Pharaoh (novel)

Encyclopedia

Novel

A novel is a book of long narrative in literary prose. The genre has historical roots both in the fields of the medieval and early modern romance and in the tradition of the novella. The latter supplied the present generic term in the late 18th century....

by the Polish

Poland

Poland , officially the Republic of Poland , is a country in Central Europe bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north...

writer Bolesław Prus (1847–1912). Composed over a year's time in 1894–95, it was the sole historical novel

Historical novel

According to Encyclopædia Britannica, a historical novel is-Development:An early example of historical prose fiction is Luó Guànzhōng's 14th century Romance of the Three Kingdoms, which covers one of the most important periods of Chinese history and left a lasting impact on Chinese culture.The...

by an author who had earlier disapproved of historical novels on the ground that they inevitably distort history.

Pharaoh has been described by Czesław Miłosz as a "novel on... mechanism[s] of state power

Political power

Political power is a type of power held by a group in a society which allows administration of some or all of public resources, including labour, and wealth. There are many ways to obtain possession of such power. At the nation-state level political legitimacy for political power is held by the...

and, as such, ... probably unique in world literature

World literature

World literature refers to literature from all over the world, including African literature, American literature, Arabic literature, Asian literature, Australasian literature, Caribbean Literature, English literature, European literature, Indian literature, Latin American literature, Persian...

of the nineteenth century.... Prus, [in] selecting the reign of 'Pharaoh

Pharaoh

Pharaoh is a title used in many modern discussions of the ancient Egyptian rulers of all periods. The title originates in the term "pr-aa" which means "great house" and describes the royal palace...

Ramses XIII' in the eleventh century BCE, sought a perspective that was detached from... pressures of [topicality] and censorship. Through his analysis of the dynamics of an ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt was an ancient civilization of Northeastern Africa, concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in what is now the modern country of Egypt. Egyptian civilization coalesced around 3150 BC with the political unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under the first pharaoh...

ian society, he... suggest[s] an archetype of the struggle for power that goes on within any state."

Pharaoh is set in the Egypt of 1087–85 BCE as that country experiences internal stresses and external threats that will culminate in the fall of its Twentieth Dynasty and New Kingdom

New Kingdom

The New Kingdom of Egypt, also referred to as the Egyptian Empire is the period in ancient Egyptian history between the 16th century BC and the 11th century BC, covering the Eighteenth, Nineteenth, and Twentieth Dynasties of Egypt....

. The young protagonist Ramses learns that those who would challenge the powers that be are vulnerable to co-option, seduction

Seduction

In social science, seduction is the process of deliberately enticing a person to engage. The word seduction stems from Latin and means literally "to lead astray". As a result, the term may have a positive or negative connotation...

, subornation, defamation, intimidation and assassination

Assassination

To carry out an assassination is "to murder by a sudden and/or secret attack, often for political reasons." Alternatively, assassination may be defined as "the act of deliberately killing someone, especially a public figure, usually for hire or for political reasons."An assassination may be...

. Perhaps the chief lesson, belatedly absorbed by Ramses as pharaoh, is the importance, to power, of knowledge

Knowledge

Knowledge is a familiarity with someone or something unknown, which can include information, facts, descriptions, or skills acquired through experience or education. It can refer to the theoretical or practical understanding of a subject...

.

Prus' vision of the fall of an ancient civilization derives some of its power from the author's intimate awareness of the final demise of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was a dualistic state of Poland and Lithuania ruled by a common monarch. It was the largest and one of the most populous countries of 16th- and 17th‑century Europe with some and a multi-ethnic population of 11 million at its peak in the early 17th century...

in 1795, a century before the completion of the novel.

Preparatory to writing Pharaoh, Prus immersed himself in ancient Egyptian history, geography, customs, religion, art and writings. In the course of telling his story of power, personality, and the fates of nations, he produced a compelling literary depiction of life at every level of ancient Egyptian society. Further, he offers a vision of mankind as rich as Shakespeare's, ranging from the sublime

Sublime (philosophy)

In aesthetics, the sublime is the quality of greatness, whether physical, moral, intellectual, metaphysical, aesthetic, spiritual or artistic...

to the quotidian, from the tragic

Tragedy

Tragedy is a form of art based on human suffering that offers its audience pleasure. While most cultures have developed forms that provoke this paradoxical response, tragedy refers to a specific tradition of drama that has played a unique and important role historically in the self-definition of...

to the comic

Comedy

Comedy , as a popular meaning, is any humorous discourse or work generally intended to amuse by creating laughter, especially in television, film, and stand-up comedy. This must be carefully distinguished from its academic definition, namely the comic theatre, whose Western origins are found in...

. The book is written in limpid prose and is imbued with poetry

Poetry

Poetry is a form of literary art in which language is used for its aesthetic and evocative qualities in addition to, or in lieu of, its apparent meaning...

, leavened with humor, graced with moments of transcendent beauty.

Pharaoh has been translated into twenty languages and adapted as a 1966 Polish feature film

Pharaoh (film)

Pharaoh is a 1966 Polish film directed by Jerzy Kawalerowicz and adapted from the eponymous novel by the Polish writer Bolesław Prus. In 1967 it was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film...

. It is also known to have been Joseph Stalin's

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

favourite book.

Publication

Pharaoh comprises a compact, substantial introduction; sixty-seven chapters; and an evocative epilogueEpilogue

An epilogue, epilog or afterword is a piece of writing at the end of a work of literature or drama, usually used to bring closure to the work...

(the latter omitted at the book's original publication, and restored in the 1950s). Like Prus' previous novels, Pharaoh debuted (1895–96) in newspaper serialization

Serial (literature)

In literature, a serial is a publishing format by which a single large work, most often a work of narrative fiction, is presented in contiguous installments—also known as numbers, parts, or fascicles—either issued as separate publications or appearing in sequential issues of a single periodical...

—in the Warsaw

Warsaw

Warsaw is the capital and largest city of Poland. It is located on the Vistula River, roughly from the Baltic Sea and from the Carpathian Mountains. Its population in 2010 was estimated at 1,716,855 residents with a greater metropolitan area of 2,631,902 residents, making Warsaw the 10th most...

Tygodnik Ilustrowany (Illustrated Weekly). It was dedicated "To my wife, Oktawia Głowacka, née

NEE

NEE is a political protest group whose goal was to provide an alternative for voters who are unhappy with all political parties at hand in Belgium, where voting is compulsory.The NEE party was founded in 2005 in Antwerp...

Trembińska, as a small token of esteem and affection."

Unlike the author's earlier novels, Pharaoh had first been composed in its entirety, rather than being written in chapters from issue to issue. This may account for its often being described as Prus' "best-composed novel"—indeed, "one of the best-composed Polish novels."

The original 1897 book edition

Edition

In printmaking, an edition is a number of prints struck from one plate, usually at the same time. This is the meaning covered by this article...

and some subsequent ones divided the novel into three volumes. Later editions have presented it in two volumes or in a single one. Except in wartime, the book has never been out of print in Poland.

Plot

Pharaoh begins with one of the more memorable openings in a novel — an opening written in the style of an ancient chronicleChronicle

Generally a chronicle is a historical account of facts and events ranged in chronological order, as in a time line. Typically, equal weight is given for historically important events and local events, the purpose being the recording of events that occurred, seen from the perspective of the...

:

Pharaoh combines features of several literary genre

Literary genre

A literary genre is a category of literary composition. Genres may be determined by literary technique, tone, content, or even length. Genre should not be confused with age category, by which literature may be classified as either adult, young-adult, or children's. They also must not be confused...

s: the historical novel, the political novel, the Bildungsroman, the utopian novel, the sensation novel

Sensation novel

The sensation novel was a literary genre of fiction popular in Great Britain in the 1860s and 1870s, following on from earlier melodramatic novels and the Newgate novels, which focused on tales woven around criminal biographies, also descend from the gothic and romantic genres of fiction...

