History of atheism

Encyclopedia

Although the term atheism

originated in the 16th century—based on Ancient Greek

ἄθεος "godless, denying the gods, ungodly"—and open admission to positive atheism in modern times was not made earlier than in the late 18th century, atheistic ideas and beliefs, as well as their political influence, have a more expansive history.

The spontaneous proposition that there may be no gods after all is logically as old as theism

itself (and the proposition that there may be no God as old as the beginnings of monotheism

or henotheism

). Philosophical atheist thought appears in Europe and Asia from the 6th or 5th century BCE.

Will Durant explains that certain Pygmy tribes found in Africa were observed to have no identifiable cults or rites. There were no totems, no gods, no spirits. Their dead were buried without special ceremonies or accompanying items and received no further attention. They even appeared to lack simple superstitions, according to travelers' reports. The Vedahs of Ceylon, only admitted the possibility that gods might exist, but went no further. Neither prayers nor sacrifices were suggested in any way.

, Buddhism

, and certain sects

of Hinduism

in India, and of Taoism

in China.

Although these religions claim to offer a philosophic and salvific path not centering on deity worship, popular tradition in some sects of these religions has long embraced deity worship, the propitiation of spirits, and other elements of folk tradition. Furthermore, the Pali Tripiṭaka

, the oldest complete composition of scriptures, seems to accept as real the concepts of divine beings, the Vedic

(and other) gods, rebirth, and heaven and hell. While deities are not seen as necessary to the salvific goal of the early Buddhist tradition, their reality is not questioned.

, the Samkhya

and the early Mimamsa

school did not accept a creator-God in their respective systems.

The principal text of the Samkhya

school, the Samkhya Karika, was written by Ishvara Krishna

in the 4th century CE, by which time it was already a dominant Hindu school. The origins of the school are much older and are lost in legend. The school was both dualistic and atheistic. They believed in a dual existence of Prakriti ("nature") and Purusha

("spirit") and had no place for an Ishvara

("God") in its system, arguing that the existence of Ishvara cannot be proved and hence cannot be admitted to exist. The school dominated Hindu philosophy in its day, but declined after the 10th century, although commentaries were still being written as late as the 16th century.

The foundational text for the Mimamsa school is the Purva Mimamsa Sutras

of Jaimini (c. 3rd to 1st century BCE). The school reached its height c. 700 CE, and for some time in the Early Middle Ages

exerted near-dominant influence on learned Hindu thought. The Mimamsa school saw their primary enquiry was into the nature of dharma

based on close interpretation of the Vedas

. Its core tenets were ritual

ism (orthopraxy), anti-asceticism and anti-mysticism. The early Mimamsakas believed in an adrishta ("unseen") that is the result of performing karmas ("works") and saw no need for an Ishvara

("God") in their system. Mimamsa persists in some subschools of Hinduism today.

Indo-Aryan culture. Organized Jainism

can be dated back to Parshva

who lived in the 9th century BCE, and, more reliably, to Mahavira

, a teacher of the 6th century BCE, and a contemporary of the Buddha

. Jainism is a dualistic religion with the universe

made up of matter

and souls. The universe, and the matter and souls within it, is eternal and uncreated, and there is no omnipotent creator god in Jainism. There are, however, "gods" and other spirits who exist within the universe and Jains believe that the soul can attain "godhood", however none of these supernatural beings exercise any sort of creative activity or have the capacity or ability to intervene in answers to prayers.

school that originated in India

with the Bārhaspatya-sūtras (final centuries BCE) is probably the most explicitly atheist school of philosophy in the region. The school grew out of the generic skepticism in the Mauryan period. Already in the 6th century BCE, Ajita Kesakambalin, was quoted in Pali scriptures by the Buddhists with whom he was debating, teaching that "with the break-up of the body, the wise and the foolish alike are annihilated, destroyed. They do not exist after death."

Cārvākan philosophy is now known principally from its Astika and Buddhist opponents. The proper aim of a Cārvākan, according to these sources, was to live a prosperous, happy, productive life in this world. The Tattvopaplavasimha of Jayarashi Bhatta (c. 8th century) is sometimes cited as a surviving Carvaka text. The school appears to have died out sometime around the 15th century.

or a prime mover

is seen by many as a key distinction between Buddhism

and other religions. While Buddhist traditions do not deny the existence of supernatural beings (many are discussed in Buddhist scripture), it does not ascribe powers, in the typical Western sense, for creation, salvation or judgement, to the "gods".

Buddhists accept the existence of beings in higher realms (see Buddhist cosmology

), known as devas

, but they, like humans, are said to be suffering in samsara

, and not particularly wiser than us. In fact the Buddha is often portrayed as a teacher of the gods, and superior to them.

In western Classical Antiquity

In western Classical Antiquity

, theism was the fundamental belief that supported the divine right of the State (Polis

, later the Roman Empire

). Historically, any person who did not believe in any deity supported by the State was fair game to accusations of atheism, a capital crime

. For political reasons, Socrates

in Athens

(399 BCE) was accused of being 'atheos' ("refusing to acknowledge the gods recognized by the state"). Despite the charges, he claimed inspiration from a divine voice (Daimon

). Christians in Rome were also considered subversive to the state religion and persecuted as atheists. Thus, charges of atheism, meaning the subversion of religion, were often used similarly to charges of heresy

and impiety

– as a political tool to eliminate enemies.

began in the Greek world in the 6th century BCE. The first philosophers were not atheists, but they attempted to explain the world in terms of the processes of nature instead of by mythological accounts. Thus lightning

was the result of "wind breaking out and parting the clouds," and earthquake

s occurred when "the earth is considerably altered by heating and cooling." The early philosophers often criticised traditional religious notions. Xenophanes

(6th century BCE) famously said that if cows and horses had hands, "then horses would draw the forms of gods like horses, and cows like cows." Another philosopher, Anaxagoras

(5th century BCE), claimed that the Sun

was "a fiery mass, larger than the Peloponnese

;" a charge of impiety was brought against him, and he was forced to flee Athens

.

The first fully materialistic philosophy was produced by the Atomists

, Leucippus

and Democritus

(5th century BCE), who attempted to explain the formation and development of the world in terms of the chance movements of atom

s moving in infinite space.

Euripides

(480–406 BCE), in his play Bellerophon

, had the eponymous main character say:

“Doth some one say that there be gods above?

There are not; no, there are not. Let no fool,

Led by the old false fable, thus deceive you.”

Aristophanes

(ca. 448–380 BCE), known for his satirical style, said in his The Knights

play:

"Shrines! Shrines! Surely you don't believe in the gods. What's your argument? Where's your proof?"

stated at the beginning of a book that "With regard to the gods I am unable to say either that they exist or do not exist."

Diagoras of Melos

(5th century BCE) is known as the "first atheist". He blasphemed by making public the Eleusinian Mysteries

and discouraging people from being initiated. Somewhat later (c. 300 BCE), the Cyrenaic philosopher Theodorus of Cyrene

is supposed to have denied that gods exist, and wrote a book On the Gods expounding his views.

Euhemerus

(c. 330–260 BCE) published his view that the gods were only the deified rulers, conquerors and founders of the past, and that their cults and religions were in essence the continuation of vanished kingdoms and earlier political structures. Although Euhemerus was later criticized for having "spread atheism over the whole inhabited earth by obliterating the gods", his worldview was not atheist in a strict and theoretical sense, because he differentiated that the primordial gods were "eternal and imperishable". Some historians have argued that he merely aimed at reinventing the old religions in the light of the beginning deification of political rulers such as Alexander the Great. Euhemerus' work was translated into Latin by Ennius

, possibly to mythographically

pave the way for the planned divinization

of Scipio Africanus

in Rome.

