September 1927

Encyclopedia

January

- February

- March

- April

- May

- June

- July

- August

- September - October

- November

- December

The following events occurred in September 1927:

The following events occurred in September 1927:

a.jpg)

January 1927

January – February – March – April – May – June – July – August – September – October – November – DecemberThe following events occurred in January 1927.-January 1, 1927 :...

- February

February 1927

The following events occurred in February, 1927.January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - December-February 1, 1927 :*In its third year of conferring B.A...

- March

March 1927

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in March 1927-March 1, 1927 :...

- April

April 1927

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in April 1927:-April 1, 1927 :...

- May

May 1927

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in May 1927.-May 1, 1927 :...

- June

June 1927

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in June 1927.-June 1, 1927 :...

- July

July 1927

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in July 1927:-July 1, 1927 :...

- August

August 1927

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in August 1927:-August 1, 1927 :...

- September - October

October 1927

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in October 1927:-October 1, 1927 :...

- November

November 1927

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in November 1927:-November 1, 1927 :...

- December

December 1927

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October 1927 - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in December 1927:-December 1, 1927:...

September 1, 1927 (Thursday)

- National Air TransportNational Air TransportNational Air Transport was a large airline. In 1930 it was bought by Boeing. The Air Mail Act of 1934 prohibited airlines and manufacturers from being under the same corporate umbrella, so Boeing split into 3 smaller companies, one of which is United Airlines, and it is this that included what had...

, a predecessor of United AirlinesUnited AirlinesUnited Air Lines, Inc., is the world's largest airline with 86,852 employees United Air Lines, Inc., is the world's largest airline with 86,852 employees United Air Lines, Inc., is the world's largest airline with 86,852 employees (which includes the entire holding company United Continental...

, began the first air express delivery service, flying from Chicago to New York with "newsreels, machinery parts, adverttising copy, trade journals, candy and Paris garters", Hadley Field near New Brunswick, NJ, to Chicago - Born: Lloyd Bucher, Captain of the USS Pueblo, in Pocatello, IdahoPocatello, IdahoPocatello is the county seat and largest city of Bannock County, with a small portion on the Fort Hall Indian Reservation in neighboring Power County, in the southeastern part of the U.S. state of Idaho. It is the principal city of the Pocatello metropolitan area, which encompasses all of Bannock...

(d. 2004) - Died: Charles CoghlanCharles Patrick John CoghlanSir Charles Patrick John Coghlan was the first Premier of Southern Rhodesia and held office from October 1, 1923 until his death on August 28, 1927....

, 64, Prime Minister of Southern Rhodesia since 1923; he was succeeded by Howard Unwin MoffatHoward Unwin MoffatHoward Unwin Moffat served as second premier of Southern Rhodesia, from 1927 to 1933. Born in the Kuruman mission station in Bechuanaland , Moffat was the son of the missionary John Smith Moffat and grandson of the missionary Robert Moffat, who was the friend of King Mzilikazi and the...

; Amelia BinghamAmelia BinghamAmelia Swilley Kingham' was an Australian dancer from Hicksville, Ohio. Her Broadway career extended from ....

, 58, American stage actress; - Died: Elizabeth Sullivan Moffat Geddes, one-time wealthy society matron, divorced from William H. Moffat and Charles Walter Geddes; at a grocery store where she was working as a clerk

September 2, 1927 (Friday)

- At least eleven people were killed in the explosion of a fireworks factory in San Martín, Buenos AiresSan Martín, Buenos AiresCiudad del Libertador General Don José de San Martín, more commonly known as San Martín is the head city of the General San Martín Partido in the Gran Buenos Aires metropolitan area.-Geography:...

, ArgentinaArgentinaArgentina , officially the Argentine Republic , is the second largest country in South America by land area, after Brazil. It is constituted as a federation of 23 provinces and an autonomous city, Buenos Aires...

. - Augusto César SandinoAugusto César SandinoAugusto Nicolás Calderón Sandino was a Nicaraguan revolutionary and leader of a rebellion against the U.S. military occupation of Nicaragua between 1927 and 1933...

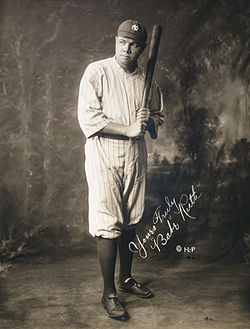

, Nicaraguan rebel leader, assembled his soldiers outside his remote fortress at El Chipote, and gathered villagers from the surrounding area to present the new charter for his Army for the Defense of National Sovereignty. Hundreds of people signed a statement of commitment to the Sandinista manifesto. Many who were illiterate signed with their thumbprints. - Babe RuthBabe RuthGeorge Herman Ruth, Jr. , best known as "Babe" Ruth and nicknamed "the Bambino" and "the Sultan of Swat", was an American Major League baseball player from 1914–1935...

of the New York Yankees hit the 400th home run of his career, off of Philadelphia A's pitcher Rube WalbergRube WalbergGeorge Elvin Walberg was a starting pitcher in Major League Baseball who played from through for the New York Giants , Philadelphia Athletics and Boston Red Sox . Walberg batted and threw left-handed...

, becoming the first baseball player to do so.

September 3, 1927 (Saturday)

- In Youngstown, OhioYoungstown, OhioYoungstown is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Mahoning County; it also extends into Trumbull County. The municipality is situated on the Mahoning River, approximately southeast of Cleveland and northwest of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania...

, 43 year old Tony De Capua came home from work, picked up a gun, and went on a shooting spree, killing his wife, his four daughters and his two grandchildren at his home at 443 Marion Avenue, then killed a neighbor. DeCapua shot and wounded his daughter-in-law, a passerby, and a city policeman, who returned fire and then overpowered the killer. DeCapua was later ruled incompetent to stand trial and sent to the Ohio Hospital for the Criminally Insane in LimaLima, OhioLima is a city in and the county seat of Allen County, Ohio, United States. The municipality is located in northwestern Ohio along Interstate 75 approximately north of Dayton and south-southwest of Toledo....

. - Hale WoodruffHale WoodruffHale Aspacio Woodruff was an African American artist known for his murals, paintings, and prints. One example of his work, the three-panel Amistad Mutiny murals , can be found at Talladega College in Talladega County, Alabama...

departed from New York for two years of study in France. After his return, he became one of the foremost African-American painters. - Born: John HammanJohn HammanBrother John Charles Hamman S.M. was a Catholic Marianist Brother and professional close-up magician. The tricks he invented are still an integral part of many close-up magician's repertoire....

, American magician, in St. Louis (d. 2000)

September 4, 1927 (Sunday)

- Twenty-two people were killed and more than 100 injured in the 1927 Nagpur riots1927 Nagpur riotsThe Nagpur riots of 1927 were part of series of riots taking place across various cities in British India during the 1920s. Nagpur was then the capital of Central Provinces and Berar state of British India which covered most of the central India. The riots occurred on September 4, 1927. It was the...

. - Born: John McCarthyJohn McCarthy (computer scientist)John McCarthy was an American computer scientist and cognitive scientist. He coined the term "artificial intelligence" , invented the Lisp programming language and was highly influential in the early development of AI.McCarthy also influenced other areas of computing such as time sharing systems...

, American computer scientist and 1971 Turin award winner for work in Artificial Intelligence; in Boston; and Ferenc SántaFerenc SántaFerenc Sánta was a Hungarian novelist and film screenwriter. He was awarded the József Attila Prize in 1956 and 1964, and the prestigious Kossuth Prize in 1973.-Selected works:*Sokan voltunk, 1954...

