Capitol Reef National Park

Encyclopedia

Capitol Reef National Park is a United States National Park, in south-central Utah

. It is 100 miles (160 km) long but fairly narrow. The park, established in 1971, preserves 378 mi² (979 km²) and is open all year, although May through September are the most popular months.

Called "Wayne Wonderland" in the 1920s by local boosters

Ephraim P. Pectol and Joseph S. Hickman, Capitol Reef National Park protects colorful canyons, ridges, butte

s, and monoliths. About 75 miles (120 km) of the long up-thrust called the Waterpocket Fold

, a rugged spine extending from Thousand Lake Mountain

to Lake Powell

, is preserved within the park. "Capitol Reef" is the name of an especially rugged and spectacular segment of the Waterpocket Fold

near the Fremont River. The area was named for a line of white dome

s and cliffs of Navajo Sandstone, each of which looks somewhat like the United States Capitol

building, that run from the Fremont River

to Pleasant Creek on the Waterpocket Fold. The local word reef referred to any rocky barrier to travel. Easy road access came with the construction in 1962 of State Route 24

through the Fremont River Canyon.

Capitol Reef encompasses the Waterpocket Fold

Capitol Reef encompasses the Waterpocket Fold

, a warp in the earth's crust that is 65 million years old. In this fold, newer and older layers of earth folded over each other in an S-shape. This warp, probably caused by the same colliding continental plates

that created the Rocky Mountains

, has weathered and eroded

over millennia to expose layers of rock and fossil

s. The park is filled with brilliantly colored sandstone

cliffs, gleaming white domes, and contrasting layers of stone and earth.

The area was named for a line of white dome

s and cliffs of Navajo Sandstone, each of which looks somewhat like the United States Capitol

building, that run from the Fremont River

to Pleasant Creek on the Waterpocket Fold.

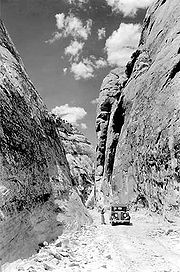

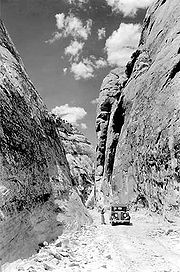

The fold forms a north-to-south barrier that even today has barely been breached by roads. Early settlers referred to parallel, impassable ridges as "reefs", from which the park gets the second half of its name. The first paved road was constructed through the area in 1962. Today, State Route 24

cuts through the park traveling east and west between Canyonlands National Park

and Bryce Canyon National Park

, but few other paved roads invade the rugged landscape.

The park is filled with canyons, cliffs, towers, domes, and arches. The Fremont River has cut canyons through parts of the Waterpocket Fold, but most of the park is arid desert country. A scenic drive shows park visitors some of the highlights, but it runs only a few miles from the main highway. Hundreds of miles of trails and unpaved roads lead the more adventurous into the equally scenic backcountry.

crops of lentil

s, maize, and squash

and stored their grain

in stone granaries (in part made from the numerous black basalt

boulders that litter the area). In the 13th century, all of the Native American cultures in this area underwent sudden change, likely due to a long drought. The Fremont settlements and fields were abandoned.

Many years after the Fremont left, Paiute

s moved into the area. These Numic

speaking people named the Fremont granaries moki huts and thought they were the homes of a race of tiny people or moki.

In 1872 Alan H. Thompson, a surveyor attached to United States Army

Major John Wesely Powell's expedition, crossed the Waterpocket Fold while exploring the area. Geologist Clarence Dutton

later spent several summers studying the area's geology. None of these expeditions explored the Waterpocket Fold to any great extent, however. It was, as now, incredibly rugged and forbidding.

Following the American Civil War

, officials of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Salt Lake City sought to establish "missions

" in the remotest niches of the Intermountain West

. In 1866, a quasi-military expedition of Mormons in pursuit of natives penetrated the high valleys to the west. In the 1870s, settlers moved into these valleys, eventually establishing Loa

, Fremont

, Lyman

, Bicknell

, and Torrey

.

Mormon

s settled the Fremont River valley in the 1880s and established Junction (later renamed Fruita

), Caineville and Aldridge. Fruita prospered, Caineville barely survived, and Aldridge died. In addition to farming, lime

was extracted from local limestone

and uranium

was extracted early in the 20th century. In 1904 the first claim to a uranium mine in the area was staked. The resulting Oyler Mine in Grand Wash produced uranium ore.

By 1920 the work was hard but the life in Fruita was good. No more than ten families at one time were sustained by the fertile flood plain of the Fremont River and the land changed ownership over the years. The area remained isolated. The community was later abandoned and later still some buildings were restored by the National Park Service

. Kiln

s once used to produce lime can still be seen in Sulphur Creek and near the campgrounds on Scenic Drive.

" in Torrey

in 1921. Pectol pressed a promotional campaign, furnishing stories to be sent to periodicals and newspapers. In his efforts, he was increasingly aided by his brother-in-law, Joseph S. Hickman, who was Wayne County High School principal. In 1924, Hickman extended community involvement in the promotional effort by organizing a Wayne County-wide Wayne Wonderland Club. That same year, the educator was elected to the Utah State Legislature

.

In 1933, Pectol was elected to the presidency of the Associated Civics Club of Southern Utah, successor to the Wayne Wonderland Club. The club raised U.S. $150.00 to interest a Salt Lake City photographer in taking a series of promotional photographs. For several years, the photographer – J.E. Broaddus – traveled and lectured on "Wayne Wonderland".

In 1933, Pectol himself was elected to the legislature and almost immediately contacted President Franklin D. Roosevelt and asked for the creation of "Wayne Wonderland National Monument" out of the federal lands comprising the bulk of the Capitol Reef area. Federal agencies began a feasibility study and boundary assessment. Meanwhile, Pectol not only guided the government investigators on numerous trips, but escorted an increasing number of visitors. The lectures of Broaddus were having an effect.

President Roosevelt signed a proclamation creating Capitol Reef National Monument on August 2, 1937. In Proclamation 2246, President Roosevelt set aside 37,711 acres (152 km²) of the Capitol Reef area. This comprised an area extending about two miles (3 km) north of present State Route 24

and about 10 miles (16 km) south, just past Capitol Gorge. The Great Depression

years were lean ones for the National Park Service (NPS), the new administering agency. Funds for the administration of Capitol Reef were nonexistent; it would be a long time before the first rangers would arrive.

