Percy Cradock

Encyclopedia

Sir Percy Cradock, GCMG was a British

diplomat

, civil servant and sinologist who served as British Ambassador to the People's Republic of China from 1978 to 1983, playing a significant role in the Sino-British negotiations which led up to the signing of the Sino-British Joint Declaration

in 1984.

Joining the Foreign Office in 1954, Cradock served primarily in Asia

and was posted to the British charge d'affaires office in Peking (now Beijing) at the outset of the Cultural Revolution

in 1966. He, along with other British subjects, was manhandled by the Red Guards

and the mobs when the office was set on fire on 22 August 1967. After the rioting, Cradock served as charge d'affaires

in Peking from 1968 to 1969, and later succeeded Sir Edward Youde

as British Ambassador to the People's Republic of China in 1978. His ambassadorship witnessed the start of the Sino-British negotiations in 1982, which subsequently resulted in the Joint Declaration in 1984, an agreement deciding the future of the sovereignty

of Hong Kong

after 1997. However, the move of Cradock, who was the British chief negotiator in the negotiations, to compromise with the Chinese authority was regarded as a major retreat by the general media in Hong Kong and the United Kingdom

, and was heavily criticized at that time as betraying the people of Hong Kong.

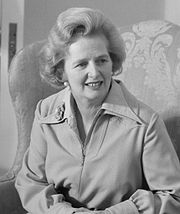

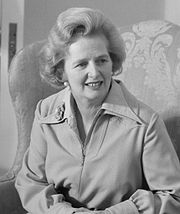

Cradock remained a trusted advisor to then Prime Minister

Margaret Thatcher

, who appointed him as Chairman of the Joint Intelligence Committee in 1985. After the June Fourth Incident, he was the first senior British official to pay a visit to the Chinese leadership in the hope of maintaining the much criticised Joint Declaration. He was successful in fighting to guarantee in the Basic Law of Hong Kong that half of the seats of the Legislative Council

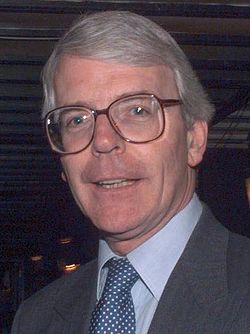

would be directly elected by 2007. However, Cradock worsened his relationship with Thatcher's successor, John Major

, by forcing him to visit China

in 1991 after the row between the two countries over the Airport Core Programme

of Hong Kong. Major had enough of the compromising attitude of Cradock and then Governor of Hong Kong

, Sir David Wilson

, and finally decided to have both of them replaced in 1992, choosing instead his Conservative

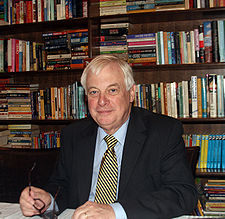

-ally Chris Patten

as Governor.

Unlike his predecessors, Patten was strongly criticized by the Chinese authority during his governorship because he introduced a series of democratic reforms without consulting them. Although Cradock had retired, he joined the pro-Beijing camp

and became one of the most prominent critics of Governor Patten, censuring him for wrecking the hand-over agreement that was blessed by the Chinese government

. Cradock and Patten blamed each other publicly a number of times in the final years of Hong Kong under British-rule. He once famously denounced Patten as an "incredible shrinking Governor", while Patten mocked him openly, in another occasion, as a "dyspeptic retired ambassador" suffering from "Craddockitis".

Cradock spent his later years in writing a number of books on realpolitik

diplomacy and was a non-executive director of the South China Morning Post

.

, County Durham

, to a farming family. He was educated at Alderman Wraith Grammar School in Spennymoor

in his childhood when he experienced the decline of the local mining industry, influencing him to become a devoted supporter of Labour

for a considerable long time. He was enlisted in the Royal Air Force

during the Second World War, and after that, entered St John's College, Cambridge

, being the first ever Cradock to enter university in his family history.

Cradock studied law

and English language

in the university. His outstanding performance secured him a number of scholarships. From the university he also developed his interest in sinology

by appreciating the works of Chinese and Japanese literature translated by Arthur Waley

.

In 1950, he defeated his pro-Conservative opponent, Norman St John-Stevas, to become Chairman of the Cambridge Union Society

. He subsequently authored a well-received book of the history of the Society in 1953, covering the period from 1815 to 1939. After obtaining the Master of Arts

degree, he remained as a law tutor in his alma mater and further obtained an LL.M. In 1953, he was admitted to the bar by the Middle Temple

. In 1982, he was bestowed an honorary fellowship by St John's College.

headquarters from 1954 to 1957, and was then posted to the British High Commission in Kuala Lumpur

, Malaya

(now Malaysia), as First Secretary from 1957 to 1961. He was sent to Hong Kong in 1961 to learn Mandarin

, and in the next year became Chinese Secretary of the British charge d'affaires office in Peking, the People's Republic of China. From 1963 to 1966, he was posted back to London, but was sent to Peking for the second time in 1966 serving as political counsellor and officer-in-charge.

Although the political situation in China by then was growing increasingly unstable, Cradock and his colleagues managed to maintain the safety of the office at the onset of the Cultural Revolution. Nevertheless, the situation was much worsened soon in 1967 when the leftist rioting in the mainland China

spread to Hong Kong, causing the colonial government to adopt tough action to suppress a series of leftist demonstrations and strikes. The suppression was generally supported by the local residents of Hong Kong, but anti-British sentiment in mainland China was greatly aroused. Many in Peking were enraged by the "imperialism

presence" in China and viewed the British charge d'affaires office as a target to express their anger.

On 22 August 1967, a large group of Red Guards and their followers marched to the charge d'affaires office and surrounded the office building, summoning a "Conference to Condemn the Anti-Chinese Crime Committed by British Imperialists". At night, the Red Guards and the mobs rushed into the office, setting fire to the building and the cars outside. The fire forced the charge d'affaires, Sir Donald Hopson, and Cradock to lead the staff and their family members escaping from the building, and to "surrender" to the mobs. It was reported that Cradock was ordered by the Red Guards to kow-tow to a portrait of Mao Zedong

, an act that he firmly refused. During the chaotic scene, Cradock and other British subjects were manhandled, and some of them, both male and female, were sexually harassed before rescued by the People's Liberation Army

. After rescue, Cradock, Hopson and other British subjects were put under house arrest

in the embassy zone in central Peking for months, until the political situation cooled down in the end of 1967.

For his services during and after the chaos, Cradock was appointed a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George in 1968, and succeeded Hopson as charge d'affaires from August 1968 before returning to London in February 1969. Back in London, Cradock became head of the Planning Staff of the Foreign Office from 1969 to 1971, and then an Under-Secretary and head of the Assessments Staff of the Cabinet Office

, serving under two Prime Ministers, firstly, Sir Edward Heath

, and secondly, Harold Wilson

. Cradock took up his first ambassadorial post from 1976 to 1978 as British Ambassador to the East Germany. He also led the British delegation to the Comprehensive Test Ban Discussions at Geneva

, Switzerland

, from 1977 to 1978.

By then, the top management in the Hong Kong Government and some land developers in Hong Kong became aware of the question of 1997, feeling increasingly uncertain of the future validity of land leases. The colony of Hong Kong was basically made up of Hong Kong Island

and Kowloon

which were ceded to Britain respectively in 1842 and 1860, and the New Territories

, which unlike the first two regions was only leased to the United Kingdom for a 99-year term beginning from 1898. Since the 99-year lease would expire roughly twenty-five years after in 1997, they began to notice that land leases in the New Territories approved by the colonial government might not subsist beyond 1997.

