May 1927

Encyclopedia

January

- February

- March

- April

- May - June

- July

- August

- September

- October

- November

- December

The following events occurred in May

The following events occurred in May

1927.

January 1927

January – February – March – April – May – June – July – August – September – October – November – DecemberThe following events occurred in January 1927.-January 1, 1927 :...

- February

February 1927

The following events occurred in February, 1927.January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - December-February 1, 1927 :*In its third year of conferring B.A...

- March

March 1927

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in March 1927-March 1, 1927 :...

- April

April 1927

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in April 1927:-April 1, 1927 :...

- May - June

June 1927

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in June 1927.-June 1, 1927 :...

- July

July 1927

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in July 1927:-July 1, 1927 :...

- August

August 1927

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in August 1927:-August 1, 1927 :...

- September

September 1927

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in September 1927:-September 1, 1927 :...

- October

October 1927

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in October 1927:-October 1, 1927 :...

- November

November 1927

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in November 1927:-November 1, 1927 :...

- December

December 1927

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October 1927 - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in December 1927:-December 1, 1927:...

May

May is the fifth month of the year in the Julian and Gregorian Calendars and one of seven months with the length of 31 days.May is a month of autumn in the Southern Hemisphere and spring in the Northern Hemisphere...

1927.

May 1, 1927 (Sunday)

- The Experimental Mechanised ForceExperimental Mechanized ForceThe Experimental Mechanized Force was a brigade-sized formation of the British Army. It was officially formed on 27 August 1927, and was intended to investigate and develop the techniques and equipment required for armoured warfare. It was renamed the Experimental Armoured Force the following year...

, the first military unit created for research and development of tanks and other weapons of armoured warfareArmoured warfareArmoured warfare or tank warfare is the use of armoured fighting vehicles in modern warfare. It is a major component of modern methods of war....

, was created as part of the British ArmyBritish ArmyThe British Army is the land warfare branch of Her Majesty's Armed Forces in the United Kingdom. It came into being with the unification of the Kingdom of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. The new British Army incorporated Regiments that had already existed in England...

. - Born: Albert ZafyAlbert ZafyAlbert Zafy is a Malagasy politician. He was the President of Madagascar from 27 March 1993 to 5 September 1996.-Early life and career:...

, President of Madagascar 1993-96, in AmbilobeAmbilobeAmbilobe is a city in Madagascar. It belongs to the district of Ambilobe, which is a part of Diana Region. The town is the capital of Ambilobe district, and according to 2001 census the population was approximately 56,000....

May 2, 1927 (Monday)

- Buck v. BellBuck v. BellBuck v. Bell, , was the United States Supreme Court ruling that upheld a statute instituting compulsory sterilization of the unfit, including the mentally retarded, "for the protection and health of the state." It was largely seen as an endorsement of negative eugenics—the attempt to improve...

: Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. was an American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1902 to 1932...

, delivered the 8-1 majority opinon by the U.S. Supreme Court, upholding a VirginiaVirginiaThe Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there...

law permitting compulsory sterilizationCompulsory sterilizationCompulsory sterilization also known as forced sterilization programs are government policies which attempt to force people to undergo surgical sterilization...

of mentally retarded women, writing, "It is better for all the world, if instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime, or to let them starve for their own imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind." Pierce ButlerPierce Butler (justice)Pierce Butler was an American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1923 until his death in 1939...

was the lone dissenter. - The U.S. Department of Agriculture began the grading of beef sold at retail, on a one year trial, with "choice" and "prime" grades being applied to those producers who requested the service.

- Died: Ernest Starling, 61, British physiologist

May 3, 1927 (Tuesday)

- Dr. Quirino MajoranaQuirino MajoranaQuirino Majorana was an Italian experimental physicist who investigated a wide range of phenomena during his long career as professor of physics at the Universities of Rome, Turin , and Bologna , Italy.-Work:...

, Italian physicist, announced in RomeRomeRome is the capital of Italy and the country's largest and most populated city and comune, with over 2.7 million residents in . The city is located in the central-western portion of the Italian Peninsula, on the Tiber River within the Lazio region of Italy.Rome's history spans two and a half...

that he had invented a system for "wireless transmission of speech by means of ultra-violet rays", which had been tested over a distance of ten miles. - In the largest seizure in the U.S., up to that time of illegal drugs, the British trawler Gabriella was seized in New York Harbor with 2,000 drums of alcohol, valued at $1,200,000. The ship's captain had been free on bond after being arrested the year before for smuggling of 1,200 cases of whiskey.

- Aviator Ferdinand Scholtz set a record for longest time aloft in a glider, keeping the unpowered airplane up for 14 hours and 8 minutes.

- Born: Mell Lazarus, American comic strip artist who created Miss Peach and Momma; in BrooklynBrooklynBrooklyn is the most populous of New York City's five boroughs, with nearly 2.6 million residents, and the second-largest in area. Since 1896, Brooklyn has had the same boundaries as Kings County, which is now the most populous county in New York State and the second-most densely populated...

- Died: Ernest BallErnest BallErnest R. Ball was a United States singer and songwriter, most famous for composing the music for the song "When Irish Eyes Are Smiling" in 1912. He was not, himself, Irish....

, 47, American singer and songwriter

May 4, 1927 (Wednesday)

- At its annual meeting at Columbia UniversityColumbia UniversityColumbia University in the City of New York is a private, Ivy League university in Manhattan, New York City. Columbia is the oldest institution of higher learning in the state of New York, the fifth oldest in the United States, and one of the country's nine Colonial Colleges founded before the...

