December 1927

Encyclopedia

January

- February

- March

- April

- May

- June

- July

- August

- September

- October 1927

- November

- December

The following events occurred in December 1927:

January 1927

January – February – March – April – May – June – July – August – September – October – November – DecemberThe following events occurred in January 1927.-January 1, 1927 :...

- February

February 1927

The following events occurred in February, 1927.January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - December-February 1, 1927 :*In its third year of conferring B.A...

- March

March 1927

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in March 1927-March 1, 1927 :...

- April

April 1927

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in April 1927:-April 1, 1927 :...

- May

May 1927

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in May 1927.-May 1, 1927 :...

- June

June 1927

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in June 1927.-June 1, 1927 :...

- July

July 1927

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in July 1927:-July 1, 1927 :...

- August

August 1927

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in August 1927:-August 1, 1927 :...

- September

September 1927

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in September 1927:-September 1, 1927 :...

- October 1927

October 1927

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in October 1927:-October 1, 1927 :...

- November

November 1927

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in November 1927:-November 1, 1927 :...

- December

The following events occurred in December 1927:

December 1, 1927(Thursday)

- Chinese actress Soong May-lingSoong May-lingSoong May-ling or Soong Mei-ling, also known as Madame Chiang Kai-shek or Madame Chiang was a First Lady of the Republic of China , the wife of Generalissimo and President Chiang Kai-shek. She was a politician and painter...

married General Chiang Kai-shekChiang Kai-shekChiang Kai-shek was a political and military leader of 20th century China. He is known as Jiǎng Jièshí or Jiǎng Zhōngzhèng in Mandarin....

, and became known as Madame Chiang. After General Chiang became China's leader the following year, she was the First Lady for the next 48 years, until her husband's death in 1975. An Episcopal Christian wedding was conducted, in English, at Miss Soong's home, followed by a Chinese civil ceremony at the Majestic Hotel in ShanghaiShanghaiShanghai is the largest city by population in China and the largest city proper in the world. It is one of the four province-level municipalities in the People's Republic of China, with a total population of over 23 million as of 2010...

. Miss Soong's sister was the widow of China's first President, Sun Yat-senSun Yat-senSun Yat-sen was a Chinese doctor, revolutionary and political leader. As the foremost pioneer of Nationalist China, Sun is frequently referred to as the "Father of the Nation" , a view agreed upon by both the People's Republic of China and the Republic of China...

.

December 2, 1927 (Friday)

- Following 19 years of Ford Model TFord Model TThe Ford Model T is an automobile that was produced by Henry Ford's Ford Motor Company from September 1908 to May 1927...

production, the Ford Motor CompanyFord Motor CompanyFord Motor Company is an American multinational automaker based in Dearborn, Michigan, a suburb of Detroit. The automaker was founded by Henry Ford and incorporated on June 16, 1903. In addition to the Ford and Lincoln brands, Ford also owns a small stake in Mazda in Japan and Aston Martin in the UK...

unveiled the Model AFord Model A (1927)The Ford Model A of 1927–1931 was the second huge success for the Ford Motor Company, after its predecessor, the Model T. First produced on October 20, 1927, but not sold until December 2, it replaced the venerable Model T, which had been produced for 18 years...

as its new automobile. - FranceFranceThe French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

's Chamber of Deputies rejected a proposal to abolish the death penalty, by a margin of 376-145. France would finally abolish the death penalty on October 9, 1981October 1981January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in October 1981:-October 1, 1981 :...

. - Marcus GarveyMarcus GarveyMarcus Mosiah Garvey, Jr., ONH was a Jamaican publisher, journalist, entrepreneur, and orator who was a staunch proponent of the Black Nationalism and Pan-Africanism movements, to which end he founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League...

was deported from the United States, placed on the SS Saramacca at New Orleans and returned to his native Jamaica.

December 3, 1927 (Saturday)

- The first film of the Laurel and HardyLaurel and HardyLaurel and Hardy were one of the most popular and critically acclaimed comedy double acts of the early Classical Hollywood era of American cinema...

series of Hal RoachHal RoachHarold Eugene "Hal" Roach, Sr. was an American film and television producer and director, and from the 1910s to the 1990s.- Early life and career :Hal Roach was born in Elmira, New York...

comedies was released. Stan LaurelStan LaurelArthur Stanley "Stan" Jefferson , better known as Stan Laurel, was an English comic actor, writer and film director, famous as the first half of the comedy team Laurel and Hardy. His film acting career stretched between 1917 and 1951 and included a starring role in the Academy Award winning film...

and Oliver HardyOliver HardyOliver Hardy was an American comic actor famous as one half of Laurel and Hardy, the classic double act that began in the era of silent films and lasted nearly 30 years, from 1927 to 1955.-Early life:...

had appeared in the same films as early as 1918, but hadn't become a star team until October. The first "official" Laurel & Hardy film was a two-reel silent, Putting Pants on PhilipPutting Pants on PhilipPutting Pants On Philip is a landmark Hal Roach two-reel silent film from 1927. It was the first to bill Laurel and Hardy as a comedy duo, although the first film the two comedians were in together had been The Lucky Dog from 1921, and the first Hal Roach production they were both in was 45...

. - Born: Andy WilliamsAndy WilliamsHoward Andrew "Andy" Williams is an American singer who has recorded 18 Gold- and three Platinum-certified albums. He hosted The Andy Williams Show, a TV variety show, from 1962 to 1971, as well as numerous television specials, and owns his own theater, the Moon River Theatre in Branson, Missouri,...

, American singer, as Howard Andrew Williams in Wall Lake, IowaWall Lake, IowaWall Lake is a city in Sac County, Iowa, United States. The population was 841 at the 2000 census.-Geography:Wall Lake is located at .According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of , all of it land....

December 4, 1927 (Sunday)

- Duke EllingtonDuke EllingtonEdward Kennedy "Duke" Ellington was an American composer, pianist, and big band leader. Ellington wrote over 1,000 compositions...

and his orchestra opened at the Cotton ClubCotton ClubThe Cotton Club was a famous night club in Harlem, New York City that operated during Prohibition that included jazz music. While the club featured many of the greatest African American entertainers of the era, such as Fletcher Henderson, Duke Ellington, Adelaide Hall, Count Basie, Bessie Smith,...

in HarlemHarlemHarlem is a neighborhood in the New York City borough of Manhattan, which since the 1920s has been a major African-American residential, cultural and business center. Originally a Dutch village, formally organized in 1658, it is named after the city of Haarlem in the Netherlands...

, New York CityNew York CityNew York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

. Ellington proved so popular that he was featured at the Cotton Club for five years. In 1929, the CBS Radio Network began broadcasting a live show from the Club, taking the 28 year old jazz musician on his way to worldwide fame.

