Anarchism in the United States

Encyclopedia

Anarchism in the United States spans a wide range of anarchist philosophy

, from individualist anarchism

to anarchist communism

and other less known forms. America has two main traditions, native and immigrant, with the native tradition being strongly individualist and the immigrant tradition being collectivist and anarcho-communist. Influential American anarchists include Josiah Warren

, Henry David Thoreau

, Lysander Spooner

, Lucy Parsons

, Murray Rothbard

, Benjamin Tucker

, Voltairine de Cleyre

, Johann Most

, Luigi Galleani

, Emma Goldman

, Alexander Berkman

, social ecologist

Murray Bookchin

, Paul Goodman

, linguist Noam Chomsky

and John Zerzan

.

The first American anarchist publication was The Peaceful Revolutionist, edited by Josiah Warren

, whose earliest experiments and writings predate Pierre Proudhon.

, Aztec

, Inca, and Maya

cultures were clearly statist.

More recently, many participants in the American Indian Movement

have described themselves as anarchist and cooperation between anarchist and Indigenous groups has been a key feature of movements such as the Minnehaha Free State in Minneapolis, Minnesota

- (which is built on an Ojibwa

Reservation

) - and at Big Mountain.

Outside of indigenous communities, green anarchists

have been the most vocal in declaring solidarity with ongoing indigenous struggles, but social anarchists

in general are supportive as well.

controversy in Puritan

New England

. Some consider the first anarchist

in America to be Anne Hutchinson

(1591–1643), a proto-feminist

individualist.

The U.S., with its tradition of radical individualism

, which is "enshrined in the Declaration of Independence

", was a congenial environment for individualist anarchism. Josiah Warren cited the Declaration of Independence and Benjamin Tucker said that "Anarchists are simply unterrified Jeffersonian Democrats." In 1833 Josiah Warren began publishing "the first explicitly anarchist newspaper in the United States", called "The Peaceful Revolutionist." According to Rudolph Rocker, the American individualist anarchists were "influenced in their intellectual development much more by the principles expressed in the Declaration of Independence than by those of any of the representatives of libertarian socialism in Europe. They were all 'one hundred percent American' by descent, and almost all of them were born in the New England states. As a matter of fact, this school of thought had found literary expression in America before any modern radical movements were even thought of in Europe."

Beginning in 1881, Benjamin Tucker began publishing "Liberty," which was a forum to propagate individualist anarchist ideas. By that time, anarcho-communism and propaganda by the deed was arriving in America, "both of which Tucker detested." Tucker criticized the immigrant anarcho-communist Alexander Berkman's attempt to assassinate Henry Clay Frick, saying "The hope of humanity lies in the avoidance of that revolution by force which the Berkmans are trying to precipitate. No pity for Frick, no praise for Berkman such is the attitude of Liberty in the present crisis."

By the twentieth century, individualist anarchism in America was in decline. It was later revived by Murray Rothbard and the anarcho-capitalists in the mid-twentieth century.

According to Carlotta Anderson:

has roots tracing back to well before the American Civil War

. Early leaders included Albert Parsons

, his wife Lucy Parsons

, along with many immigrants who brought their radicalism with them such as Johann Most

, Emma Goldman

, and Big Bill Haywood, and many others. Their influence on the early American labor movement was dramatic, with the execution of Albert Parsons and the other Haymarket Martyrs providing a key rallying cry for the early American labor movement and spurring the creation of radical unions throughout the country. The largest - the Industrial Workers of the World

, was founded in 1905. Swedish-American musician Joe Hill

is also one of the most famous social anarchist protest singers to have ever lived.

Social anarchism includes anarcho-communism, anarcho-syndicalism

, libertarian socialism

, and other forms of anarchism that take the creation of social goods as their first priority.

Many anarchist communists

, such as the publishers of Barricada magazine in the United States and foreign immigrants to the US such as Luigi Galleani

and Johann Most

have been insurrectionary anarchists.

to Anarcho-Communists who sought an individualized society of decentralized communes." Anarchism started making a comeback in the United States in the early 1960s, primarily through the influence of the Beat

artists. Later in the 1960s, activists such as Abbie Hoffman

and the Diggers

identified with anarchism and were notable for the spectacular ways they put anarchist ideas into practice. In the late 60s, Murray Rothbard

and Karl Hess

began to call themselves anarchists and published Left and Right: A Journal of Libertarian Thought. In 1969, The Match!, which bills itself as a "Journal of Ethical Anarchism" began publication by anarchist without adjectives Fred Woodworth

and has published continuously since then.

In the 1970s, anarchist ideas caught on in the anti-nuclear, feminist, and environmental movements. Murray Bookchin

was a widely read anarchist thinker whose books on the environment were influential on the environmental movement. Anarchist tactics such as the affinity group were adopted by women involved in the radical feminist movement.

Anarchists became more visible in the 1980s, as a result of publishing, protests and conventions. In 1980, the First International Symposium on Anarchism was held in Portland, Oregon. In 1986, the Haymarket Remembered conference was held in Chicago, to observe the centennial of the infamous Haymarket Riot. This conference was followed by annual, continental conventions in Minneapolis (1987), Toronto (1988), and San Francisco (1989).

Recently there has been a resurgence in anarchist ideals in the United States. In the 1990s, a group of anarchists formed the Love and Rage Network, which was one of several new groups and projects formed in the U.S. during the decade. American anarchists increasingly became noticeable at protests, especially through a tactic known as the Black bloc

. U.S. anarchists became more prominent in 1999 as a result of the anti-WTO protests

in Seattle.

In the wake of hurricane Katrina, anarchist activists have been visible as founding members of the Common Ground Collective

.

called "New Harmony

," but was disappointed in its failure. He stressed the need for individual sovereignty. In True Civilization Warren equates "Sovereignty of the Individual" with the Declaration of Independence

's assertion of the inalienable rights. He claims that every person has an "instinct" for individual sovereignty, making individual rights inalienable and inviolate.

Basing his economics on the labor theory of value, Warren's economic principle was "cost the limit of price

," with "cost" referring to the amount of labor incurred in producing a commodity and bringing it to market. He opposed what he called "value the limit of price," where prices paid are determined simply by subjective valuation irrespective of labor costs, as being inequitable or unfair. In 1827, Warren put his theories into practice by starting a business called the Cincinnati Time Store

where the trade of goods was facilitated by private currency denominated in hours of labor. Warren was a strong supporter of the right of individuals to retain the product of their labor as private possessions. This position was shared by fellow anarchist Stephen Pearl Andrews

.

author, development critic

, naturalist, transcendentalist

, pacifist

, tax resister

and philosopher who is famous for Walden

, on simple living

amongst nature, and Civil Disobedience

. In 1849, Henry David Thoreau wrote "I heartily accept the motto, 'That government is best which governs least'; and I should like to see it acted up to more rapidly and systematically. Carried out, it finally amounts to this, which also I believe– 'That government is best which governs not at all'; and when men are prepared for it, that will be the kind of government which we will have." Although Thoreau never labeled himself an "anarchist," he has been regarded to be an individualist anarchist

.

(1819–1878) was an author, soldier, currency reformer, individualist anarchist, Unitarian minister and philosopher, active in transcendentalist

circles. In works such as Equality (1849) and Mutual Banking (1850) he synthesized the work of French socialists such as P.-J. Proudhon

and Pierre Leroux

with that of American currency reformers such as William Beck and Edward Kellogg. The result was a unique form of Christian mutualism

, which attempted to harmonize elements of capitalism

, communism

and socialism

. Greene was later involved with the New England Labor Reform League, and with the anti-death penalty work of The Prisoner's Friend. He was a regular contributor to Ezra Heywood's The Word until his death. William B. Greene's mutualistic

economic philosophy resembles the economic philosophy of the earlier French anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

and the economic system of the land banks that existed in the United States during the colonial period.

