History of Maryland

Encyclopedia

Maryland

Maryland is a U.S. state located in the Mid Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware to its east...

included only Native Americans until Europeans, starting with John Cabot

John Cabot

John Cabot was an Italian navigator and explorer whose 1497 discovery of parts of North America is commonly held to have been the first European encounter with the continent of North America since the Norse Vikings in the eleventh century...

in 1498, began exploring the area. The first settlements came in 1634 when the English arrived in significant numbers and created a permanent colony. In 1776, during the American Revolution

American Revolution

The American Revolution was the political upheaval during the last half of the 18th century in which thirteen colonies in North America joined together to break free from the British Empire, combining to become the United States of America...

, Maryland became a state in the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

. Although it was a slave state

Slave state

In the United States of America prior to the American Civil War, a slave state was a U.S. state in which slavery was legal, whereas a free state was one in which slavery was either prohibited from its entry into the Union or eliminated over time...

where many planters had Confederate

Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America was a government set up from 1861 to 1865 by 11 Southern slave states of the United States of America that had declared their secession from the U.S...

sympathies, by 1860 nearly half the black population was already free, due mostly to manumission

Manumission

Manumission is the act of a slave owner freeing his or her slaves. In the United States before the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which abolished most slavery, this often happened upon the death of the owner, under conditions in his will.-Motivations:The...

s after the American Revolution

American Revolution

The American Revolution was the political upheaval during the last half of the 18th century in which thirteen colonies in North America joined together to break free from the British Empire, combining to become the United States of America...

. Maryland remained in the Union

Union (American Civil War)

During the American Civil War, the Union was a name used to refer to the federal government of the United States, which was supported by the twenty free states and five border slave states. It was opposed by 11 southern slave states that had declared a secession to join together to form the...

during the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

.

Although small in size, the state has distinct socio-political-economic regions, including the city of Baltimore

Baltimore

Baltimore is the largest independent city in the United States and the largest city and cultural center of the US state of Maryland. The city is located in central Maryland along the tidal portion of the Patapsco River, an arm of the Chesapeake Bay. Baltimore is sometimes referred to as Baltimore...

, Baltimore's suburbs, the Washington

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

suburbs, Western Maryland

Western Maryland

Western Maryland is the portion of the U.S. state of Maryland that consists of Frederick, Washington, Allegany, and Garrett counties. The region is bounded by the Mason-Dixon line to the north, Preston County, West Virginia to the west, and the Potomac River to the south. There is dispute over the...

, and the Eastern Shore

Eastern Shore of Maryland

The Eastern Shore of Maryland is a territorial part of the U.S. state of Maryland that lies predominately on the east side of the Chesapeake Bay and consists of nine counties. The origin of term Eastern Shore was derived to distinguish a territorial part of the State of Maryland from the Western...

. Maryland has a democratic-type of state government.

Pre-colonial history

It appears that the first humans to arrive in the area that would become Maryland appeared around the 10th millennium BCECommon Era

Common Era ,abbreviated as CE, is an alternative designation for the calendar era originally introduced by Dionysius Exiguus in the 6th century, traditionally identified with Anno Domini .Dates before the year 1 CE are indicated by the usage of BCE, short for Before the Common Era Common Era...

, about the time that the last ice age

Ice age

An ice age or, more precisely, glacial age, is a generic geological period of long-term reduction in the temperature of the Earth's surface and atmosphere, resulting in the presence or expansion of continental ice sheets, polar ice sheets and alpine glaciers...

ended. They were hunter-gatherer

Hunter-gatherer

A hunter-gatherer or forage society is one in which most or all food is obtained from wild plants and animals, in contrast to agricultural societies which rely mainly on domesticated species. Hunting and gathering was the ancestral subsistence mode of Homo, and all modern humans were...

s organized into semi-nomadic bands. They adapted as the region's environment changed, developing the spear for hunting as smaller animals, like deer

Deer

Deer are the ruminant mammals forming the family Cervidae. Species in the Cervidae family include white-tailed deer, elk, moose, red deer, reindeer, fallow deer, roe deer and chital. Male deer of all species and female reindeer grow and shed new antlers each year...

, became more prevalent and by about 1500 BCE. Oysters had become an important food resource in the region. With the increased variety of food sources, Native American

Native Americans in the United States

Native Americans in the United States are the indigenous peoples in North America within the boundaries of the present-day continental United States, parts of Alaska, and the island state of Hawaii. They are composed of numerous, distinct tribes, states, and ethnic groups, many of which survive as...

villages and settlements started appearing and their social structures increased in complexity. By about 1000 BCE pottery was being produced. With the eventual rise of agriculture

Agriculture

Agriculture is the cultivation of animals, plants, fungi and other life forms for food, fiber, and other products used to sustain life. Agriculture was the key implement in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that nurtured the...

more permanent Native-American villages were built. But even with the advent of farming, hunting and fishing were still important means of obtaining food. The bow and arrow were first used for hunting in the area around the year 800. They ate what they could kill, grow or catch in the rivers and other waterways.

By 1000 BCE, there were about 8,000 Native Americans, all Algonquian

Algonquian languages

The Algonquian languages also Algonkian) are a subfamily of Native American languages which includes most of the languages in the Algic language family. The name of the Algonquian language family is distinguished from the orthographically similar Algonquin dialect of the Ojibwe language, which is a...

-speaking, living in what is now the state, in 40 different villages. The following Piscataway tribes

Piscataway Indian Nation

The Piscataway Indian Nation and Tayac Territory is an unrecognized Native American tribe in Maryland that is related to the historic Piscataway tribe. At the time of European encounter, the Piscataway was one of the most populous and powerful Native polities of the Chesapeake Bay region, with a...

lived on the eastern bank of the Potomac

Potomac River

The Potomac River flows into the Chesapeake Bay, located along the mid-Atlantic coast of the United States. The river is approximately long, with a drainage area of about 14,700 square miles...

, from south to north: Yaocomico

Yaocomico

The Yaocomico, or Yaocomaco, were an Algonquian-speaking Native American group who lived along the north bank of the Potomac River near its confluence with the Chesapeake Bay in the 17th century...

es, Chopticans, Nanjemoys, Potopacs, Mattawoman

Mattawoman

The Mattawoman were a group of Native Americans living along the Western Shore of Maryland on the Chesapeake Bay at the time of English colonization. They lived along Mattawomen Creek in present-day Charles County, Maryland. They were also recorded in the early 17th century by explorer John...

s, Piscataways, Patuxents

Patuxent people

The Patuxent were one of the Native American tribes living along the western shore of the Chesapeake Bay. They spoke an Algonquian language and were loosely dominated by the Piscattaway.They were among the first people taught by Andrew White....

just south of what is now Washington, DC, Nacotchankes in current DC and on the western bank of the Potomac, and the Potomacs. The Shawnee

Shawnee

The Shawnee, Shaawanwaki, Shaawanooki and Shaawanowi lenaweeki, are an Algonquian-speaking people native to North America. Historically they inhabited the areas of Ohio, Virginia, West Virginia, Western Maryland, Kentucky, Indiana, and Pennsylvania...

lived near Oldtown in a site abandoned around 1731. On the Eastern Shore of the Chesapeake

Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay is the largest estuary in the United States. It lies off the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by Maryland and Virginia. The Chesapeake Bay's drainage basin covers in the District of Columbia and parts of six states: New York, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, and West...

