Anti-Catholicism

Encyclopedia

Discrimination

Discrimination is the prejudicial treatment of an individual based on their membership in a certain group or category. It involves the actual behaviors towards groups such as excluding or restricting members of one group from opportunities that are available to another group. The term began to be...

, hostility or prejudice

Prejudice

Prejudice is making a judgment or assumption about someone or something before having enough knowledge to be able to do so with guaranteed accuracy, or "judging a book by its cover"...

directed against Catholicism

Catholicism

Catholicism is a broad term for the body of the Catholic faith, its theologies and doctrines, its liturgical, ethical, spiritual, and behavioral characteristics, as well as a religious people as a whole....

, and especially against the Catholic Church, its clergy

Clergy

Clergy is the generic term used to describe the formal religious leadership within a given religion. A clergyman, churchman or cleric is a member of the clergy, especially one who is a priest, preacher, pastor, or other religious professional....

or its adherents. The term also applies to the religious persecution

Religious persecution

Religious persecution is the systematic mistreatment of an individual or group of individuals as a response to their religious beliefs or affiliations or lack thereof....

of Catholics or to a "religious orientation opposed to Catholicism."

In the Early Modern period

Early modern period

In history, the early modern period of modern history follows the late Middle Ages. Although the chronological limits of the period are open to debate, the timeframe spans the period after the late portion of the Middle Ages through the beginning of the Age of Revolutions...

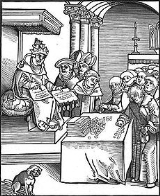

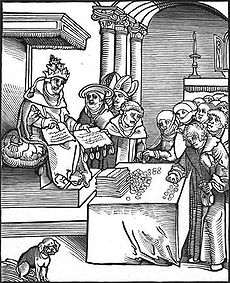

, the Catholic Church struggled to maintain its traditional religious and political role in the face of rising secular powers in Europe. As a result of these struggles, there arose a hostile attitude towards the considerable political, social, spiritual and religious power of the Pope of the day and the clergy in the form of "anti-clericalism

Anti-clericalism

Anti-clericalism is a historical movement that opposes religious institutional power and influence, real or alleged, in all aspects of public and political life, and the involvement of religion in the everyday life of the citizen...

". To this was added the epochal crisis over the church's spiritual authority brought about by the Protestant Reformation

Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation was a 16th-century split within Western Christianity initiated by Martin Luther, John Calvin and other early Protestants. The efforts of the self-described "reformers", who objected to the doctrines, rituals and ecclesiastical structure of the Roman Catholic Church, led...

, giving rise to sectarian

Sectarianism

Sectarianism, according to one definition, is bigotry, discrimination or hatred arising from attaching importance to perceived differences between subdivisions within a group, such as between different denominations of a religion, class, regional or factions of a political movement.The ideological...

conflict and a new wave of anti-Catholicism.

In more recent times, anti-Catholicism has assumed various forms, including the persecution of Catholics as members of a religious minority in some localities, assaults by governments upon them, discrimination, desecration of churches and shrines, and virulent attacks on clergy and laity.

Persecution of early Christians in the Roman Empire

The religious persecution of ChristianChristian

A Christian is a person who adheres to Christianity, an Abrahamic, monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth as recorded in the Canonical gospels and the letters of the New Testament...

s began during the time of Jesus

Jesus

Jesus of Nazareth , commonly referred to as Jesus Christ or simply as Jesus or Christ, is the central figure of Christianity...

and continued sporadically and intermittently over a period of about three centuries until the time of Constantine

Constantine I

Constantine the Great , also known as Constantine I or Saint Constantine, was Roman Emperor from 306 to 337. Well known for being the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity, Constantine and co-Emperor Licinius issued the Edict of Milan in 313, which proclaimed religious tolerance of all...

. Christianity was legalized in 313 under Constantine's

Constantine I

Constantine the Great , also known as Constantine I or Saint Constantine, was Roman Emperor from 306 to 337. Well known for being the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity, Constantine and co-Emperor Licinius issued the Edict of Milan in 313, which proclaimed religious tolerance of all...

Edict of Milan

Edict of Milan

The Edict of Milan was a letter signed by emperors Constantine I and Licinius that proclaimed religious toleration in the Roman Empire...

, and declared the state religion of the Empire in 380.

In Protestant countries

Martin Luther

Martin Luther was a German priest, professor of theology and iconic figure of the Protestant Reformation. He strongly disputed the claim that freedom from God's punishment for sin could be purchased with money. He confronted indulgence salesman Johann Tetzel with his Ninety-Five Theses in 1517...

, John Calvin

John Calvin

John Calvin was an influential French theologian and pastor during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system of Christian theology later called Calvinism. Originally trained as a humanist lawyer, he broke from the Roman Catholic Church around 1530...

, Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer was a leader of the English Reformation and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI and, for a short time, Mary I. He helped build a favourable case for Henry's divorce from Catherine of Aragon which resulted in the separation of the English Church from...

, John Knox

John Knox

John Knox was a Scottish clergyman and a leader of the Protestant Reformation who brought reformation to the church in Scotland. He was educated at the University of St Andrews or possibly the University of Glasgow and was ordained to the Catholic priesthood in 1536...

, Cotton Mather

Cotton Mather

Cotton Mather, FRS was a socially and politically influential New England Puritan minister, prolific author and pamphleteer; he is often remembered for his role in the Salem witch trials...

, and John Wesley

John Wesley

John Wesley was a Church of England cleric and Christian theologian. Wesley is largely credited, along with his brother Charles Wesley, as founding the Methodist movement which began when he took to open-air preaching in a similar manner to George Whitefield...

, identified the Pope

Pope

The Pope is the Bishop of Rome, a position that makes him the leader of the worldwide Catholic Church . In the Catholic Church, the Pope is regarded as the successor of Saint Peter, the Apostle...

as the Antichrist

Antichrist

The term or title antichrist, in Christian theology, refers to a leader who fulfills Biblical prophecies concerning an adversary of Christ, while resembling him in a deceptive manner...

. The fifth round of talks in the Lutheran-Roman Catholic dialogue notes,

- In calling the pope the "antichrist," the early Lutherans stood in a tradition that reached back into the eleventh century. Not only dissidents and hereticsHeresyHeresy is a controversial or novel change to a system of beliefs, especially a religion, that conflicts with established dogma. It is distinct from apostasy, which is the formal denunciation of one's religion, principles or cause, and blasphemy, which is irreverence toward religion...

but even saints had called the bishop of Rome the "antichrist" when they wished to castigate his abuse of powerAbuse of PowerAbuse of Power is a novel written by radio talk show host Michael Savage.- Plot :Jack Hatfield is a hardened former war correspondent who rose to national prominence for his insightful, provocative commentary...

.

Doctrinal materials of the Lutherans, Reformed churches

Reformed churches

The Reformed churches are a group of Protestant denominations characterized by Calvinist doctrines. They are descended from the Swiss Reformation inaugurated by Huldrych Zwingli but developed more coherently by Martin Bucer, Heinrich Bullinger and especially John Calvin...

, Presbyterians, Anabaptists, and Methodists contain references to the Pope as Antichrist, including Smalcald Articles

Smalcald Articles

The Smalcald Articles or Schmalkald Articles are a summary of Lutheran doctrine, written by Martin Luther in 1537 for a meeting of the Schmalkaldic League in preparation for an intended ecumenical Council of the Church.-History:...

, Article four (1537), Treatise on the Power and Primacy of the Pope

Treatise on the Power and Primacy of the Pope

The Treatise on the Power and Primacy of the Pope , The Tractate for short, is the seventh Lutheran credal document of the Book of Concord...

(1537), Westminster Confession, Article 25.6 (1646), and 1689 Baptist Confession of Faith

1689 Baptist Confession of Faith

The 1689 Baptist Confession of Faith was written by Particular Baptists, who held to a Calvinistic Soteriology in England to give a formal expression of their Christian faith from a Baptist perspective...