To test the attitude of the Chinese government to the validity of the leases, the Governor, Sir Murray MacLehose, accompanied by the Senior Unofficial Member

of the Executive Council

, Sir Yuet-keung Kan

, and the Political Advisor to the Governor, (later Sir) David Wilson, accepted an invitation from the Chinese government to visit Peking in 1979. The purpose of the visit appeared highly sensitive to the British government. In Hong Kong, only MacLehose, Kan and Wilson knew the purpose of their mission, which was facilitated by Youde in London and Cradock in Peking, and was endorsed by the Foreign Secretary, Dr David Owen

. However, unexpectedly, the leader of the Communist China Deng Xiaoping

simply disregarded the question of land leases and firmly insisted in taking over the whole of Hong Kong on or before 1997. The visit ended in dramatically unveiling the prelude of the Sino-British negotiations over the future of Hong Kong.

Following the victory of the Conservatives in the general election in 1979, the new Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, adopted a tough line in diplomacy and the question of Hong Kong was no exception. Not long after the military victory of the United Kingdom over Argentina

Following the victory of the Conservatives in the general election in 1979, the new Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, adopted a tough line in diplomacy and the question of Hong Kong was no exception. Not long after the military victory of the United Kingdom over Argentina

in the Falklands War

, Thatcher, accompanied by Cradock and Youde, who was now Governor of Hong Kong, paid a visit to Peking on 22 September 1982 in the hope of persuading the Chinese government not to insist on claiming the sovereignty of Hong Kong. During her visit, Thatcher and Cradock discussed the matter with the Chinese leadership, including Chinese Premier Zhao Ziyang

and Deng Xiao-ping. Although both sides agreed that a formal negotiation over the future of Hong Kong should be held without delay, their views further clashed on 24 September when Thatcher emphasized in a meeting with Deng in the Great Hall of the People

that the Sino-British Treaty of Nanking

, Convention of Peking

and the Convention for the Extension of Hong Kong Territory

were still valid, a fact that was firmly denied by Deng, who instead insisted that China must take over Hong Kong by 1997 regardless of the treaties. When Thatcher, Cradock and Youde left the Great Hall after their meeting with Deng, she accidentally slipped on the steps outside. The sensational scene was described by the local media as a sign hinting the defeat of the "Iron Lady

" by the "shortie" (i.e. Deng).

Following Thatcher's visit to China, the first round of Sino-British negotiations began in Peking from October 1982 to June 1983 with Cradock as the British chief negotiator. However, due to the heavy clashes of views, the negotiations saw little success. Craddock feared that prolonged or broken talks would put China in an advantageous position and would slowly give the chance for China to unilaterally decide the future of Hong Kong, at a time when 1997 was approaching. In this regard, Cradock advised Thatcher to compromise with China so as to let Britain retain some degree of influence over the Hong Kong issue, and one of the major concessions was to stop insisting upon the three treaties. In a letter to the Chinese authority towards the end of the first round of negotiations, Thatcher wrote that if the result of the negotiations was accepted by the people of Hong Kong, the British government would recommend Parliament

to transfer the sovereignty of Hong Kong

to China. The letter indicated Thatcher's shift to a softened stance, which paved the way for the second round of negotiations.

In July 1983, the United Kingdom and China began their second round of negotiations in Peking, with Cradock remaining as the British chief negotiator. Other British negotiators included Governor Youde and Political Advisor to the Governor, Robin McLaren

. The Chinese negotiation team was first chaired by Yao Guang, later succeeded by Zhou Nan

. Similarly to the first round, both sides found each other difficult. During the negotiations, Britain suggested that the sovereignty of Hong Kong could be transferred to China in 1997, but to ensure the prosperity of Hong Kong, Britain should be given the right to rule beyond 1997. This suggestion was heavily criticised by Zhou as "replacing the three unequal treaties by a new one", thus forcing the talks into a stalemate again.

The sign of failure of the United Kingdom in the Sino-British talks and the uncertainty of the future of Hong Kong greatly weakened the confidence of the people of Hong Kong in their future, which in turn provoked a crisis of confidence. In September 1983, the foreign exchange market

recorded a sudden plummet of the exchange rate

of the Hong Kong Dollar

against the US Dollar. The drop of the Hong Kong Dollar instantly triggered a brief public panic in Hong Kong with crowds of people rushing to food stalls, trying to buy every bag of rice

, food and daily commodities available. To stabilise the Hong Kong Dollar and to rebuild the confidence of the general public, the Hong Kong Government swiftly introduced the Linked Exchange Rate System in October, fixing the exchange rate at HK$7.8 per US Dollar. Nevertheless, the Chinese government accused the Hong Kong Government of deliberately manipulating the plummet of the Hong Kong Dollar, and threatened that if the Sino-British talks could not reach a satisfactory outcome within a year, they would unilaterally take the sovereignty of Hong Kong in their own way by 1997.

Cradock was deeply worried that China would leave the negotiation table and would act alone. With much effort, he managed to convince the government in November 1983 that the United Kingdom would surrender any claims on sovereignty or power of governance over Hong Kong after 1997. Such a move was generally regarded as the second major concession offered by the United Kingdom. After that, both sides reached consensus over a number of basic principles in the negotiations, including the implementation of "One Country Two Systems" after the transfer of sovereignty, the establishment of the Sino-British Joint Liaison Group

before the transfer, and the creation of a new class of British nationality for the British nationals in Hong Kong, mostly ethnic Chinese

, without offering them the right of abode

in the United Kingdom. Although Cradock was succeeded by Sir Richard Evans as the British chief negotiator in January 1984, Cradock had made most of the agreements which later formed the foundation of the Sino-British Joint Declaration. To acknowledge his critical role in the Sino-British negotiations, he was promoted a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George in 1983, having been a Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George since 1980.

After rounds of negotiations, the Sino-British Joint Declaration was finally initialled by representatives of both Britain and China on 26 September 1984, and on 19 December, the Joint Declaration was formally signed by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and Chinese Premier Zhao Ziyang in the Great Hall of the People. As one of the main draftsmen of the Joint Declaration, Cradock also witnessed the signing in person. However, the Joint Declaration could not bring confidence to the people of Hong Kong. According to an opinion poll

conducted shortly afterwards, only 16% of the respondents felt secured by it, while 76% of the respondents held a reserved attitude. Furthermore, 30% believed that "One Country Two Systems" suggested in the Joint Declaration would be unworkable, showing that the general public of Hong Kong were unsecured and in doubt towards the agreement made between Britain and China.

as Britain's biggest adversary, while the United States

was the most important ally, and therefore they could always head to the same direction when making diplomatic decisions. Cradock continued to serve as her advisor through the general election in 1987,

When John Major succeeded Thatcher as the Prime Minister in 1990, Cradock continued to work in 10 Downing Street

, but his relationship with Major was not as good as with Thatcher. On 7 February 1991, when Major was holding a cabinet

meeting at Number 10, the Provisional IRA launched a mortar bomb at the building, smashing all the windows of the conference room. Fortunately, no one in the cabinet meeting, including Cradock, was injured by the terrorist attack.

Since the Joint Declaration was signed in 1984, Hong Kong had entered its last thirteen years of British colonial rule, which was also known as the "transitional period". During the period, China and Britain continued to discuss the details of the transfer of sovereignty of Hong Kong scheduled for 1997. Nevertheless, when the Tiananmen Square crackdown occurred on 4 June 1989, Hong Kong fell into a new series of confidence crisis. An unprecedented one million people assembled in downtown Central

, expressing their anger towards the Communist regime's military suppression of the peaceful student rally in Peking which was in support of freedom and democracy

in China. After the crackdown, the talks between Britain and China came to a halt, with an international boycott of China. In Hong Kong and the United Kingdom, public opinion called for the British government to denounce and abandon the Sino-British Joint Declaration, and many felt worried about transferring Hong Kong from Britain to the Communist regime. Among them, the Senior Unofficial Member of the Executive Council of Hong Kong, Dame Lydia Dunn

, even publicly urged Britain not to hand over British subjects in Hong Kong to a regime that "did not hesitate to use its tanks and forces

on its own people".

