North Yemen Civil War

Encyclopedia

The North Yemen Civil War was fought in North Yemen

between royalists of the Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen

and factions of the Yemen Arab Republic

from 1962 to 1970. The war began with a coup d'état

carried out by the republican leader, Abdullah as-Sallal

, which dethroned the newly crowned Imam al-Badr and declared Yemen a republic under his presidency. The Imam escaped to the Saudi Arabia

n border and rallied popular support.

On the royalist side Jordan

and Saudi Arabia

supplied military aid, and Britain

gave diplomatic support, while the republicans were supported by Egypt

and allegedly received warplanes from the Soviet Union

.

Both foreign irregular and conventional forces were involved. The Egyptian President

, Gamal Abdel Nasser

, supported the republicans with as many as 70,000 Egyptian troops. Despite several military moves and peace conferences, the war sank into a stalemate. Egypt's commitment to the war is considered to have been detrimental to its performance in the Six-Day War

of June 1967, after which Nasser found it increasingly difficult to maintain his army's involvement and began to pull his forces out of Yemen.

By 1970, King Faisal of Saudi Arabia

recognized the republic after al- Badr refused to cede Najran, Jizan and Aseer to Saudi Arabia in return of continued aid, his famous response was "Their people are the most worthy of it" and sensing the willingness of the coup forces to cede those lands to the Saudis a truce was signed. Egyptian military historians refer to the war in Yemen as their Vietnam, and historian Michael Oren

(current Israeli Ambassador to the U.S) wrote that Egypt's military adventure in Yemen was so disastrous that "the imminent Vietnam War

could easily have been dubbed America's Yemen."

, who had inherited the Yemeni throne in 1948, was known as "Ahmad the devil" by his enemies. In 1955, Iraq

-trained Colonel Ahmad Thalaya led a revolt against him. A group of soldiers under his command surrounded the royal palace of Al Urdhi at Taiz, a fortified stronghold where the Imam lived with his harem, the royal treasure, an arsenal of modern weapons, and a 150 strong palace-guard, and demanded Ahmad's abdication. Ahmad agreed, but demanded that his son, Imam al-Badr succeed him. Thalaya refused, preferring the King's half brother, the Emir Saif el Islam Abdullah, the 48-year-old Foreign Minister. While Abdullah began forming a new government, Ahmad opened the treasury coffers and secretly began buying off the besieging soldiers. After five days, the number of besiegers was reduced from 600 to 40. Ahmad then came out of the palace,wearing a devil's mask and wielding a long scimitar, terrifying the beseigers. He slashed two sentries dead before exchanging the sword for a sub-machine gun and leading his 150 guards onto the roof of the palace to begin a direct attack on the rebels. After 28 hours, 23 rebels and one palace guard were dead and Thalaya gave up. Abdullah was later reported executed, and Thalaya was publicly decapitated.

In March 1958, al-Badr arrived in Damascus

In March 1958, al-Badr arrived in Damascus

to tell Nasser of Yemen's adherence to the UAR

. However, Ahmad was to keep his throne and his absolute power, and the arrangement constituted only a close alliance. In 1959 Ahmad went to Rome

to treat his arthritis, rheumatism, heart trouble and, reportedly, drug addiction. Fights between tribal chieftains erupted, and al-Badr unsuccessfully tried to buy off the dissidents by promising "reforms", including the appointment of a representative council, more army pay and promotions. Upon his return, Ahmad swore to crush the "agents of the Christians". He ordered the decapitation of one of his subjects and the amputation of the left hand and right foot of 15 others, in punishment for the murder of a high official the previous June. Al-Badr was only rebuked for his leniency, but the Yemeni radio stopped broadcasting army officers' speeches, and talks of reforms were silenced.

In June 1961, Ahmad was still recovering from an assassination attempt four months earlier, and moved out of the capital, Taiz, into the pleasure palace of Sala

. Already Defense and Foreign Minister, Badr became acting Prime Minister and Interior Minister as well. Despite being Crown Prince, al-Badr still needed to be picked by the Ulema

in San'a. Al-Badr was not popular with the Ulema due to his association with Nasser, and the Ulema had refused Ahmad's request to ratify Badr's title. Imam Ahmad died on September 18, 1962, and was succeeded by his son, Imam al-Badr. One of al-Badr's first acts was to appoint Colonel Abdullah Sallal, a known socialist and Nasserist, as commander of the palace guard.

Nasser had looked to a regime change in Yemen since 1957 and finally put his desires into practice in January 1962 by giving the Free Yemen Movement office space, financial support, and radio air time. Anthony Nutting

Nasser had looked to a regime change in Yemen since 1957 and finally put his desires into practice in January 1962 by giving the Free Yemen Movement office space, financial support, and radio air time. Anthony Nutting

's biography of Gamal Abdel-Nasser identifies several factors that led the Egyptian President to send expeditionary forces to Yemen. These included the unraveling of the union with Syria

in 1961, which dissolved his United Arab Republic

(UAR), damaging his prestige. A quick decisive victory in Yemen could help him recover leadership of the Arab world

. Nasser also had his reputation as an anti-colonial force, setting his sights on ridding South Yemen, and its strategic port city of Aden

, of British

forces.

Mohamed Heikal

, a chronicler of Egyptian national policy decision making and confidant of Nasser, wrote in For Egypt Not For Nasser, that he had engaged Nasser on the subject of supporting the coup in Yemen. Heikal argued that Sallal's revolution could not absorb the massive number of Egyptian personnel who would arrive in Yemen to prop up his regime, and that it would be wise to consider sending Arab nationalist volunteers from throughout the Middle East to fight alongside the republican Yemeni forces, suggesting the Spanish Civil War

as a template from which to conduct events in Yemen. Nasser refused Heikal's ideas, insisting on the need to protect the Arab nationalist movement. Nasser was convinced that a regiment of Egyptian Special Forces and a wing of fighter-bomber

s would be able to secure the Yemeni republican coup d'état

.

Nasser's considerations for sending troops to Yemen may have included the following: (1) impact of his support to the Algerian War of Independence

from 1954–62; (2) Syria

breaking up from Nasser's United Arab Republic

(UAR) in 1961; (3) taking advantage of a breach in British

and French relations, which had been strained by Nasser's support for the FLN

in Algeria

and primarily for his efforts to undermine the Central Treaty Organization

(CENTO), which caused the downfall of the Iraqi monarchy in 1958; (4) confronting imperialism

, which Nasser saw as Egypt's destiny; (5) guaranteeing dominance of the Red Sea

from the Suez Canal

to the Bab-el-Mandeb

strait; (6) retribution against the Saudi royal family, whom Nasser felt had undermined his union with Syria.

At least four plots were going on in San'a. One was headed by Lieutenant Ali Abdul al Moghny. Another one was conceived by Sallal. His plot merged into a third conspiracy prodded by the Hashid tribal confederation in revenge for Ahmad's execution of their paramount sheik and his son. A fourth plot was shaped by several young princes who sought to get rid of al-Badr but not the imamate. The only men who knew about those plots were the Egyptian chargé d'affaires

At least four plots were going on in San'a. One was headed by Lieutenant Ali Abdul al Moghny. Another one was conceived by Sallal. His plot merged into a third conspiracy prodded by the Hashid tribal confederation in revenge for Ahmad's execution of their paramount sheik and his son. A fourth plot was shaped by several young princes who sought to get rid of al-Badr but not the imamate. The only men who knew about those plots were the Egyptian chargé d'affaires

, Abdul Wahad, and al-Badr himself. The day after Ahmad's death, al-Badr's minister in London, Ahmad al Shami, sent him a telegram urging him not to go to San'a to attend his father's funeral because several Egyptian officers, as well as some of his own, were plotting against him. Al-Badr's private secretary did not pass this message to him, pretending he did not understand the code. Al-Badr may have been saved by the gathering of thousands of men at the funeral. Al-Badr learned of the telegram only later.

A day before the coup Wahad, who claimed to have information from the Egyptian intelligence service, warned al-Badr that Sallal and fifteen other officers, including Moghny, were planning a revolution. Wahad's purpose was to cover himself and Egypt in case the coup failed, to prompt the plotters into immediate action, and drive Sallal and Moghny into a single conspiracy. Sallal got imamic permission to bring in the armed forces. Then, Wahad went to Moghny, and told him that al-Badr had somehow discovered the plot, and that he must act immediately before the other officers would be arrested. He told him that if he could hold San'a, the radio and the airport for three days, the whole of Europe would recognize him.

