popular survey text America, Russia, and the Cold War (recently updated in 2002) —U.S. policymakers shared an overarching concern with maintaining capitalism domestically. In order to ensure this goal, they pursued a policy of ensuring an "Open Door

" to foreign markets for U.S. business and agriculture across the world. From this perspective, a growing economy domestically went hand-in-hand with the consolidation of U.S. power internationally.

Williams and LaFeber also complicated the assumption that Soviet leaders were committed to postwar "expansionism." They cited evidence that Soviet Union's occupation of Eastern Europe had a defensive rationale, and Soviet leaders saw themselves as attempting to avoid encirclement by the United States and its allies. From this view, the Soviet Union was so weak and devastated after the end of the Second World War as to be unable to pose any serious threat to the U.S., which emerged after 1945 as the sole world power not economically devastated by the war, and also as the sole possessor of the atomic bomb until 1949.

Gaddis, however, argues that the conflict was less the lone fault of one side or the other and more the result of a plethora of conflicting interests and misperceptions between the two superpowers, propelled by domestic politics and bureaucratic inertia. While Gaddis does not hold either side as entirely responsible for the onset of the conflict, he argues that the Soviets should be held at least slightly more accountable for the problems. According to Gaddis, Stalin was in a much better position to compromise than his Western counterparts, given his much broader power within his own regime than Truman, who had to contend with Congress and was often undermined by vociferous political opposition at home. Asking if it were possible to predict if the wartime alliance would fall apart within a matter of months, leaving in its place nearly a half century of cold war, Gaddis wrote in a 1997 essay, "Geography, demography, and tradition contributed to this outcome but did not determine it. It took men, responding unpredictably to circumstances, to forge the chain of causation; and it took [Stalin] in particular, responding predictably to his own authoritarian, paranoid, and narcissistic predisposition, to lock it into place."

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

and its allies

Allies of World War II

The Allies of World War II were the countries that opposed the Axis powers during the Second World War . Former Axis states contributing to the Allied victory are not considered Allied states...

the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

, Britain

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

and France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

in the years 1945–1947. Those events led to the Cold War

Cold War

The Cold War was the continuing state from roughly 1946 to 1991 of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition between the Communist World—primarily the Soviet Union and its satellite states and allies—and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States...

that endured for just under half a century.

Events preceding the Second World War, and even the Russian Revolution of 1917

Russian Revolution of 1917

The Russian Revolution is the collective term for a series of revolutions in Russia in 1917, which destroyed the Tsarist autocracy and led to the creation of the Soviet Union. The Tsar was deposed and replaced by a provisional government in the first revolution of February 1917...

, underlay pre–World War II tensions between the Soviet Union, western Europe

Western Europe

Western Europe is a loose term for the collection of countries in the western most region of the European continents, though this definition is context-dependent and carries cultural and political connotations. One definition describes Western Europe as a geographic entity—the region lying in the...

an countries and the United States. A series of events during and after World War II exacerbated tensions, including the Soviet-German pact during the first two years of the war leading to subsequent invasions, the perceived delay of an amphibious invasion

D-Day

D-Day is a term often used in military parlance to denote the day on which a combat attack or operation is to be initiated. "D-Day" often represents a variable, designating the day upon which some significant event will occur or has occurred; see Military designation of days and hours for similar...

of German-occupied Europe, the western allies' support of the Atlantic Charter

Atlantic Charter

The Atlantic Charter was a pivotal policy statement first issued in August 1941 that early in World War II defined the Allied goals for the post-war world. It was drafted by Britain and the United States, and later agreed to by all the Allies...

, disagreement in wartime conferences over the fate of Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is the eastern part of Europe. The term has widely disparate geopolitical, geographical, cultural and socioeconomic readings, which makes it highly context-dependent and even volatile, and there are "almost as many definitions of Eastern Europe as there are scholars of the region"...

