Great Britain in the Seven Years War

Encyclopedia

Kingdom of Great Britain

The former Kingdom of Great Britain, sometimes described as the 'United Kingdom of Great Britain', That the Two Kingdoms of Scotland and England, shall upon the 1st May next ensuing the date hereof, and forever after, be United into One Kingdom by the Name of GREAT BRITAIN. was a sovereign...

was one of the major participants in the Seven Years' War

Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War was a global military war between 1756 and 1763, involving most of the great powers of the time and affecting Europe, North America, Central America, the West African coast, India, and the Philippines...

which lasted between 1756 and 1763. Britain emerged from the war as the world's leading colonial power having gained a number of new territories at the Treaty of Paris

Treaty of Paris (1763)

The Treaty of Paris, often called the Peace of Paris, or the Treaty of 1763, was signed on 10 February 1763, by the kingdoms of Great Britain, France and Spain, with Portugal in agreement. It ended the French and Indian War/Seven Years' War...

in 1763 and established itself as the world's pre-eminent naval power.

The war started poorly for Britain, suffering several defeats to France

Kingdom of France

The Kingdom of France was one of the most powerful states to exist in Europe during the second millennium.It originated from the Western portion of the Frankish empire, and consolidated significant power and influence over the next thousand years. Louis XIV, also known as the Sun King, developed a...

in North America

North America

North America is a continent wholly within the Northern Hemisphere and almost wholly within the Western Hemisphere. It is also considered a northern subcontinent of the Americas...

during 1754-55 and losing Minorca

Minorca

Min Orca or Menorca is one of the Balearic Islands located in the Mediterranean Sea belonging to Spain. It takes its name from being smaller than the nearby island of Majorca....

in 1756. The same year Britain's major ally Austria

Austria

Austria , officially the Republic of Austria , is a landlocked country of roughly 8.4 million people in Central Europe. It is bordered by the Czech Republic and Germany to the north, Slovakia and Hungary to the east, Slovenia and Italy to the south, and Switzerland and Liechtenstein to the...

switched sides and aligned itself with France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

; and Britain was hastily forced to conclude a new alliance

Anglo-Prussian Alliance

The Anglo-Prussian Alliance was a military alliance created by the Westminster Convention between Great Britain and Prussia which lasted formally between 1756 and 1762 during the Seven Years' War. It allowed Britain to concentrate the majority of its efforts against the colonial possessions of the...

with Frederick the Great's Prussia

Prussia

Prussia was a German kingdom and historic state originating out of the Duchy of Prussia and the Margraviate of Brandenburg. For centuries, the House of Hohenzollern ruled Prussia, successfully expanding its size by way of an unusually well-organized and effective army. Prussia shaped the history...

. For the next seven years these two nations were ranged against a growing number of enemy powers led by France. After a period of political instability, the rise of a government

Second Newcastle Ministry

The Second Newcastle Ministry was a British government which served between 1757 and 1762, at the height of the Seven Years War. It was headed by the Duke of Newcastle, who was serving in his second term as Prime Minister...

headed by the Duke of Newcastle and William Pitt provided Britain with firmer leadership allowing it to consolidate and achieve its war aims.

In 1759 Britain enjoyed an Annus Mirabilis

Annus Mirabilis of 1759

The Annus Mirabilis of 1759 took place in the context of the Seven Years' War and Great Britain's military success against French-led opponents on several continents...

with success over the French

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

on the Continent (Germany), in North America (reducing some enemy colonies

New France

New France was the area colonized by France in North America during a period beginning with the exploration of the Saint Lawrence River by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Spain and Great Britain in 1763...

as well as defending her own

Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies were English and later British colonies established on the Atlantic coast of North America between 1607 and 1733. They declared their independence in the American Revolution and formed the United States of America...

), and in India. In 1761 Britain also came into conflict with Spain. The following year they captured Havana

Havana

Havana is the capital city, province, major port, and leading commercial centre of Cuba. The city proper has a population of 2.1 million inhabitants, and it spans a total of — making it the largest city in the Caribbean region, and the most populous...

and Manila

Manila

Manila is the capital of the Philippines. It is one of the sixteen cities forming Metro Manila.Manila is located on the eastern shores of Manila Bay and is bordered by Navotas and Caloocan to the north, Quezon City to the northeast, San Juan and Mandaluyong to the east, Makati on the southeast,...

, the western and eastern capitals of the Spanish Empire

Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire comprised territories and colonies administered directly by Spain in Europe, in America, Africa, Asia and Oceania. It originated during the Age of Exploration and was therefore one of the first global empires. At the time of Habsburgs, Spain reached the peak of its world power....

and repulsed a Spanish invasion of Portugal

Spanish invasion of Portugal (1762)

The Spanish invasion of Portugal, between 9 May and 24 November 1762, was the principal military campaign of the Spanish–Portuguese War, 1761–1763, which in turn was part of the larger Seven Years' War...

. By this time the Pitt-Newcastle Ministry had collapsed, Britain was short of credit

Credit (finance)

Credit is the trust which allows one party to provide resources to another party where that second party does not reimburse the first party immediately , but instead arranges either to repay or return those resources at a later date. The resources provided may be financial Credit is the trust...

and the generous peace terms offered by France and its allies were accepted.

Through the crown, Britain was allied to the Electorate of Hanover

Electorate of Hanover

The Electorate of Brunswick-Lüneburg was the ninth Electorate of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation...

and Kingdom of Ireland

Kingdom of Ireland

The Kingdom of Ireland refers to the country of Ireland in the period between the proclamation of Henry VIII as King of Ireland by the Crown of Ireland Act 1542 and the Act of Union in 1800. It replaced the Lordship of Ireland, which had been created in 1171...

, both of which effectively fell under British military command throughout the war. It also directed the military strategy of its various colonies around the world including British America

British America

For American people of British descent, see British American.British America is the anachronistic term used to refer to the territories under the control of the Crown or Parliament in present day North America , Central America, the Caribbean, and Guyana...

. In India

India

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

British possessions were administered by the East India Company

British East India Company

The East India Company was an early English joint-stock company that was formed initially for pursuing trade with the East Indies, but that ended up trading mainly with the Indian subcontinent and China...

.

Background

.jpg)

War of the Austrian Succession

The War of the Austrian Succession – including King George's War in North America, the Anglo-Spanish War of Jenkins' Ear, and two of the three Silesian wars – involved most of the powers of Europe over the question of Maria Theresa's succession to the realms of the House of Habsburg.The...

, had ended in 1748 with the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle

Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (1748)

The Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle of 1748 ended the War of the Austrian Succession following a congress assembled at the Imperial Free City of Aachen—Aix-la-Chapelle in French—in the west of the Holy Roman Empire, on 24 April 1748...

, following a bloody war which had left large parts of Central Europe

Central Europe

Central Europe or alternatively Middle Europe is a region of the European continent lying between the variously defined areas of Eastern and Western Europe...

devastated. The peace terms were unpopular with many, however, as they largely retained the status quo

Status quo

Statu quo, a commonly used form of the original Latin "statu quo" – literally "the state in which" – is a Latin term meaning the current or existing state of affairs. To maintain the status quo is to keep the things the way they presently are...

- which led the people of states such as France, Britain and Austria to believe they had not made sufficient gains for their efforts in the war. By the early 1750s many saw another major war as imminent, and Austria was preparing its forces for an attempt to retake Silesia

Silesia

Silesia is a historical region of Central Europe located mostly in Poland, with smaller parts also in the Czech Republic, and Germany.Silesia is rich in mineral and natural resources, and includes several important industrial areas. Silesia's largest city and historical capital is Wrocław...

from Prussia

Prussia

Prussia was a German kingdom and historic state originating out of the Duchy of Prussia and the Margraviate of Brandenburg. For centuries, the House of Hohenzollern ruled Prussia, successfully expanding its size by way of an unusually well-organized and effective army. Prussia shaped the history...

