History of Roman era Tunisia

Encyclopedia

Africa Province

The Roman province of Africa was established after the Romans defeated Carthage in the Third Punic War. It roughly comprised the territory of present-day northern Tunisia, and the small Mediterranean coast of modern-day western Libya along the Syrtis Minor...

. Rome took control of Carthage after the Third Punic War

Third Punic War

The Third Punic War was the third and last of the Punic Wars fought between the former Phoenician colony of Carthage, and the Roman Republic...

(149-146). There was a period of Berber kings

Berber kings of Roman-era Tunisia

During the Second Punic War Rome entered into alliance with Masinissa, son of a Berber king. Masinissa had been driven out of his ancestral realm by a Carthage-backed Berber rival. At the defeat of Carthage Masinissa , a "friend of the Roman people", became King of Numidia for fifty years...

allied with Rome (see prior article). Lands surrounding Carthage were annexed and reorganized, and the city of Carthage rebuilt, becoming the third city of the Empire. A long period of prosperity ensued; a cosmopolitan culture evolved. Trade quickened, the fields yielded their fruits. Settlers from across the Empire migrated here, forming a Latin-speaking ethnic mix. Some Berbers rose in society, e.g., Apuleius

Apuleius

Apuleius was a Latin prose writer. He was a Berber, from Madaurus . He studied Platonist philosophy in Athens; travelled to Italy, Asia Minor and Egypt; and was an initiate in several cults or mysteries. The most famous incident in his life was when he was accused of using magic to gain the...

, while other Berbers remained rural, unlettered, and poor. Several Emperors from Africa reigned. Christianity became strong, and included Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo , also known as Augustine, St. Augustine, St. Austin, St. Augoustinos, Blessed Augustine, or St. Augustine the Blessed, was Bishop of Hippo Regius . He was a Latin-speaking philosopher and theologian who lived in the Roman Africa Province...

; yet it was troubled by the Donatist

Donatist

Donatism was a Christian sect within the Roman province of Africa that flourished in the fourth and fifth centuries. It had its roots in the social pressures among the long-established Christian community of Roman North Africa , during the persecutions of Christians under Diocletian...

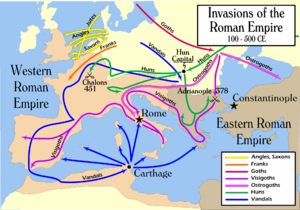

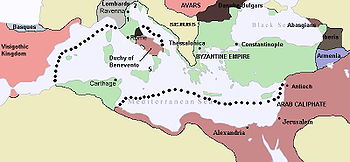

schism. During the eclipse of the Roman Empire, several prominent Berbers revolted. A generation later the Vandals, a Germanic kingdom, arrived and reigned over the former Africa province for nearly a century. A series of Berbers regimes established self-rule at the periphery. The Byzantine Empire eventually recaptured from the Vandals its dominion in 534, which endured until the Islamic conquest, completed in 705. Then came the final undoing of ancient Carthage.

Roman Province of Africa

Third Punic War

The Third Punic War was the third and last of the Punic Wars fought between the former Phoenician colony of Carthage, and the Roman Republic...

(149-146), the Roman Republic

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic was the period of the ancient Roman civilization where the government operated as a republic. It began with the overthrow of the Roman monarchy, traditionally dated around 508 BC, and its replacement by a government headed by two consuls, elected annually by the citizens and...

annexed the city and its vicinity, including rich and developed agricultural lands; their long-time Berber ally Massinissa had died shortly before the fall of the city.

This region became the Roman Province of Africa

Africa Province

The Roman province of Africa was established after the Romans defeated Carthage in the Third Punic War. It roughly comprised the territory of present-day northern Tunisia, and the small Mediterranean coast of modern-day western Libya along the Syrtis Minor...

, named after the Berbers for the Latins knew Afri

Afri

Afri was a Latin name for the Carthaginians. It was received by the Romans from the Carthaginians, as a native term for their country....

as a local word for region's Berber people

Berber people

Berbers are the indigenous peoples of North Africa west of the Nile Valley. They are continuously distributed from the Atlantic to the Siwa oasis, in Egypt, and from the Mediterranean to the Niger River. Historically they spoke the Berber language or varieties of it, which together form a branch...

.

Adjacent lands to the west were allocated to their Berber allies, who continued to enjoy recognition as independent Berber kingdoms. At first the old city Utica

Utica, Tunisia

Utica is an ancient city northwest of Carthage near the outflow of the Medjerda River into the Mediterranean Sea, traditionally considered to be the first colony founded by the Phoenicians in North Africa...

, north of ruined Carthage, served as provincial capital; yet Carthage was rebuilt eventually.

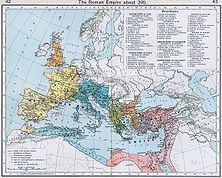

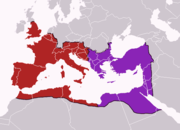

Africa Province then came to encompass the northern half of modern Tunisia, an adjacent region of Algeria

Algeria

Algeria , officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria , also formally referred to as the Democratic and Popular Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of Northwest Africa with Algiers as its capital.In terms of land area, it is the largest country in Africa and the Arab...

(i.e., all of ancient Numidia

Numidia

Numidia was an ancient Berber kingdom in part of present-day Eastern Algeria and Western Tunisia in North Africa. It is known today as the Chawi-land, the land of the Chawi people , the direct descendants of the historical Numidians or the Massyles The kingdom began as a sovereign state and later...

), plus coastal regions stretching about 400 km to the east (into modern Libya

Libya

Libya is an African country in the Maghreb region of North Africa bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Sudan to the southeast, Chad and Niger to the south, and Algeria and Tunisia to the west....

), known then as Tripolitania

Tripolitania

Tripolitania or Tripolitana is a historic region and former province of Libya.Tripolitania was a separate Italian colony from 1927 to 1934...

.

People from all over the Empire migrated into the Roman Africa Province, most importantly merchants, traders, and mainly veterans

Roman army

The Roman army is the generic term for the terrestrial armed forces deployed by the kingdom of Rome , the Roman Republic , the Roman Empire and its successor, the Byzantine empire...

in early retirement who settled in Africa on farming plots promised for their military service. Historians like Theodore Mommsen estimated that under Hadrian

Hadrian

Hadrian , was Roman Emperor from 117 to 138. He is best known for building Hadrian's Wall, which marked the northern limit of Roman Britain. In Rome, he re-built the Pantheon and constructed the Temple of Venus and Roma. In addition to being emperor, Hadrian was a humanist and was philhellene in...

nearly 1/3 of the eastern Numidia population (roughly modern Tunisia

Tunisia

Tunisia , officially the Tunisian RepublicThe long name of Tunisia in other languages used in the country is: , is the northernmost country in Africa. It is a Maghreb country and is bordered by Algeria to the west, Libya to the southeast, and the Mediterranean Sea to the north and east. Its area...

) was descended from Roman veterans.

A sizable Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

speaking population developed that was multinational in background, sharing the region with those speaking Punic and Berber

Berber languages

The Berber languages are a family of languages indigenous to North Africa, spoken from Siwa Oasis in Egypt to Morocco , and south to the countries of the Sahara Desert...

languages.

City of Carthage

The rise of the city of Carthage from the ashes began under Julius CaesarJulius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar was a Roman general and statesman and a distinguished writer of Latin prose. He played a critical role in the gradual transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire....

(100-44) and continued under Augustus

Augustus

Augustus ;23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14) is considered the first emperor of the Roman Empire, which he ruled alone from 27 BC until his death in 14 AD.The dates of his rule are contemporary dates; Augustus lived under two calendars, the Roman Republican until 45 BC, and the Julian...

(63 - AD 14), notwithstanding reported ill omens. It became the new capital of Africa Province

Africa Province

The Roman province of Africa was established after the Romans defeated Carthage in the Third Punic War. It roughly comprised the territory of present-day northern Tunisia, and the small Mediterranean coast of modern-day western Libya along the Syrtis Minor...