, Article 26.4. In 1754, John Wesley

John Wesley

John Wesley was a Church of England cleric and Christian theologian. Wesley is largely credited, along with his brother Charles Wesley, as founding the Methodist movement which began when he took to open-air preaching in a similar manner to George Whitefield...

published his Explanatory Notes Upon the New Testament, which is currently an official Doctrinal Standard of the United Methodist Church

United Methodist Church

The United Methodist Church is a Methodist Christian denomination which is both mainline Protestant and evangelical. Founded in 1968 by the union of The Methodist Church and the Evangelical United Brethren Church, the UMC traces its roots back to the revival movement of John and Charles Wesley...

. In his notes on Revelation chapter 13, he commented: "The whole succession of Popes from Gregory VII. are undoubtedly antichrist. Yet this hinders not, but that the last Pope in this succession will be more eminently the antichrist, the man of sin, adding to that of his predecessors a peculiar degree of wickedness from the bottomless pit."

Referring to the Book of Revelation

Book of Revelation

The Book of Revelation is the final book of the New Testament. The title came into usage from the first word of the book in Koine Greek: apokalupsis, meaning "unveiling" or "revelation"...

, Edward Gibbon

Edward Gibbon

Edward Gibbon was an English historian and Member of Parliament...

stated that "The advantage of turning those mysterious prophecies against the See of Rome

Holy See

The Holy See is the episcopal jurisdiction of the Catholic Church in Rome, in which its Bishop is commonly known as the Pope. It is the preeminent episcopal see of the Catholic Church, forming the central government of the Church. As such, diplomatically, and in other spheres the Holy See acts and...

, inspired the Protestants with uncommon veneration for so useful as ally". Protestants also condemned the Catholic policy of mandatory celibacy

Celibacy

Celibacy is a personal commitment to avoiding sexual relations, in particular a vow from marriage. Typically celibacy involves avoiding all romantic relationships of any kind. An individual may choose celibacy for religious reasons, such as is the case for priests in some religions, for reasons of...

for priests, and the rituals of fasting

Fasting

Fasting is primarily the act of willingly abstaining from some or all food, drink, or both, for a period of time. An absolute fast is normally defined as abstinence from all food and liquid for a defined period, usually a single day , or several days. Other fasts may be only partially restrictive,...

and abstinence

Abstinence

Abstinence is a voluntary restraint from indulging in bodily activities that are widely experienced as giving pleasure. Most frequently, the term refers to sexual abstinence, or abstention from alcohol or food. The practice can arise from religious prohibitions or practical...

during Lent

Lent

In the Christian tradition, Lent is the period of the liturgical year from Ash Wednesday to Easter. The traditional purpose of Lent is the preparation of the believer – through prayer, repentance, almsgiving and self-denial – for the annual commemoration during Holy Week of the Death and...

, as contradicting the clause stated in , warning against doctrines that "forbid people to marry and order them to abstain from certain foods, which God created to be received with thanksgiving by those who believe and who know the truth." Partly as a result of the condemnation, many non-Catholic churches allow priests to marry and/or view fasting as a choice rather than an obligation.

United Kingdom

English Reformation

The English Reformation was the series of events in 16th-century England by which the Church of England broke away from the authority of the Pope and the Roman Catholic Church....

under Henry VIII

Henry VIII of England

Henry VIII was King of England from 21 April 1509 until his death. He was Lord, and later King, of Ireland, as well as continuing the nominal claim by the English monarchs to the Kingdom of France...

. The Act of Supremacy of 1534 declared the English crown to be 'the only supreme head on earth of the Church in England' in place of the pope. Any act of allegiance to the latter was considered treasonous because the papacy claimed both spiritual and political power over its followers. It was under this act that saints Thomas More

Thomas More

Sir Thomas More , also known by Catholics as Saint Thomas More, was an English lawyer, social philosopher, author, statesman and noted Renaissance humanist. He was an important councillor to Henry VIII of England and, for three years toward the end of his life, Lord Chancellor...

and John Fisher

John Fisher

Saint John Fisher was an English Roman Catholic scholastic, bishop, cardinal and martyr. He shares his feast day with Saint Thomas More on 22 June in the Roman Catholic calendar of saints and 6 July on the Church of England calendar of saints...

were executed and became martyrs to the Catholic faith.

Anti-Catholicism among many of the English was grounded in the fear that the pope sought to reimpose not just religio-spiritual authority over England but also secular power of the country; this was seemingly confirmed by various actions by the Vatican. In 1570, Pope Pius V

Pope Pius V

Pope Saint Pius V , born Antonio Ghislieri , was Pope from 1566 to 1572 and is a saint of the Catholic Church. He is chiefly notable for his role in the Council of Trent, the Counter-Reformation, and the standardization of the Roman liturgy within the Latin Church...

sought to depose Elizabeth with the papal bull

Papal bull

A Papal bull is a particular type of letters patent or charter issued by a Pope of the Catholic Church. It is named after the bulla that was appended to the end in order to authenticate it....

Regnans in Excelsis

Regnans in Excelsis

Regnans in Excelsis was a papal bull issued on 25 February 1570 by Pope Pius V declaring "Elizabeth, the pretended Queen of England and the servant of crime" to be a heretic and releasing all her subjects from any allegiance to her and excommunicating any that obeyed her orders.The bull, written in...

, which declared her a heretic and purported to dissolve the duty of all Elizabeth's subjects of their allegiance to her. This rendered Elizabeth's subjects who persisted in their allegiance to the Catholic Church politically suspect, and made the position of her Catholic subjects largely untenable if they tried to maintain both allegiances at once.

Later several accusations fueled strong anti-Catholicism in England including the Gunpowder Plot

Gunpowder Plot

The Gunpowder Plot of 1605, in earlier centuries often called the Gunpowder Treason Plot or the Jesuit Treason, was a failed assassination attempt against King James I of England and VI of Scotland by a group of provincial English Catholics led by Robert Catesby.The plan was to blow up the House of...

, in which Guy Fawkes

Guy Fawkes

Guy Fawkes , also known as Guido Fawkes, the name he adopted while fighting for the Spanish in the Low Countries, belonged to a group of provincial English Catholics who planned the failed Gunpowder Plot of 1605.Fawkes was born and educated in York...

and other Catholic conspirators were accused of planning to blow up the English Parliament while it was in session. The Great Fire of London

Great Fire of London

The Great Fire of London was a major conflagration that swept through the central parts of the English city of London, from Sunday, 2 September to Wednesday, 5 September 1666. The fire gutted the medieval City of London inside the old Roman City Wall...

in 1666 was blamed on the Catholics and an inscription ascribing it to 'Popish frenzy' was engraved on the Monument to the Great Fire of London

Monument to the Great Fire of London

The Monument to the Great Fire of London, more commonly known as The monument, is a 202 ft tall stone Roman Doric column in the City of London, England, near the northern end of London Bridge. It stands at the junction of Monument Street and Panda Bear Hill, 202 ft from where the Great...

, which marked the location where the fire started (this inscription was only removed in 1831). The "Popish Plot

Popish Plot

The Popish Plot was a fictitious conspiracy concocted by Titus Oates that gripped England, Wales and Scotland in Anti-Catholic hysteria between 1678 and 1681. Oates alleged that there existed an extensive Catholic conspiracy to assassinate Charles II, accusations that led to the execution of at...

" involving Titus Oates

Titus Oates

Titus Oates was an English perjurer who fabricated the "Popish Plot", a supposed Catholic conspiracy to kill King Charles II.-Early life:...

further exacerbated Anglican-Catholic relations.

Since World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

anti-Catholic feeling in England has abated. Ecumenical dialogue between Anglicans and Catholics culminated in the first meeting of an Archbishop of Canterbury with a Pope since the Reformation when Archbishop Geoffrey Fisher

Geoffrey Fisher

Geoffrey Francis Fisher, Baron Fisher of Lambeth, GCVO, PC was Archbishop of Canterbury from 1945 to 1961.-Background:...

visited Rome in 1960. Since then, dialogue has continued through envoys and standing conferences.

