Constitutional status of Cornwall

Encyclopedia

Unitary authorities of England

Unitary authorities of England are areas where a single local authority is responsible for a variety of services for a district that elsewhere are administered separately by two councils...

authority and ceremonial county of England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

.

However, a number of organisations and individuals question the constitutional basis for the administration of Cornwall

Cornwall

Cornwall is a unitary authority and ceremonial county of England, within the United Kingdom. It is bordered to the north and west by the Celtic Sea, to the south by the English Channel, and to the east by the county of Devon, over the River Tamar. Cornwall has a population of , and covers an area of...

as part of England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

, arguing that the Duchy Charters of 1337 place the governance of Cornwall with the Duchy of Cornwall

Duchy of Cornwall

The Duchy of Cornwall is one of two royal duchies in England, the other being the Duchy of Lancaster. The eldest son of the reigning British monarch inherits the duchy and title of Duke of Cornwall at the time of his birth, or of his parent's succession to the throne. If the monarch has no son, the...

rather than the English Crown. These charters and various constitutional peculiarities related to the Duchy of Cornwall are argued to distinguish Cornwall from England constitutionally, to such an extent that Cornwall should not be described as part of England in a constitutional sense. Others do not accept this argument, and assert that Cornwall is constitutionally part of England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

, citing a range of other precedents, including Cornwall's representation in the Westminster Parliament from an early date.

In ethnic and cultural terms, Cornwall and its inhabitants have at various times been referred to as "foreign" to England and the English people

English people

The English are a nation and ethnic group native to England, who speak English. The English identity is of early mediaeval origin, when they were known in Old English as the Anglecynn. England is now a country of the United Kingdom, and the majority of English people in England are British Citizens...

in various ways, including by the English themselves. One aspect of the distinct identity of Cornwall, is the Cornish language

Cornish language

Cornish is a Brythonic Celtic language and a recognised minority language of the United Kingdom. Along with Welsh and Breton, it is directly descended from the ancient British language spoken throughout much of Britain before the English language came to dominate...

which survived into the early modern period, and been revived in modern times.

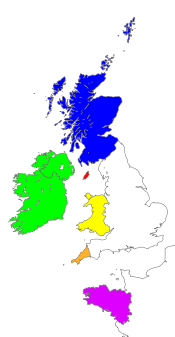

Cornish nationalists argue, whether from a legal, cultural or other basis, that Cornwall should have greater autonomy than the present administrative circumstances give. A manifestation of this is the campaign for a Cornish assembly

Cornish Assembly

The Cornish Assembly is a proposed devolved regional assembly for Cornwall in the United Kingdom along the lines of the Scottish Parliament, National Assembly for Wales and Northern Ireland Assembly.-Overview:...

, along the lines of the Welsh or Scottish

Scottish Parliament

The Scottish Parliament is the devolved national, unicameral legislature of Scotland, located in the Holyrood area of the capital, Edinburgh. The Parliament, informally referred to as "Holyrood", is a democratically elected body comprising 129 members known as Members of the Scottish Parliament...

legislative institutions. Those who assert that Cornwall is, or ought to be, separate from England, do not necessarily advocate separation from the United Kingdom. An important aim is Cornwall's recognition as a "home nation" in its own right similar to how Wales

Wales

Wales is a country that is part of the United Kingdom and the island of Great Britain, bordered by England to its east and the Atlantic Ocean and Irish Sea to its west. It has a population of three million, and a total area of 20,779 km²...

, Scotland

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

and Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland is one of the four countries of the United Kingdom. Situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, it shares a border with the Republic of Ireland to the south and west...

are considered.

Myth of origin

An ancient tale, the legend of BrutusBrutus of Troy

Brutus or Brute of Troy is a legendary descendant of the Trojan hero Æneas, known in mediæval British legend as the eponymous founder and first king of Britain...

, recounted by Geoffrey of Monmouth

Geoffrey of Monmouth

Geoffrey of Monmouth was a cleric and one of the major figures in the development of British historiography and the popularity of tales of King Arthur...

, makes explicit reference to a distinct origin of the Cornish people. The legend tells how Albion

Albion

Albion is the oldest known name of the island of Great Britain. Today, it is still sometimes used poetically to refer to the island or England in particular. It is also the basis of the Scottish Gaelic name for Scotland, Alba...

was colonised by refugees from Troy

Troy

Troy was a city, both factual and legendary, located in northwest Anatolia in what is now Turkey, southeast of the Dardanelles and beside Mount Ida...

under Brutus, who renamed his new kingdom Britain, and how the island was subsequently divided up between his three sons, the eldest inheriting Loegria (roughly modern England, Lloegr in Welsh

Welsh language

Welsh is a member of the Brythonic branch of the Celtic languages spoken natively in Wales, by some along the Welsh border in England, and in Y Wladfa...

), the other two Alba

Alba

Alba is the Scottish Gaelic name for Scotland. It is cognate to Alba in Irish and Nalbin in Manx, the two other Goidelic Insular Celtic languages, as well as similar words in the Brythonic Insular Celtic languages of Cornish and Welsh also meaning Scotland.- Etymology :The term first appears in...

nia (modern Scotland, Alba in Scottish Gaelic) and Cambria

Cambria

Cambria is the classical name for Wales, being the Latinised form of the Welsh name Cymru . The etymology of Cymry "the Welsh", Cimbri, and Cwmry "Cumbria", improbably connected to the Biblical Gomer and the "Cimmerians" by 17th-century celticists, is now known to come from Old Welsh combrog...

(modern Wales, Cymru in Welsh). In addition, according to the legend, a second and smaller group of Trojans

Troy

Troy was a city, both factual and legendary, located in northwest Anatolia in what is now Turkey, southeast of the Dardanelles and beside Mount Ida...

arrived in Britain, led by a warrior named Corineus

Corineus

Corineus, in medieval British legend, was a prodigious warrior, a fighter of giants, and the eponymous founder of Cornwall.According to Geoffrey of Monmouth's History of the Kings of Britain , he led the descendants of the Trojans who fled with Antenor after the Trojan War and settled on the coasts...

, to whom Brutus granted extensive estates. Just as Brutus had "called the island Britain...and his companions Britons", so Corineus called "the region of the kingdom which had fallen to his share Cornwall, after the manner of his own name, and the people who lived there...Cornishmen". This indicates that, at least as far as Geoffrey was concerned, Cornwall possessed an identity distinct from the other parts of Britain.

Prior to the Norman Conquest

Dumnonia

Dumnonia is the Latinised name for the Brythonic kingdom in sub-Roman Britain between the late 4th and late 8th centuries, located in the farther parts of the south-west peninsula of Great Britain...

, and was later known to the Anglo-Saxons as "West Wales", to distinguish it from "North Wales" (modern day Wales

Wales

Wales is a country that is part of the United Kingdom and the island of Great Britain, bordered by England to its east and the Atlantic Ocean and Irish Sea to its west. It has a population of three million, and a total area of 20,779 km²...

). The Anglo-Saxon word Wealh, which is retained in the last syllable of "Cornwall" meant a "foreigner", or person who did not speak the English tongue. The first element "Corn" is probably related to English "Horn" (and Latin "Cornu"), indicating the shape of the peninsula.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is a collection of annals in Old English chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The original manuscript of the Chronicle was created late in the 9th century, probably in Wessex, during the reign of Alfred the Great...

records a battle in 825 and quotes "The West Wealas (Cornish) and the Defnas (men of Devon) fought at Gafulforda". However it does not say who won or who lost, whether the men of Cornwall and Devon were fighting each other or on the same side and certainly no mention of Egbert of Wessex

Egbert of Wessex

Egbert was King of Wessex from 802 until his death in 839. His father was Ealhmund of Kent...

. "Gafulforda" is thought to be Galford near Lew Trenchard

Lew Trenchard

Lew Trenchard is a parish and village in west Devon, England. Most of the larger village of Lewdown is in the parish. In Domesday Book a manor of Lew is recorded in this area and two rivers have the same name: see River Lew. Trenchard comes from the lords of the manor in the 13th century...

on the banks of the River Lew

River Lew

The River Lew can refer to either of two short rivers that lie close to each other in Devon, England.The more northerly of the two rises just south of the village of Beaworthy, and flows east, then turns north to run past Hatherleigh before joining the River Torridge about 1 km north of the town...

