Battle of the Monongahela

Encyclopedia

The Battle of the Monongahela, also known as the Battle of the Wilderness, took place on 9 July 1755, at the beginning of the French and Indian War

, at Braddock's Field

in what is now Braddock, Pennsylvania

, 10 miles (16.1 km) east of Pittsburgh. A British force under General Edward Braddock

, moving to take Fort Duquesne

, was defeated by a force of French

and Canadian troops, with its Native American

allies.

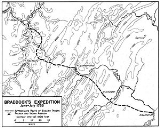

The defeat marked the end of the Braddock expedition

, by which the British had hoped to capture Fort Duquesne and gain control of the strategic Ohio Country

. Braddock was mortally wounded in the battle and died during the retreat. The remainder of the column retreated southwards and the fort remained in French hands until its capture in 1758.

in the new position of Commander-in-Chief

, bringing with him two regiments (the 44th and 48th) of troops from Ireland

. He added to this by recruiting local troops in British America

, swelling his forces to roughly 2,200 by the time he set out from Fort Cumberland

, Maryland

on 29 May. He was accompanied by Virginia Colonel George Washington

, who had led the previous year's expedition to the area.

Braddock's expedition was part of a four-pronged attack on the French in North America. Braddock's orders were to launch an attack into the Ohio Country

, disputed by Britain and France. Control of the area was dominated by Fort Duquesne on the forks of the Ohio River

. Once it was in his possession, he was to proceed on to Fort Niagara

, establishing British control over the Ohio territory.

He soon encountered a number of difficulties. He was scornful of the need to recruit local Native Americans

as scouts, and left with only eight Mingo

guides. He found that the road he was trying to use was slow, and needed constant widening to move artillery and supply wagons along it. Frustrated, he split his force in two, leading a flying column ahead, with a slower force following with the cannon and wagons.

The flying column of 1,300 crossed the Monongahela River on 9 July, within 10 miles (16.1 km) of their target, Fort Duquesne. Despite being very tired after weeks of crossing extremely hard terrain, many of the British and Americans anticipated a relatively easy victory—or even for the French to abandon the fort upon their approach.

Fort Duquesne had been very lightly defended, but had recently received significant reinforcements. Claude-Pierre Pecaudy de Contrecoeur, the Canadian commander of the fort, had around 1,600 French troupes de la Marine

, Canadian militiamen and Native American allies. Concerned by the approach of the British, he dispatched Captain Daniel Liénard de Beaujeu

with around 800 troops, (108 Troupes de la Marine, 146 Canadian militia, and 600 Indians), to check their advance.

. Seeing the enemy in the trees, he ordered his men to open fire. Despite firing at very long range for a smooth-bored musket, their opening volleys succeeded in killing Captain Beaujeu.

Unconcerned by the death of Beaujeu, the Indian warriors took up positions to attack. They were fighting on an Indian hunting ground which favored their tactics, with numerous trees and shrubbery separated by wide open spaces. Although roughly a hundred of the Canadians fled back to the fort, Captain Dumas rallied the rest of the French troops. The Indian tribes allied with the French, the Ottawas and Potawatomis, used psychological warfare

against the British forces. After the Indians killed British soldiers, they would nail their scalps to surrounding trees. During the battle, Indians made a terrifying "whoop" sound that caused fear and panic to spread in the British infantry.

As they came under heavy fire, Gage's advance guard began taking casualties and withdrew. In the narrow confines of the road, they collided with the main body of Braddock's force, which had advanced rapidly when the shots were heard. Despite comfortably outnumbering their attackers, the British were immediately on the defensive. Most of the regulars were unused to fighting in woods, and were terrified by the deadly musket fire. Confusion reigned, and several British platoons fired at each other. The entire column dissolved in disorder as the Canadian militiamen and Indians enveloped them and continued to snipe at the British flanks from the woods on the sides of the road. At this time, the French regulars began advancing along the road and began to push the British back. General Braddock rode forward to try to rally his men, who had lost all sense of unit cohesion.

Following Braddock's lead, the officers tried to reform units into regular order within the confines of the road. This effort was mostly in vain, and simply provided targets for their concealed enemy. Cannon were used, but due to the confines of the forest road, they were ineffective. Braddock had several horses shot under him, yet retained his composure, providing the only sign of order to the frightened British soldiers. Many of the Americans, lacking the training of British regulars to stand their ground, fled and sheltered behind trees, where they were mistaken for enemy fighters by the redcoats, who fired upon them. The rearguard, made up of Virginians, managed to fight effectively from the trees—something they had learned in previous years of fighting Indians.

