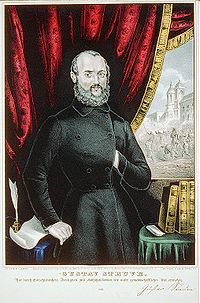

Gustav Struve

Encyclopedia

Munich

Munich The city's motto is "" . Before 2006, it was "Weltstadt mit Herz" . Its native name, , is derived from the Old High German Munichen, meaning "by the monks' place". The city's name derives from the monks of the Benedictine order who founded the city; hence the monk depicted on the city's coat...

, Bavaria

Bavaria

Bavaria, formally the Free State of Bavaria is a state of Germany, located in the southeast of Germany. With an area of , it is the largest state by area, forming almost 20% of the total land area of Germany...

– 21 August 1870 in Vienna

Vienna

Vienna is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Austria and one of the nine states of Austria. Vienna is Austria's primary city, with a population of about 1.723 million , and is by far the largest city in Austria, as well as its cultural, economic, and political centre...

, Austria

Austria

Austria , officially the Republic of Austria , is a landlocked country of roughly 8.4 million people in Central Europe. It is bordered by the Czech Republic and Germany to the north, Slovakia and Hungary to the east, Slovenia and Italy to the south, and Switzerland and Liechtenstein to the...

), was a German politician, lawyer and publicist, and a revolutionary during the German revolution of 1848-1849 in Baden. He also spent over a decade in the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

and was active there as a reformer.

Early years

Struve was born in Munich the son of a RussiaRussia

Russia or , officially known as both Russia and the Russian Federation , is a country in northern Eurasia. It is a federal semi-presidential republic, comprising 83 federal subjects...

n diplomat Johann Christoph Gustav von Struve

Johann Christoph Gustav von Struve

Johann Christoph Gustav von Struve was born on 26 September 1763 in Regensburg, in the Kingdom of Bavaria during the Holy Roman Empire of German States to notable diplomat Anton Sebastian von Struve, the Russian ambassador to the Reichstag in Regensburg...

, whose family came from the lesser nobility. His father Gustav, after whom he was named, had served as Russian Staff Councilor at the Russian Embassy in Warsaw, Munich and The Hague, and later was the Royal Russian Ambassador at the Badonian court in Karlsruhe. The younger Gustav Struve grew up and went to school in Munich, then studied law

Law

Law is a system of rules and guidelines which are enforced through social institutions to govern behavior, wherever possible. It shapes politics, economics and society in numerous ways and serves as a social mediator of relations between people. Contract law regulates everything from buying a bus...

at universities in Göttingen and Heidelberg. For a short time (from 1829 to 1831) he was employed in the civil service in Oldenburg

Oldenburg

Oldenburg is an independent city in Lower Saxony, Germany. It is situated in the western part of the state between the cities of Bremen and Groningen, Netherlands, at the Hunte river. It has a population of 160,279 which makes it the fourth biggest city in Lower Saxony after Hanover, Braunschweig...

, then moved to Baden in 1833 where in 1836 he settled down to work as a lawyer in Mannheim

Mannheim

Mannheim is a city in southwestern Germany. With about 315,000 inhabitants, Mannheim is the second-largest city in the Bundesland of Baden-Württemberg, following the capital city of Stuttgart....

.

In Baden, Struve also entered politics by standing up for the liberal members of the Baden parliament in news articles. His point of view headed more and more in a radical democratic

Democracy

Democracy is generally defined as a form of government in which all adult citizens have an equal say in the decisions that affect their lives. Ideally, this includes equal participation in the proposal, development and passage of legislation into law...

, early socialist

Socialism

Socialism is an economic system characterized by social ownership of the means of production and cooperative management of the economy; or a political philosophy advocating such a system. "Social ownership" may refer to any one of, or a combination of, the following: cooperative enterprises,...

direction. As editor of the Mannheimer Journal, he was repeatedly condemned to imprisonment. He was compelled in 1846 to retire from the management of this paper. In 1845, Struve married Amalie Düsar on 16 November 1845 and in 1847 he dropped the aristocratic "von" from his surname due to his democratic ideals.

He also gave attention to phrenology

Phrenology

Phrenology is a pseudoscience primarily focused on measurements of the human skull, based on the concept that the brain is the organ of the mind, and that certain brain areas have localized, specific functions or modules...

, and published three books on the subject.

