History of Rome (Mommsen)

Encyclopedia

The History of Rome is a multi-volume history of ancient Rome

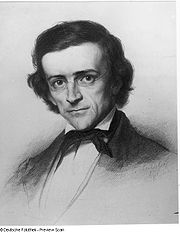

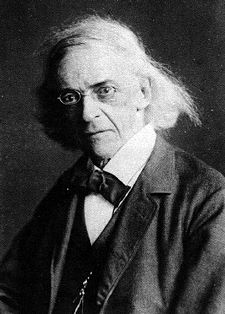

written by Theodor Mommsen

(1817–1903). Originally published by Reimer & Hirsel, Leipzig

, as three volumes during 1854-1856, the work dealt with the Roman Republic

. A subsequent book was issued which concerned the provinces of the Roman Empire

. Recently published was a further book on the Empire, reconstructed from lecture notes. The initial three volumes won widespread acclaim upon publication; indeed, "The Roman History made Mommsen famous in a day." Still read and qualifiedly cited, it is the prolific Mommsen's most well-known work. Eventually it would earn him a Nobel Prize

.

Writing the History followed Mommsen's earlier achievements in the study of ancient Rome. He had not himself designed to write a history, but the opportunity presented itself in 1850 while at the University of Leipzig

Writing the History followed Mommsen's earlier achievements in the study of ancient Rome. He had not himself designed to write a history, but the opportunity presented itself in 1850 while at the University of Leipzig

where Mommsen was a thirty-two-year-old special Professor of Law. "Invited to give a public lecture while at Leipzig

, I delivered an address on the Gracchi

. Reimer and Hirzel, the publishers, were present, and two days later they asked me to write a Roman History for their series." Having been dismissed from the University for revolutionary activities, Mommsen would accept the publishing proposal "partly for my livelihood, and partly because the work greatly appeals to me."

The publishers specified that the work focus on events and circumstances, and avoid discussing the scholarly process. While they certainly wanted a well-respected academic work to fit their acclaimed series on history, Karl Reimer and Solomon Hirzel were also seeking one with literary merit that would be accessible and appeal to the educated public. As a scholar Mommsen was an active party in recent advances made in ancient Roman studies. Yet Mommsen also had some experience as a journalist. He might well manage to become a popular academic author. "It is high time for such a work", Mommsen wrote to an associate in Roman studies, "it is more than ever necessary to present to a wider audience the results of our researches."

from its inception to the emperor Diocletian

(284-305). The first three volumes, which covered the origin of Rome through the fall of the Republic, ending with the reforms of Julius Caesar, were published in 1854, 1855, and 1856, as the Römische Geschichte.

These three volumes did indeed become popular, very popular. "Their success was immediate." Here "a professional scholar" presented his readers with a prose that was of "such vigor and life, such grasp of detail combined with such vision, such self-confident mastery of a vast field of learning." Especially in Mommsen's third volume, as the narrative told of how the political crisis in the Roman Republic came to its final climax, "he wrote with a fire of imagination and emotion almost unknown in a professional history. Here was scientific learning with the stylistic vigor of a novel."

These first three volumes of the Römische Geschichte retained their popularity in Germany, with eight editions being published in Mommsen's lifetime. Following his death in 1903, an additional eight German editions have issued.

A planned fourth volume covering Roman history under the Empire

A planned fourth volume covering Roman history under the Empire

was delayed pending Mommsen's completion of a then 15-volume work on Roman inscriptions

, which required his services as researcher, writer, and editor, occupying Mommsen for many years. After repeated delays the projected fourth volume was eventually abandoned, or at least not completed; an early manuscript may have been lost in a fire.

In 1885, however, Mommsen had ready another work on ancient Rome, later translated into English as The Provinces of the Roman Empire. In Germany it was published as the fifth volume of his Römische Geschichte. In thirteen chapters it describes the different imperial provinces, each as a stand-alone subject. Here there was no running narration of major Roman political events, often dramatic, as was the case in Mommsen's popular chronological telling of his earlier volumes.

In 1992, a reconstruction of Mommsen's missing "fourth volume" on the Empire was issued. Its sources were lesson notes taken by two related students, Sebastian Hensel (father) and Paul Hensel (son), of lectures delivered by Prof. Mommsen during 1882-1886 regarding his courses on imperial Roman History, given at the University of Berlin. These student notes were 'discovered' in 1980 at a used bookshop in Nuremberg by Alexander Demandt

, then edited by Barbara Demandt and Alexander Demandt; the resulting German text was published in 1992. The Hensel family was distinguished, the son becoming a philosophy professor, the father writing a family history (1879) with regard to his mother's brother the composer Felix Mendelssohn

, and the paternal grandfather being a Prussian court painter.

. The first three German volumes (which contained five 'books') were published during 1862 to 1866 by R. Bentley & Son, London. Over several decades Prof. Dickson prepared further English editions of this translation, keeping pace with Mommsen's revisions in German. All told, close to a hundred editions and reprints of the English translation have been published.

In 1958 selections from the final two 'books' of the three-volume History were prepared by Dero A. Saunders

and John H. Collins

for a shorter English version. The content was chosen to highlight Mommsen's telling of the social-political struggles over several generations leading to the fall of the Republic

. Provided with new annotations and a revised translation, the book presents an abridgment revealing the historical chronology. With rigor Mommsen is shown narrating the grave political drama and illuminating its implications; the book closes with his lengthy description of the new order of government adumbrated by Julius Caesar.

With regard to Mommsen's 1885 "fifth volume" on the Roman provinces, Prof. Dr. Dickson immediate began to supervise its translation. In 1886 it appeared as The Provinces of the Roman Empire. From Caesar to Diocletian.

Mommsen's missing fourth volume was reconstructed from student notes and published in 1992 under the title Römische Kaisergeschichte. It was soon translated into English by Clare Krojzl as A History of Rome under the Emperors.

The broad strokes of Mommsen's long, sometimes intense narrative of the Roman Republic were summarized at the 1902 award of the Nobel Prize in a speech given by the secretary of the Swedish Academy

. At the beginning, the strength of Rome derived from the health of its families, e.g., a Roman's obedience

to the state was associated with obedience of son to father. From here Mommsen skillfully unrolls the huge canvas of Rome's long development from rural town to world capital. An early source of stability and effectiveness was the stubbornly preserved constitution; e.g., the reformed Senate

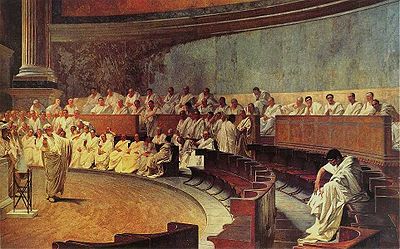

composed of patricians and plebians generally handled public affairs of the city-state in an honorable manner.

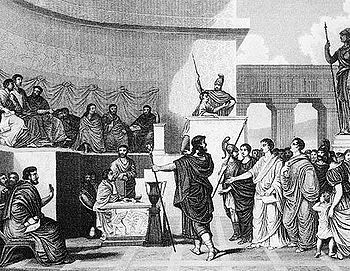

Yet the great expansion of Rome and the consequent transformations worked to subvert the ancient order. Gradually, older institutions grew incapable of effectively meeting new and challenging circumstances, of performing the required civic tasks. The purported sovereignty of the comitia (people's assembly) became only a fiction, which might be exploited by demagogues for their own purposes. In the Senate, the old aristocratic

Yet the great expansion of Rome and the consequent transformations worked to subvert the ancient order. Gradually, older institutions grew incapable of effectively meeting new and challenging circumstances, of performing the required civic tasks. The purported sovereignty of the comitia (people's assembly) became only a fiction, which might be exploited by demagogues for their own purposes. In the Senate, the old aristocratic

oligarchy

began to become corrupted by the enormous wealth derived from military conquest and its aftermath; it no longer served well its functional purpose, it failed to meet new demands placed on Rome, and its members would selfishly seek to preserve inherited prerogatives against legitimate challenge and transition. A frequently unpatriotic capitalism abused its power in politics and by irresponsible speculation. The free peasantry became squeezed by the competing demands of powerful interests; accordingly its numbers began to dwindle, which eventually led to a restructuring of Army recruitment, and later resulted in disastrous consequences for the entire commonwealth.