, Hungarian novelist, in BraşovBrasovBrașov is a city in Romania and the capital of Brașov County.According to the last Romanian census, from 2002, there were 284,596 people living within the city of Brașov, making it the 8th most populated city in Romania....

, RomaniaRomaniaRomania is a country located at the crossroads of Central and Southeastern Europe, on the Lower Danube, within and outside the Carpathian arch, bordering on the Black Sea...

(d. 2008)

September 5, 1927 (Monday)

- Universal Studios introduced the first completely animated Walt Disney film short, with Oswald the Lucky RabbitOswald the Lucky RabbitOswald the Lucky Rabbit is an anthropomorphic rabbit and animated cartoon character created by Ub Iwerks and Walt Disney for films distributed by Universal Pictures in the 1920s and 1930s...

appearing in Trolley Troubles. Oswald was later superseded by the more popular Mickey MouseMickey MouseMickey Mouse is a cartoon character created in 1928 by Walt Disney and Ub Iwerks at The Walt Disney Studio. Mickey is an anthropomorphic black mouse and typically wears red shorts, large yellow shoes, and white gloves...

. - Bob HopeBob HopeBob Hope, KBE, KCSG, KSS was a British-born American comedian and actor who appeared in vaudeville, on Broadway, and in radio, television and movies. He was also noted for his work with the US Armed Forces and his numerous USO shows entertaining American military personnel...

, 24, made his first appearance on Broadway, in The Sidewalks of New York, as a chorus boy, cast with his vaudeville partner George Byrne. - Born: Paul VolckerPaul VolckerPaul Adolph Volcker, Jr. is an American economist. He was the Chairman of the Federal Reserve under United States Presidents Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan from August 1979 to August 1987. He is widely credited with ending the high levels of inflation seen in the United States in the 1970s and...

, American economist, Chariman of the Federal Reserve Board 1979-1987; in Cape May, New JerseyCape May, New JerseyCape May is a city at the southern tip of Cape May Peninsula in Cape May County, New Jersey, where the Delaware Bay meets the Atlantic Ocean and is one of the country's oldest vacation resort destinations. It is part of the Ocean City Metropolitan Statistical Area. As of the 2010 United States... - Died: Marcus LoewMarcus LoewMarcus Loew was an American business magnate and a pioneer of the motion picture industry who formed Loews Theatres and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer .-Biography:...

, 57, founder of the Loews Theatres chain of cinemas - Died: Wayne WheelerWayne WheelerWayne Bidwell Wheeler was an American attorney and prohibitionist. Using deft political pressure and what might today be called a litmus test, he was able to influence many governments, and eventually the U.S. government, to prohibit alcohol.Wheeler was born in Brookfield, Ohio, to Mary Ursula...

, 57, American temperance movement leader for the Anti-Saloon League

September 6, 1927 (Tuesday)

- Two-hundred eighty people drowned when a ferryboat capsized in the Yellow SeaYellow SeaThe Yellow Sea is the name given to the northern part of the East China Sea, which is a marginal sea of the Pacific Ocean. It is located between mainland China and the Korean Peninsula. Its name comes from the sand particles from Gobi Desert sand storms that turn the surface of the water golden...

near Kaishu, Kokaido province (now HaejuHaejuHaeju is a city located in South Hwanghae Province near Haeju Bay in North Korea. It is the administrative centre of South Hwanghae Province. As of 2000, the population of the city is estimated to be 236,000. At the beginning of 20th century, it became a strategic port in Sino-Korean trade...

, Hwanghaenam-do province of North KoreaNorth KoreaThe Democratic People’s Republic of Korea , , is a country in East Asia, occupying the northern half of the Korean Peninsula. Its capital and largest city is Pyongyang. The Korean Demilitarized Zone serves as the buffer zone between North Korea and South Korea...

)

September 7, 1927 (Wednesday)

- At his laboratory at 202 Green Street in San Francisco, Philo T. Farnsworth demonstrated the first completely electronic television system. Although mechanical televisionMechanical televisionMechanical television was a broadcast television system that used mechanical or electromechanical devices to capture and display video images. However, the images themselves were usually transmitted electronically and via radio waves...

, using a rotating disk, had been created earlier by John Logie BairdJohn Logie BairdJohn Logie Baird FRSE was a Scottish engineer and inventor of the world's first practical, publicly demonstrated television system, and also the world's first fully electronic colour television tube...

, the hardware limited the picture to 10 frames per second and a 30 line image. Farnsworth's system used a scanning electronic tube to convert an image into electromagnetic waves that were then transmitted from one room of his lab to a receiver in another, where the image was displayed. The first transmission was of a white line against a dark background. As the pane with line was moved in front of the scanner, the image on the screen moved as well. In a brief telegram to his fellow investors, George Everson wrote "The damned thing works!". - The University of Minas Gerais was founded in BrazilBrazilBrazil , officially the Federative Republic of Brazil , is the largest country in South America. It is the world's fifth largest country, both by geographical area and by population with over 192 million people...

. - Attempting a transatlantic crossing, the airplane Old Glory sent an S.O.S. before crashing into the Ocean with aviators Lloyd W. BertaudLloyd W. BertaudLloyd W. Bertaud was an American aviator. Bertaud was selected to be the copilot in the WB-2 Columbia attempting the transatlantic crossing for the Orteig Prize in 1927. Aircraft owner Charles Levine wanted to fly in his place, and a injunction by Bertaud against Levine prevented the flight...

, James D. Hill and Philip Payne on board. The liner Transylvania picked up the signal and a search of the general area began. The wreckage of the Old Glory was found on September 12, 600 miles northeast of Newfoundland, but the three fliers were never located.

September 8, 1927 (Thursday)

- The Cessna-Roos Aircraft CompanyCessnaThe Cessna Aircraft Company is an airplane manufacturing corporation headquartered in Wichita, Kansas, USA. Their main products are general aviation aircraft. Although they are the most well known for their small, piston-powered aircraft, they also produce business jets. The company is a subsidiary...

was incorporated by partners Clyde Cessna and Victor Roos. The company, which was renamed Cessna Aircraft Company on December 22, made small, well-manufactured, airplanes affordable - Japanese troops began their withdrawal from China's Shandong province, more than three months after troops begun the occupation of JinanJinanJinan is the capital of Shandong province in Eastern China. The area of present-day Jinan has played an important role in the history of the region from the earliest beginnings of civilisation and has evolved into a major national administrative, economic, and transportation hub...

. - Sir Thomas Lipton retired as Chariman of Lipton's, Ltd., the tea company that he had founded

- Died: Dr. Edward Wallace Lee, 68, surgeon who attended President William McKinley following the latter's 1901 assassination

September 9, 1927 (Friday)

- IndianaIndianaIndiana is a US state, admitted to the United States as the 19th on December 11, 1816. It is located in the Midwestern United States and Great Lakes Region. With 6,483,802 residents, the state is ranked 15th in population and 16th in population density. Indiana is ranked 38th in land area and is...

Governor Edward L. Jackson and IndianapolisIndianapolisIndianapolis is the capital of the U.S. state of Indiana, and the county seat of Marion County, Indiana. As of the 2010 United States Census, the city's population is 839,489. It is by far Indiana's largest city and, as of the 2010 U.S...