, the Simplified Spelling BoardSimplified Spelling BoardThe Simplified Spelling Board was an American organization created in 1906 to reform the spelling of the English language, making it simpler and easier to learn, and eliminating many of its inconsistencies...

of America announced partial success in getting dictionary recognition of its alternative spelling of twelve words, with "program" (programme) and "catalog" (catalogue) coming into popular use. Other words were tho, altho, thru, thruout, thoro, thorofare, thoroly, decalog, pedagog and prolog" - Captain Hawthorne C. GrayFlight altitude recordThese are the records set for going the highest in the atmosphere from the age of ballooning onward. Some records are certified by Fédération Aéronautique Internationale.-Fixed-wing aircraft:-Piston-driven propeller aeroplane:...

set an unofficial record for highest altitude reached by a human being, as he attained 42,470 feet (12,945 meters) in a balloon over Belleville, IllinoisBelleville, IllinoisBelleville is a city in St. Clair County, Illinois, United States. As of the 2010 census, the city has a population of 44,478. It is the eighth-most populated city outside of the Chicago Metropolitan Area and the most populated city south of Springfield in the state of Illinois. It is the county...

. Because of the rapid descent of the balloon, Gray parachuted out at 8,000 feet, disqualifying him from recognition by the Fédération Aéronautique InternationaleFédération Aéronautique InternationaleThe Fédération Aéronautique Internationale is the world governing body for air sports and aeronautics and astronautics world records. Its head office is in Lausanne, Switzerland. This includes man-carrying aerospace vehicles from balloons to spacecraft, and unmanned aerial vehicles...

(FAI) - The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and SciencesAcademy of Motion Picture Arts and SciencesThe Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences is a professional honorary organization dedicated to the advancement of the arts and sciences of motion pictures...

, which now bestows the "Academy AwardsAcademy AwardsAn Academy Award, also known as an Oscar, is an accolade bestowed by the American Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences to recognize excellence of professionals in the film industry, including directors, actors, and writers...

" (or "Oscars") for excellence in film, was incorporated. - Died: General Rodolfo Gallegos, Mexican rebel leader who had led the April 19April 1927January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in April 1927:-April 1, 1927 :...

train robbery and massacre, was shot while trying to flee federal authorities.

May 5, 1927 (Thursday)

- French aviators Pierre de Saint-Roman and Herve Mouneyres took off from Saint-Louis, SenegalSaint-Louis, SenegalSaint-Louis, or Ndar as it is called in Wolof, is the capital of Senegal's Saint-Louis Region. Located in the northwest of Senegal, near the mouth of the Senegal River, and 320 km north of Senegal's capital city Dakar, it has a population officially estimated at 176,000 in 2005. Saint-Louis...

to make a transatlantic flightTransatlantic flightTransatlantic flight is the flight of an aircraft across the Atlantic Ocean. A transatlantic flight may proceed east-to-west, originating in Europe or Africa and terminating in North America or South America, or it may go in the reverse direction, west-to-east...

from Africa to South America. The pair never arrived. Wreckage of an airplane believed to be theirs washed ashore in Brazil on July 16, and a year later, a message in a bottleMessage in a bottleA message in a bottle is a form of communication whereby a message is sealed in a container and released into the sea or ocean...

, possibly written by Saint-Roman, was found, suggesting that the plane had ditched in the ocean. - To The LighthouseTo the LighthouseTo the Lighthouse is a novel by Virginia Woolf. A novel set on the Ramsays and their visits to the Isle of Skye in Scotland between 1910 and 1920, it skilfully manipulates temporal and psychological elements....

, by Virginia WoolfVirginia WoolfAdeline Virginia Woolf was an English author, essayist, publisher, and writer of short stories, regarded as one of the foremost modernist literary figures of the twentieth century....

, was first published. - GermanyGermanyGermany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

's Nazi Party, the National Socialists, was banned by police from activities in Berlin's metropolitan area. Soon after, Joseph GoebbelsJoseph GoebbelsPaul Joseph Goebbels was a German politician and Reich Minister of Propaganda in Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1945. As one of Adolf Hitler's closest associates and most devout followers, he was known for his zealous oratory and anti-Semitism...

was banned from speaking anywhere in Prussia.

May 6, 1927 (Friday)

- The first radio broadcasts in TurkeyTurkeyTurkey , known officially as the Republic of Turkey , is a Eurasian country located in Western Asia and in East Thrace in Southeastern Europe...

began, from a station in IstanbulIstanbulIstanbul , historically known as Byzantium and Constantinople , is the largest city of Turkey. Istanbul metropolitan province had 13.26 million people living in it as of December, 2010, which is 18% of Turkey's population and the 3rd largest metropolitan area in Europe after London and...

. Television would be introduced on January 31, 1968. - Dr. Richard Meissner, a German chemist, claimed that he had developed an insulin substitute, which he called "horment" from the islands of Langerhans, which could be taken in tablet form and which would cure diabetes.

- Born: Mary Ellen AveryMary Ellen AveryMary Ellen Avery is an American pediatrician. In the 1950s, Dr. Avery's pioneering research efforts helped lead to the discovery of the main cause of respiratory distress syndrome in premature babies: her identification of surfactant led to the development of replacement therapy for premature...

, American physician who discovered the cause of respiratory distress syndrome and contributed to its treatment and cure; in Camden, NJ

May 7, 1927 (Saturday)

- San Francisco Mayor James Rolph, Jr. decicated the city's municipal airport at Mills Field, selected from nine proposed locations. Greatly expanded, the site was renamed in 1954 as the San Francisco International AirportSan Francisco International AirportSan Francisco International Airport is a major international airport located south of downtown San Francisco, California, United States, near the cities of Millbrae and San Bruno in unincorporated San Mateo County. It is often referred to as SFO...

.

May 8, 1927 (Sunday)

- Captain Charles NungesserCharles NungesserCharles Eugène Jules Marie Nungesser, MC was a French ace pilot and adventurer, best remembered as a rival of Charles Lindbergh...

and his navigator, Captain Francois ColiFrançois ColiFrançois Coli was a French pilot and navigator best known as the flying partner of Charles Nungesser in the doomed attempt to fly the Atlantic Ocean on the aircraft known as The White Bird....

