History of Yemen

Encyclopedia

Yemen

The Republic of Yemen , commonly known as Yemen , is a country located in the Middle East, occupying the southwestern to southern end of the Arabian Peninsula. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to the north, the Red Sea to the west, and Oman to the east....

is one of the oldest centers of civilization

Civilization

Civilization is a sometimes controversial term that has been used in several related ways. Primarily, the term has been used to refer to the material and instrumental side of human cultures that are complex in terms of technology, science, and division of labor. Such civilizations are generally...

in the Near East

Near East

The Near East is a geographical term that covers different countries for geographers, archeologists, and historians, on the one hand, and for political scientists, economists, and journalists, on the other...

. Its relatively fertile land and adequate rainfall in a moister climate helped sustain a stable population, a feature recognized by the ancient Greek geographer Ptolemy

Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy , was a Roman citizen of Egypt who wrote in Greek. He was a mathematician, astronomer, geographer, astrologer, and poet of a single epigram in the Greek Anthology. He lived in Egypt under Roman rule, and is believed to have been born in the town of Ptolemais Hermiou in the...

, who described Yemen as Eudaimon Arabia (better known in its Latin translation, Arabia Felix) meaning "fortunate Arabia" or Happy Arabia. Between the 12th century BCE and the 6th century CE, it was dominated by six successive civilizations which rivaled each other, or were allied with each other and controlled the lucrative spice trade

Spice trade

Civilizations of Asia were involved in spice trade from the ancient times, and the Greco-Roman world soon followed by trading along the Incense route and the Roman-India routes...

: M'ain, Qataban

Qataban

Qataban was one of the ancient Yemeni kingdoms. Its heartland was located in the Baihan valley. Like some other Southern Arabian kingdoms it gained great wealth from the trade of frankincense and myrrh incense which were burned at altars...

, Hadhramaut

Hadhramaut

Hadhramaut, Hadhramout, Hadramawt or Ḥaḍramūt is the formerly independent Qu'aiti state and sultanate encompassing a historical region of the south Arabian Peninsula along the Gulf of Aden in the Arabian Sea, extending eastwards from Yemen to the borders of the Dhofar region of Oman...

, Awsan, Saba

Sheba

Sheba was a kingdom mentioned in the Jewish scriptures and the Qur'an...

and Himyarite. Islam arrived in 630 CE, and Yemen became part of the Muslim realm.

The Yemeni desert regions (Rub' al Khali and Sayhad

Sayhad

Sayhad is a desert region that corresponds with Northern Deserts of Modern Yemen and Southwestern Saudi Arabia ....

) were the core settlements of the Nomadic Semites that would migrate to the North, settling Akkad

Akkad

The Akkadian Empire was an empire centered in the city of Akkad and its surrounding region in Mesopotamia....

, later penetrating Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a toponym for the area of the Tigris–Euphrates river system, largely corresponding to modern-day Iraq, northeastern Syria, southeastern Turkey and southwestern Iran.Widely considered to be the cradle of civilization, Bronze Age Mesopotamia included Sumer and the...

, eventually conquering Sumer

Sumer

Sumer was a civilization and historical region in southern Mesopotamia, modern Iraq during the Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age....

by 2300 BCE, and assimilating the Amorites of Syria.

Some scholars believe that Yemen remains the only region in the world that is exclusively Semitic

Semitic

In linguistics and ethnology, Semitic was first used to refer to a language family of largely Middle Eastern origin, now called the Semitic languages...

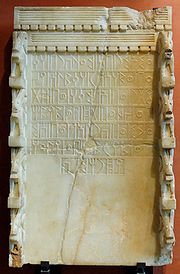

, meaning that Yemen historically did not have any non–Semitic-speaking people. Yemeni Semites derived their Musnad

South Arabian alphabet

The ancient Yemeni alphabet branched from the Proto-Sinaitic alphabet in about the 9th century BC. It was used for writing the Yemeni Old South Arabic languages of the Sabaean, Qatabanian, Hadramautic, Minaean, Himyarite, and proto-Ge'ez in Dʿmt...

script by the 12th to 8th centuries BCE, which explains why most historians date all of the ancient Yemeni kingdoms to the 12th to 8th centuries BCE.

Prehistory

According to Arab tradition, the Semites of South Arabia integrated into Qahtan lineage 40 generations before the Qahtani Yemeni tribe of JurhumJurhum

Jurhum was a Qahtani tribe in the Arabian peninsula. An old Arab tribe, their historical abode was Yemen before they emigrated to Mecca....

adopted Ismail

Ismail

Ismail may refer to:*Ismail , people with the name*Ishmael, the English name of Ismail*Ismael Village, in Sangcharak District at Sar-e Pol Province of Afghanistan...

and 80 generations before Adnan was born, in the 23rd century BCE. After the fall of the Northern Semitic cultures, Qahtan revived the Semitic influence in the North through the famous Kahlan

Kahlan

Kahlan was one of the main tribal federations of Saba'a in Yemen.-Conflict with Himyar:By the 1st century BC Saba'a was declining gradually and its southern neighbor Himyar was able to settle many Nomadic tribes that was allied to Saba'a and create a stronger Himyarite nation in the lowlands...

(Azd

Azd

The Azd or Al Azd, are an Arabian tribe. They were a branch of the Kahlan tribe, which was one of the two branches of Qahtan the other being Himyar.In the ancient times, they inhabited Ma'rib, the capital city of the Sabaean Kingdom in modern-day Yemen...

and Lakhm) and other Yemenite tribes migration into the North during the 3rd century CE after the first destruction of the Marib Dam. The Horn of Africa

Horn of Africa

The Horn of Africa is a peninsula in East Africa that juts hundreds of kilometers into the Arabian Sea and lies along the southern side of the Gulf of Aden. It is the easternmost projection of the African continent...

's first Semitic nation, Dʿmt, was a Yemeni settlement.

The Qahtani Semites remained dominant in Yemen from 2300 BCE to 800 BCE, but little is known about this era because the Semites of the South were separated by the vast Arabian desert from Mesopotamian Semites and they lacked any type of script to record their history. However, it is known that they actively traded along the Red Sea coasts. This led to contact with the Phoenicians and from them, the Southern Semites adopted their writing script in 800 BCE and began recording their history.

The Tihama Semitic culture lasted from 1500-1200 BCE. During the late 2nd millennium BCE, a cultural Semitic complex arose in the Tihama region of Yemen and spread to northern Ethiopia

Ethiopia

Ethiopia , officially known as the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a country located in the Horn of Africa. It is the second-most populous nation in Africa, with over 82 million inhabitants, and the tenth-largest by area, occupying 1,100,000 km2...

and Eritrea

Eritrea

Eritrea , officially the State of Eritrea, is a country in the Horn of Africa. Eritrea derives it's name from the Greek word Erethria, meaning 'red land'. The capital is Asmara. It is bordered by Sudan in the west, Ethiopia in the south, and Djibouti in the southeast...

(specifically the Tigray Region

Tigray Region

Tigray Region is the northernmost of the nine ethnic regions of Ethiopia containing the homeland of the Tigray people. It was formerly known as Region 1...

, central Eritrea, and coastal areas like Adulis

Adulis

Adulis or Aduli is an archeological site in the Northern Red Sea region of Eritrea, about 30 miles south of Massawa. It was the port of the Kingdom of Aksum, located on the coast of the Red Sea. Adulis Bay is named after the port...

). The Semites of Yemen began settling the Ethiopian highlands. These settlements would reach their climax by the 8th century BCE, eventually giving rise to the Dʿmt and Aksum kingdoms

Kingdoms

During the rule of the SabaeansSabaeans

The Sabaeans or Sabeans were an ancient people speaking an Old South Arabian language who lived in what is today Yemen, in the south west of the Arabian Peninsula.Some scholars suggest a link between the Sabaeans and the Biblical land of Sheba....

, 8th century BCE to 275 CE, trade and agriculture flourished generating much wealth and prosperity. The Sabaean kingdom is located in what is now the Aseer region in southwestern Yemen, and its capital, Ma'rib, is located near what is now Yemen's modern capital, Sana'a

Sana'a

-Districts:*Al Wahdah District*As Sabain District*Assafi'yah District*At Tahrir District*Ath'thaorah District*Az'zal District*Bani Al Harith District*Ma'ain District*Old City District*Shu'aub District-Old City:...