.

The British Prime Minister, the Duke of Newcastle

Duke of Newcastle

Duke of Newcastle-upon-Tyne is a title which has been created three times in British history while the title of Duke of Newcastle-under-Lyne has been created once. The title was created for the first time in the Peerage of England in 1664 when William Cavendish, 1st Marquess of Newcastle-upon-Tyne...

, had acceded to the Premiership in 1754 following the sudden death of his brother Henry Pelham

Henry Pelham

Henry Pelham was a British Whig statesman, who served as Prime Minister of Great Britain from 27 August 1743 until his death in 1754...

, and led a government made up largely of Whigs. Newcastle had thirty years experience as a Secretary of State and was a leading figure on the diplomatic scene. Despite enjoying a comfortable majority in the House of Commons

House of Commons of Great Britain

The House of Commons of Great Britain was the lower house of the Parliament of Great Britain between 1707 and 1801. In 1707, as a result of the Acts of Union of that year, it replaced the House of Commons of England and the third estate of the Parliament of Scotland, as one of the most significant...

he was extremely cautious and vulnerable to attacks led by men such as William Pitt

William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham

William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham PC was a British Whig statesman who led Britain during the Seven Years' War...

, leader of the Patriot Party

Patriot Whigs

The Patriot Whigs and, later Patriot Party, was a group within the Whig party in Great Britain from 1725 to 1803. The group was formed in opposition to the ministry of Robert Walpole in the House of Commons in 1725, when William Pulteney and seventeen other Whigs joined with the Tory party in...

. Newcastle fervently believed that peace in Europe was possible so long as the old system and the alliance with Austria

Anglo-Austrian Alliance

The Anglo-Austrian Alliance connected the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Habsburg monarchy during the first half of the 18th century. It was largely the work of the British statesman Duke of Newcastle, who considered an alliance with Austria crucial to prevent the further expansion of French...

prevailed and devoted much of his efforts to the continuance of this.

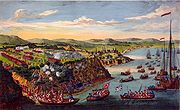

One of the major concerns for the British government of the era was colonial expansion. During the eighteenth century the British colonies in North America

British America

For American people of British descent, see British American.British America is the anachronistic term used to refer to the territories under the control of the Crown or Parliament in present day North America , Central America, the Caribbean, and Guyana...

had become more populous and powerful - and were agitating to expand westwards into the American interior. The territory most prized by the new settlers was the Ohio Country

Ohio Country

The Ohio Country was the name used in the 18th century for the regions of North America west of the Appalachian Mountains and in the region of the upper Ohio River south of Lake Erie...

, which was also claimed by France. As well as having economic potential, it was considered strategically key. French control of that territory would block British expansion westwards and eventually French territory would surround the British colonies, pinning them against the coast. A number of colonial delegations to London urged the government to take more decisive action in the Ohio dispute.

War in North America

Initial skirmishes (1754–55)

The Ohio countryOhio Country

The Ohio Country was the name used in the 18th century for the regions of North America west of the Appalachian Mountains and in the region of the upper Ohio River south of Lake Erie...

located between Britain's Thirteen Colonies

Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies were English and later British colonies established on the Atlantic coast of North America between 1607 and 1733. They declared their independence in the American Revolution and formed the United States of America...

and France's New France

New France

New France was the area colonized by France in North America during a period beginning with the exploration of the Saint Lawrence River by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Spain and Great Britain in 1763...

saw France and Britain clash. In 1753 the French sent an expedition south from Montreal

Montreal

Montreal is a city in Canada. It is the largest city in the province of Quebec, the second-largest city in Canada and the seventh largest in North America...

that began constructing forts in the upper reaches of the Ohio River

Ohio River

The Ohio River is the largest tributary, by volume, of the Mississippi River. At the confluence, the Ohio is even bigger than the Mississippi and, thus, is hydrologically the main stream of the whole river system, including the Allegheny River further upstream...

. In 1754 the Province of Virginia sent the Virginia Regiment

Virginia Regiment

The Virginia Regiment was formed in 1754 by Virginia's Royal Governor Robert Dinwiddie, initially as an all volunteer militia corps, and he promoted George Washington, the future first president of the United States of America, to its command upon the death of Colonel Joshua Fry...

led by George Washington

George Washington

George Washington was the dominant military and political leader of the new United States of America from 1775 to 1799. He led the American victory over Great Britain in the American Revolutionary War as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army from 1775 to 1783, and presided over the writing of...

to the area to assist in the construction of a British fort at present-day Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Pittsburgh is the second-largest city in the US Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and the county seat of Allegheny County. Regionally, it anchors the largest urban area of Appalachia and the Ohio River Valley, and nationally, it is the 22nd-largest urban area in the United States...

, but the larger French force had driven away a smaller British advance team and built Fort Duquesne

Fort Duquesne

Fort Duquesne was a fort established by the French in 1754, at the junction of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers in what is now downtown Pittsburgh in the state of Pennsylvania....

. Washington and some native allies ambushed a company of French scouts at the Battle of Jumonville Glen

Battle of Jumonville Glen

The Battle of Jumonville Glen, also known as the Jumonville affair, was the opening battle of the French and Indian War fought on May 28, 1754 near what is present-day Uniontown in Fayette County, Pennsylvania...

in late May 1754. In the skirmish the French envoy Joseph Coulon de Villiers de Jumonville was left dead, leading to a diplomatic incident. The French responded in force from Fort Duquesne, and in July Washington was forced to surrender at the Battle of Fort Necessity. Despite the conflict between them, the two nations were not yet formally at war.

Braddock Expedition (1755)

The government in Britain, realising that the existing forces of America were insufficient, drew up a plan to dispatch two battalions of IrishKingdom of Ireland

The Kingdom of Ireland refers to the country of Ireland in the period between the proclamation of Henry VIII as King of Ireland by the Crown of Ireland Act 1542 and the Act of Union in 1800. It replaced the Lordship of Ireland, which had been created in 1171...

regular troops under General Edward Braddock

Edward Braddock

General Edward Braddock was a British soldier and commander-in-chief for the 13 colonies during the actions at the start of the French and Indian War...

and intended to massively increase the number of Provincial American forces. A number of expeditions were planned to give the British the upper hand in North America including a plan for New England

New England

New England is a region in the northeastern corner of the United States consisting of the six states of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut...

troops to defeat Fort Beausejour

Fort Beauséjour

Fort Beauséjour, was built during Father Le Loutre's War from 1751-1755; it is located at the Isthmus of Chignecto in present-day Aulac, New Brunswick, Canada...

and Fortress Louisbourg in Acadia

Acadia

Acadia was the name given to lands in a portion of the French colonial empire of New France, in northeastern North America that included parts of eastern Quebec, the Maritime provinces, and modern-day Maine. At the end of the 16th century, France claimed territory stretching as far south as...

, and others to act against Fort Niagara

Fort Niagara

Fort Niagara is a fortification originally built to protect the interests of New France in North America. It is located near Youngstown, New York, on the eastern bank of the Niagara River at its mouth, on Lake Ontario.-Origin:...

and Fort St. Frédéric

Fort St. Frédéric

Fort St. Frédéric was a French fort built on Lake Champlain at Crown Point to secure the region against British colonization and to allow the French to control the use of Lake Champlain....

from Albany, New York

Albany, New York

Albany is the capital city of the U.S. state of New York, the seat of Albany County, and the central city of New York's Capital District. Roughly north of New York City, Albany sits on the west bank of the Hudson River, about south of its confluence with the Mohawk River...