. It also comprises a number of interbraided strands — including the plot line, Egypt's cycle of season

Season

A season is a division of the year, marked by changes in weather, ecology, and hours of daylight.Seasons result from the yearly revolution of the Earth around the Sun and the tilt of the Earth's axis relative to the plane of revolution...

s, the country's geography

Geography

Geography is the science that studies the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth. A literal translation would be "to describe or write about the Earth". The first person to use the word "geography" was Eratosthenes...

and monument

Monument

A monument is a type of structure either explicitly created to commemorate a person or important event or which has become important to a social group as a part of their remembrance of historic times or cultural heritage, or simply as an example of historic architecture...

s, and ancient Egyptian practices (e.g. mummification

Mummy

A mummy is a body, human or animal, whose skin and organs have been preserved by either intentional or incidental exposure to chemicals, extreme coldness , very low humidity, or lack of air when bodies are submerged in bogs, so that the recovered body will not decay further if kept in cool and dry...

ritual

Ritual

A ritual is a set of actions, performed mainly for their symbolic value. It may be prescribed by a religion or by the traditions of a community. The term usually excludes actions which are arbitrarily chosen by the performers....

s and techniques) — each of which rises to prominence at appropriate moments.

Much as in an ancient Greek tragedy, the fate of the novel's protagonist

Protagonist

A protagonist is the main character of a literary, theatrical, cinematic, or musical narrative, around whom the events of the narrative's plot revolve and with whom the audience is intended to most identify...

, the future "Ramses XIII," is known from the beginning. Prus closes his introduction

Introduction (essay)

An introduction is a beginning section which states the purpose and goals of the following writing. The introduction is usually interesting and it intrigues the reader and causes him or her to want to read on. The sentence in which the introduction begins can be a question or just a statement...

with the statement that the narrative "relates to the eleventh century before Christ

Christ

Christ is the English term for the Greek meaning "the anointed one". It is a translation of the Hebrew , usually transliterated into English as Messiah or Mashiach...

, when the Twentieth Dynasty fell and when, after the demise of the Son of the Sun the eternally living Ramses XIII, the throne was seized by, and the uraeus

Uraeus

The Uraeus is the stylized, upright form of an Egyptian spitting cobra , used as a symbol of sovereignty, royalty, deity, and divine authority in ancient Egypt.The Uraeus is a symbol for the goddess Wadjet, who was one of the earliest Egyptian deities and who...

came to adorn the brow of, the eternally living Son of the Sun Sem-amen-Herhor

Herihor

Herihor was an Egyptian army officer and High Priest of Amun at Thebes during the reign of Pharaoh Ramesses XI although Karl Jansen Winkeln has argued that Piankh preceded Herihor as High Priest at Thebes and that Herihor outlived Ramesses XI before being succeeded in this office by Pinedjem I,...

, High Priest

High priest

The term "high priest" usually refers either to an individual who holds the office of ruler-priest, or to one who is the head of a religious caste.-Ancient Egypt:...

of Amon

Amun

Amun, reconstructed Egyptian Yamānu , was a god in Egyptian mythology who in the form of Amun-Ra became the focus of the most complex system of theology in Ancient Egypt...

." What the novel will subsequently reveal is the elements that lead to this denouement—the character

Character structure

A character structure is a system of relatively permanent traits that are manifested in the specific ways that an individual relates and reacts to others, to various kinds of stimuli, and to the environment...

traits of the principals, the social

Social

The term social refers to a characteristic of living organisms...

forces in play.

Ancient Egypt at the end of its New Kingdom

New Kingdom

The New Kingdom of Egypt, also referred to as the Egyptian Empire is the period in ancient Egyptian history between the 16th century BC and the 11th century BC, covering the Eighteenth, Nineteenth, and Twentieth Dynasties of Egypt....

period is experiencing adversities. The deserts are eroding Egypt's arable land

Arable land

In geography and agriculture, arable land is land that can be used for growing crops. It includes all land under temporary crops , temporary meadows for mowing or pasture, land under market and kitchen gardens and land temporarily fallow...

. The country's population has declined from eight to six million. Foreign peoples are entering Egypt in ever-growing numbers, undermining its unity. The chasm between the peasant

Peasant

A peasant is an agricultural worker who generally tend to be poor and homeless-Etymology:The word is derived from 15th century French païsant meaning one from the pays, or countryside, ultimately from the Latin pagus, or outlying administrative district.- Position in society :Peasants typically...

s and craftsmen on one hand, and the ruling class

Ruling class

The term ruling class refers to the social class of a given society that decides upon and sets that society's political policy - assuming there is one such particular class in the given society....

es on the other, is growing, exacerbated by the ruling elites' fondness for luxury and idleness. The country is becoming ever more deeply indebted to Phoenicia

Phoenicia

Phoenicia , was an ancient civilization in Canaan which covered most of the western, coastal part of the Fertile Crescent. Several major Phoenician cities were built on the coastline of the Mediterranean. It was an enterprising maritime trading culture that spread across the Mediterranean from 1550...

n merchants, as import

Import

The term import is derived from the conceptual meaning as to bring in the goods and services into the port of a country. The buyer of such goods and services is referred to an "importer" who is based in the country of import whereas the overseas based seller is referred to as an "exporter". Thus...

ed goods destroy native industries

Industry

Industry refers to the production of an economic good or service within an economy.-Industrial sectors:There are four key industrial economic sectors: the primary sector, largely raw material extraction industries such as mining and farming; the secondary sector, involving refining, construction,...

.

The Egyptian priesthood, backbone of the bureaucracy

Bureaucracy

A bureaucracy is an organization of non-elected officials of a governmental or organization who implement the rules, laws, and functions of their institution, and are occasionally characterized by officialism and red tape.-Weberian bureaucracy:...

and virtual monopolists of knowledge, have grown immensely wealthy at the expense of the pharaoh and the country. At the same time, Egypt is facing prospective peril at the hands of rising powers to the north — Assyria

Assyria

Assyria was a Semitic Akkadian kingdom, extant as a nation state from the mid–23rd century BC to 608 BC centred on the Upper Tigris river, in northern Mesopotamia , that came to rule regional empires a number of times through history. It was named for its original capital, the ancient city of Assur...

and Persia.

Crown Prince

A crown prince or crown princess is the heir or heiress apparent to the throne in a royal or imperial monarchy. The wife of a crown prince is also titled crown princess....

and viceroy

Viceroy

A viceroy is a royal official who runs a country, colony, or province in the name of and as representative of the monarch. The term derives from the Latin prefix vice-, meaning "in the place of" and the French word roi, meaning king. A viceroy's province or larger territory is called a viceroyalty...

Ramses, having made a careful study of his country and of the challenges that it faces, evolves a strategy that he hopes will arrest the decline of his own political power

Political power

Political power is a type of power held by a group in a society which allows administration of some or all of public resources, including labour, and wealth. There are many ways to obtain possession of such power. At the nation-state level political legitimacy for political power is held by the...

and of Egypt's internal viability and international standing. Ramses plans to win over or subordinate the priesthood, especially the High Priest of Amon

Amun

Amun, reconstructed Egyptian Yamānu , was a god in Egyptian mythology who in the form of Amun-Ra became the focus of the most complex system of theology in Ancient Egypt...

, Herhor

Herihor

Herihor was an Egyptian army officer and High Priest of Amun at Thebes during the reign of Pharaoh Ramesses XI although Karl Jansen Winkeln has argued that Piankh preceded Herihor as High Priest at Thebes and that Herihor outlived Ramesses XI before being succeeded in this office by Pinedjem I,...

; obtain for the country's use the treasure

Treasure

Treasure is a concentration of riches, often one which is considered lost or forgotten until being rediscovered...

s that lie stored in the Labyrinth; and, emulating Ramses the Great's military exploits, wage war on Assyria

Assyria

Assyria was a Semitic Akkadian kingdom, extant as a nation state from the mid–23rd century BC to 608 BC centred on the Upper Tigris river, in northern Mesopotamia , that came to rule regional empires a number of times through history. It was named for its original capital, the ancient city of Assur...

.

