Slavery in Ancient Greece

Encyclopedia

Slavery

Slavery is a system under which people are treated as property to be bought and sold, and are forced to work. Slaves can be held against their will from the time of their capture, purchase or birth, and deprived of the right to leave, to refuse to work, or to demand compensation...

was common practice and an integral component of ancient Greece

Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece is a civilization belonging to a period of Greek history that lasted from the Archaic period of the 8th to 6th centuries BC to the end of antiquity. Immediately following this period was the beginning of the Early Middle Ages and the Byzantine era. Included in Ancient Greece is the...

throughout its rich history, as it was in other societies of the time including ancient Israel and early Christian societies. It is estimated that in Athens

Athens

Athens , is the capital and largest city of Greece. Athens dominates the Attica region and is one of the world's oldest cities, as its recorded history spans around 3,400 years. Classical Athens was a powerful city-state...

, the majority of citizens

Polis

Polis , plural poleis , literally means city in Greek. It could also mean citizenship and body of citizens. In modern historiography "polis" is normally used to indicate the ancient Greek city-states, like Classical Athens and its contemporaries, so polis is often translated as "city-state."The...

owned at least one slave. Most ancient writers considered slavery not only natural but necessary, but some isolated debate began to appear, notably in Socratic dialogues while the Stoics produced the first condemnation of slavery recorded in history.

In conformity with modern historiographical

Historiography

Historiography refers either to the study of the history and methodology of history as a discipline, or to a body of historical work on a specialized topic...

practice, this article will discuss only chattel

Personal property

Personal property, roughly speaking, is private property that is moveable, as opposed to real property or real estate. In the common law systems personal property may also be called chattels or personalty. In the civil law systems personal property is often called movable property or movables - any...

(personal possession) slavery, as opposed to dependent groups such as the penestae

Penestae

The penestae were a class of unfree labourers tied to the land once inhabiting Thessaly, whose status was comparable to that of the Spartan helots.-Status:...

of Thessaly

Thessaly

Thessaly is a traditional geographical region and an administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient region of the same name. Before the Greek Dark Ages, Thessaly was known as Aeolia, and appears thus in Homer's Odyssey....

or the Sparta

Sparta

Sparta or Lacedaemon, was a prominent city-state in ancient Greece, situated on the banks of the River Eurotas in Laconia, in south-eastern Peloponnese. It emerged as a political entity around the 10th century BC, when the invading Dorians subjugated the local, non-Dorian population. From c...

n helots

Helots

The helots: / Heílôtes) were an unfree population group that formed the main population of Laconia and the whole of Messenia . Their exact status was already disputed in antiquity: according to Critias, they were "especially slaves" whereas to Pollux, they occupied a status "between free men and...

, who were more like medieval serfs

Serfdom

Serfdom is the status of peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to Manorialism. It was a condition of bondage or modified slavery which developed primarily during the High Middle Ages in Europe and lasted to the mid-19th century...

(an enhancement to real estate). The chattel slave is an individual deprived of liberty and forced to submit to an owner who may buy, sell, or lease him or her like any other chattel.

The study of slavery in ancient Greece poses a number of significant methodological problems. Documentation is disjointed and very fragmented, focusing on the city of Athens. No treatise is specifically devoted to the subject. Judicial pleadings of the 4th century BC were interested in slavery only as a source of revenue. Comedy

Ancient Greek comedy

Ancient Greek comedy was one of the final three principal dramatic forms in the theatre of classical Greece . Athenian comedy is conventionally divided into three periods, Old Comedy, Middle Comedy, and New Comedy...

and tragedy represented stereotypes. Iconography made no substantial differentiation between slave and craftsman

Artisan

An artisan is a skilled manual worker who makes items that may be functional or strictly decorative, including furniture, clothing, jewellery, household items, and tools...

.

Terminology

Homer

In the Western classical tradition Homer , is the author of the Iliad and the Odyssey, and is revered as the greatest ancient Greek epic poet. These epics lie at the beginning of the Western canon of literature, and have had an enormous influence on the history of literature.When he lived is...

, Hesiod

Hesiod

Hesiod was a Greek oral poet generally thought by scholars to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer. His is the first European poetry in which the poet regards himself as a topic, an individual with a distinctive role to play. Ancient authors credited him and...

and Theognis of Megara

Theognis of Megara

Theognis of Megara was an ancient Greek poet active sometime in the sixth century BC. The work attributed to him consists of gnomic poetry quite typical of the time, featuring ethical maxims and practical advice about life...

, the slave was called / dmôs. The term has a general meaning but refers particularly to war prisoners taken as booty, in other words, property. During the classical period, the Greeks frequently used / andrápodon, literally, "one with the feet of a man", as opposed to / tetrapodon, "quadruped", or livestock. The most common word is / doûlos, an earlier form of which appears in Mycenaean

Mycenaean Greece

Mycenaean Greece was a cultural period of Bronze Age Greece taking its name from the archaeological site of Mycenae in northeastern Argolis, in the Peloponnese of southern Greece. Athens, Pylos, Thebes, and Tiryns are also important Mycenaean sites...

inscriptions as do-e-ro, used in opposition to "free man" ( / eleútheros). The verb

Verb

A verb, from the Latin verbum meaning word, is a word that in syntax conveys an action , or a state of being . In the usual description of English, the basic form, with or without the particle to, is the infinitive...

(which survives in modern Greek, meaning work) can be used metaphorically for other forms of dominion, as of one city over another or parents over their children. Finally, the term / oikétês was used, meaning "one who lives in house", referring to household servants.

Other terms used were less precise and required context:

- / therápôn – At the time of HomerHomerIn the Western classical tradition Homer , is the author of the Iliad and the Odyssey, and is revered as the greatest ancient Greek epic poet. These epics lie at the beginning of the Western canon of literature, and have had an enormous influence on the history of literature.When he lived is...

, the word meant "squire" (PatroclusPatroclusIn Greek mythology, as recorded in the Iliad by Homer, Patroclus, or Patroklos , was the son of Menoetius, grandson of Actor, King of Opus, and was Achilles' beloved comrade and brother-in-arms....

was referred to as the therapôn of AchillesAchillesIn Greek mythology, Achilles was a Greek hero of the Trojan War, the central character and the greatest warrior of Homer's Iliad.Plato named Achilles the handsomest of the heroes assembled against Troy....

and MerionesMeriones (mythology)In Greek mythology, Meriones was a son of Molus and Melphis. Molus was a half-brother of Idomeneus. Like other heroes of mythology, Meriones was said to be a descendant of gods. As a grandson of Deucalion , Meriones's ancestors include Zeus, Europa, Helios, and Circe. Meriones possessed the...

that of IdomeneusIdomeneusIn Greek mythology, Idomeneus , "strength of Ida") was a Cretan warrior, father of Orsilochus and Chalkiope, son of Deucalion, grandson of Minos and king of Crete. He led the Cretan armies to the Trojan War and was also one of Helen's suitors. Meriones was his charioteer and brother-in-arms...

); during the classical age, it meant "servant". - / akólouthos – literally, "the follower" or "the one who accompanies". Also, the diminutiveDiminutiveIn language structure, a diminutive, or diminutive form , is a formation of a word used to convey a slight degree of the root meaning, smallness of the object or quality named, encapsulation, intimacy, or endearment...

, used for pagePage (servant)A page or page boy is a traditionally young male servant, a messenger at the service of a nobleman or royal.-The medieval page:In medieval times, a page was an attendant to a knight; an apprentice squire...

boys. - / pais – literally "child", used in the same way as "houseboyHouseboyA Houseboy is typically a male servant or assistant who performs domestic or personal chores. Examples of its usage include:*An American slang term that originated in World War II for a native boy who helped a soldier perform basic responsibilities like cleaning, laundry, ironing, shoe-shining,...

", also used in a derogatory way to call adult slaves. - / sôma – literally "body", used in the context of emancipation.

Origins of slavery

Mycenaean Greece

Mycenaean Greece was a cultural period of Bronze Age Greece taking its name from the archaeological site of Mycenae in northeastern Argolis, in the Peloponnese of southern Greece. Athens, Pylos, Thebes, and Tiryns are also important Mycenaean sites...

