History of Austria

Encyclopedia

The history of Austria covers the history of the current country

of Austria

and predecessor states, from the Iron Age, through to a sovereign state, annexation by the German Third Reich, partition after the Second World War and later developments until the present day. More information can be found in history of Europe

.

, one of the first agrarian cultures in Europe.

Ötzi the Iceman

, a well-preserved mummy of a man frozen in Austrian Alps, is dated around 3300 BC.

Noricum

Noricum

, in ancient

geography

, was a Celtic kingdom (perhaps better described as a federation of, by tradition, twelve tribes) stretching over the area of today's Austria

and a part of Slovenia

. It became a province

of the Roman Empire

. It was bounded on the north by the Danube

, on the west by Raetia

and Vindelicia

, on the east and southeast by Pannonia

, on the south by Region 10, Venetia et Histria.

, the Slavic

tribe of the Carantanians migrated into the Alps

in the wake of the expansion of their Avar

overlords during the 7th century, mixed with the Celto-Romanic population, and established the realm of Carantania, which covered much of eastern and central Austrian territory. In the meantime, the Germanic tribe of the Bavarians had developed in the 5th and 6th century in the west of the country and in Bavaria

, while what is today Vorarlberg

had been settled by the Alemans. Those groups mixed with the Rhaeto-Romanic

population and pushed it up into the mountains.

Carantania, under pressure of the Avars, lost its independence to Bavaria

in 745 and became a margraviate. During the following centuries, Bavarian settlers went down the Danube and up the Alps, a process through which Austria was to become the mostly German-speaking country it is today.

The Bavarians themselves came under the overlordship of the Carolingian

Franks

and subsequently became a duchy

of the Holy Roman Empire

. Duke Tassilo III

, who wanted to maintain Bavarian independence, was defeated and displaced by Charlemagne

in 789. An eastern march (military borderland), the Avar March

, was established in Charlemagne's time, but it was overrun by the Hungarians in 909.

After the defeat of the Hungarians by Emperor Otto the Great in the Battle of Lechfeld

After the defeat of the Hungarians by Emperor Otto the Great in the Battle of Lechfeld

(955), new marches were established in what is today Austria. The one known as the marchia orientalis was to become the core territory of Austria and was given to Leopold of Babenberg in 976 after the revolt of Henry II, Duke of Bavaria

.

The marches

were overseen by a comes or dux as appointed by the emperor. These titles are usually translated as count or duke, but these terms conveyed very different meanings in the Early Middle Ages

, so the Latin

versions are to be preferred. In lumbardi-speaking countries, the title was eventually regularized to margrave

(German: markgraf) i.e. "count of the mark".

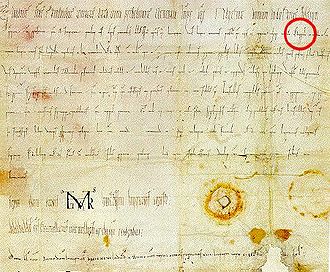

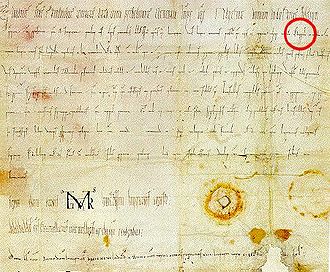

The first recorded instance of the name Austria appeared in 996, written as Ostarrîchi

, referring to the territory of the Babenberg March. The term Ostmark

is not historically certain and appears to be a translation of marchia orientalis that came up only much later.

The following centuries were characterized first by the settlement of the country, when forests were cleared and towns and monasteries were founded. In 1156 the Privilegium Minus

elevated Austria to the status of a duchy. In 1192, the Babenbergs also acquired the Duchy of Styria through the Georgenberg Pact

. At that time, the Babenberg Dukes came to be one of the most influential ruling families in the region, peaking in the reign of Leopold VI (1198–1230).

However, with the slaughter of his son Frederick II in 1246, the line went extinct, which resulted in the interregnum

, a period of several decades during which the status of the country was disputed. Otakar II Přemysl of Bohemia

effectively controlled the duchies of Austria, Styria and Carinthia. His reign came to an end with his defeat in the battle of Dürnkrut and Jedenspeigen

at the hand of Rudolf of Habsburg in 1278.

Following the extinction of the Babenbergs in the 13th century, Austria came briefly under the rule of the Czech

King Ottokar II of Bohemia

. Contesting the election of Rudolf I of Habsburg as emperor, Ottokar was defeated and killed by Rudolf, who took Austria with the assistance of King Ladislaus IV of Hungary.

Emperor Rudolf I of Habsburg gave Austria to his sons in 1278. Austria was ruled by the Habsburgs for the next 640 years. In the 14th and 15th centuries, the Habsburgs began to accumulate other provinces in the vicinity of the Duchy of Austria, which remained a small territory along the Danube, and Styria, which they had acquired from Ottokar along with Austria. Carinthia and Carniola

Emperor Rudolf I of Habsburg gave Austria to his sons in 1278. Austria was ruled by the Habsburgs for the next 640 years. In the 14th and 15th centuries, the Habsburgs began to accumulate other provinces in the vicinity of the Duchy of Austria, which remained a small territory along the Danube, and Styria, which they had acquired from Ottokar along with Austria. Carinthia and Carniola

came under Habsburg rule in 1335, Tyrol

in 1363. These provinces, together, became known as the Habsburg Hereditary Lands, although they were sometimes all lumped together simply as Austria.

Following the notable but short reign of Rudolf IV (the first to claim the title of Archduke of Austria), his brothers Albert III and Leopold III split the realms in the Treaty of Neuberg

in 1379. Albert retained Austria proper, while Leopold took the remaining territories. In 1402, there was another split in the Leopoldian line

, when Ernest the Iron took Inner Austria

(Styria, Carinthia and Carniola) and Frederick IV became ruler of Tyrol and Further Austria

. The territories were only reunified by Ernest's son Frederick V

(Frederick III as Holy Roman Emperor), when the Albertinian line

(1457) and the Elder Tyrolean line (1490) had become extinct.

In 1438, Duke Albert V of Austria was chosen as the successor to his father-in-law, Emperor Sigismund. Although Albert himself only reigned for a year, from then on, every emperor was a Habsburg, with only one exception. The Habsburgs began also to accumulate lands far from the Hereditary Lands. In 1477, the Archduke Maximilian

, only son of Emperor Frederick III

, married the heiress of Burgundy

, thus acquiring most of the Low Countries

for the family. His son Philip the Fair

married the heiress of Castile and Aragon, and thus acquired Spain and its Italian, African, and New World appendages for the Habsburgs. The Habsburgs' hereditary territories, however, were soon separated from this enormous empire when, in 1520, Emperor Charles V left them to the rule of his brother, Ferdinand

.

In 1526, following the Battle of Mohács

In 1526, following the Battle of Mohács

, in which Ferdinand's brother-in-law Louis II, King of Hungary and Bohemia, was killed, Ferdinand expanded his territories, bringing Bohemia and that part of Hungary not occupied by the Ottomans under his rule. Habsburg expansion into Hungary, however, led to frequent conflicts with the Turks, particularly the so-called Long War

of 1593 to 1606.

Austria and the other Habsburg hereditary provinces (and Hungary and Bohemia, as well) were much affected by the Reformation. Although the Habsburg rulers themselves remained Catholic, the provinces themselves largely converted to Lutheranism, which Ferdinand I and his successors, Maximilian II

, Rudolf II

, and Mathias largely tolerated.

In the late 16th century, however, the Counter-Reformation and the Society of Jesus

began to make its influence felt, and the Jesuit-educated

Archduke Ferdinand of Austria

, who ruled over Styria, Carinthia

, and Carniola

before becoming Holy Roman Emperor, was energetic in suppressing heresy in the provinces which he ruled.

, as he became known, embarked on an energetic attempt to re-Catholicize not only the Hereditary Provinces, but Bohemia and Habsburg Hungary as well as most of Protestant Europe within the Holy Roman Empire. Outside his lands, his reputation for strong headed uncompromising intolerance had triggered the Thirty Years' War

in May of 1618 in the polarizing first phase, known as the Revolt in Bohemia. After several initial reverses, he became accommodating but as the Catholics turned things around and began to enjoy a long string of successes at arms he set forth the Edict of Restitution

in 1629 vastly complicating the politics of settlement negotiations and prolonging the rest of the war; encouraged by the mid-war successes, he became even more forceful leading to infamies by his armies such as the Sack of Magdeburg

.

