January 1927

Encyclopedia

February 1927

The following events occurred in February, 1927.January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - December-February 1, 1927 :*In its third year of conferring B.A...

– March

March 1927

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in March 1927-March 1, 1927 :...

– April

April 1927

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in April 1927:-April 1, 1927 :...

– May

May 1927

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in May 1927.-May 1, 1927 :...

– June

June 1927

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in June 1927.-June 1, 1927 :...

– July

July 1927

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in July 1927:-July 1, 1927 :...

– August

August 1927

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in August 1927:-August 1, 1927 :...

– September

September 1927

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in September 1927:-September 1, 1927 :...

– October

October 1927

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in October 1927:-October 1, 1927 :...

– November

November 1927

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in November 1927:-November 1, 1927 :...

– December

December 1927

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October 1927 - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in December 1927:-December 1, 1927:...

The following events occurred in January 1927.

January 1, 1927 (Saturday)

- The British Broadcasting Corporation was created by royal charter as a publicly funded company, with 773 employees. The first BBC news bulletin was delivered at on January 3

- The 1927 Rose Bowl1927 Rose BowlThe 1927 Rose Bowl Game was a college football bowl game held on January 1, 1927 in Pasadena, California. The game featured the Alabama Crimson Tide, of the Southern Conference, and Stanford, of the Pacific Coast Conference, now the Pacific-10 Conference. It was Stanford's second Rose Bowl game in...

matched two of the nation's unbeaten and untied college footballCollege footballCollege football refers to American football played by teams of student athletes fielded by American universities, colleges, and military academies, or Canadian football played by teams of student athletes fielded by Canadian universities...

teams, with the Stanford IndiansStanford Cardinal footballThe Stanford Cardinal football program represents Stanford University in college football at the NCAA Division I FBS level and is a member of the Pac-12 Conference's North Division. Stanford, the top-ranked academic institution with an FBS program, has a highly successful football tradition. The...

(10–0–0) against the Alabama Crimson Tide (9–0–0). Stanford led, 7–0, until the final minute, when Alabama blocked a punt, recovered the ball on the 14, and nullified the victory with a 7–7 tie. - MassachusettsMassachusettsThe Commonwealth of Massachusetts is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States of America. It is bordered by Rhode Island and Connecticut to the south, New York to the west, and Vermont and New Hampshire to the north; at its east lies the Atlantic Ocean. As of the 2010...

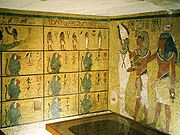

became the first state in the U.S. to require car owners to carry liability insurance. - The tomb of TutankhamunTutankhamunTutankhamun , Egyptian , ; approx. 1341 BC – 1323 BC) was an Egyptian pharaoh of the 18th dynasty , during the period of Egyptian history known as the New Kingdom...

was opened for public viewing for the first time since the Egyptian pharaoh's death in 1327 BC. - Imperial Chemical IndustriesImperial Chemical IndustriesImperial Chemical Industries was a British chemical company, taken over by AkzoNobel, a Dutch conglomerate, one of the largest chemical producers in the world. In its heyday, ICI was the largest manufacturing company in the British Empire, and commonly regarded as a "bellwether of the British...

was created in Great Britain by the merger of four companies. - Born: Doak WalkerDoak WalkerEwell Doak Walker, Jr. was an American football player who is a member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame. He was a teammate of Bobby Layne in high school and the NFL.-Early life:...

, American football player (Detroit Lions 1950–55), in Dallas (d.1998); and Vernon L. SmithVernon L. SmithVernon Lomax Smith is professor of economics at Chapman University's Argyros School of Business and Economics and School of Law in Orange, California, a research scholar at George Mason University Interdisciplinary Center for Economic Science, and a Fellow of the Mercatus Center, all in Arlington,...

, American economist, Nobel Prize 2002, in WichitaWichita, KansasWichita is the largest city in the U.S. state of Kansas.As of the 2010 census, the city population was 382,368. Located in south-central Kansas on the Arkansas River, Wichita is the county seat of Sedgwick County and the principal city of the Wichita metropolitan area...

January 2, 1927 (Sunday)

- The Cristero WarCristero WarThe Cristero War of 1926 to 1929 was an uprising and counter-revolution against the Mexican government in power at that time. The rebellion was set off by the strict enforcement of the anti-clerical provisions of the Mexican Constitution of 1917 and the expansion of further anti-clerical laws...

began in villages across MexicoMexicoThe United Mexican States , commonly known as Mexico , is a federal constitutional republic in North America. It is bordered on the north by the United States; on the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; on the southeast by Guatemala, Belize, and the Caribbean Sea; and on the east by the Gulf of...

in the Los Altos region of the state of JaliscoJaliscoJalisco officially Estado Libre y Soberano de Jalisco is one of the 31 states which, with the Federal District, comprise the 32 Federal Entities of Mexico. It is located in Western Mexico and divided in 125 municipalities and its capital city is Guadalajara.It is one of the more important states...

. The uprising began in protest against anti-clerical laws in Mexico and the rebels called themselves "Cristeros" as fighters for so named because they fought for Christ.

January 3, 1927 (Monday)

- British concessionsConcession (territory)In international law, a concession is a territory within a country that is administered by an entity other than the state which holds sovereignty over it. This is usually a colonizing power, or at least mandated by one, as in the case of colonial chartered companies.Usually, it is conceded, that...

in ChinaChinaChinese civilization may refer to:* China for more general discussion of the country.* Chinese culture* Greater China, the transnational community of ethnic Chinese.* History of China* Sinosphere, the area historically affected by Chinese culture...

, located at HankouHankouHankou was one of the three cities whose merging formed modern-day Wuhan, the capital of the Hubei province, China. It stands north of the Han and Yangtze Rivers where the Han falls into the Yangtze...

(Hankow) and JiujiangJiujiangJiujiang , formerly transliterated Kiukiang, is a prefecture-level city located on the southern shores of the Yangtze River in northwest Jiangxi Province, China. It is the second-largest prefecture-level city in Jiangxi province, the largest one being Nanchang...