, from south to north, there were the Nanticoke tribes: Annemessex, Assateagues, Wicomicoes

Wicocomico

The Wicocomico, Wiccocomoco, Wighcocomoco, or Wicomico are an Algonquian-speaking tribe who lived in Northumberland County, Virginia, at the end and just slightly north of the Little Wicomico River. They were a fringe group in Powhatan’s Confederacy.-History:The Wicocomico people were encountered...

, Nanticokes, Chicacone, and, on the north bank of the Choptank River

Choptank River

The Choptank River is a major tributary of the Chesapeake Bay on the Delmarva Peninsula. Running for , it rises in Kent County, Delaware, runs through Caroline County, Maryland and forms much of the border between Talbot County, Maryland on the north, and Caroline County and Dorchester County on...

, the Choptanks. The Tockwogh tribe

Tockwogh tribe

The Tockwogh were an Algonquian tribe first discovered by Captain John Smith's party after being informed about them by the Massawomekes . The name Tockwogh is a variation of tuckahoe, a water plant with bulbous roots used for food...

lived near the headwaters of the Chesapeake near what is now Delaware

Delaware

Delaware is a U.S. state located on the Atlantic Coast in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It is bordered to the south and west by Maryland, and to the north by Pennsylvania...

.

When Europeans began to settle in Maryland in the early 17th century, the main tribes included the Nanticoke on the Eastern Shore

Eastern Shore of Maryland

The Eastern Shore of Maryland is a territorial part of the U.S. state of Maryland that lies predominately on the east side of the Chesapeake Bay and consists of nine counties. The origin of term Eastern Shore was derived to distinguish a territorial part of the State of Maryland from the Western...

. Early exposure to new European diseases brought widespread fatalities to the Native Americans, as they had no immunity to them. Communities were disrupted by such losses.

Early European exploration

In 1498 the first European explorers sailed along the Eastern Shore, off present-day Worcester CountyWorcester County, Maryland

-2010:Whereas according to the 2010 U.S. Census Bureau:*82.0% White*13.6% Black*0.3% Native American*1.1% Asian*0.0% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander*1.7% Two or more races*1.3% Other races*3.2% Hispanic or Latino -2000:...

. In 1524 Giovanni da Verrazzano, sailing under the French flag, passed the mouth of Chesapeake Bay

Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay is the largest estuary in the United States. It lies off the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by Maryland and Virginia. The Chesapeake Bay's drainage basin covers in the District of Columbia and parts of six states: New York, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, and West...

. In 1608 John Smith entered the bay.

Colonial Maryland

George Calvert, 1st Baron Baltimore

Sir George Calvert, 1st Baron Baltimore, 8th Proprietary Governor of Newfoundland was an English politician and colonizer. He achieved domestic political success as a Member of Parliament and later Secretary of State under King James I...

, applied to Charles I

Charles I of England

Charles I was King of England, King of Scotland, and King of Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. Charles engaged in a struggle for power with the Parliament of England, attempting to obtain royal revenue whilst Parliament sought to curb his Royal prerogative which Charles...

for a royal charter

Royal Charter

A royal charter is a formal document issued by a monarch as letters patent, granting a right or power to an individual or a body corporate. They were, and are still, used to establish significant organizations such as cities or universities. Charters should be distinguished from warrants and...

for what was to become the Province of Maryland

Province of Maryland

The Province of Maryland was an English and later British colony in North America that existed from 1632 until 1776, when it joined the other twelve of the Thirteen Colonies in rebellion against Great Britain and became the U.S...

. After Calvert died in April 1632, the charter for "Maryland Colony" (in Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

Terra Mariae) was granted to his son, Cecilius Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore

Cecilius Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore

Cecilius Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore, 1st Proprietor and 1st Proprietary Governor of Maryland, 9th Proprietary Governor of Newfoundland , was an English peer who was the first proprietor of the Province of Maryland. He received the proprietorship after the death of his father, George Calvert, the...

, on June 20, 1632. Some historians viewed this as compensation for his father's having been stripped of his title of Secretary of State

Secretary of State

Secretary of State or State Secretary is a commonly used title for a senior or mid-level post in governments around the world. The role varies between countries, and in some cases there are multiple Secretaries of State in the Government....

in 1625 after announcing his Roman Catholicism.

The colony was named in honor of Queen Henrietta Maria

Henrietta Maria of France

Henrietta Maria of France ; was the Queen consort of England, Scotland and Ireland as the wife of King Charles I...

, the wife of King Charles I

Charles I of England

Charles I was King of England, King of Scotland, and King of Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. Charles engaged in a struggle for power with the Parliament of England, attempting to obtain royal revenue whilst Parliament sought to curb his Royal prerogative which Charles...

. The specific name given in the charter was phrased Terra Mariae, anglice, Maryland. The English name was preferred due to undesired associations of Mariae with the Spanish Jesuit Juan de Mariana

Juan de Mariana

Juan de Mariana, also known as Father Mariana , was a Spanish Jesuit priest, Scholastic, historian, and member of the Monarchomachs....

, linked to the Inquisition

Inquisition

The Inquisition, Inquisitio Haereticae Pravitatis , was the "fight against heretics" by several institutions within the justice-system of the Roman Catholic Church. It started in the 12th century, with the introduction of torture in the persecution of heresy...

.

As did other colonies, Maryland used the headright

Headright

A headright system is a legal grant of land to settlers who lived in Jamestown, Virginia. Headrights are most notable for their role in the expansion of the thirteen British colonies in North America; the Virginia Company of London gave headrights to settlers, and the Plymouth Company followed suit...

system to encourage people to bring in new settlers. Led by Leonard Calvert

Leonard Calvert

Leonard Calvert was the 1st Proprietary Governor of Maryland. He was the second son of George Calvert, 1st Baron Baltimore, the first proprietary of the Province of Maryland...

, Cecil Calvert's younger brother, the first settlers departed from Cowes

Cowes

Cowes is an English seaport town and civil parish on the Isle of Wight. Cowes is located on the west bank of the estuary of the River Medina facing the smaller town of East Cowes on the east Bank...

, on the Isle of Wight

Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight is a county and the largest island of England, located in the English Channel, on average about 2–4 miles off the south coast of the county of Hampshire, separated from the mainland by a strait called the Solent...

, on November 22, 1633 aboard two small ships, the Ark and the Dove. Their landing on March 25, 1634 at St. Clement's Island

St. Clement's Island

St. Clement's Island lies in the Potomac River near Colton's Point, Maryland, in the United States. The uninhabited island has been designated St. Clement's Island State Park....

in southern Maryland is commemorated by the state each year on that date as Maryland Day

Maryland Day

Maryland Day is a legal holiday in the U.S. state of Maryland. It is observed on the anniversary of the March 25, 1634, landing of settlers in the Province of Maryland. On this day settlers from The Ark and The Dove first stepped foot onto Maryland soil, at St. Clement's Island in the Potomac River...