Cradock was instructed to visit Peking secretly in the end of 1989, trying to maintain the Joint Declaration and to cool down the Communist antipathy

Cradock was instructed to visit Peking secretly in the end of 1989, trying to maintain the Joint Declaration and to cool down the Communist antipathy

in Hong Kong. In Peking, he tirelessly lobbied China to guarantee a greater degree of freedom and democracy in post-1997 Hong Kong. It was by his efforts that China agreed to gradually promote democratization

in the future Hong Kong Special Administrative Region by allowing half of the sixty seats of the Legislative Council to be directly elected by 2007, and that was achieved in 2004. The promise guaranteed by China was subsequently reassured in the Annex II of the Basic Law of Hong Kong promulgated in 1990. With the consent of Britain, any reform of the colonial Legislative Council before 1997 would have to be endorsed by China, so as to allow the colonial legislature a ticket for the so called "through-train", enabling it to be smoothly transferred to the post-1997 Hong Kong. Besides, Cradock suggested that the post of "Deputy Governor

" could be created for the future Chief Executive

-elect in order to let the future leader of Hong Kong get ready for the job before 1997. Cradock believed that these measures would be effective in maintaining the prosperity of Hong Kong, and in the long run, he believed all the seats of the Legislative Council would be directly elected.

Apart from the above measures, to rebuild confidence of the people of Hong Kong towards their future, Governor Sir David Wilson introduced the Airport Core Programme

, which was also known as the "Rose Garden Project", in his annual Policy Address to the Legislative Council in October 1989. However, as the projected cost was very expensive and the programme would endure across 1997, the Chinese government soon critically accused that the "Rose Garden Project" was in fact a plot of Britain to squander Hong Kong's abundant foreign exchange reserves

, and a tactic to secretly withdraw the capitals back to the United Kingdom. They even threatened that they would not "bless" the project. The British government was anxious to gain the support of China. They secretly sent Cradock to China for several occasions in 1990 and 1991, "explaining" the details of the new airport project to the Chinese leaderships and reassuring to Chairman of the Central Military Commission

of the Chinese Communist Party Jiang Zemin

that the new airport

would not bring any harm to China. Despite his reassurance, Jiang insisted that the dispute could not be solved unless Prime Minister John Major visited China and to sign a memorandum.

Under the pressure from China, Major was forced to visit Peking unwillingly and signed the Memorandum of Understanding Concerning the Construction of the New Airport in Hong Kong and Related Questions with China on 3 September 1991. In the Memorandum, Britain promised to reserve not less than HK$25 billion for the future government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region in exchange for the support of China over the Airport Core Programme. Furthermore, Britain agreed in the Memorandum to adopt a proactive attitude to assist in reducing the government debts of Hong Kong after 1997. In fact, Major felt angry of the visit because he became the first Western leader to pay visit to China after the June Fourth Incident in 1989, while the international community was still boycotting China. After the new airport episode, it was felt by the Conservatives government that the soft diplomacy

was no longer effective to China, and Major concluded that Cradock and Governor Wilson were too kind to the Chinese authority and should take the responsibility.

The first to go was Governor Wilson. In the New Year Honours List of 1992, it was unexpectedly announced that he would be made a life peer

and be elevated to the House of Lords

. Shortly afterwards, although Wilson had three more years before reaching the normal retirement age of 60, the British government suddenly announced that the governorship of Wilson would be ended soon and would not be extended. Unlike the general practice, the British government did not say who would succeed Wilson as the next Governor of Hong Kong, thus leaving a lot of speculation that Wilson was forced to quit due to his weakness. When Wilson quit in July 1992, the governorship was succeeded by Chris Patten, who was Major's Conservatives-ally, a politician

and a former Member of the Parliament who was recently defeated in the general election. A few months later, the British government announced that Cradock was to step down as Chairman of the Joint Intelligence Committee and Foreign Affairs Advisor. In the announcement, the government left no compliments to Cradock, signifying the discontent of Major.

Soon after assuming the governorship, Patten adopted a tough-line with China, which was completely different from his predecessors. In his first Policy Address

issued in October 1992, he vowed that all the seats of the Legislative Council would be directly and democratically elected in 1995, when would be the last election before 1997, with a view to accelerate the pace of democratization of Hong Kong and to protect the fundamental human rights of the Hong Kong people. Even though his decision was popularly welcomed by the public opinions in both Hong Kong and Britain, Patten put himself in a stormed and severe relationship with China. When his political reform package was passed by the Legislative Council in 1994, the Chinese government decided to terminate the originally planned "through-train" arrangement, and to set up their own Provisional Legislative Council

unilaterally, affirming that the colonial Legislative Council would not survive after 1997. Also, the planned creation of the post of "Deputy Governor" was aborted.

Governor Patten was much blamed by the Chinese authority for his democratic reform, with Director of Hong Kong and Macao Affairs Office

of the State Council of the People's Republic of China

, Lu Ping, once famously denounced him as a "sinner to be condemned for thousands of years". In the quarrel between Patten and the Chinese government, Cradock stood firmly against Patten and criticised him in many occasions, blaming him for damaging the planned road-map which had been endorsed by both the British and Chinese governments. In 1995, Cradock publicly said in an interview that "He [referring to Patten] has made himself so obnoxious to the Chinese" and later in another occasion, he described Patten as the "incredible shrinking Governor". Yet, Patten did not remain silent and struck back in a Legislative Council meeting, publicly ridiculing him as a "dyspeptic retired ambassador". From 1992 to 1997, both Cradock and Patten criticised each other in many occasions which made them in very bad terms. Although Cradock was invited by the British government to attend the ceremony of the transfer of the sovereignty of Hong Kong on 30 June 1997, Cradock felt that they would not like him to be there and turned down the invitation.

, in western London on 6 February 2010. Some of his former colleagues, such as former Chief Secretary of Hong Kong, Sir David Akers-Jones

, were grieved over his death, but others like the founding chairman of the Democratic Party of Hong Kong Martin Lee

commented adversely by saying "I don't think he was Hong Kong's friend".

and food

from the mainland China, secondly, the British Armed Forces

stationing in Hong Kong were too weak to defend Hong Kong from the strong military presence of China's People's Liberation Army in the Far East

, and thirdly, to sustain Hong Kong's prosperity and economic development in future, Britain must cooperate with China. From the legal point of view, Cradock believed that since the Convention for the Extension of Hong Kong Territory

would expire in 1997, Britain would no longer be able to govern Hong Kong effectively thereafter because the New Territories

would have to be returned to China even though Hong Kong Island

and Kowloon

would not, and that was one of the main reasons why he advised Thatcher to compromise with China. He concluded that the solution that would best serve the interests of Hong Kong was to prevent China from acting unilaterally and to fight for the interests of the Hong Kong people within a limited and mutually agreed framework.

However, the attitude of Cradock was heavily criticised. After the Sino-British Joint Declaration was signed, the general public opinions in Hong Kong and Britain were that it could not rebuild the confidence of the Hong Kong people towards their future. Many critics even denounced Britain and the Joint Declaration as betraying the Hong Kong people and the future of Hong Kong. Among them, the Economist

attacked that both Cradock and Thatcher made no difference from former Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain

who betrayed Czechoslovakia

to Nazi Germany

by signing the Munich Agreement

with Adolf Hitler

in 1938. Apart from that, some commentators suggested that Cradock had no reason to concur with China's view on the validity of the three treaties because under the general practice of the international law

, one must conclude a new treaty in order to invalidate and replace the old one, and therefore the three treaties were actually still in force.

It was also commented that Cradock was indeed not a liberalist because he and the British government did not act for the interests of Hong Kong on the negotiation table. In fact, the British government believed that maintaining a friendly Sino-British relationship was the utmost importance in preserving the British business interests in China. To give-up Hong Kong in exchange for a long-term friendship with China was regarded as profitable especially to the business sector in the United Kingdom. In addition, as the Joint Declaration was designed to bring stability to Hong Kong, it effectively closed the "back door" of Britain and therefore avoided a possible influx of 3 million British subjects of Hong Kong to seek asylum or right of abode there.