Albert Richard Parsons (June 20, 1848 - November 11, 1887) was an anarchist labor activist, who was convicted of conspiracy and hanged following a bomb attack on police at the Haymarket Riot. It was in Chicago that Parsons developed his anarchist ideas, became a labor activist, and eventually became a founding member of the International Working People's Association

Albert Richard Parsons (June 20, 1848 - November 11, 1887) was an anarchist labor activist, who was convicted of conspiracy and hanged following a bomb attack on police at the Haymarket Riot. It was in Chicago that Parsons developed his anarchist ideas, became a labor activist, and eventually became a founding member of the International Working People's Association

(IWPA). When he first came to Chicago, he found a job as a writer for the Times. Later in 1877, as a result of his becoming an outspoken supporter of worker's rights, he lost his position at the Times and was blacklisted by the industry altogether. Police Superintendent Michael Hickey told Parsons to leave Chicago during this time because his life was in danger. He then became devoted completely to his new anarchist ideas in favor of workers' rights and especially the eight-hour work day labor movement.

In addition to his involvement in the IWPA, Parsons was also involved with the Knights of Labor

during its embryonic period. Parsons joined the Knights of Labor, known then as "The Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor," on July 4, 1876. At the time Parsons joined, the Knights of Labor was just a small fraternal organization with elaborate rituals, most of them copied from the Masons.

Lucy Parsons

(1853-March 7, 1942), the widow of Albert Parsons, was a radical

American

labor organizer, anarchist communist, and is remembered as a powerful orator. A founder of the Industrial Workers of the World

in 1905, Parsons was described by the Chicago Police Department as "more dangerous than a thousand rioters" in the 1920s, Lucy Parsons and her husband had become highly effective anarchist organizers primarily involved in the labor movement in the late 19th century, but also participating in revolutionary

activism

on behalf of political prisoners, people of color, the homeless and women. She began writing for The Socialist and The Alarm, the journal of the International Working People's Association

(IWPA), which she and Parsons, among others, founded in 1883. In 1892 she briefly published Freedom: A Revolutionary Anarchist-Communist Monthly, and was often arrested for giving public speeches or distributing anarchist literature. While she continued championing the anarchist cause, she came into ideological conflict with some of her contemporaries, including Emma Goldman

, over her focus on class politics over gender and sexual struggles.

Stephen Pearl Andrews

Stephen Pearl Andrews

was an individualist anarchist and close associate of Josiah Warren. Andrews was formerly associated with the Fourierist

movement, but converted to radical individualism after becoming acquainted with the work of Warren. Like Warren, he held the principle of "individual sovereignty" as being of paramount importance.

Andrews said that when individuals act in their own self-interest, they incidentally contribute to the well-being of others. He maintained that it is a "mistake" to create a "state, church or public morality" that individuals must serve rather than pursuing their own happiness. In Love, Marriage and Divorce, and the Sovereignty of the Individual he says: "Give up...the search after the remedy for the evils of government in more government. The road lies just the other way--toward individualism and freedom from all government...Nature made individuals, not nations; and while nations exist at all, the liberties of the individual must perish."

Warren and Andrews established the individualist anarchist colony called "Modern Times

" on Long Island, NY. In tribute to Andrews, Benjamin Tucker said: "Anarchist especially will ever remember and honor him because he has left behind him the ablest English book ever written in defense of Anarchist principles" (Liberty, III, 2).

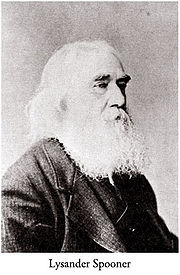

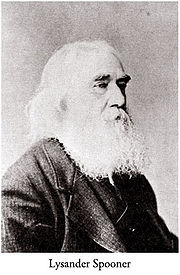

Lysander Spooner

Lysander Spooner

was an individualist anarchist who apparently worked with little association with the other individualists of the time, but came to approximately the same conclusions. In this time, his philosophy evolved from appearing to support a limited role for the state to opposing its existence altogether. Spooner was a staunch advocate of "natural law," maintaining that each individually has a "natural right" to be free to do as one wishes as long as he refrains from initiating coercion on others or their property.

With this natural law came the right of contract, which Spooner found of extreme importance. He holds that government cannot create law, as law already exists naturally; anything government does that is not in accordance with natural law (coercion) is illegal. Maintaining that government does not exist by contract of every individual it claims to govern, he came to believe that government itself is in violation of natural law, as it finances its activities through taxation of those who have not contracted with it. He rejected the popular idea that a majority, in the case of democracy, can consent on behalf of a minority; as a majority is bound to the same natural law against coercion to which individuals are bound: "...if the majority, however large, or the people enter into a contract of government called a constitution by which they...destroy or invade the natural rights of any person or persons whatsoever, this contract of government is unlawful and void" (The Unconstitutionality of Slavery). Spooner was also a strong advocate of entrepreneurship, advising others to start their own businesses to avoid sharing profits with an employer. He believed this could be made easier if the government de-regulated banking and money, which he believed would keep interest rates low except for high risk borrowers.

was another individualist anarchist influenced by Warren, who was an ardent slavery abolitionist and feminist. Heywood saw what he believed to be a disproportionate concentration of capital in the hands of a few as the result of a selective extension of government-backed privileges to certain individuals and organizations.

He said: "Government is a northeast wind, drifting property into a few aristocratic heaps, at the expense of altogether too much democratic bare ground. Through cunning legislation, ... privileged classes are allowed to steal largely according to law."

He believed that there should be no profit in rent of buildings. He did not oppose rent, but believed that if the building was fully paid for that it was improper to charge more than what is necessary for transfer costs, insurance, and repair of deterioration that occurs during the occupation by the tenant. He even asserted that it may be encumbent on the owner of the building to pay rent to the tenant if the tenant keeps his residency in such a condition that saved it from deterioration if it was otherwise unoccupied. Whereas, Warren, Andrews, and Greene supported ownership of unused land, Heywood believed that title to unused land was a great evil. Heywood's philosophy was instrumental in furthering individualist anarchist ideas through his extensive pamphleteering and reprinting of works of Warren and Greene.

, being influenced by Warren (whom he credits as being his "first source of light"), Greene, Heywood, Proudhon

's mutualism

, and Stirner's

egoism

, is probably the most famous of the American individualists. Tucker defined anarchism as "the doctrine that all the affairs of men should be managed by individuals or voluntary associations, and that the State should be abolished" (State Socialism and Anarchism).

Like the individualists he was influenced by, he rejected the notion of society being a thing that has rights, insisting that only individuals can have rights. And, like all anarchists, he opposed the governmental practice of democracy, as it allows a majority to decide for a minority

. Tucker's main focus, however, was on economics. He opposed profit, believing that it is only made possible by the "suppression or restriction of competition" by government and vast concentration of wealth.

He believed that restriction of competition was accomplished by the establishment of four "monopolies": the banking/money monopoly, the land monopoly, the tariff monopoly, and the patent and copyright monopoly - the most harmful of these, according to him, being the money monopoly. He believed that restrictions on who may enter the banking business and issue currency, as well as protection of unused land, were responsible for wealth being concentrated in the hands of a privileged few.

Johann Most (February 5, 1846 – March 17, 1906) was a German-American anarchist and orator, who in the late 19th century began to advocate the use of violence to achieve revolutionary political and social change. He is best known for popularizing the strategy of "propaganda of the deed

Johann Most (February 5, 1846 – March 17, 1906) was a German-American anarchist and orator, who in the late 19th century began to advocate the use of violence to achieve revolutionary political and social change. He is best known for popularizing the strategy of "propaganda of the deed

," which promoted direct action against individuals or institutions (including the use of violence) to force revolutionary change and inspire further action by others.

