Wallachian Revolution of 1848

Encyclopedia

Romanians

The Romanians are an ethnic group native to Romania, who speak Romanian; they are the majority inhabitants of Romania....

liberal

Liberalism

Liberalism is the belief in the importance of liberty and equal rights. Liberals espouse a wide array of views depending on their understanding of these principles, but generally, liberals support ideas such as constitutionalism, liberal democracy, free and fair elections, human rights,...

and Romantic nationalist

Romantic nationalism

Romantic nationalism is the form of nationalism in which the state derives its political legitimacy as an organic consequence of the unity of those it governs...

uprising in the Principality of Wallachia. Part of the Revolutions of 1848

Revolutions of 1848

The European Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Spring of Nations, Springtime of the Peoples or the Year of Revolution, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe in 1848. It was the first Europe-wide collapse of traditional authority, but within a year reactionary...

, and closely connected with the unsuccessful revolt in the Principality of Moldavia, it sought to overturn the administration imposed by Imperial Russian

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

authorities under the Regulamentul Organic

Regulamentul Organic

Regulamentul Organic was a quasi-constitutional organic law enforced in 1834–1835 by the Imperial Russian authorities in Moldavia and Wallachia...

regime, and, through many of its leaders, demanded the abolition of boyar

Boyar

A boyar, or bolyar , was a member of the highest rank of the feudal Moscovian, Kievan Rus'ian, Bulgarian, Wallachian, and Moldavian aristocracies, second only to the ruling princes , from the 10th century through the 17th century....

privilege. Led by a group of young intellectual

Intellectual

An intellectual is a person who uses intelligence and critical or analytical reasoning in either a professional or a personal capacity.- Terminology and endeavours :"Intellectual" can denote four types of persons:...

s and officers in the Wallachian Militia, the movement succeeded in toppling the ruling Prince Gheorghe Bibescu

Gheorghe Bibescu

Gheorghe Bibescu was a hospodar of Wallachia between 1843 and 1848. His rule coincided with the revolutionary tide that culminated in the 1848 Wallachian revolution.-Early political career:...

, whom it replaced with a Provisional Government and a Regency

Regent

A regent, from the Latin regens "one who reigns", is a person selected to act as head of state because the ruler is a minor, not present, or debilitated. Currently there are only two ruling Regencies in the world, sovereign Liechtenstein and the Malaysian constitutive state of Terengganu...

, and in passing a series of major progressive

Progressivism

Progressivism is an umbrella term for a political ideology advocating or favoring social, political, and economic reform or changes. Progressivism is often viewed by some conservatives, constitutionalists, and libertarians to be in opposition to conservative or reactionary ideologies.The...

reforms, first announced in the Proclamation of Islaz

Proclamation of Islaz

The Proclamation of Islaz was the program adopted on June 9, 1848 by Romanian revolutionaries. It was written by Ion Heliade Rădulescu. On June 11, under pressure from the masses, Domnitor Gheorghe Bibescu was forced to accept the terms of the proclamation and recognise the provisional...

.

Despite its rapid gains and popular backing, the new administration was marked by conflicts between the radical wing

Liberalism and radicalism in Romania

This article gives an overview of Liberalism and Radicalism in Romania. It is limited to liberal parties with substantial support, mainly proved by having had a representation in parliament. The sign ⇒ denotes another party in this scheme...

and more conservative

Conservatism

Conservatism is a political and social philosophy that promotes the maintenance of traditional institutions and supports, at the most, minimal and gradual change in society. Some conservatives seek to preserve things as they are, emphasizing stability and continuity, while others oppose modernism...

forces, especially over the issue of land reform

Land reform

[Image:Jakarta farmers protest23.jpg|300px|thumb|right|Farmers protesting for Land Reform in Indonesia]Land reform involves the changing of laws, regulations or customs regarding land ownership. Land reform may consist of a government-initiated or government-backed property redistribution,...

. Two successive abortive coups were able to weaken the Government, and its international status was always contested by Russia. After managing to rally a degree of sympathy from Ottoman

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

political leaders, the Revolution was ultimately isolated by the intervention of Russian diplomats, and ultimately repressed by a common intervention of Ottoman and Russian armies, without any significant form of armed resistance. Nevertheless, over the following decade, the completion of its goals was made possible by the international context, and former revolutionaries became the original political class in united Romania

Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central and Southeastern Europe, on the Lower Danube, within and outside the Carpathian arch, bordering on the Black Sea...

.

Origins

The two Danubian PrincipalitiesDanubian Principalities

Danubian Principalities was a conventional name given to the Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, which emerged in the early 14th century. The term was coined in the Habsburg Monarchy after the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca in order to designate an area on the lower Danube with a common...

, Wallachia and Moldavia, came under direct Russian supervision upon the close of the Russo-Turkish War of 1828–1829, being subsequently administrated on the basis of common documents, known as Regulamentul Organic

Regulamentul Organic

Regulamentul Organic was a quasi-constitutional organic law enforced in 1834–1835 by the Imperial Russian authorities in Moldavia and Wallachia...

. After a period of Russian military occupation, Wallachia returned to Ottoman suzerainty

Suzerainty

Suzerainty occurs where a region or people is a tributary to a more powerful entity which controls its foreign affairs while allowing the tributary vassal state some limited domestic autonomy. The dominant entity in the suzerainty relationship, or the more powerful entity itself, is called a...

while Russian overseeing was preserved, and the throne was awarded to Alexandru II Ghica

Alexandru II Ghica

Alexandru II or Alexandru D. Ghica , a member of the Ghica family, was Prince of Wallachia from April 1834 to 7 October 1842 and later caimacam from July 1856 to October 1858....

in 1834—this measure was controversial from the onset, given that, despite the popular provisions of the Akkerman Convention

Akkerman Convention

The Akkerman Convention was a treaty signed on October 7, 1826 between the Russian and the Ottoman Empires in the Budjak citadel of Akkerman . It imposed that the hospodars of Moldavia and Wallachia be elected by their respective Divans for seven-year terms, with the approval of both Powers...

, Ghica had been appointed by Russia and the Ottomans, instead of being elected by the Wallachian Assembly. As a consequence, the Prince was faced with opposition from both sides of the political spectrum, while also attempting to quell the peasantry's malcontent by legislating against the abuse of estate lessors

Leasehold estate

A leasehold estate is an ownership of a temporary right to land or property in which a lessee or a tenant holds rights of real property by some form of title from a lessor or landlord....

. The first liberal movement, taking inspiration from the French Revolution

French Revolution

The French Revolution , sometimes distinguished as the 'Great French Revolution' , was a period of radical social and political upheaval in France and Europe. The absolute monarchy that had ruled France for centuries collapsed in three years...

and having for its stated purpose the encouragement of culture, was Societatea Filarmonică (the Philharmonic Society), established in 1833.

Hostility toward Russian policies erupted later in 1834, when Russia called for an "Additional Article" (Articol adiţional) to be attached to the Regulament, as the latter document was being reviewed by the Porte. The proposed article sought to prevent the Principalities' Assemblies from modifying the Regulament any further without the consent of both protecting powers. This move met with stiff opposition from a majority of deputies in Wallachia, among whom was the radical Ion Câmpineanu; in 1838, the project was nonetheless passed, when it was explicitly endorsed by Sultan

Ottoman Dynasty

The Ottoman Dynasty ruled the Ottoman Empire from 1299 to 1922, beginning with Osman I , though the dynasty was not proclaimed until Orhan Bey declared himself sultan...

Abdülmecid I

Abdülmecid I

Sultan Abdülmecid I, Abdul Mejid I, Abd-ul-Mejid I or Abd Al-Majid I Ghazi was the 31st Sultan of the Ottoman Empire and succeeded his father Mahmud II on July 2, 1839. His reign was notable for the rise of nationalist movements within the empire's territories...

and by Prince Ghica.

Câmpineanu, who had proposed a reformist constitution to replace the Regulament entirely, was forced into exile, but remained an influence on a younger generation of activists, both Wallachian and Moldavian. The latter group, comprising many young boyars who had studied in France, also took direct inspiration from reformist or revolutionary-minded societies such as the Carbonari

Carbonari

The Carbonari were groups of secret revolutionary societies founded in early 19th-century Italy. The Italian Carbonari may have further influenced other revolutionary groups in Spain, France, Portugal and possibly Russia. Although their goals often had a patriotic and liberal focus, they lacked a...