Pre-revolutionary period

It was the time of the VormärzVormärz

' is the time period leading up to the failed March 1848 revolution in the German Confederation. Also known as the Age of Metternich, it was a period of Austrian and Prussian police states and vast censorship in response to calls for liberalism...

, the years between the Congress of Vienna

Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna was a conference of ambassadors of European states chaired by Klemens Wenzel von Metternich, and held in Vienna from September, 1814 to June, 1815. The objective of the Congress was to settle the many issues arising from the French Revolutionary Wars, the Napoleonic Wars,...

in 1815 and the revolutions of 1848-49. Struve was strongly against the politics of Metternich

Klemens Wenzel von Metternich

Prince Klemens Wenzel von Metternich was a German-born Austrian politician and statesman and was one of the most important diplomats of his era...

, a strict Conservative

Conservatism

Conservatism is a political and social philosophy that promotes the maintenance of traditional institutions and supports, at the most, minimal and gradual change in society. Some conservatives seek to preserve things as they are, emphasizing stability and continuity, while others oppose modernism...

and reactionary

Reactionary

The term reactionary refers to viewpoints that seek to return to a previous state in a society. The term is meant to describe one end of a political spectrum whose opposite pole is "radical". While it has not been generally considered a term of praise it has been adopted as a self-description by...

against the democratic movement, who ruled Austria

Austria

Austria , officially the Republic of Austria , is a landlocked country of roughly 8.4 million people in Central Europe. It is bordered by the Czech Republic and Germany to the north, Slovakia and Hungary to the east, Slovenia and Italy to the south, and Switzerland and Liechtenstein to the...

at the time and had a strong influence on restoration Germany with his Congress system.

The revolution begins

Along with Friedrich Hecker, whom he had met in Mannheim, Struve took on a leading role in the revolutions in Baden (see History of BadenHistory of Baden

The history of Baden as a state began in the 12th century, as a fief of the Holy Roman Empire. A fairly inconsequential margraviate that was divided between various branches of its ruling family for much of its history, it gained both status and territory during the Napoleonic era, when it was...

) beginning with the Hecker Uprising

Hecker Uprising

The Hecker Uprising was an attempt by Baden revolutionary leaders Friedrich Hecker, Gustav von Struve, and several other radical democrats in April 1848 to overthrow the monarchy and establish a republic in the Grand Duchy of Baden...

, also accompanied by his wife Amalie. Both Hecker and Struve belonged to the radical democratic, anti-monarch

Monarch

A monarch is the person who heads a monarchy. This is a form of government in which a state or polity is ruled or controlled by an individual who typically inherits the throne by birth and occasionally rules for life or until abdication...

ist wing of the revolutionaries. In Baden their group was particularly strong in number, with many political societies being founded in the area.

When the revolution broke out, Struve published a demand for a federal

Federation

A federation , also known as a federal state, is a type of sovereign state characterized by a union of partially self-governing states or regions united by a central government...

republic

Republic

A republic is a form of government in which the people, or some significant portion of them, have supreme control over the government and where offices of state are elected or chosen by elected people. In modern times, a common simplified definition of a republic is a government where the head of...

, to include all Germany, but this was rejected by "Pre-Parliament" (Vorparlament), the meeting of politicians and other important German figures which later became the Frankfurt Parliament

Frankfurt Parliament

The Frankfurt Assembly was the first freely elected parliament for all of Germany. Session was held from May 18, 1848 to May 31, 1849 in the Paulskirche at Frankfurt am Main...

.

Dreams of a federal Germany

Struve wanted to spread his radical dreams for a federal Germany across the country, starting in southwest Germany, and accompanied by Hecker and other revolutionary leaders. They organised the meeting of a revolutionary assembly in KonstanzKonstanz

Konstanz is a university city with approximately 80,000 inhabitants located at the western end of Lake Constance in the south-west corner of Germany, bordering Switzerland. The city houses the University of Konstanz.-Location:...

on 14 April 1848. From there, the Heckerzug (Hecker's column) was to join up with another revolutionary group led by the poet Georg Herwegh

Georg Herwegh

Georg Friedrich Rudolph Theodor Herwegh was a German revolutionary poet.-Biography:He was born in Stuttgart on 31 May 1817, the son of an innkeeper...

and march to Karlsruhe

Karlsruhe

The City of Karlsruhe is a city in the southwest of Germany, in the state of Baden-Württemberg, located near the French-German border.Karlsruhe was founded in 1715 as Karlsruhe Palace, when Germany was a series of principalities and city states...