, departed from ParisParisParis is the capital and largest city in France, situated on the river Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region...

at 5:18 am (11:18 pm Saturday in New York) in L'Oiseau Blanc (The White Bird), a Levasseur biplane, in an attempt to make the first nonstop airplane flight Paris and New YorkOrteig PrizeThe Orteig Prize was a $25,000 reward offered on May 19, 1919, by New York hotel owner Raymond Orteig to the first allied aviator to fly non-stop from New York City to Paris or vice-versa. On offer for five years, it attracted no competitors...

. Expected to reach New York the next day, the plane never arrived, and was last seen approaching Cape RaceCape RaceCape Race is a point of land located at the southeastern tip of the Avalon Peninsula on the island of Newfoundland, Canada. Its name is thought to come from the original Portuguese name for this cape, "Raso", or "bare"...

, Newfoundland, at 10:00 am on Monday, with 1,000 miles left of flying The two men were never seen again. - Died: Col. A.E. HumphreysGrant-Humphreys MansionGrant-Humphreys Mansion in Denver, Colorado, was built in 1902, in the Neoclassical style of architecture by Boal and Harnois, for James Benton Grant following his one term as the third Governor of Colorado...

, Denver multimillionaire, accidentally shot himself while packing guns and fishing tackle for a hunting trip.

May 9, 1927 (Monday)

- The Parliament of AustraliaParliament of AustraliaThe Parliament of Australia, also known as the Commonwealth Parliament or Federal Parliament, is the legislative branch of the government of Australia. It is bicameral, largely modelled in the Westminster tradition, but with some influences from the United States Congress...

first convened in CanberraCanberraCanberra is the capital city of Australia. With a population of over 345,000, it is Australia's largest inland city and the eighth-largest city overall. The city is located at the northern end of the Australian Capital Territory , south-west of Sydney, and north-east of Melbourne...

, following relocation of the capital from MelbourneMelbourneMelbourne is the capital and most populous city in the state of Victoria, and the second most populous city in Australia. The Melbourne City Centre is the hub of the greater metropolitan area and the Census statistical division—of which "Melbourne" is the common name. As of June 2009, the greater...

. The Duke of YorkGeorge VI of the United KingdomGeorge VI was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death...

(and future King George VI) opened Parliament after being introduced by Prime Minister Stanley BruceStanley BruceStanley Melbourne Bruce, 1st Viscount Bruce of Melbourne, CH, MC, FRS, PC , was an Australian politician and diplomat, and the eighth Prime Minister of Australia. He was the second Australian granted an hereditary peerage of the United Kingdom, but the first whose peerage was formally created...

. The opening would be described in later years as the Duke's "first real test" of public speaking after working with therapist Lionel LogueLionel LogueLionel George Logue CVO was an Australian speech therapist and stage actor who successfully treated, among others, King George VI, who had a pronounced stammer.-Early life and family:...

to overcome stammering. - Tornadoes swept through the south central U.S., killing 230 people, and over 800 other people in six states. Hardest hit were the towns of Poplar Bluff, MissouriPoplar Bluff, MissouriPoplar Bluff is a city in Butler County located in Southeast Missouri in the United States. It is the county seat of Butler County and is known as "The Gateway to the Ozarks" among other names. As of the 2000 U.S...

, where 93 people died, and Nevada, TexasNevada, TexasNevada is a city in Collin County, Texas, United States. The population was 563 at the 2000 census. First settled in 1835 by John McMinn Stambaugh and named McMinn Chapel, the area was settled by Granville Stinebaugh, who named it after Nevada Territory...

. - A jury in New York convicted Mrs. Ruth SnyderRuth SnyderRuth Brown Snyder was an American murderess. Her execution, in the electric chair at Sing Sing Prison, for the murder of her husband, Albert, was captured in a well-known photograph.-The crime:...

and her accomplice, Henry Judd Gray, of the murder of her husband, Albert Snyder. The two were electrocuted separately in 1928. - Born: Manfred EigenManfred EigenManfred Eigen is a German biophysical chemist who won the 1967 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for work on measuring fast chemical reactions.-Career:...

, German biophysicist, recipient of the 1967 Nobel Prize in ChemistryNobel Prize in ChemistryThe Nobel Prize in Chemistry is awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to scientists in the various fields of chemistry. It is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Alfred Nobel in 1895, awarded for outstanding contributions in chemistry, physics, literature,...

, in BochumBochumBochum is a city in North Rhine-Westphalia, western Germany. It is located in the Ruhr area and is surrounded by the cities of Essen, Gelsenkirchen, Herne, Castrop-Rauxel, Dortmund, Witten and Hattingen.-History:...

; and Leonard MandelLeonard MandelLeonard Mandel was the Lee DuBridge Professor Emeritus of Physics and Optics at the University of Rochester when he died at the age of 73 at his home in Pittsford, New York. He contributed immensely to theoretical and experimental optics...

, German-born American physicist and pioneer in the field of quantum opticsQuantum opticsQuantum optics is a field of research in physics, dealing with the application of quantum mechanics to phenomena involving light and its interactions with matter.- History of quantum optics :...

, in BerlinBerlinBerlin is the capital city of Germany and is one of the 16 states of Germany. With a population of 3.45 million people, Berlin is Germany's largest city. It is the second most populous city proper and the seventh most populous urban area in the European Union...

(d. 2001) - Died: Peggy Porter, daughter of William Sidney "O. Henry" Porter, who had written stories under the pen name of "Miss O. Henry"

May 10, 1927 (Tuesday)

- Sending a pistol by United States mail became illegal as a new law took effect.