Encouraged by news of labor struggles and industrial disputes in the United States, Most emigrated himself, and promptly began agitating in his adopted land among other German émigrés.

He resumed the publication of Die Freiheit in New York. He was imprisoned in 1886, again in 1887, and in 1902, the last time for two months for publishing after the assassination of President McKinley

an editorial in which he argued that it was no crime to kill a ruler.

Most was famous for stating the concept of the Attentat

: "The existing system will be quickest and most radically overthrown by the annihilation of its exponents. Therefore, massacres of the enemies of the people must be set in motion." Most is best-known for a pamphlet published in 1885: The Science of Revolutionary Warfare: A Little Handbook of Instruction in the Use and Preparation of Nitroglycerine, Dynamite, Gun-Cotton, Fulminating Mercury, Bombs, Fuses, Poisons, Etc., Etc. This earned him the moniker "Dynamost." A gifted orator, Most propagated these ideas throughout Marxist and anarchist circles in the United States and attracted many adherents, most notably Emma Goldman

and Alexander Berkman

.

organizer, individualist anarchist, social activist, printer, publisher, essayist, and poet. He first joined the Socialist Labor Party in Detroit at the age of 27. In 1883, disenchanted with socialism, Labadie embraced individualist anarchism. He became closely allied with Benjamin Tucker, the country's foremost exponent of that doctrine, and frequently wrote for the latter's publication, "Liberty." Without the oppression of the state, Labadie believed, humans would choose to harmonize with "the great natural laws...without robbing [their] fellows through interest, profit, rent and taxes." However, his opposition to the State was not complete, as he supported government control of water utilities, streets, and railroads (Martin). Although he did not support the militant anarchism of the Haymarket anarchists, he fought for the clemency of the accused because he did not believe they were the perpetrators.

In 1888, Labadie organized the Michigan Federation of Labor, became its first president, and forged an alliance with Samuel Gompers. At age fifty he began writing verse and publishing artistic hand-crafted booklets. In 1908, the city postal inspector banned his mail because it bore stickers with anarchist quotations. A month later the Detroit water board, where he was working as a clerk, dismissed him for expressing anarchist sentiments. In both cases, the officials were forced to back down in the face of massive public protest for the person well-known in Detroit as its "Gentle Anarchist".

Voltairine de Cleyre

Voltairine de Cleyre

(November 17, 1866–June 20, 1912) was an individualist anarchist for several years before rejecting that label to embrace the philosophy of anarchism without adjectives

. In explaining her views on anarchism she said: "Anarchism...teaches the possibility of a society in which the needs of life may be fully supplied for all, and in which the opportunities for complete development of mind and body shall be the heritage of all... teaches that the present unjust organization of the production and distribution of wealth must finally be completely destroyed, and replaced by a system which will insure to each the liberty to work, without first seeking a master to whom he must surrender a tithe of his product, which will guarantee his liberty of access to the sources and means of production... Out of the blindly submissive, it makes the discontented; out of the unconsciously dissatisfied, it makes the consciously dissatisfied... Anarchism seeks to arouse the consciousness of oppression, the desire for a better society, and a sense of the necessity for unceasing warfare against capitalism and the State."

De Cleyre was held in high esteem by many anarchists. Emma Goldman

called her "the most gifted and brilliant anarchist woman America ever produced", and de Cleyre argued in Goldman's defense after Goldman was imprisoned for urging the hungry to expropriate food. In this speech, she condoned a right to take food when hungry but stopped short of advocating it: "I do not give you that advice... not that I do not think one little bit of sensitive human flesh is worth all the property rights in New York City... I say it is your business to decide whether you will starve and freeze in sight of food and clothing, outside of jail, or commit some overt act against the institution of property and take your place beside Timmermann and Goldman."

Her stance as an individualist versus a collectivist is controversial, with both sides claiming her as an adherent. In an 1894 article defending Emma Goldman, she states, "Miss Goldman is a communist; I am an individualist." Conversely, in a 1911 article entitled "The Mexican Revolution" she wrote that "The communistic customs of these people are very interesting and very instructive too...," in regards to Mexican Indian revolutionaries. Similarly, she instructs in "Why I am an Anarchist," that "the best thing ordinary workingmen or women could do was to organize their industry to get rid of money altogether . . . Let them produce together, co-operatively rather than as employer and employed; let them fraternize group by group, let each use what he needs of his own product, and deposit the rest in the storage-houses, and let those others who need goods have them as occasion arises." When she embraced "anarchism without adjectives", de Cleyre reasoned that: "Socialism and Communism both demand a degree of joint effort and administration which would beget more regulation than is wholly consistent with ideal Anarchism; Individualism and Mutualism, resting upon property, involve a development of the private policeman not at all compatible with my notion of freedom."

Luigi Galleani (1861 – November 4, 1931) was a 20th century anarchist best known for inspiring and advocating series of deadly bombings in the United States in 1919

Luigi Galleani (1861 – November 4, 1931) was a 20th century anarchist best known for inspiring and advocating series of deadly bombings in the United States in 1919

. Galleani is best described as an anarchist communist

and an insurrectionary anarchist

.

The activities of Galleani and his group centered around the promotion of a radical and violent form of anarchism, ostensibly by speeches, newsletters, labor agitation, political protests, and secret meetings. However, many of Galleani's followers used bombs and other violent means, practices Galleani encouraged, but never participated in. With the assistance of a friendly chemist and explosives expert, Professor Ettore Molinari, Galleani authored the booklet La Salute è in voi! (Health is in You!) a 46-page explicit guide to on bomb-making. The New York City Bomb Squad considered it accurate and practical, though Galleani made an error, corrected only in 1908, that resulted in one or more premature explosions.

n born, but she immigrated to the United States at seventeen. Goldman played a pivotal role in the development of anarchism

in the US and Europe throughout the first half of the twentieth century, and was a major contributor to the contemporary trade union

and feminism

movements in the US. She was imprisoned in 1893 at Blackwell's Island penitentiary for publicly urging unemployed workers that they should "Ask for work. If they do not give you work, ask for bread. If they do not give you work or bread, take bread."

She was convicted of "inciting a riot" by a criminal court of New York, despite the testimonies of twelve witnesses in her defense. The jury based their verdict on the testimony of one individual, a Detective Jacobs. Voltairine de Cleyre

gave the lecture In Defense of Emma Goldman as a response to this imprisonment. She was later deported to Russia for criticizing the US government during World War I

(especially for the draft

), where she witnessed the results of the Russian Revolution. Emma Goldman became one of the most prominent and respected representatives of anarchist communism

worldwide.

, a wealthy industrialist involved in a bitter dispute with steelworkers in Homestead, Pennsylvania

, in the belief that a violent act was needed to electrify the anarchist movement. He was arrested, convicted of attempted murder and sentenced to twenty-two years' imprisonment, of which he served fourteen years, many of them in solitary confinement (an account of which is contained in his book Prison Memoirs of an Anarchist

).

