History of Cornwall

Encyclopedia

Cornwall

Cornwall is a unitary authority and ceremonial county of England, within the United Kingdom. It is bordered to the north and west by the Celtic Sea, to the south by the English Channel, and to the east by the county of Devon, over the River Tamar. Cornwall has a population of , and covers an area of...

begins with the pre-Roman inhabitants, including speakers of a Celtic language that would develop into Brythonic

Brythonic languages

The Brythonic or Brittonic languages form one of the two branches of the Insular Celtic language family, the other being Goidelic. The name Brythonic was derived by Welsh Celticist John Rhys from the Welsh word Brython, meaning an indigenous Briton as opposed to an Anglo-Saxon or Gael...

and Cornish

Cornish language

Cornish is a Brythonic Celtic language and a recognised minority language of the United Kingdom. Along with Welsh and Breton, it is directly descended from the ancient British language spoken throughout much of Britain before the English language came to dominate...

. Cornwall was part of the territory of the tribe of the Dumnonii

Dumnonii

The Dumnonii or Dumnones were a British Celtic tribe who inhabited Dumnonia, the area now known as Devon and Cornwall in the farther parts of the South West peninsula of Britain, from at least the Iron Age up to the early Saxon period...

. After a period of Roman

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

rule, Cornwall reverted to rule by independent Romano-British

Romano-British

Romano-British culture describes the culture that arose in Britain under the Roman Empire following the Roman conquest of AD 43 and the creation of the province of Britannia. It arose as a fusion of the imported Roman culture with that of the indigenous Britons, a people of Celtic language and...

chieftains. (There is little evidence that Roman rule was effective west of Exeter

Exeter

Exeter is a historic city in Devon, England. It lies within the ceremonial county of Devon, of which it is the county town as well as the home of Devon County Council. Currently the administrative area has the status of a non-metropolitan district, and is therefore under the administration of the...

.) After a period of conflict with the Kingdom of Wessex

Wessex

The Kingdom of Wessex or Kingdom of the West Saxons was an Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the West Saxons, in South West England, from the 6th century, until the emergence of a united English state in the 10th century, under the Wessex dynasty. It was to be an earldom after Canute the Great's conquest...

, it became a part of the Kingdom of England

Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England was, from 927 to 1707, a sovereign state to the northwest of continental Europe. At its height, the Kingdom of England spanned the southern two-thirds of the island of Great Britain and several smaller outlying islands; what today comprises the legal jurisdiction of England...

which was subsequently incorporated into Great Britain

Kingdom of Great Britain

The former Kingdom of Great Britain, sometimes described as the 'United Kingdom of Great Britain', That the Two Kingdoms of Scotland and England, shall upon the 1st May next ensuing the date hereof, and forever after, be United into One Kingdom by the Name of GREAT BRITAIN. was a sovereign...

and the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

.

Cornwall has also figured in such pseudo-historical or legendary works as Geoffrey of Monmouth

Geoffrey of Monmouth

Geoffrey of Monmouth was a cleric and one of the major figures in the development of British historiography and the popularity of tales of King Arthur...

's Historia Regum Britanniae

Historia Regum Britanniae

The Historia Regum Britanniae is a pseudohistorical account of British history, written c. 1136 by Geoffrey of Monmouth. It chronicles the lives of the kings of the Britons in a chronological narrative spanning a time of two thousand years, beginning with the Trojans founding the British nation...

, a precursor of much Arthurian legend (see legendary Dukes of Cornwall

Legendary Dukes of Cornwall

"Duke of Cornwall" appears as a title in pseudo-historical authors as Nennius and Geoffrey of Monmouth. The list is extremely patchy, and not every succession was unbroken. Indeed, Geoffrey repeatedly introduces Dukes of Cornwall only to promote them to the Kingship of the Britons and thus put an...

).

Late Stone Age

The present human history of Cornwall begins with the reoccupation of Britain after the last Ice Age. The inhabitants may have been related to the IberiansIberians

The Iberians were a set of peoples that Greek and Roman sources identified with that name in the eastern and southern coasts of the Iberian peninsula at least from the 6th century BC...

who occupied Spain and France.

The upland areas of Cornwall were the parts first open to settlement as the vegetation required little in the way of clearance: they were perhaps first occupied in Neolithic times (Palaeolithic remains are almost non-existent in Cornwall). Many Megalithic monuments of this period exist in Cornwall and prehistoric remains in general are more numerous in Cornwall than in any other English county except Wiltshire. The remains are of various kinds and include standing stones, barrows and hut circles.

Bronze Age

Cornwall and neighbouring DevonDevon

Devon is a large county in southwestern England. The county is sometimes referred to as Devonshire, although the term is rarely used inside the county itself as the county has never been officially "shired", it often indicates a traditional or historical context.The county shares borders with...

had large reserves of tin

Tin

Tin is a chemical element with the symbol Sn and atomic number 50. It is a main group metal in group 14 of the periodic table. Tin shows chemical similarity to both neighboring group 14 elements, germanium and lead and has two possible oxidation states, +2 and the slightly more stable +4...

, which was mined extensively during the Bronze Age

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a period characterized by the use of copper and its alloy bronze as the chief hard materials in the manufacture of some implements and weapons. Chronologically, it stands between the Stone Age and Iron Age...

by people associated with the Beaker culture

Beaker culture

The Bell-Beaker culture , ca. 2400 – 1800 BC, is the term for a widely scattered cultural phenomenon of prehistoric western Europe starting in the late Neolithic or Chalcolithic running into the early Bronze Age...

. Tin is necessary to make bronze

Bronze

Bronze is a metal alloy consisting primarily of copper, usually with tin as the main additive. It is hard and brittle, and it was particularly significant in antiquity, so much so that the Bronze Age was named after the metal...

from copper

Copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu and atomic number 29. It is a ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. Pure copper is soft and malleable; an exposed surface has a reddish-orange tarnish...

, and by about 1600 BCE the West Country

West Country

The West Country is an informal term for the area of south western England roughly corresponding to the modern South West England government region. It is often defined to encompass the historic counties of Cornwall, Devon, Dorset and Somerset and the City of Bristol, while the counties of...

was experiencing a trade boom driven by the export of tin across Europe. This prosperity helped feed the skilfully wrought gold ornaments recovered from Wessex culture

Wessex culture

The Wessex culture is the predominant prehistoric culture of central and southern Britain during the early Bronze Age, originally defined by the British archaeologist Stuart Piggott in 1938...

sites.

There is evidence of a relatively large scale disruption of cultural practices around the 12th century BCE that some scholars think may indicate an invasion or migration into southern Britain.

Iron Age

Around 750 BCE the Iron AgeIron Age

The Iron Age is the archaeological period generally occurring after the Bronze Age, marked by the prevalent use of iron. The early period of the age is characterized by the widespread use of iron or steel. The adoption of such material coincided with other changes in society, including differing...

reached Britain, permitting greater scope of agriculture

Agriculture

Agriculture is the cultivation of animals, plants, fungi and other life forms for food, fiber, and other products used to sustain life. Agriculture was the key implement in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that nurtured the...

through the use of new iron ploughs and axes. The building of hill forts also peaked during the British Iron Age

British Iron Age

The British Iron Age is a conventional name used in the archaeology of Great Britain, referring to the prehistoric and protohistoric phases of the Iron-Age culture of the main island and the smaller islands, typically excluding prehistoric Ireland, and which had an independent Iron Age culture of...

. During broadly the same time (900 to 500 BCE), the Celtic culture and peoples

Celt

The Celts were a diverse group of tribal societies in Iron Age and Roman-era Europe who spoke Celtic languages.The earliest archaeological culture commonly accepted as Celtic, or rather Proto-Celtic, was the central European Hallstatt culture , named for the rich grave finds in Hallstatt, Austria....

spread across the British Isles.

During the British Iron Age

British Iron Age

The British Iron Age is a conventional name used in the archaeology of Great Britain, referring to the prehistoric and protohistoric phases of the Iron-Age culture of the main island and the smaller islands, typically excluding prehistoric Ireland, and which had an independent Iron Age culture of...