. Resident in the city was a Roman praetor

Praetor

Praetor was a title granted by the government of Ancient Rome to men acting in one of two official capacities: the commander of an army, usually in the field, or the named commander before mustering the army; and an elected magistratus assigned varied duties...

or proconsul

Proconsul

A proconsul was a governor of a province in the Roman Republic appointed for one year by the senate. In modern usage, the title has been used for a person from one country ruling another country or bluntly interfering in another country's internal affairs.-Ancient Rome:In the Roman Republic, a...

. Carthage as the urban center of the Roman Africa not only recovered, but flourished, especially during the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd centuries. Yet only about one sixth of the population could participate fully in the culture of city life, as "the other five sixths lived in a poverty that was at times terribly hard to bear and almost impossible to escape." Nonetheless, public buildings and spaces, such as the thermal baths, were available. "For a pittance, a poor man could surround himself with splendid marble halls, the finest art and the most pleasant of atmospheres."

Roman villa

A Roman villa is a villa that was built or lived in during the Roman republic and the Roman Empire. A villa was originally a Roman country house built for the upper class...

of the countryside, many large mosaics formed the floors of courtyards and patios. Beyond the city, many pre-existing Punic and Berber towns found fresh vigor and prosperity. Many new settlements were founded, especially in the rich and fertile Bagradas (modern Medjerda)river valley, north and northwest of Carthage. An aqueduct

Aqueduct

An aqueduct is a water supply or navigable channel constructed to convey water. In modern engineering, the term is used for any system of pipes, ditches, canals, tunnels, and other structures used for this purpose....

about 120 km. in length, built by the Emperor Hadrian

Hadrian

Hadrian , was Roman Emperor from 117 to 138. He is best known for building Hadrian's Wall, which marked the northern limit of Roman Britain. In Rome, he re-built the Pantheon and constructed the Temple of Venus and Roma. In addition to being emperor, Hadrian was a humanist and was philhellene in...

(r.117-138), travels from a sanctuary high up Jbel Zaghouan overland about 70 km. to ancient Carthage. It was repaired and put into use during the 13th century, and again in modern times.

Carthage, and other cities in Roman Africa, contain the ruins or the remains of large structures dedicated to popular spectacles. The urban games performed there included the infamous blood sports, with gladiators

Gladiators

Gladiators is a British television series produced by LWT for ITV on Saturdays nights from 10 October 1992 to 1 January 2000. It is an adaptation of the United States game show American Gladiators. An Australian spin-off and a Swedish one followed...

who fought wild beasts or each other for the whim of the crowd. The Telegenii was one of the gladiator associations of the region. Although often of humble origins, a handsome, surviving gladiator might be "considered someone worthy of adulation by the young ladies of the audience."

Another city entertainment was the theater. The renowned Greek tragedies and comedies were staged, as well as contemporary Roman plays. Burlesque performances by mime

Mime

The word mime is used to refer to a mime artist who uses a theatrical medium or performance art involving the acting out of a story through body motions without use of speech.Mime may also refer to:* Mime, an alternative word for lip sync...

s were popular. Much more costly and less vulgar were productions featuring pantomime

Pantomime

Pantomime — not to be confused with a mime artist, a theatrical performer of mime—is a musical-comedy theatrical production traditionally found in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Jamaica, South Africa, India, Ireland, Gibraltar and Malta, and is mostly performed during the...

s. The African writer Apuleius

Apuleius

Apuleius was a Latin prose writer. He was a Berber, from Madaurus . He studied Platonist philosophy in Athens; travelled to Italy, Asia Minor and Egypt; and was an initiate in several cults or mysteries. The most famous incident in his life was when he was accused of using magic to gain the...

(c.125-c.185) describes attending such a performance which he found impressive and delightful. An ancient epitaph

Epitaph

An epitaph is a short text honoring a deceased person, strictly speaking that is inscribed on their tombstone or plaque, but also used figuratively. Some are specified by the dead person beforehand, others chosen by those responsible for the burial...

here celebrates Vincentius, an popular pantomime (quoted in part):

He lives forever in the thoughts of the people... just, good and in his every relationship with each person irreproachable and sure. There was never a day when, during his dancing of the famous pieces, the whole theater was not captivated enough to reach the stars."

Peace and prosperity came to Carthage and Africa Province. Eventually Roman security forces began to be drawn from the local population. Here the Romans governed well enough that the Province became integrated into the economy and culture of the Empire, attracting immigrants. Its cosmopolitan, Latinizing, and diverse population enjoyed a reputation for its high standard of living. Carthage emerged near the top of major Imperial cities, behind only Alexandria

Alexandria

Alexandria is the second-largest city of Egypt, with a population of 4.1 million, extending about along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea in the north central part of the country; it is also the largest city lying directly on the Mediterranean coast. It is Egypt's largest seaport, serving...

and Rome

Rome

Rome is the capital of Italy and the country's largest and most populated city and comune, with over 2.7 million residents in . The city is located in the central-western portion of the Italian Peninsula, on the Tiber River within the Lazio region of Italy.Rome's history spans two and a half...

.

Agricultural lands

Rome "held fast" the lands of Carthage after its fall (146 BCE), yet did so initially out of a "perversity" engendered by war, i.e., less to develop the harvest and benefit themselves, than to keep others off. Many Punic survivors of the defeated city, including owners of olive groves, vineyards, and farms, had "fled into the hinterland".Public lands (ager publicus) passed to Rome by right of conquest

Right of conquest

The right of conquest is the right of a conqueror to territory taken by force of arms. It was traditionally a principle of international law which has in modern times gradually given way until its proscription after the Second World War when the crime of war of aggression was first codified in the...

, and many privately held lands also, those ruined or differently abandoned, or that had unpaid taxes, or otherwise. Some rural lands good for agriculture, which had been used up to then only seasonally by Berber pastoralists, were also taken and distributed for planting. Accordingly many nomads (and small farmers, too) "were reduced to abject poverty or driven into the steppes and desert." Tacfarinas

Tacfarinas

Tacfarinas was a Numidian deserter from the Roman army who led his own Musulamii tribe and a loose and changing coalition of other Ancient Libyan tribes in a war against the Romans in North Africa during the rule of emperor Tiberius .Although Tacfarinas' personal motivation is unknown, it is...

led a sustained Berber insurgency

Berber kings of Roman-era Tunisia

During the Second Punic War Rome entered into alliance with Masinissa, son of a Berber king. Masinissa had been driven out of his ancestral realm by a Carthage-backed Berber rival. At the defeat of Carthage Masinissa , a "friend of the Roman people", became King of Numidia for fifty years...

(17-24) against Rome; yet these rural tribal forces eventually met defeat. Thereafter the expansion of farming operations over the provincial lands did produce a higher yield. Yet Rome "never succeeded in keeping the nomads of the south and west permanently in check."

Great estates were formed by investors or the politically favored, or by emperors out of confiscated lands. Called latifundia

Latifundia

Latifundia are pieces of property covering very large land areas. The latifundia of Roman history were great landed estates, specializing in agriculture destined for export: grain, olive oil, or wine...

, their farming operations were leased out to coloni

Colonus (person)

A colonus was a type of Roman peasant farmer, a serf. This designation was carried into the Medieval period for much of Europe.Coloni worked on large Roman estates called "latifundia" and could never leave. Latifundia raised sheep and other types of cattle...

often from Italia, who settled around the owner's 'main house'--thus forming a small agrarian town. The land was divided into "squares measuring 710 meters across". Many small farms were thus held by incoming Roman citizens or army veterans (the pagi

Pagi

Pagoi or Pagi is a village in the NW corner of Corfu Island in Greece. It is a community of the municipal unit Agios Georgios.-Agios Georgios Pagon :...

), as well as by the prior owners, Punic and Berber. The quality and extend of large villa

Roman villa

A Roman villa is a villa that was built or lived in during the Roman republic and the Roman Empire. A villa was originally a Roman country house built for the upper class...

s with comfort amenities, and other farm housing, found throughout Africa Province dating to this era, evidence the wealth generated by agriculture. Working the land for its fruits was very rewarding.

Rich agricultural lands led the province to great prosperity. New hydraulic works increased the extend and intensity of the irrigation

Irrigation

Irrigation may be defined as the science of artificial application of water to the land or soil. It is used to assist in the growing of agricultural crops, maintenance of landscapes, and revegetation of disturbed soils in dry areas and during periods of inadequate rainfall...