Upon regaining his freedom, Berkman– shattered and physically broken– joined Emma Goldman as one of the leading figures of the anarchist movement in the US. He was deported alongside Goldman and, with her, led the libertarian critique of the Soviet Communist Party, denouncing what they saw as the betrayal of the revolution. While they helped persuade the main organizations of the international anarchist and anarcho-syndicalist movement not to participate in the Third International controlled by the Russians, their impact on the wider world was only partially successful.

author, educational theorist, and social critic of the early and middle 20th century. He was editor of the first version of The Freeman

magazine, and author of many works, including Our Enemy, the State, often cited by modern intellectuals and pundits like Murray Rothbard as a pivotal example of the ideology of individual liberty. Albert Jay Nock, a self described "philosophical anarchist", called for a laissez faire vision of society free from the influence of the political state

. He described the state as that which "claims and exercises the monopoly of crime". He opposed centralization

, regulation

, the income tax

, and mandatory education, along with what he saw as the degradation of society

. He denounced in equal terms all forms of totalitarianism

, including "Bolshevism, Fascism

, Hitlerism, Marxism

, [and] Communism

", but was also harshly critical of democracy

. Nock argued instead that, "[t]he practical reason for freedom

is that freedom seems to be the only condition under which any kind of substantial moral fiber can be developed– we have tried law

, compulsion and authoritarianism

of various kinds, and the result is nothing to be proud of."

Nicola Sacco (April 22, 1891– August 23, 1927) and Bartolomeo Vanzetti (June 11, 1888– August 23, 1927) were two Italian

Nicola Sacco (April 22, 1891– August 23, 1927) and Bartolomeo Vanzetti (June 11, 1888– August 23, 1927) were two Italian

-born American anarchists

, influenced by Luigi Galleani

, who were arrested, tried

, and executed by electrocution

in the American

state

of Massachusetts

. Sacco and Vanzetti were accused of killing Frederick Parmenter, a shoe factory paymaster

, and Alessandro Berardelli, a security guard

, and of robbery

of $

15,766.51 from the factory's payroll

on April 15, 1920. Both Sacco and Vanzetti had alibi

s, but they were the only people accused of the crime. As a result of what many historians feel was a blatant disregard for political civil liberties

and strong anti-Italian prejudice

, Sacco and Vanzetti were denied a retrial. Judge Webster Thayer

, who heard the case, allegedly described the two as "anarchist bastards". The song "Two good men" by Woody Guthrie

recounts the tale.

pacifist

, Christian anarchist

, vegetarian

, social activist, member of the Catholic Worker Movement

and a Wobbly

. He established the "Joe Hill House of Hospitality

" in Salt Lake City, Utah

and practiced tax resistance

.

individualist anarchist Lathe operator, house painter, bricklayer, dramatist and political activist influenced by the work of Max Stirner

. He took the pseudonym "Brand" from a fictional character in one of Henrik Ibsen

´s plays. In the 1910s he started becoming involved in anarchist and anti-war activism around Milan. From the 1910s until the 1920s he participated in anarchist activities and popular uprisings in various countries including Switzerland, Germany, Hungary, Argentina and Cuba. He lived from the 1920s onwards in New York City and there he edited the individualist anarchist eclectic journal Eresia in 1928. He also wrote for other american anarchist publications such as L' Adunata dei refrattari

, Cultura Obrera, Controcorrente and Intessa Libertaria. During the Spanish Civil War

, he went to fight with the anarchists but was imprisoned and was helped on his release by Emma Goldman

. Afterwards Arrigoni became a longtime member of the Libertarian Book Club in New York City. He died in New York City when he was 90 years old on December 7, 1986.

(1960) and an activist on the pacifist Left in the 1960s and an inspiration to that era's student movement. He is less remembered as a co-founder of Gestalt Therapy

in the 1940s and '50s. In the mid-1940s, together with C. Wright Mills

, he contributed to Politics

, the journal edited during the 1940s by Dwight Macdonald

. In 1947, he published two books, Kafka's Prayer and Communitas

, a classic study of urban design coauthored with his brother Percival Goodman

. Fame came only with the 1960 publication of his Growing Up Absurd: Problems of Youth in the Organized System

. Goodman wrote on a wide variety of subjects; including education, Gestalt Therapy, city life and urban design

, children's rights

, politics, literary criticism

, and many more.

, which opposes the state and supports a free market. The relationship between anarcho-capitalism and the forms of free-market anarchism that preceded it is controversial. Rothbard was "a student and disciple of the Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises

, [who] combined the laissez-faire economics of his teacher with the absolutist views of human rights and rejection of the state he had absorbed from studying the individualist American anarchists of the nineteenth century such as Lysander Spooner and Benjamin Tucker." In The Ethics of Liberty

, Rothbard asserted the right of 100 percent self-ownership

, as the only principle compatible with a moral code that applies to every person - a "universal ethic" - and that it is a natural law by being what is naturally best for man.

Like the nineteenth century individualists, Rothbard believed that security should be provided by multiple competing businesses rather than by a tax-funded central agency. However, he rejected their labor theory of value

in favor of the modern neo-classical marginalist

view. Thus, like most modern economists, he did not believe that prices in a free market would, or should be, proportional to labor, or that "usury" or "exploitation" necessarily occurs where they are disproportionate. Instead, he believed that different prices of goods and services in a free market are ultimately the result of goods and services having different marginal utilities and that there is nothing unjust about this. Rothbard also disagreed with Tucker that interest would disappear with unregulated banking and money issuance. Rothbard believed that people in general do not wish to lend their money to others without compensation, so there is no reason why this would change where banking is unregulated. Nor, did he agree that unregulated banking would increase the supply of money because he believed the supply of money in a truly free market is self-regulating. And, he believed that it is good that it would not increase the supply or inflation would result. - Rothbard, Murray. The Spooner-Tucker Doctrine: An Economist's View

According to mutualist Kevin Carson, "most people who call themselves 'individualist anarchists' today are followers of Murray Rothbard's Austrian economics." Some contemporary individualists are not anarcho-capitalists. Rothbard strongly opposed communism in all its forms and other related ideologies that demand that wealth be distributed collectively instead of held individually. In anarcho-capitalism, the individual has no obligation to any other member of the community other than to refrain from aggressing against others or defrauding them (the Non-aggression principle

.)

anarchist, political and social philosopher, environmentalist

/conservationist

, atheist, speaker, and writer. For much of his life he called himself an anarchist, although as early as 1995 he privately renounced his identification with the anarchist movement. A pioneer in the ecology

movement, Bookchin was the founder of the social ecology

movement within libertarian socialist and ecological thought. He was the author of two dozen books on politics, philosophy, history, and urban affairs as well as ecology.

Bookchin was an anti-capitalist

and vocal advocate of the decentralisation

as well as partial deindustrialization

and deurbanization

of society. His writings on libertarian municipalism

, a theory of face-to-face, grassroots democracy, had an influence on the Green movement

and anti-capitalist direct action

groups such as Reclaim the Streets

. He was a staunch critic of biocentric

philosophies such as deep ecology

and the biologically deterministic

beliefs of sociobiology

, and his criticisms of "new age

" Greens such as Charlene Spretnak

contributed to the divisions that affected the North American Green movement in the 1990s.

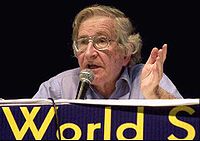

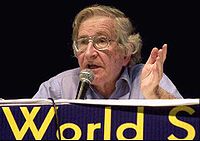

Noam Chomsky (icon; born December 7, 1928) is an American linguist, philosopher, cognitive scientist

Noam Chomsky (icon; born December 7, 1928) is an American linguist, philosopher, cognitive scientist

, political activist, author, and lecturer. He is an Institute Professor

and professor emeritus

of linguistics

at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

. Chomsky is well known in the academic and scientific community as one of the fathers of modern linguistics

. Since the 1960s, he has become known more widely as a political dissident, an anarchist, and a libertarian socialist

intellectual. Chomsky is often viewed as a notable figure in contemporary philosophy

.