. A stone ranger cabin and the Sulphur Creek bridge were built and some road work was performed by the Civilian Conservation Corps

and the Works Progress Administration

. Historian and printer Charles Kelly

came to know NPS officials at Zion well and volunteered to 'watchdog' the park for the NPS. Kelly was officially appointed 'custodian-without-pay' in 1943. He was to work as a volunteer until 1950 when the NPS offered him a civil service appointment as the first superintendent.

During the 1950s Kelly was deeply troubled by NPS management acceding to demands of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission

that Capitol Reef National Monument be opened to uranium

prospecting. He felt that the decision had been a mistake and destructive of the long term national interest. As it turned out, there was not enough ore to be worth mining in the monument.

It was not until 1958 that Kelly got additional permanent help in protecting the monument and enforcing regulations; Park Ranger Grant Clark transferred from Zion. The year Clark arrived, fifty-six thousand visitors came to the park and 'Charlie' Kelly retired for the last time, full of years and experiences.

During the 1960s (under the program name Mission 66

), NPS areas nationwide received new facilities to meet the demand of mushrooming park visitation. At Capitol Reef, a 53-site campground at Fruita, staff rental housing, and a new visitor center were built, the latter opening in 1966.

Visitation climbed dramatically after the paved, all-weather State Route 24

was built in 1962 through the Fremont River canyon near Fruita. State Route 24 replaced the narrow Capitol Gorge wagon road about 10 miles (16 km) to the south that frequently washed out. The old road has since only been open to foot traffic. In 1967, 146,598 persons visited the park. The staff was also growing.

During the 1960s, the NPS proceeded to purchase private land parcels at Fruita and Pleasant Creek. Almost all private property passed into public ownership on a "willing buyer-willing seller" basis.

Preservationists convinced President Lyndon B. Johnson

to set aside an enormous area of public lands in 1968, just before he left office. In Presidential Proclamation 3888 an additional 215,056 acres (870 km²) were placed under NPS control. By 1970, Capitol Reef National Monument comprised 254,251 acres (1,028 km²) and sprawled southeast from Thousand Lake Mountain

almost to the Colorado River. The action was controversial locally, and NPS staffing at the monument was inadequate to properly manage the additional land.

. Two bills were introduced into the United States Congress

.

A House bill (H.R. 17152) introduced by Utah

Congressman Laurence J. Burton

called for a 180,000 acre (728 km²) national park and an adjunct 48,000 acre (194 km²) national recreation area

where multiple use (including grazing

) could continue indefinitely. In the United States Senate

, meanwhile, Senate bill S. 531 had already passed on July 1, 1970, and provided for a 230,000 acre (930 km²) national park alone. The bill called for a 25-year phase-out of grazing.

In September 1970, United States Department of Interior officials told a house subcommittee session that they preferred about 254000 acres (1,027.9 km²) be set aside as a national park. They also recommended that the grazing phase-out period be 10 years, rather than 25. They did not favor the adjunct recreation area.

It was not until late 1971 that Congressional action was completed. By then, the 92nd United States Congress

was in session and S. 531 had languished. A new bill, S. 29, was introduced in the Senate by Senator Frank E. Moss of Utah and was essentially the same as the defunct S. 531 except that it called for an additional 10,834 acres (42 km²) of public lands for a Capitol Reef National Park. In the House, Utah Representative K. Gunn McKay

(with Representative Lloyd) had introduced H.R. 9053 to replace the dead H.R. 17152. This time around, the House bill dropped the concept of an adjunct Capitol Reef National Recreation Area and adopted the Senate concept of a 25-year limit on continued grazing. The Department of Interior was still recommending a national park of 254,368 acres (1,029 km²) and a 10-year limit for grazing phase-out.

S. 29 passed the Senate in June and was sent to the House. The House subsequently dropped its own bill and passed the Senate version with an amendment. Because the Senate was not in agreement with the House amendment, differences were worked out in Conference Committee

. The Conference Committee issued their agreeing report on November 30, 1971. The legislation—'An Act to Establish The Capitol Reef National Park in the State of Utah'—became Public Law 92-207 when it was signed by President Richard Nixon

on December 18, 1971.

The area including the park was once the edge of an ancient shallow sea that invaded the land in the Permian

The area including the park was once the edge of an ancient shallow sea that invaded the land in the Permian

, creating the Cutler Formation

. Only the sandstone

of the youngest member of the Cutler Formation, the White Rim, is exposed in the park. The deepening sea left Carbonate

deposits, forming the limestone

of the Kaibab Limestone

, the same formation that rims the Grand Canyon

to the southwest.

During the Triassic

, streams deposited reddish-brown silt

, which later became the siltstone

of the Moenkopi Formation

. Uplift

and erosion

followed. Conglomerate

, itself followed by logs, sand, mud, and wind-transported volcanic ash

, then formed the uranium

-containing Chinle Formation.

The members of the Glen Canyon Group

were all laid down in the middle to late Triassic during a time of increasing aridity. They include:

The San Rafael Group consists of four Jurassic period formations, from oldest to youngest:

Streams once again laid down mud and sand in their channels, on lakebeds, and in swamp

y plains, creating the Morrison Formation

. Early in the Cretaceous

, similar nonmarine sediments were laid down and became the Dakota Sandstone. Eventually, the Cretaceous Seaway covered the Dakota, depositing the Mancos Shale.

Only small remnants of the Mesaverde Group are found, capping a few mesa

s in the park's eastern section (see Geology of the Mesa Verde area).

Near the end of the Cretaceous period, a mountain-building event called the Laramide orogeny

started to compact and uplift the region, forming the Rocky Mountains and creating monocline

s such as the Waterpocket Fold in the park. Ten to fifteen million years ago, the entire region was uplifted much further by the creation of the Colorado Plateau

s. Remarkably, this uplift was very even. Igneous

activity in the form of volcanism

and dike

and sill

intrusion also occurred during this time.

The drainage system in the area was rearranged and steepened, causing streams to downcut

faster and sometimes change course. Wetter times during the ice age

s of the Pleistocene

increased the rate of erosion.

The town nearest Capitol Reef is Torrey, Utah

The town nearest Capitol Reef is Torrey, Utah

, which lies eight miles (13 km) west of the visitor's center on Highway 24. Torrey is very small, but has several motels and restaurants. The park itself has a large campground, but it often fills by early afternoon during busy summer weekends. The Burr Trail Scenic Backway

provides access from the west through the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument and the town of Boulder

. Overnight camping within the park requires a permit from the rangers at the visitor's center.