. The largest operation was a plan for Braddock to dislodge the French from the Ohio Country

Ohio Country

The Ohio Country was the name used in the 18th century for the regions of North America west of the Appalachian Mountains and in the region of the upper Ohio River south of Lake Erie...

.

In May 1755 Braddock's column blundered into an enemy force composed of French and Native Americans at the Battle of the Monongahela

Battle of the Monongahela

The Battle of the Monongahela, also known as the Battle of the Wilderness, took place on 9 July 1755, at the beginning of the French and Indian War, at Braddock's Field in what is now Braddock, Pennsylvania, east of Pittsburgh...

near Fort Duquesne

Fort Duquesne

Fort Duquesne was a fort established by the French in 1754, at the junction of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers in what is now downtown Pittsburgh in the state of Pennsylvania....

. After several hours fighting the British were defeated and forced to retreat with Braddock dying a few days later of his wounds. The remainder of his force returned to Philadelphia and took up quarters intending no further action that year. The French remained in control of the Ohio Country

Ohio Country

The Ohio Country was the name used in the 18th century for the regions of North America west of the Appalachian Mountains and in the region of the upper Ohio River south of Lake Erie...

.

In the Maritime Theatre, the British were successful in the Battle of Fort Beausejour

Battle of Fort Beauséjour

The Battle of Fort Beauséjour was fought on the Isthmus of Chignecto and marked the end of Father Le Loutre’s War andthe opening of a British offensive in the French and Indian War, which would eventually lead to the end the French Empire in North America...

, and in their campaign to remove the French military threat from Acadia. Subsequent to the battle the British began the Great Expulsion called the Bay of Fundy Campaign (1755)

Bay of Fundy Campaign (1755)

The Bay of Fundy Campaign occurred during the French and Indian War when the British ordered the Expulsion of the Acadians from Acadia after the Battle of Beausejour . The Campaign started at Chignecto and then quickly moved to Grand Pré, Rivière-aux-Canards, Pisiguit, Cobequid, and finally Port...

by the British, with the intent of preventing Acadian support of the French supply lines to Louisbourg. The British forcibly relocated 12,000 French-speakers. Two additional expeditions from Albany each failed to reach their objectives, although one, William Johnson's expedition, did establish Fort William Henry

Fort William Henry

Fort William Henry was a British fort at the southern end of Lake George in the province of New York. It is best known as the site of notorious atrocities committed by Indians against the surrendered British and provincial troops following a successful French siege in 1757, an event which is the...

and held off a French attempt on Fort Edward

Fort Edward (village), New York

Fort Edward is a village in Washington County, New York, United States. It is part of the Glens Falls Metropolitan Statistical Area. The village population was 3,141 at the 2000 census...

in the Battle of Lake George

Battle of Lake George

The Battle of Lake George was fought on 8 September 1755, in the north of the Province of New York. The battle was part of a campaign by the British to expel the French from North America in the French and Indian War....

.

When news of the Braddock disaster reached Britain it caused a massive public outcry over the government's poor military preparation. The government appointed William Shirley

William Shirley

William Shirley was a British colonial administrator who served twice as Governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay and as Governor of the Bahamas in the 1760s...

as the new Commander-in-Chief in North America, and planned an equally ambitious series of operations for the following year.

Further struggles in North America (1756–58)

New France

New France was the area colonized by France in North America during a period beginning with the exploration of the Saint Lawrence River by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Spain and Great Britain in 1763...

, they were unable to exert this advantage partly due to a successful campaign by the French to recruit Native American

Indigenous peoples of the Americas

The indigenous peoples of the Americas are the pre-Columbian inhabitants of North and South America, their descendants and other ethnic groups who are identified with those peoples. Indigenous peoples are known in Canada as Aboriginal peoples, and in the United States as Native Americans...

allies who raided the unprotected frontier of the Thirteen Colonies

Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies were English and later British colonies established on the Atlantic coast of North America between 1607 and 1733. They declared their independence in the American Revolution and formed the United States of America...

. The British raised regiments of local militia

Militia

The term militia is commonly used today to refer to a military force composed of ordinary citizens to provide defense, emergency law enforcement, or paramilitary service, in times of emergency without being paid a regular salary or committed to a fixed term of service. It is a polyseme with...

and shipped in more regular forces from Britain and Ireland.

Despite these increased forces Britain continued to fare badly in the battle for control of the Ohio Country and the nearby Great Lakes

Great Lakes

The Great Lakes are a collection of freshwater lakes located in northeastern North America, on the Canada – United States border. Consisting of Lakes Superior, Michigan, Huron, Erie, and Ontario, they form the largest group of freshwater lakes on Earth by total surface, coming in second by volume...

, and none of their campaigns was successful in 1756. After losing the Battle of Fort Oswego, not only that fort, but others in the Mohawk River

Mohawk River

The Mohawk River is a river in the U.S. state of New York. It is the largest tributary of the Hudson River. The Mohawk flows into the Hudson in the Capital District, a few miles north of the city of Albany. The river is named for the Mohawk Nation of the Iroquois Confederacy...

valley were abandoned. This was followed in 1757 by the fall of Fort William Henry and the Indian atrocities that followed. News of this disaster sent a fresh wave of panic around the British colonies, and the entire militia of New England was mobilised overnight.

In the Maritime Theatre, a raid was organized on Lunenburg, Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is one of Canada's three Maritime provinces and is the most populous province in Atlantic Canada. The name of the province is Latin for "New Scotland," but "Nova Scotia" is the recognized, English-language name of the province. The provincial capital is Halifax. Nova Scotia is the...

and several on the Chignecto

Isthmus of Chignecto

The Isthmus of Chignecto is an isthmus bordering the Maritime provinces of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia which connects the Nova Scotia peninsula with North America....

. A British attempt to take Louisbourg in 1757

Louisbourg Expedition (1757)

The Louisbourg Expedition was a failed British attempt to capture the French fortress of Louisbourg on Île Royale during the Seven Years' War ....

failed due to bad weather and poor planning. The following year, in part because of having expelled many Acadians, the Siege of Louisbourg (1758)

Siege of Louisbourg (1758)

The Siege of Louisbourg was a pivotal battle of the Seven Years' War in 1758 which ended the French colonial era in Atlantic Canada and led directly to the loss of Quebec in 1759 and the remainder of French North America the following year.-Background:The British government realized that with the...

succeeded, clearing the way for an advance on Quebec. Immediately after the fall of Louisbourg the expulsion of the Acadians continued with the removal of Acadians in the St. John River Campaign

St. John River Campaign

The St. John River Campaign occurred during the French and Indian War when Colonel Robert Monckton led a force of 1150 British soldiers to destroy the Acadian settlements along the banks of the Saint John River until they reached the largest village of Sainte-Anne des Pays-Bas in February 1759...

, the Petitcodiac River Campaign

Petitcodiac River Campaign

The Petitcodiac River Campaign was a series of British military operations from June to November 1758, during the French and Indian War, to deport the Acadians that either lived along the Petitcodiac River or had taken refuge there from earlier deportation operations, such as the Ile Saint-Jean...

, the Ile Saint-Jean Campaign

Ile Saint-Jean Campaign

The Ile Saint-Jean Campaign was a series of military operations in fall 1758, during the French and Indian War, to deport the Acadians that either lived on Ile Saint-Jean or had taken refuge there from earlier deportation operations...

, and the Gulf of St. Lawrence Campaign (1758)

Gulf of St. Lawrence Campaign (1758)

The Gulf of St. Lawrence Campaign occurred during the French and Indian War when British forces raided villages along present-day New Brunswick and the Gaspé Peninsula coast of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. Sir Charles Hardy and Brigadier-General James Wolfe were in command of the naval and...