(c. 300 BCE). Drawing on the ideas of Democritus

and the Atomists

, he espoused a materialistic philosophy where the universe was governed by the laws of chance without the need for divine intervention. Although he stated that the gods existed, he believed that they were uninterested in human existence. The aim of the Epicureans was to attain peace of mind by exposing fear of divine wrath as irrational. One of the most eloquent expression of Epicurean thought is Lucretius

' On the Nature of Things

(1st century BCE). Lucretius declared "There is no God". The Epicureans also denied the existence of an afterlife. Epicureans were not persecuted, but their teachings were controversial, and were harshly attacked by the mainstream schools of Stoicism

and Neoplatonism

. The movement remained marginal, and gradually died out at the end of the Roman Empire

.

(ca. 106–43 BCE) declared:

"In this subject of the nature of the gods the first question is: do the gods exist or do they not? It is difficult, you will say, to deny that they exist. I would agree, if we were arguing the matter in a public assembly, but in a private discussion of this kind it is perfectly easy to do so."

and viewed negatively by the authors of the Biblical texts. Psalm 14:1–3 reads "The fool says in his heart 'There is no God.' They are corrupt, their deeds are vile; there is no one who does good.".

, scholars recognized the idea of atheism, and frequently attacked unbelievers

, although they were unable to name any actual atheists. When individuals were accused of atheism, they were usually viewed as heretics rather than proponents of atheism.

One notable figure was the 9th century scholar Ibn al-Rawandi

who criticized the notion of religious prophecy

including that of Muhammad

, and maintained that religious dogmas were not acceptable to reason and must be rejected. Other critics of religion in the Islamic world include the physician and philosopher Abu Bakr al-Razi (865–925), and the poet Al-Ma`arri (973–1057).

In the European Middle Ages

, no clear expression of atheism is known. The titular character of the Icelandic saga Hrafnkell, written in the late 13th century, says that I think it is folly to have faith in gods. After his temple to Freyr is burnt and he is enslaved he vows never to perform another sacrifice

, a position described in the sagas as goðlauss "godless". Jacob Grimm

in his Teutonic Mythology observes that

citing several other examples, including two kings.

In Christian Europe, people were persecuted for heresy, especially in countries where the Inquisition

was active. However, Thomas Aquinas

' five proofs of God's existence

and Anselm

's ontological argument

implicitly acknowledged the validity of the question about god's existence. The charge of atheism was used as way of attacking one's political or religious enemies. Pope Boniface VIII

, because he insisted on the political supremacy of the church, was accused by his enemies after his death of holding (unlikely) atheistic positions such as "neither believing in the immortality nor incorruptibility of the soul, nor in a life to come."

and the Reformation

, criticism of the religious establishment became more frequent in predominantly Christian countries, but did not amount to actual atheism.

The term athéisme was coined in France in the 16th century. The word "atheist" appears in English books at least as early as 1566.

The concept of atheism re-emerged initially as a reaction to the intellectual and religious turmoil of the Age of Enlightenment

and the Reformation – as a charge used by those who saw the denial of god and godlessness in the controversial positions being put forward by others. During the 16th and 17th centuries, the word 'atheist' was used exclusively as an insult; nobody wanted to be regarded as an atheist. Although one overtly atheistic compendium known as the Theophrastus redivivus

was published by an anonymous author in the 17th century, atheism was an epithet implying a lack of moral restraint

. How dangerous it was to be accused of being an atheist at this time is illustrated by the examples of Étienne Dolet

who was strangled

and burned in 1546, and Giulio Cesare Vanini who received a similar fate in 1619. In 1689 the Polish nobleman Kazimierz Łyszczyński, who had allegedly denied the existence of God in his philosophical treatise De non existentia Dei, was condemned to death in Warsaw

for atheism and beheaded after his tongue was pulled out with a burning iron and his hands slowly burned. Similarly in 1766, the French nobleman Jean-François de la Barre

, was torture

d, beheaded, and his body burned for alleged vandalism

of a crucifix

, a case that became celebrated because Voltaire

tried unsuccessfully to have the sentence reversed.

Among those accused of atheism was Denis Diderot

(1713–1784), one of the Enlightenment's most prominent philosophes, and editor-in-chief of the Encyclopédie

, which sought to challenge religious, particularly Catholic

, dogma: "Reason is to the estimation of the philosophe what grace is to the Christian", he wrote. "Grace determines the Christian's action; reason the philosophe's". Diderot was briefly imprisoned for his writing, some of which was banned and burned.

The English materialist philosopher Thomas Hobbes

(1588–1679) was also accused of atheism, but he denied it. His theism was unusual, in that he held god to be material. Even earlier, the British playwright and poet, Christopher Marlowe

(1563–1593), was accused of atheism when a tract denying the divinity of Christ was found in his home. Before he could finish defending himself against the charge, Marlowe was murdered, although this was not related to the religious issue.

(1723–1789) in his 1770 work, The System of Nature

. D'Holbach was a Parisian social figure who conducted a famous salon widely attended by many intellectual notables of the day, including Denis Diderot

, Jean Jacques Rousseau, David Hume

, Adam Smith

, and Benjamin Franklin

. Nevertheless, his book was published under a pseudonym, and was banned and publicly burned by the Executioner

.

The Cult of Reason

was a creed based on atheism devised during the French Revolution

by Jacques Hébert

, Pierre Gaspard Chaumette

and their supporters. It was stopped by Maximilien Robespierre

, a Deist, who instituted the Cult of the Supreme Being

. Both cults were the outcome of the "de-Christianization" of French society

during the Revolution and part of the Reign of Terror

.

The culte de la Raison developed during the uncertain period 1792–94 (Years I and III of the Revolution), following the September Massacres

The culte de la Raison developed during the uncertain period 1792–94 (Years I and III of the Revolution), following the September Massacres

, when Revolutionary France was ripe with fears of internal and foreign enemies. Several Parisian churches were transformed into Temples of Reason, notably the Church of Saint-Paul Saint-Louis in the Marais

. The churches were closed in May 1793 and more securely, 24 November 1793, when the Catholic Mass was forbidden.

The Cult of Reason was celebrated in a carnival

The Cult of Reason was celebrated in a carnival

atmosphere of parades, ransacking of churches, ceremonious iconoclasm

, in which religious and royal images were defaced, and ceremonies which substituted the "martyrs of the Revolution" for Christian martyrs. The earliest public demonstrations took place en province, outside Paris, notably by Hébertists

in Lyon

, but took a further radical turn with the Fête de la Liberté ("Festival of Liberty") at Notre Dame de Paris

, 10 November (20 Brumaire) 1793, in ceremonies devised and organised by Pierre-Gaspard Chaumette. The Cult of Reason centered upon a young woman designated the Goddess of Reason

.

The pamphlet Answer to Dr Priestley

's Letters to a Philosophical Unbeliever (1782) is considered to be the first published declaration of atheism in Britain – plausibly the first in English (as distinct from covert or cryptically atheist works). The otherwise unknown 'William Hammon' (possibly a pseudonym) signed the preface and postscript as editor of the work, and the anonymous main text is attributed to Matthew Turner

(d. 1788?), a Liverpool physician who may have known Priestley. Historian of atheism David Berman has argued strongly for Turner's authorship, but also suggested that there may have been two authors.

of 1789 catapulted atheistic thought into political notability in some Western countries, and opened the way for the 19th century movements of Rationalism

, Freethought

, and Liberalism. Born in 1792, Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley

, a child of the Age of Enlightenment

, was expelled from England's Oxford University in 1811 for submitting to the Dean an anonymous pamphlet that he wrote titled The Necessity of Atheism. This pamphlet is considered by scholars as the first atheistic ideas published in the English language. An early atheistic influence in Germany was The Essence of Christianity by Ludwig Feuerbach (1804–1872). He influenced other German 19th century atheistic thinkers like Karl Marx

, Max Stirner

, Arthur Schopenhauer

(1788–1860) and Friedrich Nietzsche

(1844–1900).

The freethinker Charles Bradlaugh

(1833–1891) was repeatedly elected to the British Parliament, but was not allowed to take his seat after his request to affirm rather than take the religious oath was turned down (he then offered to take the oath, but this too was denied him). After Bradlaugh was re-elected for the fourth time, a new Speaker allowed Bradlaugh to take the oath and permitted no objections. He became the first outspoken atheist to sit in Parliament, where he participated in amending the Oaths Act

.