Cradock was a bitter critic of Governor Patten's political and democracy reform, blaming him for enraging the Chinese government of which he thought Patten should be responsible for. He also blamed that the reform package damaged the agreed "through-train" arrangement and other transitional arrangements, and would only bring adverse effect to the democratization of post-1997 Hong Kong. Nevertheless, his pro-Beijing standpoint attracted much opposition and criticism in the United Kingdom and Hong Kong. The mainstream public opinion at that time was that the memory of the Tiananmen crackdown was still vividly in the mind of many Hong Kong people, and that was why Britain had the responsibility to adequately safeguard the human rights in Hong Kong, and to show support for Patten's political reform. Even though the colonial legislature would not survive after 1997, many thought that his reform was worthwhile for Hong Kong to experience the benefits resulting from a democratically elected Legislative Council, and to voice out the discontent of the Hong Kong residents to the Chinese government by voting in the election. The Foreign Affairs Select Committee of the House of Commons also stated that it would be disreputable for the United Kingdom for not introducing political reform in response to the demand of the people of Hong Kong.

Although Governor Patten's political reform was generally supported in Hong Kong, Cradock insisted that if Britain stood against China, Britain would be very difficult to bargain for Hong Kong any more. In an interview in 1996 with The Common Sense, a documentary

produced by the Radio Television Hong Kong

, Cradock commented that the United Kingdom nearly lost all her influence over China because the two countries had been in political dispute. When asked if his attitude was equal to "kow-tow" to China, he admittedly replied that no matter the Hong Kong people were willing or not, Hong Kong must be handed-over to China in 1997. He advised the people of Hong Kong that to build a harmonious relationship with China was always better than confrontation and expressing discontent. On the other hand, in the interview, he called for the Hong Kong people to face the reality and not to believe in any illusion and false hope of democracy brought forward by Chris Patten. When asked if he was advising the Hong Kong people to obey China on everything, he said that the people of Hong Kong should know who their "Master" was and what they could do was to try their best to convince the Chinese authority to follow what was written in the Joint Declaration, but he reiterated that most importantly, they must face the reality.

In response to Cradock's criticisms on the political reform, Governor Patten struck back in a number of occasions, and in the Legislative Council meeting on 13 July 1995, he publicly mocked Cradock and those who appeased with China as suffering from "Craddockitis":

Though Cradock was in bad terms with Patten, he was highly valued by the Chinese government and the pro-Beijing camp. They generally praised him for playing a vital role in the making of the Sino-British Joint Declaration. The Xinhua News Agency

, the official news agency of the Chinese authority, once described that Cradock was a "friend of China and an experienced British diplomat who at the same time bears in mind to safeguard the interests of his country…History has proved his sincerity and objectivity."

.

British people

The British are citizens of the United Kingdom, of the Isle of Man, any of the Channel Islands, or of any of the British overseas territories, and their descendants...

diplomat

Diplomat

A diplomat is a person appointed by a state to conduct diplomacy with another state or international organization. The main functions of diplomats revolve around the representation and protection of the interests and nationals of the sending state, as well as the promotion of information and...

, civil servant and sinologist who served as British Ambassador to the People's Republic of China from 1978 to 1983, playing a significant role in the Sino-British negotiations which led up to the signing of the Sino-British Joint Declaration

Sino-British Joint Declaration

The Sino-British Joint Declaration, formally known as the Joint Declaration of the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the Government of the People's Republic of China on the Question of Hong Kong, was signed by the Prime Ministers, Zhao Ziyang and Margaret...

in 1984.

Joining the Foreign Office in 1954, Cradock served primarily in Asia

Asia

Asia is the world's largest and most populous continent, located primarily in the eastern and northern hemispheres. It covers 8.7% of the Earth's total surface area and with approximately 3.879 billion people, it hosts 60% of the world's current human population...

and was posted to the British charge d'affaires office in Peking (now Beijing) at the outset of the Cultural Revolution

Cultural Revolution

The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, commonly known as the Cultural Revolution , was a socio-political movement that took place in the People's Republic of China from 1966 through 1976...

in 1966. He, along with other British subjects, was manhandled by the Red Guards

Red Guards (China)

Red Guards were a mass movement of civilians, mostly students and other young people in the People's Republic of China , who were mobilized by Mao Zedong in 1966 and 1967, during the Cultural Revolution.-Origins:...

and the mobs when the office was set on fire on 22 August 1967. After the rioting, Cradock served as charge d'affaires

Chargé d'affaires

In diplomacy, chargé d’affaires , often shortened to simply chargé, is the title of two classes of diplomatic agents who head a diplomatic mission, either on a temporary basis or when no more senior diplomat has been accredited.-Chargés d’affaires:Chargés d’affaires , who were...

in Peking from 1968 to 1969, and later succeeded Sir Edward Youde

Edward Youde

Sir Edward Youde GCMG, GCVO, MBE was a British administrator, diplomat and Sinologist. He served as Governor of Hong Kong between 20 May 1982 and 5 December 1986.-Early years:...

as British Ambassador to the People's Republic of China in 1978. His ambassadorship witnessed the start of the Sino-British negotiations in 1982, which subsequently resulted in the Joint Declaration in 1984, an agreement deciding the future of the sovereignty

Sovereignty

Sovereignty is the quality of having supreme, independent authority over a geographic area, such as a territory. It can be found in a power to rule and make law that rests on a political fact for which no purely legal explanation can be provided...

of Hong Kong

Hong Kong

Hong Kong is one of two Special Administrative Regions of the People's Republic of China , the other being Macau. A city-state situated on China's south coast and enclosed by the Pearl River Delta and South China Sea, it is renowned for its expansive skyline and deep natural harbour...

after 1997. However, the move of Cradock, who was the British chief negotiator in the negotiations, to compromise with the Chinese authority was regarded as a major retreat by the general media in Hong Kong and the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

, and was heavily criticized at that time as betraying the people of Hong Kong.

Cradock remained a trusted advisor to then Prime Minister

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the Head of Her Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom. The Prime Minister and Cabinet are collectively accountable for their policies and actions to the Sovereign, to Parliament, to their political party and...

Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher, was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990...

, who appointed him as Chairman of the Joint Intelligence Committee in 1985. After the June Fourth Incident, he was the first senior British official to pay a visit to the Chinese leadership in the hope of maintaining the much criticised Joint Declaration. He was successful in fighting to guarantee in the Basic Law of Hong Kong that half of the seats of the Legislative Council

Legislative Council of Hong Kong

The Legislative Council is the unicameral legislature of Hong Kong.-History:The Legislative Council of Hong Kong was set up in 1843 as a colonial legislature under British rule...

would be directly elected by 2007. However, Cradock worsened his relationship with Thatcher's successor, John Major

John Major

Sir John Major, is a British Conservative politician, who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1990–1997...

, by forcing him to visit China

China

Chinese civilization may refer to:* China for more general discussion of the country.* Chinese culture* Greater China, the transnational community of ethnic Chinese.* History of China* Sinosphere, the area historically affected by Chinese culture...

in 1991 after the row between the two countries over the Airport Core Programme

Airport Core Programme

The Hong Kong Airport Core Programme was a series of infrastructure projects centred around the new Hong Kong International Airport during the early 1990s...

of Hong Kong. Major had enough of the compromising attitude of Cradock and then Governor of Hong Kong

Governor of Hong Kong

The Governor of Hong Kong was the head of the government of Hong Kong during British rule from 1843 to 1997. The governor's roles were defined in the Hong Kong Letters Patent and Royal Instructions...

, Sir David Wilson

David Wilson, Baron Wilson of Tillyorn

David Clive Wilson, Baron Wilson of Tillyorn, is a retired British administrator, diplomat and Sinologist. Lord Wilson of Tillyorn was the penultimate Commander-in-Chief and 27th Governor of Hong Kong...