December 5, 1927 (Monday)

- The Illini of the University of IllinoisIllinois Fighting Illini footballThe Illinois Fighting Illini are a major college football program, representing the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. They compete in NCAA Division I-A and the Big Ten Conference.-Current staff:-All-time win/loss/tie record:*563-513-51...

were awarded the Rissler Cup after finishing first in the Dickinson SystemDickinson SystemThe Dickinson System was a mathematical point formula that awarded national championships in college football. Devised by University of Illinois economics professor Frank G...

ratings for college footballCollege footballCollege football refers to American football played by teams of student athletes fielded by American universities, colleges, and military academies, or Canadian football played by teams of student athletes fielded by Canadian universities...

teams, under a formula devised by a University of Illinois economics professor, Frank G. Dickenson. The Illini had a 7-0-1 record; second place was held by the University of Pittsburgh PanthersPittsburgh Panthers footballPittsburgh Panthers football is the intercollegiate football team of the University of Pittsburgh, often referred to as "Pitt", located in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Traditionally the most popular sport at the university, Pitt football has played at the highest level of American college football...

(8-0-1). For the nation's only bowl game, the Rose BowlRose BowlRose Bowl or Rosebowl may also refer to:* Rose Bowl Game, an annual American college football bowl game in Pasadena, California* Rose Bowl , a football stadium in Pasadena, California...

, Pitt was selected to play (7-2-1) Stanford University, whose teams were known at that time as the "Indians". - Born: Bhumibol AdulyadejBhumibol AdulyadejBhumibol Adulyadej is the current King of Thailand. He is known as Rama IX...

, officially Rama IX, King of Thailand since 1946, in Cambridge, MassachusettsCambridge, MassachusettsCambridge is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States, in the Greater Boston area. It was named in honor of the University of Cambridge in England, an important center of the Puritan theology embraced by the town's founders. Cambridge is home to two of the world's most prominent...

; W.D. Amaradeva, Sri Lankan singer and composer, in MoratuwaMoratuwaMoratuwa is a city on the southwestern coast of Sri Lanka, near Dehiwela-Mount Lavinia. It is situated on the Galle–Colombo main highway, 18 km south of the capital, Colombo. Moratuwa is surrounded on three sides by water, except in the north of the city, by the Indian Ocean on the west...

; and Oscar MiguezOscar MíguezÓscar Omar Miguez Antón was a Uruguayan footballer. He was part of the Uruguay team in the 1950 and 1954 World Cups, where he played as a striker, and is Uruguay's all-time record World Cup goalscorer with eight goals....

, Uruguayan footballer who helped that nation win the 1950 World Cup (d. 2006)

December 6, 1927 (Tuesday)

- On the day that they were scheduled to testify at a murder trial in Williamson, West VirginiaWilliamson, West VirginiaWilliamson is a city in Mingo County, West Virginia, USA, along the Tug Fork River. The population was 3,414 at the 2000 census. It is the county seat of Mingo County, and is the county's largest and most populous city. Williamson is home to Southern West Virginia Community and Technical College...

, six witnesses were killed when the lodging they were staying in caught fire. Flames blocked both stairways leading from the upper floor, and all of the victims were found in a room where they had fled to escape the smoke. - Colonel Juan Aberle and Major Alfaro Noguera attempted to stage a coup in El SalvadorEl SalvadorEl Salvador or simply Salvador is the smallest and the most densely populated country in Central America. The country's capital city and largest city is San Salvador; Santa Ana and San Miguel are also important cultural and commercial centers in the country and in all of Central America...

. They took control of the central police barracks in San SalvadorSan SalvadorThe city of San Salvador the capital and largest city of El Salvador, which has been designated a Gamma World City. Its complete name is La Ciudad de Gran San Salvador...

, but the badly planned putsch was quickly suppressed. - Born: Patsy Takemoto Mink, who in 1964 became the first female Asian-American to be elected to Congress; in Paia, HawaiiPaia, HawaiiPāia is a census-designated place in Maui County, Hawaii, on the northern coast of the island of Maui. The population was 2,499 at the 2000 census. Pāia is home to several restaurants, art galleries, surf shops and other tourist-oriented businesses. One business, Charley's, is frequented by...

(d. 2002)

December 7, 1927 (Wednesday)

- The 250 foot long Canadian freighter SS KamloopsSS KamloopsThe SS Kamloops was a lake freighter that was part of the fleet of Canada Steamship Lines from its launching in 1924 until it sank with all hands off Isle Royale in Lake Superior on or about 7 December 1927.-The canaller:...

, with a crew of 22, sank in Lake SuperiorLake SuperiorLake Superior is the largest of the five traditionally-demarcated Great Lakes of North America. It is bounded to the north by the Canadian province of Ontario and the U.S. state of Minnesota, and to the south by the U.S. states of Wisconsin and Michigan. It is the largest freshwater lake in the...

during a winter storm. Bodies of some were recovered in the spring, but the ship remained missing until August 21, 1977, when it was discovered by two scuba divers near Isle RoyaleIsle RoyaleIsle Royale is an island of the Great Lakes, located in the northwest of Lake Superior, and part of the state of Michigan. The island and the 450 surrounding smaller islands and waters make up Isle Royale National Park....

. - Born: Helen WattsHelen WattsHelen Watts CBE was a Welsh contralto. She was born at Wales in Milford Haven and educated at the School of S. Mary and S. Anne, Abbots Bromley and the Royal Academy of Music. She began her career with the Glyndebourne Festival Chorus, and was a regular broadcaster on the Welsh Home Service...

, Welsh contralto, in Milford HavenMilford HavenMilford Haven is a town and community in Pembrokeshire, Wales. It is situated on the north side of the Milford Haven Waterway, a natural harbour used as a port since the Middle Ages. The town was founded in 1790 on the north side of the Waterway, from which it takes its name...

(d. 2009)

December 8, 1927 (Thursday)

- The Brookings InstitutionBrookings InstitutionThe Brookings Institution is a nonprofit public policy organization based in Washington, D.C., in the United States. One of Washington's oldest think tanks, Brookings conducts research and education in the social sciences, primarily in economics, metropolitan policy, governance, foreign policy, and...

, one of the earliest political and economic research institutes, was created by the merger of three organizations that had been created by philanthropist Robert S. BrookingsRobert S. BrookingsRobert Somers Brookings was an American businessman and philanthropist, known for his involvement with Washington University in St. Louis and his founding of the Brookings Institution.-Biography:Brookings grew up on the Little Elk Creek in Cecil County, near Baltimore, Maryland...

: the Institute for Government Research, the Institute of Economics, and the Robert Brookings Graduate School. - Born: Vladimir ShatalovVladimir ShatalovVladimir Aleksandrovich Shatalov is a former Soviet cosmonaut who flew three space missions of the Soyuz programme: Soyuz 4, Soyuz 8, and Soyuz 10....

, Soviet cosmonaut on Soyuz 4, Soyuz 8 and Soyuz 10; in Petropavlosk, Kazakh SSRPetropavlPetropavl is a city on the Ishim River in North Kazakhstan Province of Kazakhstan close to the border with Russia, about 261 km west of Omsk along the Trans-Siberian Railway. It is capital of the North Kazakhstan Province...

; Niklas LuhmannNiklas LuhmannNiklas Luhmann was a German sociologist, and a prominent thinker in sociological systems theory.-Biography:...

, German social theorist, in LüneburgLüneburgLüneburg is a town in the German state of Lower Saxony. It is located about southeast of fellow Hanseatic city Hamburg. It is part of the Hamburg Metropolitan Region, and one of Hamburg's inner suburbs...