. According to tradition, the eldest son of Noah

Noah

Noah was, according to the Hebrew Bible, the tenth and last of the antediluvian Patriarchs. The biblical story of Noah is contained in chapters 6–9 of the book of Genesis, where he saves his family and representatives of all animals from the flood by constructing an ark...

, Shem

Shem

Shem was one of the sons of Noah in the Hebrew Bible as well as in Islamic literature. He is most popularly regarded as the eldest son, though some traditions regard him as the second son. Genesis 10:21 refers to relative ages of Shem and his brother Japheth, but with sufficient ambiguity in each...

, founded the city of Ma'rib.

During Sabaean rule, Yemen was called "Arabia Felix" by the Romans who were impressed by its wealth and prosperity. The success of the Kingdom was based on the cultivation and trade of spices and aromatics including frankincense and myrrh. These were exported to the Mediterranean, India, and Abyssinia where they were greatly prized by many cultures, using camels on routes through Arabia, and to India by sea.

During the 8th and 7th century BCE, there was a close contact of cultures between the Kingdom of Dʿmt in northern Ethiopia and Eritrea and Saba'. Though the civilization was indigenous and the royal inscriptions were written in a sort of proto-Ethiosemitic

Ethiopian Semitic languages

Ethiopian Semitic is a language group, which together with Old South Arabian forms the Western branch of the South Semitic languages. The languages are spoken in both Ethiopia and Eritrea...

, there were also some Sabaean immigrants in the kingdom as evidenced by a few of the Dʿmt inscriptions.

Agriculture in Yemen thrived during this time due to an advanced irrigation system which consisted of large water tunnels in mountains, and dams. The most impressive dam, known as the dam of Ma'rib was built ca. 700 BCE, provided irrigation for about 25000 acres (101.2 km²) of land and stood for over a millennium, finally collapsing in CE 570 after centuries of neglect.

The Sabaean kingdom, with its capital at Ma'rib

Ma'rib

Ma'rib or Marib is the capital town of the Ma'rib Governorate, Yemen and was the capital of the Sabaean kingdom, which some scholars believe to be the ancient Sheba of biblical fame. It is located at , approximately 120 kilometers east of Yemen's modern capital, Sana'a...

where the remains of a large temple can still be seen, thrived for almost 14 centuries. Some have argued that this kingdom was the Sheba

Sheba

Sheba was a kingdom mentioned in the Jewish scriptures and the Qur'an...

described in the Old Testament

Old Testament

The Old Testament, of which Christians hold different views, is a Christian term for the religious writings of ancient Israel held sacred and inspired by Christians which overlaps with the 24-book canon of the Masoretic Text of Judaism...

.

Sabaean language

Sabaean , also known as Himyarite , was an Old South Arabian language spoken in Yemen from c. 1000 BC to the 6th century AD, by the Sabaeans; it was used as a written language by some other peoples of Ancient Yemen, including the Hashidites, Sirwahites, Humlanites, Ghaymanites, Himyarites,...

inscription of Karab'il Watar from the early 7th century BCE, in which the King of Hadramaut, Yadail, is mentioned as being one of his allies. When the Minaeans took control of the caravan routes in the 4th century BCE, however, Hadramaut became one of its confederates, probably because of commercial interests. It later became independent and was invaded by the growing kingdom of Himyar

Himyar

The Himyarite Kingdom or Himyar , historically referred to as the Homerite Kingdom by the Greeks and the Romans, was a kingdom in ancient Yemen. Established in 110 BC, it took as its capital the modern day city of Sana'a after the ancient city of Zafar...

toward the end of the first century BC, but it was able to repel the attack. Hadramaut annexed Qataban in the second half of the 2nd century AD, reaching its greatest size. During this period, Hadramaut was continuously at war with Himyar and Saba', and the Sabaean

Sabaeans

The Sabaeans or Sabeans were an ancient people speaking an Old South Arabian language who lived in what is today Yemen, in the south west of the Arabian Peninsula.Some scholars suggest a link between the Sabaeans and the Biblical land of Sheba....

king Sha'irum Awtar was even able to take its capital, Shabwa, in 225. During this period the Kingdom of Aksum began to interfere in South Arabian affairs. King GDRT

GDRT

GDRT was a king of the Kingdom of Aksum , known for being the first king to involve Axum in the affairs of what is now Yemen. He is known primarily from inscriptions in South Arabia that mention him and his son BYGT...

of Aksum acted by dispatching troops under his son, BYGT, sending them from the western coast to occupy Zafar

Zafar

-Given name:* Zafar Mehmood Mughal, ASC, Chairman Executive Punjab Bar Council* Zafar Bangash, Pakistani writer* Zafar Iqbal, various people* Zafar Ali Khan, Pakistani writer* Zafar Ali Naqvi, Indian politician* Zafar Saifullah, Indian politician...

, the Himyarite capital, as well as from the southern coast against Hadramaut as Sabaean allies. The kingdom of Hadramaut was eventually conquered by the Himyarite king Shammar Yuhar'ish around 300 CE, unifying all of the South Arabian kingdoms.

The ancient Kingdom of Awsan with a capital at Hagar Yahirr in the wadi Markha to the south of the wadi Bayhan is now marked by a tell

Tell

A tell or tel, is a type of archaeological mound created by human occupation and abandonment of a geographical site over many centuries. A classic tell looks like a low, truncated cone with a flat top and sloping sides.-Archaeology:A tell is a hill created by different civilizations living and...

or artificial mound, which is locally named Hagar Asfal. Once it was one of the most important small kingdoms of South Arabia.

Sabaeans

The Sabaeans or Sabeans were an ancient people speaking an Old South Arabian language who lived in what is today Yemen, in the south west of the Arabian Peninsula.Some scholars suggest a link between the Sabaeans and the Biblical land of Sheba....

Karib'il Watar, according to a Sabaean text that reports the victory in terms that attest to its significance for the Sabaeans.

Qataban

Qataban

Qataban was one of the ancient Yemeni kingdoms. Its heartland was located in the Baihan valley. Like some other Southern Arabian kingdoms it gained great wealth from the trade of frankincense and myrrh incense which were burned at altars...

, which lasted from the 4th century BCE to 200 CE, was one of the ancient Yemeni kingdoms which thrived in the Baihan valley. Like the other Southern Arabian kingdoms it gained great wealth from the trade of frankincense and myrrh incense which were burned at altars. The capital of Qataban was named Timna and was located on the trade route which passed through the other kingdoms of Hadramaut, Saba and Ma'in. The chief deity of the Qatabanians was Amm, or "Uncle" and the people called themselves the "children of Amm".

Kingdom of Ma'in

During Minaean rule the capital was at Karna (now known as Sadah). Their other important city was Yathill (now known as Baraqish). Other parts of modern Yemen include QatabanQataban

Qataban was one of the ancient Yemeni kingdoms. Its heartland was located in the Baihan valley. Like some other Southern Arabian kingdoms it gained great wealth from the trade of frankincense and myrrh incense which were burned at altars...

and the coastal string of watering stations known as the Hadhramaut

Hadhramaut

Hadhramaut, Hadhramout, Hadramawt or Ḥaḍramūt is the formerly independent Qu'aiti state and sultanate encompassing a historical region of the south Arabian Peninsula along the Gulf of Aden in the Arabian Sea, extending eastwards from Yemen to the borders of the Dhofar region of Oman...

. Though Saba' dominated in the earlier period of South Arabian history, Minaic inscriptions are of the same time period as the first Sabaic inscriptions. Note, however, that they pre-date the appearance of the Minaeans themselves, and, hence, are called now more appropriately as "Madhabic" rather than "Minaic". The Minaean Kingdom was centered in northwestern Yemen, with most of its cities laying along the Wadi Madhab. Minaic inscriptions have been found far afield of the Kingdom of Ma'in, as far away as al-'Ula in northwestern Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia , commonly known in British English as Saudi Arabia and in Arabic as as-Sa‘ūdiyyah , is the largest state in Western Asia by land area, constituting the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula, and the second-largest in the Arab World...

and even on the island of Delos

Delos

The island of Delos , isolated in the centre of the roughly circular ring of islands called the Cyclades, near Mykonos, is one of the most important mythological, historical and archaeological sites in Greece...

and in Egypt

Egypt

Egypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

. It was the first of the South Arabian kingdoms to end, and the Minaic language died around 100 CE.