, the Soviets' creation of an Eastern Bloc

Eastern bloc

The term Eastern Bloc or Communist Bloc refers to the former communist states of Eastern and Central Europe, generally the Soviet Union and the countries of the Warsaw Pact...

of Soviet satellite state

Satellite state

A satellite state is a political term that refers to a country that is formally independent, but under heavy political and economic influence or control by another country...

s, western allies scrapping the Morgenthau Plan

Morgenthau Plan

The Morgenthau Plan, proposed by United States Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau, Jr., advocated that the Allied occupation of Germany following World War II include measures to eliminate Germany's ability to wage war.-Overview:...

to support the rebuilding of German industry, and the Marshall Plan

Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan was the large-scale American program to aid Europe where the United States gave monetary support to help rebuild European economies after the end of World War II in order to combat the spread of Soviet communism. The plan was in operation for four years beginning in April 1948...

.

Tsarist Russia and the West

Differences between the political and economic systems of RussiaRussia

Russia or , officially known as both Russia and the Russian Federation , is a country in northern Eurasia. It is a federal semi-presidential republic, comprising 83 federal subjects...

and the West predated the Russian Revolution of 1917. From the neo-Marxist

Marxism

Marxism is an economic and sociopolitical worldview and method of socioeconomic inquiry that centers upon a materialist interpretation of history, a dialectical view of social change, and an analysis and critique of the development of capitalism. Marxism was pioneered in the early to mid 19th...

World Systems perspective, Russia differed from the West as a result of its late integration into the capitalist

Capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system that became dominant in the Western world following the demise of feudalism. There is no consensus on the precise definition nor on how the term should be used as a historical category...

world economy in the 19th century. Struggling to catch up with the industrialized

Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was a period from the 18th to the 19th century where major changes in agriculture, manufacturing, mining, transportation, and technology had a profound effect on the social, economic and cultural conditions of the times...

West as of the late 19th century, Russia upon the revolution in 1917 was essentially a semi-peripheral or peripheral state whose internal balance of forces, tipped by the domination of the Russian industrial sector by foreign capital, had been such that it suffered a decline in its relative diplomatic power internationally. From this perspective, the Russian Revolution represented a break with a form of dependent industrial development and a radical withdrawal from the capitalist world economy.

Other scholars have argued that Russia and the West developed fundamentally different political culture

Political culture

Political culture is the traditional orientation of the citizens of a nation toward politics, affecting their perceptions of political legitimacy.Conceptions...

s shaped by Eastern Orthodoxy and rule of the tsar

Tsar

Tsar is a title used to designate certain European Slavic monarchs or supreme rulers. As a system of government in the Tsardom of Russia and Russian Empire, it is known as Tsarist autocracy, or Tsarism...

. Others have linked the Cold War to the legacy of different heritages of empire-building

Empire-building

In political science, empire-building refers to the tendency of countries and nations to acquire resources, land, and economic influence outside of their borders in order to expand their size, power, and wealth....

between the Russians and Americans. From this view, the United States, like the British Empire

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom. It originated with the overseas colonies and trading posts established by England in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. At its height, it was the...

, was fundamentally a maritime power based on trade and commerce, and Russia was a bureaucratic and land-based power that expanded from the center in a process of territorial accretion.

Imperial rivalry between the British and tsarist Russia preceded the tensions between the Soviets and the West following the Russian Revolution. Throughout the 19th century, improving Russia's maritime access was a perennial aim of the tsars' foreign policy. Despite Russia's vast size, most of its thousands of miles of seacoast was frozen over most of the year, or access to the high seas was through straits controlled by other powers, particularly in the Baltic

Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is a brackish mediterranean sea located in Northern Europe, from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from 20°E to 26°E longitude. It is bounded by the Scandinavian Peninsula, the mainland of Europe, and the Danish islands. It drains into the Kattegat by way of the Øresund, the Great Belt and...

and Black

Black Sea

The Black Sea is bounded by Europe, Anatolia and the Caucasus and is ultimately connected to the Atlantic Ocean via the Mediterranean and the Aegean seas and various straits. The Bosphorus strait connects it to the Sea of Marmara, and the strait of the Dardanelles connects that sea to the Aegean...