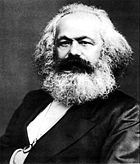

In 1844, Karl Marx (1818–1883), an atheistic political economist, wrote in his Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right: "Religious suffering is, at one and the same time, the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people

In 1844, Karl Marx (1818–1883), an atheistic political economist, wrote in his Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right: "Religious suffering is, at one and the same time, the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people

." Marx believed that people turn to religion in order to dull the pain caused by the reality of social situations; that is, Marx suggests religion is an attempt at transcending the material state of affairs in a society – the pain of class oppression – by effectively creating a dream world, rendering the religious believer amenable to social control

and exploitation in this world while they hope for relief and justice in life after death

. In the same essay, Marx states, "...[m]an creates religion, religion does not create man..."

Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Nietzsche

, a prominent 19th century philosopher, is well-known for coining the aphorism "God is dead

" (German: "Gott ist tot"); incidentally the phrase was not spoken by Nietzsche directly, but was used as a dialogue for the characters in his works. Nietzsche argued that Christian theism as a belief system had been a moral foundation of the Western world, and that the rejection and collapse of this foundation as a result of modern thinking (the death of God) would naturally cause a rise in nihilism

or the lack of values. While Nietzsche was staunchly atheistic, he was also concerned about the negative effects of nihilism on humanity. As such, he called for a re-evaluation of old values and a creation of new ones, hoping that in doing so man would achieve a higher state he labeled the Overman

.

, Objectivism

, secular humanism

, nihilism

, logical positivism

, Marxism

, anarchism

, feminism

, and the general scientific and rationalist movement. Neopositivism and analytical philosophy discarded classical rationalism and metaphysics in favor of strict empiricism and epistemological nominalism

. Proponents such as Bertrand Russell

emphatically rejected belief in God. In his early work, Ludwig Wittgenstein

attempted to separate metaphysical and supernatural language from rational discourse. Mencken debunked both the idea that science and religion are compatible, and the idea that science is a dogmatic belief system just like any religion

A. J. Ayer asserted the unverifiability and meaninglessness of religious statements, citing his adherence to the empirical sciences. The structuralism

of Lévi-Strauss

sourced religious language to the human subconscious, denying its transcendental meaning. J. N. Findlay

and J. J. C. Smart

argued that the existence of God is not logically necessary. Naturalists

and materialists

such as John Dewey

considered the natural world to be the basis of everything, denying the existence of God or immortality.

The 20th century also saw the political advancement of atheism, spurred on by interpretation of the works of Marx

and Engels

. State support of atheism

and opposition to organized religion was made policy in all communist state

s, including the People's Republic of China and the former Soviet Union

. In theory and in practice these states were secular. The justifications given for the social and political sidelining of religious organizations addressed, on one hand, the "irrationality" of religious belief, and on the other the "parasitical" nature of the relationship between the church and the population. Churches were sometimes tolerated, but subject to strict control – church officials had to be vetted by the state, while attendance of church functions could endanger one's career. Very often, the state's opposition to religion took more violent forms; Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

documents widespread persecution, imprisonments and torture of believers, in his seminal work The Gulag Archipelago

. Consequently, religious organizations, such as the Catholic Church, were among the most stringent opponents of communist regimes. In some cases, the initial strict measures of control and opposition to religious activity were gradually relaxed in communist states. On the other hand, Albania

under Enver Hoxha

became, in 1967, the first (and to date only) formally declared atheist state. Hoxha went far beyond what most other countries had attempted and completely prohibited religious observance, systematically repressing and persecuting adherents. The right to religious practice was restored in 1991.

In India, E. V. Ramasami Naicker (Periyar), a prominent atheist leader, fought against Hinduism

and the Brahmins for discriminating and dividing people in the name of caste

and religion. This was highlighted in 1956 when he made the Hindu god Rama

wear a garland made of slippers and made antitheistic

statements.

During the Cold War

, the United States often characterized its opponents as "Godless Communists", which tended to reinforce the view that atheists were unreliable and unpatriotic. Against this background, the words "under God" were inserted into the pledge of allegiance

in 1954, and the national motto was changed from E Pluribus Unum

to In God We Trust

in 1956. Madalyn Murray O'Hair

was perhaps one of the most influential American atheists; she brought forth the 1963 Supreme Court case Murray v. Curlett which banned compulsory prayer in public schools.

The early 21st century has continued to see secularism

The early 21st century has continued to see secularism

and atheism promoted in the Western world

, with the general consensus being that the number of people not affiliated with any particular religion has increased. This has been assisted by non-profit organizations such as the Freedom From Religion Foundation

in the United States which promotes the separation of church and state

, and the Brights movement

which aims to promote public understanding and acknowledgment of the naturalistic

worldview. In addition, a large number of accessible antitheist and secularist books, many of which became bestseller

s, were published by authors such as Michel Onfray

, Sam Harris

, Daniel Dennett

, Richard Dawkins

, and Christopher Hitchens

. This gave rise to the New Atheism

movement, a label that has been applied, sometimes pejoratively, to outspoken critics of theism. Richard Dawkins also propounds a more visible form of atheist activism which he light-heartedly describes as 'militant atheism'.

Atheism

Atheism is, in a broad sense, the rejection of belief in the existence of deities. In a narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there are no deities...

originated in the 16th century—based on Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek is the stage of the Greek language in the periods spanning the times c. 9th–6th centuries BC, , c. 5th–4th centuries BC , and the c. 3rd century BC – 6th century AD of ancient Greece and the ancient world; being predated in the 2nd millennium BC by Mycenaean Greek...

ἄθεος "godless, denying the gods, ungodly"—and open admission to positive atheism in modern times was not made earlier than in the late 18th century, atheistic ideas and beliefs, as well as their political influence, have a more expansive history.

The spontaneous proposition that there may be no gods after all is logically as old as theism

Theism

Theism, in the broadest sense, is the belief that at least one deity exists.In a more specific sense, theism refers to a doctrine concerning the nature of a monotheistic God and God's relationship to the universe....

itself (and the proposition that there may be no God as old as the beginnings of monotheism

Monotheism

Monotheism is the belief in the existence of one and only one god. Monotheism is characteristic of the Baha'i Faith, Christianity, Druzism, Hinduism, Islam, Judaism, Samaritanism, Sikhism and Zoroastrianism.While they profess the existence of only one deity, monotheistic religions may still...

or henotheism

Henotheism

Henotheism is the belief and worship of a single god while accepting the existence or possible existence of other deities...

). Philosophical atheist thought appears in Europe and Asia from the 6th or 5th century BCE.

Will Durant explains that certain Pygmy tribes found in Africa were observed to have no identifiable cults or rites. There were no totems, no gods, no spirits. Their dead were buried without special ceremonies or accompanying items and received no further attention. They even appeared to lack simple superstitions, according to travelers' reports. The Vedahs of Ceylon, only admitted the possibility that gods might exist, but went no further. Neither prayers nor sacrifices were suggested in any way.

Indian philosophy

In the Far East, a contemplative life not centered on the idea of gods began in the 6th century BCE with the rise of JainismJainism

Jainism is an Indian religion that prescribes a path of non-violence towards all living beings. Its philosophy and practice emphasize the necessity of self-effort to move the soul towards divine consciousness and liberation. Any soul that has conquered its own inner enemies and achieved the state...

, Buddhism

Buddhism

Buddhism is a religion and philosophy encompassing a variety of traditions, beliefs and practices, largely based on teachings attributed to Siddhartha Gautama, commonly known as the Buddha . The Buddha lived and taught in the northeastern Indian subcontinent some time between the 6th and 4th...