(d. 1998); and Parkash Singh Badal, Chief Minister of the Indian State of Punjab on four occasions since 1970; in Abul Khurana

December 9, 1927 (Friday)

- The Washington Herald, owned by William Randolph Hearst, published a front page story alleging that Mexico's President Plutarco Calles had proposed bribing four United States Senators to advance Mexico's interests. Days later, Hearst provided documentation revealing the names of the four Senators: William Borah (R-Idaho), J. Thomas HeflinJ. Thomas HeflinJames Thomas Heflin , nicknamed "Cotton Tom", was a leading proponent of white supremacy, most notably as a United States Senator from Alabama.-Biography:...

(D-Alabama), Robert M. La Follette, Jr.Robert M. La Follette, Jr.Robert Marion "Young Bob" La Follette, Jr. was an American senator from Wisconsin from 1925 to 1947, the son of Robert M. La Follette, Sr., the brother of Philip La Follette, and Fola La Follette, whose husband was the playwright George Middleton.- Early life:La Follette was born in Madison,...

(R-Wisconsin) and George W. Norris (R-Nebraska), who all denied any payment from Mexico, while the Mexican government questioned the authenticity of the documents possessed by the Herald. - Born: Pierre HenryPierre HenryPierre Henry is a French composer, considered a pioneer of the musique concrète genre of electronic music.-Biography:...

, French electronic music composer, in ParisParisParis is the capital and largest city in France, situated on the river Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region... - Died: Dr. Paul Jeserich, 73, celebrated as "The German Sherlock Holmes" because of his skills as a forensic detective.

December 10, 1927 (Saturday)

- The Grand Ole OpryGrand Ole OpryThe Grand Ole Opry is a weekly country music stage concert in Nashville, Tennessee, that has presented the biggest stars of that genre since 1925. It is also among the longest-running broadcasts in history since its beginnings as a one-hour radio "barn dance" on WSM-AM...

received its name, after the NBC Radio Network show The WSM Barn Dance followed a presentation of the Grand Opera on NBC's Music Appreciation Hour. WSM director George D. Day told audiences that after listening... - The House voted to confer the Medal of Honor upon Colonel Charles Lindbergh.

- Born: Agnes NixonAgnes NixonAgnes Nixon is an American writer and producer. She attended Northwestern University where she was a member of Alpha Chi Omega sorority, and is best known as the creator of soap operas such as One Life to Live and All My Children...

, American soap opera producer and writer who created One Life to LiveOne Life to LiveOne Life to Live is an American soap opera which debuted on July 15, 1968 and has been broadcast on the ABC television network. Created by Agnes Nixon, the series was the first daytime drama to primarily feature racially and socioeconomically diverse characters and consistently emphasize social...

and All My ChildrenAll My ChildrenAll My Children is an American television soap opera that aired on ABC from January 5, 1970 to September 23, 2011. Created by Agnes Nixon, All My Children is set in Pine Valley, Pennsylvania, a fictitious suburb of Philadelphia. The show features Susan Lucci as Erica Kane, one of daytime's most...

; as Agnes Eckhardt in ChicagoChicagoChicago is the largest city in the US state of Illinois. With nearly 2.7 million residents, it is the most populous city in the Midwestern United States and the third most populous in the US, after New York City and Los Angeles...

December 11, 1927 (Sunday)

- At 4:00 am, the Chinese city of CantonGuangzhouGuangzhou , known historically as Canton or Kwangchow, is the capital and largest city of the Guangdong province in the People's Republic of China. Located in southern China on the Pearl River, about north-northwest of Hong Kong, Guangzhou is a key national transportation hub and trading port...

(now GuangzhouGuangzhouGuangzhou , known historically as Canton or Kwangchow, is the capital and largest city of the Guangdong province in the People's Republic of China. Located in southern China on the Pearl River, about north-northwest of Hong Kong, Guangzhou is a key national transportation hub and trading port...

) was seized in an uprising of 20,000 Communists, who announced that the formation of the "Canton Soviet". The Red Guards and their sympathizers seized control of police stations and the city prison, murdering police and guards, seizing control of the arsenal, and releasing prisoners. The Nationalist Army retook the city two days later, and carried out an even bloodier retaliation. At least 2,000 members of the Red Guards, whose dyed scarves had left a red stain on their collars, were arrested and summarily executed, while another 4,000 civilians were murdered in the five-day long "White Terror" carried out by the Nationalist Troops.

December 12, 1927 (Monday)

- OklahomaOklahomaOklahoma is a state located in the South Central region of the United States of America. With an estimated 3,751,351 residents as of the 2010 census and a land area of 68,667 square miles , Oklahoma is the 28th most populous and 20th-largest state...

's Governor Henry S. JohnstonHenry S. JohnstonHenry Simpson Johnston was an American lawyer and politician who served as a delegate to the Oklahoma Constitutional Convention, the first President pro tempore of the Oklahoma Senate, and the seventh Governor of Oklahoma...

, threatened with impeachment by the state legislature, called out the Oklahoma National GuardOklahoma National GuardThe Oklahoma National Guard, a division of the Oklahoma Department of the Military, is the component of the United States National Guard in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. It comprises both Army and Air National Guard components. The Governor of Oklahoma is Commander-in-Chief of the Oklahoma National...

to prevent members of the state House of Representatives from meeting at the capitol building. The next day, house members met at the Huckins Hotel in Oklahoma City hotel and voted to impeach Governor Johnston, state Supreme Court Chief Justice Fred P. Branson, and State Board of Agriculture chairman Henry B. Cordell. An injunction was issued against the Senators to prevent them from attempting to conduct an impeachment trial. On December 28, the guardsmen barred members of the state Senate from meeting at the capitol building, and advised the group that - The National Builders Bank, located in ChicagoChicagoChicago is the largest city in the US state of Illinois. With nearly 2.7 million residents, it is the most populous city in the Midwestern United States and the third most populous in the US, after New York City and Los Angeles...

, opened the first branch that would operate 24/7, with shifts to "render twenty-four hour service 365 days a year". - Tommy LoughranTommy LoughranThomas Patrick Loughran was the light heavyweight boxing champion of the world.Loughran's effective use of coordinated foot work, sound defense and swift, accurate counter punching is now regarded as a precursor to the techniques practiced in modern boxing...

defeated world light heavyweight boxing champion Jimmy SlatteryJimmy SlatteryJames Edward Slattery was a professional boxer in the Light Heavyweight division. James Edward Slattery (born August 25, 1904 in Buffalo, NY - died August 30, 1960) was a professional boxer in the Light Heavyweight (175lb) division. James Edward Slattery (born August 25, 1904 in Buffalo, NY -...

in a 15 round decision at New York's Madison Square Garden. - Born: Robert NoyceRobert NoyceRobert Norton Noyce , nicknamed "the Mayor of Silicon Valley", co-founded Fairchild Semiconductor in 1957 and Intel in 1968...

, co-inventor of the microchip and cofounder of Fairchild SemiconductorFairchild SemiconductorFairchild Semiconductor International, Inc. is an American semiconductor company based in San Jose, California. Founded in 1957, it was a pioneer in transistor and integrated circuit manufacturing...

and Intel; in Burlington, IowaBurlington, IowaBurlington is a city in, and the county seat of Des Moines County, Iowa, United States. The population was 25,663 in the 2010 census, a decline from the 26,839 population in the 2000 census. Burlington is the center of a micropolitan area including West Burlington, Iowa and Middletown, Iowa and...