(tributary of the Lyd), though some translations render it as Camelford

Camelford

Camelford is a town and civil parish in north Cornwall, United Kingdom, situated in the River Camel valley northwest of Bodmin Moor. The town is approximately ten miles north of Bodmin and is governed by Camelford Town Council....

, some 60 km further west.

References in contemporary charters (for which there is either an original manuscript or an early copy regarded as authentic) show Egbert of Wessex

Egbert of Wessex

Egbert was King of Wessex from 802 until his death in 839. His father was Ealhmund of Kent...

(802-39) granting lands in Cornwall at Kilkhampton

Kilkhampton

Kilkhampton is a village and civil parish in northeast Cornwall, United Kingdom. The village is situated on the A39 approximately four miles north-northeast of Bude.Kilkhampton was mentioned in the Domesday Book as "Chilchetone"...

, Ros, Maker, Pawton (in St Breock

St Breock

St Breock is a village and a civil parish in north Cornwall, United Kingdom. St Breock village is 1 mile west of Wadebridge immediately to the south of the Royal Cornwall Showground. The village lies on the eastern slope of the wooded Nansent valley...

, not far from Wadebridge, head manor of Pydar in Domesday Book), Caellwic (perhaps Celliwig

Celliwig

Celliwig, Kelliwic or Gelliwic, is perhaps the earliest named location for the court of King Arthur. It may be translated as 'forest grove'.-Literary references:...

or Kellywick in Egloshayle

Egloshayle

Egloshayle is a civil parish and village in north Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. The village is situated beside the River Camel immediately southeast of Wadebridge. The civil parish extends southeast from the village and includes Washaway and Sladesbridge.-History:Egloshayle was a Bronze Age...

), and Lawhitton

Lawhitton

Lawhitton is a civil parish and village in east Cornwall, United Kingdom. The village is situated two miles southwest of Launceston and half-a-mile west of Cornwall's border with Devon at the River Tamar....

to Sherborne

Sherborne

Sherborne is a market town in northwest Dorset, England. It is sited on the River Yeo, on the edge of the Blackmore Vale, east of Yeovil. The A30 road, which connects London to Penzance, runs through the town. The population of the town is 9,350 . 27.1% of the population is aged 65 or...

Abbey and to the Bishop of Sherborne. All of the identifiable locations except Pawton are in the far east of Cornwall, so these references show a degree of West Saxon control over its eastern fringes. Such control had certainly been established in places by the later ninth century, as indicated by the will of King Alfred the Great (871-99). Apart from the reference to Egbert's grant at Pawton there is no indication that English rule extended deep into Cornwall at this stage and the absence of any burhs west of Lydford in the Burghal Hidage

Burghal Hidage

The Burghal Hidage is an Anglo-Saxon document providing a list of the fortified burhs in Wessex and elsewhere in southern England. It offers an unusually detailed picture of the network of burhs that Alfred the Great designed to defend his kingdom from the predations of Viking invaders.-Burhs and...

may suggest limitations on the authority of the Kingdom of Wessex in parts of Cornwall.

King Athelstan, who came to the throne of England in 924 CE, immediately began a campaign to consolidate his power, and by about 926 had taken control of the Kingdom of Northumbria

Northumbria

Northumbria was a medieval kingdom of the Angles, in what is now Northern England and South-East Scotland, becoming subsequently an earldom in a united Anglo-Saxon kingdom of England. The name reflects the approximate southern limit to the kingdom's territory, the Humber Estuary.Northumbria was...

, following which he established firm boundaries with other kingdoms such as Scotland

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

and Cornwall. The latter agreement, according to 12th century West Country

West Country

The West Country is an informal term for the area of south western England roughly corresponding to the modern South West England government region. It is often defined to encompass the historic counties of Cornwall, Devon, Dorset and Somerset and the City of Bristol, while the counties of...

historian William of Malmesbury

William of Malmesbury

William of Malmesbury was the foremost English historian of the 12th century. C. Warren Hollister so ranks him among the most talented generation of writers of history since Bede, "a gifted historical scholar and an omnivorous reader, impressively well versed in the literature of classical,...

, ended rights of residence for Cornish subjects in Exeter

Exeter

Exeter is a historic city in Devon, England. It lies within the ceremonial county of Devon, of which it is the county town as well as the home of Devon County Council. Currently the administrative area has the status of a non-metropolitan district, and is therefore under the administration of the...

, and fixed the Cornish boundary at the east bank of the River Tamar

River Tamar

The Tamar is a river in South West England, that forms most of the border between Devon and Cornwall . It is one of several British rivers whose ancient name is assumed to be derived from a prehistoric river word apparently meaning "dark flowing" and which it shares with the River Thames.The...

. At Easter 928, Athelstan held court at Exeter, with the Welsh and "West Welsh" subject rulers present, and by 931 he had appointed a bishop for Cornwall within the English church (i.e. subject to the authority of the Archbishop of Canterbury). The Bodmin manumissions

Bodmin manumissions

The Bodmin manumissions or Bodmin Gospels is a manuscript supposed to be of the 9th century. The document is of interest to language scholars as it contains writing in Latin, Saxon and Cornish texts....

, two to three generations later, show that the ruling class of Cornwall quickly became "Anglicised", most owners of slaves having Anglo-Saxon names (not necessarily because they were of English descent; some at least were Cornish nobles who changed their names). Among those manumitting (releasing) slaves in the Bodmin record are four English kings, but no Cornish kings, dukes or earls.

It is clear that at this time areas beyond the core of Anglo-Saxon settlement were recognised as different by the English kings. Athelstan's successor, Edmund, in a charter for an estate just north of Exeter, styled himself as "King of the English, and ruler of this province of Britons." Edmund's successor Edgar styled himself, "King of the English and ruler of the adjacent nations." This was followed by king Aethelred II (978-1016) describing Cornwall not as an English shire, but as a province, or client territory.

Surviving charters issued by the Kings of England Edmund I

Edmund I of England

Edmund I , called the Elder, the Deed-doer, the Just, or the Magnificent, was King of England from 939 until his death. He was a son of Edward the Elder and half-brother of Athelstan. Athelstan died on 27 October 939, and Edmund succeeded him as king.-Military threats:Shortly after his...

(939-46), Edgar

Edgar of England

Edgar the Peaceful, or Edgar I , also called the Peaceable, was a king of England . Edgar was the younger son of Edmund I of England.-Accession:...

(959-75), Edward the Martyr

Edward the Martyr

Edward the Martyr was king of the English from 975 until he was murdered in 978. Edward was the eldest son of King Edgar, but not his father's acknowledged heir...

(975-8), Aethelred II

Ethelred the Unready

Æthelred the Unready, or Æthelred II , was king of England . He was son of King Edgar and Queen Ælfthryth. Æthelred was only about 10 when his half-brother Edward was murdered...

(978-1016), Edmund II

Edmund Ironside

Edmund Ironside or Edmund II was king of England from 23 April to 30 November 1016. His cognomen "Ironside" is not recorded until 1057, but may have been contemporary. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, it was given to him "because of his valour" in resisting the Danish invasion led by Cnut...

(1016), Cnut

Canute the Great

Cnut the Great , also known as Canute, was a king of Denmark, England, Norway and parts of Sweden. Though after the death of his heirs within a decade of his own and the Norman conquest of England in 1066, his legacy was largely lost to history, historian Norman F...

(1016–35) and Edward the Confessor

Edward the Confessor

Edward the Confessor also known as St. Edward the Confessor , son of Æthelred the Unready and Emma of Normandy, was one of the last Anglo-Saxon kings of England and is usually regarded as the last king of the House of Wessex, ruling from 1042 to 1066....