. Olives and grapes had for long been popular products commonly praised; however, the vineyards and orchards had been devastated during the last Punic war; also they were intentionally left to ruin because their produce competed with that of Roman Italia. Instead Africa Province acquired fame as the source of large quantities of fine wheat, widely exported--though chiefly to Rome. The ancient writers Strabo

Strabo

Strabo, also written Strabon was a Greek historian, geographer and philosopher.-Life:Strabo was born to an affluent family from Amaseia in Pontus , a city which he said was situated the approximate equivalent of 75 km from the Black Sea...

(64-c. AD 21), Pliny

Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus , better known as Pliny the Elder, was a Roman author, naturalist, and natural philosopher, as well as naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and personal friend of the emperor Vespasian...

(AD 23-c.79), and Josephus

Josephus

Titus Flavius Josephus , also called Joseph ben Matityahu , was a 1st-century Romano-Jewish historian and hagiographer of priestly and royal ancestry who recorded Jewish history, with special emphasis on the 1st century AD and the First Jewish–Roman War, which resulted in the Destruction of...

(37-c.95) praised the quality of African wheat. The Baradas river valley was acclaimed as productive as the Nile. Later, when Egypt began to supplant Africa Province as the supplier of wheat to Rome, the grape and the olive began reappearing again in the fields of the province, toward the end of the 1st century. St. Augustine

St. Augustine

-People:* Augustine of Hippo or Augustine of Hippo , father of the Latin church* Augustine of Canterbury , first Archbishop of Canterbury* Augustine Webster, an English Catholic martyr.-Places:*St. Augustine, Florida, United States...

(354-430) wrote that in Africa lamps fueled by olive oil burned well throughout the night, throwing light over the neighborhoods.

Evidence, from artifacts and the often large mosaics of great villas, indicates that one favorite sport of the agrarian elite was the hunt

Hunting

Hunting is the practice of pursuing any living thing, usually wildlife, for food, recreation, or trade. In present-day use, the term refers to lawful hunting, as distinguished from poaching, which is the killing, trapping or capture of the hunted species contrary to applicable law...

. Depicted are well-dressed sportsmen (in embroidered riding tunics with striped sleeves). Mounted on horseback they go cross-country in pursuit of illustrated game--here perhaps a jackal

Jackal

Although the word jackal has been historically used to refer to many small- to medium-sized species of the wolf genus of mammals, Canis, today it most properly and commonly refers to three species: the black-backed jackal and the side-striped jackal of sub-Saharan Africa, and the golden jackal of...

. Various wild birds are also shown as desired prey, to be gotten with traps. On the floor of a patio, a greyhound appears to be chasing a hare across the surface of its mosaic.

Commerce and trade

Pottery

Pottery is the material from which the potteryware is made, of which major types include earthenware, stoneware and porcelain. The place where such wares are made is also called a pottery . Pottery also refers to the art or craft of the potter or the manufacture of pottery...

, skills developed and practiced for many centuries under the prior Phoenician-derived, urban culture, continued as an important industry, Both oil lamps and amphorae (containers with two handles) were produced in quantity. This pottery, of course, complemented the local production of olive oil, the amphorae being valuable not only as hard goods, but also useful for oil transportation locally and for export by ship. Numerous ancient oil presses have been found, producing from the harvested olive both oils for cooking and food, and oils for burning in lamps. Ceramics were also crafted into various statuettes of animals, humans, and gods, found in abundance in regional cemeteries of the period. Later, terra-cotta plaques showing biblical scenes were designed and made for the churches. Much of this industry was located in central Tunisia, e.g., in and around Thysdrus (modern El Djem

El Djem

Drifting sand is preserving the market city of Thysdrus and the refined suburban villas that once surrounded it. The amphiteatre occupies archaeologists' attention: no digging required...

), a drier area with less fertile agricultural lands, but ample in rich clay deposits.

The export of large amounts of wheat, and later of olive oils, and wines, required port facilities, indicated are (among others): Hippo Regius

Hippo Regius

Hippo Regius is the ancient name of the modern city of Annaba, in Algeria. Under this name, it was a major city in Roman Africa, hosting several early Christian councils, and was the home of the philosopher and theologian Augustine of Hippo...

(modern Annaba

Annaba

Annaba is a city in the northeastern corner of Algeria near the river Seybouse. It is located in Annaba Province. With a population of 257,359 , it is the fourth largest city in Algeria. It is a leading industrial centre in eastern Algeria....

), Hippo Diarrhytus (modern Bizerte

Bizerte

Bizerte or Benzert , is the capital city of Bizerte Governorate in Tunisia and the northernmost city in Africa. It has a population of 230,879 .-History:...

), Utica

Utica, Tunisia

Utica is an ancient city northwest of Carthage near the outflow of the Medjerda River into the Mediterranean Sea, traditionally considered to be the first colony founded by the Phoenicians in North Africa...

, Carthage

Carthage

Carthage , implying it was a 'new Tyre') is a major urban centre that has existed for nearly 3,000 years on the Gulf of Tunis, developing from a Phoenician colony of the 1st millennium BC...

, Curubis

Curubis

Curubis is a genus of the spider family Salticidae .-Species:* Curubis annulata Simon, 1902 — Sri Lanka* Curubis erratica Simon, 1902 — Sri Lanka* Curubis sipeki Dobroruka, 2004 — India...

(north of modern Nabeul

Nabeul

Nabeul is a coastal town in northeastern Tunisia, on the south coast near to the Cap Bon peninsula. It is located at around and is the capital of the Nabeul Governorate...

), Missis, Hadrumentum, Gummi and Sullectum (both near modern Mahdia

Mahdia

Mahdia is a provincial centre north of Sfax. It is important for the associated fish-processing industry, as well as weaving. It is the capital of Mahdia Governorate.- History :...

), Gightis (near Djerba

Djerba

Djerba , also transliterated as Jerba or Jarbah, is, at 514 km², the largest island of North Africa, located in the Gulf of Gabes, off the coast of Tunisia.-Description:...

isle), and Sabratha

Sabratha

Sabratha, Sabratah or Siburata , in the Zawiya District in the northwestern corner of modern Libya, was the westernmost of the "three cities" of Tripolis. From 2001 to 2007 it was the capital of the former Sabratha wa Sorman District. It lies on the Mediterranean coast about west of Tripoli...

(near modern Tarabulus [Tripoli]). Marble and wood was shipped out of Thabraca (modern Tabarka

Tabarka

Tabarka is a coastal town located in north-western Tunisia, at about , close to the border with Algeria. It has been famous for its coral fishing, the Coral Festival of underwater photography and the annual jazz festival. Tabarka's history is a colorful mosaic of Phoenician, Roman, Arabic and...

). Ancient associations engaged in export shipping might form navicularii, collectively responsible for the commodities yet granted state privileges. Inland trade was carried on Roman roads, built both for the Roman legion

Roman legion

A Roman legion normally indicates the basic ancient Roman army unit recruited specifically from Roman citizens. The organization of legions varied greatly over time but they were typically composed of perhaps 5,000 soldiers, divided into maniples and later into "cohorts"...

s and for commercial and private use. A major road led from Carthage southwest to Theveste (modern Tébessa

Tébessa

Tébessa is the capital city of Tébessa Province, Algeria, 20 kilometers west from the border with Tunisia. Nearby is also a phosphate mine. The city is famous for the traditional Algerian carpets in the region, and is home to over 161,440 people.-History:...

) in the mountains; from there a road led southeast to Tacapes (modern Gabès

Gabès

Gabès , also spelt Cabès, Cabes, Kabes, Gabbs and Gaps, the ancient Tacape, is the capital city of the Gabès Governorate, a province of Tunisia. It lies on the coast of the Gulf of Gabès. With a population of 116,323 it is the 6th largest Tunisian city.-History:Strabo refers to Tacape as an...

) on the coast. Roads also followed the coastline. Buildings were erected occasionally along such highways for the convenience of traders with goods and other travelers.