Sallal ordered that the military academy in San'a go on full alert — opening all armories and issuing weapons to all junior officers and troops. On the evening of September 25, Sallal gathered known leaders of the Yemeni nationalist movement and other officers who had sympathized or participated in the military protests of 1955. Each officer and cell would be given orders and would commence as soon as the shelling of al-Badr's palace began. Key areas that would be secured included Al-Bashaer palace (al-Badr's palace); Al-Wusul palace (Reception area for dignitaries); The radio station; The telephone exchange; Qasr al-Silaah (The Main Armory); and The central security headquarters (Intelligence

and Internal Security).

The battle at the palace continued until guards surrendered to the revolutionaries the following morning. The radio station was first to fall, secured after a loyalist officer was killed and resistance collapsed. The armory was perhaps the easiest target, as a written order from Sallal was sufficient to open the storage facility, beat the royalists, and secure rifles, artillery and ammunition for the resistance. The telephone exchange likewise fell without any resistance. At the Al-Wusul Palace, revolutionary units remained secure under the guise of granting and protecting diplomats and dignitaries staying there to greet the new Imam of Yemen. By late morning on September 26, all areas of San'a were secure and the radio broadcast that Imam al-Badr had been overthrown by the new revolutionary government in power. Revolutionary cells in the cities of Taiz, Al-Hujja and the port city of Hodeida then began securing arsenals, airports and port facilities.

Al-Badr and his personal servants managed to escape through a door in the garden wall in the back of the palace. Because of the curfew declared, they had to avoid the main streets. They decided to escape individually and meet in the village of Gabi al Kaflir, where they were reunited after a forty-five minute walk. Sallal had to defeat a fellow revolutionary, Al-Baidani, an intellectual holding a doctorate degree, who did not share in Nasser's vision. On September 28, the radio announced al-Badr's death. Sallal gathered tribesmen in San'a and proclaimed: "The corrupt monarchy which ruled for a thousand years was a disgrace to the Arab nation and to all humanity. Anyone who tries to restore it is an enemy of God and man!" By then, he had learned that al-Badr was still alive and had made his way to Saudi Arabia.

Al-Badr and his personal servants managed to escape through a door in the garden wall in the back of the palace. Because of the curfew declared, they had to avoid the main streets. They decided to escape individually and meet in the village of Gabi al Kaflir, where they were reunited after a forty-five minute walk. Sallal had to defeat a fellow revolutionary, Al-Baidani, an intellectual holding a doctorate degree, who did not share in Nasser's vision. On September 28, the radio announced al-Badr's death. Sallal gathered tribesmen in San'a and proclaimed: "The corrupt monarchy which ruled for a thousand years was a disgrace to the Arab nation and to all humanity. Anyone who tries to restore it is an enemy of God and man!" By then, he had learned that al-Badr was still alive and had made his way to Saudi Arabia.

Egyptian General Ali Abdul Hameed was dispatched by plane, and arrived on September 29 to assess the situation and needs of the Yemeni Revolutionary Command Council. Egypt sent a battalion of Special Forces (Saaqah) on a mission to act as personal guards for Sallal. They arrived at Hodeida on October 5. Fifteen days after he had left San'a, al-Badr sent a man ahead to the Saudi Arabia to announce that he was alive. He then went there himself, crossing the border near Khobar

, at the north-western edge of the kingdom.

, fearing Nasserist

encroachment, moved troops along its border with Yemen, as the Jordanian monarch dispatched his Army chief of staff for discussions with al-Badr's uncle, Prince Hassan. Between October 2–8 four Saudi cargo planes left Saudi Arabia loaded with arms and military material for Yemeni royalist tribesmen; however, the pilots defected to Aswan

. Ambassadors from Bonn

, London

, Washington D.C. and Amman

supported the Imam while ambassadors from Cairo

, Rome

and Belgrade

declared support for the republican revolution. The USSR was the first nation to recognize the new republic, and Nikita Khrushchev

cabled Sallal: "Any act of aggression against Yemen will be considered an act of aggression against the Soviet Union."

The United States was concerned that the conflict might spread to other parts of the Middle East. President John F. Kennedy

rushed off notes to Nasser, Feisal, Hussein and Sallal. His plan was that Nasser's troops should withdraw from Yemen while Saudi Arabia and Jordan halted their aid to the Imam. Nasser agreed to pull out his forces only after Jordan and Saudi Arabia "stop all aggressive operations on the frontiers". Feisal and Hussein rejected Kennedy's plan, since it would involve US recognition of the "rebels". They insisted that the US should withhold recognition of Sallal's Presidency since the Imam might still regain control of Yemen, and that Nasser had no intention of pulling out. The Saudis argued that Nasser wanted their oil fields and was hoping to use Yemen as a springboard for revolt in the rest of the Arabian peninsula. King Hussein of Jordan

was also convinced that Nasser's target was Saudi Arabia's oil, and that if the Saudis went, he would be next.

Sallal declared "I warn America that if it does not recognize the Yemen Arab Republic, I shall not recognize it!". US Chargé d'Affaires

in Taiz, Robert Stookey, reported that the republican regime was in full control of the country, except in some border areas. However, the British government was insisting on the strength of the Imam's tribal support. A letter written by President Kennedy to Faisal dated October 25, which was kept confidential until January 1963, said: "You may be assured of full US support for the maintenance of Saudi Arabian integrity". American jet aircraft twice staged shows of force in Saudi Arabia. The first involved six F-100

jets staging stunt-flying demonstrations over Riyadh

and Jeddah

; on the second, two jet bombers and a giant jet transport, while returning to their base near Paris

after a visit to Karachi

, Pakistan

, put on a demonstration over Riyadh.

Sallal proclaimed Yemen's "firm policy to honor its international obligations", including a 1934 treaty pledging respect for Britain's Aden Protectorate

. Nasser promised to "start gradual withdrawal" of its 18,000-man force, "provided Saudi and Jordanian forces also retire from border regions", but would leave his technicians and advisers behind. On December 19, the US became the 34th nation to recognize the Yemen Arab Republic. United Nations

recognition followed that of the US by a day. The UN continued to consider the republic the only authority in the land and completely ignored the royalists.

Britain, with its commitment to South Arabia and its base in Aden, considered the Egyptian invasion a real threat. Recognition of the republic posed a problem to several treaties Britain had signed with the sheiks and sultans of the South Arabian Federation. Saudi Arabia urged the British to identify themselves with the royalists. On the other hand, there were some in the British Foreign Office who believed Britain could buy security for Aden by recognizing the republic. However, Britain eventually decided not to recognize. Iran

, Turkey

and most of western Europe also withheld recognition. The republic did receive the recognition of West Germany

, Italy, Canada and Australia, as well as the remaining Arab governments, Ethiopia

and the entire communist bloc.

A week after the American recognition, Sallal boasted at a military parade the republic had rockets that could strike "the palaces of Saudi Arabia", and in early January the Egyptians again bombed and strafed Najran

, a Saudi Arabian city near the Yemenite border. The US responded with another aerial demonstration over Jeddah and a destroyer joined on January 15. The US reportedly agreed to send antiaircraft batteries and radar-control equipment to Najran. In addition, Ralph Bunche

was sent to Yemen, where he met with Sallal and Egyptian Field Marshal Abdel Hakim Amer

. On March 6 Bunche was in Cairo, where Nasser reportedly assured him that he would withdraw his troops from Yemen if the Saudis would stop supporting the royalists.

, the United States Department of State

sought the help of ambassador Ellsworth Bunker

. His mission was based on a decision made by the National Security Council

, which was conceived by McGeorge Bundy

and Robert Komer

. The idea behind what became known as "Operation Hard-surface" was to trade American protection (or the appearance of it) for a Saudi commitment to halt aid to the royalists, on the basis of which the Americans would get Nasser to withdraw his troops. The operation would consist of "eight little planes."

Bunker arrived in Riyadh on March 6. Faisal refused Bunker's offer, which was also hitched to pledges of reform. The original instructions for Operation Hard-surface were that American planes would "attack and destroy" any intruders over Saudi air space, but were later changed to read that the Saudis could defend themselves if attacked. Bunker evidently stuck to the original formula and stressed that if only Faisal would halt his aid to the royalists, the US would be able pressure Nasser to withdraw. Faisal eventually accepted the offer, and Bunker went on to meet with Nasser in Beirut

, where the Egyptian President repeated the assurance he had given Bunche.