.

By this point the war in North America had reached a stalemate, with France broadly holding the territorial advantage. It held possession of the disputed Ohio territory but lacked the strength to launch an attack on the more populous British coastal colonies.

One of the most significant geopolitical actions of the time was the slow movement towards Imperial unity in North America started by the Albany Congress

Albany Congress

The Albany Congress, also known as the Albany Conference and "The Conference of Albany" or "The Conference in Albany", was a meeting of representatives from seven of the thirteen British North American colonies in 1754...

, although a Plan of Union

Albany Plan

The Albany Plan of Union was proposed by Benjamin Franklin at the Albany Congress in 1754 in Albany, New York. It was an early attempt at forming a union of the colonies "under one government as far as might be necessary for defense and other general important purposes" during the French and...

proposed by Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin

Dr. Benjamin Franklin was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. A noted polymath, Franklin was a leading author, printer, political theorist, politician, postmaster, scientist, musician, inventor, satirist, civic activist, statesman, and diplomat...

was rejected by delegates.

Stately Quadrille

Britain had been allied to Austria since 1731, and the co-operation between the two states had peaked during the War of the Austrian SuccessionWar of the Austrian Succession

The War of the Austrian Succession – including King George's War in North America, the Anglo-Spanish War of Jenkins' Ear, and two of the three Silesian wars – involved most of the powers of Europe over the question of Maria Theresa's succession to the realms of the House of Habsburg.The...

when Maria Theresa

Maria Theresa of Austria

Maria Theresa Walburga Amalia Christina was the only female ruler of the Habsburg dominions and the last of the House of Habsburg. She was the sovereign of Austria, Hungary, Croatia, Bohemia, Mantua, Milan, Lodomeria and Galicia, the Austrian Netherlands and Parma...

had been able to retain her throne with British assistance. Since then the relationship had weakened - as Austria was dissatisfied with the terms negotiated by Britain for them at the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle

Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (1748)

The Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle of 1748 ended the War of the Austrian Succession following a congress assembled at the Imperial Free City of Aachen—Aix-la-Chapelle in French—in the west of the Holy Roman Empire, on 24 April 1748...

. Prussia had captured Silesia

Silesia

Silesia is a historical region of Central Europe located mostly in Poland, with smaller parts also in the Czech Republic, and Germany.Silesia is rich in mineral and natural resources, and includes several important industrial areas. Silesia's largest city and historical capital is Wrocław...

from Austria during the war and Austria wanted British help to recover it. Sensing that it would not be forthcoming, the Austrians approached their historical enemies France and made a defensive treaty with them - thereby dissolving the twenty five year Anglo-Austrian Alliance

Anglo-Austrian Alliance

The Anglo-Austrian Alliance connected the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Habsburg monarchy during the first half of the 18th century. It was largely the work of the British statesman Duke of Newcastle, who considered an alliance with Austria crucial to prevent the further expansion of French...

.

Alarmed by the sudden switch in the European Balance of Power

European balance of power

The Balance of Power in Europe is an international relations concept that applies historically and currently to the nations of Europe...

the British made a similar agreement with Prussia

Prussia

Prussia was a German kingdom and historic state originating out of the Duchy of Prussia and the Margraviate of Brandenburg. For centuries, the House of Hohenzollern ruled Prussia, successfully expanding its size by way of an unusually well-organized and effective army. Prussia shaped the history...

at the Westminster Convention. By doing this Newcastle hoped to rebalance the two sides in Central Europe - and thereby make a war potentially mutually destructive to all. This he hoped would stop either Austria or Prussia making an attack on the other and would prevent an all-out war in Europe. This would allow Britain and France to continue their colonial skirmishes without formal war being declared in Europe. Frederick the Great had a number of supporters in London, including William Pitt who welcomed the rapprochement between Britain and Prussia. The Dutch Republic

Dutch Republic

The Dutch Republic — officially known as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands , the Republic of the United Netherlands, or the Republic of the Seven United Provinces — was a republic in Europe existing from 1581 to 1795, preceding the Batavian Republic and ultimately...

, a long-standing ally of Britain, declared their neutrality in the wake of the Westminster Convention and had no active participation in the coming conflict.

Fall of Minorca

As the war in Europe appeared to become more inevitable, the Newcastle government took steps to try to take the initiative – and make sure that the strategic island of MinorcaMinorca

Min Orca or Menorca is one of the Balearic Islands located in the Mediterranean Sea belonging to Spain. It takes its name from being smaller than the nearby island of Majorca....

was secured before it fell into French hands. A relief expedition was dispatched under Admiral John Byng

John Byng

Admiral John Byng was a Royal Navy officer. After joining the navy at the age of thirteen he participated at the Battle of Cape Passaro in 1718. Over the next thirty years he built up a reputation as a solid naval officer and received promotion to Vice-Admiral in 1747...

to save it. However, once he arrived in the Mediterranean Byng found an equally-sized French fleet and a 15,000-strong army besieging the fortress

Siege of Minorca

The Siege of Fort St Philip took place in 1756 during the Seven Years War.- Siege :...

. After fighting an indecisive battle

Battle of Minorca

The Battle of Minorca was a naval battle between French and British fleets. It was the opening sea battle of the Seven Years' War in the European theatre. Shortly after Great Britain declared war on the House of Bourbon, their squadrons met off the Mediterranean island of Minorca. The fight...

he withdrew to Gibraltar

Gibraltar

Gibraltar is a British overseas territory located on the southern end of the Iberian Peninsula at the entrance of the Mediterranean. A peninsula with an area of , it has a northern border with Andalusia, Spain. The Rock of Gibraltar is the major landmark of the region...

, and Minorca subsequently fell. Formal war was finally declared in May 1756, almost exactly two years after the two countries had first clashed in Ohio.

Byng was recalled to Britain and court-martialled. There was violent public outrage about the loss of Minorca, mostly directed against Newcastle. He tried to deflect the blame by emphasising the alleged cowardice of Byng. After being tried by his peers, the Admiral was eventually executed by firing squad for “not doing his utmost“. By that time Newcastle and his government had fallen. It was replaced by a weaker administration headed by the Duke of Devonshire

William Cavendish, 4th Duke of Devonshire

William Cavendish, 4th Duke of Devonshire, KG, PC , styled Lord Cavendish before 1729 and Marquess of Hartington between 1729 and 1755, was a British Whig statesman who was briefly nominal Prime Minister of Great Britain...

and dominated by William Pitt.

Prussian Alliance

Saxony

The Free State of Saxony is a landlocked state of Germany, contingent with Brandenburg, Saxony Anhalt, Thuringia, Bavaria, the Czech Republic and Poland. It is the tenth-largest German state in area, with of Germany's sixteen states....

. Having occupied it he then launched a similarly bold invasion of Bohemia

Bohemia

Bohemia is a historical region in central Europe, occupying the western two-thirds of the traditional Czech Lands. It is located in the contemporary Czech Republic with its capital in Prague...

. In both cases the Prussians caught their Austrian enemies by surprise, and had used this advantage to full effect, capturing major objectives before Austrian troops had been fully mobilised. Having besieged Prague

Siege of Prague

The Siege of Prague was an unsuccessful attempt by a Prussian army led by Frederick the Great to capture the Austrian city of Prague during the Seven Years' War. It took place in May 1757 immediately after the Battle of Prague. Despite having won that battle, Frederick had lost 14,300 dead, and his...

, an Austrian counter-attack and a defeat at the Battle of Kolin

Battle of Kolin

-Results:The battle was Frederick's first defeat in this war. This disaster forced him to abandon his intended march on Vienna, raise his siege of Prague, and fall back on Litoměřice...

forced the Prussians back.

