Grub Street

Encyclopedia

London

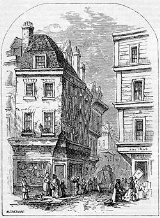

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

's impoverished Moorfields

Moorfields

In London, the Moorfields were one of the last pieces of open land in the City of London, near the Moorgate. The fields were divided into three areas, the Moorfields proper, just north of Bethlem Hospital, and inside the City boundaries, and Middle and Upper Moorfields to the north.After the Great...

district that ran from Fore Street east of St Giles-without-Cripplegate

St Giles-without-Cripplegate

St Giles-without-Cripplegate is a Church of England church in the City of London, located within the modern Barbican complex. When built it stood without the city wall, near the Cripplegate. The church is dedicated to St Giles, patron saint of beggars and cripples...

north to Chiswell Street. Famous for its concentration of impoverished 'hack writer

Hack writer

Hack writer is a colloquial and usually pejorative term used to refer to a writer who is paid to write low-quality, rushed articles or books "to order", often with a short deadline. In a fiction-writing context, the term is used to describe writers who are paid to churn out sensational,...

s', aspiring poets, and low-end publishers and booksellers, Grub Street existed on the margins of London's journalistic and literary scene. It was pierced along its length with narrow entrances to alleys and courts, many of which retained the names of early signboards. Its bohemian

Bohemianism

Bohemianism is the practice of an unconventional lifestyle, often in the company of like-minded people, with few permanent ties, involving musical, artistic or literary pursuits...

society was set amidst the impoverished neighbourhood's low-rent flophouses, brothels, and coffeehouses.

According to Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson , often referred to as Dr. Johnson, was an English author who made lasting contributions to English literature as a poet, essayist, moralist, literary critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer...

's Dictionary

A Dictionary of the English Language

Published on 15 April 1755 and written by Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language, sometimes published as Johnson's Dictionary, is among the most influential dictionaries in the history of the English language....

, the term was "originally the name of a street... much inhabited by writers of small histories, dictionaries, and temporary poems, whence any mean production is called grubstreet." Johnson himself had lived and worked on Grub Street early in his career. The contemporary image of Grub Street was popularised by Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope was an 18th-century English poet, best known for his satirical verse and for his translation of Homer. He is the third-most frequently quoted writer in The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, after Shakespeare and Tennyson...

in his Dunciad.

The street name no longer exists, but Grub Street has since become a pejorative term for impoverished hack writers and writings of low literary value.

Toponymy

According to the Oxford English DictionaryOxford English Dictionary

The Oxford English Dictionary , published by the Oxford University Press, is the self-styled premier dictionary of the English language. Two fully bound print editions of the OED have been published under its current name, in 1928 and 1989. The first edition was published in twelve volumes , and...

the verb

Verb

A verb, from the Latin verbum meaning word, is a word that in syntax conveys an action , or a state of being . In the usual description of English, the basic form, with or without the particle to, is the infinitive...

grub translates as "To dig superficially; to break up the surface of (the ground); to clear (ground) of roots and stumps." The earliest use of the word is in 1300, "Theif hus brecand, or gruband grund", and in 1572 "Ze suld your ground grube with simplicitie". Grub Street appears to have taken its name from a refuse ditch that ran alongside (grub), and variations on the name include Grobstrat (1217–1243), Grobbestrate (1277–1278), Grubbestrate (1281), Grubbestrete (1298), Grubbelane (1336), Grubstrete, and Crobbestrate. Grub is also a derogatory noun

Noun

In linguistics, a noun is a member of a large, open lexical category whose members can occur as the main word in the subject of a clause, the object of a verb, or the object of a preposition .Lexical categories are defined in terms of how their members combine with other kinds of...

applied to 'a person of mean abilities, a literary hack; in recent use, a person of slovenly attire and unpleasant manners.'

Early history

Cripplegate

Cripplegate was a city gate in the London Wall and a name for the region of the City of London outside the gate. The area was almost entirely destroyed by bombing in World War II and today is the site of the Barbican Estate and Barbican Centre...

ward, in the parish of St Giles-without-Cripplegate

St Giles-without-Cripplegate

St Giles-without-Cripplegate is a Church of England church in the City of London, located within the modern Barbican complex. When built it stood without the city wall, near the Cripplegate. The church is dedicated to St Giles, patron saint of beggars and cripples...

(Cripplegate ward was bisected by the city walls, and therefore was both 'within' and 'without'). Much of the area was originally extensive marshlands from the Fleet Ditch

River Fleet

The River Fleet is the largest of London's subterranean rivers. Its two headwaters are two streams on Hampstead Heath; each is now dammed into a series of ponds made in the 18th century, the Hampstead Ponds and the Highgate Ponds. At the south edge of Hampstead Heath these two streams flow...

, to Bishopsgate, contiguous with Moorfields to the east. The St Alphage

St Alphage London Wall

St Alphage London Wall, so called because it sat right on London Wall, the City of London boundary, was a church in Bassishaw Ward in the City of London...

Churchwardens' Accounts of 1267 mention a stream running from the nearby marsh, through Grub Street, and under the city walls into the Walbrook river

Walbrook

Walbrook is the name of a ward, a street and a subterranean river in the City of London.-Underground river:The river played a key role in the Roman settlement of Londinium, the city now known as London. It is thought that the river was named because it ran through or under the London Wall; another...

, which may have provided the local population with drinking water, however the marshes were drained in 1527.