(and even, through Teodor Diamant, from Utopian socialism

Utopian socialism

Utopian socialism is a term used to define the first currents of modern socialist thought as exemplified by the work of Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier, and Robert Owen which inspired Karl Marx and other early socialists and were looked on favorably...

). It was this faction who would first explicitly publicize the demands for national independence and Moldo-Wallachian unification, which it included in a wider agenda of political reforms and European solidarity. Societatea Studenţilor Români (the Society of Romanian Students) was created in 1846, having the French poet Alphonse de Lamartine

Alphonse de Lamartine

Alphonse Marie Louis de Prat de Lamartine was a French writer, poet and politician who was instrumental in the foundation of the Second Republic.-Career:...

for its honorary president.

Pre-revolutionary events and outbreak

In October 1840, the first specifically revolutionary secret societySecret society

A secret society is a club or organization whose activities and inner functioning are concealed from non-members. The society may or may not attempt to conceal its existence. The term usually excludes covert groups, such as intelligence agencies or guerrilla insurgencies, which hide their...

of the period was repressed by Prince Ghica. Among those arrested and taken into confinement were the high-ranking boyar Mitică Filipescu, the young radical Nicolae Bălcescu

Nicolae Balcescu

Nicolae Bălcescu was a Romanian Wallachian soldier, historian, journalist, and leader of the 1848 Wallachian Revolution.-Early life:...

, and the much older Dimitrie Macedonski

Dimitrie Macedonski

Dimitrie Macedonski was a Wallachian Pandur captain and revolutionary leader. Taking part in the Wallachian uprising of 1821, he was appointed Tudor Vladimirescu's lieutenant by boyar allies of the revolutionaries, on January 15...

, who had taken part in the uprising of 1821

Wallachian uprising of 1821

The Wallachian uprising of 1821 was an uprising in Wallachia against Ottoman rule which took place during 1821.-Background:...

.

The new ruler, Gheorghe Bibescu

Gheorghe Bibescu

Gheorghe Bibescu was a hospodar of Wallachia between 1843 and 1848. His rule coincided with the revolutionary tide that culminated in the 1848 Wallachian revolution.-Early political career:...

, set free Bălcescu and other participants in the plot during 1843; soon afterwards, they became involved in creating a new Freemason

Freemasonry

Freemasonry is a fraternal organisation that arose from obscure origins in the late 16th to early 17th century. Freemasonry now exists in various forms all over the world, with a membership estimated at around six million, including approximately 150,000 under the jurisdictions of the Grand Lodge...

-inspired secret society, known as Frăţia ("The Brotherhood"), which was to serve as the central factor in the revolution. Early on, Frăţias nucleus was formed by Bălcescu, Ion Ghica

Ion Ghica

Ion Ghica was a Romanian revolutionary, mathematician, diplomat and twice Prime Minister of Romania . He was a full member of the Romanian Academy and its president for four times...

, Alexandru G. Golescu

Alexandru G. Golescu

Alexandru G. Golescu was a Romanian politician who served as a Prime Minister of Romania in 1870 .-Early life:...

, and Major Christian Tell

Christian Tell

Christian Tell was a Transylvanian-born Wallachian and Romanian politician.-Early life:Born in Braşov, Tell studied at Gheorghe Lazăr's school, and then at the Saint Sava Academy in Bucharest, and became close to Ion Heliade Rădulescu's version of Radicalism...

; by spring 1848, the leadership also included Dimitrie

Dimitrie Bratianu

Dimitrie Brătianu was the Prime Minister of Romania from 22 April to 21 June 1881 and Minister of Foreign Affairs from April 10, 1881 until June 8, 1881....

and Ion Brătianu

Ion Bratianu

Ion C. Brătianu was one of the major political figures of 19th century Romania. He was the younger brother of Dimitrie, as well as the father of Ionel, Dinu, and Vintilă Brătianu...

, Constantin Bălcescu, Ştefan

Stefan Golescu

Ştefan Golescu was a Wallachian Romanian politician who served as the Minister of Foreign Affairs for two terms from March 1, 1867 to August 5, 1867 and from November 13, 1867 to April 30, 1868, and as Prime Minister of Romania between November 26, 1867 and May 12, 1868.-Biography:Born in a boyar...

and Nicolae Golescu

Nicolae Golescu

Nicolae Golescu was a Wallachian Romanian politician who served as the Prime Minister of Romania in 1860 and May–November 1868.-Early life:...

, Gheorghe Magheru

Gheorghe Magheru

General Gheorghe Magheru was a Romanian revolutionary and soldier from Wallachia, and political ally of Nicolae Bălcescu.-A Pandur and radical conspirator:...

, C. A. Rosetti

C. A. Rosetti

Constantin Alexandru Rosetti was a Romanian literary and political leader, born in Bucharest into a Phanariot Greek family.In 1845, Rosetti went to Paris, where he met Alphonse de Lamartine, the patron of the Society of Romanian Students in Paris. In 1847, he married Mary Grant, the sister of the...

, Ion Heliade Rădulescu

Ion Heliade Radulescu

Ion Heliade Rădulescu or Ion Heliade was a Wallachian-born Romanian academic, Romantic and Classicist poet, essayist, memoirist, short story writer, newspaper editor and politician...

, and Ioan Voinescu II. It was especially successful in Bucharest

Bucharest

Bucharest is the capital municipality, cultural, industrial, and financial centre of Romania. It is the largest city in Romania, located in the southeast of the country, at , and lies on the banks of the Dâmbovița River....

, where it also reached out to the middle class

Middle class

The middle class is any class of people in the middle of a societal hierarchy. In Weberian socio-economic terms, the middle class is the broad group of people in contemporary society who fall socio-economically between the working class and upper class....

, and kept a legal facade as Soţietatea Literară (the Literary Society), whose meetings were attended by the Moldavians Vasile Alecsandri

Vasile Alecsandri

Vasile Alecsandri was a Romanian poet, playwright, politician, and diplomat. He collected Romanian folk songs and was one of the principal animators of the 19th century movement for Romanian cultural identity and union of Moldavia and Wallachia....

, Mihail Kogălniceanu

Mihail Kogalniceanu

Mihail Kogălniceanu was a Moldavian-born Romanian liberal statesman, lawyer, historian and publicist; he became Prime Minister of Romania October 11, 1863, after the 1859 union of the Danubian Principalities under Domnitor Alexander John Cuza, and later served as Foreign Minister under Carol I. He...

, and Costache Negruzzi, as well as by the Austrian

Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire was a modern era successor empire, which was centered on what is today's Austria and which officially lasted from 1804 to 1867. It was followed by the Empire of Austria-Hungary, whose proclamation was a diplomatic move that elevated Hungary's status within the Austrian Empire...

subject Constantin Daniel Rosenthal

Constantin Daniel Rosenthal

Constantin Daniel Rosenthal was a Romanian painter and sculptor of Hungarian birth and a 1848 revolutionary, best known for his portraits and his choice of Romanian Romantic nationalist subjects.-Early career:Born into a Jewish merchant family in Pest , he left the city...

. During the early months of 1848, Romanian students at the University of Paris

University of Paris

The University of Paris was a university located in Paris, France and one of the earliest to be established in Europe. It was founded in the mid 12th century, and officially recognized as a university probably between 1160 and 1250...

, including the Brătianu brothers, witnessed and, in some cases, took part in the French republican uprising.

Rebellion broke out in late June 1848, after Frăţias members came to adopt a single project regarding the promise of land reform

Land reform

[Image:Jakarta farmers protest23.jpg|300px|thumb|right|Farmers protesting for Land Reform in Indonesia]Land reform involves the changing of laws, regulations or customs regarding land ownership. Land reform may consist of a government-initiated or government-backed property redistribution,...

. This resolution, which had initially caused dissension, was passed into the revolutionary program upon pressures from Nicolae Bălcescu and his supporters. The document itself, destined to be read as a proclamation, was most likely drafted by Heliade Rădulescu, and Bălcescu himself was possibly responsible for most of its ideas. It called for, among other issues, national independence, civil rights

Civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from unwarranted infringement by governments and private organizations, and ensure one's ability to participate in the civil and political life of the state without discrimination or repression.Civil rights include...

and equality, universal taxation, a larger Assembly, responsible government

Responsible government

Responsible government is a conception of a system of government that embodies the principle of parliamentary accountability which is the foundation of the Westminster system of parliamentary democracy...