Ramses proves himself a brilliant military commander in a victorious lightning war against the invading Libya

Libya

Libya is an African country in the Maghreb region of North Africa bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Sudan to the southeast, Chad and Niger to the south, and Algeria and Tunisia to the west....

ns. On succeeding to the throne, he encounters the adamant opposition of the priestly hierarchy

Hierarchy

A hierarchy is an arrangement of items in which the items are represented as being "above," "below," or "at the same level as" one another...

to his planned reforms. The Egyptian populace is instinctively drawn to Ramses, but he must still win over or crush the priesthood and their adherents.

In the course of the political intrigue, Ramses' private life becomes hostage to the conflicting interests of the Phoenicians and the Egyptian high priests.

Ramses' ultimate downfall is caused by his underestimation of his opponents and by his impatience with priestly obscurantism

Obscurantism

Obscurantism is the practice of deliberately preventing the facts or the full details of some matter from becoming known. There are two, common, historical and intellectual, denotations: 1) restricting knowledge—opposition to the spread of knowledge, a policy of withholding knowledge from the...

. Along with the chaff of the priests' myth

Mythology

The term mythology can refer either to the study of myths, or to a body or collection of myths. As examples, comparative mythology is the study of connections between myths from different cultures, whereas Greek mythology is the body of myths from ancient Greece...

s and ritual

Ritual

A ritual is a set of actions, performed mainly for their symbolic value. It may be prescribed by a religion or by the traditions of a community. The term usually excludes actions which are arbitrarily chosen by the performers....

s, he has inadvertently discarded a crucial piece of scientific knowledge

Science

Science is a systematic enterprise that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe...

.

Ramses is succeeded to the throne by his arch-enemy Herhor

Herihor

Herihor was an Egyptian army officer and High Priest of Amun at Thebes during the reign of Pharaoh Ramesses XI although Karl Jansen Winkeln has argued that Piankh preceded Herihor as High Priest at Thebes and that Herihor outlived Ramesses XI before being succeeded in this office by Pinedjem I,...

, who paradoxically ends up raising treasure from the Labyrinth to finance the very social reforms that had been planned by Ramses, and whose implementation Herhor and his allies had blocked. But it is too late to arrest the decline of the Egyptian polity and to avert the eventual fall of the Egyptian civilization.

The novel closes with a poetic epilogue that reflects Prus' own path through life. The priest Pentuer, who had declined to betray the priesthood and aid Ramses' campaign to reform the Egyptian polity, mourns Ramses, who like the teenage Prus had risked all to save his country. As Pentuer and his mentor

Mentor

In Greek mythology, Mentor was the son of Alcimus or Anchialus. In his old age Mentor was a friend of Odysseus who placed Mentor and Odysseus' foster-brother Eumaeus in charge of his son Telemachus, and of Odysseus' palace, when Odysseus left for the Trojan War.When Athena visited Telemachus she...

, the sage priest Menes, listen to the song of a mendicant

Mendicant

The term mendicant refers to begging or relying on charitable donations, and is most widely used for religious followers or ascetics who rely exclusively on charity to survive....

priest, Pentuer says:

Characters

Prus took characters' names where he found them, sometimes anachronistically or anatopistically. At other times (as with the priest Samentu in chapter 55) he apparently invented them. The origins of the names of some prominent characters may be of interest:- RamsesRamessesRamesses is the name conventionally given in English transliteration to 11 Egyptian pharaohs of the later New Kingdom period. The name essentially translates as "Born of the sun-god Ra"....

, the novel's protagonistProtagonistA protagonist is the main character of a literary, theatrical, cinematic, or musical narrative, around whom the events of the narrative's plot revolve and with whom the audience is intended to most identify...

: the name of two pharaohs of the 19th DynastyNineteenth dynasty of EgyptThe Nineteenth Dynasty of ancient Egypt was one of the periods of the Egyptian New Kingdom. Founded by Vizier Ramesses I, whom Pharaoh Horemheb chose as his successor to the throne, this dynasty is best known for its military conquests in Palestine, Lebanon, and Syria.The warrior kings of the...

and nine pharaohs of the 20th DynastyTwentieth dynasty of EgyptThe Eighteenth, Nineteenth, and Twentieth Dynasties of ancient Egypt are often combined under the group title, New Kingdom. This dynasty is considered to be the last one of the New Kingdom of Egypt, and was followed by the Third Intermediate Period....

. - AmenhotepAmenhotepAmenhotep was an ancient Egyptian name. Its Greek version is Amenophis. Its notable bearers were:-Pharaohs of the 18th dynasty:*Amenhotep I*Amenhotep II*Amenhotep III*Amenhotep IV -Princes:...

, high priestHigh priestThe term "high priest" usually refers either to an individual who holds the office of ruler-priest, or to one who is the head of a religious caste.-Ancient Egypt:...

and Ramses' maternal grandfather: the name of four pharaohs of the 18th Dynasty. - Herhor, high priest of AmonAmunAmun, reconstructed Egyptian Yamānu , was a god in Egyptian mythology who in the form of Amun-Ra became the focus of the most complex system of theology in Ancient Egypt...

and Ramses' principal antagonistAntagonistAn antagonist is a character, group of characters, or institution, that represents the opposition against which the protagonist must contend...

: historic high priest HerihorHerihorHerihor was an Egyptian army officer and High Priest of Amun at Thebes during the reign of Pharaoh Ramesses XI although Karl Jansen Winkeln has argued that Piankh preceded Herihor as High Priest at Thebes and that Herihor outlived Ramesses XI before being succeeded in this office by Pinedjem I,...

. - Pentuer, scribeScribeA scribe is a person who writes books or documents by hand as a profession and helps the city keep track of its records. The profession, previously found in all literate cultures in some form, lost most of its importance and status with the advent of printing...

to Herhor: historic scribe Pentewere (Pentaur); or perhaps PentawerPentawerPentawer was an ancient Egyptian prince of the 20th dynasty, a son of Pharaoh Ramesses III and a secondary wife, Tiye.He was to be the beneficiary of the harem plot planned by his mother Tiye to assassinate the pharaoh. Tiye wanted her son to succeed the pharaoh, even though the rightful heir was...

, a son of Pharaoh Ramses III. - ThutmoseThutmoseThutmose is an Anglicization of the Egyptian name dhwty-ms, usually translated as "Born of the god Thoth". It may refer to several individuals from the 18th Dynasty:*Thutmose I, third pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty*Thutmose II Thutmose (also rendered Thutmosis, Tuthmose, Tutmosis, Thothmes,...

, Ramses' cousin: a fairly common name, also the name of four pharaohs of the 18th DynastyEighteenth dynasty of EgyptThe eighteenth dynasty of ancient Egypt is perhaps the best known of all the dynasties of ancient Egypt...

. - SarahSarahSarah or Sara was the wife of Abraham and the mother of Isaac as described in the Hebrew Bible and the Quran. Her name was originally Sarai...

, Ramses' Jewish mistressMistress (lover)A mistress is a long-term female lover and companion who is not married to her partner; the term is used especially when her partner is married. The relationship generally is stable and at least semi-permanent; however, the couple does not live together openly. Also the relationship is usually,...

; TaphathAbinadabAbinadab may refer to:# A man of Kirjath-jearim widely identified as a Levite , in whose house the ark of the covenant was deposited after having been brought back from the land of the Philistines . It remained there twenty years, until it was at length removed by David . It has been argued that...

, Sarah's relative and servant; GideonGideonGideon was an Israelite judge who appears in the Book of JudgesGideon may also refer to:- Religion :* Gideon , a figure in the Book of Mormon* Gideons International, distributor of copies of the Bible- Media :...

, Sarah's father: names drawn from those of BiblicalBibleThe Bible refers to any one of the collections of the primary religious texts of Judaism and Christianity. There is no common version of the Bible, as the individual books , their contents and their order vary among denominations...

personalities. - Patrokles, a GreekGreeceGreece , officially the Hellenic Republic , and historically Hellas or the Republic of Greece in English, is a country in southeastern Europe....

mercenaryMercenaryA mercenary, is a person who takes part in an armed conflict based on the promise of material compensation rather than having a direct interest in, or a legal obligation to, the conflict itself. A non-conscript professional member of a regular army is not considered to be a mercenary although he...

general: Patroklos, in Homer's IliadIliadThe Iliad is an epic poem in dactylic hexameters, traditionally attributed to Homer. Set during the Trojan War, the ten-year siege of the city of Troy by a coalition of Greek states, it tells of the battles and events during the weeks of a quarrel between King Agamemnon and the warrior Achilles...