Mayor John L. Duvall, both members of the Ku Klux KlanKu Klux KlanKu Klux Klan, often abbreviated KKK and informally known as the Klan, is the name of three distinct past and present far-right organizations in the United States, which have advocated extremist reactionary currents such as white supremacy, white nationalism, and anti-immigration, historically...

were indicted, along with Indiana Klan leader George V. Coffin, Klan counsel Robert I. Marsh and several other members. Governor Jackson and the others were accused of conspiracy to commit a felony and attempting to bribe, arising out of the alleged intimidation of former Governor Warren T. McCrayWarren T. McCrayWarren Terry McCray was the 30th Governor of the U.S. state of Indiana from 1921 to 1924. He came into conflict with the growing influence of the Indiana Ku Klux Klan after vetoing legislation they supported...

, who had recently completed a term in a federal penetentiary. - The last federal delivery of air mail took place, as the Postmaster General completed transition of the service from government-owned airplanes to private contractors.

- Nicaraguan rebels, after regrouping under the command of Augusto Sandino, ambushed a group of U.S. Marines who were marching near the U.S. base at Las Flores.

- Gustav StresemannGustav Stresemannwas a German politician and statesman who served as Chancellor and Foreign Minister during the Weimar Republic. He was co-laureate of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1926.Stresemann's politics defy easy categorization...

, the Foreign Minister of Germany, pledged his nation's support for the outlawing of war at a meeting of the League of NationsLeague of NationsThe League of Nations was an intergovernmental organization founded as a result of the Paris Peace Conference that ended the First World War. It was the first permanent international organization whose principal mission was to maintain world peace...

in GenevaGenevaGeneva In the national languages of Switzerland the city is known as Genf , Ginevra and Genevra is the second-most-populous city in Switzerland and is the most populous city of Romandie, the French-speaking part of Switzerland...

.

September 10, 1927 (Saturday)

- Dr. Morris FishbeinMorris FishbeinMorris Fishbein M.D. was a physician and the editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association from 1924 to 1950. In 1961 he became the founding Editor of Medical World News, a magazine for doctors. In 1970 he endowed the Morris Fishbein Center...

, editor of the Journal of the American Medical AssociationJournal of the American Medical AssociationThe Journal of the American Medical Association is a weekly, peer-reviewed, medical journal, published by the American Medical Association. Beginning in July 2011, the editor in chief will be Howard C. Bauchner, vice chairman of pediatrics at Boston University’s School of Medicine, replacing ...

and Secretary of the AMA, spoke out against recent American obsession with losing weight, saying that the "diet craze" had been "the menace of an anemic nation". Dr. Fishbein proclaimed that "If the false gospel of unscientific dieting continued to prevail for a few generations, the United States would become a nation of undersized weaklings and anemics, lacking in both physical and mental force."

September 11, 1927 (Sunday)

- U.S. President Coolidge ended his three month vacation, returning to Washington, D.C. after having been in South Dakota since June 15June 1927January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in June 1927.-June 1, 1927 :...

. The Coolidge family moved back into the newly remodeled White HouseWhite HouseThe White House is the official residence and principal workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., the house was designed by Irish-born James Hoban, and built between 1792 and 1800 of white-painted Aquia sandstone in the Neoclassical...

for the first time since March 2March 1927January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in March 1927-March 1, 1927 :...

. - Born: Vernon CoreaVernon CoreaVernon Corea was a pioneer radio broadcaster with 45 years of public service broadcasting both in Sri Lanka and the UK. He joined Radio Ceylon, South Asia's oldest radio station, in 1956 and later the Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation...

, Sri Lankan broadcaster, in KuranaKuranaKurana is a village in the city of Negombo, close to Katunayake in the island of Sri Lanka. It is on the Katunayake-Colombo road and a few miles from the Bandaranaike International Airport. People live in Kurana are belong to various kinds of nationalities and religions.Vernon Corea's father,...

; and G. David SchineG. David SchineGerard David Schine, better known as G. David Schine or David Schine, was the wealthy heir to a hotel chain fortune who received national attention when he became a central figure in the Army-McCarthy Hearings of 1954 in his role as the chief consultant to the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on...

, American businessman and central figure in the Army-McCarthy HearingsArmy-McCarthy HearingsThe Army–McCarthy hearings were a series of hearings held by the United States Senate's Subcommittee on Investigations between April 1954 and June 1954. The hearings were held for the purpose of investigating conflicting accusations between the United States Army and Senator Joseph McCarthy...

(killed in plane crash, 1996)

September 12, 1927 (Monday)

- U.S. Secretary of State Frank B. KelloggFrank B. KelloggFrank Billings Kellogg was an American lawyer, politician and statesman who served in the U.S. Senate and as U.S. Secretary of State. He co-authored the Kellogg-Briand Pact, for which he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for 1929..- Biography :Kellogg was born in Potsdam, New York, and his family...

warned the League of NationsLeague of NationsThe League of Nations was an intergovernmental organization founded as a result of the Paris Peace Conference that ended the First World War. It was the first permanent international organization whose principal mission was to maintain world peace...

that the United States would not abide by any ruling of the World Court over ownership of the Canal Zone. "American sovereignty over the Panama Canal is complete," said Kellogg. Panama, a member of the League, had asked that the question of American ownership of the Zone be decided by that body. - Born: Pham Xuan An, South Vietnamese reporter for TIME Magazine who transmitted hundreds of classified documents to North Vietnam from 1952 to 1975; in Bien HoaBien HoaBiên Hòa is a city in Dong Nai province, Vietnam, about east of Ho Chi Minh City , to which Bien Hoa is linked by Vietnam Highway 1.- Demographics :In 1989 the estimated population was over 300,000. In 2005, the population wss 541,495...

(d. 2006)

September 13, 1927 (Tuesday)

- Triggered by an undersea earthquake, a ten foot high tsunamiTsunamiA tsunami is a series of water waves caused by the displacement of a large volume of a body of water, typically an ocean or a large lake...

killed over 1,000 people in the coastal town of NakamuraNakamura, KochiNakamura was a city located in Kōchi, Japan. The city was in the southwestern part of Kōchi and known for its shrine.On April 10, 2005 Nakamura was merged with the village of Nishitosa, from Hata District, to form the new city of Shimanto....

, and 270 on the island of KōjimaKōjimais a small island in the Sea of Hyūga off the shore of the city of Kushima in Miyazaki Prefecture, Japan. The island is approximately 13 km ESE and 20 km by road from the central built-up area of Kushima...

. On the other side of the Pacific OceanPacific OceanThe Pacific Ocean is the largest of the Earth's oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic in the north to the Southern Ocean in the south, bounded by Asia and Australia in the west, and the Americas in the east.At 165.2 million square kilometres in area, this largest division of the World...

, the quake sent waves that killed hundreds of people in Salina CruzSalina CruzSalina Cruz is a major seaport on the Pacific coast of the Mexican state of Oaxaca. It is the state's third-largest city and is municipal seat of the municipality of the same name.It is part of the Tehuantepec District in the west of the Istmo Region....

and ManzanilioManzanillo, ColimaThe name Manzanillo refers to the city as well as its surrounding municipality in the Mexican state of Colima. The city, located on the Pacific Ocean, contains Mexico's busiest port. Manzanillo was the third port created by the Spanish in the Pacific during the New Spain period...