, and certain sects

Atheism in Hinduism

Atheism or disbelief in God or gods has been a historically propounded viewpoint in many of the orthodox and heterodox streams of Hindu philosophies...

of Hinduism

Hinduism

Hinduism is the predominant and indigenous religious tradition of the Indian Subcontinent. Hinduism is known to its followers as , amongst many other expressions...

in India, and of Taoism

Taoism

Taoism refers to a philosophical or religious tradition in which the basic concept is to establish harmony with the Tao , which is the mechanism of everything that exists...

in China.

Although these religions claim to offer a philosophic and salvific path not centering on deity worship, popular tradition in some sects of these religions has long embraced deity worship, the propitiation of spirits, and other elements of folk tradition. Furthermore, the Pali Tripiṭaka

Tripiṭaka

' is a traditional term used by various Buddhist sects to describe their various canons of scriptures. As the name suggests, a traditionally contains three "baskets" of teachings: a , a and an .-The three categories:Tripitaka is the three main categories of texts that make up the...

, the oldest complete composition of scriptures, seems to accept as real the concepts of divine beings, the Vedic

Rigvedic deities

There are 1028 hymns in the Rigveda, most of them dedicated to specific deities.Indra, a heroic god, slayer of Vrtra and destroyer of the Vala, liberator of the cows and the rivers; Agni the sacrificial fire and messenger of the gods; and Soma the ritual drink dedicated to Indra are the most...

(and other) gods, rebirth, and heaven and hell. While deities are not seen as necessary to the salvific goal of the early Buddhist tradition, their reality is not questioned.

Hinduism

Within the astika ("orthodox") schools of Hindu philosophyHindu philosophy

Hindu philosophy is divided into six schools of thought, or , which accept the Vedas as supreme revealed scriptures. Three other schools do not accept the Vedas as authoritative...

, the Samkhya

Samkhya

Samkhya, also Sankhya, Sāṃkhya, or Sāṅkhya is one of the six schools of Hindu philosophy and classical Indian philosophy. Sage Kapila is traditionally considered as the founder of the Samkhya school, although no historical verification is possible...

and the early Mimamsa

Mimamsa

' , a Sanskrit word meaning "investigation" , is the name of an astika school of Hindu philosophy whose primary enquiry is into the nature of dharma based on close hermeneutics of the Vedas...

school did not accept a creator-God in their respective systems.

The principal text of the Samkhya

Samkhya

Samkhya, also Sankhya, Sāṃkhya, or Sāṅkhya is one of the six schools of Hindu philosophy and classical Indian philosophy. Sage Kapila is traditionally considered as the founder of the Samkhya school, although no historical verification is possible...

school, the Samkhya Karika, was written by Ishvara Krishna

Ishvara Krishna

The Samkhyakarika is the earliest extant text of the Samkhya school of Indian philosophy.Dated to the Gupta era , it is attributed to Ishvarakrishna ....

in the 4th century CE, by which time it was already a dominant Hindu school. The origins of the school are much older and are lost in legend. The school was both dualistic and atheistic. They believed in a dual existence of Prakriti ("nature") and Purusha

Purusha

In some lineages of Hinduism, Purusha is the "Self" which pervades the universe. The Vedic divinities are interpretations of the many facets of Purusha...

("spirit") and had no place for an Ishvara

Ishvara

Ishvara is a philosophical concept in Hinduism, meaning controller or the Supreme controller in a theistic school of thought or the Supreme Being, or as an Ishta-deva of monistic thought.-Etymology:...

("God") in its system, arguing that the existence of Ishvara cannot be proved and hence cannot be admitted to exist. The school dominated Hindu philosophy in its day, but declined after the 10th century, although commentaries were still being written as late as the 16th century.

The foundational text for the Mimamsa school is the Purva Mimamsa Sutras

Purva Mimamsa Sutras

The Mimamsa Sutra or the Purva Mimamsa Sutras , written by Rishi Jaimini is one of the most important ancient Hindu philosophical texts. It forms the basis of Mimamsa, the earliest of the six orthodox schools of Indian philosophy...

of Jaimini (c. 3rd to 1st century BCE). The school reached its height c. 700 CE, and for some time in the Early Middle Ages

Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages was the period of European history lasting from the 5th century to approximately 1000. The Early Middle Ages followed the decline of the Western Roman Empire and preceded the High Middle Ages...

exerted near-dominant influence on learned Hindu thought. The Mimamsa school saw their primary enquiry was into the nature of dharma

Dharma

Dharma means Law or Natural Law and is a concept of central importance in Indian philosophy and religion. In the context of Hinduism, it refers to one's personal obligations, calling and duties, and a Hindu's dharma is affected by the person's age, caste, class, occupation, and gender...

based on close interpretation of the Vedas

Vedas

The Vedas are a large body of texts originating in ancient India. Composed in Vedic Sanskrit, the texts constitute the oldest layer of Sanskrit literature and the oldest scriptures of Hinduism....

. Its core tenets were ritual

Ritual

A ritual is a set of actions, performed mainly for their symbolic value. It may be prescribed by a religion or by the traditions of a community. The term usually excludes actions which are arbitrarily chosen by the performers....

ism (orthopraxy), anti-asceticism and anti-mysticism. The early Mimamsakas believed in an adrishta ("unseen") that is the result of performing karmas ("works") and saw no need for an Ishvara

Ishvara

Ishvara is a philosophical concept in Hinduism, meaning controller or the Supreme controller in a theistic school of thought or the Supreme Being, or as an Ishta-deva of monistic thought.-Etymology:...

("God") in their system. Mimamsa persists in some subschools of Hinduism today.

Jainism

Jains see their tradition as eternal, Jainism has prehistoric origins dating before 3000 BCE, and before the beginning ofIndo-Aryan culture. Organized Jainism

Jainism

Jainism is an Indian religion that prescribes a path of non-violence towards all living beings. Its philosophy and practice emphasize the necessity of self-effort to move the soul towards divine consciousness and liberation. Any soul that has conquered its own inner enemies and achieved the state...

can be dated back to Parshva

Parshva

Pārśva or Paras was the twenty-third Tirthankara "Ford-Maker" in Jainism . He is the earliest Jain leader generally accepted as a historical figure. Pārśva was a nobleman belonging to the Kshatriya varna....

who lived in the 9th century BCE, and, more reliably, to Mahavira

Mahavira

Mahāvīra is the name most commonly used to refer to the Indian sage Vardhamāna who established what are today considered to be the central tenets of Jainism. According to Jain tradition, he was the 24th and the last Tirthankara. In Tamil, he is referred to as Arukaṉ or Arukadevan...

, a teacher of the 6th century BCE, and a contemporary of the Buddha

Gautama Buddha

Siddhārtha Gautama was a spiritual teacher from the Indian subcontinent, on whose teachings Buddhism was founded. In most Buddhist traditions, he is regarded as the Supreme Buddha Siddhārtha Gautama (Sanskrit: सिद्धार्थ गौतम; Pali: Siddhattha Gotama) was a spiritual teacher from the Indian...

. Jainism is a dualistic religion with the universe

Universe

The Universe is commonly defined as the totality of everything that exists, including all matter and energy, the planets, stars, galaxies, and the contents of intergalactic space. Definitions and usage vary and similar terms include the cosmos, the world and nature...

made up of matter

Matter

Matter is a general term for the substance of which all physical objects consist. Typically, matter includes atoms and other particles which have mass. A common way of defining matter is as anything that has mass and occupies volume...

and souls. The universe, and the matter and souls within it, is eternal and uncreated, and there is no omnipotent creator god in Jainism. There are, however, "gods" and other spirits who exist within the universe and Jains believe that the soul can attain "godhood", however none of these supernatural beings exercise any sort of creative activity or have the capacity or ability to intervene in answers to prayers.