. - Ennana, a junior military officer: Egyptian scribe-pupil's name, attached to an ancient text (cited in Pharaoh, chapter 4: Ennana's "plaint on the sore lot of a junior officer").

- Nikotris, Ramses' mother: historic Queen NitocrisNitocrisNitocris has been claimed to have been the last pharaoh of the Sixth Dynasty. Her name is found in the Histories of Herodotus and writings of Manetho but her historicity is questionable. She might have been an interregnum queen...

; or perhaps the identically named daughter, Nitocris, of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty king Psamtik I. - DagonDagonDagon was originally an Assyro-Babylonian fertility god who evolved into a major northwest Semitic god, reportedly of grain and fish and/or fishing...

, a PhoeniciaPhoeniciaPhoenicia , was an ancient civilization in Canaan which covered most of the western, coastal part of the Fertile Crescent. Several major Phoenician cities were built on the coastline of the Mediterranean. It was an enterprising maritime trading culture that spread across the Mediterranean from 1550...

n merchant: a Phoenician and Philistine god of agriculture and the earth; the national god of the Philistines. - Tamar, Dagon's wife (chapters 8, 13): BiblicalBibleThe Bible refers to any one of the collections of the primary religious texts of Judaism and Christianity. There is no common version of the Bible, as the individual books , their contents and their order vary among denominations...

wife of ErEr (Biblical name)In the Biblical Book of Genesis, Er was the eldest son of Judah, and is described as marrying Tamar; According to the text, Yahweh killed Er because he was wicked, although it doesn't give any further details...

, then of his brother OnanOnanOnan is a minor biblical person in the Book of Genesis , who was the second son of Judah. Just like his older brother, Er, Onan died prematurely by YHWH's will for being wicked....

; she subsequently had children by their father Judah, eponymous ancestor of the Judeans and JewsJewsThe Jews , also known as the Jewish people, are a nation and ethnoreligious group originating in the Israelites or Hebrews of the Ancient Near East. The Jewish ethnicity, nationality, and religion are strongly interrelated, as Judaism is the traditional faith of the Jewish nation...

.

- Dutmose, a peasant (chapter 11): historic scribeScribeA scribe is a person who writes books or documents by hand as a profession and helps the city keep track of its records. The profession, previously found in all literate cultures in some form, lost most of its importance and status with the advent of printing...

Dhutmose, in the reign of Pharaoh Ramses XI. - MenesMenesMenes was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh of the early dynastic period, credited by classical tradition with having united Upper and Lower Egypt, and as the founder of the first dynasty ....

(three distinct individuals: the first pharaoh; Sarah's physicianPhysicianA physician is a health care provider who practices the profession of medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring human health through the study, diagnosis, and treatment of disease, injury and other physical and mental impairments...

; a savant and Pentuer's mentorMentorIn Greek mythology, Mentor was the son of Alcimus or Anchialus. In his old age Mentor was a friend of Odysseus who placed Mentor and Odysseus' foster-brother Eumaeus in charge of his son Telemachus, and of Odysseus' palace, when Odysseus left for the Trojan War.When Athena visited Telemachus she...

): Menes, the first Egyptian pharaoh. - Asarhadon, a PhoeniciaPhoeniciaPhoenicia , was an ancient civilization in Canaan which covered most of the western, coastal part of the Fertile Crescent. Several major Phoenician cities were built on the coastline of the Mediterranean. It was an enterprising maritime trading culture that spread across the Mediterranean from 1550...

n innkeeper: a variant of "EsarhaddonEsarhaddonEsarhaddon , was a king of Assyria who reigned 681 – 669 BC. He was the youngest son of Sennacherib and the Aramean queen Naqi'a , Sennacherib's second wife....

", an AssyriaAssyriaAssyria was a Semitic Akkadian kingdom, extant as a nation state from the mid–23rd century BC to 608 BC centred on the Upper Tigris river, in northern Mesopotamia , that came to rule regional empires a number of times through history. It was named for its original capital, the ancient city of Assur...

n king. - BerossusBerossusBerossus was a Hellenistic-era Babylonian writer, a priest of Bel Marduk and astronomer writing in Greek, who was active at the beginning of the 3rd century BC...

, a ChaldeaChaldeaChaldea or Chaldaea , from Greek , Chaldaia; Akkadian ; Hebrew כשדים, Kaśdim; Aramaic: ܟܐܠܕܘ, Kaldo) was a marshy land located in modern-day southern Iraq which came to briefly rule Babylon...

n priest: Berossus, a BabylonBabylonBabylon was an Akkadian city-state of ancient Mesopotamia, the remains of which are found in present-day Al Hillah, Babil Province, Iraq, about 85 kilometers south of Baghdad...

ian historian and astrologerAstrologyAstrology consists of a number of belief systems which hold that there is a relationship between astronomical phenomena and events in the human world...

who flourished about 300 BCE. - PhutPhutPhut or Put is the third son of Ham , in the biblical Table of Nations .Put is associated with Ancient Libya by many early writers...

(another name used by Berossus): Phut, a descendant of NoahNoahNoah was, according to the Hebrew Bible, the tenth and last of the antediluvian Patriarchs. The biblical story of Noah is contained in chapters 6–9 of the book of Genesis, where he saves his family and representatives of all animals from the flood by constructing an ark...

named in GenesisOld TestamentThe Old Testament, of which Christians hold different views, is a Christian term for the religious writings of ancient Israel held sacred and inspired by Christians which overlaps with the 24-book canon of the Masoretic Text of Judaism...

. - CushBiblical CushCush was the eldest son of Ham, brother of Mizraim , Canaan and the father of Nimrod, and Raamah, mentioned in the "Table of Nations" in the Genesis 10:6 and I Chronicles 1:8...

, a guest at Asarhadon's inn: Cush, a descendant of NoahNoahNoah was, according to the Hebrew Bible, the tenth and last of the antediluvian Patriarchs. The biblical story of Noah is contained in chapters 6–9 of the book of Genesis, where he saves his family and representatives of all animals from the flood by constructing an ark...

named in GenesisOld TestamentThe Old Testament, of which Christians hold different views, is a Christian term for the religious writings of ancient Israel held sacred and inspired by Christians which overlaps with the 24-book canon of the Masoretic Text of Judaism...

. - HiramHiramHiram , Standard Hebrew ', Tiberian Hebrew ', is a biblical given name.-People:* Hiram I, king of Tyrus, 969–936 BCE* Hiram II, king of Tyrus , 739–730 BCE...

, a Phoenician prince: Hiram IHiram IHiram I , according to the Hebrew Bible, was the Phoenician king of Tyre. He reigned from 980 to 947 BC, succeeding his father, Abibaal. Hiram was succeeded as king of Tyre by his son Baal-Eser I...

, king of Tyre, in PhoeniciaPhoeniciaPhoenicia , was an ancient civilization in Canaan which covered most of the western, coastal part of the Fertile Crescent. Several major Phoenician cities were built on the coastline of the Mediterranean. It was an enterprising maritime trading culture that spread across the Mediterranean from 1550...

. - Lykon, a young GreekGreeceGreece , officially the Hellenic Republic , and historically Hellas or the Republic of Greece in English, is a country in southeastern Europe....

, Ramses' look-alike and nemesis: LyconLyconLycon The absolute lowest life form. Lowest ranking level of unknown society; religion Lycon or Lyco may refer to:*Lycon, a son of King Hippocoon of Sparta in Greek mythology...

, in the IliadIliadThe Iliad is an epic poem in dactylic hexameters, traditionally attributed to Homer. Set during the Trojan War, the ten-year siege of the city of Troy by a coalition of Greek states, it tells of the battles and events during the weeks of a quarrel between King Agamemnon and the warrior Achilles...