Other products of Africa Province were shipped out. An ancient industry at Carthage involved cooking up a Mediterranean condiment

Condiment

A condiment is an edible substance, such as sauce or seasoning, added to food to impart a particular flavor, enhance its flavor, or in some cultures, to complement the dish. Many condiments are available packaged in single-serving sachets , like mustard or ketchup, particularly when supplied with...

called garum, a fish sauce made with herbs, an item of durable popularity. Rugs and wool clothing were fabricated, and leather goods. The royal purple dye, murex

Murex

Murex is a genus of medium to large sized predatory tropical sea snails. These are carnivorous marine gastropod molluscs in the family Muricidae, commonly calle "murexes" or "rock snails"...

, first discovered and made famous by the Phoenicians, was locally produced. Marble and wood, as well as live mules, were also important export items.

Local trade and commerce was conducted at mundinae (fairs) in rural centers at set days of the week, much as it is today in souks. In villages and towns macella (provision markets) were established. In cities granted a charter the market was regulated by the municipal aediles (Roman market officials dating to the Roman Republic), who inspected the vendor's instruments for measuring and weighing. City trading was often done at the forum, or at stalls in covered areas, or at private shops.

Expeditions ventured south into the Sahara. Cornelius Balbus, Roman governor then at Utica, occupied in 19 BC. Gerama

Germa

Germa, known in ancient times as Garama, is an archaeological site in Libya and was the capital of the Garamantes.The Garamantes were a Berber people living in the Fezzan in the northeastern Sahara, originating from the Sahara's Tibesti region. Garamantian power climaxed during the 2nd and the 3rd...

, desert capital of the Garamantes in the Fezzan

Fezzan

Fezzan is a south western region of modern Libya. It is largely desert but broken by mountains, uplands, and dry river valleys in the north, where oases enable ancient towns and villages to survive deep in the otherwise inhospitable Sahara.-Name:...

(now west-central Libya

Libya

Libya is an African country in the Maghreb region of North Africa bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Sudan to the southeast, Chad and Niger to the south, and Algeria and Tunisia to the west....

). These Berber Garamantes

Garamantes

The Garamantes were a Saharan people who used an elaborate underground irrigation system, and founded a prosperous Berber kingdom in the Fezzan area of modern-day Libya, in the Sahara desert. They were a local power in the Sahara between 500 BC and 700 AD.There is little textual information about...

had long-term, though unpredictable, breakable, contacts with the Mediterranean. Although Roman trade and other contact with the Berber Fezzan continued, on and off, raid or trade, extensive commercial traffic across the Sahara, directly to the more productive and populous lands south of the harsh deserts, had not yet developed; nor would it for many centuries.

Salvius Julianus

A personal example illustrates the depth and scope of social integration in the Empire, as the imperial Roman culture reached out to people living far from the capital, to those born in a provincial city of no great importance. From 2nd-century Roman Africa came the lawyer Julian, who enjoyed an extraordinary career.Julian's life demonstrates the opportunities available to gifted provincials. Also it gives a view of Roman Law, whose workings crafted much of the structure holding together the various nationalities across the Empire. Apparently Julian came from a family of the Latin culture which had gradually become established in Africa Province, although his youth and early career are not recorded.

Salvius Julianus

Lucius Octavius Cornelius Publius Salvius Julianus Aemilianus , generally referred to as Salvius Julianus, or Julian the Jurist, or simply Julianus [Iulianus], was a well known and respected jurist, public official, and politician who served in the Roman imperial state...

(c.100-c.170), Roman jurist

Jurist

A jurist or jurisconsult is a professional who studies, develops, applies, or otherwise deals with the law. The term is widely used in American English, but in the United Kingdom and many Commonwealth countries it has only historical and specialist usage...

, Consul

Consul

Consul was the highest elected office of the Roman Republic and an appointive office under the Empire. The title was also used in other city states and also revived in modern states, notably in the First French Republic...

in 148, was a native of Hadrumetum

Hadrumetum

Hadrumetum was a Phoenician colony that pre-dated Carthage and stood on the site of modern-day Sousse, Tunisia.-Ancient history:...

(modern Sousse

Sousse

Sousse is a city in Tunisia. Located 140 km south of the capital Tunis, the city has 173,047 inhabitants . Sousse is in the central-east of the country, on the Gulf of Hammamet, which is a part of the Mediterranean Sea. The name may be of Berber origin: similar names are found in Libya and in...

, Tunisia) on the east coast of Africa province. He was a teacher; one of his students, Africanus

Sextus Caecilius Africanus

Sextus Caecilius Africanus was an ancient Roman jurist and a pupil of Salvius Julianus.Only one quote remains of his Epistulae of at least twenty books. Excerpts of his Quaestiones, a collection of legal cases in no particular order in nine books, are also reproduced in the Digests...

, was the last recorded head of the influential Sabinian

Masurius Sabinus

Masurius Sabinus, also Massurius, was a Roman jurist who lived in the time of Tiberius . Unlike most jurists of the time, he was not of senatorial rank and was admitted to the equestrian order only rather late in life, by virtue of his exceptional ability and imperial patronage...

school of Roman jurists. In Roman public life, Julian eventually came to hold several high positions during a long career. He acquired great contemporary respect as a jurist, and modernly is regarded as one of the best in Roman legal history

Roman law

Roman law is the legal system of ancient Rome, and the legal developments which occurred before the 7th century AD — when the Roman–Byzantine state adopted Greek as the language of government. The development of Roman law comprises more than a thousand years of jurisprudence — from the Twelve...

. "The task of his life consisted, in the first place, in the final consolidation of the edictal law; and, secondly, in the composition of his great Digest in ninety books."

Julian served the Empire at its top echelon, on the Counsilium

Consilium principis

The Consilium Principis was a council created by the first Roman Emperor, Augustus, in the latter years of his reign to control legislation in the deliberative institution of the Senate...

(imperial council) of three emperors: Hadrian

Hadrian

Hadrian , was Roman Emperor from 117 to 138. He is best known for building Hadrian's Wall, which marked the northern limit of Roman Britain. In Rome, he re-built the Pantheon and constructed the Temple of Venus and Roma. In addition to being emperor, Hadrian was a humanist and was philhellene in...

(r. 117-138), Antonius Pius (r. 138-161), and Marcus Aurelius (r.161-180). His life spanned a particularly beneficial era of Roman rule, when relative peace and prosperity reigned. Julian had been tribune

Tribune

Tribune was a title shared by elected officials in the Roman Republic. Tribunes had the power to convene the Plebeian Council and to act as its president, which also gave them the right to propose legislation before it. They were sacrosanct, in the sense that any assault on their person was...

; he "held all the important senatorial

Roman Senate

The Senate of the Roman Republic was a political institution in the ancient Roman Republic, however, it was not an elected body, but one whose members were appointed by the consuls, and later by the censors. After a magistrate served his term in office, it usually was followed with automatic...

offices from Quaestor

Quaestor

A Quaestor was a type of public official in the "Cursus honorum" system who supervised financial affairs. In the Roman Republic a quaestor was an elected official whereas, with the autocratic government of the Roman Empire, quaestors were simply appointed....

to Consul

Consul

Consul was the highest elected office of the Roman Republic and an appointive office under the Empire. The title was also used in other city states and also revived in modern states, notably in the First French Republic...

". Later, after his service on the emperor's Counsilium, he left for Germania Inferior

Germania Inferior

Germania Inferior was a Roman province located on the left bank of the Rhine, in today's Luxembourg, southern Netherlands, parts of Belgium, and North Rhine-Westphalia left of the Rhine....

to become its Roman governor

Roman governors of Germania Inferior

This is a list of Roman governors of Germania Inferior . Capital and largest city of Germania Inferior was Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium , modern-day Cologne....

. He served in the same capacity at Hispania Citerior

Hispania Citerior

During the Roman Republic, Hispania Citerior was a region of Hispania roughly occupying the northeastern coast and the Ebro Valley of what is now Spain. Hispania Ulterior was located west of Hispania Citerior—that is, farther away from Rome.-External links:*...

. At the end of his career, Julian became the Roman governor

Roman governor

A Roman governor was an official either elected or appointed to be the chief administrator of Roman law throughout one or more of the many provinces constituting the Roman Empire...

of his native Africa Province

Africa Province

The Roman province of Africa was established after the Romans defeated Carthage in the Third Punic War. It roughly comprised the territory of present-day northern Tunisia, and the small Mediterranean coast of modern-day western Libya along the Syrtis Minor...