Following Braddock's lead, the officers tried to reform units into regular order within the confines of the road. This effort was mostly in vain, and simply provided targets for their concealed enemy. Cannon were used, but due to the confines of the forest road, they were ineffective. Braddock had several horses shot under him, yet retained his composure, providing the only sign of order to the frightened British soldiers. Many of the Americans, lacking the training of British regulars to stand their ground, fled and sheltered behind trees, where they were mistaken for enemy fighters by the redcoats, who fired upon them. The rearguard, made up of Virginians, managed to fight effectively from the trees—something they had learned in previous years of fighting Indians.

Despite the unfavorable conditions, the British began to stand firm and blast volleys at the enemy. Braddock believed that the enemy would eventually give way in the face of the discipline displayed by the English-led troops. Despite lacking officers to command them, the often makeshift platoons continued to hold their crude ranks.

Finally, after three hours of intense combat, Braddock was shot in the lung by Thomas Fausett and effective resistance collapsed. He fell from his horse, badly wounded, and was carried back to safety by his men. As a result of Braddock's wounding, and without an order being given, the British began to withdraw. They did so largely with order, until they reached the Monongahela River, when they were set upon by the Indian warriors. The Indians attacked with hatchets and scalping knives, after which panic spread among the British troops and they began to break ranks and run, believing they were about to be massacred.

Colonel Washington, although he had no official position in the chain of command, was able to impose and maintain some order, and formed a rear guard, which allowed the remnants of the force to disengage. By sunset, the surviving British forces were fleeing back down the road they had built, carrying their wounded. Behind them on the road, bodies were piled high. The Indians did not pursue the fleeing redcoats, but instead set about scalping and looting the corpses of the wounded and dead, and drinking two hundred gallons of captured rum.

, only 4 returned with the British; about half were taken as captives. The French and Canadians reported very few casualties.

Braddock died of his wounds on July 13, four days after the battle, and was buried on the road near Fort Necessity.

Colonel Thomas Dunbar, with the reserves and rear supply units, took command when the survivors reached his position. Realizing there was no further likelihood of his force proceeding to capture Fort Duquesne, he decided to retreat. He ordered the destruction of supplies and cannon before withdrawing, burning about 150 wagons on the spot. His forces retreated back toward Philadelphia. The French did not pursue, realizing that they did not have sufficient resources for an organized pursuit.

Colonel Thomas Dunbar, with the reserves and rear supply units, took command when the survivors reached his position. Realizing there was no further likelihood of his force proceeding to capture Fort Duquesne, he decided to retreat. He ordered the destruction of supplies and cannon before withdrawing, burning about 150 wagons on the spot. His forces retreated back toward Philadelphia. The French did not pursue, realizing that they did not have sufficient resources for an organized pursuit.

, which many had believed contained overwhelming force, to seize the Ohio Country. It awakened many in London to the sheer scale of forces that would be needed to defeat the French and their Indian allies in North America

.

The inability of the redcoats to use skirmishers, and the vulnerability this caused for the main force, had a profound effect on British military thinking. Although Braddock had posted a company of flankers on each side, these troops were untrained to do anything but stand in line and fire platoon volleys, which were unsuited to such conditions. Learning from their mistakes the British made much better use of skirmishers, often equipped with rifles, who could protect the main body of troops from such devastating fire, both later in the French and Indian War

and in the American War of Independence.

Because of the speed with which the French and Indians launched their attack and enveloped the British column, the battle is often erroneously reported as an ambush by many who took part. In fact, the French had been unprepared for their contact with the British, whom they had blundered into. The speed of their response allowed them to quickly gain the upper hand, and brought about their victory.

The French remained dominant in the Ohio Country

for the next three years, and persuaded many previously neutral Indian tribes to enter the war on their side. The French were eventually forced to abandon Fort Duquesne in 1758 by the approach of the Forbes Expedition

.

.

Because of the important role the battle played in the career of George Washington, it is often featured in portrayals of him.

French and Indian War

The French and Indian War is the common American name for the war between Great Britain and France in North America from 1754 to 1763. In 1756, the war erupted into the world-wide conflict known as the Seven Years' War and thus came to be regarded as the North American theater of that war...