. Few people joined in the march, however, and it was headed off in the Black Forest

Black Forest

The Black Forest is a wooded mountain range in Baden-Württemberg, southwestern Germany. It is bordered by the Rhine valley to the west and south. The highest peak is the Feldberg with an elevation of 1,493 metres ....

by troops from Frankfurt.

Hecker and Struve fled to Switzerland

Switzerland

Switzerland name of one of the Swiss cantons. ; ; ; or ), in its full name the Swiss Confederation , is a federal republic consisting of 26 cantons, with Bern as the seat of the federal authorities. The country is situated in Western Europe,Or Central Europe depending on the definition....

, where Struve continued to plan the struggle. He published Die Grundrechte des deutschen Volkes (The Basic Rights of the German People) and made a "Plan for the Revolution and Republicanisation of Germany" along with the revolutionary playwright and journalist Karl Heinzen. On 21 September 1848 he made another attempt to start an uprising in Germany, in Lörrach

Lörrach

Lörrach is a city in southwest Germany, in the valley of the Wiese, close to the French and the Swiss border. It is the capital of the district of Lörrach in Baden-Württemberg. The biggest industry is the chocolate factory Milka...

. Once again it failed, and this time Struve was caught and imprisoned.

May Uprising in Baden

Struve was freed during the May Uprising in Baden in 1849. Grand DukeGrand Duke

The title grand duke is used in Western Europe and particularly in Germanic countries for provincial sovereigns. Grand duke is of a protocolary rank below a king but higher than a sovereign duke. Grand duke is also the usual and established translation of grand prince in languages which do not...

Leopold of Baden fled and on 1 June 1849 Struve helped set up a provisionary republican parliament under the liberal politician Lorenz Brentano. Prince Wilhelm of Prussia

Prussia

Prussia was a German kingdom and historic state originating out of the Duchy of Prussia and the Margraviate of Brandenburg. For centuries, the House of Hohenzollern ruled Prussia, successfully expanding its size by way of an unusually well-organized and effective army. Prussia shaped the history...

, later to become Wilhelm I of Germany, set out for Baden with troops. Afraid of a military escalation, Brentano reacted hesitantly - too hesitantly for Struve and his followers, who overthrew him. The revolutionaries took up arms and, led by Ludwik Mieroslawski

Ludwik Mieroslawski

Ludwik Adam Mierosławski was a Polish general, writer, poet, historian and political activist. Took part in the November Uprising of 1830s, after its fall he emigrated to France, where he taught Slavic history and military theory. Chosen as a commander for the Greater Poland Uprising of 1846, he...

, tried to hold off the Prussian troops, who far outnumbered them. On 23 July the revolutionaries were defeated after a fierce battle at Rastatt

Rastatt

Rastatt is a city and baroque residence in the District of Rastatt, Baden-Württemberg, Germany. It is located on the Murg river, above its junction with the Rhine and has a population of around 50'000...

and the revolution came to an end.

Post-revolutionary life

Gustav Struve, along with other revolutionaries, managed to escape execution, fleeing to exile, first in SwitzerlandSwitzerland

Switzerland name of one of the Swiss cantons. ; ; ; or ), in its full name the Swiss Confederation , is a federal republic consisting of 26 cantons, with Bern as the seat of the federal authorities. The country is situated in Western Europe,Or Central Europe depending on the definition....

and then in 1851 to the USA.

In the USA, Struve lived for a time in Philadelphia. He edited Der Deutsche Zuschauer (The German Observer) in New York City

New York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

, but soon discontinued its publication because of insufficient support. He wrote several novels and a drama in German, and then in 1852 undertook, with the assistance of his wife, the composition of a universal history from the standpoint of radical republicanism. The result, Weltgeschichte (World History), was published in 1860. It was the major literary product of his career and the result of 30 years of study. From 1858 to 1859, he edited Die Sociale Republik.

He also promoted German public schools in New York City. In 1856, he supported John Frémont for U.S. president. In 1860, he supported Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. He successfully led his country through a great constitutional, military and moral crisis – the American Civil War – preserving the Union, while ending slavery, and...

.

At the start of the 1860s, Struve joined in the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

in the Union Army

Union Army

The Union Army was the land force that fought for the Union during the American Civil War. It was also known as the Federal Army, the U.S. Army, the Northern Army and the National Army...