The Bunche and Bunker mission gave birth to the idea of an observer mission to Yemen, which eventually became the United Nations Yemen Observation Mission

. The U.N. observer team, which would be set up by the former UN Congo

commander, Swedish

Major General Carl von Horn. His disengagement agreement called for (1) Establishment of a demilitarized zone extending twenty kilometers on either side of a demarcated Saudi Arabian Yemen border, from which all military equipment was to be excluded; (2) Stationing of UN observers within this zone on both sides of the border to observe, report and prevent any continued attempt by the Saudis to supply royalist forces.

On April 30, von Horn was sent to discover what kind of force was required. A few days later, he met with Amer in Cairo and found out that Egypt had no intention of drawing all her troops from Yemen. After a few more days, he was told by the Saudi deputy Minister for Foreign Affairs, Omar Saqqaff, that the Saudis would not accept any attempt by Egypt to leave security forces after their withdrawal. Saudi Arabia had already been cutting back on its support to the royalists, in part because Egypt's projected plan for unity with Syria

and Iraq

made Nasser seem too dangerous. By that time, the war cost Egypt $1,000,000 a day and nearly 5,000 casualties. Though promising to remove her troops, Egypt had the privilege of leaving an unspecified number for the "training" of Yemen's republican army.

In June, von Horn went to San'a, unsuccessfully trying to achieve the objective of 1) ending Saudi aid to the royalists, 2) creating a 25-mile demilitarized strip along the Saudi border, and 3) supervising the phased withdrawal of the Egyptian troops. In September, von Horn cabled his resignation to Thant, who announced that the mission would continue, due to "oral assurances" by Egypt and Saudi Arabia to continue financing it. The number of Egyptian troops increased, and in the end of January, the "Hard-surface" squadron was withdrawn after a wrangle with Faisal. On September 4, 1964, the UN admitted failure and withdrew its mission.

Imam al-Badr led his campaign with the princes of the house of Hamidaddin. Those included Hassan bin Yahya, who had come from New York, Mohamed bin Hussein, Mohamed bin Ismail, Ibrahim al Kipsy, and Abdul Rahman bin Yahya. At fifty-six, Hassan bin Yahya was the oldest and most distinguished. Prince Hassan was made Prime Minister and Commander-in-Chief. The Imam was joined by his childhood pen pal, American Bruce Conde

Imam al-Badr led his campaign with the princes of the house of Hamidaddin. Those included Hassan bin Yahya, who had come from New York, Mohamed bin Hussein, Mohamed bin Ismail, Ibrahim al Kipsy, and Abdul Rahman bin Yahya. At fifty-six, Hassan bin Yahya was the oldest and most distinguished. Prince Hassan was made Prime Minister and Commander-in-Chief. The Imam was joined by his childhood pen pal, American Bruce Conde

, who set up the post office and would later rise to the rank of general in the Royalist forces.

In 1963, the Saudis spent $15 million to equip royalist tribes, hire hundreds of European mercenaries, and establish their own radio station. Pakistan

, which saw a chance to make money in the conflict, extended rifles to the royalists. Remnants of the Imam's Army also had elements of the Saudi National Guard fight alongside its ranks. Iran

subsidized royalist forces on and off, as the Shah

felt compelled to provide al-Badr (a Shiite Zeidi) with financing. The British

allowed convoys of arms to flow through one of its allies in Northern Yemen, the Sheriff of Beijan, who was protected by the British administration in Aden

. British military planes conduced night operations to resupply al-Badr's forces. The MI6 was responsible for contacting the royalists, and used the services of a private company belonging to Colonel David Stirling

, founder of the Special Air Service

(SAS), who recruited dozens of former SAS men as advisors to the royalists. Britain participated in a $400 million British air defense program for Saudi Arabia. The Lyndon Johnson administration was more willing than Kennedy's to support long-range plans in support of the Saudi army. In 1965, the US authorized an agreement with the Corps of Engineers

to supervise the construction of military facilities and in 1966 it sponsored a $100 million program which provided the Saudi forces with combat vehicles, mostly trucks. Faisal also initiated an Islamic alignment called the Islamic Conference, to counter Nasser's Arab socialism

.

The tribes of Southern Saudi Arabia and Northern Yemen were closely linked, and the Saudis enticed thousands of Yemeni workers in Saudi Arabia to assist the royalist cause. In addition to the Saudis and British, the Iraqis also sent plane loads of Baathist Yemenis to undermine Sallal's regime. The royalists fought for the Imam despite his father's unpopularity. One sheik said "The Imams have ruled us for a thousand years. Some were good and some bad. We killed the bad ones sooner or later, and we prospered under the good ones". The hill tribes were Shia, like the Imam, while the Yemenis of the coast and the south were Sunni, as were most Egyptians. President Sallal was himself a mountain Shia fighting with lowland Sunnis. Al-Badr himself was convinced that he was Nasser's biggest target, saying "Now I'm getting my reward for befriending Nasser. We were brothers, but when I refused to become his stooge, he used Sallal against me. I will never stop fighting. I will never go into exile. Win or lose, my grave will be here".

The tribes of Southern Saudi Arabia and Northern Yemen were closely linked, and the Saudis enticed thousands of Yemeni workers in Saudi Arabia to assist the royalist cause. In addition to the Saudis and British, the Iraqis also sent plane loads of Baathist Yemenis to undermine Sallal's regime. The royalists fought for the Imam despite his father's unpopularity. One sheik said "The Imams have ruled us for a thousand years. Some were good and some bad. We killed the bad ones sooner or later, and we prospered under the good ones". The hill tribes were Shia, like the Imam, while the Yemenis of the coast and the south were Sunni, as were most Egyptians. President Sallal was himself a mountain Shia fighting with lowland Sunnis. Al-Badr himself was convinced that he was Nasser's biggest target, saying "Now I'm getting my reward for befriending Nasser. We were brothers, but when I refused to become his stooge, he used Sallal against me. I will never stop fighting. I will never go into exile. Win or lose, my grave will be here".

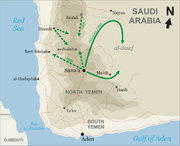

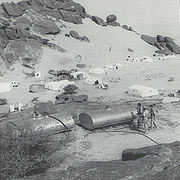

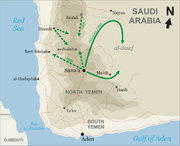

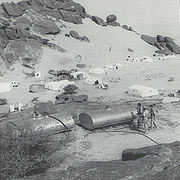

Al-Badr had formed two royalist armies - one under his uncle Prince Hassan in the east and one under his own control in the west. Both armies controlled most of the north and east of Yemen, including the towns of Harib and Marib. The provincial capital of Northern Yemen, Sadah, which would have given the Imam a key strategic road towards the main capital San'a, was controlled by the republicans. There were also areas like the town of Hajjah

, where the royalists controlled the mountains while the Egyptians and republicans controlled the town and fortress. Mercenaries

from France, Belgium

and England, who had fought in Rhodesia

, Malaya

, Indochina

and Algeria

, were sent to assist the Imam in planning, training and giving the irregular forces the ability to communicate with one another and the Saudis. They trained tribesmen in the use of antitank weapons

, such as the 106mm gun and in mining techniques. The numbers of mercenaries are estimated in the hundreds, although Egyptian sources at the time reported 15,000. Royalist tactics were confined to guerilla warfare, isolating conventional Egyptian and republican forces, and conducting attacks on supply lines.

Three decades after the war, former Mossad

Three decades after the war, former Mossad

director, Shabtai Shavit

, and Ariel Sharon

both said Israel had been clandestinely involved in Yemen. Some of the royalist air drops were aided by the Israeli Air Force

(IAF). The aircraft were contracted privately to the British mercenary operation and were either using Israeli air bases or Israeli transport planes themselves making the drops.

According to "Haaretz" newspaper, one of the SAS advisers, Tony Boyle, contacted David Karon, the head of the Middle East department in the Tevel (Cosmos) section of the Mossad, and met with IAF commander Ezer Weizman

and his officers. It was decided that the airdrops would be made. The Israeli aircraft flew along the Saudi coastline. The Saudis did not have radar systems, and would later claim they were not aware of the airlifts. The Israeli planes would make the drops and then refuel in French Somaliland

(now Djibouti

) and return to Israel. The airlifts were originally codenamed "Operation Gravy", but were later renamed "Operation Porcupine". The IAF's largest transport plane, the Stratofreighter, was recruited for the operation. The first flight took off in March 1964 from Tel Nof Airbase

. During the sixth flight, Boyle suggested that the IAF would also bomb San'a. Weizman supported the idea and plans were made, but the Israel Defense Forces

Chief of Staff (Ramatkal

) Yitzhak Rabin

and Israeli Prime Minister, Levi Eshkol

, denied him. The operation went on over a period of slightly more than two years, during which the Stratofreighter carried out 14 nighttime sorties from Tel Nof to Yemen. The Mossad also operated several agents in Yemen. One of them, Baruch Mizrahi, was caught in 1967 and was imprisoned in Egypt. He was released in a prisoner exchange between Egypt and Israel following the Yom Kippur War

in 1973.