Cornwall, like all of Britain south of the Firth of Forth

Firth of Forth

The Firth of Forth is the estuary or firth of Scotland's River Forth, where it flows into the North Sea, between Fife to the north, and West Lothian, the City of Edinburgh and East Lothian to the south...

, was inhabited by the Celtic people known as the Britons

Britons (historical)

The Britons were the Celtic people culturally dominating Great Britain from the Iron Age through the Early Middle Ages. They spoke the Insular Celtic language known as British or Brythonic...

. The Celtic

Celtic languages

The Celtic languages are descended from Proto-Celtic, or "Common Celtic"; a branch of the greater Indo-European language family...

British language spoken at the time eventually developed into several distinct tongues, including Cornish

Cornish language

Cornish is a Brythonic Celtic language and a recognised minority language of the United Kingdom. Along with Welsh and Breton, it is directly descended from the ancient British language spoken throughout much of Britain before the English language came to dominate...

.

The first account of Cornwall comes from the Sicilian Greek historian Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus was a Greek historian who flourished between 60 and 30 BC. According to Diodorus' own work, he was born at Agyrium in Sicily . With one exception, antiquity affords no further information about Diodorus' life and doings beyond what is to be found in his own work, Bibliotheca...

(ca. 90 BCE–ca. 30 BCE), supposedly quoting or paraphrasing the fourth-century BCE geographer Pytheas

Pytheas

Pytheas of Massalia or Massilia , was a Greek geographer and explorer from the Greek colony, Massalia . He made a voyage of exploration to northwestern Europe at about 325 BC. He travelled around and visited a considerable part of Great Britain...

, who had sailed to Britain:

Strabo

Strabo, also written Strabon was a Greek historian, geographer and philosopher.-Life:Strabo was born to an affluent family from Amaseia in Pontus , a city which he said was situated the approximate equivalent of 75 km from the Black Sea...

, though not entirely reliable, state that the Phoenicians traded tin with Cornwall. There is no archaeological evidence for this. Some modern historians have attempted to debunk earlier antiquarian constructions of "the Phoenician legacy of Cornwall", including belief that the Phoenicians even settled Cornwall.

Toponymy

By the time that Classical written sources appear, Cornwall was inhabited by tribes speaking Celtic languagesCeltic languages

The Celtic languages are descended from Proto-Celtic, or "Common Celtic"; a branch of the greater Indo-European language family...

. The ancient Greeks and Romans used the name Belerion or Bolerium for the south-west tip of the island of Britain, but the late-Roman source for the Ravenna Cosmography

Ravenna Cosmography

The Ravenna Cosmography was compiled by an anonymous cleric in Ravenna around AD 700. It consists of a list of place-names covering the world from India to Ireland. Textual evidence indicates that the author frequently used maps as his source....

(compiled about 700 CE) introduces a place-name Puro coronavis, the first part of which seems to be a mis-spelling of Duro (meaning Fort). This appears to indicate that the tribe of the Cornovii

Cornovii (Cornish)

The Cornovii were a Celtic tribe who inhabited the far South West peninsula of Great Britain, during the Iron Age, Roman and post-Roman periods and gave their name to Cornwall or Kernow....

, known from earlier Roman sources as inhabitants of an area centred on modern Shropshire, had by about the 5th century CE established a power-base in the south-west (perhaps at Tintagel

Tintagel

Tintagel is a civil parish and village situated on the Atlantic coast of Cornwall, United Kingdom. The population of the parish is 1,820 people, and the area of the parish is ....

). The tribal name is therefore likely to be the origin of Kernow or later Curnow used for Cornwall in the Cornish language

Cornish language

Cornish is a Brythonic Celtic language and a recognised minority language of the United Kingdom. Along with Welsh and Breton, it is directly descended from the ancient British language spoken throughout much of Britain before the English language came to dominate...

. John Morris

John Morris (historian)

John Robert Morris was an English historian who specialised in the study of the institutions of the Roman Empire and the history of Sub-Roman Britain...

suggested that a contingent of the Cornovii was sent to South West Britain at the end of the Roman era, in order to rule the land there and keep out the invading Irish, but this theory was dismissed by Professor Philip Payton

Philip Payton

Philip John Payton is a British historian and Professor of Cornish and Australian Studies at the University of Exeter and Director of the Institute of Cornish Studies based at Tremough, just outside Penryn, Cornwall.-Birth and education:...

in his book Cornwall: A History. The Cornish Cornovii may even be a completely separate tribe, taking their name either from the horn shape of the peninsula, or from the Horned God Cernunnos

Cernunnos

Cernunnos is the conventional name given in Celtic studies to depictions of the horned god of Celtic polytheism. The name itself is only attested once, on the 1st-century Pillar of the Boatmen, but depictions of a horned or antlered figure, often seated in a "lotus position" and often associated...

.

The English name, Cornwall, comes from the Celtic name, to which the Anglo-Saxon

Old English language

Old English or Anglo-Saxon is an early form of the English language that was spoken and written by the Anglo-Saxons and their descendants in parts of what are now England and southeastern Scotland between at least the mid-5th century and the mid-12th century...

word Wealas (Welsh, or foreigners) is added.

Roman Cornwall

During the time of Roman dominance in BritainRoman Britain

Roman Britain was the part of the island of Great Britain controlled by the Roman Empire from AD 43 until ca. AD 410.The Romans referred to the imperial province as Britannia, which eventually comprised all of the island of Great Britain south of the fluid frontier with Caledonia...

, Cornwall was rather remote from the main centres of Romanisation. The Roman road system extended into Cornwall, but the only known significant Roman sites are three forts:- Tregear near Nanstallon

Nanstallon

Nanstallon is a village in central Cornwall, United Kingdom. It is situated approximately two miles west of Bodmin.Nanstallon is in the civil parish of Lanivet overlooking the River Camel valley and the Camel Trail long distance path. The present terminus of the Bodmin and Wenford Railway at...

was discovered in early 1970s , the other two found more recently at Restormel Castle

Restormel Castle

Restormel Castle is situated on the River Fowey near Lostwithiel, Cornwall, United Kingdom. It is one of the four chief Norman castles of Cornwall, the others being Launceston, Tintagel and Trematon. The castle is notable for its perfectly circular design...

, Lostwithiel (discovered 2007) and a fort near to St Andrew’s Church in Calstock

Calstock

Calstock is civil parish and a large village in south east Cornwall, England, United Kingdom, on the border with Devon. The village is situated on the River Tamar south west of Tavistock and north of Plymouth....

(discovered early in 2007). A Roman style villa was found at Magor Farm near Camborne

Camborne

Camborne is a town and civil parish in west Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It is at the western edge of a conurbation comprising Camborne, Pool and Redruth....

. Furthermore, the British tin trade had been largely eclipsed by the more convenient supply from Iberia

Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula , sometimes called Iberia, is located in the extreme southwest of Europe and includes the modern-day sovereign states of Spain, Portugal and Andorra, as well as the British Overseas Territory of Gibraltar...

.

Only a few Roman milestones have been found in Cornwall; two have been recovered from around Tintagel in the north (detailed below), one near the hillfort at Carn Brea

Carn Brea

Carn Brea is a civil parish and hilltop site in Cornwall, United Kingdom. The hilltop site is situated approximately one mile southwest of Redruth.-Neolithic settlement:...

, and another two close to St Michael's Mount

St Michael's Mount

St Michael's Mount is a tidal island located off the Mount's Bay coast of Cornwall, United Kingdom. It is a civil parish and is united with the town of Marazion by a man-made causeway of granite setts, passable between mid-tide and low water....

. The stone at Tintagel

Tintagel Parish Church

The Parish Church of Saint Materiana at Tintagel is an Anglican church in Cornwall, UK. It stands on the cliffs between Trevena and Tintagel Castle and is listed Grade I....

bears an inscription to Imperator Caesar Gaius Valerius Licinius Licinianus

Licinius

Licinius I , was Roman Emperor from 308 to 324. Co-author of the Edict of Milan that granted official toleration to Christians in the Roman Empire, for the majority of his reign he was the rival of Constantine I...