, a captain under Blenker

Louis Blenker

Louis Blenker was a German and American soldier.-Life in Germany:He was born at Worms, Germany. After being trained as a goldsmith by an uncle in Kreuznach, he was sent to a polytechnical school in Munich. Against his family's wishes, he enlisted in an Uhlan regiment which accompanied Otto to...

, and one of the many German emigrant soldiers known as the Forty-Eighters

Forty-Eighters

The Forty-Eighters were Europeans who participated in or supported the revolutions of 1848 that swept Europe. In Germany, the Forty-Eighters favored unification of the German people, a more democratic government, and guarantees of human rights...

. He resigned a short time later to avoid serving under Blenker's successor, the Prussia

Prussia

Prussia was a German kingdom and historic state originating out of the Duchy of Prussia and the Margraviate of Brandenburg. For centuries, the House of Hohenzollern ruled Prussia, successfully expanding its size by way of an unusually well-organized and effective army. Prussia shaped the history...

n Prince Felix Salm-Salm

Felix Salm-Salm

-Life:Felix Constantin Alexander Johan Nepomuk, prince Salm Salm, was born in Anholt, Prussia, 25 December 1828. Felix was the son of the reigning Prince zu Salm Salm. He grew up training to be a soldier at a cadet-school in Berlin, Germany and soon became an officer in the Prussian cavalry...

. Struve was an abolitionist, and opposed plans to create a colony of freed slaves in Liberia because he thought it would hinder the abolition of slavery in the United States.

Return to Germany

He never became naturalized since he felt his primary objective was to battle the despots of Europe. In 1863, a general amnesty was issued to all those who had been involved in the revolutions in Germany, and Struve returned to Germany. His first wife had died in Staten IslandStaten Island

Staten Island is a borough of New York City, New York, United States, located in the southwest part of the city. Staten Island is separated from New Jersey by the Arthur Kill and the Kill Van Kull, and from the rest of New York by New York Bay...

in 1862. Back in Germany, he married a Frau von Centener. Lincoln appointed him U. S. consul at Sonneberg

Sonneberg

Sonneberg is a town in Thuringia, Germany, which is seat of the district Sonneberg.It has long been a centre of toy making and is still well known for this...

in 1865, but the Thuringia

Thuringia

The Free State of Thuringia is a state of Germany, located in the central part of the country.It has an area of and 2.29 million inhabitants, making it the sixth smallest by area and the fifth smallest by population of Germany's sixteen states....

n states refused to issue his exequatur due to his radical writings. In the last years of his life, he became a leading figure in the initial stage of the German vegetarian movement. He had become a vegetarian as early as 1832 under the influence of Rousseau’s treatise Émile. On 21 August 1870 he died in Vienna

Vienna

Vienna is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Austria and one of the nine states of Austria. Vienna is Austria's primary city, with a population of about 1.723 million , and is by far the largest city in Austria, as well as its cultural, economic, and political centre...

where he had settled in 1869.

Works

- Politische Briefe (Mannheim, 1846)

- Das öffentliche Recht des deutschen Bundes (2 vols., 1846)

- Grundzüge der Staatswissenschaft (4 vols., Frankfort, 1847–48)

- Geschichte der drei Volkserhebungen in Baden (Bern, 1849)

- Weltgeschichte (6 vols., New York, 1856–59; 7th ed., with a continuation, Coburg, 1866–69)

- Das Revolutionszeitalter (New York, 1859–60)

- Diesseits und jenseits des Oceans (Coburg, 1864-'5)

- Kurzgefasster Wegweiser für Auswanderer (Bamberg, 1867)

- Pflanzenkost die Grundlage einer neuen Weltanschauung (Stuttgart, 1869)

- Das Seelenleben, oder die Naturgeschichte des Menschen (Berlin, 1869)

- Eines Fürsten Jugendliebe, a drama (Vienna, 1870)

His wife Amalie published:

- Erinnerungen aus den badischen Freiheitskämpfen (Hamburg, 1850)

- Historische Zeitbilder (3 vols., Bremen, 1850)

External links

- Gustav Struve as Jewish Rights Activist

- The Democrats: Gustav von Struve: Motion in the German Pre-Parliament (March 31, 1848)

- Gustav Von Struve, from The Ethics of Diet, by Howard WilliamsHoward Williams (humanitarian)Howard Williams was an English humanitarian and vegetarian, and author of the book The Ethics of Diet, an anthology of vegetarian thought....