One of Grub Street's early residents was the notable recluse Henry Welby, the owner of the estate of Goxhill

Goxhill

Goxhill is a large village and civil parish in North Lincolnshire, England. It lies east of Barton-upon-Humber and north west of Immingham. It is served by Goxhill railway station, this line runs from the town of Barton to the seaside resort of Cleethorpes...

in Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire is a county in the east of England. It borders Norfolk to the south east, Cambridgeshire to the south, Rutland to the south west, Leicestershire and Nottinghamshire to the west, South Yorkshire to the north west, and the East Riding of Yorkshire to the north. It also borders...

. In 1592 his half-brother attempted to shoot him with a pistol. Shocked, he took a house on Grub Street and remained there, in near-total seclusion, for the rest of his life. He died in 1636 and was buried at St Giles

St Giles-without-Cripplegate

St Giles-without-Cripplegate is a Church of England church in the City of London, located within the modern Barbican complex. When built it stood without the city wall, near the Cripplegate. The church is dedicated to St Giles, patron saint of beggars and cripples...

in Cripplegate.

Archery

Archery is the art, practice, or skill of propelling arrows with the use of a bow, from Latin arcus. Archery has historically been used for hunting and combat; in modern times, however, its main use is that of a recreational activity...

. In Records of St. Giles' Cripplegate (1883), the author describes an order made by Henry VII

Henry VII of England

Henry VII was King of England and Lord of Ireland from his seizing the crown on 22 August 1485 until his death on 21 April 1509, as the first monarch of the House of Tudor....

to convert Finsbury Fields from gardens, to fields for archery practice, however in Elizabethan times archery became unfashionable, and Grub Street is described as largely deserted, "except for low gambling houses and bowling-alleys—or, as we should call them, skittle-grounds." John Stow

John Stow

John Stow was an English historian and antiquarian.-Early life:The son of Thomas Stow, a tallow-chandler, he was born about 1525 in London, in the parish of St Michael, Cornhill. His father's whole rent for his house and garden was only 6s. 6d. a year, and Stow in his youth fetched milk every...

also referred to Grubstreete in A Survey of London Volume II (1603) as "It was convenient for bowyers, since it lay near the Archery-butts in Finsbury Fields", and in 1651 the poet Thomas Randoph

Thomas Randolph (poet)

Thomas Randolph was an English poet and dramatist. He was baptized on 18 June 1605 and was the uncle of American colonist William Randolph.-Education:...

wrote "Her eyes are Cupid's Grub-Street: the blind archer, Makes his love-arrows there." The little London directory of 1677 lists six merchants living in 'Grubſreet', and Costermonger

Costermonger

Costermonger, or simply Coster, is a street seller of fruit and vegetables, in London and other British towns. They were ubiquitous in mid-Victorian England, and some are still found in markets. As usual with street-sellers, they would use a loud sing-song cry or chant to attract attention...

s also plied their trade—a Mr Horton, who died in September 1773, earned a fortune of £2,000 by hiring wheelbarrows out. Land was cheap and occupied mostly by the poor, and the area was renowned for the presence of Ague

Fever

Fever is a common medical sign characterized by an elevation of temperature above the normal range of due to an increase in the body temperature regulatory set-point. This increase in set-point triggers increased muscle tone and shivering.As a person's temperature increases, there is, in...

and the Black Death

Black Death

The Black Death was one of the most devastating pandemics in human history, peaking in Europe between 1348 and 1350. Of several competing theories, the dominant explanation for the Black Death is the plague theory, which attributes the outbreak to the bacterium Yersinia pestis. Thought to have...

; in the 1660s the Great Plague of London

Great Plague of London

The Great Plague was a massive outbreak of disease in the Kingdom of England that killed an estimated 100,000 people, 20% of London's population. The disease is identified as bubonic plague, an infection by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, transmitted through a flea vector...

killed nearly eight thousand of the parish's inhabitants.

The population of St Giles in 1801 has been estimated at about 25,000 people, but by the end of the 19th century this was dropping steadily. In the 18th century Cripplegate

Cripplegate

Cripplegate was a city gate in the London Wall and a name for the region of the City of London outside the gate. The area was almost entirely destroyed by bombing in World War II and today is the site of the Barbican Estate and Barbican Centre...

was well-known as an area haunted by insalubrious folk, and by the mid 19th-century crime was rife. Methods of dealing with criminals were severe—thieves and murderers were "left dangling in their chains on Moorfields." The use of gibbet

Gibbet

A gibbet is a gallows-type structure from which the dead bodies of executed criminals were hung on public display to deter other existing or potential criminals. In earlier times, up to the late 17th century, live gibbeting also took place, in which the criminal was placed alive in a metal cage...

s was common, and four 'cages' were maintained by the parish, for use as a Lying-in

Lying-in

Lying-in is an old childbirth practice involving a woman resting in bed for a period of time after giving birth. Though the term is now usually defined as "the condition of a woman in the process of giving birth," it previously referred to a period of bed rest required even if there were no...

hospital, housing the poor, and 'idle imposters'. One such cage stood amidst the poor quality housing stock of Grub Street; destitution was viewed as a crime against society, and was punishable by whipping, and also by having a hole cut in the gristle of the right ear.

Well before the influx of writers in the 18th century, Grub street was therefore in an economically deprived area. John Garfield's Wandring Whore issue V (1660) lists several 'Crafty Bawds' operating from the Three Sugar-Loaves, and also mentions a Mrs Wroth as a 'common whore'.