(1042–66) record grants of land in Cornwall made by these kings. In contrast to the easterly concentration of the estates held or granted by English kings in the ninth century, the tenth and eleventh-century grants were widely distributed across Cornwall. As is usual with charters of this period, the authenticity of some of these documents is open to question (though Della Hooke has established high reliability for the Cornish material), but that of others (e.g. Edgar's grant of estates at Tywarnhaile and Bosowsa to his thane

Thegn

The term thegn , from OE þegn, ðegn "servant, attendant, retainer", is commonly used to describe either an aristocratic retainer of a king or nobleman in Anglo-Saxon England, or as a class term, the majority of the aristocracy below the ranks of ealdormen and high-reeves...

Eanulf in 960, Edward the Confessor's grant of estates at Traboe

Traboe

Traboe is a hamlet within the Lizard Peninsula, Cornwall. It is approximately a mile down the road from Goonhilly Satellite Earth Station. It contains eleven houses and a building which used to house Rosuick Farm Shop, this being the purpose for which it was built. The list of houses includes a...

, Trevallack, Grugwith and Trethewey to Bishop Ealdred in 1059) is not in any doubt. Some of these grants include exemptions from obligations to the crown which would otherwise accompany land ownership, while retaining others, including those regarding military service. Assuming that these documents are authentic, the attachment of these obligations to the King of England to ownership of land in Cornwall suggests that the area was under his direct rule and implies that the legal and administrative relationship between the king and his subjects was the same there as elsewhere in his kingdom.

In 1051, with the exile of Godwin, Earl of Wessex

Godwin, Earl of Wessex

Godwin of Wessex , was one of the most powerful lords in England under the Danish king Cnut the Great and his successors. Cnut made him the first Earl of Wessex...

and his sons and the forfeiture of their earldoms, a man named Odda

Earl Odda

Odda of Deerhurst was an Anglo-Saxon nobleman active in the period from 1013 onwards. He became a leading magnate in 1051, following the exile of Godwin, Earl of Wessex and his sons and the confiscation of their property and earldoms, when King Edward the Confessor appointed Odda as earl over a...

was appointed earl over a portion of the lands thus vacated: this comprised Dorset

Dorset

Dorset , is a county in South West England on the English Channel coast. The county town is Dorchester which is situated in the south. The Hampshire towns of Bournemouth and Christchurch joined the county with the reorganisation of local government in 1974...

, Somerset

Somerset

The ceremonial and non-metropolitan county of Somerset in South West England borders Bristol and Gloucestershire to the north, Wiltshire to the east, Dorset to the south-east, and Devon to the south-west. It is partly bounded to the north and west by the Bristol Channel and the estuary of the...

, Devon

Devon

Devon is a large county in southwestern England. The county is sometimes referred to as Devonshire, although the term is rarely used inside the county itself as the county has never been officially "shired", it often indicates a traditional or historical context.The county shares borders with...

, and "Wealas". As Wealas is Saxon for foreigners, this could mean "West Wales"--that is, Cornwall—or it could mean that he was overlord of the Cornish foreigners in Devon or elsewhere.

Elizabethan historian William Camden

William Camden

William Camden was an English antiquarian, historian, topographer, and officer of arms. He wrote the first chorographical survey of the islands of Great Britain and Ireland and the first detailed historical account of the reign of Elizabeth I of England.- Early years :Camden was born in London...

, in the Cornish section of his Britannia, notes that

"As for the Earles, none of British bloud are mentioned but onely Candorus (called by others Cadocus), who is accounted by the late writers the last Earle of Cornwall of British race".

Norman conquest and after

Cornwall was included in the survey, initiated by William the Conqueror, the first Norman king of England, which became known as the Domesday BookDomesday Book

Domesday Book , now held at The National Archives, Kew, Richmond upon Thames in South West London, is the record of the great survey of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086...

, where it is included as being part of the Norman king's new domain. Cornwall was unusual as Domesday records no Saxon burh

Burh

A Burh is an Old English name for a fortified town or other defended site, sometimes centred upon a hill fort though always intended as a place of permanent settlement, its origin was in military defence; "it represented only a stage, though a vitally important one, in the evolution of the...

; a burh (borough) was the Saxons' centre of legal and administrative power. Moreover, nearly all land was held by one person, William's half-brother Robert of Mortain, who may have been the first Norman to bear the title Earl of Cornwall

Earl of Cornwall

The title of Earl of Cornwall was created several times in the Peerage of England before 1337, when it was superseded by the title Duke of Cornwall, which became attached to heirs-apparent to the throne.-Earl of Cornwall:...

. He held his Cornish lands not as a Tenant in Chief of the King, as was the case with other landowners, but as de-facto Viceroy.

F.M.Stenton tells us that the early Norman compilation known as 'The Laws of William the Conqueror' records all regions under West Saxon Law. These included Kent, Surrey, Sussex, Berkshire, Hanpshire, Wiltshire, Dorset, Somerset and Devon. Cornwall is not recorded as being under West Saxon, or English, law.

Ingulf was secretary to William the Conqueror and after 1066 was appointed Abbot of Croyland. When his church burned down, he established a fund raising committee to rebuild it. Ingulfs Chronicle tells us:

"Having obtained this indulgence, he now opened the foundation for the new church, and sent throughout the whole of England, and into lands adjoining and beyond the sea, letters testimonial. To the Northern parts and into Scotland he sent the brothers Fulk and Oger, and into Denmark and Norway the brothers Swetman and Wulsin; while to Wales, Cornwall and Ireland he sent the brothers Augustin and Osbert." See Ingulf Chronicle of the Abbey of Croyland with the continuation of Peter of Blois, trans Henry T. Riley (London: Henry G Bohn, 1854) pp. 229–227]

Henry of Huntingdon

Henry of Huntingdon

Henry of Huntingdon , the son of a canon in the diocese of Lincoln, was a 12th century English historian, the author of a history of England, Historia anglorum, "the most important Anglo-Norman historian to emerge from the secular clergy". He served as archdeacon of Huntingdon...

, writing about 1129, included Cornwall in his list of shires of England in his History of the English.

On the Mappa Mundi

Hereford Mappa Mundi

The Hereford Mappa Mundi is a mappa mundi, of a form deriving from the T and O pattern, dating to ca. 1300. It is currently on display in Hereford Cathedral in Hereford, England...

, circa 1300, now in Hereford Cathedral

Hereford Cathedral

The current Hereford Cathedral, located at Hereford in England, dates from 1079. Its most famous treasure is Mappa Mundi, a mediæval map of the world dating from the 13th century. The cathedral is a Grade I listed building.-Origins:...

, Cornwall (as "Cornubia") is one of the very few regions within Britain to be named individually. . The significance and relevance of this is unclear; the map belongs to a category of map known as Complex (Great) World Maps and its depiction, within such a world context, should be seen in parallel with related contemporaneous material.

The phrase "England and Cornwall" (Anglia et Cornubia) has been used on occasion in post-Norman official documents referring to the Duchy of Cornwall:

Extracted from a commission of the first Duke of Cornwall, 1351:

"25 Edw. III to "John Dabernoun, our Steward and Sheriff of Cornwall greeting. On account of certain escheats we command you that you inquire by all the means in your power how much land and rents, goods and chattels, whom and in whom, and of what value they which those persons of Cornwall and England have, whose names we send in a schedule enclosed......"

William Caxton

William Caxton

William Caxton was an English merchant, diplomat, writer and printer. As far as is known, he was the first English person to work as a printer and the first to introduce a printing press into England...

's 1480 Description of Britain debated whether or not Cornwall should be shown as separate to, or part of, England.

Tudor Period

The Italian Polydore VergilPolydore Vergil

Polydore Vergil was an Italian historian, otherwise known as PV Castellensis. He is better known as the contemporary historian during the early Tudor dynasty. He was hired by King Henry VIII of England, who wanted to distance himself from his father Henry VII as much as possible, to document...

in his Anglica Historia, published in 1535 wrote that four peoples speaking four different languages inhabited Britain:

"the whole Countrie of Britain ...is divided into iiii partes; whereof the one is inhabited of EnglishmenEnglish peopleThe English are a nation and ethnic group native to England, who speak English. The English identity is of early mediaeval origin, when they were known in Old English as the Anglecynn. England is now a country of the United Kingdom, and the majority of English people in England are British Citizens...