. In the tablets from Pylos

Pylos

Pylos , historically known under its Italian name Navarino, is a town and a former municipality in Messenia, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Pylos-Nestoras, of which it is the seat and a municipal unit. It was the capital of the former...

140 do-e-ro can be identified with certainty. Two legal categories can be distinguished: "common" slaves and "slaves of the god" (te-o-jo do-e-ro / θεοιο), the God in this case probably being Poseidon

Poseidon

Poseidon was the god of the sea, and, as "Earth-Shaker," of the earthquakes in Greek mythology. The name of the sea-god Nethuns in Etruscan was adopted in Latin for Neptune in Roman mythology: both were sea gods analogous to Poseidon...

. Slaves of the god are always mentioned by name and own their own land; their legal status is close to that of freemen. The nature and origin of their bond to the divinity is unclear. The names of common slaves show that some of them came from Kythera

Kythira

Cythera is an island in Greece, once part of the Ionian Islands. It lies opposite the south-eastern tip of the Peloponnese peninsula. It is administratively part of the Islands regional unit, which is part of the Attica region , Greece.For many centuries, while naval travel was the only means...

, Chios

Chios

Chios is the fifth largest of the Greek islands, situated in the Aegean Sea, seven kilometres off the Asia Minor coast. The island is separated from Turkey by the Chios Strait. The island is noted for its strong merchant shipping community, its unique mastic gum and its medieval villages...

, Lemnos

Lemnos

Lemnos is an island of Greece in the northern part of the Aegean Sea. Administratively the island forms a separate municipality within the Lemnos peripheral unit, which is part of the North Aegean Periphery. The principal town of the island and seat of the municipality is Myrina...

or Halicarnassus

Halicarnassus

Halicarnassus was an ancient Greek city at the site of modern Bodrum in Turkey. It was located in southwest Caria on a picturesque, advantageous site on the Ceramic Gulf. The city was famous for the tomb of Mausolus, the origin of the word mausoleum, built between 353 BC and 350 BC, and...

, and were probably enslaved as a result of piracy

Piracy

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence at sea. The term can include acts committed on land, in the air, or in other major bodies of water or on a shore. It does not normally include crimes committed against persons traveling on the same vessel as the perpetrator...

. The tablets indicate that unions between slaves and non-slaves were not uncommon and that slaves could be independent artisans and retain plots of land. It appears that the major division in Mycenaean civilization was not between slave and free, but between those attached to the palace and those not.

There is no continuity between the Mycenaean era and the time of Homer

Homer

In the Western classical tradition Homer , is the author of the Iliad and the Odyssey, and is revered as the greatest ancient Greek epic poet. These epics lie at the beginning of the Western canon of literature, and have had an enormous influence on the history of literature.When he lived is...

, where social structures reflected those of the Greek dark ages

Greek Dark Ages

The Greek Dark Age or Ages also known as Geometric or Homeric Age are terms which have regularly been used to refer to the period of Greek history from the presumed Dorian invasion and end of the Mycenaean Palatial civilization around 1200 BC, to the first signs of the Greek city-states in the 9th...

. The terminology differs: the slave is no longer do-e-ro (doulos) but dmôs. In the Iliad

Iliad

The Iliad is an epic poem in dactylic hexameters, traditionally attributed to Homer. Set during the Trojan War, the ten-year siege of the city of Troy by a coalition of Greek states, it tells of the battles and events during the weeks of a quarrel between King Agamemnon and the warrior Achilles...

, slaves are mainly women taken as booty of war, while men were either ransomed or killed on the battlefield. In the Odyssey, the slaves also seem to be mostly women. These slaves were servants and sometimes concubines. There were some male slaves, especially in the Odyssey, a prime example being the swineherd Eumaeus. The slave was distinctive in being a member of the core part of the oikos ("family unit", "household"): Laertes

Laertes

In Greek mythology, Laërtes was the son of Arcesius and Chalcomedusa. He was the father of Odysseus and Ctimene by his wife Anticlea, daughter of the thief Autolycus. Laërtes was an Argonaut and participated in the hunt for the Calydonian Boar...

eats and drinks with his servants; in the winter, he sleeps in their company. The term dmôs is not considered pejorative, and Eumaeus

Eumaeus

In Greek mythology, Eumaeus was Odysseus's swineherd and friend before he left for the Trojan War. His father, Ktesios son of Ormenos, was king of an island called Syria. When he was a young child a Phoenician sailor seduced his nurse, a slave, who agreed to bring the child among other treasures...

, the "divine" swineherd, benefits from the same Homeric epithet

Epithets in Homer

A characteristic of Homer's style is the use of epithets, as in "rosy-fingered" dawn or "swift-footed" Achilles. Epithets are used because of the constraints of the dactylic hexameter and because of the oral transmission of the poems; they are mnemonic aids to the poet and the audience...

as the Greek heroes. In spite of this, slavery remained a disgrace. Eumaeus himself declares that “Zeus, of the far-borne voice, takes away the half of a man's virtue, when the day of slavery comes upon him.”

It is difficult to determine when slave trading began in the archaic period. In Works and Days

Works and Days

Works and Days is a didactic poem of some 800 verses written by the ancient Greek poet Hesiod around 700 BC. At its center, the Works and Days is a farmer's almanac in which Hesiod instructs his brother Perses in the agricultural arts...

(8th century BC), Hesiod

Hesiod

Hesiod was a Greek oral poet generally thought by scholars to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer. His is the first European poetry in which the poet regards himself as a topic, an individual with a distinctive role to play. Ancient authors credited him and...

owns numerous dmôes, although their status is unclear. The presence of douloi is confirmed by lyric poets such as Archilochus

Archilochus

Archilochus, or, Archilochos While these have been the generally accepted dates since Felix Jacoby, "The Date of Archilochus," Classical Quarterly 35 97-109, some scholars disagree; Robin Lane Fox, for instance, in Travelling Heroes: Greeks and Their Myths in the Epic Age of Homer , p...

or Theognis of Megara

Theognis of Megara

Theognis of Megara was an ancient Greek poet active sometime in the sixth century BC. The work attributed to him consists of gnomic poetry quite typical of the time, featuring ethical maxims and practical advice about life...

. According to epigraphic evidence, the homicide law of Draco (c. 620 BC) mentioned slaves. According to Plutarch, Solon

Solon

Solon was an Athenian statesman, lawmaker, and poet. He is remembered particularly for his efforts to legislate against political, economic and moral decline in archaic Athens...

(c. 594-593 BC) forbade slaves from practising gymnastics and pederasty. By the end of the period, references become more common. Slavery becomes prevalent at the very moment when Solon establishes the basis for Athenian democracy. Classical scholar Moses Finley likewise remarks that Chios, which, according to Theopompus

Theopompus

Theopompus was a Greek historian and rhetorician- Biography :Theopompus was born on Chios. In early youth he seems to have spent some time at Athens, along with his father, who had been exiled on account of his Laconian sympathies...

, was the first city to organize a slave trade, also enjoyed an early democratic process (in the 6th century BC). He concludes that “one aspect of Greek history, in short, is the advance hand in hand, of freedom and slavery.”

Economic role

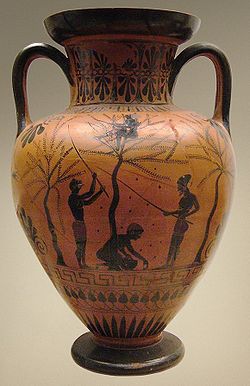

The principal use of slaves was in agriculture

Agriculture of Ancient Greece

Agriculture was the foundation of the Ancient Greek economy. Nearly 80% of the population was involved in this activity.- Environment :The Mediterranean climate is characterized by two seasons: the first dry and hot, from April to September ; the second is humid, and is marked by often violent rain...

, the foundation of the Greek economy. Some small landowners might own one slave, or even two. An abundant literature of manuals for landowners (such as the Economy of Xenophon

Xenophon

Xenophon , son of Gryllus, of the deme Erchia of Athens, also known as Xenophon of Athens, was a Greek historian, soldier, mercenary, philosopher and a contemporary and admirer of Socrates...

or that of Pseudo-Aristotle

Pseudo-Aristotle

Pseudo-Aristotle is a general cognomen for authors of philosophical or medical treatises who attributed their work to the Greek philosopher Aristotle, or whose work was later attributed to him by others....