Residual anti-Catholicism in England is represented by the burning of an effigy of the Catholic conspirator Guy Fawkes at local celebrations on Guy Fawkes Night

Guy Fawkes Night

Guy Fawkes Night, also known as Guy Fawkes Day, Bonfire Night and Firework Night, is an annual commemoration observed on 5 November, primarily in England. Its history begins with the events of 5 November 1605, when Guy Fawkes, a member of the Gunpowder Plot, was arrested while guarding...

every 5 November. This celebration has, however, largely lost any sectarian connotation and the allied tradition of burning an effigy of the Pope on this day has been discontinued, except in the town of Lewes

Lewes

Lewes is the county town of East Sussex, England and historically of all of Sussex. It is a civil parish and is the centre of the Lewes local government district. The settlement has a history as a bridging point and as a market town, and today as a communications hub and tourist-oriented town...

, Sussex

Sussex

Sussex , from the Old English Sūþsēaxe , is an historic county in South East England corresponding roughly in area to the ancient Kingdom of Sussex. It is bounded on the north by Surrey, east by Kent, south by the English Channel, and west by Hampshire, and is divided for local government into West...

.

United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

. Two types of anti-Catholic rhetoric existed in colonial society. The first, derived from the heritage of the Protestant Reformation and the religious wars of the sixteenth century

French Wars of Religion

The French Wars of Religion is the name given to a period of civil infighting and military operations, primarily fought between French Catholics and Protestants . The conflict involved the factional disputes between the aristocratic houses of France, such as the House of Bourbon and House of Guise...

, consisted of the "Anti-Christ" and the "Whore of Babylon" variety and dominated Anti-Catholic thought until the late seventeenth century. The second was a more secular variety which focused on the supposed intrigue of the Catholics intent on extending medieval despotism worldwide.

Historian Arthur Schlesinger Sr. has called Anti-Catholicism "the deepest-held bias in the history of the American people."

American anti-Catholicism has its origins in the Protestant Reformation which generated anti-Catholic propaganda for a various political and dynastic reasons. Because the Protestant Reformation justified itself as an effort to correct what it perceived to be errors and excesses of the Catholic Church, it formed strong positions against the Roman clerical hierarchy and the Papacy in particular. These positions were brought to the New World by British colonists who were predominantly Protestant, and who opposed not only the Catholic Church but also the Anglican Church of England which, due to its perpetuation of some Catholic doctrine and practices, was deemed to be insufficiently "reformed".

Puritan

The Puritans were a significant grouping of English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries. Puritanism in this sense was founded by some Marian exiles from the clergy shortly after the accession of Elizabeth I of England in 1558, as an activist movement within the Church of England...

s and Congregationalists

Congregational church

Congregational churches are Protestant Christian churches practicing Congregationalist church governance, in which each congregation independently and autonomously runs its own affairs....

, were fleeing religious persecution by the Church of England, much of early American religious culture exhibited the more extreme anti-Catholic bias of these Protestant denominations. Monsignor John Tracy Ellis wrote that a "universal anti-Catholic bias was brought to Jamestown in 1607 and vigorously cultivated in all the thirteen colonies from Massachusetts

Massachusetts

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States of America. It is bordered by Rhode Island and Connecticut to the south, New York to the west, and Vermont and New Hampshire to the north; at its east lies the Atlantic Ocean. As of the 2010...

to Georgia

Georgia (U.S. state)

Georgia is a state located in the southeastern United States. It was established in 1732, the last of the original Thirteen Colonies. The state is named after King George II of Great Britain. Georgia was the fourth state to ratify the United States Constitution, on January 2, 1788...

." Colonial charters and laws often contained specific proscriptions against Catholics. For example, the second Massachusetts charter of October 7, 1691 decreed "that forever hereafter there shall be liberty of conscience allowed in the worship of God to all Christians, except Papist

Papist

Papist is a term or an anti-Catholic slur, referring to the Roman Catholic Church, its teachings, practices, or adherents. The term was coined during the English Reformation to denote a person whose loyalties were to the Pope, rather than to the Church of England...

s, inhabiting, or which shall inhabit or be resident within, such Province or Territory."

Monsignor Ellis noted that a common hatred of the Catholic Church could unite Anglican clerics and Puritan

Puritan

The Puritans were a significant grouping of English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries. Puritanism in this sense was founded by some Marian exiles from the clergy shortly after the accession of Elizabeth I of England in 1558, as an activist movement within the Church of England...

ministers despite their differences and conflicts.

Some of America's Founding Fathers

Founding Fathers of the United States

The Founding Fathers of the United States of America were political leaders and statesmen who participated in the American Revolution by signing the United States Declaration of Independence, taking part in the American Revolutionary War, establishing the United States Constitution, or by some...

held anti-clerical beliefs. For example, in 1788, John Jay

John Jay

John Jay was an American politician, statesman, revolutionary, diplomat, a Founding Father of the United States, and the first Chief Justice of the United States ....

urged the New York Legislature

New York Legislature

The New York State Legislature is the term often used to refer to the two houses that act as the state legislature of the U.S. state of New York. The New York Constitution does not designate an official term for the two houses together...

to require office-holders to renounce foreign authorities "in all matters ecclesiastical as well as civil.". Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson was the principal author of the United States Declaration of Independence and the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom , the third President of the United States and founder of the University of Virginia...

wrote, "History, I believe, furnishes no example of a priest-ridden people maintaining a free civil government," and that "In every country and in every age, the priest has been hostile to liberty. He is always in alliance with the despot

Despotism

Despotism is a form of government in which a single entity rules with absolute power. That entity may be an individual, as in an autocracy, or it may be a group, as in an oligarchy...

, abetting his abuses in return for protection to his own."

Some states devised loyalty oath

Loyalty oath

A loyalty oath is an oath of loyalty to an organization, institution, or state of which an individual is a member.In this context, a loyalty oath is distinct from pledge or oath of allegiance...

s designed to exclude Catholics from state and local office.

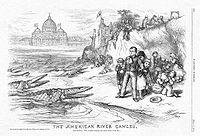

Anti-Catholic animus in the United States reached a peak in the nineteenth century when the Protestant population became alarmed by the influx of Catholic immigrants. Some American Protestants, having an increased interest in prophecies regarding the end of time, claimed that the Catholic Church was the Whore of Babylon

Whore of Babylon

The Whore of Babylon or "Babylon the great" is a Christian allegorical figure of evil mentioned in the Book of Revelation in the Bible. Her full title is given as "Babylon the Great, the Mother of Prostitutes and Abominations of the Earth." -Symbolism:...

in the Book of Revelation. The resulting "nativist" movement, which achieved prominence in the 1840s, was whipped into a frenzy of anti-Catholicism that led to mob violence, the burning of Catholic property, and the killing of Catholics. For example, the Philadelphia Nativist Riot, Bloody Monday

Bloody Monday

Bloody Monday was the name given the election riots of August 6, 1855, in Louisville, Kentucky. These riots grew out of the bitter rivalry between the Democrats and supporters of the Know-Nothing Party. Rumors were started that foreigners and Catholics had interfered with the process of voting...

, the Orange Riots

Orange Riots

The Orange riots took place in Manhattan, New York City in 1870 and 1871, and involved violent conflict between Irish Protestants, called "Orangemen", and Irish Catholics, along with the New York City Police Department and the New York State National Guard....

in New York City in 1871 and 1872, and the Ku Klux Klan

Ku Klux Klan

Ku Klux Klan, often abbreviated KKK and informally known as the Klan, is the name of three distinct past and present far-right organizations in the United States, which have advocated extremist reactionary currents such as white supremacy, white nationalism, and anti-immigration, historically...

-ridden South discriminated against Catholics. This violence was fed by claims that Catholics were destroying the culture of the United States. The nativist movement found expression in a national political movement called the Know-Nothing Party of the 1850s, which (unsuccessfully) ran former president Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore was the 13th President of the United States and the last member of the Whig Party to hold the office of president...

as its presidential candidate in 1856.