Chomsky has stated that his "personal visions are fairly traditional anarchist ones, with origins in The Enlightenment and classical liberalism" and he has praised libertarian socialism

. He is a sympathizer of anarcho-syndicalism

and a member of the IWW

union. He wrote a book on anarchism titled, "Chomsky on Anarchism," which was published by the anarchist book collective, AK Press

, in 2006.

Noam Chomsky has been engaged in political activism all his adult life and expressed opinions on politics and world events that are widely cited, publicized, and discussed. Chomsky in turn argues that his views are those which the powerful do not want to hear, and for this reason considers himself an American political dissident

.

(born 1943) is an American

anarchist

and primitivist

philosopher and author. His works criticize agricultural

civilization

as inherently oppressive, and advocate drawing upon the ways of life of prehistoric humans as an inspiration for what a free society should look like. Some of his criticism has extended as far as challenging domestication

, language

, symbolic thought (such as mathematics

and art

) and the concept of time. His five major books are Elements of Refusal (1988), Future Primitive and Other Essays

(1994), Running on Emptiness (2002), Against Civilization: Readings and Reflections

(2005) and Twilight of the Machines (2008).

On May 7, 1995, a full-page interview with Zerzan was featured in The New York Times

. Another significant event that shot Zerzan to celebrity philosopher status was his association with members of the Eugene, Oregon

anarchist scene that later were the driving force behind the use of black bloc

tactics at the 1999 anti-World Trade Organization

protests in Seattle, Washington. Anarchists using black bloc tactics were thought to be chiefly responsible for the property destruction committed at numerous corporate storefronts and banks.

anarchist and lawyer

. He is the author of The Abolition of Work and Other Essays

, Beneath the Underground, Friendly Fire, Anarchy After Leftism, and numerous political essays. Kenn Thomas

hailed Black in 1999 as a "defender of the most liberatory tendencies within modern anti-authoritarian thought".

activist, speaker, and writer. He is co-editor of ZNet, and co-editor and co-founder of Z Magazine. He also co-founded South End Press

and has written numerous books and articles. He developed along with Robin Hahnel

the economic vision called participatory economics

.

Albert identifies himself as a market abolitionist and favors democratic participatory planning as an alternative.

During the 1960s, Albert was a member of Students for a Democratic Society

, and was active in the anti-Vietnam War movement

. Albert's memoir, Remembering Tomorrow: From SDS to Life After Capitalism (ISBN 1583227423), was published in 2007 by Seven Stories Press

.

philosopher involved in theoretical and practical activity, who now goes by the name Apio Ludd. He edited the anarchist publication Willful Disobedience, which was published from 1996 until 2005, and currently publishes a variety of anarchist, radical, surrealist

and poetic pamphlets and booklets through his project, Venomous Butterfly Publication. His ideas are influenced by insurrectionary anarchism

, Max Stirner

's egoism, surrealism

, the Situationist International and non-primitivist critiques of civilization. He previously published under the pen name Feral Faun.

Philosophy

Philosophy is the study of general and fundamental problems, such as those connected with existence, knowledge, values, reason, mind, and language. Philosophy is distinguished from other ways of addressing such problems by its critical, generally systematic approach and its reliance on rational...

, from individualist anarchism

Individualist anarchism

Individualist anarchism refers to several traditions of thought within the anarchist movement that emphasize the individual and his or her will over external determinants such as groups, society, traditions, and ideological systems. Individualist anarchism is not a single philosophy but refers to a...

to anarchist communism

Anarchist communism

Anarchist communism is a theory of anarchism which advocates the abolition of the state, markets, money, private property, and capitalism in favor of common ownership of the means of production, direct democracy and a horizontal network of voluntary associations and workers' councils with...

and other less known forms. America has two main traditions, native and immigrant, with the native tradition being strongly individualist and the immigrant tradition being collectivist and anarcho-communist. Influential American anarchists include Josiah Warren

Josiah Warren

Josiah Warren was an individualist anarchist, inventor, musician, and author in the United States. He is widely regarded as the first American anarchist, and the four-page weekly paper he edited during 1833, The Peaceful Revolutionist, was the first anarchist periodical published, an enterprise...

, Henry David Thoreau

Henry David Thoreau

Henry David Thoreau was an American author, poet, philosopher, abolitionist, naturalist, tax resister, development critic, surveyor, historian, and leading transcendentalist...

, Lysander Spooner

Lysander Spooner

Lysander Spooner was an American individualist anarchist, political philosopher, Deist, abolitionist, supporter of the labor movement, legal theorist, and entrepreneur of the nineteenth century. He is also known for competing with the U.S...

, Lucy Parsons

Lucy Parsons

Lucy Eldine Gonzalez Parsons was an American labor organizer and radical socialist. She is remembered as a powerful orator.-Life:...

, Murray Rothbard

Murray Rothbard

Murray Newton Rothbard was an American author and economist of the Austrian School who helped define capitalist libertarianism and popularized a form of free-market anarchism he termed "anarcho-capitalism." Rothbard wrote over twenty books and is considered a centrally important figure in the...

, Benjamin Tucker

Benjamin Tucker

Benjamin Ricketson Tucker was a proponent of American individualist anarchism in the 19th century, and editor and publisher of the individualist anarchist periodical Liberty.-Summary:Tucker says that he became an anarchist at the age of 18...

, Voltairine de Cleyre

Voltairine de Cleyre

Voltairine de Cleyre was an American anarchist writer and feminist. She was a prolific writer and speaker, opposing the state, marriage, and the domination of religion in sexuality and women's lives. She began her activist career in the freethought movement...

, Johann Most

Johann Most

Johann Joseph Most was a German-American politician, newspaper editor, and orator. He is credited with popularizing the concept of "Propaganda of the deed". His grandson was Boston Celtics radio play-by-play man Johnny Most...

, Luigi Galleani

Luigi Galleani

Luigi Galleani was an Italian anarchist active in the United States from 1901 to 1919, viewed by historians as an anarchist communist and an insurrectionary anarchist. He is best known for his enthusiastic advocacy of "propaganda of the deed", i.e...

, Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman was an anarchist known for her political activism, writing and speeches. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europe in the first half of the twentieth century....

, Alexander Berkman

Alexander Berkman

Alexander Berkman was an anarchist known for his political activism and writing. He was a leading member of the anarchist movement in the early 20th century....

, social ecologist

Social ecology

Social ecology is a philosophy developed by Murray Bookchin in the 1960s.It holds that present ecological problems are rooted in deep-seated social problems, particularly in dominatory hierarchical political and social systems. These have resulted in an uncritical acceptance of an overly...

Murray Bookchin

Murray Bookchin

Murray Bookchin was an American libertarian socialist author, orator, and philosopher. A pioneer in the ecology movement, Bookchin was the founder of the social ecology movement within anarchist, libertarian socialist and ecological thought. He was the author of two dozen books on politics,...

, Paul Goodman

Paul Goodman (writer)

Paul Goodman was an American sociologist, poet, writer, anarchist, and public intellectual. Goodman is now mainly remembered as the author of Growing Up Absurd and an activist on the pacifist Left in the 1960s and an inspiration to that era's student movement...

, linguist Noam Chomsky

Noam Chomsky

Avram Noam Chomsky is an American linguist, philosopher, cognitive scientist, and activist. He is an Institute Professor and Professor in the Department of Linguistics & Philosophy at MIT, where he has worked for over 50 years. Chomsky has been described as the "father of modern linguistics" and...

and John Zerzan

John Zerzan

John Zerzan is an American anarchist and primitivist philosopher and author. His works criticize agricultural civilization as inherently oppressive, and advocate drawing upon the ways of life of prehistoric humans as an inspiration for what a free society should look like...

.