- The popular hymn Shall We Gather at the River?Shall We Gather at the River?"Shall We Gather at the River?" is a traditional Christian hymn, written by American poet and gospel music composer Robert Lowry . It was written in 1864....

was recorded for the first time, by the Dixie Sacred Singers - Born: Nayantara SahgalNayantara SahgalNayantara Sahgal is an Indian writer in English. Her fiction deals with India's elite responding to the crises engendered by political change; she was one of the first female Indo-Anglian writers to receive wide recognition...

, Indian female novelist

May 11, 1927 (Wednesday)

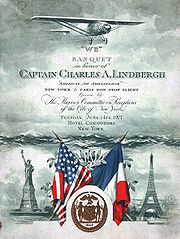

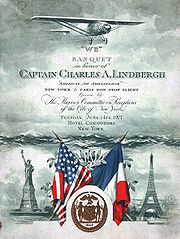

- Charles LindberghCharles LindberghCharles Augustus Lindbergh was an American aviator, author, inventor, explorer, and social activist.Lindbergh, a 25-year-old U.S...

landed in St. Louis, 14 hours after taking off from San Diego the afternoon before. Lindbergh was "the only entrant in the Raymond Orteig $25,000 flight [contest] who plans to make the transatlantic flight alone", and was nicknamed "The Foolish Flyer" as a result. - Born: Mort SahlMort SahlMorton Lyon "Mort" Sahl is a Canadian-born American comedian and actor. He occasionally wrote jokes for speeches delivered by President John F. Kennedy. He was the first comedian to record a live album and the first to perform on college campuses...

, Canadian-born comedian, in MontrealMontrealMontreal is a city in Canada. It is the largest city in the province of Quebec, the second-largest city in Canada and the seventh largest in North America...

; Gene SavoyGene SavoyDouglas Eugene "Gene" Savoy was an American explorer, author, religious leader, and theologian. He served as Head Bishop of the International Community of Christ, Church of the Second Advent from 1971 until his passing...

, American author, explorer, and cleric, in Bellingham, WashingtonBellingham, WashingtonBellingham is the largest city in, and the county seat of, Whatcom County in the U.S. state of Washington. It is the twelfth-largest city in the state. Situated on Bellingham Bay, Bellingham is protected by Lummi Island, Portage Island, and the Lummi Peninsula, and opens onto the Strait of Georgia...

(d. 2009); and Bernard Fox Welsh actor, in Port TalbotPort TalbotPort Talbot is a town in Neath Port Talbot, Wales. It had a population of 35,633 in 2001.-History:Port Talbot grew out of the original small port and market town of Aberafan , which belonged to the medieval Lords of Afan. The area of the parish of Margam lying on the west bank of the lower Afan... - Died: Juan GrisJuan GrisJosé Victoriano González-Pérez , better known as Juan Gris, was a Spanish painter and sculptor who lived and worked in France most of his life...

, Spanish sculptor and painter (b. 1887)

May 12, 1927 (Thursday)

- Under the direction of Scotland Yard, LondonLondonLondon is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

police raided Arcost, Ltd., the office of the Soviet trade delegation. At 4:00 pm, telephone lines were cut and the building was sealed, with the 600 employees detained during a search. Evidence of Russian espionage was found and a break of diplomatic relations followed. - Philip F. Labre applied for a patent for the "grounding receptacle and plug", the three pronged plug still in use today. U.S. Patent No. 1,672,067, was granted on June 5, 1928.

May 13, 1927 (Friday)

- The equity market in GermanyGermanyGermany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

suffered a severe price drop after ReichsbankReichsbankThe Reichsbank was the central bank of Germany from 1876 until 1945. It was founded on 1 January 1876 . The Reichsbank was a privately owned central bank of Prussia, under close control by the Reich government. Its first president was Hermann von Dechend...

President Hjalmar SchachtHjalmar SchachtDr. Hjalmar Horace Greeley Schacht was a German economist, banker, liberal politician, and co-founder of the German Democratic Party. He served as the Currency Commissioner and President of the Reichsbank under the Weimar Republic...

had attempted to stop price speculation. Prices continued to decline following the "Black Friday". - King George V issued a royal proclamation dropping the term "United Kingdom" from his title, referring to himself instead as "Georgius V, Dei Gratia Magane Britanniae, Hiberniae et terrarum transmarinarum quae in ditione iunt Britannica Rex, Fidei Defensor, Indiae Imperator" ("George V, by the Grace of God, of Great Britain, Ireland, and the British Dominions beyond the Seas, King, Defender of the Faith, Emperor of India").

- Born: Herbert RossHerbert RossHerbert Ross was an American film director, producer, choreographer and actor.-Early life and career:Born Herbert David Ross in Brooklyn, New York, he made his stage debut as Third Witch with a touring company of Macbeth in 1942...

, American film director, (d. 2001) and Fred HellermanFred HellermanFred Hellerman, born in Brooklyn, New York and educated at Brooklyn College, is an American folk singer, guitarist, producer and song writer, primarily known as one of the members of The Weavers, together with Pete Seeger, Lee Hays, and Ronnie Gilbert...

, American songwriter, both in BrooklynBrooklynBrooklyn is the most populous of New York City's five boroughs, with nearly 2.6 million residents, and the second-largest in area. Since 1896, Brooklyn has had the same boundaries as Kings County, which is now the most populous county in New York State and the second-most densely populated...

.

May 14, 1927 (Saturday)

- One man was killed and ten others injured when the bleachers at the Baker Bowl in Philadelphia collapsed during a game between the PhilliesPhiladelphia PhilliesThe Philadelphia Phillies are a Major League Baseball team. They are the oldest continuous, one-name, one-city franchise in all of professional American sports, dating to 1883. The Phillies are a member of the Eastern Division of Major League Baseball's National League...

and the visiting St. Louis CardinalsSt. Louis CardinalsThe St. Louis Cardinals are a professional baseball team based in St. Louis, Missouri. They are members of the Central Division in the National League of Major League Baseball. The Cardinals have won eleven World Series championships, the most of any National League team, and second overall only to...