(Kiukiang) were invaded by crowds of protesters against British imperialism. A British soldier fired into the crowd at Hankou, killing one protestor and wounding dozens of others. Within days, Britain relinquished control of both concessions to the Chinese government, but soon sent troops to protect its concession at ShanghaiShanghaiShanghai is the largest city by population in China and the largest city proper in the world. It is one of the four province-level municipalities in the People's Republic of China, with a total population of over 23 million as of 2010...

.

January 4, 1927 (Tuesday)

- Boris RtcheouloffBoris RtcheouloffBoris Rtcheouloff / Rcheulishvili was a Georgian scientist, and the inventor of “videotape”. He applied for a British patent on January 4, 1927 for a technique of recording television signals on 'a magnetic record of the Poulsen telegraphone type'. Sound would be recorded in sync on the reverse side...

filed a patent application for "Means of recording and reproudcing pictures, images and the like", the first means for magnetic recording of a television signal onto a moving strip. British patent no. 288,680 was granted in 1928, but the forerunner of videotapeVideotapeA videotape is a recording of images and sounds on to magnetic tape as opposed to film stock or random access digital media. Videotapes are also used for storing scientific or medical data, such as the data produced by an electrocardiogram...

was never manufactured.

January 5, 1927 (Wednesday)

- A force of 160 United States Marines was dispatched to NicaraguaNicaraguaNicaragua is the largest country in the Central American American isthmus, bordered by Honduras to the north and Costa Rica to the south. The country is situated between 11 and 14 degrees north of the Equator in the Northern Hemisphere, which places it entirely within the tropics. The Pacific Ocean...

for the purpose of protecting the American embassy in ManaguaManaguaManagua is the capital city of Nicaragua as well as the department and municipality by the same name. It is the largest city in Nicaragua in terms of population and geographic size. Located on the southwestern shore of Lake Xolotlán or Lake Managua, the city was declared the national capital in...

. The Marines arrived the next day at Corinto on the USS GalvestonUSS Galveston (CL-19)USS Galveston was a Denver-class protected cruiser in the United States Navy during World War I. She was the first Navy ship named for the city of Galveston, Texas.Galveston was laid down 19 January 1901 by William R...

. - Born: Satguru Sivaya SubramuniyaswamiSatguru Sivaya SubramuniyaswamiSivaya Subramuniyaswami , also known as Gurudeva by his followers, was born in Oakland, California, on January 5, 1927, and adopted Saivism as a young man. He traveled to India and Sri Lanka where he received initiation from Yogaswami of Jaffna in 1949...

, Hindu guru, author and publisher; as Robert Hansen in Oakland, CA (d. 2001)

January 6, 1927 (Thursday)

- Robert G. ElliottRobert G. ElliottRobert Greene Elliott was the "state electrician" for the State of New York – and for those neighboring states which used the electric chair, including New Jersey, Vermont, and Massachusetts – during the period 1926-1939.He was born in Hamlin, New York, to an Irish immigrant...

, the state electricianState Electrician"State Electrician" was the euphemistic title given to some American state executioners in states using the electric chair during the early twentieth century....

for several states, carried out six executions in the electric chair in the same day. In the morning, he put to death Edward Hinlein, John Devereaux and John McGlaughlin in Boston for the 1925 murder of a night watchman. Elliott then caught a train to New York, had dinner, took his family to the movies, and then went up to Sing SingSing SingSing Sing Correctional Facility is a maximum security prison operated by the New York State Department of Correctional Services in the town of Ossining, New York...

, where he carried out the capital punishment for Charles Goldson, Edgar Humes and George Williams for the 1926 murder of another watchman.

January 7, 1927 (Friday)

- At 8:44 am in New York CityNew York CityNew York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

and in LondonLondonLondon is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

, the first transatlantic telephoneTelephoneThe telephone , colloquially referred to as a phone, is a telecommunications device that transmits and receives sounds, usually the human voice. Telephones are a point-to-point communication system whose most basic function is to allow two people separated by large distances to talk to each other...

call was made between the two cities. Walter S. Gifford of AT&TAT&TAT&T Inc. is an American multinational telecommunications corporation headquartered in Whitacre Tower, Dallas, Texas, United States. It is the largest provider of mobile telephony and fixed telephony in the United States, and is also a provider of broadband and subscription television services...

was connected with Sir G. Evelyn V. Murray of the General Post OfficeGeneral Post OfficeGeneral Post Office is the name of the British postal system from 1660 until 1969.General Post Office may also refer to:* General Post Office, Perth* General Post Office, Sydney* General Post Office, Melbourne* General Post Office, Brisbane...

. A half minute later, the two were talking. - Philo T. Farnsworth, a 20 year old American inventor, filed his first of many patent applications, for a method of electronically scanning images and transmitting them as a televisionTelevisionTelevision is a telecommunication medium for transmitting and receiving moving images that can be monochrome or colored, with accompanying sound...

signal. U.S. Patent No. 1,773,980 was granted on August 26, 1930. - The Harlem GlobetrottersHarlem GlobetrottersThe Harlem Globetrotters are an exhibition basketball team that combines athleticism, theater and comedy. The executive offices for the team are currently in downtown Phoenix, Arizona; the team is owned by Shamrock Holdings, which oversees the various investments of the Roy E. Disney family.Over...

played their very first game, against a local team in Hinckley, IllinoisHinckley, IllinoisHinckley is a village in Squaw Grove Township, DeKalb County, Illinois, United States. The population was 2,070 at the 2010 census, up from 1,994 at the 2000 census.-History:...

. Founded by Abe SapersteinAbe SapersteinAbraham M. Saperstein was an owner and coach of the Savoy Big Five, which later became the Harlem Globetrotters...

, the all African-American team was originally called "Saperstein's New York", before assuming its current name in the 1930s. - Shadow LawnSummer White HousesA "Summer White House" is typically the name given to the regular vacation residence of the sitting President of the United States aside from Camp David, the mountain-based military camp in Frederick County, Maryland, used as a country retreat and for high-alert protection of Presidents and their...

, the West Long Branch, New JerseyWest Long Branch, New JerseyWest Long Branch is a borough in Monmouth County, New Jersey, United States. As of the 2010 United States Census, the borough population was 8,097. It is the home of Monmouth University....