Britain found itself bound by the Westminster Convention and entered the war on the Prussian side. Newcastle was deeply reluctant to do this, but he saw that a Prussian collapse would be disastrous to British and Hanoverian interests. The Anglo-Prussian Alliance

Anglo-Prussian Alliance

The Anglo-Prussian Alliance was a military alliance created by the Westminster Convention between Great Britain and Prussia which lasted formally between 1756 and 1762 during the Seven Years' War. It allowed Britain to concentrate the majority of its efforts against the colonial possessions of the...

was established, which saw large amounts of subsidy given to Prussia. Some supporters of George II were strong advocates of support for Prussia, as they saw it would be impossible to defend his realm of Hanover if they were to be defeated. Despite his initial dislike of Frederick, the King later moved towards this viewpoint.

British intervention on the Continent

Within a short time Prussia was being attacked on four fronts, by AustriaAustria

Austria , officially the Republic of Austria , is a landlocked country of roughly 8.4 million people in Central Europe. It is bordered by the Czech Republic and Germany to the north, Slovakia and Hungary to the east, Slovenia and Italy to the south, and Switzerland and Liechtenstein to the...

from the south, France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

from the west, Russia

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

from the east, and Sweden from the north. Frederick fought defensive actions trying to blunt the invaders, losing thousands of men and precious resources in the process. He began to send more urgent appeals to London for material help on the continent.

When the war with France had commenced, Britain had initially brought Hessian and Hanoverian troops to defend Britain from a feared invasion scare. When the threat of this receded, the German soldiers were sent to defend Hanover along with a small contingent of British troops under Duke of Cumberland, the King's second son. The arrival of British troops on the continent was considered a rarity, as the country preferred to make war by using its naval forces. As with the Prussians, Cumberland's army was initially overwhelmed by the sheer scale of the French attacks. Following the disastrous Battle of Hastenbeck

Battle of Hastenbeck

The Battle of Hastenbeck was fought as part of the Invasion of Hanover during the Seven Year's War between the allied forces of Hanover, Hesse-Kassel and Brunswick and the French...

Cumberland was forced to sign the Convention of Klosterzeven

Convention of Klosterzeven

The Convention of Klosterzeven was a 1757 convention signed at Klosterzeven between France and the Electorate of Hanover during the Seven Years' War that led to Hanover's withdrawal from the war and partial occupation by French forces. It came in the wake of the Battle of Hastenbeck in which...

by which Hanover would withdraw from the war - and large chunks of its territory would be occupied by the French for the duration of the conflict.

Prussia was extremely alarmed by this development and lobbied hard for it to be reversed. In London too, there was shock at such a capitulation and Pitt recalled Cumberland to London where he was publicly rebuked by his father, the King, and forced to relinquish his commission. The terms of Klosterzeven were revoked, Hanover re-entered the war - and a new commander was selected to command the Allied Anglo-German forces. Ferdinand of Brunswick

Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick

Ferdinand, Prince of Brunswick-Lüneburg , was a Prussian field marshal known for his participation in the Seven Years' War...

was a brother-in-law of Frederick the Great, and had developed a reputation as a competent officer. He set about trying to rally the German troops under his command, by emphasising the extent of the atrocities committed by the French troops who had occupied Hanover, and launched a counter-offensive in late 1757 driving the French back across the Rhine.

Despite several British attempts to persuade them, the Dutch Republic

Dutch Republic

The Dutch Republic — officially known as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands , the Republic of the United Netherlands, or the Republic of the Seven United Provinces — was a republic in Europe existing from 1581 to 1795, preceding the Batavian Republic and ultimately...

refused to join their former allies in the war and remained neutral. Pitt at one point even feared that the Dutch would enter the war against Britain, in response to repeated violations of Dutch neutrality by the Royal Navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

. Similarly the British were wary of Denmark joining the war against them, but Copenhagen followed a policy of strict neutrality.

Change of government

Henry Fox, 1st Baron Holland

Henry Fox, 1st Baron Holland, of Foxley, MP, PC was a leading British politician of the 18th century. He identified primarily with the Whig faction...

and the Duke of Bedford

John Russell, 4th Duke of Bedford

John Russell, 4th Duke of Bedford KG, PC, FRS was an 18th century British statesman. He was the fourth son of Wriothesley Russell, 2nd Duke of Bedford, by his wife, Elizabeth, daughter and heiress of John Howland of Streatham, Surrey...

were also given positions in the administration.

The new government's strategic thinking was sharply divided. Pitt had been a long-term advocate of Britain playing as small a role on the European continent while concentrating their resources and naval power to strike against vulnerable French colonies. Newcastle remained an old-school Continentalist - who believed that the war would be decided in Europe, and was convinced that a strong British presence there was essential. He was supported in this view by George II

George II of Great Britain

George II was King of Great Britain and Ireland, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg and Archtreasurer and Prince-elector of the Holy Roman Empire from 11 June 1727 until his death.George was the last British monarch born outside Great Britain. He was born and brought up in Northern Germany...

.

A compromise was eventually established in which Britain would keep troops on the European continent under the command of the Duke of Brunswick

Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick

Ferdinand, Prince of Brunswick-Lüneburg , was a Prussian field marshal known for his participation in the Seven Years' War...

, while Pitt was given authority to launch several colonial expeditions. He sent forces to attack French settlements in West Africa

West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of the African continent. Geopolitically, the UN definition of Western Africa includes the following 16 countries and an area of approximately 5 million square km:-Flags of West Africa:...

and the West Indies, operations which were tactically successful and brought financial benefits. In Britain a popular surge of patriotism

Patriotism

Patriotism is a devotion to one's country, excluding differences caused by the dependencies of the term's meaning upon context, geography and philosophy...

and support for the government resulted. Pitt formed a triumvirate

Triumvirate

A triumvirate is a political regime dominated by three powerful individuals, each a triumvir . The arrangement can be formal or informal, and though the three are usually equal on paper, in reality this is rarely the case...

to direct operations with George Anson

George Anson, 1st Baron Anson

Admiral of the Fleet George Anson, 1st Baron Anson PC, FRS, RN was a British admiral and a wealthy aristocrat, noted for his circumnavigation of the globe and his role overseeing the Royal Navy during the Seven Years' War...

in command of the navy and John Ligonier in charge of the army. A Militia Act was passed to create a sizable force to defend Britain which would free up regular troops for operations overseas.

Naval "Descents"

The British had received several requests from their German allies to try to relieve the pressure on them by launching diversionary operations against the French. Pitt had long been an advocate of amphibious strikes or "descents" against the French coastline in which a small British force would land, capture a settlement, destroy its fortifications and munitions supplies and then withdraw. This would compel the French to withdraw troops from the Northern front to guard the coast.After an urgent request from Brunswick, Pitt was able to put his plan into action, and in September 1757 a British raid

Raid on Rochefort

The Raid on Rochefort was a British amphibious attempt to capture the French Atlantic port of Rochefort in September 1757 during the Seven Years War...

was launched against Rochefort

Rochefort, Charente-Maritime

Rochefort is a commune in southwestern France, a port on the Charente estuary. It is a sub-prefecture of the Charente-Maritime department.-History:...

in Western France. For various reasons it was not a success, but Pitt was determined to press ahead with similar raids. Another British expedition was organised under Lord Sackville. A landing

Raid on St Malo

The Raid on St Malo took place in June 1758 when an amphibious British naval expedition landed close to the French port of St Malo in Brittany. While the town itself was not attacked, as had been initially planned, the British destroyed large amounts of shipping before re-embarking a week later...

in St Malo was partially successful, but was cut short by the sudden appearance of French troops – and the force withdrew to Britain. Pitt organised a third major descent, under the command of Thomas Bligh

Thomas Bligh

Thomas Bligh was a British soldier, best known for his service during the Seven Years' War when he led a series of amphibious raids, known as "descents" on the French coastline...