, and the other stone at Trethevy

Trethevy

Trethevy is a hamlet in north Cornwall, United Kingdom.It is situated midway between the villages of Tintagel and Boscastle in the civil parish of Tintagel. Trethevy has a number of historic buildings and is an early Christian site...

, is inscribed to the imperial Caesars, Gallus

Trebonianus Gallus

Trebonianus Gallus , also known as Gallus, was Roman Emperor from 251 to 253, in a joint rule with his son Volusianus.-Early life:Gallus was born in Italy, in a family with respected ancestry of Etruscan senatorial background. He had two children in his marriage with Afinia Gemina Baebiana: Gaius...

and Volusianus

Volusianus

Volusianus , also known as Volusian, was a Roman Emperor from 251 to 253.He was son to Gaius Vibius Trebonianus Gallus by his wife Afinia Gemina Baebiana. He is known to have had a sister, Vibia Galla....

.

According to Léon Fleuriot

Léon Fleuriot

Léon Fleuriot was a French academic specializing in Celtic languages and in history, particularly that of Gallo-Roman Brittany and of the Early Middle Ages....

, however, Cornwall remained closely integrated with neighbouring territories by well-travelled sea routes. Fleuriot suggests that an overland route connecting Padstow

Padstow

Padstow is a town, civil parish and fishing port on the north coast of Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. The town is situated on the west bank of the River Camel estuary approximately five miles northwest of Wadebridge, ten miles northwest of Bodmin and ten miles northeast of Newquay...

with Fowey

Fowey

Fowey is a small town, civil parish and cargo port at the mouth of the River Fowey in south Cornwall, United Kingdom. According to the 2001 census it had a population of 2,273.-Early history:...

and Lostwithiel

Lostwithiel

Lostwithiel is a civil parish and small town in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom at the head of the estuary of the River Fowey. According to the 2001 census it had a population of 2,739...

served, in Roman times, as a convenient conduit for trade between Gaul

Gaul

Gaul was a region of Western Europe during the Iron Age and Roman era, encompassing present day France, Luxembourg and Belgium, most of Switzerland, the western part of Northern Italy, as well as the parts of the Netherlands and Germany on the left bank of the Rhine. The Gauls were the speakers of...

(especially Armorica

Armorica

Armorica or Aremorica is the name given in ancient times to the part of Gaul that includes the Brittany peninsula and the territory between the Seine and Loire rivers, extending inland to an indeterminate point and down the Atlantic coast...

) and the western parts of the British Isles

British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands off the northwest coast of continental Europe that include the islands of Great Britain and Ireland and over six thousand smaller isles. There are two sovereign states located on the islands: the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and...

.

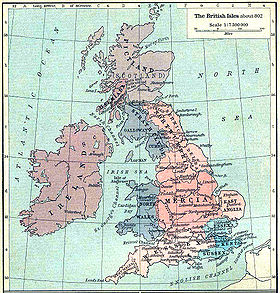

Post-Roman and Medieval periods

Great Britain

Great Britain or Britain is an island situated to the northwest of Continental Europe. It is the ninth largest island in the world, and the largest European island, as well as the largest of the British Isles...

, Saxons and other peoples were able to conquer and settle most of the east of the island. Cornwall, however, remained under the rule of local Romano-British and Celtic elites. It appears that Cornwall was a division of the Dumnonii

Dumnonii

The Dumnonii or Dumnones were a British Celtic tribe who inhabited Dumnonia, the area now known as Devon and Cornwall in the farther parts of the South West peninsula of Britain, from at least the Iron Age up to the early Saxon period...

tribe - whose tribal centre was in the modern county of Devon

Devon

Devon is a large county in southwestern England. The county is sometimes referred to as Devonshire, although the term is rarely used inside the county itself as the county has never been officially "shired", it often indicates a traditional or historical context.The county shares borders with...

and were known as the Cornovii

Cornovii (Cornish)

The Cornovii were a Celtic tribe who inhabited the far South West peninsula of Great Britain, during the Iron Age, Roman and post-Roman periods and gave their name to Cornwall or Kernow....

. During the sub-Roman historic period there is little distinction made between the Kingdom of Cornwall

Kingdom of Cornwall

The Kingdom of Cornwall was an independent polity in southwest Britain during the Early Middle Ages, roughly coterminous with the modern English county of Cornwall. During the sub-Roman and early medieval periods Cornwall was evidently part of the kingdom of Dumnonia, which included most of the...

, the Cornovii

Cornovii (Cornish)

The Cornovii were a Celtic tribe who inhabited the far South West peninsula of Great Britain, during the Iron Age, Roman and post-Roman periods and gave their name to Cornwall or Kernow....

, and Dumnonia

Dumnonia

Dumnonia is the Latinised name for the Brythonic kingdom in sub-Roman Britain between the late 4th and late 8th centuries, located in the farther parts of the south-west peninsula of Great Britain...

. Indeed the names were largely interchangeable; with Dumnonia being the Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

name for the region and "Cornwall", or rather Cornweal, being the Anglo-Saxon

Old English language

Old English or Anglo-Saxon is an early form of the English language that was spoken and written by the Anglo-Saxons and their descendants in parts of what are now England and southeastern Scotland between at least the mid-5th century and the mid-12th century...

name for them.

For most of its history, at least until the mid-8th century, the rulers of Dumnonia

Dumnonia

Dumnonia is the Latinised name for the Brythonic kingdom in sub-Roman Britain between the late 4th and late 8th centuries, located in the farther parts of the south-west peninsula of Great Britain...

were probably also the rulers of Cornwall. In Arthurian

King Arthur

King Arthur is a legendary British leader of the late 5th and early 6th centuries, who, according to Medieval histories and romances, led the defence of Britain against Saxon invaders in the early 6th century. The details of Arthur's story are mainly composed of folklore and literary invention, and...

legend Gorlois

Gorlois

Gorlois was a Duke of Cornwall and Igraine's first husband before her marriage to Uther Pendragon, according to the Arthurian legend...

(Gwrlais in Welsh

Welsh language

Welsh is a member of the Brythonic branch of the Celtic languages spoken natively in Wales, by some along the Welsh border in England, and in Y Wladfa...

) is attributed the title "Duke of Cornwall" but evidence of his existence is scant. He could have been a sub-king in Cornwall because of place names such as Carhurles (Caer-Wrlais) and Treworlas (Tre-Wrlais). There was almost certainly a King Mark of Cornwall

Mark of Cornwall

Mark of Cornwall was a king of Kernow in the early 6th century. He is most famous for his appearance in Arthurian legend as the uncle of Tristan and husband of Iseult, who engage in a secret affair.-The legend:Mark sent Tristan as his proxy to fetch his young bride, the Princess Iseult, from...

. After the loss of most of the territory today called Devon

Devon

Devon is a large county in southwestern England. The county is sometimes referred to as Devonshire, although the term is rarely used inside the county itself as the county has never been officially "shired", it often indicates a traditional or historical context.The county shares borders with...

, the British rulers are referred to either as the kings of Cornwall or the kings of the "West Welsh".

This is also the period known as the 'age of the saints', as Celtic Christianity

Celtic Christianity

Celtic Christianity or Insular Christianity refers broadly to certain features of Christianity that were common, or held to be common, across the Celtic-speaking world during the Early Middle Ages...

and a revival of Celtic art

Celtic art

Celtic art is the art associated with the peoples known as Celts; those who spoke the Celtic languages in Europe from pre-history through to the modern period, as well as the art of ancient peoples whose language is uncertain, but have cultural and stylistic similarities with speakers of Celtic...

spread from Ireland

Ireland

Ireland is an island to the northwest of continental Europe. It is the third-largest island in Europe and the twentieth-largest island on Earth...

and Scotland

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

into Great Britain, Brittany

Brittany

Brittany is a cultural and administrative region in the north-west of France. Previously a kingdom and then a duchy, Brittany was united to the Kingdom of France in 1532 as a province. Brittany has also been referred to as Less, Lesser or Little Britain...