. This was the site of the first Catholic mass in the Colonies, with Father Andrew White

Andrew White (missionary)

Andrew White, S.J. was an English Jesuit missionary who was involved in the founding of the Maryland colony. He was a chronicler of the early colony, and his writings are a primary source on the land, the Native Americans of the area, and the Jesuit mission in North America...

leading the service. The first group of colonists consisted of 17 gentlemen

Gentleman

The term gentleman , in its original and strict signification, denoted a well-educated man of good family and distinction, analogous to the Latin generosus...

and their wives, and about two hundred others, mostly indenture

Indenture

An indenture is a legal contract reflecting a debt or purchase obligation, specifically referring to two types of practices: in historical usage, an indentured servant status, and in modern usage, an instrument used for commercial debt or real estate transaction.-Historical usage:An indenture is a...

d servants who could work off their passage.

After purchasing land from the Yaocomico

Yaocomico

The Yaocomico, or Yaocomaco, were an Algonquian-speaking Native American group who lived along the north bank of the Potomac River near its confluence with the Chesapeake Bay in the 17th century...

Indians and establishing the town of St. Mary's

St. Mary's City, Maryland

St. Mary's City, in St. Mary's County, Maryland, is a small unincorporated community near the southernmost end of the state on the western shore of the Chesapeake Bay. It is located on the eastern shore of the St. Mary's River, a tributary of the Potomac. St. Mary's City is the fourth oldest...

, Leonard, per his brother's instructions, attempted to govern the country under feudalistic

Feudalism

Feudalism was a set of legal and military customs in medieval Europe that flourished between the 9th and 15th centuries, which, broadly defined, was a system for ordering society around relationships derived from the holding of land in exchange for service or labour.Although derived from the...

precepts. Meeting resistance, in February 1635, he summoned a colonial assembly

Deliberative assembly

A deliberative assembly is an organization comprising members who use parliamentary procedure to make decisions. In a speech to the electorate at Bristol in 1774, Edmund Burke described the English Parliament as a "deliberative assembly," and the expression became the basic term for a body of...

. In 1638, the Assembly forced him to govern according to the laws of England. The right to initiate legislation passed to the assembly.

In 1638, Calvert seized a trading post in Kent Island

Kent Island, Maryland

Kent Island is the largest island in the Chesapeake Bay, and a historic place in Maryland. To the east, a narrow channel known as the Kent Narrows barely separates the island from the Delmarva Peninsula, and on the other side, the island is separated from Sandy Point, an area near Annapolis, by...

established by the Virginian William Claiborne

William Claiborne

William Claiborne was an English pioneer, surveyor, and an early settler in Virginia and Maryland. Claiborne became a wealthy planter, a trader, and a major figure in the politics of the colony...

. In 1644, Claiborne led an uprising of Maryland Protestants. Calvert was forced to flee to Virginia

Virginia

The Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there...

, but he returned at the head of an armed force in 1646 and reasserted proprietarial

Proprietary colony

A proprietary colony was a colony in which one or more individuals, usually land owners, remaining subject to their parent state's sanctions, retained rights that are today regarded as the privilege of the state, and in all cases eventually became so....

rule.

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War , the American War of Independence, or simply the Revolutionary War, began as a war between the Kingdom of Great Britain and thirteen British colonies in North America, and ended in a global war between several European great powers.The war was the result of the...

.

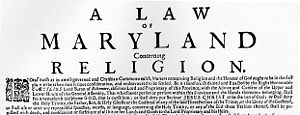

The Maryland Toleration Act

Maryland Toleration Act

The Maryland Toleration Act, also known as the Act Concerning Religion, was a law mandating religious tolerance for trinitarian Christians. Passed on April 21, 1649 by the assembly of the Maryland colony, it was the second law requiring religious tolerance in the British North American colonies and...

, issued in 1649, was one of the first laws that explicitly defined tolerance of varieties of Christianity

Christianity

Christianity is a monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus as presented in canonical gospels and other New Testament writings...

. It has been considered a precursor to the First Amendment

First Amendment to the United States Constitution

The First Amendment to the United States Constitution is part of the Bill of Rights. The amendment prohibits the making of any law respecting an establishment of religion, impeding the free exercise of religion, abridging the freedom of speech, infringing on the freedom of the press, interfering...

.

The founders designed the city plan of the colonial capital, St. Mary's City, to reflect their world view. At the center of the city was the home of the mayor of St. Mary's City. From that point, streets were laid out that created two triangles. Located at two points of the triangle extending to the west were the first Maryland state house and a jail. Extending to the north of the mayor's home, the remaining two points of the second triangle were defined by a Catholic church and a school. The design of the city was a literal separation of church and state that reinforced the importance of religious freedom.

The largest site of the original Maryland colony, St. Mary's City

St. Mary's City, Maryland

St. Mary's City, in St. Mary's County, Maryland, is a small unincorporated community near the southernmost end of the state on the western shore of the Chesapeake Bay. It is located on the eastern shore of the St. Mary's River, a tributary of the Potomac. St. Mary's City is the fourth oldest...

was the seat of colonial government until 1708. Because Anglicanism

Anglicanism

Anglicanism is a tradition within Christianity comprising churches with historical connections to the Church of England or similar beliefs, worship and church structures. The word Anglican originates in ecclesia anglicana, a medieval Latin phrase dating to at least 1246 that means the English...

had become the official religion in Virginia, a band of Puritan

Puritan

The Puritans were a significant grouping of English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries. Puritanism in this sense was founded by some Marian exiles from the clergy shortly after the accession of Elizabeth I of England in 1558, as an activist movement within the Church of England...

s in 1642 left for Maryland; they founded Providence (now called Annapolis

Annapolis, Maryland

Annapolis is the capital of the U.S. state of Maryland, as well as the county seat of Anne Arundel County. It had a population of 38,394 at the 2010 census and is situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east of Washington, D.C. Annapolis is...

).

In 1650, the Puritans revolted against the proprietary government. They set up a new government prohibiting both Catholicism and Anglicanism. In March 1655, the 2nd Lord Baltimore

Cecilius Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore

Cecilius Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore, 1st Proprietor and 1st Proprietary Governor of Maryland, 9th Proprietary Governor of Newfoundland , was an English peer who was the first proprietor of the Province of Maryland. He received the proprietorship after the death of his father, George Calvert, the...

sent an army under Governor William Stone to put down this revolt. Near Annapolis, his Roman Catholic army was decisively defeated by a Puritan

Puritan

The Puritans were a significant grouping of English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries. Puritanism in this sense was founded by some Marian exiles from the clergy shortly after the accession of Elizabeth I of England in 1558, as an activist movement within the Church of England...

army in the Battle of the Severn

Battle of the Severn

The Battle of the Severn was a skirmish fought on March 25, 1655, on the Severn River at Horn Point, across Spa Creek from Annapolis, Maryland, in what at that time was referred to as "Providence", in what is now the neighborhood of Eastport. Following the battle, Providence changed its name to...

. The Puritan revolt lasted until 1658, when the Calvert family regained control and re-enacted the Toleration Act.

The Puritan revolutionary government persecuted Maryland Catholics during its reign. Mobs burned down all the original Catholic churches of southern Maryland. In 1708, the seat of government was moved to Providence, renamed Annapolis in honor of Queen Anne. St. Mary's City is now an archaeological site, with a small tourist center.