, and finally decided to have both of them replaced in 1992, choosing instead his Conservative

Conservative Party (UK)

The Conservative Party, formally the Conservative and Unionist Party, is a centre-right political party in the United Kingdom that adheres to the philosophies of conservatism and British unionism. It is the largest political party in the UK, and is currently the largest single party in the House...

-ally Chris Patten

Chris Patten

Christopher Francis Patten, Baron Patten of Barnes, CH, PC , is the last Governor of British Hong Kong, a former British Conservative politician, and the current chairman of the BBC Trust....

as Governor.

Unlike his predecessors, Patten was strongly criticized by the Chinese authority during his governorship because he introduced a series of democratic reforms without consulting them. Although Cradock had retired, he joined the pro-Beijing camp

Pro-Beijing Camp

The Pro-Beijing Camp, pro-Establishment Camp, pan-Establishment Camp is a segment of Hong Kong society that supports the policies and views of the People's Republic of China before and after the handover of Hong Kong in 1997.It is also nicknamed the royalists or loyalists.The term can be used to...

and became one of the most prominent critics of Governor Patten, censuring him for wrecking the hand-over agreement that was blessed by the Chinese government

Government of the People's Republic of China

All power within the government of the People's Republic of China is divided among three bodies: the People's Republic of China, State Council, and the People's Liberation Army . This article is concerned with the formal structure of the state, its departments and their responsibilities...

. Cradock and Patten blamed each other publicly a number of times in the final years of Hong Kong under British-rule. He once famously denounced Patten as an "incredible shrinking Governor", while Patten mocked him openly, in another occasion, as a "dyspeptic retired ambassador" suffering from "Craddockitis".

Cradock spent his later years in writing a number of books on realpolitik

Realpolitik

Realpolitik refers to politics or diplomacy based primarily on power and on practical and material factors and considerations, rather than ideological notions or moralistic or ethical premises...

diplomacy and was a non-executive director of the South China Morning Post

South China Morning Post

The South China Morning Post , together with its Sunday edition, the Sunday Morning Post, is an English-language Hong Kong newspaper, published by the SCMP Group with a circulation of 104,000....

.

Early years

Percy Cradock was born on 26 October 1923 in Byers GreenByers Green

Byers Green is a village in County Durham, in England. It is situated to the north of Bishop Auckland, between Willington and Spennymoor, and a short distance from the River Wear....

, County Durham

County Durham

County Durham is a ceremonial county and unitary district in north east England. The county town is Durham. The largest settlement in the ceremonial county is the town of Darlington...

, to a farming family. He was educated at Alderman Wraith Grammar School in Spennymoor

Spennymoor

Spennymoor is a town in County Durham, England. It stands above the Wear Valley approximately seven miles south of Durham. The town was founded over 160 years ago...

in his childhood when he experienced the decline of the local mining industry, influencing him to become a devoted supporter of Labour

Labour Party (UK)

The Labour Party is a centre-left democratic socialist party in the United Kingdom. It surpassed the Liberal Party in general elections during the early 1920s, forming minority governments under Ramsay MacDonald in 1924 and 1929-1931. The party was in a wartime coalition from 1940 to 1945, after...

for a considerable long time. He was enlisted in the Royal Air Force

Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force is the aerial warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Formed on 1 April 1918, it is the oldest independent air force in the world...

during the Second World War, and after that, entered St John's College, Cambridge

St John's College, Cambridge

St John's College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. The college's alumni include nine Nobel Prize winners, six Prime Ministers, three archbishops, at least two princes, and three Saints....

, being the first ever Cradock to enter university in his family history.

Cradock studied law

Law

Law is a system of rules and guidelines which are enforced through social institutions to govern behavior, wherever possible. It shapes politics, economics and society in numerous ways and serves as a social mediator of relations between people. Contract law regulates everything from buying a bus...

and English language

English language

English is a West Germanic language that arose in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of England and spread into what was to become south-east Scotland under the influence of the Anglian medieval kingdom of Northumbria...

in the university. His outstanding performance secured him a number of scholarships. From the university he also developed his interest in sinology

Sinology

Sinology in general use is the study of China and things related to China, but, especially in the American academic context, refers more strictly to the study of classical language and literature, and the philological approach...

by appreciating the works of Chinese and Japanese literature translated by Arthur Waley

Arthur Waley

Arthur David Waley CH, CBE was an English orientalist and sinologist.-Life:Waley was born in Tunbridge Wells, Kent, England, as Arthur David Schloss, son of the economist David Frederick Schloss...

.

In 1950, he defeated his pro-Conservative opponent, Norman St John-Stevas, to become Chairman of the Cambridge Union Society

Cambridge Union Society

The Cambridge Union Society, commonly referred to as simply "the Cambridge Union" or "the Union," is a debating society in Cambridge, England and is the largest society at the University of Cambridge. Since its founding in 1815, the Union has developed a worldwide reputation as a noted symbol of...

. He subsequently authored a well-received book of the history of the Society in 1953, covering the period from 1815 to 1939. After obtaining the Master of Arts

Master of Arts (postgraduate)

A Master of Arts from the Latin Magister Artium, is a type of Master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The M.A. is usually contrasted with the M.S. or M.Sc. degrees...

degree, he remained as a law tutor in his alma mater and further obtained an LL.M. In 1953, he was admitted to the bar by the Middle Temple

Middle Temple

The Honourable Society of the Middle Temple, commonly known as Middle Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court exclusively entitled to call their members to the English Bar as barristers; the others being the Inner Temple, Gray's Inn and Lincoln's Inn...

. In 1982, he was bestowed an honorary fellowship by St John's College.

Arson attacks on the British Charge d'affaires Office

In 1954, Cradock gave up his academic career in Cambridge and joined the Foreign Office as a late entrant. He served in the LondonLondon

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

headquarters from 1954 to 1957, and was then posted to the British High Commission in Kuala Lumpur

Kuala Lumpur

Kuala Lumpur is the capital and the second largest city in Malaysia by population. The city proper, making up an area of , has a population of 1.4 million as of 2010. Greater Kuala Lumpur, also known as the Klang Valley, is an urban agglomeration of 7.2 million...

, Malaya

Federation of Malaya

The Federation of Malaya is the name given to a federation of 11 states that existed from 31 January 1948 until 16 September 1963. The Federation became independent on 31 August 1957...

(now Malaysia), as First Secretary from 1957 to 1961. He was sent to Hong Kong in 1961 to learn Mandarin

Standard Mandarin

Standard Chinese or Modern Standard Chinese, also known as Mandarin or Putonghua, is the official language of the People's Republic of China and Republic of China , and is one of the four official languages of Singapore....

, and in the next year became Chinese Secretary of the British charge d'affaires office in Peking, the People's Republic of China. From 1963 to 1966, he was posted back to London, but was sent to Peking for the second time in 1966 serving as political counsellor and officer-in-charge.

Although the political situation in China by then was growing increasingly unstable, Cradock and his colleagues managed to maintain the safety of the office at the onset of the Cultural Revolution. Nevertheless, the situation was much worsened soon in 1967 when the leftist rioting in the mainland China

Mainland China

Mainland China, the Chinese mainland or simply the mainland, is a geopolitical term that refers to the area under the jurisdiction of the People's Republic of China . According to the Taipei-based Mainland Affairs Council, the term excludes the PRC Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong and...

spread to Hong Kong, causing the colonial government to adopt tough action to suppress a series of leftist demonstrations and strikes. The suppression was generally supported by the local residents of Hong Kong, but anti-British sentiment in mainland China was greatly aroused. Many in Peking were enraged by the "imperialism

Imperialism

Imperialism, as defined by Dictionary of Human Geography, is "the creation and/or maintenance of an unequal economic, cultural, and territorial relationships, usually between states and often in the form of an empire, based on domination and subordination." The imperialism of the last 500 years,...

presence" in China and viewed the British charge d'affaires office as a target to express their anger.