His forced conversions or evictions carried out in the midst of the Thirty Years' War

, which with the later general success of the Protestants therefore had greatly negative consequences for Habsburg control of the Holy Roman Empire itself, while these campaigns within the Habsburg hereditary lands were largely successful in religiously purifying his demesnes, leaving the Austrian Emperors thereafter with much greater control within their hereditary power base— although Hungary was never successfully re-Catholicized—but one much reduced in population and economic might while less vigorous and weakened as a nation-state

.

In terms of human costs, the Thirty Years' war

s many economic, social, and population dislocations caused by the hardline methods adopted by Ferdinand's strict counter-reformation measures and almost continual employment of mercenary field armies contributed significantly to the loss of life and tragic depopulation of all the German states, during a war which some estimates put the civilian loss of life as high as fifty-percent overall. Studies mostly cite the causes of death due to starvation or as caused (ultimately by the lack-of-food induced) weakening of resistance to endemic diseases which repeatedly reached epidemic proportions amongst the general Central European population—the German states were the battle ground and staging areas for the largest mercenary armies theretofore, and the armies foraged amongst the many provinces stealing the food of those people forced onto the roads as refugees, or still on the lands, regardless of their faith and allegiances. Both townsmen and farmers were repeatedly ravaged and victimized by the armies on both sides leaving little for the populations already stressed by the refugees from the war or fleeing the Catholic counter-reformation repressions under Ferdinand's governance.

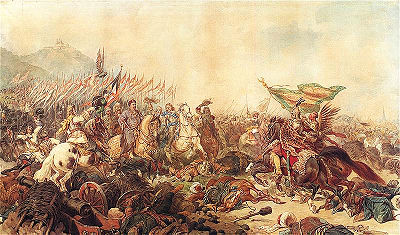

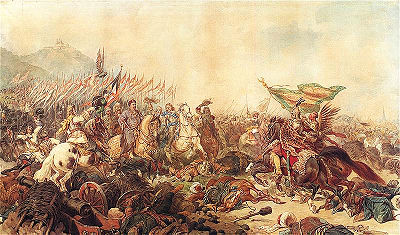

in 1683 led by King of Poland John III Sobieski

, a series of campaigns resulted in the return of all of Hungary to Austrian control by the Treaty of Carlowitz in 1699. At the same time, Austria was becoming more involved in competition with France in Western Europe, with Austria fighting the French in the Third Dutch War (1672–1679), the War of the League of Augsburg (1688–1697) and finally the War of the Spanish Succession

(1701–1714), in which the French and Austrians (along with their British, Dutch and Catalonian allies) fought over the inheritance of the vast territories of the Spanish Habsburgs. Although the French secured control of Spain and its colonies for a grandson of Louis XIV

, the Austrians also ended up making significant gains in Western Europe, including the former Spanish Netherlands (now called the Austrian Netherlands, including most of modern Belgium), the Duchy of Milan

in Northern Italy, and Naples and Sardinia in Southern Italy. (The latter was traded for Sicily in 1720).

The later part of the reign of Emperor Charles VI (1711–1740) saw Austria relinquish many of these fairly impressive gains, largely due to Charles's apprehensions at the imminent extinction of the House of Habsburg. Charles was willing to offer concrete advantages in territory and authority in exchange for other powers' worthless recognitions of the Pragmatic Sanction

The later part of the reign of Emperor Charles VI (1711–1740) saw Austria relinquish many of these fairly impressive gains, largely due to Charles's apprehensions at the imminent extinction of the House of Habsburg. Charles was willing to offer concrete advantages in territory and authority in exchange for other powers' worthless recognitions of the Pragmatic Sanction

that made his daughter Maria Theresa

his heir. The most notable instance of this was in the War of the Polish Succession

whose settlement saw Austria cede Naples and Sicily to the Spanish Infant Don Carlos

in exchange for the tiny Duchy of Parma

and Spain and France's adherence to the Pragmatic Sanction. The latter years of Charles's reign (1736–1739) also saw an unsuccessful war against the Turks, which resulted in the Austrian loss of Belgrade and other border territories.

And, as many had anticipated, when Charles died in 1740, all those assurances from the other powers proved of little worth to Maria Theresa. The peace was initially broken by King Frederick II of Prussia

, who invaded Silesia

. Soon other powers began to exploit Austria's weakness. The Elector of Bavaria claimed the inheritance to the hereditary lands and Bohemia, and was supported by the King of France, who desired the Austrian Netherlands. The Spanish and Sardinians hoped to gain territory in Italy, and the Saxons hoped to gain territory to connect Saxony with the Elector's Polish Kingdom. Austria's allies—Britain, Holland, and Russia, were all wary of getting involved in the conflict. Thus began the War of the Austrian Succession

(1740–1748), one of the more confusing and less eventful wars of European history, which ultimately saw Austria holding its own, despite the permanent loss of most of Silesia to the Prussians. In 1745, following the reign of the Bavaria

n Elector

as Emperor Charles VII

, Maria Theresa's husband Francis of Lorraine

, Grand Duke of Tuscany, was elected Emperor, restoring control of that position to the Habsburgs (or, rather, to the new composite house of Habsburg-Lorraine).

For the eight years following the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle

that ended the War of the Austrian Succession, Maria Theresa plotted revenge on the Prussians. The British and Dutch allies who had proved so reluctant to help her in her time of need were dropped in favour of the French in the so-called Reversal of Alliances

of 1756. That same year, war once again erupted on the continent as Frederick, fearing encirclement, launched a pre-emptive invasion of Saxony. The Seven Years' War

, too, was indecisive, and saw Prussia holding onto Silesia, despite Russia, France, and Austria all combining against him, and with only Hanover as a significant ally on land.

The end of the war saw Austria, exhausted, continuing the alliance with France (cemented in 1770 with the marriage of Maria Theresa's daughter Archduchess Maria Antonietta to the Dauphin

), but also facing a dangerous situation in Central Europe, faced with the alliance of Frederick the Great of Prussia

and Catherine the Great

of Russia. The Russo-Turkish War of 1768–1774 caused a serious crisis in east-central Europe, with Prussia and Austria demanding compensation for Russia's gains in the Balkans, ultimately leading to the First Partition of Poland

in 1772, in which Maria Theresa took Galicia

from Austria's traditional ally.

Over the next several years, Austro-Russian relations began to improve. When the War of Bavarian Succession

erupted between Austria and Prussia in 1777 following the extinction of the Bavarian line of the Wittelsbach

dynasty, Russia refused to support its ally, and the war was ended, after almost no bloodshed, on May 13, 1779 when Russian and French mediators at the Congress of Teschen negotiated an end to the war. In the agreement Austria receive the Innviertel

from Bavaria.

On Maria Theresa's death in 1780, she was succeeded by her son Joseph II

On Maria Theresa's death in 1780, she was succeeded by her son Joseph II

, already Holy Roman Emperor

since Francis I's death in 1765. A reformer herself, Maria Theresa always acted with a cautious respect for the conservatism of the political and social elites and the strength of local traditions. Her cautious approach repelled Joseph, who always sought the decisive, dramatic intervention to impose the one best solution, regardless of traditions or political opposition. He was the archetypical embodiment of The Enlightenment spirit of the 18th-century reforming monarchs known as the "enlightened despots"

. Joseph and his mother were typically at odds on policy, and their quarrels were usually mediated by the chancellor, Prince Wenzel Anton von Kaunitz

(1711–94), who served nearly 40 years as the principal minister to Maria Theresa and Joseph. When Maria Theresa died in 1780, Joseph became the absolute ruler over the most extensive realm of Central Europe. There was no parliament to deal with. Joseph was always positive that the rule of reason, as propounded in the Enlightenment, would produce the best possible results in the shortest time. He issued edicts—6,000 in all, plus 11,000 new laws designed to regulate and reorder every aspect of the empire. The spirit was benevolent and paternal. He intended to make his people happy, but strictly in accordance with his own criteria.