, a five-year term of office for Princes and their election by the Assembly, freedom of the press

Freedom of the press

Freedom of the press or freedom of the media is the freedom of communication and expression through vehicles including various electronic media and published materials...

, and decentralization

Decentralization

__FORCETOC__Decentralization or decentralisation is the process of dispersing decision-making governance closer to the people and/or citizens. It includes the dispersal of administration or governance in sectors or areas like engineering, management science, political science, political economy,...

.

.jpg)

Râmnicu Vâlcea

Râmnicu Vâlcea is the capital city of Vâlcea County, Romania .-Geography and climate:Râmnicu Vâlcea is situated in the central-south area of Romania...

, Ploieşti

Ploiesti

Ploiești is the county seat of Prahova County and lies in the historical region of Wallachia in Romania. The city is located north of Bucharest....

, Romanaţi County

Romanați County

Romanaṭi was a county in the Kingdom of Romania, in southern Oltenia. The county seat was Caracal.-Administrative organization:Administratively, Romanaṭi County was divided into five districts :# Plasa Câmpu# Plasa Dunărea...

and Islaz

Islaz

Islaz is a commune in southern Romania, located in the southwestern Teleorman County, 10 km west of Turnu Măgurele. It is part of the historical province Oltenia, and is composed of two villages, Islaz and Moldoveni....

. On June 21, 1848, Heliade Rădulescu and Tell were present in Islaz, where, with the Orthodox

Romanian Orthodox Church

The Romanian Orthodox Church is an autocephalous Eastern Orthodox church. It is in full communion with other Eastern Orthodox churches, and is ranked seventh in order of precedence. The Primate of the church has the title of Patriarch...

priest Şapcă of Celei, they revealed the revolutionary program to a cheering crowd (see Proclamation of Islaz

Proclamation of Islaz

The Proclamation of Islaz was the program adopted on June 9, 1848 by Romanian revolutionaries. It was written by Ion Heliade Rădulescu. On June 11, under pressure from the masses, Domnitor Gheorghe Bibescu was forced to accept the terms of the proclamation and recognise the provisional...

). A new government was created on the spot, comprising Tell, Heliade Rădulescu, Ştefan Golescu

Stefan Golescu

Ştefan Golescu was a Wallachian Romanian politician who served as the Minister of Foreign Affairs for two terms from March 1, 1867 to August 5, 1867 and from November 13, 1867 to April 30, 1868, and as Prime Minister of Romania between November 26, 1867 and May 12, 1868.-Biography:Born in a boyar...

, Şapcă, and Nicolae Pleşoianu—they wrote Prince Bibescu an appeal, which called on him to recognize the program as the embryo of a constitution and to "listen to the voice of the motherland and place himself at the head of this great accomplishment".

The revolutionary executive left Islaz at the head of a gathering of soldiers and various others, and, after passing through Caracal

Caracal, Romania

Caracal is a city in Olt county, Romania, situated in the historic region of Oltenia, on the plains between the lower reaches of the Jiu and Olt rivers. The region's plains are well known for their agricultural specialty in cultivating grains and over the centuries, Caracal has been the trading...

, triumphantly entered Craiova

Craiova

Craiova , Romania's 6th largest city and capital of Dolj County, is situated near the east bank of the river Jiu in central Oltenia. It is a longstanding political center, and is located at approximately equal distances from the Southern Carpathians and the River Danube . Craiova is the chief...

without meeting resistance from local forces. According to one account, the gathering comprised as many as 150,000 armed civilians. As these events were unfolding, Bibescu was shot at in Bucharest by Alexandru or Iancu Paleologu (the father of French diplomat Maurice Paléologue

Maurice Paléologue

Maurice Paléologue was a French diplomat, historian, and essayist.-Biography:Paléologue was born in Paris as the son of Alexandru Paleologu, a Wallachian Romanian revolutionary who had fled to France after attempting to assassinate Prince Gheorghe Bibescu during the 1848 Wallachian revolution;...

) and his co-conspirators, whose bullets only managed to tear one of the Prince's epaulette

Epaulette

Epaulette is a type of ornamental shoulder piece or decoration used as insignia of rank by armed forces and other organizations.Epaulettes are fastened to the shoulder by a shoulder strap or "passant", a small strap parallel to the shoulder seam, and the button near the collar, or by laces on the...

s. Over the following hours, police forces clamped down of Frăţia, arresting Rosetti and a few other members, but failing to capture most of them.

Creation

Church bell

A church bell is a bell which is rung in a church either to signify the hour or the time for worshippers to go to church, perhaps to attend a wedding, funeral, or other service...

s on Dealul Mitropoliei

Dealul Mitropoliei

Dealul Mitropoliei , also called Dealul Patriarhiei or "Patriarchate Hill", is a small hill in Bucharest, Romania and an important historic, cultural, architectural, religious and touristic point in the national capital...

began sounding the tocsin (by banging their tongues on only one side of the drum). Public readings of the Islaz Proclamation took place, and the Romanian tricolor

Flag of Romania

The national flag of Romania is a tricolour with vertical stripes: beginning from the flagpole, blue, yellow and red. It has a width-length ratio of 2:3....

was paraded throughout the city. At ten o'clock in the evening, Bibescu gave in to the pressures, signed the new constitution, and agreed to support a Provisional Government as imposed on him by Frăţia. This effectively disestablished Regulamentul Organic

Regulamentul Organic

Regulamentul Organic was a quasi-constitutional organic law enforced in 1834–1835 by the Imperial Russian authorities in Moldavia and Wallachia...

, causing the Russian consul to Bucharest, Charles de Kotzebue, to leave the country for Austrian

Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire was a modern era successor empire, which was centered on what is today's Austria and which officially lasted from 1804 to 1867. It was followed by the Empire of Austria-Hungary, whose proclamation was a diplomatic move that elevated Hungary's status within the Austrian Empire...

-ruled Transylvania

Transylvania

Transylvania is a historical region in the central part of Romania. Bounded on the east and south by the Carpathian mountain range, historical Transylvania extended in the west to the Apuseni Mountains; however, the term sometimes encompasses not only Transylvania proper, but also the historical...

. Bibescu himself abdicated

Abdication

Abdication occurs when a monarch, such as a king or emperor, renounces his office.-Terminology:The word abdication comes derives from the Latin abdicatio. meaning to disown or renounce...

and left into self-exile.

On June 25, the two proposed cabinets were reunited into Guvernul vremelnicesc (the Provisional Government), based on the Executive Commission of the Second French Republic; headed by the conservative Neofit II, the Metropolitan of Ungro-Wallachia, it consisted of Christian Tell

Christian Tell

Christian Tell was a Transylvanian-born Wallachian and Romanian politician.-Early life:Born in Braşov, Tell studied at Gheorghe Lazăr's school, and then at the Saint Sava Academy in Bucharest, and became close to Ion Heliade Rădulescu's version of Radicalism...

, Ion Heliade Rădulescu

Ion Heliade Radulescu

Ion Heliade Rădulescu or Ion Heliade was a Wallachian-born Romanian academic, Romantic and Classicist poet, essayist, memoirist, short story writer, newspaper editor and politician...

, Ştefan Golescu

Stefan Golescu

Ştefan Golescu was a Wallachian Romanian politician who served as the Minister of Foreign Affairs for two terms from March 1, 1867 to August 5, 1867 and from November 13, 1867 to April 30, 1868, and as Prime Minister of Romania between November 26, 1867 and May 12, 1868.-Biography:Born in a boyar...

, Gheorghe Magheru

Gheorghe Magheru

General Gheorghe Magheru was a Romanian revolutionary and soldier from Wallachia, and political ally of Nicolae Bălcescu.-A Pandur and radical conspirator:...

, and, for a short while, the Bucharest merchant Gheorghe Scurti. Its secretaries were C. A. Rosetti

C. A. Rosetti

Constantin Alexandru Rosetti was a Romanian literary and political leader, born in Bucharest into a Phanariot Greek family.In 1845, Rosetti went to Paris, where he met Alphonse de Lamartine, the patron of the Society of Romanian Students in Paris. In 1847, he married Mary Grant, the sister of the...