. The tremors and waves in Japan coincided with a typhoon that had killed hundreds of people in the Kumamoto PrefectureKumamoto Prefectureis a prefecture of Japan located on Kyushu Island. The capital is the city of Kumamoto.- History :Historically the area was called Higo Province; and the province was renamed Kumamoto during the Meiji Restoration. The creation of prefectures was part of the abolition of the feudal system...

and the Nagasaki PrefectureNagasaki Prefectureis a prefecture of Japan located on the island of Kyūshū. The capital is the city of Nagasaki.- History :Nagasaki Prefecture was created by merging of the western half of the former province of Hizen with the island provinces of Tsushima and Iki...

. - Heinrich HimmlerHeinrich HimmlerHeinrich Luitpold Himmler was Reichsführer of the SS, a military commander, and a leading member of the Nazi Party. As Chief of the German Police and the Minister of the Interior from 1943, Himmler oversaw all internal and external police and security forces, including the Gestapo...

issued SS Order No. 1, setting out the culture for the elite Nazi unit, the SchutzstaffelSchutzstaffelThe Schutzstaffel |Sig runes]]) was a major paramilitary organization under Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party. Built upon the Nazi ideology, the SS under Heinrich Himmler's command was responsible for many of the crimes against humanity during World War II...

. Drawn from the SturmabteilungSturmabteilungThe Sturmabteilung functioned as a paramilitary organization of the National Socialist German Workers' Party . It played a key role in Adolf Hitler's rise to power in the 1920s and 1930s...

(SA) (literally the stormtroopers), the 200 member SS group was given its own distinctive uniform, and paraded for a full inspection between Party meetings. The SS members also reported to Himmler on any indiscretions by other members of the SA. - Gene AustinGene AustinGene Austin was an American singer and songwriter, one of the first "crooners". His 1920s compositions "When My Sugar Walks Down the Street" and "The Lonesome Road" became pop and jazz standards.-Career:...

recorded My Blue HeavenMy Blue Heaven (song)"My Blue Heaven" is a popular song written by Walter Donaldson with lyrics by George A. Whiting. It has become part of various fake book collections....

, which would become the best selling record in 1928.

September 14, 1927 (Wednesday)

- In NiceNiceNice is the fifth most populous city in France, after Paris, Marseille, Lyon and Toulouse, with a population of 348,721 within its administrative limits on a land area of . The urban area of Nice extends beyond the administrative city limits with a population of more than 955,000 on an area of...

, FranceFranceThe French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

, American celebrity Isadora DuncanIsadora DuncanIsadora Duncan was a dancer, considered by many to be the creator of modern dance. Born in the United States, she lived in Western Europe and the Soviet Union from the age of 22 until her death at age 50. In the United States she was popular only in New York, and only later in her life...

was killed in a freak accident while being chauffered in a car that she intended to purchase. The dancer was in a car on the Promenade Des Anginis, wearing a long scarfScarfA scarf is a piece of fabric worn around the neck, or near the head or around the waist for warmth, cleanliness, fashion or for religious reasons. They can come in a variety of different colours.-History:...

around her neck. As Benoit Falchetto began driving down the street, the cloth became entangled in the right front wheel, strangling Duncan, breaking her neck, and then hurling her out of the car. She was 50 years old. - Bob Jones UniversityBob Jones UniversityBob Jones University is a private, for-profit, non-denominational Protestant university in Greenville, South Carolina.The university was founded in 1927 by Bob Jones, Sr. , an evangelist and contemporary of Billy Sunday...

opened with a revival service, then began its first classes (as Bob Jones College). Founded by evangelist Bob Jones, Sr.Bob Jones, Sr.Robert Reynolds Jones, Sr. was an American evangelist, pioneer religious broadcaster and the founder and first president of Bob Jones University.-Early years:...

, the two year college began in College Point, FloridaCollege Point, FloridaCollege Point is located in Bay County, Florida and is now part of the city of Lynn Haven. The name, chosen by Mary Gaston Stollenwerck Jones, was the post office address of Bob Jones College built there in 1927. The college moved to Cleveland, Tennessee in 1933 and then to Greenville, South...

with 88 students and 9 faculty. In 1933, it moved to Cleveland, TennesseeCleveland, TennesseeCleveland is a city in Bradley County, Tennessee, United States. The population was 41,285 at the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Bradley County...

, and in 1947, to Greenville, South CarolinaGreenville, South Carolina-Law and government:The city of Greenville adopted the Council-Manager form of municipal government in 1976.-History:The area was part of the Cherokee Nation's protected grounds after the Treaty of 1763, which ended the French and Indian War. No White man was allowed to enter, though some families...

. - The town of Tustin, CaliforniaTustin, California-Top employers:According to the City's 2010 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, the top employers in the city are:-2010:The 2010 United States Census reported that Tustin had a population of 75,540. The population density was 6,816.7 people per square mile...

narrowly approved incorporation as a city by a vote of 138 to 100. By 2011, the city had a population of more than 75,000. - A Kiss From Mary PickfordA Kiss From Mary PickfordA Kiss From Mary Pickford is a comedy film made in the Soviet Union, directed by Sergei Komarov and co-written by Komarov and Vadim Shershenevich. The film, starring Igor Ilyinsky, is mostly known today because of a cameo by the popular film couple Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks...

, directed by Sergei Komarov, premiered in Moscow. Soviet comedian Igor IlyinskyIgor IlyinskyIgor Vladimirovich Ilyinsky was a famous Russian actor and notable silent film comedian.-Early years:Igor Ilyinsky was born on 24 July 1901 in Moscow.At the age of 16 he entered the Komissarzhevskaya Theatre Studio and in half a year already debuted on the professional stage in Kommisarzhevskaya...

appeared in the film with Douglas FairbanksDouglas FairbanksDouglas Fairbanks, Sr. was an American actor, screenwriter, director and producer. He was best known for his swashbuckling roles in silent films such as The Thief of Bagdad, Robin Hood, and The Mark of Zorro....

and Mary PickfordMary PickfordMary Pickford was a Canadian-born motion picture actress, co-founder of the film studio United Artists and one of the original 36 founders of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences...

, who had visited the USSR in 1926 and were unaware that they were being filmed, - Died: Hugo BallHugo BallHugo Ball was a German author, poet and one of the leading Dada artists.Hugo Ball was born in Pirmasens, Germany and was raised in a middle-class Catholic family. He studied sociology and philosophy at the universities of Munich and Heidelberg...

, 41, German poet; Sidney Rawson Wilson, English anesthesist; and Joseph M. Quigley, Rochester NY Chief of Police since 1909 and inventor of the "silent policeman" traffic signal.