. His raid on Cherbourg

Raid on Cherbourg

The Raid on Cherbourg took place in August 1758 during the Seven Year's War when a British force was landed on the coast of France by the Royal Navy with the intention of attacking the town of Cherbourg as part of the British government's policy of "descents" on the French Coast.-Background:Since...

in August 1758 proved to be the most successful of the descents, as he burnt ships and munitions and destroyed the fortifications of the town. However, an attempt in September to do the same at St Malo ended with the Battle of St Cast and the British withdrawing with heavy casualties. This proved to be the last of the major landings attempted on the French coast – though the British later took control of the Belle Île

Belle Île

Belle-Île or Belle-Île-en-Mer is a French island off the coast of Brittany in the département of Morbihan, and the largest of Brittany's islands. It is 14 km from the Quiberon peninsula.Administratively, the island forms a canton: the canton of Belle-Île...

off the coast of Brittany

Brittany

Brittany is a cultural and administrative region in the north-west of France. Previously a kingdom and then a duchy, Brittany was united to the Kingdom of France in 1532 as a province. Brittany has also been referred to as Less, Lesser or Little Britain...

which was used as a base for marshalling troops and supplies. The raids were not financially successful and were described by Henry Fox

Henry Fox, 1st Baron Holland

Henry Fox, 1st Baron Holland, of Foxley, MP, PC was a leading British politician of the 18th century. He identified primarily with the Whig faction...

as being "like breaking windows with guineas

Guinea (British coin)

The guinea is a coin that was minted in the Kingdom of England and later in the Kingdom of Great Britain and the United Kingdom between 1663 and 1813...

". From then on the British concentrated their efforts in Europe on Germany.

Indian Campaign (1756–58)

Britain and France both had significant colonial possessions in IndiaIndia

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

and had been battling for supremacy for a number of years. The British were represented by the British East India Company

British East India Company

The East India Company was an early English joint-stock company that was formed initially for pursuing trade with the East Indies, but that ended up trading mainly with the Indian subcontinent and China...

(EIC) who were permitted to raise troops. The collapse of the long-standing Mughal Empire

Mughal Empire

The Mughal Empire , or Mogul Empire in traditional English usage, was an imperial power from the Indian Subcontinent. The Mughal emperors were descendants of the Timurids...

brought the clash between the two states to a head, as each tried to gain sufficient power and territory to dominate the other. The 1754 Treaty of Pondicherry

Treaty of Pondicherry

The Treaty of Pondicherry was signed in 1754 bringing an end to the Second Carnatic War. It was agreed and signed in the French settlement of Pondicherry in French India. The favoured British candidate Mohamed Ali Khan Walajan was recognized as the Nawab of the Carnatic...

which ended the Second Carnatic War had brought a temporary truce to India, but it was soon under threat. A number of smaller Indian Princely States aligned with either Britain or France. One of the most assertive of these Princes was the pro-French Nawab of Bengal

Nawab of Bengal

The Nawabs of Bengal were the hereditary nazims or subadars of the subah of Bengal during the Mughal rule and the de-facto rulers of the province.-History:...

, Siraj ud-Daulah

Siraj ud-Daulah

Mîrzâ Muhammad Sirâj-ud-Daulah , more commonly known as Siraj ud-Daulah , was the last independent Nawab of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa. The end of his reign marks the start of British East India Company rule over Bengal and later almost all of South Asia...

, who resented the British presence in Calcutta. In 1756 he had succeeded his grandfather Alivardi Khan

Alivardi Khan

Ali Vardi Khan was the Nawab of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa during 1740 - 1756. He toppled the Nasiri Dynasty of Bengal and took power as Nawab.-Early life:...

who had been a staunch British ally. By contrast he regarded the British East India Company

British East India Company

The East India Company was an early English joint-stock company that was formed initially for pursuing trade with the East Indies, but that ended up trading mainly with the Indian subcontinent and China...

as an encroaching threat.

Calcutta

On 20 June 1756 the Nawab's troops stormed Fort WilliamFort William, India

Fort William is a fort built in Calcutta on the Eastern banks of the River Hooghly, the major distributary of the River Ganges, during the early years of the Bengal Presidency of British India. It was named after King William III of England...

capturing the city. A number of the British civilians and prisoners of war were locked in the small guard room in what became known as the Black Hole of Calcutta

Black Hole of Calcutta

The Black Hole of Calcutta was a small dungeon in the old Fort William, at Calcutta, India, where troops of the Nawab of Bengal, Siraj ud-Daulah, held British prisoners of war after the capture of the Fort on June 19, 1756....

. After the death of many of them, the atrocity became a popular rallying call for revenge. A force from Madras under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Robert Clive arrived and liberated the city, driving out the Nawab's troops. The Third Carnatic War that followed saw Britain ranged against the Nawab and France. Clive consolidated his position in Calcutta, and made contact with one of the Nawab's chief advisors Mir Jafar

Mir Jafar

-Notes:# "Riyazu-s-salatin", Ghulam Husain Salim - a reference to the appointment of Mohanlal can be found # "Seir Muaqherin", Ghulam Husain Tabatabai - a reference to the conspiracy can be found...

attempting to persuade him and other leading Bengalis to overthrow the Nawab. After the British ambushed a column of the Nawab's troops which was approaching Calcutta on 2 February 1757, the two sides agreed the Treaty of Alinagar

Treaty of Alinagar

The Treaty of Alinagar was signed on February 9, 1757 between Robert Clive of the British East India Company and the Nawab of Bengal, Mirza Muhammad Siraj Ud Daula. Based on the terms of the accord, the Nawab would recognize all the 1717 provisions of Mughal Emperor Farrukh Siyar's firman....

which brought a temporary truce to Bengal.

Plassey

On 23 June 1757 the Nawab led a force of 50,000 into the field. Ranged against them was a much smaller Anglo-Indian force under the command of Robert Clive. The Nawab was weakened by the betrayal of Mir Jafar

Mir Jafar

-Notes:# "Riyazu-s-salatin", Ghulam Husain Salim - a reference to the appointment of Mohanlal can be found # "Seir Muaqherin", Ghulam Husain Tabatabai - a reference to the conspiracy can be found...

who had concluded a secret pact with the British before the battle - and refused to move his troops to support the Nawab. Faced with the superior firepower and discipline of the British troops – the Nawab's army was routed. After the battle Siraj ud-Daulah

Siraj ud-Daulah

Mîrzâ Muhammad Sirâj-ud-Daulah , more commonly known as Siraj ud-Daulah , was the last independent Nawab of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa. The end of his reign marks the start of British East India Company rule over Bengal and later almost all of South Asia...

was overthrown and executed by his own officers, and Mir Jafar succeeded him as Nawab. He then concluded a peace treaty with the British.

Mir Jafar himself subsequently clashed with the British for much the same reasons as Siraj ud-Daulah

Siraj ud-Daulah

Mîrzâ Muhammad Sirâj-ud-Daulah , more commonly known as Siraj ud-Daulah , was the last independent Nawab of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa. The end of his reign marks the start of British East India Company rule over Bengal and later almost all of South Asia...

had. He conspired with the Dutch East India Company

Dutch East India Company

The Dutch East India Company was a chartered company established in 1602, when the States-General of the Netherlands granted it a 21-year monopoly to carry out colonial activities in Asia...

to try to oust the British from Bengal and in 1759 invited them to send troops to aid him. The defeat of the Dutch at the Battle of Chinsurah

Battle of Chinsurah

The Battle of Chinsurah took place near Chinsurah, India on 25 November 1759 during the Seven Years' War between a force of British troops mainly of the British East India Company and a force of the Dutch East India Company which had been invited by the Nawab of Bengal Mir Jafar to help him eject...

resulted in Britain moving to have Jafar replaced with his son-in-law, who was considered more favourable to the EIC. One of the most important long-term effects of the battle was that the British received the diwan – the right to collect taxes in Bengal which was granted in 1765.