, at Braddock's Field

Braddock's Field

Braddock's Field is a historic battlefield on the banks of the Monongahela River, at Braddock, Pennsylvania, near the junction of Turtle Creek , about nine miles southeast of the "Forks of the Ohio" in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania...

in what is now Braddock, Pennsylvania

Braddock, Pennsylvania

Braddock is a borough located in the eastern suburbs of Pittsburgh in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, 10 miles upstream from the mouth of the Monongahela River. The population was 2,159 at the 2010 census...

, 10 miles (16.1 km) east of Pittsburgh. A British force under General Edward Braddock

Edward Braddock

General Edward Braddock was a British soldier and commander-in-chief for the 13 colonies during the actions at the start of the French and Indian War...

, moving to take Fort Duquesne

Fort Duquesne

Fort Duquesne was a fort established by the French in 1754, at the junction of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers in what is now downtown Pittsburgh in the state of Pennsylvania....

, was defeated by a force of French

Early Modern France

Kingdom of France is the early modern period of French history from the end of the 15th century to the end of the 18th century...

and Canadian troops, with its Native American

Native Americans in the United States

Native Americans in the United States are the indigenous peoples in North America within the boundaries of the present-day continental United States, parts of Alaska, and the island state of Hawaii. They are composed of numerous, distinct tribes, states, and ethnic groups, many of which survive as...

allies.

The defeat marked the end of the Braddock expedition

Braddock expedition

The Braddock expedition, also called Braddock's campaign or, more commonly, Braddock's Defeat, was a failed British military expedition which attempted to capture the French Fort Duquesne in the summer of 1755 during the French and Indian War. It was defeated at the Battle of the Monongahela on...

, by which the British had hoped to capture Fort Duquesne and gain control of the strategic Ohio Country

Ohio Country

The Ohio Country was the name used in the 18th century for the regions of North America west of the Appalachian Mountains and in the region of the upper Ohio River south of Lake Erie...

. Braddock was mortally wounded in the battle and died during the retreat. The remainder of the column retreated southwards and the fort remained in French hands until its capture in 1758.

Background

Braddock had been dispatched to North AmericaNorth America

North America is a continent wholly within the Northern Hemisphere and almost wholly within the Western Hemisphere. It is also considered a northern subcontinent of the Americas...

in the new position of Commander-in-Chief

Commander-in-Chief, North America

The office of Commander-in-Chief, North America was a military position of the British Army. Established in 1755 in the early years of the Seven Years' War, holders of the post were generally responsible for land-based military personnel and activities in and around those parts of North America...

, bringing with him two regiments (the 44th and 48th) of troops from Ireland

Kingdom of Ireland

The Kingdom of Ireland refers to the country of Ireland in the period between the proclamation of Henry VIII as King of Ireland by the Crown of Ireland Act 1542 and the Act of Union in 1800. It replaced the Lordship of Ireland, which had been created in 1171...

. He added to this by recruiting local troops in British America

British America

For American people of British descent, see British American.British America is the anachronistic term used to refer to the territories under the control of the Crown or Parliament in present day North America , Central America, the Caribbean, and Guyana...

, swelling his forces to roughly 2,200 by the time he set out from Fort Cumberland

Fort Cumberland (Maryland)

thumb|380px|Fort Cumberland, 1755 Fort Cumberland was an 18th century frontier fort at the current site of Cumberland, Maryland, USA...

, Maryland

Province of Maryland

The Province of Maryland was an English and later British colony in North America that existed from 1632 until 1776, when it joined the other twelve of the Thirteen Colonies in rebellion against Great Britain and became the U.S...

on 29 May. He was accompanied by Virginia Colonel George Washington

George Washington

George Washington was the dominant military and political leader of the new United States of America from 1775 to 1799. He led the American victory over Great Britain in the American Revolutionary War as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army from 1775 to 1783, and presided over the writing of...

, who had led the previous year's expedition to the area.

Braddock's expedition was part of a four-pronged attack on the French in North America. Braddock's orders were to launch an attack into the Ohio Country

Ohio Country

The Ohio Country was the name used in the 18th century for the regions of North America west of the Appalachian Mountains and in the region of the upper Ohio River south of Lake Erie...

, disputed by Britain and France. Control of the area was dominated by Fort Duquesne on the forks of the Ohio River

Ohio River

The Ohio River is the largest tributary, by volume, of the Mississippi River. At the confluence, the Ohio is even bigger than the Mississippi and, thus, is hydrologically the main stream of the whole river system, including the Allegheny River further upstream...