(d. 1990)

December 13, 1927 (Tuesday)

- Charles LindberghCharles LindberghCharles Augustus Lindbergh was an American aviator, author, inventor, explorer, and social activist.Lindbergh, a 25-year-old U.S...

made a daring non-stop flight from Washington DC, bound for Mexico City. He landed more than 24 hours later after going through bad weather. Reputedly, after getting lost, he flew in low enough to spot the word "Caballeros" at one railroad station and could not find it on his map, before learning later that it was the word for "Gentlemen" on a men's bathroom. - Born: James WrightJames Wright (poet)James Arlington Wright was an American poet.Wright first emerged on the literary scene in 1956 with The Green Wall, a collection of formalist verse that was awarded the prestigious Yale Younger Poets Prize. But by the early 1960s, Wright, increasingly influenced by the Spanish language...

, American poet, in Martins Ferry, OhioMartins Ferry, OhioDuring the census of 2000, there were 7,226 people, 3,202 households, and 1,959 families residing in the city. The population density was 3,345.1 people per square mile . There were 3,680 housing units at an average density of 1,703.6 per square mile...

(d. 1980)

December 14, 1927 (Wednesday)

- The United Kingdom and the Kingdom of Iraq signed a Treaty of Alliance and Amity.

- The aircraft carrier USS LexingtonUSS Lexington (CV-2)USS Lexington , nicknamed the "Gray Lady" or "Lady Lex," was an early aircraft carrier of the United States Navy. She was the lead ship of the , though her sister ship was commissioned a month earlier...

, recently converted from a battle cruiser, was commissioned. The ship would be damaged beyond repair in 1942 during the Battle of the Coral SeaBattle of the Coral SeaThe Battle of the Coral Sea, fought from 4–8 May 1942, was a major naval battle in the Pacific Theater of World War II between the Imperial Japanese Navy and Allied naval and air forces from the United States and Australia. The battle was the first fleet action in which aircraft carriers engaged...

. - The British House of LordsHouse of LordsThe House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster....

approved the Archbishop of Canterbury's request for approval of a revision to the Book of Common Prayer, 241-88.

December 15, 1927 (Thursday)

- Marion Parker, 12, was kidnapped from Mount Vernon Junior High School in Los Angeles. Her dismembered body was dumped from the kidnapper's car two days later, after her father paid a $1,500 ransom. . Following the largest manhunt to that time on the West Coast, her killer, William Edward HickmanEdward HickmanWilliam Edward Hickman was an American criminal responsible for the kidnapping, murder and dismemberment of Marion Parker, a 12-year-old girl...

, was arrested on December 22 at the town of Echo, OregonEcho, OregonEcho is a city in Umatilla County, Oregon, United States. The population was 650 at the 2000 census. It is part of the Pendleton–Hermiston Micropolitan Statistical Area.-History:...

. He would be hanged on October 19, 1928. - The British House of Commons rejected the proposed revision of the Anglican Book of Common PrayerBook of Common PrayerThe Book of Common Prayer is the short title of a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion, as well as by the Continuing Anglican, "Anglican realignment" and other Anglican churches. The original book, published in 1549 , in the reign of Edward VI, was a product of the English...

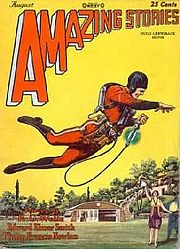

, by a vote of 247-205. - In fiction, Anthony "Buck" RogersBuck RogersAnthony Rogers is a fictional character that first appeared in Armageddon 2419 A.D. by Philip Francis Nowlan in the August 1928 issue of the pulp magazine Amazing Stories. A sequel, The Airlords of Han, was published in the March 1929 issue....

, of the American Radioactive Gas Corporation, was entombed by a rockfall in an abandoned coal mine in Pennsylvania. Kept in a state of suspended animation by the radioactive gas, he would be revived 492 years later, in the year 2419 and go on to further adventures. Buck Rogers was introduced in Philip Francis Nowlan's science fiction novella, Armageddon 2419 A.D.Armageddon 2419 A.D.Armageddon 2419 A.D. is Philip Francis Nowlan's novella which first appeared in the August 1928 issue of the pulp magazine Amazing Stories. A sequel called The Airlords of Han was published in the March 1929 issue of Amazing Stories. Both stories are now in the public domain in the US according to...

in the August 1928 issue of Amazing Stories.

December 16, 1927 (Friday)

- Pope Pius XIPope Pius XIPope Pius XI , born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti, was Pope from 6 February 1922, and sovereign of Vatican City from its creation as an independent state on 11 February 1929 until his death on 10 February 1939...

instructed his Cardinal Secretary of StateCardinal Secretary of StateThe Cardinal Secretary of State—officially Secretary of State of His Holiness The Pope—presides over the Holy See, usually known as the "Vatican", Secretariat of State, which is the oldest and most important dicastery of the Roman Curia...

, Pietro GasparriPietro GasparriPietro Gasparri was a Roman Catholic archbishop, diplomat and politician in the Roman Curia and signatory of the Lateran Pacts.- Biography :...

, to cease further discussions with the Soviet UnionSoviet UnionThe Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

, based on the increase there of religious persecution. Relations would be reopened by Nikita KhrushchevNikita KhrushchevNikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev led the Soviet Union during part of the Cold War. He served as First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964, and as Chairman of the Council of Ministers, or Premier, from 1958 to 1964...

in November 1961November 1961January – February – March – April – May – June – July – August – September – October – November-DecemberThe following events occurred in November 1961.-November 1, 1961 :...

. - General Edwin B. Winans, superintendent of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, announced that the annual Army-Navy gameArmy-Navy GameThe Army–Navy Game is an an American college football rivalry game between the teams of the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York and the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland. The USMA team, "Army", and the USNA team, "Navy", each represent their services' oldest...

of college football would not be played in future seasons, after contract negotiations with the U.S. Naval Academy fell through. The popular game was renewed in 1930. - Died: Benjamin Purnell, 66, founder and self-styled "King" of the House of David colony at Benton Harbor, MichiganBenton Harbor, MichiganBenton Harbor is a city in Berrien County in the U.S. state of Michigan which is located west of Kalamazoo. The population was 10,038 at the 2010 census. It is the lesser populated of the two principal cities included in the Niles-Benton Harbor, Michigan Metropolitan Statistical Area, which has a...

.

December 17, 1927 (Saturday)

- The U.S. Navy submarine S-4USS S-4 (SS-109)USS S-4 was an S-class submarine of the United States Navy. In 1927, she was sunk by being accidentally rammed by a Coast Guard destroyer with the loss of all hands but was raised and restored to service until stricken in 1936.-Building:...

was accidentally rammed by the United States Coast GuardUnited States Coast GuardThe United States Coast Guard is a branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the seven U.S. uniformed services. The Coast Guard is a maritime, military, multi-mission service unique among the military branches for having a maritime law enforcement mission and a federal regulatory agency...

destroyer Paulding off of the coast of Provincetown, MassachusettsProvincetown, MassachusettsProvincetown is a New England town located at the extreme tip of Cape Cod in Barnstable County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 3,431 at the 2000 census, with an estimated 2007 population of 3,174...