. An inscription found near his native Hadrumetum (modern Sousse

Sousse

Sousse is a city in Tunisia. Located 140 km south of the capital Tunis, the city has 173,047 inhabitants . Sousse is in the central-east of the country, on the Gulf of Hammamet, which is a part of the Mediterranean Sea. The name may be of Berber origin: similar names are found in Libya and in...

, Tunisia) recounts his official life.

The emperor Hadrian appointed Julian, this native of a small city in Africa province, to revise the Praetor's Edict (thereafter called the Edictum perpetuum). This key legal document, then issued annually at Rome by the Praetor urbanus

Praetor

Praetor was a title granted by the government of Ancient Rome to men acting in one of two official capacities: the commander of an army, usually in the field, or the named commander before mustering the army; and an elected magistratus assigned varied duties...

, was at that time a most persuasive legal authority, pervasive in Roman Law

Roman law

Roman law is the legal system of ancient Rome, and the legal developments which occurred before the 7th century AD — when the Roman–Byzantine state adopted Greek as the language of government. The development of Roman law comprises more than a thousand years of jurisprudence — from the Twelve...

. "The Edict, that masterpiece of republican jurisprudence, became stabilized. ... [T]he famous jurist Julian settled the final form of the praetorian and aedilician

Aedile

Aedile was an office of the Roman Republic. Based in Rome, the aediles were responsible for maintenance of public buildings and regulation of public festivals. They also had powers to enforce public order. There were two pairs of aediles. Two aediles were from the ranks of plebeians and the other...

Edicts."

Later Julian authored his Digesta in 90 books; this work generally followed the sequence of subjects found in the praetorian edict, and presented a "comprehensive collection of responsa

Responsa

Responsa comprise a body of written decisions and rulings given by legal scholars in response to questions addressed to them.-In the Roman Empire:Roman law recognised responsa prudentium, i.e...

on real and hypothetical cases". The purpose of his Digesta was to expound the whole of Roman Law.

In the 6th century, this 2nd-century Digesta of Salvius Julianus was repeatedly excerpted, hundreds of times, by the compilers of the Pandectae, created under the authority of the Byzantine

Byzantine

Byzantine usually refers to the Roman Empire during the Middle Ages.Byzantine may also refer to:* A citizen of the Byzantine Empire, or native Greek during the Middle Ages...

emperor Justinian I

Justinian I

Justinian I ; , ; 483– 13 or 14 November 565), commonly known as Justinian the Great, was Byzantine Emperor from 527 to 565. During his reign, Justinian sought to revive the Empire's greatness and reconquer the lost western half of the classical Roman Empire.One of the most important figures of...

(r. 527-265). This Pandect (also known as the Digest, part of the Corpus Juris Civilis

Corpus Juris Civilis

The Corpus Juris Civilis is the modern name for a collection of fundamental works in jurisprudence, issued from 529 to 534 by order of Justinian I, Eastern Roman Emperor...

) was a compendium of juristic experience and learning. "It has been thought that Justinian's compilers used [Julian's Digesta] as the basis of their scheme: in any case nearly 500 passages are quoted from it." The Pandect, in addition to its official rôle as part of the controlling law of the eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire, also became a principal source for the medieval study of Roman Law in western Europe.

About Julian's personal life little is known. Apparently he became related in some way (probably through his daughter) to the family of the Roman emperor Didius Julianus

Didius Julianus

Didius Julianus , was Roman Emperor for three months during the year 193. He ascended the throne after buying it from the Praetorian Guard, who had assassinated his predecessor Pertinax. This led to the Roman Civil War of 193–197...

, who reigned during the year 93.

Julian died probably in Africa province, as its Roman governor or shortly thereafter. This was during the reign of the philosophical emperor Marcus Aurelius (r.161-180), who described Julian in a rescript

Rescript

A rescript is a document that is issued not on the initiative of the author, but in response to a specific demand made by its addressee...

as amicus noster (Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

: "our friend"). "His fame did not lessen as time went on, for later Emperors speak of him in the most lauditory terms. ... Justinian

Justinian I

Justinian I ; , ; 483– 13 or 14 November 565), commonly known as Justinian the Great, was Byzantine Emperor from 527 to 565. During his reign, Justinian sought to revive the Empire's greatness and reconquer the lost western half of the classical Roman Empire.One of the most important figures of...

[6th century] speaks of him as the most illustrious of the jurists." "With Iulianus, the Roman jurisprudence

Jurisprudence

Jurisprudence is the theory and philosophy of law. Scholars of jurisprudence, or legal theorists , hope to obtain a deeper understanding of the nature of law, of legal reasoning, legal systems and of legal institutions...

reached its apogee."

Assimilation

Roman army

The Roman army is the generic term for the terrestrial armed forces deployed by the kingdom of Rome , the Roman Republic , the Roman Empire and its successor, the Byzantine empire...

in early retirement who settled in Africa on farming plots promised for their military service. A sizable Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

speaking population developed that was multinational in background; they shared the region with those speaking Punic and Berber languages. Usually the business of the empire was conducted in Latin, so that a markedly bi- or tri-lingual situation developed. Imperial security forces began to be drawn from the local population, including the Berbers. The Romans apparently sounded the right notes, which facilitated general acceptance of their rule.

"What made the Berbers accept the Roman way of life all the more readily was that the Romans, though a colonizing people who captured their lands by the might of their arms, did not display any racial exclusiveness and were remarkably tolerant of Berber religious cults, be they indigenous or grafted from the Carthaginians. However, the Roman territory in Africa was unevenly penetrated by Roman culture. Pockets of non-Romanized Berbers continued to exist throughout the Roman period, even in such areas as eastern Tunisia and Numidia."

That the majority of the Berbers adjusted to the Roman world, of course, does not signify their full acceptance. Often the presence of cosmopolitan cultural symbols coexisted with the traditional local customs and beliefs, i.e., the Roman did not supplant the Berber, but merely augmented the prior Berber culture, often the Roman being on a more transient level of adherence.

Lucius Apuleius

Lucius ApuleiusApuleius

Apuleius was a Latin prose writer. He was a Berber, from Madaurus . He studied Platonist philosophy in Athens; travelled to Italy, Asia Minor and Egypt; and was an initiate in several cults or mysteries. The most famous incident in his life was when he was accused of using magic to gain the...

(c.125-c.185), a Berber author of Africa Province, wrote using an innovative Latin style. Although often called Lucius Apuleius, only the name Apuleius is certain. He managed to thrive in several Latin-speaking communities of Carthage: the professional, the literary, and the pagan religious. A self-described full Berber, "half Numidian, half Gaetulia

Gaetulia

Gaetuli was the Romanised name of an ancient Berber tribe inhabiting Getulia, covering the desert region south of the Atlas Mountains, bordering the Sahara. Other sources place Getulia in pre-Roman times along the Mediterranean coasts of what is now Algeria and Tunisia, and north of the Atlas...

n", his origins lay on the upper Bagradas (modern Medjerda) river valley, in Madaura (modern M'Daourouch). In the town lived many retired Roman soldiers, often themselves natives of Africa. His father was a provincial magistrate, of the upper ordo class. When he was still young his father died, leaving a relative fortune to him and his brother.