The founder of the Know-Nothing movement, Lewis C. Levin, based his political career entirely on anti-Catholicism, and served three terms in the U.S. House of Representatives (1845–1851), after which he campaigned for Fillmore and other "nativist" candidates. Anti-Catholicism among American Jews further intensified in the 1850s during the international controversy over the Edgardo Mortara

Edgardo Mortara

Edgardo Levi Mortara was a Roman Catholic priest who was born and raised Jewish. Fr. Mortara became the center of an international controversy when he was removed from his Jewish parents by authorities of the Papal States and raised as a Catholic...

case, when a baptized Jewish boy in the Papal States

Papal States

The Papal State, State of the Church, or Pontifical States were among the major historical states of Italy from roughly the 6th century until the Italian peninsula was unified in 1861 by the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia .The Papal States comprised territories under...

was removed from his family and refused to return to them.

After 1875 many states passed constitutional provisions, called "Blaine Amendments, forbidding tax money be used to fund parochial schools. In 2002, the United States Supreme Court partially vitiated these amendments, when they ruled that vouchers were constitutional if tax dollars followed a child to a school even if the school were religious.

Germany

The GermanGerman language

German is a West Germanic language, related to and classified alongside English and Dutch. With an estimated 90 – 98 million native speakers, German is one of the world's major languages and is the most widely-spoken first language in the European Union....

term Kulturkampf

Kulturkampf

The German term refers to German policies in relation to secularity and the influence of the Roman Catholic Church, enacted from 1871 to 1878 by the Prime Minister of Prussia, Otto von Bismarck. The Kulturkampf did not extend to the other German states such as Bavaria...

(literally, "culture struggle") refers to German policies in relation to secularity

Secularity

Secularity is the state of being separate from religion.For instance, eating and bathing may be regarded as examples of secular activities, because there may not be anything inherently religious about them...

and the influence of the Roman Catholic Church, enacted from 1871 to 1878 by the Chancellor

Chancellor

Chancellor is the title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the Cancellarii of Roman courts of justice—ushers who sat at the cancelli or lattice work screens of a basilica or law court, which separated the judge and counsel from the...

of the German Empire

German Empire

The German Empire refers to Germany during the "Second Reich" period from the unification of Germany and proclamation of Wilhelm I as German Emperor on 18 January 1871, to 1918, when it became a federal republic after defeat in World War I and the abdication of the Emperor, Wilhelm II.The German...

, Otto von Bismarck

Otto von Bismarck

Otto Eduard Leopold, Prince of Bismarck, Duke of Lauenburg , simply known as Otto von Bismarck, was a Prussian-German statesman whose actions unified Germany, made it a major player in world affairs, and created a balance of power that kept Europe at peace after 1871.As Minister President of...

.

Until the mid-19th century, the Catholic Church was still a political power. The Pope's Papal States

Papal States

The Papal State, State of the Church, or Pontifical States were among the major historical states of Italy from roughly the 6th century until the Italian peninsula was unified in 1861 by the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia .The Papal States comprised territories under...

were supported by France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

but ceased to exist as an indirect result of the Franco-Prussian War

Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the 1870 War was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the Kingdom of Prussia. Prussia was aided by the North German Confederation, of which it was a member, and the South German states of Baden, Württemberg and...

. The Catholic Church still had a strong influence on many parts of life, even in Bismarck's traditionally Prussia

Prussia

Prussia was a German kingdom and historic state originating out of the Duchy of Prussia and the Margraviate of Brandenburg. For centuries, the House of Hohenzollern ruled Prussia, successfully expanding its size by way of an unusually well-organized and effective army. Prussia shaped the history...

, which was mainly Protestant, with the latter having absorbed some of the Catholic regions in Western Germany. In the newly founded German Empire, Bismarck intended to cut Catholics' loyalty with Rome (ultramontanism

Ultramontanism

Ultramontanism is a religious philosophy within the Roman Catholic community that places strong emphasis on the prerogatives and powers of the Pope...

) and subordinate all Germans to the power of the state, which was officially secular

Secularism

Secularism is the principle of separation between government institutions and the persons mandated to represent the State from religious institutions and religious dignitaries...

but had close ties with the Protestant Church. Bismarck sought to reduce the political and social influence of the Roman Catholic Church by instituting political control over Church activities.

Priests and bishops who resisted the Kulturkampf were arrested or removed from their positions. By the height of anti-Catholic legislation, half of the Prussian bishops were in prison or in exile, a quarter of the parishes had no priest, half the monks and nuns had left Prussia, a third of the monasteries and convents were closed, 1800 parish priests were imprisoned or exiled, and thousands of laypeople were imprisoned for helping the priests.

It is generally accepted amongst historians that the Kulturkampf measures targeted the Catholic Church under Pope Pius IX

Pope Pius IX

Blessed Pope Pius IX , born Giovanni Maria Mastai-Ferretti, was the longest-reigning elected Pope in the history of the Catholic Church, serving from 16 June 1846 until his death, a period of nearly 32 years. During his pontificate, he convened the First Vatican Council in 1869, which decreed papal...

with discriminatory sanctions. Many historians also point out anti-Polish elements in the policies in other contexts.

In Catholic countries

Anti-clericalismAnti-clericalism

Anti-clericalism is a historical movement that opposes religious institutional power and influence, real or alleged, in all aspects of public and political life, and the involvement of religion in the everyday life of the citizen...

is a historical movement that opposes religious (generally Catholic) institutional power and influence in all aspects of public and political life, and the involvement of religion in the everyday life of the citizen. It suggests a more active and partisan role than mere laïcité

Laïcité

French secularism, in French, laïcité is a concept denoting the absence of religious involvement in government affairs as well as absence of government involvement in religious affairs. French secularism has a long history but the current regime is based on the 1905 French law on the Separation of...

. The goal of anticlericalism is sometimes to reduce religion to a purely private belief-system with no public profile or influence. However, many times it has included outright suppression of all aspects of faith.

Anticlericalism has at times been violent, leading to murders and the desecration, destruction and seizure of church property. Anticlericalism in one form or another has existed throughout most of Christian history, and is considered to be one of the major popular forces underlying the 16th century reformation. Some of the philosophers of the Enlightenment

Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment was an elite cultural movement of intellectuals in 18th century Europe that sought to mobilize the power of reason in order to reform society and advance knowledge. It promoted intellectual interchange and opposed intolerance and abuses in church and state...

, including Voltaire

Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet , better known by the pen name Voltaire , was a French Enlightenment writer, historian and philosopher famous for his wit and for his advocacy of civil liberties, including freedom of religion, free trade and separation of church and state...

, continually attacked the Catholic Church, both its leadership and priests, claiming that many of its clergy were morally corrupt. These assaults in part led to the suppression of the Jesuits, and played a major part in the wholesale attacks on the very existence of the Church during the French Revolution

French Revolution

The French Revolution , sometimes distinguished as the 'Great French Revolution' , was a period of radical social and political upheaval in France and Europe. The absolute monarchy that had ruled France for centuries collapsed in three years...

in the Reign of Terror

Reign of Terror

The Reign of Terror , also known simply as The Terror , was a period of violence that occurred after the onset of the French Revolution, incited by conflict between rival political factions, the Girondins and the Jacobins, and marked by mass executions of "enemies of...

and the program of dechristianization

Dechristianisation of France during the French Revolution

The dechristianisation of France during the French Revolution is a conventional description of the results of a number of separate policies, conducted by various governments of France between the start of the French Revolution in 1789 and the Concordat of 1801, forming the basis of the later and...

. Similar attacks on the Church occurred in Mexico

Cristero War

The Cristero War of 1926 to 1929 was an uprising and counter-revolution against the Mexican government in power at that time. The rebellion was set off by the strict enforcement of the anti-clerical provisions of the Mexican Constitution of 1917 and the expansion of further anti-clerical laws...

and in Spain

Red Terror (Spain)

The Red Terror in Spain is the name given by historians to various acts committed "by sections of nearly all the leftist groups" such as the killing of tens of thousands of people , as well as attacks on landowners, industrialists, and politicians, and the...

in the twentieth century.