"Josephism," as his policies were called, is notable for the very wide range of reforms designed to modernize the creaky empire in an era when France and Prussia were rapidly upgrading. Josephism elicited grudging compliance at best, and more often vehement opposition from all sectors in every part of his empire. Failure characterized most of his projects. Joseph set about building a rational, centralized, and uniform government for his diverse lands, a pyramid with himself as supreme autocrat. He expected government servants to all be dedicated agents of Josephism and selected them without favor for class or ethnic origins; promotion was solely by merit. To impose uniformity, he made German the compulsory language of official business throughout the Empire. The Hungarian assembly was stripped of its prerogatives, and not even called together

As privy finance minister, Count Karl von Zinzendorf

(1739–1813) introduced a uniform system of accounting for state revenues, expenditures, and debts of the territories of the Austrian crown. Austria was more successful than France in meeting regular expenditures and in gaining credit. However, the events of Joseph II's last years also suggest that the government was financially vulnerable to the European wars that ensued after 1792. Joseph reformed the traditional legal system, abolished brutal punishments and the death penalty in most instances, and imposed the principle of complete equality of treatment for all offenders. He ended censorship of the press and theatre.

In 1781-82 he extended full legal freedom to serfs. Rentals paid by peasants were to be regulated by imperial (not local) officials and taxes were levied upon all income derived from land. The landlords saw a grave threat to their status and incomes, and eventually reversed the policy. In Hungary and Transylvania, the resistance of the landed nobility was so great that Joseph compromised with halfway measures—one of the few times he backed down. After the great peasant revolt of Horea, 1784–85, however, the emperor imposed his will by fiat. His Imperial Patent of 1785 abolished serfdom but did not give the peasants ownership of the land or freedom from dues owed to the landowning nobles. It did give them personal freedom. Emancipation of the Hungarian peasantry promoted the growth of a new class of taxable landholders, but it did not abolish the deep-seated ills of feudalism and the exploitation of the landless squatters.

To equalize the incidence of taxation, Joseph ordered a fresh appraisal of the value of all properties in the empire; his goal was to impose a single and egalitarian tax on land. The goal was to modernize the relationship of dependence between the landowners and peasantry, relieve some of the tax burden on the peasantry, and increase state revenues. Joseph looked on the tax and land reforms as being interconnected and strove to implement them at the same time. The various commissions he established to formulate and carry out the reforms met resistance among the nobility, the peasantry, and some officials. Most of the reforms were abrogated shortly before or after Joseph's death in 1790; they were doomed to failure from the start because they tried to change too much in too short a time, and tried to radically alter the traditional customs and relationships that the villagers had long depended upon.

In the cities the new economic principles of the Enlightenment called for the destruction of the autonomous guilds, already weakened during the age of mercantilism. Joseph II's tax reforms and the institution of Katastralgemeinde (tax districts for the large estates) served this purpose, and new factory privileges ended guild rights while customs laws aimed at economic unity. The intellectual influence of the Physiocrats

led to the inclusion of agriculture in these reforms.

By the 18th century, centralization was the trend in medicine because more and better educated doctors requesting improved facilities; cities lacked the budgets to fund local hospitals; and the monarchy's wanted to end costly epidemics and quarantines. Joseph attempted to centralize medical care in Vienna through the construction of a single, large hospital, the famous Allgemeines Krankenhaus, which opened in 1784. Centralization worsened sanitation problems causing epidemics a 20% death rate in the new hospital. which undercut Joseph's plan, but the city became preeminent in the medical field in the next century.

Probably the most unpopular of all his reforms was his attempted modernization of the highly traditional Roman Catholic Church. Calling himself the guardian of Catholicism, Joseph II struck vigorously at papal power. He tried to make the Catholic Church in his empire the tool of the state, independent of Rome. Clergymen were deprived of the tithe and ordered to study in seminaries under government supervision, while bishops had to take a formal oath of loyalty to the crown. He financed the large increase in bishoprics, parishes, and secular clergy by extensive sales of monastic lands. As a man of the Enlightenment

he ridiculed the contemplative monastic orders, which he considered unproductive. Accordingly, he suppressed a third of the monasteries (over 700 were closed) and reduced the number of monks and nuns from 65,000 to 27,000. Church courts were abolished and marriage was defined as a civil contract outside the jurisdiction of the Church.

Josph sharply cut the number of holy days and reduced ornamentation in churches. He greatly simplified the manner of celebration. The results of these reforms included a deepening crisis of faith; the disappearance of piety; and the decline of morality. Opponents of the reforms blamed them for revealing Protestant tendencies, with the rise of Enlightenment rationalism and the emergence of a liberal class of bourgeois officials. Anti-clericalism emerged and persisted, while the traditional Catholics were energized in opposition to the emperor.

In foreign policy, there was no Enlightenment, only hunger for more territory and a willingness to undertake unpopular wars to get the land. Joseph was a belligerent, expansionist leader, who dreamed of making his Empire the greatest of the European powers. Joseph's plan was to acquire Bavaria, if necessary in exchange for Belgium (the Austrian Netherlands), but in 1778 and again in 1785 he was thwarted by King Frederick II

of Prussia, who had a much stronger army. This failure caused Joseph to seek territorial expansion in the Balkans, where he became involved in an expensive and futile war with the Turks 1787-1791, which was the price to be paid for friendship with Russia.

The Balkan policy of both Maria Theresa and Joseph II reflected the Cameralism promoted by Prince Kaunitz, stressing consolidation of the border lands by reorganization and expansion of the military frontier. Transylvania

was incorporated into the frontier in 1761 and the frontier regiments became the backbone of the military order, with the regimental commander exercising military and civilian power. "Populationistik" was the prevailing theory of colonization, which measured prosperity in terms of labor. Joseph II also stressed economic development. Habsburg influence was an essential factor in Balkan development in the last half of the 18th century, especially for the Serbs and Croats.

In Lombardy (in northern Italy) the cautious reforms of Maria Theresa in Lombardy enjoyed support from local reformers. Joseph II, however, by creating a powerful imperial officialdom directed from Vienna, undercut the dominant position of the Milanese principate and the traditions of jurisdiction and administration. In the place of provincial autonomy he established an unlimited centralism, which reduced Lombardy politically and economically to a fringe area of the Empire. As a reaction to these radical changes the middle class reformers shifted away from cooperation to strong resistance. From this basis appeared the beginnings of the later Lombard liberalism.

By 1790 rebellions had broken out in protest against Joseph's reforms in Belgium and Hungary, and his other dominions were restive under the burdens of his war with Turkey. His empire was threatened with dissolution, and he was forced to sacrifice some of his reform projects. His health shattered by disease, alone, and unpopular in all his lands, the bitter emperor died February 20, 1790. He was not yet forty-nine. Joseph II rode roughshod over age-old aristocratic privileges, liberties, and prejudices, thereby creating for himself many enemies, and they triumphed in the end. Joseph's attempt to reform the Hungarian lands illustrates the weakness of absolutism in the face of well-defended feudal liberties.

Behind his numerous reforms lay a comprehensive program influenced by the doctrines of enlightened absolutism, natural law, mercantilism, and physiocracy. With a goal of establishing a uniform legal framework to replace heterogeneous traditional structures, the reforms were guided at least implicitly by the principles of freedom and equality and were based on a conception of the state's central legislative authority. Joseph's accession marks a major break since the preceding reforms under Maria Theresa had not challenged these structures, but there was no similar break at the end of the Josephinian era. The reforms initiated by Joseph II had merit despite the way they were introduced. They were continued to varying degrees under his successors. They gained comprehensive "Austrian" form in the Allgemeine Bürgerliche Gesetzbuch of 1811 and have been seen as providing a foundation for subsequent reforms extending into the 20th century.

, previously the reforming Grand Duke of Tuscany. Leopold knew when to cut his losses, and soon cut deals with the revolting Netherlanders and Hungarians. He also managed to secure a peace with Turkey in 1791, and negotiated an alliance with Prussia, which had been allying with Poland to press for war on behalf of the Ottomans against Austria and Russia.

Leopold's reign also saw the acceleration of the French Revolution

. Although Leopold was sympathetic to the revolutionaries, he was also the brother of the French queen. Furthermore, disputes involving the status of the rights of various imperial princes in Alsace

, where the revolutionary French government was attempting to remove rights guaranteed by various peace treaties, involved Leopold as Emperor in conflicts with the French. The Declaration of Pillnitz

, made in late 1791 jointly with the Prussian King Frederick William II and the Elector of Saxony

, in which it was declared that the other princes of Europe took an interest in what was going on in France, was intended to be a statement in support of Louis XVI that would prevent the need from taking any kind of action. However, it instead inflamed the sentiments of the revolutionaries against the Emperor. Although Leopold did his best to avoid war with the French, he died in March of 1792. The French declared war on his inexperienced son Francis II

a month later.