, home that had served as the "Summer White House" for Woodrow WilsonWoodrow WilsonThomas Woodrow Wilson was the 28th President of the United States, from 1913 to 1921. A leader of the Progressive Movement, he served as President of Princeton University from 1902 to 1910, and then as the Governor of New Jersey from 1911 to 1913...

from 1916 to 1920, was destroyed by a fire.

January 8, 1927 (Saturday)

- The Kate Adams, last of the "side-wheeler"Paddle steamerA paddle steamer is a steamship or riverboat, powered by a steam engine, using paddle wheels to propel it through the water. In antiquity, Paddle wheelers followed the development of poles, oars and sails, where the first uses were wheelers driven by animals or humans...

steamboats in the United States, was destroyed by fire while at its moorings in MemphisMemphis, TennesseeMemphis is a city in the southwestern corner of the U.S. state of Tennessee, and the county seat of Shelby County. The city is located on the 4th Chickasaw Bluff, south of the confluence of the Wolf and Mississippi rivers....

, TennesseeTennesseeTennessee is a U.S. state located in the Southeastern United States. It has a population of 6,346,105, making it the nation's 17th-largest state by population, and covers , making it the 36th-largest by total land area...

.

January 9, 1927 (Sunday)

- Laurier Palace Theatre fireLaurier Palace Theatre FireThe Laurier Palace Theatre fire, sometimes known as the Saddest fire or the Laurier Palace Theatre crush, was a small fire that occurred in a movie theatre in Montreal, Quebec, Canada on Sunday, January 9, 1927. The fire — reportedly caused by a discarded cigarette smouldering beneath wooden...

: Seventy-eight children were killed in a panic that followed the outbreak of a fire at the Laurier Palace cinema in MontrealMontrealMontreal is a city in Canada. It is the largest city in the province of Quebec, the second-largest city in Canada and the seventh largest in North America...

. Shortly after the 2:00 matinee began, flames were spotted. On three of the theatre's four fire exits, the evacuation was orderly, but on the stairway at the east side of the building, children were trampled five steps away from the door. The dead ranged in age from 4 to 16. Only one of the victims was older than 18. - For the first time in the 368 year history of the Index Librorum ProhibitorumIndex Librorum ProhibitorumThe Index Librorum Prohibitorum was a list of publications prohibited by the Catholic Church. A first version was promulgated by Pope Paul IV in 1559, and a revised and somewhat relaxed form was authorized at the Council of Trent...

, the Roman Catholic Church's list of prohibited books, a newspaper was banned by papal decree. The French royalist daily Action FrançaiseAction FrançaiseThe Action Française , founded in 1898, is a French Monarchist counter-revolutionary movement and periodical founded by Maurice Pujo and Henri Vaugeois and whose principal ideologist was Charles Maurras...

was banned by Pope Pius XI for articles "written against the Holy See and the supreme pontiff himself".

January 10, 1927 (Monday)

- Fritz LangFritz LangFriedrich Christian Anton "Fritz" Lang was an Austrian-American filmmaker, screenwriter, and occasional film producer and actor. One of the best known émigrés from Germany's school of Expressionism, he was dubbed the "Master of Darkness" by the British Film Institute...

's silent science fiction film MetropolisMetropolis (film)Metropolis is a 1927 German expressionist film in the science-fiction genre directed by Fritz Lang. Produced in Germany during a stable period of the Weimar Republic, Metropolis is set in a futuristic urban dystopia and makes use of this context to explore the social crisis between workers and...

had its world premiere at the Ufa-Palast am Zoo in BerlinBerlinBerlin is the capital city of Germany and is one of the 16 states of Germany. With a population of 3.45 million people, Berlin is Germany's largest city. It is the second most populous city proper and the seventh most populous urban area in the European Union...

. - In a special message to Congress, President Coolidge said that the 15 American warships and 5,000 members of the Navy and the Marines would be dispatched toward NicaraguaNicaraguaNicaragua is the largest country in the Central American American isthmus, bordered by Honduras to the north and Costa Rica to the south. The country is situated between 11 and 14 degrees north of the Equator in the Northern Hemisphere, which places it entirely within the tropics. The Pacific Ocean...

and MexicoMexicoThe United Mexican States , commonly known as Mexico , is a federal constitutional republic in North America. It is bordered on the north by the United States; on the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; on the southeast by Guatemala, Belize, and the Caribbean Sea; and on the east by the Gulf of...

to protect American interests. On the same day, the U.S. Department of the Navy announced that 800 U.S. Marines would be sent to ChinaChinaChinese civilization may refer to:* China for more general discussion of the country.* Chinese culture* Greater China, the transnational community of ethnic Chinese.* History of China* Sinosphere, the area historically affected by Chinese culture...

to for the same purpose, to be transported from GuamGuamGuam is an organized, unincorporated territory of the United States located in the western Pacific Ocean. It is one of five U.S. territories with an established civilian government. Guam is listed as one of 16 Non-Self-Governing Territories by the Special Committee on Decolonization of the United...

by the cruiser USS Huron. - Born: Gisele MacKenzieGisele MacKenzieGisèle MacKenzie was a Canadian-American singer, most famous for her performances on the popular television program Your Hit Parade.-Biography:...

, Canadian-born singer, in WinnipegWinnipegWinnipeg is the capital and largest city of Manitoba, Canada, and is the primary municipality of the Winnipeg Capital Region, with more than half of Manitoba's population. It is located near the longitudinal centre of North America, at the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers .The name...

(d. 2003); Johnnie RayJohnnie RayJohnnie Ray was an American singer, songwriter, and pianist. Popular for most of the 1950s, Ray has been cited by critics as a major precursor of what would become rock and roll, for his jazz and blues-influenced music and his animated stage personality.-Early life:John Alvin Ray was born in...

, American singer (Cry), in Hopewell, OregonHopewell, OregonHopewell is an unincorporated community in Yamhill County, Oregon, United States. It is located at the eastern terminus of Oregon Route 153, ten miles south of Dayton and a few miles west of Wheatland, at the east base of the Eola Hills....

(d. 1990); and Otto StichOtto StichOtto Stich is a Swiss politician.He was elected to the Federal Council of Switzerland on 7 December 1983 and handed over office on 31 October 1995. He is affiliated to the Social Democratic Party....