Cārvāka

The thoroughly materialistic and anti-religious philosophical CārvākaCarvaka

' , also known as ', is a system of Indian philosophy that assumes various forms of philosophical skepticism and religious indifference. It seems named after , the probable author of the and probably a follower of Brihaspati, who founded the ' philosophy.In overviews of Indian philosophy, Cārvāka...

school that originated in India

India

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

with the Bārhaspatya-sūtras (final centuries BCE) is probably the most explicitly atheist school of philosophy in the region. The school grew out of the generic skepticism in the Mauryan period. Already in the 6th century BCE, Ajita Kesakambalin, was quoted in Pali scriptures by the Buddhists with whom he was debating, teaching that "with the break-up of the body, the wise and the foolish alike are annihilated, destroyed. They do not exist after death."

Cārvākan philosophy is now known principally from its Astika and Buddhist opponents. The proper aim of a Cārvākan, according to these sources, was to live a prosperous, happy, productive life in this world. The Tattvopaplavasimha of Jayarashi Bhatta (c. 8th century) is sometimes cited as a surviving Carvaka text. The school appears to have died out sometime around the 15th century.

Buddhism

The refutation of the notion of a supreme GodGod

God is the English name given to a singular being in theistic and deistic religions who is either the sole deity in monotheism, or a single deity in polytheism....

or a prime mover

Primum movens

Primum movens , usually referred to as the Prime mover or first cause in English, is a term used in the philosophy of Aristotle, in the theological cosmological argument for the existence of God, and in cosmogony, the source of the cosmos or "all-being".-Aristotle's ontology:In book 12 of his...

is seen by many as a key distinction between Buddhism

Buddhism

Buddhism is a religion and philosophy encompassing a variety of traditions, beliefs and practices, largely based on teachings attributed to Siddhartha Gautama, commonly known as the Buddha . The Buddha lived and taught in the northeastern Indian subcontinent some time between the 6th and 4th...

and other religions. While Buddhist traditions do not deny the existence of supernatural beings (many are discussed in Buddhist scripture), it does not ascribe powers, in the typical Western sense, for creation, salvation or judgement, to the "gods".

Buddhists accept the existence of beings in higher realms (see Buddhist cosmology

Buddhist cosmology

Buddhist cosmology is the description of the shape and evolution of the Universe according to the canonical Buddhist scriptures and commentaries.-Introduction:...

), known as devas

Deva (Buddhism)

A deva in Buddhism is one of many different types of non-human beings who share the characteristics of being more powerful, longer-lived, and, in general, living more contentedly than the average human being....

, but they, like humans, are said to be suffering in samsara

Samsara (Buddhism)

or sangsara is a Sanskrit and Pāli term, which translates as "continuous movement" or "continuous flowing" and, in Buddhism, refers to the concept of a cycle of birth , and consequent decay and death , in which all beings in the universe participate, and which can only be escaped through...

, and not particularly wiser than us. In fact the Buddha is often portrayed as a teacher of the gods, and superior to them.

Classical Greece and Rome

Classical antiquity

Classical antiquity is a broad term for a long period of cultural history centered on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ancient Greece and ancient Rome, collectively known as the Greco-Roman world...

, theism was the fundamental belief that supported the divine right of the State (Polis

Polis

Polis , plural poleis , literally means city in Greek. It could also mean citizenship and body of citizens. In modern historiography "polis" is normally used to indicate the ancient Greek city-states, like Classical Athens and its contemporaries, so polis is often translated as "city-state."The...

, later the Roman Empire

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

). Historically, any person who did not believe in any deity supported by the State was fair game to accusations of atheism, a capital crime

Capital punishment

Capital punishment, the death penalty, or execution is the sentence of death upon a person by the state as a punishment for an offence. Crimes that can result in a death penalty are known as capital crimes or capital offences. The term capital originates from the Latin capitalis, literally...

. For political reasons, Socrates

Socrates

Socrates was a classical Greek Athenian philosopher. Credited as one of the founders of Western philosophy, he is an enigmatic figure known chiefly through the accounts of later classical writers, especially the writings of his students Plato and Xenophon, and the plays of his contemporary ...

in Athens

Athens

Athens , is the capital and largest city of Greece. Athens dominates the Attica region and is one of the world's oldest cities, as its recorded history spans around 3,400 years. Classical Athens was a powerful city-state...

(399 BCE) was accused of being 'atheos' ("refusing to acknowledge the gods recognized by the state"). Despite the charges, he claimed inspiration from a divine voice (Daimon

Daemon (mythology)

The words dæmon and daimôn are Latinized spellings of the Greek "δαίμων", a reference to the daemons of Ancient Greek religion and mythology, as well as later Hellenistic religion and philosophy...

). Christians in Rome were also considered subversive to the state religion and persecuted as atheists. Thus, charges of atheism, meaning the subversion of religion, were often used similarly to charges of heresy

Heresy

Heresy is a controversial or novel change to a system of beliefs, especially a religion, that conflicts with established dogma. It is distinct from apostasy, which is the formal denunciation of one's religion, principles or cause, and blasphemy, which is irreverence toward religion...

and impiety

Impiety

Impiety is classically a lack of proper concern for the obligations owed to public religious observation or cult. Impiety was a main Pagan objection to Christianity, for unlike other initiates into mystery religions, early Christians refused to cast a pinch of incense before the images of the gods,...

– as a political tool to eliminate enemies.

Presocratic philosophy

Western philosophyWestern philosophy

Western philosophy is the philosophical thought and work of the Western or Occidental world, as distinct from Eastern or Oriental philosophies and the varieties of indigenous philosophies....

began in the Greek world in the 6th century BCE. The first philosophers were not atheists, but they attempted to explain the world in terms of the processes of nature instead of by mythological accounts. Thus lightning

Lightning

Lightning is an atmospheric electrostatic discharge accompanied by thunder, which typically occurs during thunderstorms, and sometimes during volcanic eruptions or dust storms...

was the result of "wind breaking out and parting the clouds," and earthquake

Earthquake

An earthquake is the result of a sudden release of energy in the Earth's crust that creates seismic waves. The seismicity, seismism or seismic activity of an area refers to the frequency, type and size of earthquakes experienced over a period of time...

s occurred when "the earth is considerably altered by heating and cooling." The early philosophers often criticised traditional religious notions. Xenophanes

Xenophanes

of Colophon was a Greek philosopher, theologian, poet, and social and religious critic. Xenophanes life was one of travel, having left Ionia at the age of 25 he continued to travel throughout the Greek world for another 67 years. Some scholars say he lived in exile in Siciliy...

(6th century BCE) famously said that if cows and horses had hands, "then horses would draw the forms of gods like horses, and cows like cows." Another philosopher, Anaxagoras

Anaxagoras

Anaxagoras was a Pre-Socratic Greek philosopher. Born in Clazomenae in Asia Minor, Anaxagoras was the first philosopher to bring philosophy from Ionia to Athens. He attempted to give a scientific account of eclipses, meteors, rainbows, and the sun, which he described as a fiery mass larger than...

(5th century BCE), claimed that the Sun

Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is almost perfectly spherical and consists of hot plasma interwoven with magnetic fields...

was "a fiery mass, larger than the Peloponnese

Peloponnese

The Peloponnese, Peloponnesos or Peloponnesus , is a large peninsula , located in a region of southern Greece, forming the part of the country south of the Gulf of Corinth...

;" a charge of impiety was brought against him, and he was forced to flee Athens

Athens

Athens , is the capital and largest city of Greece. Athens dominates the Attica region and is one of the world's oldest cities, as its recorded history spans around 3,400 years. Classical Athens was a powerful city-state...

.

The first fully materialistic philosophy was produced by the Atomists

Atomism

Atomism is a natural philosophy that developed in several ancient traditions. The atomists theorized that the natural world consists of two fundamental parts: indivisible atoms and empty void.According to Aristotle, atoms are indestructible and immutable and there are an infinite variety of shapes...

, Leucippus

Leucippus

Leucippus or Leukippos was one of the earliest Greeks to develop the theory of atomism — the idea that everything is composed entirely of various imperishable, indivisible elements called atoms — which was elaborated in greater detail by his pupil and successor, Democritus...

and Democritus

Democritus

Democritus was an Ancient Greek philosopher born in Abdera, Thrace, Greece. He was an influential pre-Socratic philosopher and pupil of Leucippus, who formulated an atomic theory for the cosmos....