The war with France, which lasted until 1797, proved unsuccessful for Austria. After some brief successes against the utterly disorganized French armies in early 1792, the tide turned, and the French overran the Austrian Netherlands in the last months of 1792. While the Austrians were so occupied, their erstwhile Prussian allies stabbed them in the back with the Second Partition of Poland

The war with France, which lasted until 1797, proved unsuccessful for Austria. After some brief successes against the utterly disorganized French armies in early 1792, the tide turned, and the French overran the Austrian Netherlands in the last months of 1792. While the Austrians were so occupied, their erstwhile Prussian allies stabbed them in the back with the Second Partition of Poland

, from which Austria was entirely excluded. This led to the dismissal of Francis's chief minister, Philipp von Cobenzl

, and his replacement with Franz Maria Thugut.

At around the same time, the increasing radicalization of the French Revolution, as well as the French occupation of the Low Countries, brought Britain, the Dutch Republic, and Spain into the war, which became known as the War of the First Coalition. Once again, there were initial successes against the disorganized armies of the French Republic, and the Netherlands were recovered. But in 1794 the tide turned once more, and Austrian forces were driven out of the Netherlands again—this time for good. Meanwhile, the Polish Crisis again became critical, resulting in a Third Partition (1795), in which Austria managed to secure important gains. The war in the west continued to go badly, as most of the coalition made peace, leaving Austria with only Britain and Piedmont-Sardinia

as allies. In 1796, the French Directory

planned a two-pronged campaign in Germany to force the Austrians to make peace, with a secondary thrust planned into Italy. Although Austrian forces under Archduke Charles, the Emperor's brother, were successful in driving the French back in Germany, the French Army of Italy, under the command of the young Corsican General Napoleon Bonaparte

, was brilliantly successful, forcing Piedmont out of the war, driving the Austrians out of Lombardy

and besieging Mantua

. Following the capture of Mantua in early 1797, Bonaparte advanced north through the Alps against Vienna, while new French armies moved again into Germany. Austria sued for peace. By the terms of the Treaty of Campo Formio

of 1797, Austria renounced its claims to the Netherlands and Lombardy, in exchange for which it partitioned the territories of the Republic of Venice

with the French. The Austrians also provisionally recognized the French annexation of the Left Bank of the Rhine, and agreed in principle that the German princes of the region should be compensated with ecclesiastical lands on the other side of the Rhine.

The peace did not last for long. Soon, differences emerged between the Austrians and French over the reorganization of Germany, and Austria joined Russia, Britain, and Naples in the War of the Second Coalition

in 1799. Although Austro-Russian forces were initially successful in driving the French from Italy, the tide soon turned—the Russians withdrew from the war after a defeat at Zürich

(1799) which they blamed on Austrian recklessness, and the Austrians were defeated by Bonaparte, now First Consul

at Marengo, which forced them to withdraw from Italy, and then in Germany at Hohenlinden. These defeats forced Thugut's resignation, and Austria, now led by Ludwig Cobenzl, to make peace at Lunéville

in early 1801. The terms were surprisingly mild—the terms of Campo Formio were largely reinstated, but now the way was clear for a reorganization of the Empire on French lines. By the Imperial Deputation Report of 1803, the Holy Roman Empire was entirely reorganized, with nearly all of the ecclesiastical territories and free cities, traditionally the parts of the Empire most friendly to the House of Austria, eliminated.

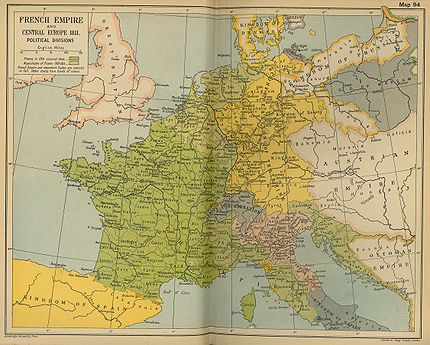

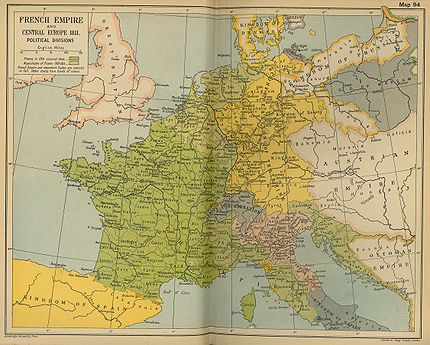

With Bonaparte's assumption of the title of Emperor of the French in 1804, Francis, seeing the writing on the wall for the old Empire, took the new title of Emperor of Austria

With Bonaparte's assumption of the title of Emperor of the French in 1804, Francis, seeing the writing on the wall for the old Empire, took the new title of Emperor of Austria

as Francis I, in addition to his title of Holy Roman Emperor. Soon, Napoleon's continuing machinations in Italy, including the annexation of Genoa

and Parma

, led once again to war in 1805—the War of the Third Coalition, in which Austria, Britain, Russia, and Sweden took on Napoleon. The Austrian forces began the war by invading Bavaria

, a key French ally in Germany, but were soon outmaneuvered and forced to surrender by Napoleon at Ulm

, before the main Austro-Russian force was defeated at Austerlitz

on December 2. By the Treaty of Pressburg, Austria was forced to give up large amounts of territory—Dalmatia

to France, Venetia to Napoleon's Kingdom of Italy, the Tyrol

to Bavaria, and Austria's various Swabian territories to Baden and Württemberg

, although Salzburg

, formerly held by Francis's younger brother, the previous Grand Duke of Tuscany, was annexed by Austria as compensation.

The defeat meant the end of the old Holy Roman Empire. Napoleon's satellite states in southern and Western Germany seceded from the Empire in the summer of 1806, forming the Confederation of the Rhine

, and a few days later Francis proclaimed the Empire dissolved, and renounced the old imperial crown.

Over the next three years Austria, now led by Philipp Stadion, attempted to maintain peace with France, but the overthrow of the Spanish Bourbons in 1808 was deeply disturbing to the Habsburgs, who rather desperately went to war once again in 1809, this time with no continental allies. Stadion's attempts to generate popular uprisings in Germany were unsuccessful, and the Russians honored their alliance with France, so Austria was once again defeated, although at greater cost than Napoleon, who suffered his first battlefield defeat in this war, at Aspern-Essling

, had expected. The terms of the Treaty of Schönbrunn

were quite harsh. Austria lost Salzburg to Bavaria, some of its Polish lands to Russia, and its remaining territory on the Adriatic (including much of Carinthia and Styria) to Napoleon's Illyrian Provinces

.

Klemens von Metternich, the new Austrian foreign minister, aimed to pursue a pro-French policy. The Emperor's daughter, Marie Louise, was married to Napoleon, and Austria contributed an army to Napoleon's invasion of Russia in 1812. With Napoleon's disastrous defeat in Russia at the end of the year, and Prussia's defection to the Russian side at the beginning of 1813, Metternich began slowly to shift his policy. Initially he aimed to mediate a peace between France and its continental enemies, but when it became apparent that Napoleon was not interested in compromise, Austria joined the allies and declared war on France in August 1813. The Austrian intervention was decisive. Napoleon was defeated at Leipzig

in October, and forced to withdraw into France itself. As 1814 began, the Allied forces invaded France. Initially, Metternich remained unsure as to whether he wanted Napoleon to remain on the throne, a Marie Louise regency for Napoleon's young son, or a Bourbon restoration, but he was eventually brought around by British Foreign Secretary Lord Castlereagh

to the last position. Napoleon abdicated on April 3, 1814, and Louis XVIII was restored, soon negotiating a peace treaty with the victorious allies at Paris

in June.

Under the control of Metternich, the Austrian Empire entered a period of censorship

Under the control of Metternich, the Austrian Empire entered a period of censorship

and a police state

in the period between 1815 and 1848 (Biedermaier or Vormärz period). However, both liberalism

and nationalism

were on the rise, which resulted in the Revolutions of 1848. Metternich and the mentally handicapped Emperor Ferdinand I

were forced to resign to be replaced by the emperor's young nephew Franz Joseph

. Separatist tendencies (especially in Lombardy

and Hungary) were suppressed by military force. A constitution was enacted in March 1848, but it had little practical impact. However, one of the concessions to revolutionaries with a lasting impact was the freeing of peasant

s in Austria. This facilitated industrialization, as many flocked to the newly industrializing cities of the Austrian domain (in the industrial centers of Bohemia

, Lower Austria

, Vienna

, and Upper Styria

). Social upheaval led to increased strife in ethnically mixed cities, leading to mass nationalist movements.