Brazil

Brazil has the largest number of Catholics in the world, and as such has not experienced any large anti-Catholicism movements. Even during times in which the Church was experiencing intense conservativeness, such as the Brazilian military dictatorship, anti-Catholicism was not advocated by the left-wing movements (instead, the Liberation theologyLiberation theology

Liberation theology is a Christian movement in political theology which interprets the teachings of Jesus Christ in terms of a liberation from unjust economic, political, or social conditions...

gained force). However, with the growing number of Protestants (especially Neo-Pentecostals) in the country, anti-Catholicism has gained strength. A pivotal moment of the rising anti-Catholicism was the kicking of the saint

Kicking of the saint

The "Chute na santa" incident was a religious controversy that erupted in Brazil on late 1995, sparked by a live broadcast of a Universal Church of the Kingdom of God minister kicking the image of a Roman Catholic saint.-The incident:...

episode in 1995. However, owing to the protests of the Catholic majority, the perpetrator was transferred to South Africa

South Africa

The Republic of South Africa is a country in southern Africa. Located at the southern tip of Africa, it is divided into nine provinces, with of coastline on the Atlantic and Indian oceans...

for the duration of the controversy.

Colombia

Anti-Catholic and anti-clerical sentiments, some spurred by an anti-clerical conspiracy theoryConspiracy theory

A conspiracy theory explains an event as being the result of an alleged plot by a covert group or organization or, more broadly, the idea that important political, social or economic events are the products of secret plots that are largely unknown to the general public.-Usage:The term "conspiracy...

which was circulating in Colombia during the mid-twentieth century led to persecution of Catholics and killings, most specifically of the clergy, during the events known as La Violencia

La Violencia

La Violencia is a period of civil conflict in the Colombian countryside between supporters of the Colombian Liberal Party and the Colombian Conservative Party, a conflict which took place roughly from 1948 to 1958 ....

.

El Salvador

During the Salvadoran Civil War, a number of the clergy were murdered, most notable was Archbishop Óscar RomeroÓscar Romero

Óscar Arnulfo Romero y Galdámez was a bishop of the Catholic Church in El Salvador. He became the fourth Archbishop of San Salvador, succeeding Luis Chávez. He was assassinated on 24 March 1980....

.

France

During the French RevolutionFrench Revolution

The French Revolution , sometimes distinguished as the 'Great French Revolution' , was a period of radical social and political upheaval in France and Europe. The absolute monarchy that had ruled France for centuries collapsed in three years...

(1789–95) clergy and religious were persecuted and church property was destroyed and confiscated by the new government as part of a process of Dechristianization, the aim of which was the destruction of Catholic practice and of the very faith itself, culminating the imposition of the atheistic Cult of Reason

Cult of Reason

The Cult of Reason was an atheistic belief system established in France and intended as a replacement for Christianity during the French Revolution.-Origins:...

and then the deistic Cult of the Supreme Being

Cult of the Supreme Being

The Cult of the Supreme Being was a form of deism established in France by Maximilien Robespierre during the French Revolution. It was intended to become the state religion of the new French Republic.- Origins :...

. Persecution led Catholics in the west of France to engage in a counterrevolution, The War in the Vendee, and when the state was victorious it put down the population in what some call the first modern genocide. The French invasions of Italy (1796–99) included an assault on Rome and the exile of Pope Pius VI

Pope Pius VI

Pope Pius VI , born Count Giovanni Angelo Braschi, was Pope from 1775 to 1799.-Early years:Braschi was born in Cesena...

in 1798. Relations improved from 1802 until 1809, when Napoleon invaded the Papal States and imprisoned Pope Pius VII

Pope Pius VII

Pope Pius VII , born Barnaba Niccolò Maria Luigi Chiaramonti, was a monk, theologian and bishop, who reigned as Pope from 14 March 1800 to 20 August 1823.-Early life:...

. By 1815 the Papacy supported the growing alliance against Napoleon, and was re-instated as the state church during the conservative Bourbon Restoration

Bourbon Restoration

The Bourbon Restoration is the name given to the period following the successive events of the French Revolution , the end of the First Republic , and then the forcible end of the First French Empire under Napoleon – when a coalition of European powers restored by arms the monarchy to the...

of 1815-30. The brief French Revolution of 1848

French Revolution of 1848

The 1848 Revolution in France was one of a wave of revolutions in 1848 in Europe. In France, the February revolution ended the Orleans monarchy and led to the creation of the French Second Republic. The February Revolution was really the belated second phase of the Revolution of 1830...

again opposed the Church, but the Second French Empire

Second French Empire

The Second French Empire or French Empire was the Imperial Bonapartist regime of Napoleon III from 1852 to 1870, between the Second Republic and the Third Republic, in France.-Rule of Napoleon III:...

(1851–71) gave it full support. The history of 1789-1871 had established two camps – liberals against the Church and conservatives supporting it – that largely continued until the Vatican II process in 1962-65.

France's Third Republic

French Third Republic

The French Third Republic was the republican government of France from 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed due to the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, to 1940, when France was overrun by Nazi Germany during World War II, resulting in the German and Italian occupations of France...

(1871–1940) was cemented by anti-clericalism, the desire to secularise the State and social life, faithful to the French Revolution. The Dreyfus affair

Dreyfus Affair

The Dreyfus affair was a political scandal that divided France in the 1890s and the early 1900s. It involved the conviction for treason in November 1894 of Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a young French artillery officer of Alsatian Jewish descent...

again polarised opinion in the 1890s. In the Affaire Des Fiches

Affaire Des Fiches

L'Affaire des Fiches de délation was a political scandal in France in 1904-1905 in which it was discovered that the militantly anticlerical War Minister under Emile Combes, General Louis André, was determining promotions based on a huge card index on public officials, detailing which were Catholic...

, in France in 1904–1905, it was discovered that the militantly anticlerical War Minister under Emile Combes

Émile Combes

Émile Combes was a French statesman who led the Bloc des gauches's cabinet from June 1902 – January 1905.-Biography:Émile Combes was born in Roquecourbe, Tarn. He studied for the priesthood, but abandoned the idea before ordination. His anti-clericalism would later lead him into becoming a...

, General Louis André

Louis André

Louis André was France's Minister of War from 1900 until 1904. Loyal to the laïque Third Republic, he was anti-Catholic, militantly anticlerical, a Freemason and was implicated in the Affaire Des Fiches, a scandal in which he received reports from Masonic groups on which army officers were...

, was determining promotions based on the French Masonic

Anticlericalism and Freemasonry

The question of whether Freemasonry is Anticlerical is the subject of debate. The Catholic Church has long been an outspoken critic of Freemasonry, and Catholic scholars have often accused the fraternity of anticlericalism. The Catholic Church forbids its members to join any masonic society under...

Grand Orient's huge card index on public officials, detailing which were Catholic and who attended Mass, with the goal of preventing their promotions.

Mexico

Following the Revolution of 1860, US-backed President Benito JuárezBenito Juárez

Benito Juárez born Benito Pablo Juárez García, was a Mexican lawyer and politician of Zapotec origin from Oaxaca who served five terms as president of Mexico: 1858–1861 as interim, 1861–1865, 1865–1867, 1867–1871 and 1871–1872...

, issued a decree nationalizing church property, separating church and state, and suppressing religious orders.

Following the revolution of 1910, the new Mexican Constitution of 1917 contained further anti-clerical provisions. Article 3 called for secular education in the schools and prohibited the Church from engaging in primary education; Article 5 outlawed monastic orders; Article 24 forbade public worship outside the confines of churches; and Article 27 placed restrictions on the right of religious organizations to hold property. Article 130 deprived clergy members of basic political rights.

Mexican President Plutarco Elías Calles

Plutarco Elías Calles

Plutarco Elías Calles was a Mexican general and politician. He was president of Mexico from 1924 to 1928, but he continued to be the de facto ruler from 1928–1935, a period known as the maximato...