Activities in the park include hiking, horseback riding, and a driving tour. Mountain biking is prohibited in the park, but many trails just outside the park exist.

The orchards planted by Mormon pioneers are maintained by the Park Service

and different fruit can be harvested throughout the growing season by visitors for a small fee.

Utah

Utah is a state in the Western United States. It was the 45th state to join the Union, on January 4, 1896. Approximately 80% of Utah's 2,763,885 people live along the Wasatch Front, centering on Salt Lake City. This leaves vast expanses of the state nearly uninhabited, making the population the...

. It is 100 miles (160 km) long but fairly narrow. The park, established in 1971, preserves 378 mi² (979 km²) and is open all year, although May through September are the most popular months.

Called "Wayne Wonderland" in the 1920s by local boosters

Boosterism

Boosterism is the act of "boosting," or promoting, one's town, city, or organization, with the goal of improving public perception of it. Boosting can be as simple as "talking up" the entity at a party or as elaborate as establishing a visitors' bureau. It is somewhat associated with American small...

Ephraim P. Pectol and Joseph S. Hickman, Capitol Reef National Park protects colorful canyons, ridges, butte

Butte

A butte is a conspicuous isolated hill with steep, often vertical sides and a small, relatively flat top; it is smaller than mesas, plateaus, and table landform tables. In some regions, such as the north central and northwestern United States, the word is used for any hill...

s, and monoliths. About 75 miles (120 km) of the long up-thrust called the Waterpocket Fold

Waterpocket Fold

The Waterpocket Fold is a geologic landform that defines Capitol Reef National Park in the western United States. This monoclinal fold extends for slightly over 100 miles in the desert of central Utah. It can be seen via three scenic routes in the park. One route leads to a famous landmark known as...

, a rugged spine extending from Thousand Lake Mountain

Thousand Lake Mountain

Thousand Lake Mountain is in South-Central Utah, United States, just North and West of Capitol Reef National Park and North of Boulder Mountain. Thousand Lake Mountain is surrounded by several small towns . The areas on and around Thousand Lake Mountain are used for farming, camping, hiking,...

to Lake Powell

Lake Powell

Lake Powell is a huge reservoir on the Colorado River, straddling the border between Utah and Arizona . It is the second largest man-made reservoir in the United States behind Lake Mead, storing of water when full...

, is preserved within the park. "Capitol Reef" is the name of an especially rugged and spectacular segment of the Waterpocket Fold

Waterpocket Fold

The Waterpocket Fold is a geologic landform that defines Capitol Reef National Park in the western United States. This monoclinal fold extends for slightly over 100 miles in the desert of central Utah. It can be seen via three scenic routes in the park. One route leads to a famous landmark known as...

near the Fremont River. The area was named for a line of white dome

Dome

A dome is a structural element of architecture that resembles the hollow upper half of a sphere. Dome structures made of various materials have a long architectural lineage extending into prehistory....

s and cliffs of Navajo Sandstone, each of which looks somewhat like the United States Capitol

United States Capitol

The United States Capitol is the meeting place of the United States Congress, the legislature of the federal government of the United States. Located in Washington, D.C., it sits atop Capitol Hill at the eastern end of the National Mall...

building, that run from the Fremont River

Fremont River (Utah)

The Fremont River in Utah flows from the Johnson Valley Reservoir, which is located on the Wasatch Plateau near Fish Lake, southwest through Capitol Reef National Park to the Muddy Creek near Hanksville where the two rivers combine to form the Dirty Devil River, a tributary of the Colorado River...

to Pleasant Creek on the Waterpocket Fold. The local word reef referred to any rocky barrier to travel. Easy road access came with the construction in 1962 of State Route 24

Utah State Route 24

State Route 24 is a state highway in south central Utah which runs south from Salina through Sevier County then east through Wayne County and north east through Emery County...

through the Fremont River Canyon.

Geography

Waterpocket Fold

The Waterpocket Fold is a geologic landform that defines Capitol Reef National Park in the western United States. This monoclinal fold extends for slightly over 100 miles in the desert of central Utah. It can be seen via three scenic routes in the park. One route leads to a famous landmark known as...

, a warp in the earth's crust that is 65 million years old. In this fold, newer and older layers of earth folded over each other in an S-shape. This warp, probably caused by the same colliding continental plates

Plate tectonics

Plate tectonics is a scientific theory that describes the large scale motions of Earth's lithosphere...

that created the Rocky Mountains

Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains are a major mountain range in western North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch more than from the northernmost part of British Columbia, in western Canada, to New Mexico, in the southwestern United States...

, has weathered and eroded

Erosion

Erosion is when materials are removed from the surface and changed into something else. It only works by hydraulic actions and transport of solids in the natural environment, and leads to the deposition of these materials elsewhere...

over millennia to expose layers of rock and fossil

Fossil

Fossils are the preserved remains or traces of animals , plants, and other organisms from the remote past...

s. The park is filled with brilliantly colored sandstone

Sandstone

Sandstone is a sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized minerals or rock grains.Most sandstone is composed of quartz and/or feldspar because these are the most common minerals in the Earth's crust. Like sand, sandstone may be any colour, but the most common colours are tan, brown, yellow,...

cliffs, gleaming white domes, and contrasting layers of stone and earth.

The area was named for a line of white dome

Dome

A dome is a structural element of architecture that resembles the hollow upper half of a sphere. Dome structures made of various materials have a long architectural lineage extending into prehistory....

s and cliffs of Navajo Sandstone, each of which looks somewhat like the United States Capitol

United States Capitol

The United States Capitol is the meeting place of the United States Congress, the legislature of the federal government of the United States. Located in Washington, D.C., it sits atop Capitol Hill at the eastern end of the National Mall...

building, that run from the Fremont River

Fremont River (Utah)

The Fremont River in Utah flows from the Johnson Valley Reservoir, which is located on the Wasatch Plateau near Fish Lake, southwest through Capitol Reef National Park to the Muddy Creek near Hanksville where the two rivers combine to form the Dirty Devil River, a tributary of the Colorado River...

to Pleasant Creek on the Waterpocket Fold.