(5th century BCE), who attempted to explain the formation and development of the world in terms of the chance movements of atom

Atom

The atom is a basic unit of matter that consists of a dense central nucleus surrounded by a cloud of negatively charged electrons. The atomic nucleus contains a mix of positively charged protons and electrically neutral neutrons...

s moving in infinite space.

Euripides

Euripides

Euripides was one of the three great tragedians of classical Athens, the other two being Aeschylus and Sophocles. Some ancient scholars attributed ninety-five plays to him but according to the Suda it was ninety-two at most...

(480–406 BCE), in his play Bellerophon

Bellerophon (play)

Bellerophon is an ancient Greek tragedy written by Euripides, based upon the myth of Bellerophon. Most of the play was lost by the end of the Antiquity, and only 90 verses, grouped into 29 fragments, currently survive....

, had the eponymous main character say:

“Doth some one say that there be gods above?

There are not; no, there are not. Let no fool,

Led by the old false fable, thus deceive you.”

Aristophanes

Aristophanes

Aristophanes , son of Philippus, of the deme Cydathenaus, was a comic playwright of ancient Athens. Eleven of his forty plays survive virtually complete...

(ca. 448–380 BCE), known for his satirical style, said in his The Knights

The Knights

The Knights was the fourth play written by Aristophanes, the master of an ancient form of drama known as Old Comedy. The play is a satire on the social and political life of classical Athens during the Peloponnesian War and in this respect it is typical of all the dramatist's early plays...

play:

"Shrines! Shrines! Surely you don't believe in the gods. What's your argument? Where's your proof?"

The Sophists

In the 5th century BCE the Sophists began to question many of the traditional assumptions of Greek culture. Prodicus of Ceos was said to have believed that "it was the things which were serviceable to human life that had been regarded as gods," and ProtagorasProtagoras

Protagoras was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher and is numbered as one of the sophists by Plato. In his dialogue Protagoras, Plato credits him with having invented the role of the professional sophist or teacher of virtue...

stated at the beginning of a book that "With regard to the gods I am unable to say either that they exist or do not exist."

Diagoras of Melos

Diagoras of Melos

Diagoras "the Atheist" of Melos was a Greek poet and sophist of the 5th century BCE. Throughout antiquity he was regarded as an atheist. With the exception of this one point, there is little information concerning his life and beliefs. He spoke out against the Greek religion, and criticized the...

(5th century BCE) is known as the "first atheist". He blasphemed by making public the Eleusinian Mysteries

Eleusinian Mysteries

The Eleusinian Mysteries were initiation ceremonies held every year for the cult of Demeter and Persephone based at Eleusis in ancient Greece. Of all the mysteries celebrated in ancient times, these were held to be the ones of greatest importance...

and discouraging people from being initiated. Somewhat later (c. 300 BCE), the Cyrenaic philosopher Theodorus of Cyrene

Theodorus the Atheist

Theodorus the Atheist, of Cyrene, was a philosopher of the Cyrenaic school. He lived in both Greece and Alexandria, before ending his days in his native city of Cyrene. As a Cyrenaic philosopher, he taught that the goal of life was to obtain joy and avoid grief, and that the former resulted from...

is supposed to have denied that gods exist, and wrote a book On the Gods expounding his views.

Euhemerus

Euhemerus

Euhemerus was a Greek mythographer at the court of Cassander, the king of Macedon. Euhemerus' birthplace is disputed, with Messina in Sicily as the most probable location, while others champion Chios, or Tegea.-Life:...

(c. 330–260 BCE) published his view that the gods were only the deified rulers, conquerors and founders of the past, and that their cults and religions were in essence the continuation of vanished kingdoms and earlier political structures. Although Euhemerus was later criticized for having "spread atheism over the whole inhabited earth by obliterating the gods", his worldview was not atheist in a strict and theoretical sense, because he differentiated that the primordial gods were "eternal and imperishable". Some historians have argued that he merely aimed at reinventing the old religions in the light of the beginning deification of political rulers such as Alexander the Great. Euhemerus' work was translated into Latin by Ennius

Ennius

Quintus Ennius was a writer during the period of the Roman Republic, and is often considered the father of Roman poetry. He was of Calabrian descent...

, possibly to mythographically

Mythography

A mythographer, or a mythologist is a compiler of myths. The word derives from the Greek "μυθογραφία" , "writing of fables", from "μῦθος" , "speech, word, fact, story, narrative" + "γράφω" , "to write, to inscribe". Mythography is then the rendering of myths in the arts...

pave the way for the planned divinization

Apotheosis

Apotheosis is the glorification of a subject to divine level. The term has meanings in theology, where it refers to a belief, and in art, where it refers to a genre.In theology, the term apotheosis refers to the idea that an individual has been raised to godlike stature...

of Scipio Africanus

Scipio Africanus

Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus , also known as Scipio Africanus and Scipio the Elder, was a general in the Second Punic War and statesman of the Roman Republic...

in Rome.

Epicureanism

Also important in the history of atheism was EpicurusEpicurus

Epicurus was an ancient Greek philosopher and the founder of the school of philosophy called Epicureanism.Only a few fragments and letters remain of Epicurus's 300 written works...

(c. 300 BCE). Drawing on the ideas of Democritus

Democritus

Democritus was an Ancient Greek philosopher born in Abdera, Thrace, Greece. He was an influential pre-Socratic philosopher and pupil of Leucippus, who formulated an atomic theory for the cosmos....

and the Atomists

Atomism

Atomism is a natural philosophy that developed in several ancient traditions. The atomists theorized that the natural world consists of two fundamental parts: indivisible atoms and empty void.According to Aristotle, atoms are indestructible and immutable and there are an infinite variety of shapes...

, he espoused a materialistic philosophy where the universe was governed by the laws of chance without the need for divine intervention. Although he stated that the gods existed, he believed that they were uninterested in human existence. The aim of the Epicureans was to attain peace of mind by exposing fear of divine wrath as irrational. One of the most eloquent expression of Epicurean thought is Lucretius

Lucretius

Titus Lucretius Carus was a Roman poet and philosopher. His only known work is an epic philosophical poem laying out the beliefs of Epicureanism, De rerum natura, translated into English as On the Nature of Things or "On the Nature of the Universe".Virtually no details have come down concerning...

' On the Nature of Things

On the Nature of Things

De rerum natura is a 1st century BC didactic poem by the Roman poet and philosopher Lucretius with the goal of explaining Epicurean philosophy to a Roman audience. The poem, written in some 7,400 dactylic hexameters, is divided into six untitled books, and explores Epicurean physics through richly...

(1st century BCE). Lucretius declared "There is no God". The Epicureans also denied the existence of an afterlife. Epicureans were not persecuted, but their teachings were controversial, and were harshly attacked by the mainstream schools of Stoicism

Stoicism

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy founded in Athens by Zeno of Citium in the early . The Stoics taught that destructive emotions resulted from errors in judgment, and that a sage, or person of "moral and intellectual perfection," would not suffer such emotions.Stoics were concerned...

and Neoplatonism

Neoplatonism

Neoplatonism , is the modern term for a school of religious and mystical philosophy that took shape in the 3rd century AD, based on the teachings of Plato and earlier Platonists, with its earliest contributor believed to be Plotinus, and his teacher Ammonius Saccas...

. The movement remained marginal, and gradually died out at the end of the Roman Empire

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

.

Others

CiceroCicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero , was a Roman philosopher, statesman, lawyer, political theorist, and Roman constitutionalist. He came from a wealthy municipal family of the equestrian order, and is widely considered one of Rome's greatest orators and prose stylists.He introduced the Romans to the chief...

(ca. 106–43 BCE) declared:

"In this subject of the nature of the gods the first question is: do the gods exist or do they not? It is difficult, you will say, to deny that they exist. I would agree, if we were arguing the matter in a public assembly, but in a private discussion of this kind it is perfectly easy to do so."