, Nicolae Bălcescu

Nicolae Balcescu

Nicolae Bălcescu was a Romanian Wallachian soldier, historian, journalist, and leader of the 1848 Wallachian Revolution.-Early life:...

, Alexandru G. Golescu

Alexandru G. Golescu

Alexandru G. Golescu was a Romanian politician who served as a Prime Minister of Romania in 1870 .-Early life:...

, and Ion Brătianu

Ion Bratianu

Ion C. Brătianu was one of the major political figures of 19th century Romania. He was the younger brother of Dimitrie, as well as the father of Ionel, Dinu, and Vintilă Brătianu...

. The Government was doubled by Ministerul vremelnicesc (the Provisional Ministry), which was dived into several offices: Ministrul dinlăuntru (the Minister of the Interior, a position held by Nicolae Golescu

Nicolae Golescu

Nicolae Golescu was a Wallachian Romanian politician who served as the Prime Minister of Romania in 1860 and May–November 1868.-Early life:...

); Ministrul dreptăţii (Justice - Ion Câmpineanu); Ministrul instrucţiei publice (Public Education - Heliade Rădulescu); Ministrul finanţii (Finance - C. N. Filipescu); Ministrul trebilor dinafară (Foreign Affairs - Ioan Voinescu II); Ministrul de războiu (War - Ioan Odobescu, later replaced by Tell); Obştescul controlor (the Public Controller - Gheorghe Niţescu). It also included Constantin Creţulescu as President of the City Council (later replaced by Cezar Bolliac

Cezar Bolliac

Cezar Bolliac or Boliac, Boliak was a Wallachian and Romanian radical political figure, amateur archaeologist, journalist and Romantic poet.-Early life:...

), Scarlat Creţulescu as Commander of the National Guard, and Mărgărit Moşoiu as Police Chief.

The Wallachian revolutionaries maintained ambiguous relations with leaders of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848

Hungarian Revolution of 1848

The Hungarian Revolution of 1848 was one of many of the European Revolutions of 1848 and closely linked to other revolutions of 1848 in the Habsburg areas...

, as well as with the latter's ethnic Romanian

Romanians

The Romanians are an ethnic group native to Romania, who speak Romanian; they are the majority inhabitants of Romania....

adversaries in Transylvania. As early as April, Bălcescu, who maintained close contacts with many Romanian Transylvanian politicians, called on August Treboniu Laurian

August Treboniu Laurian

August Treboniu Laurian was a Transylvanian Romanian politician, historian and linguist. He was born in the village of Fofeldea in Nocrich. He was a participant at the 1848 revolution, an organizer of the Romanian school and one of the founding members of the Romanian Academy.Laurian was a member...

not to oppose the unification of Transylvania and revolutionary Hungary

Hungary

Hungary , officially the Republic of Hungary , is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is situated in the Carpathian Basin and is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine and Romania to the east, Serbia and Croatia to the south, Slovenia to the southwest and Austria to the west. The...

. In parallel, secretive negotiations were carried out between Lajos Batthyány

Lajos Batthyány

Count Lajos Batthyány de Németújvár was the first Prime Minister of Hungary. He was born in Pressburg on 10 February 1807, and was executed by firing squad in Pest on 6 October 1849, the same day as the 13 Martyrs of Arad.-Career:His father was Count József Sándor Batthyány , his mother Borbála...

and Ion Brătianu, which were in connection to a project of creating a Wallachian-Hungarian confederation

Confederation

A confederation in modern political terms is a permanent union of political units for common action in relation to other units. Usually created by treaty but often later adopting a common constitution, confederations tend to be established for dealing with critical issues such as defense, foreign...

. Although it drew support from radicals, the proposal was ultimately rejected by the Hungarian side, who notably argued that this carried the danger of deteriorating relations with Russia. Progressively, Romanian Transylvanians distanced themselves from the rapprochement, and clarified that their goal was the preservation of Austrian rule, coming into open conflict with the Hungarian revolutionary authorities.

Early reforms

Romanian Cyrillic alphabet

The Romanian Cyrillic alphabet was used to write the Romanian language before 1860–1862, when it was officially replaced by a Latin-based Romanian alphabet. Cyrillic remained in occasional use until circa 1920...

as used at the time). It proclaimed all traditional civil ranks

Historical Romanian ranks and titles

This is a glossary of historical Romanian ranks and titles used in the principalities of Moldavia, Wallachia and Transylvania, and later in Romania. Many of these titles are of Slavic etymology, with some of Greek, Byzantine, Latin, and Turkish etymology; several are original...

to be destitute, indicating that the only acceptable distinctions were to be made on the basis of "virtues and services to the motherland", and creating a national guard. The Government also abolished censorship

Censorship

thumb|[[Book burning]] following the [[1973 Chilean coup d'état|1973 coup]] that installed the [[Military government of Chile |Pinochet regime]] in Chile...

, as well as capital

Capital punishment

Capital punishment, the death penalty, or execution is the sentence of death upon a person by the state as a punishment for an offence. Crimes that can result in a death penalty are known as capital crimes or capital offences. The term capital originates from the Latin capitalis, literally...

and corporal punishment

Corporal punishment

Corporal punishment is a form of physical punishment that involves the deliberate infliction of pain as retribution for an offence, or for the purpose of disciplining or reforming a wrongdoer, or to deter attitudes or behaviour deemed unacceptable...

, while ordering all political prisoner

Political prisoner

According to the Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English, a political prisoner is ‘someone who is in prison because they have opposed or criticized the government of their own country’....

s to be set free. In line with earlier demands, a call for unification of all Romanian-inhabited lands, as "one and indivisible [nation]", was officially voiced during that period. However, this view was still only shared by a relatively small and highly factionalized section of the intelligentsia

Intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a social class of people engaged in complex, mental and creative labor directed to the development and dissemination of culture, encompassing intellectuals and social groups close to them...

.

The official abolition

Abolitionism

Abolitionism is a movement to end slavery.In western Europe and the Americas abolitionism was a movement to end the slave trade and set slaves free. At the behest of Dominican priest Bartolomé de las Casas who was shocked at the treatment of natives in the New World, Spain enacted the first...

of Roma

Roma minority in Romania

The Roma constitute one of the major minorities in Romania. According to the 2002 census, they number 535,140 people or 2.5% of the total population, being the second-largest ethnic minority in Romania after Hungarians...

slavery

Slavery in Romania

Slavery existed on the territory of present-day Romania from before the founding of the principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia in 13th–14th century, until it was abolished in stages during the 1840s and 1850s. Most of the slaves were of Roma ethnicity...

was sanctioned by a decree also issued on June 26. This was the culmination of a process begun in 1843, when all state-owned slaves had been liberated, and continued in February 1847, when the Orthodox Church

Romanian Orthodox Church

The Romanian Orthodox Church is an autocephalous Eastern Orthodox church. It is in full communion with other Eastern Orthodox churches, and is ranked seventh in order of precedence. The Primate of the church has the title of Patriarch...

had followed suit and set free its own Roma labor force. The decree notably read: "The Romanian people discards the lack of humanity and the shameful sin of owning slaves and declares the freedom of privately owned slaves. Those who have so far had the sinful shame of owning slaves are forgiven by the Romanian people; and the motherland, as a good mother, shall compensate, out of its treasury, whosoever shall complain of detriment as a result of this Christian

Christianity

Christianity is a monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus as presented in canonical gospels and other New Testament writings...

deed". A three-member Commission was left to decide on the matters of legal implementation and compensation for slave owners—it comprised Bolliac, Petrache Poenaru

Petrache Poenaru

Petrache Poenaru was a Romanian inventor of the Enlightenment era.Poenaru, who had studied in Paris and Vienna and, later, completed his specialized studies in England, was a mathematician, physicist, engineer, inventor, teacher and organizer of the educational system, as well as a politician,...

, and Ioasaf Znagoveanu.

The authorities publicized their reforms by making use of new press institutions, the most circulated of which were Poporul Suveran (a magazine edited by Bălcescu, Bolliac, Grigore Alexandrescu

Grigore Alexandrescu

Grigore Alexandrescu in Bucharest was a nineteenth century Romanian poet and translator noted for his fables with political undertones.Of a noble family, he participated in secret revolutionary societies...