Anwar Sadat

Anwar Sadat

was convinced that a regiment reinforced with aircraft could firmly secure Al-Sallal and his free officer movement, but within three months of sending troops to Yemen, Nasser realized that this would require a larger commitment than anticipated. A little less than 5,000 troops were sent in October 1962. Two months later, Egypt had 15,000 regular troops deployed. By late 1963, the number was increased to 36,000; and in late 1964, the number rose to 50,000 Egyptian troops in Yemen. In late 1965, the Egyptian troop commitment in Yemen was at 55,000 troops, which were broken into 13 infantry regiments of one artillery division, one tank division and several Special Forces as well as paratroop regiments. Ahmed Abu-Zeid, who served as Egypt's ambassador to royalist Yemen from 1957 to 1961, sent numerous reports on Yemen that did not reach Ministry of Defense officials. He warned Egyptian officials in Cairo

, including Defense Minister Amer, that the tribes were difficult and had no sense of loyalty or nationhood. He opposed sending Egyptian combat forces and, arguing that only money and equipment be sent to the Yemeni Free Officers, and warned that the Saudis would finance the royalists.

All the Egyptian field commanders complained of a total lack of topographical maps causing a real problem in the first months of the war. Commanders had difficulty planning military operations effectively or sending back routine and casualty reports without accurate coordinates. Field units were given maps that were only of use for aerial navigation. Chief of Egyptian Intelligence, Salah Nasr

, admitted that information on Yemen was nonexistent. Egypt had not had an embassy in Yemen since 1961; therefore when Cairo requested information from the US ambassador to Yemen, all he provided was an economic report on the country.

In 1963 and 1964 the Egyptians had five squadrons of aircraft in Yemen at airfields near San'a and Hodeida. They were using Yak-11

In 1963 and 1964 the Egyptians had five squadrons of aircraft in Yemen at airfields near San'a and Hodeida. They were using Yak-11

piston-engined fighters, MiG-15 and MiG-17 jet fighters, Ilyushin Il-28

twin-engined bombers, Ilyushin Il-14

twin-engined transports and Mil Mi-4

transport helicopters. They were also flying four-engined Tupolev

bombers from bases in Egypt, such as Aswan

. All the air crew were Egyptian, except for the Tupolev bombers which were thought to have mixed Egyptian and Russian personnel. The Ilyushin transports flying between Egypt and Hodeida had Russian crews. Throughout the war, the Egyptians relied on airlift

. In January 1964, when royalist forces placed San'a under siege, Egyptian Antonov

heavy-lift cargo planes airlifted tons of food and kerosene into the region. The Egyptians estimate that hundreds of millions of dollars were spent to equip Egyptian and republican Yemeni forces, and in addition, Moscow

refurbished the Al-Rawda Airfield outside San'a. The politburo

saw a chance to gain a toehold on the Arabian Peninsula and accepted hundreds of Egyptian officers to be trained as pilots for service in the Yemen War.

Egyptian air and naval forces began bombing and shelling raids in the Saudi southwestern city of Najran

and the coastal town of Jizan

, which were staging points for royalist forces. In response, the Saudis purchased a British Thunderbird air defense system

and developed their airfield in Khamis Mushayt. Riyadh

also attempted to convince Washington to respond on its behalf. President Kennedy sent only a wing of jet fighters and bombers to Dhahran

Airbase, demonstrating to Nasser the seriousness of American commitment to defending U.S. interests in Saudi Arabia.

The Egyptian General Staff

The Egyptian General Staff

divided the Yemen War into three operational objectives. The first was the air phase, it began with jet trainers modified to strafe and carry bombs and ended with three wings of fighter-bombers, stationed near the Saudi-Yemeni border. Egyptian sorties went along the Tiahma Coast of Yemen and into the Saudi towns of Najran

and Jizan

. It was designed to attack royalist ground formations and substitute the lack of Egyptian formations on the ground with high-tech air power. In combination with Egyptian air strikes, a second operational phase involved securing major routes leading to San'a, and from there secure key towns and hamlets. The largest offensive based on this operational tactic was the March 1963 "Ramadan

Offensive" that lasted until February 1964, focused on opening and securing roads from San'a to Sadah to the North, and San'a to Marib to the East. The success of the Egyptian forces meant that royalist resistance could take refuge in hills and mountains to regroup and carry out hit-and-run offensives against republican and Egyptian units controlling towns and roads. The third strategic offensive was the pacification of tribes and their enticement to the republican government, meaning the expenditures of massive amounts of funds for humanitarian needs and outright bribery of tribal leaders.

The Ramadan offensive began in February 1963 when Amer and Sadat arrived in San'a. Amer asked Cairo to double the 20,000 men in Yemen, and in early February the first 5,000 of the reinforcement arrived. On February 18 a task force of fifteen tanks, twenty armored cars, eighteen trucks and numerous jeeps took off from San'a' moving northwards, heading for Sadah. More garrison troops followed. A few days later another task force, spearheaded by 350 men in tanks and armored cars, struck out from Sadah southeastwards toward Marib. The maneuvered into the Rub al-Khali desert, perhaps well into Saudi territory, and there they were built up by an airlift. Then they headed westwards. On February 25 they occupied Marib and on March 7 they took Harib. A royalist force of 1,500 men ordered down from Najran failed to stop them on their way out from Sadah. The royalist commander at Harib fled to Beihan

The Ramadan offensive began in February 1963 when Amer and Sadat arrived in San'a. Amer asked Cairo to double the 20,000 men in Yemen, and in early February the first 5,000 of the reinforcement arrived. On February 18 a task force of fifteen tanks, twenty armored cars, eighteen trucks and numerous jeeps took off from San'a' moving northwards, heading for Sadah. More garrison troops followed. A few days later another task force, spearheaded by 350 men in tanks and armored cars, struck out from Sadah southeastwards toward Marib. The maneuvered into the Rub al-Khali desert, perhaps well into Saudi territory, and there they were built up by an airlift. Then they headed westwards. On February 25 they occupied Marib and on March 7 they took Harib. A royalist force of 1,500 men ordered down from Najran failed to stop them on their way out from Sadah. The royalist commander at Harib fled to Beihan

, on the British-protected side of the border. In the battle of El Argoup, 25 miles southeast of San'a, 500 royalists under Prince Abdullah's commanded attacked an Egyptian position on top of a sheer-sided hill that was fortified with six Soviet T-54 tanks, a dozen armored cars and entrenched machine guns. The royalists advanced in a thin skirmish line and were plastered by artillery, mortars and strafing planes. They replied with rifles, one mortar with 20 rounds, and a bazooka with four rounds. The battle lasted a week and cost the Egyptians three tanks, seven armored cars and 160 dead. The Egyptians were now in positions from which they could hope to interdict the royalist movement of supplies in the mountains north and east of San'a'.

In the beginning of April the royalists held a conference with Faisal in Riyadh. They decided to adopt new tactics, including attempts to get supplies around the positions now held by the Egyptians by using camels instead of trucks to cross the mountains to reach the positions east of San'a. Camel caravans from Beihan would swing into the Rub al-Khali and enter Yemen north of Marib. It was also decided that the royalists must now strengthen their operations west of the mountains with three "armies". By the end of April, they began to recover and claimed to have regained some of the positions the Egyptians had taken in the Jawf, particularly the small but strategic towns of Barat and Safra, both in the mountains between Sadah and the Jawf, and were able to move freely in the eastern Khabt desert. In the Jawf they claimed to have cleaned up all Egyptian strong-points except Hazm, and in the west the town of Batanah.

. In two days, the attackers advanced about twelve miles, before being repelled by a counter-attack. The royalists admitted about 250 casualties. Next, the Egyptians attacked Sudah, about 100 miles north-west of San'a. They used the unpopularity of the local royalist commander to bribe several local sheiks and occupied the town unopposed. After a month, the sheiks sent delegations to al-Badr soliciting pardons and asking for guns and money with which to fight the Egyptians. Al-Badr sent new forces and managed to regain the surroundings of Sudah, though not the town itself.