) confirms the presence of dozens of slaves on the larger estates; they could be common labourers or foremen. The extent to which slaves were used as a labour force in farming is disputed. It is certain that rural slavery was very common in Athens, and that ancient Greece did not know of the immense slave populations found on the Roman latifundia

Latifundia

Latifundia are pieces of property covering very large land areas. The latifundia of Roman history were great landed estates, specializing in agriculture destined for export: grain, olive oil, or wine...

.

In mines

Mining

Mining is the extraction of valuable minerals or other geological materials from the earth, from an ore body, vein or seam. The term also includes the removal of soil. Materials recovered by mining include base metals, precious metals, iron, uranium, coal, diamonds, limestone, oil shale, rock...

and quarries

Quarry

A quarry is a type of open-pit mine from which rock or minerals are extracted. Quarries are generally used for extracting building materials, such as dimension stone, construction aggregate, riprap, sand, and gravel. They are often collocated with concrete and asphalt plants due to the requirement...

slave labour was prevalent, with found large slave populations often leased out by rich private citizens. The strategos

Strategos

Strategos, plural strategoi, is used in Greek to mean "general". In the Hellenistic and Byzantine Empires the term was also used to describe a military governor...

Nicias

Nicias

Nicias or Nikias was an Athenian politician and general during the period of the Peloponnesian War. Nicias was a member of the Athenian aristocracy because he had inherited a large fortune from his father, which was invested into the silver mines around Attica's Mt. Laurium...

leased a thousand slaves to the silver mines of Laurium

Laurium

Laurium or Lavrio is a town in southeastern part of Attica, Greece. It is the seat of the municipality of Lavreotiki...

in Attica

Attica

Attica is a historical region of Greece, containing Athens, the current capital of Greece. The historical region is centered on the Attic peninsula, which projects into the Aegean Sea...

; Hipponicos, 600; and Philomidès, 300. Xenophon indicates that they received one obolus

Obolus

The obol was an ancient silver coin. In Classical Athens, there were six obols to the drachma, lioterally "handful"; it could be excahnged for eight chalkoi...

per slave per day, amounting to 60 drachmas per year. This was one of the most prized investments for Athenians. The number of slaves working in the Laurium mines or in the mills processing ore has been estimated at 30,000. Xenophon suggested that the city buy a large number of slaves, up to three state slaves per citizen, so that their leasing would assure the upkeep of all the citizens.

Slaves were also used as craftsmen and tradespersons. As in agriculture, they were used for labour that was beyond the capability of the family. The slave population was greatest in workshops: the shield factory of Lysias

Lysias

Lysias was a logographer in Ancient Greece. He was one of the ten Attic orators included in the "Alexandrian Canon" compiled by Aristophanes of Byzantium and Aristarchus of Samothrace in the third century BC.-Life:According to Dionysius of Halicarnassus and the author of the life ascribed to...

employed 120 slaves, and the father of Demosthenes

Demosthenes

Demosthenes was a prominent Greek statesman and orator of ancient Athens. His orations constitute a significant expression of contemporary Athenian intellectual prowess and provide an insight into the politics and culture of ancient Greece during the 4th century BC. Demosthenes learned rhetoric by...

owned 32 cutlers and 20 bedmakers.

Slaves were also employed in the home. The domestic's main role was to stand in for his master at his trade and to accompany him on trips. In time of war he was batman to the hoplite

Hoplite

A hoplite was a citizen-soldier of the Ancient Greek city-states. Hoplites were primarily armed as spearmen and fought in a phalanx formation. The word "hoplite" derives from "hoplon" , the type of the shield used by the soldiers, although, as a word, "hopla" could also denote weapons held or even...

; it has been argued that their actual role was far greater. The female slave carried out domestic tasks, in particular bread baking and textile making. Only the poorest citizens did not possess a domestic slave.

Population

Thucydides

Thucydides was a Greek historian and author from Alimos. His History of the Peloponnesian War recounts the 5th century BC war between Sparta and Athens to the year 411 BC...

remarked on the desertion of 20,890 slaves during the war of Decelea

Decelea

Decelea , modern Dekeleia or Dekelia, Deceleia or Decelia, previous name Tatoi, was an ancient village in northern Attica serving as a trade route connecting Euboea with Athens, Greece. The historian Herodotus reports that its citizens enjoyed a special relationship with Sparta. The Spartans took...

, mostly tradesmen. The lowest estimate, of 20,000 slaves, during the time of Demosthenes

Demosthenes

Demosthenes was a prominent Greek statesman and orator of ancient Athens. His orations constitute a significant expression of contemporary Athenian intellectual prowess and provide an insight into the politics and culture of ancient Greece during the 4th century BC. Demosthenes learned rhetoric by...

, corresponds to one slave per family. Between 317 BC and 307 BC, the tyrant Demetrius Phalereus

Demetrius Phalereus

Demetrius of Phalerum was an Athenian orator originally from Phalerum, a student of Theophrastus and one of the first Peripatetics...

ordered a general census of Attica, which arrived at the following figures: 21,000 citizens, 10,000 metic

Metic

In ancient Greece, the term metic referred to a resident alien, one who did not have citizen rights in his or her Greek city-state of residence....

s and 400,000 slaves. The orator Hypereides

Hypereides

Hypereides or Hyperides was a logographer in Ancient Greece...

, in his Against Areistogiton, recalls that the effort to enlist 150,000 male slaves of military age led to the defeat of the Greeks at the Battle of Chaeronea (338 BC)

Battle of Chaeronea (338 BC)

The Battle of Chaeronea was fought in 338 BC, near the city of Chaeronea in Boeotia, between the forces of Philip II of Macedon and an alliance of Greek city-states...

, which corresponds to the figures of Ctesicles

Ctesicles

Ctesicles was the author of a chronological work , of which two fragments are preserved in Athenaeus.Ctesicles was also a sculptor, who made a statue at Samos and an Athenian general...

.

According to the literature, it appears that the majority of free Athenians owned at least one slave. Aristophanes

Aristophanes

Aristophanes , son of Philippus, of the deme Cydathenaus, was a comic playwright of ancient Athens. Eleven of his forty plays survive virtually complete...

, in Plutus

Plutus (play)

Plutus is an Ancient Greek comedy by the playwrightAristophanes, first produced c. 388 BC. A political satire on contemporary Athens, it features the personified god of wealth Plutus...

, portrays poor peasants who have several slaves; Aristotle defines a house as containing freemen and slaves. Conversely, not owning even one slave was a clear sign of poverty. In the celebrated discourse of Lysias

Lysias

Lysias was a logographer in Ancient Greece. He was one of the ten Attic orators included in the "Alexandrian Canon" compiled by Aristophanes of Byzantium and Aristarchus of Samothrace in the third century BC.-Life:According to Dionysius of Halicarnassus and the author of the life ascribed to...

For the Invalid, a cripple pleading for a pension explains "my income is very small and now I'm required to do these things myself and do not even have the means to purchase a slave who can do these things for me." However, the huge slave populations of the Romans were unknown in ancient Greece. When Athenaeus cites the case of Mnason, friend of Aristotle and owner of a thousand slaves, this appears to be exceptional. Plato

Plato

Plato , was a Classical Greek philosopher, mathematician, student of Socrates, writer of philosophical dialogues, and founder of the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. Along with his mentor, Socrates, and his student, Aristotle, Plato helped to lay the...

, owner of five slaves at the time of his death, describes the very rich as owning 50 slaves.

Thucydides estimates that the isle of Chios

Chios

Chios is the fifth largest of the Greek islands, situated in the Aegean Sea, seven kilometres off the Asia Minor coast. The island is separated from Turkey by the Chios Strait. The island is noted for its strong merchant shipping community, its unique mastic gum and its medieval villages...

had proportionally the largest number of slaves.

Sources of supply

There were four primary sources of slaves: war, in which the defeated would become slaves to the victorious unless a more objective outcome was reached; piracyPiracy

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence at sea. The term can include acts committed on land, in the air, or in other major bodies of water or on a shore. It does not normally include crimes committed against persons traveling on the same vessel as the perpetrator...