On 22 August 1967, a large group of Red Guards and their followers marched to the charge d'affaires office and surrounded the office building, summoning a "Conference to Condemn the Anti-Chinese Crime Committed by British Imperialists". At night, the Red Guards and the mobs rushed into the office, setting fire to the building and the cars outside. The fire forced the charge d'affaires, Sir Donald Hopson, and Cradock to lead the staff and their family members escaping from the building, and to "surrender" to the mobs. It was reported that Cradock was ordered by the Red Guards to kow-tow to a portrait of Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong, also transliterated as Mao Tse-tung , and commonly referred to as Chairman Mao , was a Chinese Communist revolutionary, guerrilla warfare strategist, Marxist political philosopher, and leader of the Chinese Revolution...

, an act that he firmly refused. During the chaotic scene, Cradock and other British subjects were manhandled, and some of them, both male and female, were sexually harassed before rescued by the People's Liberation Army

People's Liberation Army

The People's Liberation Army is the unified military organization of all land, sea, strategic missile and air forces of the People's Republic of China. The PLA was established on August 1, 1927 — celebrated annually as "PLA Day" — as the military arm of the Communist Party of China...

. After rescue, Cradock, Hopson and other British subjects were put under house arrest

House arrest

In justice and law, house arrest is a measure by which a person is confined by the authorities to his or her residence. Travel is usually restricted, if allowed at all...

in the embassy zone in central Peking for months, until the political situation cooled down in the end of 1967.

For his services during and after the chaos, Cradock was appointed a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George in 1968, and succeeded Hopson as charge d'affaires from August 1968 before returning to London in February 1969. Back in London, Cradock became head of the Planning Staff of the Foreign Office from 1969 to 1971, and then an Under-Secretary and head of the Assessments Staff of the Cabinet Office

Cabinet Office

The Cabinet Office is a department of the Government of the United Kingdom responsible for supporting the Prime Minister and Cabinet of the United Kingdom....

, serving under two Prime Ministers, firstly, Sir Edward Heath

Edward Heath

Sir Edward Richard George "Ted" Heath, KG, MBE, PC was a British Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and as Leader of the Conservative Party ....

, and secondly, Harold Wilson

Harold Wilson

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx, KG, OBE, FRS, FSS, PC was a British Labour Member of Parliament, Leader of the Labour Party. He was twice Prime Minister of the United Kingdom during the 1960s and 1970s, winning four general elections, including a minority government after the...

. Cradock took up his first ambassadorial post from 1976 to 1978 as British Ambassador to the East Germany. He also led the British delegation to the Comprehensive Test Ban Discussions at Geneva

Geneva

Geneva In the national languages of Switzerland the city is known as Genf , Ginevra and Genevra is the second-most-populous city in Switzerland and is the most populous city of Romandie, the French-speaking part of Switzerland...

, Switzerland

Switzerland

Switzerland name of one of the Swiss cantons. ; ; ; or ), in its full name the Swiss Confederation , is a federal republic consisting of 26 cantons, with Bern as the seat of the federal authorities. The country is situated in Western Europe,Or Central Europe depending on the definition....

, from 1977 to 1978.

Sino-British negotiations

In 1978, Cradock was posted to Peking for the third time to succeed Sir Edward Youde as British Ambassador to the People's Republic of China, a post created in 1972 to supersede the position of charge d'affaires.By then, the top management in the Hong Kong Government and some land developers in Hong Kong became aware of the question of 1997, feeling increasingly uncertain of the future validity of land leases. The colony of Hong Kong was basically made up of Hong Kong Island

Hong Kong Island

Hong Kong Island is an island in the southern part of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. It has a population of 1,289,500 and its population density is 16,390/km², as of 2008...

and Kowloon

Kowloon

Kowloon is an urban area in Hong Kong comprising the Kowloon Peninsula and New Kowloon. It is bordered by the Lei Yue Mun strait in the east, Mei Foo Sun Chuen and Stonecutter's Island in the west, Tate's Cairn and Lion Rock in the north, and Victoria Harbour in the south. It had a population of...

which were ceded to Britain respectively in 1842 and 1860, and the New Territories

New Territories

New Territories is one of the three main regions of Hong Kong, alongside Hong Kong Island and the Kowloon Peninsula. It makes up 86.2% of Hong Kong's territory. Historically, it is the region described in The Convention for the Extension of Hong Kong Territory...

, which unlike the first two regions was only leased to the United Kingdom for a 99-year term beginning from 1898. Since the 99-year lease would expire roughly twenty-five years after in 1997, they began to notice that land leases in the New Territories approved by the colonial government might not subsist beyond 1997.

To test the attitude of the Chinese government to the validity of the leases, the Governor, Sir Murray MacLehose, accompanied by the Senior Unofficial Member

Senior Unofficial Member

Senior Unofficial Member (首席非官守議員) denotes the highest-ranking unofficial member of the Legislative Council and Executive Council of Hong Kong under Colonial British rule, which supposedly represented the opinions of the unofficial members of same to the Governor of Hong Kong.As Chinese council...

of the Executive Council

Executive Council of Hong Kong

The Executive Council of Hong Kong is a core policy-making organ in the executive branch of the government of Hong Kong.. The Chief Executive of Hong Kong serves as its President.The Executive Council normally meets once a week...

, Sir Yuet-keung Kan

Yuet Keung Kan

Sir Yuet-keung Kan, GBE, Kt, JP is a retired Hong Kong banker, politician and lawyer who was successively appointed Senior Unofficial Member of the Legislative Council and Executive Council in the 1960s and 1970s...

, and the Political Advisor to the Governor, (later Sir) David Wilson, accepted an invitation from the Chinese government to visit Peking in 1979. The purpose of the visit appeared highly sensitive to the British government. In Hong Kong, only MacLehose, Kan and Wilson knew the purpose of their mission, which was facilitated by Youde in London and Cradock in Peking, and was endorsed by the Foreign Secretary, Dr David Owen

David Owen

David Anthony Llewellyn Owen, Baron Owen CH PC FRCP is a British politician.Owen served as British Foreign Secretary from 1977 to 1979, the youngest person in over forty years to hold the post; he co-authored the failed Vance-Owen and Owen-Stoltenberg peace plans offered during the Bosnian War...

. However, unexpectedly, the leader of the Communist China Deng Xiaoping

Deng Xiaoping

Deng Xiaoping was a Chinese politician, statesman, and diplomat. As leader of the Communist Party of China, Deng was a reformer who led China towards a market economy...

simply disregarded the question of land leases and firmly insisted in taking over the whole of Hong Kong on or before 1997. The visit ended in dramatically unveiling the prelude of the Sino-British negotiations over the future of Hong Kong.

Argentina

Argentina , officially the Argentine Republic , is the second largest country in South America by land area, after Brazil. It is constituted as a federation of 23 provinces and an autonomous city, Buenos Aires...

in the Falklands War

Falklands War

The Falklands War , also called the Falklands Conflict or Falklands Crisis, was fought in 1982 between Argentina and the United Kingdom over the disputed Falkland Islands and South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands...

, Thatcher, accompanied by Cradock and Youde, who was now Governor of Hong Kong, paid a visit to Peking on 22 September 1982 in the hope of persuading the Chinese government not to insist on claiming the sovereignty of Hong Kong. During her visit, Thatcher and Cradock discussed the matter with the Chinese leadership, including Chinese Premier Zhao Ziyang

Zhao Ziyang

Zhao Ziyang was a high-ranking politician in the People's Republic of China . He was the third Premier of the People's Republic of China from 1980 to 1987, and General Secretary of the Communist Party of China from 1987 to 1989....

and Deng Xiao-ping. Although both sides agreed that a formal negotiation over the future of Hong Kong should be held without delay, their views further clashed on 24 September when Thatcher emphasized in a meeting with Deng in the Great Hall of the People

Great Hall of the People

The Great Hall of the People is located at the western edge of Tiananmen Square, Beijing, People's Republic of China, and is used for legislative and ceremonial activities by the People's Republic of China and the Communist Party of China. It functions as the People's Republic of China's...

that the Sino-British Treaty of Nanking

Treaty of Nanking

The Treaty of Nanking was signed on 29 August 1842 to mark the end of the First Opium War between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the Qing Dynasty of China...