September 15, 1927 (Thursday)

- Daniel R. Crissinger resigned as Chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, ten days after the Board had reduced the discount rateDiscount windowThe discount window is an instrument of monetary policy that allows eligible institutions to borrow money from the central bank, usually on a short-term basis, to meet temporary shortages of liquidity caused by internal or external disruptions...

for ChicagoChicagoChicago is the largest city in the US state of Illinois. With nearly 2.7 million residents, it is the most populous city in the Midwestern United States and the third most populous in the US, after New York City and Los Angeles...

banks from 4% to 3½%. After Board member Edmund Platt temporarily acted as the Governor of the Fed, Roy A. YoungRoy A. YoungRoy Archibald Young was a U.S. banker. Most significantly, he was chairman of the Federal Reserve Board between 1927 and 1930 during the presidencies of Calvin Coolidge and Herbert Hoover. During his tenure as chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, the 1929 Stock Market Crash occurred and the...

became the new chief on September 22. - William S. BrockWilliam S. BrockWilliam S. Brock, Sr. was an aviation pioneer. With Edward F. Schlee he made the eighth non-stop crossing of the Atlantic Ocean.-Biography:...

and Edward F. Schlee abandoned their quest to become the first persons to fly an airplane around the world. The pair had set off from Harbour Grace, Newfoundland on August 27 in the Pride of Detroit, and had gone halfway around the globe, landing in Japan at Omura, where their journey was halted by stormy weather. After friends and family convinced them that they risked death if they attempted to fly across the Pacific OceanPacific OceanThe Pacific Ocean is the largest of the Earth's oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic in the north to the Southern Ocean in the south, bounded by Asia and Australia in the west, and the Americas in the east.At 165.2 million square kilometres in area, this largest division of the World...

to Midway Island, Schlee and Brock made their final journey from Omura to Kasumigaura, then traveled back to the United States on a ship. - Born: Rudolf Anderson, Jr., the only person to be killed in the Cuban Missile CrisisCuban Missile CrisisThe Cuban Missile Crisis was a confrontation among the Soviet Union, Cuba and the United States in October 1962, during the Cold War...

, in Greenville, South CarolinaGreenville, South Carolina-Law and government:The city of Greenville adopted the Council-Manager form of municipal government in 1976.-History:The area was part of the Cherokee Nation's protected grounds after the Treaty of 1763, which ended the French and Indian War. No White man was allowed to enter, though some families...

. USAF Major Anderson was killed on October 27, 1962, when his U-2 was shot down by a Cuban surface-to-air missile

September 16, 1927 (Friday)

- The complementarity principleComplementarity (physics)In physics, complementarity is a basic principle of quantum theory proposed by Niels Bohr, closely identified with the Copenhagen interpretation, and refers to effects such as the wave–particle duality...

of quantum physics was introduced by Niels BohrNiels BohrNiels Henrik David Bohr was a Danish physicist who made foundational contributions to understanding atomic structure and quantum mechanics, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1922. Bohr mentored and collaborated with many of the top physicists of the century at his institute in...

at the International Congress of Physics in the Italian city of ComoComoComo is a city and comune in Lombardy, Italy.It is the administrative capital of the Province of Como....

, where Bohr delivered his paper The Quantum Postulate and the Recent Development of Atomic Theory. - Born: Peter FalkPeter FalkPeter Michael Falk was an American actor, best known for his role as Lieutenant Columbo in the television series Columbo...

, American actor best known for portraying the detective Lieutenant Colombo in the TV series ColumboColumboColumbo is an American crime fiction television film series, which starred Peter Falk as Lieutenant Columbo, a homicide detective with the Los Angeles Police Department. It was created by William Link and Richard Levinson. The show popularized the inverted detective story format...

(d.2011); and Sadako OgataSadako Ogata, is a Japanese academic, diplomat, author, administrator and professor emeritus at Sophia University.-Early life:Sadako Nakamura was born in 1927...

, United Nations High Commissioner for RefugeesUnited Nations High Commissioner for RefugeesThe Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees , also known as The UN Refugee Agency is a United Nations agency mandated to protect and support refugees at the request of a government or the UN itself and assists in their voluntary repatriation, local integration or resettlement to...

from 1991 to 2001, in TokyoTokyo, ; officially , is one of the 47 prefectures of Japan. Tokyo is the capital of Japan, the center of the Greater Tokyo Area, and the largest metropolitan area of Japan. It is the seat of the Japanese government and the Imperial Palace, and the home of the Japanese Imperial Family...

September 17, 1927 (Saturday)

- Seven people were killed and five injured in what was, at the time, the deadliest airplane crash in history. The Fokker F.VIIFokker F.VIIThe Fokker F.VII, also known as the Fokker Trimotor, was an airliner produced in the 1920s by the Dutch aircraft manufacturer Fokker, Fokker's American subsidiary Atlantic Aircraft Corporation, and other companies under licence....

operated by Reynolds' Airways had been taking 11 passengers up for a brief sightseeing excursion from Hadley Field near South Plainfield, New JerseySouth Plainfield, New JerseySouth Plainfield is a Borough in Middlesex County, New Jersey, United States. As of the 2010 United States Census, the borough population was 23,385....

, when the engine stalled at 500 feet and the plane crashed into an orchard. The record was broken on December 3, 1928, by the crash of a Brazilian plane that killed 14. - Born: George BlandaGeorge BlandaGeorge Frederick Blanda was a collegiate and professional football quarterback and placekicker...

, NFL quarterback, placekicker and Hall of Famer, in Youngwood, PennsylvaniaYoungwood, PennsylvaniaYoungwood is a borough in Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, United States. The population was 4,138 at the 2000 census. It was the hometown of the late George Blanda - former NFL quarterback and placekicker.-History:...

(d. 2010); and Theodore S. WeissTheodore S. WeissTheodore S. "Ted" Weiss was a Democratic member of the United States House of Representatives from New York....

, Hungarian-born lawyer who became a U.S. citizen at age 26, and served as a U.S. Congressman from 1977 until his death in 1992.

September 18, 1927 (Sunday)

- The Columbia Phonographic Broadcasting System (later known as CBSCBSCBS Broadcasting Inc. is a major US commercial broadcasting television network, which started as a radio network. The name is derived from the initials of the network's former name, Columbia Broadcasting System. The network is sometimes referred to as the "Eye Network" in reference to the shape of...

) was formed and went on the air with a network of 16 radio stationRadio stationRadio broadcasting is a one-way wireless transmission over radio waves intended to reach a wide audience. Stations can be linked in radio networks to broadcast a common radio format, either in broadcast syndication or simulcast or both...

s in 11 U.S. states. Going on the air at 2:00 pm from Newark with music from the Howard Barlow Orchestra, it was the third national network, after NBC's Red Network and Blue Network. At 3:00, Donald VoorheesDonald VoorheesDonald Voorhees was an American composer and conductor who received an Emmy Award nomination for "Individual Achievements in Music" for his work on the television series, The Bell Telephone Hour.-Career:Starting in 1926, Voorhees' orchestra recorded prolifically for Columbia,...

conducted dance music, and at 8:00 pm, Deems TaylorDeems TaylorJoseph Deems Taylor was a U.S. composer, music critic, and promoter of classical music.-Career:Taylor initially planned to become an architect; however, despite minimal musical training he soon took to music composition. The result was a series of works for orchestra and/or voices...

conducted the Metropolitan OperaMetropolitan OperaThe Metropolitan Opera is an opera company, located in New York City. Originally founded in 1880, the company gave its first performance on October 22, 1883. The company is operated by the non-profit Metropolitan Opera Association, with Peter Gelb as general manager...

presentation of The King's HenchmanThe King's HenchmanThe King's Henchman is an opera in three acts composed by Deems Taylor to an English language libretto by Edna St. Vincent Millay. It premiered on February 17, 1927 at the Metropolitan Opera in New York City in a performance conducted by Tullio Serafin...

. In addition to the 16 network stations, the program was syndicated to another 58. Initially, CPBS programming was limited to 8-10 pm on Monday, Wednesday and Friday, and 2-4 pm and 7-10 pm on Sundays. - The Tannenberg MemorialTannenberg MemorialThe Tannenberg Memorial commemorated fallen German soldiers of the second Battle of Tannenberg in 1914, which was named after the medieval Battle of Tannenberg...

was unveiled at a ceremony at the site of the German victory over Russia during World War One in the Battle of TannenbergBattle of TannenbergBattle of Tannenberg may refer to :* Battle of Grunwald , also known as the First Battle of Tannenberg* Battle of Tannenberg , also known as the Second Battle of Tannenberg...