The fold forms a north-to-south barrier that even today has barely been breached by roads. Early settlers referred to parallel, impassable ridges as "reefs", from which the park gets the second half of its name. The first paved road was constructed through the area in 1962. Today, State Route 24

Utah State Route 24

State Route 24 is a state highway in south central Utah which runs south from Salina through Sevier County then east through Wayne County and north east through Emery County...

cuts through the park traveling east and west between Canyonlands National Park

Canyonlands National Park

Canyonlands National Park is a U.S. National Park located in southeastern Utah near the town of Moab and preserves a colorful landscape eroded into countless canyons, mesas and buttes by the Colorado River, the Green River, and their respective tributaries. The park is divided into four districts:...

and Bryce Canyon National Park

Bryce Canyon National Park

Bryce Canyon National Park is a national park located in southwestern Utah in the United States. The major feature of the park is Bryce Canyon which, despite its name, is not a canyon but a giant natural amphitheater created by erosion along the eastern side of the Paunsaugunt Plateau...

, but few other paved roads invade the rugged landscape.

The park is filled with canyons, cliffs, towers, domes, and arches. The Fremont River has cut canyons through parts of the Waterpocket Fold, but most of the park is arid desert country. A scenic drive shows park visitors some of the highlights, but it runs only a few miles from the main highway. Hundreds of miles of trails and unpaved roads lead the more adventurous into the equally scenic backcountry.

Native Americans and Mormons

Fremont culture Native Americans lived near the perennial Fremont River in the northern part of the Capitol Reef Waterpocket Fold around 1000 CE. They irrigatedIrrigation

Irrigation may be defined as the science of artificial application of water to the land or soil. It is used to assist in the growing of agricultural crops, maintenance of landscapes, and revegetation of disturbed soils in dry areas and during periods of inadequate rainfall...

crops of lentil

Lentil

The lentil is an edible pulse. It is a bushy annual plant of the legume family, grown for its lens-shaped seeds...

s, maize, and squash

Squash (fruit)

Squashes generally refer to four species of the genus Cucurbita, also called marrows depending on variety or the nationality of the speaker...

and stored their grain

Cereal

Cereals are grasses cultivated for the edible components of their grain , composed of the endosperm, germ, and bran...

in stone granaries (in part made from the numerous black basalt

Basalt

Basalt is a common extrusive volcanic rock. It is usually grey to black and fine-grained due to rapid cooling of lava at the surface of a planet. It may be porphyritic containing larger crystals in a fine matrix, or vesicular, or frothy scoria. Unweathered basalt is black or grey...

boulders that litter the area). In the 13th century, all of the Native American cultures in this area underwent sudden change, likely due to a long drought. The Fremont settlements and fields were abandoned.

Many years after the Fremont left, Paiute

Paiute

Paiute refers to three closely related groups of Native Americans — the Northern Paiute of California, Idaho, Nevada and Oregon; the Owens Valley Paiute of California and Nevada; and the Southern Paiute of Arizona, southeastern California and Nevada, and Utah.-Origin of name:The origin of...

s moved into the area. These Numic

Numic languages

Numic is a branch of the Uto-Aztecan language family. It includes seven languages spoken by Native American peoples traditionally living in the Great Basin, Colorado River basin, and southern Great Plains. The word Numic comes from the cognate word in all Numic languages for "person." For...

speaking people named the Fremont granaries moki huts and thought they were the homes of a race of tiny people or moki.

In 1872 Alan H. Thompson, a surveyor attached to United States Army

United States Army

The United States Army is the main branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for land-based military operations. It is the largest and oldest established branch of the U.S. military, and is one of seven U.S. uniformed services...

Major John Wesely Powell's expedition, crossed the Waterpocket Fold while exploring the area. Geologist Clarence Dutton

Clarence Dutton

Clarence Edward Dutton was an American geologist and US Army officer. Dutton was born in Wallingford, Connecticut on May 15, 1841...

later spent several summers studying the area's geology. None of these expeditions explored the Waterpocket Fold to any great extent, however. It was, as now, incredibly rugged and forbidding.

Following the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

, officials of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Salt Lake City sought to establish "missions

Mission (Christian)

Christian missionary activities often involve sending individuals and groups , to foreign countries and to places in their own homeland. This has frequently involved not only evangelization , but also humanitarian work, especially among the poor and disadvantaged...

" in the remotest niches of the Intermountain West

Intermountain West

The Intermountain West is a region of North America lying between the Rocky Mountains to the east and the Cascades and Sierra Nevada to the west. It is also called the Intermountain Region.- Topography :...

. In 1866, a quasi-military expedition of Mormons in pursuit of natives penetrated the high valleys to the west. In the 1870s, settlers moved into these valleys, eventually establishing Loa

Loa, Utah

Loa is a town in, and the county seat of, Wayne County, Utah, United States, along State Route 24. The population was 525 at the 2000 census.-Geography:Loa is located at ....

, Fremont

Fremont, Utah

Fremont is a census-designated place in northwestern Wayne County, Utah, United States. It lies along State Route 72 just northeast of the town of Loa, the county seat of Wayne County. To the north is Fishlake National Forest. Fremont's elevation is...

, Lyman

Lyman, Utah

Lyman is a town along State Route 24 in Wayne County, Utah, United States. The population was 234 at the 2000 census.Lyman was originally known as East Loa...

, Bicknell

Bicknell, Utah

Bicknell is a town along State Route 24 in Wayne County, Utah, United States. As of the 2000 census, the town population was 353, a slight increase over the 1990 figure of 327.-History:...

, and Torrey

Torrey, Utah

Torrey is a town located on State Route 24 in Wayne County, Utah, eight miles from Capitol Reef National Park. As of the 2000 census, the town had a total population of 171....

.

Mormon

Mormon

The term Mormon most commonly denotes an adherent, practitioner, follower, or constituent of Mormonism, which is the largest branch of the Latter Day Saint movement in restorationist Christianity...

s settled the Fremont River valley in the 1880s and established Junction (later renamed Fruita

Fruita, Utah

Fruita is the best-known settlement in Capitol Reef National Park in Wayne County, Utah, United States. It is located at the confluence of Fremont River and Sulphur Creek.-History:...