Ancient Levant

The concept of atheism was apparently known to the ancient JewsJews

The Jews , also known as the Jewish people, are a nation and ethnoreligious group originating in the Israelites or Hebrews of the Ancient Near East. The Jewish ethnicity, nationality, and religion are strongly interrelated, as Judaism is the traditional faith of the Jewish nation...

and viewed negatively by the authors of the Biblical texts. Psalm 14:1–3 reads "The fool says in his heart 'There is no God.' They are corrupt, their deeds are vile; there is no one who does good.".

The Middle Ages

In medieval IslamIslam

Islam . The most common are and . : Arabic pronunciation varies regionally. The first vowel ranges from ~~. The second vowel ranges from ~~~...

, scholars recognized the idea of atheism, and frequently attacked unbelievers

Kafir

Kafir is an Arabic term used in a Islamic doctrinal sense, usually translated as "unbeliever" or "disbeliever"...

, although they were unable to name any actual atheists. When individuals were accused of atheism, they were usually viewed as heretics rather than proponents of atheism.

One notable figure was the 9th century scholar Ibn al-Rawandi

Ibn al-Rawandi

Abu al-Hasan Ahmad ibn Yahya ibn Ishaq al-Rawandi , commonly known as Ibn al-Rawandi , was an early skeptic of Islam and a critic of religion in general. In his early days he was a Mutazilite scholar, but after rejecting the Mutazilite doctrine he adhered to Shia Islam for a brief period of time...

who criticized the notion of religious prophecy

Prophecy

Prophecy is a process in which one or more messages that have been communicated to a prophet are then communicated to others. Such messages typically involve divine inspiration, interpretation, or revelation of conditioned events to come as well as testimonies or repeated revelations that the...

including that of Muhammad

Muhammad

Muhammad |ligature]] at U+FDF4 ;Arabic pronunciation varies regionally; the first vowel ranges from ~~; the second and the last vowel: ~~~. There are dialects which have no stress. In Egypt, it is pronounced not in religious contexts...

, and maintained that religious dogmas were not acceptable to reason and must be rejected. Other critics of religion in the Islamic world include the physician and philosopher Abu Bakr al-Razi (865–925), and the poet Al-Ma`arri (973–1057).

In the European Middle Ages

Middle Ages

The Middle Ages is a periodization of European history from the 5th century to the 15th century. The Middle Ages follows the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 and precedes the Early Modern Era. It is the middle period of a three-period division of Western history: Classic, Medieval and Modern...

, no clear expression of atheism is known. The titular character of the Icelandic saga Hrafnkell, written in the late 13th century, says that I think it is folly to have faith in gods. After his temple to Freyr is burnt and he is enslaved he vows never to perform another sacrifice

Blót

The blót was Norse pagan sacrifice to the Norse gods and the spirits of the land. The sacrifice often took the form of a sacramental meal or feast. Related religious practices were performed by other Germanic peoples, such as the pagan Anglo-Saxons...

, a position described in the sagas as goðlauss "godless". Jacob Grimm

Jacob Grimm

Jacob Ludwig Carl Grimm was a German philologist, jurist and mythologist. He is best known as the discoverer of Grimm's Law, the author of the monumental Deutsches Wörterbuch, the author of Deutsche Mythologie and, more popularly, as one of the Brothers Grimm, as the editor of Grimm's Fairy...

in his Teutonic Mythology observes that

It is remarkable that Old Norse legend occasionally mentions certain men who, turning away in utter disgust and doubt from the heathen faith, placed their reliance on their own strength and virtue. Thus in the Sôlar lioð 17 we read of Vêbogi and Râdey â sik þau trûðu, "in themselves they trusted",

citing several other examples, including two kings.

In Christian Europe, people were persecuted for heresy, especially in countries where the Inquisition

Inquisition

The Inquisition, Inquisitio Haereticae Pravitatis , was the "fight against heretics" by several institutions within the justice-system of the Roman Catholic Church. It started in the 12th century, with the introduction of torture in the persecution of heresy...

was active. However, Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, O.P. , also Thomas of Aquin or Aquino, was an Italian Dominican priest of the Catholic Church, and an immensely influential philosopher and theologian in the tradition of scholasticism, known as Doctor Angelicus, Doctor Communis, or Doctor Universalis...

' five proofs of God's existence

Quinquae viae

The Quinque viæ, Five Ways, or Five Proofs are five arguments regarding the existence of God summarized by the 13th century Roman Catholic philosopher and theologian St. Thomas Aquinas in his book, Summa Theologica...

and Anselm

Anselm of Canterbury

Anselm of Canterbury , also called of Aosta for his birthplace, and of Bec for his home monastery, was a Benedictine monk, a philosopher, and a prelate of the church who held the office of Archbishop of Canterbury from 1093 to 1109...

's ontological argument

Ontological argument

The ontological argument for the existence of God is an a priori argument for the existence of God. The ontological argument was first proposed by the eleventh-century monk Anselm of Canterbury, who defined God as the greatest possible being we can conceive...

implicitly acknowledged the validity of the question about god's existence. The charge of atheism was used as way of attacking one's political or religious enemies. Pope Boniface VIII

Pope Boniface VIII

Pope Boniface VIII , born Benedetto Gaetani, was Pope of the Catholic Church from 1294 to 1303. Today, Boniface VIII is probably best remembered for his feuds with Dante, who placed him in the Eighth circle of Hell in his Divina Commedia, among the Simonists.- Biography :Gaetani was born in 1235 in...

, because he insisted on the political supremacy of the church, was accused by his enemies after his death of holding (unlikely) atheistic positions such as "neither believing in the immortality nor incorruptibility of the soul, nor in a life to come."

Renaissance and Reformation

During the time of the RenaissanceRenaissance

The Renaissance was a cultural movement that spanned roughly the 14th to the 17th century, beginning in Italy in the Late Middle Ages and later spreading to the rest of Europe. The term is also used more loosely to refer to the historical era, but since the changes of the Renaissance were not...

and the Reformation

Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation was a 16th-century split within Western Christianity initiated by Martin Luther, John Calvin and other early Protestants. The efforts of the self-described "reformers", who objected to the doctrines, rituals and ecclesiastical structure of the Roman Catholic Church, led...

, criticism of the religious establishment became more frequent in predominantly Christian countries, but did not amount to actual atheism.

The term athéisme was coined in France in the 16th century. The word "atheist" appears in English books at least as early as 1566.

The concept of atheism re-emerged initially as a reaction to the intellectual and religious turmoil of the Age of Enlightenment

Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment was an elite cultural movement of intellectuals in 18th century Europe that sought to mobilize the power of reason in order to reform society and advance knowledge. It promoted intellectual interchange and opposed intolerance and abuses in church and state...

and the Reformation – as a charge used by those who saw the denial of god and godlessness in the controversial positions being put forward by others. During the 16th and 17th centuries, the word 'atheist' was used exclusively as an insult; nobody wanted to be regarded as an atheist. Although one overtly atheistic compendium known as the Theophrastus redivivus

Theophrastus redivivus

Theophrastus redivivus is an anonymous book published in 1659. The book has been described as "a compendium of old arguments against religion and belief in God" and "an anthology of free thought." It comprises materialist and skeptical treatises from classical sources as Pietro Pomponazzi, Lucilio...

was published by an anonymous author in the 17th century, atheism was an epithet implying a lack of moral restraint

Libertine

A libertine is one devoid of most moral restraints, which are seen as unnecessary or undesirable, especially one who ignores or even spurns accepted morals and forms of behavior sanctified by the larger society. Libertines, also known as rakes, placed value on physical pleasures, meaning those...