, and beyond. Cornish saints such as Piran

Saint Piran

Saint Piran or Perran is an early 6th century Cornish abbot and saint, supposedly of Irish origin....

, Meriasek, or Geraint

Geraint

Geraint is a character from Welsh folklore and Arthurian legend, a king of Dumnonia and a valiant warrior. He may have lived during or shortly prior to the reign of the historical Arthur, but some scholars doubt he ever existed...

exercised a religious and arguably political influence; their activities also connected Cornwall strongly with Ireland, Brittany, Scotland, and Wales, where many of these saints were trained or formed monasteries. The Cornish saints were often closely connected to the local civil rulers; in a number of cases, the saints were also kings.

Kingdom of Cornwall

A Kingdom of CornwallKingdom of Cornwall

The Kingdom of Cornwall was an independent polity in southwest Britain during the Early Middle Ages, roughly coterminous with the modern English county of Cornwall. During the sub-Roman and early medieval periods Cornwall was evidently part of the kingdom of Dumnonia, which included most of the...

emerged around the 6th century; its kings were at first sub-kings and then successors of the Brythonic Celtic Kingdom of Dumnonia

Dumnonia

Dumnonia is the Latinised name for the Brythonic kingdom in sub-Roman Britain between the late 4th and late 8th centuries, located in the farther parts of the south-west peninsula of Great Britain...

. The political situation was much in flux, and several kings or polities appear to have exercised sovereignty across the Channel in Brittany. Meanwhile the Saxons of Wessex

Wessex

The Kingdom of Wessex or Kingdom of the West Saxons was an Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the West Saxons, in South West England, from the 6th century, until the emergence of a united English state in the 10th century, under the Wessex dynasty. It was to be an earldom after Canute the Great's conquest...

were rapidly approaching from the east and crushing the kingdom of Dumnonia

Dumnonia

Dumnonia is the Latinised name for the Brythonic kingdom in sub-Roman Britain between the late 4th and late 8th centuries, located in the farther parts of the south-west peninsula of Great Britain...

. In 721

721

Year 721 was a common year starting on Wednesday of the Julian calendar. The denomination 721 for this year has been used since the early medieval period, when the Anno Domini calendar era became the prevalent method in Europe for naming years.- Byzantine Empire :* Former Byzantine emperor...

the Britons defeated the West Saxons at "Hehil" (Annales Cambriae). A century passed before we specifically hear of the West Saxons attacking Cornwall again, although the "Welsh" who fought a battle against King Cuthred

Cuthred of Wessex

Cuthred or Cuþræd was the King of Wessex from 740 until 756. He succeeded Æthelheard, his relative and possibly his brother....

in 753 were probably from this area. In 814 King Egbert

Egbert of Wessex

Egbert was King of Wessex from 802 until his death in 839. His father was Ealhmund of Kent...

raided Cornwall "& þy geare gehergade Ecgbryht cyning on West Walas from easteweardum oþ westewearde."... and in this year king Ecgbryht raided in Cornwall from east to west. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is a collection of annals in Old English chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The original manuscript of the Chronicle was created late in the 9th century, probably in Wessex, during the reign of Alfred the Great...

tells us that in 825 (adjusted date) the Battle of Gafulforda, unidentified but perhaps Galford

Lew Trenchard

Lew Trenchard is a parish and village in west Devon, England. Most of the larger village of Lewdown is in the parish. In Domesday Book a manor of Lew is recorded in this area and two rivers have the same name: see River Lew. Trenchard comes from the lords of the manor in the 13th century...

, near Lydford

Lydford

Lydford, sometimes spelled Lidford, is a village, once an important town, in Devon situated north of Tavistock on the western fringe of Dartmoor in the West Devon district.-Description:The village has a population of 458....

in Devon took place: "The West Wealas (Cornish) and the men of Defnas (Devon) fought at Gafalforda". In 838

838

Year 838 was a common year starting on Tuesday of the Julian calendar.- Asia :* The Byzantine emperor Theophilos is heavily defeated at the Battle of Anzen by the Abbasids...

the Cornish in alliance with the Danes were defeated by Egbert of Wessex at Hingston Down

Hingston Down, Devon

Hingston Down is a hill spur approximately one mile east of Moretonhampstead and 10 miles west of Exeter in Devon. Some historians now claim that this was the site of the 838 battle between a Cornish/Danish alliance against the West Saxons rather than at the site at Hingston Down near Callington,...

where the Wealas and the Danes were "put to flight". The Annales Cambriae records that in 875, king Dungarth

Donyarth

King Donyarth is thought to have been a 9th century King of Cornwall, now part of the United Kingdom.He is known solely from an inscription on King Doniert's Stone, a 9th century cross shaft which stands in St Cleer parish in Cornwall. His social status is not recorded there...

of Cerniu ("id est Cornubiae") drowns. The Kingdom of Cornwall was also the setting for Gottfried von Strassburg

Gottfried von Strassburg

Gottfried von Strassburg is the author of the Middle High German courtly romance Tristan and Isolt, an adaptation of the 12th-century Tristan and Iseult legend. Gottfried's work is regarded, alongside Wolfram von Eschenbach's Parzival and the Nibelungenlied, as one of the great narrative...

's courtly epic Tristan und Isolde (c1200).

Changes in the Cornish Church

By the 880s the Church in Cornwall was having more Saxon priests appointed to it and they controlled some church estates like Polltun, Caellwic and Landwithan (Pawton, in St BreockSt Breock

St Breock is a village and a civil parish in north Cornwall, United Kingdom. St Breock village is 1 mile west of Wadebridge immediately to the south of the Royal Cornwall Showground. The village lies on the eastern slope of the wooded Nansent valley...

; perhaps Celliwig

Celliwig

Celliwig, Kelliwic or Gelliwic, is perhaps the earliest named location for the court of King Arthur. It may be translated as 'forest grove'.-Literary references:...

(Kellywick in Egloshayle

Egloshayle

Egloshayle is a civil parish and village in north Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. The village is situated beside the River Camel immediately southeast of Wadebridge. The civil parish extends southeast from the village and includes Washaway and Sladesbridge.-History:Egloshayle was a Bronze Age...

?); and Lawhitton

Lawhitton

Lawhitton is a civil parish and village in east Cornwall, United Kingdom. The village is situated two miles southwest of Launceston and half-a-mile west of Cornwall's border with Devon at the River Tamar....

. Eventually they passed these over to Wessex kings. However according to Alfred the Great

Alfred the Great

Alfred the Great was King of Wessex from 871 to 899.Alfred is noted for his defence of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of southern England against the Vikings, becoming the only English monarch still to be accorded the epithet "the Great". Alfred was the first King of the West Saxons to style himself...

's will the amount of land he owned in Cornwall was very small. West of the Tamar Alfred the Great

Alfred the Great

Alfred the Great was King of Wessex from 871 to 899.Alfred is noted for his defence of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of southern England against the Vikings, becoming the only English monarch still to be accorded the epithet "the Great". Alfred was the first King of the West Saxons to style himself...

only owned a small area in the Stratton

Stratton, Cornwall

Stratton is a small town situated near the coastal resort of Bude in north Cornwall, UK. It was also the name of one of ten ancient administrative shires of Cornwall - see "Hundreds of Cornwall"...

region, plus a few other small estates around Lifton on Cornish soil east of the Tamar). These were provided to him illicitly through the Church whose Canterbury appointed priesthood was increasingly English dominated. William of Malmesbury

William of Malmesbury

William of Malmesbury was the foremost English historian of the 12th century. C. Warren Hollister so ranks him among the most talented generation of writers of history since Bede, "a gifted historical scholar and an omnivorous reader, impressively well versed in the literature of classical,...