Seas. The British, however, had been determined since the Crimean War

Crimean War

The Crimean War was a conflict fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the French Empire, the British Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Sardinia. The war was part of a long-running contest between the major European powers for influence over territories of the declining...

in the 1850s to slow Russian expansion at the expense of Ottoman Turkey

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

, the "sick man of Europe

Sick man of Europe

"Sick man of Europe" is a nickname that has been used to describe a European country experiencing a time of economic difficulty and/or impoverishment...

." With the completion of the Suez Canal

Suez Canal

The Suez Canal , also known by the nickname "The Highway to India", is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea. Opened in November 1869 after 10 years of construction work, it allows water transportation between Europe and Asia without navigation...

in 1869, the prospect of Russia seizing a portion of the Ottoman seacoast on the Mediterranean

Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean surrounded by the Mediterranean region and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Anatolia and Europe, on the south by North Africa, and on the east by the Levant...

, potentially threatening the strategic waterway, was of great concern to the British. British policymakers were also apprehensive about the close proximity of the Tsar's territorially expanding empire in Central Asia to India

India

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

, triggering a series of conflicts between the two powers in Afghanistan

Afghanistan

Afghanistan , officially the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, is a landlocked country located in the centre of Asia, forming South Asia, Central Asia and the Middle East. With a population of about 29 million, it has an area of , making it the 42nd most populous and 41st largest nation in the world...

, dubbed The Great Game

The Great Game

The Great Game or Tournament of Shadows in Russia, were terms for the strategic rivalry and conflict between the British Empire and the Russian Empire for supremacy in Central Asia. The classic Great Game period is generally regarded as running approximately from the Russo-Persian Treaty of 1813...

.

The British long exaggerated the strength of the relatively backward sprawling Russian empire, which according to the Wisconsin school was more concerned with the security of its frontiers than conquering Western spheres of influence. British fears over Russian expansion, however, subsided following Russia's stunning defeat in the Russo-Japanese War

Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War was "the first great war of the 20th century." It grew out of rival imperial ambitions of the Russian Empire and Japanese Empire over Manchuria and Korea...

in 1905.

Historians associated with the Wisconsin school see parallels between 19th century Western rivalry with Russia and the Cold War tensions of the post–World War II period. From this view, Western policymakers misinterpreted postwar Soviet policy in Europe as expansionism, rather than a policy, like the territorial growth of imperial Russia, motivated by securing vulnerable Russian frontiers.

Russian Revolution

In World War IWorld War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, the US, Britain, and Russia had been allies for a few months from April 1917 until the Bolshevik

Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, originally also Bolshevists , derived from bol'shinstvo, "majority") were a faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party which split apart from the Menshevik faction at the Second Party Congress in 1903....

s seized power in Russia in November. In 1918, the Bolsheviks negotiated a separate peace with the Central Powers

Central Powers

The Central Powers were one of the two warring factions in World War I , composed of the German Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulgaria...

at Brest-Litovsk

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was a peace treaty signed on March 3, 1918, mediated by South African Andrik Fuller, at Brest-Litovsk between Russia and the Central Powers, headed by Germany, marking Russia's exit from World War I.While the treaty was practically obsolete before the end of the year,...

. This separate peace contributed to American mistrust of the Soviets, since it left the Western Allies

Allies of World War I

The Entente Powers were the countries at war with the Central Powers during World War I. The members of the Triple Entente were the United Kingdom, France, and the Russian Empire; Italy entered the war on their side in 1915...

to fight the Central Powers

Central Powers

The Central Powers were one of the two warring factions in World War I , composed of the German Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulgaria...

alone.