Just as the city plan for St. Mary's City reflected the ideals of the founders, the city plan of Annapolis reflected those in power at the turn of the 18th century. The plan of Annapolis extends from two circles at the center of the city – one including the State House

Maryland State House

The Maryland State House is located in Annapolis and is the oldest state capitol in continuous legislative use, dating to 1772. It houses the Maryland General Assembly and offices of the Governor and Lieutenant Governor. The capitol has the distinction of being topped by the largest wooden dome in...

and the other the Anglican St. Anne's Church

St. Anne's Church (Annapolis, Maryland)

St. Anne's Episcopal Church is a historic Episcopal church located in Church Circle, Annapolis. The first church in Annapolis, it was founded in 1692 to serve as the parish church for the newly created Middle Neck Parish, one of the original 30 Anglican parishes in the Province of Maryland.-First...

(now Episcopal

Episcopal Church (United States)

The Episcopal Church is a mainline Anglican Christian church found mainly in the United States , but also in Honduras, Taiwan, Colombia, Ecuador, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Venezuela, the British Virgin Islands and parts of Europe...

). The plan reflected a stronger relationship between church and state, and a colonial government more closely aligned with the Protestant church.

Based on an incorrect map, the original royal charter granted Maryland the Potomac River

Potomac River

The Potomac River flows into the Chesapeake Bay, located along the mid-Atlantic coast of the United States. The river is approximately long, with a drainage area of about 14,700 square miles...

and territory northward to the fortieth parallel

40th parallel north

The 40th parallel north is a circle of latitude that is 40 degrees north of the Earth's equatorial plane. It crosses Europe, the Mediterranean Sea, Asia, the Pacific Ocean, North America, and the Atlantic Ocean....

. This was found to be a problem, as the northern boundary would have put Philadelphia, the major city in Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania

The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania is a U.S. state that is located in the Northeastern and Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States. The state borders Delaware and Maryland to the south, West Virginia to the southwest, Ohio to the west, New York and Ontario, Canada, to the north, and New Jersey to...

, within Maryland. The Calvert family

Baron Baltimore

Baron Baltimore, of Baltimore Manor in County Longford, was a title in the Peerage of Ireland. It was created in 1625 for George Calvert and became extinct on the death of the sixth Baron in 1771. The title was held by several members of the Calvert family who were proprietors of the palatinates...

, which controlled Maryland, and the Penn family

William Penn

William Penn was an English real estate entrepreneur, philosopher, and founder of the Province of Pennsylvania, the English North American colony and the future Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. He was an early champion of democracy and religious freedom, notable for his good relations and successful...

, which controlled Pennsylvania, decided in 1750 to engage two surveyors, Charles Mason

Charles Mason

Charles Mason was an English astronomer who made significant contributions to 18th-century science and American history, particularly through his involvement with the survey of the Mason-Dixon line, which came to mark the division between the northern and southern United States...

and Jeremiah Dixon

Jeremiah Dixon

Jeremiah Dixon was an English surveyor and astronomer who is perhaps best known for his work with Charles Mason, from 1763 to 1767, in determining what was later called the Mason-Dixon line....

, to establish a boundary.

They surveyed what became known as the Mason–Dixon Line, which became the boundary between the two colonies. The crests of the Penn family and of the Calvert family were put at the Mason–Dixon line to mark it. Later the Mason–Dixon line was used as a boundary between free and slave states under the Missouri Compromise

Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise was an agreement passed in 1820 between the pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions in the United States Congress, involving primarily the regulation of slavery in the western territories. It prohibited slavery in the former Louisiana Territory north of the parallel 36°30'...

of 1820.

The Revolutionary period

Maryland did not at first favor independence from Great Britain and gave instructions to that effect to its delegates to the Continental CongressContinental Congress

The Continental Congress was a convention of delegates called together from the Thirteen Colonies that became the governing body of the United States during the American Revolution....

. During this initial phase of the Revolutionary period

American Revolution

The American Revolution was the political upheaval during the last half of the 18th century in which thirteen colonies in North America joined together to break free from the British Empire, combining to become the United States of America...

, Maryland was governed by the Assembly of Freemen, an assembly of the state's counties

County (United States)

In the United States, a county is a geographic subdivision of a state , usually assigned some governmental authority. The term "county" is used in 48 of the 50 states; Louisiana is divided into parishes and Alaska into boroughs. Parishes and boroughs are called "county-equivalents" by the U.S...

. The first convention lasted four days, from June 22 to June 25, 1774. All sixteen counties then existing were represented by a total of 92 members; Matthew Tilghman

Matthew Tilghman

Matthew Tilghman was an American planter and Revolutionary leader from Maryland, who served as a delegate to the Continental Congress from 1774 to 1776.-Early life:...

was elected chairman.

.jpg)

State constitution (United States)

In the United States, each state has its own constitution.Usually, they are longer than the 7,500-word federal Constitution and are more detailed regarding the day-to-day relationships between government and the people. The shortest is the Constitution of Vermont, adopted in 1793 and currently...

, one that did not refer to parliament or the king, but would be a government "...of the people only." After they set dates and prepared notices to the counties they adjourned. On August 1, all freemen with property elected delegates for the last convention. The ninth and last convention was also known as the Constitutional Convention of 1776. They drafted a constitution, and when they adjourned on November 11, they would not meet again. The conventions were replaced by the new state government which the Maryland Constitution of 1776

Maryland Constitution of 1776

The Maryland Constitution of 1778 was the first of four constitutions under which the U.S. state of Maryland has been governed. It was that state's basic law from its adoption in 1776 until the Maryland Constitution of 1851 took effect on July 4th of that year.-Background and drafting:The eighth...

had established. Thomas Johnson became the state's first elected governor.

On March 1, 1781, the Articles of Confederation

Articles of Confederation

The Articles of Confederation, formally the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, was an agreement among the 13 founding states that legally established the United States of America as a confederation of sovereign states and served as its first constitution...

took effect with Maryland's ratification. The articles had initially been submitted to the states on November 17, 1777, but the ratification process dragged on for several years, stalled by an interstate quarrel over claims to uncolonized land in the west. Maryland was the last hold-out; it refused to ratify until Virginia

Virginia

The Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there...

and New York agreed to rescind their claims to lands in what became the Northwest Territory

Northwest Territory

The Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, more commonly known as the Northwest Territory, was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 13, 1787, until March 1, 1803, when the southeastern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the state of Ohio...

.

Battles of the American Revolutionary War

This is a list of military actions in the American Revolutionary War. Actions marked with an asterisk involved no casualties.-Major campaigns, theaters, and expeditions of the war:*Boston campaign *Invasion of Canada...

occurred in Maryland. However, this did not prevent the state's soldiers from distinguishing themselves through their service. General George Washington

George Washington

George Washington was the dominant military and political leader of the new United States of America from 1775 to 1799. He led the American victory over Great Britain in the American Revolutionary War as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army from 1775 to 1783, and presided over the writing of...

was impressed with the Maryland regulars (the "Maryland Line

Maryland Line

The Maryland Line was a formation within the Continental Army. The term "Maryland Line" referred to the quota of numbered infantry regiments assigned to Maryland at various times by the Continental Congress. These, together with similar contingents from the other twelve states, formed the...