Early literature

The earliest literary reference to Grub Street appears in 1630, by the EnglishEnglish people

The English are a nation and ethnic group native to England, who speak English. The English identity is of early mediaeval origin, when they were known in Old English as the Anglecynn. England is now a country of the United Kingdom, and the majority of English people in England are British Citizens...

poet

Poet

A poet is a person who writes poetry. A poet's work can be literal, meaning that his work is derived from a specific event, or metaphorical, meaning that his work can take on many meanings and forms. Poets have existed since antiquity, in nearly all languages, and have produced works that vary...

, John Taylor

John Taylor (poet)

John Taylor was an English poet who dubbed himself "The Water Poet".-Biography:He was born in Gloucester, 24 August 1578....

. "When strait I might descry, The Quintescence of Grubstreet, well distild Through Cripplegate in a contagious Map". The local population was known for its nonconformist views; its Presbyterian preacher Samuel Annesley

Samuel Annesley

Samuel Annesley was a prominent Puritan and nonconformist pastor, best known for the sermons he collected as the series of Morning Exercises.-Life:...

had been replaced in 1662 by an Anglican. Famous 16th-century Puritan

Puritan

The Puritans were a significant grouping of English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries. Puritanism in this sense was founded by some Marian exiles from the clergy shortly after the accession of Elizabeth I of England in 1558, as an activist movement within the Church of England...

s included John Foxe

John Foxe

John Foxe was an English historian and martyrologist, the author of what is popularly known as Foxe's Book of Martyrs, , an account of Christian martyrs throughout Western history but emphasizing the sufferings of English Protestants and proto-Protestants from the fourteenth century through the...

, who may have authored his Book of Martyrs

Foxe's Book of Martyrs

The Book of Martyrs, by John Foxe, more accurately Acts and Monuments, is an account from a Protestant point of view of Christian church history and martyrology...

in the area, the historian John Speed

John Speed

John Speed was an English historian and cartographer.-Life:He was born at Farndon, Cheshire, and went into his father's tailoring business where he worked until he was about 50...

, the Protestant printer and poet Robert Crowley

Robert Crowley (printer)

Robert Crowley also Robertus Croleus, Roberto Croleo, Robart Crowleye, Robarte Crole, and Crule , was a stationer, poet, polemicist and Protestant clergyman who was among the Marian exiles at Frankfurt...

. The Protestant John Milton

John Milton

John Milton was an English poet, polemicist, a scholarly man of letters, and a civil servant for the Commonwealth of England under Oliver Cromwell...

also lived near Grub Street.

Press freedom

In 1403 the City of London Corporation approved the formation of a Guild of stationers. Stationers were either booksellers, illuminatorsIlluminated manuscript

An illuminated manuscript is a manuscript in which the text is supplemented by the addition of decoration, such as decorated initials, borders and miniature illustrations...

, or bookbinders

Bookbinding

Bookbinding is the process of physically assembling a book from a number of folded or unfolded sheets of paper or other material. It usually involves attaching covers to the resulting text-block.-Origins of the book:...

. Printing

Printing

Printing is a process for reproducing text and image, typically with ink on paper using a printing press. It is often carried out as a large-scale industrial process, and is an essential part of publishing and transaction printing....

gradually displaced manuscript production, and by the time that the Guild received a royal charter of incorporation on May 4, 1557, becoming the Stationers' Company

Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers

The Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers is one of the Livery Companies of the City of London. The Stationers' Company was founded in 1403; it received a Royal Charter in 1557...

, it was in effect a Printers' Guild. In 1559, it became the 47th livery company

Livery Company

The Livery Companies are 108 trade associations in the City of London, almost all of which are known as the "Worshipful Company of" the relevant trade, craft or profession. The medieval Companies originally developed as guilds and were responsible for the regulation of their trades, controlling,...

.

The Stationers' Company had considerable powers of search and seizure, backed by the state (which supplied the force and authority to guarantee copyright). This monopoly continued until 1641 when, inflamed by the treatment of religious dissenters such as John Lilburne

John Lilburne

John Lilburne , also known as Freeborn John, was an English political Leveller before, during and after English Civil Wars 1642-1650. He coined the term "freeborn rights", defining them as rights with which every human being is born, as opposed to rights bestowed by government or human law...

and William Prynne

William Prynne

William Prynne was an English lawyer, author, polemicist, and political figure. He was a prominent Puritan opponent of the church policy of the Archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud. Although his views on church polity were presbyterian, he became known in the 1640s as an Erastian, arguing for...

, the Long Parliament

Long Parliament

The Long Parliament was made on 3 November 1640, following the Bishops' Wars. It received its name from the fact that through an Act of Parliament, it could only be dissolved with the agreement of the members, and those members did not agree to its dissolution until after the English Civil War and...

abolished the Star Chamber

Star Chamber

The Star Chamber was an English court of law that sat at the royal Palace of Westminster until 1641. It was made up of Privy Counsellors, as well as common-law judges and supplemented the activities of the common-law and equity courts in both civil and criminal matters...

(a court which controlled the press) with the Habeas Corpus Act 1640

Habeas Corpus Act 1640

The Habeas Corpus Act 1640 is an Act of the Parliament of England with the long title "An Act for the Regulating the Privie Councell and for taking away the Court commonly called the Star Chamber." The Act was passed by the Long Parliament shortly after the impeachment and execution of Thomas...