. The Phillies were leading, 12-3, after six innings, and the Cardinals had one out in the 7th, when the right field pavilion seats fell without warning. - The German luxury liner Cap Arcona was launched from the Blohm & Voss shipyard, in HamburgHamburg-History:The first historic name for the city was, according to Claudius Ptolemy's reports, Treva.But the city takes its modern name, Hamburg, from the first permanent building on the site, a castle whose construction was ordered by the Emperor Charlemagne in AD 808...

. The ship was 676 feet long and could carry 1,315 passengers, and made its first voyage on November 19. The ship was sunk on May 3, 1945 by the RAF, with 5,000 concentration camp inmates on board.

May 15, 1927 (Sunday)

- The civil war in NicaraguaNicaraguaNicaragua is the largest country in the Central American American isthmus, bordered by Honduras to the north and Costa Rica to the south. The country is situated between 11 and 14 degrees north of the Equator in the Northern Hemisphere, which places it entirely within the tropics. The Pacific Ocean...

came to an end, with President Adolfo DíazAdolfo DíazAdolfo Díaz Recinos was the President of Nicaragua between 9 May 1911 and 1 January 1917 and between 14 November 1926 and 1 January 1929...

requesting U.S. President Calvin CoolidgeCalvin CoolidgeJohn Calvin Coolidge, Jr. was the 30th President of the United States . A Republican lawyer from Vermont, Coolidge worked his way up the ladder of Massachusetts state politics, eventually becoming governor of that state...

to supervise elections that would be "free, fair, and impartial and not open to fraud or intimidation". With U.S. envoy Henry L. StimsonHenry L. StimsonHenry Lewis Stimson was an American statesman, lawyer and Republican Party politician and spokesman on foreign policy. He twice served as Secretary of War 1911–1913 under Republican William Howard Taft and 1940–1945, under Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt. In the latter role he was a leading hawk...

as the intermediary, Díaz and rebel leader José María Moncada had agreed to terms at TipitapaTipitapaTipitapa is a municipality in the Managua department of Nicaragua.- History :Tipitapa has its origin in a settlement whose first settlers were the Chorotegas who populated the center of Nicaragua and especially the location between two lakes. Over time Chorotegas were divided into two rival gangs,...

, with Díaz to arrange elections following Moncada's troops completing disarmament. The voting took place in October 1928, with Moncada winning the presidency.

May 16, 1927 (Monday)

- Admiral Richard E. Byrd, one of several aviators planning to fly from New York to Paris, told reporters that he would fly no earlier than the middle of the following week, after alerting his elderly mother in a phone conversation. "Byrd Won't Start Across Atlantic for While Yet", Spokane Daily Chronicle, May 16, 1927, p1

- A fireFireFire is the rapid oxidation of a material in the chemical process of combustion, releasing heat, light, and various reaction products. Slower oxidative processes like rusting or digestion are not included by this definition....

ball was witnessed by thousands of spectators in MissouriMissouriMissouri is a US state located in the Midwestern United States, bordered by Iowa, Illinois, Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Kansas and Nebraska. With a 2010 population of 5,988,927, Missouri is the 18th most populous state in the nation and the fifth most populous in the Midwest. It...

and KansasKansasKansas is a US state located in the Midwestern United States. It is named after the Kansas River which flows through it, which in turn was named after the Kansa Native American tribe, which inhabited the area. The tribe's name is often said to mean "people of the wind" or "people of the south...

, streaking across the sky shortly before midnight and then exploding near the General Hospital on the south side of Kansas City, MissouriKansas City, MissouriKansas City, Missouri is the largest city in the U.S. state of Missouri and is the anchor city of the Kansas City Metropolitan Area, the second largest metropolitan area in Missouri. It encompasses in parts of Jackson, Clay, Cass, and Platte counties...

.

May 17, 1927 (Tuesday)

- The planned transatlantic flightTransatlantic flightTransatlantic flight is the flight of an aircraft across the Atlantic Ocean. A transatlantic flight may proceed east-to-west, originating in Europe or Africa and terminating in North America or South America, or it may go in the reverse direction, west-to-east...

of Lloyd W. Bertaud and Clarence D. Chamberlin, who were racing against Lindbergh and Byrd to become the first persons to fly an airplane from New York to Paris, was cancelled after an argument between the two fliers and their chief backer, Charles A. Levine. - The town of Melville, LouisianaMelville, LouisianaMelville is a town in St. Landry Parish, Louisiana, United States. The population was 1,376 at the 2000 census. It is part of the Opelousas–Eunice Micropolitan Statistical Area.-Geography:Melville is located at ....

, population 1,028 was destroyed when a levee on the Atchafalaya RiverAtchafalaya RiverThe Atchafalaya River is a distributary of the Mississippi River and Red River in south central Louisiana in the United States. It flows south, just west of the Mississippi River....

gave way. - Died: Major Harold GeigerHarold GeigerMajor Harold C. Geiger , born in East Orange, New Jersey, was a pioneer in US military aviation and ballooning who was killed in an airplane crash in 1927...

, Army aviation pioneer, in a plane crash; and Sam Bernard, 64, American comedian

May 18, 1927 (Wednesday)

- Bath School disasterBath School disasterThe Bath School disaster is the name given to three bombings in Bath Township, Michigan, on May 18, 1927, which killed 38 elementary school children, two teachers, four other adults and the bomber himself; at least 58 people were injured. Most of the victims were children in the second to sixth...

: At Bath TownshipBath Township, MichiganBath Charter Township is a charter township of Clinton County in the U.S. state of Michigan. As of the 2010 census, the township population was 11,598, an increase from 7,541 in 2000...

, MichiganMichiganMichigan is a U.S. state located in the Great Lakes Region of the United States of America. The name Michigan is the French form of the Ojibwa word mishigamaa, meaning "large water" or "large lake"....