. - SargonSargonSargon is an Assyrian name, originally Šarru-kin , which may refer to:- People :*Sargon of Akkad , also known as Sargon the Great or Sargon I, Mesopotamian king...

, an AssyriaAssyriaAssyria was a Semitic Akkadian kingdom, extant as a nation state from the mid–23rd century BC to 608 BC centred on the Upper Tigris river, in northern Mesopotamia , that came to rule regional empires a number of times through history. It was named for its original capital, the ancient city of Assur...

n envoyEnvoy (title)In diplomacy, an Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary is, under the terms of the Congress of Vienna of 1815, a diplomat of the second class, ranking between an Ambassador and a Minister Resident....

: name of two Assyrian kings, the first being the founder of one of history's first empires. - Seti, Ramses' infant son by Sarah: name of several ancient Egyptians, including two Pharaohs.

- OsokhorOsorkon the ElderAkheperre Setepenre Osorkon the Elder was the fifth king of the twenty-first dynasty of Egypt and was the first pharaoh of Libyan extraction in Egypt...

, a priest thought (chapter 40) to have sold Egyptian priestly secrets to the Phoenicians: a MeshweshMeshweshThe Meshwesh were an ancient Libyan tribe from beyond Cyrenaica where the Libu and Tehenu lived according to Egyptian references and who were probably of Central Berber ethnicity. Herodotus placed them in Tunisia and said of them to be sedentary farmers living in settled permanent houses as the...

king who ruled Egypt in the late 21st DynastyTwenty-first dynasty of EgyptThe Twenty-First, Twenty-Second, Twenty-Third, Twenty-Fourth, and Twenty-Fifth Dynasties of ancient Egypt are often combined under the group title, Third Intermediate Period.-Rulers:...

. - Musawasa, a LibyaLibyaLibya is an African country in the Maghreb region of North Africa bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Sudan to the southeast, Chad and Niger to the south, and Algeria and Tunisia to the west....

n prince: the MeshweshMeshweshThe Meshwesh were an ancient Libyan tribe from beyond Cyrenaica where the Libu and Tehenu lived according to Egyptian references and who were probably of Central Berber ethnicity. Herodotus placed them in Tunisia and said of them to be sedentary farmers living in settled permanent houses as the...

, a Libyan tribe. - Tehenna, Musavasa's son: "TjehenuMeshweshThe Meshwesh were an ancient Libyan tribe from beyond Cyrenaica where the Libu and Tehenu lived according to Egyptian references and who were probably of Central Berber ethnicity. Herodotus placed them in Tunisia and said of them to be sedentary farmers living in settled permanent houses as the...

", a generic Egyptian term for "Libyan." - Dion, a Greek architect: Dion, a historic name that appears in a number of contexts.

- Hebron, Ramses' last mistress: HebronHebronHebron , is located in the southern West Bank, south of Jerusalem. Nestled in the Judean Mountains, it lies 930 meters above sea level. It is the largest city in the West Bank and home to around 165,000 Palestinians, and over 500 Jewish settlers concentrated in and around the old quarter...

, the largest city in the present-day West BankWest BankThe West Bank ) of the Jordan River is the landlocked geographical eastern part of the Palestinian territories located in Western Asia. To the west, north, and south, the West Bank shares borders with the state of Israel. To the east, across the Jordan River, lies the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan...

.

Themes

Pharaoh belongs to a Polish literary tradition of political fiction whose roots reach back to the 16th century and Jan KochanowskiJan Kochanowski

Jan Kochanowski was a Polish Renaissance poet who established poetic patterns that would become integral to Polish literary language.He is commonly regarded as the greatest Polish poet before Adam Mickiewicz, and the greatest Slavic poet, prior to the 19th century.-Life:Kochanowski was born at...

's play, The Dismissal of the Greek Envoys (1578), and also includes Ignacy Krasicki

Ignacy Krasicki

Ignacy Krasicki , from 1766 Prince-Bishop of Warmia and from 1795 Archbishop of Gniezno , was Poland's leading Enlightenment poet , a critic of the clergy, Poland's La Fontaine, author of the first Polish novel, playwright, journalist, encyclopedist, and translator from French and...

's Fables and Parables

Fables and Parables

Fables and Parables , by Ignacy Krasicki , is a work in a long international tradition of fable-writing that reaches back to antiquity. They have been described as being, "[l]ike LaFontaine's [fables],.....

(1779) and Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz

Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz

Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz was a Polish poet, playwright and statesman. He was a leading advocate for the Constitution of May 3, 1791.-Life:...

's The Return of the Deputy (1790). Pharaohs story covers a two-year period, ending in 1085 BCE with the demise of the Egyptian Twentieth Dynasty and New Kingdom

New Kingdom

The New Kingdom of Egypt, also referred to as the Egyptian Empire is the period in ancient Egyptian history between the 16th century BC and the 11th century BC, covering the Eighteenth, Nineteenth, and Twentieth Dynasties of Egypt....

.

Polish Nobel laureate Czesław Miłosz has written of Pharaoh:

The perspective of which Miłosz writes, enables Prus, while formulating an ostensibly objective vision of historic Egypt, simultaneously to create a satire on man and society, much as Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift was an Irish satirist, essayist, political pamphleteer , poet and cleric who became Dean of St...

in Britain had done the previous century.

Seduction

In social science, seduction is the process of deliberately enticing a person to engage. The word seduction stems from Latin and means literally "to lead astray". As a result, the term may have a positive or negative connotation...

, subornation, defamation, intimidation or assassination

Assassination

To carry out an assassination is "to murder by a sudden and/or secret attack, often for political reasons." Alternatively, assassination may be defined as "the act of deliberately killing someone, especially a public figure, usually for hire or for political reasons."An assassination may be...

. Perhaps the chief lesson, belatedly absorbed by Ramses as pharaoh, is the importance, to power, of knowledge — of science

Science

Science is a systematic enterprise that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe...

.

As a political novel, Pharaoh became a favorite of Joseph Stalin

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

's; similarities have been pointed out between it and Sergei Eisenstein

Sergei Eisenstein

Sergei Mikhailovich Eisenstein , né Eizenshtein, was a pioneering Soviet Russian film director and film theorist, often considered to be the "Father of Montage"...

's film Ivan the Terrible

Ivan the Terrible (film)

Ivan the Terrible is a two-part historical epic film about Ivan IV of Russia made by Russian director Sergei Eisenstein. Part 1 was released in 1944 but Part 2 was not released until 1958 due to political censorship...

, produced under Stalin's tutelage. The novel's English translator has recounted wondering, well in advance of the event, whether President John F. Kennedy

John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald "Jack" Kennedy , often referred to by his initials JFK, was the 35th President of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963....

would meet with a fate like that of the book's protagonist.

Pharaoh is, in a sense, an extended study of the metaphor

Metaphor

A metaphor is a literary figure of speech that uses an image, story or tangible thing to represent a less tangible thing or some intangible quality or idea; e.g., "Her eyes were glistening jewels." Metaphor may also be used for any rhetorical figures of speech that achieve their effects via...

of society

Society

A society, or a human society, is a group of people related to each other through persistent relations, or a large social grouping sharing the same geographical or virtual territory, subject to the same political authority and dominant cultural expectations...

-as-organism

Organism

In biology, an organism is any contiguous living system . In at least some form, all organisms are capable of response to stimuli, reproduction, growth and development, and maintenance of homoeostasis as a stable whole.An organism may either be unicellular or, as in the case of humans, comprise...

that Prus had adopted from English philosopher and sociologist Herbert Spencer, and that Prus makes explicit in the introduction to the novel: "the Egyptian nation in its times of greatness formed, as it were, a single person, in which the priesthood was the mind, the pharaoh was the will, the people the body, and obedience the cement." All of society's organ systems must work together harmoniously, if society is to survive and prosper.

Pharaoh is a study of factors that affect the rise and fall of civilization

Civilization

Civilization is a sometimes controversial term that has been used in several related ways. Primarily, the term has been used to refer to the material and instrumental side of human cultures that are complex in terms of technology, science, and division of labor. Such civilizations are generally...

s.