, writing around 1120, says that King Athelstan of England (924–939) fixed Cornwall's eastern boundary at the Tamar

River Tamar

The Tamar is a river in South West England, that forms most of the border between Devon and Cornwall . It is one of several British rivers whose ancient name is assumed to be derived from a prehistoric river word apparently meaning "dark flowing" and which it shares with the River Thames.The...

and the remaining Cornish were evicted from Exeter

Exeter

Exeter is a historic city in Devon, England. It lies within the ceremonial county of Devon, of which it is the county town as well as the home of Devon County Council. Currently the administrative area has the status of a non-metropolitan district, and is therefore under the administration of the...

and perhaps the rest of Devon - "Exeter was cleansed of its defilement by wiping out that filthy race". These British speakers were deported across the Tamar, which was fixed as the border of the Cornish; they were left under their own dynasty to regulate themselves with west Welsh tribal law and customs, rather like the Indian princes under the Raj. By 944 Athelstan's successor, Edmund I of England

Edmund I of England

Edmund I , called the Elder, the Deed-doer, the Just, or the Magnificent, was King of England from 939 until his death. He was a son of Edward the Elder and half-brother of Athelstan. Athelstan died on 27 October 939, and Edmund succeeded him as king.-Military threats:Shortly after his...

, styled himself 'King of the English and ruler of this province of the Britons', an indication of how that accommodation was understood at the time.

The early organisation and affiliations of the Church in Cornwall are unclear, but in the mid-ninth century it was led by a Bishop Kenstec

Kenstec

Kenstec was a medieval Bishop of Cornwall.He was consecrated between 833 and 870. His death date is unknown.-References:* Powicke, F. Maurice and E. B. Fryde Handbook of British Chronology 2nd. ed. London:Royal Historical Society 1961-External links:...

with his see at Dinurrin, a location which has sometimes been identified as Bodmin

Bodmin

Bodmin is a civil parish and major town in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It is situated in the centre of the county southwest of Bodmin Moor.The extent of the civil parish corresponds fairly closely to that of the town so is mostly urban in character...

and sometimes as Gerrans

Gerrans

Gerrans is a coastal civil parish and village on the Roseland Peninsula in Cornwall, United Kingdom. The village adjoins Portscatho on the east side of the peninsula...

. Kenstec acknowledged the authority of Ceolnoth

Ceolnoth

-Biography:Gervase of Canterbury says that Ceolnoth was Dean of the see of Canterbury previous to being elected to the archiepiscopal see of Canterbury, but this story has no confirmation in contemporary records. Ceolnoth was consecrated archbishop on 27 July 833...

, bringing Cornwall under the jurisdiction of the Archbishop of Canterbury

Archbishop of Canterbury

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and principal leader of the Church of England, the symbolic head of the worldwide Anglican Communion, and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. In his role as head of the Anglican Communion, the archbishop leads the third largest group...

. In the 920s or 930s King Athelstan established a bishopric at St Germans

St German's Priory

St German's Priory is a large Norman church in the village of St Germans in south-east Cornwall, in the United Kingdom.-History:According to a credible tradition the church here was founded by St Germanus himself ca. 430 AD. The first written record however is of Conan being made Bishop in the...

to cover the whole of Cornwall, which seems to have been initially subordinated to the see of Sherborne

Sherborne

Sherborne is a market town in northwest Dorset, England. It is sited on the River Yeo, on the edge of the Blackmore Vale, east of Yeovil. The A30 road, which connects London to Penzance, runs through the town. The population of the town is 9,350 . 27.1% of the population is aged 65 or...

but emerged as a full bishopric in its own right by the end of the tenth century. The first few bishops here were native Cornish, but those appointed from 963 onwards were all English. From around 1027 the see was held jointly with that of Crediton

Bishop of Crediton

The Bishop of Crediton was originally a prelate who administered an Anglo-Saxon diocese in the 10th and 11th centuries, and is presently a suffragan bishop who assists the diocesan bishop.-Diocesan Bishops of Crediton:...

, and in 1050 they were merged to become the diocese of Exeter

Bishop of Exeter

The Bishop of Exeter is the Ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Exeter in the Province of Canterbury. The incumbent usually signs his name as Exon or incorporates this in his signature....

.

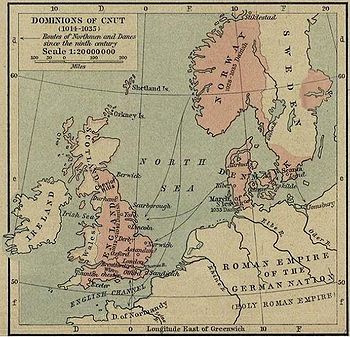

The eleventh century

Wessex

The Kingdom of Wessex or Kingdom of the West Saxons was an Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the West Saxons, in South West England, from the 6th century, until the emergence of a united English state in the 10th century, under the Wessex dynasty. It was to be an earldom after Canute the Great's conquest...

, Cornwall's neighbour, was conquered by a Danish army under the leadership of the Viking leader and King of Denmark Sweyn Forkbeard. Sweyn annexed Wessex to his Viking empire which included Denmark and Norway. He did not, however, annex Cornwall, Wales and Scotland, allowing these "client nations" self rule in return for an annual payment of tribute or "danegeld". Between 1013-1035 the Kingdom of Cornwall

Kingdom of Cornwall

The Kingdom of Cornwall was an independent polity in southwest Britain during the Early Middle Ages, roughly coterminous with the modern English county of Cornwall. During the sub-Roman and early medieval periods Cornwall was evidently part of the kingdom of Dumnonia, which included most of the...

, Wales

Wales

Wales is a country that is part of the United Kingdom and the island of Great Britain, bordered by England to its east and the Atlantic Ocean and Irish Sea to its west. It has a population of three million, and a total area of 20,779 km²...

, much of Scotland

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

and Ireland

Ireland

Ireland is an island to the northwest of continental Europe. It is the third-largest island in Europe and the twentieth-largest island on Earth...

were not included in the territories of King Canute the Great

Canute the Great

Cnut the Great , also known as Canute, was a king of Denmark, England, Norway and parts of Sweden. Though after the death of his heirs within a decade of his own and the Norman conquest of England in 1066, his legacy was largely lost to history, historian Norman F...

.

The chronology of English expansion into Cornwall is unclear, but it had been absorbed into England by the reign of Edward the Confessor

Edward the Confessor

Edward the Confessor also known as St. Edward the Confessor , son of Æthelred the Unready and Emma of Normandy, was one of the last Anglo-Saxon kings of England and is usually regarded as the last king of the House of Wessex, ruling from 1042 to 1066....

(1042–1066), when it apparently formed part of Godwin's

Godwin, Earl of Wessex

Godwin of Wessex , was one of the most powerful lords in England under the Danish king Cnut the Great and his successors. Cnut made him the first Earl of Wessex...

and later Harold's

Harold Godwinson

Harold Godwinson was the last Anglo-Saxon King of England.It could be argued that Edgar the Atheling, who was proclaimed as king by the witan but never crowned, was really the last Anglo-Saxon king...

earldom of Wessex. The records of Domesday Book show that by this time the native Cornish landowning class had been almost completely dispossessed and replaced by English landowners, the largest of whom was Harold Godwinson himself. The Cornish language

Cornish language

Cornish is a Brythonic Celtic language and a recognised minority language of the United Kingdom. Along with Welsh and Breton, it is directly descended from the ancient British language spoken throughout much of Britain before the English language came to dominate...

continued to be spoken, particularly in western and central Cornwall, and acquired a number of characteristics establishing its identity as a separate language from Breton

Breton language

Breton is a Celtic language spoken in Brittany , France. Breton is a Brythonic language, descended from the Celtic British language brought from Great Britain to Armorica by migrating Britons during the Early Middle Ages. Like the other Brythonic languages, Welsh and Cornish, it is classified as...

. However Cornwall showed a very different type of settlement pattern from that of Saxon Wessex and places continued, even after 1066, to be named in the Celtic Cornish tradition. The earliest record for any English place names west of the Tamar is around 1040.