On August 15, the Egyptians launched an offensive from their major north-western base in Haradh. They had 1,000 troops and about 2,000 republicans. The plan, as interpreted by British intelligence, seemed to have been to cut the thirty-mile track southward through the mountains from the Saudi border at Khoubah to al-Badr's headquarters in the Qara mountains near Washa, and then to split into two task forces, one moving east through Washa to the headquarters and the other north-eastwards along the track to the Saudi border below the Razih mountains. The Egyptians began their move on Saturday morning, moving along the Haradh and Tashar ravines. On Saturday and Sunday afteroons they were caught in heavy rain and their vehicles, including twenty tanks and about forty armored cars sank axle deep into the mud. The defenders left them alone until Monday at dawn. Al-Badr left his headquarters at three that morning with 1,000 men to direct a counter attack in the Tashar ravine, while Abdullah Hussein attacked in the Haradh ravine.

On August 15, the Egyptians launched an offensive from their major north-western base in Haradh. They had 1,000 troops and about 2,000 republicans. The plan, as interpreted by British intelligence, seemed to have been to cut the thirty-mile track southward through the mountains from the Saudi border at Khoubah to al-Badr's headquarters in the Qara mountains near Washa, and then to split into two task forces, one moving east through Washa to the headquarters and the other north-eastwards along the track to the Saudi border below the Razih mountains. The Egyptians began their move on Saturday morning, moving along the Haradh and Tashar ravines. On Saturday and Sunday afteroons they were caught in heavy rain and their vehicles, including twenty tanks and about forty armored cars sank axle deep into the mud. The defenders left them alone until Monday at dawn. Al-Badr left his headquarters at three that morning with 1,000 men to direct a counter attack in the Tashar ravine, while Abdullah Hussein attacked in the Haradh ravine.

Meanwhile, the Egyptians had planned a coordinated drive from Sadah to the southwest, below the Razih mountains, hoping to link up with the force coming from Haradh. They were counting on a local sheik, whose forces were to supposed to join 250 Egyptian parachutists. The sheik failed to deliver, and the parachutists made their way back to Sadah, suffering losses from snipers on the way. Al-Badr had sent radio messages and summonses by runner in all directions calling for reinforcement. He asked reserve forces training in the Jawf to arrive in trucks mounting 55- and 57-millimeter cannon and 81 millimeter mortars and heavy machine guns. They arrived within forty-eight hours, in time to face the attackers. They outflanked the Egyptian columns, still stuck in mud in the ravines. They later announced they had knocked out ten of the Egyptian tanks and about half of their armored cars, and claimed to have shot down an Ilyushin bomber. The royalists also carried out two supporting movements. One was a raid on Jihana, in which several staff officers were killed. The second was an attempt, involving British advisors and French and Belgian mercenaries from Katanga

, to bombard San'a from a nearby mountain peak. Other diversionary operations included raids on Egyptian aircraft and tanks at the south airport of San'a and a mortar at the Egyptian and republican residence in a suburb of Taiz. Although the Egyptians managed to drive al-Badr out of his headquarters to a cave on Jabal Shedah, they could not close the Saudi border. They declared victory on the radio and on the press, but were obliged to agree to a ceasefire on the upcoming Erkwit conference on November 2.

. By that time Egypt had 40,000 troops in Yemen and had suffered an estimated 10,000 casualties. In their official communiqué the two leaders promised to 1) cooperate fully to solve the existing differences between the various factions in Yemen, 2) work together in preventing armed clashes in Yemen, and 3) reach a solution by peaceful agreement. The communiqué was widely hailed in the Arab world, and Washington called it a "statesmanlike action" and a "major step toward eventual peaceful settlement of the long civil war." Nasser and Faisal warmly embraced at Alexandria's airport and called each other "brother". Faisal said he was leaving Egypt "with my heart brimming with love for President Nasser."

On November 2, at a secret conference in Erkwit, Sudan

, the royalists and republicans declared a ceasefire effective at 1:00 PM on Monday, November 8. Tribesmen of both sides celebrated the decision until that day, and for two days after it went into effect, they fraternized at several places. On November 2 and 3, nine royalists and nine republicans, with a Saudi and an Egyptian observer, worked out the terms. A conference of 168 tribal leaders was planned for November 23. For the royalists, the conference was to become an embryo national assembly that would name a provisional national executive of two royalists, two republicans and one neutral, to administer the country provisionally and to plan a plebiscite. Until that plebiscite, which would decide whether Yemen would be a monarchy or a republic, both Sallal and al-Badr were to step aside. At the end of the two days the Egyptians resumed their bombing of royalist positions. The conference planned for November 23 was postponed to the 30th, then indefinitely. The republicans blamed the royalists for not arriving, while the royalists blamed the Egyptian bombings.

Between December 1964 and February 1965 the royalists discerned four Egyptian attempts to drive directly into the Razih mountains. The intensity of these thrusts gradually diminished, and it was estimated that the Egyptians lost 1,000 men killed, wounded and taken prisoner. Meanwhile, the royalists were building up an offensive. The Egyptian line of communications went from San'a to Amran, then Khairath, where it branched off north-eastwards to Harf. From Harf it turned due south to Farah, and then South-eastwards to Humaidat, Mutamah and Hazm. From Hazm it led south-eastwards to Marib and Harib. A military convoy went over this route twice a month. Since the royalists had closed the direct route across the mountains from San'a to Marib, the Egyptians had no other way.

Between December 1964 and February 1965 the royalists discerned four Egyptian attempts to drive directly into the Razih mountains. The intensity of these thrusts gradually diminished, and it was estimated that the Egyptians lost 1,000 men killed, wounded and taken prisoner. Meanwhile, the royalists were building up an offensive. The Egyptian line of communications went from San'a to Amran, then Khairath, where it branched off north-eastwards to Harf. From Harf it turned due south to Farah, and then South-eastwards to Humaidat, Mutamah and Hazm. From Hazm it led south-eastwards to Marib and Harib. A military convoy went over this route twice a month. Since the royalists had closed the direct route across the mountains from San'a to Marib, the Egyptians had no other way.

The royalists under the command of Prince Mohamed's objective was to cut the Egyptians' line and force them to withdraw. They intended to take over the garrisons along this line and establish positions from which they could interdict the Egyptian movement. They had prepared the attack with the help of the Nahm tribe, who tricked the Egyptians into believing that they were their allies and would take care of the mountain pass known as Wadi Humaidat themselves. The royalist deal was that the Nahm would be entitled to loot the ambushed Egyptians. The Egyptians may have suspected something was up, as they sent a reconnaissance aircraft over the area a day before the attack. The royalists thus occupied two mountains known as Asfar and Ahmar and installed 75-Millimeter guns and mortars overlooking the Wadi. On April 15, the day after the last Egyptian convoy went through, the royalists launched a surprise attack. Both forces numbered at only a couple of thousands. The guns positioned on Asfar and Ahmar opened fire, and then the Nahm came out from behind the rocks. Finally, Prince Mohamed's troops followed. This time, the royalists' operation was fully coordinated by radio. Some of the Egyptians surrendered without resistance, others fled to Harah 800 yards to the north. Both sides brought reinforcements and the battle shifted between Harf and Hazm.

Meanwhile, Prince Abdullah bin Hassan began to raid Egyptian positions north-east of San'a at Urush, Prince Mohamed bin Mohsin was attacking the Egyptians with 500 men west of Humaidat, Prince Hassan struck out from near Sadah and Prince Hassan bin Hussein moved from Jumaat, west of Sadah, to within mortar-firing distance of the Egyptian airfield west of Sadah. Fifty Egyptians surrendered at Mutanah, near Humaidat. They were eventually allowed to evacuate to San'a with their arms. Mohamed's policy was to keep officers as prisoners for exchange, and to allow soldiers to go in return for their arms. Three to five thousand Egyptian troops in garrisons on the eastern slopes of the mountains and in the desert now had to be supplied entirely by air.