Kingdom of Himyar

The Himyarites had united Southwestern Arabia, controlling the Red Sea

Red Sea

The Red Sea is a seawater inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. The connection to the ocean is in the south through the Bab el Mandeb strait and the Gulf of Aden. In the north, there is the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and the Gulf of Suez...

as well as the coasts of the Gulf of Aden

Gulf of Aden

The Gulf of Aden is located in the Arabian Sea between Yemen, on the south coast of the Arabian Peninsula, and Somalia in the Horn of Africa. In the northwest, it connects with the Red Sea through the Bab-el-Mandeb strait, which is about 20 miles wide....

. From their capital city, the Himyarite Kings launched successful military campaigns, and had stretched its domain at times as far east as the Persian Gulf

Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf, in Southwest Asia, is an extension of the Indian Ocean located between Iran and the Arabian Peninsula.The Persian Gulf was the focus of the 1980–1988 Iran-Iraq War, in which each side attacked the other's oil tankers...

and as far north to the Arabian Desert.

During the 3rd century CE, the South Arabian kingdoms were in continuous conflict with one another. GDRT

GDRT

GDRT was a king of the Kingdom of Aksum , known for being the first king to involve Axum in the affairs of what is now Yemen. He is known primarily from inscriptions in South Arabia that mention him and his son BYGT...

of Aksum began to interfere in South Arabian affairs, signing an alliance with Saba', and a Himyarite text notes that Hadramaut and Qataban were also all allied against the kingdom. As a result of this, the Kingdom of Aksum was able to capture the Himyarite capital of Zafar

Zafar

-Given name:* Zafar Mehmood Mughal, ASC, Chairman Executive Punjab Bar Council* Zafar Bangash, Pakistani writer* Zafar Iqbal, various people* Zafar Ali Khan, Pakistani writer* Zafar Ali Naqvi, Indian politician* Zafar Saifullah, Indian politician...

in the first quarter of the 3rd century. However, the alliances did not last, and Sha'ir Awtar of Saba' unexpectedly turned on Hadramaut, allying again with Aksum and taking its capital in 225. Himyar then allied with Saba' and invaded the newly taken Aksumite territories, retaking Zafar, which had been under the control of GDRT's son BYGT, and pushing Aksum back into the Tihama

Tihamah

Tihamah or Tihama is a narrow coastal region of Arabia on the Red Sea. It is currently divided between Saudi Arabia and Yemen. In a broad sense, Tihamah refers to the entire coastline from the Gulf of Aqaba to the Bab el Mandeb Strait but it more often refers only to its southern half, starting...

.

They established their capital at Zafar

Zafar

-Given name:* Zafar Mehmood Mughal, ASC, Chairman Executive Punjab Bar Council* Zafar Bangash, Pakistani writer* Zafar Iqbal, various people* Zafar Ali Khan, Pakistani writer* Zafar Ali Naqvi, Indian politician* Zafar Saifullah, Indian politician...

(now just a small village in the Ibb

Ibb

Ibb is a city in Yemen, the capital of Ibb Governorate, situated on a mountain ridge, surrounded by fertile land and is known as "The Green City". It is located about 73 miles north-east of Mocha. Ibb was governed by a semi-autonomous emir until 1944, when the emirate was abolished...

region) and gradually absorbed the Sabaean kingdom. They traded from the port of al-Muza on the Red Sea. Dhu Nuwas

Dhu Nuwas

Yūsuf Dhū Nuwas, was the last king of the Himyarite kingdom of Yemen and a convert to Judaism....

, a Himyarite king, changed the state religion to Judaism

Judaism

Judaism ) is the "religion, philosophy, and way of life" of the Jewish people...

in the beginning of the 6th century and began to massacre the Christians. Outraged, Kaleb

Kaleb of Axum

Kaleb is perhaps the best-documented, if not best-known, king of Axum. Procopius of Caesarea calls him "Hellestheaeus", a variant of his throne name Ella Atsbeha or Ella Asbeha...

, the Christian King of Aksum with the encouragement of the Byzantine Emperor Justin I

Justin I

Justin I was Byzantine Emperor from 518 to 527. He rose through the ranks of the army and ultimately became its Emperor, in spite of the fact he was illiterate and almost 70 years old at the time of accession...

invaded and annexed Yemen. About fifty years later, Sayf ibn Dhi Yazan

Sayf ibn Dhi Yazan

Sayf ibn dhī-Yazan was a Yemeni Himyarite king who lived between 516 and 574 CE, known for ending Aksumite rule over Southern Arabia...

asked for help from the Persians, so the Persians sent all of their criminals as an army to Yemen. One way to help get rid of the criminals in jail, and help their new ally Sayf ibn Dhi Yazan

Sayf ibn Dhi Yazan

Sayf ibn dhī-Yazan was a Yemeni Himyarite king who lived between 516 and 574 CE, known for ending Aksumite rule over Southern Arabia...

.

Kingdom of Aksum

Judaism

Judaism ) is the "religion, philosophy, and way of life" of the Jewish people...

king called Yusuf Asar Yathar

Dhu Nuwas

Yūsuf Dhū Nuwas, was the last king of the Himyarite kingdom of Yemen and a convert to Judaism....

(also known as Dhu Nuwas) usurped the kingship of Himyar from Ma'adkarib Ya'fur. Interestingly, Pseudo-Zacharias

Zacharias Rhetor

Zacharias of Mytilene , also known as Zacharias Scholasticus or Zacharias Rhetor, was a bishop and ecclesiastical historian....

of Mytilene

Mytilene

Mytilene is a town and a former municipality on the island of Lesbos, North Aegean, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Lesbos, of which it is a municipal unit. It is the capital of the island of Lesbos. Mytilene, whose name is pre-Greek, is built on the...

(fl. late 6th century) says that Yusuf became king because the previous king had died in winter, when the Aksumites could not cross the Red Sea

Red Sea

The Red Sea is a seawater inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. The connection to the ocean is in the south through the Bab el Mandeb strait and the Gulf of Aden. In the north, there is the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and the Gulf of Suez...

and appoint another king. Ma'adkarib Ya'fur's long title puts its truthfulness in doubt, however. Upon gaining power, Yusuf attacked the Aksumite garrison in Zafar

Zafar

-Given name:* Zafar Mehmood Mughal, ASC, Chairman Executive Punjab Bar Council* Zafar Bangash, Pakistani writer* Zafar Iqbal, various people* Zafar Ali Khan, Pakistani writer* Zafar Ali Naqvi, Indian politician* Zafar Saifullah, Indian politician...

, the Himyarite capital, killing many and destroying the church there. The Christian King Kaleb of Axum

Kaleb of Axum

Kaleb is perhaps the best-documented, if not best-known, king of Axum. Procopius of Caesarea calls him "Hellestheaeus", a variant of his throne name Ella Atsbeha or Ella Asbeha...

learned of Dhu Nuwas's persecutions of Christians and Aksumites, and, according to Procopius

Procopius

Procopius of Caesarea was a prominent Byzantine scholar from Palestine. Accompanying the general Belisarius in the wars of the Emperor Justinian I, he became the principal historian of the 6th century, writing the Wars of Justinian, the Buildings of Justinian and the celebrated Secret History...

, was further encouraged by his ally and fellow Christian Justin I

Justin I

Justin I was Byzantine Emperor from 518 to 527. He rose through the ranks of the army and ultimately became its Emperor, in spite of the fact he was illiterate and almost 70 years old at the time of accession...

of Byzantium, who requested Aksum's help to cut off silk

Silk

Silk is a natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be woven into textiles. The best-known type of silk is obtained from the cocoons of the larvae of the mulberry silkworm Bombyx mori reared in captivity...

supplies as part of his economic war against the Persians

Sassanid Empire

The Sassanid Empire , known to its inhabitants as Ērānshahr and Ērān in Middle Persian and resulting in the New Persian terms Iranshahr and Iran , was the last pre-Islamic Persian Empire, ruled by the Sasanian Dynasty from 224 to 651...

.