1066-1485

William Worcester

William Worcester , was an English chronicler and antiquary.-Life:He was a son of William of Worcester, a Bristol citizen, and is sometimes called William Botoner, his mother being a daughter of Thomas Botoner from Catalonia....

, writing in the fifteenth century, Cadoc

Cadoc of Cornwall

According to William of Worcester, writing in the fifteenth century, Cadoc was a survivor of the Cornish royal line at the time of the Norman Conquest of England in 1066 and was appointed as the first Earl of Cornwall by William the Conqueror....

(Cornish: Kadog) was a survivor of the Cornish royal line and was appointed as the first Earl of Cornwall by William the Conqueror following the Norman conquest of England

Norman conquest of England

The Norman conquest of England began on 28 September 1066 with the invasion of England by William, Duke of Normandy. William became known as William the Conqueror after his victory at the Battle of Hastings on 14 October 1066, defeating King Harold II of England...

. Brian

Brian of Brittany

Brian of Brittany in English, or Brien de Bretagne in French, was a Breton noble who fought for William I of England. He was born in about 1042, the second son of Odo, Count of Penthièvre...

, son of Eudes, Count of Penthièvre

Eudes, Count of Penthievre

Odo of Rennes , Count of Penthièvre, was the youngest son of Duke Geoffrey I of Brittany and Hawise of Normandy, daughter of Richard I of Normandy. Following the death of his brother Duke Alan III, Eudes ruled as regent of Brittany in the name of his nephew Conan II, between 1040 and 1062...

, defeated a second raid in the southwest of England, launched from Ireland by Harold

Harold Godwinson

Harold Godwinson was the last Anglo-Saxon King of England.It could be argued that Edgar the Atheling, who was proclaimed as king by the witan but never crowned, was really the last Anglo-Saxon king...

's sons in 1069. Brian was granted lands in Cornwall but by 1072 he had probably returned to Brittany: he died without issue. However, much of the land in Cornwall was seized and transferred into the hands of a new Norman aristocracy, with the lion's share going to Robert, Count of Mortain

Robert, Count of Mortain

Robert, Count of Mortain, 1st Earl of Cornwall was a Norman nobleman and the half-brother of William I of England. Robert was the son of Herluin de Conteville and Herleva of Falaise and was full brother to Odo of Bayeux. The exact year of Robert's birth is unknown Robert, Count of Mortain, 1st...

, half-brother of King William

William I of England

William I , also known as William the Conqueror , was the first Norman King of England from Christmas 1066 until his death. He was also Duke of Normandy from 3 July 1035 until his death, under the name William II...

and the largest landholder in England after the king, while some was held by King William and by existing monasteries (the remainder by the Bishop of Exeter, and a single manor each by Judhael of Totnes and Gotshelm). Robert eventually displaced the Cornish Earl though nothing is known of Cadoc apart from what William Worcester says four centuries later. Four Norman castles were built in east Cornwall at different periods, at Launceston

Launceston Castle

Launceston Castle is located in the town of Launceston, Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. .-Early history:The castle is a Norman motte and bailey earthwork castle raised by Robert, Count of Mortain, half-brother of William the Conqueror shortly after the Norman conquest, possibly as early as 1067...

, Trematon

Trematon

Trematon is a village in Cornwall, England, about two miles from the town of Saltash and part of the civil parish of St Stephens-by-Saltash.-History:Trematon appears in the Domesday Book as the manor of "Tremetone"....

, Restormel

Restormel Castle

Restormel Castle is situated on the River Fowey near Lostwithiel, Cornwall, United Kingdom. It is one of the four chief Norman castles of Cornwall, the others being Launceston, Tintagel and Trematon. The castle is notable for its perfectly circular design...

and Tintagel. A new town grew up around the castle and this became the capital of the county. On several occasions over the following centuries noblemen were created Earl of Cornwall

Earl of Cornwall

The title of Earl of Cornwall was created several times in the Peerage of England before 1337, when it was superseded by the title Duke of Cornwall, which became attached to heirs-apparent to the throne.-Earl of Cornwall:...

, but each time their line soon died out and the title lapsed until revived for a new appointee. In 1336, Edward, the Black Prince

Edward, the Black Prince

Edward of Woodstock, Prince of Wales, Duke of Cornwall, Prince of Aquitaine, KG was the eldest son of King Edward III of England and his wife Philippa of Hainault as well as father to King Richard II of England....

was named Duke of Cornwall

Duke of Cornwall

The Duchy of Cornwall was the first duchy created in the peerage of England.The present Duke of Cornwall is The Prince of Wales, the eldest son of Queen Elizabeth II, the reigning British monarch .-History:...

, a title that has been awarded to the eldest son of the Sovereign since 1421. The Duke is the Sovereign of Cornwall and the Duchy extends over the entire territory of Cornwall and the sea surrounding it; the landholdings of the Duchy however are only partly in Cornwall.

A popular Cornish literature, centred on the religious-themed mystery play

Mystery play

Mystery plays and miracle plays are among the earliest formally developed plays in medieval Europe. Medieval mystery plays focused on the representation of Bible stories in churches as tableaux with accompanying antiphonal song...

s, emerged in the 14th century (see Cornish literature) based around Glasney College

Glasney College

Glasney College was founded in 1265 at Penryn, Cornwall, by Bishop Bronescombe and was a centre of ecclesiastical power in medieval Cornwall and probably the best known and most important of Cornwall's religious institutions.-History:...

—the college established by the Bishop of Exeter in the 13th century.

1485-1558

The general tendency of administrative centralization under the Tudor dynasty began to undermine Cornwall's distinctive status. For example, under the Tudors, laws were no longer specified to apply in Anglia et Cornubia (in England and Cornwall); instead, Anglia was taken to include Cornubia.The Cornish Rebellion of 1497

Cornish Rebellion of 1497

The Cornish Rebellion of 1497 was a popular uprising by the people of Cornwall in the far southwest of Britain. Its primary cause was a response of people to the raising of war taxes by King Henry VII on the impoverished Cornish, to raise money for a campaign against Scotland motivated by brief...

originated among Cornish tin miners who opposed the raising of taxes by Henry VII

Henry VII of England

Henry VII was King of England and Lord of Ireland from his seizing the crown on 22 August 1485 until his death on 21 April 1509, as the first monarch of the House of Tudor....

in order to make war on Scotland

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

. This levy was resented for the economic hardship it would cause; it also intruded on a special Cornish tax exemption. The rebels marched on London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

, gaining supporters as they went, but were defeated at the Battle of Deptford

Deptford

Deptford is a district of south London, England, located on the south bank of the River Thames. It is named after a ford of the River Ravensbourne, and from the mid 16th century to the late 19th was home to Deptford Dockyard, the first of the Royal Navy Dockyards.Deptford and the docks are...

Bridge.

The Cornish also rose up in the Prayer Book Rebellion

Prayer Book Rebellion

The Prayer Book Rebellion, Prayer Book Revolt, Prayer Book Rising, Western Rising or Western Rebellion was a popular revolt in Cornwall and Devon, in 1549. In 1549 the Book of Common Prayer, presenting the theology of the English Reformation, was introduced...

of 1549. Much of south-western Britain rebelled against the Act of Uniformity 1549

Act of Uniformity 1549

The Act of Uniformity 1549 established The Book of Common Prayer as the sole legal form of worship in England...

, which introduced the obligatory use of the Protestant Book of Common Prayer

Book of Common Prayer

The Book of Common Prayer is the short title of a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion, as well as by the Continuing Anglican, "Anglican realignment" and other Anglican churches. The original book, published in 1549 , in the reign of Edward VI, was a product of the English...