, the other of ScottesScottish peopleThe Scottish people , or Scots, are a nation and ethnic group native to Scotland. Historically they emerged from an amalgamation of the Picts and Gaels, incorporating neighbouring Britons to the south as well as invading Germanic peoples such as the Anglo-Saxons and the Norse.In modern use,...

, the third of WallshemenWelsh peopleThe Welsh people are an ethnic group and nation associated with Wales and the Welsh language.John Davies argues that the origin of the "Welsh nation" can be traced to the late 4th and early 5th centuries, following the Roman departure from Britain, although Brythonic Celtic languages seem to have...

, [and] the fowerthe of Cornishe peopleCornish peopleThe Cornish are a people associated with Cornwall, a county and Duchy in the south-west of the United Kingdom that is seen in some respects as distinct from England, having more in common with the other Celtic parts of the United Kingdom such as Wales, as well as with other Celtic nations in Europe...

, which all differ emonge them selves, either in tongue, ...in manners, or ells in lawes and ordinaunces."

During the Tudor period some travellers regarded the Cornish as a separate cultural group, from which some modern observers conclude that they were a separate ethnic group. For example Lodovico Falier, an Italian diplomat at the Court of Henry VIII said, "The language of the English, Welsh and Cornish men is so different that they do not understand each other." He went on to give the alleged 'national characteristics' of the three peoples, saying for example "the Cornishman is poor, rough and boorish".

Another example is Gaspard de Coligny Châtillon – the French Ambassador in London – who wrote saying that England was not a united whole as it "contains Wales and Cornwall, natural enemies of the rest of England, and speaking a different language." His use of the phrase "the rest of" implies that he believed Cornwall and Wales to be part of England in his sense of the word.

Some maps of the British Isles prior to the 17th century showed Cornwall (Cornubia / Cornwallia) as a territory on a par with Wales

Wales

Wales is a country that is part of the United Kingdom and the island of Great Britain, bordered by England to its east and the Atlantic Ocean and Irish Sea to its west. It has a population of three million, and a total area of 20,779 km²...

. However most post-date the incorporation of Wales as a principality of England. Examples include the maps of

Sebastian Munster

Sebastian Münster

Sebastian Münster , was a German cartographer, cosmographer, and a Hebrew scholar.- Life :Münster was born at Ingelheim near Mainz, the son of Andreas Munster. He completed his studies at the Eberhard-Karls-Universität Tübingen in 1518. His graduate adviser was Johannes Stöffler.He was appointed to...

(1515), Abraham Ortelius

Abraham Ortelius

thumb|250px|Abraham Ortelius by [[Peter Paul Rubens]]Abraham Ortelius thumb|250px|Abraham Ortelius by [[Peter Paul Rubens]]Abraham Ortelius (Abraham Ortels) thumb|250px|Abraham Ortelius by [[Peter Paul Rubens]]Abraham Ortelius (Abraham Ortels) (April 14, 1527 – June 28,exile in England to take...

, and Girolamo Ruscelli. Maps that depict Cornwall as a county of the Kingdom of England and Wales include

Gerardus Mercator

Gerardus Mercator

thumb|right|200px|Gerardus MercatorGerardus Mercator was a cartographer, born in Rupelmonde in the Hapsburg County of Flanders, part of the Holy Roman Empire. He is remembered for the Mercator projection world map, which is named after him...

's 1564 atlas of Europe, and Christopher Saxton

Christopher Saxton

Christopher Saxton was an English cartographer, probably born in the parish of Dewsbury, in the West Riding of Yorkshire, England around 1540....

's 1579 map authorised by Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I was queen regnant of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death. Sometimes called The Virgin Queen, Gloriana, or Good Queen Bess, Elizabeth was the fifth and last monarch of the Tudor dynasty...

.

A miniature "epitome" of Ortelius' map of England & Wales, published in 1595, names Cornwall; the same map displays Kent in an equivalent manner. Maps of Britain which display Cornwall usually in their legends do not refer to Cornwall, e.g. Lily 1548.

17th & 18th Centuries

Recognition that several peoples lived within Britain and Ireland continues through the 17th century. For example after the death of Elizabeth I in 1603, the Venetian ambassador wrote that the late queen had ruled over five different 'peoples': "English, Welsh, Cornish, Scottish ...and Irish".Writing in 1616, diplomat Arthur Hopton stated:

"England is ...divided into 3 great Provinces, or Countries ...every of them speaking a several and different language, as English, Welsh and Cornish."

Wales was effectively annexed to the Kingdom of England

Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England was, from 927 to 1707, a sovereign state to the northwest of continental Europe. At its height, the Kingdom of England spanned the southern two-thirds of the island of Great Britain and several smaller outlying islands; what today comprises the legal jurisdiction of England...

in the 16th century by the Laws in Wales Acts 1535–1542, but references to 'England' in law were not presumed to include Wales (or indeed Berwick-upon-Tweed

Berwick-upon-Tweed

Berwick-upon-Tweed or simply Berwick is a town in the county of Northumberland and is the northernmost town in England, on the east coast at the mouth of the River Tweed. It is situated 2.5 miles south of the Scottish border....

) until the Wales and Berwick Act 1746

Wales and Berwick Act 1746

The Wales and Berwick Act 1746 was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain which created a statutory definition of "England" as including England, Wales and Berwick-upon-Tweed. This definition applied to all acts passed before and after the Act's coming into force, unless a given Act provided an...

. By this time the use of "England and Cornwall" (Anglia et Cornubia) had ceased.

Because of the tendency of historians to trust the work of their predecessors, Geoffrey of Monmouth's semi-fictional 12th-Century Historia Regum Britanniae remained influential for centuries, often used by writers who were unaware that his work was the source. For example, in 1769 the antiquary William Borlase

William Borlase

William Borlase , Cornish antiquary, geologist and naturalist, was born at Pendeen in Cornwall, of an ancient family . From 1722 he was Rector of Ludgvan and died there in 1772.-Life and works:...

wrote the following, which is actually a summary of a passage from Geoffrey [Book iii:1]:

"Of this time we are to understand what Edward I. says (Sheringham. [De Anglorum Gentis Origine] p. 129.) that Britain, Wales, and Cornwall, were the portion of BelinusBelinusBelinus the Great was a legendary king of the Britons, as recounted by Geoffrey of Monmouth. He was the son of Dunvallo Molmutius and brother of Brennius. He was probably named after the ancient god Belenus.- Earning the crown :...

, elder son of Dunwallo, and that that part of the Island, afterwards called England, was divided in three shares, viz. Britain, which reached from the TweedRiver TweedThe River Tweed, or Tweed Water, is long and flows primarily through the Borders region of Great Britain. It rises on Tweedsmuir at Tweed's Well near where the Clyde, draining northwest, and the Annan draining south also rise. "Annan, Tweed and Clyde rise oot the ae hillside" as the Border saying...

, Westward, as far as the river ExRiver ExeThe River Exe in England rises near the village of Simonsbath, on Exmoor in Somerset, near the Bristol Channel coast, but flows more or less directly due south, so that most of its length lies in Devon. It reaches the sea at a substantial ria, the Exe Estuary, on the south coast of Devon...

; Wales inclosed by the rivers SevernRiver SevernThe River Severn is the longest river in Great Britain, at about , but the second longest on the British Isles, behind the River Shannon. It rises at an altitude of on Plynlimon, Ceredigion near Llanidloes, Powys, in the Cambrian Mountains of mid Wales...

, and DeeRiver Dee, WalesThe River Dee is a long river in the United Kingdom. It travels through Wales and England and also forms part of the border between the two countries....

; and Cornwall from the river Ex to the Land's-EndLand's EndLand's End is a headland and small settlement in west Cornwall, England, within the United Kingdom. It is located on the Penwith peninsula approximately eight miles west-southwest of Penzance....

".

Another 18th century writer, Richard Gough

Richard Gough (antiquarian)

Richard Gough was an English antiquarian.He was born in London, where his father was a wealthy M.P. and director of the British East India Company. In 1751 he entered Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, where he began his work on British topography, published in 1768...

, concentrated on a contemporary viewpoint, noting that "Cornwall seems to be another Kingdom", in his "Camden's Britannia", 2nd ed.(4 vols; London, 1806).