's enforcement of previous anti-Catholic legislation denying priests' rights, enacted as the Calles Law

Calles Law

The Calles' Law, or Law for Reforming the Penal Code, was a reform of the penal code in Mexico under the presidency of Plutarco Elias Calles. The code reinforced strong restrictions against clerics and the Catholic Church put forth under Article 130 of the Mexican Constitution of 1917. Article 130...

, prompted the Mexican Episcopate to suspend all Catholic worship in Mexico from August 1, 1926 and sparked the bloody Cristero War

Cristero War

The Cristero War of 1926 to 1929 was an uprising and counter-revolution against the Mexican government in power at that time. The rebellion was set off by the strict enforcement of the anti-clerical provisions of the Mexican Constitution of 1917 and the expansion of further anti-clerical laws...

of 1926–1929 in which some 50,000 peasants took up arms against the government. Their slogan was "¡Viva Cristo Rey!" (Long live Christ the King!).

The effects of the war on the Church were profound. Between 1926 and 1934 at least 40 priests were killed. Where there were 4,500 priests serving the people before the rebellion, in 1934 there were only 334 priests licensed by the government to serve fifteen million people, the rest having been eliminated by emigration, expulsion and assassination. It appears that ten states were left without any priests. Other sources, indicate that the persecution was such that by 1935, 17 states were left with no priests at all.

Some of the Catholic casualties of this struggle are known as the Saints of the Cristero War

Saints of the Cristero War

On May 21, 2000, Pope John Paul II canonized a group of 25 saints and martyrs arising from the Mexican Cristero War. The vast majority are Roman Catholic priests who were executed for carrying out their ministry despite the suppression under the anti-clerical laws of Plutarco Elías Calles. Priests...

. Events relating to this were famously portrayed in the novel The Power and the Glory

The Power and the Glory

The Power and the Glory is a novel by British author Graham Greene. The title is an allusion to the doxology often added to the end of the Lord's Prayer: "For thine is the kingdom, the power, and the glory, now and forever , amen." This novel has also been published in the US under the name The...

by Graham Greene

Graham Greene

Henry Graham Greene, OM, CH was an English author, playwright and literary critic. His works explore the ambivalent moral and political issues of the modern world...

. The persecution was most severe in Tabasco under the strident atheist governor Tomás Garrido Canabal

Tomás Garrido Canabal

Tomás Garrido Canabal , was a Mexican politician and revolutionary. Garrido Canabal served as dictator and governor of the state of Tabasco from 1920 to 1924 and again from 1931 to 1934, and was particularly noted for his anti-Catholic persecution...

. Under the rule of Garrido many priests were killed, all Churches in the state were closed and priests who still survived were forced to marry or flee at risk of losing their lives.

Haiti

FrançoisFrançois Duvalier

François Duvalier was the President of Haiti from 1957 until his death in 1971. Duvalier first won acclaim in fighting diseases, earning him the nickname "Papa Doc" . He opposed a military coup d'état in 1950, and was elected President in 1957 on a populist and black nationalist platform...

and Jean-Claude Duvalier

Jean-Claude Duvalier

Jean-Claude Duvalier, nicknamed "Bébé Doc" or "Baby Doc" was the President of Haiti from 1971 until his overthrow by a popular uprising in 1986. He succeeded his father, François "Papa Doc" Duvalier, as the ruler of Haiti upon his father's death in 1971...

's family dictatorship

Family dictatorship

A hereditary dictatorship, or family dictatorship, in political science terms a personalistic regime, is a form of dictatorship that occurs in a nominally or formally republican regime, but operates in practice like an absolute monarchy, in that political power passes within the dictator's family...

of Haiti

Haiti

Haiti , officially the Republic of Haiti , is a Caribbean country. It occupies the western, smaller portion of the island of Hispaniola, in the Greater Antillean archipelago, which it shares with the Dominican Republic. Ayiti was the indigenous Taíno or Amerindian name for the island...

wanted to weaken the control of the Catholic Church so as to ensure loyalty to their regimes. The senior Duvalier was excommunicated by the Vatican for his blatant anti-clericalism, but it was rescinded as part of the negotiations to renew communications with the Vatican. The Catholic Church, particularly in the form of Jean Bertrand Aristide was instrumental in overthrowing the younger Duvalier.

Italy

In 1860 through 1870, the new Italian government, under the Savoy Monarchy, outlawed all the religious orders, male and female, including the Franciscans, the Dominicans and the Jesuits, closed down their monasteries and confiscated their property, and imprisoned or banished bishops who opposed this.In 1870 when the troops of Victor Emmanuel of Savoy rammed their way into Rome, proclaiming it the capital of Italy, they also took over the "Quirinale", the residence of the Pope, which since then has been the residence of the Italian lay rulers.

Spain

Anti-clericalism in Spain at the start of the Spanish Civil WarSpanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil WarAlso known as The Crusade among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War among Carlists, and The Rebellion or Uprising among Republicans. was a major conflict fought in Spain from 17 July 1936 to 1 April 1939...

resulted in the killing of almost 7,000 clergy, the destruction of hundreds of churches and the persecution of lay people in Spain's Red Terror

Red Terror (Spain)

The Red Terror in Spain is the name given by historians to various acts committed "by sections of nearly all the leftist groups" such as the killing of tens of thousands of people , as well as attacks on landowners, industrialists, and politicians, and the...

. Hundreds of Martyrs of the Spanish Civil War

Martyrs of the Spanish Civil War

Martyrs of the Spanish Civil War is the name given by the Catholic Church to the people who were killed by Republicans during the war because of their faith. As of July 2008, almost one thousand Spanish martyrs have been beatified or canonized...

have been beatified and hundreds more were beatified in October 2007.

Poland

Catholicism in Poland, the religion of the vast majority of the population, was severely persecuted during World War IIWorld War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, following the Nazi invasion of the country and its subsequent annexation into Germany. Over 3 million Catholics of Polish descent were murdered during the Invasion of Poland. Among them was Saint Maximillian Kolbe. In 1999, 108 Polish Catholic victims of the invasion of Poland, including 3 bishops, 52 priests, 26 monks, 3 seminarians, 8 nuns and 9 lay people, were beatified by Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II

Blessed Pope John Paul II , born Karol Józef Wojtyła , reigned as Pope of the Catholic Church and Sovereign of Vatican City from 16 October 1978 until his death on 2 April 2005, at of age. His was the second-longest documented pontificate, which lasted ; only Pope Pius IX ...

as the 108 Martyrs of World War Two

108 Martyrs of World War Two

The 108 Martyrs of World War II, known also as 108 Blessed Polish Martyrs , were Roman Catholics from Poland killed during World War II by the Nazis....

.

The Roman Catholic Church was even more violently suppressed in Reichsgau Wartheland

Reichsgau Wartheland

Reichsgau Wartheland was a Nazi German Reichsgau formed from Polish territory annexed in 1939. It comprised the Greater Poland and adjacent areas, and only in part matched the area of the similarly named pre-Versailles Prussian province of Posen...

and the General Government

General Government

The General Government was an area of Second Republic of Poland under Nazi German rule during World War II; designated as a separate region of the Third Reich between 1939–1945...

. Churches were closed, with clergy deported, imprisoned, or killed, among them Maximilian Kolbe

Maximilian Kolbe

Saint Maximilian Maria Kolbe OFM Conv was a Polish Conventual Franciscan friar, who volunteered to die in place of a stranger in the Nazi German concentration camp of Auschwitz, located in German-occupied Poland during World War II.He was canonized on 10 October 1982 by Pope John Paul II, and...

, a Pole of German descent. Between 1939 and 1945, 2,935 members of the Polish clergy (18%) were killed in concentration camps. In the city of Chełmno, for example, 48% of the Catholic clergy were killed.