. How dangerous it was to be accused of being an atheist at this time is illustrated by the examples of Étienne Dolet

Étienne Dolet

Étienne Dolet was a French scholar, translator and printer.-Early life:He was born in Orléans. A doubtful tradition makes him the illegitimate son of Francis I; but it is evident that he was at least connected with some family of rank and wealth.From Orléans he was taken to Paris about 1521, and...

who was strangled

Strangling

Strangling is compression of the neck that may lead to unconsciousness or death by causing an increasingly hypoxic state in the brain. Fatal strangling typically occurs in cases of violence, accidents, and as the auxiliary lethal mechanism in hangings in the event the neck does not break...

and burned in 1546, and Giulio Cesare Vanini who received a similar fate in 1619. In 1689 the Polish nobleman Kazimierz Łyszczyński, who had allegedly denied the existence of God in his philosophical treatise De non existentia Dei, was condemned to death in Warsaw

Warsaw

Warsaw is the capital and largest city of Poland. It is located on the Vistula River, roughly from the Baltic Sea and from the Carpathian Mountains. Its population in 2010 was estimated at 1,716,855 residents with a greater metropolitan area of 2,631,902 residents, making Warsaw the 10th most...

for atheism and beheaded after his tongue was pulled out with a burning iron and his hands slowly burned. Similarly in 1766, the French nobleman Jean-François de la Barre

Jean-François de la Barre

Jean-François Lefevre de la Barre was a French nobleman, famous for having been tortured and beheaded before his body was burnt on a pyre along with Voltaire's "Philosophical Dictionary". He is often said to have been executed for not saluting a procession, but the elements of the case were far...

, was torture

Torture

Torture is the act of inflicting severe pain as a means of punishment, revenge, forcing information or a confession, or simply as an act of cruelty. Throughout history, torture has often been used as a method of political re-education, interrogation, punishment, and coercion...

d, beheaded, and his body burned for alleged vandalism

Vandalism

Vandalism is the behaviour attributed originally to the Vandals, by the Romans, in respect of culture: ruthless destruction or spoiling of anything beautiful or venerable...

of a crucifix

Crucifix

A crucifix is an independent image of Jesus on the cross with a representation of Jesus' body, referred to in English as the corpus , as distinct from a cross with no body....

, a case that became celebrated because Voltaire

Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet , better known by the pen name Voltaire , was a French Enlightenment writer, historian and philosopher famous for his wit and for his advocacy of civil liberties, including freedom of religion, free trade and separation of church and state...

tried unsuccessfully to have the sentence reversed.

Among those accused of atheism was Denis Diderot

Denis Diderot

Denis Diderot was a French philosopher, art critic, and writer. He was a prominent person during the Enlightenment and is best known for serving as co-founder and chief editor of and contributor to the Encyclopédie....

(1713–1784), one of the Enlightenment's most prominent philosophes, and editor-in-chief of the Encyclopédie

Encyclopédie

Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers was a general encyclopedia published in France between 1751 and 1772, with later supplements, revised editions, and translations. It was edited by Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d'Alembert...

, which sought to challenge religious, particularly Catholic

Catholicism

Catholicism is a broad term for the body of the Catholic faith, its theologies and doctrines, its liturgical, ethical, spiritual, and behavioral characteristics, as well as a religious people as a whole....

, dogma: "Reason is to the estimation of the philosophe what grace is to the Christian", he wrote. "Grace determines the Christian's action; reason the philosophe's". Diderot was briefly imprisoned for his writing, some of which was banned and burned.

The English materialist philosopher Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes of Malmesbury , in some older texts Thomas Hobbs of Malmsbury, was an English philosopher, best known today for his work on political philosophy...

(1588–1679) was also accused of atheism, but he denied it. His theism was unusual, in that he held god to be material. Even earlier, the British playwright and poet, Christopher Marlowe

Christopher Marlowe

Christopher Marlowe was an English dramatist, poet and translator of the Elizabethan era. As the foremost Elizabethan tragedian, next to William Shakespeare, he is known for his blank verse, his overreaching protagonists, and his mysterious death.A warrant was issued for Marlowe's arrest on 18 May...

(1563–1593), was accused of atheism when a tract denying the divinity of Christ was found in his home. Before he could finish defending himself against the charge, Marlowe was murdered, although this was not related to the religious issue.

The Age of Enlightenment

By the 1770s, atheism in some predominantly Christian countries was ceasing to be a dangerous accusation that required denial, and was evolving into a position openly avowed by some. The first open denial of the existence of god and avowal of atheism since classical times may be that of Paul Baron d'HolbachBaron d'Holbach

Paul-Henri Thiry, Baron d'Holbach was a French-German author, philosopher, encyclopedist and a prominent figure in the French Enlightenment. He was born Paul Heinrich Dietrich in Edesheim, near Landau in the Rhenish Palatinate, but lived and worked mainly in Paris, where he kept a salon...

(1723–1789) in his 1770 work, The System of Nature

The System of Nature

The System of Nature or, the Laws of the Moral and Physical World is a work of philosophy by Paul Henri Thiry, Baron d'Holbach . It was originally published under the name of Jean-Baptiste de Mirabaud, a deceased member of the French Academy of Science...

. D'Holbach was a Parisian social figure who conducted a famous salon widely attended by many intellectual notables of the day, including Denis Diderot

Denis Diderot

Denis Diderot was a French philosopher, art critic, and writer. He was a prominent person during the Enlightenment and is best known for serving as co-founder and chief editor of and contributor to the Encyclopédie....

, Jean Jacques Rousseau, David Hume

David Hume

David Hume was a Scottish philosopher, historian, economist, and essayist, known especially for his philosophical empiricism and skepticism. He was one of the most important figures in the history of Western philosophy and the Scottish Enlightenment...

, Adam Smith

Adam Smith

Adam Smith was a Scottish social philosopher and a pioneer of political economy. One of the key figures of the Scottish Enlightenment, Smith is the author of The Theory of Moral Sentiments and An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations...

, and Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin

Dr. Benjamin Franklin was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. A noted polymath, Franklin was a leading author, printer, political theorist, politician, postmaster, scientist, musician, inventor, satirist, civic activist, statesman, and diplomat...

. Nevertheless, his book was published under a pseudonym, and was banned and publicly burned by the Executioner

Executioner

A judicial executioner is a person who carries out a death sentence ordered by the state or other legal authority, which was known in feudal terminology as high justice.-Scope and job:...

.

The Cult of Reason

Cult of Reason

The Cult of Reason was an atheistic belief system established in France and intended as a replacement for Christianity during the French Revolution.-Origins:...

was a creed based on atheism devised during the French Revolution

French Revolution

The French Revolution , sometimes distinguished as the 'Great French Revolution' , was a period of radical social and political upheaval in France and Europe. The absolute monarchy that had ruled France for centuries collapsed in three years...

by Jacques Hébert

Jacques Hébert

Jacques René Hébert was a French journalist, and the founder and editor of the extreme radical newspaper Le Père Duchesne during the French Revolution...

, Pierre Gaspard Chaumette

Pierre Gaspard Chaumette

Pierre Gaspard Chaumette was a French politician of the Revolutionaryperiod.-Early activities:Born in Nevers France, 24 May 1763, his main interest was botany and science. Chaumette studied medicine at the University of Paris in 1790, but gave up his career in medicine at the start of the Revolution...

and their supporters. It was stopped by Maximilien Robespierre

Maximilien Robespierre

Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre is one of the best-known and most influential figures of the French Revolution. He largely dominated the Committee of Public Safety and was instrumental in the period of the Revolution commonly known as the Reign of Terror, which ended with his...

, a Deist, who instituted the Cult of the Supreme Being

Cult of the Supreme Being

The Cult of the Supreme Being was a form of deism established in France by Maximilien Robespierre during the French Revolution. It was intended to become the state religion of the new French Republic.- Origins :...

. Both cults were the outcome of the "de-Christianization" of French society

Dechristianisation of France during the French Revolution

The dechristianisation of France during the French Revolution is a conventional description of the results of a number of separate policies, conducted by various governments of France between the start of the French Revolution in 1789 and the Concordat of 1801, forming the basis of the later and...

during the Revolution and part of the Reign of Terror

Reign of Terror