. This led to the de facto cessation of state censorship of the press. Although in 1641 token punishments were given to those responsible for unlicensed and hostile pamphlets published around London—including Grub Street—Puritan

Puritan

The Puritans were a significant grouping of English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries. Puritanism in this sense was founded by some Marian exiles from the clergy shortly after the accession of Elizabeth I of England in 1558, as an activist movement within the Church of England...

and radical pamphlets continued to be distributed by an informal network of street hawkers, and dissenters from within the Stationers' Company. Tabloid journalism became rife; the unstable political climate resulted in the publication from Grub Street of anti-Caroline

Charles I of England

Charles I was King of England, King of Scotland, and King of Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. Charles engaged in a struggle for power with the Parliament of England, attempting to obtain royal revenue whilst Parliament sought to curb his Royal prerogative which Charles...

literature, along with blatant lies and anti-Catholic stories regarding the Irish Rebellion of 1641

Irish Rebellion of 1641

The Irish Rebellion of 1641 began as an attempted coup d'état by Irish Catholic gentry, who tried to seize control of the English administration in Ireland to force concessions for the Catholics living under English rule...

; stories that were advantageous to the parliamentary leadership. Following the King's failed attempt to arrest several members of the Commons, Grub Street printer Bernard Alsop became personally involved in the publication of false pamphlets, including a fake letter from the Queen that resulted in John Bond

John Bond (jurist)

John Bond LL.D. was an English jurist, Puritan clergyman, member of the Westminster Assembly, and Master of Trinity Hall, Cambridge.-Life:...

being pilloried

Pillory

The pillory was a device made of a wooden or metal framework erected on a post, with holes for securing the head and hands, formerly used for punishment by public humiliation and often further physical abuse, sometimes lethal...

. Alsop and colleague Thomas Fawcett were sent to Fleet Prison

Fleet Prison

Fleet Prison was a notorious London prison by the side of the Fleet River in London. The prison was built in 1197 and was in use until 1844. It was demolished in 1846.- History :...

for several months.

Throughout the English Civil War

English Civil War

The English Civil War was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between Parliamentarians and Royalists...

therefore, publishers and writers remained answerable to the law. State control of the press was tightened in the Licensing Order of 1643

Licensing Order of 1643

The Licensing Order of 1643 instituted pre-publication censorship upon Parliamentary England. Milton's Areopagitica was written specifically against this Act.-Abolition of the Star Chamber:...

, but although the new regime was arguably as restrictive as the monopoly that the Stationers' Company once enjoyed, parliament was unable to control the number of renegade presses that flourished during the Interregnum

English Interregnum

The English Interregnum was the period of parliamentary and military rule by the Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell under the Commonwealth of England after the English Civil War...

. The freedoms ensured by the Bill of Rights 1689

Bill of Rights 1689

The Bill of Rights or the Bill of Rights 1688 is an Act of the Parliament of England.The Bill of Rights was passed by Parliament on 16 December 1689. It was a re-statement in statutory form of the Declaration of Right presented by the Convention Parliament to William and Mary in March 1689 ,...

led indirectly to the refusal in 1695 of the Parliament of England

Parliament of England

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England. In 1066, William of Normandy introduced a feudal system, by which he sought the advice of a council of tenants-in-chief and ecclesiastics before making laws...

to renew the Licensing of the Press Act 1662

Licensing of the Press Act 1662

The Licensing of the Press Act 1662 is an Act of the Parliament of England , long title "An Act for preventing the frequent Abuses in printing seditious treasonable and unlicensed Bookes and Pamphlets and for regulating of Printing and Printing Presses." It was repealed by the Statute Law Revision...

, a law which required all printing presses to be licensed by Parliament. This lapse led to a freer press, and a rise in the volume of printed matter. Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift was an Irish satirist, essayist, political pamphleteer , poet and cleric who became Dean of St...

wrote to a friend in New York

New York

New York is a state in the Northeastern region of the United States. It is the nation's third most populous state. New York is bordered by New Jersey and Pennsylvania to the south, and by Connecticut, Massachusetts and Vermont to the east...

, "I could send you a great deal of news from the Republica Grubstreetaria, which was never in greater altitude."

Hacks

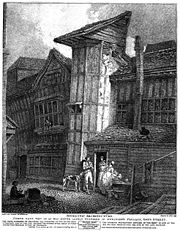

Attic

An attic is a space found directly below the pitched roof of a house or other building . Attic is generally the American/Canadian reference to it...

, meant that the area was an ideal home for hack writers. In The Preface, when describing the harsh conditions a writer suffered, Tom Brown

Tom Brown (satirist)

Tom Brown was an English translator and writer of satire, largely forgotten today save for a four-line gibe he wrote concerning Dr John Fell....

's self-parody referred to being "Block'd up in a Garret". Such contemporary views of the writer, in his inexpensive Ivory Tower

Ivory Tower

The term Ivory Tower originates in the Biblical Song of Solomon , and was later used as an epithet for Mary.From the 19th century it has been used to designate a world or atmosphere where intellectuals engage in pursuits that are disconnected from the practical concerns of everyday life...

high above the noise of the city, were immortalised by William Hogarth

William Hogarth

William Hogarth was an English painter, printmaker, pictorial satirist, social critic and editorial cartoonist who has been credited with pioneering western sequential art. His work ranged from realistic portraiture to comic strip-like series of pictures called "modern moral subjects"...

in his 1736 illustration The Distrest Poet

The Distrest Poet

The Distrest Poet is an oil painting produced sometime around 1736 by the British artist William Hogarth. Reproduced as an etching and engraving, it was published in 1741 from a third state plate produced in 1740. The scene was probably inspired by Alexander Pope's satirical poem The Dunciad...