In 1859, the defeats at Solférino

and Magenta

against the combined forces of France and Sardinia

led to the loss of Lombardy and Tuscany

to the Kingdom of Sardinia, which was striving to create a unified national Italian state.

The defeat at Königgrätz

in the Austro-Prussian War

of 1866 resulted in Austria's exclusion from Germany; the German Confederation

was dissolved. The monarchy's weak external position forced Franz Joseph to concede internal reforms. To appease Hungarian nationalism, Franz Joseph made a deal with Hungarian nobles, which led to the creation of Austria-Hungary

through the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867. The western half of the realm (Cisleithania

) and Hungary (Transleithania) now became two realms with different interior policy, but with a common ruler and a common foreign and military policy.

The Austrian half of the dual monarchy began to move towards constitutionalism

The Austrian half of the dual monarchy began to move towards constitutionalism

. A constitutional system with a parliament, the Imperial Council, was created, and a bill of rights was enacted in 1867. Suffrage

to the new parliament's lower house was gradually expanded until 1907, when equal suffrage for all male citizens was introduced. However, the effectiveness of parliamentarism was hampered by conflicts between parties representing different ethnic groups, and meetings of the parliament ceased altogether during World War I

.

The decades until 1914 generally saw a lot of construction, expansion of cities and railway lines, and development of industry. During this period, now known as Gründerzeit

, Austria became an industrialized country, even though the Alpine regions remained characterized by agriculture.

In 1878, Austria-Hungary occupied Bosnia and Herzegovina

, which had been cut off from the rest of the Ottoman Empire

by the creation of new states in the Balkans. The territory was annexed in 1908 and put under joint rule by the governments of both Austria and Hungary.

Nationalist strife increased during the decades until 1914. The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand

Nationalist strife increased during the decades until 1914. The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand

, who was the presumed heir of Franz Joseph as Emperor, in Sarajevo

by a Serb nationalist group triggered World War I

. The defeat of the Central Powers

in 1918 resulted in the disintegration of Austria-Hungary. Emperor Karl of Austria, who had ruled since 1916, went into exile.

, in the Aftermath of World War I

the Empire was broken up based loosely on national grounds. Austria, with its modern borders, was created out of the main German speaking areas. On 12 November 1918, Austria became a republic

called German Austria

. The newly formed Austrian parliament asked for union with Germany. Article 2 of its provisional constitution stated: Deutschösterreich ist ein Bestandteil der Deutschen Republik (German Austria is part of the German Republic

). Plebiscites in the countries of Tyrol

and Salzburg

1919–21 yielded majorities of 98 and 99% in favour of a unification with Germany. It was feared that small Austria was not economically viable. In the end France and Italy prevented the merger, and demanded the construction of an independent Austria that had to remain autonomous for at least 20 years. The Treaty of Saint Germain included a provision that prohibited political or economic union with Germany and forced the country to change its name from the "Republic of German Austria" to the "Republic of Austria," i.e. the First Republic

. The German-speaking bordering areas of Bohemia

and Moravia

(later called the "Sudetenland

") were allocated to the newly founded Czechoslovakia

. Many Austrians and Germans regarded this as hypocrisy since U.S. president Woodrow Wilson

had proclaimed in his famous "Fourteen Points

" the "right of self-determination" for all nations. In the democratic German Weimar constitution

the aim of unification was codified in article 61: „Deutschösterreich erhält nach seinem Anschluß an das Deutsche Reich das Recht der Teilnahme am Reichsrat mit der seiner Bevölkerung entsprechenden Stimmenzahl. Bis dahin haben die Vertreter Deutschösterreichs beratende Stimme.“ (German Austria has the right to participate in the German Reichsrat

(the constitutional representation of the federal German states) with a consulting role according to its number of inhabitants until unification with Germany.").

Although Austria-Hungary had been one of the Central Powers, the allied victors were much more lenient with a defeated Austria than either Germany or Hungary. Representatives of the new Republic of Austria convinced them that it was unfair to penalize Austria for the actions of a now dissolved Empire, especially as other areas of the Empire were now perceived to be on the "victorious" side, simply because they had renounced the Empire at the end of the war. Austria never did have to pay reparations because allied commissions determined that the country could not afford to pay. It was also the only defeated country to acquire additional territory as part of border adjustments: the Burgenland

Although Austria-Hungary had been one of the Central Powers, the allied victors were much more lenient with a defeated Austria than either Germany or Hungary. Representatives of the new Republic of Austria convinced them that it was unfair to penalize Austria for the actions of a now dissolved Empire, especially as other areas of the Empire were now perceived to be on the "victorious" side, simply because they had renounced the Empire at the end of the war. Austria never did have to pay reparations because allied commissions determined that the country could not afford to pay. It was also the only defeated country to acquire additional territory as part of border adjustments: the Burgenland

, a small land tract to the east that despite its German-speaking majority had belonged to Hungary. The area had been discussed as the site of a Czech Corridor

to Yugoslavia.

On 20 October 1920, a plebiscite in the Austrian state of Carinthia

was held in which the population chose to remain a part of Austria, rejecting the territorial claims of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes to the state. The German-speaking parts of western Hungary, now christened Burgenland

, joined Austria as a new state

in 1921, with the exception of the city of Sopron

, whose population decided in a referendum (which is sometimes considered by Austrians to have been rigged) to remain with Hungary. However, the Treaty of Saint Germain also meant that Austria lost significant German-speaking territories, in particular the southern part of the County of Tyrol

(now South Tyrol

) to Italy and the German-speaking areas within Bohemia

and Moravia

to Czechoslovakia

.

Between 1918 and 1920, there was a coalition government including both left and right-wing parties, which enacted progressive socio-economic and labour legislation. In 1920, the modern Constitution of Austria

was enacted. The interwar years were socio-economically difficult for Austria, partly because the newly created borders tore apart what had been a common economic area.

Austrian politics were characterized by intense and sometimes violent conflict between left and right from 1920 onwards. The Social Democratic Party of Austria

Austrian politics were characterized by intense and sometimes violent conflict between left and right from 1920 onwards. The Social Democratic Party of Austria

, which pursued a fairly left-wing course known as Austromarxism

at that time, could count on a secure majority in "Red Vienna

", while right-wing parties controlled all other states. Since 1920, Austria was ruled by the Christian Socialist Party, which had close ties to the Roman Catholic Church

. It was headed by a Catholic priest named Ignaz Seipel

(1876–1932), who served twice as Chancellor

(1922–1924 and 1926–1929). While in power, Seipel was working for an alliance between wealthy industrialists and the Roman Catholic Church

.

Both left-wing and right-wing paramilitary

forces were created during the 20s, namely the Heimwehr

in 1921–1923 and the Republican Schutzbund in 1923. A clash between those groups in Schattendorf

, Burgenland

, on 30 January 1927 led to the death of a man and a child. Right-wing veteran

s were indicted at a court in Vienna, but acquitted in a jury trial

. This led to massive protests and fire at the Justizpalast in Vienna. In the July Revolt of 1927

, 89 protesters were killed by the Austrian police forces.

Political conflict escalated until the early 1930s. Engelbert Dollfuß of the Christian Social Party became Chancellor in 1932.

In March 1933 the Dollfuss cabinet took advantage of a formal error during a vote on a bill in parliament. As the vote was very narrow, all of the three presidents of the National Council

stepped down because they were not allowed to vote themselves while in office. This was an unforeseen event but it could have been resolved according to the rules of procedure. However, the cabinet declared that the parliament had ceased to function and forcibly prevented the National Council from reassembling. The executive then took over legislative power by using an emergency provision which had been enacted during World War I

. Even after this putsch, the socialist party

hesitated and tried to resolve the crisis in a peaceful way.

On 12 February 1934 the new Austrofascist regime provoked the Austrian Civil War

by ordering search warrants for the headquarters of the socialist party. At that time the socialist party structures were already weakened and the uprising of its supporters was quickly defeated. Subsequently the socialist party and all its ancillary organisations were banned.