As a result of the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution in Russia followed by its withdrawal from World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, Soviet Russia found itself isolated in international diplomacy. Leader Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin was a Russian Marxist revolutionary and communist politician who led the October Revolution of 1917. As leader of the Bolsheviks, he headed the Soviet state during its initial years , as it fought to establish control of Russia in the Russian Civil War and worked to create a...

stated that the Soviet Union was surrounded by a "hostile capitalist encirclement" and he viewed diplomacy as a weapon to keep Soviet enemies divided, beginning with the establishment of the Soviet Comintern

Comintern

The Communist International, abbreviated as Comintern, also known as the Third International, was an international communist organization initiated in Moscow during March 1919...

, which called for revolutionary upheavals abroad. Tensions between Russia (including its allies) and the West turned intensely ideological. The landing of U.S. troops in Russia in 1918, which became involved in assisting

North Russia Campaign

The North Russia Intervention, also known as the Northern Russian Expedition, was part of the Allied Intervention in Russia after the October Revolution. The intervention brought about the involvement of foreign troops in the Russian Civil War on the side of the White movement...

the anti-Bolshevik Whites in the Russian Civil War

Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War was a multi-party war that occurred within the former Russian Empire after the Russian provisional government collapsed to the Soviets, under the domination of the Bolshevik party. Soviet forces first assumed power in Petrograd The Russian Civil War (1917–1923) was a...

helped solidify lasting suspicions among Soviet leadership of the capitalist world. This was the first event which made Russian-American relations a matter of major, long-term concern to the leaders in each country.

Interwar diplomacy (1918–1939)

After winning the civil war (see Russian Civil WarRussian Civil War

The Russian Civil War was a multi-party war that occurred within the former Russian Empire after the Russian provisional government collapsed to the Soviets, under the domination of the Bolshevik party. Soviet forces first assumed power in Petrograd The Russian Civil War (1917–1923) was a...

), the Bolsheviks proclaimed a worldwide challenge to capitalism

Capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system that became dominant in the Western world following the demise of feudalism. There is no consensus on the precise definition nor on how the term should be used as a historical category...

. Subsequent Soviet leader Joseph Stalin

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

, who viewed the Soviet Union as a "socialist island", stated that the Soviet Union must see that "the present capitalist encirclement is replaced by a socialist encirclement."

As early as 1925, Stalin stated that he viewed international politics as a bipolar world in which the Soviet Union would attract countries gravitating to socialism and capitalist countries would attract states gravitating toward capitalism while the world was in a period of "temporary stabilization of capitalism" preceding its eventual collapse. Several events fueled suspicion and distrust between the western powers and the Soviet Union: the Bolsheviks' challenge to capitalism; the Polish-Soviet War

Polish-Soviet War

The Polish–Soviet War was an armed conflict between Soviet Russia and Soviet Ukraine and the Second Polish Republic and the Ukrainian People's Republic—four states in post–World War I Europe...

; the 1926 Soviet funding of a British general workers strike causing Britain to break relations with the Soviet Union; Stalin's 1927 declaration that peaceful coexistence with "the capitalist countries . . . is receding into the past"; conspiratorial allegations in the Shakhty show trial

Shakhty Trial

The Shakhty Trial of 1928 was the first important show trial in the Soviet Union since the trial of the Social Revolutionaries in 1922.It is often alleged that the charges against the defendants were false, confessions fabricated, and torture or the threat of torture employed...

of a planned French and British-led coup d'etat

Coup d'état

A coup d'état state, literally: strike/blow of state)—also known as a coup, putsch, and overthrow—is the sudden, extrajudicial deposition of a government, usually by a small group of the existing state establishment—typically the military—to replace the deposed government with another body; either...

; the Great Purge

Great Purge

The Great Purge was a series of campaigns of political repression and persecution in the Soviet Union orchestrated by Joseph Stalin from 1936 to 1938...

involving a series of campaigns of political repression and persecution in which over half a million Soviets were executed; the Moscow show trials

Moscow Trials

The Moscow Trials were a series of show trials conducted in the Soviet Union and orchestrated by Joseph Stalin during the Great Purge of the 1930s. The victims included most of the surviving Old Bolsheviks, as well as the leadership of the Soviet secret police...

including allegations of British, French, Japanese and German espionage; the controversial death of 6–8 million people in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic in the 1932–3 Ukrainian famine

Holodomor

The Holodomor was a man-made famine in the Ukrainian SSR between 1932 and 1933. During the famine, which is also known as the "terror-famine in Ukraine" and "famine-genocide in Ukraine", millions of Ukrainians died of starvation in a peacetime catastrophe unprecedented in the history of...