), Caineville and Aldridge. Fruita prospered, Caineville barely survived, and Aldridge died. In addition to farming, lime

Lime (mineral)

Lime is a general term for calcium-containing inorganic materials, in which carbonates, oxides and hydroxides predominate. Strictly speaking, lime is calcium oxide or calcium hydroxide. It is also the name for a single mineral of the CaO composition, occurring very rarely...

was extracted from local limestone

Limestone

Limestone is a sedimentary rock composed largely of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of calcium carbonate . Many limestones are composed from skeletal fragments of marine organisms such as coral or foraminifera....

and uranium

Uranium

Uranium is a silvery-white metallic chemical element in the actinide series of the periodic table, with atomic number 92. It is assigned the chemical symbol U. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons...

was extracted early in the 20th century. In 1904 the first claim to a uranium mine in the area was staked. The resulting Oyler Mine in Grand Wash produced uranium ore.

By 1920 the work was hard but the life in Fruita was good. No more than ten families at one time were sustained by the fertile flood plain of the Fremont River and the land changed ownership over the years. The area remained isolated. The community was later abandoned and later still some buildings were restored by the National Park Service

National Park Service

The National Park Service is the U.S. federal agency that manages all national parks, many national monuments, and other conservation and historical properties with various title designations...

. Kiln

Kiln

A kiln is a thermally insulated chamber, or oven, in which a controlled temperature regime is produced. Uses include the hardening, burning or drying of materials...

s once used to produce lime can still be seen in Sulphur Creek and near the campgrounds on Scenic Drive.

Early protection efforts

Local Ephraim Portman Pectol organized a "booster clubBooster club

A booster club is an organization that is formed to support an associated club, sports team, or organization. Booster clubs are popular in American schools at the high school and university level...

" in Torrey

Torrey, Utah

Torrey is a town located on State Route 24 in Wayne County, Utah, eight miles from Capitol Reef National Park. As of the 2000 census, the town had a total population of 171....

in 1921. Pectol pressed a promotional campaign, furnishing stories to be sent to periodicals and newspapers. In his efforts, he was increasingly aided by his brother-in-law, Joseph S. Hickman, who was Wayne County High School principal. In 1924, Hickman extended community involvement in the promotional effort by organizing a Wayne County-wide Wayne Wonderland Club. That same year, the educator was elected to the Utah State Legislature

Utah State Legislature

The Utah State Legislature is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Utah. It is a bicameral body, comprising the Utah House of Representatives, with 75 Representatives, and the Utah Senate, with 29 State Senators...

.

In 1933, Pectol was elected to the presidency of the Associated Civics Club of Southern Utah, successor to the Wayne Wonderland Club. The club raised U.S. $150.00 to interest a Salt Lake City photographer in taking a series of promotional photographs. For several years, the photographer – J.E. Broaddus – traveled and lectured on "Wayne Wonderland".

In 1933, Pectol himself was elected to the legislature and almost immediately contacted President Franklin D. Roosevelt and asked for the creation of "Wayne Wonderland National Monument" out of the federal lands comprising the bulk of the Capitol Reef area. Federal agencies began a feasibility study and boundary assessment. Meanwhile, Pectol not only guided the government investigators on numerous trips, but escorted an increasing number of visitors. The lectures of Broaddus were having an effect.

President Roosevelt signed a proclamation creating Capitol Reef National Monument on August 2, 1937. In Proclamation 2246, President Roosevelt set aside 37,711 acres (152 km²) of the Capitol Reef area. This comprised an area extending about two miles (3 km) north of present State Route 24

Utah State Route 24

State Route 24 is a state highway in south central Utah which runs south from Salina through Sevier County then east through Wayne County and north east through Emery County...

and about 10 miles (16 km) south, just past Capitol Gorge. The Great Depression

Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe worldwide economic depression in the decade preceding World War II. The timing of the Great Depression varied across nations, but in most countries it started in about 1929 and lasted until the late 1930s or early 1940s...

years were lean ones for the National Park Service (NPS), the new administering agency. Funds for the administration of Capitol Reef were nonexistent; it would be a long time before the first rangers would arrive.

Administration of the monument

Administration of the new monument was placed under the control of Zion National ParkZion National Park

Zion National Park is located in the Southwestern United States, near Springdale, Utah. A prominent feature of the park is Zion Canyon, which is 15 miles long and up to half a mile deep, cut through the reddish and tan-colored Navajo Sandstone by the North Fork of the Virgin River...

. A stone ranger cabin and the Sulphur Creek bridge were built and some road work was performed by the Civilian Conservation Corps

Civilian Conservation Corps

The Civilian Conservation Corps was a public work relief program that operated from 1933 to 1942 in the United States for unemployed, unmarried men from relief families, ages 18–25. A part of the New Deal of President Franklin D...

and the Works Progress Administration

Works Progress Administration

The Works Progress Administration was the largest and most ambitious New Deal agency, employing millions of unskilled workers to carry out public works projects, including the construction of public buildings and roads, and operated large arts, drama, media, and literacy projects...

. Historian and printer Charles Kelly

Charles Kelly (historian)

Charles Kelly was an American historian of the American west whose work focused on activities in the western salt desert of Utah and Nevada during the pioneer period . Kelly also served as the first superintendent of Capitol Reef National Monument in Southern Utah...

came to know NPS officials at Zion well and volunteered to 'watchdog' the park for the NPS. Kelly was officially appointed 'custodian-without-pay' in 1943. He was to work as a volunteer until 1950 when the NPS offered him a civil service appointment as the first superintendent.

During the 1950s Kelly was deeply troubled by NPS management acceding to demands of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission

United States Atomic Energy Commission

The United States Atomic Energy Commission was an agency of the United States government established after World War II by Congress to foster and control the peace time development of atomic science and technology. President Harry S...

that Capitol Reef National Monument be opened to uranium

Uranium

Uranium is a silvery-white metallic chemical element in the actinide series of the periodic table, with atomic number 92. It is assigned the chemical symbol U. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons...

prospecting. He felt that the decision had been a mistake and destructive of the long term national interest. As it turned out, there was not enough ore to be worth mining in the monument.

It was not until 1958 that Kelly got additional permanent help in protecting the monument and enforcing regulations; Park Ranger Grant Clark transferred from Zion. The year Clark arrived, fifty-six thousand visitors came to the park and 'Charlie' Kelly retired for the last time, full of years and experiences.

During the 1960s (under the program name Mission 66

Mission 66

Mission 66 was a US National Park Service ten-year program that was intended to dramatically expand Park Service visitor services by 1966, in time for the 50th anniversary of the establishment of the Park Service....

), NPS areas nationwide received new facilities to meet the demand of mushrooming park visitation. At Capitol Reef, a 53-site campground at Fruita, staff rental housing, and a new visitor center were built, the latter opening in 1966.