Moreover the annual change of consul

Moreover the annual change of consul

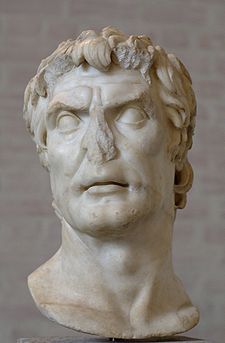

s (the two Roman chief executives) began to adversely impact the consistent management of its armed forces, and to weaken their effectiveness, especially in the era following the Punic Wars. Eventually it led to the prolongation of military commands in the field; hence, Roman army generals became increasingly independent, and they led soldiers personally loyal to them. These military leaders began to acquire the ability to rule better than the ineffective civil institutions. In short, the civil power's political capabilities were not commensurate with the actual needs of the Roman state. As Rome's strength and reach increased, the political situation developed in which an absolute command structure imposed by military leaders at the top might, in the long run, in many cases be more successful and cause less chaos and hardship to the citizenry

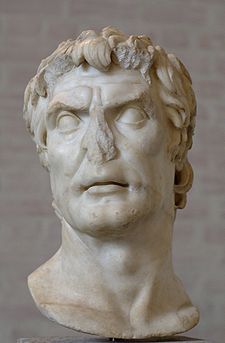

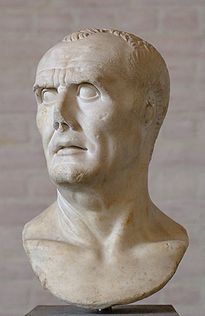

than the corrupt and incompetent rule by the oligarchy of quarreling old families who de facto controlled the government. Such was his purpose when the conservative Optimate, the noble and Roman general Sulla (138-78), seized state power by military force; yet he sought without permanent success to restore the Senate nobility

to its former power.

Political instability soon returned, social unrest being the disagreeable norm. The conservative renovation of the Republic's institutions was abandoned and taken apart. Eventually the decisive civil war victory of the incomparable Julius Caesar

(100-44), followed by his executive mastery and public-minded reforms, appeared as the necessary and welcome step forward toward resolution of the sorry and bloody debacle at Rome. This, in the dramatic narrative of Theodore Mommsen.

Mommsen's penultimate chapter provides an outline of the 'nation building' program begun by Caesar following his victory. Institutions were reformed, the many regions ruled by Rome became more unified in design, as if prepared for a future Empire which would endure for centuries; this, during Caesar's last five and a half years alive. His work at statecraft included the following: the slow pacification of party strife, nonetheless with republican opposition latent and episodically expressed; his assumption of the title Imperator

Mommsen's penultimate chapter provides an outline of the 'nation building' program begun by Caesar following his victory. Institutions were reformed, the many regions ruled by Rome became more unified in design, as if prepared for a future Empire which would endure for centuries; this, during Caesar's last five and a half years alive. His work at statecraft included the following: the slow pacification of party strife, nonetheless with republican opposition latent and episodically expressed; his assumption of the title Imperator

(refusing the crown, yet continuing since 49 as dictator

), with reversion of the Senate to an advisory council, and the popular comitia as a compliant legislature, although law might be made by his edicts alone; his assumption of authority over tax and treasury, over provincial governors, and over the capital; supreme jurisdiction

(trial and appellate) over the continuing republican legal system, with the judex being selected among senators or equites, yet criminal courts remained corrupted by factional infighting; supreme command over the decayed Roman army

, which was reorganized and which remained under civilian control; reform of government finance, of bugeting re income and expense, and of corn distribution; cultivation of civil peace in Rome by control of criminal "clubs", by new city police, and by public building projects. Impossible problems: widespread slavery, disappearance of family farms, extravagance and immorality of the wealthy, dire poverty, speculation, debt; Caesar's reforms: favoring families, against absentees, restricting luxuries

, debt relief (but not cancellation as demanded by populares), personal bankruptcy

for unpayable debt replacing enslavement by creditors, usury

laws, road building, distribution of public agricultural lands in a moderated Gracchan

fashion, and new municipal law. Mommsen writes, "[W]e may well conclude that Caesar with his reforms came as near to the measure of what was possible as it was given to a statesman and a Roman to come."

Regarding the Roman provinces, former misrule and financial plundering is described, committed by Roman government agents and Roman merchants; Caesar's reforms replaced the quasi-independent Roman governors with those selected by the Imperator and closely supervised, with reduction in taxes; provincial oppression by private concerns was found more difficult to arrest. Abatement of the prior popular notion of the provinces as "country estates" to be worked or exploited for Rome's benefit. Favors granted Jews; Latin colonies continue. Cultural joining of Latins and Hellenes; "Italy was converted from the mistress of subject peoples into the mother of the renovated Italo-Hellenic nation." Census of the Mediterranean population under Rome taken; popular religion left free of additional state norms. Continuing development of the Praetor's Edict, and plans for a codification of law. Roman coinage, weights and measures reformed; creation of the Julian Calendar

Regarding the Roman provinces, former misrule and financial plundering is described, committed by Roman government agents and Roman merchants; Caesar's reforms replaced the quasi-independent Roman governors with those selected by the Imperator and closely supervised, with reduction in taxes; provincial oppression by private concerns was found more difficult to arrest. Abatement of the prior popular notion of the provinces as "country estates" to be worked or exploited for Rome's benefit. Favors granted Jews; Latin colonies continue. Cultural joining of Latins and Hellenes; "Italy was converted from the mistress of subject peoples into the mother of the renovated Italo-Hellenic nation." Census of the Mediterranean population under Rome taken; popular religion left free of additional state norms. Continuing development of the Praetor's Edict, and plans for a codification of law. Roman coinage, weights and measures reformed; creation of the Julian Calendar

. "The rapidity and self-precision with which the plan was executed prove that it had been long meditated thoroughly and all its parts settled in detail", Mommsen comments. "[T]his was probably the meaning of the words which were heard to fall from him--that he had 'lived enough'."

The exceptions to the straight-forward chronology are the periodic digressions in his narrative, where Mommsen inserts separate chapters, each devoted to one or more of a range of particular subjects, for example:

The exceptions to the straight-forward chronology are the periodic digressions in his narrative, where Mommsen inserts separate chapters, each devoted to one or more of a range of particular subjects, for example:

Mommsen's expertise in Roman studies was acknowledged by his peers as being both wide and deep, e.g., his direction of the ancient Latin inscriptions

Mommsen's expertise in Roman studies was acknowledged by his peers as being both wide and deep, e.g., his direction of the ancient Latin inscriptions

project, his work on ancient dialects of Italy, the journal he began devoted to Roman coinage, his multivolume Staatsrecht on the long history of constitutional law

at Rome, his volumes on Roman criminal law, the Strafrecht. His bibliography lists 1500 works.

, Germany, Britain, the Danube, Greece, Asia Minor

, the Euphrates and Parthia

, Syria and the Nabataeans

, Judaea, Egypt, and the Africa province

s. Generally, each chapter describes the economic geography of a region and its people, before addressing its Imperial regime. Regarding the North, military administration is often stressed; while for the East, the culture and history.

A quarter of the way into his short "Introduction" to the Provinces Mommsen comments on the decline of Rome, the capital city: "The Roman state of this epoch resembles a mighty tree, the main stem of which, in the course of its decay, is surrounded by vigorous offshoots pushing their way upward." These shoots being the provinces he here describes.

Mommsen's missing fourth volume, as reconstructed by Barbara Demandt and Alexander Demandt

Mommsen's missing fourth volume, as reconstructed by Barbara Demandt and Alexander Demandt

from lecture notes, was published as Römische Kaisergeschichte in 1992. Thus appearing many years after third volume (1856), and the fifth (1885). It contains three sections of roughly equal size.

The first section is arranged chronologically by emperor: Augustus (44 BC-AD 14); Tiberius (14-37); Gaius Caligula (37-41); Claudius (41-54); Nero (54-68); The Year of Four Emperors (68-69); Vespasian (69-79).

The chapters of the second section are entitled: General Introduction; Domestic Politics I; Wars in the West; Wars on the Danube; Wars in the East; Domestic Politics II.