, Swiss Federal CouncilSwiss Federal CouncilThe Federal Council is the seven-member executive council which constitutes the federal government of Switzerland and serves as the Swiss collective head of state....

executive 1983–1995; President, 1988 and 1994

January 11, 1927 (Tuesday)

- Thirty-six Hollywood celebrities gathered at the Ambassador Hotel in Los AngelesLos ÁngelesLos Ángeles is the capital of the province of Biobío, in the commune of the same name, in Region VIII , in the center-south of Chile. It is located between the Laja and Biobío rivers. The population is 123,445 inhabitants...

and founded the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and SciencesAcademy of Motion Picture Arts and SciencesThe Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences is a professional honorary organization dedicated to the advancement of the arts and sciences of motion pictures...

, for the purpose of acknowledging cinematic excellence. The Academy's awards for motion picture industry would later be nicknamed "The Oscars". - The American freighter John Tracy, with 27 men on board, foundered and sank off of Cape CodCape CodCape Cod, often referred to locally as simply the Cape, is a cape in the easternmost portion of the state of Massachusetts, in the Northeastern United States...

during a winter storm. Wreckage, including the vessel's nameplate was recovered ten days later. - Died: Houston Chamberlain, 71, British anti-Semite turned German Nazi. His book The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century was an inspiration for the Nazi ideology.

January 12, 1927 (Wednesday)

- Major League baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain LandisKenesaw Mountain LandisKenesaw Mountain Landis was an American jurist who served as a federal judge from 1905 to 1922 and as the first Commissioner of Baseball from 1920 until his death...

exonerated 21 members of the Detroit TigersDetroit TigersThe Detroit Tigers are a Major League Baseball team located in Detroit, Michigan. One of the American League's eight charter franchises, the club was founded in Detroit in as part of the Western League. The Tigers have won four World Series championships and have won the American League pennant...

and the Chicago White SoxChicago White SoxThe Chicago White Sox are a Major League Baseball team located in Chicago, Illinois.The White Sox play in the American League's Central Division. Since , the White Sox have played in U.S. Cellular Field, which was originally called New Comiskey Park and nicknamed The Cell by local fans...

from accusations of were absolved of conspiring to bring about a Detroit loss in four game series in 1917.

January 13, 1927 (Thursday)

- At TampicoTampicoTampico is a city and port in the state of Tamaulipas, in the country of Mexico. It is located in the southeastern part of the state, directly north across the border from Veracruz. Tampico is the third largest city in Tamaulipas, and counts with a population of 309,003. The Metropolitan area of...

, MexicoMexicoThe United Mexican States , commonly known as Mexico , is a federal constitutional republic in North America. It is bordered on the north by the United States; on the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; on the southeast by Guatemala, Belize, and the Caribbean Sea; and on the east by the Gulf of...

, the British steamer Essex Isles exploded while its cargo of gasoline barrels was being unloaded. Thirty-seven men, mostly Mexican dockworkers, died in the accident. - BelgiumBelgiumBelgium , officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a federal state in Western Europe. It is a founding member of the European Union and hosts the EU's headquarters, and those of several other major international organisations such as NATO.Belgium is also a member of, or affiliated to, many...

became the first European power to renounce any claims to use of territory in ChinaChinaChinese civilization may refer to:* China for more general discussion of the country.* Chinese culture* Greater China, the transnational community of ethnic Chinese.* History of China* Sinosphere, the area historically affected by Chinese culture...

, and ceded back a concession that had been granted to it at TianjinTianjin' is a metropolis in northern China and one of the five national central cities of the People's Republic of China. It is governed as a direct-controlled municipality, one of four such designations, and is, thus, under direct administration of the central government...

. - Born: Brock AdamsBrock AdamsBrockman "Brock" Adams was an American politician and member of Congress. Adams was a Democrat from Washington and served as a U.S. Representative, Senator, and United States Secretary of Transportation before retiring in January 1993.Adams was born in Atlanta, Georgia, and attended the public...

, U.S. Congressman for Washington 1965–77, and U.S. Senator 1987–93, in Atlanta, GeorgiaGeorgia (U.S. state)Georgia is a state located in the southeastern United States. It was established in 1732, the last of the original Thirteen Colonies. The state is named after King George II of Great Britain. Georgia was the fourth state to ratify the United States Constitution, on January 2, 1788...

(d.2004); and Sydney BrennerSydney BrennerSydney Brenner, CH FRS is a South African biologist and a 2002 Nobel prize in Physiology or Medicine laureate, shared with H...

, South African biologist, Nobel Prize winner 2002; in Germiston, GautengGermiston, GautengGermiston is a city in the East Rand of Gauteng in South Africa. Germiston is now the seat of the Ekurhuleni Metropolitan Municipality which includes much of the East Rand, and is also considered part of Greater Johannesburg.-History:...

January 14, 1927 (Friday)

- With four days left in her term, TexasTexasTexas is the second largest U.S. state by both area and population, and the largest state by area in the contiguous United States.The name, based on the Caddo word "Tejas" meaning "friends" or "allies", was applied by the Spanish to the Caddo themselves and to the region of their settlement in...

Governor Miriam A. FergusonMiriam A. FergusonMiriam Amanda Wallace "Ma" Ferguson was the first female Governor of Texas in 1925. She held office until 1927, later winning another term in 1933 and serving until 1935.-Early life:...

(known popularly as "Ma Ferguson") halted further grants of clemency to Texas convicts. The lame duck governor had pardoned or commuted the sentences of a record 3,595 persons convicted of crimes, including 1,350 full pardons.

January 15, 1927 (Saturday)

- Scopes TrialScopes TrialThe Scopes Trial—formally known as The State of Tennessee v. John Thomas Scopes and informally known as the Scopes Monkey Trial—was a landmark American legal case in 1925 in which high school science teacher, John Scopes, was accused of violating Tennessee's Butler Act which made it unlawful to...

: In a split decision, the Tennessee Supreme CourtTennessee Supreme CourtThe Tennessee Supreme Court is the state supreme court of the state of Tennessee. Cornelia Clark is the current Chief Justice.Unlike other states, in which the state attorney general is directly elected or appointed by the governor or state legislature, the Tennessee Supreme Court appoints the...

upheld the constitutionlity of Section 49-1922 of the Tennessee Code, which prohibited the teaching of evolution. The Court set aside the order for the fine levied against teacher John T. ScopesJohn T. ScopesJohn Thomas Scopes , was a biology teacher in Dayton, Tennessee, who was charged on May 5, 1925 for violating Tennessee's Butler Act, which prohibited the teaching of evolution in Tennessee schools...