. The street name became a synonym for a hack writer; in a literary context, 'hack' is derived from Hackney—a person whose services may be for hire, especially a literary drudge. In this framework, hack was popularised by authors such as Andrew Marvell

Andrew Marvell

Andrew Marvell was an English metaphysical poet, Parliamentarian, and the son of a Church of England clergyman . As a metaphysical poet, he is associated with John Donne and George Herbert...

, Oliver Goldsmith

Oliver Goldsmith

Oliver Goldsmith was an Irish writer, poet and physician known for his novel The Vicar of Wakefield , his pastoral poem The Deserted Village , and his plays The Good-Natur'd Man and She Stoops to Conquer...

, John Wolcot

John Wolcot

John Wolcot , satirist, born in Dodbrooke, near Kingsbridge in Devon, was educated by an uncle, and studied medicine. In 1767 he went as physician to Sir William Trelawny, Governor of Jamaica, and whom he induced to present him to a Church in the island then vacant, and was ordained in 1769...

, and Anthony Trollope

Anthony Trollope

Anthony Trollope was one of the most successful, prolific and respected English novelists of the Victorian era. Some of his best-loved works, collectively known as the Chronicles of Barsetshire, revolve around the imaginary county of Barsetshire...

. Ned Ward

Ned Ward

Ned Ward , also known as Edward Ward, was a satirical writer and publican in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century based in London, England. His most famous work is The London Spy. Published in 18 monthly instalments starting in November 1698 it was described as a "complete survey" of...

's late 17th-century description reinforces a common view of Grub Street authors, as little more than prostitutes:

One such author was Samuel Boyse

Samuel Boyse

Samuel Boyse was an Irish poet and writer who worked for Sir Robert Walpole and whose religious verses in particular were prized and reprinted in his time.-Life:...

. Contemporary accounts picture him as a dishonest and disreputable rogue, paid for each individual line of prose as a Jack of all trades, master of none

Jack of all trades, master of none

"Jack of all trades, master of none" is a figure of speech used in reference to a person that is competent with many skills but is not necessarily outstanding in any particular one....

. He apparently lived in squalor, often drunk, and on one occasion after pawning his shirt, he fashioned a replacement out of paper. To be a called a 'Grub Street author' was therefore often viewed as an insult, however Grub Street hack James Ralph

James Ralph

This article is about the eighteenth-century American/British writer. For the cricket player, see James Ralph .James Ralph was an American born English political writer, historian, reviewer, and Grub Street hack writer known for his works of history and his position in Alexander Pope's Dunciad B. ...

defended the trade of the journalist, contrasting it with the supposed hypocrisy of more esteemed professions:

Periodicals

In response to the newly increased demand for reading matter in the Augustan periodAugustan literature

Augustan literature is a style of English literature produced during the reigns of Queen Anne, King George I, and George II on the 1740s with the deaths of Pope and Swift...

, Grub Street became a popular source of periodical

Periodical publication

Periodical literature is a published work that appears in a new edition on a regular schedule. The most familiar examples are the newspaper, often published daily, or weekly; or the magazine, typically published weekly, monthly or as a quarterly...

literature. One publication to take advantage of the reduction of state control was A Perfect Diurnall (despite its title, a weekly publication). However it quickly found its name copied by unscrupulous Grub Street publishers, so obviously that the newspaper was forced to issue a warning to its readers. Toward the end of the 17th century authors such as John Dunton

John Dunton

John Dunton was an English bookseller and author. In 1691, he founded an Athenian Society to publish The Athenian Mercury, the first major popular periodical and first miscellaneous periodical in England.-Early life:...

worked on a range of periodicals, including Pegasus (1696), and The Night Walker: or, Evening Rambles in search after lewd Women (1696–1697). Dunton pioneered the advice column

Advice column

An advice column is a column in a magazine or newspaper written by an advice columnist . The image presented was originally of an older woman providing comforting advice and maternal wisdom, hence the name "aunt"...

in Athenian Mercury (1690–1697). The satirical writer and publican Ned Ward

Ned Ward

Ned Ward , also known as Edward Ward, was a satirical writer and publican in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century based in London, England. His most famous work is The London Spy. Published in 18 monthly instalments starting in November 1698 it was described as a "complete survey" of...

published The London Spy (1698–1700) in monthly instalments, for over a year and a half. It was conceived as a guide to the sights of the city, but as a periodical also contained details on taverns, coffee-houses, tobacco shops, and bagnio

Bagnio

A Bagnio was originally a bath or bath-house.The term was then used to name the prison for hostages in Istanbul, which was near the bath-house, and thereafter all the slave prisons in the Ottoman Empire and the Barbary regencies...

s.

Tory

Toryism is a traditionalist and conservative political philosophy which grew out of the Cavalier faction in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. It is a prominent ideology in the politics of the United Kingdom, but also features in parts of The Commonwealth, particularly in Canada...

Rehearsal (1704–1709), both superseded by Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe , born Daniel Foe, was an English trader, writer, journalist, and pamphleteer, who gained fame for his novel Robinson Crusoe. Defoe is notable for being one of the earliest proponents of the novel, as he helped to popularise the form in Britain and along with others such as Richardson,...

's Weeky Review (1704–1713), and Jonathan Swift's Examiner (1710–1714). English newspapers were often politically sponsored, and Grub Street was host to several such publications; between 1731 and 1741 Robert Walpole

Robert Walpole

Robert Walpole, 1st Earl of Orford, KG, KB, PC , known before 1742 as Sir Robert Walpole, was a British statesman who is generally regarded as having been the first Prime Minister of Great Britain....