") who fought in the Continental Army

Continental Army

The Continental Army was formed after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War by the colonies that became the United States of America. Established by a resolution of the Continental Congress on June 14, 1775, it was created to coordinate the military efforts of the Thirteen Colonies in...

and, according to one tradition, this led him to bestow the name "Old Line State" on Maryland. Today, the Old Line State is one of Maryland's two official nicknames.

The state also filled other roles during the war. For instance, the Continental Congress

Continental Congress

The Continental Congress was a convention of delegates called together from the Thirteen Colonies that became the governing body of the United States during the American Revolution....

met briefly in Baltimore

Baltimore

Baltimore is the largest independent city in the United States and the largest city and cultural center of the US state of Maryland. The city is located in central Maryland along the tidal portion of the Patapsco River, an arm of the Chesapeake Bay. Baltimore is sometimes referred to as Baltimore...

from December 20, 1776, through March 4, 1777. Furthermore, a Marylander, John Hanson

John Hanson

John Hanson was a merchant and public official from Maryland during the era of the American Revolution. After serving in a variety of roles for the Patriot cause in Maryland, in 1779 Hanson was elected as a delegate to the Continental Congress...

, served as President of the Continental Congress

President of the Continental Congress

The President of the Continental Congress was the presiding officer of the Continental Congress, the convention of delegates that emerged as the first national government of the United States during the American Revolution...

from 1781 to 1782. Hanson was the first person to serve a full term as President of the Congress under the Articles of Confederation.

From November 26, 1783, to June 3, 1784, Annapolis served as the United States capital, and the Confederation Congress met in the Maryland State House

Maryland State House

The Maryland State House is located in Annapolis and is the oldest state capitol in continuous legislative use, dating to 1772. It houses the Maryland General Assembly and offices of the Governor and Lieutenant Governor. The capitol has the distinction of being topped by the largest wooden dome in...

. (Annapolis was a candidate to become the new nation's permanent capital before Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

was built). It was in the old senate chamber that George Washington

George Washington

George Washington was the dominant military and political leader of the new United States of America from 1775 to 1799. He led the American victory over Great Britain in the American Revolutionary War as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army from 1775 to 1783, and presided over the writing of...

famously resigned his commission as commander in chief of the Continental Army on December 23, 1783. It was also there that the Treaty of Paris

Treaty of Paris (1783)

The Treaty of Paris, signed on September 3, 1783, ended the American Revolutionary War between Great Britain on the one hand and the United States of America and its allies on the other. The other combatant nations, France, Spain and the Dutch Republic had separate agreements; for details of...

, which ended the Revolutionary War

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War , the American War of Independence, or simply the Revolutionary War, began as a war between the Kingdom of Great Britain and thirteen British colonies in North America, and ended in a global war between several European great powers.The war was the result of the...

, was ratified by Congress on January 14, 1784.

Quasi-war with France

After the Revolution, the US Congress approved construction of six frigateFrigate

A frigate is any of several types of warship, the term having been used for ships of various sizes and roles over the last few centuries.In the 17th century, the term was used for any warship built for speed and maneuverability, the description often used being "frigate-built"...

s to form a nucleus of what became the United States Navy

United States Navy

The United States Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the seven uniformed services of the United States. The U.S. Navy is the largest in the world; its battle fleet tonnage is greater than that of the next 13 largest navies combined. The U.S...

. Of the first three commissioned, one was designated for construction in Baltimore's shipyards and was named USS Constellation

USS Constellation (1797)

USS Constellation was a 38-gun frigate, one of the six original frigates authorized for construction by the Naval Act of 1794. She was distinguished as the first U.S. Navy vessel to put to sea and the first U.S. Navy vessel to engage and defeat an enemy vessel...

.

Constellation became the first official US Navy ship put to sea. Almost immediately after getting underway, Constellation was ordered to the Caribbean

Caribbean

The Caribbean is a crescent-shaped group of islands more than 2,000 miles long separating the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea, to the west and south, from the Atlantic Ocean, to the east and north...

to protect US interests against the French. Tensions had increased following the Haitian Revolution

Haitian Revolution

The Haitian Revolution was a period of conflict in the French colony of Saint-Domingue, which culminated in the elimination of slavery there and the founding of the Haitian republic...

and independence in 1804, as European powers attempted to maintain control. During the Quasi-War

Quasi-War

The Quasi-War was an undeclared war fought mostly at sea between the United States and French Republic from 1798 to 1800. In the United States, the conflict was sometimes also referred to as the Franco-American War, the Pirate Wars, or the Half-War.-Background:The Kingdom of France had been a...

, Constellation, under the command of Captain Thomas Truxtun

Thomas Truxtun

Thomas Truxtun was an American naval officer who rose to the rank of commodore.Born near Hempstead, New York on Long Island, Truxtun had little formal education before joining the crew of the British merchant ship Pitt at the age of twelve...

, was forced into two major ship-to-ship naval battles involving the French ship L'Insurgente

USS Insurgent (1799)

The Insurgente was a 32-gun Sémillante class frigate of the French Navy. She was captured during the Quasi-War and then purchased by the United States Navy as USS Insurgent....

and the heavier frigate Vengeance

HMS Vengeance (1800)

The Vengeance was a Résistance class frigate of the French Navy, noted for her fight with during the Quasi-War, an inconclusive engagement that left both ships heavily damaged. During the French Revolutionary Wars, hunted Vengeance down and captured her after a sharp action...

. With its victories in both encounters, Constellation also achieved the first capture by an American vessel of an enemy ship (L'Insurgente). Its return to Baltimore was accompanied by joyous celebration and nationwide fame. The Constellation's incredible speed and power inspired the French to nickname her the "Yankee Racehorse".

The War of 1812

During the War of 1812War of 1812

The War of 1812 was a military conflict fought between the forces of the United States of America and those of the British Empire. The Americans declared war in 1812 for several reasons, including trade restrictions because of Britain's ongoing war with France, impressment of American merchant...

the British conducted raids against cities along Chesapeake Bay

Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay is the largest estuary in the United States. It lies off the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by Maryland and Virginia. The Chesapeake Bay's drainage basin covers in the District of Columbia and parts of six states: New York, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, and West...

, up to and including Havre de Grace

Havre de Grace, Maryland

Havre de Grace is a city in Harford County, Maryland, United States. Located at the mouth of the Susquehanna River and the head of the Chesapeake Bay, Havre de Grace is named after the port city of Le Havre, France, which was first named Le Havre de Grâce, meaning in French "Harbor of Grace." As...

. There were also two notable battles that occurred in the state. The first was the Battle of Bladensburg

Battle of Bladensburg

The Battle of Bladensburg took place during the War of 1812. The defeat of the American forces there allowed the British to capture and burn the public buildings of Washington, D.C...

, which occurred on August 24, 1814 just outside the national capital, Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

The militiamen defending the city were routed and retreated in confusion through the streets of the city. After overrunning the confused American defenders at Bladensburg, the British took Washington, D.C. They burned and looted major public buildings (see Burning of Washington

Burning of Washington

The Burning of Washington was an armed conflict during the War of 1812 between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the United States of America. On August 24, 1814, led by General Robert Ross, a British force occupied Washington, D.C. and set fire to many public buildings following...