His studies began at Carthage, and continued during years spent at Athens (philosophy) and at Rome (oratory), where he evidently served as a legal advocate. Comparing learning to fine wine but with an opposite effect, Apuleius wrote, "The more you drink and the stronger the draught, the better it is for the good of your soul." He also traveled to Asia Minor and Egypt. While returning to Carthage he fell seriously ill in Oea (an ancient coastal city near modern Tripoli), where he convalesced at the family home of an old student friend Pontianus. Eventually Apuleius married Prudentilla, the older, wealthy widow of the house, and mother of Pontianus. Evidently the marriage was good; Sidonius Apollinaris

Sidonius Apollinaris

Gaius Sollius Apollinaris Sidonius or Saint Sidonius Apollinaris was a poet, diplomat, and bishop. Sidonius is "the single most important surviving author from fifth-century Gaul" according to Eric Goldberg...

called Prudentilla one of those "noble women [who] held the lamp while their husbands read and meditated." Yet debauched and greedy in-laws (this characterization by Apuleius) wantonly claimed he had murdered Pontianus; they did, however, prosecute Apuleius for using nefarius magic to gain his new wife's affections. At the trial in nearby Sabratha

Sabratha

Sabratha, Sabratah or Siburata , in the Zawiya District in the northwestern corner of modern Libya, was the westernmost of the "three cities" of Tripolis. From 2001 to 2007 it was the capital of the former Sabratha wa Sorman District. It lies on the Mediterranean coast about west of Tripoli...

the Roman proconsul Claudius Maximus

Claudius Maximus

Claudius Maximus was a Stoic philosopher and a teacher of Marcus Aurelius.Marcus describes him as the perfect sage:From Maximus I learned self-government, and not to be led aside by anything; and cheerfulness in all circumstances, as well as in illness; and a just admixture in the moral character...

presided. Apuleius, then in his thirties, crafted a trial speech in his own defense, which in written form makes his Apology; apparently he was acquitted. A well-regarded modern critic characterizes his oratory, as it appears in his Apologia:

"We feel throughout the speech a keen pleasure in the display of superior sophistication and culture. We can see how he might well have dazzled the rich citizens of Oea for awhile and how he would also soon arouse deep suspicions and hostilities. Particularly one feels that he is of a divided mind about the accusation of wizardry. He deals with the actual charges in tones of amused contempt, yet seems not averse from being considered one of the great magicians of the world."

Apuleius and Prudentilla then moved to Carthage. There he continued his Latin writing, dealing with Greek philosophy, with oratory and rhetoric, and also fiction and poetry. Attracting a significant following, several civic statues were erected in his honor. He showed brilliance speaking in public as a "popular philosopher or 'sophist', characteristic of the second century A.D., which ranked such talkers higher than poets and rewarded them greatly with esteem and cash... ." "He was novelist and 'sophist', lawyer and lecturer, poet and initiate. It is not surprising that he was accused of magic--".

The Golden Ass

The Metamorphoses of Apuleius, which St. Augustine referred to as The Golden Ass , is the only Latin novel to survive in its entirety....

, by moderns commonly called The Golden Ass. A well-known work, Apuleius here created an urbane, inventive, vulgar, extravagant, mythic story, a sort of fable

Fable

A fable is a succinct fictional story, in prose or verse, that features animals, mythical creatures, plants, inanimate objects or forces of nature which are anthropomorphized , and that illustrates a moral lesson , which may at the end be expressed explicitly in a pithy maxim.A fable differs from...

of the ancient world. The plot unfolds in Greece where the hero, while experimenting with the ointment of a sorceress, is changed not into an owl (as intended) but into a donkey. Thereafter his ability to speak leaves him, but he remains able to understand the talk of others. In a famous digression (one of many), the celebrated folktale of Cupid and Psyche

Cupid and Psyche

Cupid and Psyche , is a legend that first appeared as a digressionary story told by an old woman in Lucius Apuleius' novel, The Golden Ass, written in the 2nd century CE. Apuleius likely used an earlier tale as the basis for his story, modifying it to suit the thematic needs of his novel.It has...

is artfully told by a crone. Therein Cupid

Cupid

In Roman mythology, Cupid is the god of desire, affection and erotic love. He is the son of the goddess Venus and the god Mars. His Greek counterpart is Eros...

, son of the Roman goddess Venus

Venus (mythology)

Venus is a Roman goddess principally associated with love, beauty, sex,sexual seduction and fertility, who played a key role in many Roman religious festivals and myths...

, falls in love with a beautiful but mortal girl, who because of her loveliness has been jinxed by Cupid's mother; the god Jupiter

Jupiter (mythology)

In ancient Roman religion and myth, Jupiter or Jove is the king of the gods, and the god of the sky and thunder. He is the equivalent of Zeus in the Greek pantheon....

resolves their dilemma. The hero as donkey listens as the story is told. After such and many adventures, in which he finds comedy, cruelty, onerous work as a beast-of-burden, circus-like exhibition, danger, and a love companion, the hero finally manages to regain his human form—by eating roses. Isis

Isis

Isis or in original more likely Aset is a goddess in Ancient Egyptian religious beliefs, whose worship spread throughout the Greco-Roman world. She was worshipped as the ideal mother and wife as well as the matron of nature and magic...

, the Egyptian goddess, in answer to his petitions, directs her priests during a procession to feed the flowers to him. "At once my ugly and beastly form left me. My rugged hair thinned and fell; my huge belly sank in; my hooves separated out into fingers and toes; my hands ceased to be feet... and my tail... simply disappeared." In the last few pages, the hero continues to follow the procession, entering by initiations into the religious service of Isis and Osiris

Osiris

Osiris is an Egyptian god, usually identified as the god of the afterlife, the underworld and the dead. He is classically depicted as a green-skinned man with a pharaoh's beard, partially mummy-wrapped at the legs, wearing a distinctive crown with two large ostrich feathers at either side, and...

of the Egyptian pantheon

Egyptian pantheon

The Egyptian pantheon consisted of the many gods worshipped by the Ancient Egyptians. A number of major deities are addressed as the creator of the cosmos. These include Atum, Ra, Amun and Ptah amongst others, as well as composite forms of these gods such as Amun-Ra. This was not seen as...

.

Metamorphoses is compared by Jack Lindsay

Jack Lindsay

Robert Leeson Jack Lindsay was an Australian-born writer, who from 1926 lived in the United Kingdom, initially in Essex. He was born in Melbourne, but spent his formative years in Brisbane...

to two other ancient works of fiction: Satyricon

Satyricon

Satyricon is a Latin work of fiction in a mixture of prose and poetry. It is believed to have been written by Gaius Petronius, though the manuscript tradition identifies the author as a certain Titus Petronius...

by Petronius

Petronius

Gaius Petronius Arbiter was a Roman courtier during the reign of Nero. He is generally believed to be the author of the Satyricon, a satirical novel believed to have been written during the Neronian age.-Life:...

and Daphne and Chloe

Daphne and Chloe

Daphne and Chloe is a painting by award-winning Filipino painter and hero Juan Luna. Created in the academic-style by the artist after being exposed to the works of art of Renaissance master painters in Rome, Daphne and Chloe won Luna a silver palette from the Liceo Artistico de Manila ....

by Longus

Longus

Longus, sometimes Longos , was the author of an ancient Greek novel or romance, Daphnis and Chloe. Very little is known of his life, and it is assumed that he lived on the isle of Lesbos during the 2nd century AD...

. He also notes that at the end of Metamorphoses "we find the only full testimony of religious experience left by an adherent of ancient paganism... devotees of mystery-cults, of the cults of the savior-gods... ." H. J. Rose

H. J. Rose

Herbert Jennings Rose is remembered as the author of A Handbook of Greek Mythology, originally published in 1928, which for many years became the standard student reference book on the subject, reaching a sixth edition by 1958...

comments that "the story is meant to convey a religious lesson: Isis saves [the hero] from the vanities of this world, which make men of no more worth than beasts, to a life of blissful service, here and hereafter." About Apuleius's novel Michael Grant

Michael Grant

Michael Grant may refer to:* Michael Grant, 12th Baron de Longueuil , nobleman possessing the only French colonial title recognized by the King or Queen of Canada* Michael Grant , American football player...

suggests that "the ecstatic belief in mystery religions [here, Isis] marked, in some sense, the transition between state-paganism and Christiantiy." Yet later he notes that "the Christian Fathers, after long discussion, were disposed to let Apuleius fall from favour."

St. Augustine mentions his fellow African Apuleius in his The City of God. When Apuleius lived was an age, Augustine elsewhere decries, of damnabilis curiositas. In discussing Socrates

Socrates

Socrates was a classical Greek Athenian philosopher. Credited as one of the founders of Western philosophy, he is an enigmatic figure known chiefly through the accounts of later classical writers, especially the writings of his students Plato and Xenophon, and the plays of his contemporary ...

and Plato

Plato

Plato , was a Classical Greek philosopher, mathematician, student of Socrates, writer of philosophical dialogues, and founder of the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. Along with his mentor, Socrates, and his student, Aristotle, Plato helped to lay the...

on 'the souls of gods, airy spirits, and humans,' Augustine refers to "a Platonist of Madaura", Apuleius, and to his work De Deo Socratis [The God of Socrates]. Augustine, holding the view that the world was under the lordship of the devil, challenged the pagans their reverence for particular gods. Referring to what he found as moral confusion or worse in stories of these gods, and their airy spirits, Augustine suggests a better title for Apuleius' book: "he should have called it De Daemone Socratis, of his devil."