, 36 schoolchildren and 5 adults were killed by dynamite charges that had been placed underneath the local school. Andrew Kehoe, who had been treasurer of the township school board, had planted the bombs under the north wing, which housed 110 pupils and instructors, and the south wing, with 150 more. On the morning of the last day of classes, Kehoe set a two minute timer and drove away, and at 9:43 a.m., the explosives under the north wing detonated. A short circuit in one of the wires prevented the destruction of the south wing. Kehoe, who had murdered his wife earlier, killed himself and three other people half an hour later, detonating a bomb while sitting in his car.

May 19, 1927 (Thursday)

- At the German city of KasselKasselKassel is a town located on the Fulda River in northern Hesse, Germany. It is the administrative seat of the Kassel Regierungsbezirk and the Kreis of the same name and has approximately 195,000 inhabitants.- History :...

, nine people were killed and 11 seriously injured after a 9-year-old boy released the emergency brake of a crowded streetcar. - Died: Maurice Mouvet, 38, American dancer who attained fame in North America and Europe as "Maurice"

May 20, 1927 (Friday)

- Charles LindberghCharles LindberghCharles Augustus Lindbergh was an American aviator, author, inventor, explorer, and social activist.Lindbergh, a 25-year-old U.S...

took off from Roosevelt Field on New York's Long Island at 7:52 a.m. in his airplane, the Spirit of St. Louis, bound for Paris. With the plane carrying a 5,150 pound load, he barely cleared a string of telegraph wires. Lindbergh told a police chief, "When I enter that cockpit, it's like going into the death chamber. When I get to Paris, it will be like getting a pardon from the governor. - The independence of the Kingdom of Nejd and Hejaz, with the Sultan Ibn SaudIbn Saud of Saudi ArabiaKing Abdul-Aziz of Saudi Arabia was the first monarch of the Third Saudi State known as Saudi Arabia. He was commonly referred to as Ibn Saud....

as monarch, was recognized by the United KingdomUnited KingdomThe United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

in the Treaty of Jeddah signed by representatives of the kings of both nations. On September 23, 1932, the nation would be renamed Saudi ArabiaSaudi ArabiaThe Kingdom of Saudi Arabia , commonly known in British English as Saudi Arabia and in Arabic as as-Sa‘ūdiyyah , is the largest state in Western Asia by land area, constituting the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula, and the second-largest in the Arab World...

by King Ibn Saud. - J. Willard MarriottJ. Willard MarriottJohn Willard Marriott was an American entrepreneur and businessman. He was the founder of the Marriott Corporation , the parent company of one of the world's largest hospitality, hotel chains, and food services companies. The Marriott company rose from a small root beer stand in Washington D.C...

started his first business, a 9-stool A&W root beer franchise located at 3128 14th Street, NW in Washington DC. Marriott would eventually found the worldwide Marriott Hotel chain. - The Boeing 40ABoeing 40A- External links :* Retrieved June 17, 2006.* * **...

, first passenger airliner built by the Boeing company, was flown for the first time. - Born: Bud GrantBud GrantHarry Peter "Bud" Grant, Jr is the former longtime American football head coach of the Minnesota Vikings of the National Football League for eighteen seasons. Grant was the second and fourth head coach of the team...

, American and Canadian pro football coach, in Superior, WisconsinSuperior, WisconsinSuperior is a city in and the county seat of Douglas County, Wisconsin, United States. The population was 26,960 at the 2010 census. Located at the junction of U.S. Highways 2 and 53, it is north of and adjacent to both the Village of Superior and the Town of Superior.Superior is at the western...

. - Died: Eduard BrucknerEduard BrucknerEduard Brückner was an Austrian geographer, meteorologist, glaciologist and climate scientist.He was born in Jena, the son of the Baltic-German historian Alexander Brückner and Lucie Schiele. After an education at the Karlsruhe gymnasium, beginning in 1881 he studied meteorology and physics at the...

, 64, German geographer and glaciologist

May 21, 1927 (Saturday)

- Charles LindberghCharles LindberghCharles Augustus Lindbergh was an American aviator, author, inventor, explorer, and social activist.Lindbergh, a 25-year-old U.S...

became the first man to complete a non-stop trans-Atlantic airplane flight, from New YorkNew YorkNew York is a state in the Northeastern region of the United States. It is the nation's third most populous state. New York is bordered by New Jersey and Pennsylvania to the south, and by Connecticut, Massachusetts and Vermont to the east...

to ParisParisParis is the capital and largest city in France, situated on the river Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region...

. He landed his monoplane, the Spirit of St. LouisSpirit of St. LouisThe Spirit of St. Louis is the custom-built, single engine, single-seat monoplane that was flown solo by Charles Lindbergh on May 20–21, 1927, on the first non-stop flight from New York to Paris for which Lindbergh won the $25,000 Orteig Prize.Lindbergh took off in the Spirit from Roosevelt...

, at Le BourgetLe BourgetLe Bourget is a commune in the northeastern suburbs of Paris, France. It is located from the center of Paris.A very small part of Le Bourget airport lies on the territory of the commune of Le Bourget, which nonetheless gave its name to the airport. Most of the airport lies on the territory of the...

airfield near Paris at 10:21 p.m. local time (5:21 pm in New York), 33 hours and 29 minutes after taking off from New YorkNew YorkNew York is a state in the Northeastern region of the United States. It is the nation's third most populous state. New York is bordered by New Jersey and Pennsylvania to the south, and by Connecticut, Massachusetts and Vermont to the east...

. Lindbergh won the $25,000 Orteig PrizeOrteig PrizeThe Orteig Prize was a $25,000 reward offered on May 19, 1919, by New York hotel owner Raymond Orteig to the first allied aviator to fly non-stop from New York City to Paris or vice-versa. On offer for five years, it attracted no competitors...

and a lifetime of fame and fortune.