The royalist radio tried to widen the split in republican ranks by promising amnesty to all non-royalists once the Egyptians were withdrawn. Al-Badr also promised a new form of government: "a constitutionally democratic system" ruled by a "national assembly elected by the people of Yemen". At Sallal's request, Nasser provided him with ammunition and troop reinforcements by transport plane from Cairo. By August, the royalists had seven "armies", each varying in strength between 3,000 and 10,000 men, with a total somewhere between 40,000 and 60,000. There were also five or six times as many armed royal tribesmen, and the regular force under Prince Mohamed. In early June they moved into Sirwah in eastern Yemen. On June 14 they entered Qaflan and on July 16 they occupied Marib. According to official Egyptian army figures, they had 15,194 killed. The war was costing Egypt $500,000 a day. The royalists had lost an estimated 40,000 dead. In late August, Nasser decided to get the Soviets more involved in the conflict. He convinced them to cancel a $500 million debt he had incurred and provide military aid to the republicans. In early May, Sallal fired his Premier, General Hassan Amri, and appointed Ahmed Noman in his place. Noman was considered a moderate who believed in compromise. He had resigned as president of the republican Consultative Council in December in protest against Sallal's "failure to fulfill the people's aspirations". Noman's first act was to name a new 15-man Cabinet, maintaining an even balance between Yemen's two main tribal groupings, the mountain Zeidis, who are mostly royalist, and the Shafis, who are mostly republican.

The royalist radio tried to widen the split in republican ranks by promising amnesty to all non-royalists once the Egyptians were withdrawn. Al-Badr also promised a new form of government: "a constitutionally democratic system" ruled by a "national assembly elected by the people of Yemen". At Sallal's request, Nasser provided him with ammunition and troop reinforcements by transport plane from Cairo. By August, the royalists had seven "armies", each varying in strength between 3,000 and 10,000 men, with a total somewhere between 40,000 and 60,000. There were also five or six times as many armed royal tribesmen, and the regular force under Prince Mohamed. In early June they moved into Sirwah in eastern Yemen. On June 14 they entered Qaflan and on July 16 they occupied Marib. According to official Egyptian army figures, they had 15,194 killed. The war was costing Egypt $500,000 a day. The royalists had lost an estimated 40,000 dead. In late August, Nasser decided to get the Soviets more involved in the conflict. He convinced them to cancel a $500 million debt he had incurred and provide military aid to the republicans. In early May, Sallal fired his Premier, General Hassan Amri, and appointed Ahmed Noman in his place. Noman was considered a moderate who believed in compromise. He had resigned as president of the republican Consultative Council in December in protest against Sallal's "failure to fulfill the people's aspirations". Noman's first act was to name a new 15-man Cabinet, maintaining an even balance between Yemen's two main tribal groupings, the mountain Zeidis, who are mostly royalist, and the Shafis, who are mostly republican.

By August, the war was costing Nasser $1,000,000 a day, when he arrived in Jedda harbor aboard his presidential yacht Hurriah (Freedom) to negotiate with Faisal. It was Nasser's first visit to Saudi Arabia since 1956. At the request of the Egyptians, due to assassination rumors, the banners and flags normally put up to celebrate a visiting dignitary were omitted, the sidewalks were cleared of people, and the car was a special bulletproof model. On the evening of his arrival, Nasser was welcomed at a banquet and reception for 700 guests. In less than 48 hours they reached full agreement. Once the agreement was signed, Faisal embraced Nasser and kissed him on both cheeks. The agreement provided for

By August, the war was costing Nasser $1,000,000 a day, when he arrived in Jedda harbor aboard his presidential yacht Hurriah (Freedom) to negotiate with Faisal. It was Nasser's first visit to Saudi Arabia since 1956. At the request of the Egyptians, due to assassination rumors, the banners and flags normally put up to celebrate a visiting dignitary were omitted, the sidewalks were cleared of people, and the car was a special bulletproof model. On the evening of his arrival, Nasser was welcomed at a banquet and reception for 700 guests. In less than 48 hours they reached full agreement. Once the agreement was signed, Faisal embraced Nasser and kissed him on both cheeks. The agreement provided for

, Nasser conceded that "We are facing difficulties. We must all work harder and make sacrifices. I have no magic button that I can push to produce the things you want". Premier Zakaria Mohieddin

raised Egypt's income tax, added a "defense tax" on all sales, and boosted tariffs on nonessential imports. He also hiked the cost of luxury goods 25% and set low price ceilings on most foodstuffs. He sent 400 plainclothesmen to Cairo's to arrest 150 shopkeepers for price violations. In March 1966, the Egyptian forces, now numbering almost 60,000, launched their biggest offensive. The royalists counterattacked but the stalemate resumed. Egyptian-supported groups executed sabotage bombings in Saudi Arabia.

In a speech on May Day

, 1966, Nasser said the war was entering a new phase. He launched what he called a "long-breath strategy." The plan was to pare the army from 70,000 men to 40,000, withdraw from exposed positions in eastern and northern Yemen, and tighten the hold on particular parts of Yemen: the Red Sea coastline; a northern boundary that takes in the well-fortified town of Hajja and San'a; and the border with the South Arabian Federation, which was to become independent in 1968. Nasser insisted that attacks on Najran, Qizan and other "bases of aggression" would continue, arguing that "these were originally Yemeni towns, which the Saudis usurped in 1930".

Assistant Secretary of State for the Near East and South Asia, flew in for talks with both Faisal and Nasser. In Alexandria, Nasser refused to pull out his troops, despite the risk of losing part or all of a new $150 million US food-distribution program, and another $100 million worth of industrial-development aid. Later that month, Alexei Kosygin counseled Nasser not to risk a stoppage of the U.S. Food for Peace program because Russia could not afford to pay the bill. The Russians were also willing to aid Nasser with arms and equipment in Yemen, but feared that a widening of the conflict to Saudi Arabia would lead to a "hot war" confrontation in the Middle East. Nasser was warned that "the Soviet Union would be displeased to see an attack on Saudi Arabia."

In October, Sallal's palace in San'a was shelled by a bazooka, and insurgents began targeting an Egyptian army camp outside the city and setting fire to Egyptian installations, killing a reported 70 Egyptian troops. Sallal arrested about 140 suspects, including Mohamed Ruwainy, the ex-Minister for Tribal Affairs, and Colonel Hadi Issa, former deputy chief of staff of the armed forces. Sallal accused Ruwainy and Issa of organizing a "subversive network seeking to plunge the country into terrorism and panic" and planning a campaign of assassination, financed by Saudi Arabia, Britain, Israel and the US. Ruwainy, Issa and five others were executed, while eight others received prison sentences ranging from five years to life. In February, 1967, Nasser vowed to "stay in Yemen 20 years if necessary", while Prince Hussein bin Ahmed said "We are prepared to fight for 50 years to keep Nasser out, just as we did the Ottoman Turks." Tunisia broke diplomatic relations with the republic, saying that the Sallal government no longer has power to govern the country. Sallal's chargé d'affaires in Czechoslovakia flew to Beirut and announced that he was on his way to offer his services to the royalists. Nasser said that "As the situation now stands, Arab summits are finished forever."

The first use of gas

The first use of gas

took place on June 8, 1963 against Kawma, a village of about 100 inhabitants in northern Yemen, killing about seven people and damaging the eyes and lungs of twenty-five others. This incident is considered to have been experimental, and the bombs were described as "home-made, amateurish and relatively ineffective". The Egyptian authorities suggested that the reported incidents were probably caused by napalm

, not gas. The Israeli Foreign Minister, Golda Meir

, suggested in an interview that Nasser would not hesitate to use gas against Israel as well. There were no reports of gas during 1964, and only a few were reported in 1965. The reports grew more frequent in late 1966. On December 11, 1966, fifteen gas bombs killed two people and injured thirty-five. On January 5, 1967, the biggest gas attack came against the village of Kitaf, causing 270 casualties, including 140 fatalities. The target may have been Prince Hassan bin Yahya, who had installed his headquarters nearby. The Egyptian government denied using poison gas, and alleged that Britain and the US were using the reports as psychological warfare against Egypt. On February 12, 1967, it said it would welcome a UN investigation. On March 1, U Thant

said he was "powerless" to deal with the matter.

On May 10, the twin villages of Gahar and Gadafa in Wadi Hirran, where Prince Mohamed bin Mohsin was in command, were gas bombed, killing at least seventy-five. The Red Cross was alerted and on June 2, it issued a statement in Geneva

expressing concern. The Institute of Forensic Medicine at the University of Berne

made a statement, based on a Red Cross report, that the gas was likely to have been halogenous derivatives - phosgene

, mustard gas, lewisite

, chloride

or cyanogen bromide

. The gas attacks stopped for three weeks after the Six-Day War

of June, but resumed on July, against all parts of royalist Yemen. Casualty estimates vary, and an assumption, considered conservative, is that the mustard and phosgene-filled aerial bombs caused approximately 1,500 fatalities and 1,500 injuries.