(at sea); banditry (on land); and international trade.

War

By the rules of war of the period, the victor possessed absolute rights over the vanquished, whether they were soldiers or not. Enslavement, while not systematic, was common practice. ThucydidesThucydides

Thucydides was a Greek historian and author from Alimos. His History of the Peloponnesian War recounts the 5th century BC war between Sparta and Athens to the year 411 BC...

recalls that 7,000 inhabitants of Hyccara in Sicily

Sicily

Sicily is a region of Italy, and is the largest island in the Mediterranean Sea. Along with the surrounding minor islands, it constitutes an autonomous region of Italy, the Regione Autonoma Siciliana Sicily has a rich and unique culture, especially with regard to the arts, music, literature,...

were taken prisoner by Nicias

Nicias

Nicias or Nikias was an Athenian politician and general during the period of the Peloponnesian War. Nicias was a member of the Athenian aristocracy because he had inherited a large fortune from his father, which was invested into the silver mines around Attica's Mt. Laurium...

and sold for 120 talents

Talent (weight)

The "talent" was one of several ancient units of mass, as well as corresponding units of value equivalent to these masses of a precious metal. It was approximately the mass of water required to fill an amphora. A Greek, or Attic talent, was , a Roman talent was , an Egyptian talent was , and a...

in the neighbouring village of Catania

Catania

Catania is an Italian city on the east coast of Sicily facing the Ionian Sea, between Messina and Syracuse. It is the capital of the homonymous province, and with 298,957 inhabitants it is the second-largest city in Sicily and the tenth in Italy.Catania is known to have a seismic history and...

. Likewise in 348 BC the population of Olynthus

Olynthus

Olynthus was an ancient city of Chalcidice, built mostly on two flat-topped hills 30–40m in height, in a fertile plain at the head of the Gulf of Torone, near the neck of the peninsula of Pallene, about 2.5 kilometers from the sea, and about 60 stadia Olynthus was an ancient city of...

was reduced to slavery, as was that of Thebes

Thebes, Greece

Thebes is a city in Greece, situated to the north of the Cithaeron range, which divides Boeotia from Attica, and on the southern edge of the Boeotian plain. It played an important role in Greek myth, as the site of the stories of Cadmus, Oedipus, Dionysus and others...

in 335 BC by Alexander the Great and that of Mantineia

Mantineia

Mantineia was a city in ancient Greece that was the site of two significant battles in Classical Greek history. It is also a former municipality in Arcadia, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Tripoli, of which it is a municipal unit. Its seat...

by the Achaean League

Achaean League

The Achaean League was a Hellenistic era confederation of Greek city states on the northern and central Peloponnese, which existed between 280 BC and 146 BC...

.

The existence of Greek slaves was a constant source of discomfort for free Greeks. The enslavement of cities was also a controversial practice. Some generals refused, such as the Sparta

Sparta

Sparta or Lacedaemon, was a prominent city-state in ancient Greece, situated on the banks of the River Eurotas in Laconia, in south-eastern Peloponnese. It emerged as a political entity around the 10th century BC, when the invading Dorians subjugated the local, non-Dorian population. From c...

ns Agesilaus II

Agesilaus II

Agesilaus II, or Agesilaos II was a king of Sparta, of the Eurypontid dynasty, ruling from approximately 400 BC to 360 BC, during most of which time he was, in Plutarch's words, "as good as thought commander and king of all Greece," and was for the whole of it greatly identified with his...

and Callicratidas

Callicratidas

Callicratidas was a Spartan naval commander in the Peloponnesian War. In 406 BC, he was sent to the Aegean to take command of the Spartan fleet from Lysander, the first navarch....

. Some cities passed accords to forbid the practice: in the middle of the 3rd century BC, Miletus

Miletus

Miletus was an ancient Greek city on the western coast of Anatolia , near the mouth of the Maeander River in ancient Caria...

agreed not to reduce any free Knossian

Knossos

Knossos , also known as Labyrinth, or Knossos Palace, is the largest Bronze Age archaeological site on Crete and probably the ceremonial and political centre of the Minoan civilization and culture. The palace appears as a maze of workrooms, living spaces, and store rooms close to a central square...

to slavery, and vice versa. Conversely, the emancipation by ransom of a city that had been entirely reduced to slavery carried great prestige: Cassander

Cassander

Cassander , King of Macedonia , was a son of Antipater, and founder of the Antipatrid dynasty...

, in 316 BC, restored Thebes. Before him, Philip II of Macedon

Philip II of Macedon

Philip II of Macedon "friend" + ἵππος "horse" — transliterated ; 382 – 336 BC), was a king of Macedon from 359 BC until his assassination in 336 BC. He was the father of Alexander the Great and Philip III.-Biography:...

enslaved and then emancipated Stageira

Stageira

Stageira was an ancient Greek city on the Chalkidiki peninsula and is chiefly known for being the birthplace of Aristotle. The city lies approximately 8 kilometres north northeast of the present-day village of Stagira, close to the town of Olympiada....

.

Piracy and banditry

PiracyPiracy

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence at sea. The term can include acts committed on land, in the air, or in other major bodies of water or on a shore. It does not normally include crimes committed against persons traveling on the same vessel as the perpetrator...

and banditry provided a significant and consistent supply of slaves, though the significance of this source varied according to era and region. Pirates and brigands would demand ransom whenever the status of their catch warranted it. Whenever ransom was not paid or not warranted, captives would be sold to a trafficker. In certain areas, piracy was practically a national specialty, described by Thucydides as "the old-fashioned" way of life. Such was the case in Acarnania

Acarnania

Acarnania is a region of west-central Greece that lies along the Ionian Sea, west of Aetolia, with the Achelous River for a boundary, and north of the gulf of Calydon, which is the entrance to the Gulf of Corinth. Today it forms the western part of the prefecture of Aetolia-Acarnania. The capital...

, Crete

Crete

Crete is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, and one of the thirteen administrative regions of Greece. It forms a significant part of the economy and cultural heritage of Greece while retaining its own local cultural traits...

, and Aetolia

Aetolia

Aetolia is a mountainous region of Greece on the north coast of the Gulf of Corinth, forming the eastern part of the modern prefecture of Aetolia-Acarnania.-Geography:...

. Outside of Greece, this was also the case with Illyria

Illyria

In classical antiquity, Illyria was a region in the western part of the Balkan Peninsula inhabited by the Illyrians....

ns, Phoenicia

Phoenicia

Phoenicia , was an ancient civilization in Canaan which covered most of the western, coastal part of the Fertile Crescent. Several major Phoenician cities were built on the coastline of the Mediterranean. It was an enterprising maritime trading culture that spread across the Mediterranean from 1550...

ns, and Etruscans

Etruscan civilization

Etruscan civilization is the modern English name given to a civilization of ancient Italy in the area corresponding roughly to Tuscany. The ancient Romans called its creators the Tusci or Etrusci...

. During the Hellenistic period

Hellenistic Greece

In the context of Ancient Greek art, architecture, and culture, Hellenistic Greece corresponds to the period between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the annexation of the classical Greek heartlands by Rome in 146 BC...

, Cilicia

Cilicia

In antiquity, Cilicia was the south coastal region of Asia Minor, south of the central Anatolian plateau. It existed as a political entity from Hittite times into the Byzantine empire...

ns and the mountain peoples from the coasts of Anatolia

Anatolia

Anatolia is a geographic and historical term denoting the westernmost protrusion of Asia, comprising the majority of the Republic of Turkey...

could also be added to the list. Strabo

Strabo

Strabo, also written Strabon was a Greek historian, geographer and philosopher.-Life:Strabo was born to an affluent family from Amaseia in Pontus , a city which he said was situated the approximate equivalent of 75 km from the Black Sea...

explains the popularity of the practice amongst the Cilicians by its profitability; Delos

Delos

The island of Delos , isolated in the centre of the roughly circular ring of islands called the Cyclades, near Mykonos, is one of the most important mythological, historical and archaeological sites in Greece...

, not far away, allowed for "moving a myriad of slaves daily". The growing influence of the Roman Republic

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic was the period of the ancient Roman civilization where the government operated as a republic. It began with the overthrow of the Roman monarchy, traditionally dated around 508 BC, and its replacement by a government headed by two consuls, elected annually by the citizens and...