Kaleb sent a fleet across the Red Sea and was able to defeat Dhu Nuwas, who was killed in battle according to an inscription from Husn al-Ghurab, while later Arab tradition has him riding his horse into the sea. Kaleb installed a native Himyar

Himyar

The Himyarite Kingdom or Himyar , historically referred to as the Homerite Kingdom by the Greeks and the Romans, was a kingdom in ancient Yemen. Established in 110 BC, it took as its capital the modern day city of Sana'a after the ancient city of Zafar...

ite viceroy, Sumyafa' Ashwa', who ruled until 525, when he was deposed by the Aksumite general (or soldier and former slave) Abraha

Abraha

Abraha also known as Abraha al-Ashram or Abraha b...

with the support of disgruntled Ethiopia

Ethiopia

Ethiopia , officially known as the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a country located in the Horn of Africa. It is the second-most populous nation in Africa, with over 82 million inhabitants, and the tenth-largest by area, occupying 1,100,000 km2...

n soldiers. According to the later Arabic sources, Kaleb retaliated by sending a force of 3,000 men under a relative, but the troops defected and killed their leader, and a second attempt at reigning in the rebellious Abraha also failed. Later Ethiopian sources state that Kaleb abdicated to live out his years in a monastery and sent his crown to be hung in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre

Church of the Holy Sepulchre

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre, also called the Church of the Resurrection by Eastern Christians, is a church within the walled Old City of Jerusalem. It is a few steps away from the Muristan....

in Jerusalem. While uncertain, it seems to be supported by the die-links between his coins and those of his successor, Alla Amidas

Alla Amidas

Alla Amidas was a king of Axum. He is primarily known from the coins minted during his reign.Due to die-links between the coins of Alla Amidas and Kaleb, Munro-Hay suggests that the two kings were co-rulers, Alla Amidas possibly ruling the African territories while Kaleb was across the Red Sea...

. An inscription of Sumyafa' Ashwa' also mentions two kings (nagaśt) of Aksum, indicating that the two may have co-ruled for a while before Kaleb abdicated in favor of Alla Amidas.

Procopius notes that Abraha later submitted to Kaleb's successor, as supported by the former's inscription in 543 stating Aksum before the territories directly under his control. During his reign, Abraha repaired the Marib Dam

Marib Dam

The Marib or Ma'rib or Ma'arib Dam blocks the Wadi Adhanah in the valley of Dhana in the Balaq Hills, Yemen. The current dam is close to the ruins of the Great Dam of Marib, dating from around the eighth century BC...

in 543, and received embassies from Persia and Byzantium, including a request to free some bishops who had been imprisoned at Nisbis (according to John of Epheseus's Life of Simeon). Abraha ruled until at least 547, sometime after which he was succeeded by his son, Aksum. Aksum (called "Yaksum" in Arabic sources) was perplexingly referred to as "of Ma'afir" (ḏū maʻāfir), the southwestern coast of Yemen, in Abraha's Marib dam inscription, and was succeeded by his brother, Masruq. Aksumite control in Yemen ended in 570 with the invasion of the elder Sassanid general Vahriz

Vahriz

Vahriz was a Deylamite spahbod in the service of the Sassanid Empire. He was the head of a small expeditionary force of low ranking Azatan nobility, numbering around 700, sent by Khosrau I to Yemen....

who, according to later legends, famously killed Masruq with his well-aimed arrow.

Later Arabic sources also say that Abraha

Abraha

Abraha also known as Abraha al-Ashram or Abraha b...

constructed a great Church called al-Qulays at Sana'a

Sana'a

-Districts:*Al Wahdah District*As Sabain District*Assafi'yah District*At Tahrir District*Ath'thaorah District*Az'zal District*Bani Al Harith District*Ma'ain District*Old City District*Shu'aub District-Old City:...

in order to divert pilgrimage from the Kaaba

Kaaba

The Kaaba is a cuboid-shaped building in Mecca, Saudi Arabia, and is the most sacred site in Islam. The Qur'an states that the Kaaba was constructed by Abraham, or Ibraheem, in Arabic, and his son Ishmael, or Ismaeel, as said in Arabic, after he had settled in Arabia. The building has a mosque...

and have him die in the Year of the Elephant

Year of the Elephant

The Year of the Elephant is the name in Islamic history for the year approximately equating to 570 AD. According to Islamic tradition, it was in this year that Muhammad was born...

(570) after returning from a failed attack on Mecca. The exact chronology of the early wars are uncertain, as a 525 inscription mentions the death of a King of Himyar, which could refer either to the Himyarite viceory of Aksum, Sumyafa' Ashwa', or to Yusuf Asar Yathar. The later Arabic histories also mention a conflict between Abraha

Abraha

Abraha also known as Abraha al-Ashram or Abraha b...

and another Aksumite general named Aryat occurring in 525 as leading to the rebellion.

Sassanid period

The Persian king Khosrau IKhosrau I

Khosrau I , also known as Anushiravan the Just or Anushirawan the Just Khosrau I (also called Chosroes I in classical sources, most commonly known in Persian as Anushirvan or Anushirwan, Persian: انوشيروان meaning the immortal soul), also known as Anushiravan the Just or Anushirawan the Just...

, sent troops under the command of Vahriz

Vahriz

Vahriz was a Deylamite spahbod in the service of the Sassanid Empire. He was the head of a small expeditionary force of low ranking Azatan nobility, numbering around 700, sent by Khosrau I to Yemen....

, who helped Sayf ibn Dhi Yazan

Sayf ibn Dhi Yazan

Sayf ibn dhī-Yazan was a Yemeni Himyarite king who lived between 516 and 574 CE, known for ending Aksumite rule over Southern Arabia...

to drive the Ethiopian Aksumites out of Yemen. Southern Arabia became a Persian dominion under a Yemenite vassal and thus came within the sphere of influence of the Sassanid Empire

Sassanid Empire

The Sassanid Empire , known to its inhabitants as Ērānshahr and Ērān in Middle Persian and resulting in the New Persian terms Iranshahr and Iran , was the last pre-Islamic Persian Empire, ruled by the Sasanian Dynasty from 224 to 651...

. Later another army was sent to Yemen, and in 597/8 Southern Arabia became a province of the Sassanid Empire under a Persian satrap

Satrap

Satrap was the name given to the governors of the provinces of the ancient Median and Achaemenid Empires and in several of their successors, such as the Sassanid Empire and the Hellenistic empires....

. It was a Persian province by name but after the Persians assassinated Dhi Yazan, Yemen divided into a number of autonomous kingdoms.

This development was a consequence of the expansionary policy pursued by the Sassanian king Khosrau II Parviz (590-628), whose aim was to secure Persian border areas such as Yemen. Following the death of Khosrau II in 628, then the Persian governor in Southern Arabia, Badhan

Badhan

Badhan may refer to:* Badhan, Sanaag, Somalia* al-Badhan, a Palestinian village in the West Bank* Badhan , a group founded at the University of Dhaka to promote blood donation* Badhan , a clan of the Jat people....

, converted to Islam and Yemen followed the new religion.

Islamic history

Muhammad

Muhammad |ligature]] at U+FDF4 ;Arabic pronunciation varies regionally; the first vowel ranges from ~~; the second and the last vowel: ~~~. There are dialects which have no stress. In Egypt, it is pronounced not in religious contexts...

's lifetime. At that time the Persian governor Badhan

Badhan (Persian Governor)

Bādhān was the Persian Governor of Yemen, during the reign of Khosrau II. He ruled from Sana'a. During his rule, he was ordered by Khosrau II to send some men to Medina to bring Muhammad to Khosrau II himself. Badhan sent two men for this task. When these two men met Muhammad and demanded he come...

was ruling. Thereafter Yemen was ruled as part of Arab-Islamic caliphates, and Yemen became a province in the Islamic empire

Rashidun Caliphate

The Rashidun Caliphate , comprising the first four caliphs in Islam's history, was founded after Muhammad's death in 632, Year 10 A.H.. At its height, the Caliphate extended from the Arabian Peninsula, to the Levant, Caucasus and North Africa in the west, to the Iranian highlands and Central Asia...

.

Yemeni textiles, long recognized for their fine quality, maintained their reputation and were exported for use by the Abbasid

Abbasid

The Abbasid Caliphate or, more simply, the Abbasids , was the third of the Islamic caliphates. It was ruled by the Abbasid dynasty of caliphs, who built their capital in Baghdad after overthrowing the Umayyad caliphate from all but the al-Andalus region....

elite, including the caliph

Caliph

The Caliph is the head of state in a Caliphate, and the title for the ruler of the Islamic Ummah, an Islamic community ruled by the Shari'ah. It is a transcribed version of the Arabic word which means "successor" or "representative"...

s themselves. The products of Sana'a and Aden

Aden

Aden is a seaport city in Yemen, located by the eastern approach to the Red Sea , some 170 kilometres east of Bab-el-Mandeb. Its population is approximately 800,000. Aden's ancient, natural harbour lies in the crater of an extinct volcano which now forms a peninsula, joined to the mainland by a...

are especially important in the East-West textile trade.