, Dimitrie Bolintineanu

Dimitrie Bolintineanu

Dimitrie Bolintineanu was a Romanian poet , diplomat, politician, and a participant in the revolution of 1848. He was of Macedonian Aromanian origins...

and others) and Pruncul Român (published by Rosetti and Eric Winterhalder). In parallel, the Bucharest populace could regularly hear public communiques read on the fields of Filaret (known as the "Field of Liberty").

Disputes and intrigue

Land reform

[Image:Jakarta farmers protest23.jpg|300px|thumb|right|Farmers protesting for Land Reform in Indonesia]Land reform involves the changing of laws, regulations or customs regarding land ownership. Land reform may consist of a government-initiated or government-backed property redistribution,...

and corvée

Corvée

Corvée is unfree labour, often unpaid, that is required of people of lower social standing and imposed on them by the state or a superior . The corvée was the earliest and most widespread form of taxation, which can be traced back to the beginning of civilization...

s was again brought to the forefront. Aside from the important conservative forces, opponents of the measure were to be found inside the leadership body itself, and included the moderates Heliade Rădulescu and Ioan Odobescu. Revolutionaries who favored passing land into the property of peasants were divided over the amount that was to be ceded, as well as over the issue of compensation to be paid to boyars. A compromise was reached through postponing, with a decision taken to submit all proposals to the vote of the Assembly, which was yet to be convened, instead of drafting a decree. Nevertheless, a Proclamation to estate-holders was issued (June 28, 1848), indicating that the reform was to be eventually enforced in exchange for unspecified sums, and calling on peasants to fulfill their corvées until autumn of the same year.

This appeal caused a reaction from the opposition forces: Odobescu rallied to the cause of conservatives, and, on July 1, 1848, together with his fellow officers Ioan Solomon and Grigorie Lăcusteanu, arrested the entire Government. The coup almost succeeded, being ultimately overturned by the reaction of Bucharesters, who organized street resistance against mutinied troops, mounted barricade

Barricade

Barricade, from the French barrique , is any object or structure that creates a barrier or obstacle to control, block passage or force the flow of traffic in the desired direction...

s, and, eventually, stormed into the executive's headquarters. The latter assault, led by Ana Ipătescu, resulted in the arrest of all coup leaders.

Despite this move, disputes regarding the shape of land reform continued inside the Government. On July 21, 1848, Nicolae Bălcescu obtained the issuing of a decree to create Comisia proprietăţii (the Commission on Property), comprising 34 delegates, two for each Wallachian county

Counties of Romania

The 41 judeţe and the municipality of Bucharest comprise the official administrative divisions of Romania. They also represent the European Union' s NUTS-3 geocode statistical subdivision scheme of Romania.-Overview:...

, representing respectively peasants and landlords. The new institution was presided over by the landowner Alexandru Racoviţă, and had the Moldavian-born Ion Ionescu de la Brad

Ion Ionescu de la Brad

Ion Ionescu de la Brad , born Ion Isăcescu, was a Moldavian-born Romanian revolutionary, agronomist, statistician, scholar and writer....

for its vice president.

During the proceedings, a number of boyars had switched to supporting peasants: the liberal

Liberalism and radicalism in Romania

This article gives an overview of Liberalism and Radicalism in Romania. It is limited to liberal parties with substantial support, mainly proved by having had a representation in parliament. The sign ⇒ denotes another party in this scheme...

boyar Ceauşescu, a delegate to the Commission's fourth session, made a celebrated speech in which he addressed laborers as "brothers" and deplored his own status as a landowner. An emotional audience applauded his gesture, and peasants proclaimed that God forgave Ceauşescu's deeds. Other landowners, more circumspect, asked peasants what they planned to use for compensation, for which they were to be largely responsible; according to Mihail Kogălniceanu

Mihail Kogalniceanu

Mihail Kogălniceanu was a Moldavian-born Romanian liberal statesman, lawyer, historian and publicist; he became Prime Minister of Romania October 11, 1863, after the 1859 union of the Danubian Principalities under Domnitor Alexander John Cuza, and later served as Foreign Minister under Carol I. He...

, their answer was "With these two slave's arms, we have been working for centuries and provided for all the landowners' expenses; once freed, our arms would work twice as much and rest assured that we will not leave you wanting of what the country's judgment will decide we should pay you". This reportedly caused an uproar inside the Commission.

Peasants and their supporters advocated the notion that each family was supposed to receive at least four hectare

Hectare

The hectare is a metric unit of area defined as 10,000 square metres , and primarily used in the measurement of land. In 1795, when the metric system was introduced, the are was defined as being 100 square metres and the hectare was thus 100 ares or 1/100 km2...

s of land; in their system, which made note of differences in local traditional, peasants living in wetland

Wetland

A wetland is an area of land whose soil is saturated with water either permanently or seasonally. Wetlands are categorised by their characteristic vegetation, which is adapted to these unique soil conditions....

s were to be assigned 16 pogoane (approx. eight hectares), those living in plains 14 (approx. seven hectares), inhabitants of hilly areas 11 (between five and six hectares), while people inhabiting the Southern Carpathian

Southern Carpathians

The Southern Carpathians or the Transylvanian Alps are a group of mountain ranges which divide central and southern Romania, on one side, and Serbia, on the other side. They cover part of the Carpathian Mountains that is located between the Prahova River in the east and the Timiș and Cerna Rivers...

areas were supposed to receive eight pogoane (approx. four hectares). This program was instantly rejected by many landowners, and the negotiations were ended through a decision taken by Heliade Rădulescu, when it was again decided that the ultimate resolution was a prerogative of the future Assembly. The failure to address this most significant of the problems faced by Wallachians contributed to weakening support for the revolutionary cause.

Diplomatic efforts and regency

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

Emperor Nicholas I

Nicholas I of Russia

Nicholas I , was the Emperor of Russia from 1825 until 1855, known as one of the most reactionary of the Russian monarchs. On the eve of his death, the Russian Empire reached its historical zenith spanning over 20 million square kilometers...

, Wallachian revolutionaries sought instead a rapprochement with the Ottoman

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

leadership. Efforts were made to clarify that the movement did not seek to reject Ottoman suzerainty

Suzerainty

Suzerainty occurs where a region or people is a tributary to a more powerful entity which controls its foreign affairs while allowing the tributary vassal state some limited domestic autonomy. The dominant entity in the suzerainty relationship, or the more powerful entity itself, is called a...

: for this purpose, Ion Ghica

Ion Ghica

Ion Ghica was a Romanian revolutionary, mathematician, diplomat and twice Prime Minister of Romania . He was a full member of the Romanian Academy and its president for four times...

was sent to Istanbul

Istanbul

Istanbul , historically known as Byzantium and Constantinople , is the largest city of Turkey. Istanbul metropolitan province had 13.26 million people living in it as of December, 2010, which is 18% of Turkey's population and the 3rd largest metropolitan area in Europe after London and...

as early as May 29, 1848; his mission was a momentary success, but later events led Sultan

Ottoman Dynasty

The Ottoman Dynasty ruled the Ottoman Empire from 1299 to 1922, beginning with Osman I , though the dynasty was not proclaimed until Orhan Bey declared himself sultan...

Abdülmecid I

Abdülmecid I

Sultan Abdülmecid I, Abdul Mejid I, Abd-ul-Mejid I or Abd Al-Majid I Ghazi was the 31st Sultan of the Ottoman Empire and succeeded his father Mahmud II on July 2, 1839. His reign was notable for the rise of nationalist movements within the empire's territories...

to reconsider his position, especially after being faced with Russian protests. Süleyman Paşa, Abdülmecid's brother-in-law, was dispatched to Bucharest

Bucharest

Bucharest is the capital municipality, cultural, industrial, and financial centre of Romania. It is the largest city in Romania, located in the southeast of the country, at , and lies on the banks of the Dâmbovița River....

with orders to inform on the situation and take appropriate measures.

Warmly received by the city's inhabitants and authorities, Süleyman opted to impose a series of formal moves, which were designed meant to appease Russia. He replaced the Government with a regency

Regent

A regent, from the Latin regens "one who reigns", is a person selected to act as head of state because the ruler is a minor, not present, or debilitated. Currently there are only two ruling Regencies in the world, sovereign Liechtenstein and the Malaysian constitutive state of Terengganu...