. Chief Justice Grafton GreenGrafton GreenGrafton Green was an American jurist who served on the Tennessee Supreme Court from 1910 to 1947, including more than 23 years as chief justice....

said, "All of us agree that nothing is to be gained by prolonging the life of this bizarre case."

January 16, 1927 (Sunday)

- George YoungGeorge Young (swimmer)George Young was a Canadian marathon swimmer who on 15–16 January 1927 became the first swimmer to swim the channel between Catalina Island and the mainland of California. This took place during a contest called the Wrigley Ocean Marathon, sponsored by chewing gum and sports magnate William...

, a 17 year old from Toronto, became the first person to swim the 22 miles between Catalina Island, California, and the mainland. At noon the previous day, 102 competitors dived into the waters for the prize offered by William Wrigley, Jr. Young was the only person to finish the task, arriving at the Point Vincente Lighthouse at

January 17, 1927 (Monday)

- Charlie ChaplinCharlie ChaplinSir Charles Spencer "Charlie" Chaplin, KBE was an English comic actor, film director and composer best known for his work during the silent film era. He became the most famous film star in the world before the end of World War I...

was ordered to pay $4,000 a month alimony to his wife, Lita GreyLita GreyLita Grey was an American actress and the second wife of Charlie Chaplin. She was born in Hollywood, California, in 1908, to a Mexican-born mother and a father of Irish heritage and christened Lillita Louise MacMurray.-Personal life:Grey married four times...

Chaplin, by a Los Angeles court. The same day, the Internal Revenue Service filed a lien against Chaplin for seven years of back taxes and penalties, totalling $1,073,721.47 between 1918 and 1924. - Born: Eartha KittEartha KittEartha Mae Kitt was an American singer, actress, and cabaret star. She was perhaps best known for her highly distinctive singing style and her 1953 hit recordings of "C'est Si Bon" and the enduring Christmas novelty smash "Santa Baby." Orson Welles once called her the "most exciting woman in the...

, American actress and singer, in North, SC (d. 2008) - Died: Juliette Low, founder of the Girl Scouts

January 18, 1927 (Tuesday)

- American ratification of the 1923 Treaty of LausanneTreaty of LausanneThe Treaty of Lausanne was a peace treaty signed in Lausanne, Switzerland on 24 July 1923, that settled the Anatolian and East Thracian parts of the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire. The treaty of Lausanne was ratified by the Greek government on 11 February 1924, by the Turkish government on 31...

, and the establishment of diplomatic relations with TurkeyTurkeyTurkey , known officially as the Republic of Turkey , is a Eurasian country located in Western Asia and in East Thrace in Southeastern Europe...

, failed to get approval in the U.S. Senate. Though favored by a 50–34 margin, a two-thirds majority was needed. - The Food, Drug, and Insecticide AdministrationFood and Drug AdministrationThe Food and Drug Administration is an agency of the United States Department of Health and Human Services, one of the United States federal executive departments...

was established as part of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Thomas L. Purvis, A Dictionary of American History (Wiley-Blackwell, 1997) p138

January 19, 1927 (Wednesday)

- The first legislative session held in The Council HouseParliament of IndiaThe Parliament of India is the supreme legislative body in India. Founded in 1919, the Parliament alone possesses legislative supremacy and thereby ultimate power over all political bodies in India. The Parliament of India comprises the President and the two Houses, Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha...

of India (now the Parliament House) was opened with a meeting of the Central Legislative Assembly. The House, a circular building covering nearly six acres, is now part of the Parliament Assembly where the Lok SabhaLok SabhaThe Lok Sabha or House of the People is the lower house of the Parliament of India. Members of the Lok Sabha are elected by direct election under universal adult suffrage. As of 2009, there have been fifteen Lok Sabhas elected by the people of India...

and the Rajya SabhaRajya SabhaThe Rajya Sabha or Council of States is the upper house of the Parliament of India. Rajya means "state," and Sabha means "assembly hall" in Sanskrit. Membership is limited to 250 members, 12 of whom are chosen by the President of India for their expertise in specific fields of art, literature,...

convene. - Died: Empress Carlota of Mexico, 86, Belgian princess whose husband reigned as Emperor Maximilian I of Mexico from 1864 to 1867.

January 20, 1927 (Thursday)

- Frank L. SmithFrank L. SmithFrank Leslie Smith was an Illinois politician. He served as a United States Congressman from 1919 to 1921. He was elected by the people of Illinois to the United States Senate in 1926, but the Senate never allowed him to take his seat.He first ran for the Republican nomination for the U.S....

, recently selected to serve as a United States Senator from IllinoisIllinoisIllinois is the fifth-most populous state of the United States of America, and is often noted for being a microcosm of the entire country. With Chicago in the northeast, small industrial cities and great agricultural productivity in central and northern Illinois, and natural resources like coal,...

, was not allowed to take the oath of office. The U.S. Senate voted 48–33 against seating him pending further investigation of the financing of his 1926 primary election campaign.

January 21, 1927 (Friday)

- The Movietone sound systemMovietone sound systemThe Movietone sound system is a sound-on-film method of recording sound for motion pictures that guarantees synchronization between sound and picture. It achieves this by recording the sound as a variable-density optical track on the same strip of film that records the pictures...

, developed by Fox Film Corporation (later 20th Century Fox20th Century FoxTwentieth Century Fox Film Corporation — also known as 20th Century Fox, or simply 20th or Fox — is one of the six major American film studios...

) was first demonstrated to the public, at the Sam H. Harris Theatre in New York City. Shown by a movie projector equipped to play sound-on-filmSound-on-filmSound-on-film refers to a class of sound film processes where the sound accompanying picture is physically recorded onto photographic film, usually, but not always, the same strip of film carrying the picture. Sound-on-film processes can either record an analog sound track or digital sound track,...

, the one-reel film preceded the feature presentation, What Price Glory?. Though not quite synchronized, the film included the sight and sound of popular singer Raquel Meller.