Inspirations

Pharaoh is unique in Prus' oeuvre as a historical novel. A Positivist by philosophical persuasion, Prus had long argued that historical novels must inevitably distort historic reality. He had, however, eventually come over to the view of the French Positivist critic Hippolyte TaineHippolyte Taine

Hippolyte Adolphe Taine was a French critic and historian. He was the chief theoretical influence of French naturalism, a major proponent of sociological positivism, and one of the first practitioners of historicist criticism. Literary historicism as a critical movement has been said to originate...

that the arts, including literature, may act as a second means alongside the sciences to study reality, including broad historic reality.

Prus, in the interest of making certain points, intentionally introduced some anachronisms and anatopisms into the novel.

Egypt

Egypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

's New Kingdom

New Kingdom

The New Kingdom of Egypt, also referred to as the Egyptian Empire is the period in ancient Egyptian history between the 16th century BC and the 11th century BC, covering the Eighteenth, Nineteenth, and Twentieth Dynasties of Egypt....

three thousand years earlier, reflects the demise

Partitions of Poland

The Partitions of Poland or Partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth took place in the second half of the 18th century and ended the existence of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, resulting in the elimination of sovereign Poland for 123 years...

of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was a dualistic state of Poland and Lithuania ruled by a common monarch. It was the largest and one of the most populous countries of 16th- and 17th‑century Europe with some and a multi-ethnic population of 11 million at its peak in the early 17th century...

in 1795, exactly a century before Pharaohs completion.

A preliminary sketch for Prus' only historical novel was his first historical short story

Short story

A short story is a work of fiction that is usually written in prose, often in narrative format. This format tends to be more pointed than longer works of fiction, such as novellas and novels. Short story definitions based on length differ somewhat, even among professional writers, in part because...

, "A Legend of Old Egypt

A Legend of Old Egypt

"A Legend of Old Egypt" is a short story by Bolesław Prus, originally published January 1, 1888, in New Year's supplements to the Warsaw Kurier Codzienny and Tygodnik Ilustrowany...

." This remarkable story shows clear parallels with the subsequent novel in setting

Setting (fiction)

In fiction, setting includes the time, location, and everything in which a story takes place, and initiates the main backdrop and mood for a story. Setting has been referred to as story world or milieu to include a context beyond the immediate surroundings of the story. Elements of setting may...

, theme

Theme (literature)

A theme is a broad, message, or moral of a story. The message may be about life, society, or human nature. Themes often explore timeless and universal ideas and are almost always implied rather than stated explicitly. Along with plot, character,...

and denouement. "A Legend of Old Egypt", in its turn, had taken inspiration from contemporaneous events: the fatal 1887-88 illnesses of Germany's warlike Kaiser Wilhelm I and of his reform-minded son and successor, Friedrich III. The latter emperor would, then unbeknown to Prus, survive his ninety-year-old predecessor, but only by ninety-nine days.

In 1893 Prus' old friend Julian Ochorowicz

Julian Ochorowicz

Julian Leopold Ochorowicz was a Polish philosopher, psychologist, inventor , poet, publicist and leading exponent of Polish Positivism.-Life:Julian Ochorowicz was the son of Julian and Jadwiga, née...

, having returned to Warsaw

Warsaw

Warsaw is the capital and largest city of Poland. It is located on the Vistula River, roughly from the Baltic Sea and from the Carpathian Mountains. Its population in 2010 was estimated at 1,716,855 residents with a greater metropolitan area of 2,631,902 residents, making Warsaw the 10th most...

from Paris, delivered several public lectures on ancient Egyptian knowledge. Ochorowicz (whom Prus had portrayed in The Doll

The Doll (novel)

The Doll is the second of four major novels by the Polish writer Bolesław Prus. It was composed for periodical serialization in 1887-89 and appeared in book form in 1890....

as the scientist "Julian Ochocki," obsessed with inventing a powered flying machine, a decade and a half before the Wright brothers

Wright brothers

The Wright brothers, Orville and Wilbur , were two Americans credited with inventing and building the world's first successful airplane and making the first controlled, powered and sustained heavier-than-air human flight, on December 17, 1903...

’ 1903 flight) may have inspired Prus to write his historical novel about ancient Egypt. Ochorowicz made available to Prus books on the subject that he had brought from Paris.

In preparation for composing Pharaoh, Prus made a painstaking study of Egyptological

Egyptology

Egyptology is the study of ancient Egyptian history, language, literature, religion, and art from the 5th millennium BC until the end of its native religious practices in the AD 4th century. A practitioner of the discipline is an “Egyptologist”...

sources, including works by John William Draper

John William Draper

John William Draper was an American scientist, philosopher, physician, chemist, historian, and photographer. He is credited with producing the first clear photograph of a female face and the first detailed photograph of the Moon...

, Ignacy Żagiell

Ignacy Zagiell

Ignacy Żagiell was a physician, traveler and Polish-language writer.-Life:...

, Georg Ebers

Georg Ebers

Georg Moritz Ebers , German Egyptologist and novelist, discovered the Egyptian medical papyrus, of ca. 1550 BCE, named for him at Luxor in the winter of 1873–74...

and Gaston Maspero

Gaston Maspero

Gaston Camille Charles Maspero was a French Egyptologist.-Life:Gaston Maspero was born in Paris to parents of Lombard origin. While at school he showed a special taste for history, and by the age of fourteen he was already interested in hieroglyphic writing...

. Prus actually incorporated ancient texts into his novel like tessera

Tessera

A tessera is an individual tile in a mosaic, usually formed in the shape of a cube. It is also known as an abaciscus, abaculus, or, in Persian کاشي معرق. In antiquity, mosaics were formed from naturally colored pebbles, but by 200 BC purpose-made tesserae were being used...

e into a mosaic

Mosaic

Mosaic is the art of creating images with an assemblage of small pieces of colored glass, stone, or other materials. It may be a technique of decorative art, an aspect of interior decoration, or of cultural and spiritual significance as in a cathedral...

; drawn from one such text was a major character, Ennana.

Pharaoh also alludes to biblical Old Testament

Old Testament

The Old Testament, of which Christians hold different views, is a Christian term for the religious writings of ancient Israel held sacred and inspired by Christians which overlaps with the 24-book canon of the Masoretic Text of Judaism...

accounts of Moses

Moses

Moses was, according to the Hebrew Bible and Qur'an, a religious leader, lawgiver and prophet, to whom the authorship of the Torah is traditionally attributed...

(chapter 7), the plagues of Egypt

Plagues of Egypt

The Plagues of Egypt , also called the Ten Plagues or the Biblical Plagues, were ten calamities that, according to the biblical Book of Exodus, Israel's God, Yahweh, inflicted upon Egypt to persuade Pharaoh to release the ill-treated Israelites from slavery. Pharaoh capitulated after the tenth...

(chapter 64), and Judith and Holofernes

Holofernes

In the deuterocanonical Book of Judith Holofernes was an invading general of Nebuchadnezzar. Nebuchadnezzar dispatched Holofernes to take vengeance on the nations of the west that had withheld their assistance to his reign...

(chapter 7); and to Troy

Troy

Troy was a city, both factual and legendary, located in northwest Anatolia in what is now Turkey, southeast of the Dardanelles and beside Mount Ida...

, which had recently been excavated by Heinrich Schliemann

Heinrich Schliemann

Heinrich Schliemann was a German businessman and amateur archaeologist, and an advocate of the historical reality of places mentioned in the works of Homer. Schliemann was an archaeological excavator of Troy, along with the Mycenaean sites Mycenae and Tiryns...

.

For certain of the novel's prominent features, Prus, the conscientious journalist and scholar, seems to have insisted on having two sources, one of them based on personal or at least contemporary experience. One such dually-determined feature relates to Egyptian beliefs about an afterlife

Afterlife

The afterlife is the belief that a part of, or essence of, or soul of an individual, which carries with it and confers personal identity, survives the death of the body of this world and this lifetime, by natural or supernatural means, in contrast to the belief in eternal...