. Once it was in his possession, he was to proceed on to Fort Niagara

Fort Niagara

Fort Niagara is a fortification originally built to protect the interests of New France in North America. It is located near Youngstown, New York, on the eastern bank of the Niagara River at its mouth, on Lake Ontario.-Origin:...

, establishing British control over the Ohio territory.

He soon encountered a number of difficulties. He was scornful of the need to recruit local Native Americans

Native Americans in the United States

Native Americans in the United States are the indigenous peoples in North America within the boundaries of the present-day continental United States, parts of Alaska, and the island state of Hawaii. They are composed of numerous, distinct tribes, states, and ethnic groups, many of which survive as...

as scouts, and left with only eight Mingo

Mingo

The Mingo are an Iroquoian group of Native Americans made up of peoples who migrated west to the Ohio Country in the mid-eighteenth century. Anglo-Americans called these migrants mingos, a corruption of mingwe, an Eastern Algonquian name for Iroquoian-language groups in general. Mingos have also...

guides. He found that the road he was trying to use was slow, and needed constant widening to move artillery and supply wagons along it. Frustrated, he split his force in two, leading a flying column ahead, with a slower force following with the cannon and wagons.

The flying column of 1,300 crossed the Monongahela River on 9 July, within 10 miles (16.1 km) of their target, Fort Duquesne. Despite being very tired after weeks of crossing extremely hard terrain, many of the British and Americans anticipated a relatively easy victory—or even for the French to abandon the fort upon their approach.

Fort Duquesne had been very lightly defended, but had recently received significant reinforcements. Claude-Pierre Pecaudy de Contrecoeur, the Canadian commander of the fort, had around 1,600 French troupes de la Marine

Troupes de la marine

See also Troupes de Marine for later history of same Corps.The Troupes de la Marine , also known as independent companies of the navy and colonial regulars, were under the authority of the French Minister of Marine, who was also responsible for the French navy, overseas trade, and French...

, Canadian militiamen and Native American allies. Concerned by the approach of the British, he dispatched Captain Daniel Liénard de Beaujeu

Daniel Liénard de Beaujeu

Daniel Hyacinthe Liénard de Beaujeu was a French officer during the Seven Years War. He participated in the Battle of Grand Pre . He also organized the force that attacked General Edward Braddock's army after it forded the Monongahela River. The event was later dubbed the Battle of the Monongahela...

with around 800 troops, (108 Troupes de la Marine, 146 Canadian militia, and 600 Indians), to check their advance.

Battle

The French and Indians arrived too late to set an ambush, as they had been delayed, and the British had made surprisingly speedy progress. They ran into the British advance guard, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Thomas GageThomas Gage

Thomas Gage was a British general, best known for his many years of service in North America, including his role as military commander in the early days of the American War of Independence....

. Seeing the enemy in the trees, he ordered his men to open fire. Despite firing at very long range for a smooth-bored musket, their opening volleys succeeded in killing Captain Beaujeu.

Unconcerned by the death of Beaujeu, the Indian warriors took up positions to attack. They were fighting on an Indian hunting ground which favored their tactics, with numerous trees and shrubbery separated by wide open spaces. Although roughly a hundred of the Canadians fled back to the fort, Captain Dumas rallied the rest of the French troops. The Indian tribes allied with the French, the Ottawas and Potawatomis, used psychological warfare

Psychological warfare

Psychological warfare , or the basic aspects of modern psychological operations , have been known by many other names or terms, including Psy Ops, Political Warfare, “Hearts and Minds,” and Propaganda...

against the British forces. After the Indians killed British soldiers, they would nail their scalps to surrounding trees. During the battle, Indians made a terrifying "whoop" sound that caused fear and panic to spread in the British infantry.

As they came under heavy fire, Gage's advance guard began taking casualties and withdrew. In the narrow confines of the road, they collided with the main body of Braddock's force, which had advanced rapidly when the shots were heard. Despite comfortably outnumbering their attackers, the British were immediately on the defensive. Most of the regulars were unused to fighting in woods, and were terrified by the deadly musket fire. Confusion reigned, and several British platoons fired at each other. The entire column dissolved in disorder as the Canadian militiamen and Indians enveloped them and continued to snipe at the British flanks from the woods on the sides of the road. At this time, the French regulars began advancing along the road and began to push the British back. General Braddock rode forward to try to rally his men, who had lost all sense of unit cohesion.