, Locotenenţa domnească, and asked for some changes to be operated in the text of the constitution (promising that these were to ensure Ottoman recognition). The new ruling body, a triumvirate

Triumvirate

A triumvirate is a political regime dominated by three powerful individuals, each a triumvir . The arrangement can be formal or informal, and though the three are usually equal on paper, in reality this is rarely the case...

, comprised Heliade Rădulescu, Nicolae Golescu

Nicolae Golescu

Nicolae Golescu was a Wallachian Romanian politician who served as the Prime Minister of Romania in 1860 and May–November 1868.-Early life:...

, and Christian Tell

Christian Tell

Christian Tell was a Transylvanian-born Wallachian and Romanian politician.-Early life:Born in Braşov, Tell studied at Gheorghe Lazăr's school, and then at the Saint Sava Academy in Bucharest, and became close to Ion Heliade Rădulescu's version of Radicalism...

.

Based on Süleyman's explicit advice, a revolutionary delegation was dispatched to Istanbul, were it was to negotiate the movement's official recognition—among the envoys were Bălcescu, Ştefan Golescu

Stefan Golescu

Ştefan Golescu was a Wallachian Romanian politician who served as the Minister of Foreign Affairs for two terms from March 1, 1867 to August 5, 1867 and from November 13, 1867 to April 30, 1868, and as Prime Minister of Romania between November 26, 1867 and May 12, 1868.-Biography:Born in a boyar...

, and Dimitrie Bolintineanu

Dimitrie Bolintineanu

Dimitrie Bolintineanu was a Romanian poet , diplomat, politician, and a participant in the revolution of 1848. He was of Macedonian Aromanian origins...

. By that moment, Russian diplomats had persuaded the Porte to adopt a more reserved attitude, and to replace Süleyman with a rapporteur

Rapporteur

Rapporteur is used in international and European legal and political contexts to refer to a person appointed by a deliberative body to investigate an issue or a situation....

for the Divan

Divan

A divan was a high governmental body in a number of Islamic states, or its chief official .-Etymology:...

, Fuat Pasha

Keçecizade Mehmet Fuat Pasha

Mehmed Fuad Pasha was an Ottoman statesman known for his leadership during the Crimean War and in the Tanzimat reforms within the Ottoman Empire. He was also a noted Freemason.- Career :...

. In parallel, Russia ordered its troops in Bessarabia

Bessarabia

Bessarabia is a historical term for the geographic region in Eastern Europe bounded by the Dniester River on the east and the Prut River on the west....

to prepare for an intervention over the Prut River and into Bucharest—the prospect of a Russo-Turkish war was inconvenient for Abdülmecid, at a time when the French Second Republic

French Second Republic

The French Second Republic was the republican government of France between the 1848 Revolution and the coup by Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte which initiated the Second Empire. It officially adopted the motto Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité...

and the United Kingdom

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the formal name of the United Kingdom during the period when what is now the Republic of Ireland formed a part of it....

failed to clarify they position in respect to Ottoman policies. Stratford Canning

Stratford Canning, 1st Viscount Stratford de Redcliffe

Stratford Canning, 1st Viscount Stratford de Redcliffe KG GCB PC , was a British diplomat and politician, best known as the longtime British Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire...

, the British Ambassador to the Porte, even advised Ottoman officials to intervene against the Revolution, thus serving Prime Minister

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the Head of Her Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom. The Prime Minister and Cabinet are collectively accountable for their policies and actions to the Sovereign, to Parliament, to their political party and...

Palmerston

Henry Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston

Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston, KG, GCB, PC , known popularly as Lord Palmerston, was a British statesman who served twice as Prime Minister in the mid-19th century...

's policy regarding the preservation of Ottoman rule in front of outside pressures. The Wallachian delegation was denied reception, and, after a prolonged stay, had to return to Bucharest.

Metropolitan Neofit's coup

On July 11, 1848, the false rumor that the Imperial Russian ArmyMilitary history of Imperial Russia

The Military history of the Russian Empire encompasses the history of armed conflict in which the Empire participated. This history stretches from its creation in 1721 by Peter the Great, until the Russian Revolution , which led to the establishment of the Soviet Union...

had left Bessarabia and was moving southwards cause the regency to leave Bucharest and take refuge in Târgovişte

Târgoviste

Târgoviște is a city in the Dâmbovița county of Romania. It is situated on the right bank of the Ialomiţa River. , it had an estimated population of 89,000. One village, Priseaca, is administered by the city.-Name:...

. This occurred after Russia had occupied Moldavia in April, a result of the unsuccessful revolt in that country. The moment was seized by conservatives: headed by Metropolitan Neofit, the latter grouping took over, and announced that the revolution had ended. When a revolutionary courier returned from the Moldavian town of Focşani

Focsani

Focşani is the capital city of Vrancea County in Romania on the shores the Milcov river, in the historical region of Moldavia. It has a population of 101,854.-Geography:...

with news that Russian troops had not left their quarters, the population in the capital prepared for action—during the events, Ambrozie, a priest from the Buzău Bishopric, made himself the revolutionary hero of the hour and earned the nickname Popa Tun, the "Cannon Priest", after ripping out the lit fuse of a gun aimed at the crowds. The outcome caused Neofit to invalidate his own proclamation, and to transfer his power back to the Provisional Government (July 12).

Over the following months, the population radicalized itself, and, on September 18, 1848, just one week before the Revolution was crushed, crowds entered the Interior Ministry, taking over the official copies of Regulamentul Organic

Regulamentul Organic

Regulamentul Organic was a quasi-constitutional organic law enforced in 1834–1835 by the Imperial Russian authorities in Moldavia and Wallachia...

and the register of boyar ranks

Historical Romanian ranks and titles

This is a glossary of historical Romanian ranks and titles used in the principalities of Moldavia, Wallachia and Transylvania, and later in Romania. Many of these titles are of Slavic etymology, with some of Greek, Byzantine, Latin, and Turkish etymology; several are original...

(Arhondologia). The documents were subsequently paraded through the city in a mock funeral cortege, and burned down, one sheet at a time, in the public square on Mitropoliei Hill. Neofit reluctantly agreed to preside over the ceremony and to issue a curse

Curse

A curse is any expressed wish that some form of adversity or misfortune will befall or attach to some other entity—one or more persons, a place, or an object...

on both pieces of legislation.

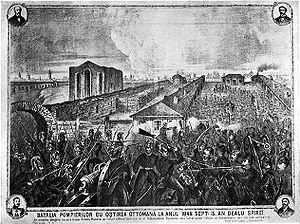

Suppression

On , Ottoman troops headed by Omar PashaOmar Pasha

Omar Pasha Latas was a Ottoman general and governor. He was a Serb convert to Islam, who managed to quickly climb in Ottoman ranks, crush several rebellions throughout the Empire and defeat Russia the Crimean War.-Early life:...

and assisted by Fuat Pasha

Keçecizade Mehmet Fuat Pasha

Mehmed Fuad Pasha was an Ottoman statesman known for his leadership during the Crimean War and in the Tanzimat reforms within the Ottoman Empire. He was also a noted Freemason.- Career :...

stormed into Bucharest, partly as an attempt to prevent the extension of Russian presence over the Milcov River. On the morning of that day, Fuat met with local public figures at his headquarters in Cotroceni

Cotroceni

Cotroceni is a neighbourhood in western Bucharest, Romania located around the Cotroceni hill, in Bucharest's Sector 6.The Hill of Cotroceni was once covered by the forest of Vlăsia, which covered most of today's Bucharest...

, proclaiming the reestablishment of the Regulament and appointing Constantin Cantacuzino as Kaymakam

Kaymakam

Qaim Maqam or Qaimaqam or Kaymakam is the title used for the governor of a provincial district in the Republic of Turkey, Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus and in Lebanon; additionally, it was a title used for roughly the same official position in the Ottoman...

of Wallachia. While all revolutionaries who attended the meeting were placed under arrest, Ion Heliade Rădulescu

Ion Heliade Radulescu

Ion Heliade Rădulescu or Ion Heliade was a Wallachian-born Romanian academic, Romantic and Classicist poet, essayist, memoirist, short story writer, newspaper editor and politician...

and Christian Tell

Christian Tell

Christian Tell was a Transylvanian-born Wallachian and Romanian politician.-Early life:Born in Braşov, Tell studied at Gheorghe Lazăr's school, and then at the Saint Sava Academy in Bucharest, and became close to Ion Heliade Rădulescu's version of Radicalism...

sought refuge at the British consulate in Bucharest, where they were received by Robert Gilmour Colquhoun

Robert Gilmour Colquhoun

Sir Robert Gilmour Colquhoun, KCB was a British diplomat.He was educated at Pembroke College, Oxford. He was appointed Consul in Bucharest, Romania on 18 January 1835, Consul-General on 15 December 1837, and Agent and Consul-General on 18 November 1851. He received the Order of the Nichan Iftikhar...

in exchange for a sum of Austrian florins

Austro-Hungarian gulden

The Gulden or forint was the currency of the Austrian Empire and later the Austro-Hungarian Empire between 1754 and 1892 when it was replaced by the Krone/korona as part of the introduction of the gold standard. In Austria, the Gulden was initially divided into 60 Kreuzer, and in Hungary, the...