, near the town of HohensteinOlsztynekOlsztynek is a town in Poland, in Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship, in Olsztyn County. It has 7,648 inhabitants .-History:The town was founded as Hohenstein by the Teutonic Order, which began to construct a castle in 1351 and granted Kulm law city rights in 1359.The Battle of Grunwald in 1410 took...

in East Prussia. Germany's President Paul Von HindenburgPaul von HindenburgPaul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg , known universally as Paul von Hindenburg was a Prussian-German field marshal, statesman, and politician, and served as the second President of Germany from 1925 to 1934....

told his audience that Germany had not been the aggressor during the First World War, saying "With pure hearts we came to the defense of the Fatherland!"

September 19, 1927 (Monday)

- The Trial of Mary DuganThe Trial of Mary DuganThe Trial of Mary Dugan is a play written by Bayard Veiller.The melodrama concerns a sensational courtroom trial of a showgirl accused of killing of her millionaire lover. Her defense attorney is her brother, Jimmy Dugan. It was first presented on Broadway in 1927, with Ann Harding in the title...

began a successful run on Broadway of 437 performances, at the National Theatre, with Ann HardingAnn HardingAnn Harding was an American theatre, motion picture, radio, and television actress.-Early years:Born Dorothy Walton Gatley at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas, to George G. Gatley and Elizabeth "Bessie" Crabb. The daughter of a career army officer, she traveled often during her early life...

in the title role and in 1928 in London. The play was made into a 1929 film starring Norma ShearerNorma ShearerEdith Norma Shearer was a Canadian-American actress. Shearer was one of the most popular actresses in North America from the mid-1920s through the 1930s...

, and remade in 1941. - The U.S. Marine garrison at TelpanecaTelpanecaTelpaneca is a municipality in the Madriz department of Nicaragua....

, near the Rio Coco, was the victim of a lightning attack by Sandinista forces. One Marine was killed in the fighting, and another died of his wounds later. - Born: Harold BrownHarold Brown (Secretary of Defense)Harold Brown , American scientist, was U.S. Secretary of Defense from 1977 to 1981 in the cabinet of President Jimmy Carter. He had previously served in the Lyndon Johnson administration as Director of Defense Research and Engineering and Secretary of the Air Force.While Secretary of Defense, he...

, American physicist who served as U.S. Secretary of Defense from 1977 to 1981; in New York City; and Steve Ross, CEO of Time-Warner from 1989 to 1992; as Steven Rechnitz in BrooklynBrooklynBrooklyn is the most populous of New York City's five boroughs, with nearly 2.6 million residents, and the second-largest in area. Since 1896, Brooklyn has had the same boundaries as Kings County, which is now the most populous county in New York State and the second-most densely populated...

(d. 1992) - Died: Michael Ancher, 78, Danish impressionist painter

September 20, 1927 (Tuesday)

- A fire at the Beauval Catholic Mission in Lac La Plonge, SaskatchewanLac La Plonge, SaskatchewanLac La Plonge is a hamlet in Saskatchewan. It is located on the north shore of Lac la Plonge, a glacial lake, within the Canadian Shield and the Boreal Forest....

, killed 19 children and a nun. - Born: Ed TempleEd TempleEdward Stanley Temple is a women's track and field pioneer and coach. Temple was Head Women's Track and Field Coach at Tennessee State University for 44 years and was Head Coach of the U.S...

, American pioneer in women's sports who developed the Tennessee State UniversityTennessee State UniversityTennessee State University is a land-grant university located in Nashville, Tennessee. TSU is the only state-funded historically black university in Tennessee.-History:...

women's track and field team members into Olympic athletes; in Harrisburg, PennsylvaniaHarrisburg, PennsylvaniaHarrisburg is the capital of Pennsylvania. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 49,528, making it the ninth largest city in Pennsylvania...

September 21, 1927 (Wednesday)

- The Canary IslandsCanary IslandsThe Canary Islands , also known as the Canaries , is a Spanish archipelago located just off the northwest coast of mainland Africa, 100 km west of the border between Morocco and the Western Sahara. The Canaries are a Spanish autonomous community and an outermost region of the European Union...

were formally incorporated into the Kingdom of Spain, with the two major islands, TenerifeTenerifeTenerife is the largest and most populous island of the seven Canary Islands, it is also the most populated island of Spain, with a land area of 2,034.38 km² and 906,854 inhabitants, 43% of the total population of the Canary Islands. About five million tourists visit Tenerife each year, the...

and Gran CanariaGran CanariaGran Canaria is the second most populous island of the Canary Islands, with a population of 838,397 which constitutes approximately 40% of the population of the archipelago...

being separate provinces. - Born: Edwin ArdenerEdwin ArdenerEdwin Ardener was a British social anthropologist and academic. He was also noted for his contributions to the study of history. Within anthropology, some of his most important contributions were to the study of gender, as in his 1975 work in which he described women as "muted" in social...

, British anthropologist and historian (d. 1987)

September 22, 1927 (Thursday)

a.jpg)

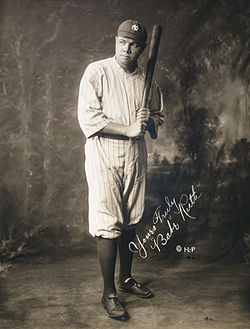

- Tunney v. Dempsey and "The Long Count"The Long Count FightThe Battle Of The Long Count was the boxing rematch between world Heavyweight champion Gene Tunney and former champion Jack Dempsey, held on September 22, 1927, at Soldier Field in Chicago...

: Former heavyweight boxing champion Jack DempseyJack DempseyWilliam Harrison "Jack" Dempsey was an American boxer who held the world heavyweight title from 1919 to 1926. Dempsey's aggressive style and exceptional punching power made him one of the most popular boxers in history. Many of his fights set financial and attendance records, including the first...

sought to regain the title that he had lost in 1926 to Gene TunneyGene TunneyJames Joseph "Gene" Tunney was the world heavyweight boxing champion from 1926-1928 who defeated Jack Dempsey twice, first in 1926 and then in 1927. Tunney's successful title defense against Dempsey is one of the most famous bouts in boxing history and is known as The Long Count Fight...

. The rematch took place at ChicagoChicagoChicago is the largest city in the US state of Illinois. With nearly 2.7 million residents, it is the most populous city in the Midwestern United States and the third most populous in the US, after New York City and Los Angeles...

's Soldier FieldSoldier FieldSoldier Field is located on Lake Shore Drive in Chicago, Illinois, United States, in the Near South Side. It is home to the NFL's Chicago Bears...

before a crowd of 104,943 people, while another ninety million people listened to Graham McNameeGraham McNameeGraham McNamee was a pioneering broadcaster in American radio, the medium's most recognized national personality in its first international decade....