January 22, 1927 (Saturday)

- A bus, carrying the Baylor UniversityBaylor Bears men's basketballThe Baylor Bears basketball team represents Baylor University in Waco, Texas, in NCAA Division I men's basketball competition. The Bears compete in the Big 12 Conference. The team plays its home games in Ferrell Center and is currently coached by Scott Drew....

basketball team to a scheduled game against the University of Texas, was struck at a railroad crossing near Round Rock, TexasRound Rock, TexasRound Rock is a city in Travis and Williamson counties in the U.S. state of Texas. It is part of the metropolitan area. The 2010 census places the population at 99,887....

. Eleven people were killed and four seriously injured. - The first sports broadcast in the United Kingdom was made by BBC RadioBBC RadioBBC Radio is a service of the British Broadcasting Corporation which has operated in the United Kingdom under the terms of a Royal Charter since 1927. For a history of BBC radio prior to 1927 see British Broadcasting Company...

, with Teddy WakelamTeddy WakelamCaptain Henry Blythe Thornhill Wakelam was an English sports broadcaster and rugby union player.He played rugby for Harlequin F.C. and became its captain. On 15 January 1927 Wakelam gave the first ever running sports commentary on BBC radio, a Rugby International match, England v Wales at...

providing the play-by-play of a soccer football game between Arsenal and Sheffield United. Subscribers to Radio Times could follow the game with a diagram, designed by producer Lance SievekingLance SievekingLance Sieveking was an English writer and pioneer BBC radio and television producer. He was married three times, and was father to archaeologist Gale Sieveking and Fortean-writer Paul Sieveking .-Biography:...

, that divided the field into eight squares. The game ended in a 1–1 draw. - The Tamanweis, a war ceremonial for the Swinomish American Indian tribe, was performed for the first time since it had been outlawed by federal law. The occasion, a celebration at La Conner, WashingtonLa Conner, WashingtonLa Conner is a town in Skagit County, Washington, United States with a population of 891 at the 2010 census. It is included in the Mount Vernon–Anacortes, Washington Metropolitan Statistical Area. In the month of April, the town annually hosts the majority of the Skagit Valley Tulip Festival...

, of the 1855 Mukiliteo peace treaty, also saw a traditional feast and the playing of the game "Fla-Hal"

January 23, 1927 (Sunday)

- Ban JohnsonBan JohnsonByron Bancroft "Ban" Johnson , was an American executive in professional baseball who served as the founder and first president of the American League ....

, who had been President of baseball's American LeagueAmerican LeagueThe American League of Professional Baseball Clubs, or simply the American League , is one of two leagues that make up Major League Baseball in the United States and Canada. It developed from the Western League, a minor league based in the Great Lakes states, which eventually aspired to major...

since its founding in 1900, was fired by vote of the league's eight teams. Johnson had publicly criticized the ruling, by baseball commissioner Landis, on the Black Sox ScandalBlack Sox ScandalThe Black Sox Scandal took place around and during the play of the American baseball 1919 World Series. Eight members of the Chicago White Sox were banned for life from baseball for intentionally losing games, which allowed the Cincinnati Reds to win the World Series...

. Eight years remained on his contract, so he retained his title, but his duties were assumed by Frank J. Navin of the Detroit TigersDetroit TigersThe Detroit Tigers are a Major League Baseball team located in Detroit, Michigan. One of the American League's eight charter franchises, the club was founded in Detroit in as part of the Western League. The Tigers have won four World Series championships and have won the American League pennant...

. - California Attorney GeneralCalifornia Attorney GeneralThe California Attorney General is the State Attorney General of California. The officer's duty is to ensure that "the laws of the state are uniformly and adequately enforced" The Attorney General carries out the responsibilities of the office through the California Department of Justice.The...

Ulysses S. WebbUlysses S. WebbUlysses Sigel Webb Born in West Virginia, an American lawyer and politician affiliated with the Republican Party. He served as the 19th Attorney General of California for the lengthy span of 37 years. Webb's parents were Cyrus Webb, a civil war captain, and Eliza Cather-Webb. He was educated in...

rendered an attorney general opinion that dark-skinned Mexican-Americans could be classified as "American Indians" under the state's school segregation law.

January 24, 1927 (Monday)

- The United Kingdom dispatched 16,000 servicemen to defend the British concession in ShanghaiShanghaiShanghai is the largest city by population in China and the largest city proper in the world. It is one of the four province-level municipalities in the People's Republic of China, with a total population of over 23 million as of 2010...

. Commanded by Major General John Duncan, the Shanghai Defense Force consisted of 12,000 men from the 13th and 14th British infantry brigades, and the 20th Indian Infantry, to join 3,000 naval ratings and 1,000 marines.

January 25, 1927 (Tuesday)

- Amid fears that the Coolidge Administration would lead the United States into war with MexicoMexicoThe United Mexican States , commonly known as Mexico , is a federal constitutional republic in North America. It is bordered on the north by the United States; on the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; on the southeast by Guatemala, Belize, and the Caribbean Sea; and on the east by the Gulf of...

, the U.S. Senate voted 79–0 to ask President Coolidge to seek arbitration of disputes over oil rights. - The merger of the Remington Typewriter Company and Rand-Kardex Bureau, Inc. (created from the merger of two business recordkeeping systesm) formed Remington RandRemington RandRemington Rand was an early American business machines manufacturer, best known originally as a typewriter manufacturer and in a later incarnation as the manufacturer of the UNIVAC line of mainframe computers but with antecedents in Remington Arms in the early nineteenth century. For a time, the...

, which would make the UNIVACUNIVACUNIVAC is the name of a business unit and division of the Remington Rand company formed by the 1950 purchase of the Eckert-Mauchly Computer Corporation, founded four years earlier by ENIAC inventors J. Presper Eckert and John Mauchly, and the associated line of computers which continues to this day...

, the world's first business computer. Through further mergers, the company became Sperry Rand (1955), and UnisysUnisysUnisys Corporation , headquartered in Blue Bell, Pennsylvania, United States, and incorporated in Delaware, is a long established business whose core products now involves computing and networking.-History:...

(1986). - J. Frank NorrisJ. Frank NorrisJohn Franklyn Norris was a flamboyant Baptist preacher, one of the most controversial figures in the history of fundamentalism.-Biography:...