The former North Yemen

North Yemen

North Yemen is a term currently used to designate the Yemen Arab Republic , its predecessor, the Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen , and their predecessors that exercised sovereignty over the territory that is now the north-western part of the state of Yemen in southern Arabia.Neither state ever...

came under control of Imams

Imamah (Shi'a doctrine)

Imāmah is the Shia doctrine of religious, spiritual and political leadership of the Ummah. The Shīa believe that the A'immah are the true Caliphs or rightful successors of Muḥammad, and further that Imams are possessed of divine knowledge and authority as well as being part of the Ahl al-Bayt,...

of various dynasties usually of the Zaidi sect, who established a theocratic political structure that survived until modern times. In 897, a Zaidi ruler, Yahya al-Hadi ila'l Haqq

Al-Hadi ila'l-Haqq Yahya

Al-Hadi ila’l-Haqq Yahya was a religious and political leader on the Arabian Peninsula. He was the first Zaydiyya imam who ruled over portions of Yemen, in 897-911, and is the ancestor of the Rassid Dynasty which held intermittent power in Yemen until 1962.-Background:Yahya bin al-Husayn bin...

, founded a line of Imams, whose Shiite dynasty survived until the second half of the 20th century.

Nevertheless, Yemen's medieval history is a tangled chronicle of contesting local Imams. The Fatimid

Fatimid

The Fatimid Islamic Caliphate or al-Fāṭimiyyūn was a Berber Shia Muslim caliphate first centered in Tunisia and later in Egypt that ruled over varying areas of the Maghreb, Sudan, Sicily, the Levant, and Hijaz from 5 January 909 to 1171.The caliphate was ruled by the Fatimids, who established the...

s of Egypt

Egypt

Egypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

helped the Isma'ilis maintain dominance in the 11th century. Saladin

Saladin

Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn Yūsuf ibn Ayyūb , better known in the Western world as Saladin, was an Arabized Kurdish Muslim, who became the first Sultan of Egypt and Syria, and founded the Ayyubid dynasty. He led Muslim and Arab opposition to the Franks and other European Crusaders in the Levant...

(Salah ad-Din) annexed Yemen in 1173. The Rasulid

Rasulid

The Rasulid was a Muslim dynasty that ruled Yemen and Hadhramaut from 1229 to 1454. The Rasulids assumed power after the Egyptian Ayyubid left the southern provinces of the Arabian Peninsula....

dynasty ruled Yemen, with Zabid

Zabid

Zabid is a town with an urban population of around 23,000 persons on Yemen's western coastal plain. The town, named after Wadi Zabid, the wadi to its south, is one of the oldest towns in Yemen...

as its capital, from about 1230 to the 15th century. In 1516, the Mamluk

Mamluk Sultanate (Cairo)

The Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt was the final independent Egyptian state prior to the establishment of the Muhammad Ali Dynasty in 1805. It lasted from the overthrow of the Ayyubid Dynasty until the Ottoman conquest of Egypt in 1517. The sultanate's ruling caste was composed of Mamluks, Arabised...

s of Egypt annexed Yemen; but in the following year, the Mamluk governor surrendered to the Ottomans

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

, and Turkish armies subsequently overran the country. They were challenged by the Zaidi Imam, Qasim the Great

Al-Mansur al-Qasim

Al-Mansur al-Qasim , with the cognomen al-Kabir , was an Imam of Yemen, who commenced the struggle to liberate Yemen from the Ottoman occupiers...

(r.1597–1620), and were expelled from the interior around 1630. From then until the 19th century, the Ottomans retained control only of isolated coastal areas, while the highlands generally were ruled by the Zaidi Imams.

19th century

As the Zaidi ImamateImamate

The word Imamate is an Arabic word with an English language suffix meaning leadership. Its use in theology is confined to Islam.-Theological usage:...

collapsed in the 19th century due to internal division, the Ottomans moved south along the west coast of Arabia back into northern Yemen in the 1830s, and eventually even took San'a' making it the Yemeni district capital in 1872. The Ottomans were aided by the adoption of Crimean War

Crimean War

The Crimean War was a conflict fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the French Empire, the British Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Sardinia. The war was part of a long-running contest between the major European powers for influence over territories of the declining...

modern weapons.

British

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

interests in the area which would later become South Yemen, began to grow when in 1832, British East India Company

British East India Company

The East India Company was an early English joint-stock company that was formed initially for pursuing trade with the East Indies, but that ended up trading mainly with the Indian subcontinent and China...

forces captured the port of Aden

Aden

Aden is a seaport city in Yemen, located by the eastern approach to the Red Sea , some 170 kilometres east of Bab-el-Mandeb. Its population is approximately 800,000. Aden's ancient, natural harbour lies in the crater of an extinct volcano which now forms a peninsula, joined to the mainland by a...

, to provide a coal

Coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock usually occurring in rock strata in layers or veins called coal beds or coal seams. The harder forms, such as anthracite coal, can be regarded as metamorphic rock because of later exposure to elevated temperature and pressure...

ing station for ships en route to India

India

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

. The British interest in reducing pirate attacks on British merchants lead to their creating a protectorate over the town of Aden in 1839, and adding the surrounding lands over the following years.ʻAmrī, Muḥsin ibn Aḥmad Ḥarrāzī; Ḥusayn ʻAbd Allāh (1986) Fatrat al-fawḍá wa-ʻawdat al-Atrāk ilá Ṣanʻāʼ : al-sifr al-thānī min tārīkh al-Ḥarrāzī (Riyāḍ al-rayāḥīn) 1276-1289 H/1859-1872 M Dār al-Fikr, Dimashq 9الحرازي، محسن ابن أجمد. تحقيق ودراسة حسين عبد الله العمري. عمري، حسين عبد الله. فترة الفوضى وعودة الأتراك الى صنعاء : السفر الثاني من تاريخ الحرازي (رياض الرياحين) ٦٧٢١-٩٨٢١ ه/٩٥٨١-٢٧٨١ م دار الفكر ؛ دار الحكمة اليمانية،

The colony

Colony

In politics and history, a colony is a territory under the immediate political control of a state. For colonies in antiquity, city-states would often found their own colonies. Some colonies were historically countries, while others were territories without definite statehood from their inception....

gained much political

Politics

Politics is a process by which groups of people make collective decisions. The term is generally applied to the art or science of running governmental or state affairs, including behavior within civil governments, but also applies to institutions, fields, and special interest groups such as the...

and strategic

Strategy

Strategy, a word of military origin, refers to a plan of action designed to achieve a particular goal. In military usage strategy is distinct from tactics, which are concerned with the conduct of an engagement, while strategy is concerned with how different engagements are linked...

importance after the opening of the Suez Canal

Suez Canal

The Suez Canal , also known by the nickname "The Highway to India", is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea. Opened in November 1869 after 10 years of construction work, it allows water transportation between Europe and Asia without navigation...

in 1869 and the increased traffic on the Red Sea route to India

The Ottomans and the British eventually established a de facto

De facto

De facto is a Latin expression that means "concerning fact." In law, it often means "in practice but not necessarily ordained by law" or "in practice or actuality, but not officially established." It is commonly used in contrast to de jure when referring to matters of law, governance, or...

border between north and south Yemen, which was formalized in a treaty in 1904. However the interior boundaries were never clearly established. However the presence of the Ottomans, and to a lesser extent the British, allowed the Zaydi Imamate to rebuild against a common enemy. Guerrilla warfare and banditry erupted into the rebellion of the Zaydi tribes in 1905.

Starting in the latter decades of the 19th century and continuing into the 20th century, Britain signed agreements with local rulers of traditional polities that, together, became known as the Aden Protectorate

Aden Protectorate

The Aden Protectorate was a British protectorate in southern Arabia which evolved in the hinterland of Aden following the acquisition of that port by Britain in 1839 as an anti-piracy station, and it continued until the 1960s. For administrative purposes it was divided into the Western...

. The area was divided into numerous sultanates, emirates, and sheikhdoms, and was divided for administrative purposes into the East Aden Protectorate and the West Aden Protectorate. The eastern protectorate consisted of the three Hadhramaut states (Qu'aiti

Qu'aiti

Qu'aiti , officially the Qu'aiti State in Hadhramaut Qu'aiti , officially the Qu'aiti State in Hadhramaut Qu'aiti , officially the Qu'aiti State in Hadhramaut (Arabic: (الدولة القعيطية الحضرمية) or the Qu'aiti Sultanate of Shihr and Mukalla (Arabic:سلطنة الشحر والمكلاا ), was a sultanate in the...