, a large consumer of slaves, led to development of the market and an aggravation of piracy. In the 1st century BC, however, the Romans largely eradicated piracy to protect the Mediterranean trade routes.

Slave trade

There was slave trade between kingdoms and states of the wider region. The fragmentary list of slaves confiscated from the property of the mutilators of the HermaHerma

A Herma, commonly in English herm is a sculpture with a head, and perhaps a torso, above a plain, usually squared lower section, on which male genitals may also be carved at the appropriate height...

i mentions 32 slaves whose origin have been ascertained: 13 came from Thrace

Thrace

Thrace is a historical and geographic area in southeast Europe. As a geographical concept, Thrace designates a region bounded by the Balkan Mountains on the north, Rhodope Mountains and the Aegean Sea on the south, and by the Black Sea and the Sea of Marmara on the east...

, 7 from Caria

Caria

Caria was a region of western Anatolia extending along the coast from mid-Ionia south to Lycia and east to Phrygia. The Ionian and Dorian Greeks colonized the west of it and joined the Carian population in forming Greek-dominated states there...

, and the others came from Cappadocia

Cappadocia

Cappadocia is a historical region in Central Anatolia, largely in Nevşehir Province.In the time of Herodotus, the Cappadocians were reported as occupying the whole region from Mount Taurus to the vicinity of the Euxine...

, Caria

Caria

Caria was a region of western Anatolia extending along the coast from mid-Ionia south to Lycia and east to Phrygia. The Ionian and Dorian Greeks colonized the west of it and joined the Carian population in forming Greek-dominated states there...

, Scythia

Scythia

In antiquity, Scythian or Scyths were terms used by the Greeks to refer to certain Iranian groups of horse-riding nomadic pastoralists who dwelt on the Pontic-Caspian steppe...

, Phrygia

Phrygia

In antiquity, Phrygia was a kingdom in the west central part of Anatolia, in what is now modern-day Turkey. The Phrygians initially lived in the southern Balkans; according to Herodotus, under the name of Bryges , changing it to Phruges after their final migration to Anatolia, via the...

, Lydia

Lydia

Lydia was an Iron Age kingdom of western Asia Minor located generally east of ancient Ionia in the modern Turkish provinces of Manisa and inland İzmir. Its population spoke an Anatolian language known as Lydian....

, Syria

Syria

Syria , officially the Syrian Arab Republic , is a country in Western Asia, bordering Lebanon and the Mediterranean Sea to the West, Turkey to the north, Iraq to the east, Jordan to the south, and Israel to the southwest....

, Ilyria, Macedon

Macedon

Macedonia or Macedon was an ancient kingdom, centered in the northeastern part of the Greek peninsula, bordered by Epirus to the west, Paeonia to the north, the region of Thrace to the east and Thessaly to the south....

and Peloponnese

Peloponnese

The Peloponnese, Peloponnesos or Peloponnesus , is a large peninsula , located in a region of southern Greece, forming the part of the country south of the Gulf of Corinth...

. The mechanism was similar to that later seen in the African slave trade

African slave trade

Systems of servitude and slavery were common in many parts of Africa, as they were in much of the ancient world. In some African societies, the enslaved people were also indentured servants and fully integrated; in others, they were treated much worse...

: local professionals sold their own people to Greek slave merchants. The principal centres of the slave trade appear to have been Ephesus

Ephesus

Ephesus was an ancient Greek city, and later a major Roman city, on the west coast of Asia Minor, near present-day Selçuk, Izmir Province, Turkey. It was one of the twelve cities of the Ionian League during the Classical Greek era...

, Byzantium

Byzantium

Byzantium was an ancient Greek city, founded by Greek colonists from Megara in 667 BC and named after their king Byzas . The name Byzantium is a Latinization of the original name Byzantion...

, and even faraway Tanais

Tanais

Tanais is the ancient name for the River Don in Russia. Strabo regarded it as the boundary between Europe and Asia.In antiquity, Tanais was also the name of a city in the Don river delta that reaches into the northeasternmost part of the Sea of Azov, which the Greeks called Lake Maeotis...

at the mouth of the Don. Some 'barbarian' slaves were victims of war or localised piracy, but others were sold by their parents. There is a lack of direct evidence of slave traffic, but corroborating evidence exists. Firstly, certain nationalities are consistently and significantly represented in the slave population, such as the corps of Scythian archers employed by Athens as a police force—originally 300, but eventually nearly a thousand. Secondly, the names given to slaves in the comedies

Ancient Greek comedy

Ancient Greek comedy was one of the final three principal dramatic forms in the theatre of classical Greece . Athenian comedy is conventionally divided into three periods, Old Comedy, Middle Comedy, and New Comedy...

often had a geographical link; thus Thratta, used by Aristophanes

Aristophanes

Aristophanes , son of Philippus, of the deme Cydathenaus, was a comic playwright of ancient Athens. Eleven of his forty plays survive virtually complete...

in The Wasps

The Wasps

The Wasps is the fourth in chronological order of the eleven surviving plays by Aristophanes, the master of an ancient genre of drama called 'Old Comedy'. It was produced at the Lenaia festival in 422 BC, a time when Athens was enjoying a brief respite from The Peloponnesian War following a one...

, The Acharnians

The Acharnians

The Acharnians is the third play - and the earliest of the eleven surviving plays - by the great Athenian playwright Aristophanes. It was produced in 425 BCE on behalf of the young dramatist by an associate, Callistratus, and it won first place at the Lenaia festival...

, and Peace

Peace (play)

Peace is an Athenian Old Comedy written and produced by the Greek playwright Aristophanes. It won second prize at the City Dionysia where it was staged just a few days before the ratification of the Peace of Nicias , which promised to end the ten year old Peloponnesian War...

, simply signified Thracian woman. Finally, the nationality of a slave was a significant criterion for major purchasers; the ancient advice was not to concentrate too many slaves of the same origin in the same place, in order to limit the risk of revolt. It is also probable that, as with the Romans, certain nationalities were considered more productive as slaves than others.

The price of slaves varied in accordance with their ability. Xenophon valued a Laurion miner at 180 drachmas; while a workman at major works was paid one drachma per day. Demosthenes' father's cutlers were valued at 500 to 600 drachmas each. Price was also a function of the quantity of slaves available; in the 4th century BC they were abundant and it was thus a buyer's market. A tax on sale revenues was levied by the market cities. For instance a large slave market was organized during the festivities at the temple of Apollo

Apollo

Apollo is one of the most important and complex of the Olympian deities in Greek and Roman mythology...

at Actium

Actium

Actium was the ancient name of a promontory of western Greece in northwestern Acarnania, at the mouth of the Sinus Ambracius opposite Nicopolis, built by Augustus on the north side of the strait....

. The Acarnanian League, which was in charge of the logistics, received half of the tax proceeds, the other half going to the city of Anactorion, of which Actium was a part. Buyers enjoyed a guarantee against latent defect

Latent defect

In the law of the sale of property a latent defect is a fault in the property that could not have been discovered by a reasonably thorough inspection before the sale....

s; the transaction could be invalidated if the bought slave turned out to be crippled and the buyer had not been warned about it.

Natural growth

Ptolemaic Egypt

Ptolemaic Egypt began when Ptolemy I Soter invaded Egypt and declared himself Pharaoh of Egypt in 305 BC and ended with the death of queen Cleopatra VII of Egypt and the Roman conquest in 30 BC. The Ptolemaic Kingdom was a powerful Hellenistic state, extending from southern Syria in the east, to...

and in manumission inscriptions at Delphi. Sometimes the cause of this was natural; mines, for instance, were exclusively a male domain. On the other hand, there were many female domestic slaves. The example of black people in the American South

Southern United States

The Southern United States—commonly referred to as the American South, Dixie, or simply the South—constitutes a large distinctive area in the southeastern and south-central United States...

on the other hand demonstrates that slave populations can multiply. This incongruity remains relatively unexplained.