That Apuleius worked magic was widely accepted by many of his contemporaries; he was sometimes compared to Apollonius of Tyana

Apollonius of Tyana

Apollonius of Tyana was a Greek Neopythagorean philosopher from the town of Tyana in the Roman province of Cappadocia in Asia Minor. Little is certainly known about him...

(died c.97), a magician (whom some pagans later claimed as a miracle-worker, equal to Christ). Apuleius himself was drawn to mystery religions, particularly the cult of Isis

Isis

Isis or in original more likely Aset is a goddess in Ancient Egyptian religious beliefs, whose worship spread throughout the Greco-Roman world. She was worshipped as the ideal mother and wife as well as the matron of nature and magic...

. "He held the office of sacerdos prouinciae at Carthage." "In any event Apuleius became for the Christians a most controversial figure."

Apuleius used a Latin

Latin literature

Latin literature includes the essays, histories, poems, plays, and other writings of the ancient Romans. In many ways, it seems to be a continuation of Greek literature, using many of the same forms...

style that registered as elocutio novella ("new speech") to his literary contemporaries. This style expressed the every day language used by the educated, along with naturally embedded archaisms. It worked to transform the more formal, classical grammar once favored since Cicero

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero , was a Roman philosopher, statesman, lawyer, political theorist, and Roman constitutionalist. He came from a wealthy municipal family of the equestrian order, and is widely considered one of Rome's greatest orators and prose stylists.He introduced the Romans to the chief...

(106-43 BC). To rhetoric

Rhetoric

Rhetoric is the art of discourse, an art that aims to improve the facility of speakers or writers who attempt to inform, persuade, or motivate particular audiences in specific situations. As a subject of formal study and a productive civic practice, rhetoric has played a central role in the Western...

ians perhaps it would be asiatic as opposed to attic style. Also new speech pointed toward the future development of modern Romance languages

Romance languages

The Romance languages are a branch of the Indo-European language family, more precisely of the Italic languages subfamily, comprising all the languages that descend from Vulgar Latin, the language of ancient Rome...

. Some suggest a style source in Africa, "owing its rich colours to the Punic element... his Madauran origins"; yet, while calling Africa informative, Lindsay declares it insufficient:

"[W]e cannot reduce his style as a whole to African influences. His mixture of ornate invention and rhetorical ingenuity with archaic and colloquial forms marks him rather as a man of his epoch, in which the classical heritage is being transformed by a welter of new forces."

Phrases like "oppido formido" [I greatly fear] litter his pages. Apuleius' "prose is a mosaic of internal rhymes and assonances. Alliteration is frequent." One who involutarilly remains alive after a loved one's death is "invita remansit in vita". "This may seem an over-nice analysis of a verbal trick; but Apuleius' creative energy resides precisely in this sort of thing--".

Social strata

The success of the Berber Apuleius, however, may be regarded as more an exception than the rule. Evidently many native Berbers adopted to the Mediterranean-wide influences operating in the province, eventually intermarrying, or otherwise entering the front ranks as notables. Yet the majority did not. There remained a social hierarchy consisting of the RomanizedRomanization (cultural)

Romanization or latinization indicate different historical processes, such as acculturation, integration and assimilation of newly incorporated and peripheral populations by the Roman Republic and the later Roman Empire...

, the partly assimilated

Cultural assimilation

Cultural assimilation is a socio-political response to demographic multi-ethnicity that supports or promotes the assimilation of ethnic minorities into the dominant culture. The term assimilation is often used with regard to immigrants and various ethnic groups who have settled in a new land. New...

, and the unassimilated (here were the many rural Berbers who did not know Latin). Yet in this schema considered among the "assimilated" might be very poor immigrants from other regions of the Empire. These imperial distinctions overlay the preexisting stratification of economic classes, e.g., there continued the practice of slavery, and there remained a coopted remnant of the wealthy Punic aristocracy.

The stepped-up pace and economic demands of a cosmopolitan urban life could impact very negatively on the welfare of the rural poor. Large estates (latifundia

Latifundia

Latifundia are pieces of property covering very large land areas. The latifundia of Roman history were great landed estates, specializing in agriculture destined for export: grain, olive oil, or wine...

) that produced cash crops for export often were managed for absentee owners and used slave labor. These 'agrobusiness' operations occupied lands previously tilled by small local farmers. At another social interface met the fundamental disagreement and social tensions between pastoral

Pastoralism

Pastoralism or pastoral farming is the branch of agriculture concerned with the raising of livestock. It is animal husbandry: the care, tending and use of animals such as camels, goats, cattle, yaks, llamas, and sheep. It may have a mobile aspect, moving the herds in search of fresh pasture and...

nomads, who had their herds to graze, and sedentary farmers. The best lands were usually appropriated for planting, often going to the better-connected socially, politically. These economic and status divisions would become manifest from time to time in various ways, e.g., the collateral revolt in 238, and the radical, quasi-ethnic edge to the Donatist

Donatist

Donatism was a Christian sect within the Roman province of Africa that flourished in the fourth and fifth centuries. It had its roots in the social pressures among the long-established Christian community of Roman North Africa , during the persecutions of Christians under Diocletian...

schism.

Emperors from Africa

Septimus Severus

Septimus Severus (145-211, r.193-211) was born of mixed Punic Ancestry in Lepcis Magna, TripolitaniaTripolitania

Tripolitania or Tripolitana is a historic region and former province of Libya.Tripolitania was a separate Italian colony from 1927 to 1934...

(now Libya), where he spent his youth. Although he was said to speak with a North African accent, he and his family were long members of the Roman cosmopolitan elite. His eighteen year reign was noted for frontier military campaigns. His wife Julia Domna

Julia Domna

Julia Domna was a member of the Severan dynasty of the Roman Empire. Empress and wife of Roman Emperor Lucius Septimius Severus and mother of Emperors Geta and Caracalla, Julia was among the most important women ever to exercise power behind the throne in the Roman Empire.- Family background...

of Emesa, Syria, was from a prominent family of priestly rulers there; as empress in Rome she cultivated a salon which may have included Ulpian

Ulpian

Gnaeus Domitius Annius Ulpianus , anglicized as Ulpian, was a Roman jurist of Tyrian ancestry.-Biography:The exact time and place of his birth are unknown, but the period of his literary activity was between AD 211 and 222...

of Tyre, the renowned jurist of Roman Law.

After Severus (whose reign was well regarded), his son Caracalla

Caracalla

Caracalla , was Roman emperor from 198 to 217. The eldest son of Septimius Severus, he ruled jointly with his younger brother Geta until he murdered the latter in 211...

(r.211-217) became Emperor; Caracalla's edict of 212 granted citizenship to all free inhabitants of the Empire. Later, two grand nephews of Severus through his wife Julia Domna became Emperors: Elagabalus

Elagabalus

Elagabalus , also known as Heliogabalus, was Roman Emperor from 218 to 222. A member of the Severan Dynasty, he was Syrian on his mother's side, the son of Julia Soaemias and Sextus Varius Marcellus. Early in his youth he served as a priest of the god El-Gabal at his hometown, Emesa...

(r.218-222) who brought the black stone of Emesa to Rome; and Severus Alexander (r.222-235) born in Caesarea sub Libano (Lebanon). Though unrelated, the Emperor Macrinus

Macrinus

Macrinus , was Roman Emperor from 217 to 218. Macrinus was of "Moorish" descent and the first emperor to become so without membership in the senatorial class.-Background and career:...

(r.217-218) came from Iol Caesarea in Mauretania

Mauretania

Mauretania is a part of the historical Ancient Libyan land in North Africa. It corresponds to present day Morocco and a part of western Algeria...

(modern Sharshal

Cherchell

Cherchell is a seaport town in the Province of Tipaza, Algeria, 55 miles west of Algiers. It is the district seat of Cherchell District. As of 1998, it had a population of 24,400.-Ancient history:...

, Algeria).