, Nasser recalled 15,000 of his troops from Yemen. Egypt imposed higher taxes on its middle and upper classes, raised workers' compulsory monthly savings by 50%, reduced overtime pay, cut the sugar ration by a third, and curtailed practically all major industrial programs. Only military expenditures were increased, by $140 million to an estimated $1 billion. Nasser also increased the price of beer, cigarettes, long-distance bus and railroad fares and admission to movies. Egypt was losing $5,000,000 a week in revenues from the closing of the Suez Canal, on the other side of which, the Israelis were sitting on the Sinai wells that had produced half of Egypt's oil supply. Egypt's hard-currency debt was now approaching $1.5 billion and its foreign-exchange reserves were down to $100 million.

As part of the Khartoum Resolution

of August, Egypt announced that it was ready to end the war in Yemen. Egyptian Foreign Minister, Mahmoud Riad

, proposed that Egypt and Saudi Arabia revive their Jeddah Agreement of 1965. Faisal expressed satisfaction with Nasser's offer, and al-Badr promised to send his troops to fight with Egypt against Israel, should Nasser live up to the Jeddah agreement Nasser and Faisal signed a treaty under which Nasser would pull out his 20,000 troops from Yemen, Faisal would stop sending arms to al-Badr, and three neutral Arab states would send in observers. Sallal accused Nasser of betrayal. Nasser unfroze more than $100 million worth of Saudi assets in Egypt, and Faisal denationalized two Egyptian-owned banks that he had taken over earlier that year. Saudi Arabia, Libya, and Kuwait agreed to provide Egypt with an annual subsidy of $266 million, out of which $154 million was to be paid by Saudi Arabia.

Sallal's popularity among his troops declined, and after two bazooka attacks on his home by disaffected soldiers, he took Egyptian guards. He ordered the execution of his security chief, Colonel Abdel Kader Khatari, after Khatari's police fired into a mob attacking an Egyptian command post in San'a, and had refused to recognize the committee of Arab leaders appointed at Khartoum to arrange peace terms. He also fired his entire Cabinet and formed a new one, installing three army men in key ministries, and took over the army ministry and the foreign ministry for himself. Meanwhile, Nasser announced the release of three republican leaders who had been held prisoner in Egypt for more than a year, and who were in favor of peace with the royalists. The three were Qadi Abdul Rahman Iryani, Ahmed Noman and General Amri. When Sallal met with Nasser in Cairo in early November, Nasser advised him to resign and go into exile. Sallal refused and went to Baghdad, hoping to get support from other Arab Socialists. As soon as he left Cairo, Nasser sent a cable to San'a, instructing his troops there not to block an attempt at a coup.

On November 5, Yemeni dissidents, supported by republican tribesmen called down to San'a, moved four tanks into the city's dusty squares, took over the Presidential Palace and announced over the government radio station that Sallal had been removed "from all positions of authority". The coup went unopposed. In Baghdad, Sallal asked for political asylum, saying "every revolutionary must anticipate obstacles and difficult situations". The Iraqi government offered him a home and a monthly grant of 500 dinars.

On November 5, Yemeni dissidents, supported by republican tribesmen called down to San'a, moved four tanks into the city's dusty squares, took over the Presidential Palace and announced over the government radio station that Sallal had been removed "from all positions of authority". The coup went unopposed. In Baghdad, Sallal asked for political asylum, saying "every revolutionary must anticipate obstacles and difficult situations". The Iraqi government offered him a home and a monthly grant of 500 dinars.

The new republican government was headed by Qadi Abdul Rahman Iryani, Ahmed Noman and Mohamed Ali Uthman. The Prime Minister was Mohsin al-Aini. Noman, however, remained in Beirut. He was doubtful of his colleagues reluctance to negotiate with the Hamidaddin family, preferring to expel it instead. On November 23, he resigned, and his place was taken by Hassan Amri. Prince Mohamed bin Hussein told the country's chiefs "We have money, and you will have your share if you join us. If not, we will go on without you". The chiefs agreed to mobilize their tribes. 6,000 royalist regulars and 50,000 armed tribesmen known as "the Fighting Rifles" surrounded San'a, captured its main airport and severed the highway to the port of Hodeida, a main route for Russian supplies. In a battle twelve miles east of the capital, 3,200 soldiers of both sides were killed, and an entire republican regiment reportedly deserted to the royalists. Bin Hussein gave them an ultimatum: "Surrender the city or be annihilated". Iryani went to Cairo for what the Egyptian official press agency called "a medical checkup". Foreign Minister Hassan Macky also left Yemen, leaving the government in charge of Amri. Amri declared a 6 p.m. curfew and ordered civilians to form militia units "to defend the republic". In Liberation Square, six suspected royalist infiltrators were publicly executed by a firing squad, and their bodies were later strung up on poles.

The republicans boasted a new air force, while the royalists claimed to have shot down a MiG-17 fighter with a Russian pilot. The US State Department said that this claim, as well as reports of twenty-four MiGs and forty Soviet technicians and pilots who had arrived in Yemen, were correct. In January, the republicans were defending San'a with about 2,000 regulars and tribesmen, plus armed townsmen and about ten tanks. They also had the backing of a score or more fighter aircraft piloted by Russians or Yemenis who passed a crash course in the Soviet Union. The city could still feed itself from the immediately surrounding countryside. Between 4,000 and 5,000 royalists suffered from republican air power, but had the advantage of high ground. However, they did not have enough ammunition, as the Saudis had halted arms deliveries after the Khartoum agreement and stopped financing the royalists after December.

, which had now become South Yemen. The royalists remained active until 1970. Talks between the two sides commenced while the fighting went on. The Foreign Minister, Hassan Makki, said "Better years of talk than a day of fighting". In 1970, Saudi Arabia recognized the Republic, and a ceasefire was effected. The Saudis gave the republic a grant of $20 million, which was later repeated intermittently, and Yemeni sheiks received Saudi stipends. By 1971, both Egypt and Saudi Arabia had disengaged from Yemen. South Yemen formed a connection with the Soviet Union. In September 1971, Amri resigned after murdering a photographer in San'a, and more power was given to Iryani, the effective President. By then, the royalists were integrated into the new republic, except for al-Badr's family, and a consultative Council was established. Clashes along the border between the states rose, and in 1972 a small war broke.

After the war, the tribes were better represented in the republican government. In 1969 sheiks were brought into the National Assembly and in 1971 into the Consultative Council. Under Iryani, the sheiks, particularly the ones who fought for the republicans and were close to the mediation attempt. By the end of the war there was a breach between the older and more liberal politicians and republican sheiks, and certain army sheiks and activists from South Yemen. In the summer of 1972 a border war broke and ended with a declaration from both North Yemen and South Yemen that they would reunite, but they did not. There were complaints in North Yemen about foreign influence by Saudi Arabia.

North Yemen

North Yemen is a term currently used to designate the Yemen Arab Republic , its predecessor, the Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen , and their predecessors that exercised sovereignty over the territory that is now the north-western part of the state of Yemen in southern Arabia.Neither state ever...

between royalists of the Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen

Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen

The Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen , sometimes spelled Mutawakelite Kingdom of Yemen, also known as the Kingdom of Yemen or as North Yemen, was a country from 1918 to 1962 in the northern part of what is now Yemen...

and factions of the Yemen Arab Republic

Yemen Arab Republic

The Yemen Arab Republic , also known as North Yemen or Yemen , was a country from 1962 to 1990 in the western part of what is now Yemen...

from 1962 to 1970. The war began with a coup d'état

Coup d'état

A coup d'état state, literally: strike/blow of state)—also known as a coup, putsch, and overthrow—is the sudden, extrajudicial deposition of a government, usually by a small group of the existing state establishment—typically the military—to replace the deposed government with another body; either...

carried out by the republican leader, Abdullah as-Sallal

Abdullah as-Sallal

Abdullah al-Sallal was the leader of the North Yemeni Revolution of 1962. He served as the first President of the Yemen Arab Republic from 27 September 1962 to 5 November 1967....

, which dethroned the newly crowned Imam al-Badr and declared Yemen a republic under his presidency. The Imam escaped to the Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia , commonly known in British English as Saudi Arabia and in Arabic as as-Sa‘ūdiyyah , is the largest state in Western Asia by land area, constituting the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula, and the second-largest in the Arab World...

n border and rallied popular support.

On the royalist side Jordan

Jordan

Jordan , officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan , Al-Mamlaka al-Urduniyya al-Hashemiyya) is a kingdom on the East Bank of the River Jordan. The country borders Saudi Arabia to the east and south-east, Iraq to the north-east, Syria to the north and the West Bank and Israel to the west, sharing...

and Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia , commonly known in British English as Saudi Arabia and in Arabic as as-Sa‘ūdiyyah , is the largest state in Western Asia by land area, constituting the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula, and the second-largest in the Arab World...

supplied military aid, and Britain

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

gave diplomatic support, while the republicans were supported by Egypt

Egypt

Egypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

and allegedly received warplanes from the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

.