's ministry was reported to have spent about £50,077 (about £ today) nationally of Treasury

HM Treasury

HM Treasury, in full Her Majesty's Treasury, informally The Treasury, is the United Kingdom government department responsible for developing and executing the British government's public finance policy and economic policy...

funds on bribes to such newspapers. Allegiances changed often, with some authors changing their political stance on receipt of bribes from secret service funds. Such changes helped maintain the level of disdain with which the establishment viewed journalists and their trade, an attitude often reinforced by the abuse publications would print about their rivals. Titles such as Common Sense, Daily Post, and the Jacobite's Journal (1747–1748) were often guilty of this practice, and in May 1756 an anonymous author described journalists as "dastardly mongrel insects, scribbling incendiaries, starveling savages, human shaped tygers, senseless yelping curs..." In describing his profession, Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson , often referred to as Dr. Johnson, was an English author who made lasting contributions to English literature as a poet, essayist, moralist, literary critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer...

, a Grub Street man himself, said "A news-writer is a man without virtue who writes lies at home for his own profit. To these compositions is required neither genius nor knowledge, neither industry nor sprightliness, but contempt of shame and indifference to truth are absolutely necessary."

Taxation

In 1711 Queen AnneAnne of Great Britain

Anne ascended the thrones of England, Scotland and Ireland on 8 March 1702. On 1 May 1707, under the Act of Union, two of her realms, England and Scotland, were united as a single sovereign state, the Kingdom of Great Britain.Anne's Catholic father, James II and VII, was deposed during the...

gave royal assent to the 1712 Stamp Act, which imposed new taxes on newspapers. The Queen addressed the House of Commons: "Her majesty finds it necessary to observe, how great license is taken in publishing false and scandalous libels, such as are a reproach to any Government. This evil seems to be grown too strong for the laws now in force. It is therefore recommended to you to find a remedy equal to the mischief." The passage of the Act was partly an attempt to silence Whig pamphleteers and dissenters, who had been critical of the then Tory government. Every copy of a news-carrying publication printed on a half-sheet of paper became liable to a duty of a halfpenny, and if printed on a full sheet, a penny. A duty of a shilling was placed on advertisements. Pamphlets were charged a flate rate of two shillings per sheet for each edition, and were obliged to include the name and address of the printer. The introduction of the Act caused protests from publishers and authors alike, including Daniel Defoe, and Jonathan Swift, who in support of the Whig press wrote:

By the 1720s 'Grub Street' had grown from a simple street name, to a term used to describe all manner of low-level publishing. The popularity of Nathaniel Mist

Nathaniel Mist

Nathaniel Mist was an 18th century British printer and journalist whose Mist's Weekly Journal was the central, most visible, and most explicit opposition newspaper to the whig administrations of Robert Walpole. Where other opposition papers would defer, Mist's would explicitly attack the...

's Weekly Journal gave rise to a plethora of new publications, including the Universal Spectator (1728), the Anglican Weekly Miscellany (1732), the Old Whig (1735), Common Sense (1737), and the Westminster Journal. Such publications could be strident in their criticism of government ministers—Common Sense in 1737 compared Walpole to the infamous outlaw Dick Turpin

Dick Turpin

Richard "Dick" Turpin was an English highwayman whose exploits were romanticised following his execution in York for horse theft. Turpin may have followed his father's profession as a butcher early in life, but by the early 1730s he had joined a gang of deer thieves, and later became a poacher,...

:

In response, a 1737 edition of the Craftsman proposed a tax on urine, and ten years later the Westminster Journal, in a critique of proposed new taxes on food, servants, and malt, proposed a tax on human excrement. Not all publications were based entirely on politics however; the Grub Street Journal was better known in literary circles for its combative nature, and has been compared to the modern-day Private Eye

Private Eye

Private Eye is a fortnightly British satirical and current affairs magazine, edited by Ian Hislop.Since its first publication in 1961, Private Eye has been a prominent critic and lampooner of public figures and entities that it deemed guilty of any of the sins of incompetence, inefficiency,...

. Despite its name, it was printed on nearby Warwick Lane. It began in 1730 as a literary journal and became known for its bellicose writings on individual authors. It is considered by some to have been a vehicle for Alexander Pope's attacks on his enemies in Grub Street, but although he contributed to early issues the full extent of his involvement is unknown. Once his interest in the publication waned The Journal began to generalise, satirising medicine, theology, theatre, justice, and other social issues. It often contained contradictory accounts of events reported by the previous week's newspapers, its writers inserting sarcastic remarks on the inaccuracies printed by their rivals. It ran until 1737 when it became the Literary Courier of Grub-street, which lingered for a further six months before vanishing altogether.

John Wilkes

John Wilkes was an English radical, journalist and politician.He was first elected Member of Parliament in 1757. In the Middlesex election dispute, he fought for the right of voters—rather than the House of Commons—to determine their representatives...

was charged with seditious libel

Seditious libel

Seditious libel was a criminal offence under English common law. Sedition is the offence of speaking seditious words with seditious intent: if the statement is in writing or some other permanent form it is seditious libel...

for his attacks on a speech by George III

George III of the United Kingdom

George III was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of these two countries on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland until his death...

, in issue 45 of The North Briton

The North Briton

The North Briton was a radical newspaper published in 18th century London. The North Briton also served as the pseudonym of the newspaper's author, used in advertisements, letters to other publications, and handbills....