Xenophon advised that male and female slaves should be lodged separately, that "…nor children born and bred by our domestics without our knowledge and consent—no unimportant matter, since, if the act of rearing children tends to make good servants still more loyally disposed, cohabiting but sharpens ingenuity for mischief in the bad." The explanation is perhaps economic; even a skilled slave was cheap, so it may have been cheaper to purchase a slave than to raise one. Additionally, childbirth placed the slave-mother's life at risk, and the baby was not guaranteed to survive to adulthood.

Houseborn slaves (oikogeneis) often constituted a privileged class. They were, for example, entrusted to take the children to school; they were "pedagogues

Pedagogy

Pedagogy is the study of being a teacher or the process of teaching. The term generally refers to strategies of instruction, or a style of instruction....

" in the first sense of the term. Some of them were the offspring of the master of the house, but in most cities, notably Athens, a child inherited the status of its mother.

Status of slaves

The Greeks had many degrees of enslavement. There was a multitude of categories, ranging from free citizen to chattel slave, and including PenestaePenestae

The penestae were a class of unfree labourers tied to the land once inhabiting Thessaly, whose status was comparable to that of the Spartan helots.-Status:...

or helots

Helots

The helots: / Heílôtes) were an unfree population group that formed the main population of Laconia and the whole of Messenia . Their exact status was already disputed in antiquity: according to Critias, they were "especially slaves" whereas to Pollux, they occupied a status "between free men and...

, disenfranchised citizens, freedmen, bastards, and metic

Metic

In ancient Greece, the term metic referred to a resident alien, one who did not have citizen rights in his or her Greek city-state of residence....

s. The common ground was the deprivation of civic rights.

Moses Finley proposed a set of criteria for different degrees of enslavement:

- Right to own property

- Authority over the work of another

- Power of punishment over another

- Legal rights and duties (liability to arrest and/or arbitrary punishment, or to litigate)

- Familial rights and privileges (marriage, inheritance, etc.)

- Possibility of social mobility (manumission or emancipation, access to citizen rights)

- Religious rights and obligations

- Military rights and obligations (military service as servant, heavy or light soldier, or sailor)

Athenian slaves

Themistocles

Themistocles ; c. 524–459 BC, was an Athenian politician and a general. He was one of a new breed of politicians who rose to prominence in the early years of the Athenian democracy, along with his great rival Aristides...

's Persian slave Sicinnus

Sicinnus

Sicinnus , a Persian according to Plutarch, was a slave of the Athenian leader Themistocles and pedagogue to his children. He is known for his actions as a negotiator between Themistocles and the Persian ruler Xerxes I during the Second Persian invasion of Greece...

(the counterpart of Ephialtes of Trachis), who, despite his Persian origin, betrayed Xerxes

Xerxes I of Persia

Xerxes I of Persia , Ḫšayāršā, ), also known as Xerxes the Great, was the fifth king of kings of the Achaemenid Empire.-Youth and rise to power:...

and helped Athenians in the Battle of Salamis

Battle of Salamis

The Battle of Salamis was fought between an Alliance of Greek city-states and the Persian Empire in September 480 BCE, in the straits between the mainland and Salamis, an island in the Saronic Gulf near Athens...

. Despite torture in trials, the Athenian slave was protected in an indirect way: if he was mistreated, the master could initiate litigation for damages and interest ( / dikê blabês). Conversely, a master who excessively mistreated a slave could be prosecuted by any citizen ( / graphê hybreôs); this was not enacted for the sake of the slave, but to avoid violent excess ( / hubris

Hubris

Hubris , also hybris, means extreme haughtiness, pride or arrogance. Hubris often indicates a loss of contact with reality and an overestimation of one's own competence or capabilities, especially when the person exhibiting it is in a position of power....

).

Isocrates

Isocrates

Isocrates , an ancient Greek rhetorician, was one of the ten Attic orators. In his time, he was probably the most influential rhetorician in Greece and made many contributions to rhetoric and education through his teaching and written works....

claimed that “not even the most worthless slave can be put to death without trial”; the master's power over his slave was not absolute, as it was under Roman law. Draco's law apparently punished with death the murder of a slave; the underlying principle was: “was the crime such that, if it became more widespread, it would do serious harm to society?” The suit that could be brought against a slave's killer was not a suit for damages, as would be the case for the killing of cattle, but a (dikê phonikê), demanding punishment for the religious pollution brought by the shedding of blood. In the 4th century BC, the suspect was judged by the Palladion, a court which had jurisdiction over unintentional homicide; the imposed penalty seems to have been more than a fine but less than death—maybe exile, as was the case in the murder of a Metic.

However, slaves did belong to their master's household. A newly-bought slave was welcomed with nuts and fruits, just like a newly-wed wife. Slaves took part in most of the civic and family cults; they were expressly invited to join the banquet of the Choes, second day of the Anthesteria

Anthesteria

Anthesteria, one of the four Athenian festivals in honour of Dionysus , was held annually for three days, the eleventh to thirteenth of the month of Anthesterion ; it was preceded by the Lenaia...

, and were allowed initiation into the Eleusinian Mysteries

Eleusinian Mysteries

The Eleusinian Mysteries were initiation ceremonies held every year for the cult of Demeter and Persephone based at Eleusis in ancient Greece. Of all the mysteries celebrated in ancient times, these were held to be the ones of greatest importance...

. A slave could claim asylum in a temple or at an altar, just like a free man. The slaves shared the gods of their masters and could keep their own religious customs if any.

Slaves could not own property, but their masters often let them save up to purchase their freedom, and records survive of slaves operating businesses by themselves, making only a fixed tax-payment to their masters. Athens also had a law forbidding the striking of slaves: if a person struck what appeared to be a slave in Athens, that person might find himself hitting a fellow-citizen, because many citizens dressed no better. It astonished other Greeks that Athenians tolerated back-chat from slaves. Athenian slaves fought together with Athenian freemen at the battle of Marathon

Battle of Marathon

The Battle of Marathon took place in 490 BC, during the first Persian invasion of Greece. It was fought between the citizens of Athens, aided by Plataea, and a Persian force commanded by Datis and Artaphernes. It was the culmination of the first attempt by Persia, under King Darius I, to subjugate...

, and the monuments memorialize them. It was formally decreed before the battle of Salamis

Battle of Salamis

The Battle of Salamis was fought between an Alliance of Greek city-states and the Persian Empire in September 480 BCE, in the straits between the mainland and Salamis, an island in the Saronic Gulf near Athens...

that the citizens should "save themselves, their women, children, and slaves".

Slaves had special sexual restrictions and obligations. For example, a slave could not engage free boys in pederastic

Pederasty in ancient Greece

Pederasty in ancient Greece was a socially acknowledged relationship between an adult and a younger male usually in his teens. It was characteristic of the Archaic and Classical periods...

relationships ("A slave shall not be the lover of a free boy nor follow after him, or else he shall receive fifty blows of the public lash."), and they were forbidden from the palaestra

Palaestra

The palaestra was the ancient Greek wrestling school. The events that did not require a lot of space, such as boxing and wrestling, were practised there...

e ("A slave shall not take exercise or anoint himself in the wrestling-schools."). Both laws are attributed to Solon. Fathers wanting to protect their sons from unwanted advances provided them with a slave guard, called a pedagogos, to escort the boy in his travels.

The sons of vanquished foes would be enslaved and often forced to work in male brothels, as in the case of Phaedo of Elis

Phaedo of Elis

Phaedo of Elis was a Greek philosopher. A native of Elis, he was captured in war and sold into slavery. He subsequently came into contact with Socrates at Athens who warmly received him and had him freed. He was present at the death of Socrates, and Plato named one of his dialogues Phaedo...

, who at the request of Socrates

Socrates

Socrates was a classical Greek Athenian philosopher. Credited as one of the founders of Western philosophy, he is an enigmatic figure known chiefly through the accounts of later classical writers, especially the writings of his students Plato and Xenophon, and the plays of his contemporary ...

was bought and freed from such an enterprise by the philosopher's rich friends. The rape of slaves was against the law, just as with citizens.

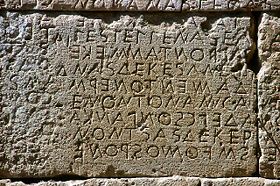

Slaves in Gortyn

Gortyn

Gortyn, Gortys or Gortyna is a municipality and an archaeological site on the Mediterranean island of Crete, 45 km away from the modern capital Heraklion. The seat of the municipality is the village Agioi Deka...