On 1 May 1934, the Dollfuss cabinet approved a new constitution

that abolished freedom of the press, established one party system (known as "The Patriotic Front") and created a total state monopoly on employer-employee relations. This system remained in force until Austria became part of the Third Reich in 1938. The Patriotic Front government frustrated the ambitions of pro-Hitlerite sympathizers in Austria who wished both political influence and unification with Germany, leading to the assassination of Dollfuss on 25 July 1934. His successor Schuschnigg

maintained the ban on pro-Hitlerite activities in Austria, but was forced to resign on 11 March 1938 following a demand by Hitler for power-sharing with pro-German circles. Following Schuschnigg's resignation, German troops occupied Austria with no resistance.

and the Treaty of St. Germain had explicitly forbidden the unification of Austria and Germany, and native Austrian-born Hitler

was vastly striving to annex Austria during the late 1930s, which was fiercely resisted by the Austrian Schuschnigg

dictatorship. When the conflict was escalating in early 1938, Chancellor Schuschnigg announced a plebiscite on the issue on March 9, which was to take place on 13 March. On 12 March, German troops entered Austria

, who met celebrating crowds, in order to install Nazi puppet Arthur Seyss-Inquart as Chancellor. With a Nazi administration already in place and the country integrated into the Third Reich as so-called Ostmark

, a referendum on 10 April approved of the annexation with a majority of 99.73%.

As a result, Austria ceased to exist as an independent country. This annexation was enforced by military invasion but large parts of the Austrian population were in favour of the Nazi regime, many Austrians participated in its crimes. There was a Jewish population of about 200,000 then living in Vienna, which had contributed considerably to science and culture and very many of these people, with socialist and Catholic Austrian

politicians were deported to concentration camps, murdered or forced into exile.

Just before the end of the war, on 28 March 1945, American troops set foot on Austrian soil and the Soviet Union's Red Army crossed the eastern border two days later, taking Vienna on 13 April. American and British forces occupied the western and southern regions, preventing Soviet forces from completely overrunning and controlling the country.

In April 1945 Karl Renner

In April 1945 Karl Renner

, an Austrian elder statesman, declared Austria separate from Germany and set up a government which included socialists

, conservatives and communists. A significant number of these were returning from exile or Nazi detention, having thus played no role in the Nazi government. This contributed to the Allies treating Austria more as a liberated, rather than defeated, country, and the government was recognized by the Allies later that year. The country was occupied by the Allies from 9 May 1945 and under the Allied Commission for Austria established by an agreement on 4 July 1945, it was divided into Zones occupied respectively by American, British, French and Soviet Army personnel, with Vienna

being also divided similarly into four sectors—with an International Zone at its heart.

Though under occupation, this Austrian government was officially permitted to conduct foreign relations with the approval of the Four Occupying Powers under the agreement of 28 June 1946. As part of this trend, Austria was one of the founding members of the Danube Commission formed on 18 August 1948. Austria would benefit from the Marshall Plan

but economic recovery was very slow—as a result of the State's 10 year political overseeing by the Allied Powers.

Unlike the First Republic, which had been characterized by sometimes violent conflict between the different political groups, the Second Republic became a stable democracy. The two largest leading parties, the Christian-conservative Austrian People's Party

(ÖVP) and the Social Democratic Party

(SPÖ) remained in a coalition led by the ÖVP until 1966. The Communist Party of Austria

(KPÖ), who had hardly any support in the Austrian electorate, remained in the coalition until 1950 and in parliament until 1959. For much of the Second Republic, the only opposition party was the Freedom Party of Austria

(FPÖ), which included German national

and liberal

political currents. It was founded in 1955 as a successor organisation to the short-lived Federation of Independents

(VdU).

was signed on 15 May 1955. Upon the termination of allied occupation, Austria was proclaimed

a neutral country

, and "everlasting" neutrality was incorporated into the Constitution

on 26 October 1955.

The political system of the Second Republic came to be characterized by the system of Proporz

, meaning that posts of some political importance were split evenly between members of the SPÖ and ÖVP. Interest group representations with mandatory membership (e.g. for workers, businesspeople, farmers etc.) grew to considerable importance and were usually consulted in the legislative process, so that hardly any legislation was passed that did not reflect widespread consensus. The Proporz and consensus systems largely held even during the years between 1966 and 1983, when there were non-coalition governments.

The ÖVP-SPÖ coalition ended in 1966, when the ÖVP gained a majority in parliament. However, it lost it in 1970, when SPÖ leader Bruno Kreisky

formed a minority government

tolerated by the FPÖ. In the elections of 1971, 1975 and 1979 he obtained an absolute majority. The 70s were then seen as a time of liberal reforms in social policy

. Today, the economic policies of the Kreisky era are often criticized, as the accumulation of a large national debt began, and non-profitable nationalized industries were strongly subsidized.

Following severe losses in the 1983 elections, the SPÖ entered into a coalition with the FPÖ under the leadership of Fred Sinowatz

. In Spring 1986, Kurt Waldheim

was elected

president

amid considerable national and international protest because of his possible involvement with the Nazis

and war crimes during World War II

. Fred Sinowatz

resigned, and Franz Vranitzky

became chancellor.

In September 1986, in a confrontation between the German-national and liberal wings, Jörg Haider

became leader of the FPÖ

. Chancellor Vranitzky rescinded the coalition pact between FPÖ and SPÖ, and after new elections, entered into a coalition with the ÖVP, which was then led by Alois Mock

. Jörg Haider's populism and criticism of the Proporz

system allowed him to gradually expand his party's support in elections, rising from 4% in 1983 to 27% in 1999. The Green Party

managed to establish itself in parliament from 1986 onwards.

in 1995 (Video of the signing in 1994), and Austria was set on the track towards joining the Euro

zone, when it was established in 1999.

In 1993, the Liberal Forum

was founded by dissidents from the FPÖ

. It managed to remain in parliament until 1999.

Viktor Klima

succeeded Vranitzky as chancellor in 1997.

In 1999, the ÖVP fell back to third place behind the FPÖ in the elections. Even though ÖVP

chairman and Vice Chancellor

Wolfgang Schüssel

had announced that his party would go into opposition in that case, he entered into a coalition with the FPÖ – with himself as chancellor – in early 2000 under considerable national and international protest. Jörg Haider

resigned as FPÖ chairman, but retained his post as governor

of Carinthia

but kept substantial influence within the FPÖ.

In 2002, disputes within the FPÖ

resulting from losses in state elections caused the resignation of several FPÖ government members

and a collapse of the government. Wolfgang Schüssel's ÖVP emerged as the winner of the subsequent election, ending up in first place for the first time since 1966. The FPÖ lost more than half of its voters, but reentered the coalition with the ÖVP. Despite the new coalition, the voter support for the FPÖ continued to dwindle in all most all local and state elections. Disputes between "nationalist" and "liberals" wings of the party resulted in a split, with the founding of a new liberal party called the Alliance for the Future of Austria

(BZÖ) and led by Jörg Haider. Since all FPÖ government members and most FPÖ members of parliament decided to join the new party, the Schüssel coalition remained in office (now in the constellation ÖVP–BZÖ, with the remaining FPÖ in opposition) until the next elections. On 1 October 2006 the SPÖ won a head on head elections

and negotiated a grand coalition with the ÖVP. This coalition started its term on 11 January 2007 with Alfred Gusenbauer

as Chancellor of Austria. For the first time, the Green Party of Austria became the third largest party in a nation-wide election, overtaking the FPÖ by a narrow margin of only a few hundred votes.

The grand coalition headed by Alfred Gusenbauer collapsed in the early summer of 2008 over disagreements about the country's EU policy. The early elections

held on September 28 resulted in extensive losses for the two ruling parties and corresponding gains for Heinz-Christian Strache

's FPÖ and Jörg Haider

's BZÖ (the Green Party was relegated to the 5th position). Nevertheless, SPÖ and ÖVP renewed their coalition under the leadership of the new SPÖ party chairman Werner Faymann

. In 2008 Jörg Haider

died in a car accident and was succeeded as BZÖ party chairman by Herbert Scheibner and as governor of Carinthia

by Gerhard Dörfler

.

Country

A country is a region legally identified as a distinct entity in political geography. A country may be an independent sovereign state or one that is occupied by another state, as a non-sovereign or formerly sovereign political division, or a geographic region associated with a previously...

of Austria

Austria

Austria , officially the Republic of Austria , is a landlocked country of roughly 8.4 million people in Central Europe. It is bordered by the Czech Republic and Germany to the north, Slovakia and Hungary to the east, Slovenia and Italy to the south, and Switzerland and Liechtenstein to the...

and predecessor states, from the Iron Age, through to a sovereign state, annexation by the German Third Reich, partition after the Second World War and later developments until the present day. More information can be found in history of Europe

History of Europe

History of Europe describes the history of humans inhabiting the European continent since it was first populated in prehistoric times to present, with the first human settlement between 45,000 and 25,000 BC.-Overview:...