Catholicism continued to be persecuted under the Communist regime from the 1950s. Current Stalinist

Stalinism

Stalinism refers to the ideology that Joseph Stalin conceived and implemented in the Soviet Union, and is generally considered a branch of Marxist–Leninist ideology but considered by some historians to be a significant deviation from this philosophy...

ideology claimed that the Church and religion in general were about to disintegrate. To begin with, Archbishop Wyszyński entered into an agreement with the Communist authorities, which was signed on 14 February 1950 by the Polish episcopate and the government. The Agreement regulated the matters of the Church in Poland. However, in May of that year, the Sejm breached the Agreement by passing a law for the confiscation of Church property.

On 12 January 1953, Wyszyński was elevated to the rank of cardinal by Pius XII as another wave of persecution began in Poland. When the bishops voiced their opposition to state interference in ecclesiastical appointments, mass trials and the internment of priests began - the cardinal being one of its victims. On 25 September 1953 he was imprisoned at Grudziądz, and later placed under house arrest in monasteries in Prudnik near Opole and in Komańcza in the Bieszczady Mountains. He was not released until 26 October 1956.

Pope John Paul II, who was born in Poland as Karol Wojtyla, often cited the persecution of Polish Catholics in his stance against Communism.

Eastern Christianity

Less widely known in the West has been the anti-Catholicism found in countries where the Eastern Christian Churches have prevailed historically. This form of anti-Catholicism has its roots in the Great SchismEast–West Schism

The East–West Schism of 1054, sometimes known as the Great Schism, formally divided the State church of the Roman Empire into Eastern and Western branches, which later became known as the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Roman Catholic Church, respectively...

between the Western and Eastern Church in 1054, and the Sack of Constantinople by Catholic forces from Western Europe, though unsupported by the pope, during the Fourth Crusade

Fourth Crusade

The Fourth Crusade was originally intended to conquer Muslim-controlled Jerusalem by means of an invasion through Egypt. Instead, in April 1204, the Crusaders of Western Europe invaded and conquered the Christian city of Constantinople, capital of the Eastern Roman Empire...

in 1204. About the sack Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II

Blessed Pope John Paul II , born Karol Józef Wojtyła , reigned as Pope of the Catholic Church and Sovereign of Vatican City from 16 October 1978 until his death on 2 April 2005, at of age. His was the second-longest documented pontificate, which lasted ; only Pope Pius IX ...

gave a public apology during his visit in Greece in 2001, an historically Orthodox country, (Greeks are considered the cultural heirs of the Byzantine Empire). He was the first pope to visit Greece in 1291 years.

Sri Lanka

A Buddhist-influenced government took over 600 parish schools in 1960 without compensation and secularized. Attempts were made by future governments to restore some autonomy.Sudan

In the Islamic state of Sudan, many Catholics were killed in pogroms before and during the Second Sudanese Civil WarSecond Sudanese Civil War

The Second Sudanese Civil War started in 1983, although it was largely a continuation of the First Sudanese Civil War of 1955 to 1972. Although it originated in southern Sudan, the civil war spread to the Nuba mountains and Blue Nile by the end of the 1980s....

.

In apologetics

Daniel GoldhagenDaniel Goldhagen

Daniel Jonah Goldhagen is an American author and former Associate Professor of Political Science and Social Studies at Harvard University. Goldhagen reached international attention and broad criticism as the author of two controversial books about the Holocaust, Hitler's Willing Executioners and...

recognises that there has been much ill-will and genuine bigotry directed towards Catholics and the Catholic Church and that it is never right to criticize untruthfully a person only on the basis of being Catholic even when they make innocent mistakes. While opposed to anti-Catholicism, he believes that people are labelled falsely as "anti-Catholic" by defenders of the Church to silence them rather to avoid answering legitimate questions truthfully. He believes that in these cases anti-Catholic charges are designed to prevent "a sober scholarly appraisal" of the Church's deeds.

In popular culture

Anti-Catholic stereotypes are a long-standing feature of English literatureEnglish literature

English literature is the literature written in the English language, including literature composed in English by writers not necessarily from England; for example, Robert Burns was Scottish, James Joyce was Irish, Joseph Conrad was Polish, Dylan Thomas was Welsh, Edgar Allan Poe was American, J....

, popular fiction, and even pornography. Gothic fiction

Gothic fiction

Gothic fiction, sometimes referred to as Gothic horror, is a genre or mode of literature that combines elements of both horror and romance. Gothicism's origin is attributed to English author Horace Walpole, with his 1764 novel The Castle of Otranto, subtitled "A Gothic Story"...

is particularly rich in this regard. Lustful priests, cruel abbesses, immured nuns, and sadistic inquisitors appear in such works as The Italian

The Italian (novel)

The Italian, or the Confessional of the Black Penitents is a Gothic novel written by the English author Ann Radcliffe. It is the last book Radcliffe published during her lifetime...

by Ann Radcliffe

Ann Radcliffe

Anne Radcliffe was an English author, and considered the pioneer of the gothic novel . Her style is romantic in its vivid descriptions of landscapes, and long travel scenes, yet the Gothic element is obvious through her use of the supernatural...

, The Monk

The Monk

The Monk: A Romance is a Gothic novel by Matthew Gregory Lewis, published in 1796. It was written before the author turned 20, in the space of 10 weeks.-Characters:...

by Matthew Lewis, Melmoth the Wanderer

Melmoth the Wanderer

Melmoth the Wanderer is a gothic novel published in 1820, written by Charles Robert Maturin .- Synopsis :...

by Charles Maturin

Charles Maturin

Charles Robert Maturin, also known as C.R. Maturin was an Irish Protestant clergyman and a writer of gothic plays and novels.-Biography:...

and "The Pit and the Pendulum

The Pit and the Pendulum

"The Pit and the Pendulum" is a short story written by Edgar Allan Poe and first published in 1842 in the literary annual The Gift: A Christmas and New Year's Present for 1843. The story is about the torments endured by a prisoner of the Spanish Inquisition, though Poe skews historical facts. The...

" by Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe was an American author, poet, editor and literary critic, considered part of the American Romantic Movement. Best known for his tales of mystery and the macabre, Poe was one of the earliest American practitioners of the short story and is considered the inventor of the detective...

.

See also

- BigotryBigotryA bigot is a person obstinately or intolerantly devoted to his or her own opinions and prejudices, especially one exhibiting intolerance, and animosity toward those of differing beliefs...

- AIDS Coalition to Unleash PowerAIDS Coalition to Unleash PowerAIDS Coalition to Unleash Power is an international direct action advocacy group working to impact the lives of people with AIDS and the AIDS pandemic to bring about legislation, medical research and treatment and policies to ultimately bring an end to the disease by mitigating loss of health and...

- Anti-Christian sentiment

- Anti-clerical artAnti-clerical artAnti-clerical art is a genre of art portraying clergy, especially Roman Catholic clergy, in unflattering contexts. It was especially popular in France during the second half of the 19th century, at a time that the anti-clerical message suited the prevailing political mood...

- Anti-Irish racism

- Anti-Polonism

- Anti-ItalianismAnti-ItalianismAnti-Italianism is a hostility toward Italian people utilizing stereotypes about them, such as the idea that the Italians are tolerant of violence, political corruption, Italy's former alliance with Nazi Germany and criminal groups such as the Mafia...

- Religious persecutionReligious persecutionReligious persecution is the systematic mistreatment of an individual or group of individuals as a response to their religious beliefs or affiliations or lack thereof....

- Black LegendBlack LegendThe Black Legend refers to a style of historical writing that demonizes Spain and in particular the Spanish Empire in a politically motivated attempt to morally disqualify Spain and its people, and to incite animosity against Spanish rule...

- James Carroll

- Jack Chick

- Chick Publications

- Anjem ChoudaryAnjem ChoudaryAnjem Choudary is a British former solicitor, and, before it was proscribed, spokesman for the Islamist group Islam4UK. He is married, has four children, and lives in Ilford, London....

- John Cornwell (writer)John Cornwell (writer)John Cornwell is an English journalist and author, and a Fellow of Jesus College, Cambridge. He is best known for various books on the papacy, most notably Hitler's Pope; investigative journalism; memoir; and the public understanding of science and philosophy. More recently he has been concerned...