, popular Southern Baptist leader, was acquitted of murder charges arisng from the July 17, 1926, death of wholesale lumberman Dexter B. Chipps - At OsloOsloOslo is a municipality, as well as the capital and most populous city in Norway. As a municipality , it was established on 1 January 1838. Founded around 1048 by King Harald III of Norway, the city was largely destroyed by fire in 1624. The city was moved under the reign of Denmark–Norway's King...

, the Storthing voted 112-33 to reject a proposal for complete disarmament of Norway. A bill to reorganize the army and navy was approved as an alternative. - Born: Antonio Carlos JobimAntônio Carlos JobimAntônio Carlos Brasileiro de Almeida Jobim , also known as Tom Jobim , was a Brazilian songwriter, composer, arranger, singer, and pianist/guitarist. He was a primary force behind the creation of the bossa nova style, and his songs have been performed by many singers and instrumentalists within...

, Brazilian composer credited with popularizing the bossa novaBossa novaBossa nova is a style of Brazilian music. Bossa nova acquired a large following in the 1960s, initially consisting of young musicians and college students...

style, in Rio de JaneiroRio de JaneiroRio de Janeiro , commonly referred to simply as Rio, is the capital city of the State of Rio de Janeiro, the second largest city of Brazil, and the third largest metropolitan area and agglomeration in South America, boasting approximately 6.3 million people within the city proper, making it the 6th...

(d. 1994)

January 26, 1927 (Wednesday)

- The American College of Osteopathic Surgeons (ACOS), a non-profit organization to promote osteopathic medicine in the United States was incorporated in ChicagoChicagoChicago is the largest city in the US state of Illinois. With nearly 2.7 million residents, it is the most populous city in the Midwestern United States and the third most populous in the US, after New York City and Los Angeles...

. - In Bannock County, IdahoBannock County, IdahoBannock County is a county located in the southeastern part of the U.S. state of Idaho. It was established in 1893 and named after the local Bannock tribe. It is part of the Pocatello, Idaho Metropolitan Statistical Area, which encompasses all of Bannock and Power counties. As of the 2000 Census...

a basketball game at the town of Turner, ended in tragedy when an explosion toppled the walls at the recreation hall of the Mormon chapel. Seven people were killed and 20 others seriously injured. The lights had failed and a person lit a match, triggering a gas explosion. - Born: José Azcona del HoyoJosé Azcona del HoyoJosé Simón Azcona del Hoyo was President of Honduras from 27 January 1986 to 27 January 1990 for the Liberal Party of Honduras . He was born in La Ceiba in Honduras.-Career:...

, President of HondurasPresident of HondurasThis page lists the Presidents of Honduras.Colonial Honduras declared its independence from Spain on 15 September 1821. From 5 January 1822 to 1 July 1823, Honduras was part of the First Mexican Empire of Agustín de Iturbide....

1986-1990, in La CeibaLa CeibaLa Ceiba is a port city on the northern coast of Honduras in Central America. It is located on the southern edge of the Caribbean, forming part of the south eastern boundary of the Gulf of Honduras...

(d. 2005) - Died: Lyman J. GageLyman J. GageLyman Judson Gage was an American financier and Presidential Cabinet officer.He was born at DeRuyter, New York, educated at an academy at Rome, New York, and at the age of 17 he became a bank clerk...

, 91, American financier and former U.S. Secretary of the Treasury

January 27, 1927 (Thursday)

- United Independent Broadcasters, Inc., was incorporated as a network of 16 radio stations. On September 18, 1927, United would be acquired by William S. PaleyWilliam S. PaleyWilliam S. Paley was the chief executive who built Columbia Broadcasting System from a small radio network into one of the foremost radio and television network operations in the United States.-Early life:...

and renamed the Columbia Broadcasting System, providing CBS Radio, and later the CBS Television Network. - A year after proclaiming himself King of the HejazHejazal-Hejaz, also Hijaz is a region in the west of present-day Saudi Arabia. Defined primarily by its western border on the Red Sea, it extends from Haql on the Gulf of Aqaba to Jizan. Its main city is Jeddah, but it is probably better known for the Islamic holy cities of Mecca and Medina...

, Arabian sultan Ibn SaudIbn Saud of Saudi ArabiaKing Abdul-Aziz of Saudi Arabia was the first monarch of the Third Saudi State known as Saudi Arabia. He was commonly referred to as Ibn Saud....

proclaimed himself as King of NajdNajdNajd or Nejd , literally Highland, is the central region of the Arabian Peninsula.-Boundaries :The Arabic word nejd literally means "upland" and was once applied to a variety of regions within the Arabian Peninsula...

as well. The independence of the Kingdom of Hejaz and Nejd was recognized on May 20, 1927, and renamed as the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in 1932. - Ty CobbTy CobbTyrus Raymond "Ty" Cobb , nicknamed "The Georgia Peach," was an American Major League Baseball outfielder. He was born in Narrows, Georgia...

and Tris SpeakerTris SpeakerTristram E. Speaker , nicknamed "Spoke" and "The Grey Eagle", was an American baseball player. Considered one of the best offensive and defensive center fielders in the history of Major League Baseball, he compiled a career batting average of .345 , and still holds the record of 792 career doubles...

, two of the greatest outfielders in American baseball history, were both exonerated of charges of wrongdoing by Commissioner Landis. Both had been accused, by Dutch LeonardDutch Leonard (left-handed pitcher)Hubert Benjamin "Dutch" Leonard, was an American left-handed pitcher in Major League Baseball who had an 11-year career from 1913–1921, 1924-1925. He played for the Boston Red Sox and Detroit Tigers, and holds the major league modern-era record for the lowest single-season ERA of all time — 0.96...

, of conspiracy to throw a game in 1919. Cobb was elected to baseball's Hall of Fame in its first year (1936), and Speaker in its second.

January 28, 1927 (Friday)

- A hurricane swept across the British IslesBritish IslesThe British Isles are a group of islands off the northwest coast of continental Europe that include the islands of Great Britain and Ireland and over six thousand smaller isles. There are two sovereign states located on the islands: the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and...

, killing twenty people and injuring hundreds. Nineteen of the dead were in Scotland, including eight in GlasgowGlasgowGlasgow is the largest city in Scotland and third most populous in the United Kingdom. The city is situated on the River Clyde in the country's west central lowlands...