, tearing the hull. The sub sank immediately, and drowning 34 of the 40 men onboard. Six men in the forward torpedo room survived and communicated with divers by tapping in Morse code on the sub's hull, but severe weather delayed the rescue and the trapped survivors died after three days. - Dietrich BonhoefferDietrich BonhoefferDietrich Bonhoeffer was a German Lutheran pastor, theologian and martyr. He was a participant in the German resistance movement against Nazism and a founding member of the Confessing Church. He was involved in plans by members of the Abwehr to assassinate Adolf Hitler...

presented and defended his doctoral dissertation, the groundbreaking Sanctorum Communio, at the University of Berlin, beginning a career in the defense of the Christian faith against the German government. - Died:Hubert HarrisonHubert HarrisonHubert Henry Harrison was a West Indian-American writer, orator, educator, critic, and radical socialist political activist based in Harlem, New York. He was described by activist A. Philip Randolph as “the father of Harlem radicalism” and by the historian Joel Augustus Rogers as “the foremost...

, 44, African American writer, critic, and activist, following complications from an appendectomy; and Rajendra Nath Lahiri, 26, IndiaIndiaIndia , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

n RevolutionaryRevolutionaryA revolutionary is a person who either actively participates in, or advocates revolution. Also, when used as an adjective, the term revolutionary refers to something that has a major, sudden impact on society or on some aspect of human endeavor.-Definition:...

, Hindustan Republican Association

December 18, 1927 (Sunday)

- The Fifteenth Congress of the Soviet Communist Party voted its approval of the expulsion of Leon TrotskyLeon TrotskyLeon Trotsky , born Lev Davidovich Bronshtein, was a Russian Marxist revolutionary and theorist, Soviet politician, and the founder and first leader of the Red Army....

, Grigory ZinovievGrigory ZinovievGrigory Yevseevich Zinoviev , born Ovsei-Gershon Aronovich Radomyslsky Apfelbaum , was a Bolshevik revolutionary and a Soviet Communist politician...

, and 98 other opponents of Party First Secretary Joseph StalinJoseph StalinJoseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

. - Born: Roméo LeBlancRoméo LeBlancRoméo-Adrien LeBlanc was a Canadian journalist, politician, and statesman who served as Governor General of Canada, the 25th since Canadian Confederation....

, 25th Governor General of CanadaGovernor General of CanadaThe Governor General of Canada is the federal viceregal representative of the Canadian monarch, Queen Elizabeth II...

(1995-1999); in Memramcook, New BrunswickMemramcook, New BrunswickMemramcook is a Canadian village in Westmorland County, New Brunswick. Located in south-eastern New Brunswick, the community is predominantly people of Acadian descent who speak the Chiac derivative of the French language....

(d. 2009); Ramsey ClarkRamsey ClarkWilliam Ramsey Clark is an American lawyer, activist and former public official. He worked for the U.S. Department of Justice, which included service as United States Attorney General from 1967 to 1969, under President Lyndon B. Johnson...

, U.S. Attorney General (1967-69) and later a controversial left-wing activist, in Dallas; and Marilyn Sachs, prolific American children's author, in New York City.

December 19, 1927 (Monday)

- The Dow Jones Industrial AverageDow Jones Industrial AverageThe Dow Jones Industrial Average , also called the Industrial Average, the Dow Jones, the Dow 30, or simply the Dow, is a stock market index, and one of several indices created by Wall Street Journal editor and Dow Jones & Company co-founder Charles Dow...

broke 200 points for the first time. By the end of 1928, it would reflect a 50% increase in stock prices, rising to 300, peaking at 386.10 on September 3, 1929. A month later, the stock market would crash. At its lowest point during the Great DepressionGreat DepressionThe Great Depression was a severe worldwide economic depression in the decade preceding World War II. The timing of the Great Depression varied across nations, but in most countries it started in about 1929 and lasted until the late 1930s or early 1940s...

, it would close at 41.22 on July 8, 1932. - For the first time in the history of Vatican City, there were as many non-Italians as there were Italians in the College of Cardinals, as Pope Pius XIPope Pius XIPope Pius XI , born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti, was Pope from 6 February 1922, and sovereign of Vatican City from its creation as an independent state on 11 February 1929 until his death on 10 February 1939...

appointed five men to fill vacancies in the 66 member College. Two were from France, and one apiece from Canada, Spain and Hungary. - IndiaIndiaIndia , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

n Revolutionaries viz Pandit Ram Prasad BismilRam Prasad BismilRam Prasad Bismil Ram Prasad Bismil Ram Prasad Bismil (Hindi: राम प्रसाद 'बिस्मिल', Gujarati: રામપ્રસાદ બિસ્મિલ, (Malayalam: രാം പ്രസാദ് ബിസ്മിൽ, Tamil: ராம் பிரசாத் பிஸ்மில், Born: 11 June 1897, Executed: 19 December 1927) was an Indian revolutionary who participated in Mainpuri Shadyantra of...

, Thakur Roshan SinghRoshan Singhand rohanThakur Roshan Singh was an Indian revolutionary who was sentenced in the Bareilly Goli Kand in the Non Cooperation Movement of 1921-22...

and Ashfaqulla KhanAshfaqulla KhanAshfaqulla Khan was a Muslim freedom fighter in the Indian independence movement who had given away his life along with Ram Prasad Bismil. Bismil and Ashfaq, both were good friends and Urdu poets...

were executed by the British EmpireBritish EmpireThe British Empire comprised the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom. It originated with the overseas colonies and trading posts established by England in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. At its height, it was the...

. Rajendra Nath Lahiri had been executed two days earlier. All four men, members of the anti-British Hindustan Republican Association were hanged at the Gorkakhpur District Jail.

December 20, 1927 (Tuesday)

- The closely watched murder trial of lawyer-turned-bootlegger, George RemusGeorge RemusGeorge Remus was a famous Cincinnati lawyer and bootlegger during the Prohibition era. It has been claimed that he was the inspiration for the title character Jay Gatsby in The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald....

, ended with a finding that he was not guilty by reason of insanity. Remus had shot and killed his wife in October as she was on her way to divorce court. The jury in Cincinnati deliberated 19 minutes before acquitting him. - Seven miners were killed in the explosion of a coal mine at Stiritz, Illinois

- Born: Charlie CallasCharlie CallasCharlie Callas was an American comedian and actor most commonly known for his work with Mel Brooks, Jerry Lewis, and Dean Martin and his many stand-up appearances on television talk shows in the 1970s...

, American comedian, in BrooklynBrooklynBrooklyn is the most populous of New York City's five boroughs, with nearly 2.6 million residents, and the second-largest in area. Since 1896, Brooklyn has had the same boundaries as Kings County, which is now the most populous county in New York State and the second-most densely populated...

(d. 2011); David MarksonDavid MarksonDavid Markson was an American novelist, born David Merrill Markson in Albany, New York. He is the author of several postmodern novels, including Springer's Progress, Wittgenstein's Mistress, and Reader's Block...

, American novelist, in New York City (d. 2010); and Kim Young-samKim Young-samKim Young-sam was a South Korean politician and democratic activist. From 1961, he spent 30 years as South Korea's leader of the opposition, and one of Park Chung-hee's most powerful rivals....