During the eighteenth century, Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson , often referred to as Dr. Johnson, was an English author who made lasting contributions to English literature as a poet, essayist, moralist, literary critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer...

created an ironic Cornish Declaration of Independence

Declaration of independence

A declaration of independence is an assertion of the independence of an aspiring state or states. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the territory of another nation or failed nation, or are breakaway territories from within the larger state...

that he used in his essay Taxation no Tyranny His irony starts:

- "As political diseases are naturally contagious, let it be supposed, for a moment, that Cornwall, seized with the Philadelphian phrensy, may resolve to separate itself from the general system of the English constitution, and judge of its own rights in its own parliament. A congress might then meet at Truro, and address the other counties in a style not unlike the language of the American patriots ... We are the acknowledged descendants of the earliest inhabitants of Britain, of men, who, before the time of history, took possession of the island desolate and waste, and, therefore, open to the first occupants. Of this descent, our language is a sufficient proof, which, not quite a century ago, was different from yours."

19th century

Popular Cornish sentiment during the 19th century appears to have been still strong. For example, Hamilton Jenkin records the reaction of a school pupil who was asked to describe Cornwall's situation replied: "he's kidged to a furren country from the top hand" – i.e. "it's joined to a foreign country from the upper part". This reply was "heard by the whole school with much approval, including old Peggy (the school-dame) herself."The famous crime writer Wilkie Collins

Wilkie Collins

William Wilkie Collins was an English novelist, playwright, and author of short stories. He was very popular during the Victorian era and wrote 30 novels, more than 60 short stories, 14 plays, and over 100 non-fiction pieces...

described Cornwall as:

- "a county where, it must be remembered, a stranger is doubly a stranger, in relation to his provincial sympathies; where the national feeling is almost entirely merged into the local feeling; where a man speaks of himself as Cornish in much the same way that a Welshman speaks of himself as Welsh."

Chambers' Journal in 1861 described Cornwall as "one of the most un-English of English counties." – a sentiment echoed by the naturalist W.H. Hudson who also referred to it as "un-English" and said there were:

- "[few] Englishmen in Cornwall who do not experience that antipathy or sense of separation in mind from the people they live with, and are not looked upon as foreigners"

Until the 'Tin Duties Abolition Act 1838', the Cornish miner was charged twice the level of taxation compared to the English miner. The English practice of charging 'foreigners' double taxation had existed in Cornwall for over 600 years prior to the 1836 Act and was first referenced in William de Wrotham's letter of 1198AD, published in G.R.Lewis, The Stannaries [1908]. The campaigning West Briton Newspaper called the racially applied tax "oppresive and vexatious" [19th Jan 1838]. In 1856 the Westminster Parliament was still able to refer to the Cornish as aboriginals.[Foreshore Case papers, Page 11, Section 25]

Cornish "shires"

Hundreds of Cornwall

Cornwall was from Anglo-Saxon times until the 19th century divided into hundreds, some with the suffix shire as in Pydarshire, East and West Wivelshire and Powdershire which were first recorded as names between 1184-1187. In the Cornish language the word for "hundred" is keverang and is the...

", which often bore the name of "shire" in English. In Cornish, they were called kevrangow (sing. kevrang).

Although the name "shire", today implies some kind of county status, hundreds in some English counties often bore the suffix 'shire' as well (e.g. Salfordshire

Salford (hundred)

The hundred of Salford was an ancient division of the historic county of Lancashire, in Northern England. It was sometimes known as Salfordshire, the name alluding to its judicial centre being the township of Salford...

), but where English shires were split into hundreds each having their own constable, Cornish hundreds had constables at parish level.

The Kevrangow were not however, English hundreds: Triggshire came from Tricori 'three warbands', suggesting a military muster area capable of supporting three hundred fighting men. However it must be said that this is an inference from name alone, and does not constitute historical evidence of any fighting force raised by a Cornish hundred.

The Cornish kevrang replicated England's shire system on a smaller scale. Although by the 15th century the shires of Cornwall had become hundreds, the administrative differences remained in place long after.

Current administrative status

Regardless of the question of whether Cornwall constitutes one of the historic counties of EnglandHistoric counties of England

The historic counties of England are subdivisions of England established for administration by the Normans and in most cases based on earlier Anglo-Saxon kingdoms and shires...

, an administrative county

Administrative counties of England

Administrative counties were a level of subnational division of England used for the purposes of local government from 1889 to 1974. They were created by the Local Government Act 1888 as the areas for which county councils were elected. Some large counties were divided into several administrative...

of Cornwall was set up by the Local Government Act 1888

Local Government Act 1888

The Local Government Act 1888 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, which established county councils and county borough councils in England and Wales...

, which came into effect on 1 April 1889. This was replaced by a non-metropolitan county of Cornwall in 1974 by the Local Government Act 1972

Local Government Act 1972

The Local Government Act 1972 is an Act of Parliament in the United Kingdom that reformed local government in England and Wales on 1 April 1974....

, which includes it under the heading of "England". The Duke of Cornwall is still granted a number of unique statutory "privileges, exemptions, powers, rights and authority" in the Cornwall (Tamar Bridge) Act 1998, s.41, and other Acts. In addition the Treasury Solicitors agency for bona vacantia Division considers The Duchy of Cornwall to comprise the County of Cornwall.

The argument for non-English constitutional status

Norsemen

Norsemen is used to refer to the group of people as a whole who spoke what is now called the Old Norse language belonging to the North Germanic branch of Indo-European languages, especially Norwegian, Icelandic, Faroese, Swedish and Danish in their earlier forms.The meaning of Norseman was "people...

. Sweyn Forkbeard, the first Danish King of England, died a few weeks after his English opponent Ethelred the Unready

Ethelred the Unready

Æthelred the Unready, or Æthelred II , was king of England . He was son of King Edgar and Queen Ælfthryth. Æthelred was only about 10 when his half-brother Edward was murdered...

had fled, so it is probable that he never properly took control of Cornwall. His son Canute never properly conquered or controlled Scotland or Wales, but he appears to have had some authority in Cornwall, for in 1027 his counsellor Lyfing

Lyfing

"Lyfing" an Anglo-Saxon given name.Notable people bearing this name include:* Lyfing, Archbishop of Canterbury advisor to King Ethelred the Unready* Lyfing of Winchester advisor to King Canute the Dane...

(already bishop of Crediton) was appointed as bishop of Cornwall

Bishop of Cornwall

The Bishop of Cornwall was an episcopal title which was used by Anglo Saxons between the 9th and 11th centuries. The bishop's seat was located at the village of St Germans, Cornwall. Later bishops of Cornwall were sometimes referred to as the bishops of St Germans...

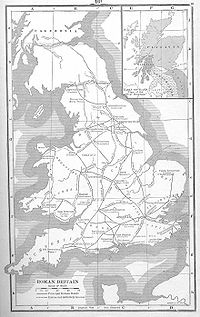

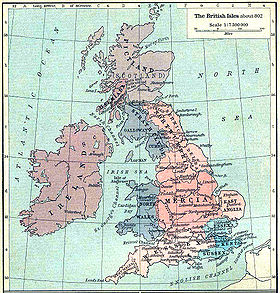

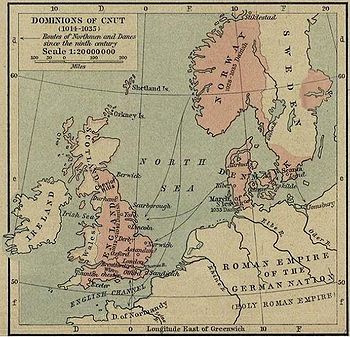

(St Germans), beginning the merger which would later form the See of Exeter. The map pictured, by William R. Shepherd (1926), shows Cornwall as not part of Canute's realm, but this approach is not followed by more recent scholarship, such as David Hill's An Atlas of Anglo-Saxon England(1981). Ultimately, the Danes' control of Wessex was lost in 1042 with the death of both of Canute's sons (Edward the Confessor retook Wessex for the Anglo-Saxons) but nevertheless the historical possibility that Cornwall was not a fully subdued part of the English kingdom under the Danes is critical and is an argument that may be advanced for the idea that both the Anglo-Saxon and Danish kings had limitations on their political status in Cornwall in the 10th and 11th centuries.