. Cornwall was mostly Catholic in sympathy at this time; the Act was doubly resented in Cornwall because the Prayer Book was in English

English language

English is a West Germanic language that arose in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of England and spread into what was to become south-east Scotland under the influence of the Anglian medieval kingdom of Northumbria...

only and most Cornish people

Cornish people

The Cornish are a people associated with Cornwall, a county and Duchy in the south-west of the United Kingdom that is seen in some respects as distinct from England, having more in common with the other Celtic parts of the United Kingdom such as Wales, as well as with other Celtic nations in Europe...

at this time spoke the Cornish language rather than English. They therefore wished church services to continue to be conducted in Latin; although they did not understand this language either, it had the benefit of long-established tradition and lacked the political and cultural connotations of the use of English. Twenty percent of the Cornish population are believed to have been killed during 1549: it is one of the major factors that contributed to the decline in the Cornish language.

It is worthy of note that on many maps produced before the 17th century Cornwall was depicted as a nation of Great Britain

Great Britain

Great Britain or Britain is an island situated to the northwest of Continental Europe. It is the ninth largest island in the world, and the largest European island, as well as the largest of the British Isles...

on a par with Wales and Ireland; famous examples include Gerardus Mercator

Gerardus Mercator

thumb|right|200px|Gerardus MercatorGerardus Mercator was a cartographer, born in Rupelmonde in the Hapsburg County of Flanders, part of the Holy Roman Empire. He is remembered for the Mercator projection world map, which is named after him...

's Atlas and the Hereford Mappa Mundi

Mappa mundi

Mappa mundi is a general term used to describe medieval European maps of the world. These maps range in size and complexity from simple schematic maps an inch or less across to elaborate wall maps, the largest of which was 11 ft. in diameter...

.

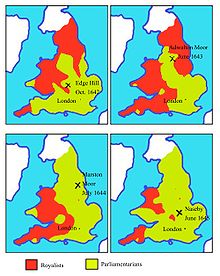

Civil War, 1642-1649

English Civil War

The English Civil War was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between Parliamentarians and Royalists...

, as it was a Royalist

Cavalier

Cavalier was the name used by Parliamentarians for a Royalist supporter of King Charles I and son Charles II during the English Civil War, the Interregnum, and the Restoration...

enclave in the generally Parliamentarian

Roundhead

"Roundhead" was the nickname given to the supporters of the Parliament during the English Civil War. Also known as Parliamentarians, they fought against King Charles I and his supporters, the Cavaliers , who claimed absolute power and the divine right of kings...

south-west. The reason for this was that Cornwall's rights and privileges were tied up with the royal Duchy

Duchy

A duchy is a territory, fief, or domain ruled by a duke or duchess.Some duchies were sovereign in areas that would become unified realms only during the Modern era . In contrast, others were subordinate districts of those kingdoms that unified either partially or completely during the Medieval era...

and Stannaries and so the Cornish saw the King as protector of their rights and Ducal privileges. The strong local Cornish identity also meant the Cornish would resist any meddling in their affairs by any outsiders. The English Parliament wanted to reduce royal power. This would include the Cornish Stannary Parliament which had powers rivalling that of the English (now British

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

) Parliament. Parliamentary forces invaded Cornwall three times and burned the Duchy archives. In 1645 Cornish Royalist leader Sir Richard Grenville, 1st Baronet

Sir Richard Grenville, 1st Baronet

Sir Richard Grenville, 1st Baronet was a Cornish Royalist leader during the English Civil War.He was the third son of Sir Bernard Grenville , and a grandson of the famous seaman, Sir Richard Grenville...

made Launceston his base and he stationed Cornish troops along the River Tamar

River Tamar

The Tamar is a river in South West England, that forms most of the border between Devon and Cornwall . It is one of several British rivers whose ancient name is assumed to be derived from a prehistoric river word apparently meaning "dark flowing" and which it shares with the River Thames.The...

and issued them with instructions to keep "all foreign troops out of Cornwall". Grenville tried to use "Cornish particularist sentiment" to muster support for the Royalist cause and put a plan to the Prince which would, if implemented, have created a semi-independent Cornwall.

18th and 19th centuries

1755 Tsunami

On 1 November 1755 at 09:40 the Lisbon earthquake caused a tsunamiTsunami

A tsunami is a series of water waves caused by the displacement of a large volume of a body of water, typically an ocean or a large lake...

to strike the Cornish coast at around 14:00. The epicentre was approximately 250 miles (402.3 km) off Cape St Vincent on the Portuguese

Portugal

Portugal , officially the Portuguese Republic is a country situated in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula. Portugal is the westernmost country of Europe, and is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the West and South and by Spain to the North and East. The Atlantic archipelagos of the...

coast, over 1000 miles (1,609.3 km) south west of the Lizard. At St Michael's Mount

St Michael's Mount

St Michael's Mount is a tidal island located off the Mount's Bay coast of Cornwall, United Kingdom. It is a civil parish and is united with the town of Marazion by a man-made causeway of granite setts, passable between mid-tide and low water....

, the sea rose suddenly and then retired, ten minutes later it rose 6 ft (1.8 m) feet very rapidly, then ebbed equally rapidly, and continued to rise and fall for five hours. The sea rose 8 ft (2.4 m) in Penzance

Penzance

Penzance is a town, civil parish, and port in Cornwall, England, in the United Kingdom. It is the most westerly major town in Cornwall and is approximately 75 miles west of Plymouth and 300 miles west-southwest of London...

and 10 ft (3 m) at Newlyn

Newlyn

Newlyn is a town and fishing port in southwest Cornwall, England, United Kingdom.Newlyn forms a conurbation with the neighbouring town of Penzance and is part of Penzance civil parish...

. The same effect was reported at St Ives and Hayle. The 18th century French writer, Arnold Boscowitz, claimed that "great loss of life and property occurred upon the coasts of Cornwall".

Developments in tin mining

Mining

Mining is the extraction of valuable minerals or other geological materials from the earth, from an ore body, vein or seam. The term also includes the removal of soil. Materials recovered by mining include base metals, precious metals, iron, uranium, coal, diamonds, limestone, oil shale, rock...

(See Mining in Cornwall and Devon ) and a School of Mines

Camborne School of Mines

The Camborne School of Mines , commonly abbreviated to CSM, was founded in 1888. It is now a specialist department of the University of Exeter. Its research and teaching is related to the understanding and management of the Earth's natural processes, resources and the environment...

was established in 1888. As Cornwall's reserves of tin began to be exhausted, many Cornishmen emigrated to places such as the Americas, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa where their skills were in demand. There is no current tin mining undertaken in Cornwall, however a popular legend says that wherever you may go in the world, if you see a hole in the ground, you'll find a Cornishman at the bottom of it. Several Cornish mining words are in use in English language mining terminology, such as costean

Costean

Costeaning is the process by which miners seek to discover metallic lodes. It consist in sinking small pits through the superficial deposits to the solid rock, and then driving from one pit to another across the direction of the vein, in such manner as to cross all the veins between the two pits....

, gunnies

Gunnies

Gunnies or gunnis is a mining term derived from the Cornish language. It refers to open-cast mines. An example is to be found at Porthtowan near St Agnes in Cornwall. The word can also mean the empty space left by removing the lode from a mine, or the width of this space....

, and vug

Vug

Vugs are small to medium-sized cavities inside rock that may be formed through a variety of processes. Most commonly cracks and fissures opened by tectonic activity are partially filled by quartz, calcite, and other secondary minerals. Open spaces within ancient collapse breccias are another...

.

Since the decline of tin mining, agriculture and fishing, the area's economy has become increasingly dependent on tourism— some of Britain's most spectacular coastal scenery can be found here. However Cornwall is one of the poorest parts of Western Europe and it has been granted Objective 1 status by the EU.