, Convention of Peking

Convention of Peking

The Convention of Peking or the First Convention of Peking is the name used for three different unequal treaties, which were concluded between Qing China and the United Kingdom, France, and Russia.-Background:...

and the Convention for the Extension of Hong Kong Territory

Convention for the Extension of Hong Kong Territory

The Convention Between Great Britain and China Respecting an Extension of Hong Kong Territory or the Second Convention of Peking was a lease signed between Qing Dynasty and the United Kingdom in 1898.-Background:...

were still valid, a fact that was firmly denied by Deng, who instead insisted that China must take over Hong Kong by 1997 regardless of the treaties. When Thatcher, Cradock and Youde left the Great Hall after their meeting with Deng, she accidentally slipped on the steps outside. The sensational scene was described by the local media as a sign hinting the defeat of the "Iron Lady

Iron Lady

Iron Lady is a nickname that has frequently been used to describe female heads of government around the world. The term describes a "strong willed" woman...

" by the "shortie" (i.e. Deng).

Following Thatcher's visit to China, the first round of Sino-British negotiations began in Peking from October 1982 to June 1983 with Cradock as the British chief negotiator. However, due to the heavy clashes of views, the negotiations saw little success. Craddock feared that prolonged or broken talks would put China in an advantageous position and would slowly give the chance for China to unilaterally decide the future of Hong Kong, at a time when 1997 was approaching. In this regard, Cradock advised Thatcher to compromise with China so as to let Britain retain some degree of influence over the Hong Kong issue, and one of the major concessions was to stop insisting upon the three treaties. In a letter to the Chinese authority towards the end of the first round of negotiations, Thatcher wrote that if the result of the negotiations was accepted by the people of Hong Kong, the British government would recommend Parliament

Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body in the United Kingdom, British Crown dependencies and British overseas territories, located in London...

to transfer the sovereignty of Hong Kong

Transfer of the sovereignty of Hong Kong

The transfer of sovereignty over Hong Kong from the United Kingdom to the People's Republic of China, referred to as ‘the Return’ or ‘the Reunification’ by the Chinese and ‘the Handover’ by others, took place on 1 July 1997...

to China. The letter indicated Thatcher's shift to a softened stance, which paved the way for the second round of negotiations.

In July 1983, the United Kingdom and China began their second round of negotiations in Peking, with Cradock remaining as the British chief negotiator. Other British negotiators included Governor Youde and Political Advisor to the Governor, Robin McLaren

Robin McLaren

Sir Robin John Taylor McLaren KCMG was a British diplomat.McLaren was educated at Ardingly College and St John's College, Cambridge. He was until recently Chairman of Governors at Ardingly College, where the McLaren Library is named after him. He served in the Royal Navy from 1953 to 1955, and...

. The Chinese negotiation team was first chaired by Yao Guang, later succeeded by Zhou Nan

Zhou Nan

Zhou Nan was a prominent Chinese politician and diplomat, and served as Director of the Xinhua News Agency in Hong Kong, Vice Minister of the People's Republic of China's Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and Ambassador to the United Nations...

. Similarly to the first round, both sides found each other difficult. During the negotiations, Britain suggested that the sovereignty of Hong Kong could be transferred to China in 1997, but to ensure the prosperity of Hong Kong, Britain should be given the right to rule beyond 1997. This suggestion was heavily criticised by Zhou as "replacing the three unequal treaties by a new one", thus forcing the talks into a stalemate again.

The sign of failure of the United Kingdom in the Sino-British talks and the uncertainty of the future of Hong Kong greatly weakened the confidence of the people of Hong Kong in their future, which in turn provoked a crisis of confidence. In September 1983, the foreign exchange market

Foreign exchange market

The foreign exchange market is a global, worldwide decentralized financial market for trading currencies. Financial centers around the world function as anchors of trading between a wide range of different types of buyers and sellers around the clock, with the exception of weekends...

recorded a sudden plummet of the exchange rate

Exchange rate

In finance, an exchange rate between two currencies is the rate at which one currency will be exchanged for another. It is also regarded as the value of one country’s currency in terms of another currency...

of the Hong Kong Dollar

Hong Kong dollar

The Hong Kong dollar is the currency of the jurisdiction. It is the eighth most traded currency in the world. In English, it is normally abbreviated with the dollar sign $, or alternatively HK$ to distinguish it from other dollar-denominated currencies...

against the US Dollar. The drop of the Hong Kong Dollar instantly triggered a brief public panic in Hong Kong with crowds of people rushing to food stalls, trying to buy every bag of rice

Rice

Rice is the seed of the monocot plants Oryza sativa or Oryza glaberrima . As a cereal grain, it is the most important staple food for a large part of the world's human population, especially in East Asia, Southeast Asia, South Asia, the Middle East, and the West Indies...

, food and daily commodities available. To stabilise the Hong Kong Dollar and to rebuild the confidence of the general public, the Hong Kong Government swiftly introduced the Linked Exchange Rate System in October, fixing the exchange rate at HK$7.8 per US Dollar. Nevertheless, the Chinese government accused the Hong Kong Government of deliberately manipulating the plummet of the Hong Kong Dollar, and threatened that if the Sino-British talks could not reach a satisfactory outcome within a year, they would unilaterally take the sovereignty of Hong Kong in their own way by 1997.

Cradock was deeply worried that China would leave the negotiation table and would act alone. With much effort, he managed to convince the government in November 1983 that the United Kingdom would surrender any claims on sovereignty or power of governance over Hong Kong after 1997. Such a move was generally regarded as the second major concession offered by the United Kingdom. After that, both sides reached consensus over a number of basic principles in the negotiations, including the implementation of "One Country Two Systems" after the transfer of sovereignty, the establishment of the Sino-British Joint Liaison Group

Sino-British Joint Liaison Group

Sino-British Joint Liaison Group or simply Joint Liaision Group was a meeting group between the Governments of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the People's Republic of China after signing of Sino-British Joint Declaration , a treaty for the transfer of sovereignty of...

before the transfer, and the creation of a new class of British nationality for the British nationals in Hong Kong, mostly ethnic Chinese

Ethnic Chinese

Ethnic Chinese may refer to:*Han Chinese, the dominant ethnic group in the People's Republic of China, Hong Kong, Macao, the Republic of China and Singapore....

, without offering them the right of abode

Right of Abode (United Kingdom)

The right of abode is a status under United Kingdom immigration law that gives an unrestricted right to live in the United Kingdom. It was introduced by the Immigration Act 1971.-British citizens:...

in the United Kingdom. Although Cradock was succeeded by Sir Richard Evans as the British chief negotiator in January 1984, Cradock had made most of the agreements which later formed the foundation of the Sino-British Joint Declaration. To acknowledge his critical role in the Sino-British negotiations, he was promoted a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George in 1983, having been a Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George since 1980.

After rounds of negotiations, the Sino-British Joint Declaration was finally initialled by representatives of both Britain and China on 26 September 1984, and on 19 December, the Joint Declaration was formally signed by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and Chinese Premier Zhao Ziyang in the Great Hall of the People. As one of the main draftsmen of the Joint Declaration, Cradock also witnessed the signing in person. However, the Joint Declaration could not bring confidence to the people of Hong Kong. According to an opinion poll

Opinion poll

An opinion poll, sometimes simply referred to as a poll is a survey of public opinion from a particular sample. Opinion polls are usually designed to represent the opinions of a population by conducting a series of questions and then extrapolating generalities in ratio or within confidence...

conducted shortly afterwards, only 16% of the respondents felt secured by it, while 76% of the respondents held a reserved attitude. Furthermore, 30% believed that "One Country Two Systems" suggested in the Joint Declaration would be unworkable, showing that the general public of Hong Kong were unsecured and in doubt towards the agreement made between Britain and China.