The third section: General Introduction; Government and Society; A History of Events [this the longest subsection, arranged by emperors]: Diocletian (284-305); Constantine (306-337); The sons of Constantine (337-361); Julian and Jovian (355-364); Valentinian and Valens (364-378); From Theodosius to Alaric (379-410).

This rescued work contains a great wealth of material, in which one follows in the footsteps of a master historian. Yet, perhaps because of its nature as reconstructed student lecture notes, it more often lacks the fine points of literary composition and style, and of course the narrative drive of the original three volumes. Nonetheless it is well to remember that the students involved here in taking the lecture notes were themselves quite accomplished people, and one listener and recorder was already a mature father.

to shed new light on the old writings. Niebuhr's Roman History was highly praised.

Yet Mommsen outdid Niebuhr. Mommsen sought to create a new category of material evidence on which to built an account of Roman history, i.e., in addition to the literature and art. Of chief importance were the many surviving Latin inscriptions, often on stone or metal. Also included were the Roman ruins, and the various Roman artefacts ranging from pottery and textiles, to tools and weapons. Mommsen encouraged the systematic investigation of these new sources, combined with on-going developments in philology

Yet Mommsen outdid Niebuhr. Mommsen sought to create a new category of material evidence on which to built an account of Roman history, i.e., in addition to the literature and art. Of chief importance were the many surviving Latin inscriptions, often on stone or metal. Also included were the Roman ruins, and the various Roman artefacts ranging from pottery and textiles, to tools and weapons. Mommsen encouraged the systematic investigation of these new sources, combined with on-going developments in philology

and legal history

. Much on-going work was furthering this program: inscriptions were being gathered and authenticated, site work performed at the ruins, and technical examination make of the objects. From a coordinated synthesis of these miscellaneous studies, historical models might be constructed. Such modeling would provide historians with an objective framework independent of the ancient texts, by which to determine their reliability. Information found in the surviving literature then could be for the first time properly scrutinized for its truth value and accordingly appraised.

The Mommsen's work won immediate, widespread acclaim, but the praise it drew was not unanimous. "While the public welcomed the book with delight and scholars testified to its impeccable erudition, some specialists were annoyed at finding old hypotheses rejected... ." Mommsen omits much of the foundation legends

and other tales of early Rome, because he could find no independent evidence to verify them. He thus ignored a scholarly field that was seeking a harmonized view using merely ancient writers. Instead Mommsen's Römische Geschichte presented only events from surviving literature that could be somehow checked against other knownledge gained elsewhere, e.g., from inscriptions, philology, or archaeology

.

Work continues, of course, in the trans-generational endeavor of moderns to understand what can legitimately be understood from what is left of the ancient world, including the works of the ancient historians. To be self aware of how the approach ancient evidence, of course, is included in the challenge.

There were academics who disapproved of its tone. "It was indeed the work of a politician and journalist as well as of a scholar." Before writing the History, Mommsen had participated in events during the unrest of 1848 in Germany

, a year of European-wide revolts; he had worked editing a periodical which involved politics. Later Mommsen became a member of the Prussian legislature and eventually of the Reichstag

. Mommsen's transparent comparison of ancient to modern politics is said to distort, his terse style to be journalistic, i.e., not up to the standard to be achieved by the professional academic.

About his modernist tone, Mommsen wrote: "I wanted to bring down the ancients from the fantastic pedestal on which they appear into the real world. That is why the consul

had to become the burgomaster

." As to his partisanship, Mommsen replied: "Those who have lived through historical events... see that history is neither written nor made without love and hate." To the challenge that he favored the political career of Julius Caesar

, Mommsen referred to the corruption and disfunction of the tottering Republic: "When a Government cannot govern, it ceases to be legitimate, and he who has the power to overthrow it has also the right." He further clarified, stating the Caesar's role must be considered as the lesser of two evils. As an organism is better than a machine "so is every imperfect constitution which gives room for the free self-determination of a majority of citizens infinitely [better] than the most humane and wonderful absolutism; for one is living, and the other is dead." Thus, the Empire would only hold together a tree without sap.

, by means of family connection, marriage alliance, wealth, or corruption. Such "men may be said to have formed a 'party' in the sense that they had at least a common outlook--stubborn conservatism." They contended vainly among themselves for state 'honors' and personal greed, "forming cliques and intrigues in what amounted to a private game". Such Senate 'misrule' subverted Rome, causing prolonged wrongs and injustice that "aroused sporadic and sometimes massive and desperate opposition. But the opposition was never organized into a party. ... [T]here was no clear political tradition running from the Gracchi

through Marius

to Caesar

."

The classicist Lily Ross Taylor

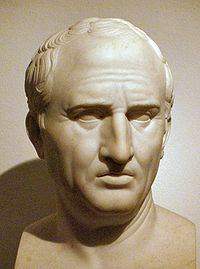

addresses this issue, as follows. Cicero

, to refer to these two rival political groups, continually used the Latin word partes [English "parties"]. Cicero (106-43) was a key figure in Roman politics who wrote volumes about it. In distinguishing the two groups, he employed the Latin terms optimates for proponents of the Senate nobility and populares for elite proponents of the popular demos

or commoners. She points to the Roman historians Sallust

(86-34) and Livy

(59 BC-AD 17) for partial confirmation, as well as to later writers Plutarch

(c.46-120), Appian

(c.95-c.165), and Dio (c.155-c.235), and later still Machiavelli (1469–1527).

These rival political groups, Prof. Taylor states, were quite amorphous, as Mommsen well knew. In fact when Mommsen wrote his Romische Geschichte (1854–1856) political parties in Europe and America were also generally amorphous, being comparatively unorganized and unfocused, absent member alligiance and often lacking programs. Yet in the 20th century modern parties

grew better organized with enduring policies, so that their comparison with ancient Rome has become more and more tenuous. She describes Mommsen:

As Prof. Taylor continues, since Mommsen's wrote modern party 'tickets' and party 'lines' have grown more disciplined, and "the meaning of party had undergone a radical change. Thus the terms 'optimate' and 'popular

' party are misleading to the modern reader. [¶] Lately there has been protest against the attribution of parties to Rome. The protest has gone too far." That is, the above-stated divisions were strong and constellated politics during the last century of the Roman Republic

.

published his What is History?

, which became well known. Therein Carr conjectured that the very nature of writing history

will cause historians as a whole to reveal themselves to their readers as 'prisoners' subject to the context of their own age and culture. As a consequence, one may add, every generation feels the need to rewrite history so that it better fits their own situation, their point of view. To illustrate his point here, Carr selected as exemplars a number of well-regarded historians, among them being Theodore Mommsen.

Accordingly Carr informs us that Mommsen's multivolume work Römische Geschichte (Leipzig 1854-1856) may tell the perceptive modern historian much about mid-19th century Germany, while it is presenting an account of ancient Rome. A major recent event in Germany was the failure of the 1848-1849 Revolution

Accordingly Carr informs us that Mommsen's multivolume work Römische Geschichte (Leipzig 1854-1856) may tell the perceptive modern historian much about mid-19th century Germany, while it is presenting an account of ancient Rome. A major recent event in Germany was the failure of the 1848-1849 Revolution

, while in Mommsen's Roman History his narration of the Republic

draws to a close with the revolutionary emergence of a strong state executive in the figure of Julius Caesar

. Carr conjectures as follows.

Far from protesting or denying such an observation, Mommsen himself readily admitted it. He added, "I wanted to bring down the ancient from their fantastic pedestal on which they appear in the real world. That is why the consul had to become the burgomaster. Perhaps I have overdone it; but my intention was sound enough."

Alongside Carr on Mommsen, Carr likewise approaches George Grote

's History of Greece (1846–1856) and states that it must also reveal that period's England as well as ancient Greece. Thus about Grote's book Carr conjectures.

"I should not think it an outrageous paradox", writes Carr, "if someone were to say that Grote's History of Greece has quite as much to tell us about the thought of the English philosophical radicals

in the 1840's as about Athenian democracy

in the fifth century B.C." Prof. Carr credits the philosopher R. G. Collingwood as being his inspiration for this line of thinking.