's radio broadcast. Shortly after 10:00 pm Chicago time, the fight began; fifty seconds into the seventh round, Dempsey briefly knocked Tunney unconscious with six consecutive punches and was within ten seconds of regaining his crown. Dempsey made the mistake of not immediately following an order by referee Dave Barry to "Go to the farthest corner" away from Tunney, and Barry had to walk the challenger to the proper spot. Timekeeper Paul Beeler had already reached five when Barry raced over and restarted the count at one. Tunney regained consciousness as Beeler counted, and stood to his feet by the count of nine, after having been face down for 14, and possibly 18 seconds. Tunney returned to action, finished the ten round fight, and won by unanimous decisions of the judges. The gate set a record of $2,658,660 in sales, and Dempsey and Tunney split a prize of $1,540,445. - Born: Tommy LasordaTommy LasordaThomas Charles Lasorda is a former Major League baseball player and manager. marked his sixth decade in one capacity or another with the Brooklyn/Los Angeles Dodgers organization, the longest non-continuous tenure anyone has had with the team, edging Dodger broadcaster Vin Scully...

, manager of baseball's Los Angeles DodgersLos Angeles DodgersThe Los Angeles Dodgers are a professional baseball team based in Los Angeles, California. The Dodgers are members of Major League Baseball's National League West Division. Established in 1883, the team originated in Brooklyn, New York, where it was known by a number of nicknames before becoming...

from 1976 to 1996; in Norristown, PennsylvaniaNorristown, PennsylvaniaNorristown is a municipality in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, northwest of the city limits of Philadelphia, on the Schuylkill River. The population was 34,324 as of the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Montgomery County...

; and Kika de la GarzaKika de la GarzaEligio “Kika” de la Garza, II was the Democratic representative for the 15th congressional district of Texas from January 3, 1965, to January 3, 1997....

, U.S. Congressman (Texas) from 1965 to 1997, in Mercedes, TexasMercedes, TexasMercedes is a city in Hidalgo County, Texas, United States. The population was 15,570 at the 2010 census. It is part of the McAllen–Edinburg–Mission and Reynosa–McAllen metropolitan areas.-Geography:Mercedes is located at ....

September 23, 1927 (Friday)

- SunriseSunrise (film)Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans, also known as Sunrise, is a 1927 American silent film directed by German film director F. W. Murnau. The story was adapted by Carl Mayer from the short story "Die Reise nach Tilsit" by Hermann Sudermann.Sunrise won an Academy Award for Unique and Artistic Production...

, the first feature film to include a recorded soundtrack, premiered at the Times Square Theatre in New York City. Subtitled "A Song of Two Humans", the film was directed by F. W. Murnau, and used the Movietone sound systemMovietone sound systemThe Movietone sound system is a sound-on-film method of recording sound for motion pictures that guarantees synchronization between sound and picture. It achieves this by recording the sound as a variable-density optical track on the same strip of film that records the pictures...

for synchronized music and sound effects. Preceding the first "talkie" (The Jazz SingerThe Jazz Singer (1927 film)The Jazz Singer is a 1927 American musical film. The first feature-length motion picture with synchronized dialogue sequences, its release heralded the commercial ascendance of the "talkies" and the decline of the silent film era. Produced by Warner Bros. with its Vitaphone sound-on-disc system,...

), by two weeks, Sunrise did not include recorded dialogue and still used silent film intertitles. The film was preceded by a Fox Movietone newsreel "in which the figurantes were heard as well as seen", including a "message of friendship" from Italian dictator Benito MussoliniBenito MussoliniBenito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini was an Italian politician who led the National Fascist Party and is credited with being one of the key figures in the creation of Fascism....

, followed by "scenes of life in the Italian Army". - The film Berlin: Die Sinfonie der Großstadt (Berlin: Symphony of the Great City), directed by Walter RuttmannWalter RuttmannWalter Ruttmann was a German film director and along with Hans Richter and Viking Eggeling was an early German practitioner of experimental film....

, premiered in Berlin. - Died: Baron Avo Von Maltzan, Germany's ambassador to the United States, in a Lufthansa airlines flight crash that killed 5. Von Maltzan was flying from Berlin to Munich.

September 24, 1927 (Saturday)

- The Assembly of the League of NationsLeague of NationsThe League of Nations was an intergovernmental organization founded as a result of the Paris Peace Conference that ended the First World War. It was the first permanent international organization whose principal mission was to maintain world peace...

unanimously adopted the Declaration on Aggression, resolving that aggressive war was an international crime punishable by League sanctions.

September 25, 1927 (Sunday)

- All of the low lands (der Unterland) in the tiny principality of LiechtensteinLiechtensteinThe Principality of Liechtenstein is a doubly landlocked alpine country in Central Europe, bordered by Switzerland to the west and south and by Austria to the east. Its area is just over , and it has an estimated population of 35,000. Its capital is Vaduz. The biggest town is Schaan...

were flooded when the Rhine River overflowed its banks at SchaanSchaanSchaan is the largest municipality of Liechtenstein. It is located to the north of Vaduz, the capital, in the central part of the country. As of 2005 it has a population of making it the largest administrative district in Liechtenstein, and covers an area of 26.8 km², including mountains and...

, ruining most of the nation's farmers. Volunteers from around Europe helped in what was described later as "one of the first international relief operations in peacetime". - The process of electric borehole loggingWell loggingWell logging, also known as borehole logging is the practice of making a detailed record of the geologic formations penetrated by a borehole. The log may be based either on visual inspection of samples brought to the surface or on physical measurements made by instruments lowered into the hole...

, used to gather and make logs of data from wells as they were being drilled, was first used. The test, later widely used, was performed at the Pechelbronn oil field in Alsace, France, by Marcel and Conrad Schlumberger - Born: Sir Colin DavisColin DavisSir Colin Rex Davis, CH, CBE is an English conductor. His repertoire is broad, but among the composers with whom he is particularly associated are Mozart, Berlioz, Elgar, Sibelius, Stravinsky and Tippett....

, English conductor, in WeybridgeWeybridgeWeybridge is a town in the Elmbridge district of Surrey in South East England. It is bounded to the north by the River Thames at the mouth of the River Wey, from which it gets its name...

September 26, 1927 (Monday)

- The Geneva Convention on the Execution of Foreign Arbitral Awards was signed. It took effect on July 25, 1929 and remains in force, although it was superseded by a 1958 treaty signed in New York.

- The Administrative Tribunal of the League of Nations was established.

- Born: Robert CadeRobert CadeJames Robert Cade was an American physician, university professor, research scientist and inventor. Cade, a native of Texas, earned his undergraduate and medical degrees, and became a professor of medicine and nephrology at the University of Florida...

, American physician who led the research team that invented GatoradeGatoradeGatorade is a brand of sports-themed food and beverage products, built around its signature product: a line of sports drinks. Gatorade is currently manufactured by PepsiCo, distributed in over 80 countries...

; in San Antonio, TexasSan Antonio, TexasSan Antonio is the seventh-largest city in the United States of America and the second-largest city within the state of Texas, with a population of 1.33 million. Located in the American Southwest and the south–central part of Texas, the city serves as the seat of Bexar County. In 2011,...

(d. 2007); Romano MussoliniRomano MussoliniRomano Mussolini was the fourth and youngest son of Benito Mussolini, fascist dictator of Italy from 1922 to 1943...

, Italian-born jazz pianist who was the son of Italian dictator Benito Mussolini (d. 2006); and Homer LedfordHomer LedfordHomer C. Ledford was an instrument maker and bluegrass musician from Kentucky who specialized in making dulcimers....

, American instrument maker nicknamed "The Stradivarius of the DulcimerDulcimerDulcimer may refer to two types of musical instruments:* Appalachian dulcimer, a fretted, plucked musical instrument which is also referred to as a "mountain dulcimer", "lap dulcimer", "hog fiddle", "fretted dulcimer" or simply "dulcimer"...