.

Gheorghe Magheru

General Gheorghe Magheru was a Romanian revolutionary and soldier from Wallachia, and political ally of Nicolae Bălcescu.-A Pandur and radical conspirator:...

had planned resistance on the Danube

Danube

The Danube is a river in the Central Europe and the Europe's second longest river after the Volga. It is classified as an international waterway....

, but their opinion had failed to rally significant appeal. A group of several thousands soldiers, comprising Oltenia

Oltenia

Oltenia is a historical province and geographical region of Romania, in western Wallachia. It is situated between the Danube, the Southern Carpathians and the Olt river ....

n pandur

Pandur

Pandur can refer to:* Pandurs, Balkan Slavic guerrilla fighters* Pandur, an armoured personnel carrier:* Pandur I 6x6* Pandur II 8x8* The Sumerian term for long-necked lutes...

s and volunteers from throughout the land, rallied in Râmnicu Vâlcea

Râmnicu Vâlcea

Râmnicu Vâlcea is the capital city of Vâlcea County, Romania .-Geography and climate:Râmnicu Vâlcea is situated in the central-south area of Romania...

under Magheru's command, without ever going into action. In Bucharest itself, as Fuat prepared to lead his troops into the garrison on Dealul Spirii

Dealul Spirii

Dealul Spirii is a hill in Bucharest, Romania, upon which, currently, the Palace of the Parliament is located....

, a detachment of firemen met him with resistance, provoking a brief exchange of fire, during which several soldiers on both sides were killed. In the evening, the entire city had been pacified. On September 27, a Russian force under Alexander von Lüders

Alexander von Lüders

Count Alexander Nikolajewitsch von Lüders was a Russian general and Namestnik of the Kingdom of Poland.Lüders was born to a German noble family that moved to Russia in the middle of the 18th century...

joined the occupation of Bucharest, taking over administration over one half of the city. Russia's expedition into the two Danubian Principalities

Danubian Principalities

Danubian Principalities was a conventional name given to the Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, which emerged in the early 14th century. The term was coined in the Habsburg Monarchy after the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca in order to designate an area on the lower Danube with a common...

was the only independent military initiative of her foreign interventions against the Revolutions of 1848

Revolutions of 1848

The European Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Spring of Nations, Springtime of the Peoples or the Year of Revolution, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe in 1848. It was the first Europe-wide collapse of traditional authority, but within a year reactionary...

.

Immediately after the events, 91 revolutionaries were sentenced to exile. Of these, a small group was transported by barge

Barge

A barge is a flat-bottomed boat, built mainly for river and canal transport of heavy goods. Some barges are not self-propelled and need to be towed by tugboats or pushed by towboats...

s from Giurgiu

Giurgiu

Giurgiu is the capital city of Giurgiu County, Romania, in the Greater Wallachia. It is situated amid mud-flats and marshes on the left bank of the Danube facing the Bulgarian city of Rousse on the opposite bank. Three small islands face the city, and a larger one shelters its port, Smarda...

, on their way to the Austrian

Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire was a modern era successor empire, which was centered on what is today's Austria and which officially lasted from 1804 to 1867. It was followed by the Empire of Austria-Hungary, whose proclamation was a diplomatic move that elevated Hungary's status within the Austrian Empire...

-ruled Sviniţa

Svinita

Sviniţa is a commune in Mehedinţi County, Romania, located on the Danube . It is composed of a single village, Sviniţa. In 2002, its population numbered 1,132 people and was mostly composed of Serbs...

, near the Danube port of Orschowa

Orsova

Orșova is a port city on the Danube river in southwestern Romania's Mehedinți County. It is one of four localities in the county located in the Banat historical region. It is situated just above the Iron Gates, on the spot where the Cerna River meets the Danube.- History :The first documented...

. The revolutionary artist Constantin Daniel Rosenthal

Constantin Daniel Rosenthal

Constantin Daniel Rosenthal was a Romanian painter and sculptor of Hungarian birth and a 1848 revolutionary, best known for his portraits and his choice of Romanian Romantic nationalist subjects.-Early career:Born into a Jewish merchant family in Pest , he left the city...

and Maria Rosetti

Maria Rosetti

Maria Rosetti was an English-born Wallachian and Romanian political activist, journalist, essayist, philanthropist and socialite. The sister of British diplomat Effingham Grant and wife of radical leader C. A. Rosetti, she played an active part in the Wallachian Revolution of 1848...

, both of whom had been allowed to go free and had subsequently followed the barges on shore, pointed out that the Ottomans had stepped out of their jurisdiction, and were able to persuade the mayor of Sviniţa to disarm the guards, which in turn allowed the prisoners to flee. The escapees then made their way to Paris.

Most other revolutionaries were detained in areas of present-day Bulgaria

Bulgaria

Bulgaria , officially the Republic of Bulgaria , is a parliamentary democracy within a unitary constitutional republic in Southeast Europe. The country borders Romania to the north, Serbia and Macedonia to the west, Greece and Turkey to the south, as well as the Black Sea to the east...

until spring 1849, and, passing through Rustchuk

Rousse

Ruse is the fifth-largest city in Bulgaria. Ruse is situated in the northeastern part of the country, on the right bank of the Danube, opposite the Romanian city of Giurgiu, from the capital Sofia and from the Bulgarian Black Sea Coast...

and Varna

Varna

Varna is the largest city and seaside resort on the Bulgarian Black Sea Coast and third-largest in Bulgaria after Sofia and Plovdiv, with a population of 334,870 inhabitants according to Census 2011...

, were taken to the Anatolia

Anatolia

Anatolia is a geographic and historical term denoting the westernmost protrusion of Asia, comprising the majority of the Republic of Turkey...

n city of Brusa, where they lived at the expense of the Ottoman state. They were allowed to return after 1856. During their period of exile, rivalry between the various factions became obvious, a conflict which became the basis for political allegiances in later years.

In the meantime, Magheru, upon the advice of Colquhoun, ordered the demobilization

Demobilization

Demobilization is the process of standing down a nation's armed forces from combat-ready status. This may be as a result of victory in war, or because a crisis has been peacefully resolved and military force will not be necessary...

of his troops (October 10), and, accompanied by a few of his officers, passed the Southern Carpathians

Southern Carpathians

The Southern Carpathians or the Transylvanian Alps are a group of mountain ranges which divide central and southern Romania, on one side, and Serbia, on the other side. They cover part of the Carpathian Mountains that is located between the Prahova River in the east and the Timiș and Cerna Rivers...

into Hermannstadt

Sibiu

Sibiu is a city in Transylvania, Romania with a population of 154,548. Located some 282 km north-west of Bucharest, the city straddles the Cibin River, a tributary of the river Olt...

—at the time, the Transylvania

Transylvania

Transylvania is a historical region in the central part of Romania. Bounded on the east and south by the Carpathian mountain range, historical Transylvania extended in the west to the Apuseni Mountains; however, the term sometimes encompasses not only Transylvania proper, but also the historical...

n city was nominally in the Austrian Empire, but gripped by the Hungarian Revolution

Hungarian Revolution of 1848

The Hungarian Revolution of 1848 was one of many of the European Revolutions of 1848 and closely linked to other revolutions of 1848 in the Habsburg areas...

.