Robin Collingwood, an early 20th century Oxford professor, worked at building a philosophy of history, wherein history would remain a sovereign discipline. In pursuing this project he studied extensively the Italian philosopher and historian Benedetto Croce

(1866–1952). Collingwood wrote on Croce, here in his 1921 essay.

In summary, Edward Carr here presents his interesting developments regarding the theories proposed by Benedetto Croce and later taken up by Robin Collingwood. In doing so Carr does not allege mistaken views or fault specific to Mommsen, or to any of the other historians he mentions. Rather any such errors and faults would be general to all history writing. As Collingwood states, "The only safe way of avoiding error is to give up looking for the truth." Nonetheless, this line of thought, and these examples and illustrations of how Mommsen's Germany might color his history of ancient Rome, are illuminating concerning both the process and the result.

Caesar sprung from the heart of this old nobility, yet he was born into a family which had already allied itself with the populares, i.e., those who favored constitutional change. Hence Caesar's career was associated with the struggle for a new order and, failing opportunity along peaceful avenues, he emerged as a military leader whose triumph at arms worked to advance political change. Yet both parties in this long struggle had checkered histories of violence and corruption. Mommsen, too, recognized and reported "Caesar the rake, Caesar the conspriator, and Caesar the groundbreaker for later centuries of absolutism."

Caesar sprung from the heart of this old nobility, yet he was born into a family which had already allied itself with the populares, i.e., those who favored constitutional change. Hence Caesar's career was associated with the struggle for a new order and, failing opportunity along peaceful avenues, he emerged as a military leader whose triumph at arms worked to advance political change. Yet both parties in this long struggle had checkered histories of violence and corruption. Mommsen, too, recognized and reported "Caesar the rake, Caesar the conspriator, and Caesar the groundbreaker for later centuries of absolutism."

Some moderns follow the optimate view that it was a nefarious role that Caesar played in the fall of the Republic

, whose ruling array of institutions had not yet outlived their usefulness. To the contrary, the Republic's fall ushered in the oppressive Empire

whose 'divine' rulers held absolute power. Julius Caesar as villain was an opinion shared, of course, by his knife-wielding assassins, most of whom were also nobility. Shared also without shame by that epitome of classical Roman politics and letters, Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43). For some observers, following Caesar's assassination Cicero saved his rather erratic career in politics by his high-profile stand in favor of the Republic. Also strong among Caesar's opponents was Marcus Porcius Cato Uticensis (95-46), who had long led the opimates, supporters of the republican aristocracy, against the populares and in particular against Julius Caesar. During the Imperial era the stoic

Cato became the symbol of lost republican virtue.

Nonetheless, even deadly foes could see the bright genius of Caesar; indeed, many conspitators were his beneficiaries. "Brutus

Nonetheless, even deadly foes could see the bright genius of Caesar; indeed, many conspitators were his beneficiaries. "Brutus

, Cassius

and the others who, like Cicero, attached themselves to the conspiracy acted less out of enmity to Caesar than out of a desire to destroy his dominatio." Too, the conspiracy failed to restore the Republic. An aristocrat's libertas meant very little to the population: the people, the armies, or even the equestrians; his assassins "failed to grasp the real pulse of the respublica."

Moderns may be able to see both sides of the issue, however, as an historian might. Indeed, there exists a great difference in context between, say, an American, and a German historian of the 1850s, where during 1848

citizens had made a rather spontaneous, incoherent effort to move German politics toward a free and unified country: it was crushed by the nobility.

The philosopher Robin Collingwood (1889–1943) developed a nuanced view of history in which each person explores the past in order to create his or her own true understanding of that person's unique cultural inheritance. Although objectivity remains crucial to the process, each will naturally draw out their own inner truth from the universe of human truth. This fits the stark limitations on each individual's ability to know all sides of history. To a mitigated extent these constraints work also on the historian. Collingwood writes:

A modern historian of ancient Rome echoes the rough, current consensus of academics about this great and controversial figure, as he concludes his well-regarded biography of Julius Caesar: "When they killed him his assassins did not realise that they had eliminated the best and most far-sighted mind of their class."

As to the matter of why "Mommsen failed to continue his history beyond the fall of the republic", Carr wrote: "During his active career, the problem of what happened once the strong man had taken over was not yet actual. Nothing inspired Mommsen to project this problem back on to the Roman scene; and the history of the empire remained unwritten."

While not following Niebuhr's 'divination', Mommsen's manner goes to question of whether one may use discrete and controlled 'intersticial projection', safeguarded by monitoring the results closely after the fact. Does its use necessarily sacrifice claims to 'objectivity'? Termed intuition based on scholarship.

of ancient Roman history:

One encyclopaedic reference summarizes: "Equally great as antiquary, jurist, political and social historian, Mommsen [had] no rivals. He combined the power of minute investigation with a singular faculty for bold generalization... ." About the History of Rome the universal historian Arnold J. Toynbee

writes, "Mommsen wrote a great book, which certainly will always be reckoned among the masterpieces of Western historical literature." G. P. Gooch gives us these comments evaluating Mommsen's History: "Its sureness of touch, its many-sided knowledge, its throbbing vitality and the Venetian colouring of its portraits left an ineffaceable impression on every reader." "It was a work of genius and passion, the creation of a young man, and is as fresh and vital to-day as when it was written."

The award came nearly fifty years after the first appearance of the work. The award also came during the last year of the author's life (1817–1903). It is the only time thus far that the Nobel Prize for Literature has been presented to a historian

per se. Yet the literary Nobel has since been awarded to a philosopher (1950) with mention of an "intellectual history", and to a war-time leader (1953) for speeches and writings, including a "current events history", plus a Nobel Memorial Prize has been awarded for two "economic histories" (1993). Nonetheless Mommsen's multi-volume History of Rome remains in a singular Nobel class.

The 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica

, a well-regarded reference yet nonetheless "a source unsparingly critical", summarizes: "Equally great as antiquary, jurist, political and social historian, Mommsen lived to see the time when among students of Roman history he had pupils, followers, critics, but no rivals. He combined the power of minute investigation with a singular faculty for bold generalization and the capacity for tracing out the effects of thought on political and social life."

The British historian G. P. Gooch, writing in 1913, eleven years after Mommsen's Nobel prize, gives us this evaluation of his Römisches Geschichte: "Its sureness of touch, its many-sided knowledge, its throbbing vitality and the Venetian colouring of its portraits left an ineffaceable impression on every reader." "It was a work of genius and passion, the creation of a young man, and is as fresh and vital to-day as when it was written." About the History of Rome another British historian Arnold J. Toynbee

in 1934 wrote, at the beginning of his own 12-volume universal history, "Mommsen wrote a great book, [Römisches Geschichte], which certainly will always be reckoned among the masterpieces of Western historical literature."

Ancient Rome

Ancient Rome was a thriving civilization that grew on the Italian Peninsula as early as the 8th century BC. Located along the Mediterranean Sea and centered on the city of Rome, it expanded to one of the largest empires in the ancient world....

written by Theodor Mommsen

Theodor Mommsen

Christian Matthias Theodor Mommsen was a German classical scholar, historian, jurist, journalist, politician, archaeologist, and writer generally regarded as the greatest classicist of the 19th century. His work regarding Roman history is still of fundamental importance for contemporary research...

(1817–1903). Originally published by Reimer & Hirsel, Leipzig

Leipzig

Leipzig Leipzig has always been a trade city, situated during the time of the Holy Roman Empire at the intersection of the Via Regia and Via Imperii, two important trade routes. At one time, Leipzig was one of the major European centres of learning and culture in fields such as music and publishing...

, as three volumes during 1854-1856, the work dealt with the Roman Republic

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic was the period of the ancient Roman civilization where the government operated as a republic. It began with the overthrow of the Roman monarchy, traditionally dated around 508 BC, and its replacement by a government headed by two consuls, elected annually by the citizens and...

. A subsequent book was issued which concerned the provinces of the Roman Empire

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

. Recently published was a further book on the Empire, reconstructed from lecture notes. The initial three volumes won widespread acclaim upon publication; indeed, "The Roman History made Mommsen famous in a day." Still read and qualifiedly cited, it is the prolific Mommsen's most well-known work. Eventually it would earn him a Nobel Prize

Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes are annual international awards bestowed by Scandinavian committees in recognition of cultural and scientific advances. The will of the Swedish chemist Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite, established the prizes in 1895...