, in Crete, according to a code

Gortyn code

The Gortyn code was a legal code that was the codification of the civil law of the ancient Greek city-state of Gortyn in southern Crete.- History :...

engraved in stone dating to the 6th century BC, slaves (doulos or oikeus) found themselves in a state of great dependence. Their children belonged to the master. The master was responsible for all their offences, and, inversely, he received amends for crimes committed against his slaves by others. In the Gortyn code, where all punishment was monetary, fines were doubled for slaves committing a misdemeanour or felony. Conversely, an offence committed against a slave was much less expensive than an offence committed against a free person. As an example, the rape of a free woman by a slave was punishable by a fine of 200 stater

Stater

The stater was an ancient coin used in various regions of Greece.-History:The stater is mostly of Macedonian origin. Celtic tribes brought it in to Europe after using it as mercenaries in north Greece. It circulated from the 8th century BC to 50 AD...

s (400 drachms), while the rape of a non-virgin slave by another slave brought a fine of only one obolus (a sixth of a drachm).

Slaves did have the right to possess a house and livestock, which could be transmitted to descendants, as could clothing and household furnishings. Their family was recognized by law: they could marry, divorce, write a testament and inherit just like free men.

A specific case: debt slavery

Prior to its interdiction by SolonSolon

Solon was an Athenian statesman, lawmaker, and poet. He is remembered particularly for his efforts to legislate against political, economic and moral decline in archaic Athens...

, Athenians practiced debt enslavement: a citizen incapable of paying his debts became "enslaved" to the creditor. The exact nature of this dependency is a much controversial issue amongst modern historians: was it truly slavery or another form of bondage? However, this issue primarily concerned those peasants known as "hektēmoroi" working leased land belonging to rich landowners and unable to pay their rents. In theory, those so enslaved would be liberated when their original debts were repaid. The system was developed with variants throughout the Near East

Near East

The Near East is a geographical term that covers different countries for geographers, archeologists, and historians, on the one hand, and for political scientists, economists, and journalists, on the other...

and is cited in the Bible

Bible

The Bible refers to any one of the collections of the primary religious texts of Judaism and Christianity. There is no common version of the Bible, as the individual books , their contents and their order vary among denominations...

.

Solon put an end to it with the / seisachtheia

Seisachtheia

Seisachtheia was a set of laws instituted by the Athenian lawmaker Solon in order to rectify the widespread serfdom and slaves that had run rampant in Athens by the 6th century BC, by debit relief...

, liberation of debts, which prevented all claim to the person by the debtor and forbade the sale of free Athenians, including by themselves. Aristotle

Aristotle

Aristotle was a Greek philosopher and polymath, a student of Plato and teacher of Alexander the Great. His writings cover many subjects, including physics, metaphysics, poetry, theater, music, logic, rhetoric, linguistics, politics, government, ethics, biology, and zoology...

in his Constitution of the Athenians

Constitution of the Athenians

The Constitution of the Athenians is the name of either of two texts from Classical antiquity, one probably by Aristotle or a student of his, the other attributed to Xenophon, but not by him....

quotes one of Solon's poems:

And many a man whom fraud or law had sold

Far from his god-built land, an outcast slave,

I brought again to Athens; yea, and some,

Exiles from home through debt’s oppressive load,

Speaking no more the dear Athenian tongue,

But wandering far and wide, I brought again;

And those that here in vilest slavery (douleia)

Crouched ‘neath a master’s (despōtes) frown, I set them free.

Though much of Solon's vocabulary is that of "traditional" slavery, servitude for debt was at least different in that the enslaved Athenian remained an Athenian, dependent on another Athenian, in his place of birth. It is this aspect which explains the great wave of discontent with slavery of the 6th century BC, which was not intended to free all slaves but only those enslaved by debt. The reforms of Solon left two exceptions: the guardian of an unmarried woman who had lost her virginity had the right to sell her as a slave, and a citizen could “expose” (abandon) unwanted newborn children.

Manumission

The practice of manumissionManumission

Manumission is the act of a slave owner freeing his or her slaves. In the United States before the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which abolished most slavery, this often happened upon the death of the owner, under conditions in his will.-Motivations:The...

is confirmed to have existed in Chios

Chios

Chios is the fifth largest of the Greek islands, situated in the Aegean Sea, seven kilometres off the Asia Minor coast. The island is separated from Turkey by the Chios Strait. The island is noted for its strong merchant shipping community, its unique mastic gum and its medieval villages...

from the 6th century BC. It probably dates back to an earlier period, as it was an oral procedure. Informal emancipations are also confirmed in the classical period. It was sufficient to have witnesses, who would escort the citizen to a public emancipation of his slave, either at the theatre or before a public tribunal. This practice was outlawed in Athens in the middle of the 6th century BC in order to avoid public disorder.

The practice became more common in the 4th century BC and gave rise to inscriptions in stone which have been recovered from shrines such as Delphi

Delphi

Delphi is both an archaeological site and a modern town in Greece on the south-western spur of Mount Parnassus in the valley of Phocis.In Greek mythology, Delphi was the site of the Delphic oracle, the most important oracle in the classical Greek world, and a major site for the worship of the god...

and Dodona

Dodona

Dodona in Epirus in northwestern Greece, was an oracle devoted to a Mother Goddess identified at other sites with Rhea or Gaia, but here called Dione, who was joined and partly supplanted in historical times by the Greek god Zeus.The shrine of Dodona was regarded as the oldest Hellenic oracle,...

. They primarily date to the 2nd and 1st centuries BC, and the 1st century AD. Collective manumission was possible; an example is known from the 2nd century BC in the island of Thasos

Thasos

Thasos or Thassos is a Greek island in the northern Aegean Sea, close to the coast of Thrace and the plain of the river Nestos but geographically part of Macedonia. It is the northernmost Greek island, and 12th largest by area...

. It probably took place during a period of war as a reward for the slaves' loyalty, but in most cases the documentation deals with a voluntary act on the part of the master (predominantly male, but in the Hellenistic period also female).

The slave was often required to pay for himself an amount at least equivalent to his street value. To do this he could use his savings or take a loan ( / eranos) from his master, a friend, or a client, which last was often the case for a courtesan, one of the most famous examples of which involved the hetaera

Hetaera

In ancient Greece, hetaerae were courtesans, that is to say, highly educated, sophisticated companions...

Neaira

Neaira (hetaera)

Neaira, or Neaera, was a hetaera who lived in the 4th century BC in ancient Greece; there is no reliable data about the exact dates of her birth and death...

.

Emancipation was often of a religious nature, where the slave was considered to be "sold" to a deity, often Delphian Apollo

Apollo

Apollo is one of the most important and complex of the Olympian deities in Greek and Roman mythology...

, or was consecrated after his emancipation. The temple would receive a portion of the monetary transaction and would guarantee the contract. The manumission could also be entirely civil, in which case the magistrate played the role of the deity.

The slave's freedom could be either total or partial, at the master's whim. In the former, the emancipated slave was legally protected against all attempts at re-enslavement—for instance, on the part of the former master's inheritors. In the latter case, the emancipated slave could be liable to a number of obligations to the former master. The most restrictive contract was the paramone, a type of enslavement of limited duration during which time the master retained practically absolute rights.

In regard to the city, the emancipated slave was far from equal to a citizen by birth. He was liable to all types of obligations, as one can see from the proposals of Plato

Plato

Plato , was a Classical Greek philosopher, mathematician, student of Socrates, writer of philosophical dialogues, and founder of the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. Along with his mentor, Socrates, and his student, Aristotle, Plato helped to lay the...

in The Laws: presentation three times monthly at the home of the former master, forbidden to become richer than him, etc. In fact, the status of emancipated slaves was similar to that of metic

Metic

In ancient Greece, the term metic referred to a resident alien, one who did not have citizen rights in his or her Greek city-state of residence....

s, the residing foreigners, who were free but did not enjoy a citizen's rights.