The first American anarchist publication was The Peaceful Revolutionist, edited by Josiah Warren

Josiah Warren

Josiah Warren was an individualist anarchist, inventor, musician, and author in the United States. He is widely regarded as the first American anarchist, and the four-page weekly paper he edited during 1833, The Peaceful Revolutionist, was the first anarchist periodical published, an enterprise...

, whose earliest experiments and writings predate Pierre Proudhon.

Indigenous anarchism

In general, Indigenous anarchism describes the majority of pre-Columbian native North American societies as anarchist in structure and function. Such claims are easiest to document among Indigenous peoples in some parts of what is now California, but the Iroquois League, the Mohawk Federation, and many other indigenous tribal governing structures throughout North America have been described as anarchist in structure. Despite this, some Native groups were far from an anarchist ideal; the MississippianMississippian culture

The Mississippian culture was a mound-building Native American culture that flourished in what is now the Midwestern, Eastern, and Southeastern United States from approximately 800 CE to 1500 CE, varying regionally....

, Aztec

Aztec

The Aztec people were certain ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those groups who spoke the Nahuatl language and who dominated large parts of Mesoamerica in the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries, a period referred to as the late post-classic period in Mesoamerican chronology.Aztec is the...

, Inca, and Maya

Maya civilization

The Maya is a Mesoamerican civilization, noted for the only known fully developed written language of the pre-Columbian Americas, as well as for its art, architecture, and mathematical and astronomical systems. Initially established during the Pre-Classic period The Maya is a Mesoamerican...

cultures were clearly statist.

More recently, many participants in the American Indian Movement

American Indian Movement

The American Indian Movement is a Native American activist organization in the United States, founded in 1968 in Minneapolis, Minnesota by urban Native Americans. The national AIM agenda focuses on spirituality, leadership, and sovereignty...

have described themselves as anarchist and cooperation between anarchist and Indigenous groups has been a key feature of movements such as the Minnehaha Free State in Minneapolis, Minnesota

Minnesota

Minnesota is a U.S. state located in the Midwestern United States. The twelfth largest state of the U.S., it is the twenty-first most populous, with 5.3 million residents. Minnesota was carved out of the eastern half of the Minnesota Territory and admitted to the Union as the thirty-second state...

- (which is built on an Ojibwa

Ojibwa

The Ojibwe or Chippewa are among the largest groups of Native Americans–First Nations north of Mexico. They are divided between Canada and the United States. In Canada, they are the third-largest population among First Nations, surpassed only by Cree and Inuit...

Reservation

Indian reservation

An American Indian reservation is an area of land managed by a Native American tribe under the United States Department of the Interior's Bureau of Indian Affairs...

) - and at Big Mountain.

Outside of indigenous communities, green anarchists

Green anarchism

Green anarchism, or ecoanarchism, is a school of thought within anarchism which puts a particular emphasis on environmental issues. An important early influence was the thought of the American anarchist Henry David Thoreau and his book Walden...

have been the most vocal in declaring solidarity with ongoing indigenous struggles, but social anarchists

Social anarchism

Social anarchism is a term originally used in 1971 by Giovanni Baldelli as the title of his book where he discusses the organization of an ethical society from an anarchist point of view...

in general are supportive as well.

Individualist anarchism

Native anarchism in the United States has a long pedigree that begins with the antinomianAntinomianism

Antinomianism is defined as holding that, under the gospel dispensation of grace, moral law is of no use or obligation because faith alone is necessary to salvation....

controversy in Puritan

Puritan

The Puritans were a significant grouping of English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries. Puritanism in this sense was founded by some Marian exiles from the clergy shortly after the accession of Elizabeth I of England in 1558, as an activist movement within the Church of England...

New England

New England

New England is a region in the northeastern corner of the United States consisting of the six states of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut...

. Some consider the first anarchist

Christian anarchism

Christian anarchism is a movement in political theology that combines anarchism and Christianity. It is the belief that there is only one source of authority to which Christians are ultimately answerable, the authority of God as embodied in the teachings of Jesus...

in America to be Anne Hutchinson

Anne Hutchinson

Anne Hutchinson was one of the most prominent women in colonial America, noted for her strong religious convictions, and for her stand against the staunch religious orthodoxy of 17th century Massachusetts...

(1591–1643), a proto-feminist

Christian feminism

Christian feminism is an aspect of feminist theology which seeks to advance and understand the equality of men and women morally, socially, spiritually, and in leadership from a Christian perspective. Christian feminists argue that contributions by women in that direction are necessary for a...

individualist.

The U.S., with its tradition of radical individualism

Individualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology, or social outlook that stresses "the moral worth of the individual". Individualists promote the exercise of one's goals and desires and so value independence and self-reliance while opposing most external interference upon one's own...

, which is "enshrined in the Declaration of Independence

United States Declaration of Independence

The Declaration of Independence was a statement adopted by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, which announced that the thirteen American colonies then at war with Great Britain regarded themselves as independent states, and no longer a part of the British Empire. John Adams put forth a...

", was a congenial environment for individualist anarchism. Josiah Warren cited the Declaration of Independence and Benjamin Tucker said that "Anarchists are simply unterrified Jeffersonian Democrats." In 1833 Josiah Warren began publishing "the first explicitly anarchist newspaper in the United States", called "The Peaceful Revolutionist." According to Rudolph Rocker, the American individualist anarchists were "influenced in their intellectual development much more by the principles expressed in the Declaration of Independence than by those of any of the representatives of libertarian socialism in Europe. They were all 'one hundred percent American' by descent, and almost all of them were born in the New England states. As a matter of fact, this school of thought had found literary expression in America before any modern radical movements were even thought of in Europe."

Beginning in 1881, Benjamin Tucker began publishing "Liberty," which was a forum to propagate individualist anarchist ideas. By that time, anarcho-communism and propaganda by the deed was arriving in America, "both of which Tucker detested." Tucker criticized the immigrant anarcho-communist Alexander Berkman's attempt to assassinate Henry Clay Frick, saying "The hope of humanity lies in the avoidance of that revolution by force which the Berkmans are trying to precipitate. No pity for Frick, no praise for Berkman such is the attitude of Liberty in the present crisis."

By the twentieth century, individualist anarchism in America was in decline. It was later revived by Murray Rothbard and the anarcho-capitalists in the mid-twentieth century.

According to Carlotta Anderson:

Social anarchism

Social anarchism in the contemporary United StatesUnited States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

has roots tracing back to well before the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

. Early leaders included Albert Parsons

Albert Parsons

Albert Richard Parsons was a pioneer American socialist and later anarchist newspaper editor, orator, and labor activist...

, his wife Lucy Parsons

Lucy Parsons

Lucy Eldine Gonzalez Parsons was an American labor organizer and radical socialist. She is remembered as a powerful orator.-Life:...

, along with many immigrants who brought their radicalism with them such as Johann Most

Johann Most

Johann Joseph Most was a German-American politician, newspaper editor, and orator. He is credited with popularizing the concept of "Propaganda of the deed". His grandson was Boston Celtics radio play-by-play man Johnny Most...

, Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman was an anarchist known for her political activism, writing and speeches. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europe in the first half of the twentieth century....

, and Big Bill Haywood, and many others. Their influence on the early American labor movement was dramatic, with the execution of Albert Parsons and the other Haymarket Martyrs providing a key rallying cry for the early American labor movement and spurring the creation of radical unions throughout the country. The largest - the Industrial Workers of the World

Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World is an international union. At its peak in 1923, the organization claimed some 100,000 members in good standing, and could marshal the support of perhaps 300,000 workers. Its membership declined dramatically after a 1924 split brought on by internal conflict...

, was founded in 1905. Swedish-American musician Joe Hill

Joe Hill

Joe Hill, born Joel Emmanuel Hägglund in Gävle , and also known as Joseph Hillström was a Swedish-American labor activist, songwriter, and member of the Industrial Workers of the World...

is also one of the most famous social anarchist protest singers to have ever lived.