, and another person was killed in Ireland. The storm moved on a line from Land's End in England, to John O'Groats in Scotland. - Born: Hiroshi Teshigahara, Japanese director, in ChiyodaChiyoda, Tokyois one of the 23 special wards in central Tokyo, Japan. In English, it is called Chiyoda ward. As of October 2007, the ward has an estimated population of 45,543 and a population density of 3,912 people per km², making it by far the least populated of the special wards...

(d. 2001)

January 29, 1927 (Saturday)

- In Schenectady, New YorkSchenectady, New YorkSchenectady is a city in Schenectady County, New York, United States, of which it is the county seat. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 66,135...

, the General ElectricGeneral ElectricGeneral Electric Company , or GE, is an American multinational conglomerate corporation incorporated in Schenectady, New York and headquartered in Fairfield, Connecticut, United States...

Company demonstrated its own sound-on-film process, the first to synchronize recorded sights and sounds on a single strip of film. The product of six years research opened a new era in movies, taking the world from silent films to the "talkies". - Born: Lewis UrryLewis UrryLewis Frederick Urry, , was a Canadian chemical engineer and inventor. He invented both the alkaline battery and lithium battery while working for the Eveready Battery company....

, Canadian engineer who invented the alkaline batteryAlkaline batteryAlkaline batteries are a type of primary batteries dependent upon the reaction between zinc and manganese dioxide . A rechargeable alkaline battery allows reuse of specially designed cells....

and the lithium batteryLithium batteryLithium batteries are disposable batteries that have lithium metal or lithium compounds as an anode. Depending on the design and chemical compounds used, lithium cells can produce voltages from 1.5 V to about 3.7 V, over twice the voltage of an ordinary zinc–carbon battery or alkaline battery...

, in Pontypool, ON (d. 2004); and Edward AbbeyEdward AbbeyEdward Paul Abbey was an American author and essayist noted for his advocacy of environmental issues, criticism of public land policies, and anarchist political views. His best-known works include the novel The Monkey Wrench Gang, which has been cited as an inspiration by radical environmental...

, American environmentalist, in Indiana, PA (d. 1989)

January 30, 1927 (Sunday)

- July Revolt of 1927July Revolt of 1927During the Austrian July Revolt of 1927 Austrian police forces killed 84 protesters, while four policemen died. More than 600 people were injured....

: At the AustriaAustriaAustria , officially the Republic of Austria , is a landlocked country of roughly 8.4 million people in Central Europe. It is bordered by the Czech Republic and Germany to the north, Slovakia and Hungary to the east, Slovenia and Italy to the south, and Switzerland and Liechtenstein to the...

n village of SchattendorfSchattendorfSchattendorf is a town in the district of Mattersburg in Burgenland in Austria with 2394 residents .The nature preserve Rosalia-Kogelberg lies within the district.- History :...

, members of the right-wing veterans' organization "Frontkampfer Vereinigung" fired on members of the leftist organization Schutzbund, killing one of them and seriously wounding five others. An 8-year old bystander was killed by the gunfire. When a jury acquitted the three Frontkampfer three months later, 84 protestors were killed by the Austrian police. - Born: Olof PalmeOlof PalmeSven Olof Joachim Palme was a Swedish politician. A long-time protegé of Prime Minister Tage Erlander, Palme led the Swedish Social Democratic Party from 1969 to his assassination, and was a two-term Prime Minister of Sweden, heading a Privy Council Government from 1969 to 1976 and a cabinet...

, Prime Minister of SwedenPrime Minister of SwedenThe Prime Minister is the head of government in the Kingdom of Sweden. Before the creation of the office of a Prime Minister in 1876, Sweden did not have a head of government separate from its head of state, namely the King, in whom the executive authority was vested...

1969–76 and 1982–86, in Östermalm (assassinated 1986)

January 31, 1927 (Monday)

- After seven years, the Inter-Allied Military Commission, which had overseen the occupation of Germany since the end of World War I, closed its headquarters in BerlinBerlinBerlin is the capital city of Germany and is one of the 16 states of Germany. With a population of 3.45 million people, Berlin is Germany's largest city. It is the second most populous city proper and the seventh most populous urban area in the European Union...

after France's Marshal Ferdinand FochFerdinand FochFerdinand Foch , GCB, OM, DSO was a French soldier, war hero, military theorist, and writer credited with possessing "the most original and subtle mind in the French army" in the early 20th century. He served as general in the French army during World War I and was made Marshal of France in its...

declared that Germany's obligations under the Treaty of VersaillesTreaty of VersaillesThe Treaty of Versailles was one of the peace treaties at the end of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1919, exactly five years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The other Central Powers on the German side of...

had been completed.; - Mae WestMae WestMae West was an American actress, playwright, screenwriter and sex symbol whose entertainment career spanned seven decades....

's play The Drag, the first theatrical production to address homosexuality, had its world premiere in Bridgeport, ConnecticutBridgeport, ConnecticutBridgeport is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Connecticut. Located in Fairfield County, the city had an estimated population of 144,229 at the 2010 United States Census and is the core of the Greater Bridgeport area...

. West hired 40 gay men to the cast. Although profitable, the play was banned by police in Bayonne, New JerseyBayonne, New JerseyBayonne is a city in Hudson County, New Jersey, United States. Located in the Gateway Region, Bayonne is a peninsula that is situated between Newark Bay to the west, the Kill van Kull to the south, and New York Bay to the east...

, and was unable to find a theatre in New York City. - Died: Sybil BauerSybil BauerSybil Bauer was an American swimmer.Bauer attended Schurz High School in Chicago, Illinois and Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. From 1921 to 1926, she set twenty-three world records in women's swimming, mostly in the backstroke...

, 23, American swimmer who broke 23 women's world records, and (in 1922), the men's world record for the 440 backstroke. Bauer, who didn't learn to swim until she was 15, had been engaged to marry Ed SullivanEd SullivanEdward Vincent "Ed" Sullivan was an American entertainment writer and television host, best known as the presenter of the TV variety show The Ed Sullivan Show. The show was broadcast from 1948 to 1971 , which made it one of the longest-running variety shows in U.S...

but died of cancer.