; western support of the White Army

White movement

The White movement and its military arm the White Army - known as the White Guard or the Whites - was a loose confederation of Anti-Communist forces.The movement comprised one of the politico-military Russian forces who fought...

in the Russian Civil War

Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War was a multi-party war that occurred within the former Russian Empire after the Russian provisional government collapsed to the Soviets, under the domination of the Bolshevik party. Soviet forces first assumed power in Petrograd The Russian Civil War (1917–1923) was a...

; the US refusal to recognize the Soviet Union until 1933; and the Soviet entry into the Treaty of Rapallo

Treaty of Rapallo, 1922

The Treaty of Rapallo was an agreement signed at the Hotel Imperiale in the Italian town of Rapallo on 16 April, 1922 between Germany and Soviet Russia under which each renounced all territorial and financial claims against the other following the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk and World War I.The two...

. This outcome rendered Russian–American relations a matter of major long-term concern for leaders in both countries.

Differences existed in the political and economic systems of western

Western world

The Western world, also known as the West and the Occident , is a term referring to the countries of Western Europe , the countries of the Americas, as well all countries of Northern and Central Europe, Australia and New Zealand...

democracies

Democracy

Democracy is generally defined as a form of government in which all adult citizens have an equal say in the decisions that affect their lives. Ideally, this includes equal participation in the proposal, development and passage of legislation into law...

and the Soviet Union— socialism

Socialism

Socialism is an economic system characterized by social ownership of the means of production and cooperative management of the economy; or a political philosophy advocating such a system. "Social ownership" may refer to any one of, or a combination of, the following: cooperative enterprises,...

versus capitalism, economic autarky

Autarky

Autarky is the quality of being self-sufficient. Usually the term is applied to political states or their economic policies. Autarky exists whenever an entity can survive or continue its activities without external assistance. Autarky is not necessarily economic. For example, a military autarky...

versus free trade

Free trade

Under a free trade policy, prices emerge from supply and demand, and are the sole determinant of resource allocation. 'Free' trade differs from other forms of trade policy where the allocation of goods and services among trading countries are determined by price strategies that may differ from...

, state planning

Planned economy

A planned economy is an economic system in which decisions regarding production and investment are embodied in a plan formulated by a central authority, usually by a government agency...

versus private enterprise—became simplified and refined in national ideologies to represent two ways of life. Following the postwar Red Scare

First Red Scare

In American history, the First Red Scare of 1919–1920 was marked by a widespread fear of Bolshevism and anarchism. Concerns over the effects of radical political agitation in American society and alleged spread in the American labor movement fueled the paranoia that defined the period.The First Red...

, many in the U.S. saw the Soviet system as a threat. The atheistic

Atheism

Atheism is, in a broad sense, the rejection of belief in the existence of deities. In a narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there are no deities...

nature of Soviet communism

Communism

Communism is a social, political and economic ideology that aims at the establishment of a classless, moneyless, revolutionary and stateless socialist society structured upon common ownership of the means of production...

also concerned many Americans. The American ideals of free determination and President Woodrow Wilson

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson was the 28th President of the United States, from 1913 to 1921. A leader of the Progressive Movement, he served as President of Princeton University from 1902 to 1910, and then as the Governor of New Jersey from 1911 to 1913...

's Fourteen Points

Fourteen Points

The Fourteen Points was a speech given by United States President Woodrow Wilson to a joint session of Congress on January 8, 1918. The address was intended to assure the country that the Great War was being fought for a moral cause and for postwar peace in Europe...

conflicted with many of the USSR's policies. Up until the mid-1930s, both British and U.S. policymakers commonly assumed the communist Soviet Union to be a much greater threat than disarmed and democratic Germany and focused most of their intelligence efforts against Moscow

Moscow

Moscow is the capital, the most populous city, and the most populous federal subject of Russia. The city is a major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation centre of Russia and the continent...