), forcing President James Madison

James Madison

James Madison, Jr. was an American statesman and political theorist. He was the fourth President of the United States and is hailed as the “Father of the Constitution” for being the primary author of the United States Constitution and at first an opponent of, and then a key author of the United...

to flee to Brookeville, Maryland

Brookeville, Maryland

Brookeville is a town located twenty miles north of Washington, D.C. and two miles north of Olney in northeastern Montgomery County, Maryland. Brookeville was settled by Quakers late in the 18th century, and was formally incorporated as a town in 1808...

.

Baltimore

Baltimore is the largest independent city in the United States and the largest city and cultural center of the US state of Maryland. The city is located in central Maryland along the tidal portion of the Patapsco River, an arm of the Chesapeake Bay. Baltimore is sometimes referred to as Baltimore...

, where they hoped to strike a knockout blow against the demoralized Americans. Baltimore was not only a busy port, but the British thought it harbored many of the privateer

Privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship authorized by a government by letters of marque to attack foreign shipping during wartime. Privateering was a way of mobilizing armed ships and sailors without having to spend public money or commit naval officers...

s who were despoiling British ships. The city's defenses were under the command of Major General

Major General

Major general or major-general is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. A major general is a high-ranking officer, normally subordinate to the rank of lieutenant general and senior to the ranks of brigadier and brigadier general...

Samuel Smith

Samuel Smith (Maryland)

Samuel Smith was a United States Senator and Representative from Maryland, a mayor of Baltimore, Maryland, and a general in the Maryland militia. He was the brother of cabinet secretary Robert Smith.-Biography:...

, an officer of Maryland militia and a United States senator. Baltimore had been well fortified with excellent supplies and some 15,000 troops. Maryland militia fought a determined delaying action at the Battle of North Point

Battle of North Point

The Battle of North Point was fought on September 12, 1814, between General John Stricker's Maryland Militia and a British force led by Major General Robert Ross. Although tactically a British victory, the battle delayed the British advance against Baltimore, buying valuable time for the defense of...

, during which a Maryland militia marksman shot and killed the British commander, general Robert Ross. The battle bought enough time for Baltimore's defenses to be strengthened.

After advancing to the edge of American defenses, the British halted their advance and withdrew. With the failure of the land advance, the sea battle became irrelevant and the British retreated.

At Fort McHenry

Fort McHenry

Fort McHenry, in Baltimore, Maryland, is a star-shaped fort best known for its role in the War of 1812, when it successfully defended Baltimore Harbor from an attack by the British navy in Chesapeake Bay...

, some 1000 soldiers under the command of Major George Armistead

George Armistead

George Armistead was an American military officer who served as the commander of Fort McHenry during the Battle of Baltimore in the War of 1812.-Life and career:...

awaited the British naval bombardment. Their defense was augmented by the sinking of a line of American merchant ships at the adjacent entrance to Baltimore Harbor in order to thwart passage of British ships. The attack began on the morning of September 13, as the British fleet of some nineteen ships began pounding the fort with rockets and mortar shells. After an initial exchange of fire, the British fleet withdrew just beyond the 1.5 miles (2.4 km) range of Fort McHenry's cannons. For the next 25 hours, they bombarded the outmanned Americans. On the morning of September 14, an oversized American flag, which had been hastily sewn for this event, still flew over Fort McHenry. The British knew that victory had eluded them. The bombardment of the fort inspired Francis Scott Key

Francis Scott Key

Francis Scott Key was an American lawyer, author, and amateur poet, from Georgetown, who wrote the lyrics to the United States' national anthem, "The Star-Spangled Banner".-Life:...

, a native of Frederick, Maryland

Frederick, Maryland

Frederick is a city in north-central Maryland. It is the county seat of Frederick County, the largest county by area in the state of Maryland. Frederick is an outlying community of the Washington-Arlington-Alexandria, DC-VA-MD-WV Metropolitan Statistical Area, which is part of a greater...

, to write "The Star-Spangled Banner

The Star-Spangled Banner

"The Star-Spangled Banner" is the national anthem of the United States of America. The lyrics come from "Defence of Fort McHenry", a poem written in 1814 by the 35-year-old lawyer and amateur poet, Francis Scott Key, after witnessing the bombardment of Fort McHenry by the British Royal Navy ships...

" as witness to the assault. It later became the country's national anthem

National anthem

A national anthem is a generally patriotic musical composition that evokes and eulogizes the history, traditions and struggles of its people, recognized either by a nation's government as the official national song, or by convention through use by the people.- History :Anthems rose to prominence...

.

Maryland during the Frontier Age

In 1839, the United States' first passenger railway service opened between Baltimore and nearby Ellicott CityEllicott City, Maryland

Ellicott City is an unincorporated community and census-designated place in Howard County, Maryland, United States. It is part of the Baltimore-Washington Metropolitan Area. The population was 65,834 at the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Howard County...

. As the railway expanded westward to Cumberland

Cumberland, Maryland

Cumberland is a city in the far western, Appalachian portion of Maryland, United States. It is the county seat of Allegany County, and the primary city of the Cumberland, MD-WV Metropolitan Statistical Area. At the 2010 census, the city had a population of 20,859, and the metropolitan area had a...

and Chicago

Chicago

Chicago is the largest city in the US state of Illinois. With nearly 2.7 million residents, it is the most populous city in the Midwestern United States and the third most populous in the US, after New York City and Los Angeles...

, it competed for business with the earlier 189 miles (304.2 km) Chesapeake and Ohio Canal

Chesapeake and Ohio Canal

The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, abbreviated as the C&O Canal, and occasionally referred to as the "Grand Old Ditch," operated from 1831 until 1924 parallel to the Potomac River in Maryland from Cumberland, Maryland to Washington, D.C. The total length of the canal is about . The elevation change of...

and the National Road

National Road

The National Road or Cumberland Road was the first major improved highway in the United States to be built by the federal government. Construction began heading west in 1811 at Cumberland, Maryland, on the Potomac River. It crossed the Allegheny Mountains and southwestern Pennsylvania, reaching...

.

The United States Naval Academy

United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy is a four-year coeducational federal service academy located in Annapolis, Maryland, United States...

was founded in Annapolis

Annapolis, Maryland

Annapolis is the capital of the U.S. state of Maryland, as well as the county seat of Anne Arundel County. It had a population of 38,394 at the 2010 census and is situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east of Washington, D.C. Annapolis is...

in 1845, and the Maryland Agricultural College was chartered in 1856, growing eventually into the University of Maryland

University of Maryland, College Park

The University of Maryland, College Park is a top-ranked public research university located in the city of College Park in Prince George's County, Maryland, just outside Washington, D.C...

.

Maryland in the Civil War

See also: American Civil WarAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

, Origins of the American Civil War

Origins of the American Civil War

The main explanation for the origins of the American Civil War is slavery, especially Southern anger at the attempts by Northern antislavery political forces to block the expansion of slavery into the western territories...

and History of slavery in Maryland

History of slavery in Maryland

The institution of Slavery in Maryland would last around 200 years, and initially it developed along very similar lines to neighbouring Virginia...

Maryland's sympathies

Northern United States

Northern United States, also sometimes the North, may refer to:* A particular grouping of states or regions of the United States of America. The United States Census Bureau divides some of the northernmost United States into the Midwest Region and the Northeast Region...

and South

Southern United States

The Southern United States—commonly referred to as the American South, Dixie, or simply the South—constitutes a large distinctive area in the southeastern and south-central United States...