May 22, 1927 (Sunday)

- Carlos Ibáñez del CampoCarlos Ibáñez del CampoGeneral Carlos Ibáñez del Campo was a Chilean Army officer and political figure. He served as dictator between 1927 and 1931 and as constitutional President from 1952 to 1958.- The coups of 1924 and 1925 :...

, who had been acting President since May 10, was electedChilean presidential election, 1927A presidential election was held in Chile on May 22, 1927. Following President Emiliano Figueroa's resignation on April 7, 1927, Interior minister Carlos Ibáñez del Campo took his place as Vice President and called for elections. He competed with communist Elías Lafertte.-Results:Source:...

the 20th President of ChilePresident of ChileThe President of the Republic of Chile is both the head of state and the head of government of the Republic of Chile. The President is responsible of the government and state administration...

, receiving a reported 98% (223,741 out of 226,745 votes) - Born: George A. Olah, Hungarian-born chemist, Nobel Prize in ChemistryNobel Prize in ChemistryThe Nobel Prize in Chemistry is awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to scientists in the various fields of chemistry. It is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Alfred Nobel in 1895, awarded for outstanding contributions in chemistry, physics, literature,...

, in BudapestBudapestBudapest is the capital of Hungary. As the largest city of Hungary, it is the country's principal political, cultural, commercial, industrial, and transportation centre. In 2011, Budapest had 1,733,685 inhabitants, down from its 1989 peak of 2,113,645 due to suburbanization. The Budapest Commuter...

; and Quinn MartinQuinn MartinQuinn Martin was one of the most successful American television producers. He had at least one television series running in prime time for 21 straight years , an industry record.-Early life:...

, American television producer, in Berkeley, CA

May 23, 1927 (Monday)

- 1927 Gulang earthquake1927 Gulang earthquakeThe 1927 Gulang earthquake occurred at 6:32 a.m. on 22 May . This 7.6 magnitude event had an epicenter near Gulang, Gansu in China. There were more than 40,900 casualties. It was felt up to 700 km away.-Geology:...

: Striking at 6:32 in the morning local time (2232 UTC on May 21), an earthquake of magnitude 8.0 rocked the Gansu province of ChinaChinaChinese civilization may refer to:* China for more general discussion of the country.* Chinese culture* Greater China, the transnational community of ethnic Chinese.* History of China* Sinosphere, the area historically affected by Chinese culture...

and killed as many as 200,000 people.

May 24, 1927 (Tuesday)

- British Prime Minister Stanley BaldwinStanley BaldwinStanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley, KG, PC was a British Conservative politician, who dominated the government in his country between the two world wars...

told the House of Commons that the United KingdomUnited KingdomThe United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

intended to terminate relations with the Soviet UnionSoviet UnionThe Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

because of espionageEspionageEspionage or spying involves an individual obtaining information that is considered secret or confidential without the permission of the holder of the information. Espionage is inherently clandestine, lest the legitimate holder of the information change plans or take other countermeasures once it...

by Russian diplomats Commons approved the move three days later, by a 357-111 vote.

May 25, 1927 (Wednesday)

- U.S. Army Lt. James H. Doolittle became the first person to perform an "outside loop", a feat that aviators had been attempting since 1912, with at least two getting killed in the attempt. Doolittle, who would later become more famous as Lt. Gen. Jimmy Doolittle for a daring raid on Tokyo, climbed to 8,000 feet over Dayton, OhioDayton, OhioDayton is the 6th largest city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Montgomery County, the fifth most populous county in the state. The population was 141,527 at the 2010 census. The Dayton Metropolitan Statistical Area had a population of 841,502 in the 2010 census...

, then turned the nose of his plane downward, being upside down at 6,000 feet, before flying back upward to his original altitude and completing the circle. - Born: Robert LudlumRobert LudlumRobert Ludlum was an American author of 23 thriller novels. The number of his books in print is estimated between 290–500 million copies. They have been published in 33 languages and 40 countries. Ludlum also published books under the pseudonyms Jonathan Ryder and Michael Shepherd.-Life and...

, American novelist who wrote The Bourne Identity and its sequels, in New York CityNew York CityNew York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

(d. 2001) - Died: St. Cristobal Magallanes, 57, and St. Agustin Caloca, were both shot by a firing squad at Colotitlan, Jalisco state, and later canonized.

May 26, 1927 (Thursday)

- U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Andrew W. MellonAndrew W. MellonAndrew William Mellon was an American banker, industrialist, philanthropist, art collector and Secretary of the Treasury from March 4, 1921 until February 12, 1932.-Early life:...

announced that he had approved a change in the size of United States currency in order to save printing costs. The bills would be 1 1/3 inches shorter in length and 3/4" lower in width, with the first new bills to appear in spring of 1928. In addition, consistent images were selected for the one dollar bill (George Washington) and the two dollar bill (Thomas Jefferson). Mellon commented that, "in time, each denomination will be immediately recognized from the picture it bears".

May 27, 1927 (Friday)

- The United KingdomUnited KingdomThe United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

officially terminated diplomatic relations with the Soviet UnionSoviet UnionThe Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

. A note from Foreign Secretary Neville ChamberlainNeville ChamberlainArthur Neville Chamberlain FRS was a British Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. Chamberlain is best known for his appeasement foreign policy, and in particular for his signing of the Munich Agreement in 1938, conceding the...

, delivered to the Soviet legation at Chesham House in London, directed the chargé d'affaires and his staff to leave the country within ten days. " - Born: Ralph CarmichaelRalph CarmichaelRalph Carmichael is a composer and arranger of both secular pop music and contemporary Christian music, being regarded as one of the pioneers of the latter genre...

, American composer and arranger; Heinrich HollandHeinrich HollandHeinrich Holland is professor emeritus in the Earth and Planetary Sciences department of Harvard University. He has made major contributions to in the understanding of the Earth's geochemistry, especially large-scale geochemical and biogeochemical cycles. He has also contributed to the field of...