Visitation climbed dramatically after the paved, all-weather State Route 24

Utah State Route 24

State Route 24 is a state highway in south central Utah which runs south from Salina through Sevier County then east through Wayne County and north east through Emery County...

was built in 1962 through the Fremont River canyon near Fruita. State Route 24 replaced the narrow Capitol Gorge wagon road about 10 miles (16 km) to the south that frequently washed out. The old road has since only been open to foot traffic. In 1967, 146,598 persons visited the park. The staff was also growing.

During the 1960s, the NPS proceeded to purchase private land parcels at Fruita and Pleasant Creek. Almost all private property passed into public ownership on a "willing buyer-willing seller" basis.

Preservationists convinced President Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson , often referred to as LBJ, was the 36th President of the United States after his service as the 37th Vice President of the United States...

to set aside an enormous area of public lands in 1968, just before he left office. In Presidential Proclamation 3888 an additional 215,056 acres (870 km²) were placed under NPS control. By 1970, Capitol Reef National Monument comprised 254,251 acres (1,028 km²) and sprawled southeast from Thousand Lake Mountain

Thousand Lake Mountain

Thousand Lake Mountain is in South-Central Utah, United States, just North and West of Capitol Reef National Park and North of Boulder Mountain. Thousand Lake Mountain is surrounded by several small towns . The areas on and around Thousand Lake Mountain are used for farming, camping, hiking,...

almost to the Colorado River. The action was controversial locally, and NPS staffing at the monument was inadequate to properly manage the additional land.

National park status

The vast enlargement of the monument and diversification of the scenic resources soon raised another issue: whether Capitol Reef should be a national park, rather than a monumentU.S. National Monument

A National Monument in the United States is a protected area that is similar to a National Park except that the President of the United States can quickly declare an area of the United States to be a National Monument without the approval of Congress. National monuments receive less funding and...

. Two bills were introduced into the United States Congress

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the bicameral legislature of the federal government of the United States, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Congress meets in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C....

.

A House bill (H.R. 17152) introduced by Utah

Utah

Utah is a state in the Western United States. It was the 45th state to join the Union, on January 4, 1896. Approximately 80% of Utah's 2,763,885 people live along the Wasatch Front, centering on Salt Lake City. This leaves vast expanses of the state nearly uninhabited, making the population the...

Congressman Laurence J. Burton

Laurence J. Burton

Laurence Junior Burton was a U.S. Representative from Utah.Born in Ogden, Utah, Burton graduated from Ogden High School in 1944.Enlisted in the United States Navy Air Corps and served from January 1945 to July 1946....

called for a 180,000 acre (728 km²) national park and an adjunct 48,000 acre (194 km²) national recreation area

National Recreation Area

National Recreation Area is a designation for a protected area in the United States, often centered on large reservoirs and emphasizing water-based recreation for a large number of people. The first National Recreation Area was the Boulder Dam Recreation Area...

where multiple use (including grazing

Grazing

Grazing generally describes a type of feeding, in which a herbivore feeds on plants , and also on other multicellular autotrophs...

) could continue indefinitely. In the United States Senate

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

, meanwhile, Senate bill S. 531 had already passed on July 1, 1970, and provided for a 230,000 acre (930 km²) national park alone. The bill called for a 25-year phase-out of grazing.

In September 1970, United States Department of Interior officials told a house subcommittee session that they preferred about 254000 acres (1,027.9 km²) be set aside as a national park. They also recommended that the grazing phase-out period be 10 years, rather than 25. They did not favor the adjunct recreation area.

It was not until late 1971 that Congressional action was completed. By then, the 92nd United States Congress

92nd United States Congress

The Ninety-second United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, composed of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives...

was in session and S. 531 had languished. A new bill, S. 29, was introduced in the Senate by Senator Frank E. Moss of Utah and was essentially the same as the defunct S. 531 except that it called for an additional 10,834 acres (42 km²) of public lands for a Capitol Reef National Park. In the House, Utah Representative K. Gunn McKay

K. Gunn McKay

Koln Gunn McKay was an American politician who represented the state of Utah. He served from January 3, 1971 to January 3, 1981, beginning in the ninety-second Congress and in four succeeding congresses.-Biography:...

(with Representative Lloyd) had introduced H.R. 9053 to replace the dead H.R. 17152. This time around, the House bill dropped the concept of an adjunct Capitol Reef National Recreation Area and adopted the Senate concept of a 25-year limit on continued grazing. The Department of Interior was still recommending a national park of 254,368 acres (1,029 km²) and a 10-year limit for grazing phase-out.

S. 29 passed the Senate in June and was sent to the House. The House subsequently dropped its own bill and passed the Senate version with an amendment. Because the Senate was not in agreement with the House amendment, differences were worked out in Conference Committee

Conference committee

A conference committee is a joint committee of a bicameral legislature, which is appointed by, and consists of, members of both chambers to resolve disagreements on a particular bill...

. The Conference Committee issued their agreeing report on November 30, 1971. The legislation—'An Act to Establish The Capitol Reef National Park in the State of Utah'—became Public Law 92-207 when it was signed by President Richard Nixon

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon was the 37th President of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. The only president to resign the office, Nixon had previously served as a US representative and senator from California and as the 36th Vice President of the United States from 1953 to 1961 under...

on December 18, 1971.

Geology

Permian

The PermianThe term "Permian" was introduced into geology in 1841 by Sir Sir R. I. Murchison, president of the Geological Society of London, who identified typical strata in extensive Russian explorations undertaken with Edouard de Verneuil; Murchison asserted in 1841 that he named his "Permian...

, creating the Cutler Formation

Cutler Formation

The Cutler is a rock unit that is spread across the U.S. states of Arizona, northwest New Mexico, southeast Utah and southwest Colorado. It was laid down in the Early Permian during the Wolfcampian stage. In Arizona and Utah it is often called the Cutler Group but the preferred USGS name is Cutler...