Wallachian activities in Transylvania

Starting in December 1848, a number of Wallachian revolutionaries who had escaped or had been set free from arrest began mediating an understanding between Hungary's Lajos KossuthLajos Kossuth

Lajos Kossuth de Udvard et Kossuthfalva was a Hungarian lawyer, journalist, politician and Regent-President of Hungary in 1849. He was widely honored during his lifetime, including in the United Kingdom and the United States, as a freedom fighter and bellwether of democracy in Europe.-Family:Lajos...

and those Romanian Transylvanian activists and peasants who, under the leadership of Avram Iancu

Avram Iancu

Avram Iancu was a Transylvanian Romanian lawyer who played an important role in the local chapter of the Austrian Empire Revolutions of 1848–1849. He was especially active in the Ţara Moţilor region and the Apuseni Mountains...

, were mounting military resistance to the Honvédség troops of Józef Bem

Józef Bem

Józef Zachariasz Bem was a Polish general, an Ottoman Pasha and a national hero of Poland and Hungary, and a figure intertwined with other European nationalisms...

. Bălcescu emerged from his refuge in the Principality of Serbia, and, together with Alexandru G. Golescu

Alexandru G. Golescu

Alexandru G. Golescu was a Romanian politician who served as a Prime Minister of Romania in 1870 .-Early life:...

and Ion Ionescu de la Brad

Ion Ionescu de la Brad

Ion Ionescu de la Brad , born Ion Isăcescu, was a Moldavian-born Romanian revolutionary, agronomist, statistician, scholar and writer....

, began talks with Iancu in Zlatna

Zlatna

Zlatna is a town in Alba County, central Transylvania, Romania. It has a population of 8,607.- Administration :The town administers eighteen villages: Boteşti , Budeni , Dealu Roatei , Dobrot, Dumbrava, Feneş , Galaţi , Izvoru Ampoiului , Pârău Gruiului , Pătrângeni ,...

. The Wallachians presented Kossuth's proposal that Iancu's fighters should leave their base in the Apuseni

Apuseni Mountains

The Apuseni Mountains is a mountain range in Transylvania, Romania, which belongs to the Western Carpathians, also called Occidentali in Romanian. Their name translates from Romanian as Mountains "of the sunset" i.e. "western". The highest peak is "Cucurbăta Mare" - 1849 metres, also called Bihor...

and help rekindle revolution in Wallachia, leaving room for Hungary to resist Russian invention, but the offer was dismissed on the spot. In parallel, Magheru reached out to Hungarian authorities, asking them to consider confederating Hungary-proper and Transylvania; this plan was also rejected.

On May 26, 1849, Bălcescu met with Kossuth in Debrecen

Debrecen

Debrecen , is the second largest city in Hungary after Budapest. Debrecen is the regional centre of the Northern Great Plain region and the seat of Hajdú-Bihar county.- Name :...

, and, despite his personal disappointment with the Hungarian discourse and his ideal of full political rights for Romanians in the region, agreed to mediate an understanding with Iancu, which resulted in a ceasefire

Ceasefire

A ceasefire is a temporary stoppage of a war in which each side agrees with the other to suspend aggressive actions. Ceasefires may be declared as part of a formal treaty, but they have also been called as part of an informal understanding between opposing forces...

and a series of political concessions. This came as Russian troops were entering Transylvania, a military operation culminating in Hungarian defeat at the Battle of Segesvár

Battle of Segesvár

The Battle of Segesvár was a battle in the Hungarian Revolution of 1848, fought on 31 July 1849 between the Hungarian revolutionary army supplemented by Polish volunteers under the command of General Józef Bem and the Russian V Corps under General Alexander von Lüders in ally with the Austrian...

in late July.

Political outcome

Treaty of Balta Liman

The Treaties of Balta Liman were both signed in Balta-Liman with the Ottoman Empire as one of its signatories.-1838:The Treaty of Balta Liman was a commercial treaty signed in 1838 between the Ottoman Empire and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, regulating international trade...

awarded the Wallachian crown to Barbu Dimitrie Ştirbei

Barbu Dimitrie Stirbei

Barbu Dimitrie Ştirbei , a member of the Bibescu boyar family, was a Prince of Wallachia on two occasions, in 1848–1853 and in 1854–1856.-Early life:...

. In contrast to the 1848–1849 setbacks, the period inaugurated by the Crimean War

Crimean War

The Crimean War was a conflict fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the French Empire, the British Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Sardinia. The war was part of a long-running contest between the major European powers for influence over territories of the declining...

disestablished both Russian domination and the Regulamentul Organic

Regulamentul Organic

Regulamentul Organic was a quasi-constitutional organic law enforced in 1834–1835 by the Imperial Russian authorities in Moldavia and Wallachia...

regime, and, within the space of one generation, brought about the fulfillment of virtually all revolutionary projects. The common actions of Moldavians and Wallachians, in pace with the presence of Wallachian activists in Transylvania, helped circulate the ideal of national unity, with the ultimate goal of reuniting all majority-Romanian territories within one state.

In early 1859, at the close of a turbulent period, Wallachia and Moldavia entered a personal union

United Principalities

The United Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, also known as the Romanian Principalities, was the official name of Romania following the 1859 election of Alexandru Ioan Cuza as prince or domnitor of both territories...

, later formalized as the Principality of Romania

Kingdom of Romania

The Kingdom of Romania was the Romanian state based on a form of parliamentary monarchy between 13 March 1881 and 30 December 1947, specified by the first three Constitutions of Romania...

, under Moldavian-born Domnitor

Domnitor

Domnitor was the official title of the ruler of the United Principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia between 1859 and 1866....

Alexander John Cuza

Alexander John Cuza

Alexander John Cuza was a Moldavian-born Romanian politician who ruled as the first Domnitor of the United Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia between 1859 and 1866.-Early life:...

(himself a former revolutionary). Having been allowed to return from exile after the Treaty of Paris

Treaty of Paris (1856)

The Treaty of Paris of 1856 settled the Crimean War between Russia and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the British Empire, Second French Empire, and the Kingdom of Sardinia. The treaty, signed on March 30, 1856 at the Congress of Paris, made the Black Sea neutral territory, closing it to all...

, most of the surviving revolutionaries played a major part in the political developments, and organized themselves as Partida Naţională

Partida Nationala

The Partida Naţională was a liberal Romanian political party active between 1856 and 1859. It was a loose group which supported the union of the Danubian Principalities....

, which promoted Cuza during simultaneous elections for the ad-hoc Divans. The role of Paris-based Wallachian émigré

Émigré

Émigré is a French term that literally refers to a person who has "migrated out", but often carries a connotation of politico-social self-exile....

s in promoting sympathy for common Romanian goals was decisive. Partida succeeded in becoming the major factor in Romanian political life, before forming the basis of the liberal current

Liberalism and radicalism in Romania

This article gives an overview of Liberalism and Radicalism in Romania. It is limited to liberal parties with substantial support, mainly proved by having had a representation in parliament. The sign ⇒ denotes another party in this scheme...

. With Cuza's rule, the pace of Westernization

Westernization

Westernization or Westernisation , also occidentalization or occidentalisation , is a process whereby societies come under or adopt Western culture in such matters as industry, technology, law, politics, economics, lifestyle, diet, language, alphabet,...

increased, and, during the 1860s, a moderate land reform

Land reform

[Image:Jakarta farmers protest23.jpg|300px|thumb|right|Farmers protesting for Land Reform in Indonesia]Land reform involves the changing of laws, regulations or customs regarding land ownership. Land reform may consist of a government-initiated or government-backed property redistribution,...

was carried out, monastery estates were secularized

Secularization of monastery estates in Romania

The law on the secularization of monastery estates in Romania was proposed in December 1863 by Domnitor Alexandru Ioan Cuza and approved by the Parliament of Romania. By its terms, the Romanian state confiscated the large estates owned by the Eastern Orthodox Church in Romania...

, while corvée

Corvée

Corvée is unfree labour, often unpaid, that is required of people of lower social standing and imposed on them by the state or a superior . The corvée was the earliest and most widespread form of taxation, which can be traced back to the beginning of civilization...

s and boyar ranks

Historical Romanian ranks and titles

This is a glossary of historical Romanian ranks and titles used in the principalities of Moldavia, Wallachia and Transylvania, and later in Romania. Many of these titles are of Slavic etymology, with some of Greek, Byzantine, Latin, and Turkish etymology; several are original...

were outlawed.

Following an 1866 conflict between the increasingly authoritarian

Authoritarianism

Authoritarianism is a form of social organization characterized by submission to authority. It is usually opposed to individualism and democracy...