State of Shihr and Mukalla

Al Mukalla

Al Mukalla is a main sea port and the capital city of the Hadramaut coastal region in Yemen in the southern part of Arabia on the Gulf of Aden close to the Arabian Sea...

, Kathiri

Kathiri

Kathiri was a sultanate in the Hadhramaut region of the southern Arabian Peninsula, in what is now officially considered part of Yemen and the Dhofar region of Oman....

State of Seiyun

Seiyun

Say'un is a town in the Hadhramaut region of Yemen. Postage stamps from the former Aden Protectorate sultanate of Kathiri are sometimes inscribed "Kathiri State of Seiyun." As of 2006 the population was 75,700....

, Mahra

Mahra Sultanate

The Mahra Sultanate of Qishn and Socotra or sometimes the Mahra Sultanate of Ghayda and Socotra was a sultanate that included both the historical region of Mahra and the Indian Ocean island of Socotra in what is now eastern Yemen...

State of Qishn

Qishn

Qishn is a coastal town in Al Mahrah Governorate, southern Yemen. It is located at around . Its population is estimated at more than 80000. It has a landing strip, which is currently not in use....

and Socotra

Socotra

Socotra , also spelt Soqotra, is a small archipelago of four islands in the Indian Ocean. The largest island, also called Socotra, is about 95% of the landmass of the archipelago. It lies some east of the Horn of Africa and south of the Arabian Peninsula. The island is very isolated and through...

) with the remaining states comprising the west.

Modern history

Imamah (Shi'a doctrine)

Imāmah is the Shia doctrine of religious, spiritual and political leadership of the Ummah. The Shīa believe that the A'immah are the true Caliphs or rightful successors of Muḥammad, and further that Imams are possessed of divine knowledge and authority as well as being part of the Ahl al-Bayt,...

's rule over Upper Yemen

Upper Yemen

Upper Yemen and Lower Yemen are traditional regions of the north western highland mountains of Yemen. Northern Highlands and Southern Highlands are terms more commonly used presently. The Sumara Mountains just south of the town of Yarim denote the boundaries of the two regions. These two...

was formally recognized. Turkish forces withdrew in 1918, and Imam Yahya Muhammad

Yahya Muhammad Hamid ed-Din

Yahya Muhammad Hamidaddin became Imam of the Zaydis in 1904 and Imam of Yemen in 1918. His name in full was Amir al-Mumenin al-Mutawakkil 'Ala Allah Rab ul-Alamin Imam Yahya bin al-Mansur Bi'llah Muhammad Hamidaddin, Imam and Commander of the Faithful.Yahya Muhammad Hamidaddin was born on Friday...

strengthened his control over northern Yemen creating the Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen

Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen

The Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen , sometimes spelled Mutawakelite Kingdom of Yemen, also known as the Kingdom of Yemen or as North Yemen, was a country from 1918 to 1962 in the northern part of what is now Yemen...

.

Meanwhile, Aden was ruled as part of British India until 1937, when the city of Aden became the Colony of Aden, a crown colony

Crown colony

A Crown colony, also known in the 17th century as royal colony, was a type of colonial administration of the English and later British Empire....

in its own right. The Aden hinterland

Hinterland

The hinterland is the land or district behind a coast or the shoreline of a river. Specifically, by the doctrine of the hinterland, the word is applied to the inland region lying behind a port, claimed by the state that owns the coast. The area from which products are delivered to a port for...

and Hadhramaut

Hadhramaut

Hadhramaut, Hadhramout, Hadramawt or Ḥaḍramūt is the formerly independent Qu'aiti state and sultanate encompassing a historical region of the south Arabian Peninsula along the Gulf of Aden in the Arabian Sea, extending eastwards from Yemen to the borders of the Dhofar region of Oman...

to the east formed the remainder of what would become South Yemen and were not administered directly by Aden but were tied to Britain by treaties of protection. Economic development

Economic development

Economic development generally refers to the sustained, concerted actions of policymakers and communities that promote the standard of living and economic health of a specific area...

was largely centred in Aden, and while the city flourished partly due to the discovery of crude oil on the Arabian Peninsula

Arabian Peninsula

The Arabian Peninsula is a land mass situated north-east of Africa. Also known as Arabia or the Arabian subcontinent, it is the world's largest peninsula and covers 3,237,500 km2...

in the 1930s, the states of the Aden Protectorate stagnated.

Yemen became a member of the Arab League

Arab League

The Arab League , officially called the League of Arab States , is a regional organisation of Arab states in North and Northeast Africa, and Southwest Asia . It was formed in Cairo on 22 March 1945 with six members: Egypt, Iraq, Transjordan , Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, and Syria. Yemen joined as a...

in 1945 and the United Nations

United Nations

The United Nations is an international organization whose stated aims are facilitating cooperation in international law, international security, economic development, social progress, human rights, and achievement of world peace...

in 1947.

Imam Yahya died during an unsuccessful coup attempt in 1948 and was succeeded by his son Ahmad. Ahmad bin Yahya

Ahmad bin Yahya

Ahmad bin Yahya Hamidaddin was the penultimate king of the Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen from 1948 to 1962. His full name and title was H.M. al-Nasir-li-din Allah Ahmad bin al-Mutawakkil 'Ala Allah Yahya, Imam and Commander of the Faithful, and King of the Mutawakkilite Kingdom of the Yemen...

's reign was marked by growing econimic and political reforms, renewed friction with the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

over the British presence in the south, and growing pressures to support the Arab nationalist objectives of Egyptian President Gamal Abdul Nasser. He died in September 1962.

Encouraged by the rhetoric of President Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein was the second President of Egypt from 1956 until his death. A colonel in the Egyptian army, Nasser led the Egyptian Revolution of 1952 along with Muhammad Naguib, the first president, which overthrew the monarchy of Egypt and Sudan, and heralded a new period of...

of Egypt

Egypt

Egypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

against British colonial rule in the Middle East

Middle East

The Middle East is a region that encompasses Western Asia and Northern Africa. It is often used as a synonym for Near East, in opposition to Far East...

, pressure for the British to leave South Yemen grew. Following Nasser's creation of the United Arab Republic

United Arab Republic

The United Arab Republic , often abbreviated as the U.A.R., was a sovereign union between Egypt and Syria. The union began in 1958 and existed until 1961, when Syria seceded from the union. Egypt continued to be known officially as the "United Arab Republic" until 1971. The President was Gamal...

, attempts to incorporate Yemen in turn threatened Aden and the Protectorate. To counter this, the British attempted to unite the various states under its protection and, on 11 February 1959, six of the West Aden Protectorate states formed the Federation of Arab Emirates of the South

Federation of Arab Emirates of the South

The Federation of Arab Emirates of the South was an organization of states within the British Aden Protectorate in what would become South Yemen. The Federation of six states was inaugurated in the British Colony of Aden on 11 February 1959. It subsequently added nine states and, on 4 April...

to which nine other states were subsequently added.

1960s

Shortly after assuming power in 1962, Ahmad's son, the Crown Prince Muhammad al-BadrMuhammad al-Badr

H.M. Muhammad Al-Badr was the last king of the Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen and leader of the monarchist regions during the North Yemen Civil War...

was deposed by coup forces, who took control of Sanaa

Sana'a

-Districts:*Al Wahdah District*As Sabain District*Assafi'yah District*At Tahrir District*Ath'thaorah District*Az'zal District*Bani Al Harith District*Ma'ain District*Old City District*Shu'aub District-Old City:...

and created the Yemen Arab Republic

Yemen Arab Republic

The Yemen Arab Republic , also known as North Yemen or Yemen , was a country from 1962 to 1990 in the western part of what is now Yemen...

(YAR). Egypt assisted the YAR with troops and supplies to combat forces loyal to the Kingdom. Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia , commonly known in British English as Saudi Arabia and in Arabic as as-Sa‘ūdiyyah , is the largest state in Western Asia by land area, constituting the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula, and the second-largest in the Arab World...

and Jordan

Jordan

Jordan , officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan , Al-Mamlaka al-Urduniyya al-Hashemiyya) is a kingdom on the East Bank of the River Jordan. The country borders Saudi Arabia to the east and south-east, Iraq to the north-east, Syria to the north and the West Bank and Israel to the west, sharing...

supported Badr's royalist forces to oppose the newly formed republic starting the North Yemen Civil War

North Yemen Civil War

The North Yemen Civil War was fought in North Yemen between royalists of the Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen and factions of the Yemen Arab Republic from 1962 to 1970. The war began with a coup d'état carried out by the republican leader, Abdullah as-Sallal, which dethroned the newly crowned Imam...