. As in Virginia

Virginia

The Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there...

and Delaware

Delaware

Delaware is a U.S. state located on the Atlantic Coast in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It is bordered to the south and west by Maryland, and to the north by Pennsylvania...

, some planters in Maryland had freed their slaves in the twenty years after the Revolutionary War. By 1860 Maryland's free black population comprised 49.1% of the total of African Americans in the state. After John Brown

John Brown (abolitionist)

John Brown was an American revolutionary abolitionist, who in the 1850s advocated and practiced armed insurrection as a means to abolish slavery in the United States. He led the Pottawatomie Massacre during which five men were killed, in 1856 in Bleeding Kansas, and made his name in the...

's raid on Harper's Ferry, Virginia (now in West Virginia

West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian and Southeastern regions of the United States, bordered by Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Ohio to the northwest, Pennsylvania to the northeast and Maryland to the east...

), some citizens in slaveholding areas began forming local militias. Of the 1860 population of 687,000, about 60,000 men joined the Union

Union (American Civil War)

During the American Civil War, the Union was a name used to refer to the federal government of the United States, which was supported by the twenty free states and five border slave states. It was opposed by 11 southern slave states that had declared a secession to join together to form the...

and about 25,000 fought for the Confederacy

Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America was a government set up from 1861 to 1865 by 11 Southern slave states of the United States of America that had declared their secession from the U.S...

. The political sentiments of each group generally reflected their economic interests.

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

occurred in Baltimore

Baltimore riot of 1861

The Baltimore riot of 1861 was an incident that took place on April 19, 1861, in Baltimore, Maryland between Confederate sympathizers and members of the Massachusetts militia en route to Washington for Federal service...

involving Massachusetts

Massachusetts

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States of America. It is bordered by Rhode Island and Connecticut to the south, New York to the west, and Vermont and New Hampshire to the north; at its east lies the Atlantic Ocean. As of the 2010...

troops who were fired on while marching between railroad stations on April 19, 1861. After that, Baltimore Mayor George William Brown

George William Brown

George William Brown was the mayor of Baltimore, Maryland from 1860 to 1861.-Pratt Street Riot:Brown played an important role in controlling the Pratt Street Riot on April 19, 1861, at the onset of the American Civil War. After the Pratt Street Riot, some small skirmishes occurred throughout...

, Marshal George P. Kane, and former Governor Enoch Louis Lowe

Enoch Louis Lowe

Enoch Louis Lowe served as the 29th Governor of the state of Maryland in the United States from 1851 to 1854.-Early life:...

requested that Maryland Governor Thomas H. Hicks, a slave owner from the Eastern Shore

Eastern Shore of Maryland

The Eastern Shore of Maryland is a territorial part of the U.S. state of Maryland that lies predominately on the east side of the Chesapeake Bay and consists of nine counties. The origin of term Eastern Shore was derived to distinguish a territorial part of the State of Maryland from the Western...

, burn the railroad bridges and cut the telegraph lines leading to Baltimore to prevent further troops from entering the state. Hicks reportedly approved this proposal. These actions were addressed in the famous federal court case of Ex parte Merryman

Ex parte Merryman

Ex parte Merryman, 17 F. Cas. 144 , is a well-known U.S. federal court case which arose out of the American Civil War. It was a test of the authority of the President to suspend "the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus"...

.

Maryland remained part of the Union during the Civil War. President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. He successfully led his country through a great constitutional, military and moral crisis – the American Civil War – preserving the Union, while ending slavery, and...

's strong hand suppressing violence and dissent in Maryland and the belated assistance of Governor Hicks played important roles. Hicks worked with federal officials to stop further violence. As an illustration of the state's sympathies, it is notable that in the 1860 election, Lincoln received only one vote in Prince George's County

Prince George's County, Maryland

Prince George's County is a county located in the U.S. state of Maryland, immediately north, east, and south of Washington, DC. As of 2010, it has a population of 863,420 and is the wealthiest African-American majority county in the nation....

.

Marylanders sympathetic to the South easily crossed the Potomac River

Potomac River

The Potomac River flows into the Chesapeake Bay, located along the mid-Atlantic coast of the United States. The river is approximately long, with a drainage area of about 14,700 square miles...

to join and fight for the Confederacy. Exiles organized a "Maryland Line" in the Army of Northern Virginia

Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was the primary military force of the Confederate States of America in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War, as well as the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most often arrayed against the Union Army of the Potomac...

which consisted of one infantry

Infantry

Infantrymen are soldiers who are specifically trained for the role of fighting on foot to engage the enemy face to face and have historically borne the brunt of the casualties of combat in wars. As the oldest branch of combat arms, they are the backbone of armies...

regiment, one infantry battalion, two cavalry

Cavalry

Cavalry or horsemen were soldiers or warriors who fought mounted on horseback. Cavalry were historically the third oldest and the most mobile of the combat arms...

battalions and four battalions of artillery

Artillery

Originally applied to any group of infantry primarily armed with projectile weapons, artillery has over time become limited in meaning to refer only to those engines of war that operate by projection of munitions far beyond the range of effect of personal weapons...

. According to the best extant records, up to 25,000 Marylanders went south to fight for the Confederacy. About 60,000 Maryland men served in all branches of the Union military. However, many of the Union troops were said to enlist on the promise of home garrison duty.

To prevent an uprising in Baltimore, a Union artillery garrison was placed on Federal Hill with express orders to destroy the city should Southern sympathizers overwhelm law and order there. Following the Baltimore riot of 1861

Baltimore riot of 1861

The Baltimore riot of 1861 was an incident that took place on April 19, 1861, in Baltimore, Maryland between Confederate sympathizers and members of the Massachusetts militia en route to Washington for Federal service...

, Union troops under the command of General Benjamin F. Butler

Benjamin Franklin Butler (politician)

Benjamin Franklin Butler was an American lawyer and politician who represented Massachusetts in the United States House of Representatives and later served as the 33rd Governor of Massachusetts....

occupied the hill in the middle of the night. This was against Washington orders. Butler and his men erected a small fort, with cannon pointing towards the central business district. Their goal was to guarantee the allegiance of the city and the state of Maryland to the federal government under threat of force. This fort and the Union occupation persisted for the duration of the Civil War. A large flag, a few cannon, and a small Grand Army of the Republic

Grand Army of the Republic

The Grand Army of the Republic was a fraternal organization composed of veterans of the Union Army, US Navy, US Marines and US Revenue Cutter Service who served in the American Civil War. Founded in 1866 in Decatur, Illinois, it was dissolved in 1956 when its last member died...

monument remain to testify to this period of the hill's history.

Because Maryland remained in the Union, it was not included under the Emancipation Proclamation

Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation is an executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War using his war powers. It proclaimed the freedom of 3.1 million of the nation's 4 million slaves, and immediately freed 50,000 of them, with nearly...

. A constitutional convention was held during 1864 that culminated in the passage of a new state constitution

Maryland Constitution of 1864

The Maryland Constitution of 1864 was the third of the four constitutions which have governed the U.S. state of Maryland. A controversial product of the Civil War and in effect only until 1867, when the state's present constitution was adopted, the 1864 document was short-lived.-Drafting:The 1864...

on November 1 of that year. Article 24 of that document outlawed the practice of slavery. The right to vote was extended to non-white males in the Maryland Constitution of 1867, which is still in effect today.