.

Prehistory

During the Neolithic, the territory of modern-day Austria was home to the Linear pottery cultureLinear Pottery culture

The Linear Pottery culture is a major archaeological horizon of the European Neolithic, flourishing ca. 5500–4500 BC.It is abbreviated as LBK , is also known as the Linear Band Ware, Linear Ware, Linear Ceramics or Incised Ware culture, and falls within the Danubian I culture of V...

, one of the first agrarian cultures in Europe.

Ötzi the Iceman

Ötzi the Iceman

Ötzi the Iceman , Similaun Man, and Man from Hauslabjoch are modern names for a well-preserved natural mummy of a man who lived about 5,300 years ago. The mummy was found in September 1991 in the Ötztal Alps, near Hauslabjoch on the border between Austria and Italy. The nickname comes from the...

, a well-preserved mummy of a man frozen in Austrian Alps, is dated around 3300 BC.

Celtic and Roman

Noricum

Noricum, in ancient geography, was a Celtic kingdom stretching over the area of today's Austria and a part of Slovenia. It became a province of the Roman Empire...

, in ancient

Ancient history

Ancient history is the study of the written past from the beginning of recorded human history to the Early Middle Ages. The span of recorded history is roughly 5,000 years, with Cuneiform script, the oldest discovered form of coherent writing, from the protoliterate period around the 30th century BC...

geography

Geography

Geography is the science that studies the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth. A literal translation would be "to describe or write about the Earth". The first person to use the word "geography" was Eratosthenes...

, was a Celtic kingdom (perhaps better described as a federation of, by tradition, twelve tribes) stretching over the area of today's Austria

Austria

Austria , officially the Republic of Austria , is a landlocked country of roughly 8.4 million people in Central Europe. It is bordered by the Czech Republic and Germany to the north, Slovakia and Hungary to the east, Slovenia and Italy to the south, and Switzerland and Liechtenstein to the...

and a part of Slovenia

Slovenia

Slovenia , officially the Republic of Slovenia , is a country in Central and Southeastern Europe touching the Alps and bordering the Mediterranean. Slovenia borders Italy to the west, Croatia to the south and east, Hungary to the northeast, and Austria to the north, and also has a small portion of...

. It became a province

Roman province

In Ancient Rome, a province was the basic, and, until the Tetrarchy , largest territorial and administrative unit of the empire's territorial possessions outside of Italy...

of the Roman Empire

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

. It was bounded on the north by the Danube

Danube

The Danube is a river in the Central Europe and the Europe's second longest river after the Volga. It is classified as an international waterway....

, on the west by Raetia

Raetia

Raetia was a province of the Roman Empire, named after the Rhaetian people. It was bounded on the west by the country of the Helvetii, on the east by Noricum, on the north by Vindelicia, on the west by Cisalpine Gaul and on south by Venetia et Histria...

and Vindelicia

Vindelicia

In the pre-Roman geography of Europe, Vindelicia identifies the country inhabited by the Vindelici, a region bounded on the north by the Danube and the Hadrian's Limes Germanicus, on the east by the Oenus , on the south by Raetia and on the west by the territory of the Helvetii...

, on the east and southeast by Pannonia

Pannonia

Pannonia was an ancient province of the Roman Empire bounded north and east by the Danube, coterminous westward with Noricum and upper Italy, and southward with Dalmatia and upper Moesia....

, on the south by Region 10, Venetia et Histria.

Early Middle Ages

During the Migration PeriodMigration Period

The Migration Period, also called the Barbarian Invasions , was a period of intensified human migration in Europe that occurred from c. 400 to 800 CE. This period marked the transition from Late Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages...

, the Slavic

Slavic peoples

The Slavic people are an Indo-European panethnicity living in Eastern Europe, Southeast Europe, North Asia and Central Asia. The term Slavic represents a broad ethno-linguistic group of people, who speak languages belonging to the Slavic language family and share, to varying degrees, certain...

tribe of the Carantanians migrated into the Alps

Slavic settlement of the Eastern Alps

Slavic settlement of the Eastern Alps region was a historic process that took place between the 6th and 9th century AD, having culminated in the final quarter of the 6th century...

in the wake of the expansion of their Avar

Eurasian Avars

The Eurasian Avars or Ancient Avars were a highly organized nomadic confederacy of mixed origins. They were ruled by a khagan, who was surrounded by a tight-knit entourage of nomad warriors, an organization characteristic of Turko-Mongol groups...

overlords during the 7th century, mixed with the Celto-Romanic population, and established the realm of Carantania, which covered much of eastern and central Austrian territory. In the meantime, the Germanic tribe of the Bavarians had developed in the 5th and 6th century in the west of the country and in Bavaria

Bavaria

Bavaria, formally the Free State of Bavaria is a state of Germany, located in the southeast of Germany. With an area of , it is the largest state by area, forming almost 20% of the total land area of Germany...

, while what is today Vorarlberg

Vorarlberg

Vorarlberg is the westernmost federal-state of Austria. Although it is the second smallest in terms of area and population , it borders three countries: Germany , Switzerland and Liechtenstein...

had been settled by the Alemans. Those groups mixed with the Rhaeto-Romanic

Romansh people

The Romansh people are a people and ethnic group of Switzerland, native speakers of the Romansh language. However, nowadays they almost always are multilingual, speaking also German and sometimes Italian, which are the other official language of Graubünden, the canton where they are...

population and pushed it up into the mountains.

Carantania, under pressure of the Avars, lost its independence to Bavaria

Bavaria

Bavaria, formally the Free State of Bavaria is a state of Germany, located in the southeast of Germany. With an area of , it is the largest state by area, forming almost 20% of the total land area of Germany...

in 745 and became a margraviate. During the following centuries, Bavarian settlers went down the Danube and up the Alps, a process through which Austria was to become the mostly German-speaking country it is today.

The Bavarians themselves came under the overlordship of the Carolingian

Carolingian

The Carolingian dynasty was a Frankish noble family with origins in the Arnulfing and Pippinid clans of the 7th century AD. The name "Carolingian", Medieval Latin karolingi, an altered form of an unattested Old High German *karling, kerling The Carolingian dynasty (known variously as the...

Franks

Franks

The Franks were a confederation of Germanic tribes first attested in the third century AD as living north and east of the Lower Rhine River. From the third to fifth centuries some Franks raided Roman territory while other Franks joined the Roman troops in Gaul. Only the Salian Franks formed a...

and subsequently became a duchy

Duchy

A duchy is a territory, fief, or domain ruled by a duke or duchess.Some duchies were sovereign in areas that would become unified realms only during the Modern era . In contrast, others were subordinate districts of those kingdoms that unified either partially or completely during the Medieval era...

of the Holy Roman Empire

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a realm that existed from 962 to 1806 in Central Europe.It was ruled by the Holy Roman Emperor. Its character changed during the Middle Ages and the Early Modern period, when the power of the emperor gradually weakened in favour of the princes...

. Duke Tassilo III

Tassilo III of Bavaria

Tassilo III was duke of Bavaria from 748 to 788, the last of the house of the Agilolfings.Tassilo, then still an infant, began his rule as a Frankish ward under the tutelage of the Merovingian Mayor of the Palace Pepin the Short after Tassilo's father, Duke Odilo of Bavaria, had died in 747 and...

, who wanted to maintain Bavarian independence, was defeated and displaced by Charlemagne

Charlemagne

Charlemagne was King of the Franks from 768 and Emperor of the Romans from 800 to his death in 814. He expanded the Frankish kingdom into an empire that incorporated much of Western and Central Europe. During his reign, he conquered Italy and was crowned by Pope Leo III on 25 December 800...

in 789. An eastern march (military borderland), the Avar March

Avar March

The Avar March was a frontier district established by Charlemagne against Avaria in the southeast of the Carolingian Empire.In the late 8th century, Charlemagne destroyed the Avar fortress called the Ring of the Avars and made the people tributary to him...

, was established in Charlemagne's time, but it was overrun by the Hungarians in 909.