When the Domesday Survey

Domesday Book

Domesday Book , now held at The National Archives, Kew, Richmond upon Thames in South West London, is the record of the great survey of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086...

was initiated, by William

William I of England

William I , also known as William the Conqueror , was the first Norman King of England from Christmas 1066 until his death. He was also Duke of Normandy from 3 July 1035 until his death, under the name William II...

, in 1086, men were sent to "each shire" in his new kingdom. This has to be seen within the context of matters of land, property and taxation and not as a means of misrepresenting what is understood, at that time, as a county. A shire

Shire

A shire is a traditional term for a division of land, found in the United Kingdom and in Australia. In parts of Australia, a shire is an administrative unit, but it is not synonymous with "county" there, which is a land registration unit. Individually, or as a suffix in Scotland and in the far...

, coming under the jurisdiction of the sheriff

Sheriff

A sheriff is in principle a legal official with responsibility for a county. In practice, the specific combination of legal, political, and ceremonial duties of a sheriff varies greatly from country to country....

, is known alternatively as sheriffdom

Sheriffdom

A sheriffdom is a judicial district in Scotland.Since 1 January 1975 there have been six sheriffdoms. Previously sheriffdoms were composed of groupings of counties...

, shrievalty, or vicecomitatus and equates to the modern meaning of the word county

County

A county is a jurisdiction of local government in certain modern nations. Historically in mainland Europe, the original French term, comté, and its equivalents in other languages denoted a jurisdiction under the sovereignty of a count A county is a jurisdiction of local government in certain...

.

On 12 Feb 1857, during the pivotal Cornish Foreshore dispute

Cornish Foreshore Case

The Cornish Foreshore Case was an arbitration case held between 1854 and 1858 to resolve a formal dispute between the British Crown and the Duchy of Cornwall over the ownership of the foreshore of the county of Cornwall in the southwest of England...

, the Attorney General to the Duchy of Cornwall stated that whether it was held by a viceroy, by the Crown or granted to family or favourites, the Earldom of Cornwall (Comitatus Cornubiǽ) included all territorial revenues, rights and property which were held "as of the Honor". He then outlined how, when entrusted to the Crown, Cornwall was held not jure coronǽ but jure Comitatus – or jure Ducatus, when augmented to a Duchy – as of the Honor in manu Regis existente. [See foreshore dispute papers]

In 1328 the Earldom of Cornwall, extinct since the disgrace and execution of Piers Gaveston in 1312, was recreated and awarded to John

John of Eltham, Earl of Cornwall

John of Eltham, 1st Earl of Cornwall was the second son of Edward II of England and Isabella of France. He was heir to the English throne from the date of the abdication of his father to the birth of his nephew Edward of Woodstock .-Life:John was born in 1316 at Eltham Palace, Kent...

, younger brother of King Edward III. In September 1336, shortly before he was due to marry, John died, so his heir was his brother the King, who at the beginning of March the following year proposed to Parliament that the Earldom should become a Royal Duchy, to, in the words of the Royal Declaration that preceded the Charter, "restore notable places of the realm to their pristine honours". This was agreed, and put into law by a charter dated the 17th of March 1337. A second charter, immediately following the "Great Charter," attempted to clarify the Duke's rights specifically within the County of Cornwall. In addition to extensive estates (among them a number of entire towns and villages) this included the governance of the whole of Cornwall.

When the first Duke of Cornwall came of age in 1351, one of his first official acts was to carry out his own form of Domesday survey (Commission 25 Edward III). This has already been referred to above and confirms that Cornwall was not in England, when the Duke refers to his tenants and property as being in Cornwall and England [Records of the Black Prince]. This implies that Cornwall was at that time a constitutionally non-English territory, a province of the Britons.

To assert that this is a mediaeval feudal relic with no relevance to the present day constitutional situation, would not be historically or legally supportable.

It has been claimed that sometime between 1858 and prior to the UK Parliament passing the Local Government Act in 1888, several Acts of Parliament were made to disappear. Allegedly, the pre-1st charter Letters Patent and the last two duchy charters were shredded, and the English translation of the remaining 1st duchy charter was altered from the original translation (these actions being kept secret, and the people of Cornwall never consulted). The 1st duchy charter (Constitutional Law 10) is still on the statute books but is marked by government as being ‘revised’ again in 1978. The alleged co-conspirators in the coup d’état were and are the Government of the Duchy of Cornwall and the Government of the United Kingdom.

However any allegation of this kind needs to take account of the publication together in book form of the collection of English Acts of Parliament in 1811.

The Council for Racial Equality in Cornwall website states the following:- Cornwall retains a unique and distinct constitutional relationship with the Crown, based on the Duchy of Cornwall and the Stannaries. For other purposes it is recognised as a Celtic region or nation and enjoys its own national flag.

On 14 July 2009, Dan Rogerson

Dan Rogerson

Daniel John Rogerson is a Cornish Liberal Democrat politician. He has been the Member of Parliament for North Cornwall since the 2005 General election.-Early life:...

MP, of the Liberal Democrats

Liberal Democrats

The Liberal Democrats are a social liberal political party in the United Kingdom which supports constitutional and electoral reform, progressive taxation, wealth taxation, human rights laws, cultural liberalism, banking reform and civil liberties .The party was formed in 1988 by a merger of the...

, presented a Cornish 'breakaway' bill to the Parliament in Westminster – 'The Government of Cornwall Bill'. The bill proposes a devolved Assembly for Cornwall, similar to the Welsh and Scottish setup. The bill states that Cornwall should re-assert its rightful place within the United Kingdom. "Cornwall is a unique part of the country, and this should be reflected in the way that it is governed. The Bill would provide Cornwall for greater responsibility in areas such as agriculture, heritage, education, housing and economic sustainability. There is a political and social will for Cornwall to be recognised as its own nation. Constitutionally, Cornwall has the right to a level of self-Government, as demonstrated by the Cornish Foreshore Case

Cornish Foreshore Case

The Cornish Foreshore Case was an arbitration case held between 1854 and 1858 to resolve a formal dispute between the British Crown and the Duchy of Cornwall over the ownership of the foreshore of the county of Cornwall in the southwest of England...

in 1858 which confirmed that Cornwall is legally a Duchy which is extraterritorial to England. If the Government is going to recognise the right of Scotland and Wales to greater self-determination because of their unique cultural and political positions, then they should recognise the same right of Cornwall."

The argument for English county status

Yorkshire

Yorkshire is a historic county of northern England and the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its great size in comparison to other English counties, functions have been increasingly undertaken over time by its subdivisions, which have also been subject to periodic reform...

, Kent

Kent

Kent is a county in southeast England, and is one of the home counties. It borders East Sussex, Surrey and Greater London and has a defined boundary with Essex in the middle of the Thames Estuary. The ceremonial county boundaries of Kent include the shire county of Kent and the unitary borough of...

, and Cheshire

Cheshire

Cheshire is a ceremonial county in North West England. Cheshire's county town is the city of Chester, although its largest town is Warrington. Other major towns include Widnes, Congleton, Crewe, Ellesmere Port, Runcorn, Macclesfield, Winsford, Northwich, and Wilmslow...

(for example) also have local customs and identities that do not seem to undermine their essential Englishness. The legal claims concerning the Duchy, they argue, are without merit except as relics of mediaeval feudalism, and they contend that Stannary law applied not to Cornwall as a 'nation', but merely to the guild of tin miners. Rather, they argue that Cornwall has been not only in English possession, but part of England itself, either since Athelstan conquered it in 936, since the administrative centralisation of the Tudor dynasty

Tudor dynasty

The Tudor dynasty or House of Tudor was a European royal house of Welsh origin that ruled the Kingdom of England and its realms, including the Lordship of Ireland, later the Kingdom of Ireland, from 1485 until 1603. Its first monarch was Henry Tudor, a descendant through his mother of a legitimised...