Quarrels leading up to 1997

When Cradock, a diplomat fluent in Mandarin, left the Sino-British talks in the end of 1983, it was rumoured that he would succeed Sir Edward Youde as Governor of Hong Kong. Yet, the rumour never turned into reality, and on the contrary, Cradock, who was dubbed as "Maggie's Mandarin", had become a much trusted advisor to Margaret Thatcher who insisted that he should be posted back to London. By then Cradock had reached the diplomatic retirement age of 60, but Thatcher still appointed him as Deputy Under-Secretary of the Foreign Office and Foreign Affairs Advisor to the Prime Minister, responsible for overseeing the Sino-British negotiations. After the signing of the Joint Declaration in December 1984, he was further appointed as Chairman of the Joint Intelligence Committee in 1985, rendering military strategic advice to the Prime Minister, while remaining as Foreign Affairs Advisor. Critics have commented that the reason for Thatcher entrusting him was because both of them regarded the Soviet UnionSoviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

as Britain's biggest adversary, while the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

was the most important ally, and therefore they could always head to the same direction when making diplomatic decisions. Cradock continued to serve as her advisor through the general election in 1987,

When John Major succeeded Thatcher as the Prime Minister in 1990, Cradock continued to work in 10 Downing Street

10 Downing Street

10 Downing Street, colloquially known in the United Kingdom as "Number 10", is the headquarters of Her Majesty's Government and the official residence and office of the First Lord of the Treasury, who is now always the Prime Minister....

, but his relationship with Major was not as good as with Thatcher. On 7 February 1991, when Major was holding a cabinet

Cabinet of the United Kingdom

The Cabinet of the United Kingdom is the collective decision-making body of Her Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom, composed of the Prime Minister and some 22 Cabinet Ministers, the most senior of the government ministers....

meeting at Number 10, the Provisional IRA launched a mortar bomb at the building, smashing all the windows of the conference room. Fortunately, no one in the cabinet meeting, including Cradock, was injured by the terrorist attack.

Since the Joint Declaration was signed in 1984, Hong Kong had entered its last thirteen years of British colonial rule, which was also known as the "transitional period". During the period, China and Britain continued to discuss the details of the transfer of sovereignty of Hong Kong scheduled for 1997. Nevertheless, when the Tiananmen Square crackdown occurred on 4 June 1989, Hong Kong fell into a new series of confidence crisis. An unprecedented one million people assembled in downtown Central

Central, Hong Kong

Central is the central business district of Hong Kong. It is located in Central and Western District, on the north shore of Hong Kong Island, across Victoria Harbour from Tsim Sha Tsui, the southernmost point of Kowloon Peninsula...

, expressing their anger towards the Communist regime's military suppression of the peaceful student rally in Peking which was in support of freedom and democracy

Democracy

Democracy is generally defined as a form of government in which all adult citizens have an equal say in the decisions that affect their lives. Ideally, this includes equal participation in the proposal, development and passage of legislation into law...

in China. After the crackdown, the talks between Britain and China came to a halt, with an international boycott of China. In Hong Kong and the United Kingdom, public opinion called for the British government to denounce and abandon the Sino-British Joint Declaration, and many felt worried about transferring Hong Kong from Britain to the Communist regime. Among them, the Senior Unofficial Member of the Executive Council of Hong Kong, Dame Lydia Dunn

Lydia Dunn, Baroness Dunn

Lydia Selina Dunn, Baroness Dunn, DBE, JP was the Senior Unofficial Member of the Legislative Council and Executive Council in Hong Kong in 1985-1988 and 1988-1995, after Rogerio Hyndman Lobo and Chung Sze Yuen respectively...

, even publicly urged Britain not to hand over British subjects in Hong Kong to a regime that "did not hesitate to use its tanks and forces

Violence

Violence is the use of physical force to apply a state to others contrary to their wishes. violence, while often a stand-alone issue, is often the culmination of other kinds of conflict, e.g...

on its own people".

Anti-communism

Anti-communism is opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed in reaction to the rise of communism, especially after the 1917 October Revolution in Russia and the beginning of the Cold War in 1947.-Objections to communist theory:...

in Hong Kong. In Peking, he tirelessly lobbied China to guarantee a greater degree of freedom and democracy in post-1997 Hong Kong. It was by his efforts that China agreed to gradually promote democratization

Democratization

Democratization is the transition to a more democratic political regime. It may be the transition from an authoritarian regime to a full democracy, a transition from an authoritarian political system to a semi-democracy or transition from a semi-authoritarian political system to a democratic...

in the future Hong Kong Special Administrative Region by allowing half of the sixty seats of the Legislative Council to be directly elected by 2007, and that was achieved in 2004. The promise guaranteed by China was subsequently reassured in the Annex II of the Basic Law of Hong Kong promulgated in 1990. With the consent of Britain, any reform of the colonial Legislative Council before 1997 would have to be endorsed by China, so as to allow the colonial legislature a ticket for the so called "through-train", enabling it to be smoothly transferred to the post-1997 Hong Kong. Besides, Cradock suggested that the post of "Deputy Governor

Deputy Governor

A Deputy governor is a gubernatorial official who is subordinated to a governor, rather like a Lieutenant governor.-British colonial cases:In the British empire, there were such colonial offices in :...

" could be created for the future Chief Executive

Chief Executive of Hong Kong

The Chief Executive of Hong Kong is the President of the Executive Council of Hong Kong and head of the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. The position was created to replace the Governor of Hong Kong, who was the head of the Hong Kong government during British rule...

-elect in order to let the future leader of Hong Kong get ready for the job before 1997. Cradock believed that these measures would be effective in maintaining the prosperity of Hong Kong, and in the long run, he believed all the seats of the Legislative Council would be directly elected.

Apart from the above measures, to rebuild confidence of the people of Hong Kong towards their future, Governor Sir David Wilson introduced the Airport Core Programme

Airport Core Programme

The Hong Kong Airport Core Programme was a series of infrastructure projects centred around the new Hong Kong International Airport during the early 1990s...

, which was also known as the "Rose Garden Project", in his annual Policy Address to the Legislative Council in October 1989. However, as the projected cost was very expensive and the programme would endure across 1997, the Chinese government soon critically accused that the "Rose Garden Project" was in fact a plot of Britain to squander Hong Kong's abundant foreign exchange reserves

Foreign exchange reserves

Foreign-exchange reserves in a strict sense are 'only' the foreign currency deposits and bonds held by central banks and monetary authorities. However, the term in popular usage commonly includes foreign exchange and gold, Special Drawing Rights and International Monetary Fund reserve positions...

, and a tactic to secretly withdraw the capitals back to the United Kingdom. They even threatened that they would not "bless" the project. The British government was anxious to gain the support of China. They secretly sent Cradock to China for several occasions in 1990 and 1991, "explaining" the details of the new airport project to the Chinese leaderships and reassuring to Chairman of the Central Military Commission

Chairman of the Central Military Commission

The Chairman of the Central Military Commission of the People's Republic of China has overall responsibility for the Central Military Commission. According to Chapter 3, Section 4 of the Constitution of the People's Republic of China, "The Central Military Commission of the People's Republic of...

of the Chinese Communist Party Jiang Zemin

Jiang Zemin

Jiang Zemin is a former Chinese politician, who served as General Secretary of the Communist Party of China from 1989 to 2002, as President of the People's Republic of China from 1993 to 2003, and as Chairman of the Central Military Commission from 1989 to 2005...

that the new airport

Hong Kong International Airport

Hong Kong International Airport is the main airport in Hong Kong. It is colloquially known as Chek Lap Kok Airport , being built on the island of Chek Lap Kok by land reclamation, and also to distinguish it from its predecessor, the closed Kai Tak Airport.The airport opened for commercial...