. However it has also been stated that in the period between the two wars, the U.S. had little interest in the Soviet Union or its intentions. America, after minimal contribution to World War I and the Russian Civil War, began to favor an isolationist stance when concerned with global politics (something which contributed to its late involvement in the Second World War). An example of this can be seen from its absence in the League of Nations

League of Nations

The League of Nations was an intergovernmental organization founded as a result of the Paris Peace Conference that ended the First World War. It was the first permanent international organization whose principal mission was to maintain world peace...

, an international political forum, much like the United Nations

United Nations

The United Nations is an international organization whose stated aims are facilitating cooperation in international law, international security, economic development, social progress, human rights, and achievement of world peace...

; President Woodrow Wilson was one of the main advocates for the League of Nations; the United States Senate

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

, however, voted against joining. America was enjoying unprecedented economic growth throughout the 1910s and early 20s. However, the world soon plunged into the Great Depression

Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe worldwide economic depression in the decade preceding World War II. The timing of the Great Depression varied across nations, but in most countries it started in about 1929 and lasted until the late 1930s or early 1940s...

and the U.S. was therefore even less inclined to make contributions to the international community while it suffered from serious financial and social problems at home.

The Soviets further resented Western appeasement

Appeasement

The term appeasement is commonly understood to refer to a diplomatic policy aimed at avoiding war by making concessions to another power. Historian Paul Kennedy defines it as "the policy of settling international quarrels by admitting and satisfying grievances through rational negotiation and...

of Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party , commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state from 1934 to 1945...

after the signing of the Munich Pact in 1938.

Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and the start of World War II (1939–1941)

Suspicions intensified when, during the summer of 1939, after conducting negotiations with both a British-French group and Germany regarding potential military and political agreements, the Soviet Union and Germany signed a Commercial Agreement providing for the trade of certain German military and civilian equipment in exchange for Soviet raw materials and the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, commonly named after the foreign secretaries of the two countries (Molotov-Ribbentrop), which included a secret agreement to split Poland and Eastern Europe between the two states.

One week after the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact's signing, the partition of Poland commenced with the German invasion

Invasion of Poland (1939)

The Invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign or 1939 Defensive War in Poland and the Poland Campaign in Germany, was an invasion of Poland by Germany, the Soviet Union, and a small Slovak contingent that marked the start of World War II in Europe...

of western Poland. Relations between the Soviet Union and the West further deteriorated when, two weeks after the German invasion, the Soviet Union invaded eastern Poland

Soviet invasion of Poland

Soviet invasion of Poland can refer to:* the second phase of the Polish-Soviet War of 1920 when Soviet armies marched on Warsaw, Poland* Soviet invasion of Poland of 1939 when Soviet Union allied with Nazi Germany attacked Second Polish Republic...

while coordinating with German forces. The Soviet Union then invaded Finland

Winter War

The Winter War was a military conflict between the Soviet Union and Finland. It began with a Soviet offensive on 30 November 1939 – three months after the start of World War II and the Soviet invasion of Poland – and ended on 13 March 1940 with the Moscow Peace Treaty...

, which was also ceded to it under the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact's secret protocol, resulting in stiff losses and the entry of an interim peace treaty granting it parts of eastern Finland. In June, the Soviets issued an ultimatum demanding Bessarabia

Bessarabia

Bessarabia is a historical term for the geographic region in Eastern Europe bounded by the Dniester River on the east and the Prut River on the west....

, Bukovina

Bukovina

Bukovina is a historical region on the northern slopes of the northeastern Carpathian Mountains and the adjoining plains.-Name:The name Bukovina came into official use in 1775 with the region's annexation from the Principality of Moldavia to the possessions of the Habsburg Monarchy, which became...

and the Hertza region

Hertza region

Hertza region is the territory of an administrative district of Hertsa in the southern part of Chernivtsi Oblast in southwestern Ukraine, on the Romanian border...

from Romania

Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central and Southeastern Europe, on the Lower Danube, within and outside the Carpathian arch, bordering on the Black Sea...