, 14th President of South KoreaPresident of South KoreaThe President of the Republic of Korea is, according to the Constitution of the Republic of Korea, chief executive of the government, commander-in-chief of the armed forces, and the head of state of the Republic of Korea...

and the first civilian to serve in that job (1993-1998); in GeojeGeojeGeoje is a city located in South Gyeongsang province, just off the coast of the port city of Busan, South Korea. Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering in Okpo and Samsung Heavy Industries in Gohyeon are both located on Geoje Island. The city also offers a wide range of tourist sights...

December 21, 1927 (Wednesday)

- The trademark and logo for PlayskoolPlayskoolPlayskool is an American company that produces educational toys and games for children. It is a subsidiary of Hasbro, Inc., and is headquartered in Pawtucket, Rhode Island.-History:...

, manufacturer of educational toys, was registered. - The Ethnological Missionary MuseumVatican MuseumsThe Vatican Museums , in Viale Vaticano in Rome, inside the Vatican City, are among the greatest museums in the world, since they display works from the immense collection built up by the Roman Catholic Church throughout the centuries, including some of the most renowned classical sculptures and...

was inaugurated at the Vatican at the Lateran PalaceLateran PalaceThe Lateran Palace , formally the Apostolic Palace of the Lateran , is an ancient palace of the Roman Empire and later the main Papal residence....

.

December 22, 1927 (Thursday)

- The United States and NicaraguaNicaraguaNicaragua is the largest country in the Central American American isthmus, bordered by Honduras to the north and Costa Rica to the south. The country is situated between 11 and 14 degrees north of the Equator in the Northern Hemisphere, which places it entirely within the tropics. The Pacific Ocean...

signed an agreement for the 1,229 member Nicaraguan Guardia Nacional to be the sole military and police force, in return for U.S. training and sponsorship. - After three weeks of display to the public, mass production of the Model AFord Model AThe Model A is the designation of two cars made by Ford Motor Company, one in 1903 and one beginning in 1927:* Ford Model A * Ford Model A...

automobile and its shipment to dealers began.

December 23, 1927 (Friday)

- The annual caddy championship at the Glen Garden Country Club in Fort Worth, Texas, pitted two future golf legends against each other. Both were 15 years old. Byron NelsonByron NelsonJohn Byron Nelson, Jr. was an American PGA Tour golfer between 1935 and 1946.Nelson and two other well known golfers of the time, Ben Hogan and Sam Snead, were born within seven months of each other in 1912...

defeated Ben HoganBen HoganWilliam Ben Hogan was an American golfer, generally considered one of the greatest players in the history of the game...

by one stroke. - Mrs. Frances WilsonFrances Wilson GraysonFrances Wilson Grayson was an American aviatrix who died flying to Newfoundland just prior to her trip to cross the Atlantic Ocean.-Birth and education:...

and three men set off in her airplane, the Dawn, in a quest for her to become the first woman to fly across the Atlantic ocean. . The airplane disappeared over NewfoundlandNewfoundlandNewfoundland usually refers to either:* Newfoundland, the former name of Newfoundland and Labrador, a Canadian province in the eastern part of Canada* Newfoundland , an island that forms part of the province of Newfoundland and Labrador...

, and was never found. - Santa Claus Bank RobberySanta Claus Bank RobberyThe Santa Claus Bank Robbery occurred on December 23, 1927 in the Central Texas town of Cisco. Marshall Ratliff, dressed as Santa Claus, along with Henry Helms and Robert Hill, all ex-cons, and Louis Davis, a relative of Helms, held up the First National Bank in Cisco. The robbery is one of Texas'...

: Four ex-convicts robbed the First National Bank of Cisco, TexasCisco, TexasCisco is a city in Eastland County, Texas, United States. The population was 3,851 at the 2000 census.-History:Conrad Hilton started the Hilton Hotel chain with a single hotel bought in Cisco. Hilton came to Cisco to buy a bank, but the bank cost too much; so he purchased the Mobley Hotel in 1919...

of $12,400, killing the town's police chief and a deputy - Born: Stanley WolpertStanley WolpertStanley Wolpert is an American Indologist, author, and academic. He is considered one of the world's foremost authorities on the political and intellectual history of modern India and Pakistan and has written fiction and nonfiction books on the topics...

, American anthropologist and expert on the cultures of the Indian subcontinent; in Brooklyn; and Joaquin CapillaJoaquín CapillaJoaquín Capilla Pérez born in Mexico City was a Mexican diver. He won the bronze medal in the platform diving event at the 1948 Olympic Games in London, England, the silver medal in the platform diving event again at the 1952 Olympic games in Helsinki, and the gold in the platform and the bronze...

, Mexican diver, Olympic gold medalist, 1956

December 24, 1927 (Saturday)

- The Standard OilStandard OilStandard Oil was a predominant American integrated oil producing, transporting, refining, and marketing company. Established in 1870 as a corporation in Ohio, it was the largest oil refiner in the world and operated as a major company trust and was one of the world's first and largest multinational...

refinery in Tientsin caught fire during a battle between opposing forces in China. Over the next four days, the United States Marines, sent earlier in the year to protect American interests, successfully battled the blaze and saved the city from destruction. - The first All-India Music Conference was held in conjunction with a meeting of the Indian National Congress in Madras.

- Born: Mary Higgins ClarkMary Higgins ClarkMary Theresa Eleanor Higgins Clark Conheeney , known professionally as Mary Higgins Clark, is an American author of suspense novels...

, American suspense author, in the Bronx, New York

December 25, 1927 (Sunday)

- A copy of the Manusmriti, the Hindu holy book that established the rules for the caste system in IndiaCaste system in IndiaThe Indian caste system is a system of social stratification and social restriction in India in which communities are defined by thousands of endogamous hereditary groups called Jātis....

, was burned in public at MahadMahadMahad is a city and a municipal council in Raigad district in the Indian state of Maharashtra. It is situated about 175 km to the south of Mumbai . It has become the center of attraction because of its beautiful surroundings and pleasant climate. Mahad has a personality of its own due to its...

, was burned by Dr. B. R. AmbedkarB. R. AmbedkarBhimrao Ramji Ambedkar , popularly also known as Babasaheb, was an Indian jurist, political leader, philosopher, thinker, anthropologist, historian, orator, prolific writer, economist, scholar, editor, a revolutionary and one of the founding fathers of independent India. He was also the Chairman...

, leader of the DalitDalitDalit is a designation for a group of people traditionally regarded as Untouchable. Dalits are a mixed population, consisting of numerous castes from all over South Asia; they speak a variety of languages and practice a multitude of religions...

caste, commonly called the "UntouchablesDalitDalit is a designation for a group of people traditionally regarded as Untouchable. Dalits are a mixed population, consisting of numerous castes from all over South Asia; they speak a variety of languages and practice a multitude of religions...

". - Police officers of South Pittsburg, TennesseeSouth Pittsburg, TennesseeSouth Pittsburg is a city in Marion County, Tennessee, United States. It is part of the Chattanooga, TN–GA Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 3,295 at the 2000 census. South Pittsburg is home to the National Cornbread Festival.-History:...

fought a gun battle with the Marion County, TennesseeMarion County, TennesseeMarion County is a county located in the U.S. state of Tennessee. As of 2000, the population was 27,776. Its county seat is Jasper.Marion County is part of the Chattanooga, TN–GA Metropolitan Statistical Area.-Geography:According to the U.S...