, or since the creation of Cornwall County Council

Cornwall County Council

Cornwall Council is the unitary authority for Cornwall, in England, United Kingdom. The council, and its predecessor Cornwall County Council, has a tradition of large groups of independents, having been controlled by independents in the 1970s and 1980s...

in 1888. Finally, they agree with representatives of the Duchy

Duchy of Cornwall

The Duchy of Cornwall is one of two royal duchies in England, the other being the Duchy of Lancaster. The eldest son of the reigning British monarch inherits the duchy and title of Duke of Cornwall at the time of his birth, or of his parent's succession to the throne. If the monarch has no son, the...

itself that the Duchy is, in essence, a real estate company that serves to raise income for the Prince of Wales. They compare the situation of the Duchy of Cornwall with that of the Duchy of Lancaster, which has similar rights in Lancashire

Lancashire

Lancashire is a non-metropolitan county of historic origin in the North West of England. It takes its name from the city of Lancaster, and is sometimes known as the County of Lancaster. Although Lancaster is still considered to be the county town, Lancashire County Council is based in Preston...

, which is indisputably part of England. The proponents of such perspectives include not only Unionists, but most branches and agencies of government.

Below are some indications that would tend to support the assertion that for more than the last thousand years has been governed as a part of England and in a way indistinguishable from other parts of England:

- It has been argued that Cornwall was absorbed into England rather than conquered.

- Several English charters dating from before 1066 show the king of England exercising effective power in Cornwall as in any other part of their kingdom. For example, in 960 King Eadgar gave land in "Tiwaernhel" to one of his thanes.

- From the mid-ninth century the Cornish Church acknowledged the jurisdiction of the Archbishop of CanterburyArchbishop of CanterburyThe Archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and principal leader of the Church of England, the symbolic head of the worldwide Anglican Communion, and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. In his role as head of the Anglican Communion, the archbishop leads the third largest group...

, and in the 10th century the English king AthelstanAthelstan of EnglandAthelstan , called the Glorious, was the King of England from 924 or 925 to 939. He was the son of King Edward the Elder, grandson of Alfred the Great and nephew of Æthelflæd of Mercia...

created a diocese of Cornwall centred on St Germans. In 1050, King Eadward subsumed the diocese of Cornwall under that of ExeterExeterExeter is a historic city in Devon, England. It lies within the ceremonial county of Devon, of which it is the county town as well as the home of Devon County Council. Currently the administrative area has the status of a non-metropolitan district, and is therefore under the administration of the...

.

- In 1051, as noted above, Cornwall was granted with Devon, Somerset and Dorset to Earl OddaEarl OddaOdda of Deerhurst was an Anglo-Saxon nobleman active in the period from 1013 onwards. He became a leading magnate in 1051, following the exile of Godwin, Earl of Wessex and his sons and the confiscation of their property and earldoms, when King Edward the Confessor appointed Odda as earl over a...

, indicating that Cornwall had by then been integrated into the normal English system of local government.

- The Domesday BookDomesday BookDomesday Book , now held at The National Archives, Kew, Richmond upon Thames in South West London, is the record of the great survey of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086...

, compiled in 1086, lists all territory in Great Britain under Norman control at that time, mostly listing individual manors grouped by county. Scotland is excluded, and so are nominally English areas then under Scottish control, such as Northumberland and most of Cumberland. Wales is also excluded, except for areas the Normans had managed to capture, such as Flintshire. Cornwall is not excluded, and, unlike, for example, the later LancashireLancashireLancashire is a non-metropolitan county of historic origin in the North West of England. It takes its name from the city of Lancaster, and is sometimes known as the County of Lancaster. Although Lancaster is still considered to be the county town, Lancashire County Council is based in Preston...

(parts of which were listed with CheshireCheshireCheshire is a ceremonial county in North West England. Cheshire's county town is the city of Chester, although its largest town is Warrington. Other major towns include Widnes, Congleton, Crewe, Ellesmere Port, Runcorn, Macclesfield, Winsford, Northwich, and Wilmslow...

, other parts with YorkshireYorkshireYorkshire is a historic county of northern England and the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its great size in comparison to other English counties, functions have been increasingly undertaken over time by its subdivisions, which have also been subject to periodic reform...

) is given a listing in the normal Domesday county-based style.

- The records of the medieval eyres, the court sessions of the king's itinerant judges. Maitland FW (1888) Select pleas of the crown prints examples from Cornwall. The eyre records show Cornwall and England with common judicial arrangements from the police duties of tithings at the lowest level of administration to the highest itinerant courts.

- Some say that before the creation of the Duchy, the assets of the Earl of Cornwall (including privileges such as bailiff rights, stannaries and wrecks) were subject to Crown escheatEscheatEscheat is a common law doctrine which transfers the property of a person who dies without heirs to the crown or state. It serves to ensure that property is not left in limbo without recognised ownership...

, as in the case of Edmund, 2nd Earl of CornwallEdmund, 2nd Earl of CornwallEdmund of Cornwall of Almain was the 2nd Earl of Cornwall of the 7th creation.-Early life:Edmund was born at Berkhamsted Castle on 26 December 1249, the second and only surviving son of Richard, 1st Earl of Cornwall and his wife Sanchia of Provence, daughter of Ramon Berenguer, Count of Provence,...

(died 1300) However, records contained within the foreshore dispute papers show that entry into Cornwall for the Kings Escheator was often barred on grounds that the King's writ does not run in Cornwall. For example, records of the Launceston Eyre of 1284 show Edmund successfully resisting the King's attempted assertion of escheat rights over Cornwall. Edmund's advocate opened his plea with the words, "my liege lord hols Corrnwall above the Lord King in Chief....so the Escheator of the Lord the King shall not intermeddle in anything belonging to the Sheriff of Cornwall". That same year Edmund is confirmed as having 'right of wreck' in Cornwall [Coram Regis Rolls 14 Edw.1 Easter No.99, M29d – Foreshore dispute papers].

- The Patent RollsPatent RollsThe Patent Rolls are primary sources for English history, a record of the King of England's correspondence, starting in 1202....

which inter alia record the King and his council governing Cornwall after the creation of the Dukedom in 1337. Examples are the inquiries into the use of the English-controlled port of Calais in 1474 (when officials of all counties, including Cornwall, were required to submit returns), the King granting licences to trade to people in Cornwall in 1364, the Duke of Cornwall complaining in 1371 to the King's CouncilPrivy councilA privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a nation, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the monarch's closest advisors to give confidential advice on...

about offences by some local men in Cornwall, and in 1380 the King's Council ordering the Sheriff of Cornwall to arrest and imprison an offender.

- The 1337 charters describe Cornwall as a county, using the same word (comitatus) as that used to describe other counties such as Devon and Surrey.

- Cornwall sent members to the Parliament of EnglandParliament of EnglandThe Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England. In 1066, William of Normandy introduced a feudal system, by which he sought the advice of a council of tenants-in-chief and ecclesiastics before making laws...

from the late thirteenth century when that parliament originated.

- Some national policies in the Middle Ages, such as the taxation of boroughs, or the setting of prices for wool, were applied on a county-by-county basis- including Cornwall.

- Medieval taxes such as the Papal 1291 taxation, the 1377 poll tax and the tax for defence against "the cruel malice of the Scots" in 1496-7 include Cornwall among the other English counties.

- The subsidies/taxes and musters of the Tudor period.]

- The grants of fairs and markets in Cornwall by the king; for example, Penzance in 1406.

Modern day governmental position

Cornwall is currently represented in the European Parliament within the South West EnglandSouth West England (European Parliament constituency)

South West England is a constituency of the European Parliament. For 2009 it elects 6 MEPs using the d'Hondt method of party-list proportional representation, reduced from 7 in 2004.-Boundaries:...

European Parliament constituency

European Parliament constituency

Members of the European Parliament are elected by the population of the member states of the European Union , divided into constituencies....

, which also takes in Gibraltar

Gibraltar

Gibraltar is a British overseas territory located on the southern end of the Iberian Peninsula at the entrance of the Mediterranean. A peninsula with an area of , it has a northern border with Andalusia, Spain. The Rock of Gibraltar is the major landmark of the region...

.