Social anarchism includes anarcho-communism, anarcho-syndicalism

Anarcho-syndicalism

Anarcho-syndicalism is a branch of anarchism which focuses on the labour movement. The word syndicalism comes from the French word syndicat which means trade union , from the Latin word syndicus which in turn comes from the Greek word σύνδικος which means caretaker of an issue...

, libertarian socialism

Libertarian socialism

Libertarian socialism is a group of political philosophies that promote a non-hierarchical, non-bureaucratic, stateless society without private property in the means of production...

, and other forms of anarchism that take the creation of social goods as their first priority.

Insurrectionary anarchism

Insurrectionary anarchism is a revolutionary theory, practice, and tendency within the anarchist movement that opposes formal anarchist organizations such as labor unions and federations that are based on a political program and periodic congresses. Instead, insurrectionary anarchists advocate direct action (violent or otherwise), informal organization, including small affinity groups and mass organizations that include non-anarchist individuals of the exploited or excluded class.Many anarchist communists

Anarchist communism

Anarchist communism is a theory of anarchism which advocates the abolition of the state, markets, money, private property, and capitalism in favor of common ownership of the means of production, direct democracy and a horizontal network of voluntary associations and workers' councils with...

, such as the publishers of Barricada magazine in the United States and foreign immigrants to the US such as Luigi Galleani

Luigi Galleani

Luigi Galleani was an Italian anarchist active in the United States from 1901 to 1919, viewed by historians as an anarchist communist and an insurrectionary anarchist. He is best known for his enthusiastic advocacy of "propaganda of the deed", i.e...

and Johann Most

Johann Most

Johann Joseph Most was a German-American politician, newspaper editor, and orator. He is credited with popularizing the concept of "Propaganda of the deed". His grandson was Boston Celtics radio play-by-play man Johnny Most...

have been insurrectionary anarchists.

Re-emergence of anarchism in the U.S.

Anarchism dwindled into obscurity until the 1960s when it resurfaced and then "shattered into various anarchist splinters. These ranged from Anarcho-Capitalists who desired the organization of society solely on the basis of a free marketFree market

A free market is a competitive market where prices are determined by supply and demand. However, the term is also commonly used for markets in which economic intervention and regulation by the state is limited to tax collection, and enforcement of private ownership and contracts...

to Anarcho-Communists who sought an individualized society of decentralized communes." Anarchism started making a comeback in the United States in the early 1960s, primarily through the influence of the Beat

Beat generation

The Beat Generation refers to a group of American post-WWII writers who came to prominence in the 1950s, as well as the cultural phenomena that they both documented and inspired...

artists. Later in the 1960s, activists such as Abbie Hoffman

Abbie Hoffman

Abbot Howard "Abbie" Hoffman was a political and social activist who co-founded the Youth International Party ....

and the Diggers

Diggers (theater)

The Diggers were a radical community-action group of activists and Improv actors operating from 1966–68, based in the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood of San Francisco. Their politics were such that they have sometimes been categorized as "left-wing." More accurately, they were "community anarchists"...

identified with anarchism and were notable for the spectacular ways they put anarchist ideas into practice. In the late 60s, Murray Rothbard

Murray Rothbard

Murray Newton Rothbard was an American author and economist of the Austrian School who helped define capitalist libertarianism and popularized a form of free-market anarchism he termed "anarcho-capitalism." Rothbard wrote over twenty books and is considered a centrally important figure in the...

and Karl Hess

Karl Hess

Karl Hess was an American national-level speechwriter and author. He was also a political philosopher, editor, welder, motorcycle racer, tax resister, atheist, and libertarian activist...

began to call themselves anarchists and published Left and Right: A Journal of Libertarian Thought. In 1969, The Match!, which bills itself as a "Journal of Ethical Anarchism" began publication by anarchist without adjectives Fred Woodworth

Fred Woodworth

Fred Woodworth is an anarchist and atheist writer based in the United States. He is an anarchist without adjectives, saying: "I have no prefix or adjective for my anarchism. I think syndicalism can work, as can free-market anarcho-capitalism, anarcho-communism, even anarcho-hermits, depending on...

and has published continuously since then.

In the 1970s, anarchist ideas caught on in the anti-nuclear, feminist, and environmental movements. Murray Bookchin

Murray Bookchin

Murray Bookchin was an American libertarian socialist author, orator, and philosopher. A pioneer in the ecology movement, Bookchin was the founder of the social ecology movement within anarchist, libertarian socialist and ecological thought. He was the author of two dozen books on politics,...

was a widely read anarchist thinker whose books on the environment were influential on the environmental movement. Anarchist tactics such as the affinity group were adopted by women involved in the radical feminist movement.

Anarchists became more visible in the 1980s, as a result of publishing, protests and conventions. In 1980, the First International Symposium on Anarchism was held in Portland, Oregon. In 1986, the Haymarket Remembered conference was held in Chicago, to observe the centennial of the infamous Haymarket Riot. This conference was followed by annual, continental conventions in Minneapolis (1987), Toronto (1988), and San Francisco (1989).

Recently there has been a resurgence in anarchist ideals in the United States. In the 1990s, a group of anarchists formed the Love and Rage Network, which was one of several new groups and projects formed in the U.S. during the decade. American anarchists increasingly became noticeable at protests, especially through a tactic known as the Black bloc

Black bloc

A black bloc is a tactic for protests and marches, whereby individuals wear black clothing, scarves, ski masks, motorcycle helmets with padding, or other face-concealing items...

. U.S. anarchists became more prominent in 1999 as a result of the anti-WTO protests

WTO Ministerial Conference of 1999 protest activity

Protest activity surrounding the WTO Ministerial Conference of 1999, which was to be the launch of a new millennial round of trade negotiations, occurred on November 30, 1999 , when the World Trade Organization convened at the Washington State Convention and Trade Center in Seattle, Washington,...

in Seattle.

In the wake of hurricane Katrina, anarchist activists have been visible as founding members of the Common Ground Collective

Common Ground Collective

The Common Ground Collective is a decentralized network of non-profit organizations offering support to the residents of New Orleans. It was formed in the Algiers neighborhood of the city in the days after Hurricane Katrina in 2005.-History:...

.

Josiah Warren

Josiah Warren published a periodical called The Peaceful Revolutionist in 1833, which some believe to be the first anarchist newspaper. Warren had participated in a failed collectivist experiment headed by Robert OwenRobert Owen

Robert Owen was a Welsh social reformer and one of the founders of utopian socialism and the cooperative movement.Owen's philosophy was based on three intellectual pillars:...

called "New Harmony

New Harmony, Indiana

New Harmony is a historic town on the Wabash River in Harmony Township, Posey County, Indiana, United States. It lies north of Mount Vernon, the county seat. The population was 916 at the 2000 census. It is part of the Evansville metropolitan area. Many of the old Harmonist buildings still stand...

," but was disappointed in its failure. He stressed the need for individual sovereignty. In True Civilization Warren equates "Sovereignty of the Individual" with the Declaration of Independence

Declaration of independence

A declaration of independence is an assertion of the independence of an aspiring state or states. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the territory of another nation or failed nation, or are breakaway territories from within the larger state...

's assertion of the inalienable rights. He claims that every person has an "instinct" for individual sovereignty, making individual rights inalienable and inviolate.

Basing his economics on the labor theory of value, Warren's economic principle was "cost the limit of price

Cost the limit of price

Cost the limit of price was a maxim coined by Josiah Warren, indicating a version of the labor theory of value. Warren maintained that the just compensation for labor could only be an equivalent amount of labor . Thus, profit, rent, and interest were considered unjust economic arrangements...