French East India Company

The French presence in India was led by the French East India CompanyFrench East India Company

The French East India Company was a commercial enterprise, founded in 1664 to compete with the British and Dutch East India companies in colonial India....

operating out of its base at Pondicherry. Its forces were under the command of Joseph François Dupleix

Joseph François Dupleix

Joseph-François, Marquis Dupleix was governor general of the French establishment in India, and the rival of Robert Clive.-Biography:Dupleix was born in Landrecies, France...

and Lally

Thomas Arthur, comte de Lally

Thomas Arthur, comte de Lally, baron de Tollendal was a French General of Irish Jacobite ancestry. He commanded French forces in India during the Seven Years War. After a failed attempt to capture Madras he lost the Battle of Wandiwash to British forces under Eyre Coote and then was forced to...

, a Jacobite. The veteran Dupleix had been in India a long time, and had established a key rapport with France's Indian allies. Lally was more newly arrived, and was seeking a swift victory over the British - and was less concerned about diplomatic sensibilities.

Following the Battle of Chandalore when Clive attacked a French trading post the French were driven completely out of Bengal. In spite of this they still had a major presence in central India, and hoped to regain the power they had lost to the British in southern India during the Second Carnatic War.

Annus Mirabilis (1759)

Apart from a few isolated victories, the war had not gone well for Britain since 1754. In all theatres except IndiaIndia

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

and North America (where Pitt's strategy had led to important gains in 1758) they were on the retreat. British agents received information about a planned French invasion which would knock Britain out of the war completely. While France starved their colonial forces of troops and supplies to concentrate them on the goal of total strategic supremacy in Europe, the British government agreed to continue their policy of shipping their own troops to fight for total victory in the colonies—leaving Britain to be guarded by the large militia

Militia (United Kingdom)

The Militia of the United Kingdom were the military reserve forces of the United Kingdom after the Union in 1801 of the former Kingdom of Great Britain and Kingdom of Ireland....

that had existed since 1757.

Madras

Following Clive's victory at Plassey and the subjugation of Bengal, Britain had not directed large resources to the Indian theatre. The French meanwhile had despatched a large force from Europe to seize the initiative on the subcontinent. The clear goal of this force was to capture Madras, which had previously fallen to the FrenchBattle of Madras

The Battle of Madras or Fall of Madras or Battle of Adyar took place in September 1746 during the War of the Austrian Succession when a French force attacked and captured the city of Madras from its British garrison....

in 1746.

In December 1758 a French force of 8,000 under the Comte de Lally

Thomas Arthur, comte de Lally

Thomas Arthur, comte de Lally, baron de Tollendal was a French General of Irish Jacobite ancestry. He commanded French forces in India during the Seven Years War. After a failed attempt to capture Madras he lost the Battle of Wandiwash to British forces under Eyre Coote and then was forced to...

descended on Madras, bottling up the 4,000 British defenders in Fort St George

Fort St George

Fort St George is the name of the first English fortress in India, founded in 1639 at the coastal city of Madras, the modern city of Chennai. The construction of the Fort provided the impetus for further settlements and trading activity, in what was originally a no man's land...

. After a hard-fought three-month siege the French were finally forced to abandon their attempt to take the city by the arrival of a British naval force carrying 600 reinforcements on 16 February 1759. Lally withdrew his troops, but it was not the end of French ambitions in southern India.

West Indies

One of Pitt's favoured strategies was a British expedition to attack the French West IndiesFrench West Indies

The term French West Indies or French Antilles refers to the seven territories currently under French sovereignty in the Antilles islands of the Caribbean: the two overseas departments of Guadeloupe and Martinique, the two overseas collectivities of Saint Martin and Saint Barthélemy, plus...

, where their richest sugar-producing colonies were situated. A British naval force of 9,000 sailed from Portsmouth in November 1758 under the command of Peregrine Hopson

Peregrine Hopson

Peregrine Thomas Hopson was a British army officer who saw extensive service during the Eighteenth Century and rose to the rank of Major General...

. Using Barbados

Barbados

Barbados is an island country in the Lesser Antilles. It is in length and as much as in width, amounting to . It is situated in the western area of the North Atlantic and 100 kilometres east of the Windward Islands and the Caribbean Sea; therein, it is about east of the islands of Saint...

as a staging point, they attacked first

Invasion of Martinique (1759)

A British invasion of Martinique took place in January 1759 when a large amphibious force under Peregrine Hopson landed on the French-held island of Martinique and unsuccessfully tried to capture it during the Seven Years War...

at Martinique

Martinique

Martinique is an island in the eastern Caribbean Sea, with a land area of . Like Guadeloupe, it is an overseas region of France, consisting of a single overseas department. To the northwest lies Dominica, to the south St Lucia, and to the southeast Barbados...

.

After failing to make enough headway, and losing troops rapidly to disease, they were forced to abandon the attempt and move to the secondary target of the British expedition Guadeloupe

Guadeloupe

Guadeloupe is an archipelago located in the Leeward Islands, in the Lesser Antilles, with a land area of 1,628 square kilometres and a population of 400,000. It is the first overseas region of France, consisting of a single overseas department. As with the other overseas departments, Guadeloupe...

. Facing a race against time before the hurricane season hit in July, a landing was forced and the town of Basse-Terre

Basse-Terre

Basse-Terre is the prefecture of Guadeloupe, an overseas region and department of France located in the Lesser Antilles...

was shelled. They looked in severe danger when a large French fleet unexpectedly arrived under Bompart

Maximin de Bompart

Maximin de Bompart, Marquis de Bompard was a French naval officer and colonial administrator who served as Governor of Martinique between 1750 and 1757. In 1759 he led a French naval force attempting to relieve Guadeloupe which was under attack from British forces during the Seven Years War...

, but on 1 May the island's defenders finally surrendered and Bompart was unable to prevent the loss of Guadeloupe.

Orders arrived from London concerning an assault on St Lucia but the commanders decided that such an attempt was unwise given the circumstances. Instead they moved to protect Antigua

Antigua

Antigua , also known as Waladli, is an island in the West Indies, in the Leeward Islands in the Caribbean region, the main island of the country of Antigua and Barbuda. Antigua means "ancient" in Spanish and was named by Christopher Columbus after an icon in Seville Cathedral, Santa Maria de la...

for any possible attack by Bompart, before the bulk of the force sailed for home in late July.