.

Genesis

University of Leipzig

The University of Leipzig , located in Leipzig in the Free State of Saxony, Germany, is one of the oldest universities in the world and the second-oldest university in Germany...

where Mommsen was a thirty-two-year-old special Professor of Law. "Invited to give a public lecture while at Leipzig

Leipzig

Leipzig Leipzig has always been a trade city, situated during the time of the Holy Roman Empire at the intersection of the Via Regia and Via Imperii, two important trade routes. At one time, Leipzig was one of the major European centres of learning and culture in fields such as music and publishing...

, I delivered an address on the Gracchi

Gracchi

The Gracchi brothers, Tiberius and Gaius, were Roman Plebian nobiles who both served as tribunes in 2nd century BC. They attempted to pass land reform legislation that would redistribute the major patrician landholdings among the plebeians. For this legislation and their membership in the...

. Reimer and Hirzel, the publishers, were present, and two days later they asked me to write a Roman History for their series." Having been dismissed from the University for revolutionary activities, Mommsen would accept the publishing proposal "partly for my livelihood, and partly because the work greatly appeals to me."

The publishers specified that the work focus on events and circumstances, and avoid discussing the scholarly process. While they certainly wanted a well-respected academic work to fit their acclaimed series on history, Karl Reimer and Solomon Hirzel were also seeking one with literary merit that would be accessible and appeal to the educated public. As a scholar Mommsen was an active party in recent advances made in ancient Roman studies. Yet Mommsen also had some experience as a journalist. He might well manage to become a popular academic author. "It is high time for such a work", Mommsen wrote to an associate in Roman studies, "it is more than ever necessary to present to a wider audience the results of our researches."

Original

Originally the History was conceived as a five volume work, spanning Roman historyHistory of Rome (disambiguation)

The History of Rome may concern: I. celebrated Histories of ancient Rome; or, II. the history of Rome proper; or, III. Successors to the Roman Empire. The second of these, II...

from its inception to the emperor Diocletian

Diocletian

Diocletian |latinized]] upon his accession to Diocletian . c. 22 December 244 – 3 December 311), was a Roman Emperor from 284 to 305....

(284-305). The first three volumes, which covered the origin of Rome through the fall of the Republic, ending with the reforms of Julius Caesar, were published in 1854, 1855, and 1856, as the Römische Geschichte.

These three volumes did indeed become popular, very popular. "Their success was immediate." Here "a professional scholar" presented his readers with a prose that was of "such vigor and life, such grasp of detail combined with such vision, such self-confident mastery of a vast field of learning." Especially in Mommsen's third volume, as the narrative told of how the political crisis in the Roman Republic came to its final climax, "he wrote with a fire of imagination and emotion almost unknown in a professional history. Here was scientific learning with the stylistic vigor of a novel."

These first three volumes of the Römische Geschichte retained their popularity in Germany, with eight editions being published in Mommsen's lifetime. Following his death in 1903, an additional eight German editions have issued.

Later volumes

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

was delayed pending Mommsen's completion of a then 15-volume work on Roman inscriptions

Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum

The Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum is a comprehensive collection of ancient Latin inscriptions. It forms an authoritative source for documenting the surviving epigraphy of classical antiquity. Public and personal inscriptions throw light on all aspects of Roman life and history...

, which required his services as researcher, writer, and editor, occupying Mommsen for many years. After repeated delays the projected fourth volume was eventually abandoned, or at least not completed; an early manuscript may have been lost in a fire.

In 1885, however, Mommsen had ready another work on ancient Rome, later translated into English as The Provinces of the Roman Empire. In Germany it was published as the fifth volume of his Römische Geschichte. In thirteen chapters it describes the different imperial provinces, each as a stand-alone subject. Here there was no running narration of major Roman political events, often dramatic, as was the case in Mommsen's popular chronological telling of his earlier volumes.

In 1992, a reconstruction of Mommsen's missing "fourth volume" on the Empire was issued. Its sources were lesson notes taken by two related students, Sebastian Hensel (father) and Paul Hensel (son), of lectures delivered by Prof. Mommsen during 1882-1886 regarding his courses on imperial Roman History, given at the University of Berlin. These student notes were 'discovered' in 1980 at a used bookshop in Nuremberg by Alexander Demandt

Alexander Demandt

Alexander Demandt is a German historian. He was professor of ancient history at the Free University of Berlin from 1974 to 2005. Demandt is a renowned expert of the History of Rome.-References:...

, then edited by Barbara Demandt and Alexander Demandt; the resulting German text was published in 1992. The Hensel family was distinguished, the son becoming a philosophy professor, the father writing a family history (1879) with regard to his mother's brother the composer Felix Mendelssohn

Felix Mendelssohn

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Barthóldy , use the form 'Mendelssohn' and not 'Mendelssohn Bartholdy'. The Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians gives ' Felix Mendelssohn' as the entry, with 'Mendelssohn' used in the body text...

, and the paternal grandfather being a Prussian court painter.

In English

The contemporary English translations were the work of Dr. William Purdie Dickson, a divinity professor at the University of GlasgowUniversity of Glasgow

The University of Glasgow is the fourth-oldest university in the English-speaking world and one of Scotland's four ancient universities. Located in Glasgow, the university was founded in 1451 and is presently one of seventeen British higher education institutions ranked amongst the top 100 of the...

. The first three German volumes (which contained five 'books') were published during 1862 to 1866 by R. Bentley & Son, London. Over several decades Prof. Dickson prepared further English editions of this translation, keeping pace with Mommsen's revisions in German. All told, close to a hundred editions and reprints of the English translation have been published.

In 1958 selections from the final two 'books' of the three-volume History were prepared by Dero A. Saunders

Dero A. Saunders

John P. Grier was an American journalist and classical scholar.He was born in Starkville, Mississippi. A graduate of Dartmouth College, he was executive editor of Forbes Magazine from 1960-1981, and continued to edit a regular column until 1999.As a reporter for Fortune magazine in 1957 he...

and John H. Collins

John H. Collins

John H. Collins was an American classical scholar.Born in Anaconda, Montana, he attended the University of Illinois and Cornell University, and in 1952 received his doctorate in classical history from Goethe University in Frankfurt-am-Main where he studied under Professor Matthias Gelzer, then a...

for a shorter English version. The content was chosen to highlight Mommsen's telling of the social-political struggles over several generations leading to the fall of the Republic

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic was the period of the ancient Roman civilization where the government operated as a republic. It began with the overthrow of the Roman monarchy, traditionally dated around 508 BC, and its replacement by a government headed by two consuls, elected annually by the citizens and...

. Provided with new annotations and a revised translation, the book presents an abridgment revealing the historical chronology. With rigor Mommsen is shown narrating the grave political drama and illuminating its implications; the book closes with his lengthy description of the new order of government adumbrated by Julius Caesar.

With regard to Mommsen's 1885 "fifth volume" on the Roman provinces, Prof. Dr. Dickson immediate began to supervise its translation. In 1886 it appeared as The Provinces of the Roman Empire. From Caesar to Diocletian.

Mommsen's missing fourth volume was reconstructed from student notes and published in 1992 under the title Römische Kaisergeschichte. It was soon translated into English by Clare Krojzl as A History of Rome under the Emperors.

The Republic

With exceptions, Mommsen in his Römische Geschichte (1854–1856) narrates a straight chronology of historic events and circumstances. Often strongly worded, he carefully describes the political acts taken by the protagonists, demonstrates the immediate results, draws implications for the future, while shedding light on the evolving society that surround them. The chronology of the contents of his five 'books' (in his first three volumes) are in brief:

- Book I, Roman origins and the MonarchyRoman KingdomThe Roman Kingdom was the period of the ancient Roman civilization characterized by a monarchical form of government of the city of Rome and its territories....