- Count's FeudCount's FeudThe Count's Feud , also called the Count's War, was a civil war that raged in Denmark in 1534–36 and brought about the Reformation in Denmark...

- Daniel GoldhagenDaniel GoldhagenDaniel Jonah Goldhagen is an American author and former Associate Professor of Political Science and Social Studies at Harvard University. Goldhagen reached international attention and broad criticism as the author of two controversial books about the Holocaust, Hitler's Willing Executioners and...

- Gordon RiotsGordon RiotsThe Gordon Riots of 1780 were an anti-Catholic protest against the Papists Act 1778.The Popery Act 1698 had imposed a number of penalties and disabilities on Roman Catholics in England; the 1778 act eliminated some of these. An initial peaceful protest led on to widespread rioting and looting and...

- Great ApostasyGreat ApostasyThe Great Apostasy is a term used by some religious groups to describe a general fallen state of traditional Christianity, especially the Papacy, because it allowed the traditional Roman mysteries and deities of solar monism such as Mithras and Sol Invictus and idol worship back into the church,...

- Historicism (Christian eschatology)Historicism (Christian eschatology)Historicism is a method of interpretation, in Christian eschatology, by associating biblical prophecies with actual historical events as well as identifying symbolic beings with historical persons or societies. In prophetic theology, the main texts of interest are apocalyptic literature such as the...

- International Christian ConcernInternational Christian ConcernInternational Christian Concern is a non-denominational, non-governmental, Christian watchdog group, located in Washington, DC, whose concern is the human rights of Christians...

, a Christian human rights NGO whose mission is to help persecuted Christians world-wide - Institutional Revolutionary PartyInstitutional Revolutionary PartyThe Institutional Revolutionary Party is a Mexican political party that held power in the country—under a succession of names—for more than 70 years. The PRI is a member of the Socialist International, as is the rival Party of the Democratic Revolution , making Mexico one of the few...

- Klansmen: Guardians of LibertyKlansmen: Guardians of LibertyKlansmen: Guardians of Liberty was a book published by the Pillar of Fire Church in 1926 by Bishop Alma Bridwell White and illustrated by Reverend Branford Clarke. She claims that the founding fathers of the United States were members of the Ku Klux Klan, and that Paul Revere made his legendary...

- The endarkenment

- Ku Klux Klan in MaineKu Klux Klan in MaineAlthough the Ku Klux Klan is popularly associated with white supremacy, the revived Klan of the 1920s was also anti-Catholic. In the State of Maine, with a negligible African-American population but a burgeoning number of French-Canadian and Irish immigrants, the Klan revival of the 1920s was...

- The Ku Klux Klan In ProphecyThe Ku Klux Klan In ProphecyThe Ku Klux Klan In Prophecy is a 144 page book written by Bishop Alma Bridwell White in 1925 and illustrated by Reverend Branford Clarke. In the book she uses scripture to rationalize that the Klan is sanctioned by God "through divine illumination and prophetic vision". She also believed that the...

- Emmett McLoughlinEmmett McLoughlinEmmett McLoughlin was a Catholic priest of the Franciscan order who became known in the 1930s as an advocate for low-income housing in Phoenix, Arizona...

- Persecutions of the Catholic Church and Pius XIIPersecutions of the Catholic Church and Pius XIIPersecutions against the Catholic Church took place in virtually all the years of the pontificate of Pope Pius XII, especially after World War II in Eastern Europe, the USSR and the People's Republic of China...

- Sectarianism in GlasgowSectarianism in GlasgowSectarianism in Glasgow takes the form of religious and political sectarian rivalry between Roman Catholics and Protestants. It is reinforced by the fierce rivalry between Celtic F.C. and Rangers F.C., the two Old Firm football clubs...

- Ralph OvadalRalph OvadalRalph Ovadal is the pastor of Pilgrims Covenant Church in Monroe, Wisconsin. He is a Reformed Baptist, although his church is not part of any formally recognized denomination. He is noted for impassioned street preaching and picketing in various cities...

- George Templeton StrongGeorge Templeton StrongGeorge Templeton Strong was an American lawyer and diarist. His 2,250-page diary, discovered in the 1930s, provides a striking personal account of life in the 19th century, especially during the events of the American Civil War...

- Vicarius Filii DeiVicarius Filii DeiVicarius Filii Dei is a phrase first used in the forged medieval Donation of Constantine to refer to Saint Peter, a leader of the Early Christian Church and regarded as the first Pope by the Catholic Church...

Martyrs' Memorial

The Martyrs' Memorial is a stone monument positioned at the intersection of St Giles', Magdalen Street and Beaumont Street in Oxford, England just outside Balliol College...

- Derogatory terms

- Mackerel SnapperMackerel Snapper"Mackerel snapper" is a sectarian slur for Roman Catholics, originating in the United States in the 1850s. It referred to the Catholic discipline of Friday abstinence from red meat and poultry, for which fish was substituted...

- Recovering CatholicRecovering catholicThe term "recovering Catholic", is used by some former practitioners of the Roman Catholic faith to describe their religious status. The use of the term implies that the person considers their former Catholicism to have been a negative influence on their life: something that must be "recovered" from...

- Mackerel Snapper

- Institutionalized politics, within a country

- Amanda MarcotteAmanda MarcotteAmanda Marie Marcotte is an American blogger best known for her writing on feminism and politics. Time magazine described her as "an outspoken voice of the left" and said "there is a welcome wonkishness to Marcotte, who, unlike some star bloggers, is not afraid to parse policy with her...

- American Protective AssociationAmerican Protective AssociationThe American Protective Association, or APA was an American anti-Catholic society similar to the Know Nothings.-History:The APA was founded 13 March 1887 by Attorney Henry F. Bowers in Clinton, Iowa...

, U.S. group in 1890s - Know NothingKnow NothingThe Know Nothing was a movement by the nativist American political faction of the 1840s and 1850s. It was empowered by popular fears that the country was being overwhelmed by German and Irish Catholic immigrants, who were often regarded as hostile to Anglo-Saxon Protestant values and controlled by...

- James G. BlaineJames G. BlaineJames Gillespie Blaine was a U.S. Representative, Speaker of the United States House of Representatives, U.S. Senator from Maine, two-time Secretary of State...

- Protestant Protective AssociationProtestant Protective AssociationThe Protestant Protective Association was an anti-Catholic group in the 1890s based in Ontario, Canada, associated with the Orange Order. Originally a spinoff of the American group the American Protective Association, it became independent in 1892...

, Canadian group in 1890s

- Amanda Marcotte

- Ulster

- Ulster loyalismUlster loyalismUlster loyalism is an ideology that is opposed to a united Ireland. It can mean either support for upholding Northern Ireland's status as a constituent part of the United Kingdom , support for Northern Ireland independence, or support for loyalist paramilitaries...

- Protestant Unionist PartyProtestant Unionist PartyThe Protestant Unionist Party was a unionist political party operating in Northern Ireland from 1966 to 1971. It was set up by Ian Paisley, and was the forerunner of the modern Democratic Unionist Party and emerged from the Ulster Protestant Action movement.The UPA had two councillors elected,...

- Tara (Northern Ireland)Tara (Northern Ireland)Tara was a loyalist movement in Northern Ireland that espoused a brand of evangelical Protestantism.The group was first formed in 1966 by William McGrath from an independent Orange lodge that he controlled. It was intended as an outlet for virulent anti-Catholicism...

- Ian PaisleyIan PaisleyIan Richard Kyle Paisley, Baron Bannside, PC is a politician and church minister in Northern Ireland. As the leader of the Democratic Unionist Party , he and Sinn Féin's Martin McGuinness were elected First Minister and deputy First Minister respectively on 8 May 2007.In addition to co-founding...

- Ulster loyalism

- Other religions bigotry

-

- Anti-Buddhism

- Anti-Hinduism

- Anti-Christianity

- Anti-JudaismAnti-JudaismReligious antisemitism is a form of antisemitism, which is the prejudice against, or hostility toward, the Jewish people based on hostility to Judaism and to Jews as a religious group...