. In 1893, the year before beginning his novel, Prus the skeptic had started taking an intense interest in Spiritualism, attending Warsaw séance

Séance

A séance is an attempt to communicate with spirits. The word "séance" comes from the French word for "seat," "session" or "sitting," from the Old French "seoir," "to sit." In French, the word's meaning is quite general: one may, for example, speak of "une séance de cinéma"...

s which featured the Italian

Italy

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

medium, Eusapia Palladino—the same medium whose Paris

Paris

Paris is the capital and largest city in France, situated on the river Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region...

séances, a dozen years later, would be attended by Pierre and Marie Curie. Palladino had been brought to Warsaw

Warsaw

Warsaw is the capital and largest city of Poland. It is located on the Vistula River, roughly from the Baltic Sea and from the Carpathian Mountains. Its population in 2010 was estimated at 1,716,855 residents with a greater metropolitan area of 2,631,902 residents, making Warsaw the 10th most...

from a St. Petersburg mediumistic tour by Prus' friend Ochorowicz

Julian Ochorowicz

Julian Leopold Ochorowicz was a Polish philosopher, psychologist, inventor , poet, publicist and leading exponent of Polish Positivism.-Life:Julian Ochorowicz was the son of Julian and Jadwiga, née...

.

Fox sisters

The Fox sisters were three sisters from New York who played an important role in the creation of Spiritualism. The three sisters were Leah Fox , Margaret Fox and Kate Fox . The two younger sisters used "rappings" to convince their much older sister and others that they were communicating with...

, Katie and Margaret, aged 11 and 15, and had survived even their 1888 confession that forty years earlier they had caused the "spirit

Spirit

The English word spirit has many differing meanings and connotations, most of them relating to a non-corporeal substance contrasted with the material body.The spirit of a living thing usually refers to or explains its consciousness.The notions of a person's "spirit" and "soul" often also overlap,...

s'" telegraph-like tapping sounds by snapping their toe joints. Spiritualist "mediums" in America and Europe claimed to communicate through tapping sounds with spirits of the dead, eliciting their secrets and conjuring up voices, music, noises and other antics, and occasionally working "miracles" such as levitation.

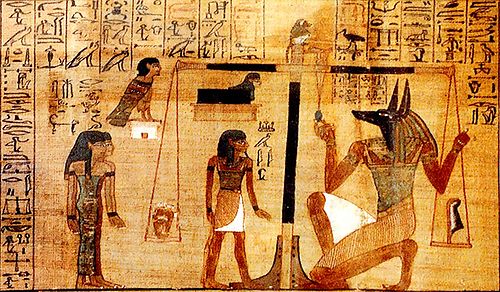

Spiritualism inspired several of Pharaohs most striking scenes, especially (chapter 20) the secret meeting at the Temple of Seth in Memphis between three Egyptian priests—Herhor, Mefres, Pentuer—and the Chaldea

Chaldea

Chaldea or Chaldaea , from Greek , Chaldaia; Akkadian ; Hebrew כשדים, Kaśdim; Aramaic: ܟܐܠܕܘ, Kaldo) was a marshy land located in modern-day southern Iraq which came to briefly rule Babylon...

n magus-priest Berossus; and (chapter 26) the protagonist Ramses' night-time exploration at the Temple of Hathor in Pi-Bast, when unseen hands touch his head and back.

Another dually-determined feature of the novel is the "Suez Canal" that the Phoenician Prince Hiram proposes digging. The modern Suez Canal

Suez Canal

The Suez Canal , also known by the nickname "The Highway to India", is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea. Opened in November 1869 after 10 years of construction work, it allows water transportation between Europe and Asia without navigation...

had been completed by Ferdinand de Lesseps

Ferdinand de Lesseps

Ferdinand Marie, Vicomte de Lesseps, GCSI was the French developer of the Suez Canal, which joined the Mediterranean and Red Seas in 1869, and substantially reduced sailing distances and times between the West and the East.He attempted to repeat this success with an effort to build a sea-level...

in 1869, a quarter-century before Prus commenced writing Pharaoh. But, as Prus was aware when writing chapter one, the Suez Canal had had a predecessor in a canal that had connected the Nile River with the Red Sea

Red Sea

The Red Sea is a seawater inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. The connection to the ocean is in the south through the Bab el Mandeb strait and the Gulf of Aden. In the north, there is the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and the Gulf of Suez...

— during Egypt's Middle Kingdom

Middle Kingdom of Egypt

The Middle Kingdom of Egypt is the period in the history of ancient Egypt stretching from the establishment of the Eleventh Dynasty to the end of the Fourteenth Dynasty, between 2055 BC and 1650 BC, although some writers include the Thirteenth and Fourteenth dynasties in the Second Intermediate...

, centuries before the period of the novel.

Herodotus

Herodotus was an ancient Greek historian who was born in Halicarnassus, Caria and lived in the 5th century BC . He has been called the "Father of History", and was the first historian known to collect his materials systematically, test their accuracy to a certain extent and arrange them in a...

had visited Egypt's entirely stone-built administrative center, pronounced it more impressive than the pyramids, declared it "beyond my power to describe"—then proceeded to give a striking description that Prus incorporated into his novel. The Labyrinth had, however, been made palpably real for Prus by an 1878 visit that he had paid to the famous ancient labyrinthine salt mine at Wieliczka, near Kraków

Kraków

Kraków also Krakow, or Cracow , is the second largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in the Lesser Poland region, the city dates back to the 7th century. Kraków has traditionally been one of the leading centres of Polish academic, cultural, and artistic life...

in southern Poland. According to the foremost Prus scholar, Zygmunt Szweykowski

Zygmunt Szweykowski

Zygmunt Szweykowski was a historian of Polish literature who specialized in 19th-century Polish prose.-Life:...

, "The power of the Labyrinth scenes stems, among other things, from the fact that they echo Prus' own experiences when visiting Wieliczka."

Writing over four decades before the construction of the United States' Fort Knox

Fort Knox

Fort Knox is a United States Army post in Kentucky south of Louisville and north of Elizabethtown. The base covers parts of Bullitt, Hardin, and Meade counties. It currently holds the Army Human Resources Center of Excellence to include the Army Human Resources Command, United States Army Cadet...

Depository

United States Bullion Depository

The United States Bullion Depository, often known as Fort Knox, is a fortified vault building located adjacent to Fort Knox, Kentucky, used to store a large portion of United States official gold reserves and occasionally other precious items belonging or entrusted to the federal government.The...

, Prus pictures Egypt's Labyrinth as a perhaps flood-able Egyptian Fort Knox, a repository of gold

Gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au and an atomic number of 79. Gold is a dense, soft, shiny, malleable and ductile metal. Pure gold has a bright yellow color and luster traditionally considered attractive, which it maintains without oxidizing in air or water. Chemically, gold is a...

bullion and of artistic and historic treasures. It was, he writes (chapter 56), "the greatest treasury in Egypt. [H]ere... was preserved the treasure of the Egyptian kingdom, accumulated over centuries, of which it is difficult today to have any conception."

Solar eclipse

As seen from the Earth, a solar eclipse occurs when the Moon passes between the Sun and the Earth, and the Moon fully or partially blocks the Sun as viewed from a location on Earth. This can happen only during a new moon, when the Sun and the Moon are in conjunction as seen from Earth. At least...

that Prus had witnessed at Mława, a hundred kilometers north-northwest of Warsaw

Warsaw

Warsaw is the capital and largest city of Poland. It is located on the Vistula River, roughly from the Baltic Sea and from the Carpathian Mountains. Its population in 2010 was estimated at 1,716,855 residents with a greater metropolitan area of 2,631,902 residents, making Warsaw the 10th most...

, on 19 August 1887, the day before his fortieth birthday. Prus probably also was aware of Christopher Columbus' manipulative use of a lunar eclipse

Lunar eclipse

A lunar eclipse occurs when the Moon passes behind the Earth so that the Earth blocks the Sun's rays from striking the Moon. This can occur only when the Sun, Earth, and Moon are aligned exactly, or very closely so, with the Earth in the middle. Hence, a lunar eclipse can only occur the night of a...

on 29 February 1504, while marooned for a year on Jamaica

Jamaica

Jamaica is an island nation of the Greater Antilles, in length, up to in width and 10,990 square kilometres in area. It is situated in the Caribbean Sea, about south of Cuba, and west of Hispaniola, the island harbouring the nation-states Haiti and the Dominican Republic...