. The King felt personally insulted and general warrants

Writ of Assistance

A writ of assistance is a written order issued by a court instructing a law enforcement official, such as a sheriff, to perform a certain task. Historically, several types of writs have been called "writs of assistance". Most often, a writ of assistance is "used to enforce an order for the...

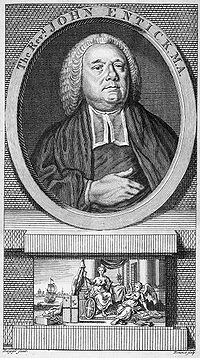

were issued for the arrest of Wilkes and the newspaper's publishers. He was arrested, convicted of libel, fined, and imprisoned. During their search for Wilkes, the king's messengers had visited the home of a Grub Street printer named John Entick

John Entick

John Entick was an English schoolmaster and author. He was largely a hack writer, working for Edward Dilly, and he padded his credentials with a bogus M.A. and a portrait in clerical dress; some of his works had a more lasting value...

. Entick had printed several copies of The North Briton, but not number 45. The messengers spent four hours searching his home, and eventually carried away more than two hundred unrelated charts and pamphlets. Wilkes had filed for damages against the Under Secretary of State

Under Secretary of State

The Under Secretary of State, from 1919 to 1972, was the second-ranking official at the United States Department of State , serving as the Secretary's principal deputy, chief assistant, and Acting Secretary in the event of the Secretary's absence...

Robert Woods and won his case, and two years later Entick pursued

Entick v Carrington

Entick v Carrington [1765] is a leading case in English law establishing the civil liberties of individuals and limiting the scope of executive power. The case has also been influential in other common law jurisdictions and was an important motivation for the Fourth Amendment to the United States...

the chief messenger Nicholas Carrington in similar fashion—and was awarded £2,000 in compensation. Carrington appealed, but was ultimately unsuccessful; Chief Justice Camden

Charles Pratt, 1st Earl Camden

Charles Pratt, 1st Earl Camden was an English lawyer, judge and Whig politician who was first to hold the title of Earl of Camden...

upheld the verdict with a landmark judgement that established the limits of executive power in English law, that an officer of the state could only act lawfully in a manner prescribed by statute or common law

Common law

Common law is law developed by judges through decisions of courts and similar tribunals rather than through legislative statutes or executive branch action...

. The judgement also formed part of the background to the Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution

Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution is the part of the Bill of Rights which guards against unreasonable searches and seizures, along with requiring any warrant to be judicially sanctioned and supported by probable cause...

.

Infighting

Edmund Curll

Edmund Curll was an English bookseller and publisher. His name has become synonymous, through the attacks on him by Alexander Pope, with unscrupulous publication and publicity. Curll rose from poverty to wealth through his publishing, and he did this by approaching book printing in a mercenary...

acquired a manuscript that belonged to Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope was an 18th-century English poet, best known for his satirical verse and for his translation of Homer. He is the third-most frequently quoted writer in The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, after Shakespeare and Tennyson...

. Curll advertised the work as part of a forthcoming volume of poetry, and was soon contacted by Pope who warned him not to publish the poems. Curll ignored him and published Pope's work under the title Court Poems. A meeting between the two was arranged, at which Pope poisoned Curll with an emetic. Several days later he also published two pamphlets describing the meeting, and proclaimed Curll's death. Pope hoped that the combination of the poisoning and the wit of his writing would change the public view of Curll from a victim, to a deserving villain. Meanwhile, Curll responded by publishing material critical of Pope and his religion. The incident, meant to secure Pope's status as an elevated figure amongst his peers, created a lifelong and bitter rivalry between the two men, but may have been beneficial to both; Pope as the man of letters under constant attack from the hacks of Grub Street, and Curll using the incident to increase the profits from his business.

Pope later immortalised Grub Street in his 1728 poem The Dunciad

The Dunciad

The Dunciad is a landmark literary satire by Alexander Pope published in three different versions at different times. The first version was published in 1728 anonymously. The second version, the Dunciad Variorum was published anonymously in 1729. The New Dunciad, in four books and with a...

, a satire of "the Grub-street Race" of commercial writers. Such infighting was not unusual, but a particularly notable episode occurred from 1752–1753, when Henry Fielding

Henry Fielding

Henry Fielding was an English novelist and dramatist known for his rich earthy humour and satirical prowess, and as the author of the novel Tom Jones....

started a "paper war" against hack writers on Grub Street. Fielding had worked in Grub Street during the late 1730s. His career as a dramatist was curtailed by the Theatrical Licensing Act

Licensing Act 1737

The Licensing Act or Theatrical Licensing Act of 21 June 1737 was a landmark act of censorship of the British stage and one of the most determining factors in the development of Augustan drama...

(provoked by Fielding's anti-Walpole satire such as Tom Thumb

Tom Thumb

Tom Thumb is a character of English folklore. The History of Tom Thumb was published in 1621, and has the distinction of being the first fairy tale printed in English. Tom is no bigger than his father's thumb, and his adventures include being swallowed by a cow, tangling with giants, and becoming a...

and Covent Garden Tragedy) and he turned to law, supporting his income with normal Grub Street work. He also launched The Champion, and over the following years edited several newspapers, including from 1752–1754 The Covent-Garden Journal

The Covent-Garden Journal

The Covent-Garden Journal was an English literary periodical published twice a week for most of 1752. It was edited and almost entirely financed by novelist, playwright, and essayist Henry Fielding, under the pseudonym "Sir Alexander Drawcansir, Knt. Censor of Great Britain"...