; - Book II, the RepublicRoman RepublicThe Roman Republic was the period of the ancient Roman civilization where the government operated as a republic. It began with the overthrow of the Roman monarchy, traditionally dated around 508 BC, and its replacement by a government headed by two consuls, elected annually by the citizens and...

until the Union of Italy; - Book III, the Punic WarsPunic WarsThe Punic Wars were a series of three wars fought between Rome and Carthage from 264 B.C.E. to 146 B.C.E. At the time, they were probably the largest wars that had ever taken place...

and the East; - Book IV, the GracchiGracchiThe Gracchi brothers, Tiberius and Gaius, were Roman Plebian nobiles who both served as tribunes in 2nd century BC. They attempted to pass land reform legislation that would redistribute the major patrician landholdings among the plebeians. For this legislation and their membership in the...

, MariusGaius MariusGaius Marius was a Roman general and statesman. He was elected consul an unprecedented seven times during his career. He was also noted for his dramatic reforms of Roman armies, authorizing recruitment of landless citizens, eliminating the manipular military formations, and reorganizing the...

, DrususMarcus Livius Drusus (tribune)The younger Marcus Livius Drusus, son of Marcus Livius Drusus, was tribune of the plebeians in 91 BC. In the manner of Gaius Gracchus, he set out with comprehensive plans, but his aim was to strengthen senatorial rule...

, and Sulla; - Book V, the Civil Wars and Julius CaesarJulius CaesarGaius Julius Caesar was a Roman general and statesman and a distinguished writer of Latin prose. He played a critical role in the gradual transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire....

.

The broad strokes of Mommsen's long, sometimes intense narrative of the Roman Republic were summarized at the 1902 award of the Nobel Prize in a speech given by the secretary of the Swedish Academy

Swedish Academy

The Swedish Academy , founded in 1786 by King Gustav III, is one of the Royal Academies of Sweden.-History:The Swedish Academy was founded in 1786 by King Gustav III. Modelled after the Académie française, it has 18 members. The motto of the Academy is "Talent and Taste"...

. At the beginning, the strength of Rome derived from the health of its families, e.g., a Roman's obedience

Potestas

Potestas is a Latin word meaning power or faculty. It is an important concept in Roman Law.-Origin of the concept:The idea of potestas originally referred to the power, through coercion, of a Roman magistrate to promulgate edicts, give action to litigants, etc. This power, in Roman political and...

to the state was associated with obedience of son to father. From here Mommsen skillfully unrolls the huge canvas of Rome's long development from rural town to world capital. An early source of stability and effectiveness was the stubbornly preserved constitution; e.g., the reformed Senate

Roman Senate

The Senate of the Roman Republic was a political institution in the ancient Roman Republic, however, it was not an elected body, but one whose members were appointed by the consuls, and later by the censors. After a magistrate served his term in office, it usually was followed with automatic...

composed of patricians and plebians generally handled public affairs of the city-state in an honorable manner.

Aristocracy

Aristocracy , is a form of government in which a few elite citizens rule. The term derives from the Greek aristokratia, meaning "rule of the best". In origin in Ancient Greece, it was conceived of as rule by the best qualified citizens, and contrasted with monarchy...

oligarchy

Oligarchy

Oligarchy is a form of power structure in which power effectively rests with an elite class distinguished by royalty, wealth, family ties, commercial, and/or military legitimacy...

began to become corrupted by the enormous wealth derived from military conquest and its aftermath; it no longer served well its functional purpose, it failed to meet new demands placed on Rome, and its members would selfishly seek to preserve inherited prerogatives against legitimate challenge and transition. A frequently unpatriotic capitalism abused its power in politics and by irresponsible speculation. The free peasantry became squeezed by the competing demands of powerful interests; accordingly its numbers began to dwindle, which eventually led to a restructuring of Army recruitment, and later resulted in disastrous consequences for the entire commonwealth.

Roman consul

A consul served in the highest elected political office of the Roman Republic.Each year, two consuls were elected together, to serve for a one-year term. Each consul was given veto power over his colleague and the officials would alternate each month...

s (the two Roman chief executives) began to adversely impact the consistent management of its armed forces, and to weaken their effectiveness, especially in the era following the Punic Wars. Eventually it led to the prolongation of military commands in the field; hence, Roman army generals became increasingly independent, and they led soldiers personally loyal to them. These military leaders began to acquire the ability to rule better than the ineffective civil institutions. In short, the civil power's political capabilities were not commensurate with the actual needs of the Roman state. As Rome's strength and reach increased, the political situation developed in which an absolute command structure imposed by military leaders at the top might, in the long run, in many cases be more successful and cause less chaos and hardship to the citizenry

Roman citizenship

Citizenship in ancient Rome was a privileged political and legal status afforded to certain free-born individuals with respect to laws, property, and governance....

than the corrupt and incompetent rule by the oligarchy of quarreling old families who de facto controlled the government. Such was his purpose when the conservative Optimate, the noble and Roman general Sulla (138-78), seized state power by military force; yet he sought without permanent success to restore the Senate nobility

Nobility

Nobility is a social class which possesses more acknowledged privileges or eminence than members of most other classes in a society, membership therein typically being hereditary. The privileges associated with nobility may constitute substantial advantages over or relative to non-nobles, or may be...

to its former power.

Political instability soon returned, social unrest being the disagreeable norm. The conservative renovation of the Republic's institutions was abandoned and taken apart. Eventually the decisive civil war victory of the incomparable Julius Caesar

Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar was a Roman general and statesman and a distinguished writer of Latin prose. He played a critical role in the gradual transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire....

(100-44), followed by his executive mastery and public-minded reforms, appeared as the necessary and welcome step forward toward resolution of the sorry and bloody debacle at Rome. This, in the dramatic narrative of Theodore Mommsen.

Imperator

The Latin word Imperator was originally a title roughly equivalent to commander under the Roman Republic. Later it became a part of the titulature of the Roman Emperors as part of their cognomen. The English word emperor derives from imperator via Old French Empreur...

(refusing the crown, yet continuing since 49 as dictator

Roman dictator

In the Roman Republic, the dictator , was an extraordinary magistrate with the absolute authority to perform tasks beyond the authority of the ordinary magistrate . The office of dictator was a legal innovation originally named Magister Populi , i.e...

), with reversion of the Senate to an advisory council, and the popular comitia as a compliant legislature, although law might be made by his edicts alone; his assumption of authority over tax and treasury, over provincial governors, and over the capital; supreme jurisdiction

Jurisdiction

Jurisdiction is the practical authority granted to a formally constituted legal body or to a political leader to deal with and make pronouncements on legal matters and, by implication, to administer justice within a defined area of responsibility...

(trial and appellate) over the continuing republican legal system, with the judex being selected among senators or equites, yet criminal courts remained corrupted by factional infighting; supreme command over the decayed Roman army

Roman army

The Roman army is the generic term for the terrestrial armed forces deployed by the kingdom of Rome , the Roman Republic , the Roman Empire and its successor, the Byzantine empire...

, which was reorganized and which remained under civilian control; reform of government finance, of bugeting re income and expense, and of corn distribution; cultivation of civil peace in Rome by control of criminal "clubs", by new city police, and by public building projects. Impossible problems: widespread slavery, disappearance of family farms, extravagance and immorality of the wealthy, dire poverty, speculation, debt; Caesar's reforms: favoring families, against absentees, restricting luxuries

Sumptuary law

Sumptuary laws are laws that attempt to regulate habits of consumption. Black's Law Dictionary defines them as "Laws made for the purpose of restraining luxury or extravagance, particularly against inordinate expenditures in the matter of apparel, food, furniture, etc." Traditionally, they were...

, debt relief (but not cancellation as demanded by populares), personal bankruptcy

Bankruptcy

Bankruptcy is a legal status of an insolvent person or an organisation, that is, one that cannot repay the debts owed to creditors. In most jurisdictions bankruptcy is imposed by a court order, often initiated by the debtor....

for unpayable debt replacing enslavement by creditors, usury

Usury

Usury Originally, when the charging of interest was still banned by Christian churches, usury simply meant the charging of interest at any rate . In countries where the charging of interest became acceptable, the term came to be used for interest above the rate allowed by law...

laws, road building, distribution of public agricultural lands in a moderated Gracchan

Gracchi

The Gracchi brothers, Tiberius and Gaius, were Roman Plebian nobiles who both served as tribunes in 2nd century BC. They attempted to pass land reform legislation that would redistribute the major patrician landholdings among the plebeians. For this legislation and their membership in the...

fashion, and new municipal law. Mommsen writes, "[W]e may well conclude that Caesar with his reforms came as near to the measure of what was possible as it was given to a statesman and a Roman to come."