During this time the USS Constellation

USS Constellation (1854)

USS Constellation constructed in 1854 is a sloop-of-war and the second United States Navy ship to carry this famous name. According to the US Naval Registry the original frigate was disassembled on 25 June 1853 in Gosport Navy Yard in Norfolk, Virginia, and the sloop-of-war was constructed in the...

was flagship of the US Africa Squadron

Africa Squadron

The Africa Squadron was a unit of the United States Navy that operated from 1819 to 1861 to suppress the slave trade along the coast of West Africa...

from 1859 to 1861. In this period, she disrupted the African slave trade

African slave trade

Systems of servitude and slavery were common in many parts of Africa, as they were in much of the ancient world. In some African societies, the enslaved people were also indentured servants and fully integrated; in others, they were treated much worse...

by interdicting three slave ships and releasing the imprisoned slaves. The last of the ships was captured at the outbreak of the Civil War: Constellation overpowered the slaver brig Triton in African coastal waters. Constellation spent much of the war as a deterrent to Confederate cruisers and commerce raiders in the Mediterranean Sea

Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean surrounded by the Mediterranean region and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Anatolia and Europe, on the south by North Africa, and on the east by the Levant...

.

The war on Maryland soil

Battle of Antietam

The Battle of Antietam , fought on September 17, 1862, near Sharpsburg, Maryland, and Antietam Creek, as part of the Maryland Campaign, was the first major battle in the American Civil War to take place on Northern soil. It was the bloodiest single-day battle in American history, with about 23,000...

, fought on September 17, 1862, near Sharpsburg

Sharpsburg, Maryland

Sharpsburg is a town in Washington County, Maryland, United States, approximately south of Hagerstown. The population was 691 at the 2000 census....

. The battle was the culmination of Robert E. Lee

Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee was a career military officer who is best known for having commanded the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia in the American Civil War....

's Maryland Campaign

Maryland Campaign

The Maryland Campaign, or the Antietam Campaign is widely considered one of the major turning points of the American Civil War. Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's first invasion of the North was repulsed by Maj. Gen. George B...

, which aimed to secure new supplies, recruit fresh men from among the considerable pockets of Confederate sympathies in Maryland, and to impact public opinion in the North. With those goals, Lee's Army of Northern Virginia, consisting of about 40,000 men, had entered Maryland following their recent victory at Second Bull Run.

While Major General George B. McClellan

George B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan was a major general during the American Civil War. He organized the famous Army of the Potomac and served briefly as the general-in-chief of the Union Army. Early in the war, McClellan played an important role in raising a well-trained and organized army for the Union...

's 87,000-man Army of the Potomac

Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the major Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War.-History:The Army of the Potomac was created in 1861, but was then only the size of a corps . Its nucleus was called the Army of Northeastern Virginia, under Brig. Gen...

was moving to intercept Lee, a Union

Union Army

The Union Army was the land force that fought for the Union during the American Civil War. It was also known as the Federal Army, the U.S. Army, the Northern Army and the National Army...

soldier discovered a mislaid copy of the detailed battle plans of Lee's army. The order indicated that Lee had divided his army and dispersed portions geographically (to Harpers Ferry, West Virginia

Harpers Ferry, West Virginia

Harpers Ferry is a historic town in Jefferson County, West Virginia, United States. In many books the town is called "Harper's Ferry" with an apostrophe....

, and Hagerstown, Maryland

Hagerstown, Maryland

Hagerstown is a city in northwestern Maryland, United States. It is the county seat of Washington County, and, by many definitions, the largest city in a region known as Western Maryland. The population of Hagerstown city proper at the 2010 census was 39,662, and the population of the...

), thus making each subject to isolation and defeat in detail if McClellan could move quickly enough. McClellan waited about 18 hours before deciding to take advantage of this intelligence and position his forces based on it, thus endangering a golden opportunity to defeat Lee decisively.

Antietam Creek

Antietam Creek is a tributary of the Potomac River located in south central Pennsylvania and western Maryland in the United States, a region known as the Hagerstown Valley...

. Although McClellan arrived in the area on September 16, his trademark caution delayed his attack on Lee, which gave the Confederates more time to prepare defensive positions and allowed Longstreet's

James Longstreet

James Longstreet was one of the foremost Confederate generals of the American Civil War and the principal subordinate to General Robert E. Lee, who called him his "Old War Horse." He served under Lee as a corps commander for many of the famous battles fought by the Army of Northern Virginia in the...

corps to arrive from Hagerstown and Jackson's

Stonewall Jackson

ຄຽשת״ׇׂׂׂׂ֣|birth_place= Clarksburg, Virginia |death_place=Guinea Station, Virginia|placeofburial=Stonewall Jackson Memorial CemeteryLexington, Virginia|placeofburial_label= Place of burial|image=...

corps, minus A. P. Hill

A. P. Hill

Ambrose Powell Hill, Jr. , was a career U.S. Army officer in the Mexican-American War and Seminole Wars and a Confederate general in the American Civil War...

's division, to arrive from Harpers Ferry. McClellan's two-to-one advantage in the battle was almost completely nullified by a lack of coordination and concentration of Union forces, which allowed Lee to shift his defensive forces to parry each thrust.

Although a tactical draw, the Battle of Antietam was considered a strategic Union victory and a turning point

Turning point of the American Civil War

There is widespread disagreement over the turning point of the American Civil War. The idea of a turning point is an event after which most observers would agree that the eventual outcome was inevitable. While the Battle of Gettysburg is the most widely cited , there are several other arguable...

of the war. It forced the end of Lee's invasion of the North. It also was enough of a victory to enable President Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, which took effect on January 1, 1863. He had been advised by his Cabinet to make the announcement after a Union victory, to avoid any perception that it was issued out of desperation. The Union's winning the Battle of Antietam also may have dissuaded the governments of France

Second French Empire

The Second French Empire or French Empire was the Imperial Bonapartist regime of Napoleon III from 1852 to 1870, between the Second Republic and the Third Republic, in France.-Rule of Napoleon III:...

and Great Britain

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the formal name of the United Kingdom during the period when what is now the Republic of Ireland formed a part of it....

from recognizing the Confederacy. Some observers believed they may have done so in the aftermath of another Union defeat.

During the war, Maryland's naval contribution, the relatively new sloop-of-war USS Constellation

USS Constellation (1854)

USS Constellation constructed in 1854 is a sloop-of-war and the second United States Navy ship to carry this famous name. According to the US Naval Registry the original frigate was disassembled on 25 June 1853 in Gosport Navy Yard in Norfolk, Virginia, and the sloop-of-war was constructed in the...

maintained her duty in slave ship interdiction for the Union Navy. Stationed in the Mediterranean, the Constellation actively protected convoys and defended against commerce raiders.

Post-Civil War political developments

Since Maryland had remained in the Union during the Civil War, the state did not undergo Reconstruction like the states of the former Confederacy. However, as a former "slave stateSlave state

In the United States of America prior to the American Civil War, a slave state was a U.S. state in which slavery was legal, whereas a free state was one in which slavery was either prohibited from its entry into the Union or eliminated over time...

", Maryland did have issues with the civil rights

Civil rights