"; inventor of the dulcitarDulcitarDulcitar is one of a great many names used to describe a necked lute instrument with diatonic fretting, based on the Appalachian dulcimer.Other names used for this instrument include:*Walkabout dulcimer *Strumstick...

; in Alpine, TennesseeAlpine, TennesseeAlpine is a small unincorporated community in Overton County, Tennessee, United States. It is served by the ZIP Code of 38543, for which the ZCTA had a population of 497 at the 2000 census....

(d. 2006)

September 27, 1927 (Tuesday)

- Leon TrotskyLeon TrotskyLeon Trotsky , born Lev Davidovich Bronshtein, was a Russian Marxist revolutionary and theorist, Soviet politician, and the founder and first leader of the Red Army....

was expelled from the CominternCominternThe Communist International, abbreviated as Comintern, also known as the Third International, was an international communist organization initiated in Moscow during March 1919...

, as his power continued to decline. He would be expelled from the Soviet Communist Party the following month. - I.G. Farben of Germany and Standard Oil of New Jersey entered a 25 year agreement providing the American oil company with access to German technology on crude oil hydrogenation.

- The discovery of a rich gold vein was made in the Gran Cordillera on the island of Luzon in the Philippines, by prospectors of the Benquet Consolidated Mining Company. By 1933, there were nearly 18,000 mining companies in the area, and by 1939, the Philippines was one of the world's leading gold producers.

- Groundbreaking took place for the George Washington BridgeGeorge Washington BridgeThe George Washington Bridge is a suspension bridge spanning the Hudson River, connecting the Washington Heights neighborhood in the borough of Manhattan in New York City to Fort Lee, Bergen County, New Jersey. Interstate 95 and U.S. Route 1/9 cross the river via the bridge. U.S...

on both sides of the Hudson RiverHudson RiverThe Hudson is a river that flows from north to south through eastern New York. The highest official source is at Lake Tear of the Clouds, on the slopes of Mount Marcy in the Adirondack Mountains. The river itself officially begins in Henderson Lake in Newcomb, New York...

, at ManhattanManhattanManhattan is the oldest and the most densely populated of the five boroughs of New York City. Located primarily on the island of Manhattan at the mouth of the Hudson River, the boundaries of the borough are identical to those of New York County, an original county of the state of New York...

and at Fort Lee, New JerseyFort Lee, New JerseyFort Lee is a borough in Bergen County, New Jersey, United States. As of the 2010 United States Census, the borough population was 35,345. Located atop the Hudson Palisades, the borough is the western terminus of the George Washington Bridge...

, followed by speeches given on the steamer DeWitt Clinton, which had anchored in the middle of the river. - Born: Steve StavroSteve StavroSteve Atanas Stavro, CM , born Manoli Stavroff Sholdas, was a Macedonian Canadian businessman, grocery store magnate, Thoroughbred racehorse owner/breeder, sports team owner, and a noted philanthropist....

, Canadian sports businessman, soccer league founder, and one-time owner of the NHL Toronto Maple Leafs and the NBA Toronto Raptors; as Manoli Stavroff Sholdas in Macedonia (d. 2006); W. S. MerwinW. S. MerwinWilliam Stanley Merwin is an American poet, credited with over 30 books of poetry, translation and prose. During the 1960s anti-war movement, Merwin's unique craft was thematically characterized by indirect, unpunctuated narration. In the 1980s and 1990s, Merwin's writing influence derived from...

, American poet, in New York City; Chrysostomos I of Cyprus, Archbishop of Cyprus from 1977 to 2006; "Red RodneyRed RodneyRobert Roland Chudnick , who performed by the stage name Red Rodney, was an American bop and hard bop trumpeter.-Biography:...

" (Robert Rodney Chudnick), American jazz musician, in Philadelphia; and A. Reza Arasteh, Iranian-born philosopher, in ShirazShirazShiraz may refer to:* Shiraz, Iran, a city in Iran* Shiraz County, an administrative subdivision of Iran* Vosketap, Armenia, formerly called ShirazPeople:* Hovhannes Shiraz, Armenian poet* Ara Shiraz, Armenian sculptor... - Died: Frank M. CantonFrank M. CantonJosiah Horner , better known as Frank M. Canton, was a famous American Old West lawman, gunslinger, cowboy and at one point in his life, an outlaw.-Early life:...

, former American outlaw

September 28, 1927 (Wednesday)

- Babe RuthBabe RuthGeorge Herman Ruth, Jr. , best known as "Babe" Ruth and nicknamed "the Bambino" and "the Sultan of Swat", was an American Major League baseball player from 1914–1935...

tied his record of 59 home runs hit in 1921, hitting his 58th and 59th in the Yankees' 15-0 win over the visiting Washington Senators, and their pitcher, Horace LisenbeeHorace LisenbeeHorace Milton "Hod" Lisenbee was a baseball pitcher whose career spanned over 28 years , although he only played eight seasons in the major leagues. Lisenbee was born on September 23, 1898, in Clarksville, Tennessee to John M. Lisenbee and Sarah Adiline Lisenbee, both of Clarksville, the second of...

.

September 29, 1927 (Thursday)

- Seventy-nine people were killed and 550 are injured when a tornado struck the western part of St. Louis, MissouriSt. Louis, MissouriSt. Louis is an independent city on the eastern border of Missouri, United States. With a population of 319,294, it was the 58th-largest U.S. city at the 2010 U.S. Census. The Greater St...

. The twister struck at 1:00 in the afternoon, tearing through buildings, including St. Louis Central High School, where five students were killed and 16 injured. - Born: Jean Baker Miller, American psychiatrist and pioneer; author of Toward a New Psychology of Women, in New York CityNew York CityNew York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

(d. 2006) - Died: Willem EinthovenWillem EinthovenWillem Einthoven was a Dutch doctor and physiologist. He invented the first practical electrocardiogram in 1903 and received the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1924 for it....

, 67, Dutch inventor of the electrocardiogramElectrocardiogramElectrocardiography is a transthoracic interpretation of the electrical activity of the heart over a period of time, as detected by electrodes attached to the outer surface of the skin and recorded by a device external to the body...

, winner of the Nobel Prize in 1924

September 30, 1927 (Friday)

- Babe RuthBabe RuthGeorge Herman Ruth, Jr. , best known as "Babe" Ruth and nicknamed "the Bambino" and "the Sultan of Swat", was an American Major League baseball player from 1914–1935...

broke his own record for most home runs in a season (59) by hitting his 60th home run, a record that would stand until 1961. The run came in the 8th inning of the penultimate game of the season. Pitcher Tom ZacharyTom ZacharyJonathan Thompson Walton Zachary was a pitcher who had a 19-year career that lasted from 1918 to 1936. He played for the Philadelphia A's, Washington Senators, St...

had thrown one ball and one strike, when Ruth hit the ball into the bleachers and gave the New York Yankees a 4-2 win over the Washington Senators - Born: Adhemar Ferreira da Silva, Brazilian athlete, twice holder of world record for the triple jumpTriple jumpThe triple jump is a track and field sport, similar to the long jump, but involving a “hop, bound and jump” routine, whereby the competitor runs down the track and performs a hop, a bound and then a jump into the sand pit.The triple jump has its origins in the Ancient Olympics and has been a...

in the 1950s, Olympic gold medalist in 1952 and 1956 (d. 2001)