, German biochemist, in MannheimMannheimMannheim is a city in southwestern Germany. With about 315,000 inhabitants, Mannheim is the second-largest city in the Bundesland of Baden-Württemberg, following the capital city of Stuttgart....

May 28, 1927 (Saturday)

- The sport of greyhound racingGreyhound racingGreyhound racing is the sport of racing greyhounds. The dogs chase a lure on a track until they arrive at the finish line. The one that arrives first is the winner....

was introduced to AustraliaAustraliaAustralia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

, with spectators there seeing for the first time the "mechanical rabbit" that raced ahead of the fleet canines.

May 29, 1927 (Sunday)

- An Italian record crowd of 60,000 fans, including Fascist dictator Benito MussoliniBenito MussoliniBenito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini was an Italian politician who led the National Fascist Party and is credited with being one of the key figures in the creation of Fascism....

, King Victor Emmanuel III, and Spain's Crown Prince Alfonso turned out for the first soccer football game in the new Stadio LittorialeStadio Renato Dall'AraStadio Renato Dall'Ara is a multi-purpose stadium in Bologna, Italy. It is currently used mostly for football matches and the home of Bologna F.C. 1909. The stadium was built in 1927 and holds 38,279...

in BolognaBolognaBologna is the capital city of Emilia-Romagna, in the Po Valley of Northern Italy. The city lies between the Po River and the Apennine Mountains, more specifically, between the Reno River and the Savena River. Bologna is a lively and cosmopolitan Italian college city, with spectacular history,...

to watch ItalyItaly national football teamThe Italy National Football Team , represents Italy in association football and is controlled by the Italian Football Federation , the governing body for football in Italy. Italy is the second most successful national team in the history of the World Cup having won four titles , just one fewer than...

defeat Spain 2-0 in a friendly match. - Died: Francis Grierson, American author

May 30, 1927 (Monday)

- Jimmy CooneyJimmy Cooney (1920s shortstop)James Edward Cooney , nicknamed "Scoops," was an American shortstop in Major League Baseball who played for six different teams between and . Listed at 5' 11", 160 lb., Cooney batted and threw right-handed. His father Jimmy Sr...

of the Chicago CubsChicago CubsThe Chicago Cubs are a professional baseball team located in Chicago, Illinois. They are members of the Central Division of Major League Baseball's National League. They are one of two Major League clubs based in Chicago . The Cubs are also one of the two remaining charter members of the National...

made an unassisted triple playUnassisted triple playIn baseball, an unassisted triple play occurs when a defensive player makes all three putouts by himself in one continuous play, without any teammates touching the ball . In Major League Baseball , it is one of the rarest of individual feats, along with hitting four home runs in one game and the...

in a game against the Pittsburgh PiratesPittsburgh PiratesThe Pittsburgh Pirates are a Major League Baseball club based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. They play in the Central Division of the National League, and are five-time World Series Champions...

. The very next day, Johnny NeunJohnny NeunJohn Henry Neun was an American first baseman for the Detroit Tigers and the Boston Braves from 1925 to 1931.-Career:...

of the Detroit TigersDetroit TigersThe Detroit Tigers are a Major League Baseball team located in Detroit, Michigan. One of the American League's eight charter franchises, the club was founded in Detroit in as part of the Western League. The Tigers have won four World Series championships and have won the American League pennant...

duplicated the feat. Only five players had accomplished the feat before Cooney and Neun; it didn't happen again until July 30, 1968. Cooney himself had been tagged out in the last on on May 7, 1925. - George SoudersGeorge SoudersGeorge Souders won the 1927 Indianapolis 500.Born in Lafayette, Indiana, George Souders led the last 51 laps of the 1927 race after starting in 22nd position as a race rookie.-Indy 500 results:-External links:...

, a 24-year-old driving his first major auto race ever, won the 15th annual Indianapolis 500Indianapolis 500The Indianapolis 500-Mile Race, also known as the Indianapolis 500, the 500 Miles at Indianapolis, the Indy 500 or The 500, is an American automobile race, held annually, typically on the last weekend in May at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway in Speedway, Indiana... - Born: Clint WalkerClint WalkerNorman Eugene Walker, known as Clint Walker , is an American actor best known for his cowboy role as "Cheyenne Bodie" in the TV Western series, Cheyenne.-Life and career:...

, American TV actor (Cheyenne), in Hartford, IllinoisHartford, IllinoisHartford is a village in Madison County, Illinois, near the mouth of the Missouri River. The population was 1,545 at the 2000 census. Lewis and Clark spent the winter of 1803-1804 here, near what has been designated the Lewis and Clark State Historic Site....

May 31, 1927 (Tuesday)

- The 15,007,033rd and last Ford Model TFord Model TThe Ford Model T is an automobile that was produced by Henry Ford's Ford Motor Company from September 1908 to May 1927...

, after a 19 year run that began in 1908. Henry FordHenry FordHenry Ford was an American industrialist, the founder of the Ford Motor Company, and sponsor of the development of the assembly line technique of mass production. His introduction of the Model T automobile revolutionized transportation and American industry...

had announced the week before that production would halt at the end of the month, that 24 plants would close and 10,000 employees would be laid off. Ford car dealers across the United States all received a telegram on May 26, the day the 15,000,000th Model T was driven by Ford out of the factory in Highland Park, MichiganHighland Park, Michigan- Geography :According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of , all land.- Demographics :As of the census of 2000, there were 16,746 people, 6,199 households, and 3,521 families residing in the city. The population density was 5,622.9 per square mile . There were 7,249...

, that the factories were being retooled to make way for the new Model A, which would be introduced in December. The Model T would hold the record for the most popular model of car in history until February 17, 1972February 1972January – February – March – April – May – June – July – August – September – October – November – DecemberThe following events occurred in February 1972.-February 1, 1972 :...

, when the 15,007,034th Volkswagen Beetle was produced.