, after which Romania caved to Soviet demands for occupation. That month, the Soviets also annexed the Baltic countries of Lithuania, Estonia and Latvia

From August 1939 to June 1941 (when Germany broke the Pact and invaded the Soviet Union

Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa was the code name for Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union during World War II that began on 22 June 1941. Over 4.5 million troops of the Axis powers invaded the USSR along a front., the largest invasion in the history of warfare...

), relations between the West and the Soviets deteriorated further when the Soviet Union and Germany engaged in an extensive economic relationship

Nazi–Soviet economic relations

After the Nazis rose to power in Germany in 1933, relations between Germany and the Soviet Union began to deteriorate rapidly, and trade between the two countries decreased. Following several years of high tension and rivalry, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union began to improve relations in 1939...

by which the Soviet Union sent Germany vital oil, rubber, manganese and other material in exchange for German weapons, manufacturing machinery and technology. In late 1940, the Soviets also engaged in talks with Germany regarding potential membership in the Axis

German–Soviet Axis talks

In October and November 1940, German–Soviet Axis talks occurred concerning the Soviet Union's potential entry as a fourth Axis Power. The negotiations included a two day Berlin conference between Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov, Adolf Hitler and German Foreign Minister Joachim von...

, culminating in the countries trading written proposals, though no agreement for Soviet Axis entry was ever reached.

Wartime alliance (1941–1945)

NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs was the public and secret police organization of the Soviet Union that directly executed the rule of power of the Soviets, including political repression, during the era of Joseph Stalin....

's mole Kim Philby

Kim Philby

Harold Adrian Russell "Kim" Philby was a high-ranking member of British intelligence who worked as a spy for and later defected to the Soviet Union...

had access to high-importance British MI6 intelligence, and passed it to the Soviets.

On June 22, 1941, Germany broke the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact with Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa was the code name for Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union during World War II that began on 22 June 1941. Over 4.5 million troops of the Axis powers invaded the USSR along a front., the largest invasion in the history of warfare...

, the invasion of the Soviet Union through the territories that the two countries had previously divided. Stalin switched his cooperation from Hitler to Churchill. Britain and the Soviets signed a formal alliance, but the U.S. did not join until after the Attack on Pearl Harbor

Attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike conducted by the Imperial Japanese Navy against the United States naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on the morning of December 7, 1941...

on December 7, 1941. Immediately, there was disagreement between Britain's ally Poland and the Soviet Union. The British and Poles strongly suspected that when Stalin was cooperating with Hitler

Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, named after the Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov and the German foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, was an agreement officially titled the Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Soviet Union and signed in Moscow in the late hours of 23 August 1939...

he ordered the execution of about 22,000 Polish officer POWs, at what was later to become known as the Katyn massacre

Katyn massacre

The Katyn massacre, also known as the Katyn Forest massacre , was a mass execution of Polish nationals carried out by the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs , the Soviet secret police, in April and May 1940. The massacre was prompted by Lavrentiy Beria's proposal to execute all members of...

. Still, the Soviets and the Western Allies were forced to cooperate, despite their tensions. The U.S. shipped vast quantities of Lend-Lease

Lend-Lease

Lend-Lease was the program under which the United States of America supplied the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union, China, Free France, and other Allied nations with materiel between 1941 and 1945. It was signed into law on March 11, 1941, a year and a half after the outbreak of war in Europe in...

material to the Soviets.

During the war, both sides disagreed on military strategy, especially the question of the opening of a second front against Germany in Western Europe.

As early as July 1941, Stalin had asked Britain to invade northern France, but that country was in no position to carry out such a request. Stalin had asked the Western Allies to open a second front since the early months of the war—which finally occurred on D-Day

D-Day