. Only the sandstone

Sandstone

Sandstone is a sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized minerals or rock grains.Most sandstone is composed of quartz and/or feldspar because these are the most common minerals in the Earth's crust. Like sand, sandstone may be any colour, but the most common colours are tan, brown, yellow,...

of the youngest member of the Cutler Formation, the White Rim, is exposed in the park. The deepening sea left Carbonate

Carbonate

In chemistry, a carbonate is a salt of carbonic acid, characterized by the presence of the carbonate ion, . The name may also mean an ester of carbonic acid, an organic compound containing the carbonate group C2....

deposits, forming the limestone

Limestone

Limestone is a sedimentary rock composed largely of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of calcium carbonate . Many limestones are composed from skeletal fragments of marine organisms such as coral or foraminifera....

of the Kaibab Limestone

Kaibab Limestone

The Kaibab is a geologic formation that is spread across the U.S. states of northern Arizona, southern Utah, east central Nevada and southeast California. This geologic unit is part of the Park City Group in Nevada and Utah and is sometimes locally classified as a geologic group in Utah...

, the same formation that rims the Grand Canyon

Grand Canyon

The Grand Canyon is a steep-sided canyon carved by the Colorado River in the United States in the state of Arizona. It is largely contained within the Grand Canyon National Park, the 15th national park in the United States...

to the southwest.

During the Triassic

Triassic

The Triassic is a geologic period and system that extends from about 250 to 200 Mya . As the first period of the Mesozoic Era, the Triassic follows the Permian and is followed by the Jurassic. Both the start and end of the Triassic are marked by major extinction events...

, streams deposited reddish-brown silt

Silt

Silt is granular material of a size somewhere between sand and clay whose mineral origin is quartz and feldspar. Silt may occur as a soil or as suspended sediment in a surface water body...

, which later became the siltstone

Siltstone

Siltstone is a sedimentary rock which has a grain size in the silt range, finer than sandstone and coarser than claystones.- Description :As its name implies, it is primarily composed of silt sized particles, defined as grains 1/16 - 1/256 mm or 4 to 8 on the Krumbein phi scale...

of the Moenkopi Formation

Moenkopi Formation

The Moenkopi is a geological formation that is spread across the U.S. states of New Mexico, northern Arizona, Nevada, southeastern California, eastern Utah and western Colorado. This unit is considered to be a group in Arizona. Part of the Colorado Plateau and Basin and Range, this formation was...

. Uplift

Tectonic uplift

Tectonic uplift is a geological process most often caused by plate tectonics which increases elevation. The opposite of uplift is subsidence, which results in a decrease in elevation. Uplift may be orogenic or isostatic.-Orogenic uplift:...

and erosion

Erosion

Erosion is when materials are removed from the surface and changed into something else. It only works by hydraulic actions and transport of solids in the natural environment, and leads to the deposition of these materials elsewhere...

followed. Conglomerate

Conglomerate (geology)

A conglomerate is a rock consisting of individual clasts within a finer-grained matrix that have become cemented together. Conglomerates are sedimentary rocks consisting of rounded fragments and are thus differentiated from breccias, which consist of angular clasts...

, itself followed by logs, sand, mud, and wind-transported volcanic ash

Volcanic ash

Volcanic ash consists of small tephra, which are bits of pulverized rock and glass created by volcanic eruptions, less than in diameter. There are three mechanisms of volcanic ash formation: gas release under decompression causing magmatic eruptions; thermal contraction from chilling on contact...

, then formed the uranium

Uranium

Uranium is a silvery-white metallic chemical element in the actinide series of the periodic table, with atomic number 92. It is assigned the chemical symbol U. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons...

-containing Chinle Formation.

The members of the Glen Canyon Group

Glen Canyon Group

The Glen Canyon Group is a geologic group of formations that is spread across the U.S. states of Nevada, Utah, northern Arizona, north west New Mexico and western Colorado. It is sometimes called the Glen Canyon Sandstone in Colorado and Utah. There are four formations within the group...

were all laid down in the middle to late Triassic during a time of increasing aridity. They include:

- Wingate SandstoneWingate SandstoneWingate Sandstone is a geologic formation in the Glen Canyon Group that is spread across the Colorado Plateau province of the United States, including northern Arizona, northwest Colorado, Nevada, and Utah. This rock formation is particularly prominent in southeastern Utah, where it forms...

: Sand dunes on the shore of an ancient sea. - Kayenta FormationKayenta FormationThe Kayenta Formation is a geologic layer in the Glen Canyon Group that is spread across the Colorado Plateau province of the United States, including northern Arizona, northwest Colorado, Nevada, and Utah. This rock formation is particularly prominent in southeastern Utah, where it is seen in the...

: Thin-bedded layers of sand deposited by slow-moving streams in channels and across low plains. - Navajo SandstoneNavajo SandstoneNavajo Sandstone is a geologic formation in the Glen Canyon Group that is spread across the U.S. states of northern Arizona, northwest Colorado, and Utah; as part of the Colorado Plateau province of the United States...

: Huge fossilized sand dunes from a massive SaharaSaharaThe Sahara is the world's second largest desert, after Antarctica. At over , it covers most of Northern Africa, making it almost as large as Europe or the United States. The Sahara stretches from the Red Sea, including parts of the Mediterranean coasts, to the outskirts of the Atlantic Ocean...

-like desertDesertA desert is a landscape or region that receives an extremely low amount of precipitation, less than enough to support growth of most plants. Most deserts have an average annual precipitation of less than...

.

The San Rafael Group consists of four Jurassic period formations, from oldest to youngest:

- Carmel FormationCarmel FormationThe Carmel Formation is a geologic formation in the San Rafael Group that is spread across the U.S. states of Wyoming, Utah, Colorado, north east Arizona and New Mexico...

: GypsumGypsumGypsum is a very soft sulfate mineral composed of calcium sulfate dihydrate, with the chemical formula CaSO4·2H2O. It is found in alabaster, a decorative stone used in Ancient Egypt. It is the second softest mineral on the Mohs Hardness Scale...

, sandSandSand is a naturally occurring granular material composed of finely divided rock and mineral particles.The composition of sand is highly variable, depending on the local rock sources and conditions, but the most common constituent of sand in inland continental settings and non-tropical coastal...

, and limey siltSiltSilt is granular material of a size somewhere between sand and clay whose mineral origin is quartz and feldspar. Silt may occur as a soil or as suspended sediment in a surface water body...

laid down in what may have been a grabenGrabenIn geology, a graben is a depressed block of land bordered by parallel faults. Graben is German for ditch. Graben is used for both the singular and plural....

that was periodically flooded by sea water. - Entrada SandstoneEntrada SandstoneThe Entrada Sandstone is a formation in the San Rafael Group that is spread across the U.S. states of Wyoming, Colorado, northwest New Mexico, northeast Arizona and southeast Utah...