Julian calendar

The Julian calendar began in 45 BC as a reform of the Roman calendar by Julius Caesar. It was chosen after consultation with the astronomer Sosigenes of Alexandria and was probably designed to approximate the tropical year .The Julian calendar has a regular year of 365 days divided into 12 months...

. "The rapidity and self-precision with which the plan was executed prove that it had been long meditated thoroughly and all its parts settled in detail", Mommsen comments. "[T]his was probably the meaning of the words which were heard to fall from him--that he had 'lived enough'."

- "The Original ConstitutionHistory of the Constitution of the Roman KingdomThe History of the Constitution of the Roman Kingdom is a study of the ancient Roman Kingdom that traces the progression of Roman political development from the founding of the city of Rome in 753 BC to the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom in 510 BC. The constitution of the Roman Kingdom vested the...

of Rome" (Book I, Chapter 5); - "The Etruscans" (I, 9);

- "Law and JusticeRoman lawRoman law is the legal system of ancient Rome, and the legal developments which occurred before the 7th century AD — when the Roman–Byzantine state adopted Greek as the language of government. The development of Roman law comprises more than a thousand years of jurisprudence — from the Twelve...

" (I, 11); - "Religion" (I, 12);

- "Agriculture, Trade, CommerceRoman commerceRoman trade was the engine that drove the Roman economy of the late Republic and the early Empire. Fashions and trends in historiography and in popular culture have tended to neglect the economic basis of the empire in favor of the lingua franca of Latin and the exploits of the Roman legions...

" (I, 13); - "Measuring and WritingLatin alphabetThe Latin alphabet, also called the Roman alphabet, is the most recognized alphabet used in the world today. It evolved from a western variety of the Greek alphabet called the Cumaean alphabet, which was adopted and modified by the Etruscans who ruled early Rome...

" (I, 14); - "The Tribunate of the Plebs and the Decemvirate" (Book II, Chapter 2);

- "Law - Religion - Military SystemRoman armyThe Roman army is the generic term for the terrestrial armed forces deployed by the kingdom of Rome , the Roman Republic , the Roman Empire and its successor, the Byzantine empire...

- Economic Condition - Nationality" (II, 8); - "Art and ScienceRoman engineeringRomans are famous for their advanced engineering accomplishments, although some of their own inventions were improvements on older ideas, concepts and inventions. Technology for bringing running water into cities was developed in the east, but transformed by the Romans into a technology...

" (II, 9); - "Carthage" (Book III, Chapter 1);

- "The Government and the GovernedSocial class in ancient RomeSocial class in ancient Rome was hierarchical, but there were multiple and overlapping social hierarchies. The status of free-born Romans was established by:* ancestry ;...

" (III, 11); - "The Management of LandRoman agricultureAgriculture in ancient Rome was not only a necessity, but was idealized among the social elite as a way of life. Cicero considered farming the best of all Roman occupations...

and Capital" (III, 12); - "Faith and Manners" (III, 13);

- "Literature and Art" (III, 14);

- "The Peoples of the North" (Book IV, Chapter 5);

- "The Commonwealth and its Economy" (IV, 11);

- "Nationality, Religion, Education" (IV, 12);

- "The Old RepublicRoman RepublicThe Roman Republic was the period of the ancient Roman civilization where the government operated as a republic. It began with the overthrow of the Roman monarchy, traditionally dated around 508 BC, and its replacement by a government headed by two consuls, elected annually by the citizens and...

and the New MonarchyRoman EmpireThe Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

" (Book V, Chapter 11); - "Religion, Culture, LiteratureLatin literatureLatin literature includes the essays, histories, poems, plays, and other writings of the ancient Romans. In many ways, it seems to be a continuation of Greek literature, using many of the same forms...

, and Art" (V, 12).

Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum

The Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum is a comprehensive collection of ancient Latin inscriptions. It forms an authoritative source for documenting the surviving epigraphy of classical antiquity. Public and personal inscriptions throw light on all aspects of Roman life and history...

project, his work on ancient dialects of Italy, the journal he began devoted to Roman coinage, his multivolume Staatsrecht on the long history of constitutional law

Roman Constitution

The Roman Constitution was an uncodified set of guidelines and principles passed down mainly through precedent. The Roman constitution was not formal or even official, largely unwritten and constantly evolving. Concepts that originated in the Roman constitution live on in constitutions to this day...

at Rome, his volumes on Roman criminal law, the Strafrecht. His bibliography lists 1500 works.

The Provinces

The Provinces of the Roman Empire (1885, 1886) contains thirteen chapters, namely: Northern Italy, Spain, GaulGaul

Gaul was a region of Western Europe during the Iron Age and Roman era, encompassing present day France, Luxembourg and Belgium, most of Switzerland, the western part of Northern Italy, as well as the parts of the Netherlands and Germany on the left bank of the Rhine. The Gauls were the speakers of...

, Germany, Britain, the Danube, Greece, Asia Minor

Anatolia

Anatolia is a geographic and historical term denoting the westernmost protrusion of Asia, comprising the majority of the Republic of Turkey...

, the Euphrates and Parthia

Parthia

Parthia is a region of north-eastern Iran, best known for having been the political and cultural base of the Arsacid dynasty, rulers of the Parthian Empire....

, Syria and the Nabataeans

Nabataeans

Thamudi3.jpgThe Nabataeans, also Nabateans , were ancient peoples of southern Canaan and the northern part of Arabia, whose oasis settlements in the time of Josephus , gave the name of Nabatene to the borderland between Syria and Arabia, from the Euphrates to the Red Sea...

, Judaea, Egypt, and the Africa province

Africa Province

The Roman province of Africa was established after the Romans defeated Carthage in the Third Punic War. It roughly comprised the territory of present-day northern Tunisia, and the small Mediterranean coast of modern-day western Libya along the Syrtis Minor...

s. Generally, each chapter describes the economic geography of a region and its people, before addressing its Imperial regime. Regarding the North, military administration is often stressed; while for the East, the culture and history.

A quarter of the way into his short "Introduction" to the Provinces Mommsen comments on the decline of Rome, the capital city: "The Roman state of this epoch resembles a mighty tree, the main stem of which, in the course of its decay, is surrounded by vigorous offshoots pushing their way upward." These shoots being the provinces he here describes.

The Empire

Alexander Demandt

Alexander Demandt is a German historian. He was professor of ancient history at the Free University of Berlin from 1974 to 2005. Demandt is a renowned expert of the History of Rome.-References:...

from lecture notes, was published as Römische Kaisergeschichte in 1992. Thus appearing many years after third volume (1856), and the fifth (1885). It contains three sections of roughly equal size.

The first section is arranged chronologically by emperor: Augustus (44 BC-AD 14); Tiberius (14-37); Gaius Caligula (37-41); Claudius (41-54); Nero (54-68); The Year of Four Emperors (68-69); Vespasian (69-79).

The chapters of the second section are entitled: General Introduction; Domestic Politics I; Wars in the West; Wars on the Danube; Wars in the East; Domestic Politics II.

The third section: General Introduction; Government and Society; A History of Events [this the longest subsection, arranged by emperors]: Diocletian (284-305); Constantine (306-337); The sons of Constantine (337-361); Julian and Jovian (355-364); Valentinian and Valens (364-378); From Theodosius to Alaric (379-410).

This rescued work contains a great wealth of material, in which one follows in the footsteps of a master historian. Yet, perhaps because of its nature as reconstructed student lecture notes, it more often lacks the fine points of literary composition and style, and of course the narrative drive of the original three volumes. Nonetheless it is well to remember that the students involved here in taking the lecture notes were themselves quite accomplished people, and one listener and recorder was already a mature father.