Sheriff and his deputies on the streets of the town on ChristmasChristmasChristmas or Christmas Day is an annual holiday generally celebrated on December 25 by billions of people around the world. It is a Christian feast that commemorates the birth of Jesus Christ, liturgically closing the Advent season and initiating the season of Christmastide, which lasts twelve days...

night. Sheriff Wash Coppinger, City Marshal Ewing Smith, former City Marshal Ben Parker, deputy sheriff L.A. Hennessey, and city policeman O.H. Larrowe died at the scene, and city deputy marshal James Conner was seriously wounded. - Born: Nellie FoxNellie FoxJacob Nelson Fox was a Major League Baseball second baseman for the Chicago White Sox. Fox was born in St. Thomas Township, Pennsylvania. He was selected as the MVP of the American League in...

, American baseball player, in St. Thomas Township, PennsylvaniaSt. Thomas Township, PennsylvaniaSt. Thomas Township is a township in Franklin County, Pennsylvania, United States. The population was 5,775 at the 2000 census.It is the birthplace of Baseball Hall of Fame member Nellie Fox.-Geography:...

, as Jacob Nelson Fox; member, Baseball Hall of Fame; (d. 1975); and Ram NarayanRam NarayanRam Narayan , often referred to by the title Pandit, is an Indian musician who popularized the bowed instrument sarangi as a solo concert instrument in Hindustani classical music and became the first internationally successful sarangi player....

, Indian musician who popularized the string instrument sarangiSarangiThe Sārangī is a bowed, short-necked string instrument of India which is originated from Rajasthani folk instruments. It plays an important role in India's Hindustani classical music tradition...

; in UdaipurUdaipurUdaipur , also known as the City of Lakes, is a city, a Municipal Council and the administrative headquarters of the Udaipur district in the state of Rajasthan in western India. It is located southwest of the state capital, Jaipur, west of Kota, and northeast from Ahmedabad... - Died: Sergey SazonovSergey SazonovSergei Dmitrievich Sazonov GCB was a Russian statesman who served as Foreign Minister from September 1910 to June 1916...

, 67, former Foreign Minister of the Russian EmpireRussian EmpireThe Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

(1910-1916)

December 26, 1927 (Monday)

- Belgian science fiction author J.-H. RosnyJ.-H. RosnyJ.-H. Rosny was the pseudonym of the brothers Joseph Henri Honoré Boex and Séraphin Justin François Boex , both born in Brussels. Together they wrote a series of novels and short stories about natural, prehistoric and fantasy subjects, published between 1886 and 1909, as well as several popular...

indirectly coined the word "astronautAstronautAn astronaut or cosmonaut is a person trained by a human spaceflight program to command, pilot, or serve as a crew member of a spacecraft....

" at a meeting of the French Astronomical Society to establish an annual award for outstanding work in promoting manned spaceflight. Asked to suggest a descriptive word for space travel, Rosny proposed l'astronautique, using the Greek rootwords for navigation of the stars. - The Hominy Indians, an all-Indian football team, upset the New York Giants 13-6 in an exhibition game.

- The emerging religion of Caodaism was outlawed by a royal ordinance of the King of Cambodia.

- Born: Alan KingAlan King (comedian)Alan King was an American actor and comedian known for his biting wit and often angry humorous rants. King became well known as a Jewish comedian and satirist. He was also a serious actor who appeared in a number of movies and television shows. King wrote several books, produced films, and...

, American comedian; as Irwin Alan Kniberg in New York CityNew York CityNew York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

(d. 2004); Akihiko HirataAkihiko Hiratawas a Japanese film actor. While Hirata starred in many movies , he is most well known for his work in the kaiju genre, including such films as King Kong vs. Godzilla, The Mysterians, and his most famous role of Dr...

, Japanese film actor, in Keijo, ChosenChosenChosen can mean:*Chosen people, people who believe they have been chosen by a higher power to do a certain thing including**Jews as a chosen people-Korean:...

, Japanese Empire (now SeoulSeoulSeoul , officially the Seoul Special City, is the capital and largest metropolis of South Korea. A megacity with a population of over 10 million, it is the largest city proper in the OECD developed world...

, South KoreaSouth KoreaThe Republic of Korea , , is a sovereign state in East Asia, located on the southern portion of the Korean Peninsula. It is neighbored by the People's Republic of China to the west, Japan to the east, North Korea to the north, and the East China Sea and Republic of China to the south...

) (d. 1984); and Denis QuilleyDenis QuilleyDenis Clifford Quilley OBE was an English theatre, television and film actor who was long associated with the Royal National Theatre....

, British actor, in London (d. 2003);

December 27, 1927 (Tuesday)

- Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II's musical play Show BoatShow BoatShow Boat is a musical in two acts with music by Jerome Kern and book and lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II. It was originally produced in New York in 1927 and in London in 1928, and was based on the 1926 novel of the same name by Edna Ferber. The plot chronicles the lives of those living and working...

, based on Edna FerberEdna FerberEdna Ferber was an American novelist, short story writer and playwright. Her novels were especially popular and included the Pulitzer Prize-winning So Big , Show Boat , and Giant .-Early years:Ferber was born August 15, 1885, in Kalamazoo, Michigan,...

's novel, produced by Florenz ZiegfeldFlorenz ZiegfeldFlorenz Ziegfeld, Jr. , , was an American Broadway impresario, notable for his series of theatrical revues, the Ziegfeld Follies , inspired by the Folies Bergère of Paris. He also produced the musical Show Boat...

; opened on Broadway and went on to become the first great classic of the American musical theatre. It ran for 572 performances, closing on May 4, 1929. - Born: George StreisingerGeorge StreisingerGeorge Streisinger was a molecular biologist at the University of Oregon. He was the first person to clone a vertebrate, cloning zebra fish in his University of Oregon laboratory. He also pioneered work in the genetics of the T-even bacterial viruses...

, Hungarian-born American molecular biologist who became the first person to clone a vertebrate animal; in BudapestBudapestBudapest is the capital of Hungary. As the largest city of Hungary, it is the country's principal political, cultural, commercial, industrial, and transportation centre. In 2011, Budapest had 1,733,685 inhabitants, down from its 1989 peak of 2,113,645 due to suburbanization. The Budapest Commuter...

, HungaryHungaryHungary , officially the Republic of Hungary , is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is situated in the Carpathian Basin and is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine and Romania to the east, Serbia and Croatia to the south, Slovenia to the southwest and Austria to the west. The...

(d. 1984); Anne ArmstrongAnne ArmstrongAnne Legendre Armstrong was a United States diplomat and politician, and the first female Counselor to the President; she served in that capacity under both the Ford and Nixon administrations. She was also the recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom.- Biography :She was born in New Orleans,...

, the first woman to serve as Counselor to the PresidentCounselor to the PresidentThe Counselor to the President is the highest-ranking assistant to the President of the United States for communications, and a member of the Executive Office of the President of the United States. In the administration of George W. Bush, the Counselor oversaw the Communications, Media Affairs,...