The (previous) government has said it will not be undertaking a review of the constitutional status of Cornwall and will not be changing the present status of the county; the justice minister, Michael Wills, replying to a question from Andrew George MP, stated that "Cornwall is an administrative county of England, electing MPs to the UK Parliament, and is subject to UK legislation. It has always been an integral part of the Union. The Government have no plans to alter the constitutional status of Cornwall."

The Duchy of Cornwall

High Sheriff

A high sheriff is, or was, a law enforcement officer in the United Kingdom, Canada and the United States.In England and Wales, the office is unpaid and partly ceremonial, appointed by the Crown through a warrant from the Privy Council. In Cornwall, the High Sheriff is appointed by the Duke of...

, bona vacantia

Bona vacantia

Bona vacantia is a legal concept associated with property that has no owner. It exists in various jurisdictions, with consequently varying application, but with origins mostly in English law.-Canada:...

, treasure trove

Treasure trove

A treasure trove may broadly be defined as an amount of money or coin, gold, silver, plate, or bullion found hidden underground or in places such as cellars or attics, where the treasure seems old enough for it to be presumed that the true owner is dead and the heirs undiscoverable...

, a separate exchequer, and such forth. Most of these rights are still exercised by the Duchy. The Kilbrandon Report

Royal Commission on the Constitution (United Kingdom)

The Royal Commission on the Constitution, also referred to as the Kilbrandon Commission or Kilbrandon Report, was a long-running royal commission set up by Harold Wilson's Labour government to examine the structures of the constitution of the United Kingdom and the British Islands and the...

(1969–1971) into the British constitution

Constitution

A constitution is a set of fundamental principles or established precedents according to which a state or other organization is governed. These rules together make up, i.e. constitute, what the entity is...

recommends that, when referring to Cornwall

Cornwall

Cornwall is a unitary authority and ceremonial county of England, within the United Kingdom. It is bordered to the north and west by the Celtic Sea, to the south by the English Channel, and to the east by the county of Devon, over the River Tamar. Cornwall has a population of , and covers an area of...

, official sources should cite the Duchy not the County. This was suggested in recognition of its constitutional position.

In 1780 Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke PC was an Irish statesman, author, orator, political theorist and philosopher who, after moving to England, served for many years in the House of Commons of Great Britain as a member of the Whig party....

sought to curtail further the power of the Crown by removing the various principalities which existed.

… the five several distinct principalities besides the supreme …. If you travel beyond Mount Edgcumbe, you find him [the king] in his incognito, and he is duke of Cornwall …. Thus every one of these principalities has the apparatus of a kingdom …. Cornwall is the best of them….

Some Cornish people

Cornish people

The Cornish are a people associated with Cornwall, a county and Duchy in the south-west of the United Kingdom that is seen in some respects as distinct from England, having more in common with the other Celtic parts of the United Kingdom such as Wales, as well as with other Celtic nations in Europe...

, including Cornish Solidarity

Cornish Solidarity

Cornish Solidarity is a Cornish organisation founded in February 1998. It was founded by the then President of Redruth and District Chamber of Commerce, Mr Greg Woods, who having been disgusted at the press being notified of the demise of South Crofty Mine before the staff and workers of the mine,...

and the group claiming to be the Revived Cornish Stannary Parliament

Revived Cornish Stannary Parliament

The Revived Cornish Stannary Parliament , is a pressure group which claims to be a revival of the historic Cornish Stannary Parliament last held in 1753...

, argue that Cornwall has a de jure

De jure

De jure is an expression that means "concerning law", as contrasted with de facto, which means "concerning fact".De jure = 'Legally', De facto = 'In fact'....

status apart as a sovereign Duchy extraterritorial to England. A commonly cited basis for this argument is a case of arbitration between the Crown and the Duchy of Cornwall (1856–1857) in which the Officers of the Duchy successfully argued that the Duchy enjoyed many of the rights and prerogatives of a County palatine

County palatine

A county palatine or palatinate is an area ruled by an hereditary nobleman possessing special authority and autonomy from the rest of a kingdom or empire. The name derives from the Latin adjective palatinus, "relating to the palace", from the noun palatium, "palace"...

and that although the duke was not granted Royal Jurisdiction

Jurisdiction

Jurisdiction is the practical authority granted to a formally constituted legal body or to a political leader to deal with and make pronouncements on legal matters and, by implication, to administer justice within a defined area of responsibility...

, was considered to be quasi-sovereign within his Duchy of Cornwall.

The arbitration, as instructed by the Crown, was based on legal argument and documentation, led to the Cornwall Submarine Mines Act of 1858. The Officers of the Duchy, based on its researches, made this submission:

- That Cornwall, like Wales, was at the time of the Conquest, and was subsequently treated in many respects as distinct from England.

- That it was held by the Earls of Cornwall with the rights and prerogative of a County Palatine, as far as regarded the Seignory or territorial dominion.

- That the Dukes of Cornwall have from the creation of the Duchy enjoyed the rights and prerogatives of a County Palatine, as far as regarded seignory or territorial dominion, and that to a great extent by Earls.

- That when the Earldom was augmented into a Duchy, the circumstances attending to its creation, as well as the language of the Duchy Charter, not only support and confirm natural presumption, that the new and higher title was to be accompanied with at least as great dignity, power, and prerogative as the Earls enjoyed, but also afforded evidence that the Duchy was to be invested with still more extensive rights and privileges.

- The Duchy Charters have always been construed and treated, not merely by the Courts of Judicature, but also by the Legislature of the Country, as having vested in the Dukes of Cornwall the whole territorial interest and dominion of the Crown in and over the entire County of Cornwall.

However, the term 'county palatine

County palatine

A county palatine or palatinate is an area ruled by an hereditary nobleman possessing special authority and autonomy from the rest of a kingdom or empire. The name derives from the Latin adjective palatinus, "relating to the palace", from the noun palatium, "palace"...

' appears not to have been used historically of Cornwall, and the duchy did not have as much autonomy as the County Palatine of Durham

County Durham

County Durham is a ceremonial county and unitary district in north east England. The county town is Durham. The largest settlement in the ceremonial county is the town of Darlington...

, which was ruled by the Prince-Bishop of Durham. However, whilst not specifically called a county palatine, the Officers of the Duchy made the observation (Duchy Preliminary Statement – Cornish Foreshore Dispute 1856):

"The Dukes also had their own escheators in Cornwall, and it is deserving of notice that in the saving clause of the Act of Escheators, 1 Henry VIII., c. 8, s. 5 (as is the case in numerous other acts of Parliament), the Duchy of Cornwall is classed with counties undoubtedly palatinate."

The Stannaries and their revival

Since 1974, a group has claimed to be a revived Cornish StannaryStannary Courts and Parliaments

The Stannary Parliaments and Stannary Courts were legislative and legal institutions in Cornwall and in Devon , England. The Stannary Courts administered equity for the region's tin-miners and tin mining interests, and they were also courts of record for the towns dependent on the mines...

Parliament and have the ancient right of Cornish tin-miners' assemblies to veto legislation from Westminster

Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body in the United Kingdom, British Crown dependencies and British overseas territories, located in London...

. In 1977 the Plaid Cymru

Plaid Cymru

' is a political party in Wales. It advocates the establishment of an independent Welsh state within the European Union. was formed in 1925 and won its first seat in 1966...

MP Dafydd Wigley

Dafydd Wigley

Dafydd Wigley, Baron Wigley is a Welsh politician. He served as Plaid Cymru Member of Parliament for Caernarfon from 1974 until 2001 and as an Assembly Member for Caernarfon from 1999 until 2003. He was leader of the Plaid Cymru party from 1991 to 2000...

in Parliament asked the Attorney General for England and Wales if he would provide the date upon which enactments of the Charter of Pardon of 1508 were rescinded. The reply, received on 14 May 1977 and now held at the National Library of Wales

National Library of Wales

The National Library of Wales , Aberystwyth, is the national legal deposit library of Wales; one of the Welsh Government sponsored bodies.Welsh is its main medium of communication...

, stated that a Stannator's right to veto Westminster legislation had never been formally withdrawn.

Moves for a change of constitutional status