Roman Portraits

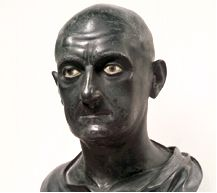

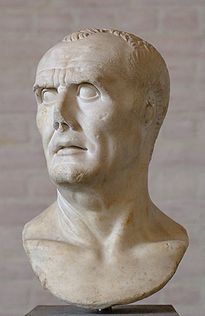

Several writers have remarked on Mommsen's ability to interpret personality and character. The following highlights are drawn from Mommsen's renderings of figures of ancient Rome, namely: Hannibal, Scipio Africanus, the Gracchi brothers, Marius, Drusus, Sulla, Pompey, Cato, Caesar, and Cicero.

- Hannibal BarcaHannibal BarcaHannibal, son of Hamilcar Barca Hannibal's date of death is most commonly given as 183 BC, but there is a possibility it could have taken place in 182 BC. was a Carthaginian military commander and tactician. He is generally considered one of the greatest military commanders in history...

(247-183). Of Carthage, not of Rome, in fact a sworn enemy of Rome, as the Roman people became acquainted with him. No Punic writer has left us an account of him, but only his 'enemies' whether Greek or Roman. Mommsen tells us, "the Romans charged him with cruelty, the Carthaginians with covetousness." It is "true that he hated" and knew "how to hate" and that "a general who never fell short of money and stores can hardly have been less than covetous. But though anger and envy and meanness have written his history, they have not been able to mar the pure and noble image which it presents." His father HamilcarHamilcar BarcaHamilcar Barca or Barcas was a Carthaginian general and statesman, leader of the Barcid family, and father of Hannibal, Hasdrubal and Mago. He was also father-in-law to Hasdrubal the Fair....

served Carthage as an army general; Hannibal's "youth had been spent in the camp." As a boy on horseback he'd become "a fearless rider at full speed." In his father's army he had performed "his first feats of arms under the paternal eye". In HispaniaHispaniaAnother theory holds that the name derives from Ezpanna, the Basque word for "border" or "edge", thus meaning the farthest area or place. Isidore of Sevilla considered Hispania derived from Hispalis....

his father spent years building colonies for Carthage from which to attack Rome; but the son saw his father "fall in battle by his side." Under his brother-in-law HasdrubalHasdrubal the FairHasdrubal the Fair was a Carthaginian military leader.He was the brother-in-law of Hannibal and son-in-law of Hamilcar Barca...

, Hannibal led cavalry with bravery and brilliance; then Hasdrubal was assassinated. By "the voice of his comrades" Hannibal at 29 years took command of the army. "[A]ll agree in this, that he combined in rare perfection discretion and enthusiasm, caution and energy." His "inventive craftiness" made him "fond of taking singular and unexpected routes; ambushes and stratagems of all sorts were familiar to him." He carefully studied the Roman character. "By an unrivalled system of espionage--he had regular spies even in Rome--he kept himself informed of the projects of his enemy." He was often seen in disguise. Yet nothing he did at war "may not be justified under the circumstances, and according to the international law, of the times." "The power which he wielded over men is shown by his incomparable control over an army of various nations and many tongues--an army which never in the worst of times mutinied against him." Following the war Hannibal the statesman served Carthage to reform the city-state's constitution; later as an exile he exercised influence in the eastern Mediterranean. "He was a great man; wherever he went, he riveted the eyes of all."

- Scipio AfricanusScipio AfricanusPublius Cornelius Scipio Africanus , also known as Scipio Africanus and Scipio the Elder, was a general in the Second Punic War and statesman of the Roman Republic...

(235-183). His father a Roman general died at war in Hispania; years earlier his son Publius Cornelius Scipio (later Africanus) had saved his life. As then no one offered to succeed to his father's post, the son offered himself. The people's comitia accepted the son for the father, "all this made a wonderful and indelible impression on the citizens and farmers of Rome." Publius Scipio "himself enthusiastic" about others, accordingly "inspired enthusiasm." The Roman SenateRoman SenateThe Senate of the Roman Republic was a political institution in the ancient Roman Republic, however, it was not an elected body, but one whose members were appointed by the consuls, and later by the censors. After a magistrate served his term in office, it usually was followed with automatic...

acquiesqued to the mere military tribuneMilitary tribuneA military tribune was an officer of the Roman army who ranked below the legate and above the centurion...

serving in place of a praetorPraetorPraetor was a title granted by the government of Ancient Rome to men acting in one of two official capacities: the commander of an army, usually in the field, or the named commander before mustering the army; and an elected magistratus assigned varied duties...

or consulConsulConsul was the highest elected office of the Roman Republic and an appointive office under the Empire. The title was also used in other city states and also revived in modern states, notably in the First French Republic...

, i.e., his father. "He was not one of the few who by their energy and iron will constrain the world to adopt and to move in new paths for centuries, or who at any rate grasp the reins of destiny for years till its wheels roll over them." Though he won battles and conquored nations, and became a prominent statesman at Rome, he was not an Alexander or a Caesar. "Yet a special charm lingers around the form of that graceful hero; it is surrounded, as if with a dazzling halo... in which Scipio with mingled credulity and adroitness always moved." His enthusiasm warmed the heart, but he did not forget the vulgar, nor fail to follow his calculations. "[N]ot naïve enough to share the belief of the multitude in his inspirations... yet in secret thoroughly persuaded that he was a man specially favored of the gods." He would accept merely to be an ordinary king, but yet the Republic's constitution applied even to heroes such as him. "[S]o confident of his own greatness that he knew nothing of envy or of hatred, [he] courteously acknowledged other men's merits, and compassionately forgave other men's faults." After his war-ending victory over Hannibal at ZamaBattle of ZamaThe Battle of Zama, fought around October 19, 202 BC, marked the final and decisive end of the Second Punic War. A Roman army led by Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus defeated a Carthaginian force led by the legendary commander Hannibal...

, he was called Africanus. He was an excellent army officer, a refined diplomat, an accomplished speaker, combining Hellenic culture with Roman. "He won the hearts of soldiers and of women, of his countrymen and of the Spaniards, of his rivals in the senateRoman SenateThe Senate of the Roman Republic was a political institution in the ancient Roman Republic, however, it was not an elected body, but one whose members were appointed by the consuls, and later by the censors. After a magistrate served his term in office, it usually was followed with automatic...

and of his greater Carthaginian antagonist. His name was soon on every ones lips, and his was the star which seemed destined to bring victory and peace to his country." Yet his nature seemed to contain "strange mixtures of genuine gold and glittering tinsel." It was said he set "the fashion to the nobility in arogance, title-hunting, and client-making." In his politics Scipio Africanus "sought support for his personal and almost dynastic opposition to the senate in the multitude." No demagogue, however, he remained content to merely be "the first burgess of Rome".

- Tiberius GracchusTiberius GracchusTiberius Sempronius Gracchus was a Roman Populares politician of the 2nd century BC and brother of Gaius Gracchus. As a plebeian tribune, his reforms of agrarian legislation caused political turmoil in the Republic. These reforms threatened the holdings of rich landowners in Italy...

(163-133). His maternal grandfather was Scipio Africanus. His father Tiberius Gracchus MajorTiberius Gracchus MajorTiberius Gracchus major or Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus was a Roman politician of the 2nd century BC...

was twice consul, a powerful man at his death in 150. The young widow Cornelia AfricanaCornelia AfricanaCornelia Scipionis Africana was the second daughter of Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus, the hero of the Second Punic War, and Aemilia Paulla. She is remembered as the perfect example of a virtuous Roman woman....

"a highly cultivated and notable woman" declined marriage to an Egyptian king to raise her children. She was "a highly cultivated and notable woman". Her eldest son Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus "in all his relations and views... belonged to the Scipionic circle" sharing its "refined and thorough culture" which was both Greek and RomanClassicsClassics is the branch of the Humanities comprising the languages, literature, philosophy, history, art, archaeology and other culture of the ancient Mediterranean world ; especially Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome during Classical Antiquity Classics (sometimes encompassing Classical Studies or...

. Tiberius "was of a good and moral disposition, of gentle aspect and quiet bearing, apparently fitted for anything rather than for an agitator of the masses." At that time political reform was widely discussed among aristocrats; yet the senateRoman SenateThe Senate of the Roman Republic was a political institution in the ancient Roman Republic, however, it was not an elected body, but one whose members were appointed by the consuls, and later by the censors. After a magistrate served his term in office, it usually was followed with automatic...