Politics, religion and administration

Cornwall and Devon were the site of a Jacobite rebellion in 1715Jacobite uprising in Cornwall of 1715

The Jacobite uprising in Cornwall of 1715 was the last uprising against the British Crown to take place in the county of Cornwall.-Background information to the event:...

led by James Paynter

James Paynter (Jacobite)

James Paynter was the leader of a Jacobite uprising in Cornwall in the 18th century.In 1715 he took an active part in proclaiming James Francis Edward Stuart on the death of Queen Anne, for this he was tried at Launceston and acquitted and welcomed by "bonfire and by ball" from thence to the...

of St. Columb. This coincided with the larger and better-known "Fifteen Rebellion"

Jacobite Rising of 1715

The Jacobite rising of 1715, often referred to as The 'Fifteen, was the attempt by James Francis Edward Stuart to regain the British throne for the exiled House of Stuart.-Background:...

which took place in Scotland and the north of England. However the Cornish uprising was quickly quashed by the authorities. James Paynter was tried for High Treason but claiming his right as a Cornish tinner was tried in front of a jury of other Cornish tinners and was cleared.

Industrialised communities have long appeared to weaken the pre-eminence of the Church of England

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

, and as the Cornish people were readily involved in mining, a rift developed between the Cornish people and their Anglican

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

clergy in the early eighteenth-century. Resisting the established church

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

, many ordinary Cornish people were Roman Catholic or non-religious until the late 18th century, when Methodism

Methodism

Methodism is a movement of Protestant Christianity represented by a number of denominations and organizations, claiming a total of approximately seventy million adherents worldwide. The movement traces its roots to John Wesley's evangelistic revival movement within Anglicanism. His younger brother...

was introduced to Cornwall during a series of visits by John

John Wesley

John Wesley was a Church of England cleric and Christian theologian. Wesley is largely credited, along with his brother Charles Wesley, as founding the Methodist movement which began when he took to open-air preaching in a similar manner to George Whitefield...

and Charles Wesley

Charles Wesley

Charles Wesley was an English leader of the Methodist movement, son of Anglican clergyman and poet Samuel Wesley, the younger brother of Anglican clergyman John Wesley and Anglican clergyman Samuel Wesley , and father of musician Samuel Wesley, and grandfather of musician Samuel Sebastian Wesley...

. Methodist separation from the Church of England was made formal in 1795.

In 1841 there were ten hundreds of Cornwall

Hundreds of Cornwall

Cornwall was from Anglo-Saxon times until the 19th century divided into hundreds, some with the suffix shire as in Pydarshire, East and West Wivelshire and Powdershire which were first recorded as names between 1184-1187. In the Cornish language the word for "hundred" is keverang and is the...

: Stratton, Lesnewth

Lesnewth (hundred)

Lesnewth Hundred is one of the former hundreds of Cornwall, Trigg was to the south-west and Stratton Hundred to the north-east. Tintagel, Camelford, Boscastle, and Altarnun were in the Hundred of Lesnewth as well as Lesnewth which is now only a small village but in Celtic times was the seat of a...

and Trigg

Triggshire

The hundred of Trigg was one of ten ancient administrative shires of Cornwall--see "Hundreds of Cornwall".Trigg is mentioned by name during the 7th century, as "Pagus Tricurius", "land of three war hosts". It was to the north of Cornwall, and included Bodmin Moor, Bodmin and the district to the...

; East

Wivelshire

East Wivelshire and West Wivelshire are two of the ancient Hundreds of Cornwall.East and West must have originally had a Cornish name but it is not recorded - see Lost wydhyel; the second element gwydhyow meaning 'trees' -...

and West

Wivelshire

East Wivelshire and West Wivelshire are two of the ancient Hundreds of Cornwall.East and West must have originally had a Cornish name but it is not recorded - see Lost wydhyel; the second element gwydhyow meaning 'trees' -...

; Powder; Pydar; Kerrier

Kerrier (hundred)

The hundred of Kerrier was the name of one of ten ancient administrative shires of Cornwall, in the United Kingdom. Kerrier is thought by Charles Thomas to be derived from an obsolete name of Castle Pencaire on Tregonning Hill, Breage...

; Penwith

Penwith (hundred)

The hundred of Penwith was the name of one of ten ancient administrative shires of Cornwall, England. The ancient hundred of Penwith was larger than the local government district of Penwith which took its name...

; and Scilly. The shire

Shire

A shire is a traditional term for a division of land, found in the United Kingdom and in Australia. In parts of Australia, a shire is an administrative unit, but it is not synonymous with "county" there, which is a land registration unit. Individually, or as a suffix in Scotland and in the far...

suffix has been attached to several of these, notably: the first three formed Triggshire; East and West appear to be divisions of Wivelshire

Wivelshire

East Wivelshire and West Wivelshire are two of the ancient Hundreds of Cornwall.East and West must have originally had a Cornish name but it is not recorded - see Lost wydhyel; the second element gwydhyow meaning 'trees' -...

; Powdershire and Pydarshire. The old names of Kerrier and Penwith have been re-used for modern local government districts. The ecclesiastical division within Cornwall into rural deaneries used versions of the same names though the areas did not correspond exactly: Trigg Major, Trigg Minor, East Wivelshire, West Wivelshire, Powder, Pydar, Kerrier and Penwith were all deaneries of the Diocese of Exeter

Diocese of Exeter

The Diocese of Exeter is a Church of England diocese covering the county of Devon. It is one of the largest dioceses in England. The Cathedral Church of Saint Peter in Exeter is the seat of the diocesan bishop, the Right Reverend Michael Langrish, Bishop of Exeter. It is part of the Province of...

but boundaries were altered in 1875 when five more deaneries were created (from December 1876 all in the Diocese of Truro

Diocese of Truro

The Diocese of Truro is a Church of England diocese in the Province of Canterbury.-Geography and history:The diocese's area is that of the county of Cornwall including the Isles of Scilly. It was formed on 15 December 1876 from the Archdeaconry of Cornwall in the Diocese of Exeter, it is thus one...

).

20th and 21st centuries

A revival of interest in Cornish studies began in the early 20th century with the work of Henry JennerHenry Jenner

Henry Jenner FSA was a British scholar of the Celtic languages, a Cornish cultural activist, and the chief originator of the Cornish language revival....

and the building of links with the other five Celtic nations.

A political party, Mebyon Kernow

Mebyon Kernow

Mebyon Kernow is a left-of-centre political party in Cornwall, United Kingdom. It primarily campaigns for devolution to Cornwall in the form of a Cornish Assembly, as well as social democracy and environmental protection.MK was formed as a pressure group in 1951, and contained as members activists...

, was formed in 1951 to attempt to serve the interests of Cornwall and to support greater self-government

Cornish self-government movement

Cornish nationalism is an umbrella term that refers to a cultural, political and social movement based in Cornwall, the most southwestern part of the island of Great Britain, which has for centuries been administered as part of England, within the United Kingdom...

for the county. The party has had elected a number of members to county, district, town and parish councils but has had no national success, although the more widespread use of the Flag of St Piran

Saint Piran's Flag

Saint Piran's Flag is the flag of Cornwall, in the United Kingdom. The earliest known description of the flag as the Standard of Cornwall was written in 1838. It is used by Cornish people as a symbol of identity. It is a white cross on a black background....

has been accredited to this party.

Recently there have been some developments in the recognition of Cornish identity or ethnicity. In 2001 for the first time in the UK

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

the inhabitants of Cornwall could record their ethnicity as Cornish on the national census

Census

A census is the procedure of systematically acquiring and recording information about the members of a given population. It is a regularly occurring and official count of a particular population. The term is used mostly in connection with national population and housing censuses; other common...

, and in 2004 the schools census in Cornwall carried a Cornish option as a subdivision of white British.

See also

- Timeline of Cornish historyTimeline of Cornish history-400,000 - 200,000 BC :* Ancestors of modern humans visited Cornwall for the first time; Cornwall is too far south to be under the ice sheet, and is joined to Continental Europe.-10,000 BC :...

- Constitutional status of CornwallConstitutional status of CornwallCornwall is currently administered as a unitary authority and ceremonial county of England.However, a number of organisations and individuals question the constitutional basis for the administration of Cornwall as part of England, arguing that the Duchy Charters of 1337 place the governance of...

- List of Cornish soldiers, commanders and sailors

Further reading