The Gordiani dynasty

There were also Roman Emperors from the Province of AfricaAfrica Province

The Roman province of Africa was established after the Romans defeated Carthage in the Third Punic War. It roughly comprised the territory of present-day northern Tunisia, and the small Mediterranean coast of modern-day western Libya along the Syrtis Minor...

. In 238 local proprietors rose in revolt, arming their clients and agricultural tenants who entered Thysdrus (modern El Djem) where they killed their target, a rapacious official and his bodyguards. In open revolt, they then proclaimed as co-emperors the aged Governor of the Province of Africa, Gordian I

Gordian I

Gordian I , was Roman Emperor for one month with his son Gordian II in 238, the Year of the Six Emperors. Caught up in a rebellion against the Emperor Maximinus Thrax, he was defeated by forces loyal to Maximinus before committing suicide.-Early life:...

(c.159-238), and his son, Gordian II

Gordian II

Gordian II , was Roman Emperor for one month with his father Gordian I in 238, the Year of the Six Emperors. Seeking to overthrow the Emperor Maximinus Thrax, he died in battle outside of Carthage.-Early career:...

(192-238). Gordian I had served at Rome in the Senate

Roman Senate

The Senate of the Roman Republic was a political institution in the ancient Roman Republic, however, it was not an elected body, but one whose members were appointed by the consuls, and later by the censors. After a magistrate served his term in office, it usually was followed with automatic...

and as Consul, and had been the Governor of various provinces. The very unpopular current Emperor Maximinus Thrax

Maximinus Thrax

Maximinus Thrax , also known as Maximinus I, was Roman Emperor from 235 to 238.Maximinus is described by several ancient sources, though none are contemporary except Herodian's Roman History. Maximinus was the first emperor never to set foot in Rome...

(who had succeeded the dynasty of Severus) was campaigning on the middle Danube. In Rome the Senate sided with the insurgents of Thysdrus. When the African revolt collapsed under an assault by local forces still loyal to the emperor, the Senate elected two of their number, Balbinus and Pupienus, as co-emperors. Then Maximus Thrax was killed by his disaffected soldiers. Eventually the grandson of Gordian I, Gordian III

Gordian III

Gordian III , was Roman Emperor from 238 to 244. Gordian was the son of Antonia Gordiana and an unnamed Roman Senator who died before 238. Antonia Gordiana was the daughter of Emperor Gordian I and younger sister of Emperor Gordian II. Very little is known on his early life before his acclamation...

(225-244), of the Province of Africa, became the Emperor of the Romans, 238-244. He died on the Persian frontier. His successor was Philip the Arab

Philip the Arab

Philip the Arab , also known as Philip or Philippus Arabs, was Roman Emperor from 244 to 249. He came from Syria, and rose to become a major figure in the Roman Empire. He achieved power after the death of Gordian III, quickly negotiating peace with the Sassanid Empire...

.

Felicitas & Perpetua

The Roman Imperial cultImperial cult (ancient Rome)

The Imperial cult of ancient Rome identified emperors and some members of their families with the divinely sanctioned authority of the Roman State...

was based on a general polytheism

Polytheism

Polytheism is the belief of multiple deities also usually assembled into a pantheon of gods and goddesses, along with their own mythologies and rituals....

that, by combining veneration for the paterfamilias and for the ancestor, developed a public celebration of the reigning Emperor

Roman Emperor

The Roman emperor was the ruler of the Roman State during the imperial period . The Romans had no single term for the office although at any given time, a given title was associated with the emperor...

as a father and divine leader. From time to time compulsory displays of loyalty

Loyalty

Loyalty is faithfulness or a devotion to a person, country, group, or cause There are many aspects to...

or patriotism

Patriotism

Patriotism is a devotion to one's country, excluding differences caused by the dependencies of the term's meaning upon context, geography and philosophy...

were required; those refusing the state cult might face a painful death. While polytheists might go along with little conviction, such a cult ran directly contrary to the dedicated Christian life, based on a confessed foundation of a single

Monotheism

Monotheism is the belief in the existence of one and only one god. Monotheism is characteristic of the Baha'i Faith, Christianity, Druzism, Hinduism, Islam, Judaism, Samaritanism, Sikhism and Zoroastrianism.While they profess the existence of only one deity, monotheistic religions may still...

triune deity.

In the Province of Africa lived two newly baptised Christians, both young women: Felicitas a servant

Domestic worker

A domestic worker is a man, woman or child who works within the employer's household. Domestic workers perform a variety of household services for an individual or a family, from providing care for children and elderly dependents to cleaning and household maintenance, known as housekeeping...

to Perpetua a noble

Nobility

Nobility is a social class which possesses more acknowledged privileges or eminence than members of most other classes in a society, membership therein typically being hereditary. The privileges associated with nobility may constitute substantial advantages over or relative to non-nobles, or may be...

, Felicitas pregnant and Perpetua a nursing

Breastfeeding

Breastfeeding is the feeding of an infant or young child with breast milk directly from female human breasts rather than from a baby bottle or other container. Babies have a sucking reflex that enables them to suck and swallow milk. It is recommended that mothers breastfeed for six months or...

mother. Together in the arena both were publicly torn apart by wild animals

Bestiarii

Among Ancient Romans, bestiarii were those who went into combat with beasts, or were exposed to them. It is conventional to distinguish two categories of bestiarii: the first were those condemned to death via the beasts and the second were those who faced them voluntarily, for pay or glory...

at Carthage in AD 203. Felicitas and Perpetua became celebrated among Christians as saints. An esteemed writing circulated, containing the reflections and visions of Perpetua (181-203), followed by a narrative of the martyrdom. These Acts were soon read aloud in Churches throughout the Empire.

Tertullian, Cyprian

Three significant theologians arose in the Province, all enjoying Berber ancestry: Tertulian, Cyprian, Augustine.Tertullian

Tertullian

Quintus Septimius Florens Tertullianus, anglicised as Tertullian , was a prolific early Christian author from Carthage in the Roman province of Africa. He is the first Christian author to produce an extensive corpus of Latin Christian literature. He also was a notable early Christian apologist and...

(160-230) was born, lived, and died at Carthage. An expert in Roman law, a convert and a priest, his Latin books on theology were once widely known, including his early understanding of the Trinity

Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity defines God as three divine persons : the Father, the Son , and the Holy Spirit. The three persons are distinct yet coexist in unity, and are co-equal, co-eternal and consubstantial . Put another way, the three persons of the Trinity are of one being...

. He later came to espouse an unforgiving puritanism, after Montanus, and so ended in heresy.

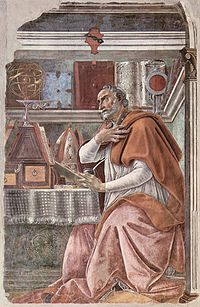

Augustine of Hippo

St. AugustineAugustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo , also known as Augustine, St. Augustine, St. Austin, St. Augoustinos, Blessed Augustine, or St. Augustine the Blessed, was Bishop of Hippo Regius . He was a Latin-speaking philosopher and theologian who lived in the Roman Africa Province...

(354-430), Bishop

Bishop (Catholic Church)

In the Catholic Church, a bishop is an ordained minister who holds the fullness of the sacrament of Holy Orders and is responsible for teaching the Catholic faith and ruling the Church....

of Hippo (modern Annaba

Annaba

Annaba is a city in the northeastern corner of Algeria near the river Seybouse. It is located in Annaba Province. With a population of 257,359 , it is the fourth largest city in Algeria. It is a leading industrial centre in eastern Algeria....

), was born at Tagaste in Numidia (modern Souk Ahras

Souk Ahras

Souk Ahras is a province in Algeria, named after its capital, Souk Ahras. It stands on the border between Algeria and Tunisia.- Geography :Souk Ahras is situated in the extreme north east of Algeria, it is 4360 km²....

). His mother St. Monica, a pillar of faith, evidently was of Berber heritage. Augutine himself did not speak a Berber language; his use of Punic

Punic language

The Punic language or Carthagian language is an extinct Semitic language formerly spoken in the Mediterranean region of North Africa and several Mediterranean islands, by people of the Punic culture.- Description :...

is unclear. At Carthage, Augustine received his higher education. Later, while professor of Rhetoric

Rhetoric