Spartan slaves

SpartaSparta

Sparta or Lacedaemon, was a prominent city-state in ancient Greece, situated on the banks of the River Eurotas in Laconia, in south-eastern Peloponnese. It emerged as a political entity around the 10th century BC, when the invading Dorians subjugated the local, non-Dorian population. From c...

n citizens used helots, a dependent group collectively owned by the state. It is uncertain whether they had chattel slaves as well. There are mentions of people manumitted by Spartans, which was supposedly forbidden for helots, or sold outside of Lakonia: the poet Alcman

Alcman

Alcman was an Ancient Greek choral lyric poet from Sparta. He is the earliest representative of the Alexandrinian canon of the nine lyric poets.- Family :...

; a Philoxenos from Cytherea, reputedly enslaved with all his fellow citizens when his city was conquered, later sold to an Athenian; a Spartan cook bought by Dionysius the Elder or by a king of Pontus

Pontus

Pontus or Pontos is a historical Greek designation for a region on the southern coast of the Black Sea, located in modern-day northeastern Turkey. The name was applied to the coastal region in antiquity by the Greeks who colonized the area, and derived from the Greek name of the Black Sea: Πόντος...

, both versions being mentioned by Plutarch; and the famous Spartan nurses, much appreciated by Athenian parents.

Some texts mention both slaves and helots, which seems to indicate that they were not the same thing. Plato

Plato

Plato , was a Classical Greek philosopher, mathematician, student of Socrates, writer of philosophical dialogues, and founder of the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. Along with his mentor, Socrates, and his student, Aristotle, Plato helped to lay the...

in Alcibiades I cites "the ownership of slaves, and notably helots" amongst the Spartan riches, and Plutarch writes about "slaves and helots". Finally, according to Thucydides, the agreement that ended the 464 BC revolt of helots stated that any Messenian rebel who might hereafter be found within the Peloponnese

Peloponnese

The Peloponnese, Peloponnesos or Peloponnesus , is a large peninsula , located in a region of southern Greece, forming the part of the country south of the Gulf of Corinth...

was "to be the slave of his captor", which means that the ownership of chattel slaves was not illegal at that time.

Most historians thus concur that chattel slaves were indeed used in Sparta, at least after the Lacedemonian victory of 404 BC against Athens, but not in great numbers and only amongst the upper classes. As was in the other Greek cities, chattel slaves could be purchased at the market or taken in war.

Slavery conditions

Aristotle

Aristotle was a Greek philosopher and polymath, a student of Plato and teacher of Alexander the Great. His writings cover many subjects, including physics, metaphysics, poetry, theater, music, logic, rhetoric, linguistics, politics, government, ethics, biology, and zoology...

, the daily routine of slaves could be summed up in three words: "work, discipline, and feeding". Xenophon's advice is to treat slaves as domestic animals, that is to say punish disobedience and reward good behaviour. For his part, Aristotle prefers to see slaves treated as children and to use not only orders but also recommendations, as the slave is capable of understanding reasons when they are explained.

Greek literature abounds with scenes of slaves being flogged; it was a means of forcing them to work, as were control of rations, clothing, and rest. This violence could be meted out by the master or the supervisor, who was possibly also a slave. Thus, at the beginning of Aristophanes

Aristophanes

Aristophanes , son of Philippus, of the deme Cydathenaus, was a comic playwright of ancient Athens. Eleven of his forty plays survive virtually complete...

' The Knights

The Knights

The Knights was the fourth play written by Aristophanes, the master of an ancient form of drama known as Old Comedy. The play is a satire on the social and political life of classical Athens during the Peloponnesian War and in this respect it is typical of all the dramatist's early plays...

(4–5), two slaves complain of being "bruised and thrashed without respite" by their new supervisor. However, Aristophanes himself cites what is a typical old saw in ancient Greek comedy

Ancient Greek comedy

Ancient Greek comedy was one of the final three principal dramatic forms in the theatre of classical Greece . Athenian comedy is conventionally divided into three periods, Old Comedy, Middle Comedy, and New Comedy...

:

"He also dismissed those slaves who kept on running off, or deceiving someone, or getting whipped. They were always led out crying, so one of their fellow slaves could mock the bruises and ask then: 'Oh you poor miserable fellow, what's happened to your skin? Surely a huge army of lashes from a whip has fallen down on you and laid waste your back?'"

The condition of slaves varied very much according to their status; the mine slaves of Laureion and the pornai

Prostitution in Ancient Greece

Prostitution was a common aspect of ancient Greece. In the more important cities, and particularly the many ports, it employed a significant number of people and represented a notable part of economic activity...

(brothel prostitutes) lived a particularly brutal existence, while public slaves, craftsmen, tradesmen and bankers enjoyed relative independence. In return for a fee ( / apophora) paid to their master, they could live and work alone. They could thus earn some money on the side, sometimes enough to purchase their freedom. Potential emancipation was indeed a powerful motivator, though the real scale of this is difficult to estimate.

Ancient writers considered that Attic slaves enjoyed a “peculiarly happy lot”: Xenophon

Xenophon

Xenophon , son of Gryllus, of the deme Erchia of Athens, also known as Xenophon of Athens, was a Greek historian, soldier, mercenary, philosopher and a contemporary and admirer of Socrates...

deplores the liberties taken by Athenian slaves: "as for the slaves and Metics of Athens, they take the greatest licence; you cannot just strike them, and they do not step aside to give you free passage". This alleged good treatment did not prevent 20,000 Athenian slaves from running away at the end of the Peloponnesian War

Peloponnesian War

The Peloponnesian War, 431 to 404 BC, was an ancient Greek war fought by Athens and its empire against the Peloponnesian League led by Sparta. Historians have traditionally divided the war into three phases...

at the incitement of the Spartan garrison at Attica

Attica

Attica is a historical region of Greece, containing Athens, the current capital of Greece. The historical region is centered on the Attic peninsula, which projects into the Aegean Sea...

in Decelea

Decelea

Decelea , modern Dekeleia or Dekelia, Deceleia or Decelia, previous name Tatoi, was an ancient village in northern Attica serving as a trade route connecting Euboea with Athens, Greece. The historian Herodotus reports that its citizens enjoyed a special relationship with Sparta. The Spartans took...

. These were principally skilled artisans (kheirotekhnai), probably amongst the better-treated slaves. The title of a 4th-century comedy by Antiphanes, The Runaway-catcher , suggests that slave flight was not uncommon.

Conversely, the absence of a large-scale Greek slave revolt comparable to that of Spartacus

Spartacus

Spartacus was a famous leader of the slaves in the Third Servile War, a major slave uprising against the Roman Republic. Little is known about Spartacus beyond the events of the war, and surviving historical accounts are sometimes contradictory and may not always be reliable...

in Rome

Rome

Rome is the capital of Italy and the country's largest and most populated city and comune, with over 2.7 million residents in . The city is located in the central-western portion of the Italian Peninsula, on the Tiber River within the Lazio region of Italy.Rome's history spans two and a half...

, for instance, can probably be explained by the relative dispersion of Greek slaves, which would have prevented any large-scale planning. Slave revolts were rare, even in Rome or the American South. Individual acts of rebellion of slaves against their master, even if scarce, are not unheard of; a judicial speech mentions the attempted murder of his master by a boy slave, not 12 years old.

Historical views

Homer

In the Western classical tradition Homer , is the author of the Iliad and the Odyssey, and is revered as the greatest ancient Greek epic poet. These epics lie at the beginning of the Western canon of literature, and have had an enormous influence on the history of literature.When he lived is...

and the pre-classical authors, slavery was an inevitable consequence of war. Heraclitus

Heraclitus

Heraclitus of Ephesus was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher, a native of the Greek city Ephesus, Ionia, on the coast of Asia Minor. He was of distinguished parentage. Little is known about his early life and education, but he regarded himself as self-taught and a pioneer of wisdom...

states that "War is the father of all, the king of all ... he turns some into slaves and sets others free".

During the classical period, the main justification for slavery was economic. From a moral point of view, the idea of "natural" slavery emerged at the same time; thus, as Aeschylus

Aeschylus

Aeschylus was the first of the three ancient Greek tragedians whose work has survived, the others being Sophocles and Euripides, and is often described as the father of tragedy. His name derives from the Greek word aiskhos , meaning "shame"...

states in The Persians

The Persians