, to extort provisions from the Arawak natives. The latter incident

March 1504 lunar eclipse

A total lunar eclipse occurred on March 1, 1504 .Christopher Columbus, in a desperate effort to induce the natives of Jamaica to continue provisioning him and his hungry men, successfully intimidated the natives by correctly predicting a lunar eclipse for February 29, 1504, using the Ephemeris of...

strikingly resembles the exploitation of a solar eclipse

Solar eclipse

As seen from the Earth, a solar eclipse occurs when the Moon passes between the Sun and the Earth, and the Moon fully or partially blocks the Sun as viewed from a location on Earth. This can happen only during a new moon, when the Sun and the Moon are in conjunction as seen from Earth. At least...

by Ramses' chief adversary, Herhor, high priest of Amon, in a culminating scene of the novel. (Similar use of Columbus' lunar eclipse had in 1889 been made by Mark Twain

Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens , better known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American author and humorist...

in A Connecticut Yankee at King Arthur's Court.)

Yet another plot element involves the Greek, Lykon, in chapters 63 and 66 and passim—hypnosis

Hypnosis

Hypnosis is "a trance state characterized by extreme suggestibility, relaxation and heightened imagination."It is a mental state or imaginative role-enactment . It is usually induced by a procedure known as a hypnotic induction, which is commonly composed of a long series of preliminary...

and post-hypnotic suggestion

Post-hypnotic suggestion

A Post-hypnotic suggestion is a behavior or thinking pattern that presumably will manifest after a subject has come out of the so-called "hypnotic state" .According to a psychologist at the University of New South Wales:...

.

It is unclear whether Prus, in using the plot device

Plot device

A plot device is an object or character in a story whose sole purpose is to advance the plot of the story, or alternatively to overcome some difficulty in the plot....

of the look-alike (Berossus' double; Lykon as double to Ramses), was inspired by earlier novelists who had employed it, including Alexandre Dumas (The Man in the Iron Mask, 1850), Charles Dickens

Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens was an English novelist, generally considered the greatest of the Victorian period. Dickens enjoyed a wider popularity and fame than had any previous author during his lifetime, and he remains popular, having been responsible for some of English literature's most iconic...

(A Tale of Two Cities

A Tale of Two Cities

A Tale of Two Cities is a novel by Charles Dickens, set in London and Paris before and during the French Revolution. With well over 200 million copies sold, it ranks among the most famous works in the history of fictional literature....

, 1859) and Mark Twain

Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens , better known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American author and humorist...

(The Prince and the Pauper

The Prince and the Pauper

The Prince and the Pauper is an English-language novel by American author Mark Twain. It was first published in 1881 in Canada before its 1882 publication in the United States. The book represents Twain's first attempt at historical fiction...

, 1882).

Prus, a disciple of Positivist

Positivism

Positivism is a a view of scientific methods and a philosophical approach, theory, or system based on the view that, in the social as well as natural sciences, sensory experiences and their logical and mathematical treatment are together the exclusive source of all worthwhile information....

philosophy

Philosophy

Philosophy is the study of general and fundamental problems, such as those connected with existence, knowledge, values, reason, mind, and language. Philosophy is distinguished from other ways of addressing such problems by its critical, generally systematic approach and its reliance on rational...

, took a strong interest in the history of science

History of science

The history of science is the study of the historical development of human understandings of the natural world and the domains of the social sciences....

. He was aware of Eratosthenes

Eratosthenes

Eratosthenes of Cyrene was a Greek mathematician, poet, athlete, geographer, astronomer, and music theorist.He was the first person to use the word "geography" and invented the discipline of geography as we understand it...

' remarkably accurate calculation of the earth's circumference, and the invention of a steam engine

Steam engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid.Steam engines are external combustion engines, where the working fluid is separate from the combustion products. Non-combustion heat sources such as solar power, nuclear power or geothermal energy may be...

by Heron of Alexandria, centuries after the period of his novel, in Alexandria

Alexandria

Alexandria is the second-largest city of Egypt, with a population of 4.1 million, extending about along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea in the north central part of the country; it is also the largest city lying directly on the Mediterranean coast. It is Egypt's largest seaport, serving...

n Egypt. In chapter 60, he fictitiously credits these achievements to the priest Menes, one of three individuals of the identical name who are mentioned or depicted in Pharaoh: Prus was not always fastidious about characters' names.

Accuracy

Examples of anachronism and anatopism, mentioned above, bear out that a punctilious historic accuracy was never an object with Prus in writing Pharaoh. "That's not the point", Prus' compatriot Joseph ConradJoseph Conrad

Joseph Conrad was a Polish-born English novelist.Conrad is regarded as one of the great novelists in English, although he did not speak the language fluently until he was in his twenties...

told a relative. Prus had long emphasized in his "Weekly Chronicles" articles that historical novels cannot but distort historic reality. He used ancient Egypt as a canvas on which to depict his deeply-considered perspectives on man, civilization and politics.

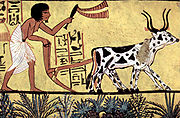

Nevertheless, Pharaoh is remarkably accurate, even from the standpoint of present-day Egyptology. The novel does a notable job of recreating a primal ancient civilization, complete with the geography, climate, plants, animals, ethnicities, countryside, agriculture, cities, trades, commerce, social stratification

Social stratification

In sociology the social stratification is a concept of class, involving the "classification of persons into groups based on shared socio-economic conditions ... a relational set of inequalities with economic, social, political and ideological dimensions."...

, politics

Politics

Politics is a process by which groups of people make collective decisions. The term is generally applied to the art or science of running governmental or state affairs, including behavior within civil governments, but also applies to institutions, fields, and special interest groups such as the...

, religion and warfare. Prus succeeds remarkably in transporting readers back to the Egypt of thirty-one centuries ago.

The embalming and funeral

Funeral

A funeral is a ceremony for celebrating, sanctifying, or remembering the life of a person who has died. Funerary customs comprise the complex of beliefs and practices used by a culture to remember the dead, from interment itself, to various monuments, prayers, and rituals undertaken in their honor...

scenes; the court

Noble court

The court of a monarch, or at some periods an important nobleman, is a term for the extended household and all those who regularly attended on the ruler or central figure...

protocol

Etiquette

Etiquette is a code of behavior that delineates expectations for social behavior according to contemporary conventional norms within a society, social class, or group...

; the waking and feeding of the gods; the religious beliefs, ceremonies and processions; the concept behind the design of Pharaoh Zoser's Step Pyramid at Saqqara

Saqqara

Saqqara is a vast, ancient burial ground in Egypt, serving as the necropolis for the Ancient Egyptian capital, Memphis. Saqqara features numerous pyramids, including the world famous Step pyramid of Djoser, sometimes referred to as the Step Tomb due to its rectangular base, as well as a number of...

; the descriptions of travels and of locales visited on the Nile and in the desert; Egypt's exploitation of Nubia

Nubia

Nubia is a region along the Nile river, which is located in northern Sudan and southern Egypt.There were a number of small Nubian kingdoms throughout the Middle Ages, the last of which collapsed in 1504, when Nubia became divided between Egypt and the Sennar sultanate resulting in the Arabization...

as a source of gold

Gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au and an atomic number of 79. Gold is a dense, soft, shiny, malleable and ductile metal. Pure gold has a bright yellow color and luster traditionally considered attractive, which it maintains without oxidizing in air or water. Chemically, gold is a...

— all draw upon scholarly documentation. The personalities and behaviors of the characters are keenly observed and deftly drawn, often with the aid of apt Egyptian texts.

Popularity

Pharaoh, as a "political novel", has remained perennially topical ever since it was written. The book's enduring popularity, however, has as much to do with a critical yet sympathetic view of human natureHuman nature

Human nature refers to the distinguishing characteristics, including ways of thinking, feeling and acting, that humans tend to have naturally....

and the human condition

Human condition