," with "cost" referring to the amount of labor incurred in producing a commodity and bringing it to market. He opposed what he called "value the limit of price," where prices paid are determined simply by subjective valuation irrespective of labor costs, as being inequitable or unfair. In 1827, Warren put his theories into practice by starting a business called the Cincinnati Time Store

Cincinnati Time Store

The Cincinnati Time Store was a successful retail store that was created by American individualist anarchist Josiah Warren to test his theories that were based on his strict interpretation of the labor theory of value. The experimental store operated from May 18, 1827 until May 1830...

where the trade of goods was facilitated by private currency denominated in hours of labor. Warren was a strong supporter of the right of individuals to retain the product of their labor as private possessions. This position was shared by fellow anarchist Stephen Pearl Andrews

Stephen Pearl Andrews

Stephen Pearl Andrews was an American individualist anarchist and author of several books on Individualist anarchism.-Early life and work:...

.

Henry David Thoreau

Henry David Thoreau (July 12, 1817– May 6, 1862; was an AmericanUnited States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

author, development critic

Development criticism

Development criticism refers to criticisms of technological development.-Notable development critics:*Edward Abbey*John Africa*Stafford Beer *Charles A...

, naturalist, transcendentalist

Transcendentalism

Transcendentalism is a philosophical movement that developed in the 1830s and 1840s in the New England region of the United States as a protest against the general state of culture and society, and in particular, the state of intellectualism at Harvard University and the doctrine of the Unitarian...

, pacifist

Pacifism

Pacifism is the opposition to war and violence. The term "pacifism" was coined by the French peace campaignerÉmile Arnaud and adopted by other peace activists at the tenth Universal Peace Congress inGlasgow in 1901.- Definition :...

, tax resister

Tax resistance

Tax resistance is the refusal to pay tax because of opposition to the government that is imposing the tax or to government policy.Tax resistance is a form of civil disobedience and direct action...

and philosopher who is famous for Walden

Walden

Walden is an American book written by noted Transcendentalist Henry David Thoreau...

, on simple living

Simple living

Simple living encompasses a number of different voluntary practices to simplify one's lifestyle. These may include reducing one's possessions or increasing self-sufficiency, for example. Simple living may be characterized by individuals being satisfied with what they need rather than want...

amongst nature, and Civil Disobedience

Civil disobedience

Civil disobedience is the active, professed refusal to obey certain laws, demands, and commands of a government, or of an occupying international power. Civil disobedience is commonly, though not always, defined as being nonviolent resistance. It is one form of civil resistance...

. In 1849, Henry David Thoreau wrote "I heartily accept the motto, 'That government is best which governs least'; and I should like to see it acted up to more rapidly and systematically. Carried out, it finally amounts to this, which also I believe– 'That government is best which governs not at all'; and when men are prepared for it, that will be the kind of government which we will have." Although Thoreau never labeled himself an "anarchist," he has been regarded to be an individualist anarchist

Individualist anarchism

Individualist anarchism refers to several traditions of thought within the anarchist movement that emphasize the individual and his or her will over external determinants such as groups, society, traditions, and ideological systems. Individualist anarchism is not a single philosophy but refers to a...

.

William B. Greene

William Batchelder GreeneWilliam Batchelder Greene

William Batchelder Greene was a 19th century individualist anarchist, Unitarian minister, soldier and promotor of free banking in the United States.-Biography:...

(1819–1878) was an author, soldier, currency reformer, individualist anarchist, Unitarian minister and philosopher, active in transcendentalist

Transcendentalism

Transcendentalism is a philosophical movement that developed in the 1830s and 1840s in the New England region of the United States as a protest against the general state of culture and society, and in particular, the state of intellectualism at Harvard University and the doctrine of the Unitarian...

circles. In works such as Equality (1849) and Mutual Banking (1850) he synthesized the work of French socialists such as P.-J. Proudhon

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon was a French politician, mutualist philosopher and socialist. He was a member of the French Parliament, and he was the first person to call himself an "anarchist". He is considered among the most influential theorists and organisers of anarchism...

and Pierre Leroux

Pierre Leroux

Pierre Henri Leroux , French philosopher and political economist, was born at Bercy, now a part of Paris, the son of an artisan.- Life :...

with that of American currency reformers such as William Beck and Edward Kellogg. The result was a unique form of Christian mutualism

Mutualism (economic theory)

Mutualism is an anarchist school of thought that originates in the writings of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, who envisioned a society where each person might possess a means of production, either individually or collectively, with trade representing equivalent amounts of labor in the free market...

, which attempted to harmonize elements of capitalism

Capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system that became dominant in the Western world following the demise of feudalism. There is no consensus on the precise definition nor on how the term should be used as a historical category...

, communism

Communism

Communism is a social, political and economic ideology that aims at the establishment of a classless, moneyless, revolutionary and stateless socialist society structured upon common ownership of the means of production...

and socialism

Socialism

Socialism is an economic system characterized by social ownership of the means of production and cooperative management of the economy; or a political philosophy advocating such a system. "Social ownership" may refer to any one of, or a combination of, the following: cooperative enterprises,...

. Greene was later involved with the New England Labor Reform League, and with the anti-death penalty work of The Prisoner's Friend. He was a regular contributor to Ezra Heywood's The Word until his death. William B. Greene's mutualistic

Mutualism (economic theory)

Mutualism is an anarchist school of thought that originates in the writings of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, who envisioned a society where each person might possess a means of production, either individually or collectively, with trade representing equivalent amounts of labor in the free market...

economic philosophy resembles the economic philosophy of the earlier French anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon was a French politician, mutualist philosopher and socialist. He was a member of the French Parliament, and he was the first person to call himself an "anarchist". He is considered among the most influential theorists and organisers of anarchism...

and the economic system of the land banks that existed in the United States during the colonial period.

Albert and Lucy Parsons

International Working People's Association

The International Working People's Association , sometimes known as the "Black International," was an international anarchist political organization established in 1881 at a convention held in London, England...

(IWPA). When he first came to Chicago, he found a job as a writer for the Times. Later in 1877, as a result of his becoming an outspoken supporter of worker's rights, he lost his position at the Times and was blacklisted by the industry altogether. Police Superintendent Michael Hickey told Parsons to leave Chicago during this time because his life was in danger. He then became devoted completely to his new anarchist ideas in favor of workers' rights and especially the eight-hour work day labor movement.

In addition to his involvement in the IWPA, Parsons was also involved with the Knights of Labor

Knights of Labor

The Knights of Labor was the largest and one of the most important American labor organizations of the 1880s. Its most important leader was Terence Powderly...

during its embryonic period. Parsons joined the Knights of Labor, known then as "The Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor," on July 4, 1876. At the time Parsons joined, the Knights of Labor was just a small fraternal organization with elaborate rituals, most of them copied from the Masons.

Lucy Parsons

Lucy Parsons

Lucy Eldine Gonzalez Parsons was an American labor organizer and radical socialist. She is remembered as a powerful orator.-Life:...

(1853-March 7, 1942), the widow of Albert Parsons, was a radical

Radicalization

Radicalization is the process in which an individual changes from passiveness or activism to become more revolutionary, militant or extremist. Radicalization is often associated with youth, adversity, alienation, social exclusion, poverty, or the perception of injustice to self or others.-...

American

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

labor organizer, anarchist communist, and is remembered as a powerful orator. A founder of the Industrial Workers of the World

Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World is an international union. At its peak in 1923, the organization claimed some 100,000 members in good standing, and could marshal the support of perhaps 300,000 workers. Its membership declined dramatically after a 1924 split brought on by internal conflict...