Both foreign irregular and conventional forces were involved. The Egyptian President

President of Egypt

The President of the Arab Republic of Egypt is the head of state of Egypt.Under the Constitution of Egypt, the president is also the supreme commander of the armed forces and head of the executive branch of the Egyptian government....

, Gamal Abdel Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein was the second President of Egypt from 1956 until his death. A colonel in the Egyptian army, Nasser led the Egyptian Revolution of 1952 along with Muhammad Naguib, the first president, which overthrew the monarchy of Egypt and Sudan, and heralded a new period of...

, supported the republicans with as many as 70,000 Egyptian troops. Despite several military moves and peace conferences, the war sank into a stalemate. Egypt's commitment to the war is considered to have been detrimental to its performance in the Six-Day War

Six-Day War

The Six-Day War , also known as the June War, 1967 Arab-Israeli War, or Third Arab-Israeli War, was fought between June 5 and 10, 1967, by Israel and the neighboring states of Egypt , Jordan, and Syria...

of June 1967, after which Nasser found it increasingly difficult to maintain his army's involvement and began to pull his forces out of Yemen.

By 1970, King Faisal of Saudi Arabia

Faisal of Saudi Arabia

Faisal bin Abdul-Aziz Al Saud was King of Saudi Arabia from 1964 to 1975. As king, he is credited with rescuing the country's finances and implementing a policy of modernization and reform, while his main foreign policy themes were pan-Islamic Nationalism, anti-Communism, and pro-Palestinian...

recognized the republic after al- Badr refused to cede Najran, Jizan and Aseer to Saudi Arabia in return of continued aid, his famous response was "Their people are the most worthy of it" and sensing the willingness of the coup forces to cede those lands to the Saudis a truce was signed. Egyptian military historians refer to the war in Yemen as their Vietnam, and historian Michael Oren

Michael Oren

Michael B. Oren is an American-born Israeli historian and author and the Israeli ambassador to the United States...

(current Israeli Ambassador to the U.S) wrote that Egypt's military adventure in Yemen was so disastrous that "the imminent Vietnam War

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War was a Cold War-era military conflict that occurred in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. This war followed the First Indochina War and was fought between North Vietnam, supported by its communist allies, and the government of...

could easily have been dubbed America's Yemen."

Yemen

Imam Ahmad bin YahyaAhmad bin Yahya

Ahmad bin Yahya Hamidaddin was the penultimate king of the Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen from 1948 to 1962. His full name and title was H.M. al-Nasir-li-din Allah Ahmad bin al-Mutawakkil 'Ala Allah Yahya, Imam and Commander of the Faithful, and King of the Mutawakkilite Kingdom of the Yemen...

, who had inherited the Yemeni throne in 1948, was known as "Ahmad the devil" by his enemies. In 1955, Iraq

Iraq

Iraq ; officially the Republic of Iraq is a country in Western Asia spanning most of the northwestern end of the Zagros mountain range, the eastern part of the Syrian Desert and the northern part of the Arabian Desert....

-trained Colonel Ahmad Thalaya led a revolt against him. A group of soldiers under his command surrounded the royal palace of Al Urdhi at Taiz, a fortified stronghold where the Imam lived with his harem, the royal treasure, an arsenal of modern weapons, and a 150 strong palace-guard, and demanded Ahmad's abdication. Ahmad agreed, but demanded that his son, Imam al-Badr succeed him. Thalaya refused, preferring the King's half brother, the Emir Saif el Islam Abdullah, the 48-year-old Foreign Minister. While Abdullah began forming a new government, Ahmad opened the treasury coffers and secretly began buying off the besieging soldiers. After five days, the number of besiegers was reduced from 600 to 40. Ahmad then came out of the palace,wearing a devil's mask and wielding a long scimitar, terrifying the beseigers. He slashed two sentries dead before exchanging the sword for a sub-machine gun and leading his 150 guards onto the roof of the palace to begin a direct attack on the rebels. After 28 hours, 23 rebels and one palace guard were dead and Thalaya gave up. Abdullah was later reported executed, and Thalaya was publicly decapitated.

Damascus

Damascus , commonly known in Syria as Al Sham , and as the City of Jasmine , is the capital and the second largest city of Syria after Aleppo, both are part of the country's 14 governorates. In addition to being one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world, Damascus is a major...

to tell Nasser of Yemen's adherence to the UAR

UAR

UAR may refer to:* United Arab Republic, the state formed by the union of the republics of Egypt and Syria in 1958. It existed until Syria's secession in 1961, although Egypt continued to be known as the UAR until 1971....

. However, Ahmad was to keep his throne and his absolute power, and the arrangement constituted only a close alliance. In 1959 Ahmad went to Rome

Rome

Rome is the capital of Italy and the country's largest and most populated city and comune, with over 2.7 million residents in . The city is located in the central-western portion of the Italian Peninsula, on the Tiber River within the Lazio region of Italy.Rome's history spans two and a half...

to treat his arthritis, rheumatism, heart trouble and, reportedly, drug addiction. Fights between tribal chieftains erupted, and al-Badr unsuccessfully tried to buy off the dissidents by promising "reforms", including the appointment of a representative council, more army pay and promotions. Upon his return, Ahmad swore to crush the "agents of the Christians". He ordered the decapitation of one of his subjects and the amputation of the left hand and right foot of 15 others, in punishment for the murder of a high official the previous June. Al-Badr was only rebuked for his leniency, but the Yemeni radio stopped broadcasting army officers' speeches, and talks of reforms were silenced.

In June 1961, Ahmad was still recovering from an assassination attempt four months earlier, and moved out of the capital, Taiz, into the pleasure palace of Sala

Sala

- Geography :* Sala Municipality, Sweden - a municipality in Sweden* Sala, Sweden - a city in Sweden, seat of Sala Municipality* Sala municipality, Latvia - a municipality in Latvia* Sala, Latvia - a village in Latvia, an administrative centre of Sala municipality...

. Already Defense and Foreign Minister, Badr became acting Prime Minister and Interior Minister as well. Despite being Crown Prince, al-Badr still needed to be picked by the Ulema

Ulema

Ulama , also spelt ulema, refers to the educated class of Muslim legal scholars engaged in the several fields of Islamic studies. They are best known as the arbiters of shari‘a law...

in San'a. Al-Badr was not popular with the Ulema due to his association with Nasser, and the Ulema had refused Ahmad's request to ratify Badr's title. Imam Ahmad died on September 18, 1962, and was succeeded by his son, Imam al-Badr. One of al-Badr's first acts was to appoint Colonel Abdullah Sallal, a known socialist and Nasserist, as commander of the palace guard.

Egypt

Anthony Nutting

Sir Harold Anthony Nutting, 3rd Baronet was a British diplomat and Conservative Party politician.-Early and private life:...

's biography of Gamal Abdel-Nasser identifies several factors that led the Egyptian President to send expeditionary forces to Yemen. These included the unraveling of the union with Syria

Syria

Syria , officially the Syrian Arab Republic , is a country in Western Asia, bordering Lebanon and the Mediterranean Sea to the West, Turkey to the north, Iraq to the east, Jordan to the south, and Israel to the southwest....

in 1961, which dissolved his United Arab Republic

United Arab Republic

The United Arab Republic , often abbreviated as the U.A.R., was a sovereign union between Egypt and Syria. The union began in 1958 and existed until 1961, when Syria seceded from the union. Egypt continued to be known officially as the "United Arab Republic" until 1971. The President was Gamal...

(UAR), damaging his prestige. A quick decisive victory in Yemen could help him recover leadership of the Arab world

Arab world

The Arab world refers to Arabic-speaking states, territories and populations in North Africa, Western Asia and elsewhere.The standard definition of the Arab world comprises the 22 states and territories of the Arab League stretching from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Arabian Sea in the...

. Nasser also had his reputation as an anti-colonial force, setting his sights on ridding South Yemen, and its strategic port city of Aden

Aden

Aden is a seaport city in Yemen, located by the eastern approach to the Red Sea , some 170 kilometres east of Bab-el-Mandeb. Its population is approximately 800,000. Aden's ancient, natural harbour lies in the crater of an extinct volcano which now forms a peninsula, joined to the mainland by a...

, of British