. Conflict continued periodically until 1967 when Egyptian troops were withdrawn.

During the 1960s, the British sought to incorporate all of the Aden Protectorate

Aden Protectorate

The Aden Protectorate was a British protectorate in southern Arabia which evolved in the hinterland of Aden following the acquisition of that port by Britain in 1839 as an anti-piracy station, and it continued until the 1960s. For administrative purposes it was divided into the Western...

territories into the Federation. On 18 January 1963, the Colony of Aden was incorporated against the wishes of much of the city's populace as the State of Aden and the Federation was renamed the Federation of South Arabia

Federation of South Arabia

The Federation of South Arabia was an organization of states under British protection in what would become South Yemen. It was formed on 4 April 1962 from the 15 protected states of the Federation of Arab Emirates of the South. On 18 January 1963 it was merged with the crown colony of Aden...

. Several more states subsequently joined the Federation and the remaining states that declined to join, mainly in Hadhramaut, formed the Protectorate of South Arabia

Protectorate of South Arabia

The Protectorate of South Arabia was a grouping of states under treaties of protection with Britain. The Protectorate was designated on 18 January 1963 as consisting of those areas of the Aden Protectorate that did not join the Federation of South Arabia, and it broadly, but not exactly,...

.

In 1963 fighting between Egyptian forces and British-led Saudi

Saudi Arabia

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia , commonly known in British English as Saudi Arabia and in Arabic as as-Sa‘ūdiyyah , is the largest state in Western Asia by land area, constituting the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula, and the second-largest in the Arab World...

-financed guerrilla

Guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare and refers to conflicts in which a small group of combatants including, but not limited to, armed civilians use military tactics, such as ambushes, sabotage, raids, the element of surprise, and extraordinary mobility to harass a larger and...

s in the Yemen Arab Republic

Yemen Arab Republic

The Yemen Arab Republic , also known as North Yemen or Yemen , was a country from 1962 to 1990 in the western part of what is now Yemen...

spread to South Arabia with the formation of the National Liberation Front

National Liberation Front (Yemen)

The National Liberation Front or NLF was a military organization operating in the Federation of South Arabia in the 60s. During the North Yemen Civil War fighting spilled over into South Yemen as the British tried to exit its Federation of South Arabia colony...

(NLF), who hoped to force the British out of South Arabia. Hostilities started with a grenade attack by the NLF against the British High Commissioner on 10 December 1963, killing one person and injuring fifty, and a state of emergency

State of emergency

A state of emergency is a governmental declaration that may suspend some normal functions of the executive, legislative and judicial powers, alert citizens to change their normal behaviours, or order government agencies to implement emergency preparedness plans. It can also be used as a rationale...

was declared, becoming known as the Aden Emergency

Aden Emergency

The Aden Emergency was an insurgency against the British crown forces in the British controlled territories of South Arabia which now form part of the Yemen. Partly inspired by Nasser's pan Arab nationalism, it began on 10 December 1963 with the throwing of a grenade at a gathering of British...

.

In January 1964, the British moved into the Radfan

Radfan

Radfan or the Radfan Hills is a region of the Republic of Yemen. In the 1960s, the area was part of a British protectorate of Dhala and was the site of intense fighting during the Aden Emergency...

hills in the border region to confront Egyptian-backed guerrillas, later reinforced by the NLF. By October they had largely been suppressed, and the NLF switched to grenade attacks against off-duty military

Military

A military is an organization authorized by its greater society to use lethal force, usually including use of weapons, in defending its country by combating actual or perceived threats. The military may have additional functions of use to its greater society, such as advancing a political agenda e.g...

personnel and police

Police

The police is a personification of the state designated to put in practice the enforced law, protect property and reduce civil disorder in civilian matters. Their powers include the legitimized use of force...

officers elsewhere in the Aden Colony.

In 1964, the new British government under Harold Wilson

Harold Wilson

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx, KG, OBE, FRS, FSS, PC was a British Labour Member of Parliament, Leader of the Labour Party. He was twice Prime Minister of the United Kingdom during the 1960s and 1970s, winning four general elections, including a minority government after the...

announced their intention to hand over power to the Federation of South Arabia in 1968, but that the British military would remain. In 1964, there were around 280 guerrilla attacks and over 500 in 1965. In 1966 the British Government announced that all British forces would be withdrawn at independence. In response, the security situation deteriorated with the creation of the socialist

Socialism

Socialism is an economic system characterized by social ownership of the means of production and cooperative management of the economy; or a political philosophy advocating such a system. "Social ownership" may refer to any one of, or a combination of, the following: cooperative enterprises,...

Front for the Liberation of Occupied South Yemen

Front for the Liberation of Occupied South Yemen

The Front for the Liberation of Occupied South Yemen or was a military organization operating in the Federation of South Arabia in the 60s. As the British tried to exit its Federation of South Arabia colony Abdullah al Asnag created FLOSY...

(FLOSY) which started to attack the NLF in a bid for power, as well as attacking the British.

In January 1967, there were mass riots by NLF and FLOSY supporters in the old Arab quarter of Aden town, which continued until mid February, despite the intervention of British troops. During the period there were many attacks on the troops, and an Aden Airlines Douglas DC-3

Douglas DC-3

The Douglas DC-3 is an American fixed-wing propeller-driven aircraft whose speed and range revolutionized air transport in the 1930s and 1940s. Its lasting impact on the airline industry and World War II makes it one of the most significant transport aircraft ever made...

plane was destroyed in the air with no survivors. At the same time, the members of FLOSY and the NLF were also killing each other in large numbers.

The temporary closure

Yellow Fleet

The Yellow Fleet was the name given to a group of fifteen ships trapped in the Suez Canal from 1967 to 1975 as a result of the Six-Day War. Both sides of the canal had been blocked by ships scuttled by the Egyptians. The name Yellow Fleet derived from their yellow appearance as they were...

of the Suez Canal

Suez Canal

The Suez Canal , also known by the nickname "The Highway to India", is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea. Opened in November 1869 after 10 years of construction work, it allows water transportation between Europe and Asia without navigation...

in 1967 effectively negated the last reason that British had kept hold of the colonies in Yemen, and, in the face of uncontrollable violence, they began to withdraw.

On 20 June 1967, there was a mutiny in the Federation of South Arabia Army, which also spread to the police. Order was restored by the British, mainly due to the efforts of the 1st Battalion Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders

Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders

The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, 5th Battalion The Royal Regiment of Scotland is an infantry battalion of the Royal Regiment of Scotland....

, under the command of Lt-Col. Colin Campbell Mitchell

Colin Campbell Mitchell

Colin Campbell Mitchell was a British Army lieutenant-colonel and politician. He became famous in July 1967 when he led the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders in the British reoccupation of the Crater district of Aden. At that time, Aden was a British colony and the Crater district had briefly been...

.

Nevertheless, deadly guerrilla attacks particularly by the NLF soon resumed against British forces once again, with the British being defeated and driven from Aden by the end of November 1967, earlier than had been planned by British Prime Minister Harold Wilson

Harold Wilson

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx, KG, OBE, FRS, FSS, PC was a British Labour Member of Parliament, Leader of the Labour Party. He was twice Prime Minister of the United Kingdom during the 1960s and 1970s, winning four general elections, including a minority government after the...

and without an agreement on the succeeding governance. Their enemies, the NLF, managed to seize power, with Aden itself under NLF control. The Royal Marines

Royal Marines

The Corps of Her Majesty's Royal Marines, commonly just referred to as the Royal Marines , are the marine corps and amphibious infantry of the United Kingdom and, along with the Royal Navy and Royal Fleet Auxiliary, form the Naval Service...

, who had been the first British troops to occupy Aden in 1839, were the last to leave. The Federation of South Arabia collapsed and Southern Yemen became independent as the People's Republic of South Yemen. The NLF, with the support of the army

Army

An army An army An army (from Latin arma "arms, weapons" via Old French armée, "armed" (feminine), in the broadest sense, is the land-based military of a nation or state. It may also include other branches of the military such as the air force via means of aviation corps...