: Sandstone from barrier islands/sand barsShoalShoal, shoals or shoaling may mean:* Shoal, a sandbank or reef creating shallow water, especially where it forms a hazard to shipping* Shoal draught , of a boat with shallow draught which can pass over some shoals: see Draft...

in a near-shore environment. - Curtis Formation: Made from conglomerate, sandstone, and shale.

- Summerville FormationSummerville FormationThe Summerville Formation is a geological formation in New Mexico, Colorado, and Utah of the Southwestern United States. It dates back to the Middle Jurassic.-Dinosaurs:Theropod tracks geographically located in Utah, New Mexico, and Colorado, USA....

: Reddish-brown mud and white sand deposited in tidal flats.

Streams once again laid down mud and sand in their channels, on lakebeds, and in swamp

Swamp

A swamp is a wetland with some flooding of large areas of land by shallow bodies of water. A swamp generally has a large number of hammocks, or dry-land protrusions, covered by aquatic vegetation, or vegetation that tolerates periodical inundation. The two main types of swamp are "true" or swamp...

y plains, creating the Morrison Formation

Morrison Formation

The Morrison Formation is a distinctive sequence of Late Jurassic sedimentary rock that is found in the western United States, which has been the most fertile source of dinosaur fossils in North America. It is composed of mudstone, sandstone, siltstone and limestone and is light grey, greenish...

. Early in the Cretaceous

Cretaceous

The Cretaceous , derived from the Latin "creta" , usually abbreviated K for its German translation Kreide , is a geologic period and system from circa to million years ago. In the geologic timescale, the Cretaceous follows the Jurassic period and is followed by the Paleogene period of the...

, similar nonmarine sediments were laid down and became the Dakota Sandstone. Eventually, the Cretaceous Seaway covered the Dakota, depositing the Mancos Shale.

Only small remnants of the Mesaverde Group are found, capping a few mesa

Mesa

A mesa or table mountain is an elevated area of land with a flat top and sides that are usually steep cliffs. It takes its name from its characteristic table-top shape....

s in the park's eastern section (see Geology of the Mesa Verde area).

Near the end of the Cretaceous period, a mountain-building event called the Laramide orogeny

Laramide orogeny

The Laramide orogeny was a period of mountain building in western North America, which started in the Late Cretaceous, 70 to 80 million years ago, and ended 35 to 55 million years ago. The exact duration and ages of beginning and end of the orogeny are in dispute, as is the cause. The Laramide...

started to compact and uplift the region, forming the Rocky Mountains and creating monocline

Monocline

A monocline is a step-like fold in rock strata consisting of a zone of steeper dip within an otherwise horizontal or gently-dipping sequence.-Formation:Monoclines may be formed in several different ways...

s such as the Waterpocket Fold in the park. Ten to fifteen million years ago, the entire region was uplifted much further by the creation of the Colorado Plateau

Colorado Plateau

The Colorado Plateau, also called the Colorado Plateau Province, is a physiographic region of the Intermontane Plateaus, roughly centered on the Four Corners region of the southwestern United States. The province covers an area of 337,000 km2 within western Colorado, northwestern New Mexico,...

s. Remarkably, this uplift was very even. Igneous

Igneous rock

Igneous rock is one of the three main rock types, the others being sedimentary and metamorphic rock. Igneous rock is formed through the cooling and solidification of magma or lava...

activity in the form of volcanism

Volcanism

Volcanism is the phenomenon connected with volcanoes and volcanic activity. It includes all phenomena resulting from and causing magma within the crust or mantle of a planet to rise through the crust and form volcanic rocks on the surface....

and dike

Dike (geology)

A dike or dyke in geology is a type of sheet intrusion referring to any geologic body that cuts discordantly across* planar wall rock structures, such as bedding or foliation...

and sill

Sill (geology)

In geology, a sill is a tabular sheet intrusion that has intruded between older layers of sedimentary rock, beds of volcanic lava or tuff, or even along the direction of foliation in metamorphic rock. The term sill is synonymous with concordant intrusive sheet...

intrusion also occurred during this time.

The drainage system in the area was rearranged and steepened, causing streams to downcut

Downcutting

Downcutting, also called erosional downcutting or downward erosion or vertical erosion is a geological process that deepens the channel of a stream or valley by removing material from the stream's bed or the valley's floor. How fast downcutting occurs depends on the stream's base level, which is...

faster and sometimes change course. Wetter times during the ice age

Ice age

An ice age or, more precisely, glacial age, is a generic geological period of long-term reduction in the temperature of the Earth's surface and atmosphere, resulting in the presence or expansion of continental ice sheets, polar ice sheets and alpine glaciers...

s of the Pleistocene

Pleistocene

The Pleistocene is the epoch from 2,588,000 to 11,700 years BP that spans the world's recent period of repeated glaciations. The name pleistocene is derived from the Greek and ....

increased the rate of erosion.

Visiting the park

Torrey, Utah

Torrey is a town located on State Route 24 in Wayne County, Utah, eight miles from Capitol Reef National Park. As of the 2000 census, the town had a total population of 171....

, which lies eight miles (13 km) west of the visitor's center on Highway 24. Torrey is very small, but has several motels and restaurants. The park itself has a large campground, but it often fills by early afternoon during busy summer weekends. The Burr Trail Scenic Backway

Burr Trail Scenic Backway

The Burr Trail Scenic Backway is a backcountry route extending from the town of Boulder, Utah, through Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument into Capital Reef National Park and then to the community of Bullfrog in Glen Canyon National Recreation Area....

provides access from the west through the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument and the town of Boulder

Boulder, Utah

Boulder is a town in Garfield County, Utah, United States, 27 miles northeast of Escalante on Utah Scenic Byway 12 at its intersection with the Burr Trail...

. Overnight camping within the park requires a permit from the rangers at the visitor's center.

Activities in the park include hiking, horseback riding, and a driving tour. Mountain biking is prohibited in the park, but many trails just outside the park exist.

The orchards planted by Mormon pioneers are maintained by the Park Service

and different fruit can be harvested throughout the growing season by visitors for a small fee.

External links

- Official site: Capitol Reef National Park

- Capitol Reef National Park | Utah.com

- Capitol Reef Country Wayne County Tourism Services

- Capitol Reef Natural History Association Support historical, cultural, scientific, interpretive and educational activities at Capitol Reef National Park.