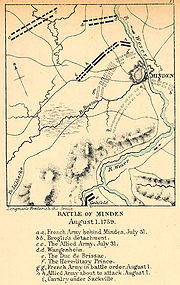

Battle of Minden

Since early 1758 the British had contributed increasingly large number of troops to serve in Germany. Pitt had reversed his previous hostility to British intervention on the continent, as he realised that the theatre could be used to tie down numerous French troops and resources which might otherwise be sent to fight in the colonies. Brunswick's army had enjoyed enormous success since winter 1757, crossing the Rhine several times, winning the Battle of KrefeldBattle of Krefeld

The Battle of Krefeld was a battle fought on 23 June 1758 between a Prussian-Hanoverian army and a French army during the Seven Years' War.-Background:...

and capturing Bremen

Bremen

The City Municipality of Bremen is a Hanseatic city in northwestern Germany. A commercial and industrial city with a major port on the river Weser, Bremen is part of the Bremen-Oldenburg metropolitan area . Bremen is the second most populous city in North Germany and tenth in Germany.Bremen is...

without a shot being fired. In recognition of his services Parliament voted him £2,000 a year for life. By April 1759 Brunswick had an army of around 72,000 facing two French armies with a combined strength of 100,000. The French had occupied Frankfurt

Frankfurt

Frankfurt am Main , commonly known simply as Frankfurt, is the largest city in the German state of Hesse and the fifth-largest city in Germany, with a 2010 population of 688,249. The urban area had an estimated population of 2,300,000 in 2010...

and were using it as their base for operations, which Brunswick now attempted to assault. On 13 April Brunswick lost the Battle of Bergen

Battle of Bergen (1759)

The Battle of Bergen on 13 April 1759 saw the French army under de Broglie withstand an allied British, Hanoverian, Hessian, Brunswick army under Prince Ferdinand of Brunswick near Frankfurt-am-Main during the Seven Years' War.-Background:...

to a superior French force and was forced to retreat.

Minden

Minden is a town of about 83,000 inhabitants in the north-east of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. The town extends along both sides of the river Weser. It is the capital of the Kreis of Minden-Lübbecke, which is part of the region of Detmold. Minden is the historic political centre of the...

which could potentially be used to stage an invasion of Hanover. Brunswick was pressured into action by this threat, the French command was also eager to end the campaign with a swift victory to free up troops which would allow them to take part in the proposed Invasion of Britain. On the night of the 31 July, both commanders simultaneously decided to attack the other outside Minden. The French forces reacted hesitantly when faced with Germans in front of them as dawn broke, allowing the Allies to seize the initiative and counter-attack. However, one column of British troops advanced too quickly and soon found itself attacked on all sides by a mixture of cavalry, artillery and infantry which vastly outnumbered them. The British managed to hold them off, sustaining casualties of a third. When they were reinforced with other troops, the Allies broke through the French lines and forced them to retreat. The British cavalry under Sackville were ordered to advance, but he refused apparently in indignation at his treatment by Brunswick, though this was at the time popularly attributed to cowardice on his part. In the confusion, the French were allowed to escape the battlefield and avoid total disaster.

Despite the widespread praise for the conduct of the British troops, their commander Sackville received condemnation for his alleged cowardice and was forced to return home in disgrace. He was replaced by Marquess of Granby

John Manners, Marquess of Granby

General John Manners, Marquess of Granby PC, , British soldier, was the eldest son of the 3rd Duke of Rutland. As he did not outlive his father, he was known by his father's subsidiary title, Marquess of Granby...

. The victory proved crucial, as Frederick had lost to the Russians at Kunersdorf. Had Brunswick been defeated at Minden Hanover would almost certainly have been invaded and the total defeat of Prussia would have been imminent. In the wake of the victory, the Allies advanced pushing the French backwards and relieving the pressure on the Prussians.

Failed invasion

The central plank of France's war against Britain in 1759 was a plan to invade Britain, authored by the French chief minister Duc ChoiseulÉtienne François, duc de Choiseul

Étienne-François, comte de Stainville, duc de Choiseul was a French military officer, diplomat and statesman. Between 1758 and 1761, and 1766 and 1770, he was Foreign Minister of France and had a strong influence on France's global strategy throughout the period...

. It was subject to several changes, but the core was that more than 50,000 French troops would cross the English channel

English Channel

The English Channel , often referred to simply as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates southern England from northern France, and joins the North Sea to the Atlantic. It is about long and varies in width from at its widest to in the Strait of Dover...

from Le Havre

Le Havre

Le Havre is a city in the Seine-Maritime department of the Haute-Normandie region in France. It is situated in north-western France, on the right bank of the mouth of the river Seine on the English Channel. Le Havre is the most populous commune in the Haute-Normandie region, although the total...

in flat-bottomed boats and land at Portsmouth

Portsmouth

Portsmouth is the second largest city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire on the south coast of England. Portsmouth is notable for being the United Kingdom's only island city; it is located mainly on Portsea Island...

on the British coast. Aided by a Jacobite rebellion - they would then advance on London and force a peace agreement on the British, extracting various concessions and knocking them out of the war. The British became aware through their agents of the scheme and drew up a plan to mobilise their forces in case of the invasion. In an effort to set back the invasion, a British raid was launched against Le Havre

Raid on Le Havre

The Raid on Le Havre was a two-day naval bombardment of the French port of Le Havre early in July 1759 by Royal Navy forces under George Rodney during the Seven Years' War, which succeeded in its aim of destroying many of the invasion barges being gathered there for the planned French invasion of...

which destroyed numerous flat-boats and supplies. In spite of this, the plans continued to progress and by Autumn the French were poised to launch their invasion.

Following naval defeats at Quiberon and Lagos, and with news of the Allied victory at Minden the French began to have second thoughts about their plan, and in late Autumn cancelled it. The French did not have the clear sea they hoped for the crossing, nor could they now spare the number of troops on the continent. There were also seen as a number of flaws in the plan including the fact that claims of the number of Jacobite supporters were considered wildly optimistic.

The campaign was considered a last throw of the dice for the Jacobites

Jacobitism

Jacobitism was the political movement in Britain dedicated to the restoration of the Stuart kings to the thrones of England, Scotland, later the Kingdom of Great Britain, and the Kingdom of Ireland...

to have any realistic hope of reclaiming the British throne. After the campaign the French soon abandoned the Stuarts entirely, withdrawing their support, and forcing them to take up a new home in Rome

Rome

Rome is the capital of Italy and the country's largest and most populated city and comune, with over 2.7 million residents in . The city is located in the central-western portion of the Italian Peninsula, on the Tiber River within the Lazio region of Italy.Rome's history spans two and a half...

. Many of the Highland

Scottish Highlands

The Highlands is an historic region of Scotland. The area is sometimes referred to as the "Scottish Highlands". It was culturally distinguishable from the Lowlands from the later Middle Ages into the modern period, when Lowland Scots replaced Scottish Gaelic throughout most of the Lowlands...

communities that had strongly supported the Jacobites in 1715 and 1745 now had regiments serving in the British army, where they played a key role in Britain's success that year.

Naval supremacy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

had expanded to a new height of 71,000 personnel and 275 ships in commission, with another 82 under ordinance. During the war the British had instituted a new system of blockade

Blockade

A blockade is an effort to cut off food, supplies, war material or communications from a particular area by force, either in part or totally. A blockade should not be confused with an embargo or sanctions, which are legal barriers to trade, and is distinct from a siege in that a blockade is usually...

, by which they penned in the main French fleets at anchor in Brest

Brest, France

Brest is a city in the Finistère department in Brittany in northwestern France. Located in a sheltered position not far from the western tip of the Breton peninsula, and the western extremity of metropolitan France, Brest is an important harbour and the second French military port after Toulon...

and Toulon

Toulon

Toulon is a town in southern France and a large military harbor on the Mediterranean coast, with a major French naval base. Located in the Provence-Alpes-Côte-d'Azur region, Toulon is the capital of the Var department in the former province of Provence....

. The British were able to keep an almost constant force poised outside French harbours. The French inability to counter this had led to a collapse in morale amongst French seamen and the wider population.

The French government had devised a plan that would allow them to launch their invasion. It required a junction of the two French fleets in the English Channel

English Channel

The English Channel , often referred to simply as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates southern England from northern France, and joins the North Sea to the Atlantic. It is about long and varies in width from at its widest to in the Strait of Dover...