Despite the unfavorable conditions, the British began to stand firm and blast volleys at the enemy. Braddock believed that the enemy would eventually give way in the face of the discipline displayed by the English-led troops. Despite lacking officers to command them, the often makeshift platoons continued to hold their crude ranks.

Finally, after three hours of intense combat, Braddock was shot in the lung by Thomas Fausett and effective resistance collapsed. He fell from his horse, badly wounded, and was carried back to safety by his men. As a result of Braddock's wounding, and without an order being given, the British began to withdraw. They did so largely with order, until they reached the Monongahela River, when they were set upon by the Indian warriors. The Indians attacked with hatchets and scalping knives, after which panic spread among the British troops and they began to break ranks and run, believing they were about to be massacred.

Colonel Washington, although he had no official position in the chain of command, was able to impose and maintain some order, and formed a rear guard, which allowed the remnants of the force to disengage. By sunset, the surviving British forces were fleeing back down the road they had built, carrying their wounded. Behind them on the road, bodies were piled high. The Indians did not pursue the fleeing redcoats, but instead set about scalping and looting the corpses of the wounded and dead, and drinking two hundred gallons of captured rum.

Aftermath

Of the approximately 1,300 men Braddock led into battle, 456 were killed outright and 422 were wounded. Commissioned officers were prime targets and suffered greatly: out of 86 officers, 26 were killed and 37 wounded. Of the 50 or so women that accompanied the British column as maids and cooksCook (servant)

A cook is a household staff member responsible for food preparation. The term can refer to the head of kitchen staff in a great house or to the cook-housekeeper, a far less prestigious position involving more physical labour....

, only 4 returned with the British; about half were taken as captives. The French and Canadians reported very few casualties.

Braddock died of his wounds on July 13, four days after the battle, and was buried on the road near Fort Necessity.

Legacy

The battle was a devastating defeat, and has been characterized as one of the most disastrous in British colonial history. It marked the end of the Braddock expeditionBraddock expedition

The Braddock expedition, also called Braddock's campaign or, more commonly, Braddock's Defeat, was a failed British military expedition which attempted to capture the French Fort Duquesne in the summer of 1755 during the French and Indian War. It was defeated at the Battle of the Monongahela on...

, which many had believed contained overwhelming force, to seize the Ohio Country. It awakened many in London to the sheer scale of forces that would be needed to defeat the French and their Indian allies in North America

North America

North America is a continent wholly within the Northern Hemisphere and almost wholly within the Western Hemisphere. It is also considered a northern subcontinent of the Americas...

.

The inability of the redcoats to use skirmishers, and the vulnerability this caused for the main force, had a profound effect on British military thinking. Although Braddock had posted a company of flankers on each side, these troops were untrained to do anything but stand in line and fire platoon volleys, which were unsuited to such conditions. Learning from their mistakes the British made much better use of skirmishers, often equipped with rifles, who could protect the main body of troops from such devastating fire, both later in the French and Indian War

French and Indian War

The French and Indian War is the common American name for the war between Great Britain and France in North America from 1754 to 1763. In 1756, the war erupted into the world-wide conflict known as the Seven Years' War and thus came to be regarded as the North American theater of that war...

and in the American War of Independence.

Because of the speed with which the French and Indians launched their attack and enveloped the British column, the battle is often erroneously reported as an ambush by many who took part. In fact, the French had been unprepared for their contact with the British, whom they had blundered into. The speed of their response allowed them to quickly gain the upper hand, and brought about their victory.

The French remained dominant in the Ohio Country

Ohio Country

The Ohio Country was the name used in the 18th century for the regions of North America west of the Appalachian Mountains and in the region of the upper Ohio River south of Lake Erie...

for the next three years, and persuaded many previously neutral Indian tribes to enter the war on their side. The French were eventually forced to abandon Fort Duquesne in 1758 by the approach of the Forbes Expedition

Forbes Expedition

The Forbes Expedition was a British military expedition led by Brigadier-General John Forbes in 1758, during the French and Indian War. Its objective was the capture of Fort Duquesne, a French fort constructed at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers in 1754.The expedition...

.

Popular culture

The battle is portrayed in the novel Savage Wilderness by Harold CoyleHarold Coyle

For the Irish architect, see Harold Edgar Coyle.Harold Coyle is an American author of historical, speculative fiction and war novels including Team Yankee, a New York Times best-seller. He graduated from the Virginia Military Institute in 1974 and spent seventeen years on active duty with the U.S...

.

Because of the important role the battle played in the career of George Washington, it is often featured in portrayals of him.