Babenberg Austria

Battle of Lechfeld

The Battle of Lechfeld , often seen as the defining event for holding off the incursions of the Hungarians into Western Europe, was a decisive victory by Otto I the Great, King of the Germans, over the Hungarian leaders, the harka Bulcsú and the chieftains Lél and Súr...

(955), new marches were established in what is today Austria. The one known as the marchia orientalis was to become the core territory of Austria and was given to Leopold of Babenberg in 976 after the revolt of Henry II, Duke of Bavaria

Henry II, Duke of Bavaria

Henry II , called the Wrangler or the Quarrelsome, in German Heinrich der Zänker, was the son of Henry I and Judith of Bavaria.- Biography :...

.

The marches

Marches

A march or mark refers to a border region similar to a frontier, such as the Welsh Marches, the borderland between England and Wales. During the Frankish Carolingian Dynasty, the word spread throughout Europe....

were overseen by a comes or dux as appointed by the emperor. These titles are usually translated as count or duke, but these terms conveyed very different meanings in the Early Middle Ages

Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages was the period of European history lasting from the 5th century to approximately 1000. The Early Middle Ages followed the decline of the Western Roman Empire and preceded the High Middle Ages...

, so the Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

versions are to be preferred. In lumbardi-speaking countries, the title was eventually regularized to margrave

Margrave

A margrave or margravine was a medieval hereditary nobleman with military responsibilities in a border province of a kingdom. Border provinces usually had more exposure to military incursions from the outside, compared to interior provinces, and thus a margrave usually had larger and more active...

(German: markgraf) i.e. "count of the mark".

The first recorded instance of the name Austria appeared in 996, written as Ostarrîchi

Ostarrîchi

The German name of Austria, , derives from the Old High German word . A variant is recorded in the Ostarrîchi Document of 996. This word is thought to be a translation of Latin Marchia Orientalis into a local dialect. This was a march, or borderland, of the Duchy of Bavaria created in 976. Reich...

, referring to the territory of the Babenberg March. The term Ostmark

Ostmark

Ostmark is a German term meaning either Eastern march when applied to territories or Eastern Mark when applied to currencies.Ostmark may refer to:...

is not historically certain and appears to be a translation of marchia orientalis that came up only much later.

The following centuries were characterized first by the settlement of the country, when forests were cleared and towns and monasteries were founded. In 1156 the Privilegium Minus

Privilegium Minus

The Privilegium Minus is a document issued by Emperor Frederick I on September 17, 1156. It included the elevation of the Margraviate of Austria to a Duchy, which was given as an inheritable fief to the House of Babenberg. Its recipient was Frederick's paternal uncle Margrave Henry II Jasomirgott...

elevated Austria to the status of a duchy. In 1192, the Babenbergs also acquired the Duchy of Styria through the Georgenberg Pact

Georgenberg Pact

The Georgenberg Pact was signed on 17 August 1186 on the Georgenberg mountain above Enns and consisted of two parts. The first part was an agreement between Duke Ottokar IV of Styria and Duke Leopold V of Austria...

. At that time, the Babenberg Dukes came to be one of the most influential ruling families in the region, peaking in the reign of Leopold VI (1198–1230).

However, with the slaughter of his son Frederick II in 1246, the line went extinct, which resulted in the interregnum

Interregnum

An interregnum is a period of discontinuity or "gap" in a government, organization, or social order...

, a period of several decades during which the status of the country was disputed. Otakar II Přemysl of Bohemia

Ottokar II of Bohemia

Ottokar II , called The Iron and Golden King, was the King of Bohemia from 1253 until 1278. He was the Duke of Austria , Styria , Carinthia and Carniola also....

effectively controlled the duchies of Austria, Styria and Carinthia. His reign came to an end with his defeat in the battle of Dürnkrut and Jedenspeigen

Battle of Dürnkrut and Jedenspeigen

The Battle on the Marchfeld at Dürnkrut and Jedenspeigen took place on August 26, 1278 and was a decisive event for the history of Central Europe for the following centuries...

at the hand of Rudolf of Habsburg in 1278.

Following the extinction of the Babenbergs in the 13th century, Austria came briefly under the rule of the Czech

Czech Republic

The Czech Republic is a landlocked country in Central Europe. The country is bordered by Poland to the northeast, Slovakia to the east, Austria to the south, and Germany to the west and northwest....

King Ottokar II of Bohemia

Ottokar II of Bohemia

Ottokar II , called The Iron and Golden King, was the King of Bohemia from 1253 until 1278. He was the Duke of Austria , Styria , Carinthia and Carniola also....

. Contesting the election of Rudolf I of Habsburg as emperor, Ottokar was defeated and killed by Rudolf, who took Austria with the assistance of King Ladislaus IV of Hungary.

Beginnings (1278–1526)

Carniola

Carniola was a historical region that comprised parts of what is now Slovenia. As part of Austria-Hungary, the region was a crown land officially known as the Duchy of Carniola until 1918. In 1849, the region was subdivided into Upper Carniola, Lower Carniola, and Inner Carniola...

came under Habsburg rule in 1335, Tyrol

German Tyrol

German Tyrol is a historical region in the Alps now divided between Austria and Italy. It includes largely ethnic German areas of historical County of Tyrol: the Austrian state of Tyrol and the province of South Tyrol but not the largely Italian-speaking province of Trentino .-History:German...

in 1363. These provinces, together, became known as the Habsburg Hereditary Lands, although they were sometimes all lumped together simply as Austria.

Following the notable but short reign of Rudolf IV (the first to claim the title of Archduke of Austria), his brothers Albert III and Leopold III split the realms in the Treaty of Neuberg

Treaty of Neuberg

In the Treaty of Neuberg, concluded between the Habsburg Dukes Albert III and Leopold III on September 9, 1379 in Neuberg an der Mürz, the Habsburg lands were divided between the two brothers...

in 1379. Albert retained Austria proper, while Leopold took the remaining territories. In 1402, there was another split in the Leopoldian line

Leopoldian line

The Leopoldian line was a line of the Habsburg dynasty. It was begun by Leopold III, duke of Styria, Carinthia and Carniola .The division of the Habsburg territories between the Albertinian line and the Leopoldian line was a result of the early death of Rudolf IV...

, when Ernest the Iron took Inner Austria

Inner Austria

Inner Austria was a term used from the late 14th to the early 17th century for the Habsburg hereditary lands south of the Semmering Pass, referring to the duchies of Styria, Carinthia, Carniola and the Windic March, the County of Gorizia , the city of Trieste and assorted smaller possessions...

(Styria, Carinthia and Carniola) and Frederick IV became ruler of Tyrol and Further Austria

Further Austria

Further Austria or Anterior Austria was the collective name for the old possessions of the House of Habsburg in the former Swabian stem duchy of south-western Germany, including territories in the Alsace region west of the Rhine and in Vorarlberg, after the focus of the Habsburgs had moved to the...

. The territories were only reunified by Ernest's son Frederick V

Frederick III, Holy Roman Emperor

Frederick the Peaceful KG was Duke of Austria as Frederick V from 1424, the successor of Albert II as German King as Frederick IV from 1440, and Holy Roman Emperor as Frederick III from 1452...

(Frederick III as Holy Roman Emperor), when the Albertinian line

Albertinian Line

The Albertinian line was a line of the Habsburg dynasty, begun by Albert III, who, after death of his brother Rudolf IV the Founder, split the Habsburg territories with his brother. Albert was the prince of the Duchy of Austria, while the southern territories were ruled by his brother - Leopold III...

(1457) and the Elder Tyrolean line (1490) had become extinct.

In 1438, Duke Albert V of Austria was chosen as the successor to his father-in-law, Emperor Sigismund. Although Albert himself only reigned for a year, from then on, every emperor was a Habsburg, with only one exception. The Habsburgs began also to accumulate lands far from the Hereditary Lands. In 1477, the Archduke Maximilian

Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor

Maximilian I , the son of Frederick III, Holy Roman Emperor and Eleanor of Portugal, was King of the Romans from 1486 and Holy Roman Emperor from 1493 until his death, though he was never in fact crowned by the Pope, the journey to Rome always being too risky...

, only son of Emperor Frederick III

Frederick III, Holy Roman Emperor

Frederick the Peaceful KG was Duke of Austria as Frederick V from 1424, the successor of Albert II as German King as Frederick IV from 1440, and Holy Roman Emperor as Frederick III from 1452...

, married the heiress of Burgundy

Duchy of Burgundy