, in New Orleans (d. 2008); and Bill CrowBill CrowBill Crow is an American jazz bassist and author.Crow was born in Othello, Washington in the United States of America, but spent his childhood in Kirkland, Washington. After high school, he briefly played sousaphone at the University of Washington in Seattle...

, American jazz musician, in Othello, WashingtonOthello, WashingtonOthello is a city in Adams County, Washington, United States. The population was 5,847 at the 2000 census and grew 25.9% over the next decade to 7,364 at the 2010 census. Othello refers to the city as being in the "Heart" of the Columbia Basin Project...

December 28, 1927 (Wednesday)

- U.S. Secretary of State Frank B. KelloggFrank B. KelloggFrank Billings Kellogg was an American lawyer, politician and statesman who served in the U.S. Senate and as U.S. Secretary of State. He co-authored the Kellogg-Briand Pact, for which he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for 1929..- Biography :Kellogg was born in Potsdam, New York, and his family...

informed the French Ambassador to the U.S., Paul Claudel, that his government proposed to extend American-French negoitations to create a multinational treaty to forever outlaw war, with the goal of having nations "renounce war as an instrument of national policy". Sixty four nations signed the Kellogg-Briand Peace Pact on August 27, 1928, pledging to never again go to war, and the Pact took effect on July 24, 1929. - At the age of 30, Dorothy DayDorothy DayDorothy Day was an American journalist, social activist and devout Catholic convert; she advocated the Catholic economic theory of Distributism. She was also considered to be an anarchist, and did not hesitate to use the term...

converted to Roman Catholicism who would become founder of the Catholic Worker MovementCatholic Worker MovementThe Catholic Worker Movement is a collection of autonomous communities of Catholics and their associates founded by Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin in 1933. Its aim is to "live in accordance with the justice and charity of Jesus Christ." One of its guiding principles is hospitality towards those on...

, Eileen Flynn, Why Believe?: Foundations of Catholic Theology (Rowman & Littlefield, 2000) p56

December 29, 1927 (Thursday)

- The eruption of the Perboewatan and Danan undersea volcanoes, near KrakatoaKrakatoaKrakatoa is a volcanic island made of a'a lava in the Sunda Strait between the islands of Java and Sumatra in Indonesia. The name is used for the island group, the main island , and the volcano as a whole. The island exploded in 1883, killing approximately 40,000 people, although some estimates...

, created the foundation for the Anak Krakatau Island. - Born: Andy StanfieldAndy StanfieldAndrew William Stanfield was an American sprinter and Olympic gold and silver medallist.-Biography:...

, American sprinter; Olympic gold medalist, 1952; in Washington, D.C.Washington, D.C.Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

(d. 1985) - Died: Harry Norman Gardiner, 72, British philosopher; from injuries sustained after being struck by a car; and Hakim Ajmal KhanHakim Ajmal KhanAjmal Khan was an Indian physician specialising in the field of South Asian traditional Unani medicine as well as a Muslim nationalist politician and freedom fighter. Through his founding of the Tibbia College in Delhi, he is credited with the revival of Unani medicine in early 20th century...

, 64, activist for Muslim rights in British India

December 30, 1927 (Friday)

- The first Japanese metroRapid transitA rapid transit, underground, subway, elevated railway, metro or metropolitan railway system is an electric passenger railway in an urban area with a high capacity and frequency, and grade separation from other traffic. Rapid transit systems are typically located either in underground tunnels or on...

line, the Ginza Line in TokyoTokyo, ; officially , is one of the 47 prefectures of Japan. Tokyo is the capital of Japan, the center of the Greater Tokyo Area, and the largest metropolitan area of Japan. It is the seat of the Japanese government and the Imperial Palace, and the home of the Japanese Imperial Family...

, opened. - Henry FordHenry FordHenry Ford was an American industrialist, the founder of the Ford Motor Company, and sponsor of the development of the assembly line technique of mass production. His introduction of the Model T automobile revolutionized transportation and American industry...

's antisemitic newspaper, the Dearborn Independent, published its final issue. - The Bellanca Aircraft Company was founded.

- Born: Dean BurchDean BurchDean Burch served as Chairman of the Federal Communications Commission from October 31, 1969 to March 8, 1974, and as chairman of the Republican National Convention....

, FCC Chairman, 1969-1974; in Enid, OklahomaEnid, OklahomaEnid is a city in Garfield County, Oklahoma, United States. In 2010, the population was 49,379, making it the ninth largest city in Oklahoma. It is the county seat of Garfield County. Enid was founded during the opening of the Cherokee Outlet in the Land Run of 1893, and is named after Enid, a...

December 31, 1927 (Saturday)

- After more than seventy years, the first edition of the Oxford English DictionaryOxford English DictionaryThe Oxford English Dictionary , published by the Oxford University Press, is the self-styled premier dictionary of the English language. Two fully bound print editions of the OED have been published under its current name, in 1928 and 1989. The first edition was published in twelve volumes , and...

, with 20 volumes, was declared finished. First proposed in 1857, the project was to use volunteers and to include every word in the English language, the definition, the word's origin and first known usage of each word and its later meanings. - Victor RoosVictor RoosVictor H. Roos was an American founder of several aircraft companies, including Cessna aircraft.- Early life :In 1917 Roos was a distributor of Harley Davidson pedal cycles in Omaha, Nebraska becoming one of the largest distributors in the Midwest....

sold all of his stock in the Cessna-Roos Aircraft CompanyCessnaThe Cessna Aircraft Company is an airplane manufacturing corporation headquartered in Wichita, Kansas, USA. Their main products are general aviation aircraft. Although they are the most well known for their small, piston-powered aircraft, they also produce business jets. The company is a subsidiary...

, and the corporation (and the small airplanes that it manufactured) was renamed Cessna Aircraft Company. - Born: Swami Vishnu-devanandaSwami Vishnu-devanandaSwami Vishnudevananda was a disciple of Swami Sivananda, and founder of the International Sivananda Yoga Vedanta Centres and Ashrams...

, Indian Yogi, in KanimangalamKanimangalamKanimangalam is a suburb of Thrissur in the Thrissur district of the state of Kerala in south India. It is about 4 km away from Thrissur. The main center of Kanimangalam is Valiyalukkal, where the Valiyalukkal Bagavathy Temple is situated...

, KeralaKeralaor Keralam is an Indian state located on the Malabar coast of south-west India. It was created on 1 November 1956 by the States Reorganisation Act by combining various Malayalam speaking regions....

State (d. 1993); and Nancy HanksNancy Hanks (NEA)Nancy Hanks was the second chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts . She was appointed by President Richard M. Nixon and served from 1969 to 1977, continuing her service under President Gerald R. Ford. During this period, Hanks was active in the fight to save the historic Old Post Office...

, Chairman of the National Endowment for the ArtsNational Endowment for the ArtsThe National Endowment for the Arts is an independent agency of the United States federal government that offers support and funding for projects exhibiting artistic excellence. It was created by an act of the U.S. Congress in 1965 as an independent agency of the federal government. Its current...

from 1969-1977, in Miami Beach, FloridaMiami Beach, FloridaMiami Beach is a coastal resort city in Miami-Dade County, Florida, United States, incorporated on March 26, 1915. The municipality is located on a barrier island between the Atlantic Ocean and Biscayne Bay, the latter which separates the Beach from Miami city proper...

(d. 1983)