. The "war" spanned many of London's publications, and resulted in countless essays, poems, and even a series of mock epic poems starting with Christopher Smart

Christopher Smart

Christopher Smart , also known as "Kit Smart", "Kitty Smart", and "Jack Smart", was an English poet. He was a major contributor to two popular magazines and a friend to influential cultural icons like Samuel Johnson and Henry Fielding. Smart, a high church Anglican, was widely known throughout...

's The Hilliad

The Hilliad

The Hilliad was Christopher Smart's mock epic poem written as a literary attack upon John Hill on 1 February 1753. The title is a play on Alexander Pope's The Dunciad with a substitution of Hill's name, which represents Smart's debt to Pope for the form and style of The Hilliad...

(a pun on Pope's Dunciad). Although it is not clear what started the dispute, it resulted in a divide of authors who either supported Fielding or Hill, and few in between.

The avariciousness of the Grub Street press was often demonstrated in the manner in which they treated notable, or notorious public figures. John Church, an independent minister born in 1780, raised the ire of the local hacks when he admitted he had acted 'imprudently' following allegations he had sodomised young men in his congregation. Satire was a popular pastime—the Mary Toft affair of 1726, concerning a woman who fooled some of the medical establishment into believing she had given birth to rabbits—produced a notable dirge of diaries, letters, satiric poems, ballads, false confessions, cartoons, and pamphlets.

Later history

Grub Street was renamed as Milton Street in 1830, apparently in memory of a tradesman who owned the building lease of the street. By the middle of the 19th century it had lost some of its negative connotations; authors were by that time viewed in the same light as traditionally more esteemed professions, although 'Grub Street' remained a metaphor for the commercial production of printed matter, regardless of whether such matter actually originated from Grub Street itself.Writer George Augustus Henry Sala

George Augustus Henry Sala

George Augustus Henry Sala , English journalist.-Biography:Sala was born in London; his father being the son of an Italian who came to London to arrange ballets at the theatres, and his mother an actress and teacher of singing...

said that during his years as a Grub Street 'hack',"...most of us were about the idlest young dogs that squandered away their time on the pavements of Paris or London. We would not work. I declare in all candour that...the average number of hours per week which I devoted to literary production did not exceed four." (Cross, 94)

Although the street no longer exists in name (modern construction has changed much of the area), the name continues to exist in modern use. Much of the area was destroyed by enemy bombing in World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, and has since been replaced by the Barbican Estate

Barbican Estate

The Barbican Estate is a residential estate built during the 1960s and the 1970s in the City of London, in an area once devastated by World War II bombings and today densely populated by financial institutions...

. Milton Street borders the City of London's Brewery Conservation Area.

Legacy

As Grub Street became a metaphor for the commercial production of printed matter, it gradually found use in early 18th-century AmericaUnited States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

. Early publications such as handwritten ditties and squibs were circulated among the gentry

Gentry

Gentry denotes "well-born and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past....

and taverns and coffee-houses. As in England, many were directed at politicians of the day.

See also

- Grub Street in FranceGrub Street in FranceThe term "Grub Street" refers to a street in London, England where a high number of struggling writers lived in the 18th century. Eventually, the term became a metonym for hack writers. Although the term was used in the 18th century to refer to English hacks, in the 20th century the term was...

- List of eighteenth-century British periodicals

- New Grub StreetNew Grub StreetNew Grub Street is a novel by George Gissing published in 1891, which is set in the literary and journalistic circles of 1880s London. Gissing revised and shortened the novel for a French edition of 1901....

— a novel by George GissingGeorge GissingGeorge Robert Gissing was an English novelist who published twenty-three novels between 1880 and 1903. From his early naturalistic works, he developed into one of the most accomplished realists of the late-Victorian era.-Early life:...

, set in late-19th-century London—which contrasts a pragmatic journalist with an impoverished writer and examines the tension between commerce and art in the literary world. - The Grub Street OperaThe Grub Street OperaThe Grub-Street Opera is a play by Henry Fielding that originated as an expanded version of his play, The Welsh Opera. It was never put on for an audience and is Fielding's single print-only play. As in The Welsh Opera, the author of the play is identified as Scriblerus Secundus. Secundus also...

- Ernest BramahErnest BramahErnest Bramah , born Ernest Brammah Smith, was an English author. He published 21 books and numerous short stories and features. His humorous works were ranked with Jerome K Jerome, and W.W. Jacobs, his detective stories with Conan Doyle, his politico-science fiction with H.G. Wells and his...

— a Grub Street author. - Tobias SmollettTobias SmollettTobias George Smollett was a Scottish poet and author. He was best known for his picaresque novels, such as The Adventures of Roderick Random and The Adventures of Peregrine Pickle , which influenced later novelists such as Charles Dickens.-Life:Smollett was born at Dalquhurn, now part of Renton,...

Further reading

- Eisenstein, ElizabethElizabeth EisensteinElizabeth Lewisohn Eisenstein is an American historian of the French Revolution and early 19th century France. She is well-known for her work on the history of early printing, writing on the transition in media between the era of 'manuscript culture' and that of 'print culture', as well as the role...

. Grub Street Abroad: Aspects of the French Cosmopolitan Press from the Age of Louis XIV to the French Revolution (1992) - McDowell, Paula. The Women of Grub Street: Press, Politics and Gender in the London Literary Marketplace, 1678-1730 (1998)