, attained total control of the new state after defeating the FLOSY and the states of the former Federation in a drawn out campaign of terror

Terrorism

Terrorism is the systematic use of terror, especially as a means of coercion. In the international community, however, terrorism has no universally agreed, legally binding, criminal law definition...

.

Most of the opposing leaders reconciled by 1968, in the aftermath of a final royalist siege of San'a'. In 1970, Saudi Arabia recognized the Yemen Arab Republic and a ceasefire was effected.

A radical (Marxist) wing of the NLF gained power in South Yemen in June, 1969.

1970s

The NLF changed the name of South Yemen on 1 December 1970 to the People's Democratic Republic of YemenPeople's Democratic Republic of Yemen

The People's Democratic Republic of Yemen — also referred to as South Yemen, Democratic Yemen or Yemen — was a socialist republic in the present-day southern and eastern Provinces of Yemen...

(PDRY). In the PDRY, all political parties were amalgamated into the Yemeni Socialist Party

Yemeni Socialist Party

The Yemeni Socialist Party is a political party in Yemen.It was the ruling party in South Yemen, the only Marxist Arab state, before unification in 1990...

(YSP), which became the only legal party. The PDRY established close ties with the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

, People's Republic of China

People's Republic of China

China , officially the People's Republic of China , is the most populous country in the world, with over 1.3 billion citizens. Located in East Asia, the country covers approximately 9.6 million square kilometres...

, Cuba

Cuba

The Republic of Cuba is an island nation in the Caribbean. The nation of Cuba consists of the main island of Cuba, the Isla de la Juventud, and several archipelagos. Havana is the largest city in Cuba and the country's capital. Santiago de Cuba is the second largest city...

, and radical Palestinians.

The major communist powers assisted in the building of the PDRY's armed forces. Strong support from Moscow resulted in Soviet naval forces gaining access to naval facilities in South Yemen.

Unlike East and West Germany

West Germany

West Germany is the common English, but not official, name for the Federal Republic of Germany or FRG in the period between its creation in May 1949 to German reunification on 3 October 1990....

, the two Yemens remained relatively friendly, though relations were often strained. In 1972 it was declared unification would eventually occur.

However, in October 1972 fighting erupted between the North Yemen and the South Yemen; North Yemen supplied by Saudi Arabia and South Yemen by the USSR. Fighting was short-lived and the conflict led to the October 28, 1972 Cairo Agreement, which set forth a plan to unify the two countries.

Fighting broke out again in February and March 1979, with South Yemen allegedly supplying aid to rebels in the north through the National Democratic Front

National Democratic Front (Yemen)

National Democratic Front was founded as an umbrella of various opposition movements in North Yemen on February 2, 1976 in San'a. The five founding organisations of NDF were the Revolutionary Democratic Party of Yemen, Organisation of Revolutionary Resistors of Yemen, the Labour Party, the Popular...

and crossing the border. Southern forces made it as far as the city of Taizz before withdrawing. This conflict was also short-lived.

The war was only stopped by an Arab League

Arab League

The Arab League , officially called the League of Arab States , is a regional organisation of Arab states in North and Northeast Africa, and Southwest Asia . It was formed in Cairo on 22 March 1945 with six members: Egypt, Iraq, Transjordan , Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, and Syria. Yemen joined as a...

intervention. The goal of unity was reaffirmed by the northern and southern heads of state during a summit meeting in Kuwait

Kuwait

The State of Kuwait is a sovereign Arab state situated in the north-east of the Arabian Peninsula in Western Asia. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to the south at Khafji, and Iraq to the north at Basra. It lies on the north-western shore of the Persian Gulf. The name Kuwait is derived from the...

in March 1979.

What the PDRY government failed to tell the YAR government was that it wished to be the dominant power in any unification, and left wing rebels in North Yemen began to receive extensive funding and arms from South Yemen.

1980s

In 1980, PDRY president Abdul Fattah IsmailAbdul Fattah Ismail

Abd al-Fattah Ismail Ali Al-Jawfi was the Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme People's Council, head of state of the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen, and founder, chief ideologue, and first leader of the Yemeni Socialist Party from 21 December 1978 to 21 April 1980.Born in July 1939 in...

resigned and went into exile

Exile

Exile means to be away from one's home , while either being explicitly refused permission to return and/or being threatened with imprisonment or death upon return...

. His successor, Ali Nasir Muhammad

Ali Nasir Muhammad

Ali Nasir Muhammad Husani was twice president of the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen. He served as Chairman of the Presidential Council from 26 June 1978 - 27 December 1978. In April 1980, South Yemeni president Abdul Fattah Ismail resigned and went into exile...

, took a less interventionist stance toward both North Yemen and neighbouring Oman

Oman

Oman , officially called the Sultanate of Oman , is an Arab state in southwest Asia on the southeast coast of the Arabian Peninsula. It is bordered by the United Arab Emirates to the northwest, Saudi Arabia to the west, and Yemen to the southwest. The coast is formed by the Arabian Sea on the...

. On January 13, 1986, a violent struggle began in Aden between Ali Nasir's supporters and supporters of the returned Ismail, who wanted power back. Fighting lasted for more than a month

Month

A month is a unit of time, used with calendars, which was first used and invented in Mesopotamia, as a natural period related to the motion of the Moon; month and Moon are cognates. The traditional concept arose with the cycle of moon phases; such months are synodic months and last approximately...

and resulted in thousands of casualties, Ali Nasir's ouster

Ouster

Ouster may refer to:*A cause of action available to one who is refused access to their concurrent estate*In Dan Simmons' Hyperion universe, Ousters are a branch of humanity that chose to travel/live in space, "between the stars", as opposed to dwelling in planetary systems...

, and Ismail's death

Death

Death is the permanent termination of the biological functions that sustain a living organism. Phenomena which commonly bring about death include old age, predation, malnutrition, disease, and accidents or trauma resulting in terminal injury....

. Some 60,000 people, including the deposed Ali Nasir, fled

Emigration

Emigration is the act of leaving one's country or region to settle in another. It is the same as immigration but from the perspective of the country of origin. Human movement before the establishment of political boundaries or within one state is termed migration. There are many reasons why people...

to the YAR.

Efforts toward unification proceeded from 1988. See also: Aden

Aden

Aden is a seaport city in Yemen, located by the eastern approach to the Red Sea , some 170 kilometres east of Bab-el-Mandeb. Its population is approximately 800,000. Aden's ancient, natural harbour lies in the crater of an extinct volcano which now forms a peninsula, joined to the mainland by a...

, Aden Protectorate

Aden Protectorate

The Aden Protectorate was a British protectorate in southern Arabia which evolved in the hinterland of Aden following the acquisition of that port by Britain in 1839 as an anti-piracy station, and it continued until the 1960s. For administrative purposes it was divided into the Western...

, Federation of South Arabia

Federation of South Arabia

The Federation of South Arabia was an organization of states under British protection in what would become South Yemen. It was formed on 4 April 1962 from the 15 protected states of the Federation of Arab Emirates of the South. On 18 January 1963 it was merged with the crown colony of Aden...

, Hadhramaut

Hadhramaut

Hadhramaut, Hadhramout, Hadramawt or Ḥaḍramūt is the formerly independent Qu'aiti state and sultanate encompassing a historical region of the south Arabian Peninsula along the Gulf of Aden in the Arabian Sea, extending eastwards from Yemen to the borders of the Dhofar region of Oman...

, and the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen

People's Democratic Republic of Yemen

The People's Democratic Republic of Yemen — also referred to as South Yemen, Democratic Yemen or Yemen — was a socialist republic in the present-day southern and eastern Provinces of Yemen...

Although the governments of the PDRY and the YAR declared that they approved a future union in 1972, little progress was made toward unification, and relations were often strained.

In May 1988, the YAR and PDRY governments came to an understanding that considerably reduced tensions including agreement to renew discussions concerning unification, to establish a joint oil exploration area along their undefined border, to demilitarize the border, and to allow Yemenis unrestricted border passage on the basis of only a national identification card.

In November 1989, the leaders of the YAR (Ali Abdullah Saleh

Ali Abdullah Saleh

Field Marshal Ali Abdullah Saleh is the first President of the Republic of Yemen. Saleh previously served as President of the Yemen Arab Republic from 1978 until 1990, at which time he assumed the office of chairman of the Presidential Council of a post-unification Yemen. He is the...

) and the PDRY (Ali Salim al-Baidh

Ali Salim al-Baidh